Independent review of the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) (accessible version)

Updated 21 March 2024

Dr Gillian Fairfield

December 2023

Acknowledgements

The Review team has interviewed many senior IOPC leaders and frontline staff during the Review. The team and I are grateful to all those who gave their valuable time so generously to support us. I would like to thank the Acting Director General Tom Whiting and IOPC Unitary Board members for the openness and integrity with which they engaged with us.

I am also grateful to Home Office colleagues spanning policy development, sponsorship of the IOPC and finance for their input and support.

The Review has been informed by interviews with many key stakeholders and my thanks go to:

- groups representing the perspectives of complainants and victims;

- national policing bodies and groups representing police officers and staff;

- a cross-section of police forces;

- key statutory IOPC partners;

- partners in Wales;

- the IOPC’s equivalents in Scotland and Northern Ireland;

- thought leaders and academics.

I would also like to acknowledge the invaluable input from all members of our Reference Group with whom we have consulted on our core findings and recommendations and who have given considerable time to strengthening this Review.

My special thanks go to the Review team who have supported me unfailingly during the Review:

- Alex Morrell (Deputy Director and Head of Review Team);

- Martin Skeats (Board Secretary, Disclosure and Barring Service) – supporting the governance aspects of the review;

- Sam Chowdhury (Review Head of Finance & Commercial) – supporting the financial aspects of the review; and

- Cynthia Ebo (Programme Manager).

Dr Gillian Fairfield, Lead Independent Reviewer

12 December 2023

Executive Summary

The Home Secretary commissioned this independent review of the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) in February 2023. A summary of the terms of reference was published on 1 March 2023, alongside statements from the relevant Ministers to both Houses of Parliament updating actions to improve police standards and culture. This review assesses the IOPC as it stands at the conclusion of this Review and recommends where improvements are required to lay a stronger foundation for its future.

The context within which the IOPC operates is challenging. This review has been carried out in the context of increasing case complexity, crowded stakeholder landscape, declining public confidence in policing, increasing demand on the police complaints system, a substantial fall in the number of independent IOPC investigations carried out annually, and significant (and growing) financial pressures.

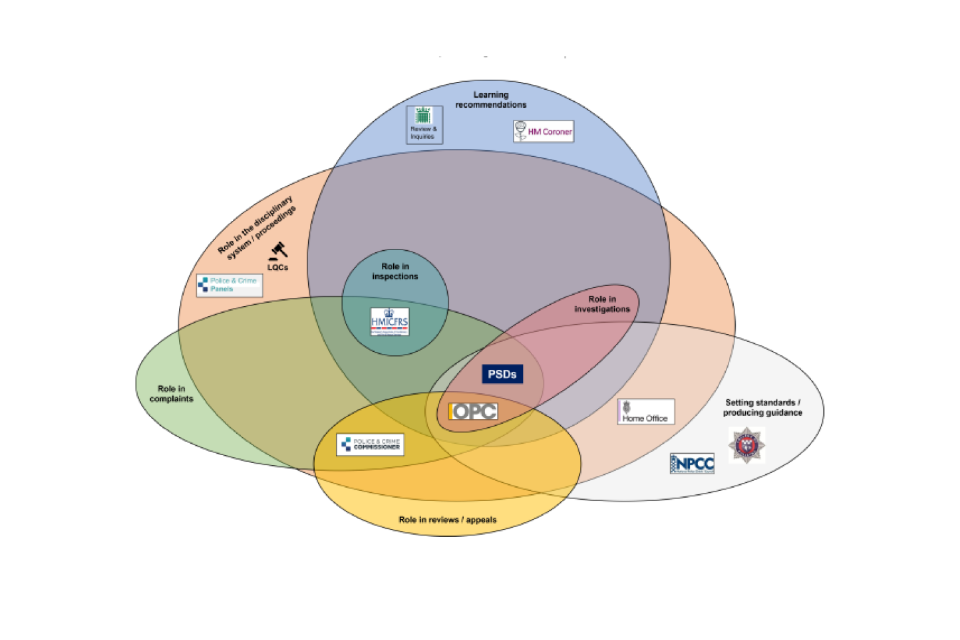

There is a multiplicity of statutory and non-statutory stakeholders with whom the IOPC interacts. Even amongst those working closely within the system, many do not fully understand how everything fits together or fully understand the IOPC’s role and remit.

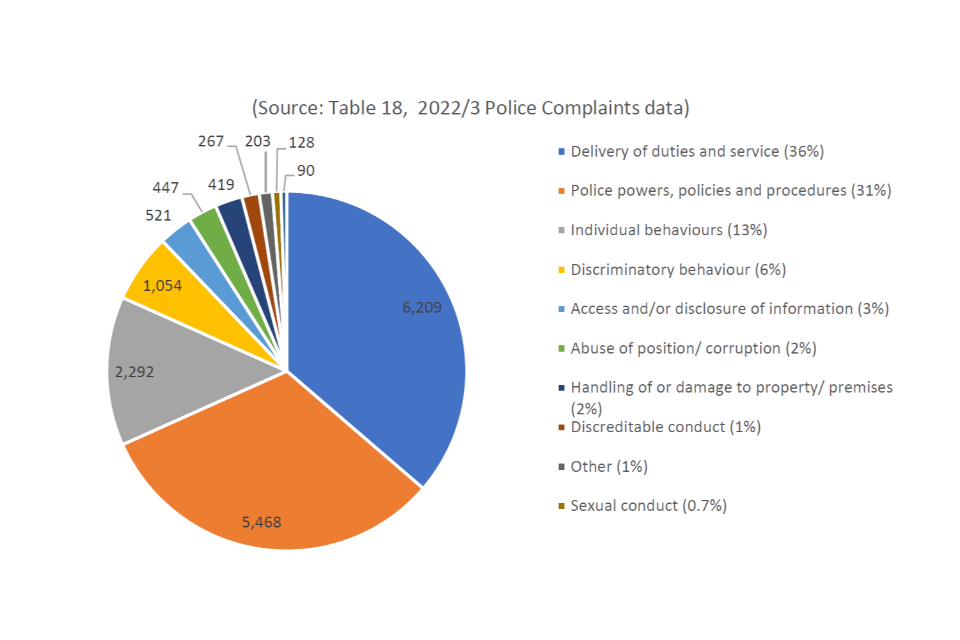

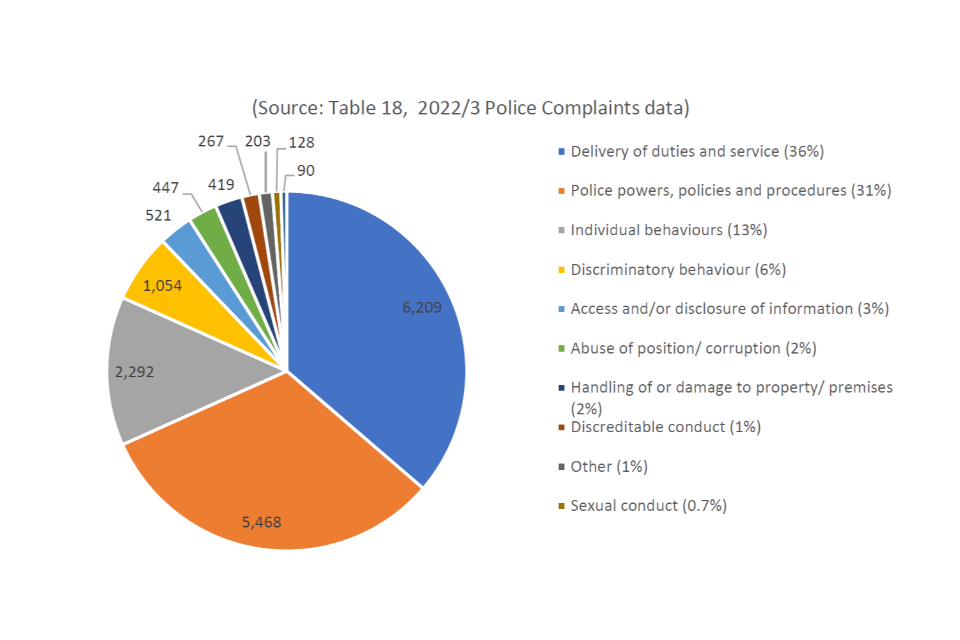

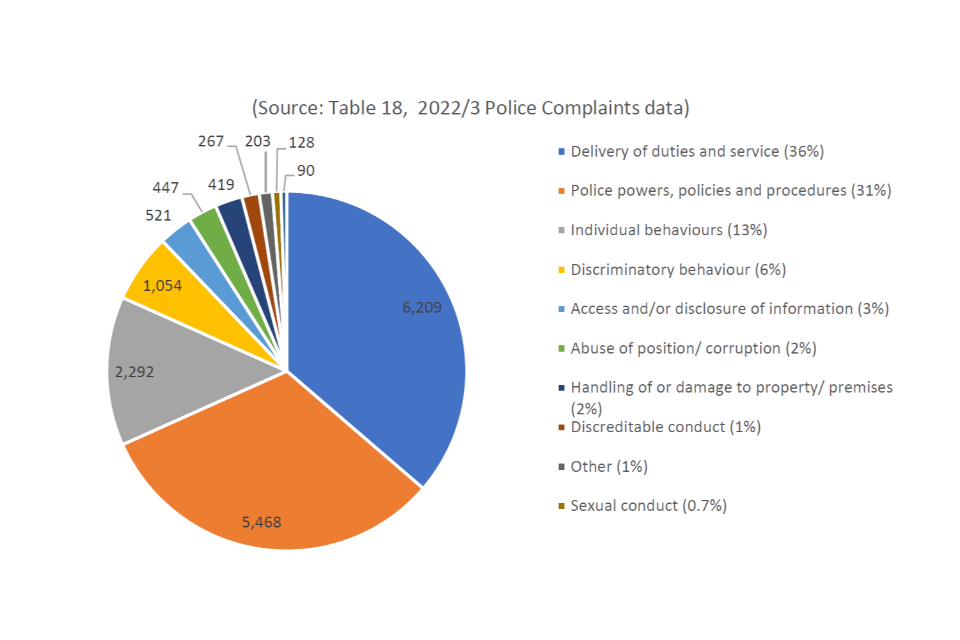

Following a number of high-profile police incidents and investigations over recent years, public confidence in policing has fallen sharply. Since the IOPC was established in 2018, the overall number of police complaints has risen significantly, with complaints made against 1 in 5 of the police in 2022/23[footnote 1].

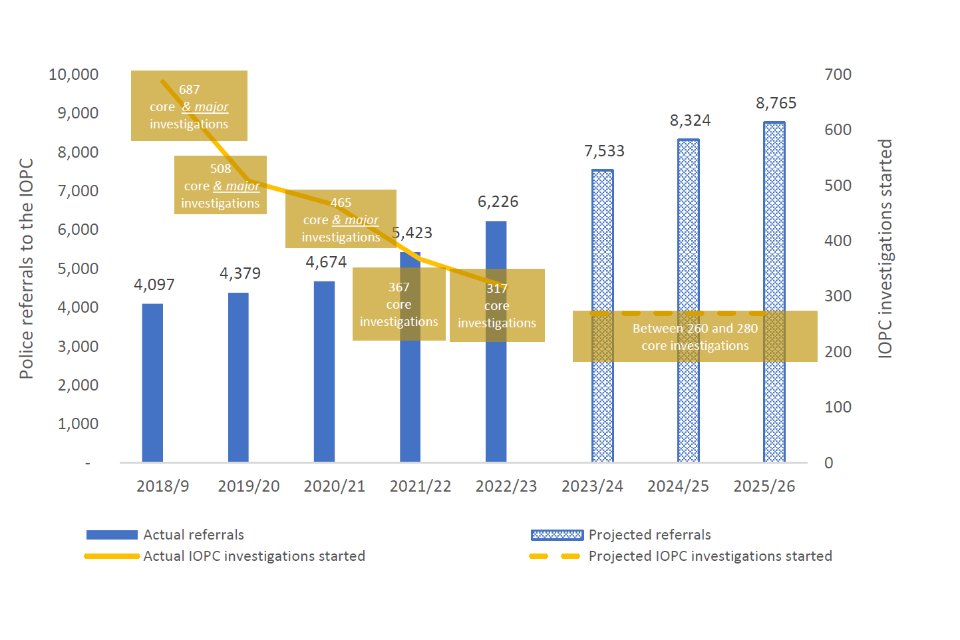

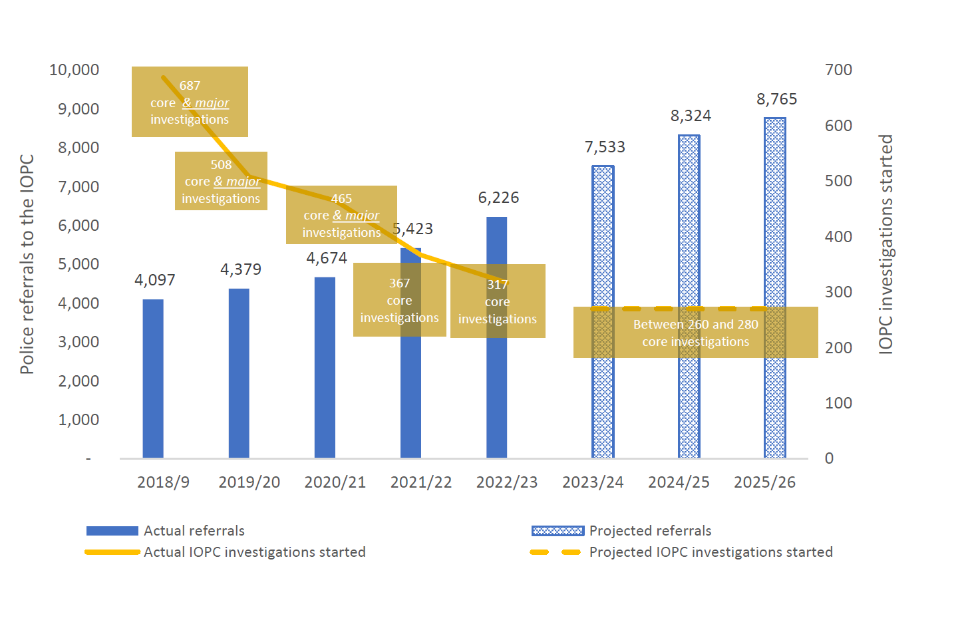

On current IOPC projections, referrals that the police and others send the IOPC will have grown 113% since the IOPC was established in 2018/19, in sharp contrast to a 61% fall in the number of independent IOPC investigations it launches annually (between 260 and 280 this year) over the same time.

Notwithstanding the reasons behind the IOPC conducting far fewer independent investigations than it used to (and there are many), one crucial impact of this is that, as referrals continue to rise, the IOPC is investigating a smaller and smaller proportion of complaints, conduct and deaths and serious injuries (DSI) referred to it. In 2018/19, it investigated 1 in 6 referrals it received. This year (2023/24) it will investigate 1 in 28 and this will fall further to 1 in 32 by 2025/26. This could decrease public confidence in the system.

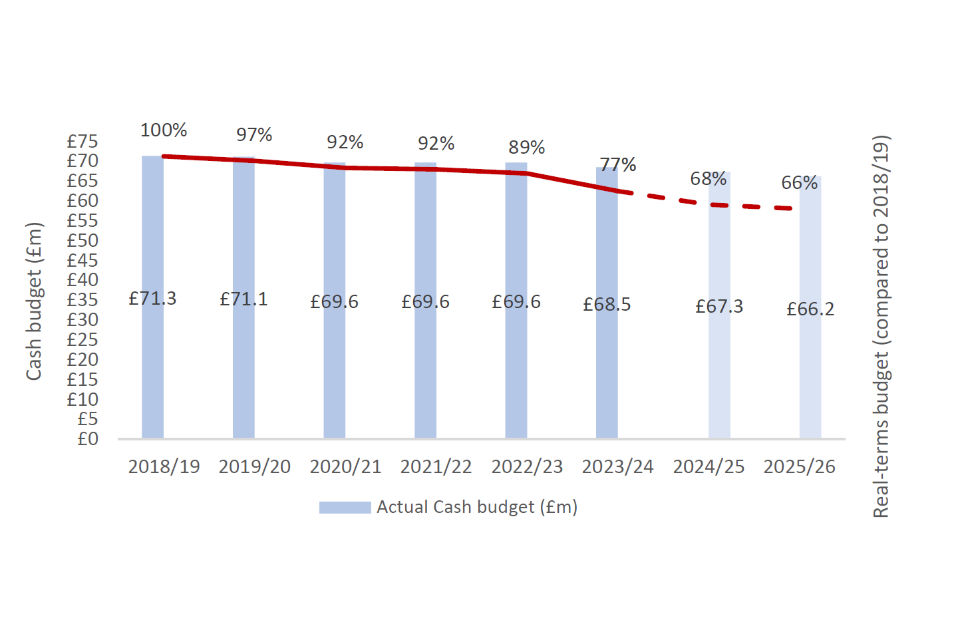

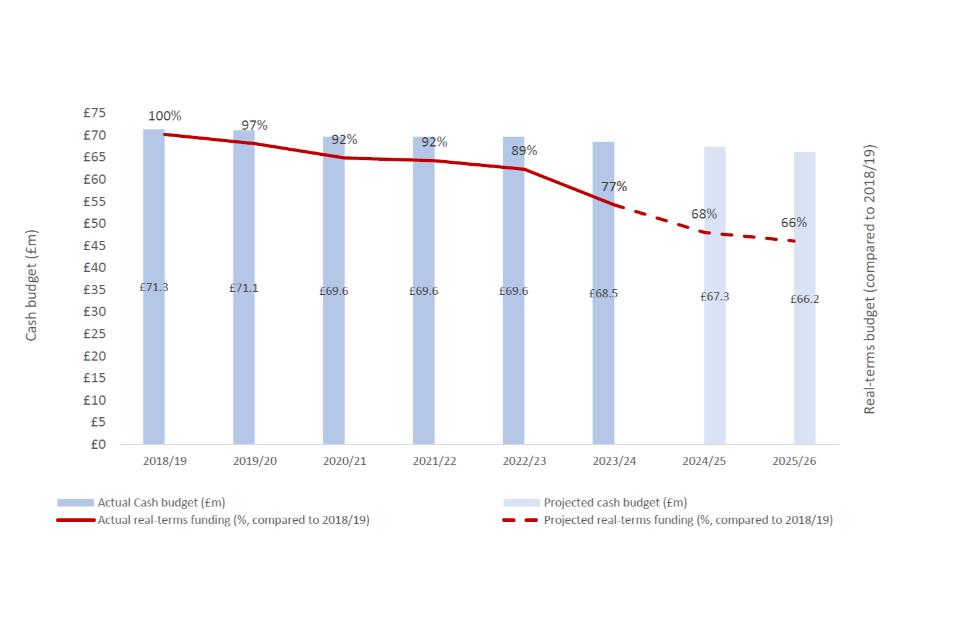

The IOPC also faces significant financial pressures. The Home Office set out an expectation, in this Review, that the IOPC’s cash budget falls a further 5% between 2022/23 and 2025/26. On current forecasts, this would mean the IOPC would see a 34% real-terms cut to its budget over 7 years, when its work has never been more vital.

Police have immense power and play a key role in upholding the law, maintaining order and keeping people safe. It is imperative the public has confidence that police use their powers fairly, appropriately and responsibly. This is vital to maintain ‘policing by consent’. The IOPC is an essential part of the complex system holding the police to account.

The IOPC is a relatively new organisation and stakeholders recognise the IOPC has made progress over the last 5 years, but told us it has much still to do.

Since the departure of its inaugural Director-General (DG) in December 2022, the IOPC has been in a state of flux, but the issues we found are longstanding and do not stem from this departure. The Acting DG, his team and the Board should be commended for stabilising the organisation following the previous DG’s unforeseen resignation. We have been impressed by the many highly committed, professional and dedicated members of IOPC staff we met. However, we find IOPC staff often perform admirably despite, rather than because of, the systems and structures that should support them.

There are significant issues that must be addressed to: put the organisation on a sustainable footing; ensure it effectively delivers its remit; speed up its investigation processes; improve transparency; and, ultimately, improve public confidence in policing. This executive summary cannot do justice to the detailed findings and commentary within the body of the report. Accordingly, it should not be read in isolation, but alongside our full report. We make 93 recommendations about the IOPC’s effectiveness, governance, accountability and efficiency.

A substantial amount of this Review has focused on the IOPC’s reviews, investigations and assessment of referrals. The legislation underpinning this work is extremely complex and confusing for even the most well-informed reader. We make no apology for providing detailed explanation and background in this report and annexes on the legislative framework the IOPC operates in and how it interacts with others. We consider this critical to facilitating a better understanding of our findings and recommendations.

Effectiveness of IOPC reviews

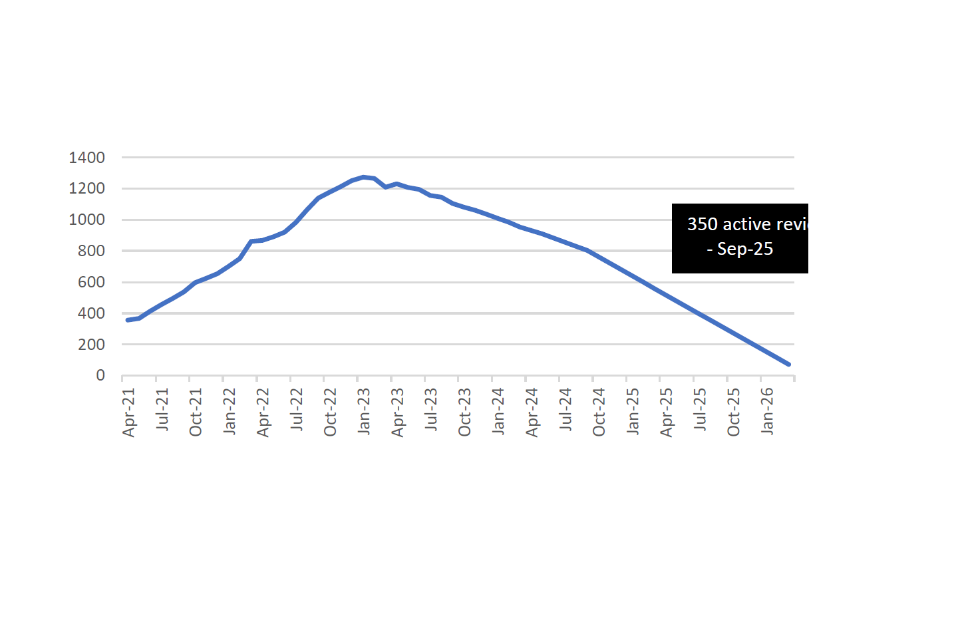

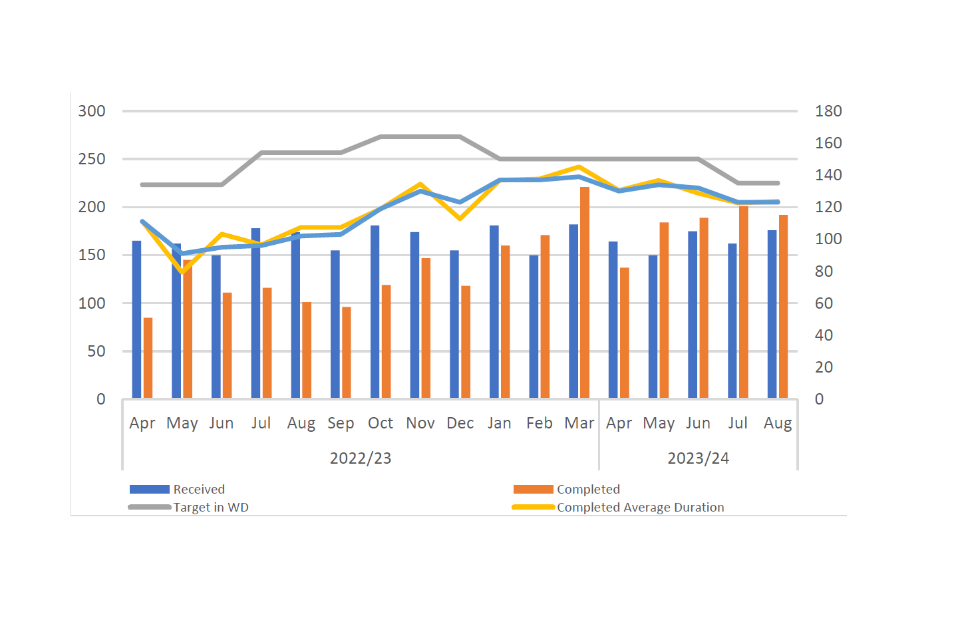

The IOPC conducts around 3,000 reviews annually of whether complaints and deaths and serious injuries from police contact have been handled ‘reasonably and proportionately’. Following reforms in 2020, which replaced a system of ‘appeals’ with a system of ‘reviews’, the number of applications it received for reviews of complaint handling grew substantially. The IOPC has put concrete measures in place to tackle this, but a significant backlog developed and remains.

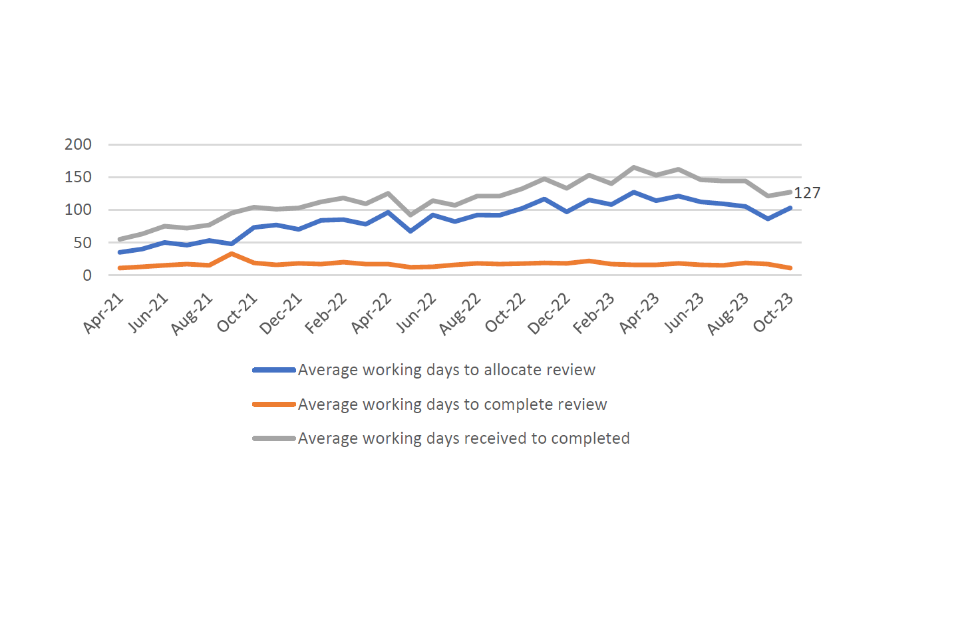

As of October 2023, the IOPC was taking 24 weeks on average to complete reviews from receipt of the relevant papers. On its current trajectory, it will not reach previous turnaround times (10 weeks) until September 2025. This is unacceptable. We recommend the IOPC maintains the additional, temporary workforce it has recruited with prioritised funding for this until service levels return to previous levels.

Effectiveness of IOPC assessment of referrals

With the IOPC independently investigating a far smaller proportion of cases referred to it, how it decides which it will investigate is ever more critical. It currently considers: the seriousness of a case; whether it potentially undermines public legitimacy of the police; where an independent investigation adds greatest value; and whether the case falls within one its themes (currently: discrimination; and violence against women and girls). However, interviews with IOPC stakeholders and groups representing complainants and victims, highlighted a uniformly poor understanding of this use of themes, and how the IOPC selects them.

We share the widespread concerns raised with us – from police forces, groups representing complainants and stakeholders – that the IOPC’s weighting of cases that fit certain themes may mean it reacts to issues in the public eye currently, at the expense of emerging issues it might therefore miss. We also found the IOPC does not currently have the requisite buy-in to justify its continued use of themes to weight decisions on which cases it investigates. So, we recommend the IOPC discontinues its consideration of themes in the assessment of referrals.

The IOPC currently has no insight into the outcome of individual conduct cases referred that it sends back to local police forces to consider. It reviews all Death and Serious Injury (DSI) cases investigated by local police and will see cases where complainants apply for a review of their case (where the IOPC is the relevant review body). But it does not see individual outcomes of conduct cases considered by local polices, including those where the IOPC had reviewed a referral and decided to send this back to forces. This means both that it has no feedback from which it can evaluate these referral decisions and that there are inadequate checks on the effectiveness of handling of conduct matters. We recommend the Home Office and IOPC consider how this gap could be addressed, through legislation if necessary.

Effectiveness of IOPC investigations

Despite improvements, core IOPC investigations still take too long (9 months on average; with 15% taking over a year, according to the latest 12 month rolling figures). The impact this has on complainants and bereaved families, and police officers and staff under investigation cannot be overstated.

We make multiple recommendations on timeliness and quality, for example: introducing specialised investigation teams (e.g. fatal use of force team, that could look at firearms, taser, and physical restraint cases); introducing dedicated functional teams; speaking to complainants early to understand what they want from the investigation; having clearer and narrower investigation terms of reference; establishing primary findings of fact much earlier in the process; establishing the best way to establish facts rather than following overlong processes; removing blocks in the system involving multiple stakeholders.

The IOPC should review its communications strategy during investigations – with the public, complainants, police and stakeholders – with a view to being as transparent (and consistent) as possible about the progress of its investigations and communicating to the public earlier (without prejudicing their outcome and potential misconduct proceedings or criminal cases).

A great many issues can cause investigation delays; some of these are outside of the IOPC’s control. We recommend the Government brings together the Home Office, Ministry of Justice, IOPC, CPS, Office of the Chief Coroner, police and HSE to map key processes and identify pinch points in police, IOPC, CPS and coronial activities. This group should ensure and encourage proportionality at each stage (particularly in IOPC investigations and whether appropriate use is being made of existing accelerated procedures) and options to hasten the conclusion of all such proceedings, including, as appropriate, legislative reform and time periods set out in law.

Many stakeholders and staff told us that the IOPC should be more forthright and bolder in defending its role in ensuring police accountability, its work and processes when it is justified in doing so.

Overarching considerations for reviews, referrals and investigations

Whilst feedback from groups representing complainants and victims, police forces and staffing associations and other stakeholders acknowledged that many reviews and investigations are of high quality, we also heard from some stakeholders that consistency of quality is a problem and thus recommend several key actions to oversee and improve quality in the body of our report. For example, the IOPC should: introduce an annual quality report alongside its Annual Report and Accounts; review its quality assurance framework; and review the consistency of the quality of its decision-making, evidence and investigation report clarity, through frequent dip- sampling of cases, and publish a summary of the findings of these assessments.

Many stakeholders told us there were material inconsistencies in the calibre of IOPC investigators with gaps or inconsistencies in training, particularly around police procedures (e.g. Police and Crime Evidence Act 1984) and understanding the police environment. We recommend senior operational leaders within the IOPC consider how to improve training, in particular to ensure: familiarity with trauma- informed practice; stronger appreciation of policing environments (including through training alongside police forces, where appropriate) and understanding of police powers. Alongside this, we recommend the IOPC reviews the extent of training and looks for opportunities to accredit analysts who assess referrals and casework managers who conduct reviews.

The ability to challenge IOPC decisions is limited; the main recourse is Judicial Review. We recommend the Home Office and IOPC consider options to make challenges to IOPC decisions more accessible, for example by capping the financial liability someone might incur from covering IOPC’s legal costs if they applied unsuccessfully for Judicial Review of an IOPC decision or investigation. If such a cap is rejected, an equally effective alternative should be introduced.

Further work is required to consider how ‘near miss’ cases may be handled to ensure learning is encouraged and individuals held accountable where a death or serious injury during or following police contact is only narrowed averted.

Wider effectiveness of the IOPC

The legislative framework under which the IOPC operates is complex and has been amended many times. In general, we found that the IOPC has the correct broad functions, with two notable exceptions. First, the IOPC is not empowered through legislation to follow up on its many recommendations, which leaves a real gap in the current system. Second, where its assessment unit decides a local police force should investigate a case that had been referred to the IOPC, it has no visibility of the outcome of conduct cases and therefore cannot learn lessons from how it determines its mode of investigation decisions. The Home Office, with the IOPC, should consider whether and how both gaps should be addressed.

We found fundamental misunderstandings of the IOPC’s core purpose and role among some of its key stakeholders and groups representing complainants, and meaningful differences in how staff, the Home Office and stakeholders describe these.

The IOPC’s Board should clarify its core purpose and how to further communicate and build understanding of this internally, among key stakeholders and the public.

In particular, the IOPC should discuss with the Home Office and clarify the degree to which it balances its limited resources and attention between:

- securing the right outcomes and ensuring all appropriate learning and improvements are made from individual investigations and reviews; and

- wider ‘thematic reviews’ that look at many complaints and investigations to identify broader learning and improvements to police complaint handling and wider policing practice.

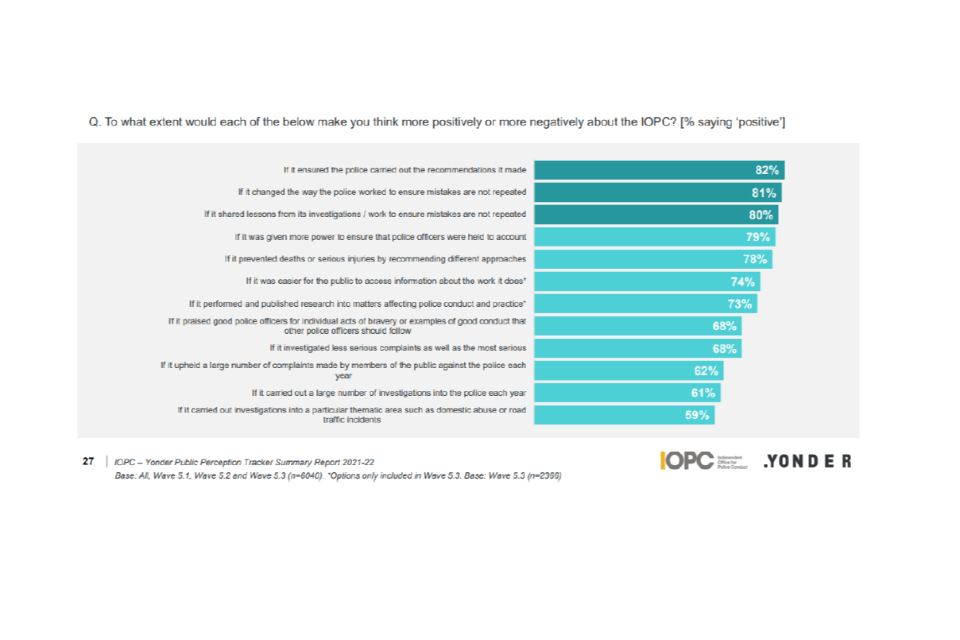

Whilst 2/3 of people have heard of the IOPC, 74% do not know enough about it to say anything about what it actually does. Only 1/3 of survey respondents (over 2022/23) consider the IOPC is doing a good job. We recommend the IOPC survey public attitudes about it conducting significantly fewer independent investigations.

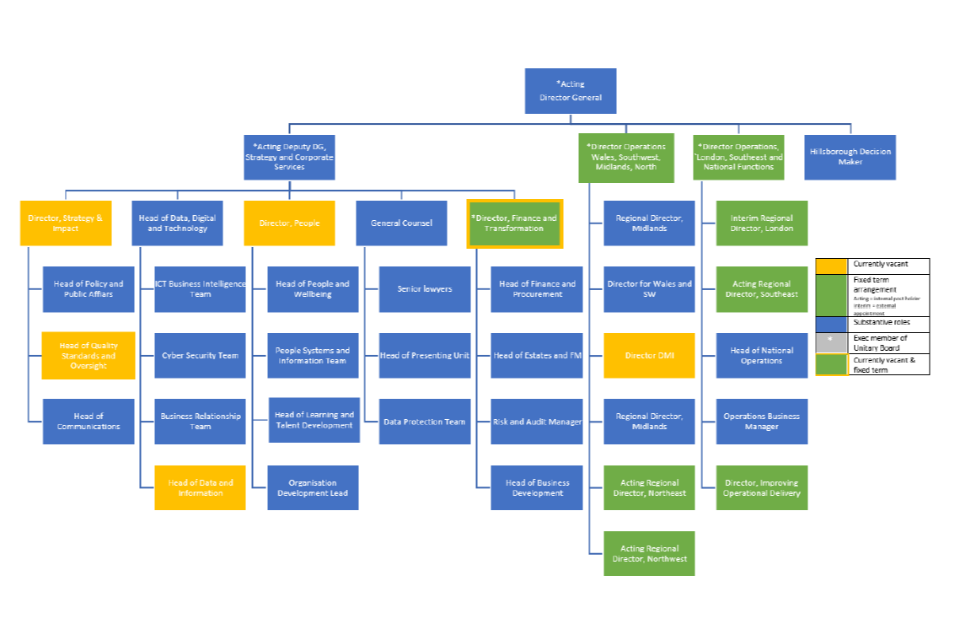

In assessing the effectiveness of the IOPC operating model to deliver its key functions we consider the corporate organisational design to be suboptimal. IOPC regions operate in silos, with material differences in how it conducts investigations and limited best practice sharing. Excellent practice in one region is often not adopted in others. We recommend the IOPC considers what can best be done nationally across its operations while still preserving a regional outreach function to maintain regional relationships. Given the volume and profile of IOPC engagement with the Metropolitan Police Service, the IOPC must consider their place in this model.

The IOPC needs to develop a workforce strategy in tandem with a revised estates strategy, future operating model and revised financial plan. It should also establish an integrated performance report, bringing together operational, financial and quality performance measures.

Governance

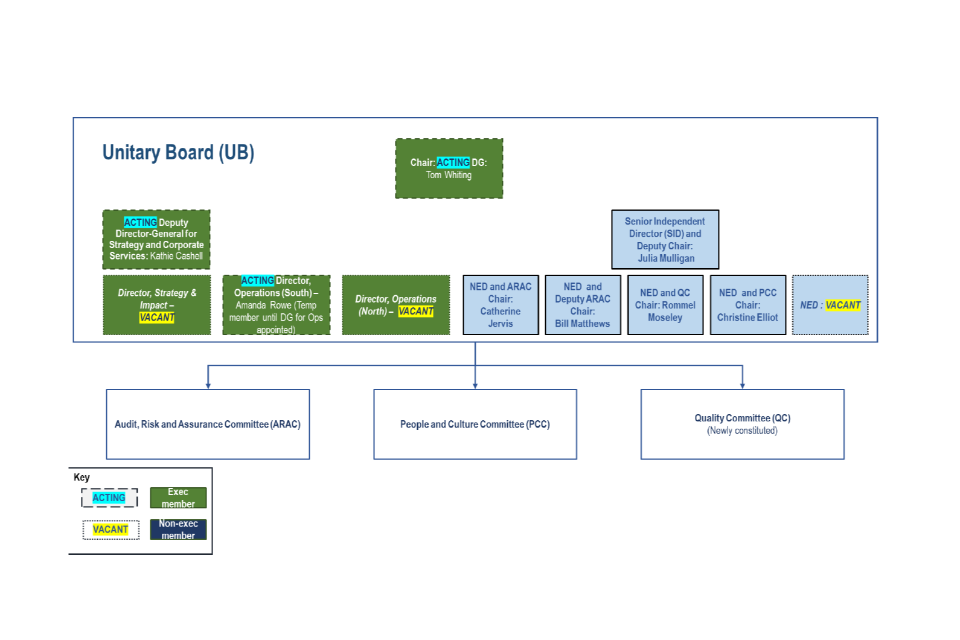

We have found some but not all of what we would expect to find in a well governed public body. However, we believe that the governance of the organisation and in particular the ability of the Board to hold executives to account must be strengthened.

While too many are temporary appointments, all Board members are committed and engaged. However, oversight of IOPC finances; engagement with staff; strategic planning and performance management must be improved. Most importantly we found that the current approach to independence is inhibiting both board and Home Office ‘holding to account’. Independence and accountability should not be mutually exclusive but are often treated as if they are.

It is essential that for the IOPC to fulfil the purpose for which it is established both IOPC and Home Office can demonstrate that decisions such as those about policing have been made independently from political consideration. At the same time, Ministers must be able, directly or through their officials, to hold the IOPC to account for their performance and consequently give account to Parliament.

We have recommended that Home Office and IOPC should agree a new framework document which sets out the broad principles of how the IOPC’s independence in respect to decision making will be protected while allowing the IOPC to be held to account. The need for a shared understanding goes beyond the IOPC and Home Office. We encourage the IOPC and Home Office to create a debate with interested stakeholders to inform the framework content.

Currently, all operational powers are vested in the DG, who then delegates them. This approach was put in place when the IOPC was constituted and is not working as it should. The vital checks and balances for good governance are missing. It is now time to strengthen governance to facilitate stronger accountability. We have been steered by the principle that no one individual should have unchallenged decision- making powers.

We recommend that governance arrangements are changed as follows:

- the Crown appoints, following Home Affairs Select Committee (HASC) scrutiny, an independent Non-Executive Chair to lead the IOPC;

- Ministers appoint other Non-Executive Directors (NEDs)

- NEDs appoint a Chief Executive (who would customarily be the IOPC’s Accounting Officer) and other executive directors to the Board

- All functions of the IOPC are vested in the body corporate, the legal entity.

For avoidance of all doubt this does not mean a return to the former IPCC commissioner model. NEDS should not, as individuals, have any decision-making authority, other than in respect to how board business is conducted. We set out in the report how we envisage the Board will exercise its responsibilities without, itself taking operational decisions.

These changes are not simply about appointing someone to chair a Board. They are about strengthening the overall model of accountability and support for those charged with the onerous responsibility of making decisions on behalf of IOPC and, by extension, complainants and those complained about.

As the IOPC’s governance is set out in law, these governance reforms will require legislative change. Recognising that legislation may take time to secure, we have carefully considered whether our proposed strengthening of governance could be achieved without recourse to legislation. We have concluded that any alternative is substantially weaker. Nevertheless, we recognise that the Home Office or IOPC may wish to put interim arrangements in place ahead of legislative change taking effect. While we do not propose an interim arrangement, we have set out in the body of the report the principles any such arrangement should strive to meet.

Accountability

This Review considers accountability to the public; victims and complainants; parliament; the Home Office; and wider stakeholders.

We recommend the IOPC should review how to better clearly communicate to the public the complaints and disciplinary system and its role within it. Its website, whilst much improved, must be made still more navigable and clearer on the IOPC’s role. It must be transparent by default. The IOPC should develop and publish on its website a monthly performance report that meaningfully facilitates transparency and external scrutiny. The IOPC should consult the public and stakeholders as part of a review of its publication policy. It should consider publishing investigation reports in full by default and extending how long reports are available on its website in order to facilitate transparency.

All publications should be intelligible to the general public without a detailed understanding of the complex legislative framework it operates within. But the IOPC should also broaden its wider engagement, beyond existing channels and publishing documents and spreadsheets on its website.

We were struck from interviews with groups representing complainants that many feel they face barriers in: making police complaints; asking the IOPC to review how their complaint has been handled; or challenging IOPC decisions or investigations. In particular some bereaved families, complainants and victims struggle to engage with the complexity of the police complaints and disciplinary systems and their interaction with the courts and coroner. The IOPC should provide greater support to those who struggle to make police complaints, apply for reviews or engage with investigations.

To facilitate accountability to Parliament, the IOPC’s annual report must be laid before Parliament and, as it is an arm’s length body of the Home Office, its work and performance is scrutinised by the Home Affairs Select Committee (HASC). Its Annual Reports should set out the challenges, risks and opportunities it faces, and actions it is taking to address them.

Accountability to the Home Office for its use of public money should be strengthened. Further work is required to develop a better working relationship with the Home Office Sponsorship Unit (HOSU). The Home Office should be clear on the differing accountabilities and working relationships between the Home Office Police Integrity Unit and HOSU.

The IOPC works closely with many statutory stakeholders but its Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) are almost all years out of date. It needs to review and update the MOUs it has with key partners to clarify how they interact in this crowded stakeholder landscape.

Funding, spending and financial future

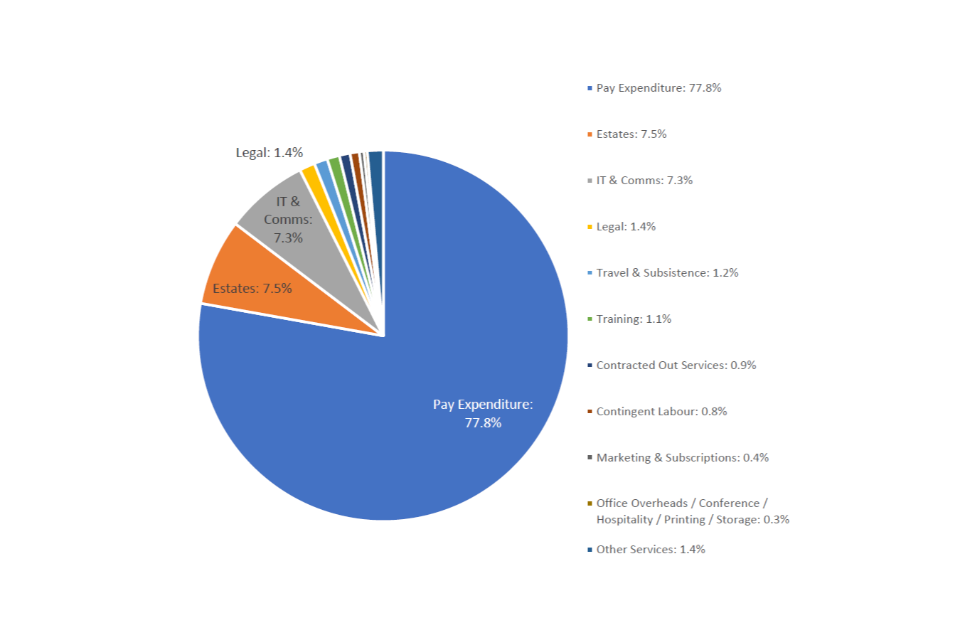

The IOPC’s current funding model is not sustainable. Over the last 5 years, its real-terms budget has been cut by 23%. The Home Office and IOPC need to work together much more closely to inform and constructively challenge the IOPC’s financial plans. We do not have confidence – nor do some key figures in the IOPC – in its medium-term (3-year) financial plan agreed in February 2023. IOPC Finance and Business Development are urgently revising it.

We suggest the IOPC should: develop best- and worst-case scenarios, across a range of factors (including demand, finances) and apply sensitivities, and agree its planning assumptions on pay, inflation and demand with the Home Office; seek much more extensive input and challenge from across the organisation; bring together more clearly pressures and efficiency plans; include a risk of delay in the completion of IOPC’s Hillsborough work; review planned savings to staffing costs, in light of the review’s observations. It must also review its estates strategy and discuss with the Home Office options to enable the IOPC to move to less expensive accommodation.

Financial management

The Home Office must move away from focusing exclusively on the IOPC’s bottom line. It needs to ensure effective governance and challenge for the taxpayer and support the Board in analysing the IOPC’s financial information and whether it delivers value for money for the taxpayer. Scrutiny around this is currently weak. Clarifying what is meant by the IOPC’s ‘independence’ would be helpful in building a better working relationship between both the IOPC and Home Office in terms of financial accountability, transparency and governance. The IOPC should appoint a Finance Director – with singular accountability for the organisation’s financial planning – to the Board without undue delay to provide greater financial leadership. Finance discussions should receive higher priority and more time at Board level. The Board should consider whether it currently has the most effective committee structures to support it.

Concluding comments

We recommend an iterative, evolutionary process of improvements. Whilst some of our recommendations can, and should, be addressed quickly, and others may take longer (a small number would require legislation), all should be pursued at pace.

Disappointingly, some of our findings and recommendations are similar to those from previous reviews and inquiries (e.g. The Home Affairs Select Committee (HASC) HASC Inquiry into Police Conduct and Complaints (2022), Independent Review of Deaths and Serious Incidents in Police Custody (2017). This strongly suggests the IOPC (and others) have failed to adequately act on previous findings and important learning opportunities have been missed. We are left with the impression that recommendations may fall into an abyss. This must not happen again. To ensure it does not, once a permanent IOPC DG is appointed, they should grip implementation of these recommendations.

We recommend the permanent DG provide updates to the HASC as required, from April 2024. Regular scrutiny from this Committee, on implementation of this Review’s recommendations, will help ensure agreed recommendations are adequately acted on and with all due pace.

It is important the IOPC continues to improve. It is a significant organisation that fulfils a vital function. It has already begun this journey of improvement and we hope our report facilitates a different kind of conversation between the IOPC, the Home Office and wider stakeholders, to address the key issues raised. A full Table of Recommendations is contained at the end of this report.

Chapter 1. About this Review

Background

1. The Home Secretary agreed the terms of reference for this independent Review of the IOPC in February 2023. Annex A – Terms of reference for the Review sets out the full terms of reference for this Review. The terms of reference were informed by a self-assessment by the IOPC, as well as Cabinet Office guidance for the wider Public Bodies Review Programme. A summary of these terms of reference was published on 1 March 2023 alongside a statement from the Minister of State for Crime, Policing and Fire updating the House of Commons on actions to improve police standards and culture.

2. We have endeavoured to follow these Terms of Reference closely, to produce a thoughtful, objective, evidence-based review that recognises that the police complaints system has undergone significant evolution over the years. The IOPC is still a relatively young organisation and will continue to evolve as the context in which it operates changes. The goals of this Review were to: assess the IOPC as it stands today; recommend where it (and its sponsoring department, the Home Office) could make further improvements; and base recommendations on sound change principles that lay a stronger foundation for the IOPC’s future.

Areas of focus

3. The IOPC’s remit extends beyond the police, to elected Local Policing Bodies (LPBs)[footnote 2] which comprise: Police and Crime Commissioners (PCCs) and their deputies; the London Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime (MOPAC) and their deputy. Given the wide scope of this Review and the time available, we have focused on the IOPC’s role in relation to police officers and staff in the forty- three territorial police forces in England and Wales, which account for the vast majority of the IOPC’s workload. Nevertheless, many of the Review findings will apply to the IOPC’s work with other groups.

Methodology

4. We have interviewed more than thirty senior IOPC leaders, attended various IOPC Boards, operational groups and sub-committees and met with large groups of staff (including frontline investigators, operations managers and casework managers).

5. As well as holding interviews with IOPC management, investigators and staff we engaged with stakeholders across the sector, including:

- civil servants from the Home Office spanning policy development, sponsorship of the IOPC, finance and ministers’ private offices;

- groups representing the perspectives of complainants and victims (e.g. INQUEST, Office for Victims’ Commissioner, Victim Support);

- national policing bodies (e.g. National Police Chiefs Council) and groups representing police officers and staff (e.g. Police Federation);

- a cross-section of police forces (e.g. Metropolitan Police London and South Yorkshire Police);

- key IOPC partners (e.g. College of Policing, Crown Prosecution Service, His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFRS));

- partners in Wales (Welsh Government and Welsh Chief Officers’ Group);

- equivalents to the IOPC in Scotland[footnote 3] and Northern Ireland[footnote 4]; and

- thought leaders and academics (e.g. Institute for Government).

6. In common with many other reviews within the Public Bodies Review Programme, the time allowed did not provide opportunity for a public call for evidence. However, we received and reviewed a number of written submissions from IOPC stakeholders and members of the public.

7. We have reviewed more than six hundred documents requested from the IOPC about its work. We have extensively reviewed the provision and accessibility of information provided on the IOPC’s recently improved public website. We have also reviewed underpinning legislation and related materials on the police complaints system, including: reports from previous reviews of the IOPC’s predecessors; reviews of related bodies; and the Home Affairs Select Committee inquiry into Police Conduct and Complaints which concluded in 2022.

8. We also sought and benefited from the perspectives provided by: groups representing complainants and victims; charities supporting victims; and groups advocating for victims and police accountability. We are enormously grateful to each for generously sharing their insights which we have drawn from throughout this report.

9. To support the Review and in line with Cabinet Office Guidance, a small Reference Group leaders with relevant knowledge and expertise was established to provide challenge and insight to the Review. The Group met three times and was responsible for discussing and providing views on key issues, emerging findings and many of the recommendations of the Review.

10. Annex B – Methodology of this Review on the Review’s overall methodology has further information on:

- Review team’s engagement with the IOPC (Board meetings observed, senior managers interviewed and groups of staff we have met with);

- individuals interviewed from the Home Office;

- the IOPC’s external stakeholders consulted;

- the groups that represent, support or advocate for complainants and victims consulted;

- written submissions received

- documents requested to inform the Review; and

- the terms of reference for the Reference Group convened to discuss these findings and recommendations.

Format of the Review

11. This report follows the outline of the terms of reference and is divided into sections that cover the main themes of:

- the effectiveness of IOPC reviews;

- the effectiveness of IOPC assessment of referrals;

- the effectiveness of IOPC investigations;

- overarching considerations of reviews, referrals and investigations;

- the IOPC’s wider effectiveness;

- governance;

- accountability;

- the IOPC’s funding, spending and financial future; and

- financial management.

12. It became evident during the Review that, even among close IOPC stakeholders, not all are completely clear on its role, purpose, the parameters under which it operates or indeed how it operates. We have therefore taken the decision to include a longer introductory section to the report in Chapter 2. Introduction and background to help the reader understand the operating and financial context in which the IOPC operates.

Chapter 2. Introduction and background

History of police complaints system

13. Police have immense power and play a key role for society in upholding the law, maintaining order and keeping people safe. The fundamental principle underpinning policing in this country is the Peelian principle of ‘policing by consent’. It is therefore vital that the public have confidence that the police are using their powers fairly, appropriately and responsibly. The IOPC is a vital part of a complex system that hold the police to account.

14. The UK Government created the Police Complaints Board in 1977 to be responsible for oversight of the police complaints system in England and Wales. Over time, the police complaints system has been iteratively strengthened.

15. The Brixton riots in 1981 and the Scarman report on allegations of racism in the police led to pressure to reform the Police Complaints Board. As part of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act (PACE) 1984, the Board was replaced by the Police Complaints Authority in April 1985, a body independent of the police and government.

16. Following the murder of Stephen Lawrence in April 1993, public confidence in policing was again questioned. Sir William Macpherson’s public inquiry into Stephen’s murder reported in 1999 and called for the creation of a new, independent watchdog to oversee and investigate police complaints. In addition, a study in 2000 by Liberty, the human rights organisation, argued for an independent body to investigate police complaints. This was followed by the Police Reform Act 2002 which, among other policing changes, replaced the Police Complaints Authority with a completely independent investigatory body, the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) which became operational in 2004, replacing the Police Complaints Authority. The IPCC had greater powers and its own team of investigators to probe the most serious incidents.

17. In accordance with a major change programme announced by the Home Secretary in 2013, the IPCC was subject to an expansion of its investigative remit to include “all serious and sensitive” matters involving the police. This led to significant growth in the organisation’s size and caseload over the following three years. This was accompanied by an uplift to its resources.

Recent reforms and scrutiny of police complaints system

18. In December 2014 the Government launched a public consultation on reforms to the police complaints and discipline systems (following the Independent (Chapman) Review of the police disciplinary system in England and Wales). The Government’s response to the consultation was published in March 2015 and proposed a number of structural reforms to the police complaints system to streamline complaints procedures and to introduce greater accountability, transparency and independence to the system.

19. In addition, in 2015 two reviews on the IPCC concluded. The first was a Home Office-led 2015 Triennial Review of the functions, efficiency and governance of the IPCC (March 2015). The second was an independent review, led by Sheila Drew Smith OBE in November 2015 of governance proposals put forward by the IPCC. Following these two reviews, the Home Office accepted Sheila Drew Smith’s recommendations to replace the Commission structure with a unitary board and separate single head of operational decision-making, the Director General (DG).

20. The Government legislated for these reforms to the police complaints and disciplinary systems through the Policing and Crime Act 2017. To reflect these reforms, the IPCC was renamed the Independent Office for Police Conduct.

21. The purpose of these changes was to put customer service at the forefront of complaint handling and to increase the focus on learning and improvement. The complaints system was expanded to cover a broader range of matters. Formerly, the way that the term ‘complaint’ was defined meant that it needed to relate to the conduct of an individual officer. Following these reforms, complaints could be made about a much wider range of issues, including the service provided by the police as an organisation.

22. These reforms were designed to improve access to the complaints system to ensure matters are dealt with at the appropriate level. Accordingly, police forces – and LPBs such as Police and Crime Commissioners (PCCs) – deal with most complaints, with each force having a Professional Standards Department (PSD)[footnote 5] responsible for most complaint handling.

23. They also introduced a more streamlined process, underpinned by an overarching requirement to handle complaints in a reasonable and proportionate manner.

24. Other changes aimed to increase the focus on learning and improvement with a new Reflective Practice Review Process introduced to encourage officers to reflect and learn from mistakes or errors, increasing the emphasis on finding solutions, rather than focusing on an exclusively punitive approach to errors and mistakes. As such, misconduct proceedings are now focused on serious breaches of the Standards of Professional Behaviour.

25. The governance reforms created:

- a single head of the IOPC – a DG, reflecting a desire to ensure a single line of accountability for decision-making; and

- a framework wherein the DG became the unified Chair and head of the organisation retaining all operational decision-making powers. An Office was also formed, in which a majority of members were Non- Executive directors (NEDs). It was tasked with[footnote 6]:

- ensuring the IOPC has ‘appropriate arrangements for good governance and financial management’;

- determining and promoting the IOPC’s strategic aims and values;

- ‘monitoring, reviewing’, ‘providing support to and advising the Director General in the carrying out their functions.

26. Part of the rationale for the governance changes was to remove the duality of decision-making and governance roles that existed within the remit of the Commissioners under the IPCC model where Commissioners had been decision makers on individual cases. It was perceived that a move towards a single head of decision-making would provide greater clarity and improved efficiency around decision-making, and that a ‘single voice’ in communicating decisions would help with the external perception of the body.

27. In 2020, the police complaints system was further reformed. The IOPC received new powers, including the ability to investigate without waiting for a referral from a police force and powers to present cases at police hearings. A greater emphasis was placed on taking the learning from complaints to help improve policing practice overall, to ensure an appropriate balance between holding individual officers to account and using learning from the IOPC’s work to improve policing practice.

28. These reforms also emphasised how local police forces should handle underperformance and conduct below the threshold for misconduct but which still falls short of the expectations of the service or public, to put things right through clear actions and constructive outcomes.[footnote 7]

29. In September 2020, the House of Commons Home Affairs Select Committee (HASC) began an 18-month inquiry into Police Conduct and Complaints. Its final report was published in March 2022. The Government’s response was published in April 2022. This response noted that this Independent Review would examine the IOPC’s overall governance, including the Committee’s recommendation that ‘the Government appoint an independent Chair alongside the director general of the IOPC as a matter of urgency to restore the usual checks and balances’.

Current complaints system[footnote 8]

30. Police complaints are expressions of dissatisfaction by a member of the public about the service they have received from a police force.[^9] Per IOPC Statutory Guidance: ‘A complaint can be made about the conduct of any person serving with the police, i.e. a police officer, police staff member, special constable, designated volunteer or a person contracted to provide services to a chief officer.’ [footnote 10] As of 2020, complaints can be made about policing practice and service failure, as well as individuals serving with the police.

31. The Police Reform Act (PRA) 2002, the Police Act 1996 and underpinning statutory regulations passed by Parliament and statutory guidance published by the IOPC and Home Office govern the police complaints and disciplinary systems[footnote 11]. Home Office statutory guidance covers the Police (Conduct) Regulations 2020. The PRA has been amended significantly since 2002, most notably through the Policing and Crime Act 2017 which introduced some of the most recent reforms, the majority of which came into effect from February 2020.

32. Members of the public can complain directly to a police force, to a Local Policing Body (LPB) – for example, a PCC – or they may complain via the IOPC. In the case of the latter, the IOPC is legally obliged (unless there are exceptional circumstances[footnote 12]) to refer initial complaints they receive to the relevant police force directly, except where it pertains to the chief officer of the police force, in which case they are sent to the LPB.

33. LPBs, such as PCCs, have responsibility for reviews where they are the relevant Review Body. They are also responsible for: monitoring police complaints; holding chief officers to account for the performance of their officers and staff; and directing chief officers to take remedial steps where they consider aspects of the legislative framework are not being complied with. Depending on arrangements in the local area[footnote 13], PCCs may have additional responsibilities to keep complainants and interested persons properly informed of both the progress of the handling and the complainant’s outcome.

34. By law, police forces are required to formally ‘record’ certain complaints. They must record all complaints where an individual wants their complaint recorded[footnote 14], and all that are a certain level of seriousness (e.g. where allegations, if proven, ‘might constitute a criminal offence or justify the bringing the bringing of disciplinary proceedings’[footnote 15]). In other cases, where complaints can be resolved quickly (for example, if the complainant is satisfied with an explanation they receive), a police force will log the complaint, but it will not necessarily be formally ‘recorded’ within the meaning of Schedule 3 of the PRA 2002. Formal procedures under Schedule 3 must be followed for complaints officially ‘recorded’ (e.g. complainants must be updated on the progress of their case every 28 days) and complainants dissatisfied with the outcome of the original complaint can apply for the relevant Review Body to review how their complaint has been handled.

35. Complaints about PCCs and other elected LPBs are handled by the relevant Police and Crime Panel (PCP) which challenge and support LPBs as they fulfil their duties. Any allegation of criminality concerning an elected LPB or their deputy must be referred to the IOPC which must carry out or manage an investigation if it decides one is needed.

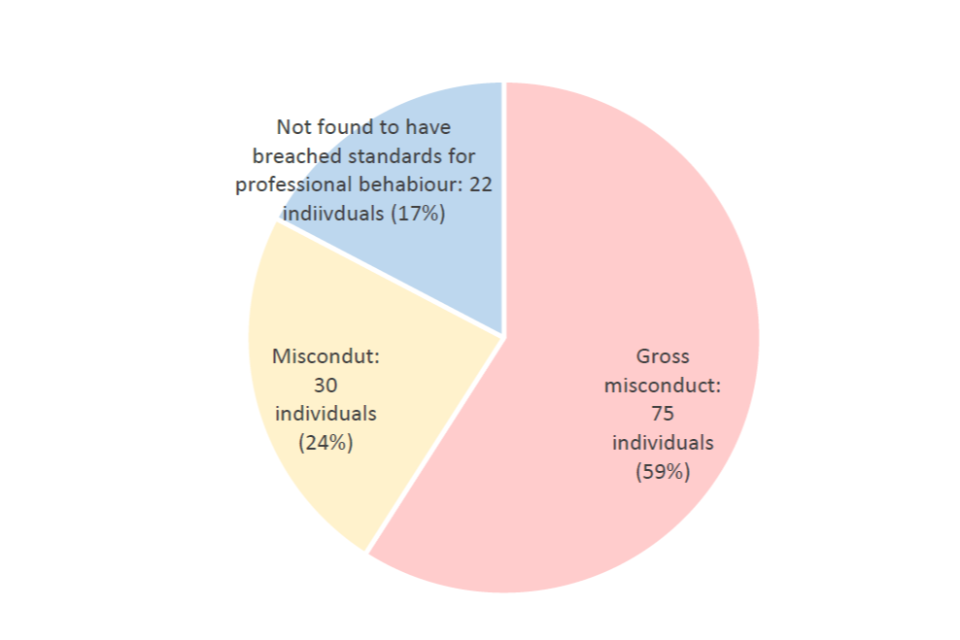

36. Exemplifying the complexity of the legislation around police complaints, ‘misconduct’ has two definitions depending on which legislation applies; either ‘a breach of the Standards of Professional Behaviour’[footnote 16] (or ‘a breach of Standards of Professional Behaviour so serious as to justify disciplinary action’ (i.e. at least a written warning). [footnote 17] ‘Gross misconduct’ is defined as ‘a breach of these standards so serious that dismissal would be justified’.[footnote 18]

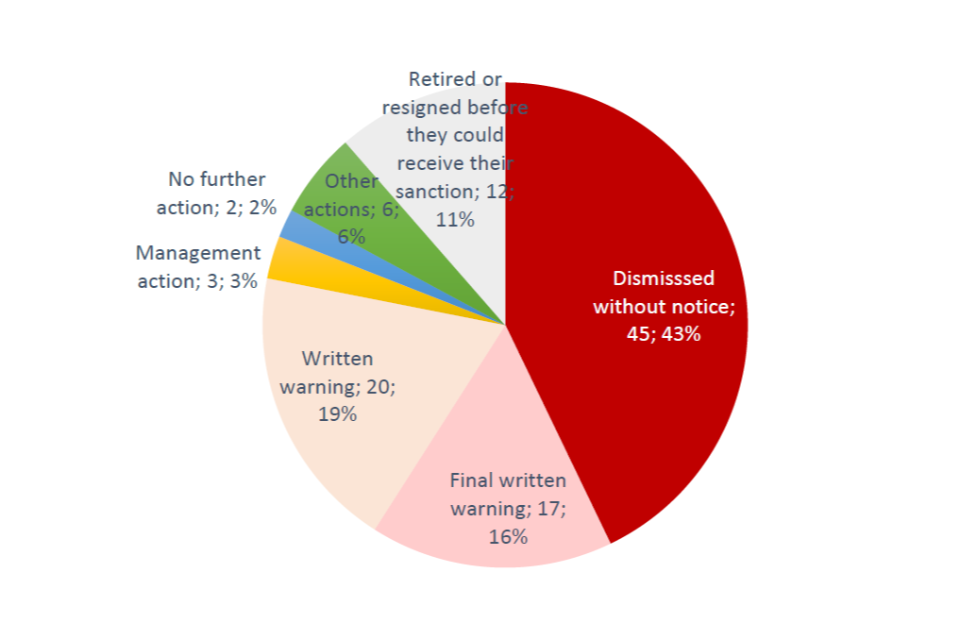

37. If a complaint is upheld, potential outcomes include:

- an apology to the complainant;

- an individual’s performance is reviewed and/or they may be referred for further training;

- unsatisfactory performance proceedings;

- individual or organisational learning, or improvements in general police practice;

- gross incompetence proceedings;

- disciplinary proceedings[footnote 19] may be brought against individuals serving with the police that have a case to answer for misconduct or gross misconduct for breaching Standards of Professional Behaviour expected of them – potentially resulting in a written warning or their dismissal[footnote 20]; and

- criminal proceedings may be brought by the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) against individuals who appear to have committed a crime.

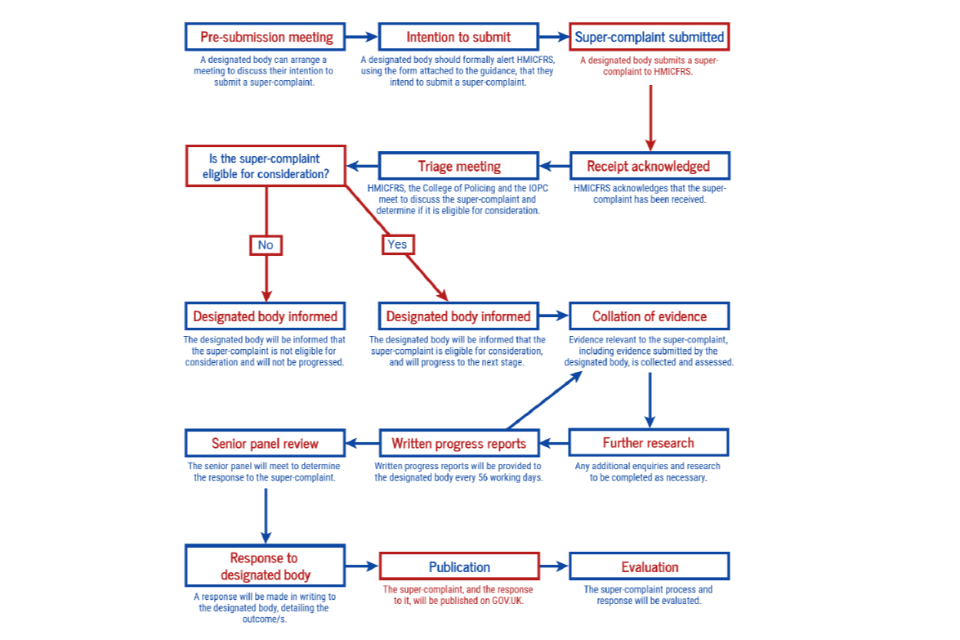

38. The IOPC plays a key role in independently investigating ‘super-complaints’[footnote 21] with HMICFRS) and the College of Policing.

Overview of IOPC role, objectives and remit

Role

39. The IOPC’s role in the complaints system and its functions are set out in the PRA 2002. Whilst its statutory functions are addressed in more detail later in the report, the IOPC is broadly[footnote 22] responsible for:

- Overseeing the complaints system – by making (and keeping under review) effective and efficient arrangements and statutory guidance in England and Wales for the police complaints system that secure and maintain public confidence in these arrangements[footnote 23], in particular, that:

- ‘contain and manifest an appropriate degree of independence’[footnote 24];

- facilitate and are conducive to reporting of misconduct[footnote 25]; and

- assist LPBs and forces to achieve high standards and comply with their legal obligations in the handling of complaints, conduct matters and death and serious injury (DSI) matters concerning those serving with the police – through the IOPC’s access to data and analysis of trends, patterns and issues[footnote 26].

- Considering applications for reviews of the handling of complaints by police forces’ PSDs (or LPBs), and whether the final outcome of these complaints, was reasonable and proportionate[footnote 27] (where it is the Review Body);

- Reviewing cases investigated by local police forces concerning a death or serious injury during or following police contact;

- Assessing cases referred to them from police forces and LPBs and deciding whether and how these should be investigated[footnote 28];

- Independently investigating the most serious complaints and incidents involving the police (including, for example, deaths in police custody, and certain deaths and serious injuries following police contact which may have caused or contributed to them);

- Independently investigating super-complaints[footnote 29] in conjunction with HMICFRS and the College of Policing; and

- Making recommendations and giving advice regarding police practice or in relation to these arrangements (as appears to the DG to be necessary or desirable).

Objectives

40. The IOPC’s 2022-2027 Strategic Plan sets out the IOPC’s mission as: ‘improving policing by independent oversight of police complaints, holding police to account and ensuring learning effects change’. It seeks to deliver this through four strategic objectives:

- (1) ‘People know about the complaints system and are confident to use it’ (Awareness and Confidence);

- (2) ‘The complaints system delivers evidence-based, fair outcomes which hold police to account’ (Accountability);

- (3) ‘Our evidence and influence improves policing’ (Leading Improvement);

- (4) ‘An organisation that delivers high performance’ (Performance).

41. The IOPC also has an internal-facing equality objective to: ensure it is fit for purpose, agile, able to manage significant expansion and representative of the communities it serves.

Remit

42. Within the forty-three Home Office police forces in England and Wales, the IOPC’s remit covers: police officers of any rank; police staff (including Community Support Officers and civilian investigators); special constables; and certain contracted staff who provide services to a chief officer.[footnote 30]

43. In addition to Home Office police forces, the IOPC’s remit extends to various other bodies (many of whom exercise police-like functions), as set out in separate agreements or legislation, namely:

- LPBs, such as PCCs and the London Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime (MOPAC), and their deputies;

- other ‘bodies of constables not maintained by LPBs, with whom it has procedures (this includes specialist police forces, such as the Ministry of Defence Police, the British Transport Police and Civil Nuclear Constabulary[footnote 31]);

- His Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC)[footnote 32];

- staff who carry out certain border and immigration functions who now work within the UK Border Force (BF) and the Home Office[footnote 33];

- the National Crime Agency[footnote 34]; and

- Labour Abuse Prevention Officers at the Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority (GLAA) [footnote 35].

- Various port police with whom the IOPC has so-called ‘section 26 agreements’ (Port of Bristol Police, Port of Liverpool Police, Port of Tees and Hartlepool Police and Port of Tilbury Police).[footnote 36]

44. Possible extensions to the IOPC’s current remit, their suitability and viability are considered in Chapter 7. Wider effectiveness of the IOPC.

Progress since the IOPC was formed

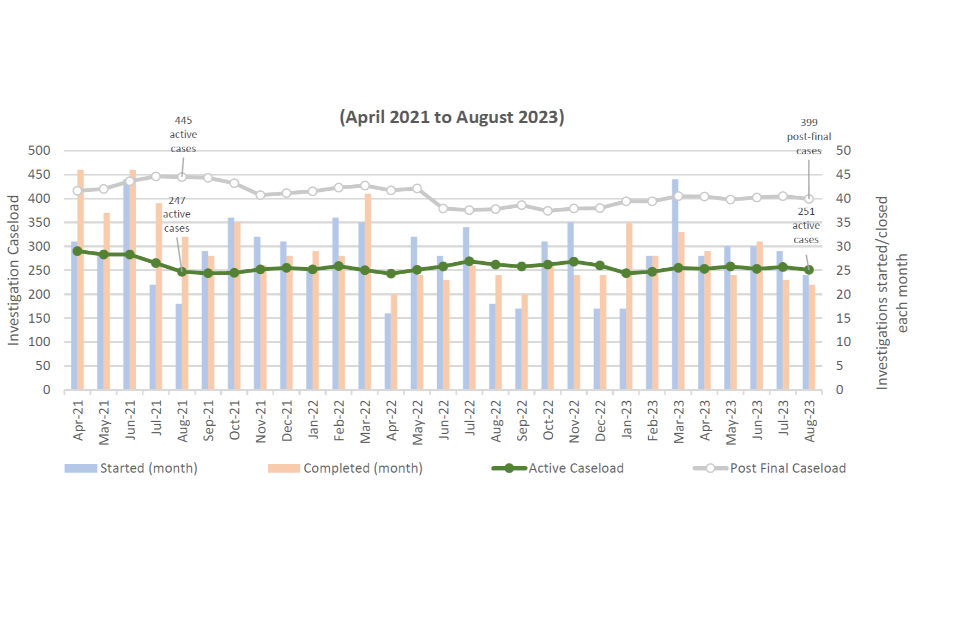

45. Since the IOPC was created, the IOPC has made progress on timeliness of its investigations. In its first five years of operation, the IOPC completed over 2,600 investigations, with 90% completed within 12 months, compared to 68% in 2018. The improvement in timeliness was acknowledged in the HASC report into Police Conduct and Complaints, published on 1 March 2022

46. The IOPC has increased its focus on system learning, including taking a more thematic approach to its work and it also carries out other types of work, such as research, stakeholder engagement and oversight to influence improvements in policing practice and the complaints system.

47. Since 2018, the IOPC has made over 850 learning recommendations to improve policing. The IOPC is working to redesign core operational processes to include:

- Improving processes for reviews;

- Implementing a new Digital Evidence Management System which enables staff to work with digital media remotely, securely and efficiently;

- Launching a Digital Investigations Unit to provide specialist support, reducing reliance on external suppliers; and

- Piloting a new investigation model focused on quick-time decision- making and improved early engagement with police forces, the Police Federation and CPS.

48. In its final report into its inquiry into Police Conduct and Complaints, published in March 2022, HASC remarked:

- ‘The IOPC has made concerted efforts in its first three years to build public trust in the police complaints system by actively listening to policing bodies and communities about their concerns and by providing greater transparency in the publication of the outcome of its investigations’

- ‘The Committee finds substantial work has been done to rectify the failings of its predecessor, the IPCC. The body has looked to build public trust, listen to policing bodies and most importantly build transparency in how investigations are carried out.

- However, it is clear that much more needs to be done. Lengthy inquiries, poor communications and opaque processes are still having a detrimental impact on complainants and officers alike…

- …complainants [feel] let down by a system failing to treat their complaints with the severity they merited’.

49. The IOPC has received some strong criticism in the media and from some prominent stakeholders in particular over the handling of some high-profile cases, for example, its report (Operation Kentia) into matters related to MPS Operation Midland and Operation Vincente.

50. On 2 December 2022, the DG resigned his position[footnote 37] and an Acting DG was appointed. Following this appointment, a series of improvement programmes has commenced to make the IOPC fit for the future, albeit many are still relatively embryonic as of September 2023. This work will be referred to in later sections of this report.

Context for this Review

The crowded space

51. The landscape and context within which the IOPC operates is challenging. The IOPC must work with a multiplicity of stakeholders as set out in the diagram provided by the IOPC below. This list of stakeholders in not exhaustive. The most complex of these groups is the statutory stakeholders with their different roles in the police complaints and disciplinary systems. Stakeholders told us they are often not clear how the different groups interact, and their relationship to each other, be it formal or informal.

The police complaints and disciplinary system

Key roles in the system

- coroners:

- inquests into the manner or cause of death (legal inquiry

- reporting the findings and issuing prevention of future deaths reports - making recommendations to the relevant organisation/s involved in the circumstances of the deceased’s death

- CPS:

- advising on cases for possible prosecution

- reviewing cases submitted by the police or other agencies

- determining charges in more serious or complex cases

- preparing cases for court

- presenting cases at court

- PCCs/elected Mayors:

- holding the chief officer to account for the exercise of their functions

- agreeing their police and crime plan and setting the force budget and precept

- engagement with the public and communities

- chief constable appointment/dismissal

- handling chief constable complaints

- handling reviews

- College of Policing:

- setting national standards of professionalism in policing (APP etc)

- supporting the education and professional development of police officers and staff

- handling super-complaints

- maintaining the barred list

- guidance on outcomes of disciplinary proceedings

- IOPC:

- oversight of the police complaints system in England and Wales

- conducting and directing investigations

- presenting at disciplinary hearings

- conducting reviews/appeals/DSI reports

- using learning to improve policing practice

- producing statutory guidance

- handling super-complaints

- chief constables:

- delivering the strategy and aims of the PCC’s police and crime plans

- overall responsibility for leading the force and accountability for operational delivery

- appropriate authority (AA) for complaints, conduct matters and DSIs

- mandatory referral of complaints conduct matters and DSIs to IOPC

- AA for misconduct proceedings

- HMICFRS:

- inspecting the efficiency and effectiveness of police forces

- thematic inspections of the police service - commissioned by the Home Office

- conducting joint inspections with other criminal justice bodies

- making learning recommendations - identifying ‘areas for improvement’ or ‘causes for concern’ in forces

- handling super-complaints

- PSDs:

- investigating complaints. misconduct and criminal allegations

- referring matters to the IOPC

- presenting at disciplinary hearings

- vetting

- counter corruption

- identifying and sharing learning

- Police and Crime Panels:

- assessing if PCCs have achieved the aims set out in their police and crime plan

- monitoring complaints against PCCs, dealing with non-criminal complaints and referring criminal allegations to the IOPC

- reviewing proposed chief officer appointments (have power to veto appointment if 2/3 of a panel vote to do so)

- LQCs:

- chairing misconduct proceedings (appointed by PCCs - usually to serve in a pool of LQCs on which their force PSDs can draw

- Home Office:

- responsible for policing police, SPR and police grants

- managing policing legislation and producing guidance on the disciplinary system

- statutory guidance for PACE and IPA codes

- sponsoring dept for the IPOD/NCA/CoP/GLAA

- Home Secretary appoints IOPC DG, the HMI, MPS Commissioner and the NCA DAG

- commissioning ‘thematic’ HMIC inspections

- responsible for policy and guidance on the police discipline system

Policing context

52. Following several high-profile police incidents and investigations, there has been a greater focus in recent years on police standards and culture and shared responsibilities for maintaining public confidence in policing.

53. Significant developments and changes with a particular bearing on the police complaints and disciplinary systems – or public confidence in policing more generally – include:

An Independent Review of Deaths and Serious Incidents in Police Custody by Rt. Hon. Dame Elish Angiolini DBE QC, published in January 2017 and to which the Government responded in October 2017. Among other areas, this review looked at investigations by the IPCC (the IOPC’s predecessor) and major issues surrounding deaths and serious incidents in police custody. These included the events leading up to such incidents, as well as existing protocols and procedures designed to minimise the risks, the immediate aftermath of a death or serious incident, and the various investigations that ensue. It also examined how families of the deceased are treated at every stage of the process.

The Police Plan of Action on Inclusion and Race, published in 2022, developed jointly by the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) and the College of Policing (‘the College’). This set out a vision ‘to create an anti-racist culture, values and behaviours within policing’ to inform all operational policing practice, improving the experience and outcomes for Black people. The NPCC and College formed and funded an Independent Scrutiny and Oversight Board (ISOB)[footnote 38] to provide overview and external scrutiny of it.

The Police Uplift Programme has improved recruitment processes so that they are now valued-led and standardised. As of March 2023, this programme has led to a 20,947 net increase in police officers in the 43 police forces across England and Wales.[footnote 39] However, alongside an increase in police complaints expected from a larger workforce, a sizeable proportion (8%) of the police workforce is less experienced. Moreover, concerns have been raised about whether there are sufficient supervisors to exercise an appropriate level of supervision for inexperienced frontline officers.

Angiolini Inquiry – established following the murder of Sarah Everard in 2021 by a then-serving officer. Part 1 of this Inquiry is focused on establishing a definitive account of the career and conduct of her murderer, and identifying any opportunities missed. The overarching aim of Part 2 is to examine broader issues in policing such as vetting, recruitment and culture, as well as the safety of women in public spaces.

Chief Constable Serena Kennedy, Merseyside Police (NPCC Lead for Crime Prevention) is co-ordinating work to check the records for all existing police officers and staff against the Police National Database (PND). This will identify any intelligence or allegations that need further investigation. Police forces completed the checks against their data returns at the end of September 2023. The NPCC intends to publish relevant data from this exercise in January 2024 or before. The NPCC are also looking at how some continuous integrity checks could be automated; which would help to quickly identify allegations against members of the force which may require investigation.

A Home Secretary-commissioned HMICFRS inspection into vetting, misconduct and misogyny in the police service reported in Nov 2022, making 43 recommendations to forces and policing bodies. The Home Secretary then commissioned HMICFRS to conduct a rapid review of progress against these recommendations in January 2023. The Rapid review was published in May 2023, concluding that there was some good interim progress but that more needs to be done. The rapid review provided a snapshot of force progress, it’s expected that significant improvements have since been made, which are being monitored by the NPCC.

The MPS published its ‘New Met for London’ strategy and delivery plan for 2023-5, its response in part to the Casey Review.

The Casey Review into MPS’ standards of behaviour and internal culture concluded in March 2023;

The College of Policing published (July 2023) an updated Vetting Code of Practice. In addition, the College of Policing is currently reviewing policing’s Code of Ethics. The current Code of Ethics, published in 2014 sets out the practice for the principles and standards of professional behaviour for the policing profession of England and Wales. The new code will include revisions to vetting practices. The Review has two broad aims:

- providing greater transparency for the public about how policing makes decisions and the standards they can expect from the service – leading to greater legitimacy, confidence and support for policing; and

- creating an environment that supports everyone in policing to be their best.

The IOPC opened (July 2023) multiple independent investigations into concerns MPS and Wiltshire police officers repeatedly failed to take appropriate action when serious criminal allegations were made against serial rapist David Carrick (arrested in October 2021), who committed offences while he was a police officer over a 17-year period from 2003-2020.

On 18 September 2023, the Home Office published its report following the HO-led review of police dismissals processes. The Government, among other things, has committed to:

- Give chief constables (or other senior officers) greater responsibilities to decide whether officers should be dismissed, increasing their accountability for their forces by having them chair public misconduct hearings;

- Creating a presumption for dismissal where gross misconduct is proven: officers found guilty of gross misconduct can expect to be dismissed;

- Ensuring officers who fail their vetting can be dismissed, making it a statutory requirement for officers to hold vetting;

- Streamlining the unsatisfactory performance procedures (UPP) making it easier to use, identifying under-performing officers and, where there is no improvement in performance, effectively dismissing them.

On 24 September 2023 the Home Secretary announced a review of investigatory arrangements which follow the police use of force and police driving related incidents. On 24 October, the Home Secretary published the review’s terms of reference. The Home Office will lead this review, working with the Ministry of Justice and Attorney General’s Office, with the aim to provide findings to the Home Secretary by the end of 2023. Areas the review will assess include:

- the existing legal frameworks and guidance on practice that underpin police use of force and police driving;

- the subsequent framework for investigation of any incidents that may occur, in particular whether:

- the system of examining DSIs following police contact is working effectively for the police and the public;

- the requirements for police referrals of DSIs and other matters to the IOPC are appropriate;

- the thresholds for launching a misconduct or criminal investigation are appropriate, and whether cases involving those acting in the line of duty should be treated differently; and

- the thresholds for the IOPC to direct disciplinary proceedings or to refer a matter to the CPS should be amended, and whether cases involving those acting in the line of duty should be treated differently.

- the timeliness of investigations and legal processes, including whether:

- the system can deliver more timely outcomes for police officers and the public, focusing on DSI cases specifically, including options for time limits and fast-tracking for investigations on the grounds of public interest;

- more effective working between IOPC and CPS can reduce timescales in criminal investigations;

- there is scope to reduce duplication in the criminal, coronial and misconduct processes and whether more activity can happen in parallel, whilst ensuring that ongoing or concluded criminal proceedings are not prejudiced or interfered with;

- how post-incident learnings and communications can improve both officers and the public’s confidence in these frameworks.

Public confidence in policing

54. A range of survey evidence[footnote 40] indicates public confidence in police has fallen materially over recent years. For example, confidence in the MPS fell steadily from 69% in June 2017 to 50% in March 2023.[footnote 41] The IOPC’s function in maintaining public confidence in the police complaints system and its contribution to public confidence in policing remains vital, as it explains in its Statutory Guidance[footnote 42]:

‘The way in which complaints, conduct matters and death and serious injury matters are dealt with has a huge impact on confidence in the police. Where they are dealt with well, it helps to restore trust, bring about improvements in policing and makes sure something that has gone wrong does not happen again. Where they are dealt with badly, it damages confidence in both the police and the police complaints system.’

55. This Review takes place at a critical time for trust and confidence in policing and specifically police misconduct. The public are understandably concerned about officer misconduct (and criminality) and have questions about the police misconduct regime and how it works. We consider public confidence in policing and the IOPC in Chapter 7. Wider effectiveness of the IOPC

56. The rise of social media and other rapid communication channels means that the complaints system often must react and respond in real time to incidents for which it may not be prepared. Failure to respond quickly to significant incidents and to engage with community groups appropriately may result in significant unrest.

Demand on the police complaints system

57. Since the IOPC was established in 2018, the overall number of police complaints has risen significantly[footnote 43]. Roughly 1 in 5 of the overall police workforce (51,720) were the subject of a complaint over 2022/3 [footnote 44]. The IOPC and its stakeholders expect the number of police complaints to continue rising in the short-term.

58. The IOPC will receive around 1,000 DSI matters investigated by local police forces themselves (having reviewed 933 in 2022/23).

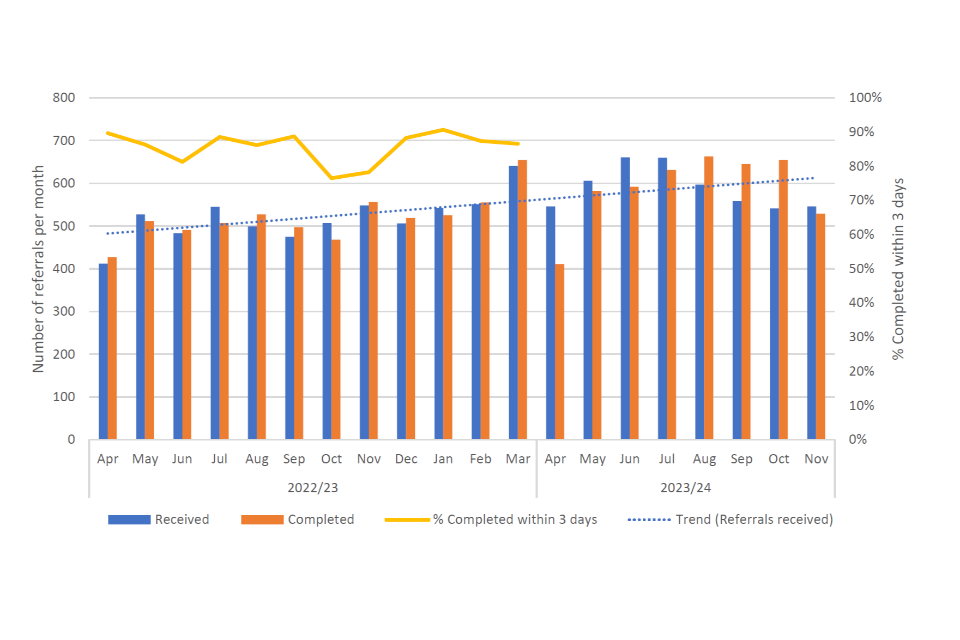

59. Depending on the circumstances[footnote 45], the IOPC or LPBs are required to consider complainants’ applications for a review of whether their complaint was considered in a ‘reasonable and proportionate’ manner. [footnote 46] This is without regard as to whether the complaint was investigated by the police force or LPB.[footnote 47] In the first year (2020/21) after reforms replaced the previous system of ‘appeals’ with this system of ‘reviews’, the IOPC received 969 applications. By 2025/26, the IOPC projects it will receive 2,025 applications, as set out in Chart 1 below.

60. The IOPC’s published target for 2023/24 is for it to ‘review locally investigated DSI cases within an average of 30 working days from receipt of background papers’. Over 2021/22, these reviews took on average 29 working days. By Q4 2022/23, this had slipped to 42 working days.

Chart 1: applications received by the IOPC for it to review complaints handled by other bodies

| Year (actual reviews) | Reviews received by the IPOC |

|---|---|

| 2020/21 | 969 |

| 2021/22 | 1,643 |

| 2022/23 | 2,003 |

| Year (projected reviews) | Reviews received by the IPOC |

|---|---|

| 2023/24 | 2,024 |

| 2024/25 | 2,045 |

| 2025/26 | 2,025 |

61. By law, police forces and LPBs are required to refer the most serious complaints[footnote 48], conduct matters[footnote 49] , and deaths and serious injuries[footnote 50] (where there is an indication that police contact caused or contributed to the death or serious injury) to the IOPC. The IOPC has a dedicated Assessment Unit which assesses referrals to determine whether an investigation is required and, if so, what form this should take (e.g. which complaints should be investigated independently by the IOPC, which complaints should be sent back to a local police force or LPB to investigate (a local investigation), or led by the local police force or authority, but under the IOPC’s direction (a directed investigation).

62. If the number of police referrals to the IOPC continues to climb as the IOPC projects, police referrals to the IOPC will have more than doubled since the IOPC was established (from 4,097 referrals in 2018/19 to 8,765 projected referrals in 2025/26). (See Chart 2 below).

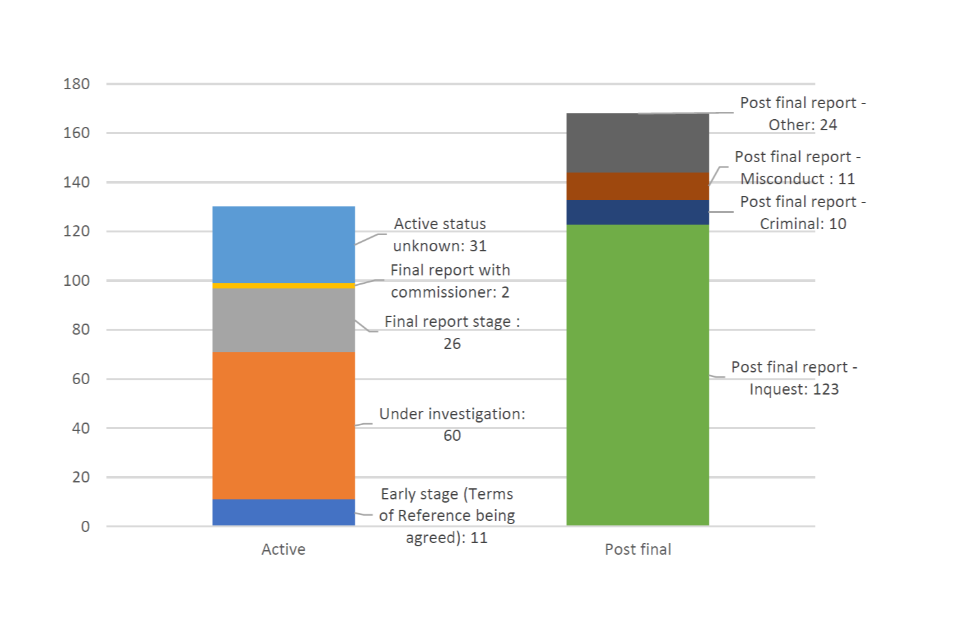

63. In the five years since the IOPC was established, the number of independent investigations the IOPC undertakes each year has fallen significantly (to a projection of between 260 and 280 core investigations in 2023/24). There are multiple causes of the IOPC conducting far fewer independent investigations (e.g. increasing case complexity, the IOPC having to prioritise its increasingly- strained resources to investigate the serious complaints and conduct matters). Indeed, in Chapter 5. Effectiveness of IOPC investigations we consider some of these in a detailed assessment of why the IOPC has not been able to further reduce the length of its investigations, despite this huge fall in the number of IOPC investigations.

64. Nonetheless, regardless of the causes of this fall in independent investigations, one key impact – with referrals continuing to rise – is that a much smaller proportion of complaints will be investigated independently by the IOPC: from 1 in 6 (16.7%) in 2018/19, to 1 in 28 (3.6%) this year (2023/24), and 1 in 32 (3.1%) by 2025/26. This could impact public confidence in the system.

Chart 2: referrals from police forces and others to the IOPC vs. IOPC investigations started

Macro-economic context and financial outlook

65. Since it was established (2018/19 to 2023/24), the IOPC has had a 22.7% real- terms cut to its funding (after inflation is accounted for).

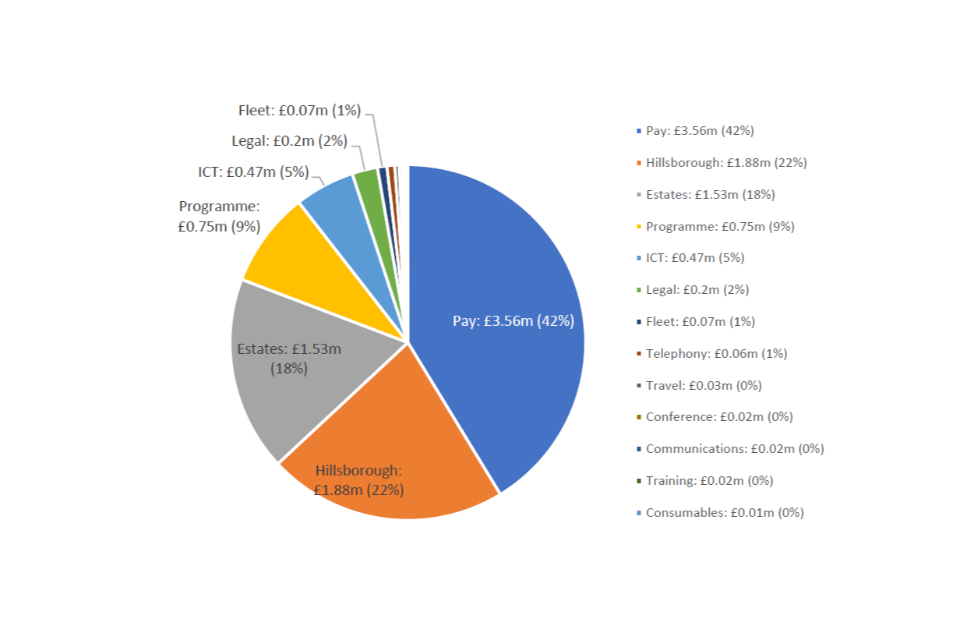

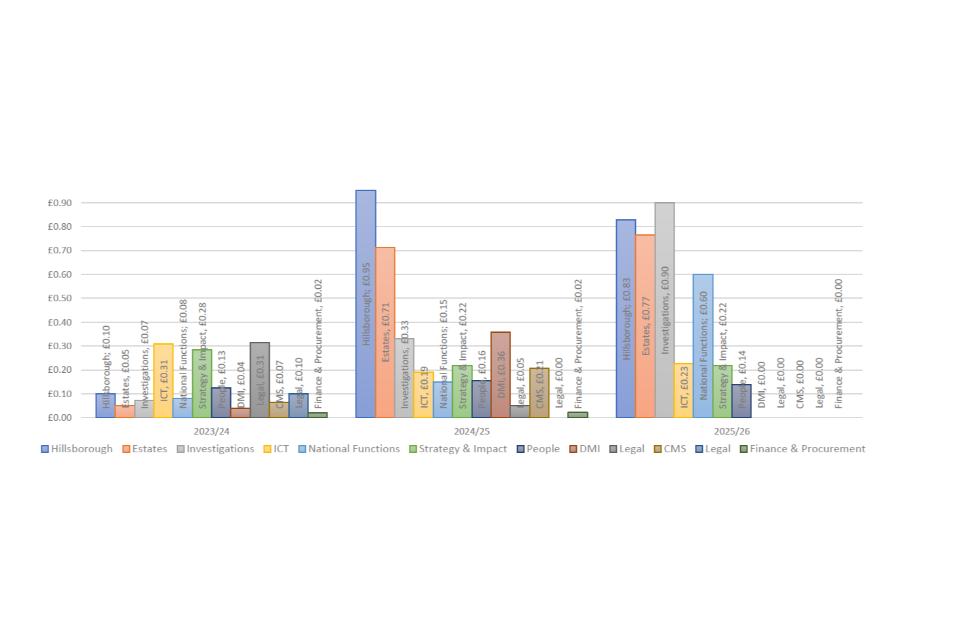

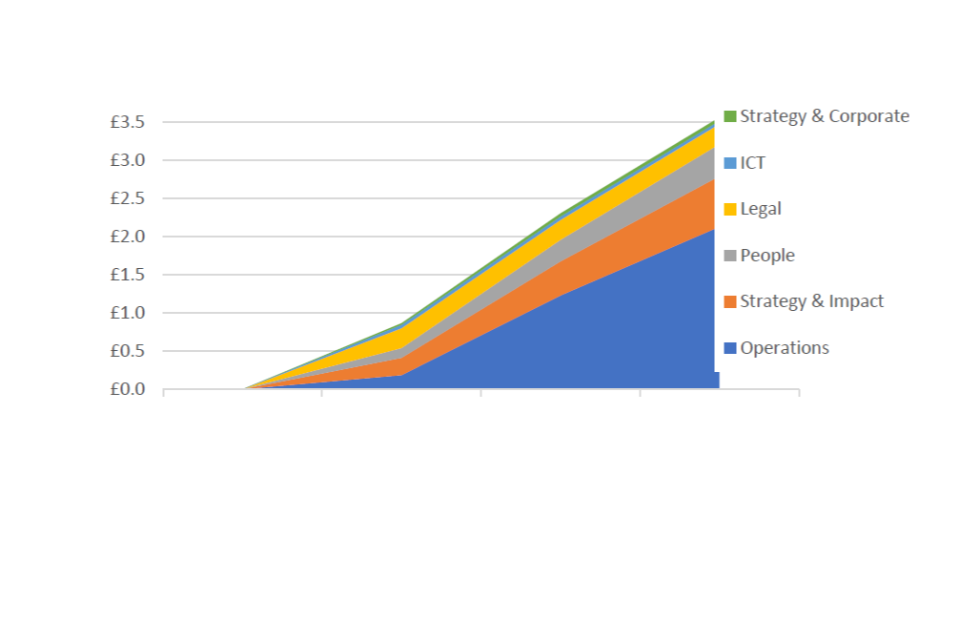

66. The Home Office is expected to apply a further 5% cut to the IOPC’s RDEL budget in nominal (cash) terms (from 2022/23) over the next three years following this Public Body Review (in line with expectations that each such review identify at least 5% RDEL savings)[footnote 51]. As set out in Chart 3, on current forecasts, the IOPC would see a 34.4% fall to its real-terms budget in the 7 years since its establishment in 2018/19.

Chart 3: OPC Funding Cash Budget vs. Real-terms funding (compared to 2018/19)

67. This Review has been carried out in the context of increasing case complexity, crowded stakeholder landscape, declining public confidence, increasing demand on the complaints system, a falling number of independent investigations carried out each year and significant financial pressures. The IOPC is also in a period of instability following the resignation of its DG. That being said, it is vital that the IOPC and its sponsor department, with the support of key stakeholders, tackle the key issues set out in this Review in order for the IOPC to play its significant role in the complaints system.

68. We now turn to address the findings and recommendations of our Review.

Chapter 3. Effectiveness of reviews

69. The IOPC has some operations organised nationally and its ‘core investigations’ organised regionally. The IOPC’s ‘National Operations Directorate’ leads reviews of the handling of complaints and death and serious injury cases handled by other bodies; assessments of referrals; and delivers the IOPC’s customer contact centre.[footnote 52]

70. The IOPC has two further centralised directorates which lead the IOPC’s ‘major’ independent investigations and its independent investigations into the Hillsborough disaster. The IOPC’s ‘core’ investigations - that the IOPC leads independently, or directs – are delivered, by contrast, on a regional basis, with responsibility delegated by the DG to the Director for Wales and the South West England, or one of five other Regional Directors across England (North East, North West, Midlands, London, South East). The Strategy and Impact Directorate – which is separate to the IOPC’s Operations directorates – co- ordinates the IOPC’s work on super-complaints, drawing on colleagues across operations, policy, research and legal teams as necessary.

71. This chapter considers the effectiveness of reviews. Effectiveness can be described as the degree to which any actions result in desired outcomes.

72. We consider:

- the effectiveness of IOPC assessment of referrals from police and others in Chapter 4. Effectiveness of IOPC assessment of referrals from police and others;

- the effectiveness of IOPC investigations (including Hillsborough) in Chapter 5. Effectiveness of IOPC investigations; and

- super-complaints in Chapter 6. Overarching considerations for reviews, referrals and investigations

73. The IOPC leads two, quite different, types of reviews:

- reviews of how complaints have been handled by Appropriate Authorities; and

- reviews of investigations by local police forces into deaths and serious injuries during or following police contact.

74. Both types of reviews are handled by ‘casework managers’ in the IOPC’s National Operations team.

IOPC reviews of complaint handling

75. Following reforms to the police complaints and disciplinary system introduced in 202053, complainants have a right to apply to the relevant ‘Review Body’ to ‘review’ whether their complaint has been handled in a ‘reasonable and proportionate’ manner[footnote 54]. This single point of potential ‘review’ at the end of the complaints process replaced five previous points of ‘appeal’.

76. Complainants have 28 days to lodge an application for a review of how their complaint was handled[footnote 55], from the date of the letter informing them of the complaint outcome. Review Bodies must determine whether the outcome is reasonable and proportionate[footnote 56].

77. A detailed overview of the process for reviews of complaint handling is found at Annex C – Detailed process of reviews.

Forecasting of demand for reviews of complaints handled by police forces[footnote 57]

78. In 2022/23, the IOPC received 2,003 applications to review complaints dealt with by police forces’ Professional Standards Departments[footnote 58], a 24% increase on 2021/22[footnote 59].

79. The IOPC completed 1,590 such reviews over 2022/23. This was strictly up 8% on the year before but, in reality, the comparable increase was higher[footnote 60].

80. Over the last year, the IOPC’s National Operations unit has developed a forecasting capability; it is currently projecting that applications for IOPC reviews – over which the IOPC has no control (unlike the number of independent investigations it conducts) – will remain similar in the coming years. Chart 4 shows the number of applications for review of complaint handling the IOPC has received and it projects it will receive over coming years.

81. Notably, in terms of the types of reviews the IOPC conducts, the IOPC advised us that it is commonly looking at the most time-consuming reviews.[footnote 61]

Chart 4: application received by the IOPC for it to review complaints handled by other bodies

| Year (actual reviews) | Reviews received by the IOPC |

|---|---|

| 2020/21 | 969 |

| 2021/22 | 1,643 |

| 2022/23 | 2,003 |

| Year (projected reviews) | Reviews received by the IOPC |

|---|---|

| 2023/24 | 2,024 |

| 2024/25 | 2,045 |

| 2025/26 | 2,025 |

Performance and evaluation

82. Following the 2020 reforms, the number of applications for reviews the IOPC is receiving is lower than the number of appeals it used to receive. However, as the IOPC began to receive and consider reviews of complaint handling, it became clearer that each review under the new system took significantly more time than the system of ‘appeals’ it replaced.

83. We cannot offer a view on the degree to which this was reasonably foreseeable, but the result was that the IOPC found it could not keep on top of the reviews it received, the time it took to conclude reviews increased and a very large backlog of reviews developed.

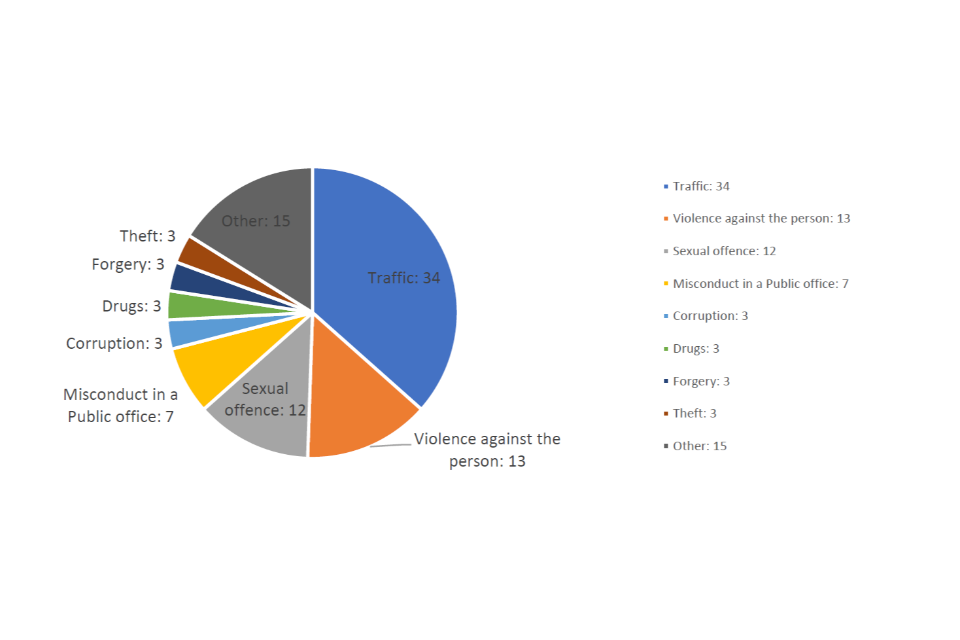

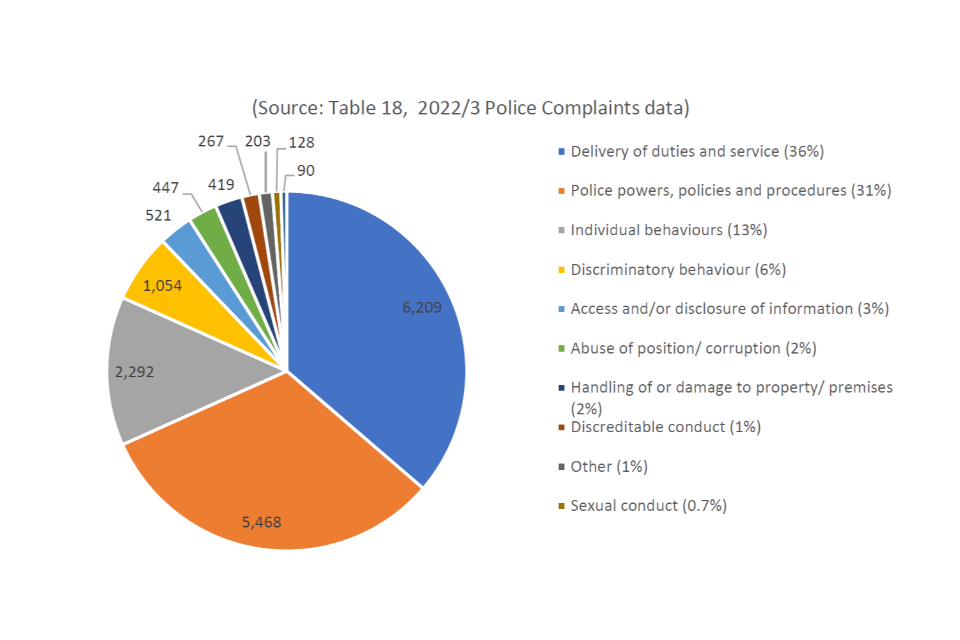

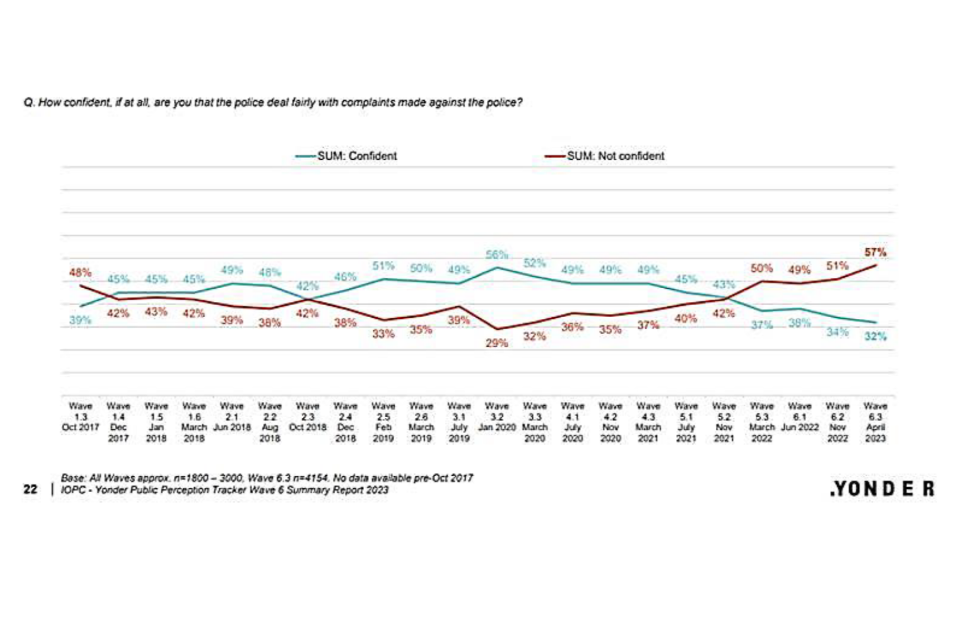

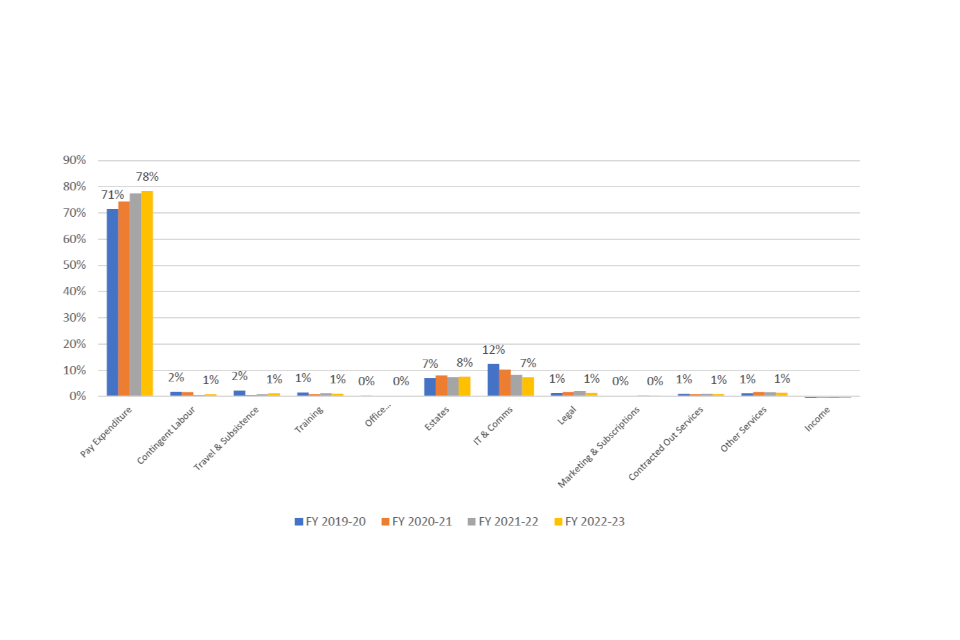

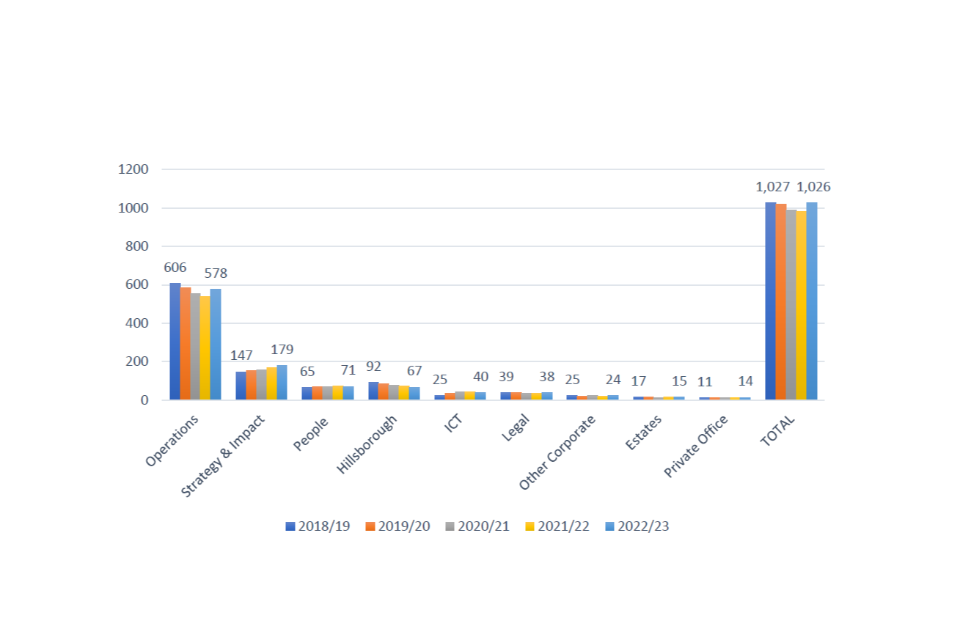

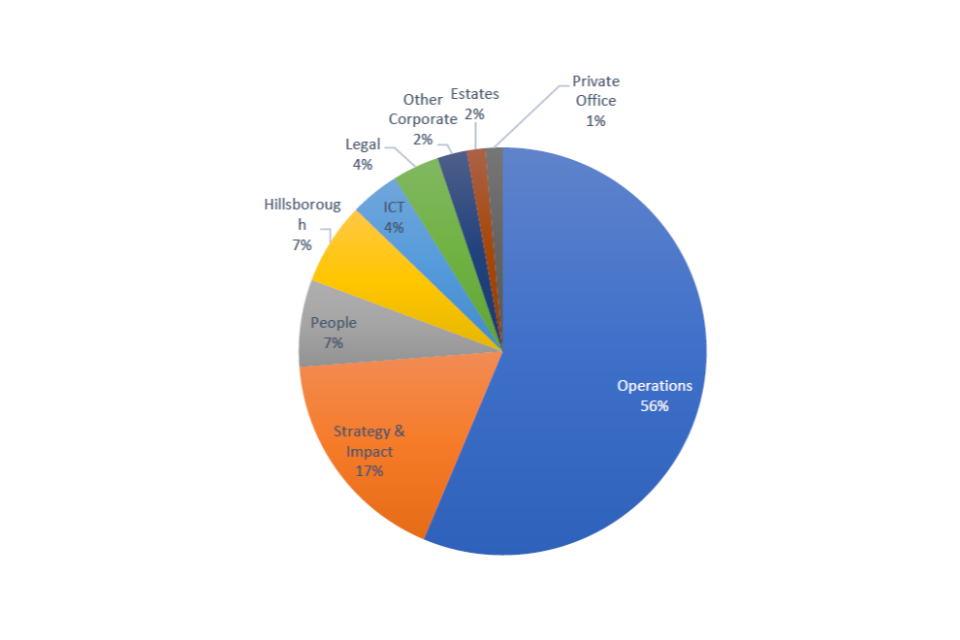

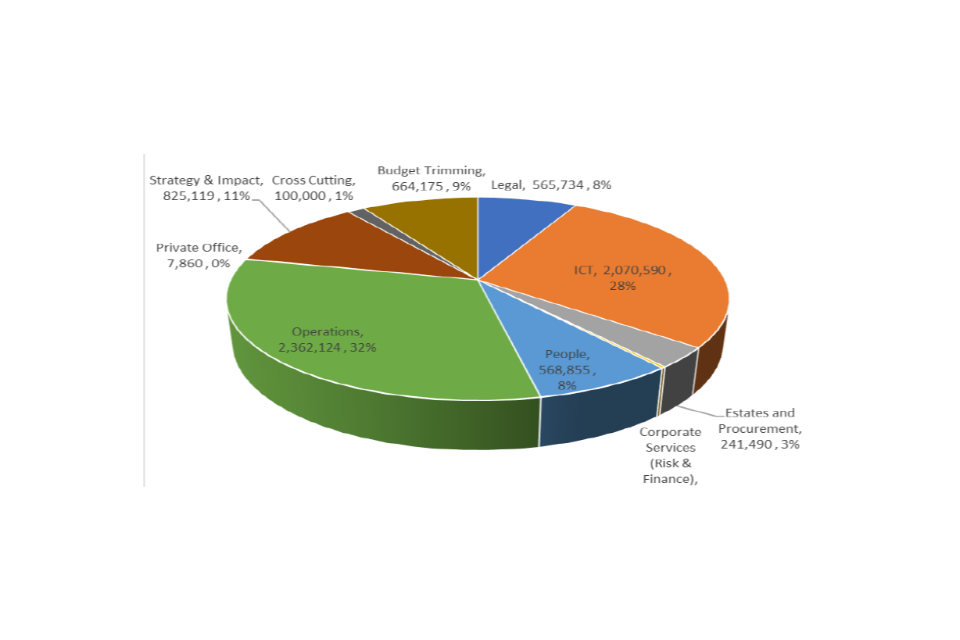

84. As a result of this deteriorating performance, in April 2022 the IOPC’s Management Board agreed a ‘National Operations Turnaround Plan’ including funding for additional resources to tackle the backlog; improve timeliness; and ultimately bring performance levels back to its original target when ‘reviews’ were introduced: 50 working days (the time the IOPC took to complete ‘appeals’ pre-2020).