Country policy and information note: smugglers, Iran, September 2025 (accessible)

Updated 7 January 2026

Version 5.0

September 2025

Executive summary

Up to 300,000 Kurds from the Western provinces of Iran make their living as kolbars, carrying goods across the mountainous Iran-Iraq border, circumventing the taxation of customs procedures. While most kolbars smuggle everyday household goods, a small number smuggle illegal items such as alcohol, weapons and narcotics.

While Iran’s Islamic criminal law does not criminalise kolbars, and some kolbars are issued permits, the smuggling of goods is a crime under Iran’s 2013 Law against Smuggling.

Available penalties for smuggling include confiscation of the goods, a fine, lashes and/or a prison sentence of up to 5 years, and the death penalty, depending on the type(s) and value of the goods. Where prosecutions result in trials, trials generally fail to meet international standards of fairness.

In general, kolbars do not fall within the scope of one of the 5 Refugee Convention grounds. However, the grounds of race and/or actual or imputed political opinion may apply depending on the circumstances of the case.

Relative numbers of kolbars killed or injured by Iranian border guards indicate that kolbars do not face a generalised risk of persecution or serious harm due to being targeted while carrying out their smuggling activities.

Kolbars who have been caught smuggling items subject to import tariffs, however, are likely to face prosecution. Where a kolbar faces prosecution resulting in a criminal trial, the trial is unlikely to meet international standards of fairness. Decision makers must consider the severity of the treatment or sentence that is likely to result from such a criminal trial.

Whether a criminal trial is likely to result in a sentence that is sufficiently serious to amount to persecution or serious harm will depend on the type(s) of items the person was caught smuggling and the nature of the charges made against the person.

A kolbar facing a criminal trial for the smuggling of everyday goods, and with no additional charges made against them, is unlikely to receive a sentence or treatment amounting to persecution or serious harm.

Each case must be considered on its facts and decision makers must consider any additional factors, such as actual or perceived political activity.

Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution or serious harm from the state, they will not, in general, be able to obtain protection nor be able to internally relocate to escape that risk.

Where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

All cases must be considered on their individual facts, with the onus on the person to demonstrate they face persecution or serious harm.

Assessment

Section updated: 19 September 2025

About the assessment

This section considers the evidence relevant to this note – that is the country information, refugee/human rights laws and policies, and applicable caselaw – and provides an assessment of whether, in general:

-

a person faces a real risk of persecution/serious harm by the state because of the person’s activities as a smuggler

-

internal relocation is possible to avoid persecution/serious harm

-

a claim, if refused, is likely or not to be certified as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

Decision makers must, however, consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts.

This note focuses primarily on the smuggling of goods across the Iran-Iraq border by Kurdish couriers known as kolbars (also referred to as ‘kulbar’, ‘koolbar’, ‘kolber’ or ‘kolbaran’). In Kurdish ‘Kol’ or ‘Kul’ means a person’s back and ‘Bar’ means ‘carry’ or ‘delivery’ (literally ‘those who carry on their back’).

1. Material facts, credibility and other checks/referrals

1.1 Credibility

1.1.1 For information on assessing credibility, see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

1.1.2 Decision makers must also check if there has been a previous application for a UK visa or another form of leave. Asylum applications matched to visas should be investigated prior to the asylum interview (see the Asylum Instruction on Visa Matches, Asylum Claims from UK Visa Applicants).

1.1.3 Decision makers must also consider making an international biometric data-sharing check, when one has not already been undertaken (see Biometric data-sharing process (Migration 5 biometric data-sharing process)).

1.1.4 In cases where there are doubts surrounding a person’s claimed place of origin, decision makers should also consider language analysis testing, where available (see the Asylum Instruction on Language Analysis).

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information on this page has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

1.2 Exclusion

1.2.1 Decision makers must consider whether there are serious reasons to apply one (or more) of the exclusion clauses. Each case must be considered on its individual facts.

1.2.2 If the person is excluded from the Refugee Convention, they will also be excluded from a grant of humanitarian protection (which has a wider range of exclusions than refugee status).

1.2.3 For guidance on exclusion and restricted leave, see the Asylum Instruction on Exclusion under Articles 1F and 33(2) of the Refugee Convention, Humanitarian Protection and the instruction on Restricted Leave.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information on this page has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

2. Convention reason(s)

2.1.1 In general, Kurdish smugglers (kolbars) do not fall within the scope of one of the 5 Refugee Convention grounds. However, race and/or actual or imputed political opinion may apply depending on the circumstances of the case.

2.1.2 Smugglers in Iran are not considered to form a particular social group (PSG) within the meaning of the Refugee Convention. This is because what distinguishes kolbars as a group is their activities. They do not, therefore, share an innate characteristic, or a common background that cannot be changed, or share a characteristic or belief that is so fundamental to identity or conscience that a person should not be forced to renounce it, and they do not have a distinct identity in Iran because they are not perceived as being different by the surrounding society.

2.1.3 Establishing a convention reason is not sufficient to be recognised as a refugee. The question is whether the person has a well-founded fear of persecution on account of an actual or imputed Refugee Convention reason.

2.1.4 Those who face prosecution for a criminal offence which would be a criminal offence if committed in the UK, will not qualify as refugees solely because they face prosecution on return unless the prosecution or punishment is discriminatory or disproportionately applied for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.

2.1.5 In the absence of a link to one of the 5 Refugee Convention reasons necessary for the grant of asylum, the question is whether the person will face a real risk of serious harm to qualify for Humanitarian Protection (HP).

2.1.6 For further guidance on the 5 Refugee Convention grounds, see the Asylum Instruction, Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

3. Risk

3.1.1 Relative numbers of kolbars killed or injured by Iranian border guards indicate that kolbars do not face a generalised risk of persecution or serious harm due to being targeted while carrying out their smuggling activities. The onus is on the person to demonstrate otherwise.

3.1.2 Kolbars who have been caught smuggling items subject to import tariffs, however, are likely to face prosecution. Where a kolbar faces prosecution resulting in a criminal trial, the trial is generally unlikely to meet international standards of fairness. Decision makers must consider the severity of the treatment or sentence that is likely to result from such a criminal trial.

3.1.3 Whether a criminal trial is likely to result in a sentence that is sufficiently serious to amount to persecution or serious harm will depend on:

-

the type(s) of items the person was caught smuggling; and

-

the nature of the charges made against the person

3.1.4 A kolbar facing a criminal trial for the smuggling of everyday goods (see paragraph 3.1.8), and with no additional charges made against them, is unlikely to receive a sentence or treatment amounting to persecution or serious harm.

3.1.5 Each case must be considered on its facts and decision makers must consider any additional factors, such as actual or perceived political activity (see also Country Policy and Information Note, Iran: Kurds and Kurdish political groups).

3.1.6 Driven by international economic sanctions, poverty, and high unemployment, thousands of Kurds from the Western provinces of Iran make their living as kolbars. They carry goods on foot, sometimes using pack animals, across the mountainous Iran-Iraq border, circumventing the taxation of customs procedures. Sources generally estimate kolbar numbers to be between 80,000 and 170,000, though one source estimated there to be as many as 300,000 kolbars in 2021. One source indicated that the number of kolbars increases in the winter due to there being fewer other job opportunities than during the rest of the year. The majority of kolbars are men but also, and increasingly, include women and children (see Kolbars, Locations and Prevalence).

3.1.7 Smuggling operations are hierarchical, organised, networks that are generally run by businessmen, and sometimes by criminal organisations or members of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). Border guards and officers can also be complicit, accepting bribes from kolbars and those higher up the smuggling chain (see Operations).

3.1.8 Most kolbars smuggle everyday household goods including food, clothing, electrical appliances, cosmetics, car parts, and cigarettes. Illegal items such as alcohol, weapons and narcotics, the movement of which being a more dangerous and criminal activity, are also, though rarely, smuggled across the border. There is a lack of recent evidence about the smuggling of political material such as political leaflets and posters (see Commodities and contraband).

3.1.9 Iran’s Islamic criminal law does not criminalise kolbars, and some kolbars, having met eligibility criteria, have been issued a ‘kolbari card’, permitting them to carry legal goods through official border crossings, though high demand reportedly made obtaining a kolbari card difficult. The kolbari card legitimises the work of the kolbars who hold them, affording them protections under Iran’s labour laws. However, Iran’s civil and commercial legislation recognises kolbari as smuggling and subject to prosecution. In May 2025 an announcement was reportedly made that during 2025 more than 62,500 kolbari cards would be issued. This equates to between 20% and 78% of kolbars being issued with a card, depending on which estimate of the overall number of kolbars is used. However, as of August 2025, CPIT has been unable to substantiate how many, or whether any, such permits have been issued (see Legal context and Prevalence).

3.1.10 Under Iran’s 2013 Law against Smuggling, the smuggling of goods is a crime, penalised by confiscation of the goods and a fine determined by the type(s) and value of the goods. Prohibited goods, such as alcohol, and items of a high value (over 100 million Iranian rials, approximately £1750 at the time of writing) carry available penalties of lashes and/or a prison sentence of between 6 months and 5 years. The death penalty is available for the smuggling of narcotics. In 2023, a kolbar was executed on suspicion of being a member of a Kurdish political party. Two kolbars, arrested in 2023 on charges of smuggling alcohol, were executed in 2024 for espionage, after they reportedly confessed under torture to involvement in the 2020 assassination of an Iranian nuclear scientist (see Penalties and prosecution).

3.1.11 Available information about the actual numbers of arrests of kolbars is extremely limited, but one 2021 report suggested they numbered ‘thousands each year’. Where prosecutions result in trials, the trials generally fail to meet international standards of fairness. There is a lack of available information about whether, or the extent to which, kolbars not arrested at the border might be later pursued by the Iranian authorities. Sources reported that Iranian border guards have raided kolbars’ houses, confiscating their belongings, though they did not report arrests arising from such raids. Border officials commonly mistreat kolbars, subjecting them to insults, verbal abuse, and acts designed to humiliate them. There are also frequent reports of border guards resorting to the use of excessive force along known kolbar routes, usually shootings, but also physical assaults, causing deaths and injuries with impunity and often without warning (see Treatment, arrest and detention, Penalties and prosecution, Excessive use of force, and Angi-smuggling operations).

3.1.12 During 2023 and 2024, between approximately 485 and 582 kolbars were reportedly killed or injured by Iranian border guards, or for reasons expressly reported to have involved Iranian border guard activities such as beatings, or during pursuits, by them. These figures should be considered in the context of there being up to 300,000 kolbars carrying goods across the Iran-Iraq border. Based on the lowest estimated number of kolbars (80,000) and the highest reported number of kolbars killed and injured by Iranian border guards in 2023 and 2024 combined (582), approximately 0.8% of kolbars were killed or injured by Iranian border officials over the two-year period. Other sources reporting on a one-year period only suggest that numbers could be higher (see paragraphs 9.5.10 and 9.5.11), however, even based on their reports, the 0.8% figure remains unchanged. The 0.8% figure is similarly unchanged when landmine deaths and injuries of kolbars during 2023 and 2024 (some of which may have been caused by Iranian border guards acting against kolbars) are included. While sources noted an escalation in state violence at the border against kolbar activities in the immediate aftermath of the 2025 Iran-Israel conflict/ceasefire, at the time of writing there is insufficient evidence to indicate a real or sustained escalation (see Treatment, arrest and detention, Prevalence and Excessive use of force).

3.1.13 Though not specifically addressing the situation for kolbars or smuggling (and CPIT was unable to find any recent evidence on the smuggling of political material), in the country guidance case of HB (Kurds) Iran CG [2018] UKUT 430 (IAC) (heard 20 to 22 February and 25 May 2018 and promulgated 12 December 2018), the Upper Tribunal found:

‘Since 2016 the Iranian authorities have become increasingly suspicious of, and sensitive to, Kurdish political activity. Those of Kurdish ethnicity are thus regarded with even greater suspicion than hitherto and are reasonably likely to be subjected to heightened scrutiny on return to Iran.

‘However, the mere fact of being a returnee of Kurdish ethnicity with or without a valid passport, and even if combined with illegal exit, does not create a risk of persecution or Article 3 ill-treatment.

‘Kurdish ethnicity is nevertheless a risk factor which, when combined with other factors, may create a real risk of persecution or Article 3 ill-treatment. Being a risk factor it means that Kurdish ethnicity is a factor of particular significance when assessing risk’ (paragraph 98(3) to (5)).

3.1.14 The Upper Tribunal in HB found that:

‘Activities that can be perceived to be political by the Iranian authorities include social welfare and charitable activities on behalf of Kurds. Indeed, involvement with any organised activity on behalf of or in support of Kurds can be perceived as political and thus involve a risk of adverse attention by the Iranian authorities with the consequent risk of persecution or Article 3 ill-treatment.

‘Even “low-level” political activity, or activity that is perceived to be political, such as, by way of example only, mere possession of leaflets espousing or supporting Kurdish rights, if discovered, involves the same risk of persecution or Article 3 ill-treatment. Each case however, depends on its own facts and an assessment will need to be made as to the nature of the material possessed and how it would be likely to be viewed by the Iranian authorities in the context of the foregoing guidance.

‘The Iranian authorities demonstrate what could be described as a “hair-trigger” approach to those suspected of or perceived to be involved in Kurdish political activities or support for Kurdish rights. By “hair-trigger” it means that the threshold for suspicion is low and the reaction of the authorities is reasonably likely to be extreme’ (paragraphs 98 (8) to (10)).

3.1.15 As noted above, CPIT was unable to find any recent evidence on the smuggling of political material. However, the country information in this note does not indicate that there are ‘very strong grounds supported by cogent evidence’ to depart from these findings.

3.1.16 While a person will not be at real risk of persecution or serious harm based on their Kurdish ethnicity alone, involvement in smuggling political materials should be considered as an ‘other factor’ which, when combined with Kurdish ethnicity, may create a real risk of persecution or Article 3 ill-treatment.

3.1.17 For further information on Kurds in general, and those involved in political parties, including the risk of arrest and detention, see the Country Policy and Information Note, Iran: Kurds and Kurdish political groups.

3.1.18 For further guidance on assessing risk, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

4. Protection

4.1.1 Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution or serious harm from the state, they will not, in general, be able to obtain protection.

4.1.2 For further guidance on assessing state protection, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

5. Internal relocation

5.1.1 Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution or serious harm from the state, they will not, in general, be able to internally relocate to escape that risk.

5.1.2 For further guidance on internal relocation and factors to consider, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

6. Certification

6.1.1 Where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

6.1.2 For further guidance on certification, see Certification of Protection and Human Rights claims under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 (clearly unfounded claims).

Country information

About the country information

This section contains publicly available or disclosable country of origin information (COI) which has been gathered, collated and analysed in line with the research methodology. It provides the evidence base for the assessment which, as stated in the About the assessment, is the guide to the current objective conditions.

The structure and content follow a terms of reference which sets out the general and specific topics relevant to the scope of this note.

This document is intended to be comprehensive but not exhaustive. If a particular event, person or organisation is not mentioned this does not mean that the event did or did not take place or that the person or organisation does or does not exist.

The COI included was published or made publicly available on or before 31 July 2025. Any event taking place or report published after this date will not be included.

Decision makers must use relevant COI as the evidential basis for decisions.

7. Background

7.1 Kolbars

7.1.1 On 8 March 2024, the Finnish Immigration Service (FIS), published a query response about the treatment of kolbars in Iran by the authorities. The report, which cited various sources, stated: ‘Kolbars are ethnically Kurdish.’[footnote 1]

N.B. the information quoted above, and all other COI quoted from this source throughout the rest of this CPIN was originally published in Finnish. All COI from this source has been translated using a free online translation tool. As such 100% accuracy cannot be guaranteed.

7.1.2 On 17 March 2024, Kurdistan 24, a multimedia news outlet that is based in the Kurdistan region of Iraq[footnote 2] [footnote 3], published an article entitled ‘Decade of danger: Iranian border security forces claim 589 Kulbar lives’. The article stated: ‘Kulbars, as they are referred to in Kurdish, are individuals who carry goods on their backs through rugged mountains to transport them between Iran and the Kurdistan Region … They carry an average of 75 kilograms (150 pounds) on their backs as they journey across the Zagros Mountains, back and forth to make a living amidst rampant unemployment.’[footnote 4]

7.1.3 On 8 July 2024, Human Rights Watch (HRW) published an article entitlted ‘Iran: Security Forces Killing Kurdish Border Couriers’ which, citing various sources, stated:

‘Border couriers, who are often Kurdish, transport goods between Iran and Iraq by bypassing customs, typically earning payment based on the weight and type of goods they carry. The Kurdish word Kulbar, is derived from “Kul” meaning back and “bar” meaning carrier. They often carry loads weighing between 25 to 50 kilograms (55 to 110 pounds), sometimes heavier, along mountainous routes averaging around 10 kilometers, with some routes stretching longer distances. A small number also carry their loads on horses and mules. Payment varies depending on factors such as load weight, route, and economic conditions.’[footnote 5]

7.1.4 The same HRW article stated: ‘United for Iran, a human rights group, said that the border couriers are mostly men and boys ages 13 to 65. But that they include some women.’[footnote 6]

7.1.5 On 21 January 2025, Hengaw Organization for Human Rights (Hengaw), an organisation that covers human rights violations across Iran, including in the Kurdish region of Iran[footnote 7] [footnote 8], published a report which stated that ‘individuals aged 13 to 70 years are often engaged in Kolbari.’[footnote 9]

7.1.6 In June 2024, the European Union Agency for Asylum (EUAA) published a report entitled ‘Iran – Country Focus’ which cited various sources. Citing information from Barzoo Eliassi, an associate professor at a Swedish university with extensive experience on statelessness and Kurdish minorities[footnote 10], the report stated: ‘… Kurdish women kolbars, who carry heavy goods … dress as men to avoid sexual assault and social pressure.’[footnote 11]

7.1.7 On 21 November 2024, Peace Mark, a publication about human rights written by a group of human rights activists in Iran[footnote 12] published an article about steps reportedly taken to regulate kulbari in Iran. The article stated:

‘Female kulbars, often starting in their teenage years, represent one of the most marginalized segments of the working class. They face not only economic deprivation but also exclusion from broader social transformations. Reports indicate that many female kulbars are undercounted in workforce statistics and often receive lower wages than their male counterparts.

‘Economist Parviz Sadaqat highlights that kulbari is a class issue, though it also intersects with patriarchal and ethnic oppression in the case of female kulbars.’[footnote 13]

7.1.8 On 15 January 2025, an annual report on kolbars killed and injured in 2024 was published by Kolbarnews English, an English-language website which ‘provides updates on issues concerning kolbars and Sukhtbars [fuel carriers[footnote 14]]’[footnote 15]. The report noted that there is an ‘… increasing presence of children, adolescents, the elderly, educated individuals, and even women among Kolbars …’[footnote 16] The report did not provide any actual numbers on the demographics of kolbars, nor did it state what information its assertion was based upon.

7.1.9 On 25 May 2025, HANA Human Rights Organization (HANA), ‘an independent, non-governmental, non-profit organization committed to advancing human rights, with a particular focus on the Kurdistan region of Iran’[footnote 17], published a report on the ‘Phenomenon of Kolbari (Border Portering)’ which stated: ‘According to research conducted by Hana Human Rights Organization, two-thirds of kolbars fall within the age range of 13 to 24 years, while the remaining one-third are between 24 and 70 years old. Many of them are married and some even hold university degrees … In recent years, kolbari has significantly increased among Kurdish women. Many female heads of households in towns and border villages now work as kolbars.’[footnote 18]

7.1.10 For information about the treatment of Kurds on account of their ethnicity and/or for political reasons, see the Country Policy and Information Note, Iran: Kurds and Kurdish political groups. For information about the numbers of people who work as kolbars, see Prevalence.

7.2 Locations

7.2.1 For a map showing the location of the provinces referred to in this sub-section, see Maps.

7.2.2 On 9 October 2023, Kurdshop, a Kurdish non-governmental organisation, based in Erbil in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq[footnote 19], published part 1 of an article about kolbari (the act of cross-border porterage[footnote 20]) which stated: ‘The phenomenon of Kolbari [takes place] in the border areas of the eastern part of Kurdistan … The largest number of people engaged in Kolbari belong to Kermashan, Paveh, Gialan, Nowsud, and Qasre Shirin cities in Kermashan province, Mariwan, Bana, and Sawlawa in Sna [Kurdistan] province, Sardasht, Shno (Oshnavieh), Piranshar, and Bokan in Urmia [West Azerbaijan] province.’[footnote 21]

7.2.3 An article published on 15 June 2024 by Iran Focus, ‘a news service provider focusing on current events in Iran, Iraq and the Middle East’[footnote 22] with links to the armed opposition movement Mojahedin-e Khalq (MeK)[footnote 23], stated that kolbari ‘… is very common in the border areas of Iran because the Iranian regime does not provide any facilities or jobs for the youth in these regions … Most of these individuals are found in the western and southeastern regions of Iran. The issue of “illegal” import and export of goods in Iran is not limited to a specific border or region.’[footnote 24]

7.2.4 On 5 July 2024, a joint report about the Kurdish kolbar community was published by The Centre for Supporters of Human Rights (CSHR), a non-governmental organisation which promotes human rights in Iran and the broader Middle East[footnote 25], and The Kurdistan Human Rights Association – Geneva (KMMK-G), an organisation that ‘serves as a vital link between Kurdish civil society, UN agencies, and NGOs’[footnote 26]. The report was supported by the Minority Rights Group (MRG), an ‘international human rights organization working with ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities, and indigenous peoples’[footnote 27], and cited various sources. It stated: ‘… [R]egions with the highest concentrations of kulbars include Baneh, Marivan and Saqqez in Kurdistan province, Mako, Ashnoye, Sardasht and Piranshahr in West Azerbaijan, as well as Nusud and Paveh in Kermanshah province.’[footnote 28]

7.2.5 The 8 July 2024 HRW article similarly stated: ‘Provinces with large Kurdish communities like Kermanshah and Kurdistan were among the top 10 provinces with the highest unemployment rates last year, as reported by AsrIran news website, and many border couriers come from these areas.’[footnote 29]

7.2.6 In August 2024, the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) published a report of its Independent International Fact-finding Mission on the Islamic Republic of Iran. The report, which cited various sources, stated: ‘Widespread unemployment and poverty have resulted in some residents of Kurdistan, Kermanshah, Sistan and Baluchestan, and West Azerbaijan engaging in hazardous cross-border couriering (commonly referred to as kulbar in Kurdistan or soukhtbar in Sistan and Baluchestan), which entails importing merchandise through unofficial routes on the north-western borders of Iran.’[footnote 30]

7.2.7 On 21 January 2025, Hengaw Organization for Human Rights (Hengaw), an organisation that covers human rights violations across Iran, including in the Kurdish region of Iran[footnote 31] [footnote 32], published a report on Kurdish kolbars killed and injured in 2024. The report stated: ‘In the border regions of Kurdistan, encompassing Kermanshah, Kurdistan (Sanandaj), and West Azerbaijan (Urmia) provinces ….’[footnote 33]

7.2.8 On 24 April 2025, the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN), ‘a France-based independent, non-profit and non-partisan organisation promoting human rights and documentation of violations in Iran’s Kurdish region’[footnote 34], published its annual report covering the period from 20 March 2024 to 19 March 2025 (the Iranian year 1403, converted to the Gregorian calendar[footnote 35]). The report stated: ‘According to official statistics, the provinces of Kurdistan, Ilam, and Kermanshah continue to suffer from the highest levels of poverty and deprivation in the country. A large portion of the population in these areas - especially those living near the borders - has turned to kolbari due to the lack of proper industrial and commercial infrastructure.’[footnote 36]

7.3 Prevalence

7.3.1 On 10 October 2023, Kurdshop published part 2 of its article about kolbari which stated: ‘… [T]he number of Kolbars may be more than 100,000.’[footnote 37]

7.3.2 The FIS report, published in March 2024, citing various sources, stated: ‘Estimates of the number of smugglers range between 80,000 and 300,000.’[footnote 38] CPIT noted that the sources relied upon for these estimates were published between February 2020 and October 2021.

7.3.3 The Kurdistan 24 article, published on 17 March 2024, stated: ‘High rates of unemployment, poverty, high prices of basic goods and food supplies, and the recent devaluation of the currency have led to an increase in the number and percentage of porters in the border areas of western provinces of Iran.’[footnote 39] The article did not provide any estimated numbers of kolbars in these areas, nor did it state what information its assertion that there has been ‘an increase in the number and percentage of porters in the border areas of western provinces of Iran’ was based upon.

7.3.4 The CSHR and KMMK-G report, published in July 2024, stated: ‘Iran’s official news agencies have reported varying estimates for the number of kulbars, ranging from 170,000 individuals during peak times to 80,000.’[footnote 40] The report referenced the IRNA (Islamic Republic News Agency, ‘the official news agency of the Islamic Republic of Iran’[footnote 41]) in 2024 as the source of the estimated range, which CPIT have been unable to access directly. However, CPIT noted that an article about kolbars, published on 12 February 2020 by IranWire, an Iranian news website[footnote 42], provided the same estimated range, which it attributed to official statistics reported by the IRNA in December 2019[footnote 43]. The same IranWire article was also one of the sources relied upon in the esimates provided by the FIS report (see paragraph 7.3.2).

7.3.5 The same CSHR and KMMK-G report stated:

‘Kulbari is an activity shaped by season: the numbers of those involved rises significantly during winter months, when there are fewer opportunities for paid employment, and declines during other seasons, when there are, for example, agricultural, small manufacturing and building opportunities. Most of the [23[footnote 44]] kulbars interviewed for this report emphasised that they only started this job due to the lack of other opportunities in the area, and for many, it represents the sole lifeline for generating income.’[footnote 45]

7.3.6 The Hengaw report covering kolbar fatalities and injuries in 2024, published in January 2025, stated: ‘According to unofficial statistics, 100,000 to 150,000 people work as Kolbars in Kurdistan’s border regions.’[footnote 46]

7.4 Operations

7.4.1 Part 1 of the Kurdshop article, published on 9 October 2023, stated:

‘“Kolbari is a hierarchical job with different levels, which includes: Kolbar, baggage owner, escort, and driver.” All of these jobs are dangerous … Goods that cannot be imported from official borders due to high taxes, manpower or Kolbars are used to transport them. The importers of these goods are “locals” familiar with the socio-economic structure across borders, a phenomenon that has gradually led to the creation of a new capitalist class, increasing their capital and social power. A class that is forced to attach itself to the government and policies of the authorities in order to keep their capital and social power.’[footnote 47]

7.4.2 Part 2 of the Kurdshop article, published on 10 October 2023, stated:

‘… [O]nly a small portion of the revenue and profits of border trade reaches the people of the border areas … [T]he huge profits from importing goods through the border areas reach the large networks in this area and do not benefit the local population of the borders … [T]he important point is to circumvent the economic sanctions of the government and the capitalist class. In addition, Kolbars are an important source of income for border guards and officers by accepting bribes from Kolbars and goods owners.’[footnote 48]

7.4.3 On 4 March 2024, a blog about Kolbars in Iran, originally published on 29 February 2024, was updated by the School of Global Studies at the University of Gothenburg. The blog, which cited various sources, stated: ‘Businesspeople from the big cities in Iran buy goods on the internet (or via their local contacts) in large quantities from Oman, China, Dubai, or elsewhere, which are then sent by truck to the autonomous Iraqi Kurdish region waiting for Kolbars to carry them into Iran.’[footnote 49]

7.4.4 The FIS report, published in March 2024, stated:

‘The transportation of goods is highly organised activity and part of the work is controlled by criminal organisations, with lawful products also being managed by Iranian entrepreneurs living in the cities, according to Iran Wire [in 2020] … There are intermediaries operating on both sides of the border who ensure that goods are delivered close to the border, from where the kolbars collect the products and take them to the other side of the border to a location from which the intermediary again transports the goods further into Iran.’[footnote 50]

7.4.5 The CSHR and KMMK-G report, published in July 2024, stated: ‘Kulbari … comprises a verbal relationship and agreement between kulbars and those who wish to transport goods, often across the Iran-Iraq border. The contractors may also be the owners of the commercial goods they seek to transport, but more generally, they are part of the supply chain. The character of the relationship between contractor and kulbar is termed, in Iranian law, “jo’ale” …’[footnote 51]

7.4.6 The same CSHR and KMMK-G report also stated:

‘Kulbari starkly ignores workplace standards mandated by labour norms, such as maximum working hours and safety regulations. The law emphasizes that workplaces must meet safety standards, yet kulbars navigate perilous mountains without these safeguards. Furthermore, working hours for kulbars are undefined, and the identity of their employers and cargo recipients often remains a mystery, increasing the risk of rights violations, particularly regarding fair payment … Kulbars … often receive less than 1 per cent of the value of the goods they transport … [K]ulbars are vulnerable to exploitative practices by employers and traders.’[footnote 52]

7.4.7 An article published on 1 January 2025 by The New Region, a news outlet reporting on the Middle East with a particular focus on Iraq[footnote 53], stated: ‘Kolbars are only a small organ in a much larger and profitable body. People with no other options to make ends meet, often carry tens of kilos of different goods on foot across mountainous and snowy borders patrolled by brutal Iranian border guards. While businessmen make loads of money through such trade, kolbars are given only a tiny portion of the money, sometimes barely enough to put food on their table.’[footnote 54]

7.5 Commodities and contraband

7.5.1 On 24 July 2023, the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) published its ‘Iran Country Information Report’. It stated: ‘The Iranian government claims the kolbars traffic illegal goods, including narcotics.’[footnote 55]

7.5.2 Part 1 of the Kurdshop article, published on 9 October 2023, stated: ‘Most of the goods transported by Kolbars include televisions, coolers, cigarettes, refrigerators, alcoholic drinks, clothes, and textiles.’[footnote 56]

7.5.3 The blog published by the School of Global Studies at the University of Gothenburg, updated on 4 March 2024, stated: ‘Some of the everyday items Kolbars carry on their back are electronic appliances, clothing, textiles, home appliances, car tires, cigarettes, gasoline, cosmetics; and in rare conditions, they transport alcoholic drinks, pepper sprays, and guns.’[footnote 57]

7.5.4 The FIS report, published in March 2024, stated: ‘Iranian authorities consider kolbars to be smugglers of illegal goods. Kolbars mainly transport conventional consumer goods, the export of which to Iran is often restricted due to international economic sanctions, but this way couriers also circumvent Iran’s customs regulations. The products can include food, electronics or car parts.’[footnote 58]

7.5.5 The HRW article that was published on 8 July 2024 stated:

‘The border couriers typically transport consumer goods legally available for sale. This includes a range of items such as tea, packaged foods, electronics, textiles, footwear, clothing, kitchenware, health and beauty products, tires, mobile phones, and occasionally cigarettes. Border couriers told Human Rights Watch that alcoholic beverages are generally avoided because there are prohibitions on transporting alcohol and alcoholic consumption, which can result in significant fines or imprisonment.’[footnote 59]

7.5.6 On 10 April 2025, Tasnim News Agency, a media outlet owned by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC)[footnote 60], published an article entitlted ‘Iran, Iraq Launch Joint Border Patrols to Bolster Security’ which stated: ‘The deputy police chief [of Iran’s Law Enforcement Force, Brigadier General Qassem Rezaei] … [said] that in the past, weapons and contrabands used to be smuggled into Iran, but Iraqi forces are now actively intercepting such goods.’[footnote 61]

7.5.7 CPIT was unable to find any recent information about the smuggling of political material such as political leaflets and posters in the sources consulted (see Bibliography).

8. Legal context

8.1 Legal framework

8.1.1 A 2008 paper on illegal trade in Iran, by Mohammad Reza Farzanegan from the Center for Near and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Marburg, cited the laws relating to smuggling goods:

‘The main relevant rules and regulations in Iran about smuggling are “Penal codes on smuggling” (1933), “Custom rule” (1971), and “Governmental discretionary punishments rule” (1994). The 1933 punishment rule for smuggling identified different kinds of smuggling. This classification covers the following groups: (1) the smuggling of legal products; (2) the import smuggling of illegal products; (3) the export smuggling of illegal products; (4) the smuggling of monopoly products; and (5) special activities.’[footnote 62]

8.1.2 The paper defined the classifications:

- Legal products (categorised into 2 groups):

‘First are those goods which do not need the permission of relevant governmental organizations for importing or exporting. These groups of goods will be determined by the Ministry of Commerce in annual import and export regulations at the beginning of each year. After the approval of the Council of Ministers, the list of these goods will be announced to national customs.

‘Second are conditional legal products. These are legal products, which because of a special situation in the domestic economy and general socio-political policies, need prior permissions by governmental organizations. For example, the import of special machinery products or medicines may require permission from the Ministry of Industry and Mines and Ministry of Health, respectively.

- Import and export of illegal products:

‘Custom rule has determined these products. Some examples of imported illegal goods are military weapons, drugs and anti-religious or materials printed which are opposed to social norms (books, magazines and so on)… In general, export smuggling of illegal goods refers to the export of those products that are prohibited based on religious or governmental rules.

- Monopoly products:

‘Monopoly products are those goods which based on monopoly regulations (such as the monopoly of tobacco rule, 1931) can be traded only by the government. Thus, trading such products without having the legal representation of the government is referred to as trading smuggled goods.

- Special activities:

‘… special activities which are not smuggling in theory but based on the perspective of the authorities will be treated as smuggling in practice. For example, Article 48 of Jungles Protection and Maintenance rule of 1985 declares that “transport of woods and gained coals from trees out of cities without licence from the Forestry Organization will be punished like a smuggling act”. Another example is Article 1 of “Penal codes of sellers of anti-religious or anti-public decency textiles”. The economic agents who import, produce, or sell such textiles are offenders and these textiles are treated as smuggled goods.’[footnote 63]

8.1.3 The CSHR and KMMK-G report, published in July 2024, stated:

‘The foreign trade landscape in Iran was significantly transformed by the “Iranian Foreign Trade Monopoly Law” in March 1931 and its revisions. This act transitioned foreign trade from being unregulated to becoming a state monopoly, giving authorities control over imports and exports. Despite legal constraints, like licensing, border residents continued to see cross-border trade as their right. This led to the creation of specialized rules for cross-border exchange. Islamic criminal law, the main criminal legislation, is silent on cross-border transactions and relevant laws. However, specific laws such as the 1993 Export and Import Regulations, the Customs Affairs Law of 2011 and the 2013 Law on Combating Goods and Currency Smuggling address this.

‘The Export and Import Law does not cover export and import violations, unlike the Customs Affairs Law, which dedicates a section to customs and smuggling. Article 113 defines smuggling as unauthorized goods movement without customs compliance. Notably, this law does not set penalties for smuggling …’[footnote 64]

8.1.4 The same CSHR and KMMK-G report stated:

‘The core measures intended to regulate cross-border trade by kulbars, though not all culminating in legislation, include:

-

‘The October 2005 Law on the Organization of Border Exchanges.

-

‘A 22 November 2017 initiative announced by the Interior Minister to close certain crossings, allowing only Sole Trader card holders to use the official borders.

-

‘An April 2018 bill formulated by Interior Minister Abdolreza Rahmani Fazli, which was approved by the cabinet to regulate and reform kulbari.

-

‘A December 2019 bill proposed by a group of parliament members in response to the growing fatalities among kulbars, aiming to amend the law on the use of firearms by the armed forces.

-

‘A July 2021 proposal by Kamal Hosseinpour, representing Sarsdasht and Piranshahr, to establish border bazaars.

-

‘A 28 February 2023 report citing Shahriar Heydari, representing towns in Kermanshah province and a member of the National Security and Foreign Policy Committee, who announced a forthcoming bill to provide a framework for kulbari, set for implementation around April/May 2023.’[footnote 65] (See also paragraph 8.1.9).

8.1.5 The CSHR and KMMK-G report also stated: ‘Iran’s labour law does not specify provisions for kulbars and there’s an absence of unions or organizations for their support. Thus, kulbars often go without legal protection or assistance, leaving them vulnerable to shootings, natural disasters or wage theft. Many injured kulbars also struggle to afford hospital bills and basic living costs.’[footnote 66]

8.1.6 The CSHR and KMMK-G report additionally stated: ‘Regarding the question of legality, kulbars’ actions of transporting goods without paying duties are illegal insofar as they constitute the transport of goods across an international frontier … The legal status of kulbari is a complex interplay of informal contractual relationships, civil law regulations and commercial law classifications.’[footnote 67]

8.1.7 The HRW article that was published on 8 July 2024 stated:

‘Since 2020, there have been plans in the government and parliament on regulatory measures for border couriers’ work, support for border communities’ socioeconomic needs, and calls to limit the use of lethal force against Kulbars.

‘Yet, officials in Iran’s security forces have framed this activity as a security issue. On December 16, 2018, Espadana Khabar News Agency, quoting General Qasem Rezaei, the commander of Iran’s border guards, saying that “borders are defined by law; any unauthorized crossing of the border is considered a crime….”

‘… In June 2023, a member of the Iranian parliament’s National Security Commission announced the completion of a review of pending legislation, with proposed amendments that not only broaden the range of authorities authorized to use firearms but also the conditions under which they can do so. If passed into law, the amendments would put the couriers at even greater risk.’[footnote 68]

8.1.8 Amnesty International noted in its annual report, published on 28 April 2025 and covering events during 2024, that the bill remained ‘… pending before parliament amid calls by high-level officials to expedite its passing’[footnote 69]. CPIT was unable to locate any further updates on the status of the firearms bill in the sources consulted (see Bibliography). See also Excessive use of force.

8.1.9 The Peace Mark article, published on 21 November 2024, stated:

‘In … December 2022 – January 2023 … the Vice President for Parliamentary Affairs announced the submission of an urgent bill titled Regulation and Oversight of Border Trade (Kulbari and Maritime Commerce) aimed at creating sustainable employment for border residents …

‘The bill prioritizes transparency in imports, distribution, and sales of goods traded by border residents. It seeks to strengthen border economies, reduce informal trade along land and sea borders, and ensure that imported goods meet customs and trade standards after five years. Exceptions apply only to goods required for the immediate needs of border residents and local businesses in border areas.

‘… In … August–September 2023 … parliament completed its review of the kulbari regulation bill. Representatives approved the full allocation of customs and tax revenues from border trade regulation back to the originating provinces. This measure effectively placed responsibility for implementation on provincial governors.

‘… Ultimately, the bill passed with urgency and without substantial amendments from the Economic Commission.

‘… Kulbari … remains undefined within the country’s commercial and customs laws. Attempts by the cabinet in 2017 and 2018 to address these issues failed due to legislative gaps and other challenges.’[footnote 70] CPIT was unable to locate any further updates on the status of the kulbari regulation bill in the sources consulted (see Bibliography).

8.1.10 An article published by HANA on 26 July 2025 stated: ‘Kolbari is neither defined in Iranian law nor recognized by the Islamic Republic’s legal system as an official profession. Consequently, kolbars are excluded from all legal protections related to labor, insurance, and occupational safety. This legal vacuum makes them highly vulnerable to violence, exploitation, and systemic injustice.’[footnote 71]

8.2 Penalties and prosecution

8.2.1 On 24 December 2013, the Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) adopted its ‘Law against Smuggling’, which was published in Persian by NATLEX, a ‘[d]atabase of national labour, social security and related human rights legislation’[footnote 72], of the International Labour Organization (ILO). The law, which has been translated using a free online translation tool (as such 100% accuracy cannot be guaranteed), states:

‘Chapter Three - Smuggling of Permitted, Conditionally Permitted Goods, Subsidies and Currency

‘Article 18 - Any person who commits smuggling of goods and currency, and transport or storage thereof, shall, in addition to the confiscation of the goods or currency, be subject to the following fines:

‘A - Permitted Goods: A fine of one to two times the value of the goods.

‘B - Conditionally Permitted Goods: A fine equal to one to three times the value of the goods.

‘C - Subsidised Goods: A fine equal to two to four times the value of the goods.

‘D - Currency: A fine for incoming currency, one to two times its equivalent in rials, and a fine for outgoing currency, two to four times its equivalent in rials.

‘Note 1 - The supply and sale of smuggled goods subject to this article is considered a crime, and the offender shall be subject to the minimum penalties provided in this article.

‘Note 2 - A list of goods subject to subsidies proposed by the Ministries of Economic Affairs and Finance and Industry, Mining and Trade is to be prepared and approved by the Cabinet.

‘Note 3 - The Ministry of Industry, Mining and Trade is obliged to announce the list of conditionally permitted goods.’[footnote 73]

8.2.2 The ‘Law against Smuggling’ goes on to state:

‘Chapter Four - Smuggling of Prohibited Goods

‘Article 22 - Anyone who commits the smuggling of prohibited goods or stores, transports, or sells prohibited goods shall, in addition to the confiscation of the goods, be punished as follows …

‘A - If the value of the goods is up to ten million (10,000,000) rials [approximately £174.60 GBP[footnote 74]], a fine equivalent to two to three times the value of the smuggled prohibited goods.

‘B - If the value of the goods is between ten million (10,000,000) and one hundred million (100,000,000) rials [approximately £1746 GBP[footnote 75]], a fine equivalent to three to five times the value of the smuggled prohibited goods.

‘C - If the value of the goods is between one hundred million (100,000,000) and one billion (1,000,000,000) rials [approximately £17,462 GBP[footnote 76]], imprisonment of more than six months to two years and a fine equivalent to five to seven times the value of the smuggled prohibited goods.

‘D - If the value of the goods exceeds one billion (1,000,000,000) rials, imprisonment of two to five years and a fine equivalent to seven to ten times the value of the smuggled prohibited goods.

‘Note 1 - The provision of Article (702) of the Islamic Penal Code [see paragraph 8.2.5], as amended by Act No. 22/8/1387, applies only to alcoholic beverages produced domestically.

‘Note 2 - Proceeds from the smuggling of prohibited goods shall be confiscated.

‘Note 3 - Tools and equipment used for the manufacture of prohibited goods for the purpose of smuggling or facilitating the commission of such smuggling shall be confiscated. Items that the user does not own and which the owner has not deliberately provided to the perpetrator shall not be subject to the provisions of this note.

‘Note 4 - Alcoholic beverages, historical-cultural assets, equipment received from satellites illegally, gambling devices, and obscene audio and visual materials are examples of prohibited goods.

‘Note 5 - The place of storage for prohibited smuggled goods owned by the perpetrator shall be confiscated and sealed, provided it does not fall under the provisions of Article (24) of this law. If the convicted party does not pay the fine within two months from the date of the final judgment, the proceeds from the sale shall be deducted as appropriate and the remainder shall be returned to the owner.’[footnote 77]

8.2.3 The FIS report, published in March 2024, stated:

‘According to the Minority Rights Group [in a report published in June 2020[footnote 78]], arrested kolbars may face charges of illegal importation of goods and additionally charges depending on what they have smuggled and whether the product is illegal in Iran … The Minority Rights Group states that some types of smuggling may also result in punishment by flogging.

‘Possession and trafficking of narcotics can be punished with the death penalty in Iran. There is little information available about the penalties actually received by drug mules … An article in Outside magazine [published in October 2021[footnote 79]] tells of a mule who had been arrested [while smuggling chicken livers[footnote 80]] and received a six-month prison sentence.

‘The Minority Rights Group also notes that legal proceedings in Iran’s judicial system generally do not meet the principles of a fair trial. Defendants may be subjected to torture and ill-treatment, may be forced to confess, or may be denied the right to a lawyer or other representative. According to the Minority Rights Group, minorities may also become targets of political trials due to their ethnicity, and as Kurds, they may be accused of endangering national security, for instance due to assumed social activity or membership in a Kurdish political party.’[footnote 81] It is noted that while multiple references were made to the state treatment that may be faced by arrested / charged kolbars, it did not state whether, nor did it quantify the scale or extent to which, such treatment was actually faced by kolbars. Additionally, limited evidential weight has been placed upon the example provided (of a mule sentenced to 6 months imprisonment) in the absence of further information to indicate that this example is reflective of general practices, and in view of its age.

8.2.4 The FIS report also stated:

‘The Iran Human Rights NGO [(IHRNGO), a Norway-based ‘non-profit, human rights organization with members inside and outside Iran’[footnote 82]] operating from Norway reports [in a joint report with Together Against the Death Penalty (ECPM) published in March 2024[footnote 83]] that a total of 471 people were executed in Iran in 2023 for drug-related crimes and 39 people for endangering national security. These charges are handled in revolutionary courts, where trials have been found to systematically violate principles of justice.’[footnote 84]

8.2.5 Specific penalties are prescribed in the Penal Code for offences relating to alcohol:

‘Article 702 – Anyone who produces or buys or sells or proposes to sell or carries or keeps alcoholic beverages or provides to a third person, shall be sentenced to six months to one year of imprisonment and up to 74 lashes and a fine five times as much as the usual (commercial) value of the aforementioned object.

‘Article 703 – Importing alcoholic beverages into the country shall be considered as smuggling and the importer, regardless of the amount (of the beverages), shall be sentenced to six months to five years’ imprisonment and up to 74 lashes and a fine ten times as much as the usual (commercial) value of the aforementioned object. This crime can be tried in the General Courts.

‘Note 1 - In respect to articles 702 and 703, when the discovered alcoholic beverages are more than twenty liters, the vehicle used for its transport, if its owner is aware of the matter, shall be confiscated in favor of the government; otherwise the offender shall be sentenced (to a fine) equal to the value of the vehicle. Tools and equipments used for producing or facilitating the crimes mentioned in the said articles, as well as the money gained through the transactions, shall be confiscated in favor of the government.

‘Note 2 - When civil servants or employees of governmental companies or companies or institutes dependant to government, councils, municipalities or Islamic revolutionary bodies, and basically all the three powers and also members of armed forces and public service officials, commit, or participate, or aid and abet in the crimes mentioned in articles 702 and 703, in addition to the punishments provided, they shall be sentenced to one to five years’ temporary suspension from civil service.

‘Note 3 - The court, under no circumstances, shall suspend the execution of the punishment provided in articles 702 and 703.’[footnote 85]

8.2.6 Some recent examples of penalties handed down to prosecuted kolbars include (Note: this is not intended to be an exhaustive list):

- a kolbar who was executed in March 2023, on charges of membership in an opposition political group and possession of a weapon, which he reportedly confessed to under torture after his November 2017 arrest. It was reported that the kolbar was sentenced to death after an unfair trial[footnote 86] [footnote 87] [footnote 88]

In a special report on the circumstances up to the execution, the KHRN noted that the kolbar was shot by Iranian border forces and was taken to hospital in the West Azerbaijan province before being transferred to an IRGC detention centre 3 days later where he was interrogated and severely tortured for months. A source close to the prisoner informed the KHRN that the kolbar was carrying 4 cartons of alcoholic beverages on 2 horses while an armed group, who were carrying weapons in the area at the same time, escaped the gunfire. The source noted that the IRGC considered a weapon load found nearby to belong to the kolbar despite having no evidence. The KHRN report, unlike some other sources, reported that the kolbar denied the charges made by the IRGC at all stages of his interrogation and trial[footnote 89].

-

a 17-year-old kolbar from the Kurdistan province who was reportedly sentenced to 2 years’ imprisonment, 74 lashes, and a fine in March 2024 after being arrested while working at the border[footnote 90] [footnote 91]. Hengaw reported that the minor was being held at Marivan prison, but that the exact charges on which the kolbar was convicted were not known[footnote 92]. The sources did not report on the type(s) of goods being carried by the 17-year-old kolbar

-

a kolbar from Marivan who, after being shot and injured by Iranian border guards in March 2024, was sentenced in April 2025 to five years in prison and a fine, before his arrest and transfer to Marivan Central Prison on 12 May 2025 to begin serving his prison sentence[footnote 93] [footnote 94]. KolbarNews, which described his prison sentence as a ‘discretionary prison sentence’ also reported that the kolbar was not carrying any load at the time of him being shot in March 2024[footnote 95]. Neither report, however, provided any further information regarding the nature of the charges upon which he was convicted

-

3 kolbars who were reportedly arrested and detained on charges of smuggling on 23 April 2024, and were fined 30 million tomans [£5,297 GBP[footnote 96] [footnote 97]] after appearing in court on 24 April 2024[footnote 98] No further details were reported or could be found by CPIT within the sources consulted (see Bibliography)

-

2 Kurdish Iranian kolbars who were executed in June 2025 (alongside a Kurdish Iraqi ‘merchant’) for their alleged involvement in espionage for Israel[footnote 99] [footnote 100] [footnote 101]. Some sources specified the charges to have been the ‘spreading corruption on earth’ and ‘enmity against god’[footnote 102] [footnote 103]

A KHRN article, published on 6 November 2024 stated that the 3 men ‘… brought equipment for the assassination of … Fakhrizadeh [Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, an Iranian nuclear scientist who was killed in November 2020 in a remote attack that Iran believed Israel and an exiled opposition group were responsible for[footnote 104]] into the country under the guise of smuggling alcohol …’[footnote 105]. The KHRN article also noted that the executed men were ‘… deprived of the right to a designated lawyer during the investigation phase of the Prosecutor’s Office …’[footnote 106]

N.B. the information from the November 2024 KHRN article quoted above was originally published in Farsi. All COI from this source has been translated using a free online translation tool. As such 100% accuracy cannot be guaranteed.

The IHRNGO article, citing its Director, Mahmood Amiry Moghaddam, stated that the 2 kolbars were arrested on charges of smuggling alcoholic beverages but were forced to confess to espionage under torture[footnote 107]

8.3 Permits

8.3.1 The CSHR and KMMK-G report, published in July 2024, stated:

‘The 2005 Law on Border Exchanges categorizes kulbars into two groups. The first holds a valid kulbari card, enabling lawful passage through official borders under certain conditions [such as along specific paths and in compliance with legal standards[footnote 108]], aligning their activities with the law and legitimizing their contracts with goods owners. This establishes an employee-employer relationship that is protected under labour law.

‘The second group undertakes kulbari activities through unofficial borders without settling duties and customs, considered illegal under the 2013 Law on Combating Smuggling of Goods and Currency. Their contracts with goods owners are void, removing them from the protections of labour law …’[footnote 109]

8.3.2 The same CSHR and KMMK-G report also stated: ‘… [I]llegal kulbars lack authorization and face risks of arrest or prosecution.’[footnote 110]

8.3.3 Part 2 of the Kurdshop article, published on 10 October 2023, stated:

‘In addition to residents of border towns, people living within 50 kilometers of the border can register in the border residents’ system and use the services of the Kolbari card. These cards are only issued to people over the age of 18 who are head of a family, live in border areas, do not work in government and military institutions, do not receive government salaries, are educated, have [no] mental health [conditions], have no crimes, and are not addicted to any drugs, and they are not indebted to the government; including customs duty debt, foreign currency obligations due to re-exports, etc. Individuals without these points can obtain a card in their own name for border transactions within Article 20 of Iranian law. The government has distributed 17,000 cards for Kolbars …’[footnote 111] The article did not specify which Iranian law it was referring to when it cited ‘Article 20 of Iranian law’.

8.3.4 The FIS report, published in March 2024, stated:

‘Although the transportation of goods is essentially illegal from the perspective of Iranian authorities, some porters carrying conventional consumer goods have the authorities’ permission to operate. However … obtaining [such a permit] … is difficult due to high demand. The permit grants the right to transport certain products for a limited period. According to an article published by the Dutch Reporters Online, a porter operating with a permit is allowed to transport “legal products”, cross the border legally, provide health insurance for their family, and have the right to a pension. No further information was available on obtaining a permit, its granted rights, and its prevalence from the sources available.’[footnote 112]

8.3.5 The same FIS report also stated: ‘It is unclear how possessing a potential transport permit affects being targeted, as couriers travel over the mountains in large groups, making it difficult for Iranian border guards to ascertain from a distance who holds permits.’[footnote 113]

8.3.6 N.B. the information quoted below was originally published in Farsi. All COI from this source has been translated using a free online translation tool. As such 100% accuracy cannot be guaranteed.

An article published on 19 May 2025 by Borna News, a news agency ‘affiliated with the [Iranian] Sports and Youth Ministry and [which] carries reports on youth and sports-related topics’[footnote 114], stated:

‘According to Mohammad Jafar Ghaempanah, the Executive Vice President of the Islamic Republic of Iran, this year, more than 62,500 kulbars in Kermanshah province who are the heads of households can legally and officially participate in the import of goods from the borders of this province by receiving a kulbar card … [which] can bring about a dramatic change in economic dynamism, job creation, and improvement of household livelihoods on a regional scale.

‘… In addition to all the advantages, we must take a realistic look at the issue of border settlement and kulbars. Without the existence of a proper executive infrastructure, the kulbari card plan is likely to face challenges in the way of implementation. For example, fair allocation of cards, combating rents and possible corruption, careful monitoring of the import process, and preventing the conversion of the kulbari card into a commercial intermediary tool are among the issues that require precise and transparent policy-making.

‘… The government’s new plan to organize kulbars in Kermanshah province is not only an executive measure, but it can also be seen as a kind of redefinition of the government’s relationship with border dwellers, a revision of the view of borders, and an attempt to achieve social justice in the marginalized geography of the country.

‘If this policy continues with care, monitoring, and commitment, it can be hoped that Kermanshah and other border provinces will become the first line of development and partnership …’[footnote 115] As of August 2025, however, CPIT has been unable to substantiate how many, or whether any, such permits have been issued.

9. Law enforcement

9.1 Border control

9.1.1 On 28 April 2023, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a US-based global think tank that promotes international peace[footnote 116], published an article entitled ‘Border Crossings: The Unholy Alliance Between Iran and Iraqi Militias’ which stated: ‘The [Iran-Iraq border] crossings … lie along a 1,600-kilometer (994-mile) border … There are nine official crossings between Iraq and Iran … There are also unofficial crossings, generally controlled by pro-Iranian militias as well as criminal gangs, through which much smuggling occurs, particularly of weapons and drugs … Iran and the militias will continue to exercise significant control there for the foreseeable future.’[footnote 117]

9.1.2 On 13 March 2021, Spreading Justice, a database of human rights violations in Iran that was set up by Human Rights Activists (HRA, a human rights organisation focused on Iran[footnote 118]) in Iran[footnote 119], published an article which stated: ‘The Law Enforcement Command of the Islamic Republic of Iran (FARAJA), formerly known as the Law Enforcement Force of the Islamic Republic of Iran (NAJA), is one of the most pivotal institutions responsible for maintaining internal security and public order in Iran … Through its Border Guard Command, FARAJA ensures the security of Iran’s extensive land and maritime borders. This includes preventing illegal crossings, smuggling, and infiltration by terrorist groups.’[footnote 120]

9.1.3 An article published by the Institute for the Study of War (ISW), a ‘non-profit, public policy research organization’ which carries out research and analysis in conflict zones[footnote 121], on 17 June 2025 confirmed that the border guard remained a subordinate unit of the Law Enforcement Command (which it abbreviated to LEC)[footnote 122]. It also confirmed that the LEC remained ‘… the premier Iranian internal security and law enforcement service.’[footnote 123]

9.1.4 On 8 January 2025, an article published by Rudaw, a global media outlet based in Erbil, the Kurdish region of Iraq[footnote 124], stated:

‘The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) will deliver a “firm and decisive” response to any threats on its border areas, its commander [Mohammed Pakpour] said on Wednesday [8 January 2025] near the restive border with Iraq.

‘… The Kurdistan Region-Iran border is porous and there are numerous well-trodden smuggling routes.

‘In October 2023, Iraq installed a 200-kilometer-long security barrier along the border with Iran, equipped with over 150 thermal cameras, in an attempt to thwart smuggling operations and crack down on illegal crossings.’[footnote 125]

9.1.5 The Iran Focus article, published on 15 June 2024, stated: ‘According to the officials of the Iranian regime, smuggling of goods occurs not only through illegal borders but also through official gates … the Iranian regime and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) are considered some of the largest smugglers of drugs, oil, and other goods both inside and outside Iran.’[footnote 126] It should be noted that the Iran Focus article did not only refer to smuggling that occurred at the Iran-Iraq border, but also smuggling through Iran’s docks and airports.

9.1.6 The Tasnim News Agency article, published on 10 April 2025, stated:

‘Deputy Commander of Iran’s Law Enforcement Force Brigadier General Qassem Rezaei said joint patrols are being conducted on both sides of the Iran-Iraq border.

‘… He noted that Iraqi border guards are working closely with their Iranian counterparts in Kurdistan. Rezaei identified the Bashmaq border crossing as one of the most active and secure in the country. He also contrasted the current state of border security with previous years, referencing past unrest.

‘Rezaei said the current state of the country’s borders is not comparable to the era of the Ba’athists [a Pan-Arabist political party advocating for a single Arab socialist nation, which has previously ruled in Syria and Iraq[footnote 127]], when “due to sedition stirred by global arrogance, there was an exchange of artillery — but today, what we exchange is trade.”’[footnote 128] CPIT noted that the available evidence did not support Qassem Rezaei’s statement, about the exchanges at the Iran-Iraq border having become peaceful trade exchanges, see Excessive use of force.

9.2 Maps

9.2.1 NOTE: The maps in this subsection are not intended to reflect the UK Government’s views of any boundaries.

9.2.2 On 8 April 2019, the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC), a Swiss-based independent civil society organisation which focuses on global strategies against organised crime[footnote 129], published a report entitled ‘Sanctions and smuggling: Iraqi Kurdistan and Iran’s border economy’. The report included the below map, showing known smuggling points along the Iran-Iraq border[footnote 130]:

Map produced in the April 2019 GIATOC report showing smuggling points visited by the report’s author and other known smuggling points along the Iran-Iraq Kurdistan border

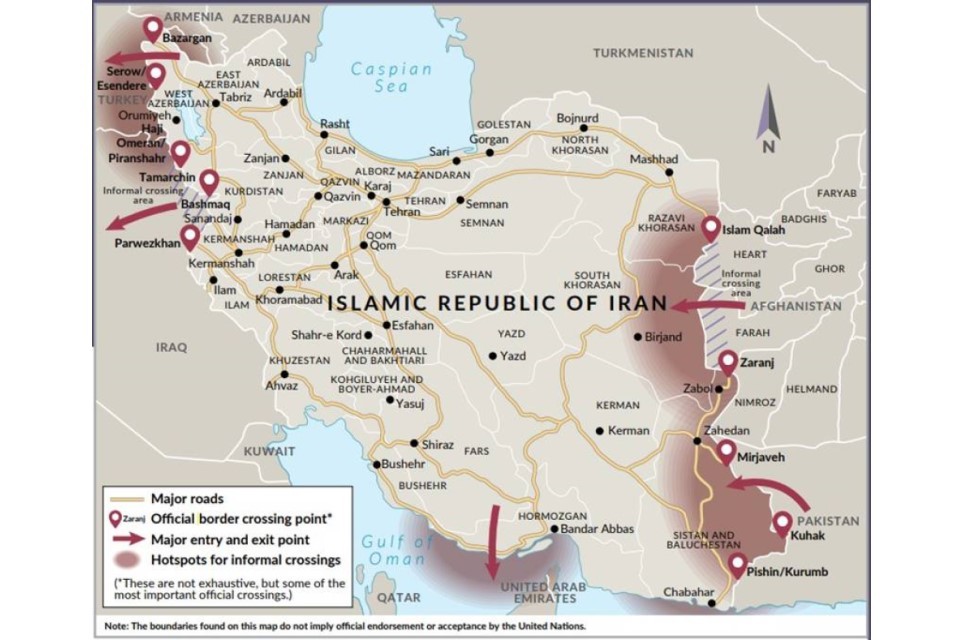

9.2.3 A further report about Iran’s illicit economies was published by GI-TOC on 19 October 2020, which included the below map, showing drug smuggling routes through Iran, including official border crossing points, major exit and entry points, and hotspots for informal crossings[footnote 131]:

Map produced in the October 2020 GIATOC report of the Iran-Iraq border, showing official border crossings, major points of entry and exit, and hotspots for informal crossings

9.2.4 CPIT was unable to verify that all of the information contained within the above maps remains current at the time of writing. However, CPIT was also unable to locate more recently published maps showing smuggling/border points within the sources consulted (see Bibliography).

9.3 Anti-smuggling operations

9.3.1 An article published by Rudaw on 6 May 2022 stated: ‘Iranian border guards have previously raided the houses of kolbars, confiscating their belongings.’[footnote 132]

9.3.2 On 17 October 2024, the EUAA published a query response on the human rights situation in Iran. The response, which cited various sources, stated: ‘In correspondence with EUAA [on 27 September 2024[footnote 133]], an expert on the Kurdish population and regions in Iran noted that “kolbars are targeted because they cross the border illegally and carry goods that are not taxed …”’[footnote 134]

9.3.3 The same EUAA query response also stated: ‘In correspondence with EUAA, an expert on the Kurdish population and regions in Iran noted that that “the border routes used by kolbars and sokhtbars [fuel carriers[footnote 135]] to transport goods or fuel are well-known to security forces, as they often travel in large numbers, sometimes in the hundreds or thousands. As a result, state security forces deliberately and knowingly target these individuals”.’[footnote 136]

9.3.4 The CSHR and KMMK-G report, published in July 2024, stated that smuggling ‘… is detectable at entry points or within Iran, including where goods are sold on the market.’[footnote 137]

9.3.5 On 13 May 2025, KolbarNews reported that:

‘… [O]n the afternoon of Tuesday, May 13, 2025, the border guards of the Islamic Republic raided the village of “Haji-Abdel” in Saqqez County and confiscated the loads carried by several Kolbars. According to the report, the border forces conducted searches of several houses in the village without a judicial warrant and seized multiple loads belonging to Kolbars, taking them away. As of the time this report was prepared, the identities of the Kolbars whose goods were confiscated and the exact quantity of the items remain unknown.’[footnote 138]

9.4 Treatment, arrest and detention

9.4.1 The FIS report, published in March 2024, stated:

‘There is no information available from Iranian authorities regarding the number of arrested kolbars, but the American magazine Outside estimated in an article about kolbars that, according to the kolbars themselves, thousands may be arrested each year.

‘… There is hardly any information available in the sources on the extent to which authorities may be seeking to locate and detain Kolbars outside of transport activities along the Iranian border, where … Iranian authorities have arbitrarily shot and detained Kolbars …’[footnote 139]

9.4.2 An article published on 8 August 2023 by the Iran Human Rights Society (IHRS), an organisation that reports on prison conditions and human rights violations across Iran[footnote 140], stated, of 8 kolbars who were injured on 6 August 2023 when security agents reportedly opened fire on them, killing one: ‘The injured Kolbarans did not go to medical centers in fear of arresting [sic].’[footnote 141]

9.4.3 The CSHR and KMMK-G report, published in July 2024, stated:

‘The issue of state-sponsored violence against kulbars, coupled with the prevalence of torture, constitutes a grave human rights crisis …

‘Kulbars often face mistreatment, including physical beatings and insults, when apprehended by border guards. These encounters, framed as efforts to curb smuggling, result in human rights violations and compromise the dignity of those engaged in kulbari.

‘… The treatment of kulbars by some border officials often goes beyond physical violence to include dehumanizing practices. This mistreatment can take the form of insults, verbal abuse and acts designed to humiliate individuals. Such behaviour not only constitutes a violation of basic human rights but also strips away the dignity of the kulbars. This degrading treatment exacerbates the challenges faced by kulbars, adding psychological and emotional abuse to their physical hardships …’[footnote 142]

9.4.4 The same CSHR and KMMK-G report also noted ‘… extortionate practices [are] faced by kulbars, including the requirement to pay bribes and the risk of having their goods confiscated or pack animals killed …’[footnote 143]

9.4.5 The CSHR and KMMK-G report went on to state:

‘According to a lawyer interviewee, when kulbars are detained, the conditions they face often raise serious human rights concerns. Detainees may be held in overcrowded and unsanitary facilities, which fall far below international standards for the treatment of prisoners. These conditions can amount to torture or inhumane treatment. The lack of access to basic necessities, such as adequate food, water and medical care, further contributes to the suffering of those in custody. These detention conditions highlight the broader issues of disregard for the wellbeing and rights of kulbars, compounding the already severe challenges they face in their daily work.

‘… The legal framework ostensibly in place to safeguard citizens frequently abandons kulbars, leaving them susceptible to capricious detentions, bereft of adherence to established legal protocols. This blatant indifference to due process rights, especially the right to a fair trial, exacerbates the vulnerability of kulbars to a spectrum of human rights abuses. The lack of legal protection signifies that kulbars may find themselves detained, interrogated and even subject to punitive measures without the means to contest the grounds of their detention or the conditions thereof.’[footnote 144]

9.4.6 The HRW article that was published on 8 July 2024 stated: ‘Iranian authorities have claimed that they have used force to stop smuggling but have also said they want to regulate the border couriers’ economic activities more broadly rather than violently repress it.’[footnote 145] CPIT has been unable to locate any evidence that the Iranian authorities have taken steps to regulate kolbars’ activities in the sources consulted (see Bibliography). See also Excessive use of force.