Study

Published 23 February 2017

Valid: 23 February 2017 to 24 May 2017

Data relate to the calendar year 2016 and all comparisons are with the calendar year 2015, unless indicated otherwise.

Back to ‘Immigration statistics October to December 2016’ content page.

This is not the latest release. View latest release.

1. Key facts

In 2016, there were 207,200 study-related visas granted, 1% fewer than the previous year. This number includes dependants but excludes the unsponsored short-term student category, formerly known as ‘student visitors’.

Over the same period, the number of university-sponsored study visa applications (main applicants) rose slightly by 1% to 167,554. There was a 6% increase for Russell Group universities to 80,360. There were falls for the Further education (9% to 14,586), English language school (3% to 2,828), and Independent school (2% to 13,376) sectors. Most of the fall in the Further education sector’s sponsored visa applications since the peak in mid-2011 can be accounted for by licenses which have since been revoked.

In the year ending September 2016, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) estimates that there were 87,000 non-European Union (EU) long-term immigrants coming to study with an intention to remain a year or more; 31,000 lower than the preceding year, a statistically significant change.

By contrast, in the year ending September 2016, ONS also estimates that the number of non-EU former students who were long-term emigrants from the UK had risen to 41,000, although this was not a statistically significant increase from 40,000 in the previous 12 months. Although they relate to different cohorts of students, the difference between the number of long-term students entering the UK (87,000) and the number of former students departing (41,000) was around 46,000.

Just five non-EU nationalities accounted for the majority (58%) of the 207,200 study-related visas granted in 2016, with the largest number by far going to Chinese nationals (76,636 or 37% of the total). There were increases for the following nationalities: Chinese (+5,885 or +8%), Indonesian (+492 or +18%), Kuwaiti (+438 or +17%), and Pakistani (+314 or +10%); but falls for Nigerian (-3,039; -32%), Malaysian (-1,833; -19%), and Brazilian (-1,552; -66%).

Study-related grants of extensions fell by 34% or 21,729 to 42,032 in 2016. This is mostly accounted for by the University sector with a fall of 13,582 (-27%), and Further education sector with a fall of 4,070 (-84%).

There were 295,000 short-term student category admissions in the year ending June 2016, much higher than the numbers of short-term student category visas granted (82,318 over the same period). This was due to many short-term student admissions being from nationalities who were not required to obtain a visa if they wished to come to the UK as a short-term student (previously referred to as ‘student visitor’) for up to a maximum of 6 months.

In the calendar year 2015, the latest period for which data are available, more than half of the short-term student admissions are accounted for by US nationals (185,000), who do not require a visa for these short visits.

2. Study immigration: latest trends

| 2015 | 2016 | Change | Percentage change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study-related visas granted, excluding short-term study category (1) | 210,311 | 207,200 | -3,111 | -1% |

| of which (Top 5): | ||||

| China | 70,751 | 76,636 | +5,885 | +8% |

| United States | 14,143 | 14,172 | +29 | +0% |

| India | 11,160 | 11,330 | +170 | +2% |

| Hong Kong | 9,041 | 9,007 | -34 | -0% |

| Saudi Arabia | 9,360 | 8,425 | -935 | -10% |

| Short-term study visas (main applicants only)(1) | 62,608 | 87,197 | +24,589 | +39% |

| Year ending September 2015 | Year ending September 2016 | Change | Percentage change | |

| Long-term non-EU immigration for study, excluding dependants (2) | 118,000 | 87,000 | -31,000 | -26% |

| Long-term (1 year or more) study-related visas, excluding dependants | 138,488 | 141,286 | +2,798 | +2% |

2.1 Table notes

Source: Home Office, Immigration Statistics October to December 2016, Visas table vi 04 q (Visas volume 1) and Visas table vi 06 q s (Visas volume 3), International Passenger Survey (IPS), ONS, Migration Statistics Quarterly Report.

(1) The short-term study category (previously described as Student visitor) allows individuals to come to the UK for 6 months (or 11 months if they will be studying an English language course) and cannot extend their stay (further details at Short-term study visa). For consistency and comparability over time, short-term study visas have been excluded from study-related totals.

(2) Immigration for study data are estimates of the number of non-EU nationals intending to change their residence to the UK for at least 12 months based on the IPS.

3. Long-term trends in student immigration

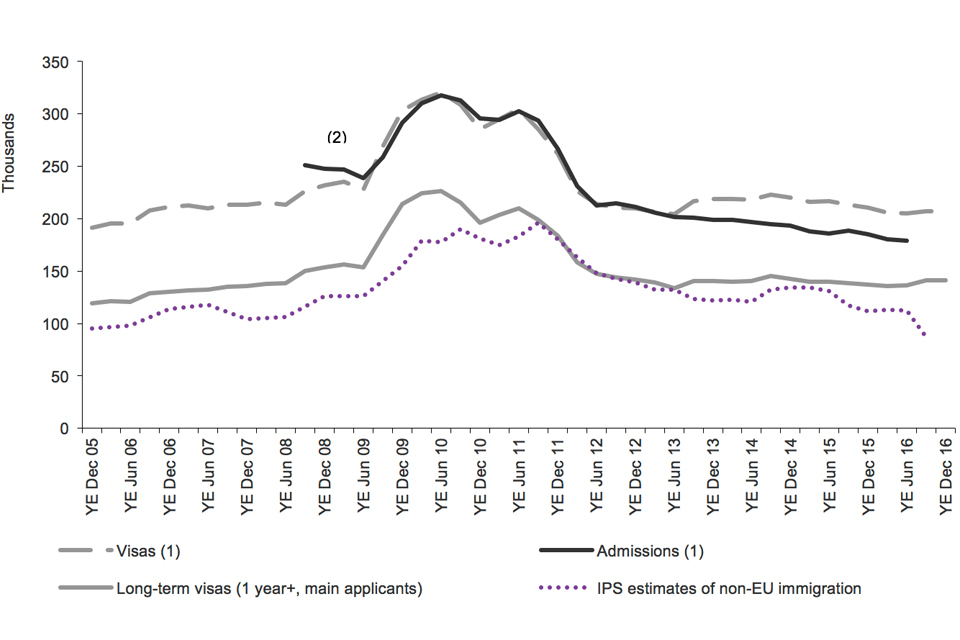

The chart shows the trends for study of visas granted, admissions and IPS estimates of non-EU immigration. The data are sourced from Tables vi 04 q and ad 02 q and corresponding datasets.

3.1 Chart notes

Source: Home Office, Immigration Statistics October to December 2016, Visas tables vi 04 q (Visas volume 1), Admissions table ad 02 q and corresponding datasets; ONS, Population and migration.

(1) Excludes short-term students (previously referred to as Student visitors) who are allowed to come to the UK for 6 months (or 11 months if they will be studying an English language course) and cannot extend their stay. A proportion of Tier 4 student visas are also short-term (under 1 year), but are not included within the short-term student category (see Entry clearance visas by length).

(2) Prior to the year ending September 2008, the count of student admissions is not comparable as there was no specific admissions category for short-term students (previously referred to as Student visitors) who may then have been recorded as either students or visitors.

The above chart shows that IPS long-term immigration estimates, while being substantially lower as they cover only those intending to remain a year or more, have followed a broadly similar trend to student visas granted and passenger arrivals over the longer term. However, the reduction in the IPS estimate in the latest figure is unprecedented.

There are a range of potential reasons why IPS figures for long-term migrants may be different from figures for study visas granted or passenger arrivals, and hence why the trends in the different series do not match. These include:

- sampling variation in the IPS (for example, the fall of 31,000 in non-EU study-related immigration for the year ending September 2016 had an estimated confidence interval of +/-19,000)

- IPS data for study relate to individuals whose main reason for migration was study so (unlike visas data) are likely to exclude their dependants; IPS data are likely to be more comparable with visa totals for main applicants than with the total for all study-related visas (e.g. including dependants)

- differences between intentions and visa length

- individuals may migrate for multiple different reasons

- timing differences between when visas are granted and when an individual actually travels

- visa and admissions data include dependants, and both short- and long-term migrants

Further comparison of the data is described in the ONS publication ‘International student migration what do the statistics tell us? (PDF 619Kb) and the user guide.

4. Register of sponsoring educational institutions

On 3 January 2017, there were 1,323 educational institutions on the UK Visas and Immigration register of sponsoring educational institutions. This was 3% fewer than the number on 30 September 2016 (1,362), and 6% lower (1,404) than a year earlier (4 January 2016), which continues the reduction in numbers seen since the published series began in October 2011 (when the number of educational sponsors was 2,370). The long-term reduction in the number of sponsoring educational institutions follows the introduction of new accreditation criteria and conditions of status for educational sponsors from April 2011, as well as the removal from the list of sponsors of organisations which have since ceased operation.

5. Sponsored study visa applications by education sector

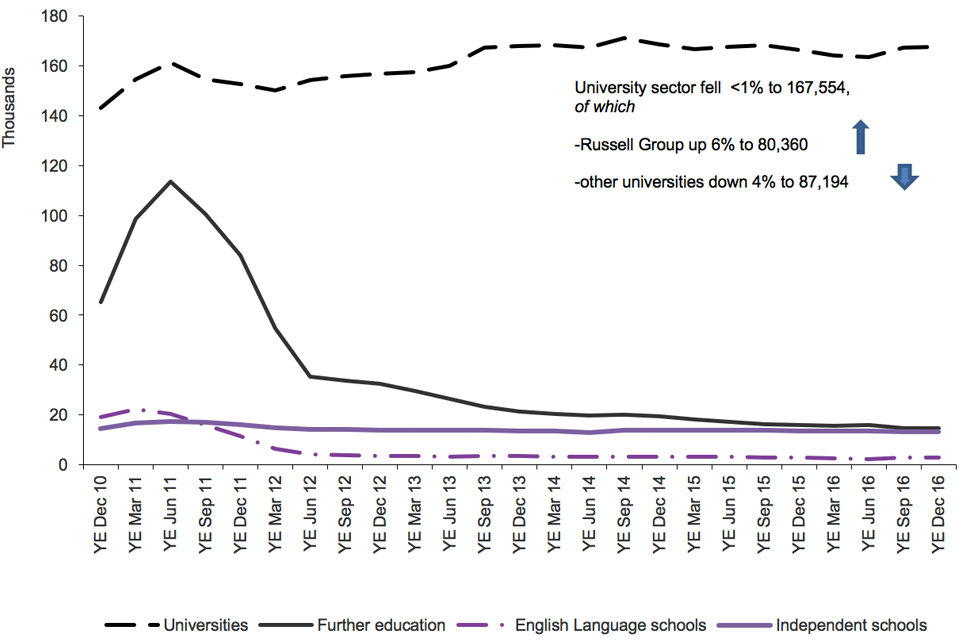

The number of study-related sponsored visa applications (main applicants) fell by less than 1% in 2016 to 200,849, compared with the previous 12 months (201,751). There was a rise of 1% to 167,554 in sponsored visa applications for the University sector as a whole, and this included a 6% increase for Russell Group universities to 80,360 but a 4% decrease for other universities to 87,194. Over the longer term, the number of visas issued to study at universities has been broadly flat since 2013.

In the latest year, there were falls in the Further education (9% to 14,586), English language schools (3% to 2,828) and Independent school (2% to 13,376) sectors.

5.1 Study-related sponsored visa applications by sector

The chart shows the trends in confirmations of acceptance of studies used in applications for visas by the education sector since 2010 to the latest data available. The chart is based on data in Table cs 09 q.

Chart notes

Source: Home Office, Immigration Statistics October to December 2016, Sponsorship table cs 09 q.

‘Universities’ relate to UK-based higher education institutions.

‘Further education’ relates to tertiary, further education or other colleges.

5.2 New entrants to UK Higher Education

HESA recently published data on student enrolments at UK higher education providers for the academic year 2015-16. (NB The period of reporting is pre-referendum and therefore does not reflect any impact from the result.) Overall, in respect of international students the numbers were not markedly different from the previous year. Non-UK domiciled new entrants fell by less than half of one per cent in 2015-16 to 231,290 compared with 2014-15 (232,120). Within this, non-EU domiciles fell by 1% from 2014-15, while EU-domiciled new entrants increased by 2%.

6. Immigration for study, and emigration of former students

In the year ending September 2016, ONS estimates that there were 87,000 non-EU long-term immigrants coming to study and who had an intention to remain a year or more, a 31,000 fall which is statistically significant.

By contrast, in the year ending September 2016, ONS also estimates that the number of non-EU former students who were long-term emigrants from the UK had risen to 41,000, although this was not a statistically significant increase from 40,000 in the previous 12 months. Although they relate to different cohorts of students, the difference between the number of long-term students entering the UK (87,000) and the number of former students departing (41,000) was around 46,000.

Over the same period, the number of long-term (1 year or more) Tier 4 (sponsored) study-related visas granted (main applicants) was 2% higher at 141,286. Although the trends in the long-term estimates and comparable visa numbers can differ, they have been fairly close given the definitional differences and the inherent variation in the ONS survey-based estimates.

Source: ONS, IPS, Migration Statistics Quarterly Report.

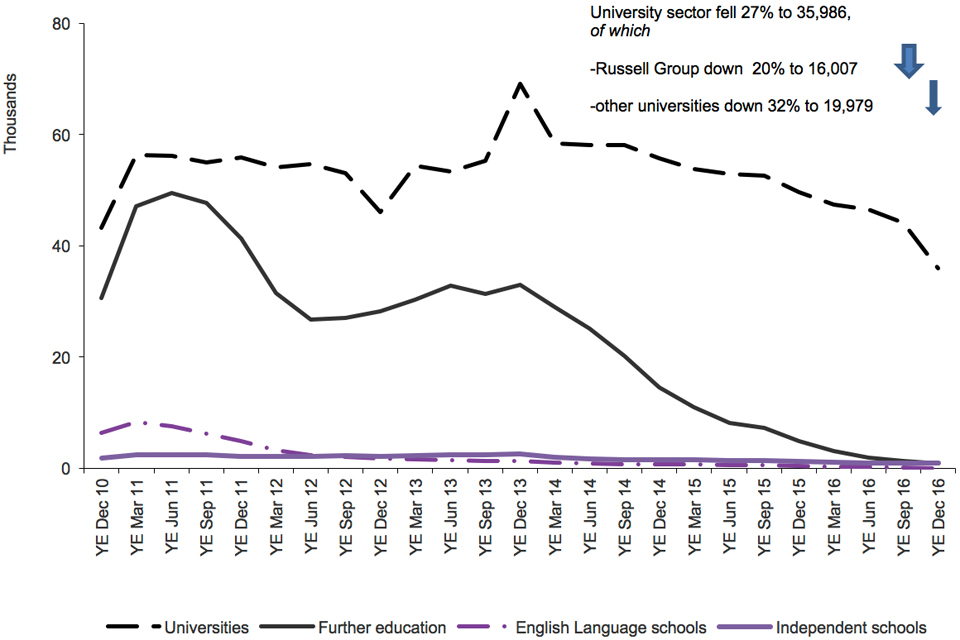

6.1 Study-related sponsored applications for extensions by sector

The chart shows the trends in confirmations of acceptance of studies used in applications for extensions of stay by the education sector since 2010 to the latest data available. The chart is based on data in Table cs 10 q.

Chart notes

Source: Home Office, Immigration Statistics October to December 2016, Sponsorship table cs 10 q.

‘Universities’ relate to UK-based higher education institutions.

‘Further education’ relates to tertiary, further education or other colleges.

The number of study-related sponsored applications for extensions (main applicants) fell by 18,558 (33%) to 37,751. Most of the 18,558 drop was accounted for by a 27% fall (13,582) in the University sector, of which Russell Group fell by 20% (4,111), and the Further education sector fell by 84% (4,070). There were also a 27% fall (324) in the Independent school and 91% fall (428) in the English language sectors. These trends are likely to reflect previous falls in the visas granted for the sector and tightening of the rules in order to address non-compliance (see chart ‘Study-related sponsored visa applications: FE sector’ at Sponsored study visa applications by education sector).

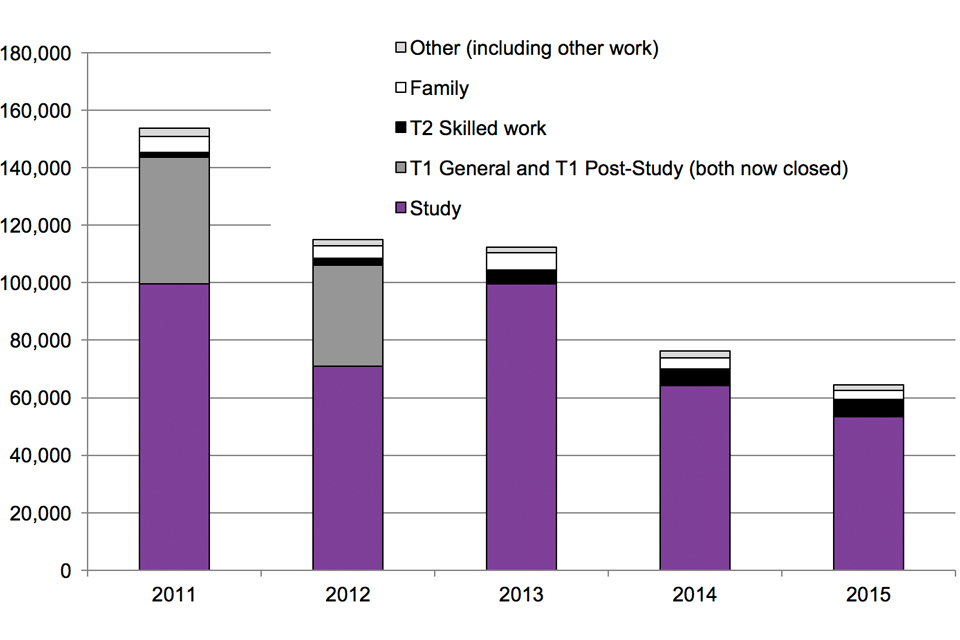

Looking at individuals’ previous category, an estimated 64,483 former students (main applicants) were granted extensions in 2015 (the latest available data for this analysis), compared with 76,175 for 2014. Of the extensions granted in 2015, the majority (83%) allowed individuals to continue to study. There has been a fall in the number of students allowed to switch into a work category from 46,875 in 2011 to 7,226 in 2015, largely reflecting the closure of the Post-study work route. Conversely, the number of students allowed to switch into Tier 2 skilled work has increased from 1,730 in 2011 to 6,004 in 2015.

6.2 Extensions granted to former students (by current category of grant) 2011 to 2015 (main applicants)

The chart shows the trends in extensions of stay for former students by previous category. The chart is based on data in Tables expc 01 and expc 01 w.

Chart notes

Source: Home Office, Immigration Statistics October to December 2016, Extensions tables expc 01 and expc 01 w.

Note that short-term students are normally only allowed to stay for up to 6 months (11 months for English language schools) and cannot extend their stay.

7. Short-term students

There were 295,000 short-term student admissions in the year ending June 2016, much higher than the numbers of short-term student visas (previously referred to as ‘student visitors’) of which there were 82,318 granted over the same period. This is due to many nationalities who are not required to obtain a visa if they wish to come to the UK as a short-term student for up to a maximum of 6 months (11 months for English language schools).

In the calendar year 2015, the latest period for which figures are available, more than half of the short-term student admissions are accounted for by US nationals (185,000). Other non-visa countries using the short-term student admission route in 2015 include Japan (13,500) and Brazil (13,400).

Where a visa is required, they are granted for a maximum of 6 months in duration or, in a very small number of cases, for 11 months if studying a longer English language course. Short-term students are not long-term migrants and cannot extend their stay. Some students in the study category (Tier 4 of the Points Based System) also have short-term visas (under 1 year), but are not included within the short-term student category (see ‘Entry clearance visas by length’).

The number of short-term student visas granted rose by 39% to 87,197 in 2016. Higher numbers of grants to Russian and Turkish citizens accounted for nearly half (44%) of the 24,589 increase (6,584 and 4,283 respectively). For further information on short-term students see Short-term study visa and the Home Office research report, Student visitors.

8. Staying in the UK

In February 2017 the Home Office published Statistics on changes in migrants’ visa and leave status: 2015, which shows how non-European Economic Area (EEA) migrants change their immigration status or achieve settlement in the UK.

This analysis shows that the majority (69%) of migrants issued a study visa in 2004 no longer had valid leave to remain in the UK 5 years later. This proportion has increased in each cohort arriving from 2005, to 81% for those issued a study visa in 2010.

Conversely, the proportion of migrants who gained settlement 5 years after entering on a study visa declined over the same period. For people issued a study visa in 2004, only 4% had gained settlement 5 years later, and a further 27% still had valid leave to stay in the UK, either as students or in another route. For those arriving in 2010, only 19% had valid leave to remain in the UK or had obtained settlement in 2015; however, it would be unusual to acquire settlement that quickly as most students arrived in this non-settlement route and, if seeking to remain longer, would not have had sufficient time to transfer into routes with the prospect of permanent leave.

These changes are consistent with the tightening of the Immigration Rules for students since September 2007 (for details please see ‘Policy and legislative changes affecting migration to the UK: timeline’. They may also be partly related to the economic conditions following the recession in 2008-09, which for a while may have reduced the incentive for students to remain and seek work in the UK.

Over a quarter (29%) of those granted settlement in 2015 originally arrived to study, or had accompanied a student. This proportion has increased from 14% of those granted settlement in 2009. As this is a temporary route, these student migrants will, in most cases, have subsequently switched into another route to permanent settlement or used the long-term residency rule and therefore this growth in the proportion granted settlement who came to the UK originally to study will reflect the growth in student migration over a long period as well as changes in the numbers of other types of migrants seeking to remain in the UK.

The study cohort reported on here excludes the short-term student category (previously referred to as ‘student visitors’) visas that cannot be extended and normally only have validity of 6 months or, in some cases, up to 11 months.

Source: Home Office, ‘Statistics on changes in migrants’ visa and leave status: 2015’ formerly known as ‘Migrant journey’.

9. Data tables

Data on student immigration, sourced from Home Office administrative systems, can be found in the following tables:

Sponsorship: tables cs 07 q to cs 14 q

Visas vol. 1: tables vi 01 q, vi 04 and v1 04 q

vi 01 q Entry clearance visa applications and resolution by category

vi 04 Entry clearance visas granted by category

vi 04 q Entry clearance visas granted by category

Visas vol. 3: table vi 06 q s

vi 06 q s Entry clearance visas granted by category and country of nationality: Study

Admissions: tables ad 02 to ad 03 and ad 03 s

Extensions: tables ex 01 to ex 02 s

Provisional estimates of long-term immigration for formal study from the ONS IPS relate to those whose main reason for migration is formal study and so are likely to exclude dependants (who would be more likely to say their main reason was to ‘accompany or join’ rather than formal study). ONS data is published at Migration Statistics Quarterly Report.

The Higher Education Statistics Agency publishes data on new entrants to UK higher education providers.

10. Background information

This section includes figures on study-related visas granted, passenger arrivals and extensions granted for non-European Economic Area (EEA) nationals. It also includes figures on long-term immigration to study (i.e. those intending to stay for at least 12 months to study) for non-EU nationals.

Data include dependants as well as main applicants unless stated otherwise. Estimates of long-term immigration for study from the ONS IPS relate to those whose main reason for migration is to study and so are likely to exclude dependants (who would be more likely to say their main reason was to ‘accompany or join’ rather than to study). All comparisons are with the previous 12 months unless indicated.