Guidance on the use of the Guaranteed Minimum Pensions (GMP) conversion legislation

Published 18 April 2019

1. Introduction and Executive Summary

This guidance has been produced by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) with the assistance of an industry working group in order to assist occupational pension schemes that have yet to address inequalities in scheme benefits due to the existence of unequal Guaranteed Minimum Pensions (GMPs).

It describes how schemes could use the GMP conversion legislation to achieve equality going forwards. To the extent to which this guidance relates to the use of the conversion legislation, it is provided in accordance with section 24A (2) of the Pension Schemes Act 1993.

1.1 The GMP and the inequalities it creates

The GMP is the minimum pension that an occupational pension scheme, contracted out of the Additional State Pension between 6 April 1978 and 5 April 1997 on a salary related basis, has to provide to its members.

Although the GMP rules were abolished for contracted out service after 5 April 1997, past accruals remain subject to them. So a scheme that was contracted out under the GMP rules must still provide a pension at least as good as the GMP in respect of periods of contracted out pensionable service between 6 April 1978 and 5 April 1997.

It has long been recognised by government that GMPs create an inequality in the total overall pension a man and woman in similar circumstances receive. The reasons for this are explained in the next section.

As a result of the Barber judgment of 17 May 1990 and subsequent decisions of the European Court including the Allonby judgment of 13 January 2004, government has recognised that schemes must equalise pensions for the effect of inequalities caused by GMPs even where no opposite sex comparator exists.

The government has not asserted that there is a single method by which schemes can equalise benefits for the effect of GMPs. It takes the view that it is for the trustees of each scheme to decide the methodology that is most appropriate for their scheme, taking into account the circumstances of the scheme and, where necessary, having obtained the consent of the sponsoring employer.

However, the government has responded to industry requests for assistance by putting forward possible methods for equalising benefits.

In January 2012 government consulted on one possible method which required schemes to compare on a year by year basis the position of a male against a female and pay the better of the two.

However, this methodology was not well received by the pensions industry, on the basis that it would be administratively expensive, and would result in both men and women receiving pensions that after adjustment would be higher than either a man or a woman would otherwise have received.

Sympathetic to the industry’s concerns, the Minister for Pensions at the time decided not to make a final publication of that methodology.

Instead DWP started to investigate with a pensions industry working group whether equalising pensions for the effect of unequal GMPs might be achieved through a less onerous process that would be acceptable to both the government and to the pensions industry, accepting that it is the trustees’ responsibility to comply with all relevant legislation.

1.2 The GMP Conversion Working Group – Introduction of a new methodology for achieving equalisation

In 2013 a working group was set up comprising leading practitioners from across the pensions industry.

The remit of the group was to see whether and how the GMP conversion process might be used to equalise scheme benefits for the effects of unequal GMPs, and to seek a solution that would allow schemes to provide equal benefits but without imposing overly onerous burdens on those schemes.

Although conversion was permitted by legislation, it had been rarely used in practice.

Also the working group indicated that certain aspects of the wording of the legislation could benefit from clarification.

In November 2016, as a result of the work done by the group, DWP consulted on a new proposed methodology for achieving equal benefits taking into account GMPs.

The method, which is described in greater detail in sections 4 and 5, places, for the purpose of equalisation, an actuarial value on benefits accruing between 17 May 1990 (the date of the Barber judgment) and 5 April 1997 (when GMP accrual ended), takes the higher of the value of a member’s benefits and the value it would have been had the member been of the opposite sex during the period and converts this higher value into benefits that are no longer subject to the (unequal) requirements of the GMP legislation.

The methodology has been generally well received by the pensions industry. Unlike the previous proposal the conversion method does not require costly annual comparisons between men and women to determine who has the higher pension and then pay the higher of the 2 each year.

Under the methodology a scheme is amended so that it no longer contains benefits subject to the GMP rules in respect of some or all members with GMP entitlements.

This conversion means that the GMP rules, which create inequality between the sexes, are removed for the relevant members going forward.

To assist understanding of how the process is expected to work in practice the government has now produced this guidance which provides:

- a more detailed explanation of the methodology which DWP is putting forward as a possible way to equalise benefits for the effect of inequalities caused by the GMP rules

- guidance relating to the practicalities of the conversion process

- a statement relating to the pensions tax issues that are being explored by HMRC (relevant whatever means of equalising is employed)

- a question and answer section

The government is not placing any obligation on schemes to use this method nor does the method or this guidance comprise advice to schemes on how to equalise, it should not be treated as a definitive statement of how equalisation should be effected.

It simply describes one way of equalising for the effect of the GMP legislation which the government believes meets the equalisation obligation.

The government does not assert this is the only way that equalisation can be achieved and the High Court confirmed in the Lloyds Bank case that a range of methodologies may be available.

Trustees may therefore wish to consider other methodologies or variations on them and take their own advice before deciding which approach best suits their scheme.

2. Why GMPs create inequality in overall scheme benefits

Legislation requires GMPs to be determined on an unequal basis, under the State Pension Schemes Act 1993, a woman’s GMP normally accrued at a greater rate than that of a man in recognition that a woman’s working life for state pension purposes was at the time 5 years shorter than that of a man.

As a result, where a woman and a man have an identical work history, the woman’s GMP will typically be greater than that of the man.

As a woman is also entitled to receive her GMP at an earlier “GMP pension age” (age 60) than a man is entitled to receive his (age 65), further differences will arise.

This is through the operation of the revaluation provisions of the Pension Schemes Act 1993 applicable up to GMP pension age and of the different indexation provisions of the Pension Schemes Act 1993 after GMP pension age.

Whilst the rates of revaluation or indexation do not differ on the basis of sex, a woman will be entitled to indexation on her GMP in periods during which a man is entitled to revaluation on his GMP, due to the differing GMP pension ages.

There is also a late retirement uplift when payment begins after GMP pension age. So whilst a woman’s GMP will typically start out as higher than that for a comparable man, the man’s GMP in any given year after GMP pension age may overtake that of the woman’s due to the different ages by which revaluation, indexation and the late retirement uplift are referenced.

The requirement that GMPs are calculated and paid on an unequal basis often results in an inequality in the overall scheme pension in payment.

This is due to the requirements of preservation, revaluation and anti-franking legislation in the Pension Schemes Act 1993 under which benefits above GMP (“excess benefits”) are determined with reference to this unequal GMP; and the fact that revaluation and indexation provided on the excess benefit can and usually do differ to that on the GMP element (depending on the legislation, the rules and practices of the scheme).

As a result, it can be far from clear which sex receives the greater total scheme benefit.

It is also possible for the position to change over the course of a lifetime so that an individual who is advantaged on the basis of sex when the GMP is first paid becomes disadvantaged later.

In other words, which sex is advantaged may fluctuate over the course of a lifetime.

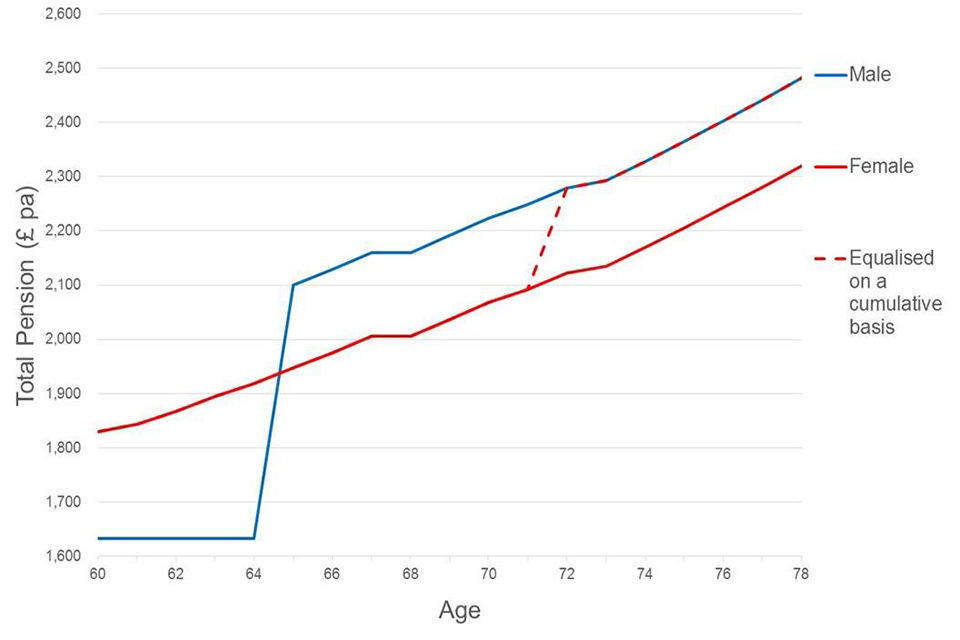

An example of inequalities caused by GMPs

A man and woman with identical service history, all of which falls between 1990 and 1997, both leave pensionable service at age 55.

At this point their deferred pensions are the same (£1,500 per year). However, the man’s GMP on leaving (£522 per year) is less than the woman’s GMP (£635 per year) because of the different GMP accrual rates for men and women.

Under the scheme rules, the rate at which GMP revalues is higher (7% per year) than the rate at which the excess revalues.

This means that by the time they reach the scheme’s normal pension age, which is 60, the man’s pension (£1,633 per year) will be less than that of the woman (£1,815 per year).

The scheme also has a practice, for men, of putting into payment a pension at 60 that does not take account of the revaluation of the GMP from leaving.

In this particular scheme no pension increases are made on pre April 1997 benefits other than the increases required by legislation on the GMP.

As the man, has not yet reached GMP pension age for men (65), he will have no pension increases on the pension which comes into payment at age 60.

However, as the GMP pension age for the woman is 60, she will receive increases on the GMP element of her pension from age 60. This element is £832 per year at 60.

The gap between the pension paid to the man and the pension paid to the woman will get wider each year until they are 65 because of the increases she receives on the GMP element of her pension.

However, when the man reaches the GMP pension age for men (65), in this particular case the scheme gives him a “step–up” equal to the revaluation on the GMP element of his pension between 55 and 65.

As this revaluation (at £438 per year) when added to the revaluation on his excess from 55 to 60 (£133 pa) is higher than the sum of the revalution the woman has received on excess and GMP from 55 to 60 (£315 per year) and the pension increases the woman has received on her GMP between 60 and 65 (£104 per year), his pension overtakes the pension paid to the woman. He also starts to receive annual pension increases on the GMP element of his pension.

It may be some years before, on a cumulative basis, the discrimination suffered by the man from the lower pension he received between the ages of 60 and 65 is recovered by the higher payments he receives from age 65.

From this point (age 72 in this example), the cumulative pension paid to the man will become greater than that paid to the woman. When that happens, the woman will start to suffer discrimination on this measure.

This example illustrates a situation where (initially at least) men aged over 60, can be disadvantaged. Other examples can be constructed where women are disadvantaged.

Guaranteed Minimum Pension

These situations often arise where the scheme provides pension increases on the excess over the GMP which are more generous than those provided on the GMP and also has a practice of providing, often on a discretionary basis, revaluation on the GMP for men when a pension is put into payment before 65.

3. Why inequalities arising from GMPs need to be addressed

3.1 The Barber judgment

On 17 May 1990 the Court of Justice of the European Union ruled that occupational pensions were a form of deferred pay (the “Barber” judgment).

Therefore, what is now Article 157 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union applied, and it was unlawful to discriminate between men and women in relation to occupational pensions.

It was subsequently decided by that court that the Barber judgment applied to any pension that accrued from the date of the judgment going forward.

The government reflected this judgment in domestic legislation, initially in section 62 of the Pensions Act 1995.

That section imported an equal treatment rule into occupational pension schemes which did not already contain one.

The obligations on schemes formerly contained in the Pensions Act 1995 have since been replaced by equivalent provisions in the Equality Act 2010.

In particular, section 67 of the Equality Act 2010 requires occupational pension schemes which do not include a sex equality rule (requiring rules which treat one sex less favourably to be read as though they did not treat that sex less favourably) to be treated as including one.

In line with equal pay requirements, the legislation provides that these equal treatment rules apply only where there is an opposite sex comparator: an individual of the opposite sex who is in like work, or work rated as equivalent, who is treated more favourably.

3.2 The window of inequality caused by unequal GMPs

GMPs accrued for men and women between 6 April 1978 (when contracting out from SERPS was introduced) and 5 April 1997 when a new test for contracted–out employment was introduced – the Reference Scheme Test (which operated on an equalised normal pension age of 65).

A combination of the Barber judgment of 17 May 1990, which requires pensions to be equalised from that day forwards, and the ending of GMPs on 5 April 1997 effectively means that there is a window between 17 May 1990 and 5 April 1997 in relation to which a scheme will need to address any inequalities in scheme benefits caused by these unequal GMPs.

The law does not require schemes to address inequalities in scheme benefits caused by unequal GMPs that accrued between 6 April 1978 and 16 May 1990.

3.3 The Allonby judgment

Since the Barber judgment the court of justice of the European Union has reconsidered the issue of equal treatment between the sexes in a line of case law including the case of Allonby handed down on 13 January 2004.

The government’s understanding of the court’s conclusions in those cases is that, as inequality resulting from the GMP rules arises from state legislation, the requirement to remove any unfavourable treatment resulting from those rules is not subject to the requirement that an opposite sex comparator exists.

In January 2012, along with a proposed methodology for equalising pensions for the effect of unequal GMPs, DWP consulted on changes to the Equality Act 2010 to remove the requirement in that Act for a comparator.

The government decided not to make these draft regulations whilst further consideration was given to the proposed methodology which was rejected by the pensions industry.

However, it remains the government’s intention to introduce the necessary changes to the Equality Act 2010 to reflect the Allonby judgment and DWP will do this as soon as a suitable opportunity presents itself.

It remains the government’s view that pension schemes must remove any unfavourable treatment resulting from GMPs that accrued between 17 May 1990 and 5 April 1997 whether or not an opposite sex comparator exists and this is the position even though the provisions of the Equality Act 2010 have not yet been amended.

3.4 Lloyds Banking Group Pensions Trustees Ltd case

On 26 October 2018 the High Court handed down Judgment in this case brought by the Lloyds Banking Group Pensions Trustees Ltd (the Trustee).

Lloyds Banking Group Pensions Trustees Ltd case:

Questions asked

The court was asked to determine in relation to the Lloyds Bank schemes:

- whether the trustee is required to equalise benefits between men and women to account for inequalities caused by GMPs that accrued after 16 May 1990

- if so, how it should do this. Is there one single correct method, and if not, how should the trustee achieve equalisation of benefits?

- other related issues, in particular: the requirement on the trustee to make back payments to members, if so back to what date, whether interest should be added to the back payments, and if so at what rate?

Equalisation and methods

The court found that the trustee is under a duty to equalise benefits for men and women so as to alter the result which is at present produced as a result of GMPs.

In relation to methods, the Judge considered those put forward from the viewpoint of the continuing operation of a pension scheme, and so did not address methods that might be suitable should the scheme be winding up or entering the Pension Protection Fund.

The Judge decided that a method which equalises each of the components rather than the overall pension ( “term–by–term” approach) is not required, so the trustee is not ‘required’ to use such a method.

The principle of minimum interference (which means the trustee needs to carry out only the minimum disturbance required to achieve equal pensions) means that the method referred to in the case as method C2 (the method whereby the scheme provides the better of a male or female comparator pension each year, subject to accumulated offsetting) is the only method that the trustee can unilaterally adopt (although the banks could choose to allow the trustee to adopt a different method if scheme rules permit).

Whilst the method DWP consulted on in November 2016 (referred to in the Judgment as Method D2) was not at the time of the Judgment available to be adopted as the banks had not consented as required by the conversion legislation, in principle the Judge said that the method is a lawful method to which the banks could consent.

In the subsequent judgment given on 6 December 2018 the Judge confirmed that it is not necessary, in order to implement method D2, to equalise benefits first in accordance with another method.

Method D2 permits the actuary to determine the higher of the actuarial equivalents of the unequalised female and the unequalised male pensions.

The higher of these actuarial equivalents is then used for the purposes of GMP conversion. This method, which is equivalent to the method DWP consulted on in 2016, is in principle a lawful method.

The court also clarified that it is for the actuary to determine what actuarial assumptions should be used for this purpose and the court would not give any ruling on this. (However, the GMP conversion legislation makes clear that the trustees are responsible for determining actuarial equivalence).

Application of conversion legislation to survivor benefits

There had also been argument as to whether the GMP conversion legislation used in method D2 enables conversion of survivor’s benefits already in payment, the Judge found that it does.

Arrears

The Judge also found that beneficiaries are entitled to receive arrears of payments due to them, for a period as governed by the rules of the schemes.

The Judge held that by virtue of section 21(1)(b) of the Limitation Act 1980 there is no relevant limitation period in relation to proceedings to recover arrears and that section 134 of the Equality Act 2010 is not effective in relation to proceedings by beneficiaries to recover arrears of payments where the trustee is in possession of trust assets, as section 134 offends the principle of equivalence in such a case.

He ruled that arrears of payments should in the Lloyds Bank case carry simple interest at 1% over base rate.

4. An outline of the DWP methodology

The 10 stage process outlined below results in the adjustment of an individual’s benefits to compensate for post 16 May 1990 GMP inequalities as well as conversion of all of the individual’s GMP.

The conversion aspect accords with the current GMP conversion legislation contained in sections 24A–H of the Pension Schemes Act 1993 and regulations 27–27A of the Occupational Pension Schemes (Schemes that were Contracted-out) (No 2) Regulations 2015 (SI 2015/1677).

This process was consulted on by DWP in November 2016 and was broadly welcomed by the pensions industry. Conversion was also held to be a lawful method for equalisation by the Judge in the Lloyds Bank case.

As explained in the response to the November 2016 consultation on a new methodology for equalising pensions for the effect of GMPs, government is considering changes to the GMP conversion legislation to clarify certain issues.

The guidance will be updated from time to time to reflect any changes to legislation that take place in the future and any material developments in case law.

4.1 GMP reconciliation and rectification

It is important that schemes are satisfied that they hold the correct GMP figure before resolving inequalities. Many schemes undertook a GMP reconciliation with HMRC over recent years so will have that assurance.

The service is now closed but schemes can check the GMP amount HMRC holds using the GMP checker service.

GMP Checker service

This service, which is available through the Pension Scheme Online service, automatically generates member and notional dependant GMP entitlements accrued between 1990 and 1997, and the GMPs that would have been accrued over the same period if the member were of the opposite sex.

Pre and post 1988 member and notional dependant GMPs are also calculated.

Weekly GMP figures are available at any dates between date of leaving (or notional date of leaving) and GMP age. Further information is provided in HMRC’s Countdown Bulletin 22.

There is also a slightly different service available through the GMP Checker service to obtain members’ contracted out dates and full earnings history.

The timing of any GMP rectification exercise (when benefits are adjusted prospectively and possibly retrospectively following reconciliation of scheme records) might usefully be aligned with that for addressing inequalities created by GMPs, especially if rectification is likely to generate benefit reductions.

The 10 stages of the process for resolving GMP inequalities through GMP conversion are described below.

The trustees may wish to contact all relevant parties, including the scheme administrators, before taking forward the process and setting the date for conversion, to ensure that their plans are achievable and do not create any unmanageable risks.

4.2 Stage 1 – Reach agreement with the employer

Section 24E (2) Pension Schemes Act 1993

The trustees agree with the employer in relation to the scheme that GMP conversion is to be undertaken. This consent extends to the terms on which benefits are to be converted as part of the conversion exercise (see Stage 2 below).

Where the participating employers have changed over the years, legal advice should be taken as to how (or whether) the consent requirement applies.

Employers will likely wish to understand both the conversion basis and the benefits to be converted given the potential impact on pension accounting of any basis mismatch.

4.3 Stage 2 – Select the members for conversion and agree which benefits are to be converted and the form of the new benefits.

Selecting the members

The trustees and the employer identify and agree which members will have their benefits “converted”.

The members selected could include survivors in receipt of GMP survivors’ pensions following the death of a previously contracted out member.

Common features of GMP inequality resolution work are as follows:

- there is no requirement to equalise for those who left active service before 17 May 1990 so they could be excluded if the motivation is equalisation only

- of those with service between 17 May 1990 and 5 April 1997, a significant proportion of members are likely to require no equalisation uplift

- for many of those who do need an uplift, the actuarial value of the uplift will be very modest, however, there could be some for whom the uplifts are significant

Trustees may wish to take advice in relation to members for whom the estimated cost of calculating and implementing equalisation is the same as or greater than the projected additional benefits to which the member would be entitled as a result of equalisation.

It is not necessary to convert benefits for all members, nor to convert at the same time. The legislation permits schemes to undertake conversion in stages for different groups or individuals if the trustees wish.

Agreeing the benefits to amend as part of the conversion process

A decision regarding which benefits will be amended as part of the conversion process will also be required.

Conversion requires that the trustees remove the GMP rules relating to the selected members, but for pre 1990 service it is not necessary to reshape either the GMP or the excess, as both can remain unequal.

However, conversion could mean that for some members all or a significant proportion of their accrued benefits will be re–shaped as part of the process, not just that relating to their 1990 to 1997 service for which equalisation is required.

For the avoidance of doubt, for a selected member, all of their GMP and the benefit which accrued alongside this GMP need to take part in the conversion process, not just that relating to 17 May 1990 to 5 April 1997 accrual.

GMP conversion may also be extended to those with GMPs who left prior to the Barber judgment, but for them there will be no need to undertake an equalisation step.

The description of the later stages of the process assumes that the benefits to be amended are limited to that part of pensionable service from 6 April 1978 up to 5 April 1997 during which the GMP that is being converted accrued.

We refer in this document to the selected benefits as the “benefits for conversion” or the “post conversion benefits”.

Deciding the form of the post conversion benefits

A decision regarding the form the post-conversion benefits will take will also be required.

There are explicit constraints in legislation regarding the form of post conversion benefits (See sections 24B and 24D of Pension Schemes Act 1993 and regulation 27A of S.I. 2015/1677).

In particular, the post conversion benefits:

- must be actuarially at least equivalent to the pre conversion benefits

- must not include money purchase benefits, apart from those provided under the scheme immediately before the conversion date

- must include survivors’ benefits in accordance with the provisions of the Act and Regulations

- for pensions in payment, the amount of pension to which a member had an immediate entitlement before the conversion must not be reduced as a result of the conversion

Survivor benefits

Post conversion schemes must currently provide the following on the death of a member (whether before or after attaining normal pension age):

- to a surviving widow – a pension equal to at least half the value of the pension to which the deceased member would have been entitled by reference to employment during the period 6 April 1978 to 5 April 1997

- to a surviving widower or civil partner – a pension equal to at least half the value of the pension to which the deceased member would have been entitled by reference to employment during the period 6 April 1988 to 5 April 1997

The circumstances in which and periods during which the converted scheme must provide the above survivors’ benefits are currently set out in regulation 27A of the Occupational Pension Schemes (Schemes that were Contracted-out) (No 2) Regulations 2015 (S.I. 2015/1677).

Trustees will need to ensure that such survivor benefits post conversion are provided on terms at least as generous as this.

Revaluation and indexation

Once conversion has taken place, the GMP rules will not apply to the converted benefits. This includes the revaluation and indexation requirements applicable to GMP benefits.

Other issues

Trustees are required to act in accordance with their fiduciary duties as pensions trustees, including when taking action to convert and equalise benefits and in taking decisions regarding the shape and form of the post conversion benefits within the scope of the conversion legislation.

Trustees will need to take advice on the proposed structure of the new benefits. If the benefits will be materially different in shape and form, the trustees may wish to consider giving the members options and if they do this, they may wish to consider if aspects of the Code of Practice for Incentive Exercises may be relevant.

4.4 Stage 3 – Set the conversion date

Section 24E (2) Pension Schemes Act 1993

The trustees and the employer agree the date at which conversion is to be effected (the “conversion date”).

4.5 Stage 4 – Pre conversion consultation

Section 24E(3)(a) Pension Schemes Act 1993

The trustees then write to the selected members to inform them of the proposed conversion and seek their views.

Consultation should be at a high level stating that:

-

they are proposing that:

- GMPs accrued during a specified period of pensionable service will be converted into non–GMP form

- the benefits that accrued alongside these GMPs will also be adjusted

- during the course of this process there will be a resolution of the GMP inequality issue

- although this process may result in changes to benefits, the member will experience no reduction in their overall actuarial value

- that more personalised information will be made available once calculations have been concluded and benefits adjusted

- the details of the person to be contacted if there are any questions, or comments

For the avoidance of doubt, the pre conversion consultation requirement in the conversion legislation is distinct from that required under the Pensions Act 2004 when a “listed change” is proposed by the sponsoring employer.

For deferred members, trustees may (if relevant) need to explain how the process has the potential to reduce the starting amount of some members’ pensions but that the value of the payments over an expected retirement length before and after conversion has been independently assessed to be the same.

Trustees are required to take all reasonable steps to consult members. When seeking to contact a member the usual steps a trustee would take when required to provide information to that member under the Occupational and Personal Pension Schemes (Disclosure of Information) Regulations 2013 (S.I. 2013/2734) are likely to be sufficient.

4.6 Stage 5 – Valuation

Section 24B (2) Pension Schemes Act 1993 and regulation 27 S.I. 2015/1677

The trustees instruct the scheme actuary to value for each selected member:

- the member’s benefits to be converted (along with attaching survivor benefits) – typically those in respect of that part of pensionable service up to 5 April 1997 (“amount A”) during which the GMP that is being converted accrued. Amount A is effectively the pre conversion, pre GMP equalisation value of these pre 1997 benefits.

- the member’s benefits (along with attaching survivor benefits) in respect of the same part of pensionable service (so typically up to 5 April 1997 during which the GMP that is being converted accrued), but assuming that for the period from 17 May 1990 to 5 April 1997 the GMP entitlement had been calculated as if they were of the opposite sex, with the excess over GMP being adjusted accordingly. This is “amount B”.

Both amounts A and B will be calculated as at the conversion date.

It will be necessary to value and compare the whole (non money purchase) benefit accrued in the selected period, not just the GMP, because members with a higher GMP will have a lower excess over GMP.

Depending on the benefit structure of the scheme (in particular rights to indexation and survivors’ benefits on the excess over GMP) a £1 of excess may be more or less valuable than a £1 of GMP.

For example, if the excess over GMP increases at 5% per year fixed, if the member has a higher GMP than their comparator, they may still need to have an inequality adjustment.

4.7 Basis to use

The valuation of amount A and amount B should be carried out on the same basis.

The trustees are responsible for determining the actuarial equivalence of the pre and post conversion benefits. In doing so, they must arrange for the scheme actuary to calculate the actuarial values of the pre and post conversion benefits.

The legislation does not specify what assumptions should be chosen.

However, the trustees are required to obtain and consider advice from the scheme actuary in deciding what assumptions are appropriate.

Trustees need to be aware that the choice of approach may substantially affect some members’ benefits, in particular where benefits increase at different rates pre and post conversion.

The trustees can, where they think it necessary, change their decisions as to what assumptions should be used.

In such a situation it is advisable that they take actuarial advice.

They may also wish to consider whether to discuss any changes with the employer. It will often be acceptable to use the scheme’s Cash Equivalent Transfer Value (CETV) basis or unisex equivalent as a starting point for a basis to calculate the value of the benefits, provided that no reduction based on the level of scheme funding is made.

Careful consideration should be given to any assumptions which are not unisex.

If unisex actuarial assumptions are used (even if the scheme is not using such an approach for its CETV basis) this will have the effect of ensuring that the individual’s converted benefits that relate to the 17 May 1990 to 5 April 1997 window period are identical to those of their notional opposite sex comparator.

If the CETV basis is to be used as a starting point for setting the conversion basis, it may well be necessary for the trustees to review the existing basis having taken actuarial advice to ensure that it is appropriate, given that such a basis might have been set having regard to those most likely to transfer, rather than all members with GMPs (which will include pensioners).

If so, this review would most likely be undertaken earlier in the process, such as at Stage 1.

If active members are to be converted the trustees will need to decide whether to have their benefits valued as either continuing in service, immediately leaving (at the conversion date), or a more complex calculation involving a scale of assumed probabilities of withdrawal at different ages.

It will also be necessary to decide what retirement date to assume, as again this can have a material impact.

For these purposes the trustees may wish to seek actuarial advice. The trustees may choose not to convert such members until they are no longer in pensionable service (similar issues arise for those no longer in pensionable service but who retain a salary link until such time as they cease to be in employment to which the scheme relates).

4.8 Stage 6 – Equalisation

Adjusting for the effects of unequal GMPs (so called “equalisation”) would be achieved as part and parcel of conversion by using a conversion value for each selected member which is the higher of amount A and amount B, in other words, the more valuable of the male or female benefit structure, thus encompassing the different male/female GMP entitlements.

4.9 Stage 7 – Conversion – determining the post conversion benefit

Section 24B (2)-(5) Pension Schemes Act 1993 and regulations 27 and 27A S.I. 2015/1677

Having determined the conversion value for the selected member in accordance with Stage 6, it is then necessary to turn it back into a revised pension benefit.

A consistent approach to the Stage 5 valuation should be used, so employing the scheme’s CETV basis, if this was used at Stage 5.

4.10 Stage 8 – Certification

Regulation 27(5) and (6) S.I. 2015/1677

The actuary will certify that the calculations have been completed and that the post conversion benefits are actuarially at least equivalent to the pre conversion benefits as equalised for the effect of GMPs.

This certificate, which should be in respect of all those covered in a specific exercise, must be sent to the trustees no later than 3 months after the calculations have been completed.

4.11 Stage 9 – Modification of scheme to effect conversion

Section 24G Pension Schemes Act 1993

The trustees may resolve to effect the conversion on the agreed basis.

Alternatively, they may use the scheme’s amendment power to enable GMP conversion, in which case Sections 67 to 67I of the Pensions Act 1995 are disapplied, in addition to which they may include amendments they think are necessary or desirable as a consequence of, or to facilitate, conversion.

4.12 Stage 10 – Post conversion notifications

Sections 24E(3)(b) and 24E (4) Pension Schemes Act 1993

The trustees must take all reasonable steps to notify the members and survivors (in the latter case, those with an immediate entitlement to benefits) whose benefits have been converted either in advance or as soon as reasonably practicable after the conversion date.

This notification should say that the benefits have been (or, will be if the conversion has not yet taken place) converted as at the conversion date.

They should be told what this means in terms of the amount and the shape of the benefit going forward. The date on which any benefits in payment will change (or have changed) should be included in the notice.

Again, when seeking to contact a member, the usual steps a trustee would take when required to provide information to that member under the Occupational and Personal Pension Schemes (Disclosure of Information) Regulations 2013 are likely to be sufficient.

Currently HMRC also needs to be notified on or before the conversion date that the individual’s GMPs have been or will be converted.

5. Detailed and practical aspects

This section examines some of the detailed aspects of the calculations discussed in Stages 5 to 7 of the methodology, before going on to consider data and processing issues.

The calculations described are just one implementation of the DWP methodology.

There may be other calculation approaches, involving GMP conversion, which are equally as valid.

5.1 The calculation methodology

The calculation methodology is best illustrated by reference to a deferred pensioner. It proceeds assuming that it is possible to segment the pre conversion benefits into potentially six service periods.

The scheme is assumed to have addressed sex-based inequalities in normal retirement age at some point between the Barber judgment on 17 May 1990 and the ending of GMP accrual on 5 April 1997.

These 6 service periods are as follows:

| Service period | GMPs | Age at which benefits can be taken | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pre 6 April 1978 | No GMPs accrued | Likely to have sex based differences |

| 2 | 6 April 1978 to 5 April 1988 | Pre–1988 GMPs accrued | Likely to have sex based differences |

| 3 | 6 April 1988 to 16 May 1990 | Post–1988 GMPs accrued | Likely to have sex based differences |

| 4 | 17 May 1990 to retirement equalisation day | Post–1988 GMPs accrued | The lower age would apply to the disadvantaged sex |

| 5 | Retirement equalisation date to 5 April 1997 | Post–1988 GMPs accrued | A unisex (and potentially new) age applies |

| 6 | 6 April 1997 onwards | No GMPs accrued | A unisex (and potentially new) age applies |

Having segmented the deferred pension as necessary, all of segments 2 to 5 that exist will be included in the conversion, not just the parts for which the GMP inequality issue needs to be addressed.

The projection part of the calculation is in 3 parts:

- Projected deferred pension

- Projected GMP

- Projected step up at GMP pension age

Projected deferred pension

The deferred pension needs to be projected to the assumed payment age.

This process may (depending on scheme rules and legislation) include:

- revaluation of the pension in deferment (possibly with different rates applying to different elements)

- late retirement uplifts on elements whose payment has been postponed

- early retirement reductions on elements that are not payable unreduced at the assumed retirement age

Projected GMP

The GMP also needs to be projected to the later of the GMP pension age (60 for women, 65 for men) and the assumed retirement age.

Any additional difference in pension increase rate is then allowed for from this point.

Projected step up at GMP pension age

A test is also carried out at the GMP pension age to see if there needs to be a step up at this point to ensure that the GMP is covered and satisfy any anti–franking requirements.

To address the GMP inequality it may only be necessary to examine the fourth and fifth benefit segments in the table above, giving an uplift where necessary. But as it will be necessary to convert all of the GMP, a value will also have to be placed on segments two and three as well (but there will be no inequality uplift on them as this is not required).

5.2 Opposite sex benefits

The same process as outlined in the section above is then carried out on those benefits in the fourth and fifth segment but assuming that the individual is of the opposite sex.

This involves using an opposite sex GMP and opposite sex ages at which these benefits can be taken.

5.3 Valuation of benefits

Each projected deferred pension segment at the unisex retirement age and the associated GMP adjustments are then valued as at the date of calculation.

The value of each benefit segment is added together to return the value of all the member’s benefits. Amount A is a subset of this being the value of those benefit segments in which a GMP accrued (benefit segments 2 to 5).

Trustees may wish to take advice about how to treat benefit segment 1 if in practice it cannot be separately identified.

Amount B is the sum of the value of the member’s second and third benefit segments and the opposite sex’s fourth and fifth benefit segments.

In some cases, it may be necessary to consider other segments to make appropriate allowance for the requirement that the GMP is covered and to satisfy any anti–franking requirements.

5.4 Conversion of benefits

The greater of amount A and amount B then forms a budget from which new benefits are costed to replace those benefits in which a GMP accrued.

The same basis is applied in reverse to generate a substitute deferred pension at date of leaving.

5.5 Active members

An active member might be treated as continuing in service, immediately leaving (at the conversion date) or a more complex calculation involving an assumed withdrawal scale could be used.

In the first case the effect of GMP inequalities is examined through looking at the comparator’s GMP at the projected retirement date.

In the second the differences are established at the conversion date before being rolled forwards as with the deferred pensioner calculation.

In considering which of the possible approaches to take trustees will need to consider their fiduciary duties and may also wish to seek actuarial and legal advice.

Treating them as if deferred brings in preservation law which may introduce complications.

The trustees may choose not to convert such members until they are no longer in pensionable service.

5.6 Pensioner members

Given the likelihood that current records in respect of many pensioners will not be detailed enough to establish their benefits directly on leaving pensionable service, pensioners will need to be converted through a more complex mechanism that takes as its starting point the pension currently in payment.

This pension and the associated GMP are rolled back, potentially in a number of stages, to when the individual left pensionable service, whether that is on retirement, or earlier, in order to estimate their benefits at this point.

The effect of GMP inequalities is then examined through looking at the comparator’s post 16 May 1990 GMP when pensionable service ceased and projecting benefits forward to the conversion date, again in potentially a number of stages.

In some cases, it may be possible to directly establish what the benefits were on leaving pensionable service from membership records, a forward projection would then only be required.

It is, of course, possible to use the conversion legislation only for say deferred pensioners and apply a different equalisation solution for pensioners.

Arrears payments

The backwards and then forwards process for pensioners discussed above only assesses the effect of GMP inequalities in respect of pension payments from the conversion date, it ignores the effect in relation to payments made before this date, including that arising from the exercise of options, such as the commutation of pension for lump sum, that might vary between the member and opposite sex comparator.

Allowing only for future payments in the conversion methodology is consistent with the follow up to the Lloyds judgment that was handed down on 6 December 2018 where the court made clear that, if using one of the methods referred to in that case as a “D” method, it can only operate for the future, and as to the past, one must adopt a different method.

One possible approach to taking account of past payments is to apply the method referred to in that case as “C2” in respect of these payments to generate an accumulation of arrears as at the conversion date.

Whichever method is used for past payments, regard should be had to the earlier judgment in the Lloyds Bank case which made clear that in that case:

- the arrears payments to take into account will depend on any limitations in a scheme’s rules, so trustees may need to take legal advice on this matter before finalising the methodology to be used to determine such arrears payments

- arrears of payments should carry simple interest at 1% over base rate

It would generally be expected that the accumulated arrears will be payable as a lump sum to the pensioner, but again, this is a matter on which the trustees may need to take legal advice.

Interaction of arrears payments with future payments

Where there are one or more “break even” points during the payment of an unequalised pension, such as points where the accumulated payments made to date in respect of one sex first fall below the accumulated payments made to date in respect of the other sex, a difficulty arises.

This is because application of what was referred to in the Lloyds Bank case as the “D2” method purely for future payments, whilst paying a lump sum to an initially disadvantaged member in respect of past payments potentially leads to unnecessary generosity in the conversion calculation for the initially advantaged member.

One way to address the issue could be to apply what was referred to as the “C2” method to generate both any arrears payments and to set up the pattern of future payments and then go on to apply the conversion legislation to the equalised future payments.

Another way to address the issue could be when applying the “D2” method for future payments, to use an actuarial value for the initially disadvantaged sex which nets off the arrears payments that the initially disadvantaged sex should receive.

This is a complex matter on which the trustees may wish to seek actuarial and legal advice.

Pension amount in payment not to immediately reduce as a result of conversion

For pensions in payment the amount of pension that a member had an immediate entitlement to before the conversion must not be reduced as a result of the conversion.

5.7 Persons who are survivors at the time of conversion

For persons who are survivors at the time of conversion, their pension is examined through a process akin to the mechanism for pensioners, only that the backwards process extends further back to when the original member left pensionable service.

The effect of GMP inequalities is then examined through looking at the post 16 May 1990 GMP that would have applied had the member been of the opposite sex, when pensionable service ceased and projecting benefits forward first to the original member’s date of retirement (if relevant), then to the date of death, then to the conversion date, potentially in a number of stages as relevant to the circumstances of the original member and the survivor.

Arrears

As with pensioners, the backwards and then forwards process for survivors assesses the effect of GMP inequalities only in respect of pension payments from the conversion date, it ignores the effect in relation to payments made before this date, including that arising from the exercise of any options by the original member, such as the commutation of pension for lump sum, that might vary between the member and those that would have applied had the member been of the opposite sex.

Account should be taken of past inequalities in an appropriate manner, recognising that past inequalities prior to the date of death relate to the original member and so might need to be paid to his or her estate.

The points made about how arrears payments are taken into account and accumulated in respect of pensioners, are also relevant for survivor pensions.

5.8 Benefits granted on transfer in

Trustees may wish to take legal advice on the position regarding conversion and equalisation of benefits granted on transfer in, such as a fixed additional pension, or added years of service.

5.9 Former members of the scheme

Trustees may also wish to take legal advice on whether any GMP inequality calculation should be undertaken in respect of those who are no longer members of the scheme, for example, because they have transferred out or died.

5.10 Data issues

Building a model that operates on the individual membership data likely to be available may give rise to practical difficulties.

The GMP starting point

If the starting point can only be the actual pre 1988 GMP and post 1988 GMP, this means that the derivation of the post 16 May 1990 GMP and the ratio of this with the opposite sex equivalent, both key considerations when it comes to quantifying the cost of the GMP uplift, will be approximate.

However, a sensible approximate approach is unlikely to result in material discrepancy in the vast majority of cases.

If there are concerns, one possible way of addressing it may be for schemes to obtain full earnings data and opposite sex GMP calculations from HMRC through its GMP checker service.

5.11 Other data shortcomings

Other data shortcomings may be more significant.

The trustees may wish to take advice on what to do for example, where:

- there is insufficient member data to be able to look back accurately in time so as to establish the member record when the GMP inequality first crystallised (on leaving pensionable service)

- there have been changes to the operation of the scheme over the years (such as that in relation to administrative practice and actuarial factors) impacting the calculation of benefits and options

- it is not clear what options and decisions a member might have taken in order to arrive at the pension they are currently receiving

All of these points might arise in relation to pensioners and survivors.

5.12 Scheme processing

Trustees will also need to ensure that any automated processes put in place to give effect to the conversion process are sufficiently developed to cater for the specific issues that may arise in relation to their scheme.

6. Pensions tax issues

There are a number of pensions tax issues that may arise where GMP inequalities are addressed regardless of which methods are used.

Under any of the dual record keeping approaches, the prospective start level of benefits may be subject to a positive correction (relative to what was originally thought to be the benefit), and the way in which they increase thereafter over time may alter as one or more switches take place in the future towards the level for the advantaged sex.

Under GMP conversion there is a one–off change to the start level and shape of prospective benefits, incorporating as just part of it the adjustment to underlying value from unequalised to equalised benefit.

Under any of the methods, for those whose benefits have crystallised, there may be an immediate adjustment in ongoing benefits with in many cases arrears to compensate for inequalities in payments already received.

Addressing GMP inequalities might have tax effects for scheme members and/or additional tax administration burdens for scheme administrators.

Issues could arise in the short term because members with a GMP in the relevant period may want to retire, take full cash out, transfer etc.

Trustees may, for example, want to pay out the “current benefit” with the possibility of a later adjustment, the amount (if any) not being known for some time.

The following is a list of pensions taxation areas that HMRC has confirmed it is considering:

- lifetime allowance

- lifetime allowance and other protections

- annual allowance

- lump sum payments

- transfers

These issues are being discussed with HMRC.

As noted in its Newsletter 106 HMRC will also provide more information and guidance on this through its pension schemes newsletters in the coming months.

7. Questions and answers

This section contains answers to some questions that have arisen in relation to the method we have proposed for equalising pensions for the effect of unequal GMPs.

Why not equalise or abolish GMPs instead?

GMPs were requirements provided for by legislation – the Pension Schemes Act 1993 – on pensions which were accruing between 6 April 1978 and 5 April 1997. As they relate to pensions which have accrued they cannot be changed retrospectively to make them equal, nor can they be abolished.

What legislation covers the process of converting GMPs into other scheme benefits?

The process is covered by sections 24A–H of the Pension Schemes Act 1993 and regulations 27-27A of the Occupational Pension Schemes (Schemes that were Contracted-out) (No 2) Regulations 2015 (S.I. 2015/1677).

Government is considering changes to the GMP conversion legislation to clarify certain issues. The guidance will be updated from time to time to reflect any changes to legislation that take place.

Which employer needs to approve the conversion?

The employer in relation to the scheme must consent to the conversion. Where the participating employers have changed over the years, legal advice should be taken as to how (or whether) the consent requirement applies.

Does the whole scheme have to be converted in one exercise?

No, the employer and the trustees can decide which members will have their benefits converted. For example, the employer may decide to convert deferred and pensioner members first, and wait until the active members become deferred members before converting their benefits.

What actuarial assumptions can be used to value the benefits that are being converted?

DWP considers that it would often be reasonable to use the assumptions used in CETVs as a starting point when undertaking conversion and equalisation having taken appropriate scheme-specific actuarial advice that the basis is suitable for this purpose.

However, trustees can seek advice on other ways of valuing benefits which may also be acceptable.

Can sex–based actuarial factors be used when valuing benefits?

If trustees use sex-based actuarial factors, the individual’s converted benefits that relate to the 17 May 1990 to 5 April 1997 window period will not be identical to those of their notional comparator of the opposite sex and so sex–based differences will remain. Given this, trustees may wish to seek legal advice before using sex–based factors.

Does an opposite sex comparator have to exist for an equalisation exercise to take place?

No. In line with the “Allonby” judgment, the government’s view is that an opposite sex comparator does not have to exist in order for an equalisation exercise to take place.

In the methodology for equalisation put forward in this guidance, the value of the benefits attributable to the member will need to be compared to the value of the benefits attributable had the member been of the opposite sex, and benefits based on the better of the 2 provided.

What about Defined Contribution schemes which provide GMP underpins and other similar schemes?

We are aware that a variety of schemes exist which are not set up on a traditional DB basis but which may promise to provide a GMP.

We cannot comment on how the methodology should apply to each and every scheme given these variations. It will be for trustees to decide how the methodology should be applied having taken their own legal advice.

What happens where the member cannot be traced?

When seeking to contact a member, the usual steps a trustee would take when required to provide information to that member under the Occupational and Personal Pension Schemes (Disclosure of Information) Regulations 2013 are likely to be sufficient.

For deferred members, what revaluation applies after conversion takes place?

Once conversion has taken place, the converted benefits will no longer be required to comply with the GMP rules.

Where back payments are required to address past periods where individuals have been underpaid, how far should back dating go?

Beneficiaries are entitled to receive arrears of payments due to them, for a period as governed by the scheme forfeiture rules unless overidden by legislation.

In the Lloyds case the Court ruled, by virtue of section 21(1)(b) of the Limitation Act 1980, there is no relevant limitation period in relation to proceedings to recover arrears.

What rate of interest should apply to arrears payable?

The Court ruled in the Lloyds case that arrears of payments in that case should carry simple interest at 1% over base rate.