Annex - interim GMPP evaluation review (Phase 1) (HTML)

Published 23 April 2025

Executive Summary

This report provides interim results based on the 2022-23 Government Major Projects portfolio. Final results for the 2023-24 portfolio are available in the Government Major Projects Evaluation Review (published April 2025).

Context

The Government Major Projects Portfolio (GMPP) comprises the government’s largest and most complex projects, currently with 244 projects that collectively account for approximately £805 billion in whole life costs. Major Projects are defined as those requiring spending over departmental expenditure limits; requiring primary legislation; which are novel, complex or contentious.[footnote 1] It is, therefore, essential that these projects are evaluated, benefits are measured, and that learning is shared and informs implementation and future decisions.

Evaluation allows lessons to be learned about what works well and what does not, and means that government departments can be held accountable not just for ensuring projects are delivered but also that they are delivering value for money in their Major Projects. This is an essential part of continuous improvement; however, past evidence has shown significant shortcomings in evaluation across government, including the GMPP.[footnote 2]

The Evaluation Task Force (ETF) commissioned Ipsos UK and Ecorys to review the scale and quality of evaluation across the current GMPP, identify the challenges Major Projects experience with their evaluations, and how improvements can best be achieved.

Method

Data on evaluation arrangements was initially collected by the ETF through a questionnaire of all Major Projects on the GMPP. Following this, three stages of analysis were carried out. First, Ipsos UK and Ecorys analysed questionnaire data about the status and nature of evaluation in each Major Project. This was followed by a desk-based review of the evaluation plans and reports shared. Evaluations were categorised as robust if they used suitable experimental, quasi-experimental or theory-based methods which were appropriate and proportionate in the context of the project.[footnote 3] Depth interviews were then conducted with a sample of projects to understand more about what is working well and less well in Major Projects evaluation and why.

- 221 responses to ETF survey of evaluations status and nature

- 104 evaluation plands shared for desk-based review and scoring

- 42 in-depth interviews were conducted with a mix of those who had not shared plans

Findings

The review found that evaluation is not prevalent among Major Projects. Less than half of projects (104/244) shared evaluation plans. Of the 69 Major Projects planning an impact evaluation, 53 were scored as robust (receiving a score of 2). The review, therefore, found that only 22% of all 244 Major Projects reviewed were able to evidence a robust impact evaluation plan during the review period. The projects demonstrating robust impact evaluation plans constitute 41% of the £805 billion whole life costs on the GMPP. Evidence of robust impact evaluation was particularly weak among Military Capability projects and Information and Communication Technology (ICT) projects. Figure 1.1 illustrates the number of Major Projects with robust impact evaluation for the total GMPP.

Figure 1.1: Scale and quality of impact evaluation across the GMPP

| Category | Number of projects | Total cost (£ Billion) |

|---|---|---|

| Total GMPP | 244 | £805 |

| Total with robust evaluation | 53 | £332 |

The review identified several barriers and challenges which are preventing the systematic application of evaluation across the GMPP. These can be broadly grouped as follows:

Operational: Some projects had faced acute challenges with accessing or generating the data they needed to assess impact. In some cases, this was linked to the nature of the project, but in other cases it was because there had been insufficient planning in place to identify the data sources, and to set up the necessary data sharing permissions and/or to collect the data robustly. In many cases, projects reported that there had been insufficient time to design evaluation into the project at an early enough stage, resulting in challenges measuring impact.

Cultural: Some projects reported encountering resistance to evaluation among more senior staff and decision makers, with evaluation being perceived as a “luxury”. As a result, insufficient resources were allocated. In other cases, projects reported a perceived lack of flexibility in designing evaluations - that the types of evaluation questions posed (such as economic outcomes and impacts) were not always relevant to their projects. Some projects felt that they had developed evaluation approaches that worked well for their needs, and called for greater acknowledgement of the flexibility needed in evaluation design.

Resourcing: Some Major Projects reported having insufficient resources (staffing, funding, teams, and systems) dedicated to evaluation. While this review found evidence that this is improving within several departments, there is still some way to go for some projects to have the staff and budgets needed for robust evaluation.

The review also identified areas of progress which demonstrate improvements can be made in evaluation activity for Major Projects when the challenges above are addressed. A higher proportion of infrastructure and construction projects, 30%, were able to evidence robust evaluation plans are in place, which has been driven by a strengthened emphasis on evaluation in departments with more of these types of projects. Central government departments have also published evaluation strategies which provide clear commitments to robust and proportionate evaluation for all projects and programmes, including Major Projects.[footnote 4]

Recommendations

The following recommendations have been identified based on the evidence of the review, for consideration by the Evaluation Task Force, HM Treasury, the Infrastructure and Projects Authority and government departments to consider.

Recommendation 1: Reinforce evaluation requirements, its benefits and the standards set in existing government guidance: Promote the value of evaluating Major Projects across government, to senior leaders and Ministers, as well as those involved in the design, delivery, support and assurance of Major Projects. Demonstrate how evaluation can be built into the design and implementation of projects, facilitating helpful learning and accountability. Ensure there are clear standards and expectations of what constitutes a robust and proportionate evaluation approach to all types of Major Projects, providing clear signposting to guidance, advice and support available. The use of robust evaluation methodologies should be the default approach given the scale and complexity of Major Projects.

Recommendation 2: Embed evaluation into department and HM Treasury approvals and department governance for Major Projects: Ensure that evaluation evidence and plans inform Major Project approval decisions. This should include ensuring that there are sufficient governance arrangements, as well as resources, to develop and deliver good quality evaluations, monitor their progress, and provide appropriate scrutiny and assurance. There should be mechanisms for providing additional support and/or scrutiny of the evaluation and escalation where necessary and for ensuring that evaluation findings are used to inform project improvements and/or future decisions.

Recommendation 3: Develop evaluation capability in Major Project teams and invest in good data infrastructure: Ensure that analysts as well as project delivery staff and benefits leads working on Major Projects have the knowledge and skills required to develop and deliver robust and proportionate evaluations of Major Projects. This includes access to good quality data/data infrastructure, or the means to collect or create it. It also includes capability in applying appropriate evaluation methods - experimental, quasi-experimental and theory-based - suited to the specific context of Major Projects.

1. Introduction

1.2 Background to the GMPP Evaluation Review

In December 2022, the Evaluation Task Force (ETF) commissioned a review of the scale and quality of evaluations within the Government Major Projects Portfolio (GMPP). The GMPP represents the UK Government’s largest, most innovative, and high-risk projects and programmes, and in 2022-23 covered 244 projects that collectively account for approximately £805 billion of government spending.[footnote 5]

This 2023 GMPP Evaluation Review is a follow up to two earlier assessments of the quality of evaluation among Major Projects and Government evaluations in general. A rapid review conducted in 2019 by the Prime Minister’s Implementation Unit (PMIU) found that only 8% of Government’s £432 billion spending on Major Projects had robust impact evaluation plans in place, and 64%, accounting for £276 billion of public money, had no evaluation at all.[footnote 6] In 2021, a National Audit Office (NAO) report concluded that despite initiatives to increase its systematic application in policymaking, evaluation remained variable and inconsistent across Government, with considerable strategic, technical, and political barriers to improvements.[footnote 7]

Drawing on these recommendations, the ETF, in collaboration with Government Departments and other stakeholders have set out to improve the current state of evaluation across the GMPP, by addressing barriers to the use of evaluation.[footnote 8]

The ETF and the review team from Ipsos and Ecorys extend our thanks to all those who engaged in this review, notably from the Cross-Government Evaluation group (CGEG), HMG Departments, and the Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA).

Note that this report provides interim results based on the 2022-23 Government Major Projects portfolio. Final results for the 2023-24 portfolio are available in the Government Major Projects Evaluation Review (published April 2025).

1.3 Purpose and objectives of the GMPP Evaluation Review

The purpose of this review was to generate evidence on whether there has been progress in enhancing evaluation of Major Projects since the 2019 PMIU review. It sought to identify the factors that hinder effective evaluation and propose possible ways to address these challenges in order to drive higher quality and consistent evaluation of Major Projects.

The objectives of the review were threefold:

- To assess the scale and quality of current evaluation plans;

- To identify strengths and improvements for each project; and

- To develop guidance on best practices and tools to help Major Project teams to raise evaluation standards across the GMPP.

This work is part of the ETF’s wider programme which aims to ensure there is robust and proportionate evaluation at the centre of decision-making across government.

This review involved a combination of primary and secondary research as summarised in Figure 1.2 below. More information about the methodology can be found in Annex 1.

Figure 1.2: Stages of the review process

- Stage 1: Descriptive analysis of responses to an ETF survey sent to all Major Projects of the evaluation arrangements in place. 221 out of a total of 244 projects provided a return.

- Stage 2: Assessment of the quality of evaluation plans in place for 104 projects that shared suitable documentation with the review team and thematic analysis of 42 semi-structured interviews carried out with Major Project and evaluation teams.

- Stage 3: Data from all research strands (returns, desk-based review, and the depth interviews) was collated and synthesised, as well as being triangulated with evidence from IPA Annual Report on Major Projects.

1.4 Defining and assessing evaluation quality

To assess the quality of evaluation plans shared by Major Project teams, Ipsos designed a bespoke Quality Assessment Tool (QAT) (see Annex 2). This QAT assessed evaluation plans against three criteria:

- Clarity, cohesiveness and logic of the evaluation aims objectives and research questions;

- Appropriateness, robustness/quality, and proportionality of the evaluation methods proposed;

- Sufficiency and appropriateness of resources and management dedicated to the evaluation.

Within each of these three broad criteria, evaluation plans were given scores on a scale of 0 to 2:

- N/A: This criterion does not apply to this evaluation.

- 0: There is substantial missing information to be able to judge the quality of the respective criteria.

- 1: There is some - but limited - information, and the component requires significant improvement.

- 2: There is substantial and satisfactory information for the criterion and the evaluation component is robust. In some cases, a margin for improvement is possible.

Impact evaluations were scored as robust (a score of 2) if they included suitable experimental, quasi-experimental or theory-based methods that were appropriate and proportionate in the context of the project and were supported by a justification of the choices made on design and methods. Often the most robust evaluations for Major Projects use a combination of these approaches. This definition goes further than the 2019 review by recognising that theory-based approaches can be valuable for some Major Projects and that, whilst experimental or quasi-experimental design should always be considered where proportionate, these are not always feasible in some cases due to challenges with identification of the comparison group (necessary for experimental and quasi-experimental design). Consideration was also given to the stage of development of the Major Project, for example projects at the Strategic Outline Case stage would not be expected to have as detailed evaluation plans as those at Full Business Case stage.

The QAT was compared with similar tools such as the NESTA Standards of Evidence[footnote 9] and The Maryland Scientific Methods Scale[footnote 10] to verify its validity and reliability. We also piloted the QAT on five Major Project evaluations, and shared the results, along with the QAT, with the ETF, representatives from the CGEG and the IPA for their feedback.

The tool was used by the review team which was made up of over 35 specialist evaluation policy area reviewers from Ipsos UK and Ecorys.[footnote 11] The QAT was specifically designed to ensure rigour and consistency of review findings and was supported by supplementary guidance and benchmarks to assist reviewers with their assessments. This guidance aimed to reduce differences in judgement and variability in scoring. Additionally, the ETF ensured the review team had sufficient context and gave peer support throughout the assessment period and participated in consensus workshops to ensure the QAT was both understood and applied consistently. The core Ipsos UK team oversaw a quality assurance process for the 104 assessments carried out (see Annex 1).

2. The GMPP Evaluation Landscape

This section presents information on the nature of Major Projects and an overview of how evaluation is carried out across the GMPP.

2.1 The nature of Major Projects

The GMPP receives independent scrutiny and assurance from the IPA, the Government’s centre of expertise for Major Projects, which works across government to support the successful delivery of all Major Projects. The IPA categorises Major Projects in four categories based on the projects’ purpose and the nature of their delivery.[footnote 12]

Figure 2.1: GMPP Categories - number of projects, average project length and average whole life cost

ICT

- 32 projects

- Average whole life cost: £1.2bn

- Average length: 7.92 years

Government Transformation and Service Delivery

- 91 projects

- Average whole life cost: £1.5bn

- Average length: 5.61 years

Military Capability

- 45 projects

- Average whole life cost: £5.1bn

- Average length: 19.76 years

Infrastructure and Construction

- 76 projects

- Average whole life cost: £5.3bn

- Average length: 11.63 years

Major Projects are delivered by 21 departments across government, with the Ministry of Defence (MoD) delivering over a fifth of the portfolio with 52 projects. The MoD is responsible for all the 45 Military Capability projects, as well as five Information and Communication Technology projects and two Infrastructure and Construction projects. The Ministry of Justice (MoJ) has the second largest portfolio, with 27 projects among which 13 are Government Transformation and Service Delivery projects. Other departments delivering Major Projects include the Department for Transport (DfT) which has the third largest portfolio and the largest monetised benefits of any department, HM Revenue and Customs, the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ), and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), which have smaller portfolios. Departments often take a portfolio approach to govern these Major Project investments, ensuring projects are aligned with their specific strategic objectives.

2.2 Evaluation within the GMPP

Major Projects take different approaches to how they organise and carry out evaluations. Within the GMPP, particularly in relation to Infrastructure and Construction projects, evaluation can take the form of:

- Multiple evaluations covering different elements of a single Major Project. This is the case where the information needs around Major Project delivery change regularly, and active learning and adaptation is required, or where the Major Project covers multiple stakeholders and contexts which lend themselves to different evaluation approaches;

- A single evaluation, or the use of a consistent approach across evaluations, covering multiple Major Projects (portfolio evaluation). This is the case where several Major Projects have similarities that warrant a joined-up approach to support inter-project comparison and learning. This is the case, for example, for several DfT Major Projects such as rail and road upgrades where similarities between the projects warrant a consistent approach.

The evaluation of the Major Projects is an extensive process, requiring the concerted effort of a sizable and diverse group of individuals, each playing a critical role. These individuals undertake a variety of roles including Project Managers, Evaluation/Research Officers, Data Analysts, Benefits Analysts or Benefits Managers, Field Researchers, Project Delivery Advisors, and Senior Responsible Owners (SROs). These roles encompass everything from day-to-day project delivery (and project progress), designing and executing evaluations, data collection, economic analysis, data analysis and interpretation, providing expert guidance, benefits tracking, and having ultimate accountability for the project’s completion and success (on time and within budget).

2.3 Key stakeholders involved in Major Project evaluation

Government departments are responsible for evaluating their own policies, projects, and programmes. Evaluations are designed and conducted by analysts within the department, working with policy and delivery officials. Under the 2021 IPA Mandate, each government department is required to publish a detailed review of its Major Projects as well as a list of the Senior Responsible Owners (SRO) who are accountable for the Major Projects’ successful delivery.[footnote 13] Central government departments are also required to publish a strategy for evaluation within the department and these strategies are available on the ETF website.[footnote 14]

To support and challenge government departments on the evaluation, and drive improvements in their evaluation practices, the ETF was set up in April 2021, as a central Cabinet Office and HM Treasury unit. It provides departments with both “reactive” evaluation advice and support, in response to department requests, and “proactive” scrutiny and challenge functions guided by HM Treasury priorities and government’s key interests. The ETF’s current support function for Major Projects includes:[footnote 15]

- advice on evaluation approaches from ETF evaluation experts following a departmental account manager model

- use of the Evaluation and Trial Advice Panel, a panel of government and external evaluation experts providing specialist advice on designing and delivering evaluation[footnote 16]

CGEG provides additional support to government departments in their evaluation. The CGEG forms a community of practice of cross-disciplinary evaluation specialists across HM Government aiming to improve the supply of and stimulate demand for quality evaluation. It shares good evaluation practices and delivers improvement projects.[footnote 17]

The IPA oversees Major Project delivery. The IPA reports to the Cabinet Office and HM Treasury and acts as the HM Government’s centre of expertise for infrastructure and Major Projects. It was formed in January 2016 after the merger of the Major Projects Authority and Infrastructure UK. The IPA provides independent scrutiny and assurance of Major Projects and specialist project delivery, commercial and financial advice delivered by expert teams in the IPA. It develops the government’s project delivery profession by providing skills and expertise and training and makes recommendations to improve successful delivery. The IPA also advises HM Treasury Ministers on which Major Projects are ready to proceed through the next stage-gate.[footnote 18]

2.4 Tools to support evaluation of Major Projects

To support and guide evaluation of Major Projects, key tools are accessible to those working on the GMPP:

- The Green Book:[footnote 19] guidance issued by HM Treasury on the design and use of evaluation before, during and after policy, programme, and project implementation. HM Treasury has also published various materials to provide supplementary guidance on how to appraise policies, programmes, and projects;

- The Magenta Book:[footnote 20] sets out government guidance on evaluation methods, use and dissemination. It differentiates between process, impact, and value for money evaluations. It is owned by HM Treasury and is reviewed and updated every five years by the ETF.

- The Public Value Framework:[footnote 21] designed by HM Treasury to support government departments in tracking value for money.

In addition to this list, several departments also have their own evaluation guidelines and tools available to projects teams.

2.5 Current requirements on Major Projects

Major Projects are subject to Green Book and Magenta Book guidance which set out clear evaluation requirements, but there is limited formal guidance on specific evaluation requirements for Major Projects. More broadly, government departments must publish detailed information on project status, including actions taken, financials, schedule, and the Delivery Confidence Assessment (DCA) rating (green for probable success, amber for feasible but with issues, red for unlikely success). Senior Responsible Owners provide assessments, unless the project has active IPA support or independent IPA assurance in the last six months, in which case the IPA conducts the DCA. Data from GMPP projects is published alongside the IPA’s Annual Report, including the full list of Major Projects and aggregated data.[footnote 22] According to the recent Annual Report, Major Projects must provide quarterly data on delivery progress and monetised aspects. Oversight involves the IPA Assurance Gate Review process[footnote 23], data tracking of all GMPP projects for analysis and benefits reporting, and expert advice from IPA teams to improve project delivery.

3. Key findings

This section summarises the findings of the review in relation to the scale and quality of evaluation, as well as a discussion of some of the barriers and challenges to evaluation among Major Projects and some of the enabling factors.

3.1 The prevalence of evaluations across the GMPP

According to the 221 Major Project teams who replied to the ETF’s questionnaire at the end of 2022, nearly three quarters of these 221 projects either had an evaluation planned but had not yet started (39%), had an evaluation in progress (26%), or had an evaluation completed (10%). In total, this amounts to 164 out of 221 responding projects (or 67% of all Major Projects) with some sort of evaluation or plans for one[footnote 24]. However, only 104 (43% of all Major Projects) were able to share documents to evidence this (see Table 3.1).[footnote 25]

Table 3.1: Government Major Projects: Evaluation plans

| All Major Projects | Major projects that self-reported to have evaluation plans in place | Major projects that shared an evaluation plan |

|---|---|---|

| 244 | 164 | 104 |

| 100% | 67% | 42% |

52 out of the 221 responding stated that they had no plans to evaluate their project. Of these projects, all four IPA project categories were represented (see Figure 3.1), but Military Capability projects were most likely to report that they did not have an evaluation planned.

Figure 3.1: Evaluation Status by IPA category, as reported to the ETF[footnote 26]

| Status | Transformation and Service Delivery | Information and Communication Technology | Infrastructure and Construction | Military Capability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| There are no current plans to evaluate the project | 5% | 5% | 5% | 8% |

| An evaluation is planned but not yet started | 14% | 2% | 19% | 5% |

| An evaluation is currently in progress | 12% | 2% | 6% | 4% |

| An evaluation has been completed and there are no current plans to evaluate further | 0% | 0% | 1% | 0% |

| An evaluation has been completed and further evaluation is planned | 4% | 1% | 1% | 2% |

| Other / No response | 1% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

Among the evaluation plans shared with the ETF by Major Project teams (for review by Ipsos and Ecorys), over half were ‘Transformation and Service Delivery’ projects while only 15% were ICT or Military Capability projects. This clearly indicates that evaluations are less prevalent among ICT and Military Capability projects.

Table 3.2: Distribution of evaluation plans shared with ETF, by IPA project category

| Category | Transformation and Service Delivery | Infrastructure and Construction | Information and Communication Technology | Military Capability | TOTAL |

| No. of Major Projects sharing plans with ETF | 47 | 43 | 11 | 3 | 104 |

| % of projects sharing plans with ETF out of total portfolio | 19% | 18% | 5% | 1% | 43% |

| No. of Major Projects in portfolio overall | 91 | 76 | 32 | 45 | 244 |

| % of projects out of total portfolio | 37% | 31% | 13% | 18% | 100% |

| Distribution of spending (whole life cost) in the GMPP £Bn | £133 | £403 | £39 | £231 | £805 |

| % distribution of spending | 17% | 50% | 5% | 29% | 100% |

Source: Evaluation plans shared by Major Projects with the ETF, plus data published in the IPA Annual Report on Major Projects 2022-23. Percentages given may not sum to 100% exactly due to rounding.

It was expected that the stage of development of an evaluation plan would be affected by the stage of project development with projects at earlier stages having less well developed evaluation plans. We therefore expected this to be reflected in an association between evaluation status and business case stage.[footnote 27] Unexpectedly, there was no clear relationship between the two, with Major Projects at all stages of the Business Case cycle reporting plans to evaluate and those at later stages, i.e. those that had a Full Business Case, no more likely than those at earlier stages to have an evaluation (see Figure 3.2). Among the 90 projects (out of 221 responding projects) which had a Full Business Case in place, 23 stated that they had no plans to evaluate.

Figure 3.2: Evaluation status by business case stage[footnote 28]

| Status | Strategic Outline Case | Outline Business Case | Programme Business Case | First HMT Business Case pending | Full Business Case | No HMT Business Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| There are no current plans to evaluate the project | 2% | 5% | 2% | 2% | 11% | 1% |

| An evaluation is planned but not yet started | 6% | 8% | 6% | 1% | 16% | 4% |

| An evaluation is currently in progress | 1% | 4% | 6% | 0% | 11% | 3% |

| An evaluation has been completed and there are no current plans to evaluate further | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 1% |

| An evaluation has been completed and further evaluation is planned | 0% | 1% | 0% | 1% | 4% | 1% |

| Other / No response | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

3.2 The design of evaluation and methods applied among Major Projects

3.2.1 The type of evaluation planned / implemented

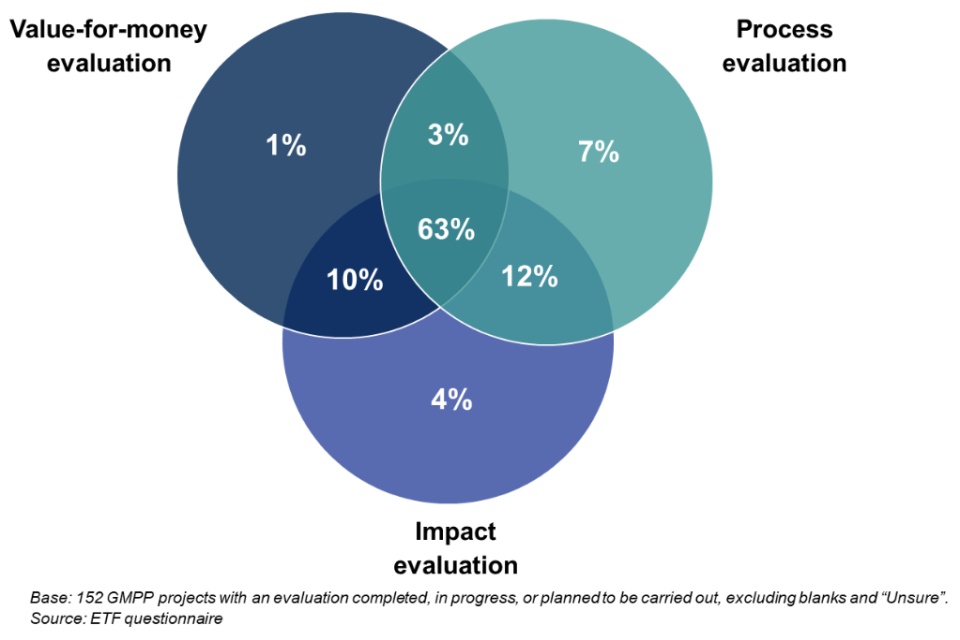

Major Projects were asked about their evaluation plans across three categories: process, impact, and value for money.[footnote 29] Three in five responding projects (63%, n=95) intended to take all three approaches. Only 3% (n=5) were planning or implementing value for money and process evaluations only, 10% of projects (n=15) were planning or implementing impact and value for money evaluations, and 12% of projects (n=18) were planning or implementing process and impact evaluations.

Figure 3.3: Combination of evaluation approaches[footnote 30]

3.2.2 The types of evaluation methods being used

- Among those reporting to ETF that they had evaluations completed, in progress, or planned (n=162), the largest proportion (37%, n=60) were implementing, or planning to implement, before and after studies; 20% (n=33) were conducting theory-based evaluations, and 17% (n=28) were taking quasi-experimental approaches. None of the projects reported taking experimental approaches.

Figure 3.4: Evaluation methods being used by Major Projects (among those reporting to the ETF that they had an evaluation planned, in progress, or completed)

| Method | % |

|---|---|

| Before and after study | 37% |

| Theory-based | 20% |

| Quasi-experimental | 17% |

| Other | 22% |

| Empty responses / those reporting ‘none’ | 3% |

Source: Nature and status of evaluation plans, as reported by 221 / 244 Major Projects to the ETF. Percentages given may not sum to 100% exactly due to rounding.

This lack of experimental and quasi-experimental methods was reported as being either because they are whole population interventions, where a control group is not easily identifiable, or because the projects operate in complex environments where other drivers or wider systemic factors are challenging to measure or control. In other cases, counterfactual approaches which may have been possible, had become challenging due to a lack of an appropriate sample (which would have needed to have been formulated and planned at the early stages of project development) or because the data had not been collected prior to the launch of the project. Or in some cases these approaches may simply not have been considered.

3.3 The quality of evaluations among Major Projects

Reviewers considered evaluation plans to be of good quality when there was clarity, logic and coherence of objectives, information needs, evaluation scope and design and transparency around the methods to be used, their limitations and justification for their selection.

Quality of evaluation methods were judged according to the following guidance:

- Process evaluation - If there is a process evaluation, as a minimum there should be an explanation on its aims, evaluation criteria and evidence to answer the research questions;

- Impact evaluation - If there is an impact evaluation, as a minimum there should be an explanation on the most feasible approach and the choices made. Potential approaches are theory-based, experimental and quasi-experimental and should be robust and proportionate to the context of the project;

- Value for money - If there is a value for money evaluation, as a minimum there should be an explanation on the most feasible approach, the choices made, costs and benefits, and valuation methods. Potential approaches include Cost Benefit Analysis or Cost Effectiveness Analysis (depending on feasibility). For additional reference to value for money see: NAO (2023) - Successful commissioning toolkit: Assessing value for money.

3.3.1 Impact, process and VfM evaluation quality

The figure below illustrates the quality of impact, process and value for money evaluation plans among Projects who shared documentation. Although the majority of impact evaluation plans reviewed were robust, only around half of those with plans for process and value for money evaluations were rated robust.

Figure 3.5: Quality of evaluation by approach

| Category | Total |

|---|---|

| Number of projects reviewed | 104 |

| Had plan for impact evaluation | 62 |

| Had plan for impact evaluation and were robust | 53 |

| Had plan for process evaluation | 49 |

| Had plan for process evaluation and were robust | 24 |

| Had plan for value for money analysis | 47 |

| Had plan for value for money and were robust | 23 |

Source: Nature and status of evaluation plans, as reported by 221 / 244 Major Projects to the ETF. Note that 104 out of 221 were reviewed.

3.3.2 Other considerations of quality

The key findings for other aspects of evaluation quality are listed below:

- Evaluation aims, questions and scope were articulated well in 70-75% of the plans reviewed;

- There was a clear conceptual framework in 61% of the plans reviewed;

- The evaluation scope was considered robust and proportionate in 46% of cases;

- The data collection methodology was clearly explained in 51% of evaluation plans reviewed;

- The data analysis approach was clearly explained in 35% of the evaluation plans reviewed;

- The limitations were considered comprehensively described in only 38% of the plans;

- Only 15% of the plans reviewed made reference to and/or evidenced application of appropriate ethical guidelines.

Figure 3.6: The quality of evaluation plans against criteria of coherence, clarity and transparency, and logic of design

| Criteria | 0 | 1 | 2 | Not applicable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clear aims | 4 | 27 | 73 | 0 |

| Clear research questions | 17 | 18 | 69 | 0 |

| Application of the evaluation | 9 | 30 | 65 | 0 |

| Conceptual frameworks | 13 | 29 | 62 | 0 |

| Clear target audience | 20 | 30 | 54 | 0 |

| Research design consistent with aims and purpose | 16 | 27 | 61 | 0 |

| Evaluation approach consistent with the aims, objectives and research questions | 20 | 23 | 61 | 0 |

| Evaluation scope proportional | 29 | 29 | 46 | 0 |

| Clear data collection methodology | 19 | 35 | 50 | 0 |

| Clear stakeholder engagement strategy | 43 | 28 | 33 | 0 |

| Adequate sampling strategy adequate for the study aims and research questions | 30 | 37 | 27 | 10 |

| Clear data analysis | 34 | 33 | 37 | 0 |

| Discussed limitations of the evidence / method | 34 | 34 | 36 | 0 |

| Reference/application of appropriate ethical guidelines | 68 | 25 | 11 | 0 |

Note: Not applicable refers to cases where no primary data collection was foreseen. N=104 projects reviewed

The quotes from reviewers below further illustrate what they considered good and less good practice to look like.

Positive feedback on the plans

“The plan includes good consideration of the advantages (e.g. good data availability) and challenges (e.g. operational complexity and lack of counterfactual options) faced when evaluating this type of programme.”

“Very clear and accessible. Considerable effort has been put into the design of the document, making it easy to read and navigate.”

“The evaluation report is incredibly comprehensive, clearly linking the aims, programme mission, conceptual framework, research questions and data collection together throughout. This is a very comprehensive evaluation plan for a large scale evaluation but will take significant time to develop into a report. It is a good example and proportionate for this evaluation but not for smaller scale programmes.”

Where feedback on the plans was less positive this was often because the document shared was serving a different purpose, such as benefits realisation, and was not an evaluation plan:

“This is a product review, not evaluation.”

“The document is more of a monitoring and reporting framework. There is scope to evaluate some key qualitative benefits and assumptions, such as the extent to which this project facilitates business change, beyond just dashboard reports.”

“This is a benefits management document which considers solely the programme perspective and fails to address the basic rationale for evaluation and any clear programme evaluation approaches (process and impact).”

“The document available for review is a benefits realisation update report. There is no explicit reference to evaluation.”

“The document shared is a ‘How To’ guide focusing on “identifying the monitoring and measurement activities already underway or planned, and therefore identifying where newly scoped evaluation activity would be justified. Where such evaluation is justified, this guide offers suggestions for how it could be undertaken, when and what resources could be needed.”

There were also examples where the plan was considered to have been insufficiently tailored to the project concerned:

“The aim of an evaluation should be coherent with its objectives - that is, the objectives should reflect what the evaluation will try to achieve in order to meet the overall aim. Clearer statements of rationale, aims, and then objectives should meaningfully flow from each other, and not be a tick box exercise.”

3.4 Barriers and challenges to evaluation among Major Projects

3.4.1 Practical challenges: The resources available for evaluation

Among those Major Projects responding to the ETF questionnaire question on evaluation status (n=162), some reported that they did not have sufficient resources (staffing and financial) for evaluation and/or backing from senior colleagues / hierarchies. In interviews, the influence that Ministers have over decisions as to whether to evaluate or not was also highlighted. In the desk-based review of the 104 evaluation plans shared with the ETF, scoring was quite mixed on the resources apparently available for the evaluation, as set out in Table 3.3.

Table 3.3: Reviewers’ assessments of three components of resource availability for the 104 evaluation plans reviewed

| Category | 2-Robust | % |

| Deliverability - evidence of a robust approach to project management of the evaluation | 28 | 27% |

| Availability of staff resources | 32 | 31% |

| Availability of financial resources | 34 | 33% |

Note: Number of projects considered robust in these criteria out of 104 projects reviewed

Insufficient dedicated funding for evaluations and a lack of expertise within the evaluation teams were recurring themes identified across all research strands for this review. Many projects struggled with inadequate financial resources to conduct in-depth evaluations, leading to hasty or incomplete assessments of project outcomes. The absence of qualified evaluation teams also posed a risk of compromised findings due to insufficient analysis or interpretation.

In the interviews with Major Project teams, having a credible and effective evaluation governance system in place for the evaluation was deemed to be a crucial element for a successful evaluation. Having such governance systems in place supported high quality, useful evaluation.

“The team put in place an evaluation working group made up of people from the various delivery partners to guide and provide input throughout the evaluation process and made sure all partners were onboard with deadlines and decisions. [We] also had an expert advisory group of independent academics and specialists to provide input at key stages of the evaluation. These two groups were very useful and met on an ad-hoc basis when needed.”

Effective collaboration between policy and analytical teams across government departments was consistently highlighted as something ‘working well’ in successful evaluations, with an interviewee highlighting:

“We have benefitted from close working between social research and policy teams. Social research commissions the evaluation but draws upon the needs of the policy teams. This is key; there is often a lot of information and context that social researchers overlook. And taking time at the start to draft the ITT together and share it around helps.”

3.4.2 Challenges in changing the status quo (‘cultural’ challenges)

In their responses to the ETF question on evaluation status (n=221), some projects reported that the concept of evaluation was relatively new and maturing among the department responsible and this was a reason for them not being able to share an evaluation plan. Other reasons for not sharing evaluation plans (or having them in place) included:

A consideration that where the Major Project concerned standard re-procurements or business as usual services, these would not necessarily be required to undergo evaluation as they are considered routine and essential (so there is less opportunity for learning and adaptation).

There is a significant variation in the culture of evaluation across Government. For example, in one example, the Major Project was in its fifth iteration, but there were no evaluations of the programme until now. According to an interviewee, the culture of evaluation in their department is “improving” but is still not quite at the levels of literacy and understanding across the board that they would expect.

Different types of evaluations are also valued differently by different teams and stakeholders. This may result in conflicting interests across government departments of what is needed or necessary. Some policy teams’ value and use the findings from process evaluations, though there are others who clearly value findings on value for money and impact. Several projects already have assurance, auditing, or performance monitoring processes in place which – they believed – served a similar purpose and generated comparable value to evaluations (see section 2.2 for more discussion on the variety of methods used within the GMPP).

Evaluation is sometimes seen as a ‘luxury’. The perception that evaluation was not valued by some Ministers or considered a ‘nice-to-have’ which should be sacrificed where spending is tight came up in several interviews. It is also something that is reflected in the desk research, which revealed a significant absence of evaluation plans across the GMPP. The two quotes below are taken from the qualitative interviews with Major Project teams:

“Where does evaluation rank in Ministerial priorities?”

“Evaluation always feels like ‘the poor partner’ and [I am always] banging the drum for evaluation – are [policy] leaders engaging because they see the value or because they feel they need to?”

In terms of positive practices identified:

- There was a general agreement among interviewees that they had either been aware of or used the ‘Magenta Book’ and ‘Green Book’ for evaluation design;

- The use of government and departmental support was also common across interviewees. All of the interviewees were able to reference support they had received with their evaluation, specifically from evaluation professionals within their department or other departments across government;

- Several evaluation teams had regular interactions with the ETF which proved immensely valuable.

Example 1: Transformation and Service Delivery project, stakeholder engagement

One Major Project interviewee stressed the importance of comprehensive communication and collaborative work. The project team mentioned the implementation of a multifunctional team approach which facilitated this. Documentation was maintained for future reference during the project implementation, preserving institutional memory.

Example 2: Transformation and Service Delivery project, stakeholder engagement

The interviewees for this Major Project strongly advocated the importance of relationship-building, especially the positive relationship between policy team and evaluators, which enhanced project success. They also stressed the need for early involvement in evaluation and embedding evaluation requirements leading to smoother and more efficient processes.

3.4.3 Operational challenges

The necessity of data for evaluation of Major Projects was a common theme across the qualitative interviews conducted. The challenges faced included:

- Problems with the quality of data collected;

- Absence of data where effective data collection systems had not been embedded at the right time into the interventions’ management systems; or data collection activities had not been set up in a timely manner;

- Problems in accessing data where the necessary data sharing agreements had not been set up effectively / on time;

- Challenges reaching sub-populations, such as young people, in the evaluation process. The difficulty in engaging these specific groups affected the overall inclusivity and representativeness of the evaluation, potentially leading to incomplete or biased findings.

Example 3: Infrastructure and construction project

Address-level data for this Major Project was not fully available. The team overseeing this policy and the evaluation commented that, with hindsight the following should have been done:

Better scoping of data needs prior to the designing of an evaluation.

Engaging evaluation advice as early as possible – right at the point of funding – in order to establish the need for a counterfactual, additionality model, data sources, etc so that these may be built in from an early stage.

Setting up of appropriate and effective processes for sharing data across departments - according to the Major Project team, this would entail understanding the data being held in different databases by central government departments and local government.

Recognising the evaluation as a valuable part of the Business Case process.

Within some Major Projects there was sometimes a tension between the need for quick programme launch and the need to allow enough time for scoping and identifying the necessary data for evaluation purposes. Such quickfire decision-making does not always allow enough time for setting up the necessary relationships for evaluation projects to succeed. Major Projects also highlighted the need for a flexible evaluation design that could respond to changing circumstances. This featured as a central theme across interviews, as did the challenge of scaling up the programme unexpectedly to procedural modifications due to external events (like COVID-19). This highlighted the critical need for flexibility in evaluation design for Major Projects.

Example 4: Tracking data on long-term transport systems upgrading

One of the many challenges within this Major Project was the very large scale of the project and the uncertainty of timelines to finalising the build. To overcome the challenges, the team designed a multi-stage evaluation that focused on key outcomes realised at different stages during and after the delivery of the intervention.

Example 5: Transformation and Service Delivery project

One Major Project applied an agile or ‘test and learn’ approach to data analysis and evaluation. This was presented in the report as successful as it involved rapid feedback and iterations rather than lengthy evaluations that might lose relevance over time. Quick decision-making, adaptability and resource management played a significant role in the project’s success.

3.5 Contextualising the evidence available for this review

A total of 162 (out of 244) Major Projects reported that they had plans to evaluate their projects, but only 104 were able to share any evidence of this. In some cases, Major Projects responding to the ETF questionnaire provided the following reasons provided for not sharing evidence of a plan:[footnote 31]

- Where the project is part of a larger portfolio of projects, the Major Project teams sometimes reported that they had excluded separate project evaluations (even where several projects within their portfolio were separately considered Major Projects). This is because they considered it inappropriate, disproportionate and lower value for money to evaluate each project separately.

- Some projects in early phases of procurement or delivery were sometimes reported to be still developing assessment frameworks or awaiting evaluations to be scheduled. This could be the case, for example, for projects with particularly long delivery timeframes, where evaluation planning may reasonably be at an earlier stage of development and so full documentation was not available to review.

In these cases, the lack of evaluation plan evidenced at the time of this review does not necessarily mean that these Major Projects will not put in place robust evaluations. Indeed, for some projects with very long impact timeframes, the implementation of further evaluation activity may even occur after the project has left the GMPP.

The review necessarily relied on Major Projects providing evidence of their evaluation plans for assessment. It is a reasonable expectation that Major Projects will have documentation of their evaluation plans. In addition, evidence for some aspects of the quality assessment tool used in this review, such as ethical processes, staff resources or how the evaluation is resourced and managed, are sometimes documented separately to evaluation plans and therefore may not always have been identified within the review process. It is therefore possible that these aspects were underestimated in the review findings.

4. Recommendations

This section sets out recommendations based on the evidence of the review, for consideration by the ETF, HM Treasury, IPA and government departments.

4.1 Recommendations to address challenges to evaluation delivery

Recommendation 1: Reinforce evaluation requirements, its benefits and the standards set in existing government guidance:

R 1.1 Promote the value of evaluating Major Projects across government, to senior leaders, Ministers and Members of Parliament, as well as those involved in the design, delivery, support and assurance of Major Projects.

R 1.2 Demonstrate how evaluation can be built into the design and implementation of Major Projects, facilitating learning and accountability. This should include what data would be needed to measure success at the very initial stages of project design and developing an integrated data collection and analysis system for the further stages of evaluation.

R 1.3 Ensure there are clear standards and expectations of what constitutes a robust and proportionate evaluation approach to all types of Major Projects, providing clear signposting to guidance, advice, and support.

R 1.4 Raise awareness of evaluation design methods and the tools required to deliver these, building on extensive existing resources that are available in government and externally, notably in: (1) promoting the use of the most robust causal evaluations methods, including experimental and/or quasi-experimental designs where feasible and proportionate, as well as robust theory-based designs, (2) approaches to use in situations where there is no clear counterfactual design, and/or (3) where the project has unique or hard to measure benefits and outcomes.

R 1.5 Ensure Major Project teams are aware of the upcoming requirement to register their evaluation plans and outputs in the ETF’s Evaluation Registry and this is monitored to ensure compliance.

Recommendation 2: Embed evaluation into department and central approvals, assurance and governance for Major Projects:

R 2.1 Ensure that evaluation evidence and plans inform Major Project approval decisions and that there are sufficient governance arrangements as well as resources to develop and deliver good quality evaluations, monitor their progress, and provide appropriate scrutiny and assurance.

R 2.2 Ensure there are mechanisms to provide additional support and/or scrutiny of the evaluation and escalation, where necessary, and to ensure that evaluation findings are used to inform project improvements and/or future policy decisions.

R 2.3 Strengthen the requirements for evaluation plans included in Major Project business cases and assurances, ensuring evaluation is built in from an early stage and that the benefits of evaluation can support effective Major Project delivery. This should include the relevant HM Treasury, IPA and departmental processes.

R 2.4 Foster collaboration with relevant data custodians and stakeholders to establish data-sharing agreements and improve data accessibility for evaluation purposes.

R 2.5 Ensure evaluation of Major Projects is adequately resourced from project budgets reflecting the objectives of the business case. Where necessary advice may be sought from evaluation professionals across government.

Recommendation 3: Develop evaluation capability and invest in good data infrastructure:

R 3.1 Ensure that analysts as well as project delivery staff and benefits leads working on Major Projects have the knowledge and skills required to deliver robust and proportionate evaluations of Major Projects.

R 3.2 Project teams should work more closely across departments and central evaluation support networks, including the ETF, to draw on existing expertise in evaluation to understand how it could work best for the project concerned.

R 3.3 Support access to good quality data/data infrastructure, or the means to collect or create it, and appropriate evaluation methods suited to the specific context of Major Projects.

R 3.4 Invest in data infrastructure and systems to ensure data reliability and quality. This will strengthen the credibility and rigour of the evaluation process, leading to more informed decision-making, valuable insights, and project and policy learning.

R 3.5 Raise awareness of and strengthen professional networks of evaluators to support continuous learning, innovation and build capacity to design and deliver high quality and successful Major Project evaluations.

Annex 1: Methodology

Figure A.1.1: A snapshot of our methodological choices

Synthesis and triangulation of evidence

| Data collection activities | Type of evidence |

|---|---|

| - Descriptive analysis of ETF questionnaire responses (n=221) | - Broad and comprehensive data on evaluation arrangements within GMPP |

| - Desk research of documents and evaluations plan for 104 evaluations - Qualitative and quantitative assessment of the robustness of evaluations |

- Reach evidence of the quality of the evaluations within GMPP |

| - 42 semi-structured interviews | - In-depth evidence on evaluation arrangements for selected Major Projects - Better understanding of enablers, barriers, challenges, and examples of good practice |

The first phase of research was a questionnaire sent by the Evaluation Task Force (ETF) to Major Project teams. A descriptive analysis of responses to this questionnaire helped us gather valuable data from many projects to understand the extent of evaluation going on across the GMPP and to spot common patterns and trends. The ETF received 221 responses out of the total 244 projects on the GMPP, achieving an 91% response rate.

As part of the questionnaire sent by the ETF, Major Project teams were asked to share any relevant supporting documentation about the evaluation arrangements in place for their projects. A total of 104 projects shared information which were then reviewed by the team. This allowed us to tap into a wealth of existing information and gain deeper insights into the quality of evaluation plans for a selection of Major Projects.[footnote 32]

Lastly, we conducted 42 in-depth interviews with members of the project teams, regardless of the availability of evaluation plans. These interviews provided us with valuable first-hand perspectives and deeper qualitative insight to support the review of evaluation plans. They helped us explore complex issues more deeply and better understand the challenges, barriers, solutions, and opportunities. Out of the 52 potential interviewees we reached out to, we scheduled 42 interviews, achieving more than our initial target of 40. The number of individual interviewees was approximately twice the number of interviews because each interview was held with two or more project team members. Interviewees included M&E leads, research team leads, benefits analysts, and social researchers working within Major Projects, and three of the 42 interviews were with Senior Responsible Owners (SROs).

Combining these three methods ensured a well-rounded review of the scale and quality of evaluations within the GMPP. The combination of quantitative and qualitative evidence helped us validate our findings and comprehensively understand the subject.

Analysis of ETF questionnaire returns

On the 1st of December 2022, the ETF sent a questionnaire in a spreadsheet by email to the 244 project teams to gather information about their evaluation arrangements, due by 21st of December. The questions centred around existing or planned evaluations, the status of ongoing evaluations, and whether there were process evaluations, impact evaluations and value for money evaluations in place —additionally, the questionnaire covered topics related to research design and the resources available for managing the evaluation, as well as a section on benefits.

Out of 244 projects contacted, 221 completed the questionnaire, achieving an 91% response rate. The ETF shared completed returns with Ipsos UK for analysis. This evidence gave a first understanding of the scale of evaluations across departments, which helped plan the allocation of reviews among the panel of specialist evaluation experts and reflect on the most appropriate tool for assessing the quality of evaluation plans.

The primary advantage of this data lies in its extensive coverage of evaluations, approaches, methods, and other pertinent information on a large scale and in a quantitative way. However, there is limited insight into the underlying factors behind the responses, such as barriers and enablers, which influence the identified patterns. Finally, while every effort was made to ensure consistent responses, there may also be some difference in how respondents self-reported their evaluation approaches. A review of evaluation plans through desk research and interviews sought to fill in these gaps.

The questionnaire is presented in Annex 4.

Review of evaluation plans

This activity aimed to review and assess the quality of evaluation plans in the GMPP portfolio. The ETF asked project teams to share relevant documents, and these were subsequently shared with the review team in Ipsos UK and Ecorys UK. We obtained documents for 104 Major Projects. Importantly, the review team included two partner organisations to avoid conflicts of interest, as Ipsos UK is involved in multiple evaluations within the GMPP.

To assess the quality of evaluations in the GMPP we developed a bespoke Quality Assessment Tool (QAT). Use of existing frameworks including the Nesta Standards of Evidence and the Maryland scale were considered,[footnote 33] but we realised a more nuanced approach was required to reflect the diverse and complex context of evaluations within the GMPP. Our bespoke QAT was designed to accommodate varying policy contexts, durations, and sizes. The QAT was developed iteratively with support from the ETF who sought extensive feedback from stakeholders including CGEG and representatives from the IPA. Following initial testing and the incorporation of feedback the QAT was signed off by the ETF.

In assessing the quality of Major Project evaluation plans we recognised their complexity and diversity. Impact evaluations were scored as robust (a score of 2) if they included suitable experimental, quasi-experimental or theory-based methods that were appropriate and proportionate in the context of the project, and were supported by a justification of the choices made on design and methods. Often the most robust evaluations for Major Projects use a combination of these approaches. We compared the QAT with other quality assessment methods (e.g. NESTA, Maryland Scale) used in systematic literature reviews for qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies to guarantee validity and reliability. Different reviewers from the ETF, CGEG, IPA, Ipsos UK, and Ecorys UK also tested the QAT on different evaluations to ensure consistency.

The QAT also gave consideration to the delivery and business case stage of Major Projects, recognising that evaluation plans are usually refined and developed iteratively over the lifecycle of a project. The business case stage was incorporated into the tool to enable reviewers to take it into account during the assessment. This addition was approached cautiously, recognising the challenge of accurately judging the evaluation planning considering different projects’ lifecycle.

The QAT consisted of questions around aspects of the evaluation grouped under three categories:

- Aims, objectives and research questions;

- Research design and evaluation approach;

- Resources and management.

Each aspect of the evaluation plan was ranked on three levels:

- 0: There is substantial missing information to be able to judge the quality of the respective criteria;

- 1: There is some –but limited– information, and it requires significant improvement;

- 2: There is substantial and satisfactory information for the criterion. In some cases, a margin for improvement is possible;

- N/A: This criterion does not apply to this evaluation.

The QAT was accompanied by a detailed guidance document and a glossary which also suggested benchmarks to assist reviewers, aiming to reduce differences in judgement and variability among them. The QAT and associated guidance is presented in Annex 2. Additionally, we held internal briefing and Q&A sessions with the expert review panels to ensure the QAT was both understood and applied consistently.

Once we finished piloting the QAT, the review process started by allocating evaluation plans among senior evaluator experts from Ipsos UK and Ecorys UK with specific policy expertise.

An early key finding of this review was the absence of comprehensive documents for each project within the GMPP. Further, the quality of the available documents varied significantly. For instance, in some cases, there were highly detailed evaluation plans and multiple documents available for each project. However, in other cases, we only had access to a simple PowerPoint presentation with limited information about the evaluation. One of the potential reasons for this variability is the different stage in which evaluations are within this portfolio, however this did highlight a lack of visibility of evaluation plans in the majority of Major Projects in this review.

Semi-structured interviews

Following the assessment of evaluation plans, we conducted semi-structured interviews to collect comprehensive evidence about the evaluation process within the GMPP. The interviews focused on understanding the main obstacles faced in planning and delivering evaluations and identifying examples of successful practices for overcoming challenges. We developed a topic guide for interviewers based upon the findings of the previous stages of the review. Interviews were undertaken by senior evaluation experts with subject specific knowledge.

We selected interviewees in collaboration with the ETF and the IPA to ensure a diverse representation of Major Projects from different departments, various stages of evaluation, and distinct approaches to evaluations. Additionally, we considered whether they had shared documents for review as part of their evaluation approach. Interviews were around an hour with a maximum of two colleagues from each project. To achieve a target sample of 42 interviews, we reached out to 54 people.

The topic guide was structured around four major themes:

- Background of the project and role of the interviewees;

- Project evaluation and research design;

- Barriers and enablers of the evaluation;

- Benefit realisation of the project.

The topic guide followed a semi-structured format considering the diversity and heterogeneity of projects and interviewees’ roles. The topic guide was developed incorporating feedback from reviewers and ETF colleagues.

Analysis and synthesis

We used MS Excel© to analyse the quantitative data, and NVivo©, a qualitative data analysis software, to analyse interview transcripts. Once we imported the transcripts into NVivo©, we took time to understand the content and recurring themes. To organise the data, we used NVivo’s coding feature and refined the codes step by step. With NVivo’s visual tools, we also explored relationships between themes.

Quality Assurance

To ensure quality we have embedded principles consistent with the Aqua Book:

Overarching / through our team: We brought together a large team of specialist evaluators covering expertise in a range of evaluation methodologies, experience in the evaluation needs of different Major Project types, and experience of working with and producing advice and support for government on evaluation.

Quality of design: Our group of experienced Associate Directors collaboratively designed the Quality Assessment Tool, consulting with our Major Projects Advisory Group (on how to probe / assess evaluation needs) and our Methods Expert Group (on how to probe into methods quality). In the second phase of the study, tools and guidance were developed in discussion with the ETF. Our policy and methods specialists led on the development of these tools, drawing on experience of ‘what works’ in developing similar tools for Government departments.

Quality of analysis: The full team of evaluation specialists worked together to review the Major Projects. The review team attended a ‘quality scoring calibration meeting’ to run through their scores and assessments and the rationale behind them. Areas for adjustment were identified and addressed.

Quality of reporting: The Quality Director reviewed all outputs going to the ETF and was available to brainstorm ideas and offer views on reporting throughout the project.

Annex 2: Quality Assessment Tool for reviewing evaluation plans

Please note:

- Assessments are just the first pass, and their purpose is to inform the next stage of the review where Ipsos will be carrying out in-depth interviews with a range of stakeholders involved in Major Projects.

- These assessments have only been carried out for projects where enough evaluation information was available via supporting documents, and we appreciate there will be gaps in the information provided. All remaining projects will be included in a separate analysis using the information returned in the Excel templates (from the ETF questionnaire).

- Review findings will not include project specific findings so these assessments will not be published or shared further than the review team (Ipsos, ETF and IPA) and those involved in the project itself.

- Projects where an evaluation has been planned or delivered by Ipsos have been reviewed independently by Ecorys.

| Score/response | Judgement criteria for scores |

| Open-ended | The reviewer provides a narrative |

| Closed | The reviewer chooses one option |

| N/A | This criterion does not apply to this evaluation |

| 0 | There is substantial missing information to be able judge the quality of the respective criteria |

| 1 | There is some –but limited– information, and it requires significant improvement |

| 2 | There is substantial and satisfactory information for the criterion. In some cases, a margin for improvement is possible |

Table A.2.1: Quality assessment tool

| Section | Quality criteria | Values |

|---|---|---|

| General information (not for scoring) | ||

| Project ID | open-ended | |

| Project Name | open-ended | |

| Lead Department | open-ended | |

| Value of project | open-ended | |

| Length of project | open-ended | |

| Age of project | open-ended | |

| Department | open-ended | |

| IPA category | open-ended | |

| Target groups | open-ended | |

| Background (not for scoring) | ||

| Business Case exists | Yes/No | |

| If yes, at what stage is the Business Case? | N/A (doesn’t exist), strategic outline stage, outline business case, full business case | |

| If yes, have we seen / been given access to the Business Case? | N/A (doesn’t exist), Not been given access, given access but not reviewed for this analysis | |

| Is the project being evaluated / planned to be evaluated on its own or as part of a portfolio of projects? | N/A (no plans to evaluate), single project evaluation, portfolio evaluation | |

| If a portfolio evaluation will be applied, are all of the projects within it in the GMPP? | N/A/Yes/No | |

| Please add here any comments you may have on the appropriateness of the portfolio evaluation approach | open-ended | |

| 1. 1 | Aims and research questions | |

| 1. 1.1 | Are the aims, objectives, and rationale for the evaluation clear? | 0/1/2 |

| 1. 1.2 | Are research questions clearly formulated? | 0/1/2 |

| 1. 1.3 | Is the application of the evaluation clear? | 0/1/2 |

| 1. 1.4 | Is there a clear conceptual framework? | 0/1/2 |

| 1. 1.5 | Is the target audience of the evaluation clear? | 0/1/2 |

| Reviewer’s additional comments on the clarity of scope and design | open-ended | |

| 1. 2 | Design and methods | |

| 1. 2.1 | Is the research design consistent with the evaluation aims and purpose? | 0/1/2 |

| 1. 2.2 | Is the evaluation approach consistent with the aims, objectives and research questions? | 0/1/2 |

| 1. 2.3 | Is the evaluation scope proportional? | 0/1/2 |

| 1. 2.4 | Is there a process evaluation in place? | Yes/No |

| 1. 2.5 | If there is no process evaluation, explain why | open-ended |

| 1. 2.6 | If there is a process evaluation, how robust is the design? | 1. NA/0/1/2 |

| 1. 2.7 | Is there an impact evaluation in place? | Yes/No |

| 1. 2.8 | If there is no impact evaluation, explain why | open-ended |

| 1. 2.9 | If there is an impact evaluation, how robust is the design? | NA/0/1/2 |

| 1. 2.10 | Is there a value-for-money evaluation in place? | Yes/No |

| 1. 2.11 | If there is no value-for-money evaluation, explain why | open-ended |

| 1. 2.12 | If there is a value-for-money evaluation, how robust is the design? | NA/0/1/2 |

| 1. 2.13 | Is the data collection methodology clearly explained? | 0/1/2 |

| 1. 2.14 | Is the stakeholder engagement strategy clear? | 0/1/2 |

| 1. 2.15 | If primary data collection is foreseen, is the sampling strategy adequate for the study aims and research questions? | NA/0/1/2 |

| 1. 2.16 | Is the data analysis clearly explained? | 0/1/2 |

| 1. 2.17 | Are the limitations of the evidence / method comprehensively described? | 0/1/2 |

| 1. 2.18 | Is there reference to and/or evidence of application of appropriate ethical guidelines? | 0/1/2 |

| 1. Reviewer’s additional comments on the design and method | open-ended | |

| 1. 3 | Management | |

| 1. 3.1 | Deliverability - evidence of a robust approach to project management of the evaluation | 0/1/2 |

| 1. 3.2 | Availability of staff resources | 0/1/2 |

| 1. 3.3 | Availability of financial resources | 0/1/2 |

Table A2.2: Guidance for the quality assessment tool

| Background information (NOT SCORED) | Values | Benchmark | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Business Case exists | Yes/No | ||

| If yes, at what stage is the Business Case? | N/A (doesn’t exist), strategic outline stage, outline business case, full business case | ||

| If yes, have we seen / been given access to the Business Case? | N/A (doesn’t exist), Not been given access, given access but not reviewed for this analysis | ||

| Is the project being evaluated / planned to be evaluated on its own or as part of a portfolio of projects? | N/A (no plans to evaluate), single project evaluation, portfolio evaluation | ||

| If a portfolio evaluation will be applied, are all of the projects within it in the GMPP? | Yes / No | ||

| Please add here any comments you may have on the appropriateness of the portfolio evaluation approach | Open-ended | Please reflect on how the contextual information in this section may affect the assessment of the following sections (e.g., methods) and expectations for evaluation planning with reference to relevant frameworks (e.g., the BEIS and DfT frameworks for evaluation planning by business case stage) | |

| Criteria for scoring | Values | Benchmark | |

| 1 | Aims and research questions | ||

| 1.1 | Are the aims, objectives, and rationale for the evaluation clear? | 0/1/2 | This section should explain: a) rationale b) aims c) objectives |

| 1.2 | Are research questions clearly formulated? | 0/1/2 | Research questions are formulated in line with the evaluation’s aims and objectives. |

| 1.3 | Is the application of the evaluation clear? | 0/1/2 | Explanation of one or more of the below types of applications or uses are discussed: Improvement/expansion/funding decisions/accountability & transparency/ Type of decisions to inform and by whom |

| 1.4 | Is there a clear conceptual framework? | 0/1/2 | A clear conceptual framework, depending on the context of the evaluation, could be a theory of change, and this could have the following: a) logic model elements (inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes and impacts) b) assumptions c) consideration of context and alternative explanations d) clear links highlighting a causal chain Alternative frameworks could be more relevant depending on the specific case. For example, benefit maps in the context of benefit management should be assessed against the relevant IPA guidance. For the relevant IPA guidance see: Cabinet Office (2017) - Guide for effective benefits management in major projects |

| 1.5 | Is the target audience of the evaluation clear? | 0/1/2 | There is a reference to a list of stakeholders for the evaluation findings, including decision makers for the project/programme. |

| Reviewer’s additional comments on the clarity of scope and design | Open-ended | Explain if any shortcomings in this section are due to the specific context of the evaluation. For example, it may be that there are long-time horizons, or the project is at a very early stage of design | |

| 2 | Design and methods | ||

| 2.1 | Is the research design consistent with the evaluation aims and purpose? | 0/1/2 | A research design is consistent if the research questions align with the evaluation aims and purpose and the approach is fit for purpose. |

| 2.2 | Is the evaluation approach consistent with the aims, objectives and research questions? | 0/1/2 | There is an explicit rationale for choosing one of more approaches, namely, process evaluation, impact evaluation, and economic evaluation. Also, it should be briefly discussed if any of them was not chosen. |

| 2.3 | Is the evaluation scope proportional? | 0/1/2 | There should be a brief discussion on proportionality. |

| 2.4 | Is there a process evaluation in place? | No scoring | Yes/No |

| 2.5 | If there is no process evaluation, explain why | No scoring | Open-ended. Explain if there is enough evidence to suggest there could or should have been a process evaluation. |

| 2.6 | If there is a process evaluation, how robust is the design? | NA/0/1/2 | NA - if no process evaluation and this is appropriate. 0 - if no process evaluation and there should be. 1/2 - If there is a process evaluation, as a minimum there should be an explanation on its aims, evaluation criteria and evidence to answer the research questions |

| 2.7 | Is there an impact evaluation in place? | No scoring | Yes/No |

| 2.8 | If there is no impact evaluation, explain why | No scoring | Open-ended. Explain if there is enough evidence to suggest there could and should have been an impact evaluation. |

| 2.9 | If there is an impact evaluation, how robust is the design? | NA/0/1/2 | NA - if no impact evaluation and this is appropriate 0 - if no impact evaluation and there should be 1/2 - If there is an impact evaluation, as a minimum there should be an explanation on the most feasible approach and the choices made. Potential approaches are theory-based, experimental and quasi-experimental and should be robust and proportionate to the context of the project |

| 2.10 | Is there a value-for-money evaluation in place? | No scoring | Yes/No |

| 2.11 | If there is no value-for-money evaluation, explain why | No scoring | Open-ended. Explain if there is enough evidence to suggest there could and should have been a value-for-money evaluation. |

| 2.12 | If there is a value-for-money evaluation, how robust is the design? | NA/0/1/2 | NA - if no value-for-money evaluation and this is appropriate 0 - if no value-for-money and there should be 1/2 - If there is a value-for-money evaluation, as a minimum there should be an explanation on the most feasible approach, the choices made, costs and benefits, and valuation methods. Potential approaches include CBA or CEA (depending on feasibility) For additional reference to value-for-money see: NAO (2023) - Successful commissioning toolkit: Assessing value for money |

| 2.13 | Is the data collection methodology clearly explained? | 0/1/2 | Depending on the method, are the choices of data collection activities sufficient to answer the research questions? If qualitative: focus groups, interviews, workshops, other If quantitative: administrative data, secondary data, surveys, other |