HPR volume 13 issue 8: news (1 March)

Updated 20 December 2019

Group A streptococcal infections: first report on seasonal activity, 2018 to 2019

Public Health England continues to monitor notifications of scarlet fever in England, following the high levels recorded last spring.

According to the first report on group A Streptococcus activity for the current 2018 and 2019 season [1,2], typical seasonal increases in scarlet fever activity are being reported across England and - as of February 2019 - activity remains elevated, suggesting this may be the sixth year in a row with high levels of scarlet fever incidence.

Invasive disease rates are above average, but remain within the upper bounds of normal seasonal levels for this time of year.

GPs, microbiologists and paediatricians are reminded of the importance of prompt notification of scarlet fever cases and outbreaks to local PHE health protection teams, obtaining throat swabs (prior to commencing antibiotics) when there is uncertainty about the diagnosis, and ensuring exclusion from school/work until antibiotic treatment has been received for 24 hours [3]. Due to rare but potentially severe complications associated with GAS infections, clinicians and HPTs should continue to be mindful of the recent increases in invasive disease and maintain a high degree of clinical suspicion when assessing patients.

References

- Group A streptococcal infections: first report on seasonal activity, 2018/19.

- Parents encouraged to be aware of scarlet fever symptoms, PHE news story, 28 February.

- PHE (2017). Guidelines for the public health management of scarlet fever outbreaks in schools, nurseries and other childcare settings.

Revisions to Zika sexual transmission guidance and Zika country risk terminology

Travel health guidance for those visiting areas with risk for Zika virus transmission, available from PHE, has recently been updated [1]. The principal changes are: updating of advice on Zika virus sexual transmission, and simplification of the terminology used to describe risk of transmission (via mosquito bites) in Zika affected countries.

Risk of Zika virus infection arises mainly following a bite of an infected Aedes mosquito; however, a small number of cases have occurred through sexual transmission. Precautionary travel health advice relating to sexual transmission focusses on advice for all travellers to countries with risk for Zika virus transmission. The advice provides information on the use of barrier methods (for example, condoms) and avoiding conception during travel, and for specific periods after travel based on the evidence on the persistence of Zika in semen.

The main change in the guidance is a reduction in the recommended waiting period for male travellers after the last potential Zika virus exposure, from 6 to 3 months. The guidance continues to recommend that couples considering pregnancy should consider the Zika risk in countries prior to travel and then make informed decisions about whether they indeed wish to travel to that country, as well as when they can commence trying to conceive after travelling. This advice does not apply to areas considered to be at ‘very low risk’ of Zika virus.

Countries or areas with risk for Zika virus transmission are now classified into two categories - ‘risk’ (previously ‘high or moderate’), and ‘very low risk’ (previously ‘low’).

The changes reflect better understanding of the risk of transmission that is present in most affected countries, improved understanding of the different patterns of Zika virus transmission (for example, outbreaks, endemicity, and interruption of transmission). The precautionary advice is now proportional to risk, and provides for greater personal choice for pregnant women who may need to travel to ‘risk’ areas, while still providing advice to minimise risk. PHE has published The A-to-Z list of countries and areas with risk for Zika virus transmission.

The Country Information Pages on the NaTHNaC website have been updated to reflect the Zika risk categories and corresponding advice for travellers and pregnant women.

Information and guidance documents published by PHE are regularly reviewed and revised in light of new evidence. See the Zika virus collection for latest updates. Health professionals and travellers should consult the country information pages on NaTHNaC’s Travelhealthpro website for the latest travel health advice for their destination.

Reference

- PHE advice on Zika virus: preventing infection by sexual transmission.

EVD outbreak in eastern DRC: seventh update

The outbreak of Ebola virus disease in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo continues to present significant challenges to control, seven months after the first case was officially confirmed on 1 August 2018.

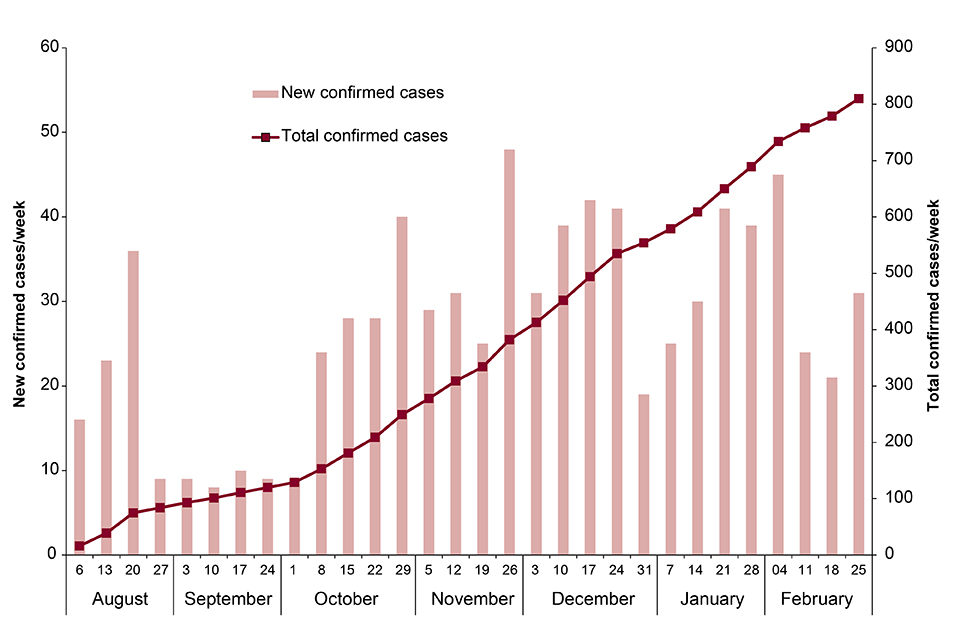

As of 26 February 2019, 814 confirmed and 65 probable cases have been reported in North Kivu and Ituri provinces [1]. Of these, 104 were newly confirmed cases reported between 1 and 26 February. The increase in cases noted during January was not sustained through February. However, recent incidents of unrest have again prevented response activities and case numbers have shown a small increase in the last week (see figure). Since the start of the outbreak, there have been 553 deaths, 88 since the last update.

New and total confirmed cases by week. Data provided by DRC MoH.

During February, the main hotspots of transmission have been the major urban centres of Butembo and Katwa, which together reported 79% (79/104) of the new cases. Of 11 newly identified probable cases, 7 in Katwa and 4 in Komanda, all were historical deaths from November and December 2018.

Overall, 19 health zones have reported cases since August 2018, with one - in Rwampara, Ituri province - reporting cases for the first time during February. Eight health zones have reported cases in the last 21 days. Although the extension southwards into Kayina health zone, a high-security risk area, was of concern when it occurred in January, no further cases have been reported there.

A continuing high proportion (74%) of newly confirmed cases during February were amongst individuals either not known to be contacts of confirmed cases, or contacts not under active monitoring at the time of symptom onset or diagnosis. This is a persistent problem for the response. Together with other important indicators such as the proportion of community deaths, delays in detection and local movement of cases, this suggests a high risk of further chains of transmission in affected communities.

New cases continue to appear in health zones which had not reported cases for some time – Beni had just reached the 21-day milestone, and Mandima had not had a case for ~5 months, indicating the ongoing risk of re-infection while the outbreak is so widespread.

The two Ebola treatment centres in Katwa and Butembo have suffered violent attacks in the last week, which resulted in serious fires and destruction of the sites [3,4]. These two incidents have serious implications for the management of confirmed and suspected cases in these areas [5].

The risk to the UK public remains very low to negligible. The situation is being monitored closely and the risk assessment is regularly reviewed.

Further information sources

- Further PHE advice is available in Ebola virus disease: clinical management and guidance

- NaTHNaC website for travel advice Travel Health Pro website

- WHO website EVD homepage Ebola virus disease

- FCO website DRC advice.

References

- DRC Ministry of Health update, 27 February 2019 (in French).

- DRC Ministry of Health daily updates (in French).

- WHO AFRO update, 26 February 2019.

- CIDRAP news, 27 February 2019.

- WHO Disease Outbreak News update, 28 February 2019

New guidance on investigation of non-infectious disease clusters

PHE has published new guidance for health protection specialists, particularly those in local authorities and PHE, on the investigation of non-infectious disease clusters suspected of having links to environmental exposures [1].

Guidance has previously been published on the investigation of communicable disease clusters (such as Legionnaires’ disease), and special inquiries have been undertaken in the past to consider putative links between cancer incidence in specific geographical areas and environmental exposures (ionising and non-ionising radiation in particular).

The new guidance is the first to present a generic, systematic approach to the investigation of non-infectious disease clusters where it has been suggested that environmental exposure may be implicated. It is primarily intended as a guide for cluster investigation where there is a suspected chemical aetiology, but it may also be relevant where noise, radiation or other environmental hazards are putative causative exposures.

‘Many apparent disease clusters have no cause’, the guidance states. ‘[But in] rare cases, clusters may be related to community-based infections or external sources, eg common environmental exposures …’. Therefore, ‘Investigations of potential clusters should take into account the community’s perception of risk, the potential legal ramifications of reported clusters and the influence of the media’. The core of the guidance describes a three-stage process that takes account of these considerations:

- screening (assessing the need to investigate)

- assessment (statistical analysis and checking for biologic plausibility)

- aetiological investigation (epidemiological studies, for example)

Comments are invited on the first version of the new guidance, including on its practical implementation in the field. [2].

References

- PHE (March 2019). Guidance on non-infectious disease cluster investigation from potential environmental causes.

- Comments can be submitted via Feedback on guidance on non-infectious disease cluster investigation from potential environmental causes.

Infection reports in this issue

This issue includes:

Group A streptococcal infections: first report on seasonal activity, 2018 to 2019.

Laboratory-confirmed cases of measles, rubella and mumps, England: October to December 2018.