Human Rights and Democracy: the 2022 Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office report

Published 13 July 2023

Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Affairs by Command of His Majesty

July 2023

Preface by the Foreign Secretary James Cleverly

Seventy-five years on from the signing of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the UK continues to stand with our partners to secure a stable and peaceful international order. Our resolve to ensure that everyone can enjoy their rights is unwavering.

With Russia waging its brutal war against freedom in Ukraine, we need to take hope from the international community coming together to demand justice. We have shown that actions have consequences and those responsible for human rights violations must pay the price.

As we survey the global human rights landscape in 2022, we should be emboldened by positive developments. Peaceful elections happen because brave individuals have called for change. We welcome every win on the human rights frontier.

But we must not be complacent. The overall trend is still bleak; the world is more volatile and polarised. Authoritarianism is on the rise and unscrupulous actors are working together to weaken agreed international norms.

The UK continues to speak out for truth. We have maximised the impact of all our diplomatic and development tools to protect fundamental freedoms. We make a positive and tangible impact on people’s lives around the globe every day.

The multilateral system is the bedrock of global peace and prosperity. The international human rights institutions are a remarkable force for good. We use our influence in fora such as the UN, Council of Europe and G7 to highlight human rights violations and to galvanise swift action.

In response to the monstrous attack on Ukraine, the UK led efforts to suspend Russia from the Human Rights Council and the Council of Europe. We pressed the UN to establish a Commission of Inquiry, which found that war crimes had been committed in Ukraine, and referred Russia to the International Criminal Court.

In Iran, there are reports of more than 22,000 people detained, including children. There are harrowing reports of torture and abuse in regime prisons. Iran’s crackdown on protestors led to over 500 deaths, including 70 children. We will not shirk our responsibility to ensure the guilty are held accountable. In concert with our partners, we have coordinated sanctions on Iranian officials.

With violent conflict continuing to devastate the lives of innocent Sudanese people, the UK is working with our international partners to support the path to lasting and genuine peace. We continue to support the Sudanese in their path to democracy. Those who have committed human rights abuses must be held to account.

Stepping up our life saving humanitarian work is one of the themes of our International Development Strategy. We prioritise those in greatest need to prevent the worst forms of human suffering and drive a more effective international response to humanitarian crises. It is no coincidence that this is often in countries with bitter human rights crises, such as Afghanistan and Yemen.

We know the changing context means we have to go further and faster to reinvigorate progress on the Sustainable Development Goals, as set out in the Integrated Review Refresh. We are delivering reliable investment through up to £8 billion of UK-backed financing a year by 2025, while helping to build a bigger, better and fairer international financial system that rises to meet development challenges. We provide countries with the means needed to lift themselves out of poverty. We help them build accountable, effective and inclusive state institutions that seek to protect the human rights of their whole population.

Women and girls should be free to reach their full potential. We will not tolerate efforts to reverse hard-won gains on gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls. Our new Women and Girls Strategy shows how we are building a global network of partners committed to progressing gender equality. Women and girls will remain firmly at the centre of the FCDO’s operations and investments. We will always strive to amplify their voice.

The report details some encouraging progress in many countries on LGBT+ rights, but it also identifies where many others are slipping backwards. The UK Government respects that all countries are on their own path. However, we will continue to stand against prejudice and support LGBT+ communities in the face of discrimination, as we have by co-chairing the Equal Rights Coalition with Argentina for 3 years, and we will continue to play a key role in its work.

We are proud of the UK’s heritage and culture on human rights and democracy. But no country has all the answers to these global challenges. Every country can and must improve. We will continue to engage others with humility about our ongoing journey on these issues.

We will continue to work with old allies and new friends to make the vision of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights a reality.

When we work together, we see justice served. And we can give every person the freedom to thrive and prosper.

Foreword by the Minister for Human Rights, Lord Ahmad of Wimbledon

In the aftermath of the Second World War, countries came together vowing that such atrocities should never happen again. From that global exercise, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was born.

Over the subsequent decades, countries have worked together to strengthen the world’s human rights architecture through a collection of agreements that guarantee the rights of every individual.

However, as we detail in this 2022 Annual Human Rights and Democracy Report, for far too many people, the hatred, depravity and atrocities of the Second World War have not been consigned to history. Too many repressive governments have chosen to disregard their international commitments, and rule through discrimination, persecution and violence.

The UK Government holds an unwavering conviction that the human rights of every person still matter. Our Annual Report details how we are working with our allies to stand up for the marginalised and repressed across the full range of our human rights work.

Turning to 2022, I wanted to highlight some key aspects of our work and programmes. As the Prime Minister’s Special Representative on Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict, I am particularly proud of what we have achieved in 2022. We hosted a landmark international conference to intensify global action and signal our sustained resolve to tackle these crimes. During the last 6 years, I have been determined to ensure survivors are at the heart of our approach, as such, survivors were central to our conference and led discussions across all areas. The UK also announced our new 3-year strategy, backed by up to £12.5 million of new funding that will help save and rebuild countless lives. We also formally launched the Murad Code at the UN Security Council to advance the interests of survivors.

I would like specially to thank Kolbassia Haoussou and Nadine Tunasi; 2 courageous survivors for their support and engagement.

In October, I visited the Democratic Republic of the Congo, together with HRH The Duchess of Edinburgh, who has also inspired so many through her direct engagement, campaigning and commitment to preventing sexual violence in conflict. During our visit, we met with our dear friend, Nobel laureate, Dr Denis Mukwage, who through his courageous and exemplary leadership at the Panzi Hospital has helped survivors to rebuild their lives, both physically and through providing vital emotional support and mental health provisions.

We also witnessed the vital efforts of TRIAL International to enhance survivor access to justice, and the far-reaching impact of UK funded support to survivors, delivered by the Global Survivors Fund.

In relation to media freedom, the UK Government has also continued to focus on the importance of protecting journalists and media organisations as a key pillar of the human rights infrastructure. The media freedom coalition we launched with Canada in 2019 welcomed Norway and Sweden into its membership, and I was pleased to attend the meeting of the coalition in Estonia.

Turning to Freedom of Religion or Belief, in July I was honoured to host the 3rd International Ministerial Conference in London. Around 50 countries attended the conference to coordinate and strengthen global action, which again demonstrated the UK’s strong leadership on this important and fundamental human rights issue.

We also continue to focus on and implement the recommendations of the Truro Report to ensure the FCDO’s architecture is aligned to deliver, and coordinate with my friend and colleague, Fiona Bruce MP, the UK FoRB Envoy, in her role as Chair of the International Freedom of Religion or Belief Alliance.

The UK has demonstrated its commitment and focus on human rights across the world. The 2 conferences we convened in 2022 also reflected our ability to pull together not just governments, but civil society, leaders, and survivors to strengthen our collective responses.

Across the full range of human rights, when discrimination is not identified and addressed, we often witness marginalisation, persecution, worse still, violence and attacks on individuals and communities. Therefore, it is important to act.

We should also acknowledge and recognise that different countries move at different speeds. Some face quite unique challenges. I believe we should be cognisant of where progress is being made and, as a constructive partner, lean in and share expertise and insight in order to accelerate further progress. There are occasions where I have seen private, effective, diplomacy unlock issues and cases. There are of course other times where through collaboration, and collective and public action, we have called out the most serious human rights violations.

Whatever the approach or the issue, and accepting that protecting and strengthening human rights poses difficult challenges, we can affect change through our advocacy and perseverance. Ultimately, if our work leads to changing the trajectory for the better for the lives of individuals and communities, then it’s worth every second of our time.

Chapter 1: Democracy

Democracy and democratic freedoms

The UK supports a rules-based open international order, a world where democracy and freedoms grow and where autocracy is challenged. As Prime Minister Rishi Sunak said “We’re a country that stands up for our values…that defends democracy by actions not just words.” [footnote 1]

However, 2022 saw ongoing authoritarian practices challenging the international order, and continuing the global decline in democratic freedoms. The NGO Freedom House [footnote 2] recorded that global freedom had declined for the 17th consecutive year.

Throughout 2022, the UK continued to deliver on the Integrated Review commitment to “increase our efforts to protect open societies and democratic values where they [were] being undermined”. As the Foreign Secretary set out in his speech on Human Rights Day in December 2022,[footnote 3] transparent, democratic governance is in the interests of all people, all economies and the long-term stability of every nation.

The UK took action to strengthen and protect democracy and freedom around the world, including through its policy and programme work on democratic governance, and through its funding of the Westminster Foundation for Democracy which uses expertise to support people around the world to strengthen democracy in their communities. Much of this work involves engagement with civil society partners on issues including elections, transparency and open government, women’s political empowerment and digital democracy.

The UK worked with partners through the German G7 Presidency to underscore the enduring importance of democratic values. This culminated in the 2022 Resilient Democracies Statement, which was strongly supported by the UK, and built on the outcomes of the UK G7 Presidency in 2021 and its focus on open societies and democracy.

The UK is committed to taking a long-term approach to addressing the causes of democratic decline and to championing democratic governance. The Government’s Strategy for International Development,[footnote 4] published in May, outlines this patient approach to development which affirms our support to freedom and democracy and the effective institutions which underpin development.

In light of the potential risks posed by authoritarianism, the UK launched a Ministerial Taskforce on Defending Democracy in November. This taskforce will look at foreign threats to our elections and electoral processes; disinformation; physical and cyber threats to our democratic institutions and those who represent them; foreign interference in public office, political parties and universities; and transnational repression in the UK.

Digital democracy

Increasingly, people exercise their rights, access and share information, express views and hold governments to account in the digital and online space. The UK worked with international partners to strengthen international norms around human rights and fundamental freedoms in the digital age and to reinforce support for a free, open, interoperable, secure and pluralistic internet that enables inclusive participation in democracy and where people can exercise their human rights. This included the UK’s active membership of the Freedom Online Coalition (FOC), in which the UK contributed to the Ottawa Agenda, a new set of recommendations for the promotion of internet freedom in the next decade.[footnote 5]

Countering politically motivated internet shutdowns and restrictions was a key priority. There were 187 internet shutdowns across 35 countries in 2022.[footnote 6] The UK joined the FOC Taskforce on Internet Shutdowns. At RightsCon and the United Nations (UN) Internet Governance Forum, the UK brought together countries, industry and the private sector to explore ways to address the challenges. The UK is proud to be chairing the FOC Taskforce on Internet Shutdowns in 2023, alongside the NGOs Access Now and the Global Network Initiative.

In October, the FOC issued a joint statement condemning the measures undertaken by Iran to restrict access to the internet following nationwide protests over the killing of Mahsa Amini. This was the first FOC statement to focus on shutdowns and restrictions in just one country, and the UK pushed hard for it to be approved by consensus, in order to set an important precedent.

At the Tallinn Digital Summit in October, with Estonia and NGO Access Now, the UK publicly launched its Technology for Democracy Cohort as part of the US-led second Summit for Democracy process. This brought together over 150 civil society, government and private sector participants to work on 3 priority areas: internet shutdowns and restrictions; emerging technology and democracy, and technology for good governance.

On 4 November, the UK announced that it would host the annual UNESCO celebration on the importance of universal access to information in 2023, which will focus on the important nexus between internet connectivity and access to information, both of which are essential to the free flow of information and exercise of rights online.

In 2023, the UK will continue to champion digital democracy as part of its work to support healthy information ecosystems. The UK will advocate for a global internet that is open to all, and for human rights and fundamental freedoms to be at the centre of the development and use of digital technologies. Working with international partners, the UK will address internet shutdowns and restrictions through co-chairing of the FOC Taskforce on Internet Shutdowns, co-leadership of the Technology for Democracy Cohort, and through multilateral fora including the G7 and UN Internet Governance Forum. The UK will also continue to work actively with its partners in the Council of Europe on the development of a new treaty on artificial intelligence and human rights, democracy and the rule of law.

Elections

Democratic and open societies cannot flourish without credible and inclusive elections. Elections are a key test of a functioning democracy. They enable voters to hold those in public office to account. The UK helped to support democracy by providing assistance to electoral processes.

Kenya elections, August 2022

UK support began early in the election cycle and included ODA spend of £7.5 million over 2-and-a-half-years through the Kenya Elections Support Programme. Technical assistance to the Independent Elections and Boundary Commission helped it improve elections planning, management, and strategic communications. Training for the judiciary focussed on dispute resolution processes, while support to police and security services was designed to improve training, organisation, operating procedures, and inter-agency cooperation.

In addition to these programmatic interventions, the UK pursued a busy and proactive diplomatic effort, both bilaterally and in concert with the wider international community. The UK took a lead role coordinating donor activities and messaging, encouraging both presidential candidates and their supporters to engage constructively in the electoral process and respect the rule of law. As election day approached, the UK team on the ground supported monitoring activities in constituencies across the country and in the central tallying centre.

Election day was largely peaceful. On 15 August, William Ruto was announced as the winner of the presidential race, a result which was subsequently challenged by his opponent, Raila Odinga. The Supreme Court upheld the result, rejecting all the claims put forward as justification for nullifying the result.

Despite a highly contested presidential election, both domestic and international observation missions highlighted some significant improvements in process. Long-term, tailored and effective UK technical support and political engagement contributed to this. However, the most impressive contribution came from the Kenyan people themselves in their commitment to, and respect for, a peaceful democratic process.

Staff from the British High Commission in Nairobi talking to Kenyan security officers on election day in August.

Election observation helps support strong, transparent and accountable political processes and institutions overseas. The UK continued to support election observation missions run by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). In the course of the year, the UK funded observers to OSCE missions in Hungary, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kazakhstan.

Parliamentary elections were held in Bahrain in 2022 and were monitored by Bahrain-based civil society groups. The elections were peaceful and orderly, with an increased turnout and proportion of elected women MPs and representatives from across society. However, no international observers were allowed, and the UK continues to encourage Bahrain to consider inviting observers for future elections. Some political societies also remained banned, leading to criticism from international rights groups that there was a continuing “environment of political repression”.

Community of Democracies

The Community of Democracies (CoD) was established in 2000. Its founding document, the Warsaw Declaration, defines the essential practices and norms for the effective establishment of democracy, and emphasises the interdependence between peace, development, human rights and democracy. The Governing Council comprises 28 Member states including Canada, Chile, India, Mexico, Morocco, Nigeria, the Republic of Korea and the USA. Member states commit to abide by the common democratic values and standards outlined in the Warsaw Declaration, and to make tangible contributions to strengthening the Community of Democracies.

On 17 November 2022, the UK and a number of other Governing Council Member states, including Argentina, Canada, Estonia, Finland, the Republic of Korea and the USA, supported a CoD statement expressing solidarity with the people of Iran, especially women, protesting against oppression by the Iranian authorities, including gender-based discrimination, human rights violations and abuses, and disproportionate use of force.

In November, the Minister for Human Rights, Lord (Tariq) Ahmad of Wimbledon, confirmed to the CoD that the UK wished to renew its membership of the organisation’s Governing Council. He reaffirmed the UK’s commitment to working with the other 27 participating states and to the democratic values and standards outlined in the Warsaw Declaration. The UK’s membership is an important platform to support its Integrated Review commitment to democratic values.

The UK will continue to work with other member states and the CoD civil society pillar, the International Steering Committee, to support and strengthen democracy worldwide and to speak out where democracy and civil society are repressed.

Westminster Foundation for Democracy

The Westminster Foundation for Democracy (WFD) is the UK public body dedicated to strengthening democracy overseas. It is an arms-length body funded by, but operating independently from, the FCDO who provided £6.5 million grant-in-aid in FY2022 to 2023. Last year was WFD’s 30th anniversary, and it continued to work with parliaments, political parties, electoral bodies, and civil society in over 40 countries and territories to build inclusion, accountability, and stronger democratic practices.

WFD contributed to tackling both the climate crisis and rising authoritarianism around the world. WFD helped to advance crucial climate change legislation in Indonesia and Georgia. It developed tools that assisted parliaments to scrutinise policy decisions on public debt, including work with county assemblies in Kenya and in the Solomon Islands on financial oversight and scrutiny. Its work to support the Verkhovna Rada (Supreme Council) of Ukraine has continued throughout the Russian invasion.

WFD continued its work to protect the vulnerable and marginalised. Its campaign to eradicate violence against women in politics in Montenegro reached more than 2-thirds of the population. Through its Global Equality Project, WFD also worked with local partners to help ensure the protection of the rights of LGBT+ people, women, girls, and other individuals belonging to marginalised groups, through reforms in policy and legislation.

WFD’s work to support electoral systems and processes around the world included analysis of and/or support for elections in Kenya, Sri Lanka, the Philippines, the Occupied Palestinian Territories and Nepal. WFD recruited election observers for observation missions to Serbia, Hungary, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kazakhstan. Additionally, following WFD support, Sierra Leone’s parliament topped the Open Parliament Index on public accountability in West Africa.

The Speaker of parliament opening the Civil Society Office in the parliament of Sierra Leone, with support from WFD.

WFD also worked with Indonesia in holding the Bali Democracy Forum, with a particular focus on civil society engagement. The FCDO also attended at senior official level as part of the UK’s overall efforts to support regional democracy initiatives and underscore the universality of democratic values.

Women’s political empowerment

Women and girls have the right to participate in political and civic processes without discrimination of any kind. Women’s and girls’ political empowerment is critical to, and a key indicator of, a peaceful, prosperous and democratic society.

The UK’s International Development Strategy calls for a world where all girls and women will be empowered to have voice, choice and control over their lives, free from the threat of violence. The UK’s International Women & Girls Strategy, due to be published in 2023, will put women and girls at the heart of the UK’s work, and will recognise the importance of women’s leadership, perspectives and knowledge, local, national and global progress.

Throughout 2022, the FCDO supported the political empowerment of women around the world. This included commissioning a local organisation to monitor hate speech and cyberbullying against female candidates standing in parliamentary elections in Zambia.

Through WFD, the UK supported female MPs in Nepal to scrutinise legislation and represent their constituencies more effectively, including supporting women parliamentarians in their efforts to advance a motion requiring a 50/50 gender balance in all candidate lists. The UK also worked with women MPs in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao in the Philippines to develop gender responsive budgets, including within Covid recovery plans, and helped women legislators in Morocco to advance their parliament’s use of gender analysis.

UK programming on women’s political empowerment in Malaysia

In Malaysia, the British High Commission in Kuala Lumpur funded a project to support budget equity and gender equality. The project facilitated training, networking opportunities and resources for parliamentarians, ministry officials and women’s rights organisations from across 7 countries to strategically advocate for and enact measures to achieve gender-responsive budgeting. Programme participants identified priorities, including increasing decision makers’ use of sex disaggregated data. This led to practical outcomes such as a redrafted gender data toolkit to support Malaysian ministries engaged in budgeting.

In March, the UK joined the Global Partnership for Action on Online Gender-based Harassment and Abuse. The UK worked with others to understand better what works to address the growing problem of technology facilitated gender-based violence and will report on progress at the US-led Summit for Democracy in March 2023.

Looking ahead to 2023, the UK will begin implementation of its Women and Girls Strategy. This will include amplifying the work of diverse grassroots women’s organisations and movements, championing their role as critical agents for change, and strengthening the political, economic and social systems that play a critical role in protecting and empowering women and girls.

Chapter 2: Equality, gender and inclusion

Gender equality

Women’s and girls’ rights

In 2022, the UK continued to champion gender equality and stand firm in the face of systematic attempts by regressive actors to roll back on women’s and girls’ rights.

The UK used its membership of the UN Human Rights Council and other multilateral bodies to promote women’s and girls’ rights and the broader equalities agenda. This included advocating for comprehensive sexual and reproductive health and rights, the protection of LGBT+ rights, girls’ education and ending all forms of violence and discrimination against women and girls in particular. The UK made use of its diplomatic influence and convening power to increase international support for women’s rights and gender equality. For example, in September 2022, former Minister of State for Development, Vicky Ford, spoke at the launch of the Alliance for Feminist Movements, where she endorsed the critical role of women’s rights organisations in tackling global issues.

To celebrate International Day of the Girl on 11 October, the FCDO hosted a high-level reception alongside the Latvian Ambassador to the UK, Ivita Burmistre, to showcase the commitment the FCDO places on the empowerment and protection of girls. At the event, Ambassadors, High Commissioners and Chargés d’Affaires were accompanied by young women, chosen from a range of backgrounds from across the UK, who acted as ‘Ambassadors for the Day’. This initiative gives girls aged 19 to 29 the opportunity to accompany an Ambassador for a day, in order to promote female leadership and empowerment in young women. British Embassies across the world took part in this initiative, including in Brazil, Denmark, Lebanon and Turkey.

The FCDO hosted a reception to celebrate International Day of the Girl in October 2022, where former Minister of State for Development, Vicky Ford, the Latvian Ambassador and HRH Princess Beatrice provided remarks.

In 2023, the FCDO will publish the UK’s first International Women and Girls Strategy which will reflect the Government’s commitment to use all its combined levers to stand up for women and girls. The UK is clear that women and girls should face no constraints on realising their full potential. They should have control over their own bodies and control their own choices.

Ending violence against women and girls

Violence against women and girls (VAWG) is rooted in gender inequality and sustained by the harmful social norms that uphold unequal power dynamics within society. Data and research suggest that the prevalence and magnitude of VAWG has remained largely unchanged over the last decade and, in some contexts, is worsening due to conflict, the impacts of climate change and food insecurity.[footnote 7]

The UK takes a long-term approach that builds strong and resilient women’s rights organisations that can prevent and respond to gender-based violence both in times of peace and conflict.

Alicia Herbert OBE, Special Envoy for Gender Equality, visiting the Council of Europe in December 2022 to mark the UK ratifying the Istanbul Convention.

In 2022, the UK used its position in multilateral fora to uphold protections on ending violence towards women and girls. The UK ratified both the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women (Istanbul Convention) and the International Labour Organisation’s Convention C190 on violence and harassment in the world of work. In July, the UK co-sponsored the Canadian-led UN Human Rights Council resolution renewing the mandate of the Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women, which expanded it to include girls.

In Mongolia, the UK’s contribution to the UN Trust Fund to End Violence Against Women has helped support women’s rights organisations to provide disability-inclusive services to survivors of intimate partner violence.

The FCDO has supported projects around the world, including providing £7.3 million to the Stopping Abuse and Female Exploitation programme in Zimbabwe. The programme continued to devise a cost-effective and scalable intervention to reduce and respond to VAWG and reach those at greatest risk, including women with disabilities. The UK also supported the Golees Foundation in Costa Rica, which works to empower young women and girls from vulnerable communities through social transformation projects.

The UK’s Global Ambassador for Human Rights, Rita French, meeting with the Golees Foundation in Costa Rica, November 2022.

In March 2022, the UK became a founding member of the Global Partnership for Action on Gender-based Online Abuse and Harassment, to drive forward solutions to address and prevent the growing scourge of technology-facilitated gender-based violence, in collaboration with other likeminded actors.

Tackling gender-based violence will remain a priority for the UK’s work overseas. In 2023 the UK will continue to support and amplify the work of women’s rights organisations to prevent and respond to this violence around the world.

Helen Grant MP, the Prime Minister’s Special Envoy for Girls’ Education, and Alicia Herbert OBE, Special Envoy for Gender Equality, visiting South Sudan in February. They met with activists who use art to illustrate the impacts of gender-based violence on women and girls.

Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict initiative

The global scale of conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) is appalling. The international community has made progress, but sexual violence continues in conflict-affected areas on a shocking scale, and impunity has continued to be the norm for perpetrators. The UK is a global leader on action to tackle CRSV, which is a key government priority. The UK has committed £60 million to PSVI since it was launched in 2012.

The UK has worked closely with the government of Ukraine to respond to reports of CRSV committed by Russian forces. This has included deploying UK experts to support the Office of the Prosecutor General’s CRSV strategy, war crimes training for prosecutors, police and judges, and procuring 30,000 kits to enable forensic examination of CRSV cases.

The Murad Code

In April 2022, the Prime Minister’s Special Representative on Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict and Minister for Human Rights, Lord (Tariq) Ahmad of Wimbledon, jointly launched the Murad Code at the UN Security Council with Nadia Murad, a Yazidi human rights activist and CRSV survivor. The Murad Code – developed by the Institute for International Criminal Investigations – is a code of conduct for documenting the experiences of CRSV survivors ethically and effectively. It has been translated into Ukrainian, as well as other languages.

In Colombia, UK funding supported the All Survivors Project to advocate successfully for the Special Jurisdiction for Peace to open a macro-case into CRSV committed by armed groups and government forces that recognises men and children as victims as well as women. This was an important step in the transitional justice process that will strengthen accountability for CRSV in Colombia.

In December, the UK introduced sanctions which included 18 designations targeting individuals involved in violations and abuses of human rights, 6 of whom were perpetrators responsible for conflict-related sexual violence and related crimes, from Mali, Myanmar and South Sudan. The UK will continue to build on this in 2023 and demonstrate a commitment to take action against those that seek to supress women or use sexual violence as a weapon of war.

Lord (Tariq) Ahmad and HRH Duchess of Edinburgh during their visit to the DRC in October.

In October, Lord (Tariq) Ahmad accompanied Her Royal Highness, the Duchess of Edinburgh, on a visit to the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The visit raised awareness of the need to address sexual violence in conflict and gain a practical insight into experiences of tackling it. This visit was part of Her Royal Highness’ long-standing commitment to championing PSVI.

Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative Conference

From 28 to 29 November 2022, the UK hosted the international Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative (PSVI) Conference in London. Over 1,000 delegates attended, including survivors, civil society, multilateral partners and representatives from at least 57 countries. Following the launch of PSVI 10 years ago, the conference and its headline initiatives set out below sent a strong message of sustained international resolve to tackle this global scourge.

-

the UK launched a new Political Declaration which clearly signals that these heinous crimes must end and outlines the steps needed to achieve this. The Political Declaration was endorsed by 53 countries and the Special Representative of the Secretary-General Patten, with 40 countries making national commitments detailing the tangible actions they will take to tackle CRSV

-

the Foreign Secretary launched the UK’s new PSVI Strategy, backed by up to £12.5 million of new funding, which includes up to £8.6 million for a new initiative on survivor-centred accountability - “ACT for Survivors”. The strategy focuses on what the UK will do to deliver a strengthened global response, prevent sexual violence in conflict, promote justice, and support survivors. It outlines the UK’s ambition to use diplomacy, development and defence levers to tackle these appalling crimes

-

ahead of the conference, the Foreign Secretary announced a further £3.45 million for the UN Population Fund, to boost survivor centred gender-based violence and sexual and reproductive health services in Ukraine and the nearby region, and to ensure continued access to expert support for survivors of sexual assault

-

Lord (Tariq) Ahmad launched a new partnership between the UK and the International Criminal Court to explore how new technologies, such as virtual reality, could help to address some of the challenges faced by CRSV survivors when seeking justice. This could include a virtual reality introduction to the courtroom to help survivors familiarise themselves with the setting, reducing stress and managing expectations

-

Lord (Tariq) Ahmad also launched a Platform for Action Promoting the Rights and Wellbeing of Children Born of CRSV – a framework outlining steps the UK and partners will take to empower this vulnerable group. For example, the Democratic Republic of the Congo committed to review its laws, policies and practices to understand how it could help children born of CRSV, while the UK committed to use a PSVI team of experts to support this review

-

to help maintain the momentum generated by the conference, the UK launched an International Alliance on PSVI, comprised of governments, civil society and survivors. This will be a key forum for coordinating international action to prevent and respond to CRSV. The International Alliance, which has 20 members, has UN support. The Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict will participate in Alliance meetings and UN Women have confirmed their membership

-

a side event on The Declaration of Humanity by Leaders of Faith and Leaders of Belief helped to drive the total number of signatories to the Declaration to 766. This UK initiative unites multiple faiths in a commitment to work within their communities to denounce CRSV and tackle the stigma faced by survivors. Signatories include faith leaders, NGOs and civil society actors in countries including Iraq, Kosovo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and The Vatican

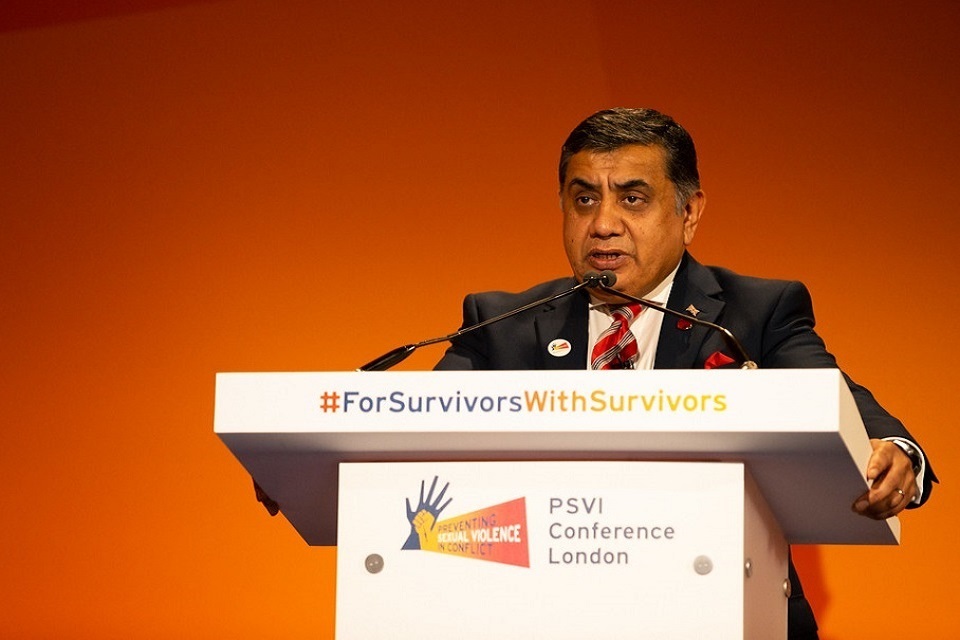

Lord (Tariq) Ahmad speaking at the PSVI Conference.

The Foreign Secretary, James Cleverly, meeting with Olena Zelenska, First Lady of Ukraine at the PSVI Conference.

HRH The Duchess of Edinburgh talking with Dr Denis Mukwege at the PSVI Conference.

Sexual exploitation and abuse and sexual harassment

The FCDO is focused on safeguarding against sexual exploitation and abuse and sexual harassment (SEAH) in the international aid sector. The UK’s goal is to ensure all those involved in poverty reduction take all reasonable steps to prevent harm, particularly SEAH, from occurring; listen to those who are affected; respond sensitively but robustly when harm or allegations of harm occur; and learn from every case. The UK strategy on safeguarding against SEAH in the aid sector sets out the detail of this goal, and how the UK will realise it [footnote 8].

Many of the actions the UK took to safeguard people against SEAH are captured in the 2021 to 2022 FCDO Progress Report on Safeguarding Against SEAH in the International Aid Sector.[footnote 9] This included funding programmes to prevent and improve the response to SEAH.

The UK trained specialised investigators through the Investigations Qualification Training Scheme and made it easier to take action against perpetrators through Project Soteria.[footnote 10]

The UK also built the capacity of hundreds of organisations through the Safeguarding Resource and Support Hub and funded international bodies and local women’s rights organisations to provide support to hundreds of survivors and victims of SEAH.[footnote 11]

The FCDO continued to convene international stakeholders who made commitments at the 2018 Safeguarding Summit, including donors, multilateral, civil society and private sector representatives, to track, discuss and report on progress through quarterly meetings and the cross-sector annual progress report.[footnote 12]

The UK continued to advocate for Peacekeeping Mission mandates to contain language on sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA). Throughout all renewals, the UK worked with partners to successfully maintain SEA text. The Ministry of Defence introduced a new policy,[footnote 13] supported by an awareness raising and training campaign, to direct efforts to prevent and address sexual exploitation or abuse by service personnel and civilian employees conducting defence activity. The policy outlines appropriate assistance and redress available to victims and includes a prohibition on transactional sex at all times when conducting defence activity outside of the UK.

The UK will continue to work in partnership with others to develop a Global Framework for Preventing and Responding to SEAH in development and peacekeeping. The UK will use its diplomatic levers and programmes to drive up standards, from investigative capacity to recruitment in the aid sector. Internally, the UK will continue to build capability of staff and partners.

Female genital mutilation

Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) is one of the most extreme manifestations of gender inequality. It is a human rights violation that can result in a lifetime of physical, psychological and emotional suffering.

In 2022, continued UK support to the Africa-Led Movement to End FGM included engagement with communities in Kenya, and expansion into Senegal, Ethiopia and Somalia to provide a safe space and platform to speak about FGM and rights violations - an important step towards changing behaviours on FGM at the local level. This included engaging men in community dialogues and facilitating boys’ and girls’ clubs in schools to discuss these issues which has already resulted in a shift in attitude in these communities in Kenya. UK support also helped grassroots organisations who are leading advocacy efforts, to champion women’s rights around FGM. The UK funded a study by the World Health Organisation that highlighted the health and economic costs of FGM, which was published in the BMJ.[footnote 14]

The UK also continued programme work to end FGM in Sudan and supported the UN Joint Programme on the Elimination of FGM to help countries develop costed plans for ending FGM for example in Eritrea.

Ending FGM remains a priority for the UK and is a key component of the FCDO‘s Women and Girls Strategy. The UK will continue to support and amplify the work of grassroots organisations and local champions who are leading the fight to end FGM in their communities.

Women, peace and security

In line with the objectives in the UK’s Women, Peace and Security (WPS) 2018 to 2022 National Action Plan (NAP),[footnote 15] the UK continued to focus on promoting women’s full, equal and meaningful participation in peace processes.

In Afghanistan, the UK continued to raise the rights of women and girls in its political engagement with the Taliban. The UK provided platforms for Afghan women to speak out, including a roundtable hosted by Lord (Tariq) Ahmad, to advocate for their full inclusion in society.

In Ukraine, as part of the UK’s £220 million of humanitarian assistance and longer-term development programming, the UK worked to prioritise protection and inclusion of the most vulnerable - particularly women, girls and marginalised groups at increased risk of abuse, neglect and violence.

The UK’s 2023 to 2027 National Action Plan includes a gendered approach to the way the UK tackles transnational threats[footnote 16] and the use of new technologies and digital spaces by belligerent actors. It also has a gendered approach to climate insecurity.

Educating girls

The UK continued to stand up for the right of every girl to achieve 12 years of quality education. The UK focused on reaching the most marginalised children, including girls, those with disabilities, and those in crises, and advocated for the universal endorsement of the Safe Schools Declaration.[footnote 17]

The UK continued to champion the global objectives of 40 million more girls in education and 20 million more reading by age 10, by 2026. In 2022, the UK funded a baseline report to monitor progress and highlight challenges in respect of the G7 Global Objectives on Girls’ Education.[footnote 18] The UK’s Girls’ Education Challenge programme supported up to 1.6 million marginalised girls across 17 countries.

The Prime Minister’s Special Envoy for Girls’ Education, Helen Grant OBE MP, continued to champion the right for every girl to have access to 12 years of quality education, through her engagement with governments, civil society, young people, and parliamentarians in the UK and abroad.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has disrupted the education of 5.7 million children, disproportionately impacting girls and marginalised groups such as children with disabilities. The UK is providing £15 million to the UNICEF Ukraine Humanitarian Action for Children Appeal, which has engaged 1.45 million children in formal or non-formal education. UK funding to the global education in emergencies fund, Education Cannot Wait, has supported over 150,000 Ukrainian children to access education and psychosocial support. In partnership with Poland, the UK is also providing £20 million to Ukrainian refugees displaced to Poland - 90% of whom are women and children - including for education.

The UK continued to lobby the Taliban to reverse the decision to ban women and girls from accessing secondary and tertiary education and banning female NGO workers from delivering education in Afghanistan.

During the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative Conference in November, the UK highlighted the role of education in preventing conflict-related sexual violence and supporting survivors. The UK also endorsed the Freetown Manifesto, which commits to accelerating support for education systems to become gender equal. The Freetown Manifesto was launched under the auspices of the Gender at the Centre Initiative (GCI) which the UK funds and continues to support.

The UK will continue to champion gender equality in and through education, increasing political will and momentum around this agenda and developing the evidence base of what works.

Gender and climate change

The UK remained committed to advancing gender equality and social inclusion within international climate and nature action. Women and girls in all their diversity often experience the greatest impacts of climate change and biodiversity loss, which amplifies existing gender and other social inequalities and can undermine the enjoyment of human rights.

The UK took an inclusive approach to its COP26 Presidency. It promoted the implementation of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change Gender Action Plan and the Glasgow Climate Pact, to ensure gender-responsive implementation and the full, equal and meaningful participation of women in climate action. At the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP15), the UK committed to ensure gender equality through the implementation of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and agreed a comprehensive Gender Plan of Action.

People with disabilities, especially women and girls with disabilities, are more likely to be impacted by climate change. The UK is committed to disability inclusive climate action amongst other thematic areas, through the FCDO’s Disability Inclusion and Rights Strategy.[footnote 19] In 2022, the UK also set out a new framework of priority actions to build school systems that are more resilient to climate and environmental changes, and to ensure that children have the knowledge, skills, and agency to support climate action. [footnote 20]

The UK will continue to champion gender-responsive climate and nature action, amplifying the voices of those whose views are often the most marginalised, and empowering them as decision-makers, advocates and leaders.

Women’s economic empowerment

The UK supports women’s economic empowerment throughout its economic development and social protection portfolio. In 2022, the UK supported women working in global value chains into safer, more sustainable and productive work through the Work and Opportunities for Women (WOW) programme. The UK increased women’s access to, and control over, income, assets, savings and decision-making through its social protection programmes.

In the International Development Strategy, the UK announced a new Green and Inclusive Growth Centre of Expertise. This will be the hub for UK technical expertise and policy advice on women’s economic empowerment. It complements the investments made by the UK’s development finance institution, British International Investment, which has committed to at least 25% of all new investments under its current strategy period from 2022 to 2026 having a gender lens, in line with the ‘2X Challenge’.

As part of the innovative multi-donor Private Infrastructure Development Group, the UK has committed to adopting a deliberate gender lens in all its infrastructure investments. In 2022, FCDO funding to the Financial Sector Deepening Africa (FSD Africa) development agency resulted in the first ever gender bond being listed on an exchange in Africa. UK funding to FSD Africa also contributed to the April 2022 issuance of NMB Bank’s £25 million Jasiri gender bond in Tanzania, raising funds for women-owned micro, medium and small enterprises.

Rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people

The UK is proud to champion the human rights and dignity of all lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT+) people, irrespective of their sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or variations in sex characteristics.

In 2022, many countries continued to make progress on the implementation of human rights compliant laws and policies that protect LGBT+ people from violence and discrimination. Four countries, Antigua and Barbuda, St Kitts and Nevis, Singapore and Barbados, announced measures to decriminalise consensual same-sex relationships. Several countries, including Cuba, Slovenia and Mexico, extended marriage to same-sex couples. Kenya also introduced new laws aimed at recognising and protecting intersex people.

While many countries took steps to improve human rights and equality, there was a concerning rise in violence or discrimination against LGBT+ people. Several countries have taken regressive steps that will violate the human rights and freedoms of LGBT+ people.

In Russia, the government has sought to violate, suppress and deny the human rights of individuals by implementing new legislation to broaden “anti-propaganda” laws which undermine the freedom of expression of all Russians, particularly those who are LGBT+. In countries such as Ghana, and latterly Uganda, rising homophobic rhetoric has been used by parliamentarians to justify “anti-gay bills” that would violate human rights and undermine freedoms. In Indonesia, legislation restricting the rights of unmarried persons is likely to have a disproportionate impact on LGBT+ people, effectively criminalising same-sex relationships.

In every corner of the world, particularly where freedoms are under threat, LGBT+ communities often become one of the key targets. Increased attempts by state and non-state actors to undermine social attitudes towards LGBT+ people have corresponded with a significant rise in anti-LGBT+ hate crime, including the horrific attacks on LGBT+ people in Norway (Oslo), Slovakia (Bratislava) and the USA (Colorado Springs).

In 2022, the UK continued to play an important role in defending the human rights and freedoms of LGBT+ people around the world. While much of this work was through discreet diplomacy, UK diplomatic missions have continued to visibly demonstrate their support around key dates, such as the International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia and Transphobia, local Pride events, and international events such as the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in June.

At the Human Rights Council in June, the UK Mission, together with its Equal Rights Coalition partners, co-hosted the first-ever Pride event at the UN with over 100 States and numerous civil society organisations present. The UK worked closely with colleagues from Latin America, and other regions, who spearheaded the mandate renewal of the UN Independent Expert on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in June.

The UN in Geneva held its first-ever Pride event in June 2022, co-hosted by the UK Mission.

The UK also worked with local stakeholders to give visibility to LGBT+ issues. The British Embassy in Brasilia collaborated with NGO ABGLT to gather data on LGBT+ human rights defenders in Brazil and the challenges they face,[footnote 21] in order to strengthen support networks for the defenders. The project generated data in areas where there is little information at a national and regional level and will also support possible follow up projects and increase the UK’s profile on LGBT+ rights in Brazil.

The Prime Minister’s Special Envoy for LGBT+ rights, Lord Herbert of South Downs, has continued to strengthen UK cooperation on LGBT+ rights through his engagement with governments, civil society and parliamentarians. This has included co-hosting the Council of Europe’s European LGBTI Focal Points Conference with Cyprus, attending the joint Warsaw and Kyiv Pride in Poland, and visiting Germany and Argentina to strengthen cooperation within the Equal Rights Coalition.

The Prime Minister’s Special Envoy for LGBT+ Rights, Lord Herbert of South Downs, attending joint Warsaw-Kyiv Pride in June 2022.

The UK continued to work closely with likeminded countries to promote the inclusion of LGBT+ people in multilateral fora such as the United Nations, the G7 and the Council of Europe.

At the 50th Session of the UN Human Rights Council, the UK supported the renewal of the mandate of the Independent Expert on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity, and its vital work to ensure that existing human rights are applied equally to all individuals around the world. The UK worked closely with diplomatic partners - both in the global north and south - to defeat numerous hostile amendments that would have stripped the resolution of its focus and undermined the human rights of LGBT+ persons. The creation of the role in 2016 was a major achievement of the Council. Furthermore, at the Third Committee, the UK continued to ensure that the resolution on extra-judicial killings retained a reference to sexual orientation and gender identity.

As co-chairs of the Equal Rights Coalition, the UK and Argentina concluded their 3-year tenure by gathering 42 countries and over 120 civil society organisations in Buenos Aires. The conference was an important opportunity to review progress of the Coalition’s strategy and 5-year implementation plan, and to agree coordinated action to make progress on human rights and equality for LGBT+ people around the world. The conference concluded by handing over the role of co-chair to Germany and Mexico.

Equal Rights Coalition Conference, Buenos Aires, September 2022.

The UK has continued to fund research and initiatives to address the challenges faced by LGBT+ people globally. In March, Protection Approaches launched a new report on ‘Queering Atrocity Prevention’– funded by the UK Conflict Security and Stability Fund.[footnote 22] In September, the UK launched a new report on ‘What Works to Prevent Violence Against LGBTQI+ people’.[footnote 23] The initiative led to a new partnership with the USA, and a $3 million investment by USAID aimed at supporting effective approaches to prevent violence against LGBT+ people.

The UK is committed to continuing to work together with our international partners to end the violence and discrimination that persists today.

Rights of people with disabilities

Disability inclusion and rights strategy

The FCDO launched the Disability Inclusion and Rights Strategy at the second Global Disability Summit in February, alongside a range of other commitments. It sets out ambitious objectives to guide the UK’s work with, and for, people with disabilities until 2030. It focuses on 4 concrete outcomes:

- People with disabilities in all their diversity have full and equal enjoyment of all rights and fundamental freedoms.

- Full and meaningful participation and leadership of people with disabilities.

- People with disabilities have more choice and control in all aspects of their lives.

- Greater visibility of people with disabilities through quality comprehensive data and evidence.

Global challenges – including conflict, natural disasters, climate change and COVID-19 – are disproportionally affecting marginalised people, trapping them in cycles of poverty and vulnerability. As one of the most excluded groups in society, people with disabilities are more likely to be impacted by these shocks.

The UK continued to implement a ‘twin track approach’ in 2022 - mainstreaming a disability inclusive and human rights perspective across all its work, while providing targeted support to people with disabilities through disability-specific initiatives. The FCDO drew on its development and diplomatic expertise and prioritised active and meaningful participation of people with disabilities in its work.

The UK continued to be a strong international voice in support of the rights of people with disabilities, proactively championing disability inclusion at the UN and the Human Rights Council.

The UK continued to play a key role in the Global Action on Disability Network of donors, tackling a range of issues from education to humanitarian response, including as co-chairs of the inclusive health working group.

Using what it learnt from its leadership of the first Global Disability Summit in 2018, alongside Kenya and the International Disability Alliance, the UK advised Norway and Ghana on hosting the February 2022 Global Disability Summit.

The UK’s programme work with partners around the world has demonstrated significant ongoing impact on disability inclusion. In Malawi, through the Disability Rights Fund, the UK supported the Federation of Disability Organisations to advocate for more inclusive legislation. This led to the government making 32 commitments at the Global Disability Summit in February, including to incorporate aspects of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, relating to mental health, non-discrimination, and affirmative action into domestic legislation.

In Uganda, the UK supported the National Union of Disabled Persons of Uganda to conduct training for management officers of the Uganda Prisons Service on disability inclusion and on the rights of inmates with disabilities. In September, Uganda Prisons Service committed to developing a disability policy in conjunction with grassroots disability organisations to improve prison facilities.

The Disability Rights Fund also supported a national coalition of disability organisations from Indonesia to attend the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in August. This allowed them to respond to the List of Issues for Indonesia and continue to hold their government to account for the delivery of disability rights.

In 2022, the Disability Inclusive Development Programme provided over 1,000 people with disabilities in Nigeria with access to eye health services, and over 800 people with disabilities (and a further 1,100 family members) in Nepal with access to inclusive sexual and reproductive health and rights services.

British embassies across the world worked hard to support the rights of people with disabilities. The British Embassy in El Salvador partnered with inclusive employers and organised a job fair to increase the chances of people from vulnerable groups, including people with disabilities, members of the LGBT+ community, and women, securing employment. The embassy also held an awards ceremony to celebrate organisations which actively promote the inclusion of people with disabilities.

Looking ahead to 2023, the UK will continue to deliver on the commitments made in the Disability Inclusion and Rights Strategy, embedding the rights and needs of people with disabilities into all its work, including in education, humanitarian responses and healthcare.

The FCDO will also continue to work with partners, including organisations of persons with disabilities, to deliver quality, impactful programming, encouraging inclusion of people with disabilities in all their diversity and empowering the most marginalised and under-represented groups. This includes continuing to fund grassroots organisations of persons with disabilities to advocate for disability rights and hold governments to account for compliance with the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Rights of older people

The UK aims to protect the rights of all individuals at all stages of their lives. This recognises the diverse experiences, requirements and priorities of older persons, many of whom also have disabilities which can impact upon their autonomy, dignity and participation in society. This approach is shaped by meaningful engagement with civil society, both domestically and internationally.

As a key stakeholder in the Titchfield City Group on Ageing, which is led by the Office for National Statistics, in 2022 the FCDO continued to collect and analyse results, demographic and socio-economic data disaggregated by age across a significant proportion of its Official Development Assistance portfolio.

The UK continued to be a co-sponsor and vocal supporter of the UN Open Ended Working Group on Ageing, and supported resolutions to improve the rights of older persons at the UN Human Rights Council.[footnote 24]

The UK also continued to improve the availability of affordable assistive technology - including wheelchairs; hearing-aids; prosthetics and orthotics; digital devices and spectacles - in low- and middle-income countries, recognising its critical role for inclusion and the transformational impact for older persons and persons with disabilities. At the World Health Assembly, the UK successfully lobbied for the inclusion of assistive technology within the World Health resolution on strengthening rehabilitation in health systems.[footnote 25]

During 2022, for the first time, the UK funded ATscale, the global partnership on assistive technology. The partnership made its first significant in-country investments in Kenya, Cambodia and Ukraine. ATscale also developed a model for delivering hearing aids to older persons in lower-and middle-income countries.

The FCDO also funded the AT2030 research programme, led by the UK’s Global Disability Innovation Hub. The programme seeks to improve access to affordable assistive technology. Throughout 2022, it supported 5 assistive technology ventures to begin to scale-up in Africa through the Assistive Technology Impact Fund. It also contributed over 100 papers to the World Health Organisation and UNICEF’s Global Report on Assistive Technology,[footnote 26] launched in April.

In 2023, the UK will contribute a £31 million uplift to the AT2030 programme which will develop, test and roll out more affordable assistive products.

Rights of the child

In 2022, the UK remained steadfast in its commitment to protecting and promoting the rights of children around the world through our policy, programmatic and diplomatic leadership.

Children’s rights were integrated across new strategies. In December, Minister, of State for Devlopment and Africa, Andrew Mitchell, launched a new position paper, “Addressing the Climate, Environment and Biodiversity Crises in and through Girls’ Education”,[footnote 27] which highlights the critical importance of fostering the knowledge, skills, and agency of young people for climate adaptation and mitigation.

At the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative International Conference in November, the UK launched a Platform for Action Promoting the Rights and Wellbeing of Children Born of Conflict-Related Sexual Violence.[footnote 28] The UK, along with partners, including Canada, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict, have committed to key actions under this platform to protect some of the most vulnerable and stigmatised children globally.

The online space continued to pose growing and serious threats to children. In response, the then Minister for Safeguarding at the Home Office pledged a further £16.5 million from 2022 to 2025 for the Global Partnership to End Violence Against Children to help deliver a world in which every child can access and benefit from the digital world, safe from harm [footnote 29]. In 2022, this funding supported the identification of over 1,200 child victims of online child sexual abuse and led to 7 new countries establishing a national reporting mechanism to identify and remove child sexual abuse material, including Argentina, Kenya, and Tunisia.

The UK continued to apply diplomatic pressure in the UN Security Council Working Group on Children in Armed Conflict (CAAC). The UK responded to the UN Secretary-General’s 2022 annual report and CAAC country-specific reports,[footnote 30] which assess the grave violations that took place against children in conflict zones and list the governments and armed groups responsible for committing these grave violations.

The UK hosted a Wilton Park event with the Office of the UN Secretary General’s Special Representative on CAAC, to mark the 25th anniversary of the CAAC mandate, and explore the challenges, barriers and opportunities for action.

The UK supported a number of child’s rights resolutions in 2022, including the Kigali Declaration for Child Care and Protection Reform, passed at the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in June. This resolution protected key language on the importance of replacing institutionalisation with quality alternative care for children. The UK continued to show leadership on tackling child marriage, and in November, supported a new resolution which focussed particularly on supporting the most marginalised girls at risk of child marriage.

The UK remained committed to supporting the meaningful participation of young people in advocating for their rights. In March, the then Minister for Africa held a virtual roundtable with young people from conflict-affected countries to hear their experiences and recommendations on what more the UK could do to better protect children in conflict. They spoke about the importance of a childhood free from fear, and the right to go to school and access healthcare.

In 2023, the UK will continue to promote the rights of children around the world, including by amplifying their leadership and consulting them on the issues that affect them.

Chapter 3: Civic space and fundamental freedoms

A vibrant and diverse civil society is a key pillar of open societies. The UK aims to be a champion of open, diverse, and pluralistic civic space globally, both online and offline. These spaces, in which people can access and enjoy their rights to the freedoms of peaceful assembly, association, and expression, are crucial for good governance and a healthy democracy. The UK is strongly committed to civic freedoms, which are important as they allow people to put forward their views publicly, influence policymaking and society more broadly, and help to promote accountability.

Strong governments promote pluralism within civil society and ensure that supportive and critical voices alike can be heard. However, civic action can be so powerful that many governments have come to see it as a threat. Civic space is therefore becoming increasingly restricted in many parts of the world, for example, Putin’s action against an active civil society in Ukraine. The UK stood alongside civil society against these encroachments and supported the extraordinary bravery of human rights defenders (HRDs) and people who work for civil society organisations (CSOs) in Ukraine and in some of the world’s most dangerous places.

Civil society faced many challenges in 2022 with governments trying to restrict civic space in various ways. Many countries passed restrictive legislation, making registration and financing of NGOs difficult. Countries also introduced measures restricting freedom of expression including censorship, internet shutdowns, surveillance and attacks on journalists, HRDs and academics.

Protests have flared up in countries with closed civic space and autocratic regimes have tried to repress them. For example, in Iran the authorities have used lethal force to crack down on protesters, killing hundreds and arresting thousands more.[footnote 31]

Transnational repression, where governments reach across national borders to coerce, intimidate, harass or harm perceived critics overseas, has become more visible in 2022. Freedom House recorded 79 incidents committed by 20 governments. The most prolific perpetrators of transnational repression remain the governments of China, Turkey, Russia, Egypt, and Tajikistan.[footnote 32]

Governments have sought to discredit activists and CSOs by accusing them of acting on behalf of foreign powers. This has particularly affected groups advocating for women’s rights and women HRDs, environmental groups, labour rights groups, LGBT+ people and young people. According to the findings of the CIVICUS Monitor, an international alliance dedicated to strengthening citizen action and civil society throughout the world, the world has faced further regression on civic space in 2022, with it worsening in 15 countries and improving in only 10.[footnote 33]

In India, some NGOs continued to face difficulties due to the application of the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act by the Indian authorities. In April, the foreign funding licence for the international NGO Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative was cancelled. The UK raised these issues directly with the Indian government, regularly engaging with the affected NGOs and continuing to support NGO partners in India, including through programmes.

The Government of Mozambique (GoM) has approved and submitted to its parliament a draft NGO bill, which risks adding stricter controls on international and national NGOs. The bill is due to be discussed in its parliament in 2023. The bill is part of the GoM’s response to the Financial Action Task Force report that added Mozambique to a list of countries with significant vulnerabilities to money laundering and terrorism financing, including in the non-profit sector. Civil society has been critical of the bill, arguing that it was prepared without public consultation and goes against regional and international human rights standards. The UK is monitoring the situation closely.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has had far-reaching and deeply negative domestic consequences, including for civil society. The Russian regime moved swiftly to crush opposition to the war, enacting laws that criminalised speaking out against the war or in some cases simply reporting factually about it. This environment has severely restricted the work of CSOs and independent media outlets. With international partners, the UK invoked the OSCE’s Moscow Mechanism which evidenced Russia’s efforts to wage a repressive war against its own people. The UK is taking forward the report’s recommendations and remains committed to the protection and promotion of human rights and civil society in Russia.

Civil society faced unprecedented repression in Belarus, with freedom of association almost non-existent. The regime forced, or pressured, hundreds of CSOs to close. More than 1,000 CSOs have been lost since 2020. As of December 2022, at least 757 non-commercial organisations were in the process of forced liquidation. The number of organisations that have opted for independent liquidation is also increasing, reaching 416 at the end of the year.

In 2022, the rights of the Sudanese people to freedom of speech, expression and assembly continued to be limited. Military and security forces used violence against peaceful demonstrators, with at least 68 protestors killed during 2022 and hundreds more sustaining serious injuries. Arbitrary detentions continued to be used to suppress opposition and dissent across Sudan. Hundreds of civilians and political activists were unlawfully arrested without charge or trial under emergency laws.

The UK continued to urge the Sudanese authorities to open and protect civic space and civil society. UK funding to the Thomson Foundation also helped deliver a digital learning WhatsApp course on disinformation and misinformation, which reached over 10,600 people in Sudan.

There were widespread reports of illegal and disproportionate use of force and human rights violations in Peru, in response to the protests which followed the change in government on 7 December. The UK Embassy in Lima and UK Ministers raised concerns with Peruvian counterparts about the handling of protests and alleged abuses by forces of law and order. The UK urged the authorities to ensure a proportional, legal response to protests, and the protection of human rights. The UK also called for protests in support of legitimate concerns to be peaceful, and for those who subvert legitimate peaceful protest to be brought to justice.

The Government of South Sudan continued to limit media freedom and civic space through the intimidation, harassment, illegal arrest and arbitrary detention of journalists, HRDs and critics. High profile cases included 7 members of the People’s Coalition of Civil Action being arrested, detained, and standing criminal trial following calls for peaceful protests. A Voice of America journalist was also arbitrarily detained, including time in prison, for their coverage of a protest in Juba where security agents shot at and beat protestors.[footnote 34]

Civic space continued to be contested in the multilateral arena, with CSOs and HRDs facing intimidation and reprisals for engagement and cooperation with the UN, its representatives and mechanisms. The UK co-sponsored an event hosted by Ireland, along with the Human Rights Council, and other member states and CSOs, at the Third Committee of the UN General Assembly, entitled ‘Intimidation and Reprisals for Cooperation with the UN - Global Trends and Good Practices’ to highlight and challenge this behaviour.

The UK worked to empower women engaged in peacebuilding and prioritised work to counter reprisals. UK contributions to the Urgent Action Fund made emergency grants available to women HRDs and peacebuilders facing intimidation or reprisals in conflict settings. The UK also supported the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to develop guidance on preventing reprisals, and to train UN staff to support women peacebuilders and HRDs facing these risks. The UK has also been elected to the UN Economic and Social Council NGO Committee, where it will continue to work to ensure a fair, open and transparent approach to NGO accreditation.

Human rights defenders

HRDs often document and report human rights violations and abuses and speak up for vulnerable and marginalised groups, bringing public attention to cases, holding governments to account and acting as agents of change.

HRDs play an important role in defending the full range of human rights, working tirelessly to stand up for those who were threatened, oppressed and silenced, often at great personal risk. According to the NGO Front Line Defenders, at least 401 HRDs were killed in 26 countries in 2022.[footnote 35] Other HRDs were threatened, arbitrarily detained, placed under surveillance or disappeared.

The UK continued to stand with all those speaking out for rights and freedoms around the world and supported the courageous work of HRDs. In December, at an FCDO stakeholder event to mark Human Rights Day, the Minister for Human Rights, Lord (Tariq) Ahmad of Wimbledon, recognised the work of HRDs around the world, and the Foreign Secretary committed to continuing to support civil society and HRDs.

Lord (Tariq) Ahmad addressing UK human rights stakeholders at an event to mark Human Rights Day in December.

The 2019 publication on “UK support for Human Rights Defenders” sets out the importance of HRDs to the UK and what the UK Government does to support them, including through multilateral organisations and bilateral engagement.[footnote 36] The UK diplomatic network continued to monitor cases, observe trials, and raise issues with host governments.

UK action to support HRDs in Venezuela

In Venezuela, the UK has supported HRDs to strengthen their networks and build capacity on human rights documentation and reporting. For example, to mark Democracy Day in Venezuela’s restrictive environment, the British Embassy identified 40 young and rising leaders in the field of democracy, human rights, entrepreneurship and science that the Embassy had not engaged with before and held structured networking sessions for the young leaders to get to know each other’s work. The event was valued by attendees who were able to identify complementary initiatives and spark collaboration in a country where visible activism is increasingly dangerous.

In Thailand, civic space remains challenged. Authorities used the lèse majesté law and other criminal charges to limit freedom of expression. At the end of 2022, more than 1,800 people were facing prosecution for exercising their rights to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly. The UK continued to support HRDs through trial observation and activities in partnership with like-minded missions to defend HRDs at risk. The UK also provided project funding, including capacity building for journalists, on digital security skills and criminal justice procedures. This will strengthen their ability to work securely and to effectively document and report criminal cases against HRDs.

In 2023, the UK will explore a range of options to build on its existing guidance and support to HRDs, including via strengthened working with partner countries across the world. The UK’s efforts will continue to reflect its guiding principle of doing no harm.

Media freedom

The UK continued to highlight the importance of media freedom. Serious threats to journalists and media workers remained, with over 80 killed in 2022. The rate of impunity for crimes against journalists remained high at 86%.[footnote 37] The UK deployed its diplomatic and development tools to support media freedom, to fpromote the safety of journalists and to improve media sustainability.