30 years of investigating Serious Incidents – the AAIB’s perspective

Published 17 March 2025

Note: The content of this article was first published in the AAIB Annual Safety Review 2023 publication on 28 March 2024.

1. Background

The International Standards and Recommended Practices for air accident investigation were first adopted in March 1951 by ICAO and were designated Annex 13 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation. In 1992 a major amendment was made to ICAO Annex 13. Importantly it introduced requirements for notification and investigation of Serious Incidents to aircraft and the title of Annex 13 changed to ‘Aircraft Accident and Incident Investigation’; thus started a new era in which ICAO States investigated Serious Incidents as well as Accidents.

Annex 13[footnote 1] is now in its twelfth edition. The ICAO definition of an Accident is an occurrence associated with the operation of an aircraft in which:

- a person is fatally or seriously injured,

- the aircraft sustains damage or structural failure that adversely affects the operation of the aircraft or requires a major repair,

- the aircraft is missing or completely inaccessible.

An Incident is an occurrence, other than an accident, associated with the operation of an aircraft which affects or could affect the safety of operation.

A Serious Incident is: ‘An incident involving circumstances indicating that there was a high probability of an accident…’ and ‘the difference between an Accident and a Serious Incident lies only in the result’.

The AAIB in its various forms has been investigating air accidents for over 100 years, and has been a key player in the evolution of the international standards for air accident investigation since the post World War II boom in civil aviation transport. The AAIB commissioned a simple computerised accident database in the late 1990s, and this was replaced by a more comprehensive system in 2005. Whilst the AAIB has been investigating Serious Incidents and some Incidents since 1992, this article considers the period from mid-2003 to mid-2023 to assess the importance of the investigation of Serious Incidents and Incidents, which represents a period for which comprehensive data exists.

2. Accidents and Serious Incidents – the last twenty years

Table 1 contains a summary of all the field investigations[footnote 2] undertaken over a 20 year period from mid-2003 to mid-2023. It is broken down into Commercial Air Transport, plus a relatively small number of Emergency Services operations, and General Aviation and Sport operations. There are a small number of UAS cases that have been excluded from this dataset.

| AAIB Field Investigations | Number of Accidents Investigated | Number of Accidents with Safety Recommendations | Number of Incidents and Serious Incidents Investigated | Number of Incidents and Serious Incidents investigated with Safety Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial Air Transport + Emergency Services Ops | 126 | 65 | 279 | 116 |

| General Aviation and Sport | 512 | 174 | 51 | 19 |

| Total | 638 | 239 | 330 | 135 |

Table 1: AAIB Safety Recommendations 2023-2023

During this 20-year period the total number of Accidents, Incidents and Serious Incidents investigated is 968 which equates to an average of around 48 field investigations per year. Of these there were 638 Accidents and 330 Incidents and Serious Incidents, so around a third of field investigations were for Incidents and Serious Incidents.

The priority for AAIB, in keeping with the UK’s State Safety Programme[footnote 3], is Commercial Air Transport safety. Looking at just Commercial Air Transport, plus the small number of investigations into events involving Emergency Service operations, then the situation is very different. AAIB have investigated 126 such accidents but 279, approximately twice the number, for Incidents and Serious Incidents. Importantly, the investigations from which Safety Recommendations are made shows a similar trend with twice the number (116 compared with 65) of investigations into Incidents and Serious Incident having one of more Safety Recommendations made compared with investigations into Accidents.

3. Examples of AAIB investigations into Commercial Air Transport Incidents and Serious Incidents

3.1 G-VATL A340-600 incident in 2007

The AAIB investigated an Incident in 2007 in which, without warning the No 1 engine lost power and ran down on an Airbus A340-600 in cruise. Initially the pilots suspected a leak had emptied the contents of the fuel tank feeding the No 1 engine but a few minutes later, the No 4 engine started to lose power. Still with no fuel warnings the crew opened the fuel cross-feed valves and the No 4 engine recovered to normal operation. The pilots then observed that the fuel tank feeding the No 4 engine was also indicating empty. However, the total fuel on board was as expected for the flight so they realised that they had a fuel management problem. Fuel had not been transferring from the centre, trim and outer wing tanks to the inner wing tanks as expected so the pilots attempted to transfer fuel manually. Although transfer was partially achieved, the expected indications of fuel transfer in progress were not displayed so the commander decided to divert to Amsterdam (Schiphol) Airport where the aircraft landed safely on three engines.

The investigation determined several causal factors and the resultant six Safety Recommendations led to a redesign of the A340 and A380 fuel systems, and a change in the Certification requirements for large aircraft[footnote 4] requiring independent low fuel warning indications. This is an excellent example of an event that did not receive widespread media coverage but resulted in very significant safety lessons being learned.

3.2 ET-AOP Boeing 787 Incident in 2013

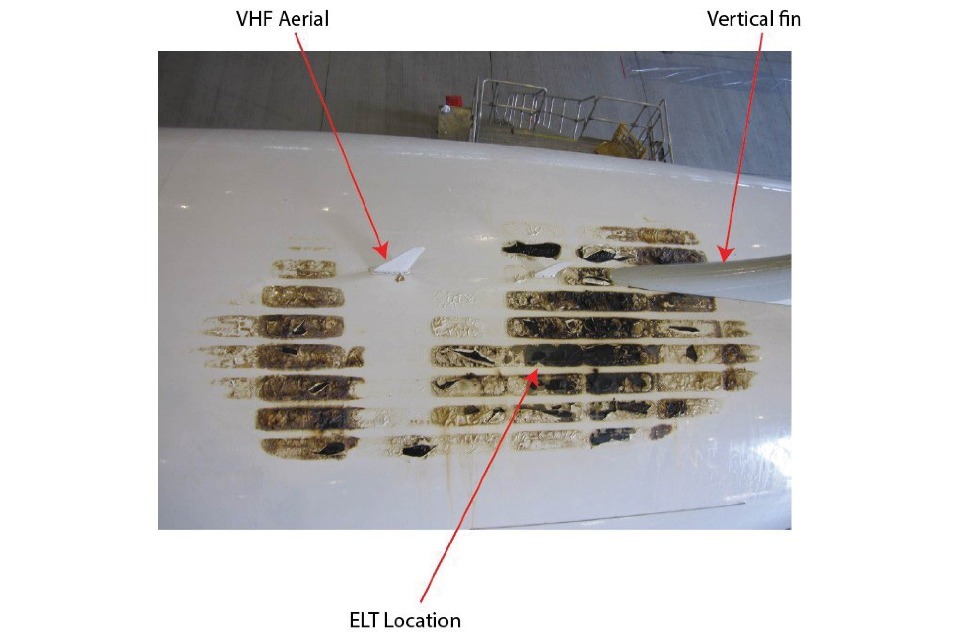

In July 2013 a ground fire started in a parked and unoccupied Boeing 787-8 at London Heathrow Airport (Figure 1). The circumstances surrounding the occurrence did not fall within the definitions of an Accident or Serious Incident as defined in ICAO Annex 13, however, the Chief Inspector, exercised his powers under the Civil Aviation (Investigation of Air Accidents and Incidents) Regulations 1996, initiated an investigation, treating the occurrence as a Serious Incident and invoking the protocols of ICAO Annex 13 with regard to the participation of other interested States. An investigation was commenced immediately and a team of AAIB Inspectors was deployed.

Figure 1: ET-AOP on a remote stand at Heathrow during the incident

The aircraft suffered extensive heat damage in the upper portion of the aircraft’s rear fuselage, in an area coincident with the location of the Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT) shown in Figure 2. The absence of any other aircraft systems in this area containing stored energy capable of initiating a fire, together with evidence from forensic examination of the ELT, led the investigation to conclude that the fire originated within the ELT.

Figure 2: ET-AOP heat damage to the upper fuselage

The ground fire on ET-AOP was initiated by the uncontrolled release of stored energy from the lithium-metal battery in the ELT. It was identified early in the investigation that ELT battery wires, crossed and trapped under the battery compartment cover-plate, probably created a short-circuit current path which could allow a rapid, uncontrolled discharge of the battery. Root Cause testing performed by the aircraft and ELT manufacturers confirmed this latent fault as the most likely cause of the ELT battery fire, most probably in combination with the early depletion of a single cell.

Fourteen Safety Recommendations were made during the course of the investigation. In addition, the ELT manufacturer carried out several safety actions and is redesigning the ELT unit taking into account the findings of this investigation. Boeing and the FAA have also undertaken safety actions.

3.3 C-FWGH Boeing 737-800 at Belfast in 2017

In July 2017 the AAIB investigated a Serious Incident in which a Boeing 737-800 took off from Belfast International Airport with insufficient power to meet regulated performance requirements. The aircraft struck a supplementary runway approach light, which was 36 cm tall and 29 m beyond the end of the takeoff runway. Figure 3 contains an image of the damage which at first sight does not convey the seriousness of the event.

Figure 3: Damage to supplementary runway light 29 m from the end of the runway

An outside air temperature (OAT) of -52°C had been entered into the Flight Management Computer (FMC) instead of the actual OAT of 16°C. This, together with the correctly calculated assumed temperature thrust reduction of 48°C, meant the aircraft engines were delivering only 60% of their maximum rated thrust. The low acceleration of the aircraft was not recognised by the crew until the aircraft was rapidly approaching the end of the runway. The aircraft rotated at the extreme end of the runway and climbed away at a very low rate. The crew did not apply full thrust until the aircraft was approximately 4 km from the end of the runway, at around 800 ft aal.

There was no damage to the aircraft, which continued its flight to Corfu, Greece without further incident. However, it was only the benign nature of the runway clearway and terrain elevation beyond, and the lack of obstacles in the climb-out path which allowed the aircraft to climb away without further collision after it struck the runway light. Had an engine failed at a critical moment during the takeoff, the consequences could have been catastrophic.

The investigation determined several causal and contributory factors for this Serious Incident, including the lack of capability in the FMC to alert the crew of the incorrect OAT and that the Electronic Flight Bags (EFB) did not display N1[footnote 5] on their performance application which meant that the crew could not verify the FMC-calculated N1 against an independently calculated value.

The AAIB made six Safety Recommendations, which resulted in significant safety action.

4. Benefits and challenges

The AAIB has found that in-depth investigation of a Serious Incident may bring considerable benefits for aviation safety.

- By definition, a Serious Incident presented a high risk of an accident. This is clearly not an acceptable situation, and further investigation may be needed to establish the circumstances and to identify how and why the safety of the flight was compromised, so that action can be taken to address the safety issues and prevent recurrence.

- Equally, it may be very beneficial to understand why the occurrence didn’t escalate into an Accident so that the importance of any barriers or mitigations that were effective can be recognised and advocated to help prevent future accidents elsewhere.

- Fortunately, Accidents are relatively rare, but Incidents are much more common and provide opportunities to identify safety issues before they become manifest in an accident.

- Following an Incident or Serious Incident, the evidence will often be more accessible than following an Accident. For example, the whole aircraft should be available for examination, data should be relatively easy to retrieve, personnel should be able to explain what they saw, heard and did.

- Accidents sometimes have significant political, economic, social, technological, legal or environmental consequences. They can generate a lot of external attention, emotion and pressure. Free from such issues, Serious Incidents can provide a more conducive environment to gather evidence and complete an in-depth investigation focused on improving safety without concerns over blame or liability.

- Safety Investigation Authorities (SIA) like the AAIB have the authority to organise and lead a multidisciplinary and multinational team of investigators, experts and advisers. They have the legal powers to access all the evidence, and the tools, techniques and procedures to evaluate it thoroughly.

- SIA are acknowledged as the authoritative experts for air accident and incident investigation. They have a uniquely independent position from which to analyse the evidence impartially. Their findings and recommendations will be published and can be very influential in improving aviation safety.

However, Serious Incident investigation depends on the prompt notification of the occurrence to the AAIB so we can make a timely decision whether to investigate or not and the required actions can be taken to preserve the perishable evidence. At the time of initial notification, the information available may be quite limited or inaccurate which can sometimes make it difficult to assess whether there was a high probability of an accident. If in doubt, report the occurrence to the AAIB so we can gather evidence and assess the occurrence more fully. Further information is available at Report an air accident or serious incident - GOV.UK.

5. Concluding comments

Commercial Air Transport events which involve significant damage and/or significant injuries or fatalities will remain a priority for the AAIB’s investigation resources. This is driven by the needs of the general public and the aviation industry. It is however clear the investigation of Incidents and Serious Incidents over the last 30 years has proved to be highly significant in improving aviation safety.

-

Regulation: International Civil Aviation Annex 13. At the time of publication Annex 13 was on its twelfth edition, as of 2025 it is now on it’s thirteenth. ↩

-

Field investigations are typically where the AAIB have deployed a team for to a significant event, typically a GA fatal accident or a Commercial Air Transport Accident (few of which resulted in a fatality) or a Commercial Air Transport Incident or Serious Incident. Field investigations also include some investigations which are upgraded from a Correspondence to a Field Investigation. ↩

-

The UK State Safety Programme Objective can be accessed here ↩

-

CS 25.1305 AMDT 12 NPA - NPA 2011-13 - Large Aeroplanes protection against fuel low level and fuel exhaustion - EASA ↩

-

N1 engine fan or LP compressor rotational speed. ↩