Health matters: reproductive health and pregnancy planning

Published 26 June 2018

Summary

This professional resource focuses on reproductive choice and ensuring that pregnancy, if desired, occurs at the right time and when health is optimised. Effective contraception and planning for pregnancy means that women and men stay healthy throughout life and take steps to improve the health of the baby they might have some time in the future.

The importance of reproductive health

Ensuring that women and men achieve and maintain good health in their reproductive years is a public health challenge that impacts on future health for both themselves and their child. Therefore, reproductive health should be about improving the general health of the whole population through increasing knowledge of healthy lifestyles, which should be an underlying philosophy of all health, education, and social care.

Life-course approach

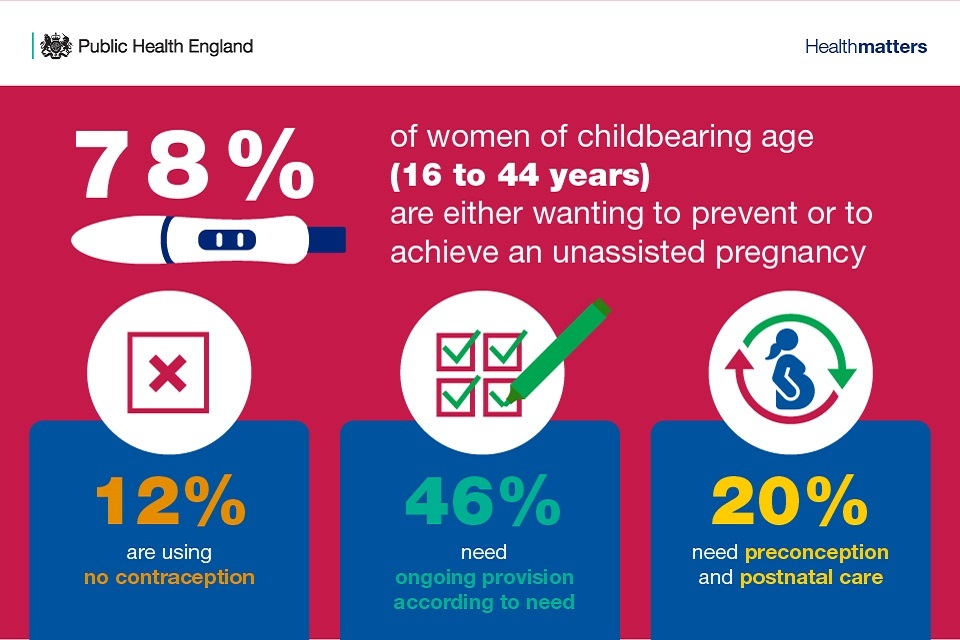

Women make up 51% of England’s population. Of these, more than three quarters at any one time want to either prevent or achieve pregnancy. Contraception and preconception care are therefore a day-to-day reality for the vast majority of women for most of their reproductive years. As such, they should be considered as 2 sides of the same coin, rather than preconception care only being considered at the time of trying to conceive.

It is crucial that women have a choice and control over reproduction in order to ensure that as many pregnancies as possible are planned and wanted, health is optimised both before a first pregnancy and in the inter-pregnancy period, and women who do not wish to have children can effectively prevent becoming pregnant.

Protecting health in infancy and supporting the transition to parenthood is vital, as what happens in pregnancy and early childhood impacts on physical and emotional health all the way through to adulthood. This previous edition of Health Matters on ‘giving every child the best start in life’ provides detailed information on this.

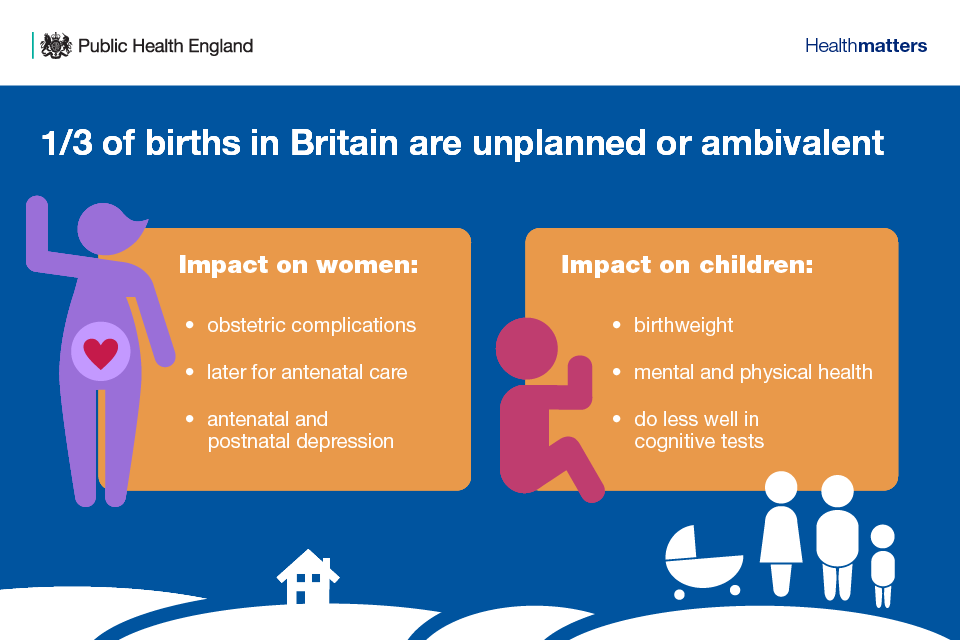

Pregnancy planning

A planned pregnancy is likely to be a healthier one, as unplanned pregnancies represent a missed opportunity to optimise pre-pregnancy health. Currently, 45% of pregnancies and one third of births in England are unplanned or associated with feelings of ambivalence. Although pregnancies continuing to term mostly lead to positive outcomes, some unplanned pregnancies can have adverse health impacts for mother, baby and children into later in life.

Infographic showing the impact of unplanned births in Britain

Traditionally, preconception care has focused on women planning a pregnancy. However, as many pregnancies are unintended at the time of conception, the timing of addressing preconception risks poses a challenge. Additionally, many women of childbearing age do not seek preconception care for themselves until they are pregnant.

Supporting people to develop healthy relationships and prevent unplanned pregnancy is vital for enabling them to fulfil their aspirations and potential, and for their emotional wellbeing.

Professor Judith Stephenson, Institute for Women’s Health, outlines why pregnancy planning is important.

Risk factors for unplanned pregnancy

There are multiple risk factors for unplanned pregnancy, including:

- lower educational attainment

- younger age

- smoking

- substance misuse

Abortion rates are higher amongst some BAME groups, which may indicate either higher rates of total unplanned pregnancies or greater proportions that culminate in abortion.

Unplanned pregnancy is also an issue for women who are over the age of 35, and right through to menopause. This group are the least likely to be using adequate contraception, despite being sexually active and not wanting to conceive. Rising rates of abortion in this age group support this finding.

Teenage pregnancy

In 2016, the under-18 conception rate in England was 18.8 conceptions per thousand women aged 15 to 17, which was the lowest rate recorded since comparable statistics were first produced in 1969. Despite the declining number of teenage pregnancies, teenagers remain the group at highest risk of unplanned pregnancy.

Outcomes for young parents and their children are still disproportionately poor, contributing to inter-generational inequity with higher rates of infant mortality, low birthweight and poor maternal mental health, amongst other adverse outcomes.

Experience of a previous pregnancy is a risk factor for young women under the age of 18 becoming pregnant again. 12% of births among young women under the age of 20 occur in women who are already mothers.

Addressing teenage pregnancy can save money, with £4 saved in welfare costs for every £1 spent. Furthermore, every young mother who returns to Education, Employment & Training (EET) saves agencies £4,500 a year and for every child prevented from going into care, social services would save on average £65,000 a year.

Contraception

In 2013, there were 11,697,000 women of reproductive age in Britain.

Contraception is important for all heterosexual women of reproductive age, regardless of whether they are planning a pregnancy, as it enables them to effectively control if and when they desire to conceive. If pregnancy is the ultimate wanted outcome, contraception provides a longer opportunity to address health issues in advance of the pregnancy, leading to better health outcomes for both mother and child.

At any one time, 78% of heterosexual women require support to achieve or prevent a pregnancy, and therefore contraception is an effective population approach to meet these needs.

Infographic showing 785 of women of childbearing age wanting to prevent or achieve a pregnancy

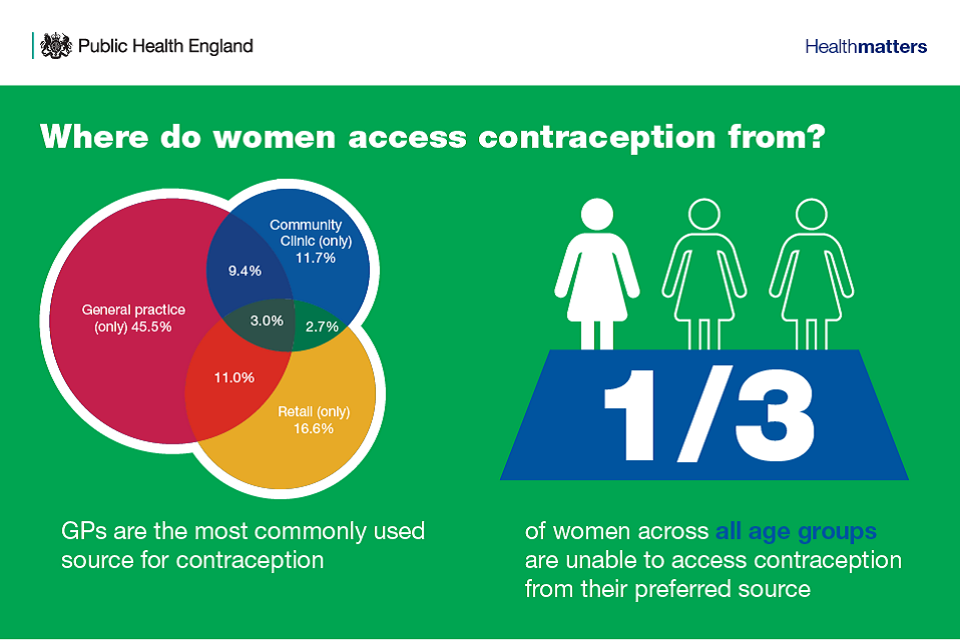

Women access contraception from a range of sources, with preference for source and method of contraception varying by both age and deprivation. Whilst GPs are the most popular source used by 6 out of 10 women, sexual health clinics and community clinics are also commonly used, particularly by younger and more disadvantaged populations.

Women should be offered a full range of choices in all settings so that they can choose a method of contraception that suits them best. However, not all methods are always available in all settings.

Infographic showing where women access contraception from

However, one third of women are unable to access contraception from their preferred source, and women who are already disadvantaged are less likely to access contraception and preconception care altogether.

Women who are not reached by existing contraceptive services are ideally placed to receive opportunistic contraceptive advice, such as after taking emergency hormonal contraception (EHC), after having an abortion or a baby, or when they are in contact with health services for other issues or conditions.

Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), including implants, intrauterine devices (IUDs), intrauterine system (IUS) and the contraceptive injection, are the most effective methods of contraception. However, uptake varies by deprivation as they are not always equally available, and prescription by GPs has changed in the last 10 years.

Between 2014 and 2016, rates of GP-prescribed LARC decreased by 11%, and the overall rate of LARC use has decreased by 3% a year since 2014. However, rates of LARC (excluding injections) prescribed by Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) Services remained relatively constant between 2014 and 2016.

Dr Asha Kasliwal, President FSRH, outlines what should be done to enable reproductive choice and optimise pregnancy planning.

Preconception health and care

Preconception health

Preconception health – the health of both men and women before conception – is important not only for pregnancy outcomes but also for the lifelong health of their children and even the next generation. There is mounting evidence of the inter-generational impacts of poor maternal and pregnancy health leading to higher risk of non-communicable disease in the future.

The preconception period can be seen in 3 different ways:

- from the biological standpoint as the days and weeks before embryo development

- from the individual perspective as the time of wanting to conceive

- through a population lens as any time a woman is of childbearing age

This means that preconception care is relevant for the population and individuals who may conceive at some point in the future, as well as for the period when a pregnancy is actively being considered.

Professor Judith Stephenson, UCL Institute for Women’s Health, specifies the targets for reproductive health and pregnancy planning.

Preconception care

The World Health Organisation highlights that preconception care improves the health of women and men while reducing the chances that their child will be born prematurely, have low birth weight, birth defects or other birth-related conditions that could hinder optimal child development.

The preconception period presents an opportunity for intervention when women and men can adopt healthier behaviours in preparation for a successful pregnancy and positive health outcomes for both themselves and their child.

This includes:

- ensuring you are up to date with all vaccinations

- ensuring sexual health checks and cervical screening are up to date

- taking vitamin D and folic acid supplements

- eating a healthy balanced diet and undertaking regular moderate intensity physical activity

- reducing alcohol consumption

- giving up smoking

- using contraception for family spacing

As well as allowing physical and mental health conditions and social needs to be addressed and managed prior to pregnancy, preconception health is important because:

- it allows women to be aware of potential risks and make an informed decision about their pregnancy

- many potentially modifiable risk factors which influence pregnancy outcome are present before conception, meaning prenatal care is often given too late to change the pregnancy outcome

However, only a minority of future parents make changes in preparation for pregnancy and most only start thinking about preconception care once pregnant.

Women seldom disclose that they are planning to become pregnant to health professionals, despite frequently coming into contact with services for related reasons, such as attending a community contraceptive service, buying a pregnancy test from a community pharmacy, or visiting their GP or early pregnancy unit after miscarriage. These present ideal opportunities for preconception health interventions, but are frequently missed.

Preconception care is a way of supporting women and men to adopt healthy behaviours across the reproductive life-course, through aligning local services to provide universal support for everyone, as well as the targeted support where it is most needed. It should be person-centred and holistic, which requires coordinated, collaborative commissioning within local maternity systems, across primary care, and more broadly within sustainability and transformation partnerships (STPs). It is also about ensuring that services can take a forward view to promote healthy behaviours and support early interventions to manage emerging risks across the life-course, prior to first pregnancy, and then looking ahead to the next pregnancy and beyond.

Fertility and preconception care should also be taken into account and prioritised at the individual level, by both women and men, especially if conceiving is the desired outcome. Leading a healthy lifestyle and having a healthy household is part of this, and is also important for the success of the pregnancy, and the health and happiness of the child once they are born and grow up.

Dr Asha Kasliwal, President FSRH, describes the role of partners in reproductive health and pregnancy planning.

Folic acid

Women who are trying to conceive should be advised to take 400 micrograms of folic acid each day. This can help to prevent birth defects known as neural tube defects, including spina bifida.

However, only one fifth of women report taking folic acid before pregnancy, which rises to three fifths of women once their pregnancy is confirmed.

Preconception care varies according to multiple factors, which can be exemplified by the differences in folic acid uptake across different demographics:

- age – one tenth of women aged 20-24 report taking folic acid compared to over a quarter of women aged over 45 years

- ethnicity – 20% of white British women report taking folic acid prior to becoming pregnant compared to 10% of black British and 15% in Asian British groups

- deprivation – 10% of women in the most deprived decile report taking folic acid compared to 26% in the least deprived decile

Maternal and paternal obesity

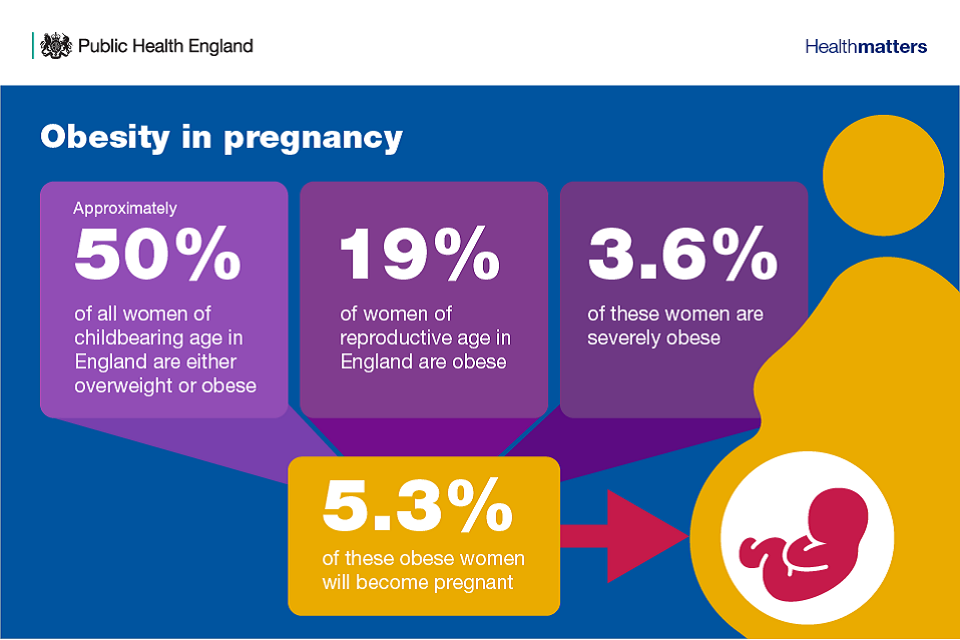

Addressing the issue of healthy eating and obesity is one of the commonest challenges during the preconception period that has far reaching impacts. Links between both maternal and paternal diet and weight have been associated with fertility and intergenerational impacts on offspring.

Achieving weight loss requires a longer period of time to address adequately before pregnancy, and is therefore an area where changes could be made earlier than the traditional preconception period of 3 months.

Rates of obesity are increasing among women of reproductive age and an increasing number of women who become pregnant are obese - 19% of women of reproductive age in England are obese, 3.6% are severely obese, and of these obese women 5.3% will become pregnant each year.

Infographic on obesity in pregnancy

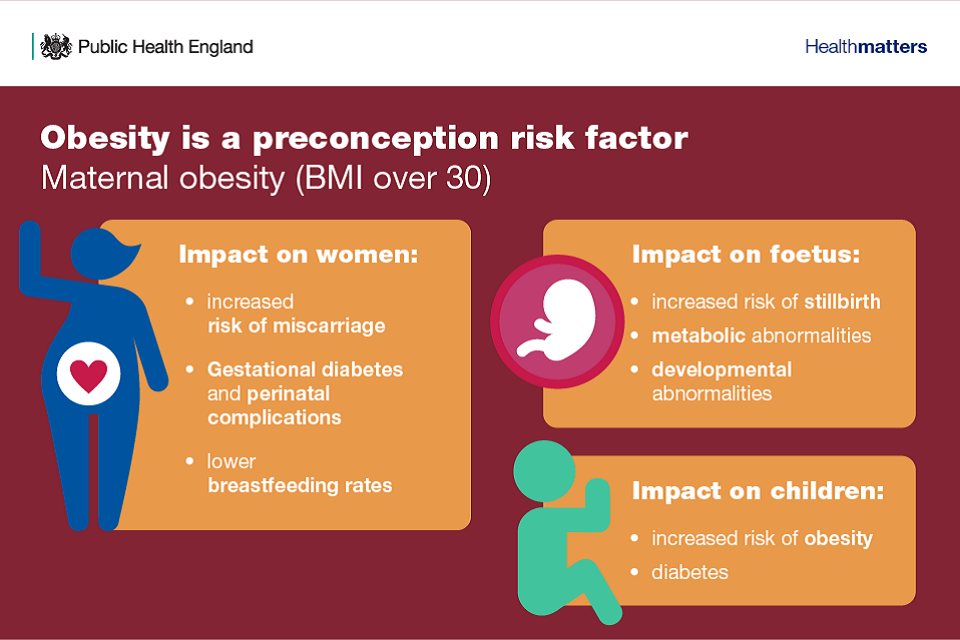

Obesity is a significant preconception risk factor and is associated with increased risk of many major adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes.

Maternal obesity is one of several influences that appear to underlie the foetal or preconception origins of later risk of non-communicable diseases, such as Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, asthma and endometrial cancer.

Infographic showing obesity is a preconception risk factor

As shown by an analysis in the UK, many women of reproductive age in low, middle, and high-income countries will also not be nutritionally prepared for pregnancy, as they are not meeting even the lower reference nutrient intake amounts.

The global increase in male obesity (increased from 3% in 1975 to 11% in 2014) is also relevant, as paternal obesity has been linked to impaired fertility by affecting sperm quality and quantity. It is also associated with increased chronic disease risk in offspring.

Professor Judith Stephenson, UCL Institute for Women’s Health, outlines the important role of local authorities and commissioners in making reproductive health part of day to day services .

Quitting smoking

Encouraging women to stop smoking before having a baby benefits both mother and child, and may also help them stop smoking for good. Smoking in pregnancy is associated with poor foetal growth and low birthweight, and with obesity in childhood.

Smoking can also cause fertility problems in men, as it can:

- reduce the quality of sperm

- cause a lower sperm count

- affect the sperm’s ability to swim

- cause male sexual impotence

However, as stopping smoking can reverse the damage, male partners who smoke should also be encouraged to quit to help improve their fertility and to reduce exposure to second-hand smoke.

Infographic on smoking in pregnancy

Cutting out alcohol consumption

Updated guidelines from the UK Chief Medical Officers state that, for women who are pregnant or planning a pregnancy, the safest approach is to not drink alcohol at all, to keep risks to the baby to a minimum.

Drinking alcohol during pregnancy can increase the risk of miscarriage and low birth weight, as well as the risk of developing Foetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS). In men, drinking too much alcohol can also cause fertility problems, including:

- reduced testosterone levels

- low sperm quality and quantity

- loss of interest in sex

As with smoking, these effects can be reversed if excess drinking is stopped. Many men support their partner by cutting down or avoiding alcohol too when they are getting pregnant and afterwards.

Interpregnancy health

The interpregnancy period is when women are ideally placed to receive contraceptive advice. This is because the transition from midwifery to health visiting in these time periods offers further potential to continue preconception care, as well as providing contraception immediately postpartum.

Women are also well placed to receive contraception immediately following the delivery of their baby and before they leave the place of birth. This ensures that the issue does not slip through the net at a time when the focus is often on the baby. Women report this to be highly acceptable, however contraceptive methods including the IUD and implant are often not available at this time.

The subsequent postnatal visits by midwives and health visitors are further opportunities to optimise the health of the mother, as they can be watchful for the emergence of any mental health issues and support return to a healthy weight, amongst other matters.

Infertility

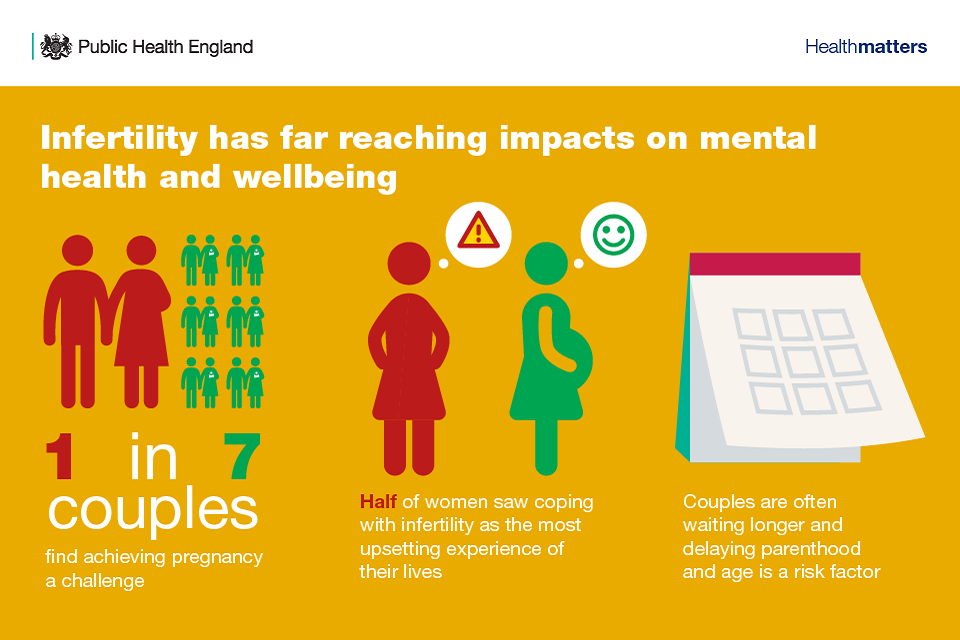

Most women will get pregnant if they desire a pregnancy. Within a year, 75% of women aged 30 and 66% of women aged 35 will conceive naturally and have a baby. However, 1 in 7 couples experience difficulty in conceiving, and this can have a significant impact on mental health and wellbeing.

Infographic showing impact of infertility on mental health and wellbeing

There is a growing trend in the UK for childbearing to occur at a later time in women’s lives. There are a number of reasons behind this including:

- the availability of safe, effective contraception

- opportunities to pursue further education

- taking time out to build a career

- achieving financial independence

- building a stable relationship with a partner

Biologically, the optimum period for childbearing is between 20 to 35 years of age. Beyond the age of 35, it becomes increasingly difficult to fall pregnant, and the chance of miscarriage rises.

Couples who have difficulty conceiving may choose to have fertility treatment. In vitro fertilisation (IVF) is one of several techniques available to help those experiencing infertility, and fertility guidelines published by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) make recommendations about who should have access to IVF treatment on the NHS in England and Wales. However, it is the local clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) that have the final say about who can have NHS-funded IVF treatment in England.

Making reproductive health and pregnancy planning everyday business

Reproductive health needs to be part of day-to-day business for many key services, and support for healthy behaviour change must be important for all.

Universal approaches

Prior to a woman’s first pregnancy, opportunities to embed both contraception and preconception care through relevant health and non-health contacts should be identified. One way to achieve this is by incorporating contraception and preconception care discussions into appointments for other aspects of care, such as postnatal contraceptive discussions and during cervical screening appointments.

Targeted approaches

The Marmot Review calls for universal action to reduce the steepness of the social gradient of health inequalities, but with a scale and intensity that is proportionate to the level of disadvantage. This is called proportionate universalism, and the key to this approach is to create the conditions for people to take control of their own lives. This requires action across the social determinants of health and beyond the reach of the NHS.

Along with national government departments, there is renewed emphasis on the role of local government and the voluntary and private sectors in addressing some of the wider determinants of poorer outcomes, such as worklessness, alcohol use and mental health.

Higher risk groups with multiple vulnerabilities are less likely to be well-reached by mainstream services, and the impacts of poor outcomes are likely to be greater and the intergenerational effects are magnified. As such, most of these women require a more intensive and multidisciplinary approach.

Local authorities and NHS commissioners

Local authorities and NHS commissioners should align work in their local areas towards a focus on contraception and preconception health. They should prioritise including pregnancy prevention and planning in all relevant policies and embed it into existing services. Developing policies that recognise the role of wider determinants in providing optimal circumstances in which to choose if and when to have a child, should also be prioritised.

There should be system leadership and shared accountability mechanisms in place, as many of these areas cross commissioning boundaries.

All women should be able to access reproductive health services across their life course. Women identified as at risk should receive additional targeted prevention. Targeted prevention should be linked to individual risk factors as well as the wider determinants of health.

Commissioners should:

- collaborate across organisations in order to take a system-wide and population-based approach to the provision of contraception and preconception care, maximising the proportions of the population reached

- regularly review local data and intelligence to inform both universal and targeted work

- consult with women, inclusive of gender and sexuality, to identify needs and barriers to service access

- commission targeted support services delivered in non-clinical settings and support women on a range of issues relating to a person-centred life course approach to reproductive health

- publicise targeted support services to women and encourage practitioners working with vulnerable groups to proactively promote the services

- consider the location of targeted prevention to engage women at risk who may be unable or unwilling to access services, for example, women in prisons, refugees and migrants

- look at data and local geography and try to reach women through these channels, for example, housing initiatives for drug and alcohol-dependent women and homeless women

Dr Asha Kasliwal, President FSRH, outlines what commissioners and local authorities can do to ensure an integrated reproductive health and pregnancy planning service.

Health professionals

Opportunistic care

Every interaction with a health professional is an opportunity to improve outcomes and change life chances. Preconception interventions should not be restricted to maternal and child health services, as they often require engagement from individuals who are not thinking about becoming pregnant in the near future.

All health professionals should:

- have daily interactions with patients to offer advice on healthy behaviours

- take opportunities to “make every contact count” for contraception and preconception care including at cervical screening, pregnancy testing and postnatal appointments

- actively support those who are intending to become pregnant with advice on preconception health

- take into account past pregnancies when offering advice to those who intend to become pregnant again

- offer advice in line with NICE guidance

Health professionals can also flag a new digital approach to their patients, which can help with preparation for pregnancy. Tommy’s, in partnership with PHE, NHS, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) and the UCL Institute for Women’s Health, have launched a new digital tool to give women all the information they need to know before pregnancy. The tool brings women through a questionnaire about their lifestyle, and then uses their answers to provide tailored advice on what can be done before pregnancy to have a healthy pregnancy and baby.

Postnatal advice and interpregnancy planning

Health professionals should follow the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH) 2018 guidance that recommends discussing contraception with all pregnant women.

When choosing an appropriate contraceptive method to use after pregnancy, women should be informed about the effectiveness of different contraceptives including the superior effectiveness of LARC.

Following childbirth, the FSRH guideline states that a woman’s chosen method of contraception can be initiated immediately if desired and she is medically eligible.

Women should also be advised that an interpregnancy interval of less than 12 months between childbirth and conceiving again is associated with an increased risk of preterm birth, low birthweight and small babies for their gestational age.

Post pregnancy and the health visitor offer is an opportunity to care for the wider needs of the new mother, including thinking about how to ensure pregnancies are spaced and that health in this time is optimised.

Women at higher risk of poor outcomes

a. Physical health

Specialist teams caring for women with long-term conditions can optimise pre-pregnancy health, support pregnancy planning and ensure safe medications are prescribed to women of reproductive age.

The 2015 NICE guideline for Diabetes in Pregnancy illustrates key aspects of preconception care which could translate to other long-term conditions: education, contraception advice, preventative actions (diet and physical activity being of particular relevance to diabetes), disease monitoring and medication safety.

b. Mental health

Mental ill-health is not uncommon in pregnancy, even for women who have never had an issue before; up to 20% of women experience mental health problems during pregnancy and the first year after birth. It is also acknowledged that up to 10% of fathers will suffer from postnatal depression.

In 2013 to 2014 there were about twice as many referrals for psychological therapy in women aged 15 to 24 as in men. Maternal mental health before and during pregnancy is a particular cause for concern, representing a further opportunity for improving the health of women.

Being aware of mental wellbeing before, during and after pregnancy is important. Most people with mental ill-health improve with care, such as a treatment called talk therapy, which is not based on medication.

c. Complex social needs

Local areas should map high risk populations and the services they are in contact with such as mental health services, migrant populations and domestic violence services, and develop a strategy so that care is tailored particularly to these populations addressing their needs in an integrated way.

Indicators of reproductive health and pregnancy planning

Indicator sets

Indicator sets that combine planning and preventing pregnancy should be developed so that local areas have a system-wide view of how well the population are served.

Measure of pregnancy planning

There is a need for a more sophisticated measure for recording whether or not a pregnancy is planned.

Evidence suggests that pregnancy planning is not a simple ‘yes or no’ concept.

The London Measure of Unplanned Pregnancy (LMUP), a validated retrospective measure of pregnancy intention, scores the degree of pregnancy planning from 0 to 12. Whilst it is currently used in research settings, in the future the LMUP could be used in routine antenatal care to help UK health professionals identify to what extent a pregnancy is planned, and as a tool to underpin conversations about behaviour change opportunities that can go alongside the planning process.

The LMUP will also be useful at a population level to assess the effectiveness of local policies and plan services.

Recording preconception health status

To benchmark and evaluate progress on preconception and early pregnancy health, recording the status of women’s preconception health is important. Improving the quality and completeness of data collected at booking in the maternity services dataset will support the development of preconception health indicators for this purpose.

Resources

Download supporting references.

Download the Health matters infographics.

Read the Health matters blog.

Watch Health matters videos.

Download case study: Preconception and pregnancy: opportunities to intervene.

Download case study: Immediate postnatal contraception.

Download A consensus statement: reproductive health is a public health issue.