Supplementary content: Forensic Information Databases annual report 2022 to 2023 (accessible)

Updated 19 July 2024

Objective and scope

Available as Supplementary Content to the FIND Strategy Board Annual report published annually.

References

References referred to in relevant footnotes throughout.

The FIND Strategy Board Annual report can be found at National DNA Database documents.

The Forensic Information Databases Strategy Board

Governance and oversight of the National DNA Database[footnote 1] is provided by the Forensic Information Databases (FIND) Strategy Board, established in statute[footnote 2] as the National DNA Database Strategy Board. Following the publication of the government’s Forensic Science Strategy, the decision was taken to expand the governance role of the Strategy Board to also cover the National Fingerprint Database, during 2016/2017 and the new name was adopted to reflect this wider strategic role.

The strategic aim of the Strategy Board is to provide governance and oversight for the operation of the National DNA and Fingerprint Databases:

- it may issue guidance about the destruction of DNA profiles under the Protection of Freedoms Act 2012 (PoFA)[footnote 3];

- it may issue guidance about the circumstances under which applications for retention under PoFA[footnote 4] may be made to the Biometrics and Surveillance Camera Commissioner (‘The Biometrics Commissioner’)[footnote 5] [footnote 6];

- it must publish governance rules which must be laid before Parliament[footnote 7]; and

- it must make an annual report to the Home Secretary about the exercise of its functions[footnote 8].

The governance rules[footnote 9] set out in more detail the way in which the Board operates, and include its objectives[footnote 10] which are to implement strategy and policy to ensure:

- the most effective and efficient use of DNA and fingerprint databases to support the purposes laid down in the legislation (and no other), these are

- the interests of national security

- terrorist investigations

- the prevention and detection of crime

- the investigation of an offence or the conduct of a prosecution

- the identification of a deceased person

- the public is aware of the governance, capability and limitations of the NDNAD and fingerprint databases so that confidence is maintained in its use across all communities

The Biometrics and Forensics Ethics Group

The Biometrics and Forensics Ethics Group (BFEG)[footnote 11], which replaced the National DNA Database Ethics group in 2017, provides independent expert advice to Home Office ministers on ethical issues related to the use of biometrics, forensics, and large data sets.

The remit of the group includes consideration of the ethical impact on society, groups, and individuals, of the capture, retention and use of human samples and biometric identifiers. This includes DNA and fingerprints, as well as facial recognition and other biometric identifiers.

Current work streams for the BFEG include:

- Support policy development regarding the governance of powerful data driven technologies in the Home Office.

- Provide advice on the ethical issues in the use of novel biometric technologies, including gait and voice recognition.

- Support for the Home Office Biometrics (HOB) programme.

- Provision of advice on Home Office projects using advanced data processing techniques and/or large and complex datasets.

- Advice on policy relating to the digitisation of the services in the border, immigration, and citizenship system.

The group also provides support and advice on ethical matters to other stakeholders such as the Biometrics and Surveillance Camera Commissioner and the Forensic Science Regulator.

In addition, the Chair of BFEG, or designated delegate, sits on the Forensic Information Databases Strategy Board and provides advice in areas such as:

- Policy regarding the retention of biometrics from convicted individuals;

- Governance and ethical operation of police databases containing biometric information;

- Policy on access to and use of the Forensic Information Databases and other matters relating to the management, operation, and use of biometric or forensic data;

- The ethical application and operation of technologies which produce biometric and forensic data and identifiers;

- Ethical issues relating to scientific services provided to the police service and other public bodies within the criminal justice system;

- Review of applications for research involving access to biometric or forensic data;

- Review of the annual report from the FIND Strategy Board and other policy and consultation documents prepared by the Home Office.

1. The National DNA Database (NDNAD)

1.1 DNA profile records

NDNAD holds two types of DNA profile:

i. Individuals

The police can take a ‘DNA sample’ from every individual that they arrest for a recordable offence. This consists of their entire genome (the genetic material that every individual has in each of the cells of their body) and is usually taken by swabbing the inside of the cheek to collect some cells. The sample is then sent to an accredited laboratory, known as a ‘Forensic Service Provider’ (FSP), which looks at discrete areas of the genome (which represent only a tiny fraction of that individual’s DNA) plus the sex chromosomes (XX for women and XY for men[footnote 12]). A ‘subject’ profile is then produced consisting of 16 pairs of numbers (which correspond to the 16 areas within a person’s DNA which are analysed) and a sex marker derived from the sex chromosomes. In unrelated individuals; the chance of two unrelated people having identical profile records is less than one in a billion[footnote 13].

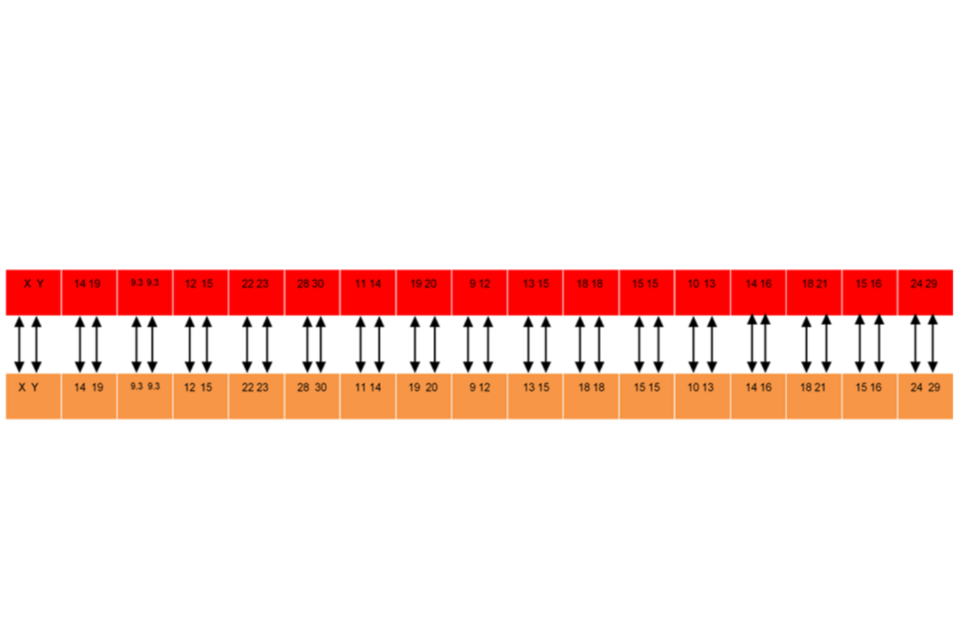

An example profile would be:

X,Y; 14,19; 9.3,9.3; 12,15; 22,23; 28,30; 11,14; 19,20; 9,12; 13,15; 18,18; 15,15; 10,13; 14,16; 18,21; 15,16; 24,29

The DNA profile is loaded to NDNAD where it can be searched against DNA profile records recovered from crime scenes.

ii. Crime scenes

DNA is recovered from crime scenes by police Crime Scene Investigators (CSIs). Nearly every cell in an individual’s body contains a complete copy of their DNA so there are many ways in which an offender may leave their DNA behind at a crime scene (for example, in blood or skin cells left on clothing or surfaces) or by touching a surface. CSIs examine places where the perpetrator of the crime is most likely to have left traces of their DNA behind. Items likely to contain traces of DNA are sent to an accredited laboratory for analysis. If the laboratory recovers any DNA, it is likely to produce a crime DNA profile which can be loaded to NDNAD.

1.2 Matches

In NDNAD searches the DNA profile records from crime scenes are searched against the DNA profile records from individuals or other crime scenes. A full match occurs when the 16 pairs of numbers (and sex marker) representing an individual’s DNA profile are an exact match to those in the DNA left at the crime scene or when a crime scene profile matches another crime scene profile.

i. Full match

The diagram below illustrates a match between a subject profile (top row) and a crime scene profile (bottom row).

Where a match is made, this indicates that the individual may be a suspect in the police’s investigation of the alleged crime. It may also help to identify a witness or eliminate other people from the police investigation.

ii. Partial match

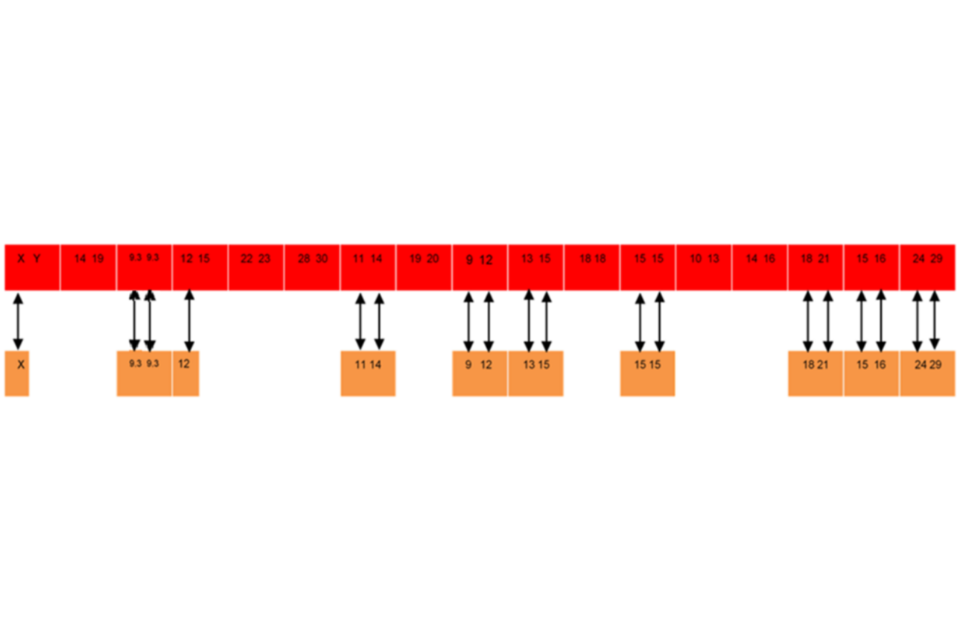

Sometimes it is not possible to recover a complete DNA profile from the crime scene; for instance, where the perpetrator has tried to remove the evidence or because it has become degraded. In these circumstances, a partial crime profile is obtained, and searched against individuals on NDNAD, producing a partial match.

The diagram below illustrates a partial match between a subject profile (top row) and a crime scene profile (bottom row).

Partial matches provide valuable leads for the police but, depending on how much of the information is missing, the result is likely to have lower evidential weight than a full match.

1.3 Familial searches

One half of an individual’s DNA profile is inherited from their father and the other half from their mother. As a result, the DNA profile records of a parent and child, or two siblings, will share a significant proportion of the 16 pairs of numbers which make up the DNA profile of the individual. This means that, in cases where the police have found the perpetrator’s DNA at the crime scene, but they do not have a profile on NDNAD, a search of the database, known as a ‘familial search’, can be carried out to look for possible close relatives (parents, children, or siblings) of the perpetrator. Such a search may produce a list of possible relatives of the offender. The police use other intelligence, such as age and geography, to narrow down the list before investigating further. The search is computerised and involves only the DNA profile records on NDNAD.

1.4 Identical siblings

The inherited nature of DNA means that identical siblings will share the same DNA profile, and the DNA profiling system currently used for NDNAD purposes cannot differentiate between identical siblings. However, even identical siblings have different fingerprints so these can be used to differentiate them. Fingerprints may be taken by the police electronically from any individual that they arrest. They are then scanned into IDENT1. Unlike DNA (where samples must be sent to a laboratory for processing) fingerprints can be loaded rapidly to IDENT1 allowing a fingerprint comparison to be undertaken and a person’s identity verified (or not) at the police station, thereby ensuring that their DNA profile and arrest details are stored against the correct record.

1.5 Ownership and access to NDNAD

Since 1st October 2012, NDNAD has been run by the Home Office on behalf of UK police forces. As at 31st March 2023, 31[footnote 14] vetted Home Office staff have access to it and there are 9 accounts which do not have direct access to the NDNAD but are used to facilitate report sending. Minimising the number of staff with direct access to the NDNAD ensures correct security measures and the highest levels of data integrity are maintained.

Police forces own the DNA profile records on the database, and receive notification of any matches, but they do not have access to it.

1.6 Security and quality control

1.6.1 Access to NDNAD

Day-to-day operation of NDNAD is the responsibility of FINDS. Data held on NDNAD are kept securely and the laboratories that provide DNA profile records to NDNAD are subject to regular assessment.

No police officer or police force has direct access to the data held on NDNAD, but they are informed of any matches it produces. Similarly, FSPs who undertake DNA profiling under contract to the police service and submit the resulting crime scene and subject profile records for loading, do not have direct access to NDNAD.

1.6.2 Compliance to international quality standards

The control and management of a forensic database service has been defined as a forensic science activity under the FSR Act 2021, but it is not subject to the FSR Statutory Code that came into force 2nd October 2023.

1.6.3 Error rates

Police forces and FSPs have put in place a number of safeguards to minimise the occurrence of errors in the sampling and processing of DNA samples and the interpretation of generated DNA profiles; FINDS carry out daily integrity checks for the DNA profile records loaded to the NDNAD. Despite these safeguards, errors do sometimes occur for samples taken from individuals and from crime scenes. The centralised DNA Contamination Elimination Database (CED), which contains the profile records of police officers and staff and people in the wider DNA process, helps to reduce errors by highlighting DNA profiles that are potentially sourced from contamination.

There are four types of errors which may occur; these are explained below:

i. Force sample or record handling error

This occurs where the DNA profile is associated with the wrong information, the source of the error in these cases could be either a physical DNA sample swap in the custody suite or the DNA record being attached to the incorrect PNC record. For example, if person A and person B are sampled at the same time, and the samples are put in the wrong bags with incorrect forms, person A’s sample would be attached to information (PNC ID number, name etc.) about person B, and vice versa. Similarly, crime scene sample C could have information associated with it which relates to crime scene sample D and vice versa. These are all errors which have occurred during the police force process. They could also relate to instances where a sample has been taken that contravenes PoFA.

ii. Forensic service provider sample or record handling error

As above, this occurs where the DNA profile is associated with the wrong information during the FSP process. Sources of this error include samples being mixed up as described above, or contamination of DNA samples during processing.

iii. Forensic service provider interpretation error

This occurs where the FSP has made an error during the analysis/interpretation of the DNA profile.

iv. FINDS (DNA) transcription or amendment error

This occurs where FINDS has introduced inaccurate information to the record on the NDNAD.

2. Forensic Science Regulator

The aim of forensic science regulation is to ensure that accurate and reliable scientific evidence is used in criminal investigations, in criminal trials, and to minimise the risk of a quality failure. It is with this broad and strategic aim in mind that the Forensic Science Regulator’s Code of Practice (Code) was developed. The Code was consulted on, approved by both Houses of Parliament in February 2023 and came into force on the 2nd October 2023.

The model for regulation of forensic science in England and Wales is based on each forensic unit implementing and operating effective quality management that meets the requirements of the Code. During consultation, a total of 110 responses with almost 3000 comments were received from a range of organisations and sectors: Law Enforcement, Academia, Commercial Providers, Judiciary, members of the public and emergency and response services. 83% supported the regulatory model for forensic science described in the statutory Code.

The statutory Code of Practice is structured as follows:

- Part A Legal position – elaborates on the Forensic Science Regulator Act 2021.

- Part B The Code – introduces the application of the Code.

- Part C Standards of conduct – sets out for all practitioners carrying out any forensic science activity (FSA) to which this Code applies, the values and ideals the profession stands for.

- Part D Standards of practice – sets out the standards of practice required of all forensic units undertaking an FSA to which this Code applies.

- Part E Infrequently commissioned experts – sets out the expectations of experts from outside the forensic science profession who are called to give evidence in relation to an FSA from time to time.

- Part F FSA definitions – defines 36 FSAs and sets out requirements for these and defines 15 FSAs without any requirement set.

A comprehensive picture is being built on the numbers and compliance levels of organisations who are undertaking forensic science activities that are subject to the Code of Practice. This will be the basis for understanding the risks to investigations of crime and the Criminal Justice System and therefore taking compliance and enforcement action. Regulatory actions will be proportionate and based on escalation with the powers in the Act being used in general as a last resort.

3. National Fingerprint Database

3.1 Who runs IDENT1?

Since 2012 IDENT1 has been operated by the Home Office. LEAs have direct access to the system, and they own the data they enrol within it.

The Home Office is responsible for assuring the quality and integrity of policing data held on IDENT1. To discharge this function, FINDS identify and correct data errors and unexpected results on IDENT1. The activities of the agencies that provide the inputs to the fingerprint database and its supply chain are monitored by FINDS and included in the FINDS performance monitoring framework and data assurance strategy.

3.2 Access to IDENT1

The number of IDENT1 active users was 908 as at 31st March 2024. (Of those, the number of IDENT1 active users from FINDS was 12). Fingerprints are captured electronically on a device called Livescan and electronically transmitted to the fingerprint database for searching. The number of active Livescan accounts was 2630 as at 31st March 20234. FINDS do not have active Livescan accounts.

3.3 Fingerprint records

The skin surface found on the underside of the fingers, palms of the hands and soles of the feet is different to skin on any other part of the body. It is made up of a series of lines known as ridges and furrows and this is called friction ridge detail[footnote 15].

The ridges and furrows are created during foetal development in the womb and even in identical siblings the friction ridge development is different. It is generally accepted that sufficient friction ridge detail is unique to each individual, although this cannot be definitively proved[footnote 16].

Located at intervals along the top of the ridges are pores which secrete sweat. When an area of friction ridge detail comes into contact with a receptive surface, an impression of the friction ridge detail, formed by sweat residue, may be deposited on that surface.[footnote 17] Visible impressions may also be made by contact of friction ridge skin with contaminants such as paint, blood, ink, or grease[footnote 18].

The analysis of friction ridge detail is commonly known as fingerprint examination[footnote 19].

Friction ridge detail persists throughout the life of the individual without change, unless affected by an injury causing permanent damage to the regenerative layer of the skin (dermis) for example, a scar. The high degree of variability between individuals coupled with the persistence of the friction ridge detail throughout life allows it to be used for identification purposes and provides a basis for fingerprint comparison as evidence.[footnote 20]

The national fingerprint database holds two types of fingerprint record:

i. Individuals

UK Law Enforcement Agencies routinely take a set of fingerprints from all persons they arrest.

Fingerprints are usually obtained electronically on a fingerprint scanning device but are occasionally obtained by applying a black ink to the friction ridge skin and an impression recorded on a paper fingerprint form.

A set of fingerprints is known as a Tenprint and comprises:

- impressions of the fingertips taken by rolling each finger from edge to edge

- an impression of all 4 fingers taken simultaneously for each hand and both thumbs

- impressions of the ridge detail present on both palms

ii. Crime scenes

CSIs examine surfaces which the perpetrator of the crime is most likely to have touched and use a range of techniques to develop latent (not visible) fingermarks to make them visible. Fingermarks developed and recovered from crime scenes are searched against the Tenprints obtained from arrested persons to identify who touched the surface the fingermarks were recovered from. Latent marks can also be developed by subjecting items (exhibits) potentially touched by the perpetrator through a series of chemical processes in an accredited laboratory by sufficiently trained and competent laboratory staff.

3.4 Fingerprint matches

Fingerprint examination is a long-established forensic discipline and has been used within the Criminal Justice System in the UK since 1902. It is based on the comparison of friction ridge detail of the skin from fingers and palms.[footnote 21]

The comparison of fingerprints is a subjective cognitive process that relies on the competence of the practitioners to perform examinations and form conclusions based on their observations and findings. The results following an examination are communicated in the form of an opinion and not a statement of fact.[footnote 22]

i. Fingerprint examination

The purpose of fingerprint examination is to compare two areas of friction ridge detail to determine whether they were made by the same person or not.[footnote 23]

The declared outcomes of a fingerprint comparison process rely on the observations and evaluation of a competent fingerprint practitioner. The practitioner gives an opinion based on their observations, it is not a statement of fact, nor is it dependent upon the number of matching ridge characteristics.[footnote 24]

The fingerprint examination process consists of stages referred to as analysis, comparison and evaluation, known as ACE. These stages are descriptors of the process undertaken by the practitioners in determining their conclusions. Although the process sets out the stages sequentially, it is not a strictly linear process. ACE can be followed by a verification stage (and the process called ACE-V). Verification is conducted by another practitioner using the ACE examination process to review the original conclusion and the examination records made by a previous examiner.[footnote 25]

There are four possible outcomes that will be reported from a fingerprint examination Insufficient, Identified, Excluded or Inconclusive.[footnote 26]

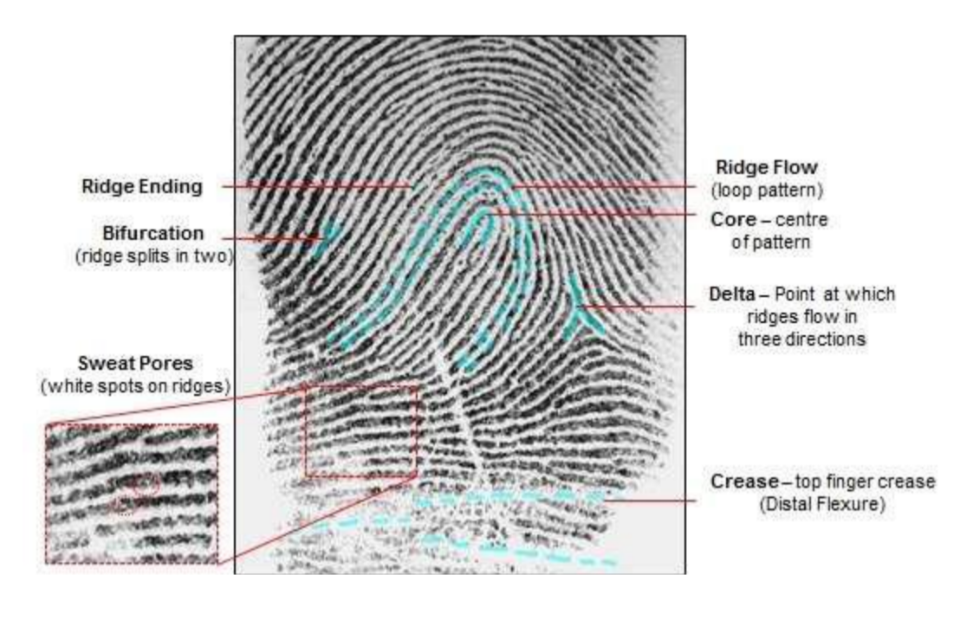

a) Analysis

The fingerprint practitioner conducts an examination of the general ridge flow of an impression and the shapes or patterns formed by the ridges. They observe the location of the naturally occurring deviations within the ridge flow which form features or characteristics, such as ridge endings and bifurcations. The fingerprint practitioner evaluates the quality and quantity of the ridge flow together with the features and the specificity of the characteristics to determine its suitability for further examination.

Image courtesy of Lisa J Hall, Metropolitan Police Forensic Science Services; permission to reproduce granted.

With the above figure, friction ridge detail is observable at the top of a finger. The black lines are the ridges, and the white spaces are the furrows. The ridges flow to form shapes or patterns. This is an example of a loop pattern exiting to the left. There are natural deviations within the ridge flow known as characteristics such as ridge endings or forks/bifurcation. There are white spots along the tops of the ridges known as pores and there are other features present for example creases, which are normally observed as white lines.[footnote 27]

Using a holistic approach to review the detail observed within the mark and other external variables for example, the surface on which the mark was left or any apparent distortion, the fingerprint practitioner establishes whether they can progress the examination and comparison process. [footnote 28]

b) Comparison

The fingerprint practitioner will systematically compare two areas of friction ridge detail, for example one area from a fingermark against one from a fingerprint. This process generally consists of a side-by-side comparison to determine whether there is agreement or disagreement between the ridge flow, features and characteristics. The fingerprint practitioner examines the features on the fingermark first to minimise bias.

The fingerprint practitioner compares the type, specificity, sequence, and spatial relationship of all the observed ridge characteristics, whilst considering the tolerance(s) they have allowed, based on their experience, for any issues relating to clarity or distortion of the ridge detail.

The fingerprint practitioner will establish an opinion as to the level of agreement or disagreement between the sequences of ridge characteristics and features visible in both the fingermark and fingerprint.[footnote 29]

c) Evaluation

The practitioner will review all of their previous observations and come to a final opinion and conclusion about the outcome of the examination process undertaken.[footnote 30]

The outcomes determined from the examination will be one of the following:[footnote 31]

Identified: A practitioner term used to describe the mark as being attributed to a particular individual.

Excluded: There are sufficient features in disagreement to conclude that two areas of friction ridge detail did not originate from the same person.

Inconclusive: The practitioner determines the level of agreement and / or disagreement is such that, it is not possible to conclude that the areas of friction ridge detail originated from the same donor, or exclude that particular individual as a source for the unknown friction ridge detail.

Insufficient: The ridge flow and / or ridge characteristics revealed in the area of friction ridge detail are of such low quantity and/or poor quality that a reliable comparison cannot be made.

d) Verification

This is the process to demonstrate whether the same outcome is obtained by another competent fingerprint practitioner or fingerprint practitioners who conduct an independent analysis, comparison and evaluation, thereby confirming the original outcome.[footnote 32]

4. Legislation governing DNA and fingerprint retention

4.1 Overview

For England and Wales the Protection of Freedoms Act 2012 (PoFA) and subsequent Acts[footnote 33] amended Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE) to establish the current retention framework for DNA and fingerprints. The NDNAD also contains profiles from Scotland and Northern Ireland.

The enabling legislation for Scotland is:

-

Part 2 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995

-

Section 56 of the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2003 [voluntary samples]

-

Chapter 4 of Part 4 of the Age of Criminal Responsibility (Scotland) Act 2019

The enabling legislation for Northern Ireland is:

- Police and Criminal Evidence (Northern Ireland) Order 1989 (PACE NI)

4.2 Protection of Freedoms Act 2012

4.2.1 Introduction

PoFA includes detailed rules on how long the police may retain an individual’s DNA sample, profile and fingerprints.

4.2.2 DNA profile records and fingerprints

Depending on the circumstances, a DNA profile and fingerprint record may be retained indefinitely, held for three to five years and then destroyed, or destroyed immediately.

4.2.3 DNA samples

PoFA requires all DNA samples taken from individuals to be destroyed as soon as a profile has been obtained from them (or in any case within 6 months) unless it is retained under the Criminal Procedure and Investigations Act 1996 (CPIA)[footnote 34]. This allows sufficient time for the sample to be analysed and a DNA profile to be produced and uploaded to NDNAD.

4.3 Biometrics and Surveillance Camera Commissioner

PoFA also established the position of Commissioner for the Retention and Use of Biometric Material (‘the ‘Biometrics Commissioner’)[footnote 35]. The position is independent of Government. As at 31st March 2024, the Biometrics and Surveillance Camera Commissioner was Tony Eastaugh, he stepped down from this post in mid-August 2024.

As indicated in Table 1b, one of the Biometrics and Surveillance Camera Commissioner’s functions is to decide whether or not the police may retain DNA profile records and fingerprints obtained from individuals arrested but not charged with a qualifying offence. They also have a general responsibility to keep the retention and use of DNA and fingerprints, and retention on national security grounds, under review.

4.4 Scottish Biometrics Commissioner

The Scottish Biometrics Commissioner Act 2020 established the office of the Scottish Biometric Commissioner and the role of the Scottish Biometrics Commissioner in exercising independent oversight of biometric data used for policing and criminal justice purposes in Scotland.[footnote 36] At the time of writing the Scottish biometric commissioner is Dr Brian Plastow.

4.5 Extensions

Where an individual has been arrested or charged with a qualifying offence and an initial three-year period of retention has been granted, PoFA allows a chief constable to apply to a district judge for a two-year extension of the retention period. This can be applied in specific circumstances, such as; the victim is under 18, the victim is a vulnerable adult the victim is associated with the person to whom the retained material relates or if they consider retention to be necessary for the prevention or detection of crime.

4.6 Speculative searches

PoFA allows the DNA profile and fingerprints taken from arrested individuals to be searched against NDNAD and IDENT1, to see if they match any subject or crime scene profile already stored. Unless a match is found, or PoFA provides another power to retain them (for example because the person has a previous conviction) the DNA and fingerprints are deleted once the ‘speculative search’ has been completed. If there is a match the police will decide whether to investigate the individual or not.

Table 1a: Retention periods[footnote 37] for convicted individuals

| Situation | Fingerprint & DNA Retention Period |

|---|---|

| Any age convicted (including given a caution or youth caution) of a qualifying offence | Indefinite |

| Adult convicted (including given a caution) of a minor offence | Indefinite |

| Under 18 convicted (including given a youth caution) of a minor offence | 1st conviction: five years (plus length of any prison sentence), or indefinite if the prison sentence is for five years or more. 2nd conviction: indefinite |

Table 1b: Retention periods[footnote 38] for non-convicted individuals

| Situation | Fingerprint & DNA Retention Period |

|---|---|

| Any age charged with but not convicted of a qualifying[footnote 39] offence | Three years plus a two-year extension if granted by a District Judge (or indefinite if the individual has a previous conviction for a recordable[footnote 40] offence which is not excluded) |

| Any age arrested for but not charged with a qualifying offence | Three years if granted by the Biometrics and Surveillance Camera Commissioner plus a two-year extension if granted by a District Judge (or indefinite if the individual has a previous conviction[footnote 41] for a recordable offence which is not excluded[footnote 42]) |

| Any age arrested for or charged with a minor[footnote 43] offence | None (or indefinite if the individual has a previous conviction for a recordable offence which is not excluded) |

| Over 18 given a Penalty Notice for Disorder | Two years |

4.3 Early deletion

PoFA requires the FIND Strategy Board to issue guidance about the destruction of DNA profile records[footnote 44]. Guidance, known as the ‘Deletion of Records from National Police Systems’, covering DNA profile records and samples, fingerprints and PNC records was first published in May 2015[footnote 45]. The guidance is only statutory in relation to DNA profile records and only applies to those individuals:

- with no prior convictions, whose biometric material is held because they have been given a Penalty Notice for Disorder;

- who have been charged with, but not convicted of, a qualifying offence; or

- who receive a simple or conditional caution.

The guidance states that Chief Officers may wish to consider early deletion if applied for on specified grounds. These include:

- a recordable offence has not taken place (e.g. where an individual died but it has been established that they died of natural causes);

- the investigation was based on a malicious or false allegation;

- the arrested individual has a proven alibi;

- the status of the individual (e.g. as victim, offender, or witness) is not clear at the time of arrest;

- a magistrate or judge recommends it;

- another individual is convicted of the offence; and

- where it is in the public interest to do so.

The Record Deletion Process provides guidance and an application form[footnote 45] which specifies the evidence that the Chief Officer should consider, this application form is available on GOV.uk.

Glossary

Accreditation

This is the independent assessment of the services that an organisation delivers, to determine whether they meet defined standards. Forensic Service Providers and laboratories which process DNA samples and fingerprints are required to be accredited to ISO/IEC 17025; a standard set out by the International Standard Organisation which requires that samples are processed under appropriate laboratory conditions and that contamination is avoided.

Biometrics and Forensics Ethics Group[footnote 46]

The DNA Ethics Group was established in 2007 and in July 2017 it was replaced by the Biometrics and Forensics Ethics Group.

Biometrics and Surveillance Camera Commissioner (‘the Biometrics Commissioner’)

The Biometrics Commissioner is responsible for keeping under review the retention and use by the police of DNA samples, DNA profile records and fingerprints; and for agreeing or rejecting applications by the police to retain DNA profile records and fingerprints from persons arrested for qualifying offences but not charged or convicted for up to three years.

Contamination Elimination Database

A database held within FINDS containing reference profile records from individuals who work within the DNA supply chain, such as police officers, police staff, manufacturers and others who come into regular contact with crime scenes or evidence, so that any DNA inadvertently left at a crime scene can be eliminated from the investigation.

Crime scene investigator (CSI)

A member of police staff employed to collect samples which may contain DNA and other forensic evidence left at a crime scene.

Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA)

Genetic material contained within most of the cells of the human body which determines an individual’s characteristics such as sex, eye colour, hair colour etc.

DNA-17

The current method used to process a DNA sample in the UK which analyses a sample of DNA at 16 different areas plus a sex marker.

DNA profile

A series of pairs of numbers (16 pairs where the DNA-17 method is used) plus a sex marker which are derived following the processing of a DNA sample. There are two types of DNA profile records:

- crime scene DNA profile: this is a DNA profile derived from a crime scene sample

- subject DNA profile: this is a DNA profile derived from a subject sample

Once derived, DNA profile records are usually loaded onto the National DNA Database. See ‘DNA sample’.

DNA sample

There are two main types of DNA sample:

- crime scene sample: this is a sample of DNA taken from a crime scene e.g. from a surface, clothing or bodily fluid (such as blood) left at a crime scene.

- subject sample: this is a sample of DNA taken from an individual, often from their cheek, by way of a ‘buccal swab’ though it can be taken from hair or a bodily fluid such as blood, urine or semen.

In the case of missing persons, DNA samples may also be taken from the belongings of that person or their family for the purposes of identifying a body should one be found.

Early deletion

The Record Deletion Guidance sets out certain, limited, circumstances under which an individual whose DNA profile is being retained by the police can apply to have it destroyed sooner than normal.

Excluded offence

Under the retention framework for DNA and fingerprints, an ‘excluded’ offence is a recordable offence which is minor, was committed when the individual was under 18, for which they received a sentence of fewer than five years imprisonment and is the only recordable offence for which the individual has been convicted.

Familial search

A search of NDNAD to look for relatives of the perpetrator carried out where DNA is found at a crime scene but there is no subject profile on NDNAD. Such a search may produce a list of possible relatives of the offender. The police use other intelligence, such as age and geography, to narrow down the list before investigating further. Because of the privacy issues, cost and staffing involved in familial searches, they are only used for the most serious crimes. All such searches require the approval by the Chair of the FIND Strategy Board (or a nominee of the Chair).

FINDS transcription or amendment error

This occurs where FINDS have introduced inaccurate information.

Force sample or record handling error

This occurs where the DNA profile is associated with the wrong information. For example, if person A and person B are sampled at the same time, and the samples are put in the wrong kits, so person A’s sample is attached to information (PNC ID number, name etc.) about person B, and vice versa. Similarly, crime scene sample C could have information associated with it which relates to crime scene sample D.

Forensic Archive Ltd. (FAL)

A company established following the closure of the Forensic Science Service (FSS), to manage case files from investigation work which it had carried out. (The FSS was the body which used to have responsibility for most forensic science testing in relation to forensic evidence).

In March 2012, the FSS closed, and its work was transferred to private Forensic Service Providers and in-house police laboratories.

Forensic Information Database Service (FINDS)

The Home Office Unit responsible for administering NDNAD, Fingerprint Database and Footwear database.

Forensic Information Databases (FIND) Strategy Board

The FIND Strategy Board provides governance and oversight over NDNAD and the Fingerprint Database. It has a number of statutory functions including issuing guidance on the destruction of profile records and producing an annual report.

Forensic Service Provider (FSP)

An organisation which provides forensic analysis services for the criminal justice system.

FSP interpretation error

This occurs where the FSP has made an error during the processing of the sample.

FSP sample and/or record handling error

As above, this occurs where the DNA profile is associated with the wrong information. It could involve samples being mixed up as described above or contaminating DNA being introduced during processing.

Forensic Science Regulator (FSR)[footnote 47]

Responsible for ensuring that the provision of forensic science services across the criminal justice system in England and Wales is subject to an appropriate regime of scientific quality standards. The Scottish and Northern Irish authorities collaborate with the FSR in the setting of quality standards.

Law Enforcement Agencies (LEAs)

Any organisation authorised to take samples under PACE.

Match

There are three types of matches:

- crime scene to subject: Where a crime scene DNA profile matches a subject DNA profile

- crime scene to crime scene: Where a crime scene DNA profile matches another crime scene DNA profile (i.e. indicating that the same individual was present at both crime scenes).

- subject to subject: Where a subject profile matches a subject profile already held on NDNAD (i.e. indicating that the individual already has a profile on NDNAD).

Match rate

The percentage of crime scene DNA profile records which, once loaded onto NDNAD, match against a subject DNA profile (or subject DNA profile records which match to crime scene DNA profile records).

Minor offence

Under the retention framework for DNA and fingerprints, a minor offence is a ‘recordable’ offence which is not a ‘qualifying’ offence.

Missing Persons DNA Database (MPDD)

The MPDD holds DNA profile records obtained from the belongings of people who have gone missing or from their close relatives (who will have similar DNA). If an unidentified body is found DNA can be taken from it and run against that on the MPDD to see if there is a match. This assists with police investigations and helps to bring closure for the family of the missing person. DNA profile records on the MPDD are not held on NDNAD.

National DNA Database (NDNAD)

A database containing both subject and crime scene DNA profile records connected with crimes committed throughout the United Kingdom. (Subject DNA profile records retained on the Scottish and Northern Irish DNA Databases are copied to NDNAD; crime scene DNA profile records retained on those databases are copied to NDNAD if a match is not found).

Non-Routine search

A search made against a DNA profile which has not been uploaded onto NDNAD.

Partial match

Where, for instance, the perpetrator has tried to remove the evidence, or DNA has been partially destroyed by environmental conditions, it may not be possible to obtain a complete DNA profile from a crime scene. A partial DNA profile can still be used to obtain a partial match against profile records on NDNAD. Partial matches provide valuable leads for the police but, depending on how much of the information is missing, the result is likely to be interpreted with lower evidential weight than a full match. See ‘Match’.

Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE)

PACE makes a number of provisions to do with police powers, including in relation to the taking and retention of DNA and fingerprints.

Protection of Freedoms Act 2012 (PoFA)

Prior to coming into force for the DNA and fingerprint sections of PoFA on 31st October 2013, DNA and fingerprints from all individuals arrested for, charged with or convicted of a recordable offence were held indefinitely. PoFA amended PACE to introduce a much more restricted retention schedule under which the majority of profile records belonging to innocent people were destroyed. See ‘Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE)’.

Qualifying offence

Under the retention framework for DNA and fingerprints, a ‘qualifying’ offence is one listed under section 65A of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (the list comprises sexual, violent, terrorism and burglary offences).

Recordable offence

A ‘recordable’ offence is one for which the police are required to keep a record. Generally speaking, these are imprisonable offences; however, it also includes a number of non-imprisonable offences such as begging and taxi touting. The police are not able to take or retain the DNA or fingerprints of an individual who is arrested for an offence which is not recordable.

Routine search

A search made against a DNA profile uploaded onto NDNAD.

SGMPlus

The previous method used to process a DNA sample which analysed a sample of DNA at ten different areas plus a sex marker. In July 2014, SGMPlus was upgraded to DNA-17.

Urgent match

A search made using FINDS’ urgent speculative search service which is available 24 hours a day. This service is reserved for the most serious of crimes.

Y-STR

Y-STR analysis is a method which can be used when processing complex casework samples to aid the detection of male DNA where there may be trace amounts, in the presence of high levels of female DNA (for example in sexual offences and violent crime). Y-STRs are taken specifically from the male Y chromosome and are transmitted along the paternal lineage. Due to the nature of this analysis, Y-STR is often used in paternity and genealogical DNA testing and can also be used to identify missing persons and familial searches.

Full revision history

| Issue number | Issue date | Summary of changes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 28/03/2024 | New document |

| 2 | 13/02/2025 | DCR1358: Minor updates |

-

As set out under section 3 of the governance rules. ↩

-

Section 63AB of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE) ↩

-

Section 63AB(2), Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984. ↩

-

Ibid 2, section 63G. ↩

-

Ibid 2, section 63AB(4). ↩

-

The Biometrics Commissioner’s latest annual report is available at: Biometrics and Surveillance Camera Commissioner: report 2023 to 2024 ↩

-

Ibid 2, section 63AB(6). ↩

-

Ibid 2, section 63AB(7). ↩

-

The governance rules are published at: Forensic Information Databases strategy board: revised governance rules. ↩

-

As set out under section 4 of the governance rules. ↩

-

https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/biometrics-and-forensics-ethics-group ↩

-

An individual’s DNA is contained within discrete structures within a cell known as chromosomes. Men have a copy of an X and Y chromosome whereas women have two copies of the X chromosome. ↩

-

As agreed with the Forensic Science Regulator and the Crown Prosecution Service, in order to give a conservative figure, routine statistical reporting of DNA evidence in court continues to be reported as ‘one in a billion’. Certain cases might be reported with a more precise probability; this is assessed on a case-by-case basis. ↩

-

This is as at 31/03/24. ↩

-

Cited from Forensic Science Regulator Codes – Fingerprint Comparison FSR-C-128 25.4.1 ↩

-

Cited from Forensic Science Regulator Codes – Fingerprint Comparison FSR-C-128 25.4.2 ↩

-

Cited from Forensic Science Regulator Codes – Fingerprint Comparison FSR-C-128 25.4.3 ↩

-

Cited from Forensic Science Regulator Codes – Fingerprint Comparison FSR-C-128 25.4.4 ↩

-

Cited from Forensic Science Regulator Codes – Fingerprint Comparison FSR-C-128 25.5.6 ↩

-

Cited from Forensic Science Regulator Codes – Fingerprint Comparison FSR-C-128 25.5.1 ↩

-

Cited from Forensic Science Regulator Codes – Fingerprint Comparison FSR-C-128 25.3.1 ↩

-

Cited from Forensic Science Regulator Codes – Fingerprint Comparison FSR-C-128 25.3.2 ↩

-

Cited from Forensic Science Regulator Codes – Fingerprint Comparison FSR-C-128 25.6.1 ↩

-

Cited from Forensic Science Regulator Codes – Fingerprint Comparison FSR-C-128 25.6.4 ↩

-

Cited from Forensic Science Regulator Codes – Fingerprint Comparison FSR-C-128 25.7.1 ↩

-

Cited from Forensic Science Regulator Codes – Fingerprint Comparison FSR-C-128 25.7.2 ↩

-

Cited from Forensic Science Regulator Codes – Fingerprint Comparison FSR-C-128 25.7.3 ↩

-

Cited from Forensic Science Regulator Codes – Fingerprint Comparison FSR-C-128 25.8.1 ↩

-

Cited from Forensic Science Regulator Codes – Fingerprint Comparison FSR-C-128 25.9.1 ↩

-

Cited from Forensic Science Regulator Codes – Fingerprint Comparison FSR-C-128 25.10.1 ↩

-

Cited from Forensic Science Regulator Codes – Fingerprint Comparison FSR-C-128 25.11 ↩

-

Cited from Forensic Science Regulator Codes – Fingerprint Comparison FSR-C-128 25.12.1 ↩

-

Detailed in The Forensic Information Databases Strategy Board Policy for Access and Use of DNA Samples, DNA Profiles, Fingerprint Images, Custody Images, and Associated Data ↩

-

Under the Criminal Procedure and Investigations Act 1996 (CPIA) (and its associated code of practice) evidence can be retained where it may be needed for disclosure to the defence. This means that, in complex cases, a DNA sample may be retained for longer. This sample can only be used only in relation to that particular offence and must be destroyed once its potential need for use as evidence has ended. ↩

-

For more information on the work of the Biometrics Commissioner see https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/biometrics-commissioner. ↩

-

Scottish Biometrics Commissioner Act 2020 (legislation.gov.uk) ↩

-

Relates to the retention regimes in England and Wales only. ↩

-

Relates to the retention regimes in England and Wales only. ↩

-

A ‘qualifying’ offence is one listed under section 65A of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (the list includes sexual, violent, terrorism and burglary offences). ↩

-

A ‘recordable’ offence is one for which the police are required to keep a record. Generally speaking, these are imprisonable offences; however, it also includes a number of non-imprisonable offences such as begging and taxi touting. The police are not able to take or retain the DNA or fingerprints of an individual who is arrested for an offence which is not recordable. ↩

-

Convictions include cautions, reprimands and final warnings. ↩

-

An ‘excluded’ offence is a recordable offence which is minor, was committed when the individual was under 18, for which they received a sentence of fewer than 5 years imprisonment and is the only recordable offence for which the individual has been convicted. ↩

-

As set out under section 63AB(4) of the Police and Criminal Evidence act 1984 (PACE) as inserted by section 24 of PoFA. ↩

-

Deletion of Records from National Police Systems guidance is available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/dna-early-deletion-guidance-and-application-form ↩

-

Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/dna-early-deletion-guidance-and-application-form. ↩ ↩2

-

https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/biometrics-and-forensics-ethics-group ↩

-

https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/forensic-science-regulator ↩