Fighting Fraud in the Welfare System

Updated 13 May 2024

Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions by Command of Her Majesty

May 2022

CP 679

Crown copyright 2022

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated.

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at: www.gov.uk/official-documents

Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at: fraudanderror.policyandlegislation@dwp.gov.uk

ISBN 978-1-5286-3294-2

ID EO2740441 05/22

Ministerial Foreword

Anyone who has been a personal victim of fraud will know first-hand how damaging the financial and emotional impact can be. Similarly, fraud committed against the welfare system and wider public sector – whether by individuals or criminal gangs – is not a victimless crime. Its impact is felt throughout society, upon the services people rely on and by honest, hard-working taxpayers who expect to see public money spent on the purpose for which it was intended rather than going into the hands of criminals.

This document sets out our long-term plan to fight fraud against the welfare state, building on our long-standing and successful principles to prevent, detect and deter benefit fraud.

We are investing £613.0 million over the next three years as a boost to our counter-fraud frontline, introducing thousands more counter-fraud professionals, as well as measures to improve how we use and analyse data to respond to emerging threats.

Some of the key legislation DWP relies on is now over 20 years old. We plan to modernise and strengthen our powers. Subject to parliamentary time, we will legislate for new powers to help our officers investigate potential fraud and apply new penalties to punish fraudsters.

With the approaches fraudsters take constantly evolving, we will stay one step ahead by setting out how we will take a more coordinated approach, working within and beyond government to tackle fraud. We will do this by bringing together the full force of government and the expertise of the private sector, working with the new Public Sector Fraud Authority announced by the Chancellor at the Spring Statement.

This plan will help us stop people illegally taking advantage of our benefits system, catch and punish fraudsters and recoup more taxpayers’ money.

The Rt Hon Thérèse Coffey MP, Secretary of State for Work and Pensions.

David Rutley MP, Minister for Welfare Delivery.

Executive Summary

1. Fraud is an ever-present challenge in both the private and public sector.

2. While the digital economy has brought enormous advances and advantages, including to the way that we deliver benefits, it has also increased opportunities for criminals to commit fraud at a scale and sophistication not possible in the past.

3. In DWP, the digital design of Universal Credit (and the increasing digitalisation of wider benefits) has reduced manual processing and we have innovated in how we can use data to achieve outcomes more effectively and efficiently. Using a direct Real Time Information feed from HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) to accurately assess the earnings of claimants paid through the PAYE[footnote 1] system has enabled us to tackle the biggest source of fraud by monetary value in DWP – false declarations about earnings for means-tested benefits.

4. Before the pandemic hit, as Universal Credit expanded and started to replace DWP legacy benefits and Tax Credits, fraud and error[footnote 2] across the DWP benefits system and Tax Credits were near a record low.

5. The pandemic saw a significant increase in fraud. We prioritised getting money to millions of people who needed it as part of our emergency response. Regrettably, as we saw across government and internationally, some individuals and groups – both organised and opportunistic – sought to exploit the situation and the accelerated processes for accessing help that were temporarily in place.

6. In response, we took action to identify and stop abuse of the system which prevented billions from ending up in the wrong hands, including stopping £1.9 billion going to organised criminal groups who had stolen the identities of innocent citizens in an attempt to steal taxpayers’ money. We have also carried out retrospective reviews of claims made in the early part of the pandemic to identify fraudulent cases. In 2020/21, our interventions reduced potential losses by around £3.0 billion.

Our plan to bring down fraud

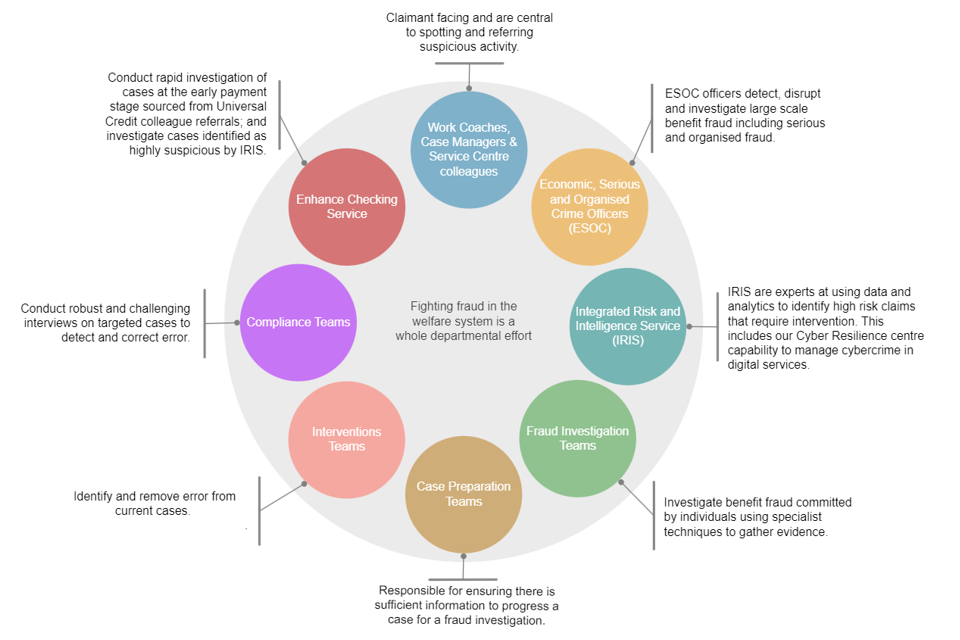

7. Our fundamental approach has always been to prevent fraud from entering the system in the first place, to detect and root out fraud when it does, and to deter would-be fraudsters through a robust penalty system, including recovering the debt owed. These principles were bringing fraud down before the pandemic and will continue to underpin our plan.

8. However, we now face a much greater fraud challenge than before the pandemic. Our analysis shows that the key areas where fraud is highest include: misrepresenting earnings including self-employed earnings; failing to declare or under-reporting capital; failing to declare a partner contributing to the household; incorrect reporting of housing costs; and failing to declare moving abroad or dishonestly applying for benefits while living abroad.

9. To tackle these key risks, we will step up how we fight fraud, focusing on three fronts:

- Investing in DWP’s frontline counter-fraud professionals and data analytics. Through an extra £613.0 million investment over three years we are boosting our frontline defences by 75%. This will stop an estimated £2.0 billion of loss in fraud and error over the next three years, and over £4.0 billion of loss over the next five years. This includes 1,400 more staff in our counter-fraud teams, a new 2,000-strong team dedicated to reviewing existing Universal Credit claims and enhanced data analytics to develop new ways to prevent and detect fraud.

- Creating new legal powers to investigate potential fraud and punish fraudsters, subject to parliamentary time. Much of DWP’s counter-fraud legislation that our officers use to investigate potential fraud is now decades old. Subject to parliamentary time, we will legislate to update their powers to boost access to data from third parties and carry out arrests and searches and seize evidence. This will enable them to act more quickly to identify, detect and disrupt fraud, particularly from organised criminal gangs and wider economic crime. We will also bring in a new civil financial penalty, so more fraudsters pay for their crimes. This will modernise DWP’s fraud fighting powers and bring them more in line with other parts of government tackling fraud.

- Bringing together the full force of the public and private sectors to keep one step ahead. We will work with the new Public Sector Fraud Authority to bring the full force of government to bear on public sector fraud. We will also create a new Fraud Prevention Advisory Group to bring together government and external experts to identify and develop innovative ways to crack down on fraudsters, including through more flexible and proactive use of data. Through the new £30.0 million Fraud Prevention Fund, over the next three years we will research, invest in, test and trial creative ways to tackle new and emerging threats.

10. By stepping up our investment, updating our legal powers, and bringing together the best of government and the private sector, we will arm ourselves to defend the welfare system against fraud for years to come.

Introduction

The nature and scale of fraud prior to the pandemic

11. The nature of fraud has changed over the last 20 years. While the digital economy has brought enormous advances and advantages including to the way that we deliver benefits, it has also increased opportunities for criminals to commit fraud at a scale and with a sophistication not possible in the past.

12. Fraud is now the most commonly experienced crime in the UK, accounting for 42% of all crimes[footnote 3]. While these are mainly offences against individuals and businesses, fraud is also an increasing challenge in the public sector. Prior to the pandemic, the cost of public sector fraud was £29.0 billion[footnote 4].

13. DWP has one of the most robust counter-fraud functions in government. Our fundamental approach has always been to: prevent fraud from entering the system in the first place; detect fraud where it enters the system and root it out; and deter would-be fraudsters through a robust penalty system, including recovering the debt owed.

14. This approach meant that before the pandemic, fraud and error across the DWP benefits system and Tax Credits were near record lows. We had already started deploying innovative techniques to tackle fraud and error, for example using a direct Real Time Information feed from HMRC to accurately assess the earnings of claimants paid through the PAYE system for DWP – false declarations about earnings in means-tested benefits.

15. Since the start of the pandemic, however, the level of fraud has increased across the public and private sectors. In March 2020 and the months that followed, when our standard checks such as face-to-face verification were not available to use, Universal Credit stood up to an unprecedented number of claims, supporting an extra three million people.

16. While prioritising getting money rapidly to those who needed it, we also took action to identify and stop abuse of the system. For example, in May 2020, our Cyber Resilience Centre identified an attack against Universal Credit involving hijacked identities, which working collaboratively with our Economic, Serious and Organised Crime teams led us to suspend 152,000 fraudulent claims and prevent £1.9 billion in benefits from being paid to people trying to scam the system.

17. During the pandemic, the level of self-employment earnings fraud and error in Universal Credit in particular increased, from 1% of total Universal Credit payments in 2019/20 to 3.8% in 2020/21. This was partly due to the length of time during which we allowed easements to the benefits system in order to provide financial support to the self-employed, which we aligned with the running of the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme and the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme. We have now re-introduced our standard approach with interviews and relevant income tests and have already made improvements to the mechanism for reporting income and expenses.

18. We have also set up two new teams to improve fraud prevention and detection. The Enhanced Checking Service and Disrupt team, which prevents losses by intervening in high-risk cases before payments have been issued, is estimated to have saved £800 million in 2020/21. Our Integrated Risk and Intelligence Service, maximising our cyber capability, helped teams identify new fraud threats. Together, they disrupted or corrected over 298,000 claims during 2020/21. Without taking actions like these, nearly £3.0 billion would now be in the hands of criminals.

19. Meanwhile, protecting citizens will always be at the heart of our approach, including prioritising support for those who have been a victim of identity fraud. We endeavour to respond to referrals or enquiries of potential identity fraud within a week and where we find instances of identity fraud, we follow the Victims Code[footnote 5]; treat them with dignity and compassion; keep them informed; respect their privacy; comply with data protection; and use all of our powers to take the relevant action to correct the position of the individual affected.

20. The public also play a vital role. Suspicious activity can be referred to our counter-fraud team online or via post. We also have the National Benefit Fraud Hotline on 0800 854 440 for members of the public to be able to report suspicions. Where an allegation is made by the public we will look into it further to take appropriate action.

The nature and scale of the challenge we face today

21. Welfare transactions last year totalled £258.2 billion[footnote 6] – 22.5% of all UK government spending. This makes the welfare system a target for deliberate fraud by both organised crime groups and opportunistic individuals. With the complexity of the operations we run, we also recognise that both claimants and DWP staff can also make mistakes that can lead to payments being made in error.

22. Last year, there was an estimated £6.3 billion of welfare fraud, up from £2.8 billion from the year before. Together with £2.1 billion of error, the combined loss as a result of fraud and error was £8.4 billion or 3.9% of benefit expenditure[footnote 7].

23. Through our analysis we know there are five key areas that make up most of this loss. This plan sets out where we are building our defences over and above business-as-usual activity already in train to combat fraud and error.

- Misrepresenting earnings including self-employed earnings. Earnings is the highest loss area for fraud and error, totalling £1.9 billion in 2020/21 in Universal Credit. This is in part a result of the significant increase in the proportion of self-employed claimants from 5.4% of the Universal Credit caseload in February 2020 to 15.4% in July 2020. Greater use of data will help us corroborate income and allow us to make the right payment. We are already doing this for individuals who pay tax through the PAYE system, for whom we get a Real Time Information feed from HMRC to assess their earnings, rather than relying on self-reporting.

- Failing to declare or under-declaring capital. Equating to a £0.9 billion loss in 2020/21 in Universal Credit, this can occur at the start of a claim when claimants fail to declare savings or investments or during the life of the claim when they fail to notify a change in circumstance, such as inheriting a pot of money that may impact on capital rules[footnote 8]. The majority of this capital is held in high street banks, followed by online banks and property. This is why we plan to boost DWP’s powers to obtain information from third parties when parliamentary time allows.

- Failing to declare a partner contributing to the household. The third largest source of fraud loss in Universal Credit, with £0.8 billion lost in 2020/21.

- Incorrect reporting of housing costs. Leading to a £0.5 billion loss in Universal Credit in 2020/21, this mainly occurs where a person has no rental liability, an incorrect rental amount has been declared or where a person is not residing at the address given. To counter this, we now require claimants to upload evidence of their rent and residency at the property.

- Failing to declare moving abroad or dishonestly applying for benefits whilst abroad. There has been an increase in abroad fraud; we estimate around £0.2 billion was lost to this in 2020/21 in Universal Credit.

24. These frauds are perpetrated both by opportunists and by serious criminals. We have seen organised crime groups stealing people’s identities to commit welfare fraud and, in some cases, welfare fraud has been linked to other organised crime, such as modern slavery and trafficking. In other cases, instruction manuals for fraud have been shared across social media such as providing a step-by-step guide on how to make fraudulent claims.

25. While fraud makes up the majority of our losses, we understand that navigating the welfare system can be complex and we want to support claimants to provide the right information at the right time. Claimant error occurs where someone does not intend to commit fraud, but nonetheless they do not submit accurate or complete information, or they do not report a change in their circumstances which may have an impact on their benefit entitlement. This accounted for 0.6% of all benefit spend in 2020/21. There are times when DWP can also make mistakes that lead to error, for instance where benefit has been paid incorrectly due to a delay or an incorrect assessment by the department. This accounted for 0.4% of all benefit spend in 2020/21.

26. These levels of error remained consistent during the pandemic and we continue to put in place interventions to minimise all types of error through modernising and transforming our services to bring automation to the fore and ensure they are simpler. This will make it easier for claimants and frontline officials to get things right the first time, preventing incorrect payments.

Our plan to fight fraud

27. Fraud is unacceptable. We are committed to bolstering our defences to drive down fraud and error; staying ahead of the fraudsters and rooting out error that has entered our systems. We will continue to do this through our underpinning principles to prevent, detect and deter. However, as threats evolve, so must our response. We are making a step change to match the scale of the challenge.

28. This plan sets out our commitment and determination to reducing and minimising the ongoing risk of fraud and error. We are focusing on three fronts:

- Investing in DWP’s frontline counter-fraud professionals and data analytics

- Creating new legal powers to investigate potential fraud and punish fraudsters, subject to parliamentary time

- Bringing together the full force of public and private sectors to keep one step ahead

1. Investing in DWP’s frontline counter-fraud professionals and data analytics

29. DWP has a well-established and wide-ranging counter-fraud function. Our Work Coaches, case managers and service centre colleagues are our primary claimant facing roles and are the gateway to claimants being paid the right amount. They are central to spotting when suspicious activity arises and can act swiftly using interventions such as proactively contacting the claimant to check their circumstances, correcting a claim when it is incorrect or referring onto investigation teams. If a Work Coach suspects that fraud has been committed, we encourage them to make a fraud referral. This can lead to:

- Compliance investigation. We will suspend the claim if the claimant fails to fully comply with the process or discloses information that affects entitlement or level of award.

- Fraud investigation. We will suspend the claim when there is strong evidence that puts entitlement in serious doubt.

30. We also have Economic, Serious and Organised Crime officers that disrupt large scale and sophisticated attacks and tirelessly pursue the perpetrators to secure prosecution. Our Integrated Risk and Intelligence Service use data and analytics to identify high risk claims that require intervention. Our Enhanced Checking Service and Disrupt team of over 600 fraud specialists, look into suspicious cases referred to them by front-line colleagues.

31. Figure 1 illustrates how teams across the department work together to fight fraud.

Figure 1: Fighting fraud in the welfare system is a whole departmental effort

32. We are strengthening our frontline defences, including through a 75% (£613.0 million) uplift in our funding taking it to £1.4 billion over the next three years. We are investing this in boosting our counter-fraud teams and better use of data and analytics.

Our counter-fraud teams

33. To boost our counter-fraud efforts we will:

- Put in place an additional 1,400 staff across our counter-fraud teams. This will enable us to conduct more compliance interviews, full-blown investigations, enhanced checking of high-risk claims before they enter payment, and disrupt and drive out more criminal activity from serious and organised crime.

- Create a new, dedicated 2,000 strong team to deliver targeted case reviews of existing Universal Credit claims. This new team will review the entitlements and circumstances of Universal Credit cases that are at risk of being incorrect, including suspicious cases which entered our system during the height of the pandemic. During the pandemic, once we had made sure we were able to support everyone who needed it, we undertook retrospective action to reinstate missed checks relating to housing, children, and identity in around 900,000 of the riskiest claims. We are building on this by conducting a more comprehensive and detailed review of all the major drivers of fraud and error across a wider range of cases and we expect to review over 2 million cases over the next 5 years. The review will also generate intelligence on new and emerging ways fraud is entering the welfare system which we will use to further drive out fraud. This review is expected to stop around £2 billion of losses due to fraud and error over the next five years.

Better use of data to detect, correct and root out fraud

34. Effective use of data and intelligence helps our professionals do their job, from using online identity checks to accessing real time information, to specialist data-matching and other analytics. For example, our Integrated Risk and Intelligence Service are experts in monitoring risks and using data matching and analytical expertise to help identify fraudulent activity. This digital evidence is critical to help our trained professionals make the right decisions on a case-by-case basis.

35. As well as increasing the numbers of our staff, we are investing £145 million over three years on a package to further enhance data, analytics and investigative techniques to boost our capabilities to prevent and detect fraudulent attacks.

36. We will bolster our Enhanced Checking Service and Disrupt team to prevent losses by intervening in high-risk cases before payments have been issued. It will also enable our Economic, Serious and Organised Crime officers to use integrated data analysis to disrupt emerging threats and carry out complex investigations to bring criminals to justice through the prosecuting authorities, with additional cybercriminal analysts available to respond to threats of social media and internet-enabled fraud. We will ensure we build in appropriate checks and balances to ensure data sharing is lawful, with any final decision on a claim always resting with our expert team. This package is expected to stop fraud of £1.5 billion over the next five years.

2. Creating new legal powers to investigate potential fraud and punish fraudsters, subject to parliamentary time

37. DWP professionals operate under a legislative framework in their approach to fighting fraud, including data-sharing agreements, investigation powers for counter-fraud officers and a penalties system. The key primary powers we have to gather information have not been substantially updated in 20 years and our primary power to penalise fraudsters was last updated 10 years ago. They do not fully reflect the newer challenges we see today.

38. When parliamentary time allows, we plan to modernise and strengthen our legislative framework to ensure it gives those fighting fraud the tools they need and so that it stands up to future fraud challenges. To do this, we will:

- Introduce powers to boost access to third party data

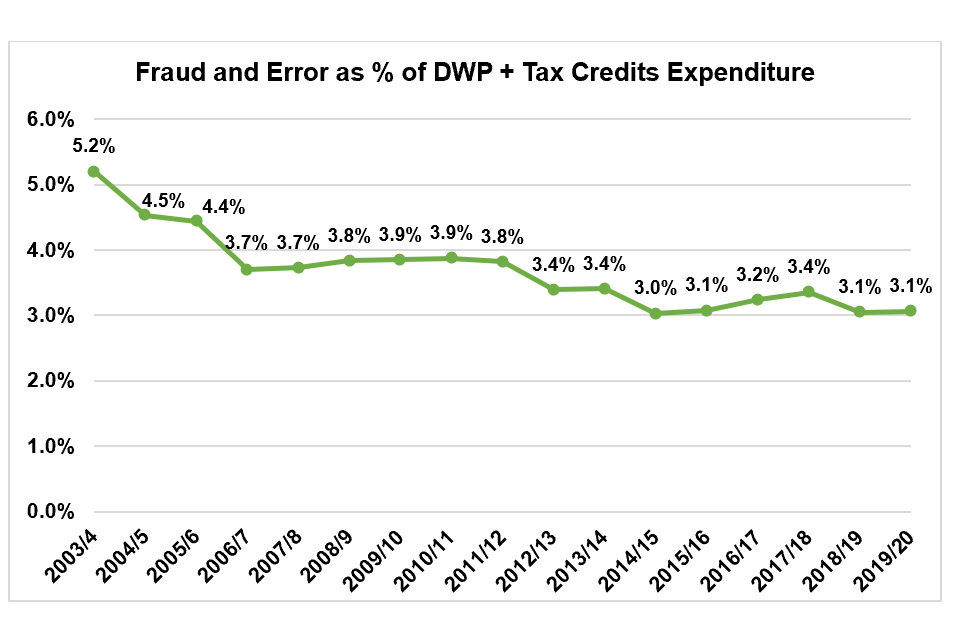

- Modernise our information-gathering powers

- Give DWP investigating officers the power to make arrests and conduct search and seizures

- Introduce a new civil penalty to make more fraudsters pay for their crime

Boost access to third party data

39. Better access to data held by third parties, in particular banks, would be hugely beneficial in identifying fraud and error in the welfare system, especially in detecting undeclared capital in claims, the second highest type of welfare fraud. In Universal Credit alone, this type of fraud was estimated to be £0.9 billion in 2020-21. It would also help us to check if someone is fraudulently claiming benefits from abroad.

Current system

40. Third parties are restricted in the support they can provide us to fight fraud. Current powers mean we can only request information from third parties such as banks on an individual basis, where we already have a suspicion of fraud. We need to submit a request that can identify a specific individual by name or description (for instance, account number, sort code or address) to a bank so they can check that individual’s capital holdings or whether they show signs of living abroad. This cannot be done swiftly at scale, and by the point of identification of an individual who we want to verify, it is likely that benefits may have already been being acquired fraudulently for some time. This hinders our ability to proactively identify fraud such as capital and abroad fraud that may be unknown to us but visible in third party data.

New powers

41. We will legislate, when parliamentary time allows, for powers to require the transfer of data from third parties to enable the department to more proactively identify potential fraud, such as where claimants might have savings above the capital limit. We want to focus the initial use of this power with banks, where we could have the greatest initial impact. Almost all benefit payments go into current accounts and around 90% of capital fraud and error is identified in high street or online accounts. A small test has been run with a bank to assess the potential of using a feed of banking data to identify possible capital and abroad fraud and error, with very encouraging results.

Proof of Concept

In 2017, we ran a small-scale Proof of Concept with a bank to test the potential use of banking data to identify possible capital and abroad fraud and error across a range of means-tested legacy benefits. The bank identified accounts receiving specified types of benefit payments and matching a risk-criteria provided by DWP, for example accounts receiving a means-tested benefit having savings over the capital limits; or accounts receiving a means-tested benefit but being accessed abroad for over 4 weeks in a row. Based on the criteria provided, a sample of 549 matches were generated for DWP to review, the majority of which had capital above the respective benefit threshold. From the cases received, a quick triage identified that around half were deemed suitable for investigation. Action was needed to remedy either fraud or error in 62% of cases that were investigated. The majority of these outcomes were a correction of the individual’s benefit payment, with a small number of prosecutions and administrative penalties.

Process and checks

42. We believe this measure is necessary and proportionate to protect taxpayers’ money and prevent crime. We recognise that we must balance this with people’s right to privacy and we will therefore ensure the power is appropriate and no more than necessary to address the problem. This will be achieved through the design of the power and ensuring the right checks are in place.

43. We will continue to engage with the finance industry to ensure the specific delivery aspects of this power are proportionate and appropriate safeguards are in place. We want to minimise any additional burdens this new power may create. As our intention is to focus initially on banks, we will work with the banking sector as we develop the details of this proposal to ensure the processes for requiring the data are as effective, simple and secure as possible. We will work closely with banks and any other relevant third party data holders to ensure the right data is transferred, received, and stored securely.

44. Case studies showing how the new power could work:

Universal Credit Capital Rule Applied – Fraud

Hypothetical scenario

Issue: A bank data match, obtained using the new Third Party Data Gathering measure, shows Claimant A’s bank account balance as £43,000. People with savings or capital of over £16,000 are not eligible for Universal Credit.

Action taken: DWP staff look on the Universal Credit system and identify that no savings have ever been declared. They refer the case for investigation.

The investigator uses existing powers to obtain detailed bank statements. These show the account balance has been fluctuating, with a substantial number of payments in and out of the account, consistently above capital limits and at times as high as £150,000. Claimant A attends an interview under caution[footnote 9] where they admit to running a business and offer no justification for not reporting this to DWP.

Outcome: Total overpayment of £28,000 detected. Case passed to Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) for prosecution. Universal Credit claim closed and recovery of overpayment commenced. Loss of Benefit notification is issued. Under DWP’s existing powers, this type of fraud may not have been discovered as proactively.

Universal Credit Capital Rule Applied – Disregard

Hypothetical scenario

Issue: A bank data match, obtained using the new Third Party Data Gathering measure, shows Claimant B has a total balance of £18,000 in their benefit receiving and connected accounts. As above, those with savings or capital of over £16,000 are not eligible for Universal Credit unless a disregard applies.

Action taken: DWP staff look on the Universal Credit system and see that the capital has been declared and is subject to a disregard, as it was awarded as a personal injury compensation to the claimant and is held in a trust. The amount is therefore not taken into account for the claimant’s capital calculation.

Outcome: No further action taken.

Modernising our information-gathering powers

Current system

45. In the main, our information-gathering powers are over 20 years old. The passage of time has exposed the rigidity and limitations of these powers. Whilst innovative for their time, and having served us well since their inception, they are no longer flexible enough to investigate many of the modern types of fraud we see today, let alone be future-proofed for the fraud of the future.

New powers

46. To further support our investigating teams, when parliamentary time allows, we plan to modernise the current information-gathering powers in three ways:

Widening the range of organisations from which we can obtain information

47. DWP can only seek information from certain named organisations as set out in legislation, such as financial institutions, childcare providers, utility companies, landlords and credit reference providers[footnote 10]. We will remove this restriction so we can widen this list and allow us to require any information holder that we believe could hold information to prove or disprove a fraud allegation, to provide that information to us. As currently, we would ensure that no one will be required to provide information that may incriminate themselves or their spouse or is subject to legal privilege. Careful consideration will also be given as to whether any information holder or information type should be exempt with appropriate checks in place.

Enabling access to information as soon as suspicion arises

48. Our information-gathering powers, set out in the Social Security Administration Act 1992, can only be used by a specially trained and authorised DWP officer when the information being requested is in support of an on-going criminal investigation[footnote 11]. This can be costly and take many months. By having the powers to gather information earlier, we will have greater ability and opportunity to look into fraud allegations without having to first commence criminal investigations when another route may be more appropriate.

Extending information-gathering powers to all DWP payments

49. Current information gathering powers only apply to allegations of fraud in some benefit payments but not others, such as grants. By extending to all DWP payments, investigators will be able to get the information they need, regardless of what type of payment it is.

50. In modernising these powers, we will minimise any additional burdens they may place on information providers and ensure they are not disproportionately onerous on any single information holder.

Process and checks

51. In obtaining a person’s information we have a responsibility to protect that information and to ensure that the powers are only used for the purposes for which they are intended. We already expect staff to maintain the security and confidentiality of all information they receive. We would seek to take civil or criminal proceedings, as well as disciplinary action, against anyone who fails to uphold the standards required. We recognise the need to strike a balance between the data being requested, the information holders themselves and our duty to protect public funds from misuse.

Information Gathering Reforms

Hypothetical scenario

Issue: Claimant is in receipt of Universal Credit and states they are not working. An allegation is received stating the subject is working as a self-employed personal trainer at a gym and has investments that are undeclared. The suspect is not self-reporting any income, capital investments or expenditure.

Action taken: DWP officers obtain evidence of the claimant’s payments to the gym for rental space, details of their clients and hours of attendance. It is also discovered that the claimant promotes his personal training in newspapers and trade magazines. DWP officers obtain details of the insurance requirements placed on the suspect. Using the new powers, DWP officers are able to obtain evidence from the newspapers and the magazines with details of who placed the adverts, payment arrangements and copies of the adverts. It is also possible for DWP officers to obtain evidence from the investment management company and it is discovered that the claimant has invested £20,000 into a scheme.

Outcome: All of the organisations are required by law to provide information to DWP. This was put to the suspect at an interview under caution, which helped to refute the suspect’s position that they were not working and in fact had capital in excess of £20,000. The case was prepared for referral to the CPS for proceedings. Under DWP’s existing powers, the evidence to identify and prosecute this fraud could not have all been obtained through a clear single statutory gateway.

Giving DWP investigating officers the power to make arrests and conduct search and seizures

Current system

52. DWP currently has significantly fewer powers than other departments and public bodies tasked with investigating economic crime. Unlike DWP, who have to rely heavily on police availability and prioritisation, HMRC and the Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority (GLAA) have powers that allow them to execute the power to arrest and conduct search and seizure regarding revenue offences or labour market abuses. The powers below will bring DWP into line with these two bodies.

New powers

53. To enable us to investigate and disrupt serious and organised fraud activity more decisively and quickly, we plan to create new powers so our officers will be able to undertake arrests and apply to search and seize evidence in criminal investigations, when parliamentary time allows. This will enable them to act in a timely fashion, without always having to rely on police resources.

54. Investigators would be required to make the same decisions and comply with the requirements as the police currently do, ensuring that action taken is in accordance with the law.

Process and checks

55. It is important we deploy these powers in an appropriate way. The primary purpose of the powers would be targeted towards serious and organised offences and cases where our specialist and highly trained staff have a strong reasonable belief that an indictable offence has been committed. Therefore, arrest may be possible, and or search and seizure action, to obtain materials in a property which would add substantial value to the investigation.

56. Ensuring proper regulation and oversight of these new powers is critical and we will continue to work with stakeholders to ascertain the right oversight arrangements.

Powers of Arrest and Search and Seizure

Hypothetical scenario

Issue: It is suspected that Universal Credit claims have been made using false identity documents amounting to £270,000. Initial enquiries were conducted as part of the investigation, so there are sufficient grounds to consider the arrest of the suspects.

Action taken: DWP can use the new power of arrest and apply to the court directly for a warrant to undertake a search and seizure for evidence. The arrest is authorised by the Senior Investigation Officer and a successful application is made to the Court for a warrant to search and seize. The suspects are arrested by DWP officers and taken to the police station for processing and consideration of detention by the police. DWP conducts interviews under caution with the suspects. DWP seizes fraudulent items that were found during a search of the suspects home addresses, including mobile phones used to provide phone numbers for false claims and suspected stolen identity documents. A warning and notice is served for the passcodes to the digital devices to preserve evidence. DWP controls evidence and conducts digital forensics.

Outcome: Suspects are arrested in a single operation at the right time, ensuring and preserving all the evidence. The speed of the operation is timely and evidence seized is much more targeted with the new powers. The cases are prepared for submission to the prosecuting body.

Making sure fraudsters pay for their crime

Current system

57. For those who do commit an offence, we have a penalties system in place that provides a range of options to ensure a proportionate punishment is handed out, based on individual circumstances. These range from a flat rate penalty for giving incorrect information through to criminal prosecution for the most serious cases.

The seven types of penalty in the current system

| Type of fraud | Penalty |

|---|---|

| For claimant error | A £50 fixed penalty (known as a Civil Penalty) where a claimant has failed to report a change of circumstances or given incorrect information, and this is deemed not to be deliberate or fraudulent. |

| For attempted fraud | This is a fixed penalty of £350. for cases where attempts to defraud have been established but it has not got to the stage where actual monies have been wrongly acquired. |

| For fraud | A financial penalty for fraud (known as an Administrative Penalty) that can be offered as an alternative to prosecution. If the penalty is not accepted by the claimant then the case would ordinarily proceed to court. To administer this penalty a full criminal standard investigation is required to have taken place and sufficient evidence to enable it to proceed to court if needed. If the penalty is chosen, the level is based on 50% of the total overpayment with the penalty value having a lower limit of £350 and an upper limit of £5000. |

| For fraud (employer collusion) | Where an employer has been found to have colluded in fraud, a fine can be applied to that employer as an alternative to prosecution ranging from £1000 to £5000. |

| Prosecution for fraud | The most serious cases of fraud, usually where an overpayment has exceeded £5000, or where an Administrative Penalty has been refused, are taken to court for criminal prosecution and where a guilty verdict is reached, sentencing guidelines set out the consequences ranging from conditional discharge to imprisonment. |

| Administrative caution | Whilst rarely used, the CPS can choose to apply a caution as an alternative to prosecution. |

| Loss of benefit | This can be used as an added financial penalty in fraud cases as a reduction in benefit where a conviction has been secured, or an Administrative Penalty accepted, with the length of time extended if there is more than one conviction. |

58. This system has worked well, but it was last updated 10 years ago, and loopholes have emerged which means some fraudsters do not face an appropriate and timely consequence. In 2019/20, we levied a penalty on 76% of claimants we confirmed had committed fraud or claimant error. This means that 24% had no penalty applied due to a number of reasons including evidence not meeting the standards required for prosecution; claimant circumstances or because pursuit of a case was not deemed in the public interest[footnote 12].

59. We want to build on our current approach, keeping what works, but expanding the system to ensure it continues to provide a comprehensive and proportionate response. We want to ensure that fewer people escape punishment when they have committed wrongdoing, and that the consequence reflects the cost to the taxpayers.

60. Too many people are escaping punishment for wrongdoing as all cases must be investigated to the same criminal standard, as if they were going to prosecution, whatever their seriousness. That means, even where there is clear, strong evidence, large numbers of cases do not meet the very exacting threshold for criminal conviction and the consequence is that no sanction is given.

61. Other government departments, such as HMRC and the Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), have additional options available to them that enable them to take action where there is strong evidence without having to reach the burden of proof required for a criminal prosecution.

New powers

Introducing a new civil penalty

62. When parliamentary time allows, we plan to bolster the penalty regime by introducing a new type of civil penalty for cases of fraud. This will be a percentage of the overpayment incurred. This approach of dealing with fraud by civil penalties follows that taken by other government departments such as HMRC. Unlike the current administrative penalty, the new penalty will not be offered to the claimant as an alternative to prosecution but will be imposed on the claimant for those cases that we do not prosecute. The penalty will be based on meeting a civil burden of proof, sitting below criminal fraud, but above error. It will also be available to apply in cases that have been fully investigated to a criminal standard, but for whatever reason, have not made it to the courts.

63. This will help DWP and the CPS to focus on taking the most serious cases to prosecution while also ensuring that other fraudulent cases can receive a swift and effective sanction in its place.

Process and checks

64. We plan to introduce powers so this new civil penalty can be imposed by our counter-fraud staff in appropriate circumstances. For example, where an investigation establishes fraud has taken place with the fraudster receiving money they are not entitled to, and the new burden of proof for a civil penalty has been met.

65. We will ensure there is a clear route of recourse with the right to challenge the decision that money has been received fraudulently and/or the issue of the penalty. We will also ensure there is a clear appeal process and will work with HM and Tribunals Service (HMCTS) to assess any potential increase in appeals.

66. We also need to balance our penalty approach with a different approach to those who do not deliberately set out to gain money to which they are not entitled but have provided incorrect information leading to an overpayment.

67. We will continue to finalise the details of these changes working with expert stakeholders including those in the criminal justice system. We want to be able to ensure that all cases of wrongdoing have appropriate consequences, and for cases that are not sent for prosecution, the civil penalty is proportionate and fair to reflect the level of wrongdoing.

Expanding the scope of the penalties system

68. We will also expand the scope of the penalties system so it goes beyond people in receipt of benefits and covers those, both individuals and organisations, who receive other types of taxpayer funds from DWP or who seek to defraud the system. For example, this could include people promoting benefit fraud schemes online, creators and sellers of fraud toolkits on social media or someone supplying fake ID. This is difficult under existing legislation for a number of reasons. Current social security legislation generally assumes that welfare fraud can be recouped from future benefit payments, whereas this is not the case with third parties who do not receive benefit payments in the first place. Additionally, some emerging types of welfare fraud simply did not exist when the legislation was originally designed, so we need to be able to respond to these new types of attack.

69. Although we do have recourse to legislation through the Fraud Act 2006[footnote 13], the burden of proof to prosecute using this often makes it impractical, unless it is for high value cases. By introducing a new civil offence, similar to those used by other government departments such as HMRC and DEFRA, we will be able to respond more rapidly and in a more cost-effective way than we are currently able, especially for the medium and low value cases.

70. We will also ensure the new penalties system applies to all types of payment, such as Universal Credit advances and grants, which are also targeted by fraudsters and may result in an overpayment.

Fraud Detected on Kickstart grant

Hypothetical scenario

Issue: An employer is suspected to have colluded with a number of friends by telling DWP he is employing them in order to receive Kickstart grants. But there is no work, and they are not being employed by him. Sufficient evidence exists to prosecute the employer. One of the false ‘employees’ had been paid a lump sum by the employer for his identity to be used in this way. The fraud was discovered early and only £1,860 was paid out by DWP.

Action taken: Although the case met the burden of proof required to prosecute the employer, it did not do so for the ‘employee’. The ‘employee’ did meet the criteria of the new civil penalty and so a financial penalty was able to be applied more quickly.

Outcome: The new civil penalty is applied, and it is calculated as a percentage of the overpayment value of £1,860. This penalty is to be paid on top of the requirement on the individual to repay the £1,860 they fraudulently received. By contrast, with DWP’s current powers, the only current available option is potential prosecution. If the case is not taken forward by the CPS, there is no further action we can take and the fraud goes unpunished.

3. Bringing together the full force of public and private sectors to keep one step ahead

71. Technological advances give fraudsters new opportunities to find ways to attack. We are seeing fraud manuals being shared across social media and organised groups stealing identities to commit welfare fraud and, in some cases, using those proceeds to fund other illegal activities. To make sure we can stay ahead of the fraudsters, we need to bring together the full force of government and the expertise of the private sector.

72. We are already taking steps to work more closely with other government departments. For instance, we are exploring the opportunities that HMRCs reforms through Making Tax Digital[footnote 14] (MTD) and the Timely Payments Initiatives[footnote 15] provide for us to increase the timeliness of the data we receive on self-employed earnings. This could help us reduce levels of fraud and error in payments to self-employed claimants.

73. Similarly, we are working more closely with technology providers. Since July 2019, we have referred approximately 1,500 social media accounts to providers for removal.

74. Our Economic, Serious and Organised Crime officers also work with a wide range of operational partners from the law-enforcement community to investigate concerns relating to modern slavery where there is a potential DWP benefit interest. This could include deployment of tactical operational support or remote real-time support. For example, the DWP’s National Disclosure Unit makes approximately 110,000 disclosures to Law Enforcement Agencies per annum and receives approximately 360 requests each working day.

75. As these threats evolve, so must our response. To do this, we need to continuously improve internally, working across government and the private sector to think creatively about shared challenges and by testing new innovations.

76. These are two examples of where we are working across government and with the private sector to tackle new fraud risks:

Crypto assets

Issue: Crypto assets are a growing type of digital financial asset and investment and are often difficult to detect when hidden. They are a form of investment and capital rules should be applicable as they are to a second property or company shares.

The decentralised and anonymous nature of the crypto asset market means that there is both a lack of protection, should something go wrong, but also a lack of oversight and transparency. We therefore rely on the honesty and integrity of our claimants to tell us about their crypto assets and the lack of transparency makes these assets attractive for those who wish to cheat the system.

Action taken: As well as making clear how we will treat crypto assets in our benefit processes, we are building and enhancing partnerships across government (with the Home Office, HMRC, and others) and with industry experts to ensure we have the powers and sanctions to investigate and tackle fraud facilitated through the use of crypto assets in the welfare system and public sector more widely. This includes highlighting and sharing best practice when it comes to investigating crypto assets.

Social Media

Issue: Information on how to defraud public services including the welfare system is being shared and sold online by criminals on social media. The behaviours can range from promoting fraudulent approaches, scamming claimants, as well as selling how-to manuals. There was a surge in the promotion of ways to defraud DWP on social media when coronavirus easements were put in place due to the streamlined application process, and we now see this threat persisting.

Action taken: Digital and real-world fraud are two sides of the same coin. We must tackle both if we are to be effective at addressing fraud in the round.

To address this, the government introduced the Online Safety Bill to Parliament on 17 March. Through the Bill, companies will need to take robust action to tackle fraud, including these types of scams posted on social media. Companies will have to take steps to identify, remove and limit people’s exposure to this content.

High risk and high reach companies, such as the largest social media platforms, as well as search engines, will also need to prevent paid-for adverts for fraud appearing on their services. This will ensure that people using the largest platforms, and where there is greatest risk of harm, are protected from scams and ensure these services do not profit from illegal activity.

We are also working with HMRC and across wider government to share best practice and build upon the ways in which we can target, monitor and bring the full force of the law against the individuals who are behind offending posts and are promoting defrauding the welfare system and wider public sector.

77. We will work hand-in-hand with the new Public Sector Fraud Authority announced at the Spring Statement. It, and the accompanying investment of £48.8 million over three years, will enable government and enforcement agencies to step up their efforts to reduce fraud and error, bring fraudsters to justice, and recover millions of pounds.

78. We will also establish a new Fraud Prevention Advisory Group. This will bring together key government and external experts to collaborate on shared issues and work through new and innovative solutions, including exploring how we can source data more flexibly and proactively to fight fraud.

79. We are establishing a £30.0 million Fraud Prevention Fund, to invest in, test and trial creative, innovative and evidenced based solutions to fraud and error problems over the next three years. We will also use this to carry out research into areas such as policy development, behavioural change, digital discovery and communications.

80. Dealing with fraud and error is complex and designing it out of a system is even more so. We want to continue to develop new, better, more creative solutions; for example, by building prevention measures into our digital processes and using behavioural science. We will also find more areas to look at as we carry out the targeted case review of Universal Credit.

Conclusion

81. The plan presented in this document will help us to defend the welfare state against those who seek to illegally take advantage of it. It will allow us to dig deeper in rooting out fraud and error wherever it occurs in the welfare system and holding people to account.

82. The document sets out our renewed and wide-ranging approach across three different fronts – more investment in the frontline, a modernised and stronger set of investigation and enforcement powers, subject to parliamentary time, and a focus on working with others to stay ahead of the threat. We will work with stakeholders, such as those in the criminal justice space and banking industry to test and refine some of our proposals over the coming months and to start delivering our plan.

83. Through this plan we will continue to fight fraud against the welfare state, building on our long-standing and successful principles to prevent, detect and deter benefit fraud.

Annex A: Fraud and error in the welfare system

84. We have built a strong evidence base regarding fraud and error in the welfare system. This supports the development of policies[footnote 16] and helps us understand long-term trends and behaviours. This annex sets out the historic levels of fraud and error in the welfare system[footnote 17].

85. Chart 1 demonstrates that prior to the pandemic, fraud and error as a percentage of DWP and Tax Credits expenditure reduced from 5.2% in 2003/4 to 3.1% in 2019/20[footnote 18].

Chart 1: Fraud and, Error as percentage of DWP + Tax Credits Expenditure

| Year | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|

| 2003/4 | 5.2% |

| 2004/5 | 4.5% |

| 2005/6 | 4.4% |

| 2006/7 | 3.7% |

| 2007/8 | 3.7% |

| 2008/9 | 3.8% |

| 2009/10 | 3.9% |

| 2010/11 | 3.9% |

| 2011/12 | 3.8% |

| 2012/13 | 3.4% |

| 2013/14 | 3.4% |

| 2014/15 | 3.0% |

| 2015/16 | 3.1% |

| 2016/17 | 3.2% |

| 2017/18 | 3.4% |

| 2018/19 | 3.1% |

| 2019/20 | 3.1% |

Source: Calculated from published DWP and HMRC expenditure and fraud and error statistics[footnote 19].

86. Prior to the pandemic, the total level of losses due to overpaid welfare including DWP administered benefits and Tax Credits, was falling (Chart 1). The fall over the last decade is a credit to the digital design of Universal Credit (and the increasing digitisation of wider benefits) and how we use data more effectively. This is despite a backdrop of fraud in society increasing over this period. Central to this success has been the role of Pay As You Earn (PAYE) Real Time Information reporting from HMRC. We have estimated, based on historic patterns of earnings-related fraud and error in the statistics, that for 2020/21, without the Real Time Information feed being available, PAYE fraud and error would have amounted to 2.9% of Universal Credit expenditure. However, as a result of the PAYE RTI feed, PAYE fraud was only 0.1% of the total fraud and error expenditure in Universal Credit.

87. Universal Credit is replacing Tax Credits as well as DWP legacy benefits. As Universal Credit expands to take in the Tax Credits caseload, we would expect that the behaviours that occur within the Tax Credits system will occur within Universal Credit, except where the design of Universal Credit prevents them. Tax Credits entitlement is only finalised at the end of the year. That means there are two types of overpayments within Tax Credits:

- Overpayments: Where the finalised entitlement calculated at year end was correct, but the claimant received more than that amount of entitlement during the year. Since the entitlement was correctly calculated at the end of the year, this is not considered as error or fraud.

- Error or fraud: Where the finalised entitlement was incorrect.

88. For Tax Credits to be classified as fraud, a caseworker needs to have found evidence that the claimant deliberately set out to misrepresent their circumstances to get money to which they are not entitled (for example claiming for a child that does not exist). Tax Credits error covers instances where there is no evidence of the claimant deliberately trying to deceive HMRC. It covers a range of situations, including cases where a claimant inadvertently over-claims because they simply provided HMRC with the wrong information. For the tax year 2019/20, error made up 95% of the total value of error and fraud overpaid to claimants, with the remaining 5% coming from fraudulent activity[footnote 17].

89. In Universal Credit, fraud and error occurs when the claimant receives benefit at the end of the month that does not correctly reflect their circumstances that month. Including Tax Credit overpayments (in addition to Tax Credit error and fraud) when comparing pre-Universal Credit times to current times provides a more accurate comparison of the rate of incorrect payments across welfare benefits.

-

The PAYE or ‘pay as you earn’ system holds information on the wages and salaries paid every month to employed. The PAYE Real Time Information feed shared between HMRC and DWP enables HMRC to pass earnings data to DWP so that Universal Credit claims can be assessed based on accurate employee income amounts. ↩

-

This fraud and error figure includes tax credits overpayments. Tax Credit overpayments are a design feature of the tax credits regime, as it is an annualised award derived from the previous year’s income. An award of tax credits is always provisional until entitlement is calculated and finalised at the end of the tax year. This naturally leads to overpayments. Consequently, overpayments are not included in HMRC’s assessment of error and fraud. Instead, HMRC’s definition of error and fraud is where the finalised entitlement was incorrect (i.e., where incorrect information is given at finalisation). As Universal Credit entitlement is calculated monthly based on a claimant’s circumstances in that month, fraud and error in Universal Credit is defined as any instance where the claimant receives benefit at the end of the month that does not correctly reflect their circumstances that month. Therefore, overpayments of Universal Credit are always included in DWP’s error and fraud figures. ↩

-

Available at Crime in England and Wales – Office for National Statistics – (ons.gov.uk). ↩

-

Available at Cross-Government Fraud Landscape Bulletin 2019-20 – (www.gov.uk). ↩

-

Available in The Code of Practice for Victims of Crime in England and Wales and supporting public information materials. ↩

-

This covers all DWP benefits and Tax Credits. Available at Economic and fiscal outlook – March 2022 – Office for Budget Responsibility (obr.uk). ↩

-

Available in Fraud and error in the benefit system for financial year ending 2021. ↩

-

Means-tested benefits are awarded based on your income and how much capital you have. This ensures support goes to those who need it most. Capital limits are the maximum amount of savings a single, or joint, claimant can have to be eligible to claim a benefit. For example, if a Universal Credit claimant has more than £16,000 in capital or savings, they are not eligible. ↩

-

An interview under caution is a formal interview with the suspects in an investigation ↩

-

Available at Social Security Administration Act 1992 – (legislation.gov.uk). ↩

-

The criminal investigation and evidence gathering process commences when information is initially received suggesting an offence may have been committed and a decision is taken to act on the referral. The aim is to gather evidence which proves, or disproves, that a criminal offence has been committed against the DWP or Local Authority and who committed that offence. The outcome of the criminal investigation may be that no offence has been committed or it was committed by someone other than the person(s) named in the allegation or identified during the investigation. ↩

-

Internal analysis of DWP Management Information. Analysis excludes cases processed by DWP Interventions, as such cases will not typically be in-scope of the existing penalty regime. For example, Claimant Errors classified as Small Over Payments (current threshold set at £65) will not be subject to a £50 Civil Penalty. ↩

-

Available at Fraud Act 2006 (legislation.gov.uk). ↩

-

Available at Overview of Making Tax Digital – (www.gov.uk). ↩

-

Available at Timely payment: summary of responses – (www.gov.uk). ↩

-

Formal impact assessments, including the equality impacts of final policy proposals will be conducted, informed by further stakeholder engagement, before we bring forward legislation. ↩

-

These fraud and error figure includes tax credits overpayments. Tax Credit overpayments are a design feature of the tax credits regime, as it is an annualised award derived from the previous year’s income. An award of tax credits is always provisional until entitlement is calculated and finalised at the end of the tax year. This naturally leads to overpayments. Consequently, overpayments are not included in HMRC’s assessment of error and fraud. Instead, HMRC’s definition of error and fraud is where the finalised entitlement was incorrect (i.e., where incorrect information is given at finalisation). As Universal Credit entitlement is calculated monthly based on a claimant’s circumstances in that month, fraud and error in Universal Credit is defined as any instance where the claimant receives benefit at the end of the month that does not correctly reflect their circumstances that month. Therefore, overpayments of Universal Credit are always included in DWP’s fraud and error figures. ↩ ↩2

-

Data is up to 2019/20, as the 2020/21 data for Tax Credits is not available yet. Chart 1 has been calculated using publicly available data – the published levels of fraud and error in DWP benefits, plus the fraud, error and overpayments that HMRC have measured in the Tax Credits system, divided by the total welfare expenditure across DWP and HMRC. ↩

-

Available at Child and Working Tax Credits error and fraud statistics, tax year 2019 to 2020 – (www.gov.uk). ↩