Gender pay gap employer understanding and actions 2019

Published 22 December 2020

Employers’ Understanding of the Gender Pay Gap and Actions to Tackle it

Research Report on the 2019 Survey

James Murray, Paul Rieger and Hannah Gorry – OMB Research

January 2020

Note: Most of the figures in this report have been converted into data tables. This is to make them accessible to as many people as possible, including people using screen readers and other assistive technologies. We have kept the original figure titles as they are often referred to elsewhere in the report.

1. Executive summary

1.1 Introduction

The government has introduced gender pay gap (GPG) transparency regulations[footnote 1] which are designed to encourage large employers to take informed action to close their GPG where one exists. These regulations came into force in April 2017 and affect around 10,000 employers across the private, voluntary and public sectors.

This report provides results from the 2019 research which was conducted shortly after the deadline for employers to publish their second set of GPG data. The survey covered large employers’ understanding of the GPG, their experiences of complying with the regulations, and the actions they were taking to close their GPG (or ensure one did not develop). It followed on from previous surveys in 2017 and 2018. Where available, comparative results have been provided from these earlier surveys to track any changes over time.

This research consisted of a telephone survey of 900 large employers (with 250 or more staff), and 32 follow-up qualitative interviews to explore the key issues in more detail. It took place between June and September 2019.

1.2 Understanding of the GPG

Understanding of the GPG has continued to rise. Overall, 89% of respondents (typically senior HR staff) felt they had a good understanding of what the GPG is and how it is calculated, up from 82% in 2018 and 48% in 2017 (when the survey was conducted shortly before large employers had to report their GPG data for the first time). Most of the remainder described themselves as having a reasonable understanding but were not sure of the specifics.

In most cases respondents were reasonably confident that this knowledge extended to the top levels of their organisation. Over a quarter (28%) believed their board/leadership team had a very good understanding of the GPG and approaching two-thirds (63%) felt they had a fairly good understanding. Again, this has improved over time, particularly since the 2017 baseline survey when just 71% judged their leadership team to have a very or fairly good understanding of the issue (compared to 91% currently).

1.3 Experiences of the regulations

Most of the surveyed employers (88%) chose to publish their 2018 GPG data on the official government portal in March 2019 (in the month before the deadline). Two-thirds of this group (69%) stated that they had always intended to publish their results relatively late on, compared with 28% who planned to publish earlier but had been delayed.

Among those who always intended to publish in March or later, the primary reason was simply that they had worked towards the statutory deadline as there was no requirement to publish earlier (mentioned by 49% of this group). Others had intentionally aimed for March publication to allow time to gather, analyse and check the data (21%). A significant proportion gave more strategic reasons such as fitting in with other business priorities (20%) or integrating the reporting into their wider business cycle (10%).

Among those who had hoped to publish earlier, the most common causes of delays included staffing/resource issues (25%) and the emergence of more urgent business priorities (20%). Others explained that it took longer than expected to complete the associated tasks, such as gathering the data (15%), running the analysis (18%) or obtaining internal sign-off (19%).

The vast majority (89%) obtained internal sign-off from their leadership team prior to publishing and over half (58%) had also used the GPG viewing service to review results from other organisations. However, in each case this represents a fall from the levels seen in the 2018 survey. The qualitative interviews suggested that some employers are less concerned now that the reporting process has become more established and/or they are more familiar with the likely level of their GPG.

When asked to rate the overall ease of complying with the GPG reporting regulations, over half of respondents (56%) judged it to be very or fairly straightforward. Only 15% found the process difficult, with the remainder describing it as neither difficult nor straightforward (28%). In terms of the individual tasks involved, the greatest challenge was felt to be gathering the necessary data, with only 53% finding this straightforward and 20% experiencing difficulties. In comparison, 88% found it straightforward to submit their results on the portal, 70% to understand what they were required to do and 61% to calculate their results.

The survey provided strong evidence that employers found the compliance process easier second time around. The proportion judging the overall process to have been straightforward increased from 35% in the 2018 survey (conducted shortly after the deadline for the first year of GPG reporting) to 56% in the 2019 survey. There were similar increases for all of the individual aspects of the GPG requirement (understanding what they had to do, gathering the data, calculating their results, submitting their results).

A third of respondents (31%) offered specific suggestions for how GEO could make the reporting process easier or quicker in the future. These most commonly related to either improving the clarity of the existing guidance (11%) or providing more information on how to deal with specific circumstances such as bonuses, non-standard working arrangements or salary sacrifice (8%).

1.4 GPG engagement and communication

As seen in the 2018 survey, most respondents believed that the requirement to measure and report their GPG data had resulted in a greater engagement with the issue at senior-level within their organisation over the last year. Around two-thirds agreed that it had increased awareness of gender pay issues at board level (70%) and prompted board-level discussion or conversation about their GPG (63%). Approaching half (47%) also reported that this had resulted in the board taking action to address their GPG in the last year. However, actions were not always driven by the board. Some employers had taken steps to address their GPG without these actions being instigated by their senior leadership team.

The larger the employer the more likely they were to report each of these impacts, and they were also more prevalent within public/voluntary sector organisations and among those with a higher GPG.

Furthermore, the majority (57%) believed that the GPG reporting had provided a platform for increased focus on wider equality and diversity within their organisation. The qualitative interviews explored this further. In most cases they identified an indirect impact of the regulations, whereby employers’ recognition of equality and diversity as an increasingly important and relevant topic had been heightened by the publicity surrounding the reporting of the GPG results. However, a minority described a more direct influence, where the need to report a GPG figure and subsequently consider ways of reducing had led to board-level consideration of their wider equality and diversity practices/policies.

While senior-level engagement with the GPG was common, most organisations reported that there had been little response to their latest GPG results among their employees (consistent with the results seen in the 2018 survey). Overall 81% said there had been little or no staff reaction, 16% indicated there had been some (but not widespread) attention paid to their results and only 2% reported widespread reaction. Even among those with a high GPG of over 20% just 3% reported widespread staff reaction.

This may be linked to employers typically doing little to communicate their results to staff. Just 15% had adopted a comprehensive and active staff engagement strategy, 52% had drawn their attention to it but nothing further, and 31% had done no promotion at all. However, the likelihood of adopting a comprehensive staff engagement strategy increased with the size of the employer’s GPG, rising to 25% among those with a GPG in excess of 20%.

1.5 Reducing the GPG

Priority

Employer attitudes to reducing the GPG varied widely, with 23% allocating it a high priority, 38% a medium priority and 35% a low or non-priority. There has been little change in this regard since the regulations came into force, with the current results almost identical to those seen in the 2017 baseline survey.

The larger an employer’s GPG, the more likely they were to treat it as a high or medium priority (ranging from 66% of those with a GPG in excess of 20%, down to 47% of those with a GPG of up to 5%). However, those organisations that did not have a GPG at all were also most likely to allocate a high or medium priority to maintaining this situation (66%).

Within the qualitative sample, the introduction of the regulations was generally said to have increased the priority afforded to closing the GPG (and in most cases employers had not measured or seriously considered their GPG before this). However, most reported little or no change in priority in the period since the regulations came into force, either because the underlying factors affecting this had not changed or because the initial plans they had put in place around reducing their GPG were long-term in nature and therefore required a consistent level of commitment. A minority indicated that priority had increased as a result of seeing their GPG widen and/or finding out that it was higher than expected. Conversely, a small number reported that engagement had dipped following an initial ‘spike’ of interest when the regulations were first introduced (although this had not led to a reduction in the importance placed on equality and diversity more widely).

Those treating their GPG as a high priority were typically driven by a desire to do the right thing and be fair/non-discriminatory (64%). Around a quarter (23%) felt that diversity was good for their business (in terms of profitability, productivity, staff engagement) and the same proportion (23%) highlighted the potential impact on their reputation as a motivating factor.

Employers who saw their GPG as a medium priority gave a wide range of reasons, covering both motivations and barriers. The most common positive driver was that addressing their GPG was felt to be the right thing to do (22%), and 15% also explained that it was not a greater priority because they either did not have a GPG or only had a small GPG. However, a quarter (26%) believed there was little or nothing they could do (for example, due to the nature of their sector or a lack of female applicants), 15% referenced other more important priorities and 13% highlighted that the GPG was a long-term issue that would take time to solve.

Among those who viewed their GPG as a low or non-priority, the most common reason was that they believed there was little or nothing they could to about it (40%). Most of the remainder had little desire to address their GPG. 17% indicated that decisions on who to employ and how much to pay were based on ability not gender, 17% referenced more important priorities, and 10% did not see the GPG as important or relevant. However, a quarter (25%) believed did not need to prioritise it because they did not have a GPG or only had a small GPG.

Most employers interviewed in the qualitative phase were not able to easily identify anything which might spur them to increase the priority placed on addressing their GPG. This was typically because they felt they were already doing enough in this area or because they attributed their GPG to wider societal or cultural issues which they saw as outside their control. Some felt that it was more important for the government to take action at a broader level to address the underlying causes of the GPG, rather than attempting to encourage or facilitate individual employers to do more. However, a minority felt that providing information which demonstrated the commercial benefits of reducing the GPG could increase engagement among their senior management.

Diagnosis

Three-quarters (76%) of employers that had a GPG had tried to identify or diagnose the underlying causes of this. This proportion increased with employer size, ranging from 70% of those with 250 to 499 staff to 86% of those with 1,000 or more staff. These results were consistent with those seen in the 2018 survey.

The qualitative interviews found that, irrespective of whether they had undertaken any formal diagnosis, employers generally felt that they understood the causes of their GPG (although the depth of understanding varied). In some cases, this had deterred them from carrying out any diagnosis. While some employers were motivated to investigate the causes of their GPG in order to understand and help address any potentially unfair practices, others were instead driven by a desire to explain/justify their GPG figure and avoid reputational damage.

Employers typically adopted a range of approaches to diagnosis. The most common involved examining the gender balance in their organisation in different areas (91%) and how salaries and bonuses differed by gender within broadly comparable roles (87%). The majority had also looked at the number of part time workers by grade/occupation (76%) and their application, recruitment and promotion rates by gender (66%).

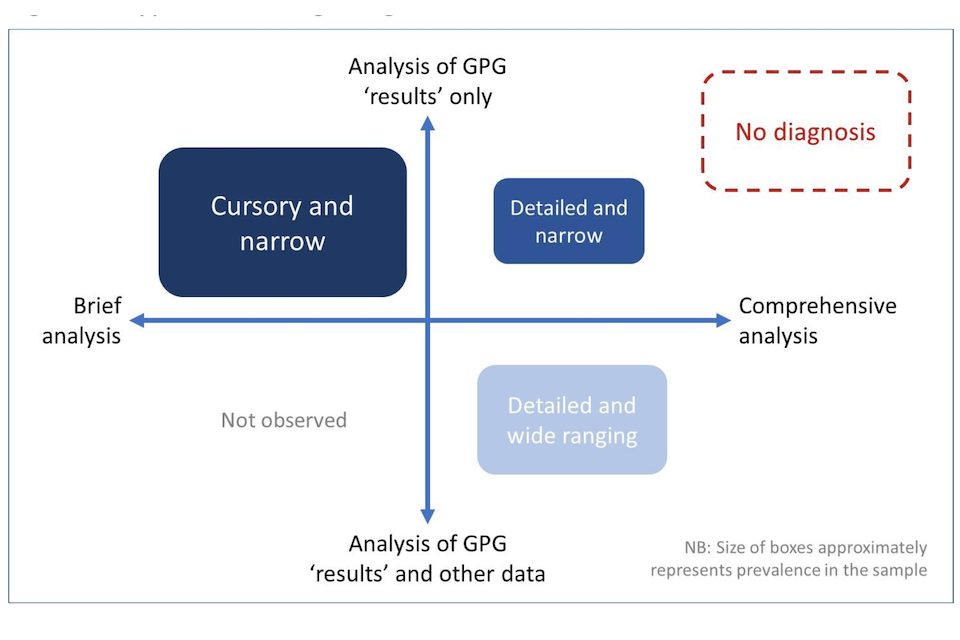

However, the qualitative findings show that most employers had adopted a relatively cursory and narrow approach to diagnosis, with analysis limited to their GPG data rather than incorporating other complementary data sources. Furthermore, employers rarely reported a direct link between this diagnosis and the development of specific, dedicated actions to close their GPG. Rather they felt that by diagnosing the causes of their GPG, they were able to reassure themselves that they were not inadvertently treating women unfairly and, in some cases, confirm that their existing actions to address it were appropriate.

Most employers in the qualitative sample felt that it had been relatively straightforward to both undertake the diagnosis and interpret the resulting data. However, this was to some extent a reflection of the cursory nature of this activity. The ease of the process also differed depending on the size/complexity of their workforce, the functionality/range of their internal systems, and the availability of experienced/qualified staff.

While most surveyed employers had attempted to diagnose the causes of their GPG, only a quarter (26%) had referred to the GEO guidance on this topic. Furthermore, the qualitative interviews found that the guidance was generally regarded as too general, lacking concrete examples or clear direction, and not providing anything new.

Complementary information

The vast majority (88%) of employers had produced some form of complementary information about their GPG, in addition to simply publishing the data required by the regulations. In most cases this included an explanation of the reasons for their GPG (73%). Around half had produced details of how their GPG had changed over time (53%), information on their wider diversity activity (51%), more detailed analysis of their GPG data (46%) and information on the legal requirements and the difference between GPG and equal pay law (46%).

In addition to contextual information, half of employers (50%) had produced details of the actions they had developed or implemented to address their GPG. This proportion increased among larger organisations (ranging from 39% of those with 250 to 499 staff to 63% of those with 1,000 or more staff) and public/voluntary sector employers (62% compared with 46% for the private sector).

Employers who had a GPG were significantly more likely to have produced complementary information on the topic, and there was generally a correlation between this and the size of their GPG. This pattern was particularly evident when it came to actions to address their GPG. 68% of those with a high GPG of over 20% had developed any actions compared to 28% of those with a zero or negative GPG.

The qualitative interviews uncovered a range of reasons for not developing GPG actions. In some cases, this was simply because they did not have a GPG or felt it was small enough not to be a concern. Others did not think there was anything they could do to reduce their GPG, highlighted more important business priorities or had insufficient resources to do so. A minority expressed reservations about the GPG measure itself and did not feel that it accurately reflected their approach to equality and diversity.

In most cases where employers produced complementary GPG information this was made available to the wider public. Three-quarters (73%) of all surveyed employers had externally published at least some additional information. More specifically, a third (35%) had published details of the actions they had developed to address their GPG.

Among those who had developed any GPG actions, 50% had published the same (or more) detail as in their internal plans/documents, 19% had published less detail (a summary or abbreviated version) and 29% had not published these externally at all.

Actions

Many of the GPG actions taken by employers focussed on staff working practices, with 44% offering or promoting flexible working (for example, part time, home working, job sharing) and 36% promoting shared parental leave policies. Others concentrated on the organisation’s HR practices, such as reviewing their existing policies (40%) and improving or altering their recruitment (37%) or promotion (27%) processes. Training also featured heavily, with 30% introducing or continuing mandatory unconscious bias training and 37% introducing or improving other equality and diversity training.

The qualitative interviews found that these actions were usually not developed specifically or exclusively to address their GPG. Rather, most employers described actions which they had implemented to provide a fair and equitable working environment. These actions had often been introduced prior to the GPG regulations, but many employers had subsequently refined and amended them in light of their GPG results. However, there were also cases where employers had introduced new, specific actions as a direct result of the increased focus on the GPG.

A variety of approaches were reported in the qualitative interviews when it came to developing GPG actions. In most cases, a relatively informal process was described with actions developed over a period of time through discussion between senior management and HR. Although less common, some employers (usually larger and/or public sector) had adopted a more considered, staged approach, sometimes directly based on detailed analysis and diagnosis of their GPG.

The degree to which actions to tackle the GPG had been reviewed and amended since employers had first measured their GPG varied. Most employers in the qualitative sample felt that tackling the GPG was a long-term goal, requiring long-term policies, and they did not consider it necessary to formally review or change these policies regularly. Instead, they explained that the actions they had in place would be amended as and when necessary.

The vast majority of surveyed employers who had developed GPG actions had allocated overall accountability for ensuring these happened to a member of the senior management team (89%). They were somewhat less likely to have tasked a specific individual/team with implementing each one (72%) and less than half had incorporated specific timescales for when each action must be implemented (46%). Three-quarters (75%) had a process to formally review the relevance of the actions and assess whether further actions were required, but formal processes to evaluate their impact on the organisation’s GPG were less widespread (58%).

Almost a quarter of employers (23%) had referred to the GEO guidance on producing an action plan, rising to 34% of those who had already developed any actions to address their GPG. The qualitative interviews found that most employers instead referred to the GPG reports, commentaries and action plans produced by other organisations, which provided them with specific examples of relevant actions.

Among those in the qualitative sample who had seen it, the GEO guidance was often described as clear and well laid out. However, perceptions were typically negative when it came to the content, with most finding it too general and lacking specific details about concrete actions they could take.

Expectations

Approaching half (44%) of employers believed their median GPG would improve over the next 5 years, although few expected a significant improvement (4%). Just 3% anticipated that it would get worse. Expectations were more positive when focussing on the longer-term outlook. 54% expected their GPG to improve over the next 10 years, with 15% predicting significant improvement.

The higher the employer’s current GPG, the more positive they were that this would narrow in future. Among those with a high GPG (greater than 20%), 62% expected it to improve over the next 5 years, and 71% over the next 10 years. Those who had developed actions to address their GPG were also more likely to anticipate that it would improve (58% over the next 5 years and 72% over the next 10 years).

The qualitative interviews found a strong consensus that reducing the GPG is a long-term project for both individual employers and the UK as a whole. Many employers felt that they were not in full control of whether their GPG would close, due to the wide range of contributory factors.

When asked what would help them close their GPG, few employers in the qualitative sample suggested (further) government guidance or advice. Instead, many felt that the government should focus its resources on addressing the underlying, societal issues which contribute to the GPG.

1.6 Future GPG measurement and reporting

The survey results indicate that many employers will continue to work towards the regulatory deadline rather than choosing to publish earlier. The majority of employers (73%) did not plan to publish their next set of GPG data until the final quarter of the reporting period (January 2020 or later). More specifically, a third (32%) only intended to publish in the week before the deadline (late March 2020).

When asked their views on the metrics that they were required to report, the large majority felt that the proportion of women in each pay quartile was very or fairly useful (84%). Over two-thirds (69%) found the differences in mean/median hourly rate useful but there was less consensus on the metrics relating to bonuses. 57% felt the proportion paid bonuses was useful and 50% found the differences in mean/median bonus pay useful. There was little change from the 2018 survey in this regard.

1.7 Conclusions

Compliance with the GPG regulations has become easier and less burdensome as employers are now more familiar with the requirements and have established processes in place. The impact of the regulations on understanding of the GPG has also continued, and almost all of those responsible for their organisation’s GPG reporting now have good knowledge.

The GPG engagement levels reported in 2018 have been sustained, and the regulations have also contributed to increased engagement with wider equality and diversity issues. However, not all employers are striving to diagnose and address their GPG, with some primarily focussed on explaining and justifying their results. This situation is relatively static, and changes in underlying attitudes are rare.

Half of employers have developed any actions to close their GPG, and there are signs that this has increased over the last year. It should be noted that some employers do not have a GPG and therefore have little need to take action. Among those with a GPG of over 5%, the proportion developing actions rose to 60%. Where actions have been taken, these are often connected to wider priorities around equality and diversity (where addressing the GPG is just one of a number of objectives), and the implementation of dedicated, GPG-specific actions remains uncommon.

Employers typically feel that they are already placing an appropriate level of priority on the GPG (and doing all they can to address it). Many believe that the government should focus on addressing the wider societal and cultural drivers of the GPG rather than encouraging/facilitating employers to do more.

However, there is evidence that not all employers understand what they could or should be doing to address their GPG, so there is still a role for appropriate guidance (which needs to be as specific as possible and include concrete examples of how employers can make a difference).

2. Introduction

This report details the findings from a study carried out by OMB Research, commissioned by the Government Equalities Office (GEO). The research provides evidence on large employers’ understanding of the gender pay gap (GPG), their experiences of complying with the GPG transparency regulations, and the actions they are taking to close their GPG (or ensure that one does not develop).

The research used both quantitative and qualitative methods and was conducted between June and September 2019.

2.1 Background

The government has committed to closing the gender pay gap. The GPG is an overall measure which reflects differences in median[footnote 2] hourly earnings and labour market participation by gender. Currently the overall gender pay gap for all employees is 17.9%, the lowest since records began.[footnote 3]

New regulations introducing mandatory gender pay gap reporting for large employers aim to encourage employers to take informed action to close their GPG where there is one. These regulations came into force in April 2017 and require private and voluntary sector organisations with 250 or more employees to publish GPG statistics every year.[footnote 4] The same requirements have been introduced for public sector organisations in England (and non-devolved authorities operating across England, Scotland and Wales) by amending the Specific Duties regulations made under Section 153 of the Equality Act 2010.

The Government Equalities Office (GEO) commissioned OMB Research to develop a robust research programme to measure large employers’ understanding of the GPG, understand their experiences of complying with the transparency regulations, and identify the actions they are taking to close their GPG (or ensure that one does not develop).

This report provides results from the 2019 survey, which followed on from an initial baseline survey in 2017 and a further survey in 2018.[footnote 5] Comparative results from these previous surveys have been provided where available to identify any changes over time.

The primary aims of the 2019 research were:

- to provide insight on employers’ understanding of the GPG, covering both HR and board-level staff

- to understand employers’ experiences of complying with the regulations, including how and when they published their statistics, how easy or difficult they found the process, and any impact on board-level awareness and actions

- to gather detail on the level of priority employers allocate to reducing their GPG, the extent to which they have attempted to diagnose the causes of their GPG, the actions they are taking (or planning) to address it, and the success of any such actions to date

- to understand the perceived barriers to taking action

The research took place between late June and early September 2019, so around 3 to 4 months after the deadline for employers to publish their 2018 GPG data.

2.2 Methodology

The research consisted of a quantitative survey of large employers, supplemented by qualitative in-depth interviews with a selection of those who participated in the main survey.

Quantitative survey

Telephone interviews were conducted with 900 large employers between 17 June and 6 August 2019, and covered private, voluntary and public sector organisations with 250 or more employees. These interviews lasted an average of 21 minutes and were conducted with HR directors/managers or other senior staff who confirmed they had responsibility for dealing with their organisation’s response to the GPG transparency regulations.

The sample frame consisted of all employers that had reported their 2018 GPG data on the government portal as of the 4 June 2019.[footnote 6] However, this list contained some employers that were out of scope for the research (for example, those with fewer than 250 employees who chose to voluntarily report their GPG results). All such employers were removed, and the final sample therefore consisted solely of organisations that were subject to the GPG transparency regulations.

The portal data identified those employers classified as public sector for the purposes of the GPG legislation. However, all other employers were classified on the portal as private sector, with no separate identification of voluntary sector organisations. The sample was therefore matched against databases of registered charities and social non-profit companies held by the Charity Commission, the Scottish Charity Regulator (OSCR) and the National Council for Voluntary Organisations (NCVO) to identify voluntary sector employers.

Interlocking quotas were set on sector and size band to ensure good coverage of the large employer population. While these quotas were largely representative of the target population, the voluntary and public sectors were over-sampled to allow robust sub-analysis. For example, public sector organisations account for 16% of the in-scope universe but made up 30% of the interviews conducted. This resulted in statistical confidence intervals of ±4.8% for the private sector, ±5.5% for the voluntary sector and ±5.5% for the public sector.[footnote 7] Table 1 sets out the profile of all in-scope employers in the sample frame along with the profile of the achieved interviews.

Table 1: Universe and achieved interviews by sector and size

| Sector | Size | Universe (in-scope): Number | Universe (in-scope):: % | Interviews: Number | Interviews: % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private | 250 to 499 employees | 3,599 | 35% | 185 | 21% |

| Private | 500 to 999 employees | 2,029 | 20% | 104 | 12% |

| Private | 1,000 or more employees | 1,961 | 19% | 101 | 11% |

| Private | Sub-total: Private | 7,589 | 74% | 390 | 43% |

| Voluntary | 250 to 499 employees | 593 | 6% | 139 | 15% |

| Voluntary | 500 to 999 employees | 265 | 3% | 62 | 7% |

| Voluntary | 1,000 or more employees | 182 | 2% | 43 | 5% |

| Voluntary | Sub-total: Voluntary | 1,040 | 10% | 244 | 27% |

| Public | 250 to 499 employees | 590 | 6% | 97 | 11% |

| Public | 500 to 999 employees | 336 | 3% | 55 | 6% |

| Public | 1,000 or more employees | 692 | 7% | 114 | 13% |

| Public | Sub-total: Public | 1,618 | 16% | 266 | 30% |

| Total | 10,247 | 100% | 900 | 100% |

To account for the disproportionate sampling approach and ensure the research results were representative, the final survey data was then weighted back to the true sector and size profile of all large GB employers subject to the regulations (as per the in-scope universe detailed above).

To provide representative coverage of the full range of different private sector employers, additional sub-quotas were set on Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) code for this group.

The sample drawn from the GPG portal did not include telephone numbers, and these were identified and appended via a combination of automated and manual searches. In some cases, several organisations in the sample shared the same contact details (for example, where the GPG results were reported separately for different subsidiaries but the same individual was responsible in each case). The sample was therefore de-duplicated to ensure that each employer/individual only appeared once, to avoid burdening them with multiple research requests.

Qualitative depth interviews

In addition to the main survey, a total of 32 qualitative follow-up interviews were completed between 1 July and 9 September 2019. These in-depth interviews were conducted by telephone and lasted an average of 30 minutes.

The sample consisted of 2 different groups:

- Longitudinal sample: 13 interviews were conducted with employers who were also interviewed in the equivalent qualitative phases of the 2017 and/or 2018 research, allowing a detailed analysis of how their views and plans had developed over time.

- Fresh sample: 19 interviews were conducted with employers who were interviewed in the 2019 quantitative survey.

In each case, these respondents had previously given consent to be contacted for follow-up research on the GPG for GEO.

Interlocking quotas were set on business size and sector, and the achieved interview profile is set out in Table 2.

Table 2: Qualitative interviews by employer sector and size

| Size (employees): 250 to 499 | Size (employees): 500 to 999 | Size (employees): 1,000 or more | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private sector | 8 | 6 | 7 | 21 |

| Voluntary sector | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Public sector | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| Total | 11 | 10 | 11 | 32 |

Further quotas were set based on the size of each employer’s GPG, based on the data reported on the government portal for 2018. These quotas were intentionally skewed towards employers that had a larger GPG (greater than 5%) in order to better understand the actions taken by these organisations. The achieved interviews were distributed as follows:

- Median GPG of 20% or more: 10 interviews

- Median GPG of 6% to 19%: 16 interviews

- Median GPG of less than 6% (including no GPG): 6 interviews

As far as possible within the constraints of the above quotas, the qualitative sample was also structured to provide a good spread of employers by SIC code, level of priority allocated to addressing their GPG, and whether or not they had developed actions to address their GPG.

2.3 Analysis and reporting conventions

This report contains findings from both the quantitative survey and the qualitative follow-up interviews. Where results are based on the qualitative data, this is clearly identified.

Quantitative reporting

Throughout this report, references to ‘all employers’ and the ‘total’ columns in the charts and tables refer only to the employer population sampled for the survey (GB private, public and voluntary sector organisations with 250 or more employees who reported their 2018 GPG data on the government portal).

Unless explicitly noted, all quantitative findings are based on weighted data. Unweighted bases (the number of responses from which the findings are derived) are displayed on tables and charts as appropriate to give an indication of the robustness of results.

The quantitative data presented in this report is from a sample of large employers rather than the total population. This means the results are subject to sampling error. Differences between sub- groups and changes over time are commented on only if they are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level (unless otherwise stated). This means that there is at least a 95% probability that any reported differences are real and not a consequence of sampling error.[footnote 8]

When interpreting the data presented in this report, please note that results may not sum to 100% due to rounding and/or respondents being able to select more than one answer to a question.

Where relevant, this report contains analysis of the survey results by the size of employers’ median GPG. This analysis is based on the 2018 figures published by each organisation on the government portal (which were confirmed during the survey).

Qualitative reporting

The qualitative phase of the research was based on interviews with a small sample of employers (32 interviews). Although the weight of opinion has sometimes been provided for clarity and transparency, these findings should be treated as indicative and cannot necessarily be extrapolated to the wider population.

Direct quotations have been provided as illustrative examples. However, in some cases these have been abbreviated and/or paraphrased for the sake of brevity and comprehension (without altering the original sense of the quote).

3. Understanding of the GPG

This chapter explores employers’ awareness and understanding of the gender pay gap. More specifically, it covers understanding of:

- what the GPG refers to and how it’s calculated

- the difference between closing the GPG and ensuring equal pay between men and women

3.1 Respondent understanding of the GPG

Overall, 89% of respondents felt they had a good understanding of what the GPG is and how it is calculated (Figure 1). Most of the remainder (10%) believed they had a reasonable understanding.[footnote 9]

Figure 1: Self-reported understanding of the GPG

| Limited understanding of what it refers to | Reasonable understanding but not how it’s calculated | Good understanding of what it is and how it is calculated | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 0% | 10% | 89% |

| Private sector | 0% | 10% | 90% |

| Public and voluntary sector | 0% | 12% | 88% |

| 250 to 499 employees | 0% | 12% | 88% |

| 500 to 999 employees | 1% | 11% | 88% |

| 1,000 or more employees | 0% | 7% | 93% |

Base: all respondents (Base, Don’t know). Total (900, 0%). Private (390, 0%), public and voluntary (510, 0%). 250 to 499 employees (421, 0%), 500 to 999 (221, 0%), 1,000 or more (258, 0%)

There were no statistically significant differences by sector, but respondents from larger employers of 1,000 or more staff were more likely to have a good understanding of the GPG (93% compared with 88% of respondents from organisations with fewer than 1,000 staff).

Figure 2 shows that understanding of the GPG has continued to improve. The proportion with a good understanding increased from 48% in 2017 to 82% in 2018 and 89% in 2019. The greatest increase was seen between the 2017 survey (conducted after the transparency regulations came into force but before the deadline for employers to publish their first set of GPG data) and the 2018 survey (conducted shortly after the deadline for reporting their first year of GPG data). This pattern was evident across all sectors and employer sizes.

Figure 2: Proportion reporting a good understanding of the GPG (over time)

| 2017 survey | 2018 survey | 2019 survey | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 48% | 82% | 89% |

| Private sector | 47% | 81% | 90% |

| Public and voluntary sector | 53% | 85% | 88% |

| 250 to 499 employees | 43% | 80% | 88% |

| 500 to 999 employees | 47% | 83% | 88% |

| 1,000 or more employees | 60% | 85% | 93% |

Base: all respondents (2017, 2018, 2019). Total (900, 900, 900). Private (406, 391, 390), public and voluntary (494, 509, 510). 250 to 499 employees (412, 391, 421), 500 to 999 (214, 236, 221), 1,000 or more (274, 273, 258)

Findings from the qualitative interviews support the survey evidence of increased understanding of the GPG. Some respondents explained that the process of calculating and reporting their data had led to greater engagement with, and clarity about, the topic.

“In the early days we would have confused GPG with equal pay. Before the reporting, it was not often talked about.” (1,000 or more, Voluntary Sector)

3.2 Difference between GPG and equal pay

The above data refers to respondents’ own perceptions of their understanding. To explore their knowledge in more detail, they were provided with 3 different scenarios and asked to indicate whether each one referred to a breach of equal pay law, a GPG issue (but not a breach of equal pay law) or neither. The scenarios were as follows:

-

A company where there is a difference in the average annual pay of men and women just because more women work part time.

-

A company where there is a difference in the average hourly pay of men and women because women work in less senior roles.

-

A company where men and women are paid a different hourly rate for doing the same job.

As set out in Figure 3 below, 89% of respondents correctly identified that scenario 3 referred to a breach of equal pay law and 81% correctly identified that scenario 2 referred to a GPG issue. This suggests that most of those responsible for their organisation’s GPG reporting have a clear understanding of what constitutes a breach of equal pay law and what constitutes a GPG issue.

However, there was less consensus on scenario 1 and only 27% of respondents correctly identified that this was neither a breach of equal pay law nor a GPG issue. Most of the remainder (61% of all respondents) believed that this was a GPG issue.

Figure 3: Scenarios to explore understanding of the difference between GPG issues and breaches of equal pay law

| Breach of equal pay law | GPG issue | Neither | Don’t know | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1: A company where there is a difference in the average annual pay of men and women just because more women work part time | 9% | 61% | 27% | 4% |

| Scenario 2: A company where there is a difference in the average hourly pay of men and women because women work in less senior roles | 5% | 81% | 11% | 3% |

| Scenario 3: A company where men and women are paid a different hourly rate for doing the same job | 89% | 9% | 1% | 1% |

Base: all respondents (900)

In comparison to the 2018 survey, there was no change in the proportion of respondents selecting the correct answer at scenarios 2 and 3. However, the proportion identifying scenario 1 as neither a breach of equal pay law nor a GPG issue has fallen (from 40% in 2018 to 27% in 2019).

While this might imply that detailed knowledge of the GPG has reduced, there could be other reasons for the comparatively low proportion selecting the correct answer at this scenario. These scenarios were relatively difficult to assess during a telephone interview due to the amount of information needing to be retained and the subtle nuances of each one, and scenario 1 may also be affected by a human nature bias whereby respondents are drawn to select a definitive answer rather than the ‘neither’ option. Furthermore, some respondents may have classified scenario 1 as a GPG issue because they interpreted the higher proportion of women in part time roles as an underlying cause of the GPG (for example, if this limits their potential for promotion/higher pay). Finally, there was also a minor wording change to scenario 1 in 2019 (changing ‘more women work fewer hours’ to ‘more women work part time’) which could have contributed to the fall in the proportion selecting the correct response.

Respondents from public and voluntary sector organisations were slightly more likely than their private sector counterparts to know that scenario 2 was a GPG issue (85% compared with 80%) and scenario 3 was a breach of equal pay law (94% compared with 87%). In contrast, private sector respondents were most likely to correctly identify that scenario 1 was neither a breach of equal pay law nor a GPG issue (29% compared with 18% of those from the public or voluntary sectors).

Respondents were also asked to assess their leadership team or board’s understanding of the gender pay gap and the difference between this and equal pay (Figure 4). Over a quarter (28%) felt that this group had a very good understanding, with two-thirds (63%) describing it as fairly good.

Figure 4: Leadership team’s perceived understanding of the GPG and the difference from equal pay

| Very poor understanding | Fairly poor understanding | Fairly good understanding | Very good understanding | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1% | 8% | 63% | 28% |

| Private sector | 1% | 8% | 64% | 26% |

| Public and voluntary sector | 1% | 5% | 60% | 33% |

| 250 to 499 employees | 1% | 8% | 67% | 23% |

| 500 to 999 employees | 2% | 10% | 56% | 32% |

| 1,000 or more employees | 1% | 4% | 62% | 32% |

Base: all respondents (Base, Don’t know). Total (900, 1%). Private (390, 0%), public and voluntary (510, 2%). 250 to 499 employees (421, 1%), 500 to 999 (221, 0%), 1,000 or more (258, 1%)

The proportion judging their leadership team to have either a very or fairly good understanding of the GPG and how it differs from equal pay was broadly similar across the different sectors and employer sizes (ranging from 88% to 94%). However, respondents from private sector employers and organisations with 250 to 499 staff were comparatively less likely to describe their leadership team as having very good understanding (26% and 23% respectively).

The previous survey data suggested that knowledge of the GPG at senior-level had risen since large employers were required to measure and report their data, with the proportion reporting a very or fairly good understanding increasing from 71% in 2017 to 87% in 2018. As shown in Table 3, perceived understanding has risen again in 2019, but to a lesser extent (up to 91%). This increase over the last year was evident in the private sector (from 85% to 90%) but there was no change among public/voluntary sector employers.

Table 3: Leadership team’s perceived understanding of the GPG and the difference from equal pay (over time)

| Year | Total | Sector: Private | Sector: Public and voluntary | Size: 250 to 499 | Size: 500 to 999 | Size: 1,000 or more | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very or fairly good understanding | 2017 | 71% | 70% | 74% | 68% | 72% | 77% |

| Very or fairly good understanding | 2018 | 87% | 85% | 93% | 86% | 87% | 91% |

| Very or fairly good understanding | 2019 | 91% | 90% | 93% | 90% | 88% | 94% |

Base: All respondents (2017/2018/2019). Total (900/900/900), Private (406/391/390), Public and voluntary (494/509/510), 250 to 499 (412/391/421), 500 to 999 (214/236/221), 1,000 or more (274/273/258)

The qualitative interviews provide additional insight into understanding of the GPG among employers’ leadership teams. Some respondents reported that this was not consistent across their senior staff, with big differences in overall levels of engagement and understanding among different members of their leadership team. In particular, less engaged leaders (those placing a lower priority on closing the GPG) were often also felt to be less clear about the difference between the GPG and equal pay.

“There isn’t an appetite to address the issue…Some directors don’t really understand what GPG is. They see that there isn’t a problem with equal pay, so don’t see why GPG should be any different.” (500 to 999, Private sector)

4. Experiences of the regulations

This chapter looks at employers’ experiences of the second year of the GPG regulations. Specifically, it covers:

- how employers reported their GPG data

- when employers published their results and the reasons for this

- the ease of complying with regulations

- views on how the process could be made easier or quicker in future

For all the survey questions reported in this chapter, employers were asked to focus on their experiences of reporting their 2018 GPG results (Year 2 of the regulations). Where available, comparative results have been provided from the previous annual survey, which focussed on employers’ experiences of reporting their 2017 results (Year 1 of the regulations).

4.1 Reporting of GPG data

As shown in Figure 5, most surveyed employers (91%) published one set of GPG data for their entire organisation.[footnote 10]

Figure 5: Whether GPG results were published separately for different subsidiaries

| Separate GPG data for different subsidiaries | One set of GPG data for whole organisation | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 8% | 91% |

| Private sector | 9% | 89% |

| Public and voluntary sector | 5% | 95% |

| 250 to 499 employees | 5% | 94% |

| 500 to 999 employees | 6% | 93% |

| 1,000 or more employees | 16% | 83% |

Base: all respondents (Base, Don’t know). Total (900, 1%). Private (390, 1%), public and voluntary (510, 1%). 250 to 499 employees (421, 1%), 500 to 999 (221, 0%), 1,000 or more (258, 1%)

Larger employers with 1,000 or more staff were most likely to have published separate data for different subsidiaries (16%).

The vast majority of employers (89%) obtained internal sign-off from their leadership team or board prior to publishing their latest GPG results (Figure 6). However, this represents a fall from the level seen in the 2018 survey (96%).

Figure 6: Proportion getting internal sign-off from their leadership team or board (over time)

| 2018 survey | 2019 survey | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 96% | 89% |

| Private sector | 97% | 88% |

| Public and voluntary sector | 95% | 93% |

| 250 to 499 employees | 96% | 85% |

| 500 to 999 employees | 95% | 92% |

| 1,000 or more employees | 98% | 94% |

Base: all respondents (2018, 2019). Total (900, 900). Private (380, 390), public and voluntary (488, 510). 250 to 499 employees (368, 421), 500 to 999 (233, 221), 1,000 or more (267, 258)

Evidence from the qualitative interviews suggests that the lower proportion obtaining senior sign-off on their results is due to increased familiarity with both the reporting requirements and the size of their GPG.

Some respondents noted that their leadership team had become less interested in their GPG results and how they were calculated after the first year of reporting. They described an initial high level of interest (and in some cases concern) when their first set of results was being calculated.

This was usually due to uncertainty over the level of their GPG and the potential public relations impact of a high GPG. However, this level of engagement had always not been sustained in subsequent years, typically because concerns about the size of their GPG and/or the impact of reporting it had diminished.

“Interest in the figures themselves has certainly reduced. There is much less nervous interest among senior managers.” (1,000 or more, Private sector)

Figure 7 shows that a similar picture was seen when it came to use of the GPG viewing service to review results from other organisations. The proportion of employers doing this fell from 73% in 2018 to 58% in 2019.

Figure 7: Proportion using the GPG viewing service (over time)

| 2018 survey | 2019 survey | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 73% | 58% |

| Private sector | 72% | 56% |

| Public and voluntary sector | 76% | 65% |

| 250 to 499 employees | 71% | 50% |

| 500 to 999 employees | 72% | 60% |

| 1,000 or more employees | 78% | 71% |

Base: all respondents (2018, 2019). Total (900, 900). Private (380, 390), public and voluntary (488, 510). 250 to 499 employees (368, 421), 500 to 999 (233, 221), 1,000 or more (267, 258)

As set out in Table 4, employers who had a GPG were more likely to both obtain sign-off from their leadership team before publication and use the GPG viewing service.

Table 4: Internal sign-off and use of the GPG viewing service (by size of GPG)

| Has a GPG: Yes | Has a GPG: No | Size of GPG: More than 20% | Size of GPG: 11% to 20% | Size of GPG: 6% to 10% | Size of GPG: Less than 6% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Got internal sign-off from leadership team or board | 91% | 83% | 94% | 90% | 88% | 91% |

| Used GPG viewing service | 62% | 47% | 66% | 66% | 52% | 57% |

Base: All respondents. Has GPG (678), has no GPG (222), more than 20% (229), 11% to 20% (209), 6% to 10% (115) less than 6% (125)

4.2 Timing of publication

The deadline for publishing their 2018 GPG data on the portal was 4 April 2019 for private/voluntary sector employers and 30 March 2019 for public sector employers. Among the surveyed employers, 88% did not publish their final GPG data until March 2019 or later (in the month before the deadline or after the deadline).

As detailed in Figure 8, over two-thirds (69%) of the employers who submitted their GPG results in March 2019 or later indicated that they had always planned to publish around that time (rather than something delaying them).[footnote 11]

Figure 8: Reason for not publishing GPG results until March 2019 or later

| Planned to publish earlier but was delayed | Always planned to publish March 2019 onwards | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 28% | 69% |

| Private sector | 27% | 70% |

| Public and voluntary sector | 29% | 67% |

| 250 to 499 employees | 26% | 70% |

| 500 to 999 employees | 28% | 69% |

| 1,000 or more employees | 30% | 67% |

Base: all who published in March 2019 or later (Base, Don’t know or can’t remember). Total (726, 3%). Private (326, 3%), public and voluntary (400, 4%). 250 to 499 employees (336, 4%), 500 to 999 (177, 3%), 1,000 or more (213, 3%)

Those employers that had always planned to publish in March 2019 or later were asked why they had decided not to do so earlier (Table 5). This question was asked unprompted and respondents were able to provide multiple reasons.

Table 5: Reasons for intentionally not publishing GPG results until March 2019 or later

| All who planned to publish in March 2019 or later | |

|---|---|

| Just worked towards deadline or no requirement to do it earlier | 49% |

| To allow time to gather or analyse or check the data | 21% |

| Other more important or competing priorities | 20% |

| To fit in with wider business cycle (for example, annual reporting, all companies in the group reporting together) | 10% |

| To allow time to get internal approval or sign off (for example, from senior management/board) | 9% |

| Wanted to see results from other organisations first | 3% |

| Wanted to avoid negative publicity or media attention | 2% |

| Wanted to see how other organisations reported or explained their results | 2% |

| Staffing issues (for example, understaffed, changes in key personnel) | 2% |

| Due to reliance on external parties (for example, payroll or other service providers) | 2% |

| To allow time to produce supporting documentation | 1% |

| Other reasons | 1% |

| Don’t know | 2% |

Base: All who always planned to publish in March 2019 or later (496)

As shown above, half (49%) of the employers who had always planned to publish in March 2019 or later indicated that they had simply worked towards the statutory deadline as there was no requirement to publish earlier. In addition, significant proportions had intentionally aimed for March publication to allow time for key tasks such as gathering, analysing and checking the data (21%) or obtaining internal sign-off (9%). One-fifth (20%) highlighted other more important or competing priorities, and 10% had decided on March to fit in with their wider business cycle.

Those employers that intended to publish before March 2019 but had been delayed were asked what had caused this (Table 6). Again, this question was asked unprompted and respondents were able to provide multiple reasons.

Table 6: Factors that delayed publication of GPG results until March 2019 or later

| All who intended to publish before March 2019 but were delayed | |

|---|---|

| Staffing/resource issues (for example, key staff leaving or unavailable) | 25% |

| Other more urgent priorities | 20% |

| Time taken to get internal approval or sign off (for example, from senior management/board) | 19% |

| Time taken to run the analysis/calculations | 18% |

| Time taken to gather the data | 15% |

| Time taken by 3rd parties to provide the data or analysis (for example, payroll providers, specialist consultants) | 7% |

| Time taken to produce supporting documentation | 6% |

| System changes or issues (for example, payroll software) | 3% |

| Difficulties registering on the portal (for example, PIN issues) | 2% |

| Identified calculation/data errors | 2% |

| Other factors | 6% |

| Don’t know | 2% |

Base: All who planned to publish before March 2019 but were delayed (206)

A quarter of this group (25%) reported that the delay was down to staffing and resource issues and a fifth (20%) indicated that other more urgent priorities had pushed back their GPG reporting. The other most widespread reasons all related to the amount of (unforeseen) time required to complete the various tasks, such as getting internal sign-off (19%), running the analysis (18%), gathering the data (15%), receiving the data from 3rd parties (7%) or producing their supporting documentation (6%).

A minority of the surveyed employers (7%) had modified and resubmitted their GPG results after they first published them. This group were asked why they had needed to do this (Table 7).

Table 7: Reasons for modifying GPG results after first publishing them

| All who modified their data after publishing | |

|---|---|

| Amended or added supporting documentation or narrative commentary | 33% |

| Identified a calculation error or incorrect data themselves | 25% |

| Amended details about their organisation (for example, size, sector, contact details) | 9% |

| Informed by GEO that there was an issue with their data | 6% |

| Don’t know reason | 19% |

| Did not change results or not aware that changed results | 13% |

Base: All who modified and resubmitted their results (65)

Around a third had resubmitted their results because the data was incorrect, with 25% identifying the error themselves and 6% being informed by GEO. A similar proportion (33%) had simply amended or added supporting documentation (for example, a link to their narrative commentary or GPG report) rather than changing their data.

4.3 Ease of complying

Employers were asked to rate the overall process of complying with the GPG reporting regulations on a 5-point scale, where 1 meant it was very difficult and 5 meant it was very straightforward.

Figure 9 shows that while perceptions varied, over half (56%) described it as very or fairly straightforward. Only 15% found the process difficult, with the remainder judging it to have been neither difficult nor straightforward (28%).

Figure 9: Overall ease of complying with the regulations

| Very difficult | Fairly difficult | Neither difficult nor straightforward | Fairly straightforward | Very straightforward | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 5% | 10% | 28% | 35% | 21% |

| Private sector | 5% | 10% | 29% | 34% | 21% |

| Public and voluntary sector | 3% | 9% | 26% | 40% | 21% |

| 250 to 499 employees | 6% | 10% | 27% | 34% | 22% |

| 500 to 999 employees | 4% | 10% | 29% | 36% | 20% |

| 1,000 or more employees | 3% | 10% | 30% | 36% | 19% |

Base: all respondents (Base, Don’t know). Total (900, 1%). Private (390, 1%), public and voluntary (510, 1%). 250 to 499 employees (421, 1%), 500 to 999 (221, 1%), 1,000 or more (258, 2%)

Public and voluntary sector organisations were slightly more positive about the process, with 61% finding it straightforward (compared with 54% of private sector employers). There was no difference in ease of compliance by employer size.

As shown in Table 8, there is strong evidence that employers found the process easier second time around. The proportion judging it to have been straightforward increased from 35% in the 2018 survey (conducted shortly after the deadline for the first year of GPG reporting) to 56% in the 2019 survey.

Table 8: Overall ease of complying with the regulations (over time)

| Year | Total | Sector: Private | Sector: Public and voluntary | Size: 250 to 499 | Size: 500 to 999 | Size: 1,000 or more | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very or fairly straightforward | 2018 | 35% | 31% | 44% | 33% | 39% | 33% |

| 2019 | 56% | 54% | 61% | 57% | 57% | 54% |

Base: All respondents (2018/2019). Total (868/900), Private (380/390), Public and voluntary (488/510), 250 to 499 (368/421), 500 to 999 (233/221), 1,000 or more (267/258)

Respondents were also asked to rate their experiences of the different tasks involved, using the same 5-point scale (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Ease of completing the different tasks associated with the regulations

| Very difficult | Fairly difficult | Neither difficult nor straightforward | Fairly straightforward | Very straightforward | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Understanding what you were required to do | 4% | 7% | 19% | 36% | 33% |

| Gathering the necessary data | 5% | 14% | 26% | 34% | 20% |

| Calculating your results | 3% | 11% | 22% | 37% | 24% |

| Submitting your results on the portal | 1% | 2% | 4% | 20% | 68% |

Base: all respondents (Base, Don’t know). Total (900, 1%, 2%, 3%, 5%).

As shown above, the vast majority of employers found it easy to submit their results on the portal, with 88% judging this task to be straightforward (and 68% rating it as very straightforward).

While the feedback was generally still positive, reaction was somewhat more divided for the other tasks. 70% found it straightforward to understand what they were required to do, 61% to calculate their results and 53% to gather the necessary data. Of all the tasks, employers were most likely to report issues with gathering the data, with a fifth (20%) describing this as very or fairly difficult.

As with the overall rating for ease of complying with the GPG regulations, the ease of completing each of the key tasks has improved since the 2018 survey (conducted shortly after the Year 1 reporting deadline). Figure 11 shows that this was most apparent for understanding what they were required to do. Less than half (47%) of employers found this straightforward in the 2018 survey, but this rose to 70% in 2019.

Figure 11: Proportion rating each task as very/fairly straightforward (over time)

| 2018 survey | 2019 survey | |

|---|---|---|

| Understanding what you were required to do | 47% | 70% |

| Gathering the necessary data | 41% | 53% |

| Calculating your results | 53% | 61% |

| Submitting your results on the portal | 81% | 88% |

Base: all respondents. 2018 (868), 2019 (900).

As detailed in Table 9 below, in the 2019 survey private sector organisations were less likely than public and voluntary sector ones to have found each task straightforward. There were no consistent differences by employer size.

Table 9: Ease of completing the different tasks associated with the regulations (by sector and size)

| Proportion finding each task very/fairly straightforward | Sector: Private | Sector: Public and voluntary | Size: 250 to 499 | Size: 500 to 999 | Size: 1,000 or more |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Understanding what you were required to do | 68% | 75% | 67% | 73% | 70% |

| Gathering the necessary data | 52% | 57% | 56% | 55% | 48% |

| Calculating your results | 59% | 67% | 64% | 60% | 58% |

| Submitting your results on the portal | 87% | 93% | 88% | 91% | 86% |

Base: All respondents. Private (390), Public and voluntary (510), 250 to 499 (421), 500 to 999 (221), 1,000 or more (258)

Respondents were asked if they had any specific suggestions for how GEO could help make the reporting process significantly easier or quicker in future (Table 10). Approaching a third (31%) made any such suggestions, and these typically related to either the clarity of the existing guidance (11%) or a need for more information on how to deal with specific circumstances such as bonuses, non-standard working arrangements, part time staff or salary sacrifice (8%).

Table 10: Suggestions for how GEO could help make the reporting process easier or quicker

| Total | |

|---|---|

| Easier to understand or clearer guidance | 11% |

| - Simplify the guidance | 5% |

| - Who to include and exclude | 3% |

| - How to calculate the figures | 2% |

| - Other suggestions on clarity of guidance | 2% |

| More guidance on how to deal with specific circumstances | 8% |

| - Bonuses | 2% |

| - Non-standard working arrangements (for example, term-time only) | 1% |

| - Part time workers | 1% |

| - Salary sacrifice | 1% |

| - Other suggestions on specific circumstances | 5% |

| Change the requirements or calculations | 5% |

| Downloadable software or templates to calculate their GPG results | 2% |

| More or clearer communications about the time-scales required | 2% |

| Case studies or examples or benchmarks from other organisations | 1% |

| Better or improved accessibility to the portal (for example, technical improvements, easier access for different individuals) | 1% |

| Dedicated helpline or point of contact | 1% |

| Training or workshops or seminars or webinars | 1% |

| External checks or reviews of calculations | 1% |

| Other suggestions | 4% |

| No suggestions for how GEO could make process easier/quicker | 69% |

Base: All respondents (900)

There were no notable differences by size or sector when it came to the suggestions provided.

5. GPG engagement and communication

This chapter looks at the response to employers’ latest GPG results among their senior leadership and other staff. Specifically, it covers:

- impact of the regulations on board-level awareness and action

- how GPG results were communicated and the reaction among staff

5.1 Impact of GPG regulations on board-level engagement

Most respondents believed that the requirement to measure and report their GPG data had resulted in a greater engagement with the issue at senior-level within their organisation over the last year.

As detailed in Figure 12 below, around two-thirds agreed that it had increased awareness of gender pay issues at board level (70%) and prompted board-level discussion or conversation about their GPG (63%). Approaching half (47%) reported that it had also resulted in the board taking action to address their GPG in the last year (or, if they had no GPG, to ensure that one did not develop).

The 2019 survey also included a new question to assess whether the requirement to measure and report their GPG data had provided an opportunity or platform for increased focus on wider equality and diversity issues within their organisation. Over half (57%) of surveyed employers agreed that this was the case.

Figure 12: Impact of the regulations on board-level engagement with the GPG over the last year

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Agree | Strongly agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased awareness of gender pay issues at board level | 3% | 11% | 16% | 48% | 22% |

| Prompted board level discussion or conversation about your GPG | 3% | 16% | 14% | 44% | 19% |

| Resulted in the board taking action to address your GPG | 5% | 21% | 23% | 39% | 8% |

| Provided an opportunity or platform for increased focus on wider equality and diversity issues | 4% | 17% | 20% | 43% | 15% |

Base: all respondents (Base, Don’t know). Total (900, 1%, 4%, 4%, 1%).

Figure 13 shows that there has been little change in the board-level impacts of the regulations between the first year of reporting (as covered in the 2018 survey) and the second year of reporting (as covered in the 2019 survey).

Figure 13: Proportion agreeing that there was an impact on board-level engagement with the GPG (over time)

| 2018 survey | 2019 survey | |

|---|---|---|

| Increased awareness of gender pay issues at board level | 69% | 70% |

| Prompted board level discussion or conversation about your GPG | 67% | 63% |

| Resulted in the board taking action to address your GPG | 46% | 47% |

| Provided an opportunity or platform for increased focus on wider equality and diversity issues | N/A | 57% |

Base: all respondents. 2018 (868), 2019 (900).

As shown in Table 11, the larger the employer the more likely they were to report each of these impacts on board-level engagement. These impacts were also more prevalent within public and voluntary sector organisations than private sector companies.

Table 11: Impact of the regulations on board-level engagement with the GPG over the last year (by sector and size)

| Proportion agreeing that the regulations have… | Sector: Private | Sector: Public and voluntary | Size: 250 to 499 | Size: 500 to 999 | Size: 1,000 or more |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased awareness at board level | 67% | 77% | 62% | 71% | 82% |

| Prompted board-level discussion or conversation | 59% | 76% | 53% | 69% | 76% |

| Resulted in board taking action | 45% | 51% | 35% | 52% | 62% |

| Provided opportunity or platform for increased focus on wider equality and diversity issues | 53% | 69% | 44% | 62% | 74% |

Base: All respondents. Private (390), Public and voluntary (510), 250 to 499 (421), 500 to 999 (221), 1,000 or more (258)

These impacts were also more widespread among employers that had a GPG, particularly those with a larger GPG (Table 12). For example, 56% of those with a median GPG of over 20% reported that their board had taken action to address this, compared to 40% of those with no GPG (zero or negative).

Table 12: Impact of the regulations on board-level engagement with the GPG over the last year (by size of GPG)

| Proportion agreeing that the regulations have… | Has a GPG: Yes | Has a GPG: No | Size of GPG: More than 20% | Size of GPG: 11% to 20% | Size of GPG: 6% to 10% | Size of GPG: Less than 6% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased awareness at board level | 72% | 63% | 75% | 73% | 72% | 66% |

| Prompted board-level discussion or conversation | 68% | 51% | 75% | 65% | 63% | 64% |

| Resulted in board taking action | 49% | 40% | 56% | 45% | 52% | 43% |

| Provided opportunity or platform for increased focus on wider equality and diversity issues | 61% | 44% | 66% | 58% | 62% | 60% |

Base: All respondents. Has a GPG (678), has no GPG (222), more than 20% (229), 11% to 20% (209), 6% to 10% (115), less than 6% (125)

Qualitative insight

The qualitative interviews provide further insight into the impact of the regulations on board-level engagement with the GPG. Overall, the introduction of the regulations was said to have prompted an increased interest in the GPG as a measure (what it means, how it is calculated) and in employers’ own results. The only employers reporting no impact at all explained that their board- level staff had already been highly engaged with GPG prior to the regulations coming into force.

As found in the 2018 research, the type and nature of conversations and decision making at a board level varied depending on the size of employers’ GPG and the (perceived) causes. While some primarily wanted to understand the underlying reasons for their GPG in order to determine how to reduce it, others were more concerned with explaining their GPG figure and demonstrating that it did not necessarily relate to unfair or unequal employment policies or practices.

“Certainly, the board were keen to know what the cause of the figure was. They were worried about how it would look and they wanted to explain it.” (1,000 or more, Private sector)

Respondents reported differences in exactly how the regulations had resulted in their board taking action to tackle their GPG.

In a minority of cases, action was said to be driven primarily by the senior leaders themselves (usually with one individual in particular seen as a key influencer). However, more commonly, HR directors and managers had used their GPG results as a means of encouraging the board to approve new actions.

“We have done more on GPG since the regulations have come in. It is us [HR] who are driving it, but the board have taken the issues on board much more as there is a number they can look at.” (250 to 499, Private sector)

Furthermore, some respondents explained that the introduction of the GPG regulations had contributed to an increased awareness of, and interest in, diversity and equality issues more widely. This increased focus was driven both directly and indirectly by the regulations:

- In a minority of cases, the need to report a GPG figure and subsequently consider ways of reducing it was said to have led to board-level conversations about the impact of existing practices and policies on different employee groups (not just by gender).

- In most cases, employers’ recognition of equality and diversity as an increasingly important and relevant topic within society as a whole had been heightened by the publicity surrounding the reporting of the GPG results. They explained that they were already prioritising equality and diversity issues, but this had been boosted to some extent by the increased focus on the GPG.

“There has been more focus on diversity and inclusion over the past few years…it was going that way, but yes the GPG reporting has played into that.” (250 to 499, Voluntary Sector)

As referenced previously, the qualitative interviews also suggest some drop-off in senior-level engagement and interest in the GPG results themselves since the first year. However, as discussed in more detail in chapter 6.1, reduced interest and engagement in their annual GPG figures does not always mean reduced interest in taking actions to tackle the GPG itself.

5.2 Communication of GPG results and staff reaction

As detailed in Figure 14, only a minority (15%) of employers had adopted an active engagement strategy to communicate their GPG results to their employees. Half (52%) had drawn their attention to it but nothing further, and a third (31%) had not done any promotion or engagement with staff. This mirrored the results seen in the 2018 survey.

While communication of GPG results to clients, suppliers, investors and other external stakeholders was less common, the proportion that had done any form of promotion or engagement had increased since the 2018 survey (from 36% to 46%).

Figure 14: How latest GPG results were communicated to employees and stakeholders (over time)

| For employees | For clients, suppliers, investors and other stakeholders | |

|---|---|---|

| Adopted a comprehensive and active engagement strategy: 2018 survey | 16% | 5% |

| Adopted a comprehensive and active engagement strategy: 2019 survey | 15% | 7% |

| Drawn their attention to it but nothing further: 2018 survey | 50% | 31% |

| Drawn their attention to it but nothing further: 2019 survey | 52% | 39% |

| Not done any promotion or engagement activity: 2018 survey | 32% | 60% |

| Not done any promotion or engagement activity: 2019 survey | 31% | 51% |

Base: all respondents (Base, don’t know approach for employees, Don’t know approach for stakeholders). 2018 (868, 2%, %), 2019 (900, 2%, 4%).

Private sector organisations were least likely to have communicated results to their staff. 34% had not done any promotion or engagement activity compared with 21% of public and voluntary sector employers. However, the proportion that had adopted a comprehensive and active staff engagement strategy was similar (15% and 16%). A similar pattern was evident when it came to communicating their GPG results to external stakeholders.

Larger organisations with 1,000 or more staff were most likely to have adopted an active engagement strategy. 22% did this with their employees and 11% with external stakeholders (compared with 11% and 4% respectively for organisations with 250 to 499 staff).

Those employers that had a GPG were also more inclined to actively engage with their staff about their results (19% compared with 5% of those with no GPG). This proportion tended to increase in line with the size of their GPG, ranging from 25% of those with a GPG of over 20% down to 13% of those with a GPG of less than 6%.

As shown in Figure 15 below, most organisations (81%) reported that there had been little or no response to their GPG results by their employees, and only 2% reported widespread staff reaction (for example, asking questions, raising concerns). There has been no change since the 2018 survey in this respect.

Figure 15: Employee reaction to latest GPG results (over time)

| 2018 survey | 2019 survey | |

|---|---|---|

| There has been widespread reaction to them | 2% | 2% |

| There has been some attention paid to them but not widespread | 17% | 16% |

| There has been little or no reaction from staff | 81% | 81% |

Base: all respondents (Base, Don’t know). 2018 (868, 1%), 2019 (900, 1%).

The proportion of employers reporting widespread staff reaction to their GPG results was similarly low across all sectors and sizes (1% to 2%). However, large organisations of 1,000 or more employees were comparatively more likely to have experienced at least some staff attention about their results (27% compared with 15% of those with fewer than 1,000 employees).

Table 13 shows that employers with a GPG were more likely to report that their staff paid at least some attention to the results (21% compared with 9% of those with no GPG). This rose to 26% among those with a large GPG of over 20%, although only 3% of this group reported widespread reaction from their employees.

Table 13: Employee reaction to their GPG results (by size of GPG)

| Has a GPG: Yes | Has a GPG: No | Size of GPG: More than 20% | Size of GPG: 11% to 20% | Size of GPG: 6% to 10% | Size of GPG: Less than 6% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Widespread reaction to them | 2% | 1% | 3% | 1% | 3% | 0% |

| Some attention paid but not widespread | 19% | 8% | 23% | 19% | 14% | 18% |

| Little or no reaction from staff | 77% | 91% | 72% | 79% | 80% | 81% |

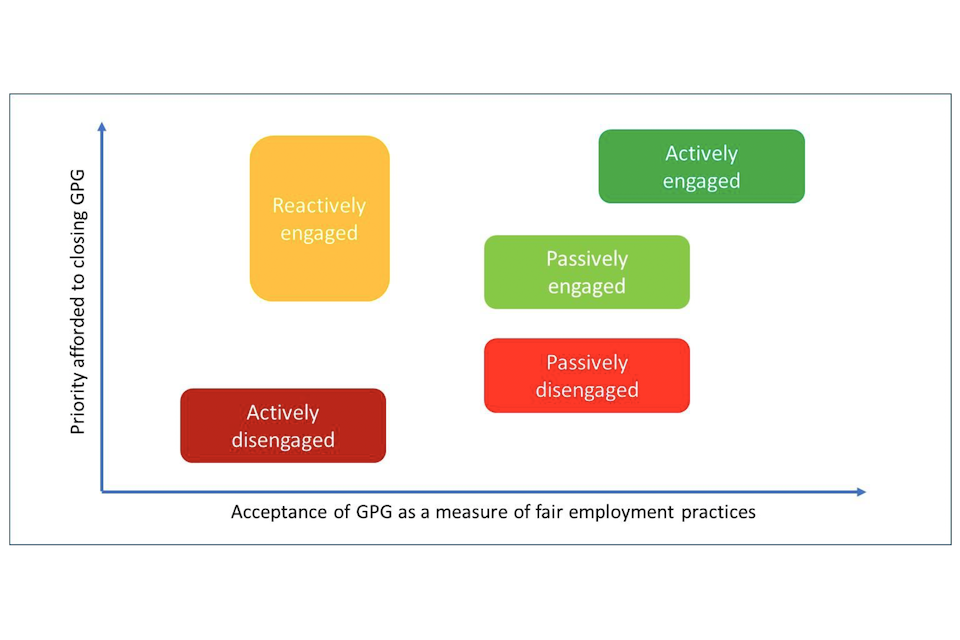

| Don’t know | 1% | 0% | 1% | 1% | 2% | 0% |