Experiences of claiming and receiving Carer’s Allowance

Published 16 May 2024

Qualitative and quantitative research with claimants

Alice Coulter, Emma McKay, Lindsay Abbassian, Lucy Williams

DWP research report no. 1064

A report of research carried out by Kantar on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions.

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published May 2024.

ISBN: 978-1-78659-687-1

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Voluntary statement of compliance with the Code of Practice for Statistics

The Code of Practice for Statistics (the Code) is built around 3 main concepts, or pillars, trustworthiness, quality and value:

- trustworthiness – is about having confidence in the people and organisations that publish statistics

- quality – is about using data and methods that produce assured statistics

- value – is about publishing statistics that support society’s needs for information

The following explains how we have applied the pillars of the Code in a proportionate way.

Trustworthiness

Kantar Public, and independent social research agency, conducted this research on behalf of DWP. Kantar Public are bound by the Market Research Society’s and ESOMAR code of conduct. These codes ensured professional standards are maintained, work is impartial and done in an ethical way.

Quality

Established quantitative research methodology and analysis processes were used to conduct the research. They meet ISO 9001, ISO 20252 and ISO 27001 international quality standards for market research, and Kantar’s internal quality checking processes.

Value

The research will provide a useful insight on the factors that lead to people claiming Carer’s Allowance, how the benefit interacts with employment and the impact of recovery of overpayments on the carer and the person they are caring for.

Executive summary

This research was conducted to investigate the circumstances of carers claiming Carer’s Allowance (CA), a benefit provided to individuals caring for someone else for at least 35 hours a week. It aimed to build on previous research commissioned by DWP and others by exploring how and why claimants claimed CA; their caring roles; experiences of combining paid work and care; and how well claimants understood the rules associated with CA. The research comprised a background research phase, a survey of 1,021 CA claimants and 60 in-depth interviews with CA claimants. The fieldwork was undertaken in 2020 and 2021, and the final report written in 2021. The report context, benefit rates and earnings rules therefore reflect those at the time of writing.

Key findings

- Over half of claimants (54%) lived in lower income households (earning £20,799 per annum or less before deductions). They were most likely to have GCSEs or no formal qualifications as their highest qualification (53%), as well as poor health, with two in five (40%) having a long-term health condition.

- Most claimants cared for close relatives, with two in five caring for a child (39%), a quarter caring for a spouse or partner (25%), and one in five (22%) caring for a parent.

- Caring was a long-term and high intensity commitment. Half of claimants (52%) spent 65 or more hours caring per week and over half of all claimants (54%) had been caring for between 5 and 20 years. It could also be challenging and put strain on claimants, including by contributing to mental ill-health.

- Before starting caring, half of claimants (52%) said they had always or mostly been in paid employment and just under half (45%) said they had been in and out, mostly out, or never in paid employment.

- Only 16% of CA claimants were currently in paid work, while seven in ten (72%) were not in paid employment. Claimants in paid work tended to work part- time in lower paid jobs that they were able to fit around their caring responsibilities, with most (81%) working 20 hours or less a week.

- Of those not currently in paid work, seven in ten (69%) said this was due to their responsibilities as a carer. Other barriers included a lack of flexible working options, claimants’ own health and confidence issues. The CA earnings threshold was one factor in a wider calculation about the value of work for claimants (particularly the number of hours those already employed could work), considered alongside caring responsibilities, potential earnings and the impact on their quality of life and well-being.

- There was a lag between starting caring and claiming CA. While seven in ten claimants (70%) had been caring for 5+ years, only 3 in 10 (34%) had claimed CA for that length of time.

- Claimants reported that receiving CA as a benefit was straightforward and they were content with the level and frequency of contact they had with DWP.

- Very few claimants involved in this research (3%) had received an overpayment of CA. Those that had were not always able to explain how or why and some described a negative experience with DWP, suggesting there is some room for improvement with customer service and clarifying the rules and requirements of CA. The impact of an overpayment varied depending on the claimant’s financial situation and the amount to be repaid but did not seem to adversely impact the cared for person.

- One in ten claimants (9%) did not have access to the internet and a substantial minority said they did not feel confident completing online forms (36%). This suggests that paper and telephone options remain valuable and additional support may be needed for certain customers, particularly for making claims. Claimants also had suggestions for ways that would make it easier for them to engage with DWP when they needed to, including an online portal or app, a call back service or sending queries by email.

Introduction

Background

Carer’s Allowance (CA), first introduced in 1976, is a benefit of £67.60 a week (2021/22 rates), provided to individuals who care for someone for at least 35 hours a week. CA is uprated annually in line with the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and claimants in Scotland receive an additional supplement twice a year of £231.40.

Claimants must be 16 or over, have lived in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland or Wales for at least two of the last three years, not studying for 21 hours a week or more and their earnings must be £128 or less a week after allowable deductions. The cared-for person must be claiming one of the following benefits: Personal Independence Payment or Attendance Allowance, Disability Living Allowance, Constant Attendance Allowance or Armed Forced Independence Payment.

Various research has been conducted into the experiences and circumstances of CA claimants. Research commissioned in 2011 by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) explored reasons why individuals claim CA and their experiences. It found that claimants struggled to find initial information about the benefit and that CA was a critical source of income and was primarily spent on daily necessities. Further, it found that many carers stopped working when beginning caring due to the difficulty of adjusting work patterns to suit caring needs, and that long-term care had a particular impact on financial welfare. Additionally, in 2020 DWP published estimates of fraud and error levels in the benefit system in Great Britain in the financial year 2019 to 2020. This found that for Carer’s Allowance 5.2% were overpayments, with 3% due to fraud. There were no underpayments found.

Additionally, a Work and Pensions Select Committee inquiry into CA overpayments in 2020 heard evidence about claimants’ experience of overpayments. Failure to report a change in circumstances to DWP was the cause behind most detected overpayments, and letter communications were sometimes seen as insufficiently clear to allow claimants to comply. The Select Committee also heard testimony as to the negative emotional impact for carers when an overpayment is discovered and has to be recovered by DWP.

This research, commissioned by DWP, adds to previous findings, providing up to date information on these topics and further exploring specifically how CA interacts with paid work.

Research aims

There were four key research objectives that were explored in both the qualitative and quantitative research phases.

1. To understand how and why people claim CA.

2. To understand how the caring roles of CA claimants have evolved and changed.

3. To examine how well CA rules are communicated and understood.

4. To gather evidence of claimants’ experiences of combining paid work and care, and their experiences of employment support from DWP.

The research additionally sought to answer five key questions to meet the objectives:

1. What are the household circumstances of CA claimants?

2. What are the different claimant ‘journeys’ into caring and the receipt of CA – including their experience of interacting with other services and support agencies provided by the Authority?

3. What are CA claimants’ experiences of combining work and care?

4. What are claimants’ experiences of claiming CA – including awareness of the benefit, making the initial claim, reporting any changes of circumstance and the processes related to any overpayments?

5. How do the CA rules operate for those recipients in work or considering work?

Method

The research involved four phases outlined below.

Phase 1: Policy immersion and scoping

The scoping phase involved reviewing existing knowledge about CA to inform subsequent phases and ensure they were reflective of political and social contexts. It included policy briefing sessions with DWP and a rapid evidence review of key literature, covering relevant research documents, carers charity webpages and Work and Pension committee reports. Three stakeholder interviews were also carried out with Carers UK, Carers Resource and Professor Sue Yeandle.

Phase 2: Qualitative interviews with claimants

Kantar conducted telephone interviews with 18 CA claimants in August 2020. Respondents were recruited through free-find techniques by specialised in-house recruiters, and recruitment quotas were set to ensure a range of demographic characteristics and views were included. Quotas were set for: gender, age, ethnicity, region, working status, length of time in employment, previous work status, caring intensity, length of time caring, who the cared for person is, if reported change of circumstance and if reported overpayment. See appendix 1 for achieved sample.

Interviews were an hour long and covered:

- Personal circumstances and impacts of Covid-19 on caring and work responsibilities.

- Journey mapping of caring responsibilities, working history, and experiences of CA (including any pain points).

- Support they would like to receive from DWP and perceptions of CA.

Qualitative research was split into two phases, with the first phase designed to produce emerging findings in summer 2020 and inform DWP’s November budget. Respondents were able to redeem £40 in cash to thank them for their time.

Phase 3: Quantitative claimant survey

Kantar carried out a survey of 1021 respondents, using a DWP-supplied sample of CA claimants under State Pension age (16-64 years old). The research team ran a pilot between 20th October – 31st October 2020, and the mainstage research took place between 5th January – 12th February 2021. The sample provided by DWP included contact information along with additional demographic data that was used in analysis, such as age and gender.

The survey gathered information on:

- claimants’ household circumstances and personal demographics

- caring responsibilities

- current and past experiences of paid employment

- experiences of claiming CA

- internet access, and personal use and confidence using the internet

- if they were happy to be re-contacted to participate further qualitative interviews

Kantar conducted cognitive testing before the fieldwork to test clarity and suitability of questions and response options. Interviews were 60 minutes long and conducted over telephone with 10 CA claimants in September 2020. To ensure respondents with a range of views and experiences were interviewed, six respondents recruited were in paid employment, four were not in paid employment, six had reported a change of circumstances to DWP, and two had experienced overpayment.

Participants were contacted by letter, which provided a link to the online survey. If the survey had not been completed, respondents would receive two reminder letters. In the mainstage a paper questionnaire was included in the 2nd reminder letter to boost response rate, improve accessibility of the survey and ensure the views of those with low internet access were gathered. Respondents could redeem a £5 voucher having completed the survey.

The survey gained an overall response rate of 23.4% by online and paper questionnaire. All data was weighted by the ONS Labour Force Survey (July – September 2020) to be representative of CA claimants aged 18-64 in Great Britain.

Phase 4: Qualitative interviews with claimants

A final phase of 42 qualitative in-depth interviews took place following completion of the survey. Participants were recruited from the re-contact sample from the survey by specialist in-house recruiters. Fieldwork took place in February and March 2021 and interviews covered the same topics explored in phase 2.

Covid-19 adaptations and ethical considerations

Fieldwork was carried out during the Covid-19 pandemic and as a result we ensured our research reflected the context it was taking place within. See figure 1 for a timeline of how research sat alongside changing Covid-19 regulations.

Figure 1: British Covid-19 restrictions during fieldwork periods

| Date | Covid-19 restriction | Phase |

|---|---|---|

| August (2020) | 3rd to 31st: Eat out to help out throughout August 14th: Restrictions eased across Britain, including reopening of indoor venues |

Phase 2 |

| September | ||

| October | 14th: Three tier system announced in England 23rd: 16 day circuit breaker lockdown in Wales begins |

Phase 3 (Pilot) |

| November | 2nd: 5 level strategic framework announced in England 2nd: Tighter restrictions announced in Wales 5th: National lockdown for England begins |

|

| December | 2nd: National lockdown ends for England 8th: First person received Pfizer vaccination in UK, beginning start of vaccine roll out 14th: 4 level control plan announced in Wales 19th: Lots of England move into tier 4 over Christmas 19th: Tighter Christmas restrictions in Scotland announced 26th: More areas move into tier 4 26th: Wales enters lockdown |

|

| January (2021) | 5th: Scotland goes into Lockdown 6th: 3rd National Lockdown for England |

Phase 3 (Mainstage) |

| February | Phase 3 (Mainstage) Phase 4 |

|

| March | Phase 4 |

In the survey, those on furlough were asked to answer questions reflecting their circumstances when not on furlough. This was done to gain understanding of usual employment circumstances. Further to this, the qualitative discussion guide incorporated questions about Covid-19 to understand how the pandemic had impacted day to day experiences. Participants were asked about how the pandemic had affected:

- their caring responsibilities and any paid work

- their CA or any other benefit they received

- the person they cared for

During the qualitative interviews, Kantar researchers notified respondents that they could provide a list of support resources. This included contact details for organisations such as Carers UK, Mind Infoline, and NHS advice, and were offered in recognition of the challenging situations of carers, especially given Covid-19.

Analysis

Quantitative analysis

Survey results, along with demographic data provided with the DWP sample, was analysed. All the data was weighted to targets taken from the ONS Labour Force Survey (July – September 2020). These related to gender and age, region, household size, marital status, and housing tenure to ensure they were representative of the population (CA claimants aged 18-64 in Great Britain).

Kantar’s analysis of the quantitative data mainly consisted of descriptive statistics and frequency counts. Some coding was necessary for open-ended responses. Coding was conducted manually and reviewed within the research team. We applied significance testing (p<0.05) to test differences between variables, with differences analysed at aggregate level across subgroups.

Qualitative analysis

A robust and systematic approach was used to analyse the qualitative data collected through the interviews. The analysis was continuous (during, between and after the fieldwork phases) and iterative, moving between the data, research objectives, and emerging themes. The analysis process consisted of two key elements:

- A process-driven element using Kantar’s ‘matrix mapping’ framework technique. Audio recordings of interviews were coded and systematically summarised into an analytical framework organised by issue and theme. The framework was developed to reflect the research objectives and emerging themes and allowed for the sorting of data by theme and case to support sub- group analysis.

- An interpretative element focused on identifying patterns within the data and undertaking sub-group analysis. This process created descriptive accounts and explanatory data, which comes not only from aggregating patterns but by weighing up the salience and dynamics of issues.

Reading the report

During the report Carer’s Allowance claimants are referred to as ‘Claimants’. Charts are used to illustrate quantitative results.

For most survey questions a small proportion of claimants said they did not know the answer or did not answer the question. We have not highlighted these results in the commentary unless they represented a signification number of respondents.

Verbatim quotations are used throughout the report to illuminate and bring to life key findings and are attributed as follows: “Quotation.” (Gender, Age, Relation to cared for person, Employment Status).

Claimants’ household circumstances

This chapter covers demographic and household information about claimants, collected through the survey and supplied sample. It shows the demographic groups claimants belong to, and their general experiences and living situations.

Age and gender

Claimants were primarily women (72%, compared to 29% men) and 35 years or older, with only 4% of claimants being 24 or under. The survey focused on claimants of working age, which was why the sample was limited to those aged 64 or under.

Figure 2. Age of claimants (all respondents)

| Age | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| 24 and under | 2% | 2% |

| 25 to 34 | 4% | 11% |

| 35 to 44 | 5% | 20% |

| 45 to 54 | 8% | 19% |

| 55 to 64 | 10% | 20% |

Gender and age information provided with sample from DWP.

Base: All respondents: 1021.

Region

The research included claimants living in all regions of Great Britain. The highest number lived in the North West (14%) and London (13%), while the smallest proportion lived in the North East (6%) and Wales (5%).

Figure 3. Where claimants live (all respondents)

| Region | Percentage |

|---|---|

| North West | 14% |

| London | 13% |

| South East | 10% |

| Yorkshire and Humber | 10% |

| Scotland | 9% |

| East of England | 9% |

| West Midlands | 9% |

| South West | 8% |

| East Midlands | 7% |

| North East | 6% |

| Wales | 5% |

Regional information provided with sample from DWP.

Base: All respondents: 1021.

Claimant distribution generally reflected regional population sizes in Great Britain (GB). However, the North West had notably more claimants (with 11% of the GB population living in the North West compared to 14% of claimants) and South East had noticeably fewer (with 14% of GB population living in the South East in comparison to 10% of claimants).

Household size, tenure and relationship Status

Claimants were more likely to live with others (92%) than by themselves (6%), with 32% living with one other person, 22% living with two and 38% living with three or more. Overall the average size of a household was 3.23. In comparison, in 2020 the average household size in England is 2.40, Wales 2.32 and Scotland 2.21.

Claimants were more likely to rent or be rent free (70%) than own their homes outright (16%) or have mortgages (14%).

Claimants also tended to be married (42%) or single (38%), rather than divorced (12%).

Who claimants lived with

Many claimants lived with children (62% son / daughter including adopted children) and spouses (45% spouse), with a smaller but still significant amount living with parents / guardians (15%). Women were significantly more likely to live with children (72% compared to 36% of men), and men with parents/ guardians (27% compared to 11% of women) and partners (19% compared to 10% of women).

Figure 4. Who claimant lives with (all respondents)*

| Who claimant lives with | Female | Male |

|---|---|---|

| Son / daughter (including adopted) | 72% | 36% |

| Spouse | 46% | 44% |

| Parent / guardian | 11% | 27% |

| Cohabiting partner | 10% | 19% |

| Brother / sister (including adopted) | 4% | 10% |

| Stepson / stepdaughter | 2% | 9% |

| Grandchild | 3% | 1% |

| Other relative | 1% | 4% |

| Other non-relative | 1% | 4% |

| Parent-in-law | 2% | 1% |

| Civil partner | 1% | 2% |

(Q004 - VBF) Who lives in your household with you?

Base: All who have more than one person in household: 953.

*Chart shows answer codes with 2% or more agreement rate for all respondents.

Household income

Claimants were asked about the highest household earner (of either claimants or their partners if they had one). Few claimants reported that their highest household earner received less than £2,600 or more than £25,999 a year. The income band that the highest household earner most commonly received was £5,200 - £10,399 (18%). Around three in ten claimants (32%) did not identify an income band, either because they did not know the answer, did not select an answer code or preferred not to answer; self-reporting and missing data limit accuracy of findings.

Figure 5. Highest household earner income (all respondents)

| Income | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Under £2,600 | 2% |

| £2,600 to £5,199 | 9% |

| £5,200 to £10,399 | 18% |

| £10,400 to £15,599 | 14% |

| £15,600 to £20,799 | 10% |

| £20,800 to £25,999 | 6% |

| £26,000 to £31,199 | 4% |

| £31,200 to £36,399 | 2% |

| £36,400 to £39,999 | 1% |

| £40,000 to £44,999 | 1% |

| £45,000 to £49,999 | 0% |

| £50,000 to £59,999 | 1% |

| £60,000 to £74,999 | 0% |

| £75,000 to £99,999 | 0% |

| £100,000 or more | 0% |

| Don’t know | 15% |

| No answer | 9% |

| Don’t want to answer | 8% |

(Q056 - VCD_2) Now, please think about whoever earns the most out of you and your partner (if you have one). How much income does the highest earner receive from all sources? This includes all earnings from work, benefits and anything else before any deductions for tax, national insurance and so on.

Base: All respondents: 1021.

Sources of income

Three in ten (32%) claimants, grouped with their partners if they had one, received income other than benefits, tax credits and state pension, with a quarter gaining income from employment or self-employment (25%), and 9% from workplace / personal pensions.

Despite all claimants receiving Carer’s Allowance, only nine in ten (88%) respondents reported income from benefits (including Carer’s Allowance). This suggests that some claimants do not view Carer’s Allowance as a benefit.

Figure 6. Sources of claimant income and that of their partners if they have one* (all respondents)

| Income source | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Benefits (including Carer’s Allowance and disability benefits) | 88% |

| Earnings from employment or self-employment | 25% |

| Tax credits | 21% |

| Other pension (for example workplace or personal) | 9% |

| State Pension | 5% |

| NET: Income other than benefits, tax credits or State Pension | 32% |

Q025 - VCF) From which of the following sources do you and your partner (if you have one) receive income?

Base: All respondents: 1021.

* Chart shows answer codes with >1%.

Qualification levels

Claimants were most likely to have GCSE or equivalent (30%) as their highest level of education or no formal qualifications (23%). Only 11% had university degree or equivalent as their highest education qualification.

In comparison, in 2018 30% of the GB general population had degrees or equivalent as their highest qualification in 2018, with 20% GCSE or equivalent and 9% no formal qualification.

Figure 7. Highest level of education qualification (all respondents)

| Education qualification | Percentage |

|---|---|

| University degree, for example BTEC professional | 11% |

| A-level or Highers or equivalent | 16% |

| GCSE or equivalent | 30% |

| Other qualifications ((including entry level and foreign qualifications below degree level) | 7% |

| No formal qualifications | 23% |

| Don’t know | 9% |

| Refused | 3% |

| No answer | 1% |

(Q047 - VCZ) Which of these is your highest level of education qualification?

Base: All respondents: 1021.

Disability

Many claimants (40%) reported having a mental and physical health condition or illness. Of these people, 58% said that that their condition or illness affected their ability to carry out day-to-day tasks a little, while 17% said it affected them a lot. Of the conditions and illnesses reported, 45% said they had a mental health condition, 30% mobility condition, and 29% something that affected stamina, breathing or fatigue.

Figure 8. Type of illness or condition (all who have an illness or condition)

| Illness of condition | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Mental health condition | 45% |

| Mobility (for example walking short distances or climbing stairs) | 30% |

| Stamina or breathing fatigue | 29% |

| Dexterity (for example lifting or carrying objects, using keyboards) | 17% |

| Memory | 14% |

| Learning or understanding or concentrating | 12% |

| Socially or behaviourally | 8% |

| Hearing | 6% |

| Vision (for example blindness or partial sight) | 4% |

| Other, please specify | 11% |

| Refused | 7% |

| No answer | 2% |

(Q050 - VDC) Do any of these conditions or illnesses affect you in any of these areas?

Base: All who have a condition / illness expected to last for 12 months or more.

Ethnicity

The ethnicity of the survey population generally mirrored the population of England and Wales, however, there were noticeably fewer white respondents in the survey sample (79% v. 86% of the general population in England and Wales).

Figure 9. Ethnic group (all respondents)

| Ethnic group | Carer’s Allowance survey population | England and Wales population |

|---|---|---|

| White | 79% | 86% |

| Asian | 6% | 8% |

| Mixed | 3% | 2% |

| Black | 2% | 3% |

| Other | 1% | 1% |

(Q045 - VCX) What is your ethnic group?

Base: All respondents: 1021 ONS 2011 Census data.

Claimants’ caring roles and responsibilities

This chapter outlines Carer’s Allowance claimants’ caring responsibilities, detailing who they care for, intensity of caring (caring hours and length of timing caring), support accessed, and overall experiences of caring. This chapter draws on evidence from the quantitative and qualitative strands of the research.

Decision-making about caring

The qualitative research explored how decisions were made about who would take on caring responsibilities. In some cases, decisions about caring were not explicitly discussed, and some carers simply fell into their caring roles. Decisions about caring, whether explicit or implicit, often included consideration of employment and earnings; for example, who in a couple had the higher earning potential and whose income they could do without. Someone who was not working, working part-time, or between jobs, was seen to be better placed to provide care.

“I was in-between jobs, it made the most sense.”

(Male, Age 35-44, Cares for child, Self-employed part-time)

“I don’t think it was ever decided. It was just the fact that [my husband] was working full-time, because of the kids I was working part-time and he brought in the better wage.”

(Female, Age 35-44, Cares for child, Employed part-time)

Besides financial considerations, existing caring responsibilities were also a consideration. Where there was a decision to be made about who would be a carer, those without children or others to care for were seen as in a better position to provide care.

“We talked about it as a family. My sister has got children but she is disabled and her children have their own careers and families so it wasn’t possible for any of them to help. I’d never married, so I was quite happy to come home and do that.”

(Female, Age 55-66, Cares for parent, Not in paid work)

Caring for children commonly fell to women, particularly those that were already out of the workforce temporarily due to caring responsibilities, although partners typically supported with this. Those that were caring for spouses or partners were often the main carer by default, as many did not have parents or siblings nearby who could help with caring. In some cases, those that were caring for a spouse or partner were supported by older or adult children. There was often more discussion around who would care for an aging parent if there was more than one child who could provide care. Caring responsibility tended to fall to children who were closer in distance, younger, or more available due to fewer work or family commitments.

Caring responsibilities

Overall, four in five (81%) claimants cared for one person, and 16% cared for two to three people. Examples from the qualitative research included claimants caring for multiple children, in some cases for more than one child with a disability. Other claimants cared for a child or partner for whom they claimed Carer’s Allowance but cared for an elderly parent as well.

Women were more likely to look after two to three people (18%) than men (12%). Additionally, disabled claimants (21%) were more likely to look after two to three people than non-disabled claimants (14%).

Those who had been claiming Carer’s Allowance for longer were more likely to be caring for more people: one in five (21%) claimants who had been caring for five years or more were caring for two to three people, compared with 13% of those claiming between one and three years.

Most claimants (86%) looked after close relatives, with two in five caring for a child (39%), a quarter caring for a spouse or partner (25%), and one in five (22%) caring for a parent.

Figure 10: Person cared for (all respondents)

| Person cared for | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Child (own / adopted / step) | 39% |

| Spouse / partner | 25% |

| Parent | 22% |

| Other relative | 4% |

| Sibling (full / half / adopted / step) | 3% |

| Parent-in-law | 2% |

| Friend | 2% |

| Ex-partner | 0% |

| Other | 2% |

| No answer | 2% |

(Q11-VBN) Who is the person you care for?

Base: All respondents: 1021.

Women were more likely than men to look after a child (49% compared with 13%). Claimants in Scotland (44%), South West (49%), London (46%) and East of England (45%) were also most likely to be looking after a child.

Older Carer’s Allowance claimants were more likely than younger claimants to be caring for a spouse or partner. Over a third (36%) of 55-59 year-olds and more than two in five (44%) of 60-64 year-olds were caring for a spouse or partner, compared with 14% of 35-39 year-olds and 16% of 40-44 year-olds. Men were more likely than women to care for a spouse or partner (43% compared with 18%).

Men were also more likely than women to be caring for a parent (30% compared with 19%). Those in Wales were most likely to be looking after a parent (38%).

Carer’s Allowance claimants were as likely to care for someone under 17 years old (25%) as someone aged 66 or older (24%). Women were much more likely than men to care for someone aged 17 or under (32% compared with 8% men) whereas men were more likely than women to care for someone aged 35-65 (56% compared with 23%). This is consistent with the previous finding that women were more likely to care for a child, and men were more likely to care for a spouse, partner, or parent.

Figure 11: Age of person cared for (all respondents)

| Age | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Under 17 | 25% |

| 18 to 24 | 9% |

| 25 to 34 | 8% |

| 35 to 44 | 7% |

| 45 to 54 | 11% |

| 55 to 65 | 15% |

| 66 + | 24% |

| No answer | 2% |

(Q012 - VBP) How old is the person you care for?

Base: All respondents: 1021.

Claimants aged between 25 and 44 were most likely to care for children under 17 years old (51% of 40-44 year-old carers compared with 17% of 45-49 year-old carers). Those claimants that were age 60-64 years old were most likely to care for those aged 66+ (51% compared with 26% of 55-59 year-olds).

Caring intensity

Time spent caring

In a typical week, half of claimants (52%) spent 65 or more hours caring, whilst just over a third (36%) spent 35-64 hours caring. Notably, just over one in ten claimants (11%) said they cared less than the 35 hours required by Carer’s Allowance. This would suggest that there is not universal understanding of the caring hours requirement amongst Carer’s Allowance claimants. Those who cared for a parent were more likely to say they cared for between 10-34 hours, than those who were caring for a child or partner (16% compared to 8% and 5%).

Figure 12. Hours spent caring for person cared for (all respondents)

| Hours | Percentage |

|---|---|

| 9 hours or less | 1% |

| 10 to 34 hours | 10% |

| 36 to 64 Hours | 36% |

| 65 hours or more | 52% |

| No answer | 2% |

(Q010 - VBM) In a typical week, how many hours do you spend caring for this person?

Base: All respondents: 1021.

Claimants caring for a child spent the most hours caring, being significantly more likely than those caring for a partner or parent to be caring for 65 hours or more (66% compared to 58% and 31%). In the qualitative interviews, participants often described caring for children as being high intensity due to the child’s condition or disability, which meant constant supervision was required.

“I have to constantly check on him all the time.”

(Male, Age 45-54, Cares for child, Not in paid work) “It is quite intense, you have to be on the ball 24/7.”

(Female, Age 45-54, Cares for child, Not in paid work)

Time spent caring was also related to claimants’ working status. Claimants in paid work were more likely to care for 35-64 hours (50% compared with 34% of non- workers) while those not in paid work were more likely to care for 65 hours or more (54% compared with 36%).

Length of time caring

Over half of claimants (54%) had been caring for between 5 and 20 years, and a fifth (22%) had been caring between 1 and 5 years.

Figure 13: Length of time caring for cared for person (all respondents)

| Length of time caring | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Less than a year | 1% |

| Over 1 year but less than 5 years | 22% |

| Over 5 years but less than 20 years | 54% |

| 20 years or more | 16% |

| Not sure / cannot remember | 6% |

(Q015 - VBS) About how long have you been looking after or helping the person you care for?

Base: All respondents: 1021.

Women were more likely than men to be long-term carers of 20 years or more (18% compared with 9%) while men were more likely to have cared for 1-5 years (30% compared with 20% of women). Disabled claimants were also more likely to have cared for 20 years or more (22% compared with 12% non-disabled claimants).

Claimants caring for a child were more likely than those caring for a partner or parent to have been caring for 20 years or more (25% compared with 9% and 5% respectively). Those caring for a partner or parent were significantly more likely than those caring for a child to be caring for between one and five years (24% and 36% compared with 9%).

Figure 14: If main carer for cared for person (all respondents)

| Carer | Percentage |

|---|---|

| I am the main carer and no one else helps care for this person | 67% |

| I am the main carer but others also help care for this person | 31% |

| Someone else is the main carer for this person | 1% |

| No answer | 1% |

(Q013 - VBQ) Thinking about the person you care for, which of the following best describes your situation?

Base: All respondents: 1021.

Two thirds of claimants (67%) were the only and main carer for the person they looked after, while three in ten (31%) were the main carer but receiving some help.

Claimants caring for a spouse or partner were significantly more likely than those caring for a child or parent to say they were the main carer and no one else helped care for this person (84% compared to 61% for a child and 65% for a parent). In line with this, older claimants aged 60-64 were substantially more likely to be the main and lone carer (77%).

In contrast, those in paid work were more likely than those not in paid work to have help with caring (48% compared with 28%). The qualitative research suggests that time spent working meant claimants needed assistance from others with caring.

Some would arrange cover for when they were at work, and others had help with caring overall.

Across the qualitative interviews, claimants expressed a strong preference that they be the ones to care for the person they looked after. This was due to their own preferences, but they said that is what the person they cared for preferred as well.

“Because I think I’m better at [caring] than anyone else.”

(Female, Age 55-66, Cares for child, Not in paid work)

Where claimants had support this was most likely to come from another family member or friend, rather than professional support.

“What I’ve tried to do over the years is to have someone in my family who can step in if I need some time to myself.”

(Female, Age 25-34, Cares for parent, Not in paid work)

Of claimants who had help with caring, more than six in ten (64%) received help from another family member or friend. Claimants aged 35-44 were significantly more likely than claimants aged 55-64 to say that they received help from an educational facility, which reflects their propensity to be caring for children.

Figure 15: Parties helping to provide care (all those who get help)

| Party helping to provide care | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Another family member or friend | 64% |

| Someone who is paid to provide care, such as a professional carer | 18% |

| Educational facility | 17% |

| Day centre | 5% |

| Charity or non-profit organisation | 1% |

| Someone else | 1% |

| No answer | 3% |

(Q014 - VBR) Do any of the parties below help to care for or support this person?

Base: All those who get help: 458.

Although sharing of caring responsibilities and access to support varied, there were key differences depending on the person being cared for. For claimants caring for a child, although there tended to be a main carer, couples often shared caring responsibilities. Some claimants also had help from their parents or other family members to care for children, but said it was often not feasible to rely on them if their

child had a high level of need. Those caring for school-age children had a break from caring during the day when their children were at school. Claimants with adult children sometimes relied on day centres for support with caring, although they tended to feel there were fewer support options available once their child left school.

For claimants caring for a spouse or partner, older or adult children tended to provide cover or ad hoc help with caring. For example, they looked after the cared-for person whilst the main carer did the shopping. Those caring for a partner typically did not have other relatives nearby, such as the sibling or parent of the cared-for person, to provide support caring. Claimants caring for a child or parent were significantly more likely than those caring for a partner to receive help from a family member or friend (36% and 29% compared to 13% of those caring for a partner).

For claimants caring for a parent, it was common for there to be a main carer, but for caring responsibilities to be shared between siblings where feasible. Claimants also commonly said that their parent would be uncomfortable with professional carers and preferred for family members to provide care.

“My mum wouldn’t want anyone else coming to look after her.”

(Female, Age 55-66, Cares for parent, Self-employed part-time)

“It would be stressful for him. He wants to be around people he knows.”

(Male, Age 35-44, Cares for parent, Employed part-time)

Few claimants had accessed respite care, usually because they didn’t qualify for free respite care (for example, through their local authority) and could not afford this themselves. Other claimants said they were entitled to respite, but they did not take this up either because they or the person they cared for would be uncomfortable with it.

Claimants that were supported by professional carers tended to care for someone with high levels of need, such as Parkinson’s or motor neurone disease, who needed health care above and beyond what they could provide themselves.

“She gets carers coming to the house for personal care but she has Parkinson’s so she needs to be fed, she needs round the clock care. [She needs] someone to be with her all the time. Emotional support and food and drink and if she needs changing and medication.”

(Female, Age 25-34, Cares for grandmother, Employed part-time)

Claimants also cited receiving support from social workers, occupational therapists, and other health professionals. Charities like Age Concern and Carers UK were a source of information and guidance for claimants. However, claimants generally felt it was difficult to navigate the support options available and to understand what was available and what they were entitled to.

“It’s too many different people, this one for this, you forget who you’re dealing with, it’s too much.”

(Female, Age 55-66, Cares for parent, Employed part-time)

Claimants’ experiences of caring

In the qualitative interviews, claimants often described caring as challenging and stressful, as they worried about the health and wellbeing of the person they cared for. Although claimants felt a strong sense of duty to care for their family members, they said caring often had a negative impact on their health and wellbeing, as they often put the needs of the person they care for ahead of their own.

“It came down to my wellbeing, I was so stressed and depressed and crying all the time and it became that [my son] had to come before anything else.”

(Female, Age 35-44, Cares for child, Not in paid work)

Claimants struggled with feeling they were always ‘on call’, particularly where they did not have support with caring or someone who could provide cover care for them. It was challenging for claimants to find time to do things for themselves or take breaks, with few reporting taking holidays or other extended breaks from caring.

“I do see myself as a carer, but I’m his wife. In sickness and in health, you know. It would be nice to go away for couple weeks and recharge, there doesn’t seem to be that break.”

(Female, Age 55-66, Cares for Partner, Self-employed part-time)

The strain of caring responsibilities was often compounded by, or contributed to, other difficulties, for example mental health issues or financial worries. Claimants described struggling with mental health issues, and some had sought treatment and support for this, particularly during the Covid-19 pandemic which increased isolation and cut off opportunities for respite like schools and day centres.

Not all claimants were struggling with caring, especially those who were able to manage the needs of the person they cared for (either on their own or with support), and those who were more comfortable financially. Some claimants felt they were managing and coping well.

“We’re managing fine. You do it out of love because it’s your child. I don’t think I would be able to do it as a job.”

(Male, Age 35-44, Cares for child, Self-employed Part-time)

Claimants’ experiences of combining care and work

The chapter explores claimants’ experiences of combining care and work, more specifically it explores the facilitators and barriers to claimants being in paid employment and the extent to which Carer’s Allowance requirements influences employment decisions.

Claimants’ employment status and history

Current employment status

Only 16% of Carer’s Allowance claimants were in paid work, while seven in ten (72%) were not in paid employment.

Figure 16: Employment (all respondents)

| Employment | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Not in paid work | 64% |

| Employed part-time (working 30 Hours or less) | 8% |

| Retired from paid work | 6% |

| Self-employed part-time | 4% |

| Voluntary work | 3% |

| Zero hours contract | 2% |

| Self-employed full-time | 1% |

| Employed part-time | 1% |

| Other | 10% |

| NET: Not in paid work | 72% |

| NET: In paid work | 16% |

(Q018 - VBW) In addition to your caring role, please tell us which of the following also applies to you?

Base: All respondents: 1021.

Men were slightly more likely to be out of paid work than women (78% compared with 70% of women). However, women were more likely than men to be employed part- time (10% compared with 4% of men).

There was also a relationship between claimants’ employment and their education. Those with degrees as their highest educational qualification were significantly more likely to be in paid employment (26%) than those with no qualifications (12%).

Claimants caring for a spouse or partner were significantly more likely to be out of paid work compared to those caring for a child (78% compared to 70%). Similarly, claimants caring for a child were significantly more likely to be in paid work compared to those caring for a spouse or partner (20% compared to 11%). The qualitative interviews suggested that this was because children going to school or another care setting provided an opening during the day for claimants to work.

“Most of my friends tend to have a child who is the disabled person that they care for, and I find that’s very different, because in general, a child goes off to a care setting each day, so they’ve got time on their own. And normally their partner can carry on working so it doesn’t affect finances too much, and they’ve got that extra freedom of time. But when it’s your partner, it affects your time 100%, and it affects your income 100% as well so I just feel it’s quite tricky in this particular situation that it affects so many things.”

(Female, Age 55-66, Cares for partner, Not in paid work)

Previous experiences of employment

Before starting caring, half of claimants (52%) said they had always or mostly been in paid employment.

Figure 17: Employment history before caring (all respondents)

| Employment history | Percentage |

|---|---|

| I have always been on paid employment | 27% |

| I have mostly been in paid employment | 25% |

| I have been in and out of paid employment | 21% |

| I have mostly been out of paid employment | 14% |

| I have never been in paid employment | 10% |

| No answer | 4% |

(Q027 - VCH) Overall, which of the following statements best describes your work history before you started caring. Please include any part-time work or self-employment.

Base: All respondents: 1021.

Around half of claimants (45%) said they were in and out, mostly out, or never in paid employment prior to caring. As with current working status, education level was relevant to claimants’ history of working. Those with no formal qualifications were more likely to fall into the latter three categories (57%), compared to those with a Degree (24%), A-level (26%) or GCSEs and equivalents (42%) as their highest level of qualification.

This finding and the qualitative research suggest that there were pre-existing barriers to working before claimants started caring. In some cases, health issues or disabilities prevented claimants from working.

“I am not really working. I am disabled and I receive PIP.”

(Female, Age 35-44, Cares for partner, Not in paid work)

“I haven’t worked for some time and this has been due to my health issues. I knew that if I were to be in work I’d probably get fired because I’d have to take so much time off.”

(Female, Age 25-34, Cares for parent, Not in paid work)

Claimants in paid employment

Types of employment claimants engaged in

The qualitative research provided an indication of the types of work claimants that were employed or self-employed engaged in. Claimants in paid work tended to work part-time in lower paid jobs that they were able to fit around their caring responsibilities. Of those interviewed in the qualitative research, claimants worked as a cleaner, teaching assistant, childminder, taxi driver, hairdresser, shop worker, supply teacher, and some even worked as paid carers. These types of roles tended to be flexible and offered claimants control over their working hours, especially if they were self-employed. This helped claimants to fit working in with their caring responsibilities.

“Because it’s my business, I tend to take on as many jobs as I can but I’m very mindful of making sure I have enough time to be here [at home caring].”

(Female, Age 45-54, Cares for partner, Self-employed full-time)

Some claimants had already been working in these types of roles before they started caring, whilst others had changed their roles to fit in with caring.

“Because [the SEN school] was so far away and all the problems I was having with him, the meltdowns, I had to give up my job and take up a part-time cleaning job.”

(Female, Age 25-34, Cares for child, Employed part-time)

Figure 19: Case Illustration: Female, aged 25 to 34, cares for child, in paid work

This claimant is a single mum with two children. The person she cares for is her 12-year- old son, who has Autism and ADHD. He’s been non-verbal since age 5, and he needs help with dressing, washing, eating, and day to day tasks. As well as Carer’s Allowance, she receives Universal Credit and Child Benefit, and her son receives DLA.

She used to work full-time as a catering manager, but when her son transferred to a SEN school, it was much further away and she kept getting called away from work to pick him up. As a result, she left the catering job and started a cleaning job. She was promoted, and now works as an operations manager for the cleaning company. She works 12 to 15 hours per week, but she has flexibility on when she works.

Hours worked in employment

Most claimants (81%) in paid employment worked 20 hours or less a week, with half (47%) working up to 10 hours and a third (34%) working 11-20 hours. Less than 10% worked 31+ hours per week. The threshold of 16 hours of work is also significant for Working Tax Credits[footnote 1] and childcare support, as claimants must work at least 16 hours a week to qualify. Seven in ten (72%) Carer’s Allowance claimants worked up to 15 hours per week. Only one in four (27%) Carer’s Allowance claimants worked 16 hours or more per week.

Figure 20: Number of hours worked (% all in paid employment)

| Number of hours worked | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Up to 10 hours a week | 47% |

| 11 to 20 hours a week | 34% |

| 21 to 30 hours a week | 9% |

| 31+ hours a week | 8% |

| No answer | 2% |

(Q019 - VBX) On average how many hours per week do you do paid work?

Base: All in paid employment: 165.

Of those in paid employment, 43% said that their hours changed from one week to the next. The qualitative interviews suggest this may be because claimants adapt their hours around the needs of the person they care for. As previously discussed, claimants often had some control over their hours, however, some claimants reported having to take unpaid leave due to caring responsibilities.

“If I need to take time off, I just don’t get paid.”

(Female, Age 55-66, Cares for parent, Employed part-time)

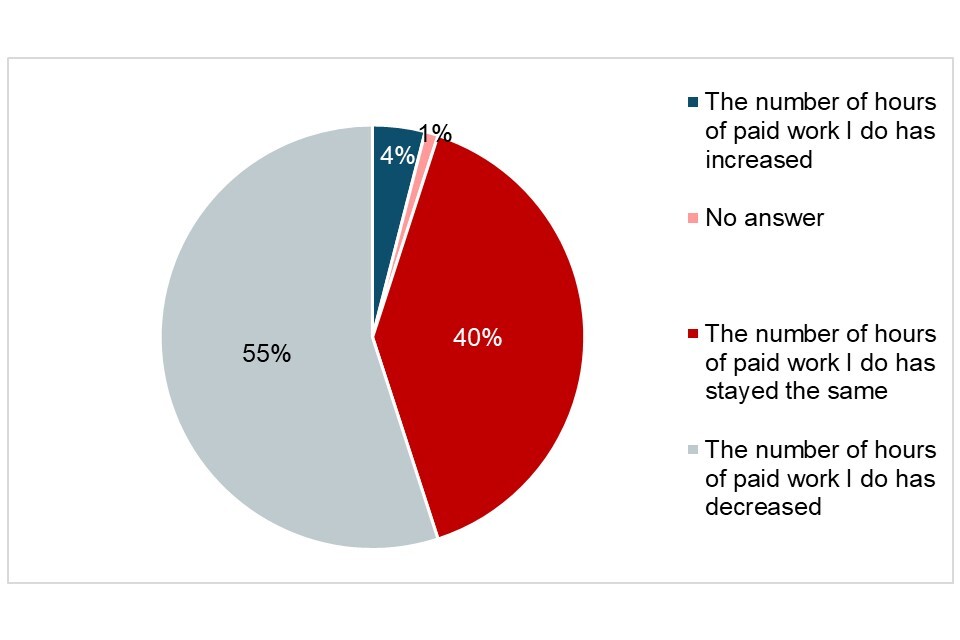

Over half (55%) of claimants in paid work said that the number of hours they work had decreased because of caring responsibilities. Four in ten (40%) claimants in paid work said that the number of hours they work had stayed the same, whilst 4% said the number of hours they work had increased.

Figure 21: Impact of caring on hours worked (all in paid employment)

(Q022 - VCB) Thinking about combining your paid work and caring responsibilities, what impact has caring had on the number of hours of paid work you do each week?

Base: All in paid work: 165.

In the qualitative research, some claimants also said that the nature of their roles also changed when they reduced their hours due to their caring responsibilities.

“It was the same organisation, but a different role, because when I reduced my hours the work that I was doing needed to be full-time, so I had to take up a different role which was less involved. It also affected my pay so I had a drop of income.”

(Male, Age 24-34, Cares for parent, Employed part-time)

Earnings from employment

Three quarters (74%) of those employed said they earned under the £128 per week Carer’s Allowance earnings threshold[footnote 2], while one in ten (9%) earned over the earnings threshold[footnote 3].

Figure 22: Earnings from paid work per week (all in paid employment)

| Earnings | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Under £25 | 10% |

| £25 to £49 | 8% |

| £50 to £74 | 17% |

| £75 to £99 | 12% |

| £100 to £124 | 27% |

| £125 to £149 | 6% |

| £150 to £174 | 2% |

| £175 to £199 | 4% |

| £200 to £224 | 0% |

| £225 to 249 | 0% |

| £250 to £274 | 1% |

| £275 to £299 | 1% |

| £300 or more | 1% |

| Don’t know | 7% |

| Don’t want to answer | 4% |

| No answer | 1% |

(Q023 - VCC) On average, how much do you earn from your paid work in a week, before any deductions?

Base: All in paid work 165.

Facilitators to being in paid employment

For those claimants who were in paid employment, there were consistent factors that enabled them to balance working and caring. Claimants in paid work tended to have jobs where they had some control over their schedule, for example cleaning in a private home or hairdressing.

“I took the opportunity to manage the cleaning side because it fits so well with my son’s needs. I’m one of those people who has to work, and I took on something that was a bit more flexible for my needs.”

(Female, Age 25-34, Cares for child, Employed part-time)

Having some control over their working hours enabled them to adapt when unexpected issues arose with the person they care for. Claimants that were employed also cited having a flexible employer who understood that issues might arise unexpectedly and would let them take time off when they needed to.

“[My daughter] always came first, and all of the jobs that I had were always sympathetic, so I would either take unpaid leave or holiday, quite a few of the jobs were flexi-time so I could work around [her] hospital appointments.”

(Female, Age 55-66, Cares for child, Employed part-time)

For claimants that were caring for parents or spouses or partners, in some cases the person they cared for did not require around the clock supervision, so they could fit in caring responsibilities around work. For claimants caring for school-age children, jobs that could be done during school hours, or having a partner who they could share childcare with facilitated being able to work.

Claimants not in paid employment

Reasons for not currently being in employment

Of claimants that were not currently in paid work, seven in ten (69%) said this was due to their responsibilities as a carer claiming Carer’s Allowance[footnote 4]. This finding aligns with reasons given for not working according to length of caring hours. Those who cared for 35-64 hours (70%), or 65 hours or more (73%) were more likely than those caring for 10-34 hours (53%) to say they were not be working due to those caring responsibilities.

Figure 23: Reasons for not currently being in employment (all not in paid employment)

| Reason for not currently being in employment | Percentage |

|---|---|

| My responsibilities as a carer claiming Carer’s Allowance | 69% |

| Additional caring responsibilities for children or other elderly or disabled people | 12% |

| I am long-term sick or disabled | 6% |

| I am retired | 3% |

| I am unemployed and seeking work | 2% |

| I am a student or in training | 1% |

| I was made redundant | 1% |

| Another reason | 1% |

| No answer | 3% |

(Q026 - VCG) What is the main reason why you are not currently in paid employment or self- employment?

Base: All not in paid work: 832.

Additional caring responsibilities beyond those related to Carer’s Allowance were a barrier to working for claimants not in paid work, with one in ten (12%) citing this as the reason they were not currently working. In line with their likelihood to be caring for more than one person, women were significantly more likely to report additional caring responsibilities (14%) than men (5%) as the reason they were not currently in paid employment.

Claimants aged 35-49 were significantly more likely than those aged 55-64 to have said that additional caring responsibilities currently stopped them working. This may be because adults in this age group were likely to have young children; claimants caring for a child were significantly more likely to say additional caring responsibilities stopped them working compared to those caring for a spouse or partner (16% compared to 7%).

In the qualitative interviews, none of the Carer’s Allowance claimants were currently receiving employment support. Some said they had been told by Jobcentre staff that they did not have to look for work because they were carers so did not need to receive any employment support.

Reasons why claimants initially left employment

In the qualitative interviews, claimants said that the reason they initially left work was not the same as why they were currently not working. A common example in the qualitative research was women who left the workforce for maternity leave and planned to return, but when it became clear that their child had additional care needs, they were not able to return as planned.

There is also evidence of this in the quantitative research. Half of claimants (50%) reported they last stopped working due to their responsibilities as a carer claiming Carer’s Allowance, while two in ten (19%) said they initially stopped because of other caring responsibilities. Women were more likely to report they initially left the workforce due to additional caring responsibilities than men (24% compared to 19%).

Figure 24: Reason why stopped last job in paid employment (all not in paid employment)

| Reason why stopped last job | Percentage |

|---|---|

| My responsibilities as a carer claiming Carer’s Allowance | 50% |

| Additional caring responsibilities for children or other elderly or disabled people | 19% |

| I am long-term sick or disabled | 7% |

| I was made redundant | 6% |

| I was temporarily sick or disabled | 4% |

| I retied | 1% |

| I started university or training | 1% |

| I did not need paid employment | 1% |

| Another reason | 5% |

| No answer | 5% |

(Q029 - VCK) Thinking about the last time you were in paid employment or self-employment, which of the following best describes the reason you stopped working.

Base: All not in paid employment: 832.

Length of time out of the workforce

Around six in ten (58%) claimants not in paid work had been out of employment or self-employment for over five years, while three in ten (32%) had been out of the workforce for between one and five years. Claimants caring for a child were significantly more likely than those caring for a parent to be out of the workforce for 20 years or more (19% compared to 9%). Women were also significantly more likely than men to be out of the workforce for 20 years or more (17% compared to 10%).

Figure 25: Time since been in paid employment (all not in paid employment)

| Time since been in paid employment | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Less than a year | 4% |

| Over 1 but less than 5 years | 32% |

| Over 5 but less than 20 years | 43% |

| 20 years or more | 15% |

| No answer | 7% |

(Q028 - VCJ) How long has it been since you were last in paid employment or self-employment?

Base: All not in paid work: 832.

Barriers to being in paid employment

Caring responsibilities

For claimants not in paid work, as previously discussed, the main reasons cited for not working were caring responsibilities related to Carer’s Allowance (69%) and additional caring responsibilities (12%). As previously mentioned, claimants also expressed a strong preference for being the one to care for their loved one, rather than having someone else look after them to enable them to work.

“No, I’d worry too much for work, cause if I went to work, I’d have to have someone come in to care for [her], so it’d make no sense really. I feel like I need to be the one that does it.”

(Female, Age 45-54, Cares for child, Not in paid work)

Claimants expected working and caring would create additional stress for them, particularly if they already tended to find caring quite challenging. Some claimants had previously been working and caring but found it too physically and mentally draining.

“I was bringing up the girls and then went back to work, I was a PA but I found it really challenging to work all day, part time, 16 hours and then have [my son]. It just drained me so I gave it up.”

(Female, Age 35-44, Cares for child, Not in paid work)

Some claimants who were caring for young children were not considering work at present but kept open the possibility in the future when their children were older.

“I’ve come to terms with the fact that [my son] comes first, and hopefully when he gets older I can go back to full-time work.”

(Female, Age 35-44, Cares for child, Not in paid work)

A lack of flexible employment options

A lack of flexible employment options was also a barrier to claimants working whilst caring. Claimants worried about, or had previous experiences of, being ‘unreliable’ which they said some employers were not willing to deal with. This was also a barrier at the interview stage.

“When you’re asking [an employer] to be flexible it is harder to get a yes, especially when you don’t have the highest skillset and training.”

(Female, Age 35-44, Cares for parent, Not in paid work)

Claimants who cared for school-age children felt they were always ‘on call’, even when their children were at school, and those that had previously worked said they were often called away.

“I lost my job because I had to keep leaving my job to pick him up from school. They said they couldn’t accept me because I was unreliable.”

(Female, Age 35-44, Cares for child, Not in paid work)

“It’s almost like they lose their trust in you, and you feel bad. They have a certain amount of understanding but because it’s a business but there is a limit to that understanding, and that can make you feel bad and make you want to quit anyway”

(Female, Age 35-44, Cares for child, Not in paid work)

Health conditions or disabilities

Long-term health issues and disabilities were also barriers to working for some claimants. Of claimants not in paid work, 6% said this was because they were long- term sick or disabled.

“I would possibly [consider work], I have my own health issues myself. I have arthritis in my ankles and my hands. I think I would struggle to find something and to manage everything at home.”

(Female, Age 45-54, Cares for partner, Not in paid work)

“I haven’t worked for some time and this has been due to my health issues. I knew that if I were to be in work I’d probably get fired because I’d have to take so much time off.”

(Female, Age 25-34, Cares for parent, Not in paid work)

Financial considerations

Claimants also weighed up the financial costs and benefits to working. In some cases claimants said it was not a necessity for them to be working. Some claimants had partners who supported the family, and they were able to manage with one income.

One participant was previously working as a high-rate taxpayer, and he was living on his savings while caring for a partner with a terminal illness.

If there was not a partner to support the household, or it was their partner that the claimant was caring for, claimants and their household often relied on benefits, such as Universal Credit, Housing Benefit, Income Support, and Tax Credits. Where benefits were involved, in some cases claimants felt they might be worse off due to the cost of childcare or loss of other benefits if they went back to work.

“I couldn’t afford to live if I went back to work, but I could on benefits.”

(Female, Age 35-44, Cares for child, Not in paid work)

This was particularly relevant where claimants felt they did not stand to earn very much from the jobs they could do, and so working was not seen as appealing due to the additional time and stress on top of the caring they were doing.

“If the option is you can have this minimum wage job, you have to work all week and you have to have somebody raise your child for you because you have to work, that’s not an option because [my son] is more important than the job.”

(Female, Age 25-34, Cares for child, Not in paid work)

Lack of confidence

As previously mentioned, 58% of claimants not in paid work had been out of the workforce for 5 years or more. Claimants said that this time out of the workforce had impacted on their confidence.

“I’ve also lost confidence over the past 5 years - my confidence has completely plummeted. I don’t know what I could offer the workplace to be honest, in the future.”

(Female, Age 55-66, Cares for partner, Not in paid work)

Impact of Carer’s Allowance on employment

Although the earnings limit factored into claimants’ decisions about whether and how much to work, it was part of a wider calculation weighing up caring responsibilities, potential earnings, and the impact of working on their quality of life and well-being.

While claimants did not speak about it in this way, they appeared to be trying to maximise their earnings and income via wages and any other benefits whilst also managing their caring responsibilities.

“I need to get a part time job that exceeds amount [of benefit]. Got to be worth it really - don’t want to stress myself out anymore.”

(Female, Age 55-66, Cares for partner, Not in paid work)

Getting a job or working more hours would increase the amount of work claimants would be doing on top of caring, which they felt would have a negative impact on their wellbeing. Many also felt there would not be a financial benefit from working or working more. Though the considerations were similar for all claimants, there were some differences between those claimants that were in paid work and those that were not.

Impact for claimants in paid work

For claimants in paid work, the earnings threshold appeared to influence decisions about how many hours they worked. Even though claimants often denied that the threshold influenced their choices, they acknowledged being mindful to stay below the threshold. One claimant felt he had to refuse shifts at work that would take him over the threshold.

“I made sure it was within. Because otherwise I’d work more hours for less money.”

(Female, Age 35-44, Cares for parent, Not in paid work)

“There can be some stressful moments around work and I have to refuse shifts and the team leader has given me a shift I can’t do or take me over my hours or limit, I would like to work but if it’s going to take me over the earnings limit. If it was based around hours worked per week rather than earnings.”

(Male, Age 25-34, Cares for parent, Employed part-time)

In another example, the earnings limit led a claimant to reduce her hours as her wages increased, and eventually she was working so few hours, her employer felt it was not worth employing her due to her limited availability.

“In the end he said I don’t think its worth you working [here]. So I left that job, it was stressful having to do that and embarrassing as well.”

(Female, Age 55-66, Cares for child, Not in paid work)

Figure 26: Case Illustration: Female, aged 55-66, cares for child, not in paid work

This claimant lives in Wales with her husband and cares for her adult son who has Down’s Syndrome. Her son needs help with practical tasks and supervision, so she does his cooking, cleaning, and helps with his finances (as he typically works in a restaurant).

She most recently was self-employed doing singing sessions in care homes, but she is not working at the moment. Her husband and son are furloughed from restaurant jobs. Once her son finished comprehensive school, she started taking on part-time jobs as a dinner lady, shop worker, post-office worker. She previously worked at Boots for 5 years, but she felt she had to keep reducing her hours when she got a pay rise to stay under the earnings limit.

She’s been receiving Carer’s Allowance for over 30 years, though she has stopped receiving it at points. She previously worked as a manager of a café for a while, which took her over the earnings limit, but she eventually stopped this job because it was ‘exhausting’ and she ‘couldn’t keep up’.

Some claimants in paid work felt they might work more hours if not for the earnings threshold, and even suggested tapering earnings in Carer’s Allowance to encourage claimants to work more. However, claimants in paid work felt there was a practical limit to the hours they could work. Many felt it was only feasible to be working part- time due to their caring responsibilities.

“It definitely affects me. I think it would be really good if they could do it in a tiered way, or in stages, so as you work more, your money went down. Because I think that’s a bit daunting. I think that would encourage you more to get more hours’ work.”

(Female, Age 35-44, Cares for child, Employed part-time)

“I did notice you could only earn a certain amount of time. With my situation it didn’t make a difference, but I would have had to give up full time work regardless.”

(Female, Age 55-66, Cares for partner, Self-employed part-time)

For claimants with children, arranging childcare and the associated costs were a barrier to working more. Any additional income from paid work would need to cover cost of childcare.

“[Working more] is something we considered, if it paid well, and we could get the balance right between us working and stuff like that. We’d need to be able to afford childcare.”

(Male, Age 35-44, Cares for child, Self-employed part-time)

Claimants who mentioned the cost of childcare did not spontaneously raise that some childcare expenses could be deducted from their income, suggesting they might not be aware that this is an option for them. However, as previously stated, most claimants (64%) received help with caring from family or friends, which means these costs might not be eligible to be deducted.

Particularly for low paid workers, they felt they would have to work quite a few more hours to cover the loss of Carer’s Allowance and potentially other benefits. Therefore, there was not a strong financial incentive for claimants to work more as they felt they may not be in a better financial position after factoring in cost of childcare and the loss of Carer’s Allowance and potentially other benefits.

“What you have to think about, if you are going to take on more hours, the hours that you take on, need to cover that loss of income.”

(Female, Age 55-66, Cares for child, Employed part-time)

As well as lacking a financial incentive, claimants also felt working more hours would increase their stress.

Impact for claimants not in paid work

Like claimants in paid work, those not in paid work felt the amount they stood to earn from taking on a part-time job was not worth the loss of Carer’s Allowance and potentially other benefits as well. They also expected that working would create additional stress.

“I don’t think it would help me at all. I wouldn’t be able to do a full-time job to make it worth my while. When I was working as a dinner lady I was earning £6.30 an hour, so the monthly pay was about £110. So that wouldn’t be worth it because that would impact housing benefit and council tax, and then that £110 would just reduce my housing benefit and council tax benefit. It would have no financial impact at all.”

(Female, Age 45-54, Cares for child, Not in paid work)

“A part time job would be ideal for me but it is extra effort going out of the house, and extra stress and responsibility doing that when I’ve still got everything to do here as well. Is it worth challenging myself with all I’ve got to do here and the stress that goes with that, and I’ve got my own health problems as well.”

(Female, Age 55-66, Cares for partner, Not in paid work)

Figure 27: Case Illustration: Female, age 55-66, cares for partner, not in paid work

Claimant lives with her husband and two adult daughters (age 18 and 21). She cares for her partner who has progressive MS, but also cares for her elderly mum who has dementia and lives alone. She helps her partner with dressing and personal care, manages his medications, takes him to appointments, and she also does all the cooking.

When her partner’s condition started to worsen 5 years ago, her caring responsibilities intensified, and she took voluntary redundancy at her job. She finds being a carer difficult, and she has arthritis herself, but she feels there is not a better option. The Local Authority have said she should have people to help her with caring, but the cost of this is a barrier.

They are just about managing financially, and they are able to pay their mortgage. She gets a small pension, and her partner runs a small trucking company (now just 1 employee) which generates a small income. She also receives Working Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit, but this will stop now her daughter is 18.

She would like to have a job, but it is hard because she needs to be able to take her partner to appointments, and she worries whether she could find an employer that is flexible. She also worried that working on top of everything she was currently doing would take her over the edge.

Some felt that if they were able to work full-time there would be a financial benefit, but most felt working full-time wasn’t feasible due to their caring responsibilities. Like claimants in paid work, claimants considering work also raised the cost of childcare as a potential barrier.

“I know with Carer’s Allowance you’re only allowed to earn a hundred and whatever pounds it is per week before it affects your Carer’s Allowance. And we get Universal Credit. I don’t think it would be beneficial for me to do a part time job, if we were both working full-time and I was doing the job I was doing previously, then we would be a lot better off.”

(Female, Age 25-34, Cares for child, Not in paid work)

Experiences of claiming and receiving Carer’s Allowance

This chapter explores claimants’ experiences of Carer’s Allowance from first becoming aware and making the claim to their experiences of receiving Carer’s Allowance. This chapter also covers reporting changes to DWP and experiences of overpayment of Carer’s Allowance.

Becoming aware of Carer’s Allowance

Claimants tended to hear about Carer’s Allowance from family and friends or medical professionals. Two in ten claimants (20%) reported hearing about Carer’s Allowance from family and friends.

A similar proportion (18%) of claimants reported hearing about Carer’s Allowance from a doctor, nurse, or other medical professional. They tended to be signposted early in their caring journey when medical professionals were engaged to support the person they care for.

“I was advised to apply for it by the occupational therapist, after a multi-disciplinary meeting, because I had said that I would have to give up work. She put me in touch with money matters and other advice services.”

(Female, Age 25-34, Cares for grandparent, Employed part-time)

“It was when we first had a health visitor about [our son’s] autism. They told us we could apply for DLA, and it was through that we found out we could get Carer’s Allowance.”

(Male, Age 35-44, Cares for child, Self-employed part-time)