Health matters: obesity and the food environment

Published 31 March 2017

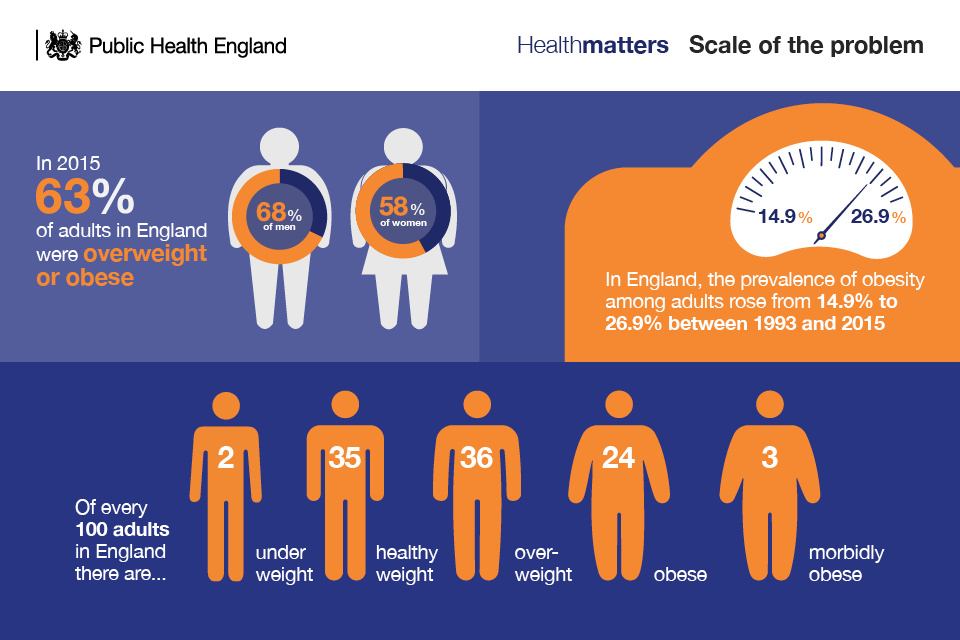

Scale of the obesity problem

Nearly two-thirds of adults (63%) in England were classed as being overweight (a body mass index of over 25) or obese (a BMI of over 30) in 2015.

In England, the proportion who were categorised as obese increased from 13.2% of men in 1993 to 26.9% in 2015 and from 16.4% of women in 1993 to 26.8% in 2015. The rate of increase has slowed down since 2001, although the trend is still upwards.

The prevalence of obesity is similar among men and women, but men are more likely to be overweight.

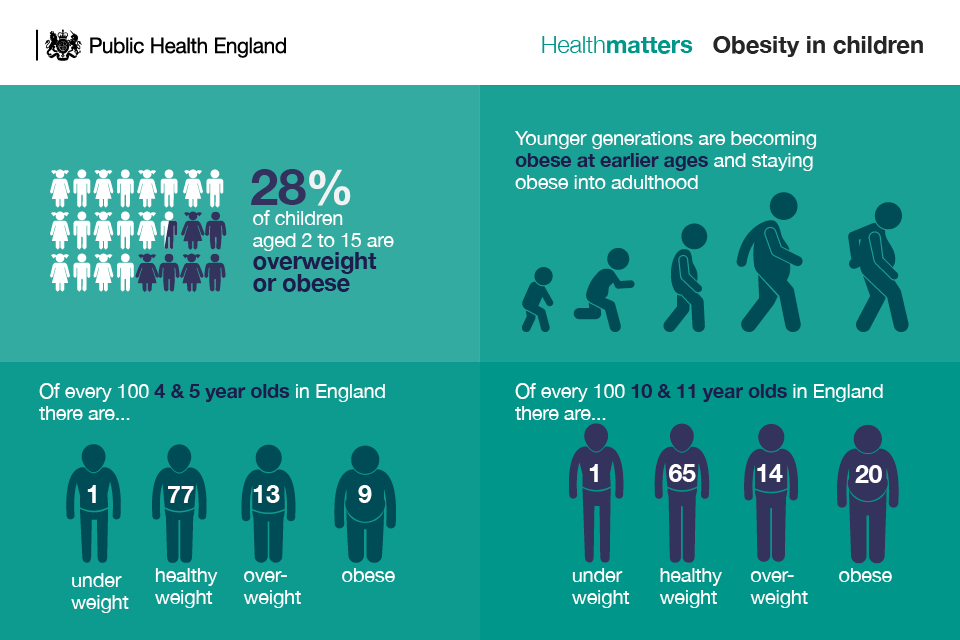

In 2015 to 2016, 19.8% of children aged 10 to 11 were obese and a further 14.3% were overweight. Of children aged 4 to 5, 9.3% were obese and another 12.8% were overweight. This means a third of 10 to 11 year olds and over a fifth of 4 to 5 year olds were overweight or obese.

In summary, nearly a third of children aged 2 to 15 are overweight or obese and younger generations are becoming obese at earlier ages and staying obese for longer.

It is estimated that obesity is responsible for more than 30,000 deaths each year. On average, obesity deprives an individual of an extra 9 years of life, preventing many individuals from reaching retirement age. In the future, obesity could overtake tobacco smoking as the biggest cause of preventable death.

Obesity increases the risk of developing a whole host of diseases. Obese people are:

- at increased risk of certain cancers, including being 3 times more likely to develop colon cancer

- more than 2.5 times more likely to develop high blood pressure - a risk factor for heart disease

- 5 times more likely to develop type 2 diabetes

Reducing obesity, particularly among children, is one of the priorities of Public Health England (PHE). PHE aims to increase the proportion of children leaving primary school with a healthy weight, as well as reductions in levels of excess weight in adults.

PHE is working to significantly reduce childhood obesity, contributing to the delivery of the government’s Childhood Obesity Plan.

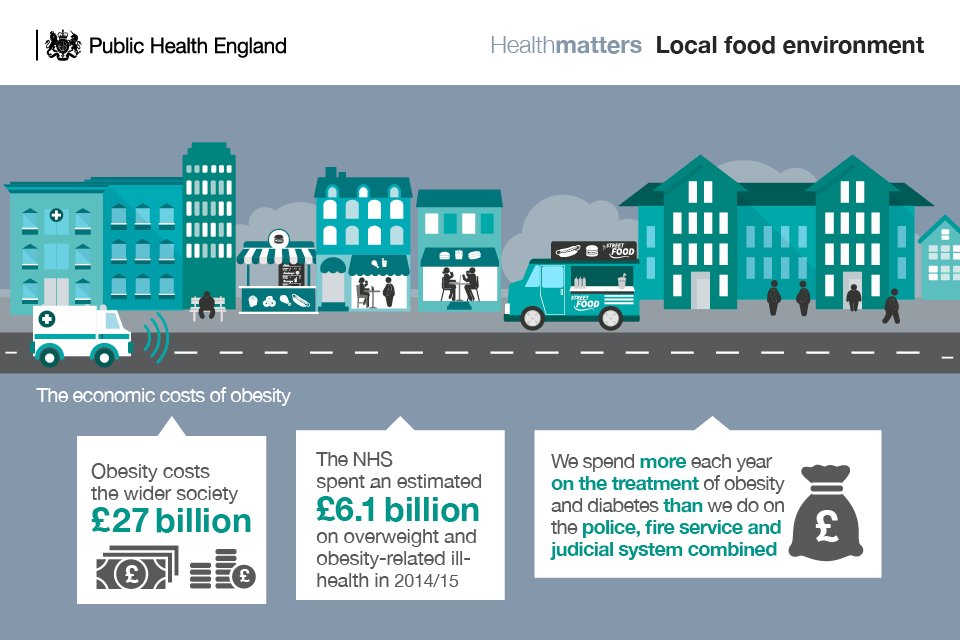

The costs of obesity

Failing to address the challenge posed by the obesity epidemic will place an even greater burden on NHS resources. It is estimated that the NHS spent £6.1 billion on overweight and obesity-related ill-health in 2014 to 2015.

Annual spend on the treatment of obesity and diabetes is greater than the amount spent on the police, the fire service and the judicial system combined.

Obesity can harm people’s prospects in life, their self-esteem and their underlying mental health. Research published in the BMJ found that people who are obese or overweight are less likely to exercise in public as they feel discriminated against because of their weight.

More broadly, obesity has a serious impact on economic development. The overall cost of obesity to wider society is estimated at £27 billion.

The UK-wide NHS costs attributable to overweight and obesity are projected to reach £9.7 billion by 2050, with wider costs to society estimated to reach £49.9 billion per year.

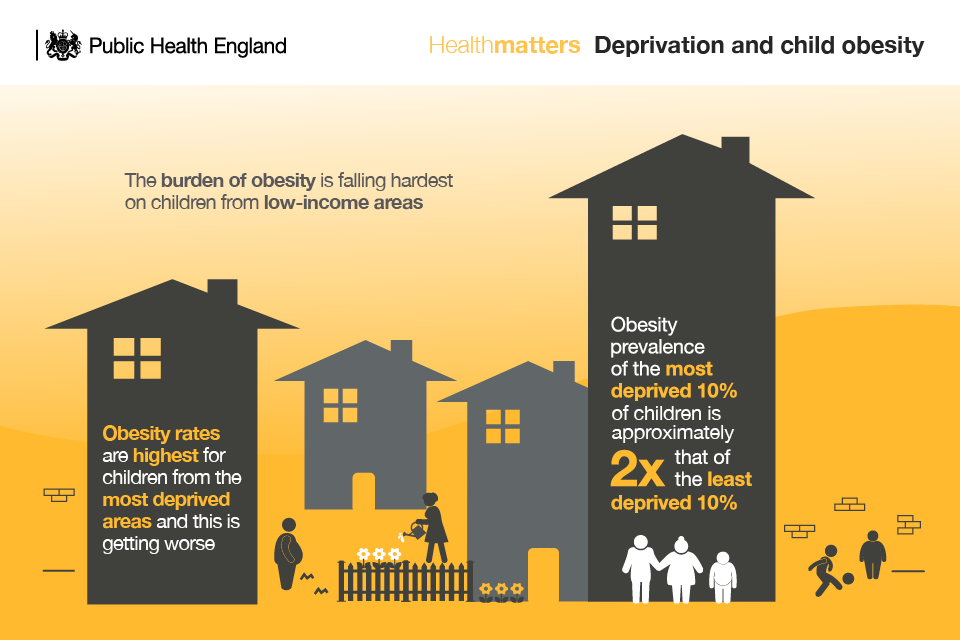

Obesity and health inequalities

No one is ‘immune’ to obesity, but some people are more likely to become overweight or obese than others. The Marmot review highlights that income, social deprivation and ethnicity have an important impact on the likelihood of becoming obese.

There is a strong relationship between deprivation and childhood obesity. Analysis of data from the National Child Measurement Programme (NCMP) shows that obesity prevalence among children in both Reception and Year 6 increases with increased socioeconomic deprivation (measured, for example, by the 2010 Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score). Obesity prevalence in the most deprived 10% of children is approximately twice that of the least deprived 10%.

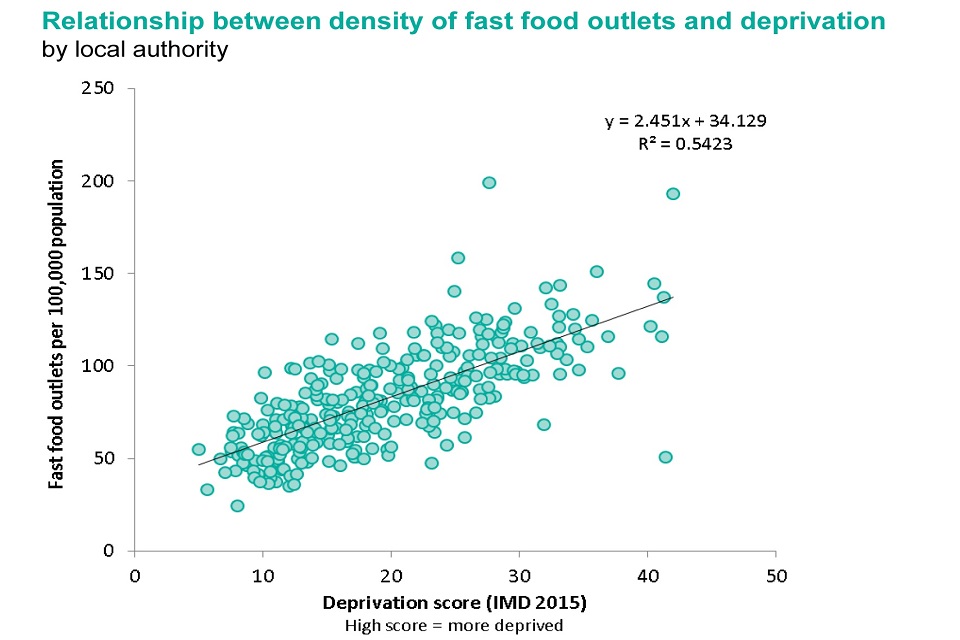

On average, there are more fast food outlets in deprived areas than in more affluent areas.

People from certain ethnic groups, such as south Asians, are more likely to be overweight and obese, and have a higher susceptibility to particular diseases linked to excess weight, such as type 2 diabetes.

Factors behind the rise in obesity levels

Obesity is a complex problem with many drivers, including:

- behaviour

- environment

- genetics

- culture

The main risk factors for obesity are:

1.The food and drink environment

The PHE Eatwell Guide provides a compelling evidence base for eating a healthy diet, and ignoring this advice increases the chances of becoming obese.

But many people still find it difficult to eat healthily. This is primarily because we are living in an obesogenic environment where less than healthier choices are the default, which encourage excess weight gain and obesity.

The Foresight report states that while achieving and maintaining calorie balance is a consequence of individual decisions about diet and activity, our environment, and particularly the availability of calorie-rich food, now makes it much harder for individuals to maintain healthier lifestyles.

The increasing consumption of out-of-home meals – that are often cheap and readily available at all times of the day - has been identified as an important factors contributing to rising levels of obesity.

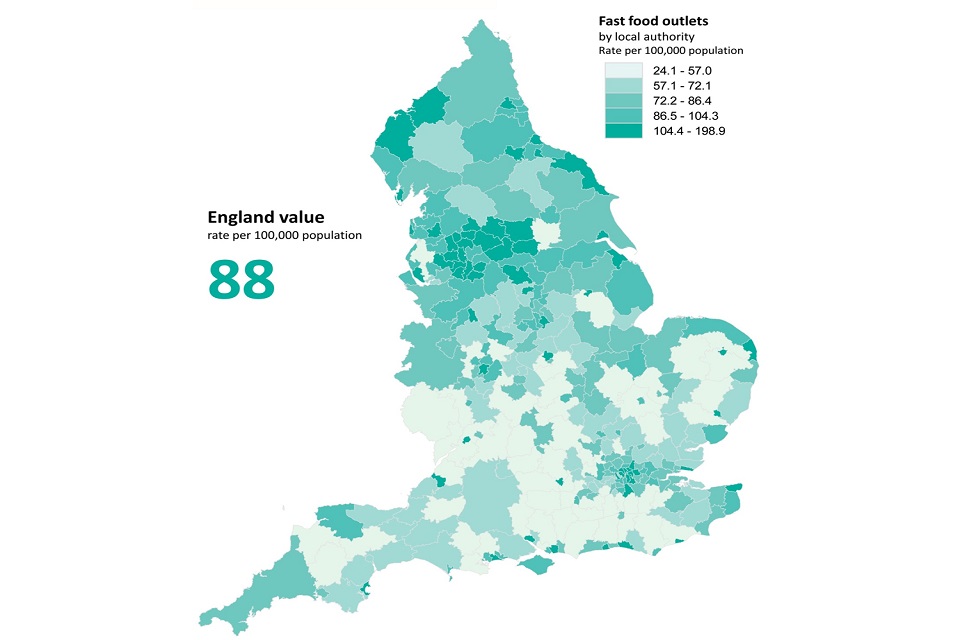

PHE estimated in 2014 that there were over 50,000 fast food and takeaway outlets, fast food delivery services, and fish and chip shops in England.

More than one quarter (27.1%) of adults and one fifth of children eat food from out-of-home food outlets at least once a week. These meals tend to be associated with higher energy intake; higher levels of fat, saturated fats, sugar, and salt, and lower levels of micronutrients.

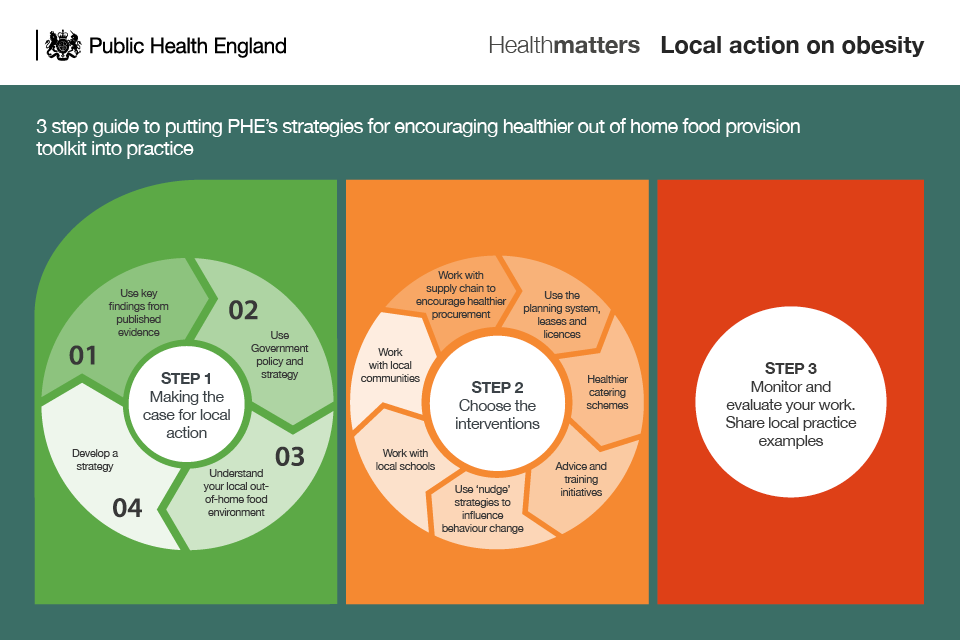

This edition of Health Matters focuses specifically on what can be done to improve the food environment in which we live through the use of PHE’s Strategies for encouraging healthier ‘out of home’ food provision toolkit.

2.Physical inactivity

Put simply, we are not burning off enough of the calories that we consume. People in the UK are around 20% less active now than in the 1960s. If current trends continue, we will be 35% less active by 2030.

We are the first generation to need to make a conscious decision to build physical activity into our daily lives. Fewer of us have manual jobs. Technology dominates at home and at work, the 2 places where we spend most of our time. Societal changes have designed physical activity out of our lives.

Figures from the Health Survey for England show that 67% of men and 55% of women aged 16 and over do at least 150 minutes of moderate physical activity per week.

Only 22% of children aged between 5 and 15 met the physical activity guidelines of being at least moderately active for at least 60 minutes every day (23% of boys, 20% of girls).

Read the Health matters edition on physical activity for more advice on embedding physical activity into everyday life.

PHE’s plan to tackle obesity includes looking at behaviour change relating to healthier eating and increasing physical activity as part of a whole systems approach.

Improving everyone’s access to healthier food choices

The PHE toolkit, ‘Strategies for encouraging healthier “out of home” food provision’ has been developed to encourage local intervention that will further increase the opportunities for communities to access healthier food whilst out and about in their local community. It outlines opportunities both to manage new business applications and to work with existing food outlets to provide healthier food.

The toolkit has been created to help local authorities across England work with smaller food outlets such as:

- takeaways

- restaurants

- bakers

- sandwich and coffee shops

- mobile traders

- market stalls

- corner shops

- leisure centres

- children’s centres and private nurseries

Understanding barriers to change

Understanding the limitations to offering healthier food and drinks is vital to the development of healthier interventions. For example, food outlets in low income areas can face particular barriers to offering healthier food and drink choices, such as highly competitive, price-sensitive markets, and a real or perceived lack of demand for healthier food and drink.

Smaller outlets often struggle to be profitable and many aspects of low-income neighbourhoods make change difficult. A study by London Metropolitan University of fast food outlets in deprived areas found that barriers to change included:

- limited menus with little scope for healthier changes

- lack of space and the right equipment, or skills and resources to prepare or cook healthier options

- a fear that fresh fruit and vegetables would be wasted and lose the outlets money

- the higher cost of healthier options. (some suppliers charge more for healthier products and additional costs cannot be passed on to the customer)

- the lack of availability of healthier options in appropriate sizes for small outlets, that may only need small quantities

- a fear that some changes, such as reducing salt, would affect the taste and deter customers

- a reluctance to change popular recipes or traditional ethnic cuisines

- supporting business to offer healthier food and drink

Healthier catering can save businesses money. Strategies for encouraging outlet participation should emphasise that changes that are cost neutral may save the outlet money or attract new customers. For example, by providing smaller portions, using less oil, or promoting healthier products.

How local authorities can help businesses offer healthier food and drink

An increasing number of local councils have developed healthier catering initiatives in recent years. These are generally led and managed by staff from environmental health or trading standards teams who are able to build on their established relationships with local outlets.

The initiatives encourage outlets to switch to healthier ingredients, menus and cooking practices. They focus particularly on reductions in salt, fat and sugar, smaller portions, and inclusion of more fruit and vegetables and the provision of calorie information.

They frequently draw on behavioural economics, encouraging consumers to make healthier choices through, for example, promoting the sale of food in smaller containers or the placing of healthier drinks at eye level.

Schemes can be classified depending on:

- the types of outlet targeted, for example by food type or outlet type or single/small chain

- whether or not an award is offered

- whether the scheme is targeted at a specific geographical area or across the whole local authority

PHE’s healthier catering guidance for different types of businesses supports the toolkit and provides tips on providing and promoting healthier food and drink for children and families.

Using planning policies to tackle obesity

Planning policies can be used by councils to help promote healthier food and drink choices. The PHE toolkit outlines a number of suggestions for planning teams to create a healthier food environment such as:

- ensuring shops and markets that sell a diverse food offer are easy to reach by walking, cycling or public transport

- requiring leisure centres, workplaces, schools and hospitals with catering facilities and/or vending machines to have a healthier food offer for staff, students, and/or customers

- ensuring development avoids over-concentration of hot food takeaways in existing town centres or high streets, and restricts their proximity to schools or other facilities for children and young people and families

Restricting the opening of new hot food takeaway outlets

Planning documents and policies to control the over-concentration and proliferation of hot food takeaways should form part of an overall plan for tackling obesity and should involve a range of different local authority departments and stakeholders.

Once appropriate planning policies are in place, supported by local evidence, local councils can refuse planning permission for a new food outlet if they can demonstrate that:

- it will have an adverse impact on the health and wellbeing of the local population

- will undermine the local authority’s strategy to tackle obesity

NICE’s pathway on tackling obesity through working with local communities calls for empowering local authorities to influence planning permission for food retail outlets in relation to preventing and reducing obesity.

To achieve this, the following are among the measures that should be considered:

- encourage local planning authorities to restrict planning permission for takeaways and other food retail outlets in specific areas, such as within walking distance of schools

- review and amend ‘classes of use’ orders for England to address disease prevention via the concentration of outlets in a given area

An increasing number of local councils have developed Supplementary Planning Documents (SPDs) to restrict the opening of new hot food takeaways close to schools, leisure centres, or other places frequented by children. It is up to each local council to develop an approach that, according to existing evidence, is likely to be appropriate and effective.

For planning decisions to be successfully upheld they need to be able to demonstrate a link to sound evidence and clear local policy. In particular there needs to be good linkage between any SPDs or neighbourhood planning policies, health strategies (Health and Wellbeing strategy and the Joint Strategic Needs Assessment) and, most importantly, the Local Plan. Local plans need to refer to these health strategies and vice versa.

Restricting the proliferation of new fast food outlets benefits the whole community by:

- reducing the amount of litter in the area

- cutting down on discarded food waste and litter, which can stop foraging animals and pests

- improving the visual appeal of the local environment and reducing night-time noise

- reducing traffic congestion caused by short-term car parking outside takeaways

- improving access to healthier food in deprived communities, which may contribute to reducing health inequalities

Working with schools

Children need a healthy balanced diet to support growth and development, and the school environment can have a powerful influence on their eating habits. Children eat at least 1 and sometimes more meals there each day. For some, a school lunch is their main meal, providing a critical nutritional safety net.

With a significant proportion of secondary, and even some primary age pupils, choosing to purchase food from nearby outlets, the food environment around schools has an important role to play in encouraging children and young people to eat a healthy diet.

The PHE toolkit outlines the role schools can play in encouraging healthier eating. Schools can adopt a number of policies to encourage pupils to purchase their lunch from the school canteen. These include:

- consulting with children on the food offer and school canteen via school nutrition action groups

- making the canteen environment more attractive by use of, for example, shorter lunch queues, music and improved décor

- adopting cashless systems to speed up food service and remove the need for pupils to be given cash that might be spent outside school on less healthy alternatives

- closed gate or onsite policies

- offering meal deals, subsidised or free school meals

- getting pupils, as part of the curriculum, to analyse local food outlet offers and develop and trial healthier, tastier food options, which can encourage change in choices

National policies to tackle obesity

A soft drinks industry levy

The government’s childhood obesity plan outlined plans for a soft drinks industry levy across the UK. Sugary soft drinks provide 26% of the total sugar intakes for 11 to 18 year olds in England, according to the National Diet and Nutrition Survey. The Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) recently concluded that sugar consumption increases the risk of consuming too many calories. A single 330ml can of a soft drink with added sugar (which can contain as much as 35g of sugar), may instantly take a child over their maximum recommended daily intake of sugar.

In England, the revenue from the levy will be invested in programmes to reduce obesity and encourage physical activity and balanced diets for school age children.

Sugar reduction

Evidence shows that slowly changing the balance of ingredients in everyday products, or making changes to product size, is a successful way of improving diets. This is because the changes are universal and do not rely on individual behaviour change.

A broad, structured sugar reduction programme is being led by PHE to remove sugar from the products children eat most. All sectors of the food and drinks industry will be challenged to reduce overall sugar, across a range of products that contribute to children’s sugar intakes, by at least 20% by 2020, including a 5% reduction in year 1.

This programme will apply to all sectors of industry (retailers, manufacturers and the out-of -home sector) and to all foods and drinks that contribute to children’s sugar intakes, including those aimed at very young children.

The programme will initially focus on the nine categories of family everyday foods that make the largest contributions to children’s sugar intakes:

- breakfast cereals

- yoghurts

- biscuits

- cakes

- confectionery

- morning goods eg croissants, muffins, crumpets, pastries

- puddings

- ice cream

- sweet spreads, toppings, sauces

PHE’s marketing campaigns

PHE has a number of national marketing campaigns that can be used at a local level to encourage people to improve their lifestyle behaviours. Downloadable content is available from the PHE campaign centre.

Change4Life has advice on how to reduce the amount of sugar that children consume, as well as the free Be Food Smart app which can be used to find out how much sugar, saturated fat and salt is in food and drink.

PHE’s One You campaign is aimed at adults, aged 40 to 60, and contains advice on healthy eating including recipes, an alcohol checker to monitor alcohol consumption, and tips for encouraging physical activity.

Call to action

Influencing the food environment so that healthier options are accessible, available and affordable can only be accomplished through a collaborative approach, with effective partnerships and co-ordinated action at a local level across the public, private and voluntary sectors, with councils taking this forward through their leadership.

Local authorities

Establish strategic partnerships across relevant local council departments (for example, planning, economic development and public health), and work with local partners such as schools, the community and the supply chain as part of a whole systems approach.

Identify local needs (for example, through mapping levels of obesity, deprivation and location or density of fast food outlets) to support targeting. PHE has data on obesity and tools to help support this.

Encourage a cost neutral approach for small food business with small gradual changes less likely to be noticed by customers. Offer incentives such as free training on food hygiene or nutrition.

Involve local communities, working with practitioners, in initiatives designed to help local outlets create a healthier food offer to raise awareness of the importance of healthier eating habits, and help increase the pressure on outlets to make changes.

Small food businesses

Should work with the supply chain to encourage healthier procurement, which could be through LA Healthier Catering Schemes or Awards.

Look at structural changes to achieve sustained behavioural change. These could include reducing the price of healthier foods, increasing the availability of healthier options, reducing pack size, portion control and calorie labelling on menus.

Businesses should signpost customers to healthier options with less salt, saturated fat, sugar and calories on menus.

Schools

Schools can focus initiatives, through a whole school approach, to improve pupils’ eating habits on both the ‘in-school’ and ‘out of school’ food environment.

They should look at policies to encourage pupils to purchase their lunch from the school canteen, including via consulting with children on the food offer and the school canteen.

Town planners

Supported by local evidence, and working alongside public health teams, town planners can develop planning documents and policies to support the creation of healthy environments promoting opportunities for the production and consumption of healthier food, and restricting the proliferation of hot food takeaways.

Look for the win wins such as limiting takeaways may help with reducing the amount of litter in improve the visual appeal of the local environment.

The local council, using its leasing and licensing powers, can influence the provision of healthier food in outlets operating from sites it owns or controls.

Health professionals

Health professionals, including pharmacists, nurses and GPs, should feel confident discussing nutrition and weight issues with children, their families and adults. They can advise on the importance of following a healthy, balanced diet in line with recommendations outlined in the PHE Eatwell Guide.

Health Education England (HEE) and PHE have launched a suite of resources aimed at supporting the health care and wider workforce in ‘Making Every Contact Count’.

Where appropriate, health professionals should refer people to local weight management services, clubs and websites, if they ask for more advice.

Resources

Case study: Box Chicken – providing healthy competition to fast food outlets

Case study: planning document to limit the proliferation of takeaways