Fraud and error deterrence/prevention message testing

Published 28 March 2019

Executive Summary

This research with Universal Credit (UC) and Pension Credit (PC) claimants used a mixture of qualitative methods including 10 small focus groups, 3 paired depth interviews and 15 one-to-one depth interviews, involving a total of 64 individuals to gauge their responses to and reflections on a variety of test messages aiming to: heighten claimants’ perceptions of the risks associated with committing benefit fraud; raise their awareness of some of DWP’s detection methods; communicate the potential penalties for fraud; and offer clearer and more user-friendly support/ guidance to help claimants avoid being overpaid or underpaid. The aim was to identify messages which could better engage and inform claimants, and discourage all forms of non-compliant behaviour including benefit fraud.

Some interesting themes were identified in terms of how to foster mutual respect between claimants and DWP, and how helpful reminders of changes of circumstances might be combined with messages about the potential penalties for fraud. The findings offer fresh insights into why some messages may provoke a negative emotional response that leads to them being poorly received or ignored by the very claimants they are intended to reach.

By themselves, warnings about penalties often provoked fearful responses. Although some claimants responded to these out of fear and a desire not to be dishonest, others did not feel encouraged to take a measured and thoughtful approach to the information or instructions being supplied. In contrast, clear objective reminders to report changes of circumstances were welcomed as helpful nudges. There is a role for more frequent nudges about the changes of circumstances that need to be reported so claimants do not fall behind on reporting and then fear coming forward due to penalties or repayments.

General messages of support and help were broadly welcomed but needed to be backed up by supportive customer service from DWP in order to have credibility.

Many research participants responded negatively to messages which directly highlighted that the responsibility was on them to maintain accurate benefit claims because they felt that DWP was in control of this area of their life, and that DWP sometimes made mistakes. In this respect, the UC online portal seemed to give the small number of users in the sample a valuable sense of control over their claim, which engendered empowerment and a greater sense of responsibility, which could theoretically deliver better compliance.

The research also suggested that as part of building relationships based on mutual respect, claimants might be more willing to report all types of changes if they felt that they could trust DWP to be more open and honest about benefit entitlement criteria and assured that DWP was genuinely equally concerned about changes of circumstances which might be to claimants’ financial gain.

It is also suggested that it would be helpful to make it clear that avoidance of penalties is also DWP’s goal. Where DWP’s responsibilities and commitment to helping people in financial need were also highlighted, a more reciprocal relationship of ‘mutual trust’ could develop, which helped claimants to accept DWP communications more positively, even those about DWP’s detection techniques and potential penalties, leading potentially to more pro-active and honest management of their claims.

Probably the clearest single finding was that claimants in receipt of PC did not see themselves as benefits claimants. They viewed PC as part of their State Pension, thus any communications referring to ‘claimants’ did not resonate with them and had the potential to be ignored.

1. The research task

This chapter sets out the requirement for new research into addressing non-compliant behaviour through new messaging approaches and how the research was structured.

1.1. Background to the project

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) wished to conduct qualitative research with benefit claimants (Universal Credit and Pension Credit) to explore their reactions and responses to a set of messages designed to improve compliance with the benefit rules (specifically ensuring changes of circumstances are reported) and discourage fraudulent behaviour. The research was intended to generate insight to guide the development of future communications activities and products aimed at benefit claimants.

1.1.1. Background to the research project

In 2018 DWP developed a new Fraud, Error & Debt Strategy to reduce the level of fraud and error. As part of this strategy, DWP was looking to improve the way it communicates with benefit claimants, supporting them to manage their claims more effectively and establish new techniques to discourage fraud. To achieve this, DWP analysts and claimant communications colleagues developed phrases which, based on key points from the behaviour change (e.g. Nudge Theory) and crime and deterrence literature, may provide clearer information about benefit rules and responsibilities, and challenge unhelpful attitudes and misconceptions about DWP, the benefits system and fraud.

Drawing on the literature and evidence around penalties and deterrence, barriers to reporting changes of circumstances and lessons from previous benefit fraud communications campaigns, DWP analysts highlighted a number of possible approaches, using new messages across the communications product range (from targeted direct mail to nationwide advertising), aimed at claimants.

This research was commissioned to provide DWP with:

- evidence indicating which approaches may be most effective in discouraging undesirable behaviour and supporting claimants’ understanding of benefit rules and processes. This will form the basis of future communications activity, or further research activity which will support the development of communications activity

- findings which help to refine the themes covered in messages; with a clear explanation and justification of how particular messages appear effective with their target audience. This will provide DWP communications teams with firm, clear examples of successful messaging which can be used to engage

- an indication of how any identifiable claimant groups may respond differently to messaging, with recommendations about how to approach any groups beyond the two main UC and PC claimant groups in the sample. This was to allow DWP to tailor messaging as needed to specific groups, maximising the effectiveness of future communications in relation to reducing overpayments

1.1.2. Research objectives

The research objectives were as follows:

- understanding claimants’ comprehension of changes of circumstances that need to be updated as part of benefit claims and attitudes to reporting changes

- understanding claimants’ attitudes to DWP and experiences of DWP communications

- gauging claimants’ spontaneous and considered reactions to the proposed messages in terms of impact, comprehension, communication, tone of voice and perceived targeting

- gauging the impact the messages have on claimants’ attitudes towards benefit fraud, and the reasons underlying this, exploring which ones claimants report as being more or less likely to change attitudes

- recording participants’ perceptions of how the messages would affect their future behaviour (self reported); investigating how likely claimants say they would be to consider fraudulent behaviour after seeing the messaging * understanding attitudes to different communications format and channel choices including electronic (email, text), paper and face to face

DWP analysts suggested a number of messaging themes they wished to explore through the research, identifying a long list of themes to be refined, selecting the most promising themes for testing:

- how DWP might heighten perceptions of the risks associated with committing benefit fraud

- how DWP might raise awareness of its more innovative and powerful detection methods

- how DWP might clearly communicate the potential penalties for fraud in order to maximise deterrence

- how DWP might offer clearer and more user friendly support and guidance (e.g. messaging around the role DWP advisers and work coaches as sources of help and support, or promotion of the range of sources of information available provided by DWP)

- making the benefit claim more of a priority: Communicating the fact that keeping claim details correct and up-to-date is just as important as other responsibilities (e.g. checking bank balance and paying bills)

- demonstrating the social costs of fraud and error and their financial impact on public services: Communicating what the amount of money lost in the past financial year would be able to buy: on school places, hospital beds or key workers

- encouraging potential fraudsters to ‘own the crime’: Use of language which emphasises claimant’s responsibility and fairness; and use of specific labels such as benefit cheat or benefit thief

1.1.3. Research methodology

The research used qualitative methods including 10 small group discussions (3 to 5 respondents in each), 3 paired depth interviews (2 respondents in each) and 15 one‑to-one depth interviews. The research took a staged approach to allow for stimulus amendments to be made between stage 1 and stage 2 and for the recruitment of stage 2 to focus on the audiences of greatest interest emerging from stage 1. Follow up telephone calls were also conducted with a selection of respondents who were happy to be re-contacted and during this telephone call their views on the research session and any messages they felt had made an impact were discussed.

Qualitative research is an open and discursive method which explores responses to the project objective areas. A qualitative methodology allows for an in-depth examination of attitudes and in this project, how they can be influenced through external stimulus. Qualitative samples are purposive and quota driven in nature; they are designed to reflect the range of audiences of interest to a study. They therefore do not have quantitative accuracy in terms of identifying proportions of populations holding stated views. For these methodological reasons, it is not appropriate to present qualitative findings in terms of the numbers of respondents expressing certain views.

This research project was carried out according to the Market Research Society’s Code of Conduct and Ethics. The Code of Conduct was applied to all areas of the project. It covered all aspects of recruitment, including the screening questionnaire, ensuring that respondents gave fully informed consent. Respondents were made aware of the purpose of the project in advance, at recruitment and before the start of the research session.

Respondents were recruited to take part in the research by professional market research recruiters using a screening questionnaire which had been agreed with DWP. At the start of each research session, it was explained to participants that their details and responses were fully anonymous and confidential and that no personal details would be passed to DWP. It was further explained that they could refuse to answer any questions if they chose and could terminate the interview at any point.

A pack of stimulus was developed by DWP prior to the research fieldwork this included a range of messaging statements. As the research took an iterative approach, the pack of stimulus was updated during the fieldwork allowing for key learnings to be actioned.

1.1.4. Target groups

Universal Credit claimants were targeted because claimants of this benefit will be the main working age claimant group in the future. The majority of remaining claimants will be of pension age; Pension Credit claimants specifically, represent a major source of loss due to fraud and error. It is therefore essential that all future DWP communications resonate with both groups of claimants.

1.1.5. Sample structure

The sample focused specifically on respondents who were assessed as being prone to experiencing problems with their claim because these were the types of claimant DWP wanted to target with better communications.

The sample overall was weighted towards respondents who had previously experienced some form of problem with their claim including overpayments, and was drawn mainly from DWP lists. Free found recruitment was also used to boost the overall sample, creating a sub-sample of participants who were either Pension Credit or Universal Credit claimants and who fitted the profile attitudinally. The sample was therefore purposefully not representative of the entire benefits, Pension Credit or Universal Credit claimant population.

The sample structure for the research is outlined below:

Stage 1

- 30 x Universal Credit (either current or past) claimants in a mix of small groups, pairs and depths

- spread across age or life stage

- pre-family without children aged 18 to 30

- family with children living at home aged 24 to 45

- empty nesters without children at home aged 45 to 64

- including unemployed and employed respondents, biased to those who were unemployed

- mostly single claimants, a small number of joint claimants

- mix of male and female

- either currently or previously on Universal Credit

- spread across age or life stage

- 25 x Pension Credit claimants in a mix of small groups, pairs and depths

- all aged 65 to 80

- mix of male and female

- mostly not working, although some working as well or looking to work

Stage 2

- depth or paired depth interviews with 9 Universal Credit (current or past) claimants

- spread across age or life stage

- biased to unemployed respondents

- mix of male and female

1.1.6. Locations

Six fieldwork locations were included in the sample across England including Northern, Midlands and Southern locations.

1.1.7. Other details

To follow is a summary of the research findings. A variety of analysis approaches were used by the research team to analyse the research materials. This included reviewing transcripts, thorough notes and audio tapes, but also considering important aspects from fieldwork such as respondent body language, emotional and cognitive engagement and the specific language patterns used, to create a holistic evaluation of the research sessions. The team developed findings using interpretive techniques and themes were developed at each stage of fieldwork so that the research process was iterative, and findings could be developed and tested out with subsequent audiences.

2. Context and understanding of changes of circumstances

This chapter describes the different typologies of claimant who participated in the research then goes on to set out the various factors identified as influencing the likelihood to make errors or be non-compliant. This sets out the mindset and context in which claimants therefore interpret messages from DWP.

2.1. Characteristics and experience of respondents

Overall the sample displayed many similarities in attitudes and beliefs but there emerged some important differences in why they had experienced problems with their claim in the past, their understanding of the benefits system and DWP’s requirements of a claimant.

Many in the sample had experienced some form of Compliance Interview [footnote 1] with DWP or problem with their benefit or pension credit claim at some point, and shared this openly within the session. Problems could be due to a variety of issues including reporting changes of circumstances, non-attendance at jobcentres or problems related to job searches.

Across both Pension Credit and Universal Credit samples, some of those who had had a problem with their claim believed that the problem was not their fault and was driven by a DWP error. Others recognised that they had made a mistake themselves and described this as a genuine error made either by them not understanding what they had to do, or by someone else acting on their behalf making a mistake.

In terms of updating changes of circumstances, some in the sample admitted to not updating their claim at times either intentionally or not intentionally, and either on an ad hoc basis, or more consistently. However, the majority of claimants in the sample did not regard this as benefit fraud and most in the sample were very critical of those that they thought were consciously defrauding the system and behaving dishonestly.

A key difference noted was that Pension Credit claimants displayed greater potential for genuine error than the Universal Credit claimants in this sample – a fact which is reflected in DWP statistics [footnote 2]. Overclaiming amongst Pension Credit claimants tended to arise because the individual had not retired to live on a pension alone, State Pension or otherwise, and some form of paid employment was still undertaken. Another cause of accidental overpayment was when private pensions were realised which affected Pension Credit entitlement, but they had not appreciated that this had to be reported to DWP.

A key influencing factor in this type of error was that Pension Credit was often not seen as a State benefit, it was seen as a top up to the State Pension that they considered owed to them by the State. In addition, there was often a poor understanding of their eligibility for Pension Credit and the factors influencing the amount they were receiving. Some Pension Credit recipients did not recall taking any action to apply for the benefit [footnote 3], and others were not clear of the list of changes of circumstance that might affect their eligibility per se, or the amount they received. This suggests that there is a need for clear information and reminders about the terms and conditions applying to Pension Credit, and the changes of circumstances that need to be reported.

“You can work with your State Pension. It’s the credit that you can’t work with…So why don’t they make these things clear.”

(Pension Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

“If I’m still being paid after I notified you, you just think it’s part of your pension… a graduated pension and I just thought it was that, topped up your pension.”

(Pension Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

Linked to these issues noted above, Pension Credit claimants did not necessarily consider messages that mentioned the word benefit or benefit claimants were aimed at them unless the message specifically mentioned Pension Credit. This suggests that there is a need to address Pension Credit claimants directly within communications or they may discount themselves.

2.2. Attitudes to and understanding of changes of circumstances

2.2.1. Understanding of changes of circumstances

Across the sample, the phrase ‘changes of circumstances’ was a commonly understood term. However, the research showed that respondents had a variable understanding of specific changes of circumstances they were required to report. This suggested that lack of knowledge and understanding amongst claimants influenced non-reporting alongside other factors.

As noted earlier, those on Pension Credit were often not clear about changes of circumstances they needed to report, specifically around ability to work and other pensions being realised. This confusion was also compounded by the small amount of the entitlement that some of them had been awarded.

Universal Credit claimants in the sample were more aware that changes of circumstances had to be reported to DWP as this might affect the amount of their entitlement. The common changes of circumstances for those on Universal Credit were well known, for example starting a new job, finishing a job, recording hours, moving home, having a baby, getting married or separated. However, respondents were not confident about the full range of changes of circumstances to be reported, with key areas of confusion including taking holidays and partners or other family members moving in and out of the claimant’s home, especially if this was a temporary change.

Although respondents recalled having to review changes of circumstances at the claimant commitment stage, they did not report being subsequently reminded of the full list of changes which meant it could be relatively easy to make a mistake as they were not always salient [footnote 4]. This lack of awareness was considered a potential problem as it could lead to accidental non-reporting.

“If you go on holiday you don’t think I’d better phone these people… You’re not consciously thinking about them at the time.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

2.2.2. Other factors affecting non-reporting

Respondents felt that they were likely to report changes of circumstances that they knew would affect their claim positively and if they thought it would lead to them receiving more money. Examples included having a baby, a partner moving out permanently, losing their job.

“A lot more people would ring if they said you may be entitled to more.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, South)

However, other than simply not being aware of what changes of circumstances they had to report, other factors were noted as influencing reporting. Respondents did not necessarily understand the significance of reporting certain changes, for example going on holiday or having someone move in with them temporarily. These types of changes were reported as feeling like a level of unnecessary detail that DWP should not need to know, and that would not be likely to affect the value of the benefit award.

“I don’t know why they need to know if you’re going on holiday… I suppose because it’s how people cheat the system.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

Similarly, respondents did not always appreciate the urgency of informing DWP of some changes and sometimes did not consider it worth mentioning others, particularly when changes were temporary, such as someone staying for a short time. This could lead to a delay or complete failure to report. Some respondents also felt it was hard to report changes within the required timeframe, particularly by phone and if they were working unsociable hours.

Reporting changes of circumstances was also often linked to a perception of loss. Some respondents assumed that in many cases reporting changes would lead to a reduction of benefits, a suspension of benefits or could trigger a new claim or investigation. In addition, there was a concern that retrospective reporting, for example if they did not report quickly enough, or they wished to come forward to discuss a change that they had missed, would lead to sanctions. This lead to concern that they would have to pay back money that they had already spent, or that it could trigger a process issue that would stop their claim temporarily.

“You are too scared they will stop the money and you need that money and you don’t get enough as it is…”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

“If you are on the breadline as it is, and you’re struggling and if someone said to you we’re going to take £10 off you a week even that may be the difference, you are not going to tell them.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

2.3. Drivers and barriers to risk taking

Across the sample there were different factors that appeared to push claimants towards being more likely to be higher risk takers in terms of non-reporting changes of circumstances, and other factors drove claimants towards being lower risk takers.

2.3.1. Drivers to be a higher risk taker

The key drivers can be summarised as follows:

- belief that the specific detail of their ‘non-compliance’ was such a small thing that it did not need to be reported. The claimant would judge for themselves that their payment will not be affected by such a small change of circumstances

- belief that lots of people get away without updating their claims

- a belief that DWP’s systems means that DWP will not spot anything untoward

- concern about problems that will ensue if DWP’s systems have to make any kind of adjustment to the claim, or that there may be a repayment to make

- prioritising their own or families financial need over honesty about changes of circumstance, due to concern about impact of the change on their amount of benefit

2.3.2.Drivers to be a lower risk taker

The key drivers can be summarised as follows:

- desire to be an honest person

- fear of being caught, whatever the evidence around them of other claimants being dishonest and getting away with it

- fear of one’s benefit payment amount being disrupted (postponed, reduced) and the loss of certainty about what you will receive

- fear of the unknown consequences of making a mistake including dislike of being wrong

- aspirationally wanting to be off benefits, deception is a distraction from moving forward

3. Responses to current DWP communications

This chapter describes research participants’ recollections about the past communications they have received from DWP whether written, electronic (the primary means of communication for UC Full Service claimants), face-to-face or over the telephone. The perceived role of different channels and their impact on long term attitudes and short term behaviour is considered. Claimant attitude to past DWP communications provided important context for understanding responses to the test messages as it demonstrates their expectations and assumptions.

3.1. Engagement and responses to previous DWP communications

The testing of potential new messaging spontaneously prompted discussion amongst respondents of past one-to-one communication with DWP across various channels. There was occasional reference to more broadly targeted communication with claimants such as posters on the wall at jobcentres, but this was largely prompted by discussion of suitable channels for the different messages being tested, i.e. what should be addressed personally to a claimant versus what should be disseminated as general knowledge.

Many respondents claimed they preferred to keep communications with DWP to a minimum, and some in the sample reported having little contact. This was especially so amongst Pension Credit claimants who were unlikely to need to engage with DWP officials (e.g. work coaches) on a regular basis.

3.1.1. Paper communications received from DWP

The receipt of any DWP letters, in their distinctive brown envelope was often reported to invoke anxiety. Often their past engagement with DWP lead to assumptions that the letter would bring bad news. Some respondents admitted being tempted to delay opening letters, although most reported opening them reasonably quickly.

“My heart sinks if I see a brown envelope.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

The most reported paper letter was the summary of their claim with no specific demands mentioned. Universal Credit claimants with little or no change of circumstances to report considered a letter personally addressed to their home to be an annual event, just a statement of account confirming the basis for payments past and ongoing. Other types of letters included those in response to changes of circumstances with entitlement amendments and also demands for action by the claimant. Some reported that they would read letters through in detail. Others talked of scanning the content purely to find the amount they could expect ongoing. There was no unprompted recall of reading written reminders of the terms and conditions of Universal Credit or Pension Credit being re-stated.

Generally, the style and tone of letters received was described as acceptably official, and straightforward although some found them more intimidating. Some Universal Credit claimants mentioned that they had received long letters that were hard to understand in terms of the purpose of the letter and the required action, but ultimately the focus was always on the payment breakdown. Those respondents whose management of their account tended to be reported as more chaotic often referred to the letters they receive as being complex to understand.

“… the letters are very old school. Very scripted… intimidating… They make you feel like we control your life.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

Letters that required action on the part of the claimant for example attendance or repayments were described as more threatening and arrived with growing frequency as opposed to letters confirming payments having been made.

“The last set of letters I got from DWP were those threatening ones for the money that I owed them, and I got two letters in very quick succession… it’s almost like a bombardment.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, North)

Some respondents raised the issue that they had experienced letters arriving late which had caused problems. This was because the claimant thought they had successfully reported a change of circumstance on time, and that any adjustment to benefit payouts would be immediate. Instead a letter arrived sometime later asking them to make a repayment because the benefit had not been adjusted immediately. This demand had caused them a financial problem and added to their belief that the system was not efficient.

3.1.2. Electronic communications

Across the whole research sample, electronic and email communications were less commonly mentioned but generally well received by those who were using such channels. Specific communications referenced were with work coaches, as part of using their online Universal Credit account, or email communications rather than letters.

Respondents suggested that emails allowed for constructive two way conversations with work coaches that would not be undermined by what was seen as petty rules. In tone and content, this one-on-one dialogue was often more adult-to-adult and respectful of each other. Generally, it was felt that email communication provided them with coherent input, allowing for clear responses back to DWP, with a relatively fast turnaround. This step forward in delivery could help address a commonly reported flashpoint for claimants who often thought that DWP was quick to exploit any delay in reporting a change. Emails also were reported to be more action oriented, for example, by prompting claimants to log onto the online account.

“I think the emails are a bit better… I think they are trying to be a bit more modern with the emails…More of an action, don’t forget to log on.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

There was some experience of receiving text messages from DWP, but these were mainly used for reminding them about appointments. Text messages were consistently regarded as a positive medium for providing a useful, welcome, often necessary nudge.

“It helps because at one point I wasn’t very well, and I was forgetting a lot of stuff, so having the text message helps because I could ring up and say can you send me that text as well.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

There was thought to be the potential for DWP to use text more widely, beyond their current primary use as reminders about forthcoming appointments, although claimant consent would always be required. Specific roles for text were not suggested, but there was some sense during discussions that SMS texts could work in similar ways to email as a two way exchange of information, and also for notifications and potentially even reporting changes of circumstances. General messaging, especially where information about the potential penalties for benefit fraud were mentioned, was not desired via text as this was considered too intrusive and inappropriate for such a personal channel.

3.1.3. Telephone contact

Many respondents (both UC and PC claimants) shared negative experiences of contacting DWP via the phone involving long delays in getting through, being told they were speaking to the wrong person, getting contradictory advice or DWP staff not accurately recording the call. Despite this, respondents often cited the telephone as the preferred means of contact, thus relying on DWP staff to accurately record any change of circumstance reported and for staff to be accurate and complete with any advice or guidance passed back. This suggests that DWP having an efficient telephone reporting system is important.

3.1.4. Visiting DWP offices – face-to-face contact

Face-to-face meetings with DWP mostly occurred at jobcentres. Jobcentres were often described by respondents in negative terms, although some discussed positive experiences and outcomes which were largely due to friendly staff who were thought to be knowledgeable and personable.

However, some described the jobcentre environment as a harsh place which discouraged people seeking support and making a claim. The mood was said to be set by the staff, with some comments that even the presence of security guards set up a more negative atmosphere of suspicion or hostility.

3.1.5. Interactions with DWP staff

Contact with DWP staff was described as variable and attitudes were very much driven by whether they felt the staff member was helpful, on their side and sufficiently knowledgeable.

“Sometimes you get really nice ones, but other times no. You don’t like their tone of voice.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, North)

Throughout the research, respondents spoke of how a respectful approach by DWP staff could transform the DWP claimant relationship. UC claimants, in particular, reported how the respect showed to them by staff would be reciprocated, thereby helping to create a virtuous circle of mutual respect. During the course of the research it became evident that these positive interactions often allowed claimants to set aside their views about the shortcomings of the system.

“I had a good one, when I went into the last job I just finished, I had a good communication with them because I rang them and said I was going to miss an appointment with my work coach…He was fantastic, lovely guy.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, North)

Such a shift in attitude was mainly prompted by contact with a work coach who communicated in personal, everyday language offering support and guidance that was felt mostly useful. There were further examples cited of individuals within the system who proved respectful, supportive, empathic and helped people move forward.

3.1.6. Online UC portal

Some positive comments were made by the small number of users of the Universal Credit online portal in the research sample. They were positive about the ease with which they could interact with their account. The key benefits were being able to keep their records up to date, know their circumstances were recorded correctly, and doing so at their own convenience (e.g. after or during any work). It was considered a simple, speedy interface that made it relatively easy to understand what benefits were being paid and why.

In the group sessions, such praise by one user would lead to interest from other respondents. The behaviour in the group suggested that such peer endorsement was working to encourage others to investigate switching to online and away from reliance on a phone call.

3.1.7. Tone of voice within written and verbal communications

For some respondents being on benefits per se was described as being demeaning and undermining of their self respect. This was particularly so if they had been supporting themselves with a job for many years and now had fallen on hard times. On top of this, the research showed that there could be a deep sense of resentment over a feeling that claiming benefits brands you a ‘scrounger’ or a ‘benefits fraudster’ in the eyes of society. This appeared to make respondents sensitive to language that can be interpreted as judgemental.

In addition, some respondents raised a concern that they felt DWP also treated them at times in a patronising way or treated errors on their claim in a way that suggested they were behaving fraudulently before the evidence proved this. This felt at odds with how they perceived DWP should be – i.e. a public service there to help them.

“…they talk to you based on what they think you are, as opposed to who you are and that’s what I didn’t like”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

Those on Pension Credit who had experienced problems had a more mixed attitude to the way they were treated. Although some shared similar experiences of being treated in a way they felt was unfair, others, particularly those who had received a home visit, were more positive about the experience, feeling they had been helped to get their claim right and had not been accused of wrongdoing or negligence from the outset [footnote 5].

4. New messaging

This chapter describes how claimants in the sample responded to the range of test messages (theoretically) from DWP, both in terms of their immediate reactions and subsequent reflections on how they might respond if they received a letter, email or SMS text phrased in particular ways.

4.1. Stimulus review

The research stimulus included a set of messages which could in the future be used by DWP. The messages fell into several themes as follows:

- help and support

- reminders and responsibility

- risk and penalties

- owning or personalising non-compliant behaviour

- social cost and indirect statistics about fraud and error

Several messages were clustered under each of these themes. Over the course of the fieldwork period, some of the messages were amended to reflect emergent findings. The sequence of developing stimuli is included in appendices 4, 5 and 6.

4.2. How messages were received

Exposure to the suggested messages was delivered through the research moderator showing a typed statement then reading it out and allowing the group or individual to respond spontaneously before prompting with further questions. The research showed that some of the messages could readily invoke strong emotions and respondents could be quick to cite heartfelt personal opinions based on their own experience of living on benefits and engaging with DWP to explain and justify their responses to the messages. The research explored individually both respondent comprehension of the messages as well as the reasons behind respondent reactions.

The pattern of their responses broadly reflected the cognitive System 1 or System 2 judgement model developed by the psychologist Professor Daniel Kahneman and explained in his book ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow’. The System 1 and System 2 model proposes two distinct modes of decision making. System 1 is an automatic, fast and mostly unconscious way of thinking that draws on one’s own experiences, knowledge and learnt skills to form intuition. System 1 judgements are impulsive and emotional in character. The limit of an individual’s experiences and memories makes decision making based on System 1 thinking vulnerable to biases and systematic error. By contrast, System 2 is an effortful, relatively slow and controlled way of thinking. It requires energy and attention and has the capacity to consider new evidence that can challenge the intuition or gut reactions of System 1.

Over the course of conversations there was the opportunity to consider what ideas and language used in the messages could invoke System 1 thinking, drawing on past memories and biases, to good effect or not, and to observe and interrogate what specific ideas and language had the potential to encourage System 2 thinking leading to potential consideration of evidence that may or may not lead to a decision of compliant behaviour.

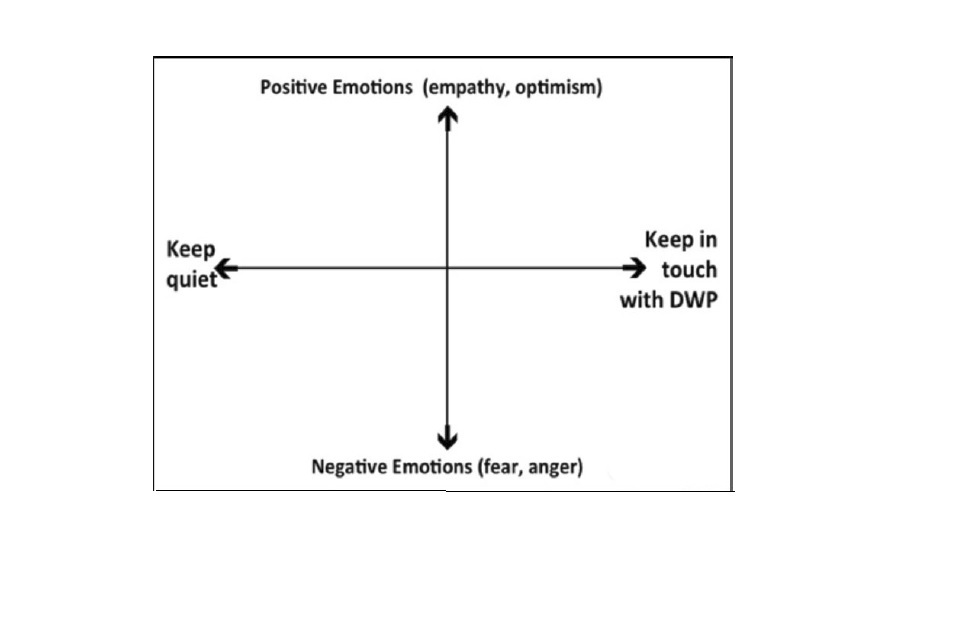

The participants’ cognitive responses provided evidence of whether or not they felt encouraged to keep in touch with DWP, especially regarding any change of circumstance that might affect their benefit award, and whether the message inspired positive or negative emotions.

When operating in the top right quadrant a message was considered to encourage a positive relationship with DWP through emotionally feeling respected and feeling in control. This emotional response lead some respondents to be more objective about DWP’s terms and conditions, to re-consider the consequences of overclaiming and see the benefit in keeping DWP up to date with their changing circumstances. When operating in the top left quadrant a message again inspired positive emotions which helped claimants consider new evidence but it did not sufficiently address barriers to taking action, or encourage contact. At times these messages felt tonally too soft and respondents felt the risk of non-compliance was still worth taking.

When operating in the bottom right quadrant, the messages generated negative emotions such as fear of loss, fear of the consequences of being wrong or noncompliant. The risks were felt to be too great to ignore.

In the bottom left quadrant, the messages encouraged a negative, at times fearful response, which rather than driving action, lead to a feeling that doing nothing was the better response, or there was a sense of angry, justified protest in non-compliance.

Many of the test messages, particularly those warning of the negative consequence of failing to comply triggered spontaneous recall of negative experiences of claimants’ past engagement with DWP. However, interrogating their responses suggested that a shift in language to a more respectful tone could encourage respondents to reflect more on the information being presented.

The research found that it was not possible for just one simple single message or theme to have sufficient power to disrupt a claimant’s mindset to the point where they felt compelled to reconsider non-compliant attitudes and behaviour, however there were many useful lessons about what building blocks could potentially cumulatively change the dynamics of the relationship between claimants and DWP.

Several themes emerged across the research that concerned respondent’s past experiences of being on benefits and dealing with the DWP and as such were highly influential on their attitudes and responses to the messaging which places challenges on DWP communications. Any DWP messaging that aspires to change attitudes and subsequent behaviour regarding non-compliance would have to consider these themes: the claimant’s financial situation, claimant attitudes to DWP and how they perceive their own behaviour.

The general belief across the research was that DWP’s purpose with regard to State Benefits should be to help citizens who are unable to support themselves, for whatever reason. This might be a requirement for temporary support due to an unexpected change of circumstance that the claimant is set on rectifying, or long term for someone who lacks the financial resources and opportunities to support themselves and any dependents.

Many claimants in the sample stated that they held little or no financial reserves. Cash flow was described as a constant problem and generated anxiety. Interruptions to benefits therefore caused significant problems, and benefits being stopped even temporarily could lead to difficult consequences.

In addition, respondents did not necessarily feel that they knew everything that was available to them in terms of benefits or additional support. This could lead them to question why DWP did not ensure that everyone knew of all the support they could access.

“You’ve got this system that’s in place, that says it’s designed to help those people better themselves and push themselves forward and help them support themselves so they can really make something, little things that they do do that are right, they give you access to lots of free courses, they give you all this stuff, but at the same time they’re making it difficult for you to access that.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, North)

Respondents’ attitudes to DWP and how they felt they had been treated across the lifetime of their claim also played a part in how they responded to the messaging. Although there were some who had had positive experiences with DWP and felt more open to messages signalling support and help, there were others who preferred to keep their interactions with DWP to a minimum, and many who expressed negative feelings towards DWP.

Those with more negative attitudes shared a perception of a poorly managed system that they considered to be difficult to access, prone to making errors, slow to action claims, and did not admit responsibility when internal errors were made which led to claimant repayments. This led the participants in this research to feel that the system was not ‘on their side’ and would be keen to reduce entitlements [footnote 6].

“It’s the switchovers that they do between benefits which is shocking, because to me you shouldn’t suffer any heartache for it, because you’re still on one benefit.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, North)

The relationship with DWP was often described as one sided, with the power balance being perceived as firmly on the side of DWP. The experience of the one sided relationship and little or no control appeared to fuel a sense of disempowerment amongst claimants, which made it feel difficult to take any responsibility for one’s own claim.

“One of the problems that I’ve felt with them is the whole lack of responsibility. We have power over you and the way that you live your life and if you don’t do what we say we will take your money from you.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, North)

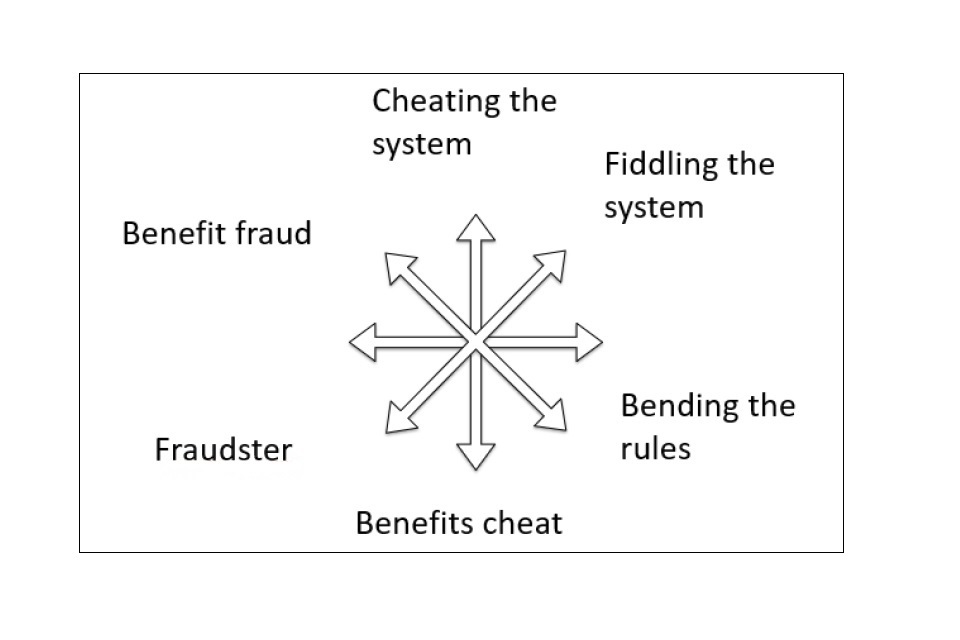

Participants’ thoughts on their own behaviour and what they saw around them impacted on how they responded to messaging and terminology. There was a perception amongst respondents that there was more serious deception of DWP by other claimants not represented in the research. The ‘Benefits Stick’ was common parlance for this type of pre-meditated deception. Although critical of serious benefit fraudsters, it was generally regarded as not their business to report such people. Furthermore, respondents did not want to open themselves up to potential revenge behaviour from other claimants if they reported them.

Claimants often assumed that, in addition to more serious fraud, there were others in the community who routinely fiddled the system, but not in a particularly serious way. For example, some claimants might fail to report minor changes of circumstances or do a small amount of work cash in hand.

“But you’re not going to say anything because it’s going to come back on you….We all know that there is major fraud going on.”

(Pension Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

Some in the sample believed that DWP did little to address either routine or sophisticated fraud. This was sometimes compared to other examples of the State being abused, e.g. high profile tax evasion and the MP’s expenses scandal.

Given these considerations, the sample’s judgement of their own non-compliant behaviour was that they were not the worst offenders, either by making small mistakes, or at times just bending the rules slightly and coping with a difficult system by working round it. In this context, it was evident that they believed that this type of behaviour was not benefit fraud. They justified this type of behaviour as just trying to make ends meet or trying to better themselves to get out of a problematic time and back to a self supporting way of life. On occasion it was even seen as acceptable, as in their view DWP processes and systems have allowed others to get away with much worse behaviour.

Given this context, the word ‘fraud’ in any messaging signalled large scale fraudulent behaviour to the audience. This was seen as people undertaking criminal behaviour who were actively out to defraud DWP at a significant level, for example making up fraudulent claims or pretending to be disabled when they are not. As this was not seen as the type of behaviour that they themselves engaged in, some felt they were unlikely to think that statements that directly highlighted ‘fraud’ were aimed at them and therefore they could be ignored. When challenged about the relevance of such language to their own behaviour they felt it was unfair or unjust for them to be branded as fraudsters.

Some argued that language such as ‘cheating’ or ‘fiddling the system’ felt more in line with low level non-reporting of changes of circumstances. However, they would not brand themselves in this way and this behaviour was easily justified in their eyes.

“Someone with a two hour thing doing cleaning and getting £15 cash in hand… that’s not making any difference. It’s showing that they are trying to do something better with their life.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, South)

4.3. Helpful messages – messages of support and guidance

Two messages were tested with the aim of offering better support and guidance. Spontaneously, these messages could be well received, being read as friendly, helpful, supportive, professional, accessible and approachable. DWP was seen to be ostensibly professing empathy, which was unexpected by claimants who were expecting a more distant tone.

When read with an open mind these types of messages could tap into what support the claimants felt they should be receiving from DWP, and for those in real need of help through ignorance of the system such messages can be seen to meet a heartfelt need.

However, their experiences of DWP primed many to respond cynically. Their prior experience contradicted the promise of the helpful message, for example a lack of empathy shown by staff, long waits to get through on the phone and too complex, unintelligible information provided.

Perceiving the open offer of help as cynically motivated, this lead to disquieting thoughts that the outcome of any such request for help would inevitably be a reduction to their current benefits award.

Therefore, overall although these messages, as a vehicle to encourage compliance and contact, could at face value appear to encourage a more positive relationship of openness with DWP, the reality of the experience did not always encourage claimants to believe the message and want to keep in touch.

4.3.1. Individual messages

Need advice about your benefits claim?

Unsure about something relating to your benefits claim?

We’re here to help. We now offer free telephone calls to our benefits hotline. Call 0300 123 123 or visit GOV.UK/your-benefit-claim for more information.

The headline of this message attracted attention and interest from UC claimants but was often rejected by Pension Credit claimants who did not think it used terminology that directly targeted them – they did not think they had a ‘benefits claim’.

Overall, this message was considered to be to the point and straightforward. Tonally it was felt to be helpful, informative and professional, as they thought should be expected of DWP. It usefully provided a telephone number and website and opened up with offers of help and access.

However, this message sometimes provoked negative comments about the length of time it could take to access support via the phone, and how complex the website could be, which showed how quick to draw on negative experiences, some claimants can be.

“I like that one because it’s less false. Not trying to appear super friendly.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, South)

“They are trying to be helpful, but it isn’t helpful… If you go on to your computer, it’s not simple.”

(Pension Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

‘We’re here to help’ was also a contentious statement. Although the suggestion that claimants could call for help if they were unsure about something was taken at face value and welcomed by some, on further reflection this message was felt more suitable for new claimants in the early stage of their DWP journey who genuinely needed help and did not know the system. Many respondents, drawing upon their own experiences, questioned if DWP was really there to help claimants, and if claimants could really ring if they were ‘unsure’. This cynicism was driven by a widely held belief amongst respondents that DWP simply wanted to reduce the size of a person’s claim as much as possible and therefore any calls to change one’s details would result in a lower award.

“If there’s anything you need to know regarding your benefit they can help you. But you don’t know if what you’ve got to say to them will help… For me looking at that how it’s composed I don’t feel it is friendly enough. I see the attempt at being helpful but it’s just not good enough… I don’t believe it.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, North)

We understand that life can be complicated at times.

Contact one of our trained advisers at the Department for Work & Pensions and let us help you keep on top of your benefits claim.

This message generated a mixed response. At face value it was seen as an attempt to be sympathetic and empathetic, showing that DWP are approachable and relatable – and recognised that everyone can face problems in their life. This was felt to be a credible attempt at empathy that engaged some claimants who wanted their own position to be understood and felt in need of financial help and clear procedural guidance.

“They are trying to help you.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

“We understand… That says a lot… That small statement saying we understand, that shows us that whoever we are speaking to we understand.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, North)

However, previous poor experiences of DWP services amongst the claimants in the research sample led to more negative and cynical responses, primarily driven by the headline: ‘We understand that life can be complicated at times.’ The responses suggested therefore that this was not a credible statement for many, who did not feel that DWP was empathetic and understanding of the day-to-day realities and difficulties faced by individual claimants.

“I suppose it’s because my experience I felt nobody was understanding so if I’m reading ‘they do understand’…. But the man that wrote ‘we understand’ isn’t answering the phone to you. It’s some other overworked person… There’s no real sympathy in there.”

(Pension Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

The call to keep in touch with DWP ‘to help you keep on top of your benefits claim’ was read by some positively as optimising entitlement, but also by others cynically, as leading to action that would ultimately only help DWP minimise the claimant’s benefit award.

The line ‘Contact one of our trained advisers’ could again be subject to criticism dependent on the claimant’s own experiences of DWP advisers. The word ‘trained’ was welcomed but was also challenged by those whose experience suggested that DWP staff lacked the relevant experience, proper training and knowledge and were therefore prone to making errors.

4.4. Reminder messages – reminders and responsibility

Three messages were tested within this theme as outlined below.

Reminding claimants about which changes of circumstance they needed to report was usually positively received, if the messages were seen as practical, inoffensive and timely prompts. However, on their own, reminders seemed insufficient to drive action amongst those who were more likely to take a risk and not report changes. The research suggests, however, that using the positive framing of a useful reminder appears to allow a reference to avoiding penalties, making the message feel beneficial to the claimant rather than threatening.

An instruction for the claimant to act responsibly, however, often generated a very negative emotional response. Although many claimants in the sample rationally recognised it was their responsibility to update their details, the tone of this type of message was often considered provocative as it highlighted an aspect of their lives where they felt they had no control. Reminding them of their responsibility therefore sometimes invoked feelings of powerlessness, dependency and fear of getting something wrong. Concern was expressed particularly about the negative impact on and potential responses of more vulnerable people in society if they were to receive messages like this (e.g. those with mental health issues).

4.4.1. Individual messages

We’re here to help you get your benefit claim right

Found a new job or finished an old one? Changed address? Has someone moved in or moved out? Unable to work? Change of circumstance?

Tell us now and we will help you take care of it.

This message was well received overall and reported to feel friendly, helpful and collaborative. The headline ‘We’re here to help you get your benefit claim right’ was received as a positive opening line that implied more of a customer service relationship i.e. a concern on behalf of DWP to help the claimant. However, this did not resonate as strongly with Pension Credit claimants who did not see Pension Credit as a ‘benefit claim’.

“I feel welcome and not just a number…We’re here to help… They’re supposed to be there to help.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

“We’re here to help that clicks with me. At the end of the day that is their job.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, North)

The subsequent list of changes of circumstances (a commonly understood term) was considered to provide practical, useful prompts, in the form of questions, about when to update a benefit claim. This advice was felt likely to both remind claimants of responsibilities that they had forgotten or inform them of new circumstances they did not know about. This was considered useful given the context explained earlier that respondents did not feel they knew or would remember the full list.

“It’s giving you a list of things that could go wrong and then saying we can help you.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

“On that one you understand the circumstances that they want you to tell them about so that’s very good that one.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, North)

The phrase ‘Tell us now’ was, however, described as being rather ‘parent to child’ in tone, implying that immediate action is required. The subsequent ‘we will help you take care of it’ was reported to feel friendly and helpful, but did also at times provoke a more cynical response of ‘will DWP really help me?’ This particular phrase therefore felt disempowering to some claimants who felt that it would be them, rather than DWP, who would have to ‘take care of it’ (i.e. a likely decrease in the value of their benefit award) when they were not in a position to absorb a reduction in household income. Other respondents could not understand why DWP needed to know some of these facts, for example if someone had moved into their house.

“They say when you tell us certain stuff that they are there to help… but say you’ve got your own place and this person is staying with you but they are literally just staying with you then they will stop your benefit because you’ve got someone staying in your house, but it doesn’t mean that they are paying rent or working.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, South)

In addition, the speed with which claimants are expected to inform DWP was cited as a potentially difficult:

“So that’s another problem. ‘Tell us now’ – they should give you a bit of leeway, a couple of days saying sorry I couldn’t get to you then, but I’m getting to you now.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, North)

In terms of overall impact some believed this message could prompt them to consider their changes of circumstances and what they might need to report and therefore keep in touch with DWP.

“Because of the tone again. It’s not like ‘right I’m going to get you’, it’s helpful.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

However, others who felt more likely to take a risk and not report changes did not feel it would drive action as there was no perceived negative attached to non-reporting. As shown above, there were also concerns expressed that any reporting would ultimately lead to a reduction in a claim which was a barrier to coming forward.

Discussions also showed that claimants did not always appreciate the required timeline for reporting changes of circumstances, particularly where changes did not appear time sensitive or claimants did not understand the rationale for reporting the change. One consequence of this, is that this message generated concern about potential retrospective repayments and sanctions if someone was to report a change too late. It became clear over the course of the research that regular mechanisms and reminders designed to encourage changes of circumstances to be more salient could be beneficial.

In the final phase of the research the phrase ‘Tell us now and we will help you take care of it and avoid unnecessary penalties or sanctions’ was tested and this appeared to work well as ‘take care of it’ became linked to the avoidance of penalties and sanctions which was seen as a genuine customer benefit. This therefore felt more supportive and credible.

Your claim, your responsibility.

It’s your responsibility to keep your details up to date. Tell us now and we will help you take care of it.

This message provoked a polarised and at times strong response. The headline ‘your claim, your responsibility’ felt quite aggressive in tone as a stand alone phrase in particular.

On the one hand, some respondents agreed with the suggestion that it is your own responsibility to look after your own claim and update your details, as no one else knows your own unique circumstances. However, this line also prompted discussion over the issue of control – and the fact that although it may be their own claim, claimants felt as if they had no control as DWP hold all the power. This shifting of responsibility to the claimant therefore reinforced their sense of powerlessness and risked making people, particularly those who were more vulnerable overly anxious.

“It’s my claim, it’s my responsibility, I’m starting work, and I will tell you… I don’t think you can blame anybody else.”

(Pension Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

“I think responsibility is important….I do think that people don’t take enough responsibility for their own actions… but the whole claim, your responsibility, I feel anxious just listening to you say it.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, North)

Overall the message was interpreted as showing little empathy and implied that claimants would be in the wrong if they did not update their details and could be told off – which made some fearful of having made a mistake. This message also raised the issue of DWP mistakes and how they were powerless to influence this.

“I’d be scared… I would think I need to do something about it but I’m not going to… (why is that) Because it’s that word responsibility, I think if you phoned up and there was some kind of discrepancy it’s your fault. That kind of thing… Or worse still we’re going to fine you or take you to court, that what it says to me.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

“For the average people who just feel like they’ve made a mistake, or they want that extra piece of information or they need to give back information, it needs to be made more welcoming that you can do that because there is a relationship between the two… it is your responsibility, so come on tell us about it and we’ll help you out.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, North)

Check your details regularly

People check their household expenses to ensure they are being charged the right amount.

Make it a priority to regularly check your benefits claim and report any changes of circumstance when they happen.

This message was not well received and was not felt to deliver a clear or useful analogy that would remind claimants of the need to check their claims.

Firstly, checking one’s household expenses regularly was not described as a common activity across the sample. In addition, benefit claims and in particular pension claims, were not felt to be variable on a monthly basis – they would only change after a significant change of circumstances had been reported, and therefore regularly checking your claim was not seen as necessary.

“If you are told your pension is £60 a week, the £60 a week is there every week, so why would you check it?”

(Pension Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

However, the concept can touch on an important issue for claimants about finding ways to manage their finances in a way that produces stability and the financial reserves to cope with the unexpected.

4.5. Messages about risk – Fraud and error detection and penalties

Five messages were tested within the two themes of raising the perception of risk and highlighting penalties. In this report these two themes have been grouped together due to the commonality in responses. Overall these messages were designed to communicate threat in order to encourage non-compliant claimants to reconsider the inevitability of being found out, or to deter potentially non-compliant claimants from slipping into the wrong behaviour. Risk was evaluated considering the probability of being found out factored by the price of being found out.

These messages tended to provoke fear and anxiety, and these negative emotions worked in different ways. In people who felt more likely to take a risk and not report changes, the messages appeared to provoke responses such as anger, disbelief or resignation which discouraged contact with DWP. Others in the sample simply responded by disassociating themselves from the messages feeling that they were either not aimed at them, and therefore would not apply, or they argued that DWP would never take action against them and therefore they did not need to take note. Some admitted to feeling frozen by fear and claimed they would not want to come forward and report changes due to concerns about penalties.

“A lot of this is based on fear and that is playing into the hands of someone’s fears and this is the stuff you will be scared of… (Is there any role for this?) I think they should but that’s not part of the same campaign as telling someone to contact and update your details, the two things are separated… So, when you sign up initially, you maybe sign, make that very clear.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

Others who were keen to be honest and were fearful of making mistakes claimed they would want to avoid penalties and although these messages evoked negative emotions and fear in them, they felt they could act as a deterrent to non-compliant behaviour and would encourage them to report changes of circumstances.

The research also showed that certain tonal factors pushed people to a more negative emotional mindset and this appeared to stand in the way of objective reasoned reflection. Claimants theorised that their emotions would be heightened if the messaging was included within direct personal communications such as a text message or a personal letter, or if the recipient was more vulnerable such as having mental health issues – there could be great concern about the impact of this type of messaging and tone on such people.

The tonal factors that appeared to inspire these more negative emotional responses included messages that appeared to be pointing the finger at the recipient, using personalised language such as ‘you’, short staccato sentence structure which felt aggressive, using emotive words such as ‘fraud’ or ‘fraudster’ and linking penalties to making a mistake. These tended to re-enforce a negative stereotype that DWP assumes all claimants are guilty and behaving fraudulently, rather than generally assuming claimants are primarily honest. DWP as an organisation therefore felt more aggressive and hard to approach.

Other tonal factors, appeared to trigger a less negative emotionally charged mindset, even when delivering harsh information about penalties and risk. Using polite, depersonalised language worked well in terms of encouraging acceptance and openness. Framing the message in more positive terms at the start, inviting an open, honest and respectful relationship, also allowed for a less negative initial response. Using a formal, informative, authoritative but serious tone showed DWP was serious in its intent but not too soft. When pitched in this way the information about penalties was transformed into something that claimants considered important to know and they have a right to understand. DWP in their eyes became firm, but fair and respectful.

4.5.1. Individual messaging

Fraud and error detection

Two messages were tested focusing on fraud and error detection techniques.

DWP uses advanced error detection techniques

DWP wants to prevent mistakes to make sure everyone who needs to claim benefits is paid the right amount

This message tended not to be received very well. The headline focused on ‘error detection techniques’ initially lead respondents to discuss DWP’s own errors rather than claimant error. This was further backed up by the remainder of the copy which suggested to respondents that DWP wanted to minimise their mistakes. However, the stated aim of ensuring that every claimant is paid the right amount of benefit was described as a positive goal.

“It’s basically saying Big Brother is watching you, you’d better tell the truth, we’re going to catch you.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

The Department for Work & Pensions uses advanced fraud detection techniques

DWP is committed to deterring and preventing fraud and error by benefit claimants. We are committed to finding and investigating benefit fraud and we will issue financial penalties and prosecute people where this is appropriate.

- DWP regularly checks tax information from HM Revenue and Customs to ensure your claim is correct

- where fraud is suspected DWP has the power to access bank and building society statements

- DWP regularly checks migration information from the Home Office to make sure people are correctly claiming benefits whilst they are abroad

If you are hiding something we will find it

This message tended to work better overall than a more simple message without the detail. Tonally the opening point, ‘DWP is committed…’ was described as having a serious, informative and authoritative tone which grabbed attention and showed that DWP meant business and was actively working against fraud. Respondents tended to agree that it was appropriate to issue financial penalties and prosecute those who committed fraud. This was an important distinction from the previous message which encouraged a response focused on what claimants saw as DWP errors.

“It’s pretty straightforward. If you do this, this will happen.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, South)

“Straight to the point… No not threatening… more information on that than anything.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, North)

Giving substance to the claim of using advanced fraud detection techniques by providing a bullet point list of activities, reinforced the steps that DWP could take and therefore did not feel like an empty threat although some found the message overall too long and wordy. From the list included, the checking of HMRC records and looking at bank accounts felt personally invasive, but also personally relevant and the evidence set out in the message matched some respondents’ own experiences. Looking at immigration records struck a chord with some of those who travel abroad.

“Why shouldn’t they check HMRC, it’s another government department.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, South)

“I don’t like the thought of them going through my bank account. That’s my personal details…Yes, they do, they do look, trust me.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

“You need something that’s nice and informative and not too worrying, but when it’s got all the information like this people don’t bother reading it. They go it’s too much.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, North)

Overall this detailed information about DWP’s fraud and error detection approaches alongside a tonally strong statement of intent evoked a mix of responses. Some found it informative and thought it was important to know this information from the outset of their relationship with DWP, using an impersonal approach. Others found it frightening, and felt they should take note, anticipating that it could deter claimants from fraudulent behaviour.

“Power… Makes you feel anxious… If you were signing at the very beginning these are the things that they need to say, then maybe you’d think twice before you start hiding the truth and stuff.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

However, there were those who argued that this was not aimed at them, that calling out ‘fraud’ overtly, signalled a serious type of crime and abuse of the system that was not relevant to them or did not include minor infringements. There were also some in the sample who disputed the information arguing that DWP did not do enough to catch ‘real criminals’ despite what this message suggested. Finally some were annoyed at what they thought was an implication that all claimants were prone to be fraudulent – which suggests care is needed in the placement and framing of messages such as this.

“It’s snooping, Big Brother is watching you. Because you are here in the first place you’re going to be a liar therefore we’re going to… anything that you do we’re going to point the finger at you.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

“If you think that you’re acting properly would you actually take any notice of this?”

(Pension Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

The final line however ‘If you are hiding something we will find it’ was tonally more divisive, either provoking fear or making respondents feel targeted in an aggressive fashion, suggesting DWP thought everyone was guilty until proven innocent.

“Nothing wrong with the information, it’s very valid information but very aggressive… We will find out… We will find you.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, North)

Penalty messaging

Three messages were tested about penalties:

(Please) make sure you are up to date, so you don’t get a penalty or lose your benefits

(Your claim is your responsibility) keep your details up to date or face a potential financial penalty, loss of benefits or prosecution for benefit fraud

Two versions of this message were tested – with and without the bracketed text.

The headline ‘(Please) make sure you are up to date, so you don’t get a penalty or lose your benefits’ was felt to be engaging across both versions as it was seen as a clear call to action to keep up to date, with a simple reminder of the consequences if you do not. However typically the politer version using the word ‘please’ was much better received as this simple addition showed respect for benefit claimants. Overall this statement was accepted as trying to help claimants avoid a problematic situation and this gave license to remind of the potential consequences of not updating your claim. However, this line did not feel as if it had sufficient potency to challenge current non-compliant behaviour on its own.

“It’s saying make sure it’s up to date because you don’t want to get in trouble if it’s not, but it’s when you start talking about potential, losing your benefits, that is really scary… to me that eats at me. The thought of having no money at all…I like the please bit I do.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

“Please, I like the way it starts… Because when you start reading, and it’s like okay yes, and then when you get to the end you don’t want this to happen to you.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, North)

The inclusion of the statement about responsibility appeared to heighten anxiety further and when claimants were exposed to the version that included ‘your claim is your responsibility’ there was often a more negative immediate response to the message overall, with particular concerns being raised about the potentially negative or extreme response of those who are more vulnerable in society who may panic (e.g. those with mental health issues).

“Then again ‘your claim is your responsibility’, that sounds threatening to me…A bit threatening maybe as well. A bit unsure about the benefits system and then you come across that…It would cause a panic situation. A panic attack… Think about it another way, someone with mental health issues got that through the door it would get to you.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, North)

When exploring the final statement ‘keep your details up to date or face a potential financial penalty, loss of benefits or prosecution for benefit fraud’ respondents focused on the three types of consequences and these worked together to give a broad summary of what could happen to them. Of the three highlighted, financial penalties were not particularly well known as a consequence. Suspension of benefits and repayment of overpaid benefits were the more commonly known consequences, and any suggestion of interruption to benefits evoked fear. There was some awareness of having to go to court and prosecution – with occasional experience in the sample – and this also provoked fear.

Typically, this part of the communication provoked responses in line with those described earlier. Claimants either felt frightened enough not to want to be penalised, which encouraged them to behave correctly, or they felt frightened and paralysed and therefore felt they would keep quiet about their behaviour in case they had to pay a fine, pay back an overpayment or lose their benefits, or they dismissed the message and did not think they would be caught and fined.

“I would ring up and see what my situation is and what would happen… Sanctioning means you lose your benefits for 2 weeks, but prosecution and fraud, to me that’s scary…”

(Pension Credit Claimant Focus Group, South)

“Making you keep quiet because you’re frightened.”

(Universal Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)

“Yes, but when did you ever hear of a pensioner being done?”

(Pension Credit Claimant Focus Group, Midlands)