Findings from the GCA investigation

Published 25 March 2019

18. In reaching my findings I have carefully considered all the information provided by Co-op and its employees and Suppliers. I have analysed the material that is relevant to paragraphs 16, 3 and 2 of the Code. In this section of the report I set out the findings that I have made in respect of paragraphs 16 and 3 and the reasons for these findings.

Findings of fact on De-listing without reasonable notice

What the Code says

16. Duties in relation to De-listing

Prior to De-listing a Supplier, a Retailer must: provide Reasonable Notice to the Supplier of the Retailer’s decision to De-list.

19. Principal findings on De-listing without reasonable notice

19.1 I find that Co-op applied the Code wrongly in relation to the reasonable notice requirement of paragraph 16. I find that Co-op De-listed Suppliers with no, or short, fixed notice periods that were not reasonable in the circumstances. These were applied unilaterally and did not conform to the De-listing Guidance. Further, when making volume changes, I find that Co-op did not always correctly consider significance to determine whether the De-listing requirements of the Code were engaged. This conduct was not compliant with the Code. I find that Co-op broke paragraph 16 of the Code.

20. De-listing decisions were made and applied with no, or short, fixed notice periods

20.1 I find that De-listing decisions were made and applied with no, or short, fixed notice periods, unilaterally imposed by Co-op without due consideration of published GCA De-listing guidance, including but not limited to decisions issued between summer 2016 and summer 2017 as part of its Right Range Right Store programme.

These decisions were made in relation to a range of different Suppliers supplying different categories of products to the Co-op business.

20.2 In some cases these decisions were made as a result of standard notice periods being applied by Co-op. Until July 2017 these notice periods were referred to in the Co-op De-list Process document (the Process document) as “relevant notice periods” of 12 weeks (minimum) for own-label products and two weeks (minimum) for branded products. The Process document was described by Co-op as “to provide guidance on the process to follow for de-listing a supplier and de-listing a product line, ensuring that we are compliant with GSCOP.” Until July 2017 a draft email was included in the Process document that buyers were required to use when informing Suppliers of De-listing. This included reference to a 12 week/two week period of notice. The drafts of the Process document before January 2018 included only brief reference to the fact that these were not fixed notice periods and as much notice as was reasonably possible should be given.

20.3 It is therefore unsurprising that I found evidence of numerous occasions when Co-op buyers applied these minimum notice periods as standard requirements, without any consideration as to the particular circumstances of the product or Supplier in question.

20.4 I find that Co-op applied standard notice periods contrary to the Code, my De-listing Guidance and my Supplementary De-listing Guidance, all of which specify that notice of De-listing should be considered on a case-by-case basis.

20.5 The processes followed by Co-op also meant that notice was often given of an artificial “effective date” for De-listing, which had the effect of further shortening the actual notice period being given to Suppliers. The correspondence sent by Co-op to Suppliers when notifying them of De-listing frequently referred to notice being given of an “effective date” of De-listing. This appears to have been the date that the changes to products were being implemented in stores. A separate date would be given to Suppliers of the date for the final order. This was inevitably earlier than the “effective date” and was the date that was of most relevance to the Supplier. The reliance placed by Co-op on the “effective date” of De-listing rather than the date of the last order had the effect of artificially increasing the period of notice that Co-op stated it was giving to Suppliers. Even if Co-op had considered whether the notice period for the “effective date” was reasonable for the Supplier, the notice of the last order date might still have been unreasonable.

21. Co-op failed to identify circumstances in which decisions might result in significant reductions in volume

21.1 I find that Co-op failed to identify what decisions might result in significant reductions in the volume of groceries bought from Suppliers and at times to deal with them in a Code-compliant way by giving reasonable notice in accordance with paragraph 16.

21.2 Many of these circumstances arose when Co-op carried out range reviews. Range reviews would inevitably result in drops in the number of stores that some products were stocked in. For many of these products this would amount to a reduction in order volumes. Sometimes these reductions would be significant. Co-op accepted that it had experienced issues with the notice given for De-listing decisions because of how it had managed drops in distribution arising from range reviews and its failure to recognise the impact on Suppliers.

21.3 The circumstances that I saw which gave rise to reductions in volume which were either not identified by Co-op as potentially significant or even if they were, were then not identified by Co-op as requiring reasonable notice or were made without a reasonable notice period having properly been considered included:

-

a) Where the number of product lines stocked from a particular Supplier reduces, even if the volume of remaining lines stocked from the same Supplier is increased. I received evidence from Suppliers which had experienced one or more products being entirely removed from the Co-op range, meaning that no orders would be placed for that product in future. These product removals sometimes occurred with no notice or less than one week’s notice being given to the Supplier. For some Suppliers the products being removed constituted a large proportion of its business with Co-op. For others, particularly the larger Suppliers, the De- listings were a smaller proportion of their Co-op business. At times larger Suppliers were less concerned about the removal of individual products because orders for other products that they supplied to Co-op had increased in the same range review. However I saw very little evidence of Co-op considering a Supplier’s circumstances and the impact of the removal of products on a Supplier. In particular I saw very little evidence of Co-op considering the effect of product removals on production costs and planning, particularly for smaller Suppliers that might not supply that product to other customers. There was no apparent distinction in the notice given for the removal of product lines which were potentially significant to the Supplier and those which were not.

-

b) Where the volume of particular product lines stocked from a particular Supplier reduces even if the volume of other remaining lines stocked from the same Supplier is increased. I saw numerous examples of range reviews resulting in drops in distribution which might amount to a significant reduction in the orders being placed for particular product lines. In many of these cases Co-op failed to consider the significance of any changes, whether reasonable notice of the change was required and if so, what amounted to reasonable notice. Instead it applied either standard notice periods according to its internal Process document, or even shorter notice periods dictated by the systems and commercial needs of Co-op, or in some cases no notice at all. Examples that I saw included a small Supplier which contacted Co-op about a drop in distribution of one product of over 50%, which had apparently happened three weeks earlier with no notice given. I saw evidence of a large number of Suppliers receiving around three weeks’ notice or less of potentially significant drops in distribution of products.

Some of the occasions when no notice was given of volume reductions of particular product lines occurred where these products had been stocked in stores that had been sold by Co-op. In July 2016 Co-op agreed to sell approximately 300 of its stores to McColl’s convenience stores. The transfer of the stores took place over a six-month period between February and July 2017. I saw a number of examples of Suppliers raising the fact that their distribution levels had dropped without any notice and Co-op explaining that the drop was due, at least in part, to the fact that 300 stores had been sold. The correspondence with these Suppliers made it clear that no notice had been given to these Suppliers of the sale of stores or the drop in distribution to their products that would result from the sale. While Co-op may have engaged with some Suppliers about the upcoming sale of stores, this does not appear to have occurred with all Suppliers. There was inadequate consideration by Co-op of the impact of the sale of stores on Suppliers and a failure to identify that potentially significant reductions in volume might occur which required reasonable notice.

Other occasions when volumes of particular product lines were reduced were when “swap- outs” occurred. Swap-outs involved local products being swapped in by local stores to replace lead products, for example a local Supplier used in certain stores instead of a national Supplier. This would occur in one or a few shops in an area but would not be recorded centrally. Therefore the buyer believed that the national Supplier was still stocked in those shops. If the buyer subsequently decided to remove the national Supplier from those stores, this would have the effect of removing the local product too. This could amount to a significant reduction in the volume of that product for a local Supplier. No notice would have been given of this because the potentially significant reduction had not been identified by Co-op.

Volume reductions on particular product lines also occurred where independent co-operative societies placed orders through the central Co-op team. The Co-op commercial team would not be aware of changes made by the societies to the orders that Co-op was making, despite the fact that in some cases orders from independent co-operative societies accounted for a large proportion of the orders placed with a Supplier by Co-op. Co-op had not identified the potential for these changes to amount to significant reductions for the Supplier and buyers were unaware of the changes, therefore no assessment of significance and reasonable notice appears to have taken place.

- c) Where there is a temporary removal of a product or temporary reduction in the volume of particular product lines stocked from a Supplier. For example, I received information about Delivery Exception Groups (DEGs) which were introduced by Co-op at certain times of the year, such as in the lead-up to Christmas when products would be temporarily removed and then re-listed in the New Year. Although these changes were only temporary, they could be significant to the Supplier and amount to De-listing. The significance of each situation would depend upon the facts in that case.

It was important for the buyer to engage with the Supplier where a DEG was occurring to ensure that the impact on the Supplier was properly understood. One Supplier reported that Co-op did generally work with them on DEGs but in other cases they occurred with less than one week’s notice, which was described by one Supplier as “not optimal”; and in another case with no notice, in which the Supplier stated that the temporary removal had severely and adversely affected its sales of that product. Again, there were occasions when Co-op failed properly to consider significance and reasonable notice and may as a result have broken the Code.

21.4 Of course, the termination of a supply relationship with a particular Supplier would almost always be significant and require reasonable notice. I did see specific examples of Co-op ceasing to work with particular Suppliers. However on none of these occasions did the notice period appear to the Supplier to be unreasonable. I also saw from the statistical analysis which I present at paragraph 24 that Co-op had terminated some other Supplier relationships in the period under investigation, but I do not have information from each of those Suppliers as to whether or not they felt the notice given was reasonable so I make no finding about it.

21.5 Similarly, to reduce the overall volume by turnover across all lines stocked from a particular Supplier will often result in aggregate changes which may be significant for any particular Supplier. Changes to volumes for individual product lines might not be significant in examples of this type, but as the De-listing Guidance gives no maximum or minimum changes to overall volume that would constitute a significant change, it is clear that this will need to be considered on a case-by-case basis. Co-op should have been considering the overall impact on Suppliers of volume changes when conducting range reviews and changing distribution levels. However I did not see evidence of Co-op doing this.

Extent and scale of De-listing without reasonable notice

22. Co-op has provided me with information about its engagement with a large number of Suppliers where it had identified that De-listing may have occurred without reasonable notice. Despite these efforts it was clear to me that Co-op had been unable to establish which Suppliers had and had not been affected by De-listing without reasonable notice.

23. Although it is not possible to quantify precisely the number or proportion of Suppliers affected by De-listing decisions made and applied with no, or short, fixed notice periods, the evidence I have received indicates that a significant number of Suppliers have been affected. This includes Suppliers of various sizes and across various categories of the Co-op groceries business.

24. As part of my investigation I engaged a company of statistical consultants to analyse data provided to me by Co-op. This data contained all of the Co-op Suppliers, the product lines, or stock keeping units (SKUs), that they supplied and the depth of distribution for each SKU, as at 4 January 2016, 2 January 2017 and 2 January 2018. This enabled an analysis to be undertaken of the changes in product listings from one year to the next. This analysis established that:

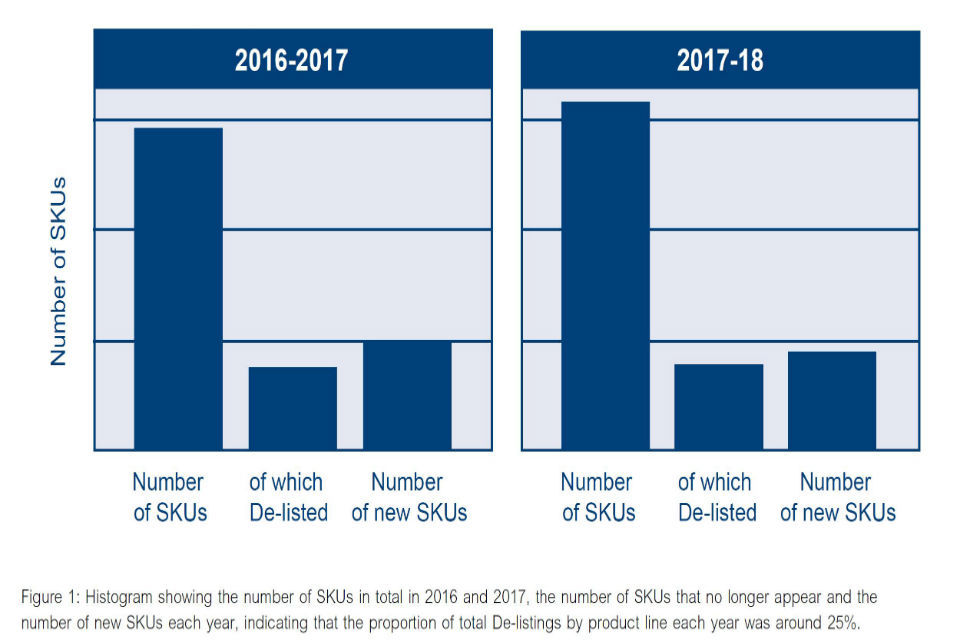

- the proportion of total De-listings by SKU each year was around 25%;

Histogram showing the number of SKUs in total in 2016 and 2017, the number of SKUs that no longer appear and the number of new SKUs each year, indicating that the proportion of total De-listings by product line each year was around 25%.

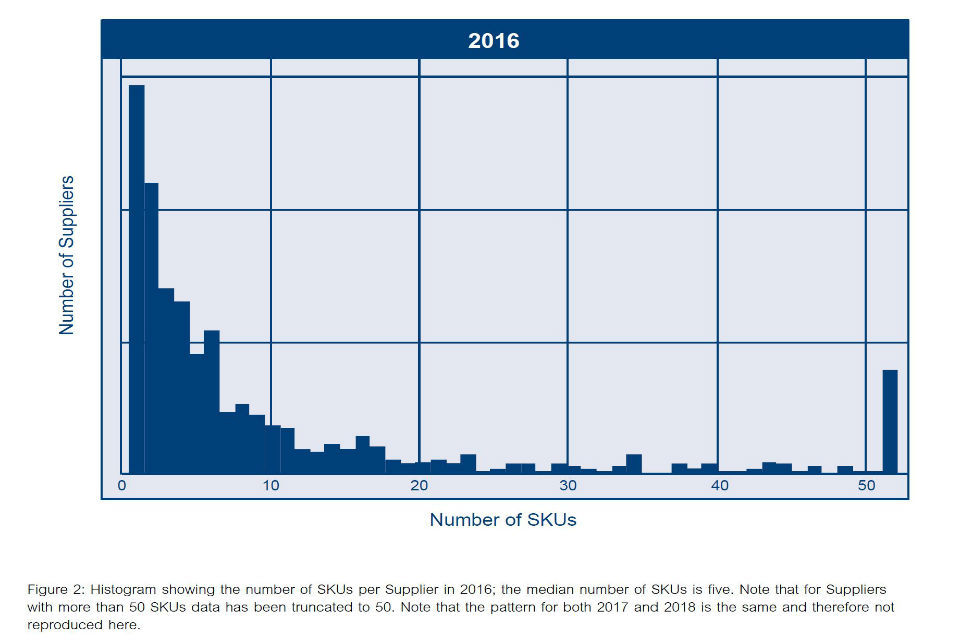

- the median number of SKUs for each Supplier was five, meaning that there were a large number of Suppliers with only a small number of listed products;

Histogram showing number of SKUs per Supplier in 2016; the median of SKUs is five. Note that for Suppliers with more than 50 SKUs data has been truncated to 50. The pattern for both 2017 and 2018 is the same and therefore not reproduced here.

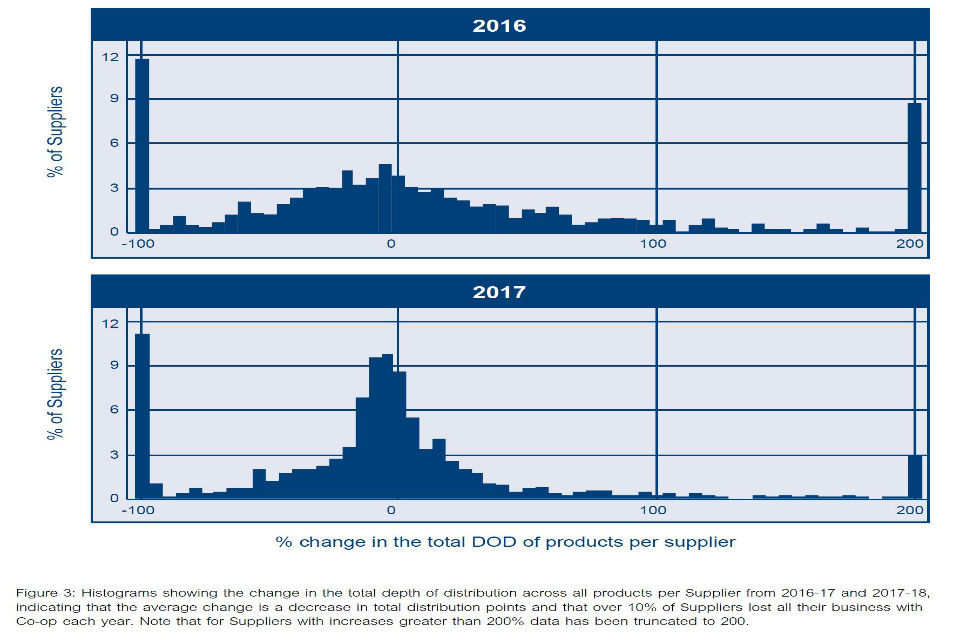

- 87% of Suppliers experienced a volume change in distribution of more than 10% between 4 January 2016 and 2 January 2017 and 72% of Suppliers had this experience between 2 January 2017 and 2 January 2018. In both years the average change was a decrease in total distribution points for each Supplier; and

- over 10% of Suppliers lost all their business with Co-op each year.

Histograms showing change in the total depth of distribution across all products per Supplier from 2016-17 and 2017-18. The average change is a decrease in total distribution points. Over 10% of Suppliers lost all their business with Co-op each year.

Of course, not all removal of products would have occurred without reasonable notice and not all drops in distribution would have amounted to a significant reduction and/or have been made without reasonable notice. The figures nonetheless provide a sense of the scale of changes being implemented by Co-op and the number of occasions on which Co-op would have needed to consider whether changes amounted to De-listing in each case and then if so, to go on to consider what period of notice would be reasonable in the circumstances.

Impact on Suppliers of De-listing without reasonable notice

25. It has been difficult to quantify with any precision the total impact on Suppliers of Co-op De- listing decisions made without reasonable notice. This is partly due to the difficulties with identifying all of those Suppliers who may have been affected.

26. Nevertheless, Suppliers have informed me of their views on how De-listing decisions without reasonable notice have affected their businesses. I have set out in this section the different types of impact that I have identified, under the headings financial impact, wastage, administrative burden and associated costs on Suppliers, and uncertainty created for Suppliers.

27. Financial impact

27.1 For a large number of Suppliers that I received evidence from, there was no or very little financial impact from the short notice given to them of De-listing, due to the fact that they were able to divert their products to other retailers or because in some cases Co-op agreed to take additional stock from the Supplier or compensate them for excess packaging.

27.2 Some of the larger Suppliers were not concerned about the potential financial impact of reductions in volume for particular products, provided that the overall volume of products being ordered from them was increasing. For them, the financial impact of significant reductions in orders for one or a few products was not significant when considered in the context of their wider business with Co-op. For example, one Supplier incurred a drop in distribution for a product with no notice which the Supplier estimated resulted in a loss of sales totalling hundreds of thousands of pounds. However this was not considered an issue for this business given the wider business with Co-op being worth several million pounds.

27.3 However for a number of Suppliers this was not the case and the lack of notice of a significant reduction in orders or removal of a product resulted in them incurring significant costs which might have been avoided had they received reasonable notice. For example:

- One Supplier was informed of a drop in distribution that resulted in wastage of approximately 15% of its total production of that product. Notice had been given too late in the production cycle for this to be avoided. The Supplier estimated the cost of this was more than £200,000;

- One Supplier received less than six weeks’ notice of a drop in distribution which cost it tens of thousands of pounds due to residual stock; and

- One Supplier received no notice of the removal of some products which amounted to over 20% of its sales to Co-op.

28. Wastage

28.1 For several Suppliers, the short notice given of distribution reductions or product removals resulted in wastage of packaging and products. I saw evidence of occasions when excess packaging had to be sent to landfill, excess stock had to be broken down and raw ingredients sold off at a loss; and minimum production orders meant that after reductions in distribution at short notice, each production run resulted in wasted products.

28.2 On a number of occasions when wastage issues arose I saw evidence of good practice from Co-op where it sought to mitigate the impact on Suppliers and avoid waste. I saw several examples of Co-op taking excess packaging from the Supplier or increasing orders leading up to the date of De-listing, which helped minimise wastage and also more generally the impact on Suppliers of De-listing.

28.3 However I have also seen examples where Co-op did not assist Suppliers, which resulted in a greater financial impact on the Supplier as well as wastage of the products. I saw occasions when Suppliers were left with excess packaging and products due to the fact that De-listing was imminent yet at the same time, the volume of product ordered in the period immediately before De-listing was reduced significantly.

29. Administrative burden and associated costs on Suppliers

29.1 In addition to the direct financial impact of a failure to give reasonable notice of De-listing, there were other consequences for the resources used by the Supplier to supply products to Co-op. These included short notice adversely affecting the efficiency of a Supplier’s business, as it was unable to effectively plan to optimise production in its factory, and direct labour requirements having to be adjusted by a Supplier at short notice. Another Supplier reported that the unexpected disruption to orders had negatively affected its stock management, including its stock holding, date rotation management and raw materials.

29.2 A couple of Suppliers commented on the resources involved in getting information from Co-op, including to establish whether or not De-listing had occurred and/or the extent of distribution changes. This was evident from some of the written correspondence that I received.

29.3 Changes to distribution without reasonable notice not only affected the Supplier when order volumes were significantly reduced, but also had an impact on both the Supplier and Co-op if the order volumes were significantly increased at short notice. I found several examples of Suppliers being unable to meet the demands for increased orders at short notice, which was detrimental to both the Supplier and Co-op, as potentially more products could have been sold if more notice of the increased orders had been provided. On one occasion the orders for a new product increased so significantly and so quickly that the Supplier could not keep up with the orders and the product ended up being permanently De-listed.

30. Uncertainty created for Suppliers

30.1 The frequency and extent of changes to orders that some Suppliers experienced from Co-op, and the lack of notice of these changes, meant that some Suppliers felt uncertain about what stock they would be required to provide to Co-op at any given time. One Supplier described its orders from Co-op as “feast or famine” without any way of knowing what was coming. This meant that sometimes a product would go out of stock because of high orders and sometimes the same Supplier would be sat on products for months.

30.2 Several Suppliers explained that if they had had more notice of the likelihood of De-listing, they would have been able to do more to mitigate against any adverse impact from it. For example they would be better prepared to divert products to another customer and could have made earlier enquiries with Co-op about using up stock through promotions. One Supplier stated that if all Retailers had provided it with the paucity of information that Co-op had then it would be “hard to manage”. Another stated that if Co-op had been a larger part of its business then it would not have been able to function with the 12 weeks’ notice that was generally given for De-listing its products.

Root causes of De-listing without reasonable notice

31. Compliance risk management, proactively undertaken at all levels in the business

31.1 I find that there was inadequate governance to oversee and manage compliance with the De-listing requirements of the Code. Co-op did not take adequate steps to reassure itself that it was acting in compliance with paragraph 16 of the Code.

31.2 As a result Co-op was slow to recognise when problems with its Code compliance did exist. In addition, when problems were identified Co-op either did not appreciate the level of change that was required or did not have the systems in place to implement those changes.

31.3 For example:

- Co-op had identified from an internal audit that was discussed within the business in November 2017 that 96% of buyers were failing to give sufficient notice of De-listing decisions against its own policies. It was suggested internally in November 2017 that this indicated a systemic or process issue. Yet these issues were not adequately identified and addressed by the time of the launch of my investigation in March 2018. Co-op reported to me in January 2018 that between July 2017 and October 2017 only 80% of its De-listing decisions in relation to branded goods and 3% in relation to own-label goods were made in compliance with its own policy.[footnote 2]

- Weaknesses in Co-op training and policies for buyers about De-listing (see paragraph 34 below) remained in place throughout the period under investigation until January 2018.

- In relation to the minimum notice periods in the Process document, I had written to Co-op on 11 October 2016 stating “that a two-week minimum notice period for de-listing branded products is unlikely, except in very limited circumstances, to be reasonable notice”. In response to my concerns, Co-op advised me that it would review the two-week minimum period it had been applying for De-listing branded goods. Yet the Process document was not revised until July 2017 and when it was, the only significant change was to increase the minimum notice period from two weeks to four weeks. Internal correspondence between employees at a senior level within Co-op indicated that they felt that by doing this and reminding buyers of the need to consider each change on a case-by-case basis they had addressed the problem. Further changes were not made to the document until 2018.

- Co-op became aware of limitations to its systems, including the fact that the process for range reviews restricted the notice period for distribution changes to around three weeks. Yet the initial response was to tell buyers to use what information they had to try and give as much notice as possible, even though this information might turn out to be incorrect.

31.4 The poor management of compliance with paragraph 16 of the Code within the business also meant that Co-op failed properly to identify and oversee De-listing decisions that were effectively being taken outside the commercial team, for example where swap-outs were occurring at a local level and changes to Co-op orders from independent co-operative societies had a significant impact on Suppliers. Co-op has acknowledged to me that its oversight of its different functions in its communications with Suppliers has been “fragmented”. It did not ensure that significant events such as range reviews and the sale of stores included adequate consideration of any potential impact on its compliance with paragraph 16 of the Code.

31.5 A number of Co-op employees explained to me that before and during the period under investigation Co-op was doing its best to turn around the business and its focus was on doing the right thing for its customers and driving profits. It is apparent that other matters took higher priority than did ensuring compliance with paragraph 16 of the Code. There was accordingly not enough focus within the organisation on compliance with the Code and Code compliance was to some extent a box-ticking exercise. Co-op acknowledged to me that “in delivering the rescue and recovery of our Co-op we have done too much too quickly and not properly engaged with or embedded the Code.”

31.6 Co-op also acknowledged that “we mistakenly relied on a wrongly held belief that, because of our brand values and relative scale in the market, suppliers would actively highlight inefficiency or unexpected costs or other concerns that they might have.” My impression from the evidence is that because of the values that Co-op believes it stands for, there was a presumption internally that it would be acting in a reasonable and Code-compliant manner. This has been found to have been incorrect but it appears to have led to inertia about checking compliance and challenging procedures and decisions internally. While I accept that none of the issues I have identified were malicious or intended to result in gain for Co-op, this does not excuse the failures to identify and address the issues.

31.7 The failure of Co-op proactively to manage its compliance risk in relation to paragraph 16 of the Code explains why Co-op did not identify many of the issues arising until they were raised with Co-op by me. Even when I did make Co-op aware of the issues they were not adequately dealt with, despite repeated guidance from and engagement with me. Co-op did not appear to have an effective system to identify, escalate and address issues arising that might potentially be of real significance to the business. As one employee acknowledged, the issues I was raising “shouldn’t have come as a surprise, but [they] did”.

32 Legal, compliance and audit functions working to support Code compliance

32.1 I find that there was insufficient legal, compliance and audit support to deliver compliance with paragraph 16 of the Code and prevent De-listing without reasonable notice.

This meant that the failure to give reasonable notice of De-listing and the root causes of these failures continued over a sustained period of time without effective internal challenge.

If these parts of the business had been more focused on the application of paragraph 16 of the Code to the buying team, the wider programmes being implemented by Co-op and the day-to-day practices of the commercial team then the problems that arose should have been identified and dealt with at an earlier stage. The weaknesses with the training and policies, and the IT systems that made compliance with paragraph 16 very difficult, should have been raised and addressed earlier. Processes that were operating in a way that inevitably meant Co-op could not comply with its own policies should have been challenged.

I was told that during the period under investigation a significant number of members of the commercial team were raising questions and asking for support on the interpretation of issues relating to the Code. This should have been a clear indication that there was a need for further, more effective training, but this does not appear to have been identified by Co-op.

It is for these reasons that I consider it so important that Retailers understand from the published case studies and my discussions with them the requirement to ensure that their legal, compliance and audit functions are sufficiently connected to commercial initiatives that they work effectively together to ensure Code compliance.

33. Internal systems and processes working to support Code compliance

33.1 Throughout my investigation I received evidence about the poor functioning of Co-op IT systems and how they were no longer fit for purpose. Co-op employees described how the IT systems were “held together with sellotape and string” and “make it so difficult for employees to do their jobs”.

I find that Co-op IT systems contributed to its failure to comply with paragraph 16 of the Code.

33.2 One of the main issues that I identified with the system was the absence of one central IT system which could be accessed by all the relevant Co-op employees who were dealing with Suppliers. This meant that any changes to product listings made by teams outside the commercial team (such as Supply Chain and local stores) or even outside Co-op (such as independent co-operative societies) were not necessarily known by the commercial team and not communicated to the Supplier. Even within the Co-op commercial team there was no central IT system on which all relevant documentation for a Supplier would be stored. Each team within the commercial area of the business had a shared drive which could be accessed by anyone within that team. However the availability of material on this shared drive was dependent upon current and former team members having saved the relevant material on this drive.

33.3 Co-op told me that certain information, such as terms relating to the Supply Agreement, was meant to be stored on the Co-op portal and available to Suppliers. However the evidence I received was that the information on the portal was often incomplete and only available to the person who had put it on there. This meant that Suppliers and new buyers could not necessarily access communications with Suppliers that had been conducted by previous buyers and there was no complete record of Supplier contracts and terms and conditions in one place. This was information that was relevant to the buyer’s engagement with the Supplier and their understanding of the Supplier’s circumstances and relationship with Co-op.

33.4 This lack of central IT systems and storage may have contributed to the impression of disorganisation that many Suppliers had of how Co-op operated as a business. One Supplier described Co-op as the “left hand not knowing what the right hand is doing” and another stated that “Co-op changes their mind dependant on the weather”.

33.5 The Co-op IT systems played a key role in the range review process. My understanding is that buyers would rank the products in their category according to a number of factors and these rankings were then entered onto the IT systems. The IT systems would produce revised distribution figures for each product based on those rankings and the proposed lay-outs in stores. These distribution figures would then usually be fed back to the Supplier.

33.6 It is clear from the evidence I have seen that the IT systems restricted the notice that could be given to Suppliers of distribution changes. The confirmed figures for distribution changes were only available approximately three weeks before the implementation of the range changes. This was accordingly the maximum notice that Co-op could give of drops in distribution for a product or products which might amount to a significant reduction in orders for that Supplier. These systems did not allow consideration of what might be reasonable notice of any De- listing for a Supplier. They also effectively prevented Co-op from delivering on its own internal policy of giving 12 weeks’ notice of De-listing of an own-label product and four weeks’ notice for branded products (which had been increased from two weeks in July 2017).

33.7 Co-op was able to provide estimated distribution figures before the final figures were confirmed based on the distribution of a product previously ranked in that position. However the evidence I have received is clear that these were only indicative numbers and at times were significantly different from the final distribution figures that were produced by the system. They were accordingly not figures that could be relied upon by Suppliers to plan their future supply to Co-op.

33.8 In some cases Co-op wrote to Suppliers about retrospective changes, sometimes over two months after the implementation of the decision. Suppliers were contacted about “systems errors” which had created this problem. One Supplier spoke with Co-op about De-listings that had occurred without any notice, in which Co-op had told it that the systems for range reviews had not been set up to safeguard against errors in the removal of products. Therefore it appears that errors in the system on occasions resulted in the removal of products without any notice at all being given to Suppliers.

33.9 Another internal process that I identified as unhelpful to Co-op in seeking to manage its compliance with the Code was the absence of dates from important internal guidance. This meant that it was not possible for employees and Suppliers to know whether they were referring to current material. It should have been possible to establish whether everyone was working from the same, current version of a document.

34. Training on paragraph 16 of the Code

34.1 Another safeguard for Co-op in its management of its Code compliance risk should have been its training of individual employees to ensure that they each understood how to implement the Code in their day-to-day roles and could identify occasions when there was a risk of the Code being broken, particularly bearing in mind the published De-listing Guidance and Supplementary Guidance. However the evidence that I found was that Co-op training not serve this purpose in respect of paragraph 16 of the Code. One Co-op employee explained that training used to be one session which “didn’t have the scope or the time to get into the detail” but that despite this “it was rare to fail the tests”. The training was not tailored to the role that buyers had to undertake and there was no assessment of how useful the training was to buyers. A Co-op employee acknowledged that “with hindsight the [commercial] team should have had more say about whether the training was realistic in their world”.

34.2 I find that the training was inadequate to equip buyers to identify decisions that might result in a significant reduction in the volume of a product or products ordered from a Supplier.

The training material stated in relation to a significant reduction in volume that Co-op had “set this level at c.20%.” It did not adequately address the need for consideration of each situation on a case-by-case basis, indicating the need for review “particularly if close to a 20% reduction” but not in other circumstances. Co-op employees who I spoke to accepted that buyers had not been adequately trained to recognise that relatively low percentage changes in distribution could still amount to significant reductions in volume for a Supplier and that at times there was a failure to recognise the potential significance of drops in distribution of products.

34.3 I find that the training was also inadequate to equip buyers as to how to consider on a case-by-case basis what might amount to reasonable notice of De-listing for any particular Supplier.

For example, the 2016 training referred to the Co-op standard terms and conditions stating that “reasonable notice” for De-listing was 12 weeks for Co-op branded products and two weeks for all other groceries. This contributed to the minimum notice periods of two weeks (later four weeks) and 12 weeks set out in the Process document being applied as standard notice periods on the mistaken basis that this discharged the duties of Co-op under paragraph 16 of the Code. It also meant that Co-op buyers did not understand the engagement with Suppliers that was required to assess significance and reasonable notice.

34.4 I find that the failures in training were compounded by the weaknesses in the Co-op policies and process documents, which did not adequately equip buyers properly to perform their roles and to assess significance and reasonable notice in compliance with the Code.

34.5 The Process document was described to me by Co-op as providing an “explanation of the process to be followed for De-listing a product or Supplier”. My understanding is that this was the primary document for guiding buyers as to how to handle De-listing decisions. I have been provided with copies of the versions of the document that were in place during the period under investigation.

34.6 Until January 2018 this document set out that a reduction of 20% or more to the total volume of groceries supplied to Co-op by a particular Supplier would amount to De-listing. There was no guidance given about any other factors to be taken into account when assessing the significance of planned changes, nor was any direction given to buyers to engage with Suppliers about significance or reasonable notice. As stated previously, the document set out that the minimum notice periods to be adhered to were 12 weeks for own-label products and two weeks (later four weeks) for branded products, although it was recommended that buyers gave as much notice as was reasonably practicable. There was no guidance given to buyers as to how they should assess reasonable notice. Co-op accepted that its Process document had not sufficiently encouraged buyers to consider each De-listing decision on its own merits.

34.7 A further draft of the Process document was produced in January 2018 which addressed these issues.

34.8 Training and policies were particularly important for buyers who were new to the commercial team or moved to a new category in which they were not familiar with the Suppliers and their supply chains. I have also identified at paragraph 21.3(b) the relevance to Co-op compliance with paragraph 16 of the Code of parts of the Co-op business beyond the commercial team and in the case of the independent co-operative societies, beyond the regulated Co-op entity. My concerns about the training and policies provided to Co-op employees extends to those Co-op employees outside the buying team whose conduct was relevant to compliance by Co-op with paragraph 16 of the Code.

34.9 The failure properly to equip employees with the knowledge required to ensure compliance with paragraph 16 meant that they did not identify when practices and systems were in place which thwarted their ability to act in compliance with the Code. For example, I saw very little evidence of buyers raising concerns about the systems restricting the notice that could be given of distribution changes for a range review to around three weeks, even though this inevitably led to the buyer being unable to give reasonable notice of De-listing on some occasions. I have previously expressed my view that “Individuals within retailers should be sufficiently aware of the Code and empowered in their roles meaningfully to challenge any commercial or other initiative by the retailer which may put them in breach of the Code. This extends beyond the Code Compliance Officer role and the legal and compliance function of the retailer and includes individuals at all level in the business.”

34.10 I find that individuals from both within and outside the Co-op buying team were inadequately trained to recognise and raise concerns about Code compliance.

35. Communication between the Retailer and Suppliers facilitating Code compliance

35.1 I find that at times there was a lack of communication by Co-op with Suppliers about decisions that might amount to De-listing. This meant that Co-op did not always have the information it needed to determine significance and reasonable notice on a case-by-case basis.

35.2 Co-op knew that its systems were in some ways inadequate and meant that limited notice could be given to Suppliers of changes during range reviews. Yet in many cases it did not attempt to compensate for this through enhanced engagement with Suppliers. Many Suppliers were not given the opportunity to explain or discuss the impact of De-listing decisions before they were made and notice periods fixed. In reaching these decisions, Co-op frequently relied upon its own business needs, without taking into account any information from the Supplier.

35.3 A number of Suppliers reported that they had difficulty getting hold of buyers, including when seeking confirmation about whether or not a decision had been made to De-list a product. Co-op buyers were described by several Suppliers as “time-poor” and “unresponsive”, with one Supplier having no contact with its buyer for several months.

35.4 This issue was not unique to smaller Suppliers, even some of the larger Suppliers found it hard to engage day-to-day with Co-op. It does appear however that it was harder for smaller Suppliers to escalate significant issues and access the information they required. One Co-op employee explained to me that the size of the Supplier would affect who they had access to within the business. The larger Suppliers would have additional lines of communication at a more senior level within Co-op, which was a level of access not available to the smaller Suppliers. The larger Suppliers may accordingly have been able more readily to access the individuals who they needed to engage with to get issues resolved.

35.5 Some Suppliers felt that the reason why they received poor communication from Co-op was that its buyers were inexperienced and that as a result, they shied away from difficult conversations, for example about potential De-listing. Several Suppliers reported high turnover of the buyers that they were dealing with, which made communication even harder and meant that they felt like they had to start afresh every time they were notified of a new buyer. It was considered particularly important among Suppliers in the fresh produce sector that buyers understood the products and relevant growing cycles in order to discuss, for example, reasonable notice of any changes to orders. If buyers were inexperienced in this area, they would not necessarily appreciate the importance of notice periods in relation to key decision points about the next season’s supply or the Supplier’s particular circumstances. My Supplementary De-listing Guidance makes clear how important it is to understand growing cycles in the fresh produce sector when making De-listing decisions. Co-op was unlikely to be able accurately to assess significance or reasonable notice unless it had engaged with the Supplier before giving notice of De-listing.

35.6 Many Suppliers reported to me that they did not receive the information from Co-op that they needed in order to operate most efficiently and to assess how their relationship with Co-op was progressing. For example, frequently Suppliers reported difficulty in obtaining information about depth of distribution, rate of sale and wastage. A number of Suppliers reported building relationships with other parts of the Co-op business such as the Supply Chain teams in order to obtain information that they needed to anticipate order volumes and identify supply issues. One Supplier reported having to visit individual Co-op stores to establish where its products were being stocked and told me that it had to visit Co-op depots to find out what its stock levels were. This information was important to enable Suppliers to understand the risks and costs of trading with Co-op. Suppliers reported that with more information from Co-op, they would have been better able to manage their supply chain, address issues, anticipate range changes and suggest new ways of working with Co-op.

35.7 Not all Suppliers felt that they received inadequate information from Co-op, with some stating that it was “middle of the table” in comparison to other Retailers and some feeling that overall communication was good. I did not discern any pattern in which Suppliers felt that they received inadequate information. However it was suggested to me by one Co-op employee that perhaps Co-op had focused too much on its relationships with large, strategic Suppliers and not enough on the numerous smaller Suppliers that support the business and that as a result, smaller Suppliers may have had less access to information. A number of the larger Suppliers that I spoke to confirmed that they paid for access to additional data to assist them with their category knowledge and planning.

35.8 Moreover, because at Co-op other parts of the business outside the commercial team could make decisions that affected ranging, it was not possible for Co-op to be assured that all information relevant to the assessment of significance was properly taken into account. For example, in relation to swap-outs made at a local level (see above), this meant that neither the buyer nor the Supplier would necessarily have accurate information available about current distribution levels on which an assessment of significance could be based.

Findings of fact on variation of Supply Agreements without reasonable notice

What the Code says:

3. Variation of Supply Agreements and terms of supply

If a Retailer has the right to vary a Supply Agreement unilaterally, it must give Reasonable Notice of any such variation to the Supplier.

Principal findings on variation of Supply Agreements without reasonable notice

36.1 If a Retailer has the right to vary a Supply Agreement unilaterally, it must give reasonable notice of any variation to a Supplier. What constitutes reasonable notice in each case depends on the terms that govern the Supplier’s relationship with the Retailer and in particular when the Supplier will next have an opportunity to renegotiate them. Suppliers on fixed cost contracts in particular do not have the ability to renegotiate the cost price at which they supply groceries because their Supply Agreement specifies a fixed cost price for a given period or ties any fluctuations exclusively to changes in specified commodity prices.

36.2 I find that Co-op unilaterally and without reasonable notice varied its Supply Agreements with Suppliers by its application of depot quality control charges and benchmarking charges. This conduct was not compliant with the Code. I find that Co-op broke paragraph 3 of the Code. I find that this caused particular difficulties for Suppliers with fixed cost contracts, which would not have been able to amend their cost prices accordingly.

Co-op has acknowledged that it “did not provide suppliers with sufficient opportunity (where any opportunity existed) to factor these charges into their cost prices and renegotiate the terms and commercial arrangements of supply”.

Depot quality control charges

36.3 The evidence I received indicates that some Suppliers were not expecting depot quality control charges to be applied and learned about the charges only after the funds had been deducted. A number of Suppliers did not know why they had been charged depot quality control charges and did not know where to find details to explain the circumstances in which they would be charged. These Suppliers described the system for applying depot quality control charges as “unclear” and “vague”. Some Suppliers did not therefore have the opportunity to renegotiate their terms of supply to take into account depot quality control charges. This was not uniformly the case, as other Suppliers told me that they had received notice of the application of quality control charges via the portal and/or by email. Some Suppliers understood the purpose and costs of the charging regime.

I find that in some cases Co-op did not provide sufficiently clear or detailed information to Suppliers about the depot quality control charges to enable them to form reasonable estimates of the amount of charges.

36.4 I find that Co-op buyers were not aware of the likely amount of depot quality control charges and were accordingly unable to give notice of them.

In at least two instances that I saw, Co-op buyers were not aware of what depot quality control charges were. This is because the charges were applied by depots which are part of the primary network logistics function within Co-op that is distinct from its commercial team. One buyer described this function as a “separate part of the business” after responding to a Supplier’s query about an invoice for depot quality control charges by stating “I have absolutely no idea where it has come from??” Buyers did not have access to information about the charges because they were applied through a shared financial service centre rather than through the commercial finance function which buyers used. The evidence I received suggests that independent co-operative societies operated a different system for applying depot quality control charges that also did not involve buyers. In correspondence with Co-op head office, the Quality Assurance Manager for one of the independent co-operative societies apologised for not having sent a rejection report and explained: “I am never told who at Manchester is doing what…”. Co-op admitted during my escalation of the issues that there was an “internal breakdown in communication between our Technical Team who process the Depot QC charges and our Buying Team who held the knowledge as to how frequently (and what elements) of contracts were re-negotiated.”

36.5 I find that Co-op did not appear to consider what constituted reasonable notice of the application of depot quality control charges for Suppliers on fixed cost contracts because of a failure to understand the Code.

A Co-op employee held the view that a Supplier that had a Supply Agreement with Co-op which made provision for cost price changes in the event of currency or commodity price fluctuations would have the ability also to reflect charges or any changes to them in its cost price. That however did not appear to be the case in the relevant contract, which specified a limited list of factors that could be taken into account. Moreover, another Co-op employee acknowledged to me that if a Supplier had a weekly variable cost price arrangement with Co-op and tried to negotiate cost price increases on the basis of quality rejection charges it had received, the Supplier would probably have been told by Co-op to “go do a running jump.” This failure properly to interpret and apply the Code led to a failure to give reasonable notice of depot quality control charges and contributed to the delay in Co-op adequately compensating Suppliers for depot quality control charges applied without reasonable notice, as discussed further below. Co-op has now acknowledged that where a Supplier’s contract is subject to currency or commodity-based cost price changes, it does not necessarily follow that a Supplier has a realistic opportunity to vary its cost prices to take into account charges.

Benchmarking charges

36.6 Several Suppliers that had received benchmarking charges had not agreed to pay these charges to Co-op and had not been told about the purpose, amount and frequency of the charges. One Supplier who was charged for benchmarking in 2016 and 2017 told me that they were “never informed of such charges, and would certainly never have agreed to them.” I have seen evidence that one Supplier responded to the proposal for benchmarking from Co-op, stating “This is something we have never run previously or commercially agreed to…” and requested “any information” on the benchmarking programme. Some Suppliers were not aware that benchmarking charges might be applied until they received email notifications stating that benchmarking was to occur in a matter of days and asking them to supply products, or even in some cases until after the funds had been deducted. This was not the case across the board, though: some Suppliers told me that they had received notice of the application of benchmarking charges via the portal and/or by email.

36.7 I find that Co-op buyers were not aware of the likely amount and frequency of benchmarking charges and were accordingly unable to give notice of them.

This is because the Customer Benchmarking team which selected the products to be tested and for which Suppliers would be charged did not appear to involve or communicate with Co-op buyers. I have seen evidence that some buyers did not have access to the Co-op document which set out the charges which a Supplier to Co-op could expect to pay (the Charges Matrix) and were not able to provide copies to Suppliers.

36.8 I find that in some cases Co-op did not provide sufficiently clear or detailed information to Suppliers about the customer benchmarking programme and the associated charges to enable them to form reasonable estimates of the amount and frequency of charges.

Some Suppliers did not understand the rationale and process for the benchmarking programme. One Supplier described the benchmarking programme as “a grey area” and another told me that they were “unclear what the charges are for, [and] which products they apply to”. Several Suppliers asked for an explanation of the benchmarking charges so that they could calculate what they could expect to be charged on an ongoing basis. This led one Co-op buyer to acknowledge that some Suppliers “aren’t sure on what they are being asked to agree to”. I have reviewed Co-op documentation relating to benchmarking charges and I do not consider that it was clear.

36.9 I find that Co-op did not appear to consider what constituted reasonable notice of the application of benchmarking charges for Suppliers on fixed cost contracts because of a failure to understand the Code.

Extent and scale of variation of Supply Agreements without reasonable notice

37. I have only received evidence from a selection of Suppliers that supply Co-op and I am therefore unable to make a definitive assessment as to the scale of variation of Supply Agreements without reasonable notice.

38. Depot quality control charges

38.1 The failure to give reasonable notice of depot quality control charges affected Suppliers of fresh produce and Suppliers of meat. Suppliers of other groceries were not affected. Co-op documents indicate that in October 2017, Co-op received from Suppliers an average of £112,000 per month for depot quality control charges and that this affected on average 30 Suppliers per period. Co-op noted that there are some Suppliers that have products rejected on a regular basis. I have not been able to determine from the information I have been given the total depot quality control charges applied during the period under investigation that were refunded by Co-op because they were applied without reasonable notice. However, more than 70 Suppliers received refunds totalling £289,272 relating to depot quality control charges applied without reasonable notice and it is clear from the data that a significant proportion of these were applied during the period under investigation.

38.2 I note that for some of the period under investigation, Co-op did not apply depot quality control charges. As a result of my having raised concerns with Co-op about how it notified Suppliers about depot quality control charges, Co-op suspended depot quality control charging between 1 August 2017 and 15 February 2018.

39. Benchmarking charges

39.1 The failure to give reasonable notice of benchmarking charges affected only Suppliers of own-label products. A significant majority of own-label Suppliers of non-fresh groceries from which I received evidence had paid benchmarking charges. Co-op has informed me that in 2016 it carried out 918 tests; in 2017 it carried out 1,103 tests and in the first eight months of 2018 it carried out 572 tests. In December 2017, Co-op paid £242,235.16 in refunds to 55 suppliers in respect of benchmarking charges that were applied without reasonable notice for the testing of 472 products during the period under investigation.

39.2 I note that Co-op suspended benchmarking charges between 1 November 2017 and 15 February 2018. Co-op has also informed me that no benchmarking tests were conducted between 16 February 2018 and 8 March 2018.

Impact on Suppliers of variation of Supply Agreements without reasonable notice

40. I have set out in this section the different types of impact that I have identified, under the headings financial impact, administrative burden and associated costs on Suppliers, and uncertainty created for Suppliers.

41. Financial impact

41.1 In assessing the financial impact of charges that were applied without reasonable notice, I have taken into account information from Co-op and Suppliers. I have borne in mind the confirmation from Co-op that neither depot quality control charges nor benchmarking charges were intended as a means of generating profit, but rather to “incentivise suppliers to meet agreed standards” and to “share the costs of product quality development and improvements with the aim of generating improved sales for the supplier and Co-op” respectively.

Depot quality control charges

41.2 Some Suppliers paid very large amounts of money in depot quality control charges that were applied without reasonable notice. It is likely that the removal in July 2015 of the £200 cap on the maximum charge per delivery significantly increased the amounts that Suppliers were charged which they had not been expecting to pay. One Supplier was refunded over £36,000, one was refunded over £22,000 and four were refunded between £8,000 and £18,000 by Co-op to compensate for charges including those applied without reasonable notice during the period under investigation.

41.3 Suppliers from which I received evidence gave mixed views as to the significance of the amounts they had been charged by Co-op without reasonable notice. One Supplier which considered that it had not been given reasonable notice of the charges commented that “the punishment did not ft the crime” and that the amount charged made its continuing supply commercially unviable because the charges amounted to 20% of its profit on its supply of one product line to Co-op. However, the Managing Director of another Supplier only learned that depot quality control charges had been applied at all because of my asking him about them as part of this investigation, and confirmed that if the charges had been a serious issue for the business, he would have known about them. Similarly, other Suppliers thought that the amount of the quality control charges was not significant enough to warrant being challenged, which indicates that the financial impact was considered by some Suppliers to be negligible or unproblematic. A significant number of Suppliers considered depot quality control charges simply to be a cost of doing business and not a battle worth having for the amount of money in question and when looking at the bigger picture of the relationship with Co-op.

Benchmarking charges

41.4 Some Suppliers received large sums as refunds for benchmarking charges which Co-op determined had been applied without reasonable notice. The amount refunded to one Supplier was more than £21,000, representing benchmarking charges applied during the period under investigation. Six other Suppliers received refunds of more than £10,000 each. I received mixed evidence as to the significance of the financial impact of Co-op imposing benchmarking charges without reasonable notice. A number of Suppliers told me that the benchmarking charges that Co-op had applied without reasonable notice had not had a material negative impact on the viability of the products they supplied to Co-op. Some Suppliers again considered the charges simply to be a cost of doing business or that the amounts being charged were not significant enough to warrant being challenged. Although this evidence suggests that Suppliers considered the charges not to have had a significant commercial impact on their businesses, it also indicates that some felt that the charges were an additional cost that Suppliers were expected to absorb in order to maintain their relationship with Co-op.

42. Administrative burden and associated costs on Suppliers

42.1 I received evidence that the failure of Co-op to give reasonable notice of the application of depot quality control charges and benchmarking charges caused some Suppliers’ employees to spend time checking records and/or trying to challenge charges. This resulted for a small number of Suppliers in time being diverted from other activities. In assessing this impact, I have borne in mind the view of a Co-op employee that smaller Suppliers may have had less access to information and buyers and would therefore have been more likely to experience these administrative challenges.

43. Uncertainty created for Suppliers

43.1 Suppliers were sometimes uncertain as to how the depots would interpret and apply the quality specifcation to the products they supplied and whether as a result depot quality control charges were likely to be applied in a given situation. I received evidence that Co-op depots did not demonstrate a consistent approach to applying the percentage defect level to either cases or palettes within a delivery. In these circumstances one Supplier considered ending its supply of one product to Co-op on the basis that the cost of charges could easily exceed the price of the product.

43.2 I also received evidence that Suppliers did not know what the timetable of customer benchmarking would be and when they would be expected to pay the costs associated with it.

43.3 It was accordingly clear to me that a number of Suppliers were not provided with adequate information about the amount and frequency of charges so as to be able to form estimates of the likely cost they would be required to pay. This meant that Suppliers had to operate in an uncertain environment in which they would be expected to absorb unforeseen costs.

Root causes of variation of Supply Agreements without reasonable notice

44. Compliance risk management, proactively undertaken at all levels in the business

44.1 One of the root causes of the failure by Co-op to give Suppliers reasonable notice of the application of depot quality control and benchmarking charges was a lack of recognition across the Co-op business that it had proactively and consistently to manage its Code compliance risk. There does not appear to have been a clear structure of roles and responsibilities to ensure that this was done.

44.2 I was not shown any evidence that the Co-op CCO or its audit function had the opportunity to risk-assess or contribute to the formation of the commercial and operational initiatives. Co-op failed to demonstrate to me its oversight of the proposed charges, when they would be applied and with what notice. I consider this is one reason why there was a failure to consider the general risk of non-compliance with the Code before the introduction and application of the charges for the first time. This may also be a reason why Co-op failed to consider what would constitute reasonable notice of charges for each Supplier depending on the contractual position of each one.

44.3 I find that Co-op failed to identify the risk to Code compliance associated with depot quality control and benchmarking charges being applied not by buyers but by other parts of the Co-op business or in the case of depot quality control charges, the independent co-operative societies.

They were not adequately trained, or not trained at all, on the Code, specifically the requirement to give Suppliers reasonable notice of charges. The buyers, who were trained on the Code, were not sufficiently aware of the likely amount and frequency of charges to provide the necessary information to Suppliers. This combination of risk factors was not recognised or addressed by Co-op.

44.4 I did not see evidence that buyers considered the risk of non-compliance with the Code when they became aware from Suppliers that charges had been applied. Some buyers did not have access to the Charges Matrix but did not appear to have escalated this issue. Furthermore, it was the responsibility of Co-op senior management to commission audits as necessary. The review that was commissioned after I raised my concerns was carried out by the commercial team rather than the audit team and was not sufficient to address the issues. As a result a further review by the audit team was undertaken later.

45. Legal, compliance and audit functions working to support Code compliance

45.1 There are a number of ways in which the legal, compliance and audit functions at Co-op failed to work together to support compliance with paragraph 3 of the Code.

45.2 I find that Co-op legal, compliance and audit functions did not appear adequately to have worked together to develop or to oversee any policy or rationale governing the circumstances in which charges would be applied.

I have seen correspondence in which a senior Co-op executive commented that the team “at times feel there is a lack of clear guidance and they experience a high level of challenge with an inappropriate level of support.” The failure of Co-op to give reasonable notice of the application of charges was in part caused by the absence of a policy that would promote a culture of Code compliance. For example, one version of the Co-op Customer Benchmarking manual which I have seen set out details of the three tiers into which products would be categorised for benchmarking purposes. It stated that Tier 1 products (“commodity / spec bought / minimally processed lines”) were not to be benchmarked; Tier 2 products (“primal protein and produce lines”) were to be benchmarked annually; and Tier 3 products (“all formulated lines and products which undergo full Customer Benchmarking”) were to be benchmarked annually or “in line with Stage & Gate”. The cost to Suppliers was stated as £150 for Tier 2 products and £500 for Tier 3 products. Co-op employees acknowledged that the Charges Matrix “doesn’t make clear on refection what is a Tier 2 and Tier 3 product” and in these circumstances Suppliers were not able to anticipate likely costs. I have found that the following situations arose because of the absence of a clear rationale as to when benchmarking charges would be applied:

- Co-op charged for the testing of a Supplier’s product when the Supplier had already undertaken an in-house benchmarking process in conjunction with Co-op;

- A product which scored well on testing that the Supplier was charged for was almost immediately notified for De-listing by Co-op, raising questions as to the purpose of benchmarking;

- Co-op informed a Supplier that its product was to be benchmarked but there was no comparable product against which to do this, so the decision to benchmark was withdrawn after having been challenged; and

- Co-op informed Suppliers that their products were to be benchmarked but the relevant products had by that time been De-listed.

45.3 I also received evidence that Co-op depots did not adopt a uniform interpretation of the percentage defect level to be applied to deliveries, leading to inconsistent application of depot quality control charges. Two Suppliers “educated” the depots to apply the quality specification appropriately. In one case, as a result of challenge by a Supplier, Co-op changed the quality specification so that the Supplier could continue supplying products without incurring depot quality control charges. This indicates the absence of any clear and applicable policy or consistent quality controls.

45.4 In an attempt to address my concerns, Co-op Group Internal Audit produced a report in or around February 2018 to assess a number of controls relating to benchmarking and depot quality control charges. The report identified shortcomings of the process documents including that they did not “Consider actions required if suppliers disagree with these charges.” Co-op documents suggest that it had in place a process whereby a Supplier was given 30 days’ notice of a charge before an invoice was generated so that it could dispute a charge through the Supplier portal. However the report stated that “Most suppliers are automatically contra’d against monies we owe them within an average of 7 days. Appropriate supplier notification is given with respect to QC charges, but not for Benchmarking charges.” The controls in relation to benchmarking charges were identified as being “ineffective” and two options were suggested so that Suppliers would have 30 days’ notice to dispute a charge. A further report by Group Internal Audit stated in relation to the reintroduction of benchmarking charges (following the suspension of the charges) that “There is a significant risk that Benchmarking charges will be unilaterally deducted unless an additional control is designed that ensures the supplier is notified of the charge and given reasonable notice before the monies are deducted.”

45.5 Furthermore, the legal, compliance and audit functions within Co-op did not operate together effectively to remedy the issue of non-compliance with paragraph 3 of the Code after I had alerted Co-op to my concerns and Co-op had acknowledged that reasonable notice of the charges had not been given. This was in part caused by the relevant teams’ failure to understand that the requirement to give reasonable notice and the calculation of compensation for the lack of reasonable notice necessitated an assessment of each Supplier’s contractual position. In late December 2017 and early 2018 Co-op conducted a review of Suppliers that had been charged depot quality control charges and benchmarking charges and calculated the refunds due to the Suppliers. Co-op had initially assumed that Suppliers had the opportunity to vary their cost prices to take into account charges whenever a revised cost price was entered onto the system for other reasons. Co-op has now acknowledged that this assumption on which it based its calculations was wrong and has undertaken a further exercise which has resulted in additional refunds to Suppliers.

45.6 I find that Co-op legal, compliance and audit functions did not have sufficient co-ordinated oversight of Co-op systems to ensure Code compliance. The co-ordinated engagement of these functions with the systems and policies relating to charges happened too late to ensure or to compensate for lack of Code compliance.

Co-op did not have a central repository for storing Supply Agreements and the data available on the portal was inadequate. I understand from a Co-op employee that different trading teams stored this information on separate parts of a drive which led to a situation where contractual information was “all over the place.” I have seen an internal email in which a buyer confirmed that they could not access a Supplier’s contract because they were not the buyer at the time the terms were agreed. Individual buyers’ records were not reliable because they moved categories so often and many had left the business. This was particularly problematic because some Suppliers have more than one contract with Co-op, relating to specific products. This situation contributed to delay in Co-op identifying and compensating Suppliers who were affected by the charges. In some cases the audit team was unable to locate Supply Agreements for particular Suppliers in order to decipher whether refunds were due. I have not seen evidence that the Co-op legal, compliance and audit functions were aware before this exercise of the degree of disorganisation in Co-op systems.

46. Internal systems and processes working to support Code compliance

46.1 I find that one of the root causes of the failure to give Suppliers reasonable notice of the application of depot quality control and benchmarking charges was that Co-op unreasonably relied on its portal as the principal or only way of communicating with Suppliers about variation to Supply Agreements.

Before launching my investigation I had advised Co-op to consider what visibility the information about charges would have on the portal in light of all the other information that the portal contains. I also engaged with all of the Retailers before the investigation specifically looking at the cost to Suppliers and efficiency of their portals. I noted that it was unclear to me whether unilateral variation of terms that are hosted only on the portal constituted reasonable notice.

46.2 Co-op informed me that the primary method it used to communicate with Suppliers about changes to its terms and conditions was updating documents contained on the portal. Internal Co-op correspondence stated that “the supplier portal has a process flow which sends a[n] e-mail notification to the supplier when new terms are uploaded, This gives the supplier a prompt to go into the portal an[d] accept or challenge the uploaded Terms”. Co-op has informed me that it notified Suppliers about changes to benchmarking and depot quality control charges by updating the Charges Matrix. I also learned that Co-op communicated with Suppliers of own-label products through an additional system called MyCore, which is a “data and communication system which is Co-op’s main method of holding specifications and policies for own brands and acts as a communication point for contact with own label suppliers.”

46.3 Co-op informed me that it used its portal to notify Suppliers of the introduction of benchmarking charges of £150 for internal testing and £600 for external testing per product 12 weeks before launch in September 2015, and again used the portal in March 2017 to notify Suppliers of a change in provider of the testing and a reduction of the cost to £500 per external test. Co-op also used the portal to inform Suppliers about the removal of a £200 cap on the maximum depot quality control charge per delivery in July 2015. Although some Suppliers indicated that they received alerts about changes made to terms on the portal, I received evidence from many Suppliers that they did not receive notifications and were unaware that the Charges Matrix could be found on the portal let alone that changes had been made to it that changed their terms and conditions. I also received evidence that:

- the portal was “not fit for purpose”, with many Suppliers reporting problems logging on and Co-op employees describing the portal as slow and inadequate;

- Suppliers were unable to open the Charges Matrix document through the portal; and

- the portal was only routinely accessed by junior employees of Suppliers and that the people responsible for negotiating commercial terms would not have access to or habitually log on to the portal.

46.4 Furthermore, the material I have seen suggests that Co-op assumed that any supplier accepted the terms and conditions of supply to Co-op if it entered and used the portal. One Supplier considered that reliance on the portal was an attempt to “trick” Suppliers into accepting the costs of the charges. I took into account the reports I received of how the portal was used by Suppliers and the difficulty in finding information about charges.

I find that Co-op was not entitled to assume that Suppliers who continued to use its portal were on notice of any change to charges.

46.5 Another internal process that I identified as unhelpful to Co-op in seeking to manage its compliance with the Code was the absence of dates on documentation. One version of the Customer Benchmarking manual I have seen did not include a charging structure and was not dated so it was not possible to ascertain the period for which it was effective. This meant that it was not possible for employees and Suppliers to know whether they were referring to current material.