Improving attainment among disadvantaged students in the FE and adult learning sector: evidence review (HTML)

Published 21 January 2020

Applies to England

Improving attainment among disadvantaged students in the FE and adult learning sector

An evidence review

Research report January 2020

1. Executive summary

The Further Education and adult learning sector (FE sector) plays an important role in improving socio-economic outcomes and supporting social mobility. Individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds are significantly less likely to participate in learning or training and tend to have lower attainment but more likely to participate in FE and adult learning compared to other post-16 routes. For government reforms designed to increase adult learning to be effective and for outcomes to improve, it is crucial to develop the evidence on what works and share knowledge and best practice. Yet there has been relatively limited activity focussed on bringing together the evidence on what works to improve outcomes in the sector. This report aims to help fill this gap by reviewing and mapping the evidence on what works to improve attainment for disadvantaged students in the FE sector.

1.1 Key findings

The review found 63 studies across 4 countries, 9 of which are from England. Fifty-two of the studies are rated as ‘high quality’ of evidence. This contrasts with the evidence in the education sector (3 to 18 years) given it is anticipated that more than 3,000 studies will be included in Education Endowment Foundation’s new teaching and learning toolkit.

Programmes[footnote 1] designed to improve attainment among disadvantaged students can have a positive impact but some appear to only have marginal effects or no impact. While some research shows that programmes can significantly improve attainment (for example, obtaining a Level 2 qualification), other studies found the improvement to be modest. This indicates that the programmes are only slightly more effective than ‘business as usual’.

Programmes can improve students’ progress in learning, although these improvements may not be sustained over the longer term. Programmes have been used to support achievement in basic skills and support progress on to further and higher education. Despite encouraging short-term effects, however, improvements may not be sustained over the longer term or lead to higher levels of attainment.

Overall, the evidence on what types of intervention work to support disadvantaged learners is mixed. Much of the evidence included in this review suggests that different programme types have mixed outcomes. However, the most effective programmes appear to be those which offer comprehensive support and those that integrate with course curriculum (for example, embedding basic skills provision in a vocational pathway).

There is a lack of evidence on what works for specific groups of disadvantaged students. While there are a few studies that consider what works for specific groups, such as care leavers, lone parents or adults with an ESOL need, most programmes are designed to support disadvantaged students in general – individuals with low skills or on low incomes.

Most evaluations are relatively short-term, with only a few studies tracking longer-term outcomes. Most of the studies in this review evaluate the impact of a programme over a relatively short timeframe. Fewer evaluate outcomes several years post-randomisation. As attainment may be a longer-term outcome, studies that have a short evaluation period may not capture this outcome, or other related socio-economic outcomes.

Overall, the review found a lack of UK-based casual evidence. While there is a breadth of research and evidence in the FE sector, it tends to be small-scale and qualitative rather than being focused on impact and policy effectiveness. Most causal evidence is from the US which presents limitations for transferability to the UK context.

1.2 Recommendations

Government should invest £20 million over 5 years to establish a What Works Centre for FE. The policy brief that accompanies this review provides more detailed information on this investment and priorities needed.[footnote 2]

Government and the Centre should focus on what works across all stages of the learner journey, from participation to longer-term socio-economic outcomes. This will require investment in long-term evaluations that track outcomes over several years.

Government and the Centre should also focus on what works for specific groups of learners. Disadvantaged groups, such as care leavers and adults with ESOL needs, face specific barriers to learning. Yet there is limited evidence on what works for whom.

2. Introduction

The Further Education and adult learning sector (FE sector) plays an important role in improving socio-economic outcomes and supporting social mobility. A disproportionate number of learners in the FE sector are from disadvantaged backgrounds compared to other post-16 education routes: nearly a third of students are from the 20% most deprived areas in England.[footnote 3] FE students are also likely to be on low incomes, with 25% claiming out-of-work benefits before they started their course.[footnote 4]

FE and adult learning can improve employment outcomes at various stages in individuals’ working lives, alongside health, wellbeing and social integration outcomes.[footnote 5] It also provides opportunities for individuals to gain new qualifications and progress out of low pay, as individuals with low or no qualifications are more likely to get stuck in low pay and employees with no formal qualifications earn around 20% less than employees with GCSEs.[footnote 6] The sector will also play an increasingly important role in helping workers retrain or upskill as technological developments change demand for skills.

Yet, despite the FE sector’s role in tackling these challenges, there has been relatively limited activity focused on collating the evidence on ‘what works’ to help practitioners close the attainment gap between disadvantaged pupils and their peers. This report aims to help fill this gap by reviewing and mapping the evidence on what works to improve attainment for disadvantaged students in FE and adult learning.

3. Policy context

This section looks at the challenges relating to FE and adult learning as they relate to key stages in the ‘learner journey’, from engagement and participation to the socio-economic returns from FE and adult learning, before setting out the latest policy developments.

3.1 Policy challenges

Low and unequal participation

There has been a long-term decline in the level of adult participation in further education and adult learning. This is visible in the number of adults taking funded courses, with the number of adults aged 19 and over taking a non-apprenticeship further education course falling by nearly two-thirds.[footnote 7] It is also evident in adults’ self-reported participation in learning. The latest data from Learning and Work’s (L&W)’s adult participation survey found that just 1 in 3 adults (35%) had taken part in learning in the last 3 years, the lowest level in the survey’s 22 years.[footnote 8] Participation in adult English and maths provision is also falling when more than 5 million adults lack both functional literacy (below Level 1) and numeracy (below entry Level 3).

Beyond the headline figures on adult participation, there is also evidence of stark inequalities in access to learning, with disadvantaged adults being significantly less likely to participate.[footnote 9] The adult participation survey and the Social Mobility Commission’s adult skills gap report highlight the extent to which the adults who could most benefit from access to education and training – based on social class, level of education and employment status – are the least likely to be taking part, with gaps in many areas having grown in recent years.[footnote 10]

The inequalities in participation are partly caused by employers investing in training workers who are already highly skilled. According to the Office for National Statistics’ (ONS) annual population survey, adults with a Level 4 qualification or above are over 50% more likely to have received training in the last 3 months than adults who do not have a qualification at that level.[footnote 11] Employers appear to see more of a ‘business case’ for upskilling their already well qualified workers, rather than supporting less well qualified workers to progress.

Variation in attainment

Disadvantaged students tend to achieve lower level qualifications. The Longitudinal Education Outcomes (LEO) data shows that students who achieved Level 2 or below in FE as their highest qualification were more likely to be disadvantaged than students who achieved Level 3 or above.[footnote 12]

Achievement rates vary across different courses, learner groups, institutions and local areas. Achievement rates for adult basic maths and English courses were 65% compared to an average of 89% across all qualification types.[footnote 13] Overall achievement rates for adult learners (aged 19+) vary from 83% in the Swindon and Wiltshire LEP area to 91% in the North East LEP area.

Variation in returns from FE and adult learning

Disadvantaged students are less likely to progress on to higher level earnings compared to non-disadvantaged students. Non-disadvantaged students were more than twice as likely to progress on to higher level earnings (over £25,000) by age 26 compared to disadvantaged students, 32% and 14% respectively.[footnote 14]

3.2 Developments in government policy

There have been a number of recent policy interventions which aim to help adults access education and training opportunities.

Apprenticeships have increasingly been seen as a tool for upskilling adults, rather than just a route for young people into the labour market, with those aged 25 and above accounting for two-fifths of apprenticeship starts in 2017/18. The apprenticeship levy- a 0.5% levy payable by employers with a pay bill of over £3 million -was introduced in 2016 in an effort to encourage more employers to invest in skills. With the apprenticeship levy account set to be overspent this year, there have been growing concerns that spending on expensive higher and degree level apprenticeships may come at the cost of opportunities for young people and disadvantaged adults.[footnote 15]

From this year, the government has devolved the adult education budget (AEB) to 6 mayoral combined authorities and delegated the budget to the Mayor of London. The AEB funds non-apprenticeship further education for adults aged 19 and over. The aim of devolution of the AEB was to allow local areas to better align adult education and skills provision with local needs, so that funding supports local residents and delivers on local economic priorities. Mayors have expressed a desire to use the devolved funding to narrow inequalities and support adults with lower levels of qualifications to progress into higher skilled jobs. However, this budget has reduced significantly in recent years, with spending on adult education – excluding apprenticeships – falling by 47% since 2009/10.[footnote 16]

More recently, the government has been developing the National Retraining Scheme (NRS). This new programme aims to help adults retrain into better jobs, and to be ready for future changes in the economy, including the impact of automation. The scheme is focused on adults aged 24 and over who are in work on low to middle incomes, and without a degree level qualification. This group has been identified as both being particularly vulnerable to economic change, and relatively poorly served by current government support. The government announced £100m of funding for the NRS in the autumn budget 2018.

The Treasury also recently announced a £400m funding package for 16-19 provision, marking a funding rate increase for the first time since 2013. This includes £45m aimed at supporting the delivery of T levels and £35m for targeted interventions to support students on Level 3 courses to resit GCSE/level 2 maths and English.[footnote 17]

For these reforms to work and outcomes to improve, it is vital to improve the evidence on what works, and to share knowledge and best practice.

4. The review

4.1 Aims of the review

This review draws together and maps causal evidence and associated implementation evidence to better understand what works to improve attainment for disadvantaged learners in FE and why.

The primary focus is on interventions that can prove causality and aim to improve attainment (gaining qualifications or credentials) for disadvantaged students aged 16 and over, excluding apprenticeships. The approach to the review means that other outcomes including enrolment, engagement/attendance, achievement, and social and economic outcomes are captured too as they link to attainment but were not the primary focus.

Further work would be needed to fully assess what works for disadvantaged learners throughout the learner journey (access, participation, and progression into employment or further learning). This would offer lessons on what works to improve accessibility and engagement through to progression outcomes including economic and social.

4.2 Methods

Criteria for review

Inclusion criteria were developed to ensure that the studies are relevant to the parameters of the research. The criteria for the review are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1: Criteria for review

Population:

Disadvantaged students aged 16+. Primary factors of disadvantage include socio-economic background (for example, eligibility for free school meals), and having a basic skills need (for example, students whose highest qualification is below Level 2). Disadvantaged groups include young adult carers, care leavers, Black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) learners, learners with learning difficulties and disabilities, and learners with an English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) need.

Interventions or programmes:

Initiatives that aim to improve attainment. Eligible interventions must include an educational/learning component. Types of intervention include financial incentives, comprehensive student support services, use of technology in the classroom, revised curriculum or behavioural nudges and communication.

Outcome:

The primary outcome of interest is attainment (defined as education qualification (vocational or academic) or levels achieved). Secondary outcomes include increased motivation, attendance and labour market outcomes.

Study design:

Impact evaluations that seek to understand the causal effect of interventions, including experimental, quasi-experimental and non- experimental designs. Studies must include the use of a control group.

Geography:

Studies from OECD countries published in English

Date:

1990 onwards

Search strategy

Using the inclusion criteria, we identified precise search terms and synonyms to conduct a comprehensive search of a wide range of sources. This included academic databases (for example, the Applied Social Science Index, the British Education Index and ProQuest (including ERIC), specialist research institutes (including Centre for Vocational Education Research, National Foundation for Educational Research, MDRC, National Centre for Postsecondary Research), government websites (Department for Education, Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy and Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government) and think tanks and other organisations with an interest in improving outcomes for disadvantaged students (L&W, Nuffield Foundation, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, Impetus, and NCVO).

We also scrutinised reference lists of studies retrieved to identify additional papers and hand searched contents pages of specific academic journals. For example, Journal of Youth Studies, Journal of Vocational Education and Training and Research in Post-Compulsory Education. We issued a call for evidence to identify missing evidence.

Study selection

Titles and abstracts of studies returned through the search strategy were screened against the inclusion criteria. This created a long list of 304 studies.[footnote 18] Studies on the longlist were assessed for eligibility based on the full text and a final shortlist of 63 studies was created. Most of the studies were excluded based on their study design; studies were based on qualitative research methods and therefore did not robustly assess the effectiveness of an intervention.

Quality assessment

The shortlisted studies were quality assessed using the Maryland scale which measures the quality of a study based on methodology, risk of contamination, attrition rate, sample size and date.[footnote 19] The higher the quality rating, the higher confidence we have in the effectiveness of the intervention.

4.3 Quality and nature of the evidence

Much of the literature (both systematic reviews and impact evaluations) on what works to improve attainment among disadvantaged students in the FE and adult learning sector note the lack of robust evidence.[footnote 20] The authors of a Skills for Life study note that most studies on literacy and numeracy provision have been small-scale and qualitative. Moreover, the quantitative studies that do exist tend to measure change and progress among learners, but do not use a comparison group to identify the causal effect of the intervention.[footnote 21] Given this evidence gap, there is a general call from the research community to prioritise an evidence-based system to build knowledge of how best to support disadvantaged learners.[footnote 22]

The majority of studies in this review, 52 out of 63, are evaluated through randomised control trials (RCTs). These studies offer the most robust evidence on the effectiveness of interventions to improve disadvantaged learners’ attainment. RCTs – where individuals are randomly assigned either to a treatment or a control group – are considered the ‘gold standard’ because random assignment helps to ensure that any changes in programme participants’ outcomes are caused by the intervention, as opposed to other factors. These studies give us a high degree of confidence that outcomes can be attributed to participation in that specific programme. Most of these studies are from the United States.

At the next quality level down are studies which used a matched control group to create a ‘counterfactual’. The counterfactual was used to test the difference between the group that underwent ‘treatment’ and the group that did not, in order to assess the level of impact. A small number in this review use this type of methodology.

The majority of the literature returned on the initial search met the inclusion criteria in terms of population, programme type and outcome, but not the criteria for the study design. They offer relevant, in-depth data about participant barriers to, experience of and outcomes of learning for disadvantaged groups, but do not provide causal evidence on what works to improve attainment.

Considering comparability and transferability

Given that most of the studies in this review are from the United States, it is important to consider the extent to which they are transferable to the UK context. As the focus is on practical and pedagogical interventions (for example, mentoring, basic skills provision, occupational training) and not systemic or institutional (for example, education policy or institution-wide management reforms) changes, lessons can be drawn more easily from the approaches taken. However, further investigation is required to assess the transferability of some interventions, such as residential training.

The outcome measures used in US studies (primarily General Educational Development (GED) receipt and credits earned) can be roughly equated to qualifications levels in the UK skills system. However, it is important to caveat that the systems cannot be compared like for like, placing limitations on transferability. These are explained in more detail in Box 1.

A second limitation to consider is that many of the US studies are set in community colleges which tend to serve the post-18 cohort, presenting a gap in evidence on the 16-18 cohort.

Box 1: Outcome measures

Attainment:

Definitions of attainment are primarily driven by education qualification (vocational or academic) or levels achieved. For example, receipt of a qualification or credential that

indicates the learner has reached a certain level.

Attainment measures in this review include GCSEs, and Functional Skills qualifications (Level 1 and Level 2). Additionally, the GED is a primary attainment measure in many US studies. The GED is a set of tests that when passed certify the test taker (American or Canadian) has met high-school level academic skills. The UK equivalent is a Level 3 or A level qualification.

Achievement:

Achievement means distance travelled or progress made. For example, many studies in the review use number of credits earned as a positive indicator of academic progress. Earning credits can either contribute towards a ‘credential’ (a qualification or certificate) or towards transferring to a 4-year degree level programme. Other studies use scores on standardised literacy and numeracy tests to measure achievement or progress.

Box 2: Types of interventions

Multiple interventions are programmes that comprise 2 or more of the following: tutoring, counselling and/or advice, financial support, basic skills provision and occupational training. Examples include CUNY ASAP, lnstituto del Progreso Latino’s Carreras en Salud programme, The Valley Initiative for Development and Advancement programme and Project QUEST.

Basic skills interventions are programmes delivering language, literacy and numeracy provision (English, maths and ESOL). In England, these courses are taught at Level 2 (approximately GCSEs of grades A* to Cl 9 to 4) and below. Examples include the Community-based English Language (CBEL) programme, the Skills for Life programme and the Welfare to Work programme. Basic skills interventions include remedial or development programmes in the US. Examples include the GED Bridge programme.

Accelerated learning interventions are intensive forms of provision delivered over a short-time period, for example a semester (3 to 4 months). They aim to prepare students for college-level courses. Examples include the CUNY Start programme.

Occupational training interventions are primarily focused on delivering occupational training with the aim of increasing participants’ employment and earnings. Examples include Integrated basic education and skills training (I-BEST), The Workforce Training Academy (WTA) Connect Program, Madison Area Technical College Patient Care Pathway Program, Traineeships and Greater Avenues for Independence (GAIN) Program.

Behavioural interventions are interventions that include relationship building, adapting the environment, managing sensory stimulation, changing communication strategies, providing prompts and cues, using a teach, review, and reteach process and developing social skills. Examples include the Behavioural Research Centre for Adult Skills and Knowledge (ASK) interventions.

Digital interventions are provisions which use Information Communication Technology (ICT), online and blended as a learning approach or medium. Examples include ModMath and the INVEST programme.

Financial interventions are monetary stipends or support. Examples include the MAPS programme and the 16-19 bursary fund evaluation.

Innovative pedagogy interventions test a pioneering approach to teaching. Examples include the Dana Center Mathematics Pathways (DCMP).

Mentoring is provision that is delivered on a one-to-one basis or in groups no larger than 2-3 students. An example is the Beacon Mentoring programme.

Learning communities are designed to give students a chance to form stronger relationships with each other and their instructors, engage more deeply with the integrated content of the courses, and access extra support. Examples include Kingsborough College Learning Communities programme.

Residential interventions involve participants living at the programme site and participating in various support elements including basic skills provision, occupational training and mentoring. Examples include Jobs Corps and the National Guard Youth ChalleNGe programme.

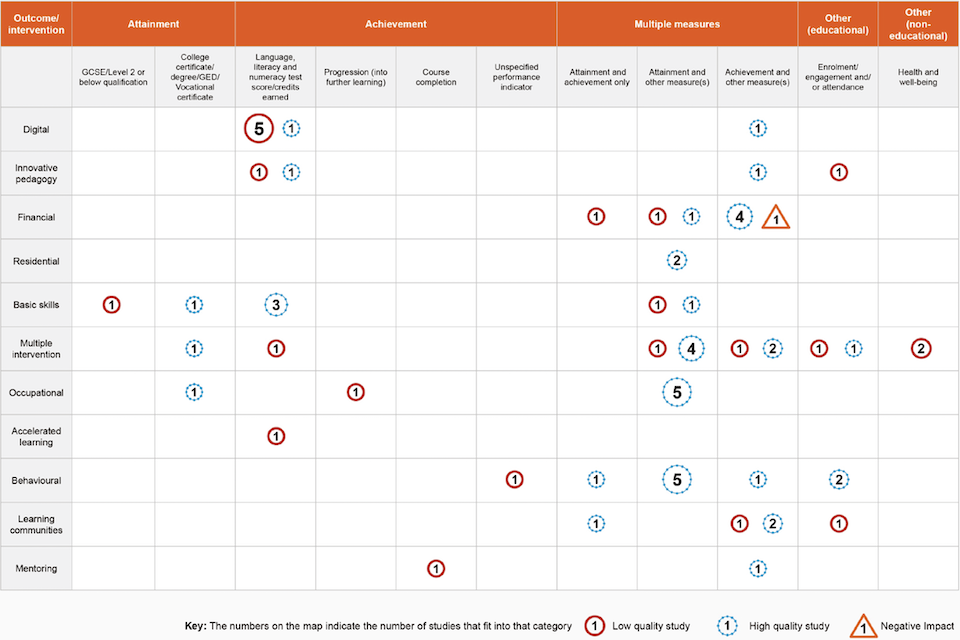

Interventions and educational outcomes: evidence and gap map

The map below illustrates the evidence identified for interventions aimed at improving the attainment of disadvantaged learners. The y-axis shows the type of intervention and the x-axis illustrates the type of attainment measured.

From the cluster of circles in the centre of the map, it is clear that there is a predominance of US studies. Whereas the gap in evidence on the left-hand side of the map demonstrates the overall lack of research from the UK context.

Studies included in the review predominantly explore the effectiveness of behavioural interventions, financial incentives, occupational training (that has a basic skills component), and multiple interventions – those that have a comprehensive support offer.

There is less evidence on the effectiveness of innovative pedagogical approaches, one-to-one or small group support. There were also only 2 studies exploring residential interventions, although these programmes have limited transferability to the UK context.

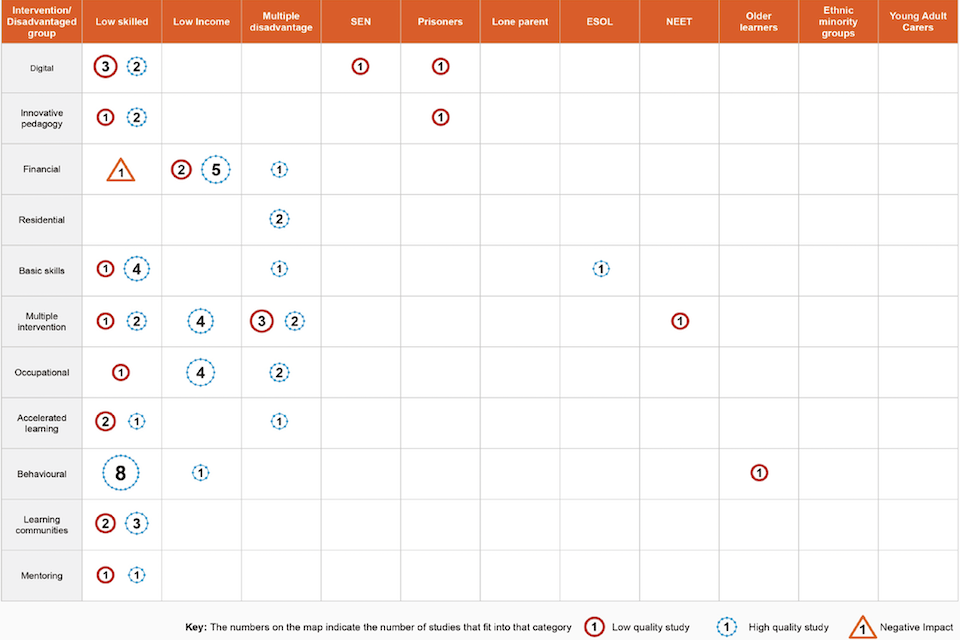

What works for whom: evidence and gap map

The map below illustrates the evidence identified for interventions aimed at improving the attainment of different groups of disadvantaged learners. It plots types of intervention against different learner groups.

The majority of interventions target low-skilled individuals, with the largest number of interventions investigating the effectiveness of behavioural approaches for this group. Not surprisingly several interventions for low income learners examined the impact of financial incentives on attainment, which provided mixed results. Most of the programmes designed to support low-income groups involved occupational training programmes, which all produced positive results.

This map clearly shows the number of gaps in the evidence relating to other disadvantaged groups. No studies were identified that concentrated solely on Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) groups. It is also noteworthy that there are only single studies relating to individuals with special educational needs (SEN), lone parents, adults with an ESOL need and youths not in education, employment or training (NEET). Furthermore, there was no evidence found on examining what works to support young adult carers or care leavers. This shows that further research, which targets these groups of disadvantaged students, is needed.

5. The findings

5.1 How effective are the interventions?

This section considers the effectiveness of programmes designed to support disadvantaged students. Given the scope and aims of this review, effectiveness or impact is primarily measured by attainment. Other outcomes measured include achievement (or progress}, attendance and retention, and wider outcomes such as soft skills (for example, confidence and social skills) and labour market outcomes.

Attainment

Programmes designed to support disadvantaged students improve attainment can have a significant impact on individuals’ attainment of basic skills qualifications. Studies found significant improvements in learners’ basic skills attainment including English and maths Functional Skills and GCSE attainment and the equivalent attainment levels in the US. A behavioural intervention that used texts and social support improved Level 2 attainment rates by 24% (5.1 percentage points, from 21.1% to 26.2%). In the same study, reflective writing exercises improved attainment in maths and English by 25% (4.2 percentage points, from 16.7 to 20.9%). These behavioural interventions measured attainment and attendance. The results for attainment were statistically significant whereas some of the effect sizes for attendance were not.[footnote 23] Similarly, a study testing innovative approaches to delivering basic maths courses found that attainment among the participant group improved with a mean difference score that was nearly twice that of the control group.[footnote 24]

However, some studies show little to no improvement in attainment. The evaluation of the Pathfinder Extension (a comprehensive model of basic skills provision) for example, found no positive impact on receipt of basic skills qualifications.[footnote 25]

Programmes designed to support disadvantaged students can improve attainment of qualifications, including GED and degrees. Findings from 3 studies show that programmes can also have a significant positive impact on GED completion and receipt.[footnote 26] In the GED Bridge programme which tested a new approach to teaching the GED preparation course, Bridge students were more than twice as likely to pass the exam than those on the traditional course (53% and 22% respectively). Three-year effects of a CUNY ASAP (see table 5.2 for more detail) found that 40% of the programme group received a degree, compared with 22% of the control group.[footnote 27] Additionally, the evaluation of Project QUEST (a comprehensive support programme supporting low-income adults) 6 years post-randomisation shows that participants were significantly more likely than control group members to earn a postsecondary qualification – 75% and 57.2% respectively.[footnote 28]

There is some evidence that while interventions do have an impact on attainment, the effect size can be modest. A long-term study of a learning communities programme (see Box 3.2 for details on the learning community approach) estimates that the programme only increased graduation rates by 3.3% (with 39.5% of programme participants and 36.2% of control group participants earning a degree).[footnote 29] Four years after a programme aiming to prepare students for college by providing enhanced courses and student services began, only 7.6% of programme students had earned a degree or certificate, compared to 6.4% of the control group, representing a small effect size on attainment.[footnote 30]

Achievement

Financial incentives and basic skills programmes have been found to have a positive effect on skills development. There is evidence from the US that programmes have a significant impact on developmental maths and/or English credit attainment (increased number of credits earned), test scores in literacy and numeracy, and completion rates of basic skills courses.[footnote 31] For example, the US National Workplace Literacy Program which measured changes in learners’ basic skills by using pre-and post-intervention skills assessment tests, generally found significant improvements in learners’ basic skills.[footnote 32] The CBEL programme – an intervention aimed at adults with very low levels of functional English proficiency – found similar levels of effectiveness, with programme participants achieving speaking and listening scores that were double that achieved by the control group.[footnote 33]

Improved achievement can support progression in to further and higher education. For example, CUNY Start (an accelerated learning programme aiming to prepare students for college) found that by the end of the programme semester, 57% of programme group students were college-ready in maths, compared with 25% of control group students.[footnote 34] Additionally, by the end of the programme, 38% of programme group students were college-ready in all 3 subject areas (maths, reading and writing), compared with 13% of control group students. There is also evidence that programmes are effective in supporting adults to achieve college-level credits and pass college-level courses.[footnote 35] An innovative pedagogy model – the DCMP programme – found that 27% of programme group students enrolled in college-level maths and 18% passed the course, rates more than double those of students taking traditional courses.

These results were sustained over 3 semesters.[footnote 36]

Despite encouraging short-term effects, some studies demonstrate that achievement over the longer-term may not be maintained or lead to improved attainment. For example, ModMath – a basic maths course delivered via computer-based instruction allowing for self paced learning – found that while students made greater progress early on by earning more credits that control group students, there was no discernible difference in course completion, becoming college-ready and/or passing the first college-level maths course.[footnote 37] Most students either did not attempt all required developmental math courses/modules, failed one or more courses/modules, or did not re-enrol. Similar findings were found in other programmes – despite encouraging short-term effects, there is less evidence of meaningful improvements to students’ long-term academic progress.[footnote 38]

Enrolment, attendance and persistence

A range of different programme types have been found to have a positive impact on enrolment. Four studies provide evidence on the effectiveness of programmes increasing the number of participants enrolling on a course.[footnote 39] Often, studies found that programme students may be more likely to take up a full-time course than control students who opt for part-time study.[footnote 40] They may also be more likely to enrol on more than one new course at the start of the programme.[footnote 41] However, it is noted that increased enrolment is most likely attributable to the programme starting at the same time.[footnote 42]

Programmes have been found to have a mixed impact on attendance. The ASK behavioural interventions (see Box 2 for more detail) found significant improvements in attendance on basic skills courses.[footnote 43] Overall, the PACE programmes found a significant increase in the amount of education or training received (hours attended). One study testing the effect of a £5 incentive for every class attended found it had an adverse effect on learner attendance. The authors suggest that the programme should be replicated with a larger incentive.[footnote 44]

Short-term programmes may not improve persistence, retention, and/or progression into further education. There are a number of studies evaluating programmes that last a semester (3 to 4 months long). Overall, short-term interventions tend to lead to modest impacts that are concentrated in the duration of the programme. The evidence suggests that these by themselves are not typically sufficient to boost re-enrolment or lasting changes to students’ progression.[footnote 45] For example, the DCMP study (see Box 2) found that over 85% of students from both groups were registered for courses during their first semester in the study, but less than 50% were still enrolled in college by their third semester, underscoring the challenge that community colleges face to supporting students to persist from semester to semester.[footnote 46]

Studies that track long-term outcomes often find that programme students do not maintain progress. For example, an evaluation of a PBS found that credits earned, and rates of persistence declined over the programme’s lifetime.[footnote 47] In the first year, programme students earned an average of 15.9 credits, compared with an average of 14.2 credits in the control group - an estimated impact of 1.7 credits. In the second year of the study, after the scholarship ended, programme group students earned an average of 0.7 credits more than control group students. Finally, in the third and fourth years, the number of credits earned was, on average, the same for both groups. Studies that find positive enrolment effects tend to be presenting early findings rather than tracking outcomes over the longer term.[footnote 48]

Wider impacts

Interventions can impact on learners’ soft skills including their self-confidence, employability and social integration. There is evidence of programmes having a positive impact on students’ self-management, independence, self-awareness, interest in lifelong learning, emotional intelligence, and engagement in college.[footnote 49] The CBEL programme found a significant impact on social integration measures, including confidence interacting with services and social interactions.[footnote 50] The ASK interventions found that building non-cognitive skills as part of a course can have an impact on whether an individual succeeds in education.[footnote 51]

Studies show positive impacts on employment outcomes. Some of the studies in this review are evaluations of sectoral or occupational training programmes for low-income, low skilled adults, and therefore measure employment outcomes in addition to attainment and achievement. Some show a clear impact on participants’ earnings. For example, results from the Year Up intervention (a comprehensive support model including occupational training, basic skills provision and financial support) show a 53% increase in earnings for the treatment group (their average quarterly earnings were $5,454, compared to the control group members earning $3,559 on average).[footnote 52] Another of the PACE programmes showed a 9-percentage point increase in employment in a healthcare occupation (25% for treatment group members versus 16% for control group members).[footnote 53] However, employment progression was into low-paying positions.

It is argued that progression into higher paying jobs and/or higher-skill jobs may take more time to achieve, highlighting the importance of tracking outcomes over the longer-term. The Welfare to Work programme which provides GED preparation courses, basic maths, English and ESOL courses to highly disadvantaged adults, showed that as students’ skills levels increased and reached certain attainment benchmarks, they appeared to have substantial benefits in terms of employment, earnings, and self-sufficiency.[footnote 54] The latest evaluation of Project QUEST shows it had a large positive impact on career-advancement over a 6-year period.[footnote 55] For example, QUEST participants earned $5,080 more than control group members in the sixth year after study enrolment.

Further work would be needed to fully assess studies that examine economic and social outcomes.

5.2 What types of approaches are likely to be effective?

This section explores the types of interventions that work to improve outcomes for disadvantaged adult learners.

Evidence on the effectiveness of basic skills interventions is mixed. Both the CBEL and US workplace literacy programmes sizably improved learners’ language and literacy skills compared with the control group. In the latter programme, more than 85% of workers who attended a workplace literacy course scored higher than the typical worker in the control group.[footnote 56]

As discussed in the previous section, the Welfare to Work Program, which included a range of basic skills provision, improved participants’ skills levels, GED receipt and enrolment into further postsecondary learning compared to the control group. However, only a small proportion of the programme participants increased achievement and attainment. Those that did pursue further learning appeared to experience substantial benefits in terms of increased earnings and self sufficiency, indicating a positive snowball effect for a small proportion of participants.[footnote 57] The Skills for Life evaluation found modest improvements in programme participants’ literacy and numeracy skills, but overall no significant difference between them and the control group.[footnote 58] One study exploring the effects of a basic skills programme in the US shows positive impacts on achievement and short-term persistence, but no evidence that the course increased completion of college-level credits or degree completion.[footnote 59]

There is evidence that suggests interventions that include multiple support strands can work to improve outcomes. There is evidence in the 3 evaluations of CUNY ASAP, which included financial support, personal advisers, flexible provision and career specialists, to suggest that the comprehensive support model offered to low-income, low-skilled students works to improve enrolment, persistence and attainment.[footnote 60] The first ASAP programme substantially improved students’ academic outcomes over 3 years, almost doubling graduation rates, increasing the number of credits earned and increasing enrolment on higher education courses compared to rates among the control group. Given these unprecedented findings, the model was rolled out and evaluated in other community colleges, with findings that corroborate. Other programmes such as the Valley Initiative for Development and Advancement and Project Quest, which offered combined provision support these findings.[footnote 61]

However, the Opening Doors programme, which provided 2 elements of support – enhanced student services in the form of regular and intensive support from a college counsellor and a modest stipend – found that any positive impact was limited to the programme lifetime.[footnote 62]

Innovative pedagogical approaches can work to improve attainment and persistence. All 3 studies included in this review under the category of ‘innovative pedagogy’ resulted in a positive impact. The DCMP report found that programme participants were more likely to pass the basic maths course than the control group.[footnote 63] Gains for the programme students continued to be observed (measured by enrolment in and passing a college-level maths course) in the following 2 semesters. These findings indicate that this model can help students reach a critical college milestone: making it to and through a college-level math course. Innovative pedagogy was also effective in teaching adults basic maths in FE colleges in England and delivering a basic literacy course to low level readers in the US.[footnote 64]

Occupational training interventions that embed basic skills content can improve attendance, attainment and progression into further learning. The Traineeships programme in England increased the likelihood of programme participants moving into further learning: 42% of trainees were in further learning 12 months later, compared with 29% of the matched comparison group.[footnote 65] There was also a significant impact on gaining any positive outcome within 12 months.[footnote 66] The Jobs Corps programme, I-BEST and Pima Community College Pathways to Healthcare programme were also found to increase college course enrolment, credits earned and credential attainment.[footnote 67] However, results from other PACE programmes which are categorised as occupational training such as the WTA Connect Program and Madison Area Technical College Patient Care Pathway Program show limited impact on educational outcomes.[footnote 68]

Similarly, there is evidence to suggest embedding vocational content in essential skills provision works well for students preparing for the GED exam – programme participants had higher course completion rate, exam pass rates and were more likely to be enrolled in college than the control group.[footnote 69]

Behavioural interventions have mixed results. The ASK interventions found that programmes that provide learners with encouragement, social support, the opportunity to reflect on why they value learning and feedback to highlight effort and performance can be particularly effective – improving attainment and attendance.[footnote 70] One of the most effective interventions incorporated both weekly text messages of encouragement to learners and updates to their social supporters (family and friends of the learner). Further, a short writing exercise, in which learners reflected on their personal values and why they are important to them, also improved attainment.

A US study which explored the impact of a programme providing low income individuals with personal assistance for student loan applications found that this financial ‘nudge’ led to increased college attendance, persistence, and aid receipt compared to those who received information about the loan but no personal assistance.[footnote 71]

Other studies have evaluated ‘student success’ courses that focus on changing students’ behaviours and attitudes, including increasing their awareness of their and others’ emotions, understanding their own learning styles, improving time management skills, and recognising their responsibility for their own learning to prepare them for community college.[footnote 72] Although findings demonstrate a positive impact on students’ behaviour (for example, self-management, interdependence, self-awareness and interest in lifelong learning), there is little evidence to suggest that this approach improves educational attainment or achievement long-term. Four years after one of the studies began, programme and control group students had made similar academic progress.

Digital interventions may improve engagement for some students but do not appear to be any more effective than traditional basic maths and literacy courses in raising completion levels or attainment. A US evaluation of adult basic education programmes that used ICT products to facilitate learning of basic skills found that most instructors and students reported positive experiences of using ICT, suggesting a positive impact on engagement.

However, the impacts on skills assessment results were mixed.[footnote 73]

Other evidence suggests that digital interventions have a modest impact on student outcomes. Modmath (see Box 2) and a UK study examining the effects of a computer-assisted instruction intervention on basic numeracy skills for adults with learning disabilities found that the approach was no more or less effective than the traditional course which was teacher-led.[footnote 74] Similarly, a 4-week educational programme with computer assisted instruction designed to raise prisoners’ achievement on maths and reading tests found no significant difference in scores between the programme and control group.[footnote 75] Two studies from the early 1990s found computer-based learning to have similar limited impact.[footnote 76] Although the second, the INVEST programme, shows that computer-based approaches may work more effectively for improving maths skills than literacy skills.

Accelerated learning or intensive courses may produce short-term improvements, but the evidence suggests impacts may decline over time. A bridge course designed to support students with basic skills needs build competencies over the course of several weeks before entering college had some impact on first college-level maths, reading and writing course completion.[footnote 77] However, by the end of the 2-year follow-up period there was no difference in attainment or persistence. For example, the programme group enrolled in an average of 3.3 semesters, and students in the control group enrolled in an average of 3.4 semesters, a difference that is not statistically significant.

A study exploring the effectiveness of accelerated learning on developmental students’ outcomes in English classes found that programme participants were more likely than the control group to attempt and pass developmental English courses and persist to the next year to attempt and complete more college-level English courses than the control group. However, the 2 groups were equally likely to earn an associate degree or transfer to a 4-year higher education college.[footnote 78]

Financial incentives can work to improve educational enrolment, attendance, attainment and persistence. Three of the studies in this review evaluate the impact that Performance Based Scholarships (PBS) have on community college learners’ engagement, enrolment and earning of college credits (see Box 2 for more details). The studies have positive results including increasing number of credits earned, having a positive effect on full-time enrolment and decreasing the time it took students to earn a degree.[footnote 79] Strong support for the value of financial incentives also comes from the ASK behavioural intervention trial which found that a cash ‘buddy incentive’ – incentives that were only awarded to learners where both buddies achieved the attendance target – achieved higher attendance than those in the individual incentive group, showing that an incentive that incorporates a social dimension can be even more effective.[footnote 80] Similarly, positive results were found in a programme offering financial incentives for low-income parents attending community college. Programme participants had higher pass rates and earned more course credits than the control group. Programme participants also had higher rates of registration in colleges in the second and third semesters after random assignment compared to the control group.[footnote 81]

Financial incentives and support can also work for younger adults. The impact evaluation of the 16-19 bursary fund (following the removal of the Education Maintenance Allowance) found that participation rates in full-time learning dropped by 1.6 percentage points. Estimates show that there was a 2.3 percentage point fall in the Level 2 achievement rate by age 18, leading to a 1.1 percentage point fall across the whole Year 13 cohort, from 88.3% to 87.2%. The authors attribute these changes to the removal of the maintenance allowance.[footnote 82]

Conversely, a study testing whether bi-weekly instead of termly disbursement of financial aid works to improve students’ academic outcomes, found no substantial impact. This indicates that the timing of receipt of financial aid may not have a significant bearing on student outcomes.[footnote 83]

One-to-one, mentoring and small group support can significantly improve persistence and completion and may work to support ‘at risk’ groups’ attainment. While the Beacon Mentoring programme (see Box 2 for detail) had no impact on attainment overall, sub-group analysis shows that ‘high-risk’ students (learners referred to developmental maths rather than college-level, therefore at higher risk for poor outcomes) were significantly less likely to withdraw from the maths class and earned a significantly higher percentage of credits per attempt compared to the control group.[footnote 84] Another study testing 3 different types of educational intervention: team approach (approximately 14 students, a teacher and a counsellor), small group approach and individual tutoring found that the small group approach (4-6 students to 1 tutor) had the most significant impact on completion rates among ‘at risk’ adults and adults who had previously dropped out of adult basic education.[footnote 85] 60% of students in the small group completed 3 months or more compared to a 40% completion rate for those in the team group, and a 20% completion rate for those being tutored individually.

Evidence on the effectiveness of learning community interventions is mixed. Learning communities are a popular strategy in the US to boost low success rates, particularly among students who take up basic English and math provision. Five of the studies in this review explore their impact, but with mixed results. One study found that learners earned significantly more credits than their control group counterparts and maintained this result for 7 years post-randomisation, indicating the long-term effect on their academic progress.[footnote 86]

However, some of evidence shows that while learning communities appear to have an impact on students’ achievement (measured by pass rates of developmental classes) during the programme semester, this effect diminishes over time with no impact on college enrolment or cumulative credits earned in the semester following the programme.[footnote 87]

5.3 What works for whom?

There is limited evidence on what works to improve attainment for different sub-groups of disadvantaged students. Most studies included in this review present analyses for the sample as a whole, telling us what works for the cohort in general. Fewer studies conduct sub-group analysis. Nevertheless, the evidence that does exist provides some learning on the following student characteristics.

Distance from learning

Some studies combine sub-group analysis findings to demonstrate the programme’s impact on ‘non-traditional’ students. For example, Project QUEST found that impacts were greatest among participants aged 25 and older, and those who had a GED rather than a high school diploma.[footnote 88] This indicates that QUEST was particularly successful in reaching into the community to engage people who were unlikely to navigate their way through postsecondary training to a good job on their own. Using proxy indicators for distance from learning based on age and date of receiving High School Diploma or GED (since there was no measure of ‘time since taking last maths class’ available), the MAPS study – a PBS programme that offered access to a maths lab -also found that the intervention had a more positive impact on adults who were considered less likely to take up education upon enrolment. This suggests that a financial incentive may be effective to motivate disadvantaged adults to take up basic skills provision. Another study found that teaching adults in small groups had the most significant impact on completion rates among adults who had previously dropped out of adult basic education.[footnote 89]

In contrast, the Skills for Life learning evaluation found that older learners, those with children and those who believed they had a literacy problem were less likely to achieve Level 2 English and maths qualifications. This suggests that attainment appeared to be linked to distance from learning. As QUEST adopted a multiple intervention approach, whereas the Skills for Life programme was the delivery of basic skills courses, these findings indicate the effectiveness of comprehensive approaches to supporting disadvantaged students.[footnote 90]

Age

Evidence shows that the effectiveness of interventions differs for different age groups. Two programmes targeting young adult learners (16 to 24-year-olds) found that the intervention had a stronger impact on the older sub-group of the cohort. For example, for participants aged 19- 23, Traineeships had a positive impact on being in employment 12 months later. In contrast, there was no significant impact for the younger cohort of those aged 16-18.[footnote 91] The ChalleNGe programme found similar results that staff attributed to higher levels of motivation and focus among the older group.[footnote 92]

Previous educational attainment/level

Some studies show that interventions worked particularly well for lower level learners. For example, ASK behavioural interventions and the CUNY Start programme were most effective for students who had the highest skills need. ASK may have had a more powerful impact on lower level learners because it introduced elements that met lower level learners’ needs.[footnote 93] For example, social support, or an intervention which addresses anxiety about learning or self-doubt about their ability to keep learning. Similarly, the Beacon Mentoring programme targeted students enrolled in lower level maths courses, who had a high degree of failure.[footnote 94] While the programme had no impact on attainment overall, the introduction of mentors had a significant impact on progress of students who had the lowest skills levels.

In contrast, other studies found that positive outcomes were more pronounced for participants who had higher skills levels. For example, GAIN (see Box 2) and a Learning Communities programme found that educational gains were concentrated among participants who had relatively high levels of literacy when they started the programme.[footnote 95] Similarly, the CBEL trial found that previous higher educational attainment was a significant predicator of improvement in proficiency, which could indicate a familiarity with class-based study, or aptitude to learn. An evaluation of digital learning for adult basic literacy and numeracy uncovered challenges in using computer-based learning approaches with low-skilled adults. In recognition of this, the authors concluded that for those with the lowest skills, blended and hybrid models of learning with instructors delivering 50% or more of instruction would possibly be more effective.

The Skills for Life evaluation presents mixed results. Progression increased as course level decreased, suggesting a positive impact on the least skilled students. However, students with Level 3 qualifications were also more likely to progress, as were those who had stayed in education beyond the age of 18.[footnote 96]

Financial dependency

The MAPS intervention found that the intervention was more impactful for financially independent students, compared to those who were financially dependent. The authors argue that this indicates that a monetary incentive may be a more salient motivating factor for adults who are in charge of their own financial situation.[footnote 97]

The impact evaluation of the 16-19 bursary found that the move from the Education Maintenance Allowance (EMA) to the bursary most negatively impacted the most deprived students.[footnote 98]

Ethnicity

The MAPS analysis also suggests that the programme was most effective for BAME students (except those who responded as Hispanic) and less effective for those who identified as white. A subgroup analysis showed that CUNY Start has positive effects for students across all racial and ethnic groups, and, in particular, for Asian students enrolled in English courses, and black and Hispanic students enrolled in maths. A preliminary exploration of achievement gaps suggests that CUNY Start may effectively shrink achievement gaps between black and white, and Hispanic and white students in maths.[footnote 99]

5.4 Cost-effectiveness

The overwhelming majority of studies included in the review do not provide evidence on programme costs, or cost-effectiveness. A small number of studies presenting early impacts of programme note that it is too soon to produce such analysis and that future reports will focus on cost-benefit analysis. This section presents evidence that does exist on intervention cost and cost-effectiveness.

Evidence suggests that high-level investment can produce large enough impact to make the programme cost-effective. CUNY ASAP generated significantly more graduates than the usual college services. Therefore, despite the substantial investment required to operate the programme (the college invested $16,284 more per ASAP group member than it did per control group member, or 63.2% above the amount spent on the typical student receiving usual college services), the increase in the number of students receiving degrees outpaced the additional cost.[footnote 100] Similarly positive results were seen in the MAPS programme. The investment of between $1,394 and $1,863 more per student in the programme than per control group resulted in a 5.6 percentage point increase in the likelihood of completing a college-level maths course. This impact is large enough that it lowers the cost per course completion compared with the usual college services without the programme.[footnote 101]

Evidence suggests that some programmes are not cost-effective. There is some evidence that resource-intensive programmes may not be cost-effective. For example, Job Corps cost $16,500 per participant. Results of the cost benefit analysis over 4-year survey period found measured benefits were less than $4,000; therefore, programme costs exceed programme benefits.[footnote 102] Implementing biweekly disbursements of financial aid was also found to be burdensome and costly. The more frequently biweekly payments were recalculated to account for changes in students’ circumstances (for example, numbers of courses taken), the more expensive it was to maintain the system of incremental disbursements.[footnote 103]

The evaluation of the 16-19 bursary fund estimates that despite short-term savings, the policy made an overall loss to the exchequer of £84 million (which authors state is likely to be an underestimate).[footnote 104]

Some studies estimate high ‘start up’ costs of provision but argue that this cost would reduce over time. An evaluation of 8 summer bridge programmes estimated that the cost per student ranged from $835 to $2,349. However, the authors state that some costs may be interpreted as “start-up” costs, which are unlikely to be needed if the programmes are run in subsequent years. They also suggest embedding support programmes such as these into the regular high school or college schedule would reduce costs.[footnote 105]

Interventions that use text messages to encourage learners’ attendance and achievement were found to be particularly cost-effective methods. The ASK behavioural interventions trials found that the estimated costs of the text message intervention in FE colleges was less than £5 per learner, including the cost of the messages and staff time. An intervention that texted parents to explain how easy the enrolment process was found that at £10 per additional enrolment for the most effective message, it was a cost-effective way to increase enrolment.[footnote 106]

Learning community interventions appear to be low-cost relative to costs overall. The cost per student of learning communities appeared low when compared with how much community colleges spend on average per student. A recent analysis of national postsecondary education expenditures in the US estimated that community colleges spent an average of about $12,000 per year to educate each full-time student. When the cost of learning communities is assessed against this value, the costs appear incremental and may be justifiable to the college, if value is derived from running the programme. However, there are implications on the value given that this approach has minimal impact on student outcomes.[footnote 107]

5.5 Delivering interventions

This section draws on the findings from the evidence, which offer lessons for the design and delivery of learning interventions.

Recruiting learners

Proactive and innovative approaches can help to overcome challenges in recruiting disadvantaged learners. The PACE programmes, which were successful in meeting their recruitment targets, took a proactive approach to engagement and developed new recruitment methods and tracked referral sources to improve target methods.[footnote 108] For example, one of the PACE initiatives extensively marketed the programme through media, partners and word-of mouth referrals.[footnote 109] Potential applicants wanting further information prior to applying were able to attend an optional monthly orientation session to learn about the services, eligibility and participation requirements. Potential applicants were also given information on the certificate or degree programmes the initiative supported.

Appropriate selection of key referral partners is vital. An example of the importance of the role of referral partners is illustrated in the Youth Contract programme, which aimed to support 16-24-year-olds to participate in education, training and work. One of the delivery models devolved the funding to 3 core city areas, where 6 local authorities determined the shape and nature of delivery. This meant that the eligibility criteria were determined locally, based on local priority and need. The evaluation found that engagement with local authorities was crucial as they held data, which was an important source of information for targeting appropriate local populations.[footnote 110] Furthermore, delivery agents conducted outreach to support the identification and engagement of learner populations who are hard-to-reach, such as those not in education, employment or training.

However, not all partnerships resulted in increased recruitment. One programme where learning took place in the workplace found that employers responded to applicants with GCSEs, rather than those with equivalent level Functional Skills qualifications.[footnote 111] The authors also noted that voluntary work experience of potential learners did not improve response rates from employers. The authors concluded that more research is needed in this area.

Enrolment

Pre-enrolment sessions that raise awareness of student services and build social networks can be beneficial. The ModMath Programme (a modularized, computer-assisted, self-paced developmental maths course) sought to address these barriers, by offering potential students preparation, or taster, courses prior to enrolling on the full course.[footnote 112] The information provided via the ModMath initiative included briefings about the educational setting (for example, student services and campus navigation and soft skills, such as study and problem solving skills). This approach also fostered a sense of community among the learner cohort.

Registration to the programme also opened early, to enable students to choose the courses they wanted to enrol on well in advance of taking up learning. This not only enabled students to create a schedule that was convenient to them, it also increased the likelihood of enrolment on their chosen courses.

Encouraging persistence

Regular and accessible communication can encourage and motivate learners, leading to improved persistence and attainment. Communication interventions can take a number of forms, for example, one-to-one or group face-to-face sessions with an adviser, text messages, emails, phone calls. For example, The Bridge programme provided regular communication from an adviser about transition processes, such as researching future learning options and understanding entry requirements that improved learners’ knowledge about their next steps.[footnote 113] The Bridge intervention successfully built learners’ skills for achieving the GED test, as well as supporting progression into further learning.

Participation in support networks can increase learner engagement and persistence. The increase in support networks, as a result of being part of a Learning Community (which consists of other students and staff), can improve the persistence of underprepared students.

Additionally, researchers suggest that the isolation of low-skilled learners is reduced by linking their developmental course to another course, because they will be more engaged than if basic skills are taught in isolation in a stand-alone course.

Providing learners with a consistent single point of contact, such as an adviser, mentor or key worker, can be beneficial. Participants involved in a number of basic skills programmes noted the important role a consistent point of contact played in their experience of the programme and in helping them to remain engaged in courses. For example, the Moving Forward programme which provided each student with an adviser, addressed the reluctance of Latino men to ask for help because of strong notions of manhood, independence, and self reliance.[footnote 114] Higher levels of contact can also foster soft and academic skills development.

Crucial to this approach is action planning to set, record and measure goals.

Student services should be comprehensive and personalised. Student services may include academic support such as tutoring, study skills training, or practical support such as on campus childcare, or support with transport. For example, the Opening Doors Programme, assigned students to a counsellor who they met at least twice each semester for 2 semesters to discuss academic progress and to resolve any issues that might affect their schooling.[footnote 115] Researchers also recommend allocating far fewer students than the regular college counsellors to facilitate more frequent, intensive contact with the students on the programme.[footnote 116] When these services are offered via a trusted source (an adviser) and well-marketed, the evidence shows that students are more likely to access them.[footnote 117]

Provision

Provision should consider the aspirations of the target group. The GAIN in California was an occupational training intervention emphasizes large-scale, mandatory participation in basic education, in addition to job search, training, and unpaid work experience, for welfare recipients.[footnote 118] The evaluation found that GED test score gains were concentrated in the site that created an innovative adult education programme tailored to the needs of people on welfare.

Other sites where the programme was not delivered using this approach saw less impact.

Another example of the need to tailor provision is the use of digital interventions for supporting the learning of adults with basic literacy and numeracy skills. In one study, one fifth of participants did not enjoy using ICT to learn and preferred to work directly with instructors, rather than learning on-line.[footnote 119] The researchers commented that depending on the scaffolding techniques used to embed the ICT products and the availability of support from instructors, some learners could become stuck in the digital learning environment and experience frustration. This is an important consideration, particularly for learners with the lowest skills levels. Therefore, blended and hybrid models involving tutors delivering at least half of the instruction was suggested as most effective for basic skills programmes. It is therefore key that programmes need to offer additional student services for disadvantaged students to engage in.

Evidence suggests that provision aimed at improving adults’ literacy and numeracy skills is particularly effective when it embeds vocational content that aligns with students’ career aspirations and/or pathways. The National Workplace Literacy programme was designed to emphasise contextualised, job-specific instruction in basic skills for adults who lack basic skills.[footnote 120] The provision which included English, maths and ESOL was workplace-based. Results indicate that this intervention improved literacy skills, interest in further learning, engagement in literacy tasks at home and self-rated literacy skills of learners. There was also a positive impact on teamwork skills and communication skills at work.

Unlike the other PACE programmes, the I-BEST programme used a ‘team teach’ approach, meaning at least 50% of occupational training class time was delivered by both a basic skills instructor and an occupational instructor. Basic skills instructors used concepts from students’ occupational coursework as a vehicle for building basic academic skills; that is, customizing the content and instructional delivery to draw on examples from occupational content. This approach had positive results – the treatment group members received an average of 13 more credits compared to control group members, and there was a 32-percentage point increase in credential receipt.

There are beneficial outcomes for learners when training addresses both occupation specific and basic educational skills. The PACE programmes in the US included a number of studies which incorporated both educational and occupational training.[footnote 121] For example, one study focused on training for low-income Latinos for employment in healthcare occupations (primarily Certified Nursing Assistant and Licensed Practical Nurse).[footnote 122] The intervention increased the number of hours of occupational training and basic skills instruction received, as well as attainment of educational credentials within the 18-month follow-up period. Additionally, the intervention increased employment in the healthcare sector and led to a reduction in the number of participants reporting financial hardship.

Accelerated and intensive programmes can help learner engagement and developmental learning. There have been mixed results from accelerated, intensive learning programmes, however positive behavioural results have been noted. For example, an impact study of a student success course, at a US technical community college, provided intensive focus on changing students’ behaviours and attitudes (such as increasing awareness of their own and others’ emotions, understanding their learning styles and recognizing their responsibility for learning).[footnote 123] The intervention had a positive impact on attributes such as students’ self management and awareness but did not result in meaningful gains in academic achievement.

The size of learning groups can affect completion rates. Research examined 3 different types of educational intervention: a team approach, a small group approach and individual tutoring.[footnote 124] The study found that the small group approach had the most significant impact on completion rates among ‘at risk’ adults and adults who had previously dropped out of adult basic education.

Designing courses that relate to career aspirations support learner engagement and continued college participation. Interventions that take a contextualised approach have been found to have a significant motivating factor on learners.[footnote 125] Rather than developing maths, writing and reading through generic, basic skills exercises, students learnt by using materials that were specific to the healthcare or business track they were considering pursuing. One year after enrolling in the intervention, students were far more likely to have finished the course, passed the GED exam and enrolled in college, than students who had a more traditional preparation course.

Contextual approaches help make learning basic skills more relevant and meaningful. For example, one study conducted in a prison environment, used science and the natural world as a way of making reading more contextually relevant and meaningful.[footnote 126] Learners practiced and used reading skills and behaviours to learn more about a topic that was of interest to them. The experimental curriculum evaluated in the intervention contributed to reading gains while stimulating and sustaining learners’ interest, motivation, and enthusiasm.

Sustaining outcomes

Providing learners with ongoing support and access to services can improve sustained outcomes. A number of researchers report that the beneficial impacts of interventions were not sustained in the long term, and yet there were few suggestions as to how this problem might be addressed. This is a highly relevant question, since disadvantaged learners will most likely continue to face barriers beyond the programme lifetime; this leads authors to raise the question of extending the length of time support interventions are available.[footnote 127]

Measuring outcomes

When measuring outcomes of basic skills interventions, those delivering the programmes need to consider what outcome measures would most effectively indicate success. Studies note that for learners the impacts of the interventions go more broadly than skills attainment alone, for example self-awareness, self-esteem and mental health.[footnote 128] Research using a Community-based English language intervention was designed to improve functional English provision for individuals with an ESOL need.[footnote 129] Analysis of the social integration outcomes indicated that the intervention led to improvements in social interaction and bond forming. There was also evidence of increased confidence in independently going shopping and engaging with health professionals. The research results indicate that Community-Based English Language courses increase English language ability and encourage wider social integration.

6. Conclusions

In line with what is highlighted in existing literature reviews, a key finding from this review is the overall scarcity of evidence on what works to improve attainment among disadvantaged students in FE and adult learning in the UK. This finding strengthens the case for investment in research which tests interventions to build our knowledge of how best to support disadvantaged groups achieve outcomes (as set out in the policy paper that accompanies this report). Future research should explore the entire learner journey to build our understanding of what works to improve outcomes in the FE sector, from participation to related longer-term socio-economic outcomes.

The studies in this review explore the impact of interventions designed to support disadvantaged students. However, very few explore the effectiveness of an intervention for specific groups of adults. For example, the review found very few studies exploring what works to support ESOL learners, lone parents, prisoners or NEET young people and did not find any studies which targeted BAME learners, young adult carers, care leavers or learners with LDD. There is also a scarcity of evidence on the cost-effectiveness of programmes. To improve understanding of how best to support specific groups of disadvantaged adults, further research is needed that explores what works for whom.

6.1 Recommendations

Government should invest £20 million over 5 years to establish a What Works Centre for FE. The policy brief that accompanies this review provides more detailed information on this investment and priorities needed.[footnote 130]

Government and the Centre should focus on what works across all stages of the learner journey, from participation to longer-term socio-economic outcomes. This will require investment in long-term evaluations that track outcomes over several years.

Government and the Centre should also focus on what works for specific groups of learners. Disadvantaged groups, such as care leavers and adults with ESOL needs, face specific barriers to learning. Yet there is limited evidence on what works for whom.

7. Annex 1: The evidence

7.1 Study 1

Department for Education, Improving engagement and attainment in maths and English courses: insights from behavioural research, 2018, accessed 24 September 2019

Department for Business, Innovation and Skills funded the creation of the Behavioural Research Centre for Adult Skills and Knowledge (ASK). ASK aimed to use behavioural science to examine different ways of supporting learners, with Level 1 and Level 2 English and maths, to improve their skills in these subjects.

Interventions were aimed at addressing dispositional barriers – for example, learners’ beliefs, attitudes, perceptions of learning, and changing behaviours towards learning.