Inspecting local authority children’s services

Updated 13 August 2025

Applies to England

Introduction

1. This document sets out the framework for inspecting local authority children’s services (ILACS). We first published this framework in November 2017. We last updated this framework in April 2025. There is a summary of the changes available.

2. This framework and guidance are to help inspectors to be consistent in inspections while being flexible enough to respond to the individual circumstances of each local authority. When applying this guidance, inspectors will take appropriate action to comply with Ofsted’s duties under the Equality Act 2010. We will periodically review and amend this framework and evaluation criteria.

3. These inspections focus on the effectiveness of local authority services and arrangements:

-

to help and protect children, and enable families to stay together and get the help they need

-

the experiences and progress of children in care wherever they live, including those children who return home

-

the arrangements for permanence for children who are looked after, in stable, loving homes, including adoption

-

the experiences and progress of care leavers

We also evaluate:

-

the effectiveness of leaders and managers

-

the impact they have on the lives of children and young people

-

the quality of professional practice delivered by a workforce that is equipped and effective

4. In law, the term ‘children in care’ refers to those who are subject to a care order. However, in this framework and the associated inspection reports we have chosen to use ‘children in care’ to refer to all looked after children and young people because it is what this group have told us they prefer.

5. Certain children and young people are legally entitled to leaving care support from their local authority. In this framework we refer to them as ‘care leavers’ to reflect their legal status and to make the scope of this framework clear. However, we may also use the term ‘care experienced young people’ in our inspection reports because this reflects what many young people have told us they prefer.

Inspection principles

6. Ofsted’s corporate strategy outlines how we will carry out inspection and regulation that is:

-

intelligent

-

responsible

-

focused

7. Our approach to ILACS is further underpinned by 3 principles that apply to all social care inspections. Inspection should:

-

focus on the things that matter most to children’s lives

-

be consistent in our expectations of providers

-

prioritise our work where improvement is needed most

Whole-system approach

8. ILACS is a system of inspection. Under this system, we use the intelligence and information we have to inform decisions about how best to inspect each local authority. Local area arrangements for children and young people with special educational needs and/or disabilities (area SEND) inspections are inspections of the local area that sit outside ILACS, but we will take them into account when we schedule inspections.

9. The ILACS system includes:

-

local authorities sharing an annual self-evaluation of the quality and impact of social work practice

-

an annual engagement meeting between our regional representatives and the local authority to review the self-evaluation and to reflect on what is happening in the local authority and inform how they would engage with each other in future

-

our local authority intelligence system (LAIS) (which brings data and information into a single record)

-

focused visits that look at a specific area of service or cohort of children

-

standard and short inspections where we make judgements using our 4-point scale

We have described each part of this system in more detail later in the framework.

Applying a proportionate and risk-based approach to inspection

10. There is no fixed cycle or end date for the ILACS programme. We use the intelligence and information we have to inform decisions about how best to inspect each local authority.

11. There will be times when concerns arise about a local authority. The regional director will decide whether to carry out an inspection (standard or short inspection), at which we make a graded judgement, or whether a focused visit would be more appropriate. In most cases, if the next standard or short inspection is not due, we will carry out a focused visit. This gives the local authority and us the opportunity to identify what is going well and what needs to improve before the next judgement inspection.

12. After a focused visit, we will not usually follow up with an urgent inspection. We will publish the focused visit letter setting out the areas that the local authority needs to address. We will review the progress in these areas through the local authority’s self-evaluation and the annual engagement meeting until the next judgement inspection happens. This approach aims to support improvement, while still holding the local authority children’s services to account in meeting their legal responsibilities to children in need of help, protection and care.

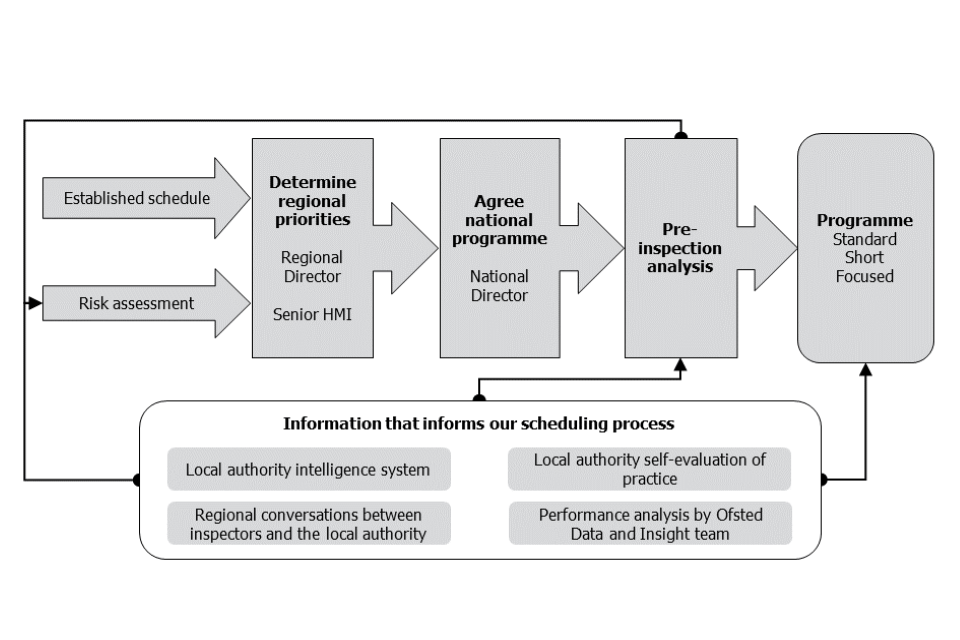

13. Within the ILACS system, deciding which type of inspection to deploy in which local authority is a complex and dynamic process. Figure 1 sets out this process.

Figure 1. Steps for agreeing the ILACS inspection programme

This is a flow chart that shows the steps we follow to decide which local authorities we will inspect and visit under the ILACS framework.

Proportionate timing of inspection

14. We will inspect local authorities based on the intelligence we have about them and their most recent inspection judgement. Standard and short inspections will usually happen once every 3 years, plus or minus 6 months. Figure 2 summarises the different inspection pathways we use depending on the most recent inspection judgement.

Figure 2. The proportionate inspection pathways for ILACS

15. Inspections will not usually begin over the Christmas and New Year period. The only activities that might take place in August are planned monitoring visits and focused visits by agreement, or if concerns arise.

16. Each Ofsted region will decide when to inspect each local authority and whether to carry out a standard inspection, short inspection or focused visit. The national programme will be agreed by the national director, regulation and social care.

Deferring an inspection

17. While it is important that we carry out our planned inspections wherever possible, we understand that sometimes there may be reasons that this is not possible. The local authority can request a deferral of an inspection or visit after they have been notified and before fieldwork starts. We will decide whether a deferral should be granted in accordance with our policy.

Pathway 1: local authorities judged good or outstanding at their most recent inspection

18. Local authorities judged to be good or outstanding at their most recent inspection will usually receive a short inspection. The short inspection will usually take place about 3 years after the previous inspection. If that short inspection results in the local authority being judged requires improvement to be good, it will move to pathway 2.

19. In between inspections, the local authority will usually receive one focused visit or a JTAI.

20. We may decide to carry out a standard inspection if we have information or intelligence that suggests this is necessary to assure ourselves of the quality of the local authority’s practice. Our decision to do this will be based on everything we know about the local authority rather than on any single factor. If we are considering carrying out a standard inspection, a regional representative will discuss this with the director of children’s services (DCS), usually at the annual engagement meeting. Examples of things we will consider are:

-

if we identify an area for priority action on a focused visit or concerning practice from other inspections that are relevant to the help, protection and care of children (for example JTAIs, area SEND or children’s homes run by the local authority)

-

if there have been significant changes in senior leadership and either we or the local leaders want assurance that the local authority has a good understanding of the experiences of children and the quality of frontline practice

-

if the local authority self-evaluation and/or discussions at annual engagement meetings identify weaknesses and it is unclear what action the local authority is taking to ensure practice remains good or better

-

if there have been child serious incident notifications, whistleblowing concerns and/or complaints that suggest a pattern of concerns, and we need assurance about the local authority’s response

-

if a local authority has been managing complex contextual factors that require more time from inspectors to understand and evaluate the local response. Ofsted would discuss the significance and impact of these factors with the DCS before deciding on the appropriate inspection arrangements

Pathway 2: local authorities judged requires improvement to be good at their most recent inspection

21. Local authorities judged to require improvement to be good at their most recent inspection will receive a standard inspection. The standard inspection will usually take place about 3 years after the previous inspection. If that standard inspection results in the local authority being judged good or outstanding, it will follow the process described in pathway 1.

22. In between inspections, the local authority will receive up to 2 focused visits. A focused visit may be replaced by a JTAI.

Pathway 3: local authorities judged inadequate at their most recent inspection

23. Local authorities judged inadequate at their most recent inspection will receive monitoring visits followed by a reinspection. We will usually carry out between 4 and 6 monitoring visits before the reinspection. We will reinspect an inadequate local authority using a standard inspection.

24. If, at the reinspection, its overall effectiveness grade improves, that local authority will then enter the relevant pathway. Should it remain inadequate, it will remain in pathway 3.

The table below summarises the range of events that will exist under the ILACS system by the Ofsted inspection grade.

| Most recent inspection judgement | ILACS events |

|---|---|

| Good or outstanding local authority | Short inspection (once in a 3-year period) Usually 1 focused visit in between inspections Possible JTAI (would replace a focused visit) Shared self-evaluation Annual engagement meeting |

| Requires improvement to be good local authority | Standard inspection (once in a 3-year period) Up to 2 focused visits in between inspections Possible JTAI (would replace a focused visit) Shared self-evaluation Annual engagement meeting |

| Inadequate local authority | Monitoring visits Standard inspection (after we have completed monitoring visits) Shared self-evaluation Annual engagement meeting |

ILACS and other joint inspections

25. We will coordinate the scheduling of the ILACS, JTAI and area SEND programmes to avoid any clash of timing and to minimise the burden on local authorities. The scope of ILACS does not replicate that of the area SEND inspection.

26. The 4 inspectorates (Ofsted, Care Quality Commission (CQC), His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services (HMICFRS) and, when applicable, His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Probation (HMIP)) remain committed to carrying out up to 12 JTAIs a year. The scheduling of the JTAIs is a complex task. We try to avoid any unnecessary clash of timing and minimise the burden on each of the inspected bodies.

Activity outside of inspection

Local authority self-evaluation of social work practice

27. Each year, we will ask local authorities to share a self-evaluation of social work practice with us and to meet with our regional representatives to discuss it. This part of the framework is voluntary but it plays an important role in our understanding of local authorities and how they work. We have developed this section in conjunction with the Association of Directors of Children’s Services (ADCS), The Society of Local Authority Chief Executives (SOLACE) and the Local Government Association (LGA).

28. Engagement between us and local authorities outside of inspection will help us to apply the risk-based and proportionate approach that ILACS offers. It will help us to carry out our inspections and visits more efficiently. It will also help ensure that inspection frequency and arrangements are appropriate to that local authority.

29. We ask local authorities to share an annual self-evaluation of social work practice with us. This will help us to see whether leaders and managers have a grip on practice and are taking suitable action. We also ask them to share information about how their services are structured and where they are located. This will help inspectors to consider any logistical and practical issues before the inspection.

30. We will not ask local authorities judged inadequate to share a self-evaluation until the monitoring visits in the first 12 months are complete. Engagement (outside the monitoring visits) will focus on the quality of the local authority action planning.

31. The self-evaluation should draw on existing documentation and activity. It should reflect the local authority’s business as usual in order to avoid additional burden. We do not expect local authorities to carry out additional work to inform the self-evaluation.

32. Inspectors look at a local authority’s most recent self-evaluation when preparing for the next inspection or focused visit.

33. The self-evaluation should answer 3 questions:

-

What do you know about the quality and impact of social work practice in your local authority?

-

How do you know it?

-

What are your plans for the next 12 months to maintain or improve practice?

34. There is no set time each year that we ask local authorities to share a self-evaluation. The timing should take into account any planned regional peer review and challenge activity. To be most effective, this should happen before the planned annual engagement meeting, but there is no expectation that local authorities schedule their work around our timelines. Ideally, we ask the local authority to share this early enough for us to analyse its content, but not so far in advance that the information is out of date by the time of the annual engagement meeting.

35. When there is a significant gap between sharing the self-evaluation and the annual engagement meeting, it is helpful if the local authority can refresh the self-evaluation with the most up-to-date data and information. A regional representative will contact the director of children’s services (DCS) to agree appropriate arrangements.

36. There is no prescribed format or content for the self-evaluation. Local authorities should apply the following principles. The self-evaluation:

-

should answer the 3 questions outlined above

-

should set out the main themes and learning

-

should make sense as a standalone document (appendices can be included, but should be kept to a minimum)

-

may be an existing document or combination of documents

-

should be succinct, focused and evaluative; overly long self-evaluations are unlikely to be helpful to the local authority or inspectors

37. It is for the local authority to determine which documentation and information to draw on for the self-evaluation. The following list offers some suggested sources:

-

an overview of how the local authority evaluates the impact of social work practice with children and families

-

high-level performance reports that give the most recent position of the local authority case audit plans

-

case audit summaries of learning

-

outcome of multi-agency section 11 audit work

-

recent learning about frontline social work practice, for example from complaints, rapid reviews, child safeguarding practice reviews or management reviews

-

feedback from children and families

38. If the self-evaluation identifies weaknesses in practice and the local authority has credible plans to take clear, appropriate and effective action in response, we will treat this as effective leadership rather than an automatic trigger for an inspection or focused visit. Our regional representatives will discuss these issues with the local authority at the annual engagement meeting.

Annual engagement meeting

39. This meeting may be solely about children’s social care or part of a broader meeting covering education and early years. This will be determined by the region.

40. The meeting should be carried out in a spirit of positive transparency and benefit everyone involved.

41. The meeting is not an opportunity for inspectors to evaluate direct social work practice with children and families. The intelligence gathered from the meeting will inform any plans for future inspection activity and focused visits.

42. The meeting should cover:

-

the content of the self-evaluation – what leaders know about practice and outcomes, and the evidence that supports this

-

the impact of the self-evaluation – what leaders are doing to address weaknesses in practice and maintain or improve good practice, including evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of their actions

-

actions taken in response to previous inspections

-

the local authority’s current financial, political and professional practice context

-

whether multi-agency working is prioritised and effective

-

the broader issues that affect delivery of children’s social care services, for example schools and early years provision

-

the possible scope of a focused visit

-

the approximate timing of the next self-evaluation and annual engagement meeting

-

(for good and outstanding local authorities) whether Ofsted is considering carrying out a standard inspection

43. The annual engagement meeting will be planned for a mutually convenient time but does not need to be at exactly the same point in time every year. Its timing will usually be linked to when the local authority shares its self-evaluation so that the information is up to date.

44. The timing of the annual engagement meeting should take into account planned peer review arrangements and activity relating to a regional improvement alliance.

45. A regional representative from Ofsted will chair the meeting. The meeting may focus on other local authority duties, for example in relation to school inspection, but it should include the appropriate personnel and allow sufficient time for children’s social care issues to be explored.

46. The DCS and our regional director and/or social care Senior His Majesty’s Inspector (SHMI) or His Majesty’s Inspector (HMI) will attend. The DCS has professional responsibility for children’s services, including operational matters, as set out in the ‘Statutory guidance on the roles and responsibilities of the Director of Children’s Services and the Lead Member for Children’s Services’. It is for the DCS to determine who else attends from the local authority, for example the assistant director responsible for social care or the practice leader. For the meeting to be effective, those attending the meeting should have a clear purpose for being there. The regional SHMI and the DCS will agree the agenda in advance of the meeting.

47. We will write to the DCS within a month of the meeting. The letter will not be published nor contain any judgements about practice. It will set out:

-

the date of the meeting and who attended

-

a factual summary of the agenda items discussed

-

the possible scope of a future focused visit

-

the approximate timing of the following year’s self-evaluation and annual engagement meeting

-

any next steps

Scope

48. This section sets out the children whose experiences inspectors will evaluate during inspections and visits.

49. In standard and short inspections, inspectors will evaluate the experiences of the children and young people listed below. On focused and monitoring visits, they will evaluate the experiences of one or more of these groups of children and young people:

-

who are at risk of harm (but who have not yet reached the ‘significant harm’ threshold) and for whom a preventative service would provide the help that they and their family need to reduce the likelihood of that risk of harm escalating and to reduce the need for statutory intervention (these children may be known by any person with a duty under the Children Act 2004; the Childcare Act 2006; section 175 or any regulations made under 157 of the Education Act 2002; the Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Act 2009, a member of the local safeguarding partnership; or a person associated with a commissioned service, including local voluntary services)

-

who have been referred to the local authority, including those for whom urgent action has to be taken to protect them; those subject to further assessment (including children subject to private fostering arrangements, including kinship care), those subject to child protection enquiries and 16- and 17-year-olds subject to a joint accommodation assessment as set out in Provision of accommodation for 16 and 17 year olds who may be homeless and/or require accommodation

-

who become the subject of a multi-agency child protection plan that sets out the help they and their families will receive to keep them safe and promote their welfare

-

who have been assessed as no longer needing a child protection plan, but who may need continuing help and support

-

who are receiving (or whose families are receiving) social work services because there are significant levels of concern about their safety and welfare, but these have not reached the significant harm threshold or the threshold to become looked after. This may include young carers.

-

who are missing from education or are being offered alternative provision

-

who are looked after either by being accommodated under section 20 or by being placed ‘in care’ during or as a result of proceedings under section 31 of the Children Act 1989 and those accommodated through the police powers of protection or emergency protection orders (including children and young people who are detained, unaccompanied child migrants or asylum seekers)

-

who have left or are preparing to leave care, specifically:

-

those aged 16 or 17 who are preparing to leave care and meet the definition of ‘eligible’

-

those aged 16 or 17 who have left care and are ‘relevant’

-

those aged 18 and above and who are ‘former relevant’

-

those aged 18 to 25 who qualify as ‘former relevant children pursuing further education or training’

-

those aged 16 to 25 qualifying for advice and assistance who are in receipt of a service and have been allocated a social worker or personal adviser

-

-

who have left care to return home or who are living with families under a special guardianship order, child arrangements order or an adoption order

50. In addition, inspectors will evaluate:

-

the impact of leaders and managers and how they drive the conditions for effective social work practice with children and families

-

whether the local authority’s own evaluation of the quality and impact of its performance and practice is accurate.

Standard and short inspections

51. HMI carry out these inspections under section 136(2) of the Education and Inspections Act 2006 (EIA). His Majesty’s Chief Inspector (HMCI) has the power to carry out ILACS functions as listed in section 135 of the EIA.

52. Inspections will focus on social workers’ direct practice with families by:

-

scrutinising and discussing the sample of children’s cases that reflect the scope of the inspection alongside discussions with practitioners working with the child or young person – this will include social workers and may also include other professionals and providers; these discussions do not have to be in person and in some cases will be by telephone during the notice period when practicable

-

when possible and appropriate, meeting with children, young people, care experienced young people, parents and carers, foster carers and adopters

-

shadowing staff in their day-to-day work

-

when possible and appropriate, observing practice in multi-agency/single-agency meetings (such as family group decision-making meetings) or, more likely, parts of meetings that relate to the protection of children and young people and reviews for children in care; inspectors will take opportunities for observing practice as they arise

Standard inspection arrangements

53. On a standard inspection, inspectors will gather evidence across the ILACS scope.

54. We usually give 5 working days’ notice of the inspection.

55. The inspection team for a standard inspection will usually be 4 social care inspectors, but for some smaller local authorities, we may send fewer inspectors. In addition, a social care regulatory inspector and an education inspector (usually a schools HMI) will carry out 2 days of fieldwork.

56. Inspection teams may include an additional inspector who will be shadowing the work of their colleagues. Any activity they carry out will be for their training and development or to evaluate the inspection framework and methodology. They will not carry out any inspection work independently or gather evidence that will inform the inspection judgements.

Week 1: notice period – off site

| Usual day of the week | Activities |

|---|---|

| Monday | Lead inspector phone call to DCS to announce the inspection Afternoon ‘set-up’ discussion between lead inspector and DCS (by telephone or in person) |

| Tuesday | Local authority shares child-level data and information about audits |

| Wednesday | Local authority shares performance and management information |

| Thursday and Friday | Full team off-site evaluation of evidence Telephone conference team meeting (including an Ofsted analytical officer) |

Week 2: fieldwork

| Usual day of the week | Activities |

|---|---|

| Monday | Lead inspector on site in the afternoon to meet DCS and set up the inspection Full team on site pm |

| Tuesday to Thursday | Full team on site gathering evidence |

| Friday | Full team off-site evaluation of evidence |

Week 3: fieldwork

| Usual day of the week | Activities |

|---|---|

| Monday | Full team on site from lunchtime gathering evidence |

| Tuesday to Thursday | Full team on site gathering evidence |

| Friday | Feeding back inspection findings Team off site by early afternoon |

Short inspection arrangements

57. On a short inspection, inspectors will gather evidence across the ILACS scope.

58. We usually give 5 working days’ notice of the inspection.

59. The inspection team for a short inspection will usually be 4 social care inspectors, but for some smaller local authorities, we may send fewer inspectors. In addition, a social care regulatory inspector and an education inspector (usually a schools HMI) will carry out 2 days of fieldwork. If we are making a judgement on ‘the experiences and progress of care leavers’ for the first time, the inspection team will usually include an additional social care HMI for 2 days during fieldwork. In exceptional cases, we may increase the size of the team if we need additional capacity to make sure we evaluate the local authority’s practice fairly and accurately.

60. Inspection teams may include an additional inspector who will be shadowing the work of their colleagues. Any activity they carry out will be for their training and development or to evaluate the inspection framework and methodology. They will not carry out any inspection work independently or gather evidence that will inform the inspection judgements.

Week 1: notice period – off site

| Usual day of the week | Activities |

|---|---|

| Monday | Lead inspector phone call to DCS to announce the inspection Afternoon ‘set-up’ discussion between lead inspector and DCS (by telephone or in person) |

| Tuesday | Local authority shares child-level data and information about audits |

| Wednesday | Local authority shares performance and management information |

| Thursday and Friday | Full team off-site evaluation of evidence Telephone conference team meeting (including an Ofsted analytical officer) |

Week 2: fieldwork

| Usual day of the week | Activities |

|---|---|

| Monday | Lead inspector on site in the afternoon to meet DCS and set up the inspection Full team on site pm gathering evidence |

| Tuesday to Thursday | Full team on site gathering evidence |

| Friday | Feeding back inspection findings Team off site by early afternoon |

61. A short inspection covers the ILACS scope, which is the same as a standard inspection. Judgements are made against the same evaluation criteria. However, it is not a 2-week inspection delivered in 1 week. Inspectors preparing for a short inspection will start with a mindset that ‘this is a good local authority’. This assumption is based on:

-

the previous inspection judgement

-

a focused visit or JTAI that has reinforced earlier findings

-

the quality of self-evaluation over the preceding years, which will have been explored during the annual engagement meetings

-

information held on the LAIS that supports a view of continuing strong performance

In a short inspection, inspectors will seek to answer 3 questions:

-

Has the quality and impact of practice been maintained?

-

Are there any areas where the quality and impact of practice have improved?

-

Are there any areas where the quality and impact of practice have deteriorated?

62. This approach enables the lead inspector to prioritise gathering primary evidence on the areas that need the greatest focus to make sure we evaluate the local authority’s practice fairly and accurately and also on the areas where we can add to the local authority’s understanding of their services. Inspectors will test the validity of the most recent self-evaluation by evaluating samples of casework. They may quickly close lines of enquiry about practice that needs to improve if the local authority has demonstrated that it has an accurate understanding of the issues and is taking appropriate action. If there are weaknesses in practice, we will include them in our report.

63. If inspectors are making a judgement on ‘the experiences and progress of care leavers’ for the first time at a short inspection, they will prioritise gathering evidence about this group of young people. To ensure that their judgement of this area is valid, inspectors are likely to look wider than the 3 questions set out above.

64. Evaluating individual children’s records that have already been audited by the local authority is another effective way to answer the 3 questions set out above. If the local authority’s evaluation of practice is in line with our evaluation, this will usually reduce the need for further primary evidence in that part of the inspection.

Further guidance on short and standard inspections

Inspecting against the scope and making judgements based on the evaluation criteria

65. Inspectors inspect across the areas included in the scope of the inspection and record their evidence under the 23 headings in the evaluation criteria. Each heading has several criteria that describe the features of a good service or good experiences and progress for children. Inspectors do not have to gather evidence against each individual criterion. The evaluation criteria help the inspection team make the correct judgement on the 4-point grading scheme.

The order of evidence-gathering in standard and short inspections

66. In previous inspection programmes, inspections have followed ‘the journey of the child’ – starting with the ‘front door’, then help and protection, children in care and, finally, leaving care. For standard and short inspections, this may not always be the best approach.

67. The factors that influence where the evidence-gathering will start are:

-

the geography of the local authority – for example, we may not always start in the main centre of population

-

previous known strengths and weaknesses (including the findings from a focused visit or the most recent annual engagement meeting); the lead may wish to inspect the stronger areas first to swiftly close down areas of enquiry, so that the inspection can focus on whether performance has improved in a previously weaker area

-

structure of services – where teams are located and across how many offices

-

logistical issues – where inspectors need to go at the start of fieldwork to sort practical issues (for example, to pick up security passes or gain access to IT systems)

68. An inspection might therefore start, for example, in the children in care service. In these circumstances, inspectors may gain helpful insights into the help and protection services through evaluating the experiences of those children who have recently become looked after.

69. In all cases, it will be for the lead inspector, with the quality assurance manager, to determine the approach. The lead inspector will provide the rationale to the DCS.

Off-site evaluation

70. Off-site evaluation and planning are important parts of all inspections. All inspectors will have access to LAIS. For standard and short inspections, the Ofsted analytical officer will coordinate the data, provide a pre-inspection analysis (PIA) and discuss priorities for the inspection with the inspection team. The analytical officer will ensure that the PIA contains the information the lead inspector and team will need to inform the inspection planning and on-site activity. This will summarise:

-

a contextual overview of the local authority

-

findings from relevant inspections (including previous focused visits) and regulatory activity, including some inspections carried out by other inspectorates

-

regional intelligence about the effectiveness and impact of the virtual school on the educational progress of children in care

-

findings from rapid reviews, child safeguarding practice reviews or management reviews

-

analysis of published statistics and national comparisons

-

evidence from whistleblowing or complaints to Ofsted

-

regional intelligence, including events of public concern, such as high-profile court cases or media issues

-

search and review of recently published documentation, such as the independent reviewing officer annual report

71. The PIA will include the regional SHMI’s analysis of the most recent self-evaluation and annual engagement meeting with the local authority.

72. Annex A lists the information that we request from the local authority at the start of the inspection.

73. The lead inspector will have time allocated, before fieldwork begins, to review the PIA, information on LAIS, intelligence about the local authority that has been gathered by the relevant Ofsted region, the information from Annex A and the views of children, young people, parents and staff expressed through the social care annual point-in-time surveys run by Ofsted. The lead inspector will use this information to:

-

ensure that the fieldwork is properly focused and used to the best effect in collecting first-hand evidence

-

decide which site(s) within the local authority to visit during inspection

-

identify initial lines of enquiry for the inspection

-

allocate information to the inspection team for them to analyse

74. Only initial lines of enquiry will be generated at this point. These will be few in number and themed around priority areas. The lead inspector will share verbally the lines of enquiry with the local authority at the beginning of the inspection. The lead inspector will explain to the local authority how these lines will be pursued and what, if any, specific information is required from them as a result.

75. We do not expect the local authority to produce documents and data in response to these initial lines of enquiry unless specifically requested by the lead inspector. During the inspection, additional requests for further documentation will be kept to an absolute minimum and agreed by the lead inspector.

76. All inspectors have time allocated to prepare for the inspection. All team inspectors must read the PIA and familiarise themselves with the relevant material and profile of the local authority area before arriving on site. The lead inspector is likely to identify other documents for inspectors to read before the on-site activity.

77. Inspectors must review the information in Annex A provided by the local authority. The lead inspector may decide that some documents must be read by all team members; others will be read by only one inspector and then summarised for the team. Some documents may be used as reference material and read only when required. The lead inspector will ensure that key points of analysis are collated and disseminated to the inspection team to inform the inspection.

Notifying the local authority and requesting information

79. As part of this telephone call, the lead inspector will also arrange to meet with the DCS or the most senior manager available at the earliest opportunity when they arrive on site.

80. Immediately following the telephone call to the local authority, the lead inspector will email the DCS to confirm the start of the inspection and ask them to share the information set out in Annex A. Annex A lists information we think the local authority will already maintain to inform its oversight and management of its service. On this basis, we do not consider that the information we request is unreasonable. The lead inspector will offer the DCS an opportunity for a conversation later the same day to give the DCS time to bring together the relevant staff. This conversation will usually be by phone, but the lead inspector may meet with the DCS in person if it is practical to do so. This conversation will help the lead inspector and local senior leaders to establish a constructive and professional relationship and give them a shared understanding of the starting point of the inspection.

81. If the DCS is not available, the lead inspector will speak with or email the most senior manager available and ask them to notify the DCS or, if the DCS is not available, the chief executive. The non-availability of the DCS or a senior manager will not delay the start of the inspection.

82. The lead inspector will ask the DCS to identify a link support person for the inspection. It is important that the link person has ready access to the DCS and senior leaders and sufficient authority to be able to respond to the lead inspector’s requests.

83. In the week before inspectors are on site, the lead inspector will work with the link person and/or DCS to prepare for the on-site activity. The lead inspector will:

-

answer questions about the scope of the inspection

-

outline the format and methodology of the inspection, which will focus almost exclusively on practice with children and families. Meetings will be kept to a minimum, will only look into matters arising from case evaluations and will only take place at the lead inspector’s request.

-

discuss how inspectors will directly consider the experiences of children, young people and families as an integral part of the inspection. When opportunities arise during the fieldwork to speak with or observe contact with children, young people and families, the local social work staff will be asked to obtain their agreement to observe any meetings and speak to inspectors

-

agree practical arrangements, such as work space, access to files and information technology systems, and any staff support required to access these files and systems

-

agree arrangements to meet with the DCS and his/her senior leadership team for regular keep-in-touch (KIT) meetings and the feedback meeting

-

provide contact details for the lead inspector, inspection team members and the allocated SHMI responsible for quality assurance

-

provide information for affected/relevant staff, such as copies of the summary of the framework explaining the purpose of the inspection

-

gain an understanding of how the local area services are structured, as well as any issues specific to the site(s) being inspected

-

provide an opportunity for the local authority representatives to explain the local authority’s local context, key strengths and challenges

-

clarify whether there are any serious incidents that are awaiting notification or have been notified to Ofsted recently; this should include significant and current investigations (including police investigations), national or local learning reviews and local issues of high media interest

-

ask whether any steps need to be taken to ensure the well-being of local authority staff, including senior leaders, during the inspection. The lead inspector will ask who to contact if the inspection team need to pass on any concerns about someone’s well-being

-

provide the local authority with an opportunity to raise any issues or concerns about the inspection and explain how the local authority can raise any matters during the inspection

-

provide the local authority with an opportunity to request any adaptations to the inspection process due to a protected characteristic, or any reasonable adjustments due to a disability

84. After the local authority shares the information listed in Annex A, an Ofsted analytical officer may contact a local authority analyst to clarify any issues with the composition or content of the local authority’s data.

85. The lead inspector may also ask for a phone conversation with the lead member for children’s services and/or the local authority chief executive.

Fieldwork

86. The lead inspector and 3 inspectors will arrive on site on Monday afternoon. All inspectors will show their inspector identity badges. They do not need to carry copies of their Disclosure and Barring Service checks.

87. When the lead inspector arrives on site, they will meet with the DCS and/or the most senior manager available. At this meeting, the lead inspector will review the matters and arrangements discussed in the previous week. The lead inspector will answer any remaining questions and ask local leaders to confirm that the practical arrangements inspectors requested are in place.

88. When planning the on-site aspect of inspection, the lead inspector should ensure that:

-

support is provided to facilitate communication with children, young people, care experienced young people, carers and parents who require additional support

-

the plan allows realistic travel time for inspectors between activities

-

the plan allows sufficient time and flexibility for inspectors to pursue lines of enquiry

-

staff are given the opportunity to provide their evidence separately to those who manage them

-

if the need for any meeting arises as a result of evaluating children’s experiences, the lead inspector asks for this as soon as the need becomes apparent; these meetings may be held by telephone as well as in person

-

inspectors have time to reflect on, record and analyse evidence, individually and as a team

89. The schedule for the inspection will develop throughout the inspection in response to issues emerging from evaluating children and young people’s experiences. The lead inspector has overall responsibility for the schedule. On-site inspection activity will not normally continue after 6pm on any fieldwork day.

Evaluating the effectiveness of the recruitment, assessment, training and support for foster and adoptive carers

90. During a standard or short inspection, the social care regulatory inspector (SCRI) will carry out 2 days of fieldwork. For a standard inspection, these days will usually be in the second week of fieldwork. This work may, on occasion, be carried out by an HMI.

91. The SCRI will focus on evaluating the effectiveness of the recruitment, assessment, training and support for foster and adoptive carers. They will evaluate the experiences of up to 3 foster carer households and up to 3 adopter households. The lead inspector will include the following in the households they select for the SCRI to review:

-

a recently assessed foster carer

-

a recently assessed adopter

-

a family that has accessed or requested adoption support (if this has happened in the 6 months before the inspection)

-

an early permanence/foster to adopt placement (if the local authority is providing these placements)

92. The lead inspector will ask the local authority to provide lists of foster carers and adopters at the start of the inspection (see Annex A). They will use these lists to select the households mentioned above and ask the local authority to share:

-

their most recent assessments of these foster carers and adopters (where produced within the past 12 months) along with associated panel minutes and record of decision

-

their most recent review of approval (for those foster carers approved over 12 months) along with associated panel minutes and record of decision

93. In addition to reviewing these records, the SCRI will speak to:

-

foster carers and adopters

-

staff and managers who support foster and adoptive carers

-

the foster and adoption panel chairs

-

the head of the foster carer forum

94. Conversations with carers and staff will usually be by telephone. The lead inspector will ask the local authority to help arrange these calls.

95. The SCRI will evaluate the effectiveness of the recruitment, assessment and training of prospective foster and adoptive carers against the criteria in this framework that cover arrangements to secure timely permanence for all children.

96. Local authorities will usually be part of a regional adoption agency (RAA), where groups of local authorities and voluntary adoption agencies (VAAs) work together to improve their adoption services. In these circumstances, it remains the responsibility of each local authority to demonstrate how the arrangements comply with their statutory responsibilities and meet the needs of local children.

97. If a local authority manages its own recruitment, assessment, training and support for adopters, inspectors will evaluate the effectiveness of these arrangements. If these are managed by an RAA, inspectors will look at the local authority’s arrangements to assure itself that the RAA meets the needs of local children. See regional adoption agencies and ILACS for more information.

98. A local authority may be part of a regional foster carer recruitment hub. These hubs centralise the recruitment of foster carers for a group of local authorities, with recruitment managed by 1 ‘lead’ local authority. Where this is the case, each local authority retains their responsibility for ensuring that the activity of the hub meets the recruitment needs of the local authority and of local children. If a local authority is part of a hub, inspectors will consider the local authority’s oversight of these arrangements to ensure that they are meeting their own sufficiency duty. See fostering recruitment hubs and ILACS for more information.

Evaluating the educational progress of children in care and care leavers

99. Each standard and short inspection will include a schools HMI. The schools HMI will carry out two days of fieldwork. For a standard inspection, these days will usually be in the second week of fieldwork.

100. Working off site, they will evaluate data and information to provide analysis and lines of enquiry. They may contact the virtual school headteacher for a conversation by phone.

101. During fieldwork, they will usually be on site and will interview the virtual school headteacher and, if appropriate, the local authority data personnel. They will evaluate some case studies of specific children’s and care leavers’ progress, including disabled care leavers. They may contact specific schools by phone for further information. They will evaluate how leaders value the expertise of the virtual school headteacher and, where needed, help them to champion better educational outcomes for children and young people.

102. The schools HMI will analyse data and information about:

-

the educational progress of children in care and care leavers

-

elective home-educated children

-

children missing education

Making judgements at standard or short inspections

103. Inspectors will make the following graded judgements:

-

overall effectiveness

-

the experiences and progress of children in need of help and protection

-

the experiences and progress of children in care

-

the experiences and progress of care leavers

-

the impact of leaders on social work practice with children and families

104. Inspectors will make their graded judgements on a 4-point scale:

-

outstanding

-

good

-

requires improvement to be good

-

inadequate

105. Inspectors will evaluate the experiences of children, young people and families and the services they receive using the evaluation criteria as a benchmark. Inspectors will use professional judgement to determine the weight and significance of their findings. A judgement of good will be made if the inspection team concludes that the evidence overall sits most appropriately with a finding of good. This is what we describe as ‘best fit’.

106. The overall effectiveness judgement is derived from findings in each of the 4 other judgement areas. Inspectors will use both evidence and their professional judgement to award the overall effectiveness grade.

107. If inspectors find widespread or serious failure resulting in harm, continued risk of harm or failure to safeguard the welfare of children and young people, including care leavers, in either the arrangements to protect or care for them, they will always give an overall effectiveness judgement of inadequate.

108. It is possible for the impact of leaders to be judged good or requires improvement to be good even if any of the other judgements given is inadequate. Inspectors will make this judgement if leaders and managers show sufficient understanding of the widespread or serious failure and have taken effective action to prioritise, challenge and make sustained improvement to services. Inspectors will acknowledge this in the report. The overall judgement will be inadequate because children’s experiences have the most weight in determining this judgement.

109. If, at the end of fieldwork, the local authority’s children’s services are judged inadequate, inspectors will follow the section in this guidance on monitoring inadequate local authorities.

Focused visits

110. Focused visits evaluate an aspect of service, a theme or the experiences of a cohort of children. HMI carry out these visits under section 136(2) of the EIA. HMCI has the power to carry out ILACS functions as listed in section 135 of the EIA.

Focused visit arrangements

111. We carry out focused visits between standard and short inspections. We usually give 5 working days’ notice of the visit. The arrangements for notifying the local authority of a focused visit are the same as those for inspections. However, the lead inspector will adjust the arrangements so that they are proportionate to the scope of the visit. See notifying the local authority and requesting information.

112. Usually, 2 inspectors will carry out 2 days of fieldwork contained within one week. Focused visits will include some or all of the same inspection activity as a standard or short inspection.

113. The table below shows an example timeline for a focused visit that takes place on a Tuesday and Wednesday. If a focused visit takes place on other days of the week, we will move the other activities accordingly. The lead inspector will provide the DCS with a specific timeline when they notify them of the visit.

Week 1: notice period – off site

| Example day of the week | Activities |

|---|---|

| Monday | Lead inspector off-site evaluation of evidence |

| Tuesday | Lead inspector phone call to DCS to announce the focused visit Afternoon ‘set-up’ telephone conference – lead inspector and DCS |

| Wednesday | Local authority shares child-level data, information about audits and performance and management information |

| Thursday and Friday | Full team off-site evaluation of evidence Telephone conference team meeting |

Week 2: fieldwork

| Example day of the week | Activities |

|---|---|

| Monday | Off-site evaluation of evidence |

| Tuesday | Full team on site gathering evidence |

| Wednesday | Full team on site gathering evidence and providing feedback |

Focused visit topics

114. A focused visit will look at one or more aspects of the service, themes or cohorts of children. Inspections will use evaluation criteria from this framework or from our JTAIs.

115. We will make the final decision about the focused visit topic to be covered. The decision will be based on one or more of the following:

-

if a specific area of service has been identified in a local authority as an example of good or outstanding practice

-

if a specific area of service has been identified as one that needs to improve or an area where themes, trends and issues are identified

-

if an agreement between us and the local authority has been made that a specific focus will support that local authority’s improvement journey

-

if we decide to carry out a short programme in a particular area of service, which will then lead to a thematic overview

116. Each focused visit will cover part of the scope of standard and short inspections.

117. The scope for individual focused visits will usually be narrowed within each topic. Leadership is a feature of all focused visits, principally through the lens of the impact of leaders on practice with children and families.

A list of topics and what they may include is set out below.

Topic: the front door

The front door is the service that receives contacts and referrals (single- or multi-agency), where decisions are made about:

-

child protection enquiries – such as strategy discussions or section 47 enquiries

-

emergency action – liaison with police to use powers of protection or applications for an emergency protection order

-

child in need assessments

-

decisions to accommodate

-

step-up from and step-down to early help

-

no further action/signposting

Topic: children in need or subject to a protection plan

This may cover:

-

thresholds

-

step-up/step-down between children in need and child protection

-

children on the edge of care

-

children subject to a letter before proceedings and the quality and impact of pre-proceedings interventions, such as family group decision-making meetings

-

children in need at risk of family breakdown

-

the quality of decisions about entering care

-

protection of disabled children

Topic: protection of vulnerable children from extra-familial risk

This may cover:

-

child sexual/criminal exploitation

-

missing from home, care or education

-

risks associated with gangs

-

risks associated with radicalisation

-

trafficking and modern slavery

Topic: children in care

This may cover:

-

quality of matching, placement and decision-making for children in care

-

the experiences and progress of disabled children in care

-

the experiences and progress of children living in supported accommodation

-

the experiences and progress of children living in unregistered provision

Topic: planning and achieving permanence

This may cover:

-

return to birth family

-

connected and kinship (family and friends) care

-

adoption

-

long-term foster or residential care

-

special guardianship

Topic: care leavers

These visits may focus on all care leavers or specific age groups (for example, those aged 16 and 17 or aged 18 to 25). These visits will cover some but not all the following aspects:

-

quality and suitability of accommodation

-

employment, education and training

-

support into adulthood

-

staying close and in touch

-

care leavers with specific needs (for example, unaccompanied asylum seekers, young parents or those who have had contact with the criminal justice system)

-

disabled care leavers and those with specific physical or mental health needs, including those who misuse alcohol or drugs

-

care leavers at risk of specific types of harm, such criminal or sexual exploitation and domestic abuse

Topic: placement decision-making for older children

This may cover:

-

children, including children who meet the definition of ‘eligible’[footnote 1], living in or with a plan for living in supported accommodation [footnote 2]

-

children aged 16 or 17 years living in unregistered provision (including on an emergency basis)

-

children under 16 years old living in unregistered provision (including on an emergency basis)

-

placement sufficiency, including fostering matching practice

-

children placed in unregistered provision when subject to an order under the court’s inherent jurisdiction to deprive them of their liberty

-

children placed in, or waiting for, a secure children’s home on welfare grounds (s25)

-

children where the plan is for them to leave a secure children’s home

-

arrangements for unaccompanied asylum-seeking children

-

how local authorities are working in partnership with others to meet their sufficiency duty to older children

Findings at focused visits

In each of these focused visits, inspectors will evaluate the effectiveness of:

-

performance management

-

management oversight

-

supervision

-

quality assurance

-

continuous professional development of the workforce

118. Inspectors will not make graded judgements at the outcome of a focused visit. Nor will they indicate what the grade may have been if the visit had been a short or standard inspection. The outcome will be findings about strengths and areas for improvement, reported in a published letter.

119. If inspectors find serious weaknesses, they will identify areas for priority action. An area for priority action is either:

-

an area of serious weakness that is placing children at risk of inadequate protection and significant harm

-

an unnecessary delay in identifying permanent solutions for children in care that results in their welfare not being safeguarded and promoted

-

a failure to keep in touch with care leavers, or provide them with support and services, that results in their welfare not being safeguarded and promoted

120. Priority actions may result from particular or localised failings to protect or care for children or care leavers as well as from systemic failures or deficits. Some examples of areas for priority action are:

-

unrecognised or unallocated children’s cases and/or significant delays in addressing child protection concerns or safeguarding the welfare of a child in care

-

systemic failure or significant weakness in practice that expose children or care leavers to significant risk of harm or fail to safeguard and promote their welfare

-

a significant shortfall in capacity (frontline staffing numbers, qualifications and expertise) or deficit in management oversight and supervision that impacts adversely on delivery of help, protection or care to children or care leavers

-

significant delays in the allocation or assessment of a large number of children in need cases that expose those children to potential and unquantified risk of harm

121. Inspectors will use findings from focused visits when planning their next short or standard inspection. The evidence from a focused visit will not be used as primary evidence but may enable inspectors to target their evidence-gathering more effectively.

Monitoring inadequate local authorities

Notifying the local authority of monitoring activity

122. If local authority children’s services are judged inadequate, we will carry out monitoring activity that includes an action planning visit, monitoring visits and a reinspection. The lead inspector will inform the DCS of this at the feedback meeting for the inspection where the inadequate judgement is given.

123. If a local authority is not prepared to agree the programme of monitoring visits, the Secretary of State for Education is likely to intervene and direct us to carry out these visits. Section 118(2) of the Education and Inspections Act 2006 enables the Secretary of State for Education to direct the Chief Inspector to carry out an inspection of a local authority’s children’s services.

124. These activities may also take place if inspectors identify areas for priority action at a JTAI that suggest that children are at risk of significant harm.

125. Monitoring visits will focus on where improvement is needed the most. Inspectors will monitor and report on the local authority’s progress since the inspection. Inspectors will also check that performance in other areas has not declined since the inspection. If new concerns emerge, inspectors are likely to look at these on the monitoring visits.

The table below sets out an illustrative timetable for activities after an inadequate judgement. Each step is set out in more detail after the table.

| Activity | When the activity happens |

|---|---|

| Action planning visit between Ofsted and the local authority | 30 working days after we publish the inspection report |

| Local authority shares action plan | 70 working days after we publish the inspection report |

| First monitoring visit | 6 months after we publish the inspection report |

| Second and subsequent monitoring visits | Timetable to be agreed between Ofsted and the local authority. Ofsted will confirm the calendar month of each visit in advance. |

Action planning visit following an inadequate judgement

126. At the inspection feedback meeting, the lead inspector will ask the DCS to arrange an action planning visit. The visit should take place about 30 working days after the local authority has received its inspection report.

The purpose of the visit is to:

-

clarify the roles, responsibilities and activities of Ofsted and the Department for Education (DfE)

-

help the local authority and its partners understand the inspection findings so that they can develop an action plan

-

set out the implications for statutory partners, including those included in the local strategic safeguarding arrangements

-

discuss the draft action plan (if available)

-

confirm the calendar month of the first monitoring visit and establish the pattern of future monitoring activity

-

agree the focus of the first monitoring visit and (if possible) any subsequent monitoring visits

127. Once the local authority has received its inspection report, the regional director will write to the DCS confirming the action planning visit. They will copy this letter to the DfE inspections and interventions team.

128. A member of the inspection team, usually the lead inspector, and a SHMI based in the local authority’s region will attend the visit. The role of the inspector and SHMI is to help the local authority understand the findings from the inspection.

129. The DCS will decide who else attends the action planning visit. The DCS may wish to discuss this with the lead inspector to ensure that attendees are appropriate to the findings in the report. The attendees will usually include senior managers of the local authority children’s services and other key partners. The visit is concerned with the operational work of children’s services professionals, so elected councillors will not normally attend.

130. The SHMI and lead inspector will discuss the agenda for the action planning visit with the DCS before the event. The lead inspector will circulate the final agenda 5 working days before the visit.

131. If the local authority has a draft of its action plan, the DCS should share this with the lead inspector before the action planning visit. Early drafts of action plans are accepted as a ‘work in progress’ and will not be formally reviewed by the inspector.

132. The lead inspector will record the outcome of the discussions. The SHMI will send this to the DCS, regional director and the national director, social care.

Reviewing the local authority action plan

133. The lead inspector will review the action plan as soon as possible after receiving it. We are not responsible for ‘signing off’ or endorsing the action plan – this is the responsibility of the DCS. Our role is to advise the DCS about whether the action plan reflects the findings in the inspection report. Our regional director will write to the DCS confirming whether the action plan reflects the inspection findings.

134. If the regional director thinks that the action plan does not respond to the findings set out in the inspection report, the lead inspector and/or SHMI will discuss this with the DCS. If we and the local authority disagree on this matter, the regional director will write to the DCS setting out the area(s) of difference and the reasons.

135. The lead inspector will share the letter they send to the DCS with the DfE inspections and interventions unit. If we and the local authority differ in our view of the action plan, we will ask the Secretary of State for Education to consider what action (if any) they want the DfE to take.

136. With the agreement of the DCS, the inspector and/or SHMI may attend the local authority’s improvement board or other related meetings, for example with DfE officials. Our inspectors will attend as observers.

Arrangements for monitoring visits

137. At the action planning visit, the SHMI, lead inspector and DCS will agree arrangements for monitoring visits. The following guidelines will usually apply.

-

The first monitoring visit will be within 3 months of the submission deadline for the local authority’s action plan (which is about 6 months after publication of the inspection report).

-

We will carry out up to 4 monitoring visits a year.

-

If the local authority in the local area is also receiving monitoring visits under the area SEND inspection framework, there will usually be no more than 3 monitoring visits across both frameworks within a 12-month period.

-

We will carry out between 4 and 6 monitoring visits before a reinspection.

-

The monitoring visits may not be equally spaced throughout the year.

-

The lead inspector will confirm the calendar month that a visit will take place in advance.

After we have completed these monitoring visits, we will either:

-

adopt the ILACS process for self-evaluation and annual engagement before carrying out a reinspection

-

consider whether further monitoring would continue to add value in light of further plans for improvement

138. Usually, 2 inspectors will carry out each visit. Each visit will usually last for 2 days. Whenever possible, the same inspector will lead all the monitoring visits in the same local authority.

139. The table below shows an example timeline for a monitoring visit that takes place on a Tuesday and Wednesday. If a monitoring visit takes place on other days of the week, we will move the other activities accordingly. The lead inspector will provide the DCS with a specific timeline when they notify them of the visit.

Timescale: before the visit

| Timescale | Example day of the week | Activities |

|---|---|---|

| 10 days before the visit | Tuesday | Lead inspector requests child-level data |

| 9 days before the visit | Wednesday | Local authority provides data, indicating which cases they have audited |

| 8 days before the visit | Thursday | Lead inspector notifies local authority of specific audited cases that the local authority should share |

| The week before the visit | Wednesday | Local authority shares audited cases Local authority shares the information it uses to manage services for children and young people |

| The week before the visit | Thursday and Friday | Full team off-site evaluation of evidence Telephone conference team meeting |

Timescale: fieldwork

| Example day of the week | Activities |

|---|---|

| Monday | Off-site evaluation of evidence |

| Tuesday | Full team on site gathering evidence |

| Wednesday | Full team on site gathering evidence and providing feedback |

Before a monitoring visit

140. Two weeks before the visit, the lead inspector will ask the local authority to provide up-to-date child-level data. When providing the data, the local authority should indicate any cases that it has audited since the last monitoring visit.

141. The inspector may ask the local authority to audit cases. Usually, the inspector will request information about up to 6 cases that have already been audited by the local authority. The local authority should share the completed audits at least 3 working days before the monitoring visit.

142. We will only request information that is necessary to inform that monitoring visit. Requests will be based on the information in Annex A.

143. Inspectors will provide details for accessing a secure online site that the local authority can use to share this information.

Fieldwork for monitoring visits

144. The lead inspector and DCS will agree a timetable for the on-site activity. On-site activity will usually consist of evaluating the experience of up to 6 children and young people. Inspectors will evaluate the cases audited by the local authority to see how effective the local authority’s auditing systems are.

145. To triangulate their findings, inspectors will look at a sample of other cases. Any sampling activity will be proportionate to the practice that inspectors are evaluating. Inspectors will usually only sample cases from the previous 3 months.

146. If the inspector identifies a cause for concern about the help, protection or care given to a child or children, they must bring it to the DCS’s attention.

147. Inspectors will record the evidence collected and their conclusions during each monitoring visit. Inspectors must record the case numbers of tracked and sampled cases so that these can be cross-referenced in future visits.

148. At the end of each visit, the lead inspector will feed back a summary of the inspection findings to the local authority. It is for the local authority to decide who will attend this meeting. If the Secretary of State for Education has appointed a children’s services commissioner, the local authority may invite the commissioner to attend the feedback as an observer. The Ofsted regional director and/or quality assurance manager may be present for the feedback. If the authority and inspectors disagree about the findings, this must be recorded.

149. The lead inspector and the local authority will discuss the areas to consider at the next monitoring visit. If the calendar month of the next monitoring visit is known, the lead inspector will confirm this and whether the local authority will need to audit any cases.

Roles and expectations of inspectors

The things inspectors should do when working as part of an inspection team.

150. In all inspections, all inspectors work collaboratively on all aspects of the scope to ensure that evidence is analysed as a group activity. In short and standard inspections, all inspectors usually gather evidence and evaluate the same cohort of children’s experiences and progress at the same time. This is central to the effectiveness of a small team.

The lead inspector will:

-

coordinate the inspection between the team and with the local authority area leaders

-

challenge, support and give advice to the team and quality assure the team’s work

-

develop lines of enquiry alongside the team

-

prioritise inspection activity according to lines of enquiry

-

consider any health and safety risks for individual inspectors

The team inspector will:

-

work across judgement areas to provide challenge and scrutiny to the work of other inspectors throughout the inspection and in the final judgement meeting

-

present succinct analysis of the main findings based on reliable evidence

-

quality assure their own and other inspectors’ work during inspections

Inspection team meetings

151. Team meetings are important to ensure that the team covers the scope of the inspection. Inspectors should come together at the beginning, middle and end of each fieldwork day to:

-

share and triangulate their evidence and analysis

-

agree and record shared findings in their joint evidence record

-

develop and close down lines of enquiry as a team

-

build up an evidence-based view of the quality and impact of practice and leadership within the local authority area

-

keep the lead inspector fully aware of any key developments

-

enable the lead inspector to coordinate the inspection effectively

152. The team will meet for an extended period on the penultimate day on site to discuss findings, agree provisional judgements and identify areas for improvement.

Inspection methodology

The things that inspectors will do to gather and evaluate evidence and report their findings.

Inspection activity and gathering evidence

153. Almost all inspection evidence will be gathered by looking at individual children and young people’s experiences. This will be largely through meeting with practitioners to understand the nature and impact of their work with children and families, including scrutinising electronic records. Inspectors will work with leaders and staff constructively and will act with professionalism, courtesy, empathy and respect.

154. We take into account individual children’s starting points and circumstances during inspections. We recognise that even slight progress in a particular aspect of their lives may represent a significant improvement for some children. We also recognise that for some children, because of their experiences of trauma, abuse or neglect, progress is not always straightforward. Progress in one area may result in deterioration in another as they work through the impact of their past experiences.

155. Evaluating individual children’s records that have already been audited by the local authority is an effective way for inspectors to understand the local authority and target their evidence-gathering. If the local authority’s evaluation of practice is in line with our evaluation, this will usually reduce the need for further primary evidence in that part of the inspection.

156. When evaluating the experiences and progress of individual children, inspectors will consider the extent to which the local authority complies with the relevant legal duties as set out in the Equality Act 2010, including, when relevant, the Public Sector Equality Duty and the Human Rights Act 1998.

157. When evaluating individual children’s experiences, inspectors will not grade individual pieces of work.

158. If statutory functions have been delegated, the inspectors will evaluate the experiences of children and young people in the same way as they do in areas where functions have not been delegated. For further information on delegated functions, see the section on alternative delivery models.

159. When inspectors select the children and young people whose experiences they will evaluate, they will take into account the factors set out below:

-

age, sex, disability and ethnicity

-

children at risk of harm from physical, emotional and sexual abuse and neglect. Inspectors will also want to identify those children and young people who the local authority is concerned may be vulnerable to sexual and other forms of exploitation and those children and young people who have been missing from care, home and education. These children must be part of the cohort of children whose experiences inspectors evaluate

-

educational achievement and attendance

-

type of placement, including out-of-area placements, kinship care or ‘connected person’ arrangements and children placed at home and subject to a care order (Regulation 24(3) Care Planning, Placement and Care Review (England) Regulations 2010)

-

at least one child from a large sibling group

-