Evaluating One Big Thing 2023: Technical report on the evaluation and our findings of the evaluation feasibility study (HTML)

Published 30 January 2025

Acknowledgements

Thank you to all the participants in this evaluation from across Government, who provided data through the online One Big Thing platform, and participants in Government People Group who completed pre- and post-assessments.

A group of Cabinet Office GSR colleagues completed this evaluation, supported by their line managers and senior leaders.

Evaluation data was collected in the platform provided pro bono by i.AI.

Executive summary

What was One Big Thing 2023?

- One Big Thing (OBT) is a new annual initiative in which all civil servants take shared action around a Civil Service reform priority. OBT 2023 focused on data upskilling and ran from September 2023 to December 2023. Forty-two per cent of all civil servants took part in OBT 2023, based on registrations on the online platform.

- The aims of OBT 2023 were:

- To create a practical moment of shared participation to reinforce that we are one Civil Service.

- To have a measurable uplift in data awareness, confidence, knowledge and understanding across the Civil Service.

- To have a long-term impact on participation in data and other training and initiatives.

- To contribute towards achieving better outcomes in the delivery of public services and policy through the use of data.

- OBT 2023 promoted data upskilling through 3 main activities:

- New online training materials available to the whole of the Civil Service.

- Allocating 7 hours of every civil servant’s time between September and December 2023 to self-directed data upskilling activities, with supporting resources.

- Asking all line managers to host an activity, conversation or team meeting focused on the use of data in their team’s day-to-day work.

Evaluating OBT 2023

- We carried out an evaluation to provide initial results on whether OBT 2023 met its aims. We surveyed all civil servants who took part in OBT 2023, and we also carried out a smaller case study evaluation in a single business unit.

- These evaluations assessed whether OBT 2023 had met its aims to create a shared moment of participation to reinforce that we are one Civil Service, and to have a measurable uplift in data awareness, confidence, knowledge and understanding across the Civil Service.

- We used pre/post tests to measure these aims. We administered a pre-survey and a post-survey to all civil servants who participated in OBT 2023. This survey asked questions about civil servants’ shared Civil Service identity, and their data awareness and confidence. We also asked them their views on OBT 2023 and their intentions to act after the training. We administered a data literacy and data behaviours assessment within one business unit, Government People Group. This complemented the cross-Civil Service evaluation by providing a more objective measure of changes in data literacy and behaviours.

- We also conducted a third study, which tested whether OBT 2023 could be linked to any changing trends in participation in data training. This was done using weekly attendance volumes of data training courses, extracted from the Civil Service Learning Platform.

- The overall evaluation was a feasibility study. We were using these evaluations to test out evaluation methods and learn lessons for the evaluations of future OBT events.

- Our evaluations had several limitations. One of the main limitations is that we did not have a comparison group, which means we cannot test whether OBT 2023 caused any changes we saw in participants’ Civil Service identity, data awareness, confidence and knowledge. Another limitation is that the participants in our evaluation are not representative of the Civil Service as a whole. This is because we were not able to use a sampling strategy to achieve a sample from which we could generalise to the wider Civil Service. Participants in our evaluation self-selected into the survey and assessment, which means they may be different to other civil servants, for example in their level of motivation and engagement with OBT 2023, data or evaluation. We will explain these limitations further in the report.

What did we find?

Aim 1: did OBT 2023 create a practical moment of shared participation to reinforce that we are one Civil Service?

- Overall, our evaluation results suggest that OBT 2023 did generate participation across the Civil Service.

- Forty-two per cent of the Civil Service registered for OBT 2023 on the formal, online platform. Eighty-two per cent of those who registered completed the initial online training modules. This means around 1 in 3 (34%) of the whole Civil Service both signed up and completed some training. Around 567,000 data learning hours were recorded on the official platform.

- Twenty-three per cent of those who registered for OBT 2023 recorded completing the target 7 hours of data upskilling (about 10% of civil servants). This suggests that many people who registered for OBT 2023 may not have completed the programme.

- We do not have any data on civil servants who may have participated in local OBT 2023 activities, such as team discussions, but did not register on the online platform, or registered but did not log the upskilling activities they completed, so the above figures may underestimate overall participation.

- We cannot say whether OBT 2023 was experienced as a “shared moment” based on our data. We asked civil servants about their identity as a civil servant and their sense of connection with other civil servants before and after taking part in OBT but the results were inconclusive and suggested OBT 2023 may not have had an influence on these issues.

Aim 2: did OBT 2023 lead to a measurable uplift in data awareness, confidence, knowledge and understanding across the Civil Service?

- Across the 2 studies, we found some very small positive improvements in participants’ data awareness, confidence and knowledge.

- We found very small increases in participants’ awareness of the relevance and use of data in their data-to-day roles during the period in which they participated in OBT. We also found very small increases in their confidence around data-related ideas (such as ethics) and activities (such as visualising data).

- In our case study, we found very small increases in civil servants’ ability to correctly answer some of the questions we set, which involved applying data to perform tasks (such as calculating something) and about key data-related concepts (such as averages).

- We also found small increases in reported use of data in writing and decision-making but did not find changes in all the data behaviours we asked about.

- Overall, this suggests that OBT 2023 may have resulted in some very small gains in participants’ data awareness, confidence and knowledge, including their ability to apply this knowledge to day-to-day work.

- It is important to emphasise that while the gains we found were statistically significant (for our sample), they were also very small. For example, participants’ average total number of correct answers in the data literacy assessment increased by less than one correct answer (from 6.3 to 6.9). Participants’ assessment of their data awareness and confidence on a 5- point Likert scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) increased on average by only 0.13 points.

- We also explored how relevant OBT 2023 participants found the training. Whether people found OBT 2023 to be relevant or not could help explain why they felt their knowledge, confidence and awareness had improved, or not, after taking part in the training. It could also give an indicator of how likely it was that their use of data in day-to-day work would change after taking part in OBT.

- On average, we found that people only moderately agreed that OBT was a good use of their time and that the content was relevant to their role. Participants moderately agreed that they were likely to apply learning from OBT 2023 to their roles, but recorded lower scores for their intention to complete specific actions such as booking further training or creating a personal development plan.

Aim 3: Did OBT 2023 have a long-term impact on participation in data and other training and initiatives?

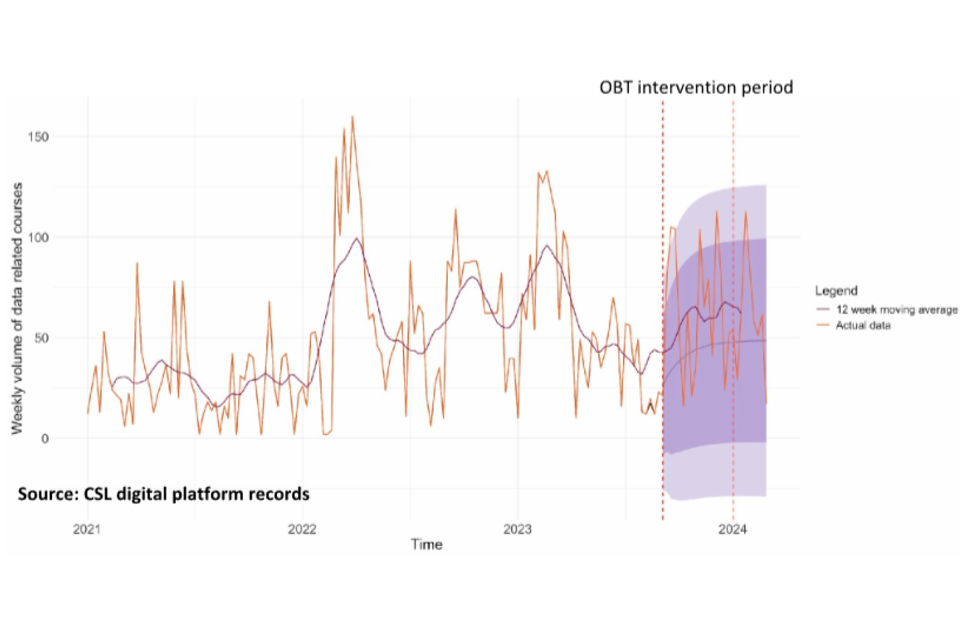

- Our findings for this aim were inconclusive. We did not detect a meaningful change in training courses attended when we analysed weekly volumes of data training courses hosted on the platform Civil Service Learning (CSL) during or immediately after OBT.

- We are unable to definitively say whether OBT was successful or unsuccessful in this aim. We could not capture courses or training undertaken outside of the CSL platform. This means we will not have included all the potential formal and informal training undertaken during the OBT intervention. It is possible that OBT led to an increase in these other training activities that we were unable to observe.

- It was also difficult to determine whether movements in the volume of data training courses attended during and after OBT were attributable to OBT due to the high weekly variance of the CSL data. This resulted in a wide forecast interval, meaning that we had greater uncertainty around the expected level of weekly volumes in the absence of OBT.

What are the lessons learned from our findings?

1. A training initiative such as OBT may be able to achieve very small increases in participant knowledge, awareness and confidence across a large number of civil servants.

- Our evaluations found very small improvements in data awareness, confidence and knowledge after taking part in OBT 2023. Even very small improvements may be valuable if they are achieved over a whole organisation. Previous evidence shows that small, but widespread, changes may offer greater value than an intervention that achieves large effects with smaller groups of colleagues.[footnote 1]

- Almost 220,000 civil servants took part in OBT 2023. As OBT matures as an annual initiative, and lessons are learned from implementation, it is likely that even higher participation rates could be achieved.

- There is much existing evaluation evidence that can be drawn on when planning future OBT events, focused on different reform priorities, to design an OBT with the best chance of achieving the highest possible impact with the largest possible group of people.

2. The design of future OBT events could do more to support people to apply new learning in their day-to-day roles.

- OBT 2023 took evidence-based steps to support people to apply learning to their day-to-day role by including line manager conversations and local, context-specific activities as part of the programme. This was a sensible place to start because these are relatively low-cost and simple to implement.

- Findings from the cross-Civil Service survey showed that there was still a gap between people’s general intentions to use learning from OBT, and their intention to take specific, practical action to do so. Not everyone found OBT relevant. Some small changes in people’s reported behaviours were found in our case study, but not across all behaviours.

- In planning future OBT events, further attention could be given to connecting the upskilling content to specific local work and goals, to help people apply new learning in their day-to-day roles.

- For example, this might include more scenario-based content in the training,[footnote 2] or providing evidence-based templates to support line managers help their teams embed the new skills within day-to-day work. These could include structured prompts and cues; action planning; self (or team) monitoring; and opportunities to continue to repeat the new skills within work.[footnote 3]

3. It is possible to evaluate OBT again in future, to gain even more extensive and robust evidence to support future delivery of OBT events and other upskilling initiatives.

- OBT 2023 was the first of its kind in the Civil Service. Our evaluation has provided some useful lessons learned for how evaluations of future OBT events could be carried out.

- Overall, our evaluations show that it is feasible to evaluate OBT. The relatively light touch methods we used (pre/post surveys and assessments) could be adapted, improved and used again to understand whether future OBT events achieve their aims.

- Other evaluation methods might also be considered, so the evaluation can be well-tailored to the strategic questions about OBT and Civil Service upskilling we need to answer. Planning and resourcing evaluation from the outset ensures that the widest possible range of suitable evaluation methods are available.

One Big Thing

One Big Thing (OBT) is a new annual initiative in which all civil servants take shared action around a Civil Service reform priority. OBT is sponsored by the Cabinet Secretary and is designed and implemented by the Modernisation and Reform Unit. There is an OBT senior sponsors’ network to ensure OBT meets the needs of the whole Civil Service, is feasible to implement locally, and delivers against its aims.

OBT 2023 focused on data upskilling, and ran from September 2023 to December 2023. The better use of data is a priority for government to improve our understanding of complex problems and to target policies and activities to deal with them. OBT 2023 was designed to boost these efforts and help ensure we remain a modern Civil Service able to use data effectively across all our roles.

Forty-two per cent of all civil servants took part in One Big Thing 2023 and 567,000 learning hours were recorded.

OBT 2023 promoted data upskilling through three main activities:

- New online training materials available to the whole of the civil service.

- Allocating 7 hours of every civil servant’s time between September and December 2023 to self-directed data upskilling activities, with supporting resources.

- Asking all line managers to host an activity, conversation or team meeting focused on the use of data in teams’ day-to-day work.

Online training materials

OBT gave all civil servants access to a new 90-minute data course delivered on the platform Civil Service Learning (CSL). The training was tailored to different levels of skill and experience, offering training aligned to 3 competency levels (awareness, working and practitioner level). Participants completed a pre-course assessment to direct them to the training most suited to their competency level.

Seven hours of self-directed data upskilling

Senior leaders and line managers encouraged every civil servant to spend 7 hours on self-directed data upskilling activities during the period in which OBT 2023 was live. To help civil servants access relevant materials, the online platform gave civil servants access to a catalogue of existing data training and resources, which had been checked for their quality and relevance by data and training experts. Most departments and professions also made materials and activities available that were tailored to their specific context. Data and digital skills have been a learning and development priority for several years, and previous cross-government communication campaigns have reinforced this priority and signposted materials available for upskilling on the Government Campus. Civil servants could record any data training they had done in 2023 as part of their 7 hours of OBT data learning.

Line manager conversations

After teams had completed the online data training, line managers were encouraged to hold conversations and run activities within their teams to reinforce data upskilling and its relevance to day-to-day work.

Delivering OBT across the whole Civil Service

To ensure the whole Civil Service could participate in OBT in a way that worked for them, a senior sponsors’ network was set up. This network met regularly and ensured OBT 2023 met the needs of the whole Civil Service, was feasible to implement locally, and was designed in the right way to deliver against its aims. Cross-Civil Service and local communications channels were used to get the message about OBT 2023 out to all civil servants and promote participation.

The aims of OBT 2023 were:

- To create a practical moment of shared participation to reinforce that we are one Civil Service.

- To have a measurable uplift in data awareness, confidence, knowledge and understanding across the Civil Service.

- To have a long-term impact on participation in data and other training and initiatives.

- To contribute towards achieving better outcomes in the delivery of public services and policy through the use of data.

In our evaluation of OBT we wanted to test whether the aims of OBT 2023 had been achieved. We also wanted to test out the feasibility of some evaluation methods, to learn lessons for future evaluations of OBT events and similar activities. The following sections set out the evaluation approach and methods, case studies, findings and recommendations.

Background to the evaluation of OBT 2023

Our modern Civil Service systematically evaluates its activities, using lessons learned to improve the quality of delivery and service to the public. Investing in evaluation, creating a system that incentivises testing openly and learning from our mistakes is crucial to fostering innovation. So it was important to use OBT 2023 to test out appropriate evaluation methods which would not only help us understand whether OBT 2023 had met its aims, but would also enable us to build an even higher quality evaluation for OBT 2024 and beyond.

The aims of the evaluation of OBT 2023 were:

- Develop and feasibility test evaluation methods for assessing whether OBT had met its aims. This will inform the planning of a full evaluation of OBT 2024 and future OBT events.

- Generate initial results on whether OBT 2023 had met its aims, to inform the planning of future OBT events.

To give us the best possible chance of testing out a range of appropriate evaluation methods, 3 Cabinet Office teams collaborated to deliver 3 evaluations of OBT:

1. Cross-Civil Service evaluation: an assessment of the extent to which civil servants who participated in OBT saw a change in measures linked to the aims of OBT during the period OBT was implemented (September to December 2023).

This evaluation used a pre- and post-survey. We asked questions about perceptions of shared Civil Service identity, data awareness, confidence and knowledge. The post-survey included additional questions about how likely participants were to apply new knowledge to their work and take further action based on the training. This evaluation was carried out by the Evaluation Task Force, supported by No. 10’s i.AI incubator unit, which designed and built the evaluation platform.

This evaluation is now complete and is reported in this document.

2. Case study evaluation: an assessment of how far civil servants within one business unit, Government People Group (GPG), saw an uplift in their data literacy and data behaviours during the period OBT was implemented (September to December 2023). We used a pre- and post-assessment where participating civil servants completed multiple choice questions that tested their data knowledge and skills, and asked them to report on concrete workplace behaviours related to use of data. This evaluation was carried out by the Government Skills and Curriculum Unit and the Civil Service Data and Insights Team.

This evaluation is complete and is reported in this document.

3. Evaluation of whether participation in data training increased as a result of OBT. We gathered regular data on the number of people who participate in centrally offered data training on the CSL platform. We used this data to carry out an interrupted time series analysis (a statistical analysis of trends over time), to investigate whether OBT achieved its aim to increase participation in data training. This evaluation was carried out by the Government Skills and Curriculum Unit and the Civil Service Data and Insights Team (both based in GPG).

The 3 teams involved collaborated on the design of the evaluation, quality assured one another’s work (as well as engaging additional peer review) and jointly developed the results and recommendations presented here.

The evaluations have several limitations, which means care needs to be taken when interpreting the results. These limitations are different for each evaluation, and are explained in each section of the report. An important limitation of both pre/post evaluations is that, due to the design of the intervention, there was no comparison group of civil servants who were not exposed to OBT. Therefore, we do not know whether any changes we saw in people’s responses to the survey or assessment reflect an existing trend, were a result of OBT, or were caused by other factors. This means that these evaluations can only provide tentative early evidence of whether OBT showed promise in achieving its aims. They do not provide robust evidence of the causal impact of the programme. This limitation is less of an issue for our third evaluation, as we are able to create an artificial comparison group using our forecasted trend. However, the lack of an observable comparison group still prevents us from fully isolating the effect of OBT from any other coinciding events. It therefore remains a limitation for all 3 evaluations to differing degrees. A full list of the evaluation methods we considered is outlined in Appendix 1.

The main process evaluation question we focused on for OBT 2023 was whether it had met its participation aims. The Modernisation and Reform Unit within Cabinet Office, which runs OBT, also ran a lessons learned exercise with departments to take forward insights for OBT 2024 and beyond. Some survey questions (not analysed as part of our evaluation) also contributed user insights, which formed part of this lessons learned exercise. This was an internal exercise that was not part of the evaluation and is not reported here.

We did not implement an economic evaluation of OBT 2023. This is because measuring the impact of OBT in a reliable way is a necessary first step in being able to quantify or monetise that impact and compare against costs.

The evaluations and their results

We will now report our 3 completed OBT 2023 evaluation studies:

- The cross-Civil Service evaluation.

- The case study evaluation carried out within GPG.

- The interrupted time series analysis carried out using Civil Service Learning training data.

Which OBT aims did we evaluate?

Our 3 evaluations considered whether OBT had met 3 of its 4 aims. These were:

1. To create a practical moment of shared participation to reinforce that we are one Civil Service.

2. To have a measurable uplift in data awareness, confidence, knowledge and understanding across the Civil Service.

3. To have a long-term impact on participation in data and other training and initiatives.

We were not able to evaluate one of OBT’s aims. This aim was:

4. To contribute towards achieving better outcomes in the delivery of public services and policy through the use of data.

This is a long-term and complex outcome which could not be captured within the scope and timescale of our evaluation.

Important background to all evaluations

We will explain the methods of each evaluation, the evaluation results and the limitations, to support interpretation of the results. At the end of the report, we discuss the results of all evaluations, and outline our recommendations for OBT 2024. Before this, it is important to highlight some important background information for the evaluations.

Was it ethical to carry out these evaluations?

All studies followed the code of ethics of the Government Social Research Profession throughout design data collection, analysis, reporting and data storage (see Appendix 13 for Government Social Research ethical checklists for all studies).

Before completing the cross-government survey and (within GPG only) the data literacy assessment, a data privacy impact assessment was created for each project. At the start of each survey we included an explanation of the purpose of the data collection and how participants’ data would be processed, stored and used so they could give informed consent (see Appendices 3 and 6). Though participation was encouraged, participants could withdraw at any time and anonymity was preserved in reporting. Participants were only asked to provide non-identifiable demographic data that was relevant to analysis (gender, grade and profession). We also collected participant email addresses to facilitate links between responses and learning records but data was fully anonymised before reporting.

We assessed that survey questions did not risk negative impact on participant wellbeing and did not require the disclosure of sensitive information.

Data will be securely stored for 3 years and then destroyed, consistent with government guidelines.

Quality assurance

We quality assured our analyses so that each team’s work was checked for mistakes or omissions and that it had been completed to a high analytical standard. This ensures that what we report here is accurate and that we are confident in the results we present.

We carried out our data analysis in the statistical software environment ‘R’. The 2 teams – the Evaluation Task Force and the Civil Service Data and Insights team – checked and cross-checked all code and outputs. A UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) policy fellow working in the Evaluation Task Force who had not been involved in either project performed a final review.

Quality assurance for the third study was undertaken by members of the Border Economic Team who had previous experience of forecasting.

Further information on the quality assurance process can be found in Appendix 10.

Statistical versus practical significance

Statistical significance has a specific meaning in statistics and evaluation. When we find a change to be statistically significant in an evaluation, we mean that we find it likely that the difference is non-random (not occurring by chance alone). Essentially, when we say a result is statistically significant it means an effect exists. Practical significance is different from this. This is how meaningful the effect we have found is.

We had a good chance of finding a statistically significant effect in our cross-Civil Service evaluation as we had a large sample size. In practical terms, though, we are most interested in whether this change is of a magnitude to be meaningful in practice. We also need to consider whether evidence we have gathered on a sub-group tells us anything about a wider population, even if we do find an effect within that sub-group. For example, we found a statistically significant effect within the GPG Business Unit, but this does not tell us anything about whether a similar effect exists within the wider Civil Service or not.

In our studies reported below, we will be trying to find out if there are statistically significant results, and we will also consider whether these results are practically significant.

Approaches to analysis

The approach to analysis for each study is described in further detail in the relevant sections below. One difference between the first 2 studies is that Study 1 (cross-civil service evaluation) examines mean responses to survey questions, while Study 2 (case study evaluation) examines medians and the distribution of responses. Means were appropriate to use as the basis of the cross-Civil Service evaluation due to the large sample size available. This meant there was less risk of mean responses being influenced by outliers than for the smaller sample size of the case study evaluation. This smaller sample size made the use of medians and distributional analysis more appropriate as the basis for analysis.

Study 1 - Cross-Civil Service evaluation of shared Civil Service identity and data awareness, confidence and knowledge

We now report Study 1. Additional information to support this section can be found in Appendices 3, 4 and 5.

Why did we carry out this study?

In this study we aimed to collect data on all civil servants who participated in OBT 2023. This allowed us to gather the broadest possible picture of whether OBT 2023 met its aims across the whole Civil Service, across a range of departments and grades.

This study was designed to provide evidence against 2 of the 4 aims of OBT 2023. The aims we measured were:

- To create a practical ‘moment’ of shared participation to reinforce that we are one Civil Service.

- To have a measurable uplift in data awareness, confidence, knowledge and understanding across the Civil Service.

Research questions

We developed 5 research questions (RQs) for this evaluation, based on the 2 aims we were measuring:

- How many people took part in and completed OBT training between September and December 2023?

- Did participants’ sense of shared Civil Service identity change after completing the OBT 2023 training?

- Did participants’ data awareness, confidence or knowledge change after completing OBT 2023?

- After participating in OBT 2023, did participants believe they could apply the learning to their day-to-day role?

- After participating in OBT 2023, did participants intend to do anything differently at work as a result of the OBT training?

Evaluation design and methods

This study used a simple pre/post survey design. This compares 2 measures taken at 2 time points, and assesses whether there has been a change (up or down). It does not capture any causal relationship between the intervention (in this evaluation, OBT 2023) and any change found in the measures and cannot explain why any change occurred.

Data collection

Civil servants[footnote 4] who participated in OBT were asked to complete a survey before they started the 90-minute online course. Once they had finished the 90-minute online course and recorded 7 hours of data training they were asked to take another survey. This used the same set of questions, plus some additional questions designed to give a richer picture of their experiences.

Survey questions were designed by the evaluation team to provide the information required to address the RQs. The survey questions are included in Appendix 3. The questions focused on participants’ shared identity as civil servants, and their data awareness, knowledge and confidence, before and after participating in OBT. Responses were recorded against a 5-point Likert scale, from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Additional questions in the post-survey asked participants about their experiences of the training and how they expected to apply the content in their work. These additional questions were tailored to the training level they had completed.

It is important to note that while survey items (questions) were designed to assess the main aims of OBT 2023, which we included in our RQs, this survey did not go through a validation process. A validation process checks that a survey is measuring what it is intended to measure, in a reliable and consistent way, based on specialist statistical tests. It was not possible to use a validated survey because the aims of OBT were bespoke. Additionally, it was not possible for us to validate our survey within the implementation timeline for OBT 2023, and given the costs and time involved in validation, it may not have been proportionate to do so, as the aims of OBT 2024 onwards are likely to be different. Since the survey is not validated, this means that we cannot be completely confident that changes seen in the survey data are equivalent to changes in the participants’ identity, data awareness, data confidence and data knowledge.

Surveys were built into the digital platform used to deliver OBT. This ensured that survey and participation data were collected and stored on the same platform. Both surveys were made available from 4 September 2023, the launch date of OBT 2023, and closed after OBT 2023 ended, in the first week of January 2024. The number of registrations and learning hours recorded were monitored throughout the duration of OBT.

In total, 218,583[footnote 5] responses were received for the pre-survey and 32,559 for the post-survey. In other words, about 15% of OBT participants completed the post-survey, which is equivalent to about 6.5% of the Civil Service as a whole.

Participants had to respond to the pre-survey to access the learning platform. This was because it was being used to direct participants to the right level of training. A Data Protection and Impact Assessment explained how the data would be used; if participants did not agree they could opt out of OBT. The post-survey was not mandatory and could be taken at any time. It was signposted to participants using a web link after they had logged 7 hours of training on the platform. This means that there is some variation in the time between the pre- and post-surveys for different participants. We cannot be sure of any effect this may have had, as participants could log any data training carried out during 2023 as part of their 7 hours, including training completed between January and August, before the launch of OBT. This means we do not know whether participants who completed the post-survey later had done more training than those who completed it earlier, or not. We also do not know whether people were already on an upward trend in their data awareness before OBT 2023, or not, which makes it more difficult to know whether it matters that some people took the post-survey later than others.

Approach to analysis

Different analytical approaches were used to address each of the research questions. This is detailed in Appendix 2.

Some survey items were not relevant to our RQs, so we excluded them from our analysis. These items were used by the OBT 2023 team as part of the lessons learned exercise.

We used tests of statistical significance to measure the likelihood that any differences between pre- and post-survey reflect actual differences over time in the population who responded to both surveys, rather than arising by chance. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests[footnote 6] were used because of the ordinal nature of the data. A Bonferroni adjustment was applied to each set of items analysed within RQ2 and RQ3. This correction ensures that we test for significance across multiple hypotheses, rather than individual ones, to reduce the risk of a type 1 error (rejecting the null hypothesis when it is actually true). It is important to emphasise that the methods we used do not allow us to conclude whether any statistically significant results we found in the sub-group who responded to both surveys would apply to the wider Civil Service population, but it is likely that they would not, due to the risks of non-response bias.

We only analysed data provided by participants who completed both the pre-survey and post-survey. This was because we wanted the pre- and post-groups to be comparable. This would not have been the case if we had analysed a much larger group of respondents for the pre-survey than the post-survey. Those who only completed the pre-survey, and not the post-survey, may be quite different to those who did complete the post-survey. For example, they may not have completed the training, and they may have different levels of motivation around data as a topic.

We removed data from those who stated that they undertook more than 1,000 minutes of training (17 hours). This was because this figure suggested that they had either made an error in reporting their participation, or they were very unusual and not typical of most respondents. This produced a final population of 31,437 who were included in the analysis (6% of civil servants). We carried out sensitivity testing to check whether the removal of these participants influenced the overall results. We concluded that it did not, as the differences in mean outcomes between the group we included and those we excluded were never more than 0.01 for any outcome measured.[footnote 7] Therefore, it was appropriate to remove this group’s data.

Results

For survey items which used a 5-point Likert scale, from strongly agree (5) to strongly disagree (1), mean scores of 3.1-5 can broadly be interpreted as agreement and mean scores of 1-2.9 can be interpreted as disagreement with the statement. Three is a neutral score (neither agree nor disagree), and responses close to 3 are also interpreted as neutral.

Research question 1 (RQ1)

How many people took part in and completed the training between September and December 2023?

In total, 218,583 people registered for OBT 2023 by completing the pre-survey. This equates to 42% of the Civil Service.[footnote 8] Of those, 178,857 completed the online modules, which is 34% of civil servants, and 82% of those who registered.

In all, 50,955 people recorded completing 7 or more hours of learning (9.8% of civil servants, and 23.3% of those who registered for OBT). This suggests high attrition (almost 75%) between sign-up and completion. However, it is not possible to account for any upskilling activities undertaken but not recorded.

Table 1 shows the number of participants recording different hours of data upskilling activities. The target was for all OBT participants to complete 7 hours of data upskilling activities.

Table 1: Hours of OBT training recorded by participants

| Hours recorded | Number recording hours, of post-survey sample | Number recording hours, total |

|---|---|---|

| Less than 1 hour¹ | 1,635 | 96,832 |

| 1+ hours | 4,263 | 35,429 |

| 2+ hours | 1,967 | 13,678 |

| 3+ hours | 1,153 | 8,141 |

| 4+ hours | 990 | 6,013 |

| 5+ hours | 667 | 4,200 |

| 6+ hours | 536 | 3,335 |

| 7+ hours | 20,226 | 50,955 |

| Total | 31,437 | 218,583 |

Source: One Big Thing 2023 pre and post-surveys

Notes:

- The online training took 1.5 hours to complete. Therefore, in principle, participants should not have recorded less than 1 hour of training. Possible explanations for why some participants recorded less than 1 hour of training are: they mistakenly did not count the 1.5 hours of online training they had completed, they completed this more quickly than expected, or they completed the post-survey before they had recorded any learning hours.

Research question 2 (RQ2)

Did participants’ sense of shared Civil Service identity change after completing the OBT 2023 training?

Our results are inconclusive, and on balance suggest that, overall, there was very little change in civil servants’ shared identity after participating in OBT 2023.

There was a very small numerical decrease in participants’ connection to the wider Civil Service after OBT (mean = 2.97 in the pre-survey and 2.94 in the post-survey). A greater number of civil servants agreed that their identity as a civil servant was important to them in the pre-survey, and there was a very small increase in this figure in the post-survey (mean = 3.61 in the pre-survey and 3.67 in the post-survey). As all scores were close to 3, overall participants’ views were relatively neutral on this issue.

These measures are not specific to the OBT content, nor are they closely related to data literacy more generally. There would be a range of factors influencing respondents’ sense of connection to the wider Civil Service and their sense of Civil Service identity. Therefore, it is particularly difficult to assess whether OBT had any specific influence on these measures.

Results therefore suggest that, for the participants who completed our surveys, it is inconclusive as to whether OBT 2023 created a practical ‘moment’ of shared participation to reinforce that we are one Civil Service.

Figure 1: Bar chart showing results of pre- and post-tests for RQ2

| Question theme | Pre | Post |

|---|---|---|

| Connection with other Civil Servants | 2.97 | 2.94 |

| Identity as a Civil Servant | 3.61 | 3.67 |

Likert score: 3

Source: One Big Thing 2023 pre- and post-survey

Notes:

1. Sample size: 31,437

2. Figure 1 based on responses to survey questions (see Appendix 3):

a. Connection with other civil servants: 2a

b. Identity as a civil servant: 2b

3. After applying Bonferroni correction, all pre/post comparisons included in this figure were found to be statistically significant at the 95% level or higher. This is expected given the large size of the sample in this study.

Research question 3 (RQ3)

Did participants’ data awareness, confidence or knowledge change after completing OBT 2023?

Four survey questions tested whether participants reported changes in their data awareness, confidence and knowledge. We asked one survey question which tested participants’ self-reported awareness of how data could support their day-to-day role. As shown in Figure 2, before starting OBT, participants perceived themselves to have a positive awareness of how data could support their day-to-day role (mean = 3.98), and there was a very small increase in this measure after completion of OBT (mean = 4.12).

There were also very small increases in participants’ agreement that data was relevant to their role (from 4.12 to 4.18) and that they were aware of how data could support their day-to-day role (from 3.98 to 4.12). There was a slightly larger increase in participants’ agreement that they knew how to use data effectively day to day (from 3.83 to 4.04). These results should be read in the context that the participants’ baseline scores were already relatively high.

Figure 2: Bar chart showing results of pre- and post-tests for RQ3

| Question theme | Pre | Post |

|---|---|---|

| I know how to use data effectively in my day-to-day role | 3.83 | 4.04 |

| I am aware of how data can support my day-to-day role | 3.98 | 4.12 |

| I think data is relevant to my role | 4.12 | 4.18 |

| I feel confident about using data in my day-to-day role | 3.88 | 3.99 |

Likert score: 3

This bar chart shows the scores out of a maximum 5 from before and after completing OBT. “Perceived Data Awareness and Relevance” shows small increases in mean scores from before to after completing OBT. “Data is relevant to my role” increased from 4.12 to 4.18, “I am aware of how data can support me day-to-day” rose from 3.98 to 4.12, and “I know how to use data effectively day-to-day” went from 3.83 to 4.04. Baseline scores were already relatively high, ranging from 3.83 to 4.12 before OBT.

Source: One Big Thing 2023 pre- and post-surveys

Notes:

- Sample size: 31,437

- After applying Bonferroni correction, all pre/post comparisons included in this figure were found to be statistically significant at the 95% level or higher. This is expected given the large size of the sample in this study.

There were 12 other survey questions which provided insight into participants’ self-reported data awareness, confidence and knowledge, as shown in Figure 3. These questions only appeared in the post-survey, so do not tell us anything about changes throughout OBT 2023. The questions asked participants to rate to what extent they agreed that different areas of their data awareness, confidence and knowledge had improved as a result of OBT.

Average participant responses ranged from 3.55 for communicating data more confidently to 3.81 for learning about the importance of evaluating outcomes of data-informed decisions. Overall, participants therefore moderately agreed that their data awareness, confidence and knowledge had improved as a result of OBT.

Figure 3: Bar chart showing results of post-test insights for RQ3

| Question theme | Post |

|---|---|

| I have a better understanding of data ethics | 3.80 |

| I have a better understanding of how to quality assure data and analysis | 3.74 |

| I understand better how to communicate data insights effectively to influence decisions | 3.76 |

| I feel more confident to use data to influence decisions | 3.61 |

| I can communicate data information more confidently to influence decisions | 3.55 |

| I have learned about importance of evaluating outcomes of data-informed decisions | 3.81 |

| I have a better understanding of what data means | 3.79 |

| I know more about how different data analysis techniques can be used to understand data | 3.74 |

| I understand better how to critically assess data collection, analysis and the insights derived from it | 3.72 |

| I know more about visualising and presenting data in a clear and concise way | 3.75 |

| I am better at interpreting data | 3.56 |

| I understand better how to anticipate data limitations and uncertainty | 3.74 |

Likert score: 3

The bar chart presents 12 survey questions about improvements in data awareness, confidence, and knowledge after completing OBT 2023. Mean scores range from 3.55 to 3.81, indicating moderate agreement. The highest-rated item at 3.81 was “I learned about the importance of evaluating outcomes of data-informed decisions.” The lowest-rated at 3.55 was “I can communicate data more confidently to influence decisions.” Other items covered understanding data quality, identifying actionable insights, connecting data to real-world outcomes, and feeling more confident working with data. These are post-survey results only; no pre-survey comparison is available.

Source: One Big Thing 2023 post-survey

Notes:

- Sample size: 31,437 (Awareness: 10,525; Working: 15,190; Practitioner: 5,722)

Research question 4 (RQ4)

After participating in OBT 2023, do participants believe they can apply the learning to their day-to-day role?

Three post-survey questions tested participants’ beliefs about applying the learning to their day-to-day role following completion of OBT training. As shown in Figure 4, mean scores were consistent across each question, ranging between 3.44 and 3.46. This shows moderate agreement that participants believed they could apply the training to their day-to-day roles.

Figure 4: Bar chart showing post-tests for RQ4

| Question theme | Post |

|---|---|

| More interested in working with data day-to-day | 3.46 |

| Improved understanding of how to use data day-to-day | 3.44 |

| Content was relevant to their role | 3.44 |

A bar chart displays mean scores for three post-survey questions assessing participants’ beliefs about applying OBT learning to their daily work. Scores are consistent across items, ranging from 3.44 to 3.46, indicating moderate agreement. The questions asked about confidence in applying learning (mean=3.46), having a clear understanding of how to apply learning (mean=3.44), and having identified opportunities to apply learning in their role (mean=3.45). Results suggest participants moderately believed they could apply the training to their day-to-day work. No pre-survey data is available for comparison.

Likert score: 3

Source: One Big Thing 2023 post-survey

Notes:

- Sample size: 31,437 (Awareness: 10,525)

- Figure 4 based on responses to survey questions (see Appendix 1):

a. More interested in working with data day-to-day – Awareness a-iii

b. Improved understanding of how to use data day-to-day – 7a-ii

c. Content was relevant to their role – 7a-iv

Research question 5 (RQ5)

After participating in OBT 2023, do participants intend to do anything differently at work as a result of the OBT training?

Six post-survey questions tested participants’ intentions to behave differently following completion of OBT training. As shown in Figure 5, there were a range of scores for this domain. This ranged from 2.83 for intention to find or become a mentor, representing moderate disagreement, to 3.55 for intention to apply learning to their role, representing moderate agreement. Overall, there is a mixed picture here, with slightly higher scores for reported general intention to take action, and slightly lower scores for reported intentions to complete specific actions; for example, a score of 3.40 for intention to participate in further training versus a score of 3.13 for intention to book training.

Figure 5: Bar chart showing post-tests for RQ5

| Question theme | Post |

|---|---|

| Intend to participate in further training | 3.40 |

| Intend to apply the learning in their role | 3.55 |

| Intend to find or become a mentor | 2.83 |

| Intend to create a development plan | 3.10 |

| Intend to book training | 3.13 |

| Intend to add learning to development plan | 3.34 |

Likert score: 3

A bar chart shows mean scores for six post-survey questions about participants’ intentions to behave differently after completing OBT. Scores varied, ranging from 2.83 to 3.55. The highest score of 3.55 was for “I intend to apply my learning to my role,” indicating moderate agreement. The lowest score of 2.83, suggesting moderate disagreement, was for “I intend to find/become a mentor.” Other items included general intention to take action (mean=3.48), participating in further training (mean=3.40), reviewing the OBT Hub (mean=3.28), and booking training (mean=3.13). Results present a mixed picture, with slightly higher scores for general intentions and lower scores for specific action items. Pre-survey data is not available for comparison.

Source: One Big Thing 2023 post-survey

Notes:

- Sample size: 31,437

- Figure 5 based on responses to survey questions (see Appendix 3):

a. Intend to participate in further training – 7a-iii

b. Intend to apply the learning in their role – 7a-v

c. Intend to find or become a mentor – Awareness b-iv / Working d-iv / Practitioner f-iv

d. Intend to create a development plan – Awareness b-i / Working d-i / Practitioner f-i

e. Intend to book training – Awareness b-iii / Working d-iii / Practitioner f-iii

f. Intend to add learning to their development plan – Awareness b-ii / Working d-ii / Practitioner f-ii

We also explored whether OBT 2023 participants found the training relevant or not. This could help explain why they felt their knowledge, confidence and awareness had improved, or not, after taking part in the training. It could also give an indicator of how likely it was that their use of data in day-to-day work would change after taking part in OBT, and whether they went on to take further data training after OBT. On average, we found that people only moderately agreed that OBT was a good use of their time and that the content was relevant to their role.[footnote 9]

Discussion

Across our five main research questions, we found the following results:

1. RQ1: in total, 218,583 civil servants signed up for OBT by completing the pre-survey. This accounts for 42% of the Civil Service. Of these, 178,857 staff completed the online modules (34% of civil servants) and 50,955 recorded more than 7 hours of learning (9.8% of civil servants). We received 32,559 responses for the post-survey, of which 20,226 (64.3%) recorded more than 7 hours of learning. These results do not capture any civil servants who may have completed OBT-related activities in their departments, but did not register on the online platform.

2. RQ2: results are inconclusive, and suggest overall that there was very little change in civil servants’ sense of shared identity after participating in OBT 2023.

3. RQ3: we found very small increases in survey participants’ self-reported data awareness, confidence and knowledge after participating in OBT.

4. RQ4: we found moderate agreement that participants believed they could apply the content of OBT 2023 to their day-to-day roles. Again, this reflects participants’ perceptions, and is not a measure of whether they did apply the learning to their work.

5. RQ5: results ranged from moderate disagreement through to moderate agreement that participants intended to behave differently as a result of OBT training. This range in scores suggests there may be a gap between participants’ general ambitions after OBT and their commitment to take practical steps to implement them. Again, this is a measure of perception and intention, not a measure of whether participants did take any action.

Limitations

Our evaluation did not include any non-OBT comparison group. The methodology, based on pre/post responses from a non-representative sample of civil servants, was not designed to allow us to isolate the impact of OBT relative to other factors or pre-existing trends. These results instead tell us whether average responses changed over time in this group, but without being able to disentangle whether any observed changes were due to OBT or something else.

The sample is not a probability sample, and therefore cannot be generalised to all civil servants. Our sample included only those participants who completed the pre-survey and the post-survey. Post-survey responses were substantially lower than the pre-survey, and are likely to represent those who were most engaged with OBT 2023, and thus more motivated to complete the survey. Together, this means the overall sample is likely to overestimate the changes resulting from OBT. This is important to note, given the magnitudes of changes we found were very small, and the levels of agreement with the statements generally fell below 4 (agree) in most cases.

Survey responses captured self-reported change rather than objective changes in data awareness, confidence or knowledge. These types of self-reported measures can often be subject to an optimism bias (participants overestimate their knowledge or skill). As the surveys only covered the period where One Big Thing was live, longer-term outcomes cannot be assessed. The insight that can be gained from measuring short-term self-reported outcomes is limited.

We do not have pre- and post-measures available for all survey domains, meaning evidence is weaker against some of the research questions (RQ4 and RQ5).

The survey was not validated. This means there is a chance that some items do not in fact measure the constructs (OBT aims) they were intended to. This is a risk with any survey instrument that has not been through a validation process to confirm that the survey items measure what is intended.

Analysis has focused on mean changes, not distributional effects. The mean does not tell us about the spread of the data, for example whether there were a lot of participants with neutral responses, or very extreme responses in both directions.

Study 2 - Case study evaluation of whether OBT met its aims within Government People Group, Cabinet Office

Why did we carry out this evaluation?

A limitation of the cross-Civil Service evaluation was that the assessment only measured attitudes and confidence, rather than taking an objective measure of data knowledge, skills (in this report we refer to these 2 ideas together as data literacy) and behaviours. We ran a smaller scale, second evaluation within GPG to pilot a more objective measure of data literacy and behaviours. Data literacy links to OBT’s second aim: a measurable uplift in data awareness, knowledge and understanding.

The objective was not to evaluate whether OBT met this aim across the Civil Service, but to run a smaller scale evaluation to see how feasible it was to evaluate gains in data literacy and behaviours (rather than only confidence and attitudes) in a valid way, to inform future evaluations.

Research question

Our research question was:

Is there a measurable uplift in data literacy and behaviours for this business unit sample during the period coinciding with OBT?

Evaluation design and methods

The population for this case study evaluation was GPG. This group was chosen as a case study population for convenience as the GPG Executive Committee wanted to carry out an evaluation of OBT that went beyond the cross-Civil Service evaluation. GPG consists of 966 members of staff mostly in HR, policy, data and digital professions. Everyone was issued with a request to complete either the pre- or post-assessment, regardless of their intention to participate in OBT (for the pre-test) or their participation in OBT (for the post-test).

We used a simple pre/post assessment design, using a data literacy assessment administered to GPG at the start of OBT 2023 (September 2023) and the end of OBT 2023 (December 2023). By using the same assessment at the beginning and end, we could measure any average changes in scores. We decided to include the whole of GPG as the evaluation population based on power calculations, which showed us we were likely to need around 200 participants to be able to detect a statistically significant effect in our data. This assumed that OBT may have a moderate effect on data literacy.

To improve the rigour of this design, we randomised GPG into 2 groups, where one group was invited to complete the pre-test in September and one group was invited to complete the post-test in December. The reason for this was to remove the risk that people would score more highly on the post-assessment only because they had already completed the assessment once before, and not because their data literacy had genuinely improved. It also offered the best possible chance of getting a high response rate, as it is common for people to opt into the first test in a design like this in higher numbers than the second test (as we saw with the cross-Civil Service design). It is important to note this is not a randomised control trial design. The randomisation in the timing of test administration was used to remove a risk of test-retest bias, but there was no manipulation of OBT roll out and no comparison group.

This evaluation measured whether there was a statistically significant uplift in data literacy and behaviours within the group of GPG colleagues who responded to the request to complete an assessment. We cannot be certain that the measure we take of any changes within this group of people would be the same as a measure for the whole of GPG because of the large risk that people who chose to complete the assessment are systematically different to those who did not (for example, in terms of their motivation, or engagement with OBT), influencing their scores.

The evaluation does not measure whether any changes we detect are attributable to OBT. Colleagues who responded to the request to complete an assessment were exposed to all aspects of OBT 2023, including internal communications about OBT, being able to register for the online course content and potentially participating in individual or collective OBT-related data training. They may have also been exposed to other data content and activities unrelated to OBT 2023, and may already work with data in their roles. Their data literacy and behaviours may already have been improving before the launch of OBT 2023. Our evaluation measures any change in data literacy, which could be due to any of these influences, as well as others we may not be aware of. Our evaluation does not tell us whether OBT itself caused any changes we see in the data. Additionally, GPG delayed its OBT start date to 4 October, one month after the start for the wider Civil Service. There is therefore a possibility that members of GPG may have been exposed to some aspects of OBT prior to taking part in the pre-assessment.

Data collection

Data literacy and behaviours assessment

We designed a bespoke data literacy and behaviours assessment for this evaluation as we were not able to identify a suitable existing data literacy assessment (having carried out a scoping exercise to determine if any were aligned with the aims of OBT 2023 and our evaluation requirements). We used the OBT training programme as a guide to what we should assess and research on what constitutes data literacy.[footnote 10],[footnote 11]

We also used factor analysis to check construct validity (that the questions were measuring the aspects of data literacy we expected them to measure) and to increase our confidence that the 11 individual questions we included measured one common construct – data literacy. This approach meant that even though we were not able to fully validate our assessment within the OBT 2023 implementation timeline, we had the best assessment possible within those constraints.

The final assessment included 16 questions. Five behavioural questions focused on data use in day-to-day work. Eleven data literacy questions focused on foundational data ideas, such as which method of averaging is least affected by outliers, and simple mathematical questions which required data manipulation (see Appendix 6). Performance on the 11 data literacy questions were combined into one measure of data literacy.[footnote 12]

We collected information on grade (seniority), profession and gender to enable us to check whether the pre- and post-samples were balanced, check for risks of non-response bias, and assess how similar or different our GPG sample was to the rest of the Civil Service. Participants provided their email addresses to allow us to cross-reference their assessment response with their participation data. We also asked respondents to tell us whether they had participated in the core OBT digital learning. This information helped us to work out whether the group who responded to our assessments were substantially different from the wider GPG directorate. This will help us consider how generalisable our results might be to GPG more widely.

To maximise the statistical power our evaluation method could achieve (the likelihood we could detect a statistically significant effect), it was vital to encourage uptake. This involved repeat emails from both the Civil Service Data and Insights team and the senior leadership of GPG. During the post-assessment collection period, we sent a business unit-wide email to try to maximise uptake, as well as an article in the GPG newsletter. These messages were also reinforced in team communications (for example, team meetings), and cascaded from the senior leadership of GPG, through line managers.

Assessment roll out

We randomised GPG into 2 groups and issued the pre-assessment to one group and the post-assessment to another group. The reasons for this approach were to reduce the risk of test-retest bias, as explained above. The assessment was issued using the Qualtrics survey platform. The pre-assessment was issued to Group One before OBT 2023 was formally launched in GPG, and was open for 23 days. The post-assessment was distributed to Group 2 mid-way through OBT 2023, and was open for 45 days.

The pre-assessment and post-assessment were distributed to 914 members of GPG staff in total, with approximately half of this group of 914 people receiving each assessment. Of the invitations sent, 42 emails were undelivered and so the final population was 872. A total of 392 participants received the invitation to complete the pre-assessment and 479 received the invitation to complete the post-assessment.[footnote 13]

Respondents

In total, 288 people completed the assessments. 190 completed the pre-assessment, and 96 completed the post-assessment. The overall completion rate was 33%, but with a much higher completion rate for the pre-assessment (48.1%) than the post-assessment (20.3%).

Approach to analysis

For the behaviour questions we measured the changes between the pre and post-assessment by comparing median scores for the questions about the use of data for analysis and in discussion, and the percentage of respondents answering ‘yes’ for reported use of data in decisions and in writing.

For the literacy questions we measured the difference between pre- and post-assessments for 3 measures:

- The overall percentage of correct answers.

- The raw scores for the set of literacy-based questions as a whole.

- Differences in score for individual questions.

For each of these measures, we checked whether the results were statistically significant, meaning we checked whether there was a strong probability that they measured real changes in the participants who responded, rather than occurring by chance. For the third set of calculations (differences in score for individual questions) there is a risk we found false positives (so, we found a statistically significant effect where one does not exist) because we ran multiple statistical tests concurrently. For this reason, when discussing the results, we focus mainly on overall scores rather than individual questions. Further discussion of this issue can be found in Appendix 12.

T-test and Chi-squared tests were used to check for differences in the means and distributions for the data literacy questions. We used Wilcoxon ranked-sum and Chi-square tests for the 5 behaviour questions. Further details on our analysis approach can be found in Appendix 11.

Results

Data behaviours

We found a statistically significant increase of 13.6 and 14.1 percentage points for “Yes” responses in participants’ reported use of data in making or suggesting decisions, policy or strategy and their reported routine inclusion of data, facts or numbers in writing/policy recommendations (assessment questions 4 and 5).

Questions 1 to 3 (see Table 2 below) measured the use of data in day-to-day work. We found statistically significant changes in the distribution of responses for questions 1 and 2. This may appear to be a puzzling result, as question 1 saw no change in median response, and question 2 saw only a modest increase, from 2 to 3. This is because the statistical test we used measured the change in the distribution of responses (so, the number of people giving each response), not only the change in the median score. We found no statistically significant difference for question 3. These results are illustrated in Table 2.

While we found a difference between the pre- and post-distributions for questions 1 and 2, which is likely to be non-random, the relatively small change in median responses make the practical significance of these results uncertain.

Table 2: Data behaviours pre/post comparison results

| Question | Median response pre | Median response post | Statistically significant difference? |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1) How many data reports, dashboards or visualisations have you interacted with in the last week? | 3 | 3 | Yes |

| 2) How many times this week have you discussed data trends, metrics or insights with colleagues? | 2 | 3 | Yes |

| 3) How many hours this week did you spend analysing, manipulating or interpreting data as part of your regular job functions? | 2 | 2 | No |

| 4) Have you made or suggested a decision, policy or strategy based on data analysis in the past week? | 45.8 | 59.4 | Yes |

| 5) Do you routinely include data, facts or numbers in your writing/policy recommendations? | 68.2 | 82.3 | Yes |

Source: One Big Thing 2023 GPG assessment

Notes:

- Sample size: 190 in the pre-assessment, 96 in the post-assessment.

- Table 2 based on responses to survey questions 1-5 (see Appendix 6 and 11 for more detail).

Data literacy

We found an increase of 6.3 percentage points in the average percentage of correct answers between the pre- and post-assessments. This corresponds to an increase of 0.7 out of a possible score of 11, from 6.26 to 6.95. The increase is statistically significant and suggests that, overall, there was a very small but detectable increase in assessment participants’ data literacy across the period in which OBT 2023 took place. See Figure 6, below, for a visual representation. While we are confident that the results demonstrate that there was a very small, non-random change in overall literacy and numeracy scores across our 2 samples, this evaluation cannot tell us whether OBT 2023 had an influence on these scores, nor whether this trend was similar or different to any trends in data literacy that might have already existed prior to the period we studied.

Figure 6: Bar chart showing average scores out of a possible score of 11 in pre- and post-periods

| Average score | Pre | Post |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 6.3 | 6.9 |

The bar chart compares the average percentage of correct answers on data literacy assessments before and after OBT 2023. The pre-assessment average was 56.9% (6.26 out of 11), while the post-assessment average increased to 63.2% (6.95 out of 11), a statistically significant rise of 6.3 percentage points. This suggests a small but detectable improvement in participants’ data literacy over the period of OBT 2023. However, the evaluation cannot determine if OBT directly influenced these scores or if the trend differed from any pre-existing data literacy trends. Caution should therefore be used when interpreting the results.

Source: One Big Thing 2023 GPG assessment

Notes:

- Sample size: 190 in the pre-assessment, 96 in the post-assessment.

- Figure 6 based on overall responses to survey questions (see Appendix 6 and 9 for more detail).

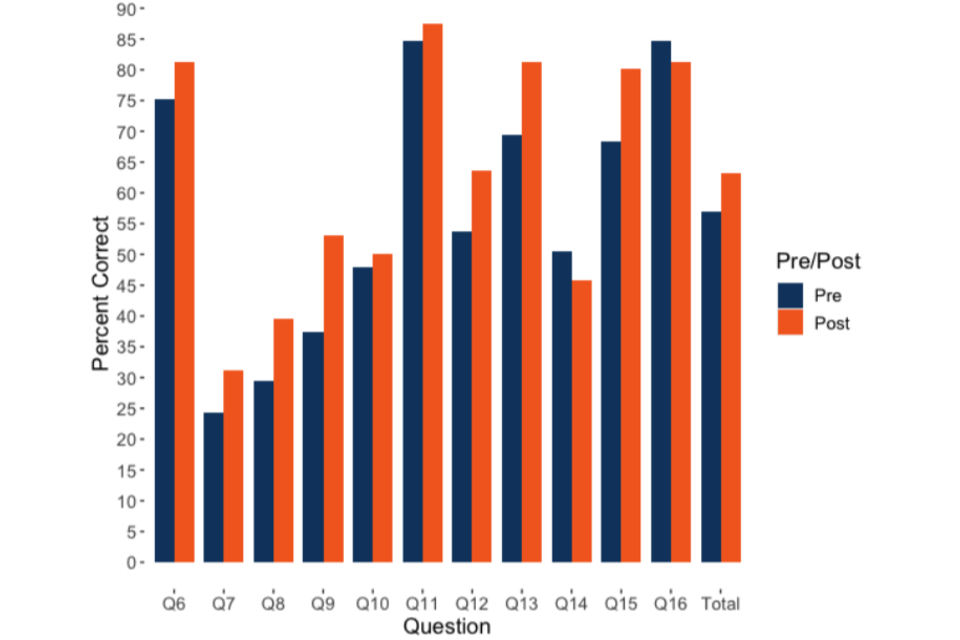

Analysis of performance on individual questions showed that though most questions saw an increase of correct answers, we only found statistically significant results for 3 of the data literacy questions. These were the questions on data understanding, data uses and one numerical reasoning question. There were 2 instances where correct answers had decreased (question 14 and 16, numerical reasoning), though this was not statistically significant. Figure 7 illustrates these results.

As mentioned in our analysis approach section, we are not confident in the practical significance of individual questions due to the elevated risk of false positives. While this does not rule out statistical significance for any given question, it does mean that isolating which questions are driving the overall change is difficult. Individual questions are represented as numbers in Figure 7, these numbers are mapped to the full question text in Table 3 below.

Figure 7: Bar chart showing percentage of correct answers by question number in both pre- and post-time periods

The bar chart displays the change in the percentage of correct answers for individual data literacy questions before and after OBT 2023. Most questions saw an increase in correct responses. Two questions, both on numerical reasoning (Q14 and Q16), had small decreases in correct answers. Questions are represented by numbers in the chart, with full text provided in Table 3 (not shown). While overall data literacy improved, the practical significance of changes for individual questions is uncertain.

Source: One Big Thing 2023 GPG assessment

Notes:

- Sample size: 190 in the pre-assessment, 96 in the post-assessment.

- Figure 7 based on responses to survey questions (see Appendix 6 and 9 for more detail).

Table 3: Question numbers mapped to full question text

| Question Number | Question |

|---|---|

| 6 | Which of the following options can data not do? |

| 7 | Which of the following is not an example of a step to consider when checking the quality of data? |

| 8 | What does a strong positive correlation imply? |

| 9 | Which measure is least affected by outliers? |

| 10 | Which plot would be best to visualise the relationship between study hours and exam score? |

| 11 | Which graph is best for showing how a variable changes over time? |

| 12 | A university researcher…The researcher wants to publish the results to document discrimination. What should they do? |

| 13 | Which of the following best describes the data type of a database table containing customer information like…? |

| 14 | When did the yellow car park become more popular than the blue car park? |

| 15 | Who has spent the most time interviewing? |

| 16 | How much overtime will Anil receive for last week before paying tax? |

Study 2 discussion

RQ1: is there a measurable uplift in data literacy and behaviours for this business unit sample during the period coinciding with OBT?

We found a very small, measurable uplift in data literacy and data behaviours in our GPG sample following participation in OBT.

Data literacy

Overall, this study found a statistically significant difference for the average percentage of correct responses to data literacy questions between the pre- and post-assessments. This suggests that there was an improvement in data literacy within this sample during the period when OBT 2023 was live. However, these changes were of a very small magnitude; less than one correct answer. Increases in scores were observed for most individual data literacy questions, except for the numeracy section (questions 14 to 16) where results declined for 2 questions, although these changes were not statistically significant.

Data behaviours

There is some limited evidence that there may have been a very small increase in participants’ interactions with data and discussions about data during the period coinciding with OBT 2023. Results here are not conclusive as, while statistically significant results were found in our sample, the changes found were very small and therefore of limited practical significance.

Results suggest that there was a small increase in reported use of data in making or suggesting decisions, policy or strategy, and the reported routine inclusion of data, facts or numbers in writing or policy recommendations during the period in which OBT 2023 was live.

The small changes we found in data literacy and behaviours cannot be directly attributed to OBT 2023. They may reflect a pre-existing trend, or be a consequence of other factors. There is a risk of a measurement error because we were not able to fully validate our assessment, and there is likely to be an unobserved variable at play, such as motivation, which may have influenced people’s likelihood of filling out the post-assessment, and their assessment score.

Limitations

This study had a number of methodological limitations which are important when interpreting the results.

This evaluation cannot tell us whether OBT 2023 contributed to any upward trend in data awareness, confidence, knowledge and behaviours. It only tells us whether a statistically significant difference is there, not what caused it. It also does not tell us whether that trend is the same or different to any trend before or after the period we collected data about. Additionally, as we have mentioned before, a statistically significant difference only means that the difference was non-random and tells us very little about what the practical implications of this difference is.

The results of this study cannot tell us anything about whether OBT met its aims in the wider Civil Service. This study was conducted in one business unit (GPG). GPG is not representative of the wider Civil Service. The results only tell us something about whether OBT met its aims within GPG. This is demonstrated in Tables 4 and 5, below, where we can see that, on both gender and grade characteristics, the sample we obtained is different from the wider Civil Service.

Table 4: Overview of participants by gender and comparison to the wider Civil Service

| Gender | % of assessment respondents | % of wider Civil Service | Percentage point difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 62.2 | 54.6 | 7.7 |

| Male | 37.8 | 45.4 | -7.7 |

Source: One Big Thing 2023 GPG assessment/Civil Service Annual Statistical Bulletin: 2023

Notes: based on a combined sample size of 286 from our assessment.

Table 5: Overview of participants by grade and comparison to the wider Civil Service

| Grade | % of assessment respondents | % of wider Civil Service | Percentage point difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| AA-EO | 16.4 | 50.8 | -34.3 |

| HEO-SEO | 37.8 | 28.4 | 9.4 |

| G7-G6 | 40.9 | 14.5 | 26.4 |

| SCS | 4.9 | 1.4 | 3.5 |

Source: One Big Thing 2023 GPG assessment/Civil Service Annual Statistical Bulletin: 2023

Notes: based on a combined sample size of 286 from our assessment.

This study had a relatively small sample size. This means that the evaluation is susceptible to false negatives, where we do not detect a change when there actually is one.

There is a risk of selection and non-response bias in the results, as the assessment was self-selective. OBT completion rates were analysed for the 2 assessment groups at the same time point following the post-assessment. These are outlined below in Table 6.

Table 6: Overview of engagement rates by respondent type

| Respondent type | Percentage starting core OBT training, % | Percentage completing core OBT training, % |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-assessment respondents | 64.7 | 47.9 |

| Post-assessment respondents | 66.7 | 56.3 |

| Overall GPG mailing list | 41.7 | 29.0 |

Source: CSL data using the GPG mailing list to identify participants.

Notes:

- Sample size: 190 in the pre-assessment, 96 in the post-assessment. Overall GPG mailing list totalled 914.

As you can see, there are large differences in participation rates between those who took surveys and those who did not. When we exclude those who started but did not finish the training we can identify an imbalance between participation rates of those who took the pre-assessment and those who took the post-assessment. This suggests that those who responded to our assessment were different from the wider GPG, and those who responded to the post-assessment may, as a group, be different for certain unobservable characteristics. Our concern is that those who responded to the post-assessment may have been, on average, more motivated or interested in data than those who responded to the pre-assessment, hence the differing participation rates.

While we cannot be certain that this issue with unobservable differences is present, the differences in participation rates gives us reason to believe there is a high risk.

Study 3 - Interrupted Time Series Analysis of weekly volumes of data training attendance

Why did we carry out this study?

The objective of this study was to evaluate the third aim of OBT, whether OBT had a meaningful impact on civil servants’ participation in data-related training.

Research question

Our research question was: