Chapter 7: current and emerging health protection issues

Published 11 September 2018

1. Main messages

Health protection is a relatively recent description of a set of functions to protect individuals and populations through an integrated approach to infectious diseases, radiation, and chemical and environmental hazards.

Air pollution contributes to an estimated 28,000 to 36,000 deaths in the UK every year. There are opportunities to reduce air pollution and address climate change together, as the causes are similar, with ‘co-benefits’ for both reducing non-communicable diseases and improving wellbeing.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) describes the change of an organism which makes a previously effective treatment ineffective. One of the main influences on AMR is the use of antibiotics. Between 2012 and 2016, overall antibiotic prescribing reduced by 5% in England.

There is wide variation across England in new diagnosis of sexually transmitted infections. In 2017 there were higher rates in more deprived areas, and for some infections, among young heterosexuals, people in the Black ethnic group and men who have sex with men (MSM). Although the incidence of most infections has been falling in recent years, syphilis diagnoses have risen 148% between 2008 and 2017, including a 20% rise between 2016 and 2017.

Hepatitis C is a bloodborne virus that often has few symptoms. As a consequence, many individuals with chronic infection remain undiagnosed and fail to access treatment. However, between financial years 2015 to 2016 and 2016 to 2017, the number of people accessing treatment increased from 6,066 to 9,440, representing a 56% increase, and there was fall in deaths from complications of the infection. In line with internationally agreed targets, the UK aims to eliminate hepatitis C as a public health problem by 2030.

The number of new cases of tuberculosis (TB) in England has fallen since 2011. The incidence remains higher in the non-UK born population than the UK born population. Between 2010 and 2015, 18.2% of all cases among people born in the UK had a social risk factor (drug misuse, alcohol misuse, homelessness or imprisonment). Addressing social risk factors is therefore important in reducing the number of new cases of TB.

There have been major improvements in morbidity and mortality from vaccine-preventable diseases over recent decades. Recent outbreaks of measles in England, an infectious disease that can lead to serious complications and even death, highlight the importance of maintaining high vaccination coverage.

2. Introduction

Infectious diseases and environmental threats are once again at the forefront of public health, after decades of decline. This year marks the centenary of the 1918 H1N1 (‘Spanish flu’) pandemic which killed between 20 to 40 million people, and pandemic influenza remains the most significant civil risk facing the UK (discussed in the Health Profile for England 2017).

The black smog which once shrouded British cities has now cleared but it is estimated that invisible air pollution still produces an effect equivalent to 28,000 to 38,000 deaths in the UK annually[footnote 1]. Ninety years on from Alexander Fleming’s first discovery of penicillin in 1928, we have a growing problem of antimicrobial resistance in the UK and across the globe.

Health protection as discussed here is a relatively new description of a set of functions to protect individuals and populations through an integrated approach to infectious diseases, radiation, chemical and environmental hazards. This system emerged in the UK from a series of system failures, including the Stafford Hospital Legionnaires’ disease outbreak in the 1980s, and the foot and mouth disease outbreak in 2001. Health protection in England was formalised in 2003 through the amalgamation of radiation, microbiology and chemical functions.

Over the intervening years, the health protection challenges which have emerged are increasingly global, interdisciplinary and challenging. Public Health England has health protection teams operating across 9 centres in England which respond to around 11,500 disease outbreaks and incidents every year. Whilst routine work primarily relates to infectious diseases, high profile incidents over the last year such as the Grenfell Tower fire and the chemical poisoning in Salisbury highlight the value of a flexible and responsive health protection system.

Threats to health are not equally shared; the impoverished, incarcerated, institutionalised and homeless are often at far higher risk of illness and premature mortality than the general population [footnote 2]. Marginalised populations experience extremes of poor health due to a combination of poverty, social exclusion and increased burden of risk factors [footnote 3].

Documenting the extent of health inequalities of populations without a fixed address is challenging as they can often be missed from routine datasets [footnote 2]. Inequalities in health and the wider determinants of health are discussed in further detail in Chapter 5 and Chapter 6.

This chapter will build upon the Health Profile for England 2017 drawing attention to emerging issues in health protection and cross-linkages with other important public health challenges we face.

3. Climate change and air pollution

The causes of air pollution and climate change are closely related and efforts to address these challenges often overlap. Both arise mainly from burning fossil fuel and transport emissions. Shifting from motorised to active forms of transport, such as walking and cycling, can reduce the levels of particulate matter (PM) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) while also contributing to reducing the burden of obesity and non-communicable diseases – known as ‘co-benefits’. This approach can also reduce healthcare costs with substantial benefits for public health [footnote 4].

The UK is a signatory to a series of United Nations landmark agreements, including the Sendai Framework on Disaster Risk Reduction, Paris Climate Change Agreement and the Sustainable Development Goals. There are opportunities to reduce air pollution and address climate change in ways which fulfil international agreements and create sustained benefits for health [footnote 5].

3.1 Climate change

In 2008 the Climate Change Act came into force in the UK. It was the world’s first long-term, legally binding framework, to deal with the dangers of climate change and committed the UK to reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by at least 80% by 2050. The Climate Change Act also requires the UK government, and devolved administrations, to produce a National Adaptation Programme (NAP) to help the country respond to the risks of climate change, including specific objectives for the health and social care sector.

In 2015 the UK signed the Paris Climate Change Agreement, an internationally agreed framework to limit global temperature rise to well below 2°C on pre-industrial levels, in recognition of the grave threat which climate change poses to humanity.

Extreme weather events and disasters are increasing in the UK and across the world [footnote 6]. In the UK, 5 million properties are at risk of flooding from rivers or the sea, with substantial implications for mental health [footnote 7] (discussed in the Health Profile for England 2017) and public finances - the 2015 to 2016 floods cost £1.6 billion alone [footnote 8].

Increased frequency and intensity of hot weather is one of the most likely effects of climate change. The 2017 UK Climate Change Risk Assessment identified this as a priority area in recognition of the risk this poses to health, wellbeing and productivity. Already around 20% of homes and 90% of hospital wards are thought to be at risk of overheating in the current climate. Without further adaptation, heat related deaths are expected to increase from 2,000 to 7,000 per year by 2050 [footnote 9].

3.2 Air pollution

During the 1950s, smog (a toxic combination of soot and sulphur dioxide) was commonplace in UK cities and a major source of ill health. Since the Clean Air Act of 1956, the character of air pollution in the UK has changed and much of it is invisible to the naked eye. The major pollutants in urban environments, particulate matter (PM 2.5 and PM 10, which are particles with diameters smaller than 2.5µm and 10µm respectively) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2), derive predominantly from transport.

Assessing the health burden of air pollution is challenging as the impact is related to the concentration of a pollutant and the exposure of an individual. Both short term and long term exposure can adversely affect health.

It is estimated that long-term exposure to the air pollution mixture in the UK has an annual effect equivalent to 28,000 to 36,000 deaths [footnote 1]. Recent modelled data shows that reducing the concentration of PM 2.5 by 1µg/m3 in a single year can reduce the burden of a range of conditions, including coronary heart disease, stroke, asthma, and lung cancer (Figure 1). A 1 µg/m3 reduction in PM 2.5 in England in a single year can prevent around 50,000 cases of coronary heart disease, 16,500 strokes, 9,000 cases of asthma and 4,000 lung cancers over the following 18 years [footnote 10].

Figure 1: cumulative new cases of disease avoided by 2035 for 1 µg/m3 reduction in PM 2.5, England

Figure 1: cumulative new cases of disease avoided by 2035 for 1 µg/m3 reduction in PM2.5, England [Source: Estimation of costs to the NHS and social care due to the health impacts of air pollution, Pg. 32-32. Produced by Public Health England, 2018]

There are inequalities in the health impacts of air pollution. Highest exposures are in busy, urban environments, often with high levels of deprivation. For further detail on the geographical variation of air pollution refer to Chapter 6.

4. Antimicrobial resistance

When Alexander Fleming was awarded the Nobel Prize for the discovery of penicillin in 1945 he described the threat of resistance. Antimicrobials are vital to almost all aspects of modern medicine, including surgery and cancer treatment. Despite warnings, the global community has only recently awoken to the implications of this threat. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) describes the change of an organism which makes a previously effective treatment ineffective.

One of the main drivers of AMR is the use of antibiotics. On a global level, it is estimated that antimicrobial resistance is responsible for 700,000 deaths each year which could increase to 10 million deaths per year by 2050 without coordinated action. This includes better sanitation, improved public awareness and a rapidly developed new drug pipeline [footnote 11].

4.1 Gram negative bloodstream infections

Gram negative bloodstream infections are caused by a class of bacteria which rapidly develop resistance to existing treatments (the main organisms in this group are E.Coli, Klebsiella and Pseudomonas). These are the leading causes of healthcare associated bloodstream infections. The government has set a target of halving healthcare associated gram-negative bloodstream infections by 2021 and has set an ambition of reducing inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing by 50%, over the same time frame, in order to achieve this [footnote 12].

Between 2012 and 2016, overall antibiotic prescribing in England reduced by 5% in humans, with declines across all drug classes [footnote 12]. Cases of E. coli, the most common gram negative bloodstream infection, have continued to rise in line trends described in the Health Profile for England 2017.

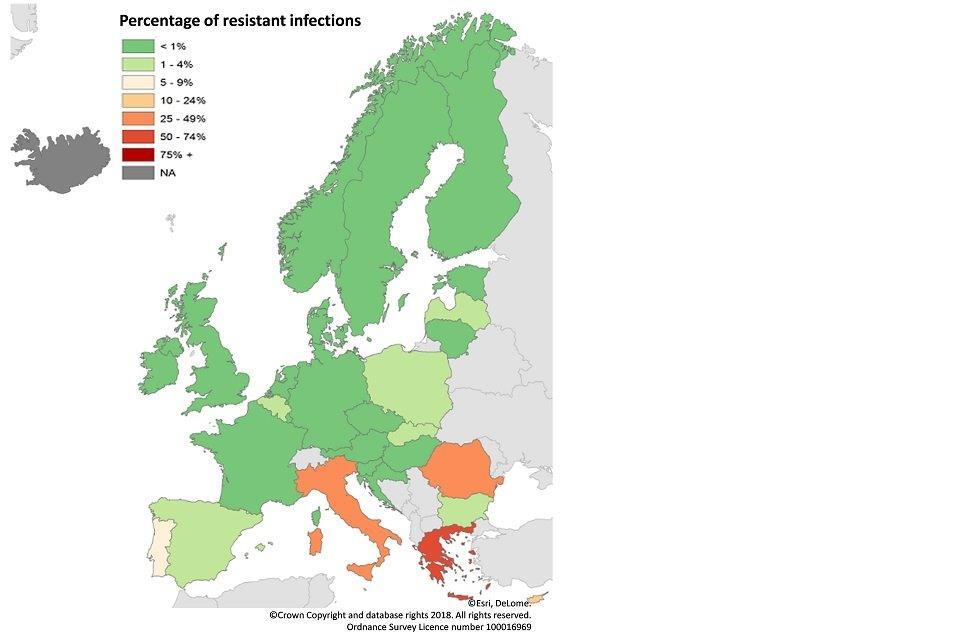

A particular concern globally is the spread of carbapenemase-producing gram-negative infections (CPE) which are resistant to carbapenem antibiotics – often the last line treatment in severe bacterial infections. Antimicrobial resistance to carbapenems is currently at low levels in England; however, there is considerable variation across Europe (Figure 2). In 2016 there was less than 1% resistance in most of northern Europe, including the UK, in contrast to 5.2% in Portugal, 31.4% in Romania, 33.9% in Italy and 66.9% in Greece [footnote 13].

Of concern is the potential for levels to rise quickly. For example, Italy had 1% to 2% resistance from 2006 to 2009 but by 2014 this had increased to 33% at which point control efforts became expensive and challenging [footnote 14]. This reinforces the need for proactive control measures which are vital to prevent the rapid development of resistance.

Figure 2: percentage of Klebsiella pneumoniae infections resistant to carbapenem antibiotics, Europe, 2016

Figure 2: percentage of Klebsiella pneumoniae infections resistant to carbapenem antibiotics, Europe, 2016 [Source: Surveillance atlas of infectious disease. Produced by European Centres for Disease Control, 2016]

5. Sexually transmitted infections

The epidemiology of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) has changed markedly over the last two decades, reflecting changes in demographics, individual behaviours, surveillance techniques, diagnostics and treatments. There is wide variation across the country in new diagnosis of STIs.

In 2017 there were higher rates in more deprived areas (Figure 3), and for some infections, among young heterosexuals (15 to 24 years), people from the Black ethnic minority group and men who have sex with men (MSM) [footnote 15]. Antimicrobial resistance is a growing challenge in reducing STIs. England average = 794

Figure 3: new sexually transmitted infections diagnoses

Figure 3: new sexually transmitted infections diagnoses* rate by deprivation decile** in England, 2017 [Source: Sexual and Reproductive Health Profiles]

*excluding Chlamydia in people aged under 25 years.

**deprivation deciles based on groups of district and unitary authorities in England (Index of Multiple Deprivation 2015).

5.1 Gonorrhoea, chlamydia and syphilis

Following a rapid increase over the period 2008 to 2015, diagnoses of gonorrhoea among MSM have fallen. In early 2018 a multidrug resistant strain of Neisseria gonorrhoea was isolated in a patient in the UK – a first of its kind globally. Two further cases were reported soon after in Australia, highlighting growing concern of multidrug resistant gonorrhoea in a globalised world [footnote 16].

Over this period chlamydia diagnoses have been stable. However, syphilis diagnoses increased by 148% between 2008 and 2017, including a 20% rise from 2016 to 2017 - there were 7,137 new diagnoses in 2017, which was the highest level since 1949 [footnote 15]. This highlights the need for a comprehensive sexual health approach which promotes collaboration with partners across the health and care system.

The PHE health promotion strategy for sexual and reproductive health focuses on reducing STIs, unwanted pregnancies and teenage pregnancies, and HIV transmission through an integrated approach. Improving the sexual health of young people continues to focus on increasing condom use and positive relationship building through promoting high quality sex education delivered in schools [footnote 15].

5.2 Human papilloma virus

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a group of infections primarily transmitted through sexual contact which are associated with genital warts and anogenital cancers, predominantly in women. HPV is associated with almost all cervical cancers. The vaccine is around 99% effective against the 2 types (HPV 16 and 18) which cause over 70% of cases.

In 2008 the national HPV vaccination programme was introduced for girls aged 12 to 18. This has had uptake of around 85%, with lower uptake among minority ethnic groups. Cases of first episode genital warts among females 15 to 17 were 90% lower in 2017 compared to 2009 reflecting the effectiveness of the HPV vaccination programme [footnote 15]. The vaccination has a crucial role, together with the cervical screening programme, in reducing the burden of cervical cancer and improving sexual and reproductive health, while providing herd protection for heterosexual men.

HPV infections are associated with approximately 80% to 85% of anal cancers, 35% of oropharyngeal cancers and 50% of penile cancers in men, as well as genital warts. MSM bear an increased burden of HPV associated disease and are far less likely to benefit from this HPV vaccination programme than heterosexual men. Following a successful PHE led pilot in 2016 to 2018, the HPV vaccine has been offered to MSM under 45 years attending genito-urinary medicine (GUM) and HIV clinics since April 2018 [footnote 17].

6. Blood borne viruses

6.1 Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C is a bloodborne virus that is often asymptomatic, and symptoms may not appear until the liver is severely damaged. Consequently, many individuals with chronic infection remain undiagnosed and fail to access treatment [footnote 18].

Across the world 71 million people have chronic hepatitis C infection, resulting in 400,000 deaths annually. It is estimated 160,000 people in England have chronic hepatitis C infection, of which half are undiagnosed [footnote 18]. Over 90% of these infections are associated with injecting drug use and approximately half of people who inject drugs (PWID) are infected with hepatitis C. Hepatitis C prevention, through increasing access to clean needles in community drug services, is therefore vital for disease control. In England, Wales and Northern Ireland, in 2016, 17% of PWID reported sharing needles over the last 4 weeks, which has decreased from 23% in 2006 [footnote 19].

Direct-acting antiviral (DAA) medications, a new class of drugs for the treatment of hepatitis C, came to market in 2014. The combination of over 90% cure rates, shorter course duration and fewer side effects have transformed prospects for disease control. The UK has signed up to the World Health Organization (WHO) strategy on viral hepatitis which commits to eliminating hepatitis C as a major public health threat by 2030 [footnote 18].

Whilst high costs initially impeded the scale and pace of treatment with DAAs [footnote 20], the numbers of people accessing treatment rose from 6,066 in financial year 2015 to 2016 to 9,440 in 2016 to 2017 (a 55.6% increase), with a corresponding decrease in deaths from complications of the infection [footnote 18].

Regular, confidential hepatitis C testing of people who inject drugs, with linkage to treatment and care services, is a major component to hepatitis C control. The numbers of people who have ever been tested have been increasing, however, the proportion of those tested regularly has remained largely static over the last decade [footnote 18].

6.2 HIV

New HIV diagnoses in England fell in 2016. This was most notable among gay and bisexual men living in London (Figure 4), in which new diagnoses reduced 29% from 1,554 in 2015 to 1,096 in 2016. Addressing HIV in this group is challenging and internationally the UK has been a leader in this area. The decline is in part due to a significant increase in HIV testing at sexual health clinics over the last decade (37,224 in 2007 to 143,560 in 2016), which includes the targeting of high risk individuals. It is likely that pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), condom use and improvements in anti-retroviral therapies have also contributed to the decline in cases [footnote 21].

The PrEP Impact Trial which is currently underway is assessing the efficacy of PrEP in reducing the risk of developing HIV. This is one of 12 projects PHE are funding through the HIV Prevention Innovation Fund.

Figure 4: number of new HIV diagnoses in gay and bisexual men by region, England, 2007 to 2016

Figure 4: number of new HIV diagnoses in gay and bisexual men by region, England, 2007 to 2016 [Source: HIV in the United Kingdom: decline in new HIV diagnoses in gay and bisexual men in England. Produced by Public Health England, 2017]

Late diagnosis, measured as CD4 <350 cells/mm3 (a measure of immune response), is lower among gay and bisexual men (32%) as compared to heterosexual women (47%) and heterosexual men (60%) reflecting ongoing areas for improvement in all groups [footnote 21]. Early diagnosis improves outcomes for the individual affected and reduces the likelihood of onwards transmission.

Currently, around one in 100 people who inject drugs have HIV, a figure which has been stable. Emerging practices such as ‘slamming’ – the injection of drugs before or during sexual activity – are increasingly frequent among MSM attending drug services and could increase HIV and hepatitis C prevalence in this group. Understanding the social and behavioural factors which influence the spread of disease is important for effective monitoring and disease control [footnote 19].

7. Respiratory infections

7.1 Tuberculosis (TB)

TB (tuberculosis) is an infectious disease that usually affects the lungs, although it can affect almost any part of the body. TB rates in England have decreased dramatically over the last century (Figure 5).

Between 1914 and 1987 notifications for TB fell from 99,497 to 5,086, reflecting improved social conditions and subsequent emerging diagnostics and treatments, before climbing to 8,371 in 2011. There have been sustained decreases in tuberculosis cases since 2011, as outlined in the Health Profile for England 2017; however, England continues to have one of the highest TB rates in Western Europe [footnote 22].

Figure 5: trend in the number of TB notifications, England and Wales, 1914 to 2016

Figure 5: trend in the number of TB notifications, England and Wales, 1914 to 2016 [Source: TB case notifications by site of disease, England and Wales, 1914-2016. Produced by Public Health England, 2017]

Robert Koch, who isolated the tuberculosis bacilli, described the condition as a social disease, requiring an understanding of the social and economic factors which put individuals at risk [footnote 23]. In England in 2016, the incidence rate of TB in the non-UK born population was 15 times higher than the rate in the UK born population [footnote 24].

Of the total number of tuberculosis cases among people born in the UK in 2010 to 2015, 18.2% had a social risk factor (history of drug misuse, alcohol misuse, homelessness or imprisonment) which is 2.6 times higher than the percentage among non-UK born people. The absolute number and proportion of cases with a social risk factor was increasing up to 2015 [footnote 25]. This underlines the affinity of tuberculosis with poverty, as well as geography.

Figure 6: percentage of TB cases by social risk factors, England, 2010 to 2015

Figure 6: percentage of TB cases by social risk factors, England, 2010 to 2015 [Source: Tackling TB in Under-Served Populations: A Resource for TB Control Boards and their partners. Produced by Public Health England, 2017]

The England TB strategy aims to reduce incidence by 50% by 2025 and ultimately eliminate TB as a public health problem (defined as <1 case per million population), through different methods, including: latent TB screening, improving early diagnosis, targeted BCG vaccination and reducing drug resistance [footnote 26].

7.2 Influenza

Seasonal influenza is a respiratory viral infection which in otherwise healthy individuals is typically a self-limiting disease. The public health effect varies considerably with the predominant circulating strains, the age groups most affected and the match of the vaccine. Up to a third of people with flu display no symptoms, yet some people, particularly those with underlying risk factors, can experience a much more serious infection. Influenza is a contributing factor to excess winter deaths [footnote 27].

As described in the Health Profile for England 2017, excess winter deaths are thought to be due to a complex interplay between weather, circulating viruses (including influenza) and an elderly population.

Although excess winter deaths have fallen in recent decades, there was a sharp rise in 2015 (Figure 7). Total excess winter deaths for 2017 to 2018 are not yet available, but it is estimated that approximately 16,000 deaths were associated with influenza in the 2017 to 2018 winter season [footnote 27]. This is similar to 2016 to 2017, though lower than 2014 to 2015 when influenza A(H3N2) – a strain which particularly affects the elderly – also dominated.

Figure 7: trend in the number of excess winter deaths, England and Wales, winter 1950 to 1951 up to winter 2016 to 2017 [A12]

Figure 7: trend in the number of excess winter deaths, England and Wales, winter 1950 to 1951 up to winter 2016 to 2017 [Source: Excess winter mortality in England and Wales: 2016 to 2017 (provisional) and 2015 to 2016 (final). Produced by Office for National Statistics, 2017]

Influenza outbreaks in institutional settings pose a particular problem due to the speed at which infections can spread between individuals. The majority of outbreaks occur in care homes where vulnerable individuals are at higher risk of contracting influenza and developing complications [footnote 27].

Vaccination is a critical part of the influenza prevention strategy and uptake in children, at risk adults, the elderly and health care workers continue to increase year on year. Nearly one and a half million more people were vaccinated during 2017 to 2018 than the season before [footnote 28].

Pandemic influenza refers to a novel influenza virus of which there is little or no pre-existing immunity, which allows it to spread rapidly. Previously healthy people, including young people, are more likely to experience severe symptoms, due to poor immunity, such as was the case in the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, and the 3 major pandemics in the last 100 years. For further discussion, see Health Profile for England 2017.

8. Emerging infectious diseases

The 2014 to 2016 Ebola virus disease outbreak in West Africa killed more than 11,300 people [footnote 29]. It began in Guinea, spread across borders into Sierra Leone and, Liberia (these 3 countries sustained the largest numbers of cases), with limited regional spread. For the first time in an Ebola outbreak, a small number of cases occurred in humanitarian aid workers who returned to their country of origin and onwards across the globe, including the United Kingdom.

There were multiple inter-linking factors which contributed to the outbreak, including deforestation in the region which increased human contact with bats carrying the infection [footnote 30], urbanisation and greater population mobility which drove regional and transnational spread of disease. The lack of surveillance mechanisms and effective vaccines or treatments compounded these problems and highlighted the shortcomings of the global health security framework, including pharmaceutical funding models for emerging infectious diseases [footnote 31].

Ebola outbreaks continue to occur with the most recent in Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in 2017 and 2018. In response to deficiencies identified during the West Africa outbreak, WHO has increased partnership working during health emergencies and improved the speed of response [footnote 32].

Infectious diseases such as Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), Zika virus and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) have emerged from across the globe and spread rapidly - new diseases will be no different. Historically, diseases have emerged from all continents and spread across the globe (Figure 8).

Figure 8: global map of emerging infections since 1997

Figure 8: global map of emerging infections since 1997 [Source: Emerging infections: how and why they arise. Produced by Public Health England, 2018]

A combination of factors contribute to the emergence of new infections. Around 60 to 80% of emerging infections come from an animal source and monitoring of zoonotic diseases is an important component of protecting public health [footnote 33].

Strong infectious disease surveillance, including mechanisms to support low-resource countries to fulfil their obligations under the international health regulations, and engagement of the UK Public Health Rapid Support Team during an outbreak are critical to protecting the United Kingdom and improving global health security. Many diseases have emerged from East Asia where there is close contact between poultry and humans, and sub-Saharan Africa where there is limited public health surveillance (Figure 8).

9. Vaccine preventable diseases

After observing that milkmaids were protected from outbreaks of smallpox, Edward Jenner proposed the inoculation of healthy humans with material from livestock suffering from pox-like diseases. Vaccination, from the French ‘vache’ (cow), transformed the landscape of infectious disease control and has saved countless lives - smallpox is estimated to have killed 300 million people in the 20th century alone [footnote 34].

The disease followed the path of European empires in the 15th to 19th century, bringing smallpox to communities in the Americas and Africa, which had no previous immunity to the disease, with devastating effect [footnote 34]. The subsequent eradication of smallpox in 1980 embodies the power of global collective action and remains one of the most celebrated public health achievements.

Control of other devastating diseases such as polio, measles, rubella and haemophilus influenza, have led to dramatic improvements in childhood survival. More recent developments such as the introduction of the childhood rotavirus vaccine (2013) and the HPV vaccine (Section 5.2) continue to demonstrate the value of new vaccinations.

9.1 Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A virus infection causes a range of illnesses from mild symptoms through to hepatitis and liver failure and is normally spread by the faecal-oral route, or occasionally blood. Improved social conditions have led to steep reductions in the numbers of cases. From mid-2016 there was an increase in cases of hepatitis A, involving three distinct strains originating in Europe. The increase was initially among MSM living in London but then spread across the UK [footnote 35].

Due to a global vaccine shortage vaccine sparing recommendations were implemented to preserve UK stock, with sexual health services able to access a central stockpile to protect MSM. The outbreak came under control in early 2018. The outbreak reflects the social dimensions of infectious disease outbreaks, the importance of collaboration with national partner institutions and the vital role of high quality epidemiological intelligence to guide the response [footnote 36].

9.2 Measles

A consequence of effective vaccination programmes is that many deadly, disfiguring diseases are fading in the collective consciousness. Meanwhile, some diseases that have been previously well controlled, such as measles, have re-emerged among unvaccinated communities. Measles is a viral illness that can lead to serious complications and even death. Prior to the introduction of the vaccination in 1968, measles notifications every year in the UK numbered 160,000 to 800,000 with around 100 deaths [footnote 37].

Measles is an extremely infectious disease; therefore, increasing vaccine coverage over the 1980s and 1990s was vital to controlling the disease. Following the now discredited work of Andrew Wakefield in 1998 which falsely linked the measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine with autism, vaccination uptake fell significantly below the required threshold for herd immunity [footnote 38].

In 2017, England met the WHO target of 95% coverage and achieved elimination status; however, outbreaks continue to occur in pockets of the population with low vaccine uptake. Half of the cases in the UK since have occurred in people over 15 years old reflecting the legacy of Wakefield, the value of strong public health surveillance, and the coordinated action required to control infectious disease [footnote 38].

10. Further information

The challenges we face are increasingly global and require collaborative action within communities and between countries. The growing threat which problems such as emerging infectious diseases, air pollution and antimicrobial resistance pose are driven by a diverse range of factors from environmental change, urbanisation and the widening gaps between the least and most deprived communities. This requires an integrated approach with input from far beyond the health sector.

More information on the health protection issues covered in this chapter can be found on the PHE website and data on several areas including AMR, STIs and TB can be explored through the PHE Fingertips Portal.

11. References

-

Committee on the Medical Effect of Air Pollutants (2018) COMEAP: Associations of long-term average concentrations of nitrogen dioxide with mortality. Accessed 6 September 2018. ↩ ↩2

-

Aldridge R, Story A, Hwang SW and others. (2018) Morbidity and mortality in homeless individuals, prisoners, sex workers, and individuals with substance use disorders in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 391, 10117; 241 to 250. ↩ ↩2

-

Marmot M (2010) Fair society, healthy lives the Marmot Review: strategic review of health inequalities in England post-2010. Accessed 18 July 2018. https://www.gov.uk/dfid-research-outputs/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review-strategic-review-of-health-inequalities-in-england-post-2010 ↩

-

Jarrett J, Woodcock J, Griffiths UK, and others. (2012) Effect of increasing active travel in urban England and Wales on costs to the National Health Service. Lancet 379: 9832. ↩

-

Watts N, Amann M, Ayeb-Karlsson S, and others. (2108) The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: from 25 years of inaction to a global transformation for public health. Lancet 391:10120 (581 to 630). ↩

-

United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (2015) Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030. Accessed 20 July 2018. ↩

-

Jermacane D, Waite TD, Beck CR and others. (2018) The English National Cohort Study of Flooding and Health: the change in the prevalence of psychological morbidity at year two. BMC Public Health 18:330. ↩

-

Environment Agency (2018). Estimating the economic costs of the 2015 to 2016 winter floods. Accessed 20 July 2018. ↩

-

Hajat S, Vardoulakis S, Heaviside C, Eggen B (2014) Climate change effects on human health: projections of temperature-related mortality for the UK during the 2020s, 2050s and 2080s. J Epidemiol Community Health 68:641 to 648. ↩

-

PHE (2018). Estimation of costs to the NHS and social care due to the health impacts of air pollution. pp 32 to 33. Accessed 20 July 2018. ↩

-

O’Neil J [chair] (2016) Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally. Accessed 20 July 2018. ↩

-

PHE (2017) English surveillance programme for antimicrobial utilisation and resistance (ESPAUR). Accessed 20 July 2018. ↩ ↩2

-

European Centres for Disease Prevention and Control (2018) Surveillance Atlas of Infectious Diseases. Accessed 18 July 2018. ↩

-

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2016) Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriacae: Rapid Risk Assessment. Stockholm: ECDC. ↩

-

PHE (2017) Sexually Transmitted Infections and Chlamydia Screening in England 2017. Accessed 18 July 2018. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

PHE (2018) UK case of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with high-level resistance to azithromycin and resistance to ceftriaxone acquired abroad. Accessed 20 July 2018. ↩

-

PHE (2018) HPV vaccination programme for men who have sex with men (MSM): Clinical and operational guidance. Accessed 18 July 2018. ↩

-

PHE (2018) Hepatitis C in England and the UK. Accessed 18 July 2018. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

PHE (2017 update) Health Protection Scotland, Public Health Wales, Public Health Agency Northern Ireland. Shooting up: infections among people who inject drugs in the UK, 2016. Accessed 20 July 2018. ↩ ↩2

-

Gornall J, Hoey A, Ozieranski P (2016) A pill too hard to swallow: how the NHS is limiting access to high priced drugs. BMJ 354:i4117. ↩

-

PHE (2017) HIV in the United Kingdom: decline in new HIV diagnoses in gay and bisexual men in London, 2017 report. Accessed 20 July 2018. ↩ ↩2

-

WHO, ECDC (2018). Tuberculosis surveillance and monitoring in Europe, 2018. Accessed 20 July 2018. ↩

-

Daniel TM (2006) The history of tuberculosis. Respiratory Medicine 100(11):1862 to 1870. ↩

-

PHE (2017) Tuberculosis in England, 2017 Report. Accessed 20 July 2018. ↩

-

PHE, TB alert, NHS (2017) Tackling tuberculosis in under-served populations: A resource for TB control boards and their partners. Accessed 19 July 2018. ↩

-

PHE, NHS England (2015) Collaborative Tuberculosis Strategy for England 2015 to 2020. Accessed 19 July 2018. ↩

-

PHE (2018) Surveillance of influenza and other respiratory viruses in the UK: Winter 2017 to 2018. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

PHE, DHSC, NHSE (2018). The national flu immunisation programme 2018/19 (letter). Accessed 2 July 2018. ↩

-

World Health Organization (2016) Ebola Outbreak 2014-2015. Accessed 7 June 2018. ↩

-

Olivero J, et al. (2017) Recent loss of closed forests is associated with Ebola virus disease outbreaks. Scientific Reports 7:14291. ↩

-

Science and Technology Committee (2016). Science in emergencies: UK lessons from Ebola (Second Report of Session 2015-16). London, House of Commons. ↩

-

WHO Ebola Response Team (2016) After Ebola in West Africa - Unpredictable Risks, Preventable Epidemics. NEJM 11;375(6):587 to 596. ↩

-

PHE (2018) Emerging infections: how and why they arise. Accessed 20 July 2018. ↩

-

Fenner F, Henderson DA, Isao A, and others. Smallpox and its eradication. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1988. p. 232. ↩ ↩2

-

PHE (2017) Hepatitis A Outbreak in England Under Investigation. Accessed 20 July 2018. ↩

-

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2018) Epidemiological update: hepatitis A outbreak in the EU/EEA mostly affecting men who have sex with men. Accessed 18 July 2018. ↩

-

Vanessa S. Measles has been eliminated in the UK – so why do we still see cases and outbreaks?. Accessed 20 April 2018. ↩

-

Ramsay, ME. Measles: the legacy of low vaccine coverage. Arch Dis Child (2013) Vol 98 No 10. ↩ ↩2