Every girl goes to school, stays safe, and learns: five years of global action 2021 to 2026

Published 12 May 2021

Who we are

The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) brings the global reach of UK’s diplomatic network and the power of our development expertise together to promote the UK’s prosperity, security and values internationally. Nowhere is this integrated approach more important that in cementing the UK’s reputation and competitive edge as a global leader in education as the world recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our education agenda spans the full education cycle – from providing aid to keep children safe and learning in times of crisis, to fostering strategic partnerships between the UK’s world-leading universities and institutions overseas; from researching ‘what works’ to preparing pre-schoolers to learn, to our fellowships and scholarships that help develop future leaders.

At the heart of our education agenda – and central to UK action as a force for good in the world – is our pledge to stand up for the right of every girl around the world to 12 years of quality education.

Foreword

Minister Wendy Morton

Global education is in crisis. COVID-19 has been the largest disruptor of education in modern history. At the height of school closures, 1.6 billion children and young people were out of education.

Missing out on school does long-term damage, not only to an individual’s prospects, but to the prospects of their nation. We know how disproportionately it affects girls, and that millions, particularly adolescent girls, may never return to school after the pandemic.

But even before the pandemic, half the world’s children weren’t on track to read before they left primary school. Without remedial support, a further 72 million children may fall behind. Unless the world acts quickly, we risk a lost generation, with decades of progress wiped out.

Education is a human right. It’s also a gateway to other rights. We need it for gender equality, lasting poverty reduction, and building prosperous, resilient economies and peaceful, stable societies. Crucially, it gives children the ability to shape their own lives and realise their potential.

Girls’ education is a particularly powerful investment, the benefits are wide-ranging enough to stop poverty in its tracks. It isn’t just a matter of individual fairness; it’s about the strength and resilience of communities and nations. It is a top priority for the UK.

We are putting girls’ education at the heart of our G7 Presidency this year, securing the endorsement of two new milestones to get the sustainable development goals on track: 40 million more girls in school, and 20 million more reading by age 10, by 2026, in low and lower middle income countries.

With this action plan, we call on the international community to renew and recharge their support for girls’ education over the next five years. The plan sets out the UK’s distinct contribution, using all the resources available to us: diplomatic, financial, and the expertise to drive this agenda forward.

Ambitious targets need ambitious partners. Together, we can advocate for and support global education, particularly for girls, to change lives, communities, and the prospects of nations.

Minister Wendy Morton

Executive summary

A young Rohingya refugee girl in a UNICEF temporary learning centre supported by UK aid, in Kutapalong, Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Credit: Russell Watkins/FCDO

The COVID-19 pandemic threatens to undo many of the global gains of the last two decades in girls’ education. As governments around the world build back from the crisis and allocate funds to the highest return activities, the evidence in favour of girls’ education and empowerment cannot be ignored, including as an asset in tackling climate change.

Yet the crisis in girls’ opportunities for education and learning is not new. Two-thirds of the world’s illiterate people are female. Even before COVID-19 struck, a staggering 50% of all school-age children globally were not learning to read by the end of primary school, with girls the clear majority of out-of-school children. Of those girls out of school, more than half (67 million) live in situations of conflict or protracted crisis. Sadly today, it is millions of poor teenaged girls in Africa and Asia who will pay the highest price of the global education upheaval wrought by COVID-19 - dropping out of school precisely when their prospects in education were at their brightest.

The UK’s response to this set-back – highlighted in the Government’s Integrated Review[footnote 1] and set out in detail in this action plan – will be emphatic. The creation of FCDO is the springboard for a fully integrated approach to our international action on girls’ education. We will bring together our diplomatic clout in defending human rights and the expertise of our ODA programming for even greater UK impact as a force for good in the world. We will remain one of the largest bilateral and multilateral donors to global education, returning to spending 0.7% of GNI on ODA when the fiscal situation allows.

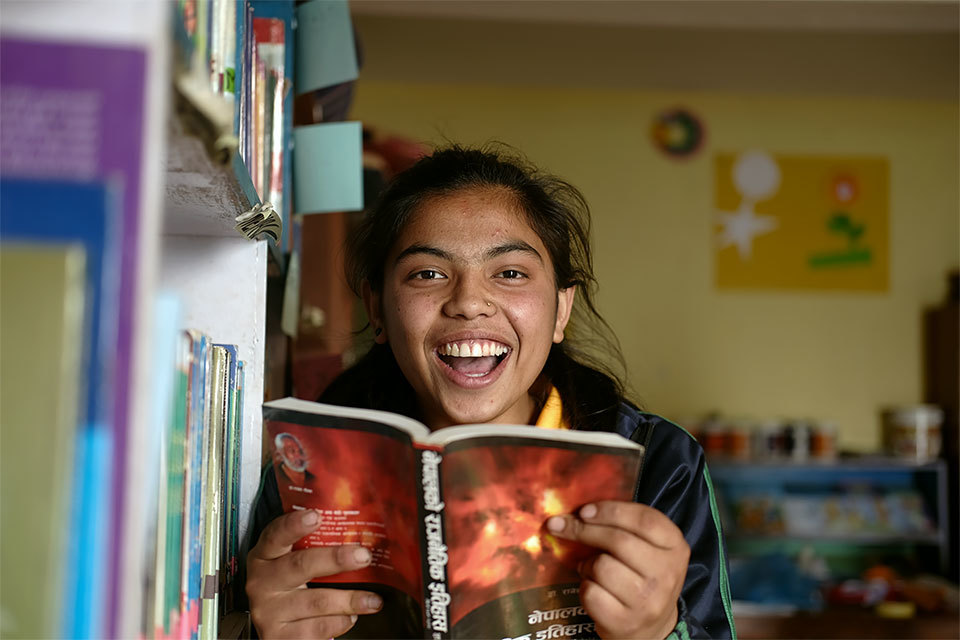

Siddika, a ‘little sister’ supported by the Sisters for Sisters project in Nepal. Credit: VSO Nepal/Girls’ Education Challenge

2021 is a year of UK leadership on the world stage. We will use our G7 Presidency and our hosting, with Kenya, of the Global Education Summit in July to bring urgency to the global education recovery, so no girl is left behind. We shall re-double efforts as a champion of girls’ education and gender equality, working on three fronts to:

-

shape a renewed international effort to get the 2030 Education Sustainable Development Goal on track, obtaining support for two milestone targets on girls’ school access and learning, tracking progress relentlessly; and continuing to press for more and better targeted international education finance

-

mobilise our network of British Ambassadors and High Commissioners to support committed national governments to scale up efforts to get girls into school and learning, broadening and deepening the impact of our Girls’ Education Campaign, and convening partner governments who have made progress to share their experience

-

pioneer global public goods for education - developing and using evidence about what works to support governments to make bold reforms, ensuring we deliver better for marginalised girls

Our work on girls’ education is a core pillar of our wider UK support to international education, spanning early years, primary and secondary education, to higher education and skills. We will leverage the UK’s comparative advantage as a world leader on education – bringing together our diplomacy, trade, development and soft power, to support partner governments, build stability and prosperity, and to develop future women leaders.

Girl’s education is a game changer

School girls supported by the ENGINE project in Nigeria. Credit: Mercycorps/Girls’ Education Challenge

Education is a human right gateway to other rights. It is essential for gender equality, lasting poverty reduction, and building prosperous, resilient economies and peaceful, stable societies. [footnote 2]

There is overwhelming evidence that investing in girls’ education and breaking down other barriers that they face, can put nations in the development fast lane, especially when women are helped into the workforce. The recent growth and success of countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America has been powered by expanding quality basic education for all children, while at the same time paying special attention to girls and other disadvantaged groups. Nations have succeeded by making girls’ education a national priority rather than an educational priority.

Girls’ education is a smart investment because the benefits are wide-ranging enough to stop poverty in its tracks between generations. Quality girls’ education, where girls are in the classroom and learning, leads to smaller, healthier and better educated families. [footnote 3] With just one additional year of secondary school, a woman’s earnings can increase by a fifth. Educated and empowered women can play a massive role in shaping their countries’ future. As governments build back from the COVID crisis and allocate funds to the highest return activities,[footnote 4] girls’ education and gender equality are priorities no country can afford to ignore. [footnote 5]

More and more, the benefits and costs of girls’ education are felt across borders and have truly global implications. For example, literate girls and women are among the greatest assets we have in responding to the climate crisis. Many women and girls are already leading work to address climate change. Through quality education more girls need to be empowered and equipped as agents of change.

Not only is educating and empowering girls a smart investment for all countries, it is also in the UK’s national interest. Higher standards of girls’ education globally can help protect the UK from the consequences of conflict. Studies show that countries with high levels of gender-based discrimination are more likely to experience conflict, whereas those where women and men have more fair and equal access to opportunities tend to be stable and peaceful.[footnote 6]

None of this means we value boys’ education less highly; indeed, the majority of FCDO’s education work benefits boys as well as girls. We recognise that only by involving boys and men can we address harmful gender stereotypes and improve the restrictive situation and discrimination holding girls and women back. For instance, teaching that challenges discriminatory values and beliefs and expands children’s horizons is as important for boys as for girls. But we will measure our success by the progress made by the girl in the most challenging of circumstances; only if she is thriving in education, will we know we’ve done a good job.

The scale of the challenge

Fatima is 12 years old. She left Syria in 2012. She dreams of being a doctor. Credit: Adam Patterson/Panos/FCDO

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to the largest disruption of education ever.

– Antonio Guterres, United Nations’ Secretary General, September 2020

The COVID-19 crisis has dimmed the hopes of a generation of children and young people. At the peak of school closures in April 2020, 1.6 billion learners were out of school across 180 countries. Globally, children have missed 2/3rds of a school year, and schools in some countries are still closed. [footnote 7] Children and parents have experienced upheaval: more children are going hungry, [footnote 8] are experiencing depression and anxiety, [footnote 9] and are suffering from violence and abuse. [footnote 10] One estimate suggests that five months of learning losses could result in this generation foregoing earnings equivalent to one-tenth of global GDP. [footnote 11] We must act now to mitigate the lasting impacts to individual girls’ and boys’ lives, communities and economies at large.

Girls with disabilities [footnote 12] and those living in areas affected by conflict [footnote 13] are likely to be worst affected by school closures. But the damage is widespread. As many as 24 million disadvantaged children (11 million girls) may not return to school at all [footnote 14], with secondary age girls most at risk of staying home or marrying early because their families have fallen into poverty.2.5 million additional child marriages are expected in the next five years and over 1 million adolescent pregnancies in the next 12 months. [footnote 15] Rates of gender violence affecting girls are thought to have doubled compared to when schools were open [footnote 16] (i.e. from 8% to 17%).

Adhiambo and her teacher Risper who specialises in the educational needs of disabled children, Kenya. Credit: Anna Dubuis/FCDO

Today, hard-won gains of the last 25 years [footnote 17] are being rolled back. The threat to girls’ futures could not be clearer.

Even before COVID-19, 258 million children across the world were out of school, with girls in Africa and South Asia and in conflict zones lagging furthest behind, especially in their chance of getting a secondary education. [footnote 18] Of the estimated 65 million primary and secondary school age children with disabilities, at least half are out of school. [footnote 19]

But even for those enrolled, for far too many, schooling isn’t producing learning: half the world’s children, 387 million, were already not on track to learn to read by the end of primary school. This global crisis in learning has hit low income countries hardest - with 9 out of 10 children unable to read a story by age 10. [footnote 20] COVID-19 school disruptions may have caused learning losses equal to the gains of the last two decades. [footnote 21] Without remedial action, an additional 72 million children will fail to learn basic literacy and numeracy skills. [footnote 22]

Increasingly climate change threatens global progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals for Education (SDG4), Gender Equality (SDG5) and related global education commitments. Globally, at least 200 million adolescent girls live on the frontlines of the climate crisis and those who are already marginalised through poverty, displacement or disability, are likely to be worst affected. Climate change impacts are disproportionately felt in developing countries and girls are doubly disadvantaged because of social expectations about their roles.

What we’ve learnt

Girls supported by the STAGES project walking to class in the Bamyan Province of Afghanistan. Credit: STAGES/Girls’ Education Challenge

Gender gaps persist in education at girls’ expense due to the sheer number of hurdles that stand in a girl’s way. Traditional attitudes restrict women’s roles and underestimate girls’ learning potential. Physical disincentives, such as long distances, to the nearest school and lack of safe transport. Cost constraints, like buying school uniforms, paying exams fees and access to even basic technology needed for distance learning. These challenges differ for different groups of girls. But around the world girls who are poor, disabled or live on the margins contend with the most.

Problems come up for girls at different ages and stages of her education. A girl’s place within the family and community begins to shift during adolescence when harmful norms may begin to shape her life, choices and freedoms. Making the move from primary to secondary school is often hugely challenging for adolescent girls: there are greater responsibilities to care for relatives or siblings, expectations to earn money, have sexual relationships without contraception or get married.

Adolescence is when gender gaps in access to and attainment in school really widen. Yet it is precisely at this time that girls stand to benefit most from an education which widens their options and opportunities in life. One additional school year can increase a woman’s earnings by 20%. At this time, teenage girls’ greatest risk of death is from complications during pregnancy and childbirth. [footnote 23]

Ensuring all girls gain foundational skills and truly benefit from education requires all the tools in our toolkit, not only in the education sector but beyond. In rolling out our 2018 Education Policy [footnote 24] we have learnt that to make a difference, three strategies must be employed together:

Strategy 1

We need to transform what happens in the classroom to improve girls’ outcomes – ensuring Government policy and programmes are more inclusive, can tackle multiple sources of disadvantage simultaneously and are more flexible to children’s diverse needs.

In Ethiopia, the UK supports the Government to improve the quality of education for over 1 million children (over 50% girls), with particular interventions in up to 18,000 schools, including the most marginalised regions of the country. The programme is focused on reducing dropout, particularly girls, pastoralist children and children with disabilities, by improving the quality of early years education and raising the skills and competencies of 125,000 teachers and headteachers.

In Zimbabwe, the UK’s support for the amended Education Act is ensuring all girls have a right to education, including in sexual reproductive health education. We are working with the Government and communities to ensure girls can remain safely in school and learn; reducing early marriage, early pregnancy, and violence in school and on route to school, including through provision of bicycles and safe boarding whilst at school.

In Sierra Leone, the UK is improving the quality of secondary education for all children, alongside specific measures to reduce barriers for girls, including addressing violence in schools. The Government has recently launched the ‘Radical Inclusion Policy’, which the UK has supported, to ensure girls have the right to return to school after pregnancy. So far, classroom learning has improved for 1.1 million children, leading to 30,000 additional pass rates in English and maths exams. Double the number of girls now stay in school compared to 2018, and past underperformance of girls compared to boys in final exams has been eliminated.

Strategy 2

We need to tackle the barriers that the most marginalised girls face, particularly during adolescence – whilst we work with Government to ensure more inclusive education systems, a more comprehensive package of support is needed to ensure girls learn now. We need to enable girls to thrive in mainstream education, as well as supporting alternative or non-formal education for those outside of the mainstream.

In Pakistan, alongside support to Government education reforms in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the UK has provided targeted support for over 400,000 highly marginalised adolescent girls. This has included provision of second chance education, scholarships for girls from poor households to attend secondary education, alongside setting up community run schools to reduce the distance that girls must travel to school.

In South Sudan, the UK is working with Canada to remove the financial barriers to education for up to 400,000 marginalised girls, alongside information campaigns with parents on the benefits, costs and quality of education to change behaviours, and encouraging increased enrolment and attendance in school.

In Afghanistan, our girls’ education challenge programme co-funded with USAID has addressed parents’ reluctance to send their daughters to school due to the risks of long, dangerous journeys to school through minefields and concerns around male teachers. Our support across 16 provinces has reached over 210,000 girls and 110,000 boys. Over 7,500 teachers have received training and 1,995 young women supported to attend teacher-training college or take apprenticeships, becoming future role models for their communities. [footnote 25]

Strategy 3

We need to invest in good teaching – having competent, creative and well-supported teachers is one of the most impactful and cost-effective ways to get girls’ learning. As countries recover from COVID19, we need to take a fresh look at how to train, recruit and motivate teachers, and support teaching strategies and policies proven to work well for all poor and marginalised children, but particularly for girls.

In Ghana, the UK has supported the Government’s Teacher Education Policy reforms, making teaching a degree profession for the first time and putting in place new National Teaching Standards. This ‘at scale’ reform has improved teaching practices of 70,000 student teachers and 1500 teacher educators so far. It has also led to more inclusive and gender-responsive teaching practices in public teacher training colleges and schools, all 46 teacher training colleges putting in place anti-sexual harassment policies. The UK has also supported gender-responsive remedial teaching using distance learning technology, and helped all schools implement school re-entry guidelines for girls after childbirth.

In northern Nigeria, the UK has been working in partnership with the Government, TARL Africa and UNICEF to ensure schools are ‘teaching at the right level’. [footnote 26] This proven cost-effective remedial strategy ensures dedicated time for basic skills alongside regular assessment of students’ progress and is now being scaled up across some States in northern Nigeria.

In Malawi, the UK is supporting the government’s national reform of the primary school maths curriculum; developing new teaching and learning materials; training all teachers nationwide; and establishing ongoing school-based support. It builds on previous UK and US investments to improve early grade literacy and includes gender sensitive pedagogy (so girls succeed just as well as boys) and supports children with learning difficulties and special educational needs.

The global progress we need to see

Girls supported by the Discovery Project in class with their teacher in Ghana. Credit: Discovery Learning Alliance/FCDO Girls’ Education Challenge

Progress towards the Education Sustainable Goal is at a crossroads. The COVID pandemic has set back gains further and faster than anyone could have predicted. At the same time, the education sector has an opportunity to ‘open up better’, harnessing the impetus of the crisis to take on new challenges and reassess old ones. This opportunity must be seized.

With less than 10 years until the SDG4 target date of 2030, national governments and the global community must work together as never before to accelerate progress. Governments are looking for evidence of what works to support bold reform that will get children learning - and ensure all investments, whether home-grown or externally funded, deliver value for money. The UK has pledged to stand up for the right of every girl to 12 years of quality education; as a champion of girls’ education, and a global leader on gender equality, we intend to drive the pace of the global education recovery so that all girls benefit. Our aims are straightforward:

-

increase the number of girls around the world who go to primary and secondary school, reducing the numbers of out-of-school girls

-

improve the quality of education, so all girls can achieve their potential and break the cycle of poverty passing between generations

But broad aims are not enough. Experience has shown that time-bound targets help to galvanise international action. As set out in the UK’s new Strategic Framework for ODA, our focus is to achieve two targets over the next five years, serving as way-markers on the road to achieving SDG4. The UK will raise a political rallying call to deliver these targets and get SDG4 on track, working with partners at all levels - governments, NGOs, the research community and international actors. Making progress with these targets represents an enormous challenge, demanding new levels of political commitment and action at both national and global levels.

Global targets 2021 to 2026

Access to school: 40 million girls in primary and secondary school in low and lower middle-income countries by 2026.

Quality Education: 20 million girls able to read in low and lower middle-income countries by age 10 by 2026.

These targets are complementary and mutually reinforcing, each approaching the challenges for girls from different angles. While the first focuses on access to school - closing the enrolment gap for highly marginalised girls, and at secondary level in particular – the second looks at what skills are required for girls to start well and progress in education.

UK actions

Beatrice is educating her classmates about family planning and avoiding teenage pregnancy in Tanzania. Credit: Sheena Ariyapala/FCDO

Pillar 1: A global coalition on girls learning

The UK has made a strong contribution to girls’ education over the years by bringing global players together and sharing our understanding of what works. We have helped shift international attention towards foundational skills as the critical gateway to future learning. But the scale of the challenge ahead defies any single country; it requires an unprecedented effort across the whole international community.

2021 is a year of action for the UK on girls’ education. We will use our Presidency of the G7, our co-hosting of the Global Education Summit – Financing GPE and the UN Climate Change Conference to shine a spotlight on girls’ education, making the most of each opportunity to refresh and revive international commitment and highlight where resources are needed most. FCDO Ministers, assisted by the Prime Minister’s Special Envoy for Girls’ Education will spearhead this effort: our goal is to agree a new global coalition to drive progress for girls’ education.

At the global level we have three priorities:

Priority 1: Increasing political commitment and international leadership on girls’ education

We will:

- put the crisis in children’s foundational skills at the centre of major international events in 2021, securing bold new commitments, deepening our bilateral partnerships with like-minded partners, and encouraging other countries to prioritise girls’ education

- work closely with others to reset and recharge the global SDG4 Steering Committee, anchoring this in the Office of the UN Secretary General and involving political representation

- shine a spotlight on the clear and present danger that climate crisis poses for education, and better define the role of girls’ education in the global response

- galvanise international action to overcome the barriers to girls’ access to education, including through the Generation Equality Forum and G7 commitments to transformative actions, the UN Action Coalition on Gender Based Violence and UK involvement in Family Planning 2030

Priority 2: Ensure international education finance is better targeted and donor education ODA goes further

We will:

-

refocus international education finance, particularly bilateral financing, towards the poorest countries and basic education, alongside innovative financing that leverages scarce ODA and makes it go further, drawing in the private sector, foundations and non-traditional donors to generate new sources of finance for girls’ education

-

host a successful Global Partnership for Education replenishment to raise $5 billion over the next 5 years to deliver GPE’s ambitious new strategy, supporting countries to build back better from COVID-19 and accelerating results for the most marginalised girls

-

get new partners on board to support ‘Education Cannot Wait’ (ECW) as the key global platform to deliver direct support for children whose education has been affected by emergencies and protracted crises, and rally international support for the Safe Schools Declaration

-

as leading supporters of the Multilateral Development Banks, ensure they deepen their focus on improving learning, including strong financial support for secondary education opportunities for girls in IDA, cost-effective and evidence based investments in education technology, and ensuring C19 economic recovery support is gender sensitive, inclusive and targets the most marginalised

Priority 3: Press for better accountability and coordination in the international education system to deliver the greatest impact for girls’ education

We will:

-

use our diplomatic influence to help clarify organisational mandates, roles and responsibilities within the international system with respect to education and tackling gender related barriers

-

strengthen the capacity of UNESCO’s Institute of Statistics and the Global Education Monitoring Report to track and report on global education progress, including for the new global targets for girls’ education, ensuring a particular focus on disaggregated data – including extreme poverty, gender, disability, location and other criteria relevant to each country

-

work with like-minded partners to deliver stronger accountability for SDG4 progress, including through better use of education data to focus global efforts on areas of greatest need

Pillar 2: Country-led action to get more girls in school, kept safe and learning

Between 2015 to 2019, the UK helped 15.6 million children gain a good education, over 8 million of them girls, through our work directly with national governments. Alongside our support to improve learning in schools, we have led important initiatives to tackle the obstacles that stop girls going to and remaining in school - from providing safe spaces for education in armed conflicts to improving girls’ access to sexual and reproductive health services.

There is more we can and must do. In the next five years, we will focus on delivering a set of measurable results which will be the UK’s distinct contribution towards the global targets for girls’ education. This will include ambitious UK specific targets to ensure:

- more girls in primary and secondary school in UK aid-backed countries, reducing the number of out of school girls

- more girls reading by age 10 in UK aid-backed countries, and

- girls supported to catch up on learning loss due to COVID19 disruptions to schooling

We will work closely with UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics (UIS) as the official source of comparable international data for Sustainable Development Goal 4 to set baselines and targets, accounting for the devastating impact of COVID19 on schools, and establishing a robust monitoring system to account for progress.

To meet our UK targets, we will prioritise a broad set of UK led action: including developing new partnerships and programmes at national and regional levels, mobilising our FCDO Ambassadors and High Commissioners and our network of skilled education advisers. We will initiate a bold campaign and communications plan to build greater public awareness of and enthusiasm around the importance of educating girls, especially in the recovery post COVID19 pandemic, and encouraging the use of evidence-based technology and innovative solutions to tackle emerging challenges.

We will listen to and engage with communities, families, and girls to understand their needs and constraints, and tailor our work to children experiencing different levels and types of marginalisation. Grassroots and national women’s rights organisations have a critical role in ensuring girls’ and women’s voices inform policy and hold policy makers to account, and in challenging norms and attitudes that discriminate against girls. In line with the SMART buys for education [footnote 27]; we will ensure our own initiatives are cost-effective to achieve girls’ learning outcomes, promote long term stability and resilience, and have the potential to be scaled.

Our work with national partners has three priorities:

Priority 1: Education partnerships

– supporting national leaders in UK aid-backed countries to address the gap in children’s foundational skills, with a focus on reaching every girl and ensuring they learn, and making the best use of all UK education financing at the country level, including through the ‘Global Partnership for Education’.

We will:

- adjust our bilateral country programmes to have maximum impact on reducing out-of-school girls, improving learning and COVID19 recovery where it matters most; deepening and expanding our support for education across Africa (particularly east Africa) and the Indo-Pacific region of Asia

- support national partners to better measure progress for girls’ education, including making the most of available technology, leading to more robust, disaggregated and comparable measures of children’s learning, teaching quality, education system performance and out of schoolgirls

- continue flagship programmes to reduce violence against women and girls, violence against children and child marriage, and to tackle financial barriers to girl’s education. To promote gender equality, we will work with women’s rights organisations to tackle the discrimination, violence and inequality that hold women back

Priority 2: Focused support for the most marginalised girls

– who are out of school and not learning – drawing on the latest evidence and innovation to extend the reach and impact of all UK funded programmes.

We will:

-

rollout new regional initiatives for Africa and Asia focused on overcoming the barriers that marginalised girls face during adolescence - where girls are out of school, we will provide effective ‘catch up’ programmes to get girls on track with their learning, alongside addressing gender-based violence and harmful norms

-

work with national governments, to implement at-scale inclusive education work, supporting children with disabilities to access school and learn

-

ensure the global fund and platform ‘Education Cannot Wait’ continues to be highly effective in reaching children whose education has been disrupted by conflict, disease outbreaks and extreme weather events and is well coordinated with other bilateral and multilateral investments

Priority 3: Backing national champions for girls’ education

– supporting the FCDO network of British Ambassadors and High Commissioners across the globe to drive a high ambition and evidence-based response to the global targets for girls’ education with national leaders.

We will:

-

lead inspirational and energising campaigns alongside UK political leadership and diplomacy to bolster national leaders determined to make new commitments and drive significant progress for girls’ education, ensuring a strong focus on more effective public and private spending in education, and sharing evidence from other countries that have taken similar positive steps

-

through our UK Special Envoy, engage youth activists and encourage their leadership as a powerful catalyst for change – and champion the use of evidence for what works to get girls into school and learning

-

catalyse links with other UK global campaigns on gender equality, including UN Action Coalition on Gender Based Violence, and FP2030

Pillar 3: Global goods to support bold education reform

The UK is a world leader in producing global public goods. Our portfolio of pioneering education research has grown in recent years, supported by the UK’s leading experts in our Science Advisory Group, Universities and Research Councils. The number of robust studies on what works has surged driving up standards in the sector and providing governments with the data they need to make bold reform, as well as tough financial choices.

Evidence is at the heart of our approach to girls’ education - meeting the demands from governments whose education systems are under significant strain. In partnership with the World Bank, UN, USAID and our Building Evidence in Education partners we will fill evidence gaps. We will work to strengthen capability at a country level to test, adapt and scale interventions, with a focus on girls and the most marginalised. We will use the UK’s diplomatic and development expertise to expand our global reach in tackling the political and technical barriers that constrain access to education and learning outcomes.

Our work on global goods and data has three priorities:

1. Greater investment and availability of global public goods

– leading to a shared understanding of what works to get marginalised children, particularly girls, into school and learning.

We will:

-

establish the ‘What Works Hub for Global Education’, the first ever global evidence platform for education focused on enabling African and Asian education policy makers and planners to make better use of evidence to drive more effective spend, resulting in better outcomes for girls, leveraging the best of UK and international research with the World Bank, UN and Gates Foundation

-

build a new UK-led community of practice in implementation science to tackle the difficulties governments face in taking education innovations to scale and support replication studies to trial promising interventions in new contexts, filling critical gaps in the evidence base

-

ensure FCDO flagship research on education systems, longitudinal study and with ESRC, on education technology, early childhood, children affected by conflict and crises, gender and adolescence, violence against women, girls and children - producing world class global goods which enable Governments to raise learning levels for all children, with a focus on girls and the most marginalised

2. UK champions evidence dissemination at global and national levels

We will:

-

support Ambassadors Events to convene Ministers of Finance and Education to analyse the evidence including smart buys. Support the Education World Forum and our FCDO regional research hubs to increase evidence uptake and use

-

work with UK’s Special Envoy to lever further collaboration and investment in evidence through the Building Education in Evidence group (BE2) with a particular focus on strengthening knowledge systems and cost effectiveness to build back better post C-19

-

cement the UK’s reputation as a global leader by hosting the Global Education Evidence and Advisory Panel (GEEAP) and production of world-class reports, building on the recent SMART Buys for education [footnote 28]

3. Education policy makers use evidence to support efficient use of resources

– to tackle the global learning crisis and re-energise education leaders, managers and teachers who remain at the heart of the solution.

We will:

-

support diagnostics with partner governments, the Global Partnership for Education, the World Bank and UN to design and implement effective policies that get children learning and respond to the specific needs of marginalised children

-

ensure FCDO research partners act as ‘super communicators’ in the triangle of influence between Governments, donors and academic experts, supporting countries track key performance indicators to enhance effectiveness and accountability at national level

-

use new technology and our EdTech Hub to scale-up innovation providing real-time solutions to Governments

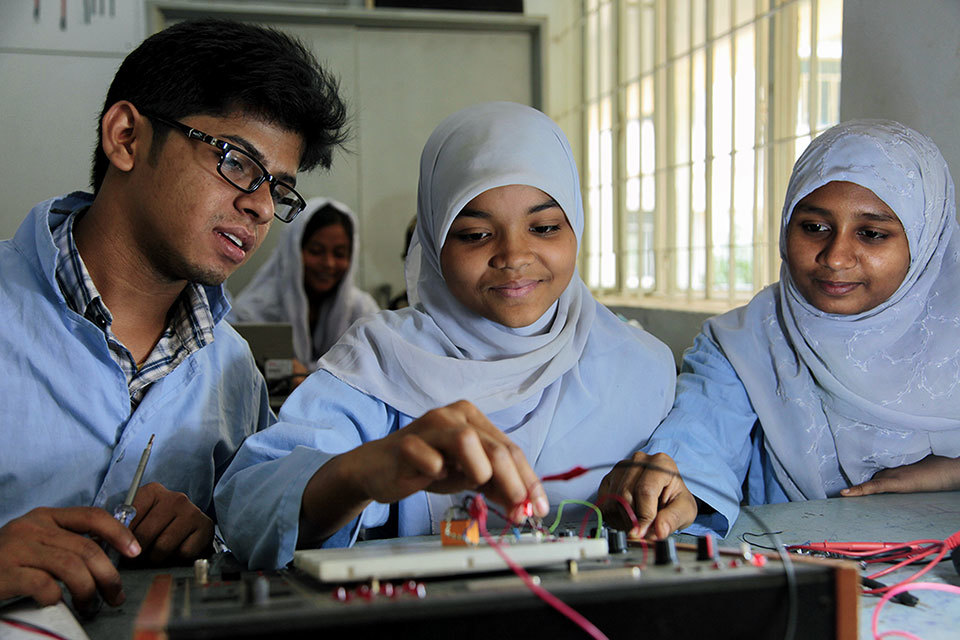

In Bangladesh, Rahima and Mukta have a hands on approach to learning technical skills. Credit: Ricci Coughlan/FCDO

-

HMG (2021) The Integrated Review. Available from https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/the-integrated-review-2021#integrated-review (accessed 30/04/21) ↩

-

World Bank (2018) Learning to Realize Education’s Promise, World Development Report – available from World Development Report 2018: Learning to Realize Education’s Promise (worldbank.org) (Accessed 30/04/2021) ↩

-

Kaffenberger, M., Pritchett, L., & Sandefur, J. (2018). Estimating the impact of women’s education on fertility, child mortality, and empowerment when schooling ain’t learning’. RISE (Research on Improving Systems of Education) Working Paper. Available from https://riseprogramme.org/sites/default/files/publications/Spivack_Girls_Education.pdf (Accessed 30/04/21) ↩

-

Education Commission (2015) The Learning Generation Available from https://report.educationcommission.org/report/ (Accessed 30/04/21) ↩

-

]Brookings Institution (2015) What Works for Girls’ Education: Evidence for the World’s Best Investment Available from https://www.brookings.edu/book/what-works-in-girls-education-evidence-for-the-worlds-best-investment/ (Accessed 30/04/21) ↩

-

In these countries, girls’ education has gone had in hand with shifts in discrimination, such as reductions in gender-based violence, and ‘enablers’ like access to sexual and reproductive health and rights and paid childcare has ensured women play their full part in peaceful and prosperous societies. ↩

-

UNESCO (2020) Data accessed via: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse ↩

-

Borkowski, Artur; Ortiz Correa, Javier Santiago; Bundy, Donald A. P.; Burbano, Carmen; Hayashi, Chika; Lloyd-Evans, Edward; Neitzel, Jutta; Reuge, Nicolas (2021). COVID-19: Missing More Than a Classroom. The impact of school closures on children’s nutrition, Innocenti Working Papers no. 2021-01, UNICEF Office of Research - Innocenti, Florence. Available from https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/COVID-19_Missing_More_Than_a_Classroom_The_impact_of_school_closures_on_childrens_nutrition.pdf (Accessed 30/04/21) See also, Standing Together for Nutrition coalition (2020) The potential impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on maternal and child undernutrition in low and middle income countries. The Lancet. Available from https://www.thelancet.com/article/S0140-6736%2820%2931647-0/fulltext (Accessed 30/04/21) ↩

-

Young Lives (2020) Listening to Young Lives at Work in Peru: Second Call; Listening to Young Lives at Work in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana: Second Call. Available from https://www.younglives.org.uk/content/young-lives-work-ylaw?tab=4 (Accessed 30/04/21) ↩

-

Plan International (2020) Because we matter: Addressing COVID-19 and Violence Against Girls in Asia-Pacific. Available from: https://plan-international.org/publications/because-we-matter (Accessed 30/04/21)r ↩

-

World Bank (2020) Simulating the Potential Impacts of the COVID-19 School Closures on Schooling and Learning Outcomes: A set of Global Estimates. Available from Simulating the Potential Impacts of the COVID-19 School Closures on Schooling and Learning Outcomes: A set of Global Estimates (worldbank.org) (Accessed 30/04/21); 0/ This estimate assumes school closures for 5 months will result in 0.6 years of learning lost, which roughly equates to $16,000 of wages lost for each student over the course of their lifetime. Learning losses could translate over time into $10 trillion of lost earnings for the economy in the intermediate scenario. ↩

-

World Bank (2021) Pivoting to Inclusion: Leveraging Lessons from the COVID-19 Crisis for Learners with Disabilities. Available via: http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/147471595907235497/IEI-Issues-Paper-Disability-Inclusive-Education-FINAL-ACCESSIBLE.pdf (Accessed 30/04/21) ↩

-

Save the Children (2021) Progress under threat: Refugee education one year on from the Global Refugee Forum and the impact of COVID-19. Available via: https://inee.org/system/files/resources/Progress%20Under%20Threat.pdf (Accessed 30/04/21) ↩

-

UNESCO (2021) Pandemic-related disruptions to schooling and impacts on learning proficiency indicators: A focus on the early grades. Available from http://gaml.uis.unesco.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/03/UIS_COVID-19-interruptions-to-learning_EN.pdf (Accessed 30/04/21) ↩

-

Lancet (2020) 2·5 million more child marriages due to COVID-19 pandemic. Available from https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)32112-7/fulltext (Accessed 30/04/21) ↩

-

Flowe, H. D. et al. (2020) ‘Sexual and Other Forms of Violence during the COVID-19 Pandemic Emergency in Kenya’. Available from https://psyarxiv.com/7wghn/ (Accessed 30/04/21) ↩

-

Global Education Monitoring Report (gender edition) 2020. Available from https://www.ungei.org/publication/new-generation-25-years-efforts-gender-equality-education (Accessed 30/04/21) (Accessed 30/01/21) ↩

-

UNESCO Institute for Statistics (2019) New Methodology Shows that 258 Million Children, Adolescents and Youth Are Out of School. Available from http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/new-methodology-shows-258-million-children-adolescents-and-youth-are-out-school.pdf (unesco.org) (Assessed 30/04/21) ↩

-

UNICEF-IRC (2016) Towards Inclusive Education: The impact of disability on school attendance in developing countries. Available from https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/845-towards-inclusive-education-the-impact-of-disability-on-school-attendance-in-developing.html (Accessed 30/04/21) ↩

-

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2017). More Than One-Half of Children and Adolescents Are Not Learning Worldwide. Fact Sheet. Paris: UNESCO. Available from http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/fs46-more-than-half-children-not-learning-en-2017.pdf (Accessed 30/04/21) ↩

-

UNESCO (2021) Disruptions to Schooling and the Need for Recovery. Available from http://uis.unesco.org/en/blog/disruptions-schooling-and-need-recovery (Accessed 30/04/21) ↩

-

WB (dec2020) Learning poverty in the time of COVID-19: a crisis within a crisis. Available from https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/163871606851736436/learning-poverty-in-the-time-of-covid-19-a-crisis-within-a-crisis Accessed (30/04/21) ↩

-

WHO, 2020 Adolescent Pregnancy Fact Sheet. Available from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy (Accessed 30/04/21) ↩

-

DFID (2018) Get Children Learning. Available from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/dfid-education-policy-2018-get-children-learning/dfid-education-policy (Accessed 30/04/21) ↩

-

Banerjee, Abhijit, Rukmini Banerji, James Berry, Esther Duflo, Harini Kannan, Shobhini Mukherji, Marc Shotland, and Michael Walton. 2016. “Mainstreaming an effective intervention: Evidence from randomized evaluations of ‘Teaching at the Right Level’ in India.” NBER Working Paper No. 22746. Available from https://www.nber.org/papers/w22746 (Accessed 30/04/21). ↩

-

Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel. (2020). Cost Effective Approaches to Improve Global Learning What Does Recent Evidence Tell Us Are Smart Buys for Improving Learning in Low-and-Middle-Income Countries. World Bank; FCDO; Building Evidence in Education. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/719211603835247448/pdf/Cost-Effective-Approaches-to-Improve-Global-Learning-What-Does-Recent-Evidence-Tell-Us-Are-Smart-Buys-for-Improving-Learning-in-Low-and-Middle-Income-Countries.pdf ↩

-

Ibid. ↩