Financial Transaction Control Framework (HTML)

Updated 1 April 2025

1. Overview and scope of this framework

Overview

At Autumn Budget 2024, the government announced reforms to its fiscal framework. The fiscal rules include the investment rule – to reduce debt, defined as public sector net financial liabilities (PSNFL) or net financial debt, as a share of the economy. This is a comprehensive metric that captures all financial assets and liabilities on the public sector balance sheet, as defined in line with international guidance.[footnote 1]

Economic growth is the government’s central mission and well-directed public investment can catalyse private investment. A move to net financial debt recognises where equity investments or loans create financial assets corresponding to the liability incurred to finance them, providing opportunities for government to make financial investments that support growth while generating a return for the Exchequer.

Government must also invest responsibly and the move to target net financial debt is accompanied by controls on financial transactions (FTs), where the public sector acquires or sells financial assets. This framework will ensure that government’s use of FTs is fiscally sustainable and does not cause debt to rise over time.

This document builds on spending controls for managing FTs set out in Managing Public Money (MPM) and Consolidated Budgeting Guidance (CBG).[footnote 2] It does not change budgeting rules set out in CBG, but it does provide guidance on how they are applied in some cases.

The Treasury will only approve spending on FTs where robust controls are in place in line with this framework and it will review the processes of public financial institutions to ensure this.

Structure of this document

The controls set out in this framework are:

-

Guidance on when FTs are an appropriate form of policy intervention and key considerations in designing FTs (Chapter 2).

-

Delivery of new, large-scale FTs through designated public financial institutions with suitable expertise and capability (Chapter 3).

-

Measures to help manage risk and return, including an annual report on government’s financial investment portfolio to provide transparency; requirements around rate of return for FTs; and controls to manage risk of unexpected losses in downside scenarios (Chapter 4).

-

New criteria and approval process for Treasury consent of FTs and decisions on FT budget allocations (Chapter 5).

Spending control of FTs

As set out in budgeting rules and MPM, Treasury consent and budget cover is needed for departments to issue any FTs.

Treasury consent

Departments must have Treasury consent before undertaking spending on FTs or making commitments that could lead to spending on FTs. In line with other spending, Treasury consent is provided by:

-

Delegated limits, below which consent for spending on FTs is delegated to the department; or

-

Direct approval in advance, required for all FTs with an overall value above a department’s delegated limit, or for FTs which are novel, contentious, or repercussive.

Parliament must also approve spending on central government FTs via the estimates process. Budget cover for FTs is reflected in Capital Delegated Expenditure Limit (CDEL) or Capital Annually Managed Expenditure (CAME) control totals and FTs score against these budgets in line with CBG.

Departments will need appropriate legislative powers (vires) to deliver FTs where they constitute a ‘new service’, as set out in MPM.

Spending review and budget processes

Budget cover for FTs managed in DEL is allocated via regular Spending Reviews and budget cover for FTs managed in AME is forecast and reviewed at Budgets.

FTs impact departments’ capital budgets when entered (i.e., when undertaking net lending and the purchase of shares) and as they are exited (e.g., sale of shares).

FTs impact departments’ resource budgets in Resource DEL (RDEL) or Resource AME (RAME) via the returns received on assets, for example, interest received on loans. FTs also impact departments’ resource budgets through changes in asset value and recognition of losses, such as scoring allowances for expected credit losses.

As FTs have distinct fiscal treatment, they form a ringfence within CDEL and CAME budgets. Departments may not switch budget cover out of their FT ringfence without approval from the Treasury.

Enhanced controls for FTs

The government has established the following principles through the Financial Transaction Control Framework (this document). These principles support the government to invest responsibly.

Policy rationale

Government should intervene in the economy to achieve clear policy objectives such as solving market failures and delivering public services. This remains the case for FTs. Where FTs solve market failures in the provision of capital, they can generate a net return for the taxpayer; where they are used to provide subsidies, they are unlikely to do so and are more akin to conventional spending but can represent better value for money than grants.

Government will trade-off costs of FTs with other spending. If government makes investments that generate a return below its cost of borrowing, this worsens the current budget balance and net financial debt over time. The expected costs of FTs will be reflected in the OBR’s forecast and decrease other spending that government can deliver within its fiscal rules. Trading off these costs with other spending will ensure that debt as a share of the economy continues to fall over time.

Public financial institutions

Large-scale, higher risk or complex FTs and guarantees should be delivered by designated public financial institutions, absent Treasury agreement to do otherwise. UK Government Investments can advise departments in assessing riskiness and complexity of new FTs.

Risk and return

FTs should either generate a return above government’s cost of borrowing or recognise costs transparently where FTs are intentionally designed not to do so from the outset. Some losses occur in any portfolio, so rates of return should be considered at the level of portfolio of FTs, not each investment. In various cases, there can be a need to address a market failure by issuing FTs that government expects, at the outset, to be loss-making (i.e., generate a return below government’s cost of borrowing). These costs should be transparently recognised in line with departments’ financial reporting framework.

The government will publish an annual report on central government’s financial investments, delivered by UK Government Investments (UKGI). This report will use asset valuations drawn from government accounts already audited by the National Audit Office (NAO) and other relevant unaudited information. The Treasury is working with the Comptroller and Auditor General to ensure that the report builds appropriately on existing audits of asset valuations, where used. The report will provide transparency to the public and parliament on the value, risk, and performance of government’s financial assets.

New risk-based controls for FTs and guarantees will be introduced. This will be implemented via an economic capital-based approach as is already used in several public financial institutions.

Approval process

The standard information departments must provide for Treasury approval of FTs is set out in Annex E. These flow from the Green Book, with this document covering FT-specific considerations.[footnote 3]

Scope of this framework

Organisations covered

As with CBG, this framework applies to all entities classified by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) to central government, including government departments and their arm’s length bodies. It also applies to any entity designated as a public financial institution in line with Chapter 3 of this framework.

This framework does not apply to the devolved governments as their funding arrangements are set out in the Statement of Funding Policy.[footnote 4] The government is supportive of the devolved governments’ ongoing use of FTs and will continue to engage with them on any impact from the implementation of this framework.

Financial assets and instruments covered

The table below sets out the financial instruments covered by this framework. Definitions follow the National Accounts (SNA 2008 and ESA 2010) statistical frameworks, rather than International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) based definitions.[footnote 5] FTs are recognised in the National Accounts when financial assets or liabilities are exchanged between the public sector and the private sector or rest of the world.

Table 1.1 Financial assets and instruments

| Category | Definition based on the National Accounts |

|---|---|

| Loan assets | Financial instruments, which must be interest-bearing and have to be repaid at maturity. |

| Equity assets | Residual claims held on the assets of private sector corporations through shareholdings or ownership. |

| Derivative assets | Financial instruments linked to financial or non-financial assets or to an index, where the value is derived from the underlying asset or index. |

| Debt securities assets | Financial instruments like corporate bonds and bills that pay interest and have fixed dates of maturity. |

Financial instruments in partial scope

Student loans are partitioned under National Accounts guidance into a loan (i.e., an FT) component and a capital transfer component. The partition is consistent with the approach taken to other FTs in this document, as it clearly identifies the element of the student loan book that government expects to be repaid (classified as an FT) and the element that is loss-making (classified as a capital transfer).

Guarantees are only in scope of this framework in respect of the requirement for large financial instruments to be delivered by public financial institutions and their inclusion in economic capital limits for public financial institutions, set out in detail in Chapter 4. Wider policy on guarantees and insurance, including their design and approval, is covered by the separate Contingent Liability Approval Framework.[footnote 6]

Loans or equity investments within the public sector may be recognised as FTs from a departmental budgeting perspective where they are transactions with an entity outside the departmental group boundary. However, from a National Accounts perspective, transactions between two parts of the public sector will consolidate out, with no financial asset recognised. In general, they are not in scope of this framework, but where intra-public sector FTs are managed by public financial institutions, they are in scope of the controls in Chapter 3.

Financial assets and instruments not in scope

Assets treated as liquid in UK public finance statistics, such as cash and short-term deposits, are not subject to this framework.[footnote 7]

Grants or loans which require repayment only if certain conditions are met are unlikely to be recognised as financial assets in the National Accounts on issuance until they are transformed into loan or equity assets when a condition is met. They are treated as capital spending and not subject to this framework.

Departments should engage their Treasury spending team to seek guidance on the classification of specific transactions.

2. When should government use financial transactions?

Overview

This chapter sets out guidance for appraising whether an FT (an individual FT, FT programme, or use of the capacity of a public financial institution) is an appropriate tool to achieve government objectives.

It should be read as a set of FT-specific considerations that are supplementary to central guidance for appraisal of government policies, programmes, and projects set out in the Green Book.

This guidance is designed to apply to departments, public financial institutions and any other government organisation delivering an FT. As public financial institutions have been set up to be operationally independent subject to their mandate and financial framework, they will also autonomously identify, design, and deliver FTs.

What should government consider when deciding to use an FT?

Addressing market failures and ensuring additionality

As with all government interventions, the use of FTs must be underpinned by a clear rationale for intervention in line with principles set out in the Green Book, therefore supporting government objectives by delivering outcomes that maximise social value.

FTs are typically appropriate when there is a plausible route to repayment and they can be issued to a variety of beneficiaries including businesses, households, and other countries.

When appraising options for new FTs, there are some key considerations, in addition to those set out in the Green Book for any government intervention, to determine whether an FT is suitable to solve a policy challenge, set out below:

-

Role of government: most FTs will involve (i) government taking on the role of a capital investor where private sector capital markets do not allocate capital in a socially optimal way to viable projects or (ii) improve outcomes by using an FT to deliver a subsidy to address externalities and therefore change the behaviour of economic actors. Government intervention typically has a social cost from raising funds via taxation or borrowing, which needs to be factored into use of FTs.

-

Market failures: government interventions should typically focus on fixing identified market failures. This is where socially optimal outcomes are not realised by markets and can either be a complete market failure (if the market does not function at all) or a partial market failure (if the market functions but in a suboptimal way). Given FTs are an intervention that closely approximates financing available from private capital markets, there should be a clear explanation of why the private sector has not been able to offer these financial products and FTs should be designed to avoid crowding-out private sector capital. Box 2.A outlines a non-exhaustive list of market failures that can be addressed by FTs, together with some relevant examples.

Box 2.A Market failures that can be addressed by FTs

Intervening in the provision of capital

Information asymmetry: market participants can have different levels of information about projects that affect investment decisions and can lead to under-provision of finance. For example, a founding objective of the British Business Bank was to address an asymmetry of information between SMEs and providers of finance.[footnote 8]

Short-termism: investors may under-invest in longer-term projects that may ultimately deliver greater societal benefits and instead focus on shorter-term projects. For example, British Patient Capital was launched to support long-term investment in innovative firms with high growth potential.[footnote 9]

Macroeconomic instability: during an economic downturn, there can be an under-supply of credit as investors may have reduced capital or risk appetite, which means otherwise viable businesses cannot access finance. For example, the Covid-19 Bounce Back Loan Scheme provided 100% guarantees to the lending market for loans to viable firms during the pandemic.[footnote 10]

Risk-tolerance absorption: investors’ degree of insolvency risk means they have a lower risk appetite than government who can invest in projects with larger risks. For example, the National Wealth Fund makes equity investments into infrastructure projects which may carry higher levels of risk than capital markets can absorb.[footnote 11]

Market capacity constraints: investors may have reduced appetite for some investment areas, e.g., potentially due to regulatory impacts or reduced profit margins. Some investors are regulated to manage their investment portfolio, including limiting concentration of risk in certain sectors or markets. The UK Export Finance Direct Lending Facility provides loans to buyers of UK goods, allowing exports to be financed where commercial bank capacity is limited.[footnote 12]

Other Market Failures

Positive externality: some activities cause a positive spillover effect that would not be realised by an investing business, which government can support through an investment at a favourable repayment rate. For example, student loans tackle the externality of education, whereby higher education has benefits for society beyond the individual, through offering loans which would not be commercially available to reduce barriers to participation.

Negative externality: government can subsidise actions to reduce activities by individuals or organisations that cause an indirect cost borne by society, such as pollution. For example, the UKRI Innovation Loans programme has funded various R&D projects to develop new technologies for renewable power generation, supporting the reduction of carbon emissions.[footnote 13]

-

Additionality: this is when government investment leads to activity that would not occur absent intervention. For FTs, this could be unlocking a specific project that would not have been funded, at least in full or as quickly, by the private sector. More broadly, it could also include fostering development of a new or expanding market over time. At a macroeconomic level, to be additional FTs must boost capacity on the supply side of the economy over the medium-term to a greater extent than any nearer-term crowding-out effect from reduced private investment. Evidence of additionality should align with the Green Book’s principles on impact evaluation.

-

Concessionality: to minimise market distortion, concessionality (where government invests on terms more favourable than the market) should be limited to where necessary to achieve policy objectives and compliant with subsidy control legislation. This is important where government is investing in markets where there is an under (but partial) supply of private capital, or directly co-investing with private investors, because issuing concessional FTs in these cases can unintentionally crowd out private finance on a pricing basis.

-

Comparing to grants, guarantees, regulation, or tax: other types of intervention may represent better value for money than FTs. Government should trade off using grants, guarantees, regulation or tax against use of an FT or alternatively FTs may be used alongside these interventions to complement them. Any interactions with wider policy interventions should be considered when assessing the use of an FT, as financing interventions often need to be sequenced with wider policies to address market failures in a specific part of the economy.

What types of FTs exist?

Table 2.1 outlines broad categories of FT, and table 2.2 outlines other instruments that can achieve policy goals in a similar way. The instruments listed in 2.2 are not classified as FTs but may have some similar characteristics and fulfil similar policy objectives.

Table 2.1 Types of financial transaction

| Type | Summary |

|---|---|

| Commercial loans | A loan issued to a business, project, individual or household, which must be repaid at maturity and charges interest at market rates. |

| Concessional loans | A loan that charges interest below market rates. This may offer a positive return if income generated is above government’s cost of borrowing, but also could be loss-making. |

| Deferred interest loans | A loan that charges interest, but interest payments are deferred for a specified period until the loan matures to ease cashflow challenges for borrowers. |

| Direct Equity | When government provides capital through purchasing shares in a business or project in exchange for ownership. |

| Fund Investment (Equity) | When government invests equity via a fund structure, alongside private investors. A fund is a product that government owns a share of, combining a pool of investments (e.g., a mix of loans, equity, and debt securities). |

| Mezzanine finance (loan and equity) | When government provides a loan that can be converted into an equity stake if a business or project cannot repay the loan in full. |

Table 2.2 Other financial instruments

| Type | Summary |

|---|---|

| Guarantees* | When government agrees to pay all or part of a financial instrument in event of non-payment or loss of value, charging a fee. Guarantees can present a similar type of credit risk as loans. |

| Insurance or Indemnities | When government provides coverage for some of the losses of an insured party in certain circumstances. Indemnities cover the risk that an event materialises, rather than a borrower not repaying obligations. |

| Convertible grants** | A grant which converts to an equity stake or loan upon reaching pre-agreed conditions. |

*Some types of guarantees are classified as FTs (e.g., standardised guarantees where a large volume of guarantees are issued on identical terms and conditions.)

**Will be FTs when the conditions are met but will be treated as grants before that point. A conditional loan will also fall under this category.

How should government design FTs?

Once a government organisation has decided that an FT may be an appropriate intervention, it should be designed to ensure value for money. Key considerations for policy design are reflected in Annex E, which sets out standardised information that must be provided to the Treasury through the Financial Transaction checklist.

Key considerations

Counterparties and revenue stream: mapping out which counterparties are involved in a transaction will clarify its functioning. This includes who is involved in the supply or value chain that government is investing or lending in, risks to these chains, and how these risks are shared between government and the investee. For example, for a business this will include where their demand comes from and the revenue that will repay the loan or drive equity growth. For an individual or household, it includes factors like creditworthiness or earnings. (Section 1 and 3 of Annex E – the FT Checklist).

Subsidy control: government FTs will create a lower level of market distortion than grants, but they still need to comply with the Subsidy Control Act 2022, which should be considered at an early stage and resolved prior to concluding negotiations with private sector counterparties.[footnote 14] (Section 1 of Annex E – the FT Checklist).

Box 2.B Overview of Subsidy Control Rules

The subsidy control regime aims to prevent public authorities from giving financial advantages to businesses in a way that could create excessive distortions of competition. There are seven principles that should guide consideration of whether to implement a subsidy:

A - Subsidies should have a specific policy objective to remedy an identified market failure or address an equity rationale.

B - Subsidies should be proportionate to their specific policy objective and limited to what is necessary to achieve it.

C - Subsidies should bring about a change of behaviour for the beneficiary which would not happen without the subsidy.

D - Subsidies should not normally compensate for costs the beneficiary would have funded in the absence of a subsidy.

E - Subsidies should be a suitable policy instrument for the specific objective, which can’t be achieved by other, less distortive, means.

F - Subsidies should be designed to achieve their policy objective while minimising negative effects on competition and investment.

G - Subsidies’ beneficial effects should outweigh any negative effects, in particular on competition, trade and investment.

Pricing and fiscal Impact: understanding appropriate pricing of an FT will affect delivery. This should be anchored around government’s cost of borrowing, but more importantly should reflect policy goals. If an FT is bankable and seeking to crowd-in co-investment, investing ‘pari passu’ (on equal terms to the private sector) may be suitable to maximise VfM and avoid crowding out. In other cases, an FT may need to be priced below the market, or even below government’s cost of borrowing (a loss-making FT), to transfer risk to government to achieve policy objectives, subject to consideration of subsidy control. Pricing also drives fiscal impacts, which should be calculated over the lifetime of an FT. (Sections 1 and 2 of Annex E – the FT Checklist).

Exit strategy: for FT interventions, government should either clearly articulate an exit strategy at the outset to maximise returns or outline the policy rationale for holding the asset in perpetuity. For a loan, the exit will be its tenor whereas for an equity investment this will be a planned IPO or trade-sale. Interventions aiming to establish commercial viability for a new technology or sector should consider how support can be tapered over time to transfer risk from government to a new commercial sector. (Section 3 of Annex E – the FT Checklist).

Risk exposure and management: it is important to understand the level of risk that an FT exposes government to, including the types of risks (see table 3.2 for examples), the scale of losses that could be experienced in a downside scenario, and triggers for this materialising. Public financial institutions and other organisations managing large FT portfolios should have risk exposure limits in place, based on economic capital models. (Section 4 of Annex E – the FT Checklist).

Managing fraud and error risk: when government provides loans or investments, it may be exposed to risk of fraudulent claims or issuing funds to a party in error. To guard against this, it is important to define robust eligibility criteria in design of FT programmes and ensure adequate capability and processes are in place for upstream due diligence on investments and downstream recovery of erroneous payments. Departments and public financial institutions can engage the Public Sector Fraud Authority on their approach to managing fraud and error, as appropriate. (Section 4 of Annex E – the FT Checklist).

Classification: consideration should be given as to whether the terms of a proposed investment mean that the public sector will control the investee or bear the majority of its risk and reward, causing a private sector entity to be reclassified to the public sector. The ONS is responsible for determining whether bodies should be classified to the public sector and use international statistical guidance to do so. Departments and public financial institutions should engage their Treasury spending team early in the policy development process if a potential FT may pose classification risks, who will liaise with Treasury classification experts. (Section 4 of Annex E – the FT Checklist).

Expertise and public financial institutions: FTs involve complex instruments and commercial negotiations, so should be managed by bodies with suitable expertise and experience generating, developing, and implementing FTs. All large-scale, high-risk, or complex FTs and guarantees should be delivered by expert public financial institutions (see annex A for a list of bodies that have been designated under this framework) unless otherwise agreed by the Treasury. They should be involved early in the design of any FT they are intended to deliver on behalf of a department. (Section 5 of Annex E – the FT Checklist).

Box 2.C Other considerations in policy design

For loans

Creditworthiness – when issuing loans, consideration should be given to creditworthiness of the borrowers, to ensure understanding of the risk of default that the loan exposes the government to.

Interest and repayment – the financial return will be dictated by the interest a lender charges the borrower as a share of the principal (i.e., the amount loaned) and the term date for repaying the principal.

Tenor – the term of the loan to maturity should be set out clearly in contract when the loan is agreed. This can be minimised to reduce risk and make sure that capital is returned to government.

Collateral – it could represent value for money to require recipients of loans to post collateral to minimise the risk held by government or alternatively to allow government to take security over an asset, on insolvency of a borrower, to repay a loan.

Seniority – where government secures the status of a senior lender, i.e., that borrowers shall reimburse government before any other creditor, this should reduce the credit risk associated with a loan although it may also limit the efficacy of an intervention.

For equity investments

Equity stake – the size of stake should be limited to avoid inadvertent reclassification to the public sector, alongside consideration of other factors like control taken. Taking a majority stake in a company will lead to classification to the public sector; smaller stakes can still result in reclassification depending on the overall level of control exerted.

Shareholder responsibility – direct equity investments require actively exercising shareholder responsibilities via an expert function such as UKGI or public financial institutions.

Dividend – government should consider what dividend it receives when assessing the value for money of an equity investment, as well as the status of its stock (e.g., preferred stock gives a higher claim to dividends and more shareholder protections).

Support in developing FT proposals

Various bodies can provide support in developing FT proposals:

- Spending teams in the Treasury are an initial port of call in the idea generation stage to provide advice when considering whether an FT is a suitable intervention and on the classification of transactions.

- UKGI can advise departments on various technical issues like understanding risk, pricing an FT, modelling income, and developing delivery models. UKGI can also advise on complex transactions through their lifecycle, including on terms, deal tactics and contingency planning. UKGI can be contacted at UKGIAdvisory@ukgi.org.uk.

- Finally, when departments deliver an FT via a public financial institution, their expertise and the views of their sponsor department should be incorporated early in the design of that FT.

3. Delivery through expert institutions

Overview

The most suitable institutions to deliver FTs and guarantees are public financial institutions set up as centres of expertise in the management of financial instruments, who have appropriate staff, institutional design, and risk management models.

To ensure value for money, all large-scale, complex, or high-risk FTs and guarantees should be delivered by public financial institutions designated under this framework, unless otherwise agreed by Treasury. These institutions are subject to bespoke spending controls.

The current list of designated public financial institutions is set out in Annex A and will be updated on an ongoing basis.

Public financial institutions

Controls for managing public financial institutions

To ensure the right balance between robust controls and commercial flexibility, public financial institutions should be managed as investment bodies, not as if they were spending departments.

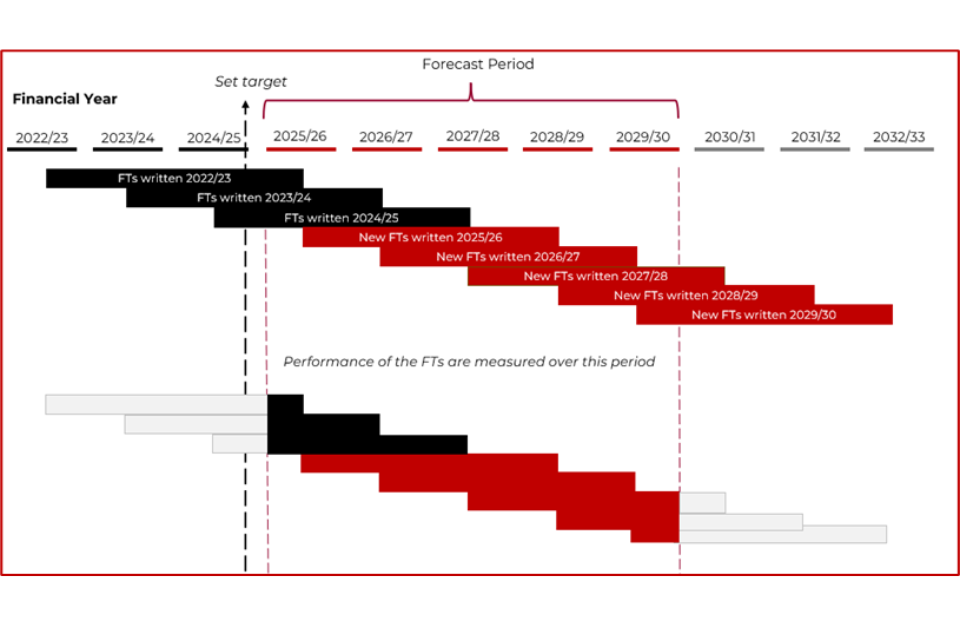

This means that typically, the Treasury, in conjunction with the sponsor department, will manage public financial institutions’ financial impact by setting a total capacity, a risk limit, a returns target, and an annual FT limit, instead of setting budgets at Spending Reviews. In some cases, it may still be appropriate to manage public financial institutions in DEL and entities in central government still require parliamentary approval of spending via the estimates process.

The financial controls applied to public financial institutions are:

- A total capacity: how much capital a public financial institution holds to invest in FTs and guarantees before any recycling of returns and therefore its total spending allocation. Changing a public financial institution’s total capacity will affect the size of its balance sheet.

- A risk limit: all FTs carry the inherent risk of potential losses. A risk limit will place a constraint on the level of risk that a public financial institution can undertake by setting a ceiling on the scale of losses it should experience in a low probability downside economic scenario. Once set, institutions are expected to manage their risk exposure within this limit. Risk limits should be set using an economic capital-based approach, as set out in Chapter 4.

- A returns target: public financial institutions should have a financial returns target to embed commercial discipline in their management and define their investment approach. If institutions have a rate of return below government’s cost of borrowing, costs incurred worsen the government’s fiscal metrics and need to be traded off with other spending. Returns targets are covered in Chapter 4 and Annex B.

- An annual FT limit: to place an upper bound on the cash requirement of a public financial institution, which will not typically be a binding constraint as it should be set above the expected annual expenditure of the public financial institution.

These controls do not remove existing governance within public financial institutions – they should be implemented through an approach agreed with the senior management and board, alongside the sponsor department and Treasury. The spending of public financial institutions still affects departmental budgets and should be forecast based on projected investments agreed via their business planning.

The Treasury will publish any changes to the above control levers for designated public financial institutions at fiscal events.

Public financial institution designation process

Organisations are designated as public financial institutions based on the criteria set out in this chapter, at the discretion of the Chief Secretary to the Treasury. This is an administrative designation for spending control purposes and does not relate to the statistical definition of public financial corporations.

Annex A sets out the current list of designated public financial institutions. This list will be added to on an ongoing basis by reform of existing bodies to align with these criteria or creation of new entities. This status can be withdrawn by the Treasury as well as granted.

Departments can put the case to the Treasury for new entities to become public financial institutions at any time. To do so, they should provide a submission that sets out how an institution they sponsor either already meets the criteria or provide a clear time-bound plan for institutional design or reform to achieve the criteria. The Treasury would expect this will normally be done in parallel to a business case for either a new or expanded FT programme or portfolio that the department expects the newly designated public financial institution to deliver.

Public financial institution criteria

The Treasury does not expect all public financial institutions to be designed identically, as different models can achieve similar outcomes. The Treasury does expect that entities seeking to become public financial institutions meet the following criteria or show how the intent of each criterion can be achieved by other means. The criteria are:

- Type of organisation that can be designated: public financial institutions will typically be arm’s length bodies (ALBs), non-ministerial departments or public financial corporations (depending on their exact design). Subsidiaries or other sub-divisions of these entities can be designated as public financial institutions on the condition that they have clearly identifiable and separatable financial statements through which their returns target and risk limits for their FT and guarantee portfolio can be managed and all other criteria are met. This will be appropriate where the wider ALB delivers large grant programmes, which would not be consistent with a public financial institution’s primary activity, but where there are policy benefits to managing the grant and FT programmes within one entity.

- Primary activity: the principal activity of public financial institutions should be making equity investments, loans, guarantees, or other activities intended to generate a financial return. This should be their area of specialist delivery, with institutional design tailored to support this. While some expenditure, for example on administration, will not be investments, most of their expenditure should take the form of financial activity (even if in some cases the entities or assets invested in are classified to the public sector). Non-investment expenditure should be covered by investment income when institutions are mature.

- Operationally independent: public financial institutions should usually be authorised to make day-to-day investment decisions independently, based on strategic objectives and principles set by ministers within specified limits and delegated authorities set by their sponsor department and agreed with the Treasury. Ministers or departments can only request public financial institutions make investments in specific companies or projects that fall outside the institution’s usual investment criteria via a designated and transparent process. This is to ensure that public financial institutions can make investment decisions at arm’s-length from government, with autonomy to identify investment opportunities through market engagement, set their own pricing for transactions, assess whether an investment represents good value, and manage risk of their portfolio.

- Expertise and capability: public financial institutions should employ staff with suitable expertise to manage complex financial instruments and should have sufficient organisational capabilities to manage a significant investment portfolio. This should include senior leadership with relevant experience, an appropriate remuneration framework, strong governance for making independent investment decisions, robust capital management processes, and good systems and controls for risk and financial crime management.

- Balance sheet: public financial institutions should manage their FTs and guarantees as a holistic portfolio, with institutions that also issue some grants having a segregated financial instrument balance sheet for management and audit purposes. Beyond this, the Treasury’s preference is that public financial institutions should be set up either as government-owned companies with their own balance sheet financed through Treasury or department provided equity and debt, or as non-ministerial departments mirroring this arrangement. If specifically agreed by the Treasury and where there is a clear value for money case, institutions can borrow directly from financial markets.

- Investment limits: the investment limits of public financial institutions will be capped. This will typically be operationalised by providing public financial institutions with equity and debt financing, both of which are limited by agreement with the sponsor department and Treasury, grant funding where they have a subsidised rate of return, or another form of cash spending control (such as DEL budgets).

Box 3.A Balance sheet of a public financial institution

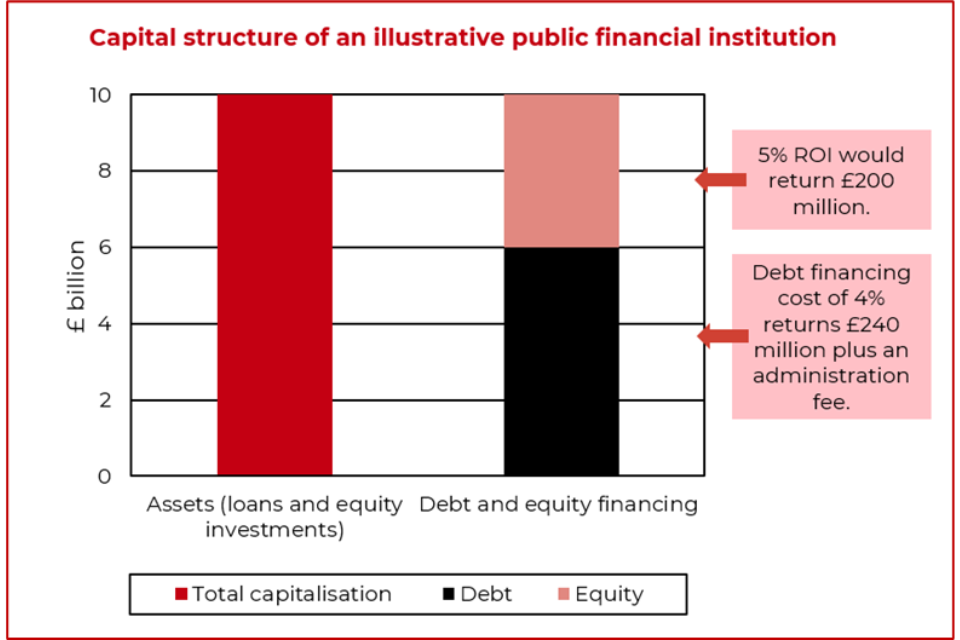

As set out in the example below, a public financial institution should preferably be financed by equity and debt finance on their balance sheet (in some cases just equity). The sum of their finance is equal to the total capacity of the organisation to make investments.

For equity finance, targeted returns are agreed between the public financial institution, the sponsor department and Treasury, to be recycled or taken as a dividend. For debt, this must be repaid to the Treasury or sponsor at the gilt rate plus an administration fee.

In this example, the £240 million from debt financing costs would be repaid and the £200 million made on equity returns would be recycled in the institution or returned to the sponsor department.

-

Rate of return or financial objectives: public financial institutions should set a target rate of return of at least the government’s cost of borrowing (see Chapter 4 and Annex B), or an equivalent arrangement, as agreed with the sponsor department and Treasury. Public financial institutions should set a target at the portfolio-level and this return will be targeted over time not year-on-year. The targeted rate of return can be subsidised by departments to allow the institution to make investments that return less income to support policy objectives (see Chapter 4 and Annex C). Where this occurs, the costs will be traded-off with other spending within the constraints of the government’s fiscal rules. In practice, returns target should be adjusted to factor in an institution’s relevant operating expenses and should have a ceiling as well as a floor to ensure that institutions focus on tackling market failures rather than crowding out private capital.

-

Recycling of returns: the public financial institution’s business plan and dividend (or other form of income distribution) policy will set the long-term scale of its balance sheet. As a default, institutions should recycle repayments on principals of loans and sales of equity into new investments, subject to meeting their returns target. This ensures they have a permanent capital base and maintain their existing scale of activity. Profits generated will be reinvested by the institution, enabling them to grow or returned to the sponsor department or Treasury.

Box 3.B Dividend or income distribution policy

In some cases, the sponsor of a public financial institution should set and agree with the Treasury a policy for distributing income generated across the institution’s portfolio when setting its business plan. A dividend or equivalent will be appropriate if it represents better value for money for part of a public financial institution’s returns to be spent on other priorities, rather than being recycled.

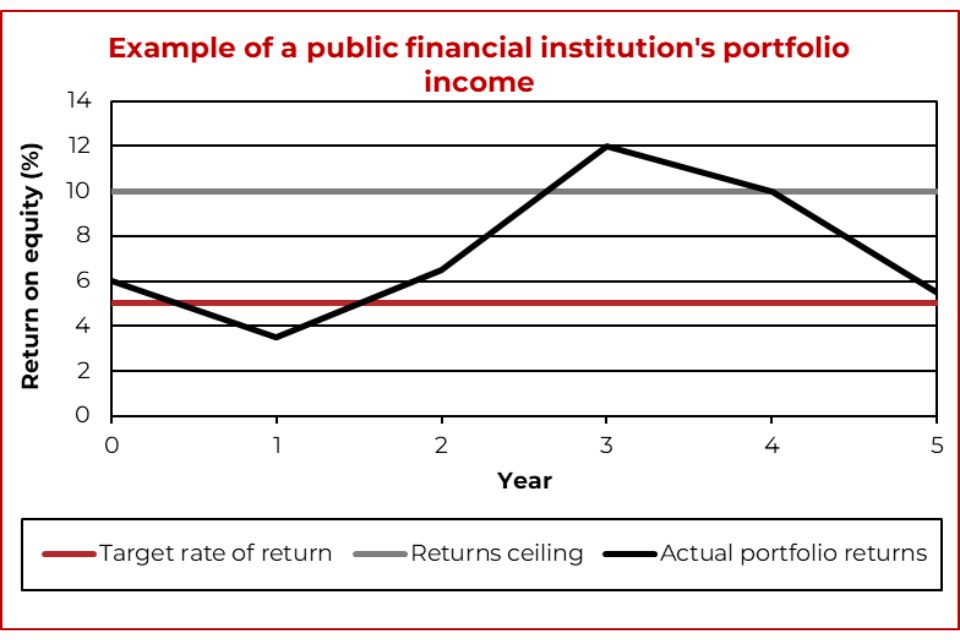

If this is desired, the Treasury recommends setting a ceiling for the public financial institution’s rate of return across its portfolio as a method to implement a dividend. This means that if the income exceeds the ceiling in a year, or over a defined period, an agreed portion of income above the ceiling would be taken as a dividend payment or equivalent by the sponsor department or the Treasury.

Sponsor departments are encouraged to consider factors such as the type of capital subject to this policy and legal requirements.

The chart below shows an illustrative returns ceiling of 10% and an average target return of 5%. The public financial institution’s income exceeds the ceiling in year 3 but not on average in the 5-year period.

- Mandated activity or service arm: it may be value for money to use a public financial institution’s expertise to deliver FTs that are intentionally loss-making from the outset to achieve a policy outcome. Loss-making FTs do not make an overall return above government’s cost of borrowing but can be better value for money than grants as they require some repayment. These activities should be transparently reported in the department’s annual report in line with their financial reporting framework. Public financial institutions should manage them via the mandated activity or service arm models, set out in Chapter 4, with any departmental ‘subsidy’ reported in its accounts. As set out above, this may mean the institution has a subsidised rate of return. With agreement of the sponsor department and the Treasury, where a public financial institution generates realised profits above its return target, this may be used to cross-subsidise mandated activity FTs.

- Financial reporting: public financial institutions should produce annual reports and accounts in line with IFRS or the Government Financial Reporting Manual (FReM).

- Risk management: public financial institutions should manage risk through an economic capital-based model described in Chapter 4. This will help government understand its downside risk associated with FTs and guarantees and act as a control on public financial institutions’ risk exposure. Public financial institutions should also have suitable risk management processes in place in line with the Orange Book.[footnote 15]

- Oversight: in the medium-term, the Treasury may consider whether additional oversight is required to manage the economic capital of public financial institutions, for example subjecting them to quasi-regulatory arrangements (as is already the case for some bodies).

Potential flexibilities for public financial institutions

Alongside meeting the criteria, designated public financial institutions may be granted certain flexibilities by the Treasury and its sponsor department to support their abilities to deliver good value investments and function in a commercial and independent way.

These flexibilities are at the discretion of the Chief Secretary to the Treasury and will require a strong business case and demonstration that robust institutional-level controls are in place, such as an economic capital model for managing risk. The flexibilities may include:

- For entities in central government - how annual budgets are set, including management of expenditure in AME. This would mean that the institution’s investments score to CAME FT and expected credit losses, write-offs, and income score to RAME.

- Granting institutions higher delegated limits for Treasury consent than other organisations, with these limits likely varying depending on the type of product (e.g., debt, equity or guarantees).

- A bespoke pay framework for senior and specialist roles, to allow institutions to recruit the external expertise needed to manage complex financial instruments.

- Applying controls on an institution level, not on a programme basis, including the flexibility to deploy cash and risk budgets across their range of programmes, to best meet strategic objectives.

- Providing the certainty of a permanent capital base to support institutions’ market credibility and medium-term business planning.

When public financial institutions should deliver FTs

To ensure value for money and minimise unnecessary risk, all new large-scale, high-risk, or complex FTs and guarantees should be delivered by designated public financial institutions via either their business-as-usual activity, mandated activity, or service arm, unless there is specific Treasury agreement to do otherwise.

- Materiality threshold: ‘large-scale’ is defined as any transaction or programme of transactions that are above a department’s relevant delegated limit. Treasury spending teams should agree FT-specific delegated limits with departments, which can include separate limits for Treasury consent and as a materiality threshold. Any transaction above the relevant limit set should be delivered by a public financial institution unless Treasury agreement is given to do otherwise. When seeking Treasury consent for FTs above their delegated limit, departments are required to return the FT Checklist (Annex E) to provide the information necessary for the Treasury to assess FT bids.

- Complexity and risk level: there may be some FTs or guarantees where, despite being within a department’s delegated limits, they are sufficiently complex or high-risk that they should be delivered by a public financial institution. Table 3.1 covers factors affecting complexity of an FT or guarantee. Departments should make a judgement about how many of these factors are present to support an assessment of whether delivery via a public financial institution is appropriate.

Table 3.1 Factors affecting complexity

| Factor | Impact on transaction complexity |

|---|---|

| Type of Financial Instrument | Instruments like structured finance (e.g., asset backed securities) or equity require more specialist expertise to deliver than simpler products like loans. Non-standard features also increase complexity. |

| Transaction Size | Higher value transactions require more robust management processes, including sophisticated due diligence and risk assessment capabilities. |

| Duration and Timing | Longer-term transactions are more complex and amplify risk characteristics as they require ongoing management, monitoring and adjustments. Uncertain repayment schedules will further this risk. |

| Number of Parties Involved | Transactions involving multiple parties (e.g., buyers, sellers, intermediaries, co-investors, guarantors) tend to be more complex to manage. |

| Market Conditions | More volatile or uncertain market conditions require more sophisticated analysis and risk management. |

Table 3.2 also outlines some of the key risks that may be present and need to be managed in delivering a particular FT, guarantee or programme. Departments should similarly make a judgement about how risky a transaction is and the requirements to manage those risks, when considering the appropriate delivery vehicle.

Table 3.2 Common risks present in FTs

| Risk type | Description |

|---|---|

| Credit Risk | The risk that a borrower or counterparty will fail to meet their contractual obligations. This requires thorough credit assessments before entering transactions and ongoing monitoring of the financial health of investees. |

| Market Risk | The risk of losses due to changes in demand, interest rates, exchange rates, or asset prices. This requires monitoring of market trends and reducing exposure in isolation and in a portfolio. |

| Operational Risk | The risk of losses from process failures, systems, or events (e.g., fraud, cyber risk, system failures). This requires good controls, capability, reporting, and training staff to recognise and address risks. |

| Country Risk | The risk of losses due to instability in a country where the transaction is taking place. This requires country-risk assessments before engaging in cross-border transactions. |

| Concentration Risk | The risk of losses due to overexposure to a single borrower, sector, or geographic region. This requires diversification of a portfolio and limits on exposure to a single entity or sector. |

| Model Risk | The risk of losses due to errors in models used for valuation, risk analysis, or decision-making. This requires capable analytical staff and robust quality assurance processes for critical models. |

| Pricing Risk | The risk of pricing an FT without understanding its financial implications, leading to poor VfM. This requires negotiators with commercial expertise and benchmarking to market rates. |

UKGI can be engaged early in policy design to provide expert guidance on whether an FT or guarantee is sufficiently complex or high-risk to necessitate delivery by a public financial institution, and which institution should be considered for the transaction.

Exceptions to delivery via public financial institutions

If departments wish to deliver an FT or guarantee above the materiality threshold or that are judged to be particularly complex or high-risk through a non-designated organisation, they must seek the approval of the Treasury.

Departments must set out why a public financial institution is not the right delivery vehicle, which will usually only be accepted for investments via non-government institutions (e.g., multilateral banks) with equivalent capabilities to public financial institutions.

For FTs above the materiality threshold to be delivered outside of a public financial institution, the Treasury will expect to see the ‘public financial institution criteria’ described in this chapter being applied by the institution responsible for delivery.

4. Transparency on risk and return

Overview

As the government’s investment fiscal rule recognises the value of financial assets like equity and loans generated by FTs and nets these assets off the debt usually required to finance them, it is important to have robust and transparent management of risk and return so that FTs support fiscal sustainability.

To achieve this, FTs must either generate income that covers government’s cost of borrowing or where government makes investments that it expects at the outset to be loss-making, costs must be transparently recognised in budgets in line with an entity’s financial reporting framework. This ensures use of FTs do not worsen debt, as the loss-making element of any FT programme will be reflected in the OBR’s fiscal forecast and traded-off within the government’s fiscal rules.

In addition, government will set a limit on exposure to unexpected losses from FTs in remote economic scenarios, using an economic capital approach to constrain their risk within a defined limit.

A government financial investment report

Government will be transparent about the investments it is making on behalf of taxpayers and ensure all relevant information is accessible to the public and to Parliament.

It will publish an annual Government Financial Investment Report, setting out the financial assets owned by departments and public financial institutions, their latest valuations, their financial performance, and policy benefits achieved. This assessment will examine FTs at a portfolio or institution level. Over time, the report will also assess risk in downside economic stress scenarios, in line with best practice applied in the banking sector.

The report will be delivered by UKGI, the government’s centre of expertise for corporate finance and corporate governance. The government will ensure the information used in this report is robust and independently verified, particularly on the valuation of government’s assets. This report will use asset valuations drawn from government accounts audited by the National Audit Office (NAO) as well as other relevant unaudited information. The Treasury is working with the Comptroller and Auditor General to ensure that the report builds on the existing audits of asset valuations appropriately.

The first iteration of the report will be produced in Autumn 2025 and published annually thereafter.

Targeting a suitable rate of return

All FT programmes and public financial institutions should have a target rate of return to embed good commercial management behaviours. Some investment losses will occur in any portfolio, so for public financial institutions rates of return should be targeted at an institution or portfolio level and for departments at a programme level.

A fiscally neutral baseline

The government’s investment rule recognises where the value of a financial asset offsets the liability usually incurred to finance an FT. When individual FTs or programmes generate a return that covers the government’s cost of borrowing, they are fiscally neutral. This cost of borrowing is the relevant gilt rate (see Annex B) – the cost that the government must pay to service debt issued to fund FTs. In practice, FTs will be priced to also adjust for risk (e.g., credit or investment risk) and cover relevant operating expenses.

The fiscal implications of FT programmes should be judged against this fiscally neutral baseline, but FTs can still be value for money if they generate a lower rate of return but deliver social benefits. The use of this baseline is not a value judgement on the appropriate pricing of FTs, but rather a tool for assessing their fiscal implications. Indeed, all government spending, which is largely funded through taxation or borrowing, has a social cost, and generating a rate of return at or above the government’s cost of borrowing may not be sufficient for an FT intervention to be welfare-generating in an economic sense.

Annex B outlines guidance and the methodology that public financial institutions and departments should use when assessing returns of new investments against the government’s cost of borrowing and setting an appropriate returns target.

Public financial institutions’ returns target

As set out in chapter 3, public financial institutions should be set a returns target of at least the fiscally neutral baseline. This returns target should also recognise relevant operating expenses.

In some cases, it may be suitable for this rate of return to be subsidised by departments where these costs cannot be offset by the returns from other FTs, to allow the institution to make loss-making investments that support policy goals. This departmental ‘subsidy’ will be treated like other spending, enabling ministers to determine the most effective means to deliver policy priorities. When public financial institutions and sponsor departments set a returns target, they should recognise the amount and timing of any ‘subsidy’ received from departments to avoid double counting or timing mismatches.

In other cases, it may be suitable for the institution to target a more commercial return to avoid crowding out private capital on a pricing basis or account for their portfolio risk. This judgement should be taken based on the specific market and policy context in which each institution operates, with the target return and level of any ‘subsidy’ agreed with the sponsor department and Treasury.

The returns target should be used in conjunction with several other performance measures that assess the public financial institution’s wider policy impact, the relative importance of which should be agreed between public financial institutions, their sponsor department, and relevant departments with a delivery interest as appropriate. Full adherence to this framework is required regardless of satisfying any broader performance measures.

Public financial institutions should write annually to their sponsor department and the Treasury to set out their performance against their returns targets and explain any factors driving significant variance from their target, with all parties recognising that the inherently volatile nature of investments will mean that a prudently managed investment portfolio may underperform or overperform in any given year.

A robust approach to managing risk

Overarching risk management principles

When the government undertakes financial investments, it is taking on the risk of unexpected losses. All government institutions managing an FT or guarantee portfolio are expected to have robust arrangements to control risk in line with the Orange Book.[footnote 16]

Appropriate governance arrangements must be in place, setting out clear roles and responsibilities for the Board (or equivalent), Audit and Risk Committees, and Chief Risk Officers with respect to managing risk across the organisation. The three lines of defence as outlined in the Orange Book should be implemented to ensure day-to-day risk management is supported by fit-for-purpose risk policies, frameworks, and training. In addition, overall organisational risk management should be independently assured by a function internal to government.

These processes should cover all financial and operational risks associated with an FT or guarantee portfolio, such as those set out in table 3.2. This should include robust arrangements to manage fraud, in line with standards set by the Public Sector Fraud Authority (PSFA), including financial impact targets for minimising fraud and error to be agreed with the PSFA where appropriate and proportionate.

Setting an economic capital-based risk limit

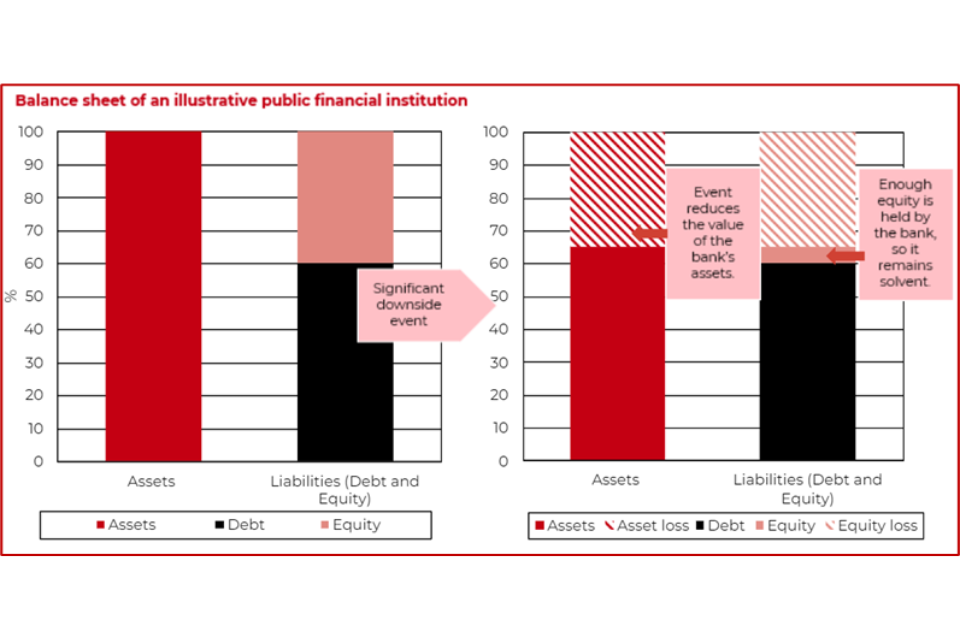

Many regulated financial organisations hold capital to protect them from insolvency and use economic capital models to help them understand their downside risk, which informs decisions on the amount of capital held. To help government understand its downside risk from FTs, public financial institutions must implement an economic capital-based model. A limit will then be set to control the amount of risk that a public financial institution is subject to, which should be agreed with the sponsor department and the Treasury.

The economic capital limit will either be based on the equity financing of an institution or will be virtual economic capital (VEC), where an organisation does not hold equity and instead the economic capital limit represents a maximum value-at-risk for its portfolio up to a certain confidence level in a low-probability downside scenario.

It is expected that these limits, in most cases, should allow for a higher risk appetite than regulated financial organisations to support policy objectives and deliver investments that are additional to financing available from private capital markets. The risk limit set should also be tailored to the specific mandate of each institution.

Guarantees will be controlled in the same way as FTs for the purpose of economic capital limits, as they involve similar risk-taking and so managing them under a single framework aids consistency and trading-off risk exposures from different interventions.

Box 4.A Economic capital models

Economic capital reflects the expected riskiness of investments and measures the amount of capital reserve needed to absorb downside loss events. An economic capital limit will place a constraint on the level of risk that an entity can undertake. It does this by setting a ceiling on the scale of downside losses that an entity or programme should experience in a low probability outcome.

Traditionally, an economic capital model is linked to capital, i.e., that financial institutions can only take on risk such that potential downside losses can be met from their equity in all but the most remote scenario. This is the approach taken by private sector banks under Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) regulations.

Once public financial institutions have been set an economic capital or VEC limit, they are expected to manage their risk exposure within this limit, maintaining an appropriate level of headroom against the limit and trading off capital allocation between different FTs and guarantees to maximise impact against their policy mandate.

Implementing economic capital-based modelling

To implement this, public financial institutions should model total potential losses their portfolio could face in a low probability (e.g., a 1 in 100) outcome. Key components of modelling include all material risks faced by an institution, such as credit risk, market risk, operational risk, country risk, and concentration risk (see table 3.2 for definitions). Institutions should also consider diversification of their financial assets, as well as correlations in potential risk triggers across assets held.

Public financial institutions should then for all transactions they undertake, assess the impact on economic capital or VEC consumption. They should also determine their current exposure by retrospectively calculating the capital or VEC consumed by their existing portfolio of FTs and guarantees (except for those delivered via the service arm).

Alongside an economic capital model, public financial institutions should undertake regular stress-tests for their FT and guarantee portfolio, in line with best practice in the banking sector.

Annex D sets out an example of a standardised economic capital model, which is one approach that can be used depending on the nature of investments held by and risks facing the institution. Where standard approaches are judged to be unsuitable or when modelling could be improved, institutions should develop their own modelling approaches calibrated to specific risks they face. These methodologies should be quality-assured by a Treasury-approved organisation.

In some cases, the implementation of an economic capital model will be done over time as organisations develop their level of sophistication. However, the ability to model and manage risk effectively within an exposure limit, or an agreed time bound plan to develop this capability, is a pre-requisite to consideration of any changes to the capitalisation of public financial institutions.

When it is proportionate to the scale of financial risk taken by FTs or guarantees managed by departments, the Treasury will work with departments to implement a VEC model in line with this guidance. In addition, the Treasury will explore if VEC should be applied to government-provided insurance.

Understanding government’s overall risk exposure

The Treasury will use aggregate information on the risks across government’s FT and guarantees portfolio to consider an appropriate overall level of financial risk for government to hold and support decisions on trading off exposure across parts of government’s portfolio.

To facilitate this, the Treasury will work with public financial institutions and departments over a defined period to agree a set of consistent parameters, scenarios, and stress tests to be used in downside risk modelling, so that these may become aligned over time.

In time, the annual Government Financial Investment Report will report on the aggregate level of risk taken across government’s investment portfolio and assess economic stress scenarios.

Budgeting for losses

Treating loss-making FTs like other spending

It is possible that the best value for money way to achieve a policy objective may be a loss-making FT. This is an FT priced to generate a rate of return below the gilt rate, so the income to government is expected from the outset to be lower than government’s cost of borrowing. In practice, individual FTs should also be priced to adjust for risk and cover relevant operating expenses.

This framework ensures that the cost of loss-making FTs is recognised by departments and that the loss-making element is treated as spending and is traded off with other resource costs, in line with the department’s financial reporting framework.

When making decisions on budget allocations, the Treasury will primarily consider the fiscal rather than the budgetary impact of a proposal. Annex E sets out the FT checklist for new FT proposals, which includes requirements on modelling financial impacts.

How losses affect departmental budgets

The government accounts for the risk and crystallisation of losses through its IFRS-based accounting regime and associated budgeting system, which transparently reflects their cost within departmental budgets. This framework is set out in detail in CBG. For example:

- Expected credit losses generally score to resource DEL. The estimate reflects a probability-weighted amount determined by evaluating a range of possible outcomes.

- Other changes in the fair value of financial assets generally score to resource AME.

- If government issues FTs below their fair value, the associated loss – i.e., difference between the transaction price and fair value – generally scores to resource DEL.

- Write-offs score in resource DEL and worsen net financial debt and public sector net investment, but do not affect the current budget balance.

Where the Chief Secretary to the Treasury has agreed that the spending of a specific public financial institution will be managed in AME, all the charges above will score in Resource AME not DEL.

Mandated activity and service arm models

Loss-making FTs via public financial institutions

Where there is a strong rationale for intervention, public financial institutions and departments can collaborate to develop blended finance solutions. This can include loss-making FTs as well as combinations of grant or other forms of spending together with FTs.

FTs should be delivered via public financial institutions wherever possible – including loss-making FTs – as their expertise ensures schemes are well-designed and maximise impact for their costs. Departments seeking to deliver a loss-making FT should engage early with a public financial institution and its sponsor department to support design and delivery. This should be via a project approach, with both parties committing expertise and resources, and co-designing interventions. Any decision to proceed should consider the institution’s capacity and trade-offs with their core delivery responsibilities.

This framework provides two models for delivering loss-making FTs through designated public financial institutions:

- A mandated activity model, where public financial institutions hold all the risk and return, with a fixed ‘subsidy’ provided by a department to cover the loss-making element; and

- A service arm model, where departments hold risk and return, and the FT sits on the department’s balance sheet, managed in DEL.

The Treasury’s preference is that loss-making FTs are delivered via the mandated activity model by default because it transparently records income foregone compared to an institution’s returns target and best leverages the institution’s expertise to manage risk.

The mandated activity model

The mandated activity model is available to all departments exploring FTs in areas covered by a public financial institution’s remit. A public financial institution has Accounting Officer (AO) responsibility for value for money decisions under this model, so it is important for them to be involved from the outset. Some key aspects of the model are:

- For loans that charge interest rates less than government’s cost of borrowing and additional pricing for risk, the departmental ‘subsidy’ amount will be the spread between the interest rate the public financial institution would have otherwise charged (factoring in risk and their returns target) and the rate the department desires to charge. The ‘subsidy’ will be paid each year to subsidise interest income foregone and will be agreed and fixed for the department at the outset. It is important that public financial institutions retain control of pricing of FTs to maintain independence and commercial rigour in management of FTs, although this does not necessarily mean a commercial price, particularly where there is policy rationale to provide concessionality.

- A departmental ‘subsidy’ can be provided at a transaction, programme, or whole institution level. A departmental ‘subsidy’ to a whole public financial institution would be appropriate if a department expected, based on the market it is investing in, that it should be structurally loss-making to achieve its policy goals.

- Budgetary impacts depend on the relationship between the institution and the subsidising department. An institution subsidised by its sponsor department will not have a direct budgetary impact, as it is a transaction within the departmental group. If a department is subsiding an institution sponsored by another department, then this will have a budgetary impact. Further details are set out in Annex C.

- The level of ‘subsidy’ will not necessarily mirror the cash requirements of mandated activity nor a public financial institution’s drawdowns from its sponsor department or the Treasury.

- With agreement of the sponsor department and Treasury, where a public financial institution generates realised (i.e., not forecast) profits above its return target, this may be used to cross-subsidise mandated investments. The institution must still achieve its return target and ensure costs of mandated FTs are transparently recorded.

The service arm model

Service arm FTs sit on the department’s balance sheet and the public financial institution acts as an agent for the department, administering investments and providing support to the department in negotiating and structuring any deal. Departments provide all funding, hold all the risk, budget for the FT in DEL, and have AO responsibility for value for money decisions. For this support, public financial institutions typically charge a fee to cover their operating expenses.

The service arm will be suitable for one-off transactions, crisis interventions, or programmes where changing the mandate of an existing institution or setting up a new one is not proportionate.

Departments should discuss with their Treasury spending team if they wish to use a public financial institution’s service arm.

5. Treasury approval for financial transactions

The business case process for FTs

When a department has a clear rationale for intervention via an FT or programme of FTs, and the key material characteristics of the investment are identified, then the intervention should be assessed using existing frameworks for considering the use of public resources.

Application of the Five Case Model

The Green Book is guidance issued by the Treasury on how to appraise policies, programmes, and projects, within which the Five Case Model is the key approach to help government evaluate spending proposals. There are some key FT-specific considerations for each part of a business case, building on the principles set out in Chapter 2.

- Strategic Case: this initial stage requires an explanation of the objective that the FT seeks to meet and its links to Ministerial or wider government objectives. Here, it would be important to articulate the market failure that the FT seeks to address, including why private capital markets have been unable to provide this financial product and how this intervention will be additional to private finance.

- Economic Case: this stage would be where most of the option appraisal takes place. The FT should be appraised against other interventions such as grant spending, guarantees, and regulation, but also the ‘business as usual’ or ‘do nothing’ option. Each option should be appraised as to what extent they achieve the policy objective and to what degree they provide value for money. This may be the point when an option should be removed from the longlist.

- Commercial Case: this is the point at which consideration of counterparties involved should be articulated, with an emphasis on understanding the risks (e.g., credit risk or operational risk) involved in delivery, where the balance of risk lies between the counterparties and government, as well as how negotiable any arrangement is. This might be demonstrated via the business plan of the counterparty or a summary of the key elements of the transaction(s). Such analysis will bring out how credible an investment deal will ultimately be.

- Financial Case: here, the pricing and estimated fiscal impact of the FT should be described, alongside budgeting and accounting impacts. The rationale should be presented for why these impacts are affordable for government. This will be supported by forecasting the revenue stream that pays for the income used to repay the FT.

- Management Case: finally, how the intervention will be delivered should be outlined. This includes which public financial institution is delivering the FT or why another organisation is equipped to do so, how ongoing risks will be monitored, and how government will manage any shareholding. In addition, this section should set out how the intervention will be evaluated to apply future learnings at key stage milestones and review points.

The Financial Transaction Checklist

As FTs differ from conventional public spending in several ways, it is important that all relevant FT-specific issues are considered by departments through the business case process. To facilitate this, and to provide standardised information to Treasury ministers on FTs, the Treasury has produced the financial transaction checklist to support departments to consider and communicate this key information.

The financial transaction checklist is required to be completed when Treasury consent is sought for a new FT, either because the FT is novel, contentious, or repercussive, or where FTs are above a department’s delegated limit. It must also be provided alongside business cases for FT budget allocations at fiscal events or Spending Reviews, when requested by the relevant Treasury spending team, or when changing the capitalisation of a public financial institution.

Early engagement on upcoming proposals is encouraged, so it is good practice for a draft or partially completed checklist to be shared with the Treasury to facilitate discussion. The checklist is intended to be a flexible document, so in some cases the questions will be less relevant to a specific FT under consideration. The checklist should be provided to the Treasury alongside a full business case for FT proposals and the checklist should usually be completed and shared with the Treasury first, as the business case will tend to provide more detail.

The checklist should be submitted to the relevant Treasury spending team (responsible for the department’s policy priorities and affordability of any FT), who will work with the Treasury’s Balance Sheet Team (responsible for government’s overall stock of financial assets and FT policy) and the General Expenditure Policy team (responsible for overall control of public spending) to consider the proposal.

The checklist is provided in Annex E with guidance on completing the checklist in Annex F.

Annex A: List of designated public financial institutions

Organisations are designated as public financial institutions based on the criteria set out in Chapter 3, at the discretion of the Chief Secretary to the Treasury.

This list will be updated on an ongoing basis when the Chief Secretary to the Treasury makes decisions to designate any additional bodies as public financial institutions or change the designation of existing bodies.

Current list of designated institutions

The current list of designated public financial institutions that have been deemed to meet the criteria set out include:

- British Business Bank PLC

- British International Investment PLC

- National Wealth Fund Ltd

- UK Export Finance (legally the Export Credits Guarantee Department)

- The Student Loans Company, which does not function like a typical banking institution, has been designated as a public financial institution as they have the requisite capability to manage this unique asset. Student loans are subject to a bespoke set of financial controls and accounting treatment in the National Accounts. The arrangements in place for student loans achieve the same outcome as the controls that are applied to other public financial institutions.

Future designation decisions

The Treasury and Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government are working together to ensure a suitable model is in place within Homes England to support delivery of the government’s housing commitments, in line with the principles of this framework.