Improving GCSE and A level standard setting: a world of learning

A synopsis of the findings of the book: Examination standards: how measures & meanings differ around the world

Documents

Details

Introduction to the Standard Setting Project

The book ‘Examination standards: how measures & meanings differ around the world’ is the culmination of a collaborative project on international standard setting between Ofqual, the Oxford University Centre for Educational Assessment, the Assessment and Qualifications Alliance (AQA), and the UCL Institute of Education. Ofqual’s support for the project stems from its focus on the maintenance of standards in GCSEs and A levels. It is important that we evaluate the systems used to set and maintain standards in these crucial examinations and make them as robust as possible. To do that most effectively we should understand what others do to set and maintain standards in similar examinations, and so what alternative methods could be open for us to use.

The project was needed because there was a lack of accessible documentation on standard setting systems used in different jurisdictions at a level of detail that permits interpretation of a system in terms of the information it uses, the emphasis given to various evidence sources, the underlying definition of standards and any controversies that have arisen. The book documents the diversity of approaches taken to standards in different jurisdictions internationally and so provides access to a breadth of information which was previously unavailable.

The focus of the project was national, curriculum-related examination systems used for school-leaving or university entrance purposes. The project set out to describe the processes used to set standards in these examinations and to explore the concepts relating to standards behind them. The project uses the term standard setting to cover both setting standards for the first time and maintaining them over time; it means any process by which raw examination marks are converted into a reported outcome such as grades.

The project held a symposium in Oxford in 2017. This symposium included contributions from 12 jurisdictions across the developed and developing world. The book highlights case studies from 9 of them and, in its thematic chapters, illuminates similarities and differences in operational approaches to standard setting and in the way that standards are conceptualised.

Many jurisdictions, including England, use curriculum-related examinations to select learners for higher education courses and for employment positions. Some jurisdictions also use examination results as a way to judge the performance of their schools.These are important examinations. Most of their standard setting processes use both statistics and examiner judgement but exactly how different sources of information are used in the decisions that determine which students receive which grades is often unclear to outsiders. This is an interesting area because globalisation has begun to impinge on examination systems but examination standards are still largely a bastion of the local. The book aims to describe in some detail the processes by which different examination systems set standards, making much of this information publicly available for the first time.

In England, the meaning of examination standards has been much debated in academic literature but stakeholders can discuss examination standards using contradictory definitions without realising they are doing so. More transparency in the field would help and one purpose of this book is to contribute to improved clarity. This short report from Ofqual considers how some of the findings from the book might contribute to improving standard setting processes in this country’s GCSE and A level examinations.

Are standards in England rising or falling?

In England, much of the focus on GCSE and A level standards some years ago was because of concerns about whether the increase over time in the proportion of top grades awarded was caused by grade inflation; increases which do not reflect a genuine increase in the attainment of cohorts of students. If there is grade inflation, that raises questions about the efficacy of the system used to set standards in these examinations.

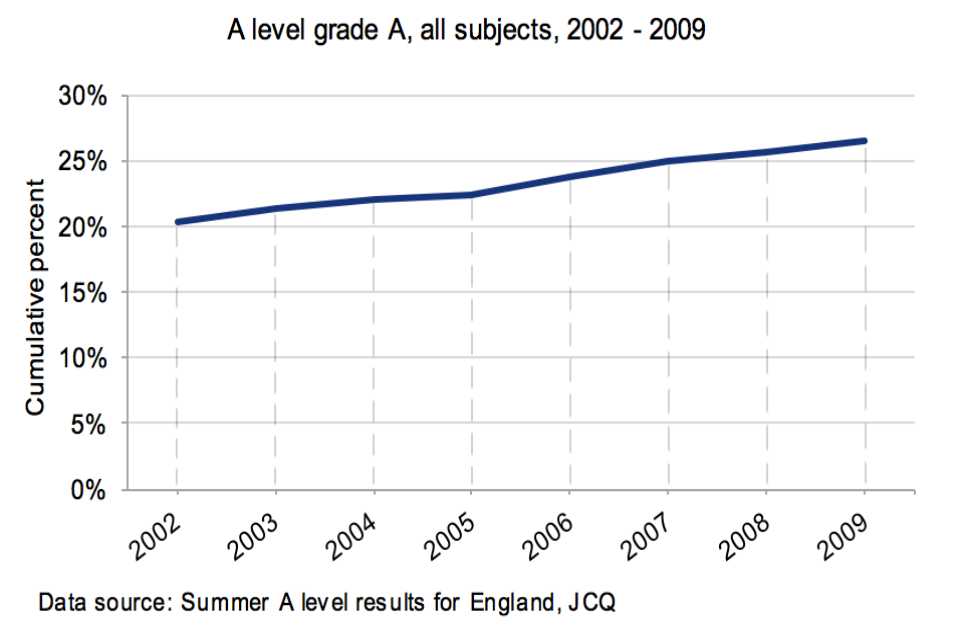

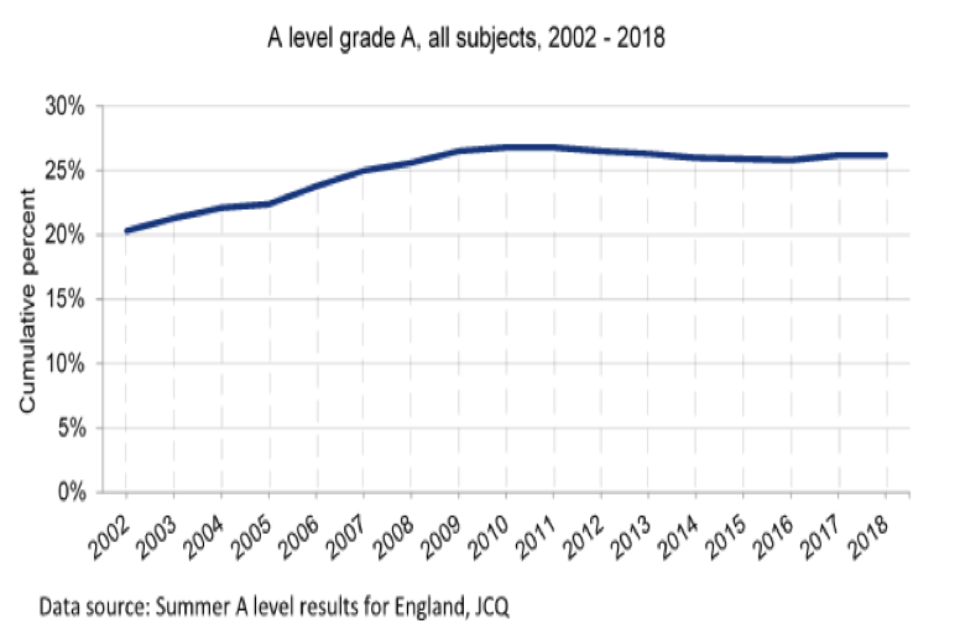

A level grades

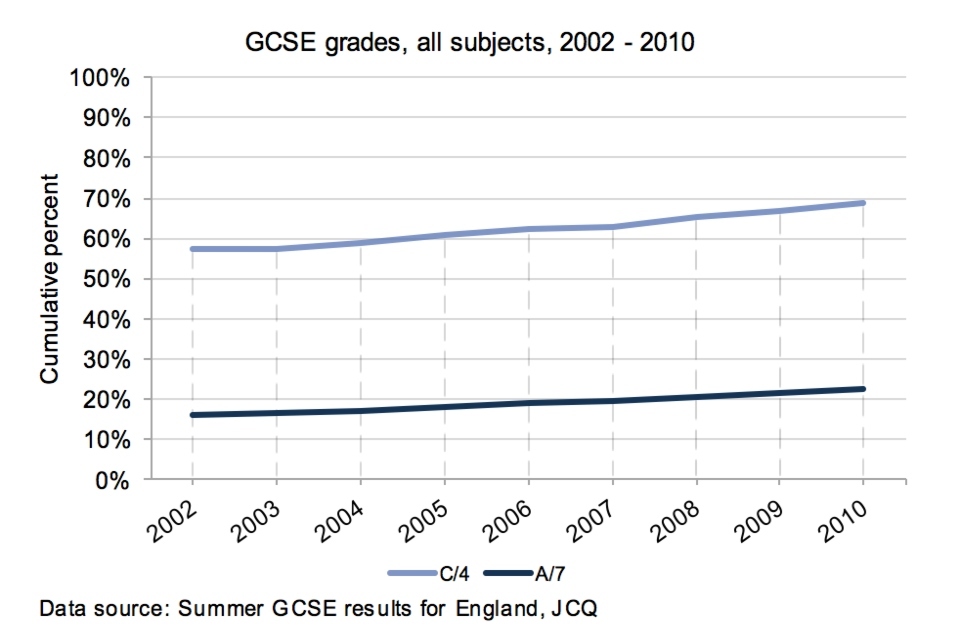

GCSE grades

Why should there have been this steady increase? To what extent did we see in schools and colleges increasingly effective teaching and learning, and better motivated and harder working students who deserved higher grades? Did the improving presentation of examination papers and better understanding of the expectations of examiners contribute to higher grades being awarded? Did changes in the balance of elements that constitute a subject affect outcomes? Did the way that GCSE and A level awarding (standard setting) meetings operated (where the influence of the few candidates whose work is scrutinised in the meeting can contribute to a tendency to give the ‘benefit of the doubt’ to all candidates) play a part?

It was hard to find objective evidence with which to prove or disprove the notion of grade inflation. Certainly, many doubted that any improvements in genuine attainment brought about by better teaching and learning could fully explain changes that doubled the proportion of A grades in both GCSE and A level in the 20 years from around 1990. The published qualitative reviews of standards, started by the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority (QCA) and continued by Ofqual in its early years, which investigated standards over time mostly provided reassuring messages about maintenance. They appeared at odds, though, with much-quoted statistical data from Durham University which showed that, as the years passed, students of a particular ability were gaining better and better A level grades.

The A level A* grade was introduced in 2010 because of a concern that A level grades were no longer distinguishing sufficiently between the top students when it came to university entrance. That was a sign that by having more candidates achieving the highest grade, the A level system was not fulfilling one of its purposes.

Certainly, when examination results were released each August at that time, the stories in the press about the maintenance of standards were typically negative.

Press headlines

Press headlines

That climate led to the creation of Ofqual:

And let’s also put behind us once and for all the old and sterile debate about dumbing-down. I want to end young people being told that the GCSE or A level grades they are proud of aren’t worth what they used to be. I want parents, universities, employers and young people themselves to be confident that exam standards are being maintained.

So today I am announcing that we will split the curriculum-setting and standards-monitoring roles of the QCA, and we will legislate to create a new regulator of exam standards, independent of government.

Ed Balls, Secretary of State for Children, Schools and Families, 27 September 2007

Grade inflation is a focus for Ofqual as it has a statutory objective about standards maintenance. It has another objective to promote public confidence in regulated qualifications and assessments. Achievement of those objectives is threatened if the public believes that a rise in examination results from year to year is not warranted – if there is grade inflation.

Ofqual became fully operational in 2010. One of its top initial objectives was setting standards in new syllabuses as they came to be examined for the first time: new AS in summer 2009, new A levels in summer 2010 and new GCSEs in summer 2011. To help achieve that objective, Ofqual and the examination boards used the ‘comparable outcomes’ approach when the qualifications were awarded. This approach is based on the following principles:

-

that a similar cohort of candidates will achieve a similar profile of results and

-

all other things being equal, that a candidate of a certain level of attainment should achieve the same result, regardless of year of entry or which examination board they took.

The way this approach works in practice is briefly described in the section below on standard setting methods.

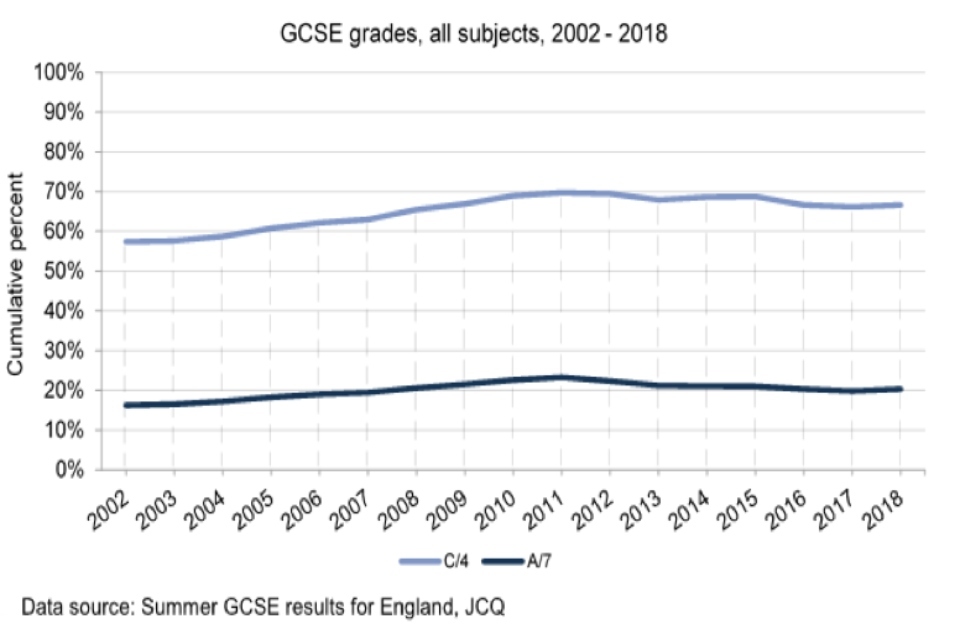

Since GCSE and A level awarding has been based on comparable outcomes, it has helped to keep aligned grade standards between examination boards and there has been little change from year to year in the overall proportions of candidates achieving the higher grades.

GCSE grades

A level grades

That said, this is an area of significant public interest and it is understandable that schools and governments would want to see results rise over time, as an indication of improved teaching and learning, and so that stated policy goals are achieved.

One source of measurement will be the new, annual National Reference Test (NRT). It aims to help maintain grade standards, in a performance sense, in GCSEs in English language and mathematics in England. The purpose of the NRT is to provide Ofqual and the examination boards with credible, persuasive evidence that will allow them to justify a change (or no change) from one year to another in the proportion of 16-year-olds getting a particular grade in their GCSEs. The NRT was piloted in 2016 and has had two full sessions since. Information from the test will not be used by exam boards during awarding until at least 2019. From 2020, we expect to be able to use NRT results each year when GCSEs are awarded.

Are standards in other countries rising or falling?

Across the case studies in the project, there were different opinions about what standards are and some jurisdictions were concerned about whether standards are rising or falling. Questioning the effectiveness of a national examination directly challenges whether or not the ‘right’ standard is being set for university entrants. In many cases, high pass rates have caused political and media scrutiny. This, in turn, has led people to question the system that has produced these results. When a lack of trust in the examinations process takes hold in a system, stakeholders such as students, parents and teachers can lobby for changes or simply become cynical. However, the project also found that despite questioning and doubt, most standard setting systems have remained relatively stable, with some tinkering around the edges, rather than instituting deep-seated change.

While the situation in England seems relatively stable at present, other countries seem to have more serious issues about standards with which to deal. Two examples are described below.

In France, around 80% of 18 year olds sit some form of the baccalauréat, the pass rate is around 90% and there seems to be less questioning of the examinations’ standards and of the standard setting processes than elsewhere. This may be rooted in the fact that the national examination and university entrance system masks a separate, more elitist system, found in the grandes écoles. Students wanting to attend the grandes écoles are chosen after two years of highly competitive preparatory courses; admission does not rely on baccalauréat outcomes although applicants are asked to obtain one. Those who pass the baccalauréat are eligible to attend any public university in the subject of their choosing, but not to enter the elite further training courses. However, students’ failure rate in the first two years of higher education is high, which has caused some consternation. The discrimination function that is found in other standard setting for school leaving examinations seems to be far weaker in France than elsewhere. In January 2018 the French government announced reforms to the baccalauréat which address some of the criticisms made.

Georgia is rather different. Here, university entrance examinations have pass marks that are little above what an applicant might receive by guesswork. Universities accept onto their programmes students who are not university ready, in part because universities are dependant for their survival upon students’ tuition fees. School accountability measures do not include student performance. In the face of these challenges, there is little incentive to introduce rigorous and discriminating standard setting procedures or to make the examination system transparent to stakeholders. The university entrance examinations are both valued and trusted by the teaching profession and the public at large, perhaps more a testament to the corrupt system they replaced 10 years ago, than a full vote of confidence in the examinations themselves.

Standard setting methods

In GCSEs and A levels, the basic principle behind the awarding process is to retain from year to year the level of performance at a grade boundary mark. To help achieve this, the examination boards draw on both statistical and judgemental techniques. The key statistic used at the awarding meeting is a prediction based on prior attainment. The prediction maps the relationship between prior attainment and GCSE or A level outcomes for students taking each subject in a reference year. The examination boards use this relationship to predict the outcomes for the current cohort of students based on their prior attainment. If the prior attainment of the current cohort remains similar to that of the previous cohort, then the outcomes would be expected to be similar.

Subject experts scrutinize the students’ examination work (called scripts) around the predicted grade boundary marks, comparing them with the quality of scripts from the same grade from the previous year (called archive scripts), before using their judgement to recommend the grade boundary marks which are then applied to all students. This is what the project describes as a mixed methods design as it uses both quantitative evidence (statistical predictions) and qualitative evidence (expert judgements of students’ work).

Of the 12 case studies in the project, 7 used a mixed method design, 4 used just quantitative data and 1 used only qualitative evidence.

The mixed methods design systems used in the case studies for setting standards each had its own approach; none was the same as GCSE and A level awarding. For example, in Hong Kong’s Diploma of Secondary Education Examination, the performance standards of the 4 core subjects (Chinese language, English language, mathematics, and liberal studies) were set in the first year (2012) using expert judgement. The standards have been maintained in the years since 2013 using various statistical data and reference to candidates’ current and past levels of performance as well as expert judgement. In particular, a monitoring test for the core subjects is carried out each year and a statistical (Rasch) model is used to produce recommendations for boundary marks for the consideration of expert panels. The standard setting process in use aims to ensure that no single factor or subject expert can predominate in the decision making, and the standards can be maintained and held constant without any grade inflation over time. Ofqual studied Hong Kong’s monitoring test when it was developing the first designs for the NRT.

In Ireland’s Leaving Certificate, a student’s mark in a subject determines the grade in a pre-ordained fashion that is fixed over time and across subjects. This poses considerable challenges for maintaining consistency in grading standards over time since it is impossible to guarantee that a particular year’s examination questions will be identical in demand to those used in any other year. To solve this problem, standard setting is embedded within the marking process. If there are indications that marking is producing a grade distribution considered inappropriate in the context of statistics from previous years and the levels of achievement being observed, adjustments to the mark schemes are used to achieve changes in the distribution of the raw marks and hence the grades. So here expert judgement is used as a check rather than as the main control. South Africa’s National Senior Certificate adopts a similar approach to this.

There may be other approaches to improving the quality of judgements used in awarding. For example, the Advanced Placement® Program in the US and most of the tests used in the end-of-school system in Sweden set standards using a modified Angoff method. This approach is widely used internationally but less familiar in England. In its commonest form, this method requires members of a standard setting panel to review all the items that comprise an examination. They then estimate for each item the probability that a borderline student (one on the grade boundary mark)would provide the correct answer. The minimally acceptable score is then the aggregate of the probabilities.

The project classifies Angoff as an atomistic method; one in which judgements about the examinations primarily involve making decisions about how well students might perform on individual items. Awarding is categorised as an aggregate method as it is rather different: the judgements made make major use of the quality of students’ responses or their marks allocated when sitting a whole examination paper. Another atomistic method is the bookmark procedure. Here, items that make up an examination are rearranged into a book with one item on each page. The pages are sequenced so that the items’ empirical difficulty increases through the book. Panel members are then asked to identify the page where a borderline student will have a 0.67 probability of answering the item correctly. The average page number from the panel members’ proposals is then used as the cut score. Variations of this technique are used to set standards in Sweden in the parts of the Swedish and English tests where the students write essays. It was also used to set standards in the first year of England’s new key stage 2 tests in 2016.

Next steps for Ofqual

Ofqual is charged with securing that the standards of the qualifications that it regulates are comparable with those used outside the UK. Examination standards: how measures & meanings differ around the world will help Ofqual consider what lessons it can learn from the way that other standard setting systems operate and from the consequences of policy changes that have been implemented elsewhere.

There are real risks in taking a method from an examination situated in one cultural and historical context and using it elsewhere. It would be possible to import into our GCSEs and A levels a different standard setting system used elsewhere in the world. However, we have seen nothing to suggest that such a move would have benefits that were positive enough to outweigh the large risks involved in managing such a major change given the deep roots that our examinations have in, for example, the secondary school system and university entrance arrangements.

There is much variety in the standard setting methods used internationally for school-leaving or university entrance examinations although the mixed methods design that we operate underpins the systems used in many other jurisdictions. It is clear that our GCSE and A level system is distinctive, with a large research base behind it including work on how we conceptualise standards. Our look at standard setting across the world does lead us to believe that our system is as good as any.

That doesn’t mean improvements can’t be made to GCSE and A level awarding. We are always looking to strengthen our standard setting methods and we publish details as new ideas and decisions are made. Indeed, as stated in our recent Corporate Plan, we are currently undertaking a programme of work to investigate opportunities to further enhance how grade boundaries are set so that examination boards can better identify and safely recognise changes in performance where these occur. We’ll report more on this work in due course.

Authors:

‘Examination standards: how measures & meanings differ around the world’ Baird, J., Isaacs, T., Opposs, D. and Gray, L. (eds) (2018) Examination standards: how measures & meanings differ around the world. London: UCL IOE Press