Lead Exposure in Children Surveillance System (LEICSS) annual report, 2024

Updated 22 December 2025

Applies to England

Executive summary

LEICSS is a national surveillance system coordinated by the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA). The surveillance system notifies the Health Protection Teams (HPTs) of incident cases of elevated blood lead concentration in children aged 0 to 15 years in England. Notification initiates health protection case management and public health interventions to remove exposure sources.

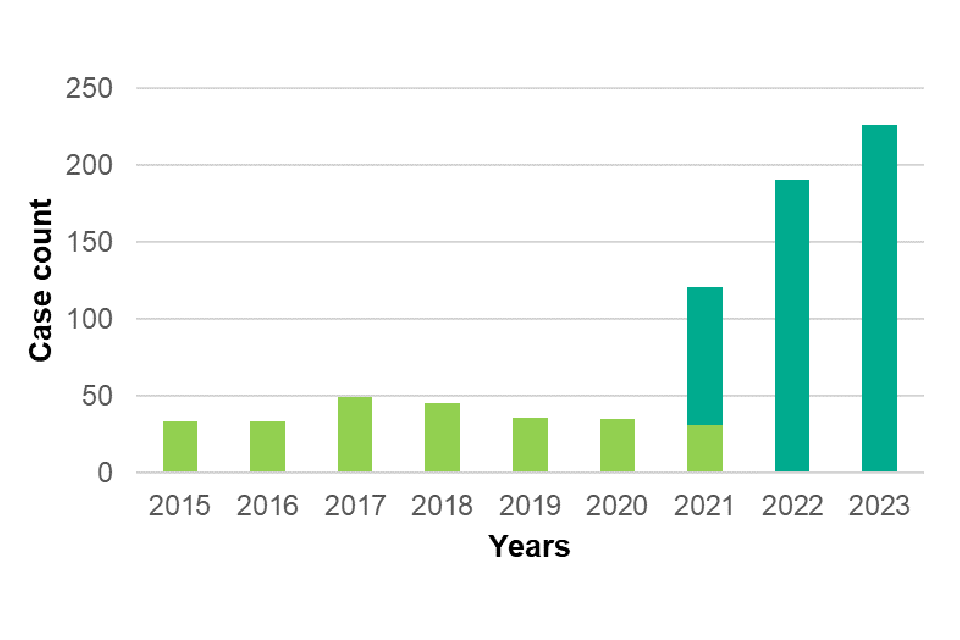

Following a review of the evidence of the harm of lead exposure in children (1,2), a UKHSA task and finish group recommended the lowering of the blood lead public health intervention contration for England. Since 5 July 2021, the case definition for surveillance changed to half the original concentration, from 0.48 μmol/L (equivalent to ≥10μg/dL) to 0.24μmol/L (equivalent to ≥5μg/dL). As expected, this led to a steep increase in the number of cases being reported to LEICSS.

This report summarises the surveillance of cases from 1 January to 31 December 2023 and gives an update on surveillance activities. For the first time, this report includes data collected from the Enhanced Surveillance Questionnaires (ESQ) conducted by HPTs as part of case management to gather information on potential risk factors and lead exposure sources. This year, the report also contains details of an incident involving lead exposure and case studies demonstrating how laboratories and HPTs have managed cases of elevated blood lead concentrations (BLC) in children.

Main findings

Main findings of this report are that:

-

a total of 226 cases were notified to UKHSA in 2023, an 18% increase compared to 191 in 2022; most cases (177, 78%) were directly notified to LEICSS by participating laboratories, with 49 (22%) notified by other routes, similar to previous years

-

the median delay between the specimen collection date and the date cases were entered onto HPZone (now CIMS) was 11 days (IQR 6 to 17 days), which is shorter than in 2022 (median 17 days, IQR 10 to 32). This suggests that case processing delays are reducing

-

as in previous years, cases were typically male (65%), 1 to 4 years of age (67%) and residing in the most deprived areas (48%). The median blood lead concentration of lab-detected cases was 0.39 μmol/L (8.07 µg/dL) in 2023, which is similar to 2022 (0.37 μmol/L, 7.66 µg/dL)

-

according to statistics from international population surveys, the number of cases reported to LEICSS are significantly lower than the estimated incidence of lead exposure in children in England (3,4,5)

-

in 2023, the detection rate per million for children aged 0 to 15 in England was 21 cases per million, although there were large regional variations. The highest reporting rates were from Yorkshire and the Humber region (75 per million), and the lowest in the East of England region (8 per million)

-

the most common exposures reported for cases (236 completed ESQs out of 507) from 2021 to 2023 were soil 157 (67%) and paint 103 (44%). Other reported sources include imported spices/food (32, 14%), traditional medicines and herbal remedies 19 (8%), and imported utensils, ceramic pottery and pewter 15 (6%). Additionally, 8 (3%) cases were potentially exposed due to a parent/guardian’s occupation, and 13 (6%) exposed though lead drinking-water pipes

-

most cases between 2021 and 2023 exhibited pica behaviour (194, 82%) and learning difficulties (162, 69%), as reported in the Enhanced Surveillance Questionnaires (ESQ). In 2023, 130 cases completed the ESQs, with 81% (106) reporting pica behaviour and 74% (96) experiencing learning difficulties

Main messages and recommendations

Lead is a persistent, heavy metal environmental contaminant that has an adverse effect on the body even at low BLC. Therefore, there is no known safe threshold for lead exposure. Children exhibiting pica (see note 1) or hand-to-mouth behaviour in environments with lead hazards are at the highest risk of exposure.

Clinicians should be aware of the risk of lead exposure for children, the main sources of lead exposure, children most at risk, presenting symptoms and signs of exposure. For more information on resources for public health professionals and clinicians, see Resources section of this report.

Cases who meet the case definition (aged under 16 years, BLC ≥5µg/dL or ≥0.24µmol/L) should be notified to UKHSA health protection teams for public health case management. Details of other requirements for notification are outlined in the Case Reporting to LEICSS section of this report.

Background

Whilst there is no defined safe threshold for the harmful effects of lead in children, in 2021, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) lowered the intervention level for lead in the blood from ≥0.24 µmol/L (≥5 µg/dL) to ≥0.17µmol/L (≥3.5 µg/dL) (6) and in the UK case definition of elevated BLC in children (<16 years) was halved from 0.48 µmol/L (10 µg/dL) to 0.24 µmol/L (5 µg/dL) in July 2021 (2). This change means that more affected children will receive needed public health case management and intervention.

Around 1 in 3 children (up to 800 million globally) have blood lead concentrations (BLC) at or above 5 µg/dL, which is the threshold at which many nations recommend taking clinical/public health action (5). There is no data estimating how many children in England are exposed to lead above this level. In other countries, such as the US and France, screening programmes have been set up to screen children aged 1 to 5 years and identify those with elevated BLCs. In 2018, the UK National Screening Committee conducted a review of evidence to determine the need for population screening. They did not recommend a systematic population screening program (7), due to concerns about testing and treatment, as well as the lack of current population prevalence data showing sufficient evidence of lead exposure being an important public health concern.

Survey data from comparable countries may be used for estimates of the prevalence of elevated blood lead concentration in England. A survey in France from 2008 to 2009 (see note 2) (4), estimated 1.5% of 1 to 6 year-olds had a BLC ≥0.24µmol/L (≥5µg/dL). In the USA, the estimated percentage was 2.6% for the same age group (6). Applying the US estimate to the UK population of 1 to 4 year-olds in England in 2023 (taken from ONS 2023 Census data) (8,9) suggests that approximately 64,780 children in England may have BLCs above the intervention level. Recent estimations by the Institute of Health Metrics (10), using the Global Burden of Disease tools, suggest that for the UK in 2019 there may be as many 213,702 (95% CI 186,000 to 281,500) children aged 0 to 19 years with a BLC of ≥0.24 µmol/L (≥5 µg/dL), and 29,036 (95% CI 25,000 to 42,500) children with BLC ≥0.48 µmol/L (≥10 µg/dL).

Exposure to lead can result in severe multi-system toxicity (1). How this toxicity manifests depends on both the BLC and how rapidly BLC rises. Overt manifestations of toxicity (that is, lead poisoning), such as anaemia or abdominal pain, accompany higher lead concentrations, for example, BLC>1.93 μmol/L (>30 µg/dL) (see note 3) (2,11). Lead exposures resulting in a lower BLC may not cause such apparent symptoms, but still cause harm, particularly to the central nervous system. There is no known safe blood lead concentration; even BLC as low as 0.17µmol/L (3.5 µg/dL) may be associated with decreased intelligence in children, behavioural difficulties and learning problems (12). Timely removal or abatement of the exposure source is the mainstay of case management, but symptomatic children, and children with BLC greater than 2.4 μmol/L (>50 µg/dL), may also require chelation therapy (11).

Since July 2018, primary prevention efforts aimed at reducing the use of lead in paints and fuels, regulating lead concentrations in drinking water and water supply pipes, remediating lead in soil, and controlling industrial emissions have been successful in reducing lead in the environment. This has resulted in lower exposure to lead, thereby reducing BLCs in children, as has been demonstrated in the USA (3). Nevertheless, lead is a persistent contaminant, and children can still be exposed to lead present in the environment as a result of historical usage. Since the removal of lead from petrol, ingestion rather than inhalation has been identified as the most common route of exposure in high income countries, particularly from dusts, soil and flakes of leaded paint (11). Leaded paint had wide domestic use in the UK before gradual withdrawal from the 1960s onwards (13) and was eventually banned from sale in 1992. A recent study (14), identified living in houses built before the 1970s, and terraced housing, as key risk factors for increased BLC in children in England.

Evidence from LEICSS has shown lead exposure routes in England include ingesting lead-contaminated water, soil, or dust, as well as herbal medicine preparations, contaminated food and spices, and use of consumer products that do not meet regulatory standards (such as painted toys, make-up and lead crystal glassware). Between 2014 and 2022 paint and soil were the most commonly reported sources of exposure for children in England (15). Children can also be exposed to lead through secondary exposure from parental hobbies or occupations, such as being in contact with lead dust on work clothing (11).

Children with learning and developmental disorders are at higher risk of exposure to lead due to increased mouthing or ‘pica’ behaviour, a condition involving ingestion of non-food items which may contain lead (paint flakes, soil, and so on) (16). Additionally, children already exposed to lead, even at very low concentrations, have been shown to have reduced learning capacity and increased prevalence of developmental disorders (12, 17). Iron deficiency can lead to increased susceptibility to lead toxicity and can also cause pica.

Cases of lead exposure are identified by means of a blood test to measure the BLC. Since the signs and symptoms of lead exposure are not specific, it can be easily overlooked and misdiagnosed in clinical settings. Case detection therefore depends on clinicians having a high level of clinical suspicion for lead poisoning symptoms as well as following clinical guidance for the management of pica. This requires a broad understanding of the child’s physical and mental development, socioeconomic background, and home/housing circumstances to identify factors that might increase the risk of lead exposure. Surveillance of cases identified by clinicians provides valuable information to guide public health case management and inform population preventive action.

The Lead Exposure in Children Surveillance System (LEICSS)

UKHSA coordinates LEICSS, a national surveillance system for children residing in England. Formal surveillance of lead exposure in children in England was initiated in 2010 by the Surveillance of elevated blood Lead in Children (SLiC) study, a joint research project between the British Paediatric Surveillance Unit and the Health Protection Agency (the forebear to PHE, now UKHSA). The SLiC study authors recommended implementation of a laboratory-based surveillance system in order to facilitate timely public health management of cases of lead poisoning in children (18). A pilot system, the Lead Poisoning in Children (LPIC) surveillance system, was therefore instigated in 2014 and permanently implemented as LEICSS in 2016 following successful evaluation of the pilot. In December 2021, LEICSS was incorporated into a UKHSA Lead Exposure, Public Health Intervention and Surveillance group (LEPHIS) to recognise the broader aims of prevention of lead exposure in children, in addition to the rapid recognition of cases of lead poisoning.

The aims and development of LEPHIS are overseen by a UKHSA cross-department working group and an external steering group with additional representatives from participating laboratories, academia, NHS clinical toxicology and patient representative groups (for example, Lead Exposure and Poisoning Prevention (LEAPP) Alliance) (see Steering and Working Group Members at the end of this report).

The data collected from LEICSS feeds into the Environmental Public Health Surveillance System (EPHSS) for England operated by UKHSA as part of the Environmental Public Health Tracking programme and the steering group and working group report to the UKHSA Environmental Public Health Tracking Board.

LEICSS aims are:

- To facilitate timely public health action for individual cases, as the mainstay of treatment for cases of lead exposure is rapid removal of the putative source of exposure.

- To meet population level surveillance objectives, to inform public health action that reduces the incidence of lead exposure in children in England, such as identification of geographic areas or populations at risk, and identification of current and emerging sources of exposure.

Case reporting to LEICSS

LEICSS is a passive surveillance system that integrates reports of incident (newly detected) cases of lead exposure notified to UKHSA from a variety of sources.

Since 5 July 2021, a case is defined as a child:

- with a blood lead concentration ≥0.24 μmol/L (equivalent to ≥5 μg/dL), as detected in a UK Accreditation Service (UKAS) accredited biochemistry or toxicology laboratory

- reported to UKHSA for public health intervention

- aged under 16 years at the time of first elevated blood lead concentration

- resident in England

The surveillance system collates cases reported:

- To LEICSS directly from a UK Accreditation Service (UKAS) accredited testing biochemistry or toxicology laboratory.

- To a local UKHSA Health Protection Team (HPT) from a non-UKHSA source (for example, the managing clinician or an environmental health officer) (see note 4), and recorded on the UKHSA case management system (formerly HPZone, now CIMS) (see note 5).

- To another UKHSA Directorate (for example, the Radiation, Chemicals and Environmental Hazards Directorate) and then referred to an HPT.

Case notification to UKHSA is voluntary but encouraged for efficient lead case management and surveillance purposes.

Direct reporting to LEICSS from biochemistry and toxicology laboratories

A group of highly specialised diagnostic laboratories, the SAS Trace Elements network, provide a referral network for specialised laboratory investigations in the UK. BLC is measured in six SAS Trace Elements laboratories in England, and it is estimated they perform the vast majority of such tests nationally. All six SAS laboratories participate in LEICSS, and a partnership between the SAS-associate laboratory in Wales (Cardiff Toxicology Laboratory) has been developed to alert LEICSS of England residents whose BLC may be determined in Cardiff. Other, non-SAS but UKAS accredited laboratories have also agreed to report cases to LEICSS; these are typically located in larger NHS Trusts or are private laboratories. All contributing laboratories are named in the Acknowledgements section of this report.

Reports of cases meeting the following case definition are referred to as ‘laboratory-detected’ cases.

LEICSS surveillance staff enter case details onto the UKHSA HPZone case management system (now known as CIMS) following notification. The relevant local HPT is then alerted to investigate and manage the case. This route of notification to the investigating HPT has been found to be timelier than waiting for notification from other sources involved in treating the case; for example, the managing clinician (19).

Health Protection Team (HPT) notified cases

HPT cases are those that are or were:

- notified directly to a health protection team in England for public health management and classified on the HPT case management system as ‘toxic exposure to lead’

- aged under 16 years at the time of notification to the health protection team

- resident in England

- not initially notified to LEICSS by a participating biochemistry/toxicology laboratory

Blood lead concentration data for cases notified by non-laboratory sources is not routinely recorded on the HPT case management system in a way that makes it readily extractable for analyses by LEICSS . Thus, an HPT notified case may potentially have a BLC <5µg/dL (<0.24 µmol/L) or may be missing BLC data.

UKHSA notified cases

Occasionally cases may be initially identified by other departments (such as RCE) before they are notified to the HPT. For example, this may occur as a result of a wider lead exposure incident on which RCE is leading. These cases will also be entered onto the HPT case management system and can be extracted in the same way as HPT notified cases.

Public health management of cases

Once notified to a local HPT, lead exposure cases are assigned to a lead clinician who uses UKHSA national guidance (20) to manage the case(s). The actions taken vary according to the initial BLC notified but in general are aimed at supporting the family of the case, the clinical team and other relevant stakeholders (for example, UKHSA’s Environmental Hazards and Emergencies department, local authority Environmental Health and Public Health and Housing departments) to identify the source of the lead and help mitigate the exposure by the most effective means.

Surveillance data for 2023

This section provides a summary of cases of blood lead exposure in children residing in England, reported to HPTs during 1 January to 31 December 2023. In this report, the 2023 metrics were compared to the 2015 to 2022 data, 8-year average, where relevant, using data from cases reported between 1 January to 31 December for each of these years.

Figures are correct at the time of publication and may be subject to change as new information about cases becomes available.

This report, and previous years’ annual reports since 2021 are available at Lead exposure in children: surveillance reports. For reports published before 2021 Lead Exposure in Children Surveillance System: Surveillance Reports published before 2021

Number of incident cases

A total of 261 reports of elevated BLC in children were notified to LEICSS in 2023. Of these, 226 (86%) met the case definition (reports of BLC <0.24μmol/L are not included) (see note 6). Figure 1 shows the number of cases, by year, from 2015.

Seventy-eight per cent of cases were direct laboratory reports to LEICSS, with 22% from other reporting routes (direct to HPTs, etc) (see Table 1).

Table 1. Count and percentage of LEICSS cases, England 2023, compared to 2015 to 2022

| Route of detection by LEICSS | Count of cases 2023 (% of total) | Count of cases 2015 to 2022 (% of total) |

|---|---|---|

| Direct laboratory reports | 177 (78) | 440 (79) |

| Other Routes (HPZone search) | 49 (22) | 117 (21) |

| Total | 226 | 557 |

Figure 1. Count of LEICSS cases per year (England): 2015 to 2023

Note: The darker green bar in 2021, 2022 and 2023 denotes the number of cases, post-case definition change

Timeliness of reporting of laboratory-detected cases to LEICSS and notification to Health Protection Teams

For laboratory reported cases, the median delay between the date of specimen collection and the date the case was entered onto HPZone (as a proxy for the date of report to HPTs) was 11 days, with a wide inter-quartile range (IQR) of 6 to 17 days, which is lower than the reported average for previous years (17 days; IQR 10 to 32). The median days delay this year (11 days) has decreased compared to last year (17 days), indicating that case processing delays are reducing (Table 2).

Table 2. Time between specimen collection and entry of case onto HPZone (for case management) for laboratory-detected LEICSS cases (England): 2015 to 2023

| Year | Direct lab- detected cases | Cases with valid data* (%) | Median days delay | IQR** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 177 | 166 (94) | 11 | 6 to 17 |

| 2022 | 160 | 159 (99) | 17 | 10 to 32 |

| 2021*** | 86 | 80 (93) | 11 | 8 to 15 |

| 2020 | 21 | 20 (99) | 17.5 | 10 to 30 |

| 2019 | 30 | 28 (93) | 8 | 7 to 14 |

| 2018 | 34 | 31 (91) | 8 | 6 to 13 |

| 2015 to 2017 | 91 | 82 (90) | 9 | 7 to 14 |

*Cases where both a valid specimen date and a valid date of entry onto to HPZone were extracted from HPZone.

**IQR = Inter quartile range.

***Case definition changed.

Occurrence and trends of cases of lead exposure in children

Count and detection rate (by LEICSS) of cases by regions and year

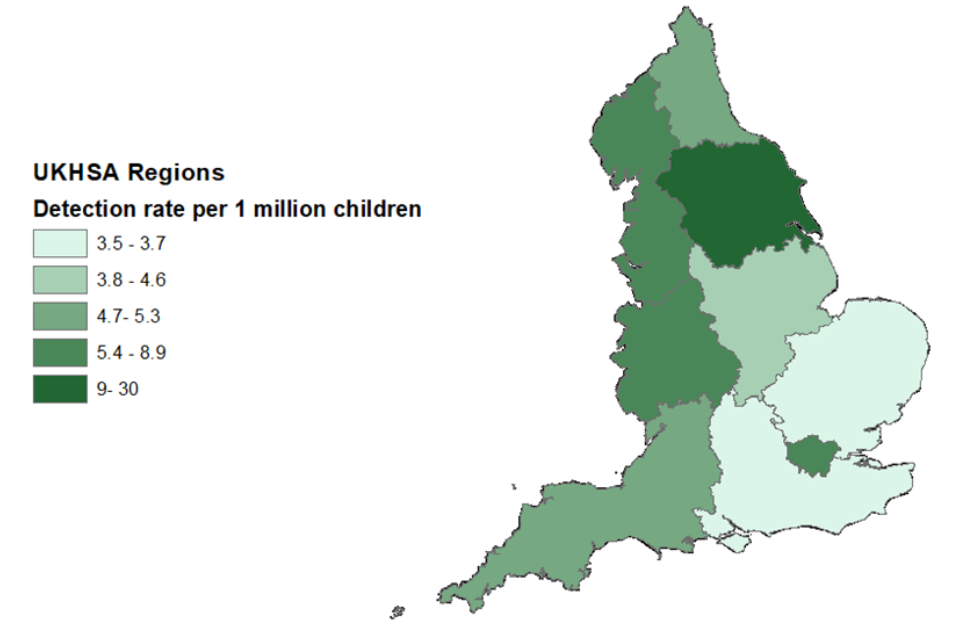

There was an increase in cases in 2023 compared with previous years (see Figure 2 and Table 3). The detection rate of LEICSS cases in 2023 (21 per million) has increased compared to 2022 (18 per million), while the highest reporting rates continue to be from the Yorkshire and the Humber region (75 per million). This year the lowest rate is in East of England region (8 per million). The percentage increase in case reporting from 2022 to 2023 was on average 18% for England (Table 3).

Figure 2. Graph showing detection rate of LEICSS cases per regional population of 0 to 15 year olds, per million, 2015 to 2023, England

*Centres where an SAS laboratory that participates in the surveillance system is situated; 2023 mid-year population estimate (MYE) was used as the denominator for each year (9).

Table 3. Count (and % of total) of LEICSS cases, percentage change from 2022 to 2023, and average detection rate† of cases (per million 0 to 15-year-old children) by Region and year of notification, England 2015 to 2023

| Region | Cases 2015 (%) | Cases 2016 (%) | Cases 2017 (%) | Cases 2018 (%) | Cases 2019 (%) | Cases 2020 (%) | Cases 2021 (%) | Cases 2022 (%) | Cases 2023 (%) | Cases 2105 to 2023 (%) | % change in cases from 2022 to 2023 | Average detection rate‡ of cases (per million per year) 2015 to 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South East* | 6 (18) | 0 (0) | 4 (8) | 3 (7) |

1 (3) |

0 (0) | 7 (6) |

10 (5) | 23 (10) | 54 (7) | 130% | 3.53 |

| London* | 5 (15) |

7 (21) | 10 (20) | 12 (27) | 11 (31) | 4 (11) | 20 (17) | 24 (12) | 30 (13) | 123 (16) | 25% | 7.7 |

| South West | 2 (6) |

0 (0) | 2 (4) | 4 (9) | 2 (6) | 3 (9) | 9 (7) | 9 (5) | 16 (7) | 47 (6) | 78% | 5.35 |

| West Midlands* | 2 (6) |

3 (9) | 3 (6) | 4 (9) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 11 (9) | 38 (20) | 30 (13) | 93 (12) | -21% | 8.96 |

| East Midlands | 1 (3) |

0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (7) |

1 (3) |

3 (9) | 0 (0) | 10 (5) | 13 (6) | 31 (4) | 30% | 3.88 |

| North West | 4 (12) |

6 (18) | 11 (22) | 3 (7) |

4 (11) | 5 (14) | 11 (9) | 26 (14) | 18 (8) | 88 (12) | -31% | 7.03 |

| North East | 1 (3) |

0 (0) | 1 (2) |

0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 5 (4) | 3 (2) | 8 (4) | 20 (3) | 167% | 4.71 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber* | 9 (27) |

12 (36) | 16 (33) | 12 (27) | 14 (38) | 12 (34) | 54 (45) | 65 (34) | 78 (35) | 272 (35) | 20% | 29.23 |

| East of England | 3 (9) |

5 (15) | 2 (4) | 4 (9) | 3 (8) | 4 (11) | 4 (3) | 6 (3) | 10 (4) | 41 (5) | 67% | 3.69 |

| England | 33 | 33 | 49 | 45 | 36 | 35 | 121 | 191 | 226 | 769 | 18% | 8.05 |

†Should not be interpreted as an estimate of incidence – see ‘The case detection rate and ascertainment’ section of this report.

‡The numerator for this indicator is incident cases from 2015 to 2023, and the denominator is the ONS mid-year estimate of the 0 to 15 year-old population from 2015 to 2023. Cases allocated to UKHSA Centre according to postcode of residence.

*Centres where participating SAS laboratories are situated.

Figure 3. Average detection rate† of LEICSS cases (per million 0 to 15 year-old children) by Region, England 2015 to 2023

† Should not be interpreted as an estimate of incidence – see ‘The case detection rate and ascertainment’ section below.

The case detection rate and ascertainment

Due to the lack of specific symptoms at BLC below 1.93μmol/L (<40µg/dL), surveillance of clinically reported cases is likely to underestimate the number of affected children. International population surveys, which provide a more precise estimate of the number of children exposed to lead, indicate that there should be more cases of paediatric lead exposure than are identified by LEICSS (3,4,5,21) The figures above should not therefore be considered representative of the incidence of child lead exposure in England.

The large variance seen between regions in LEICSS data has likely resulted from bias in case ascertainment rather than reflection of incidence/prevalence. The Leeds SAS laboratory (located in Yorkshire and Humber) system actively encourages clinicians to test for lead exposure in children being tested for iron deficiency and when the child is also known to have pica behaviour (22), contributes to the reporting bias in this region where a 90% increase in testing and case reporting has been observed since implementation. This laboratory also actively involves local clinicians demonstrating that clinician awareness and testing frequency have a significant impact on case detection by the surveillance system. Although it is expected that SAS labs conduct the majority of BLC tests in children in England, testing in laboratories that do not submit cases to LEICSS may also contribute to the regional difference in case ascertainment.

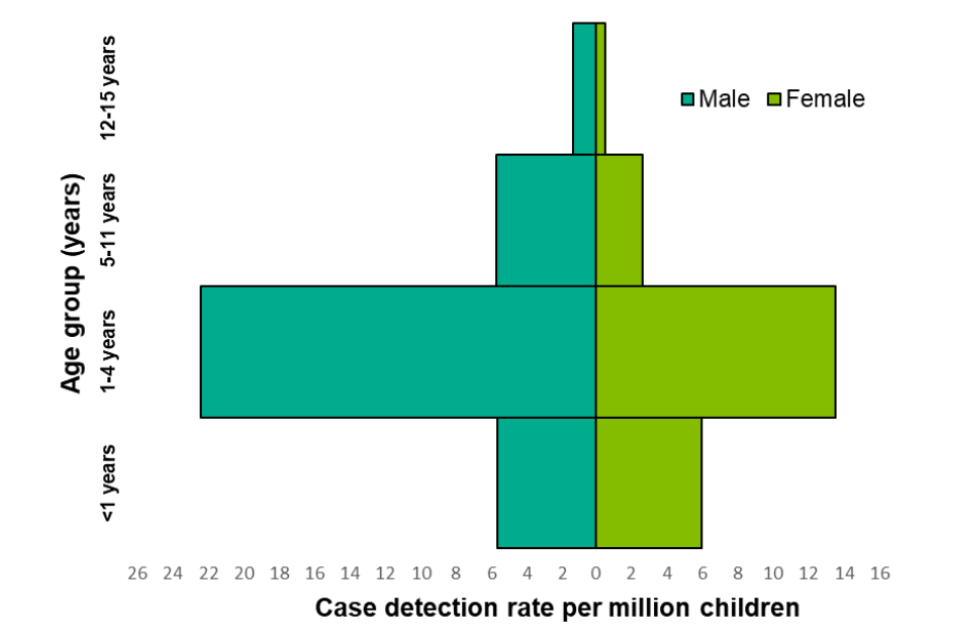

Count and detection rate of cases by gender and age

The higher proportion of cases in 2023 were male (n=148, 65%), similar to previous years (n=349, 64%) (Table 4) and this was seen across all age groups (Figure 4). This gender disparity is reflected in the literature (6,7,14,15,21) and may indicate a pre-disposition of specific high-risk behaviours in males or higher risk/prevalence of comorbidities in young males. This heightened risk of lead exposure may be linked to conditions like autism (associated with pica (23) being more prevalent in males than females (ratio is 3:1) (22).

The highest case detection rate was in children aged 1 to 4 years old, for both males and females (Figure 4). 152 cases (67%) identified in 2023 were in this age group, similar to the 2015 to 2022 period with 362 (67%) cases (Table 4). Fewer cases were aged between 5 to 11 years (n=52, 23%) and under 1 year old (n=16, 7%), while only 6 cases (3%) were in the oldest age group (12 to 15 years old). Since lead exposure in children is most likely to occur through ingestion of lead-containing substances (especially from deteriorating paint work), the high percentage of cases in pre-school age children likely indicates a greater vulnerability to lead exposure due to mouthing behaviours (3). Additionally, developmental delay may become more evident at this age group, and autism symptoms may also become more apparent, which could result in more investigations for these children.

Table 4. Count and percentage of LEICSS cases by age group and sex in England, 2023, and 2015 to 2022

| Age group | Male (%) 2023 | Female (%) 2023 | Unknown (%) 2023 |

Male (%) 2015 to 2022 | Female (%) 2015 to 2022 |

Unknown (%) 2015 to 2022 |

Cases (%) 2023 | Cases (%) 2015 to 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 1 year | 7 (5) |

9 (12) |

0 (0) |

12 (3) |

10 (5) |

0 (0) |

16 (7) |

22 (4) |

| 1 to 4 years | 97 65) |

52 (71) |

3 (75) |

224 (64) |

135 (73) |

3 (38) |

152 (67) |

362 (67) |

| 5 to 11 years | 40 (27) |

12 (16) |

0 (0) |

99 (29) |

34 (19) |

5 (62) |

52 (23) |

138 (25) |

| 12 to 15 years | 4 (3) |

1 (1) |

1 (25) |

14 (4) |

6 (3) |

0 (0) |

6 (3) |

20 (4) |

| Total | 148 (65) |

74 (33) |

4 (2) |

349 (64) |

185 (34) |

8 (1) |

226 | 542 |

*Age of child at date of entry onto HPZone (now CIMS).

Figure 4. Average case age* and gender-specific detection rate† per million 0 to 15 year old children per year, England 2015 to 2023 (n=756)

*Age of child at date of entry onto HPZone (now CIMS).

† The numerator for this indicator is the count of age-gender specific incident cases in 2015 to 2023, and the denominator is the mid-year estimate of the age-gender specific 0 to 15 year old population from 2015 to 2023 (9).

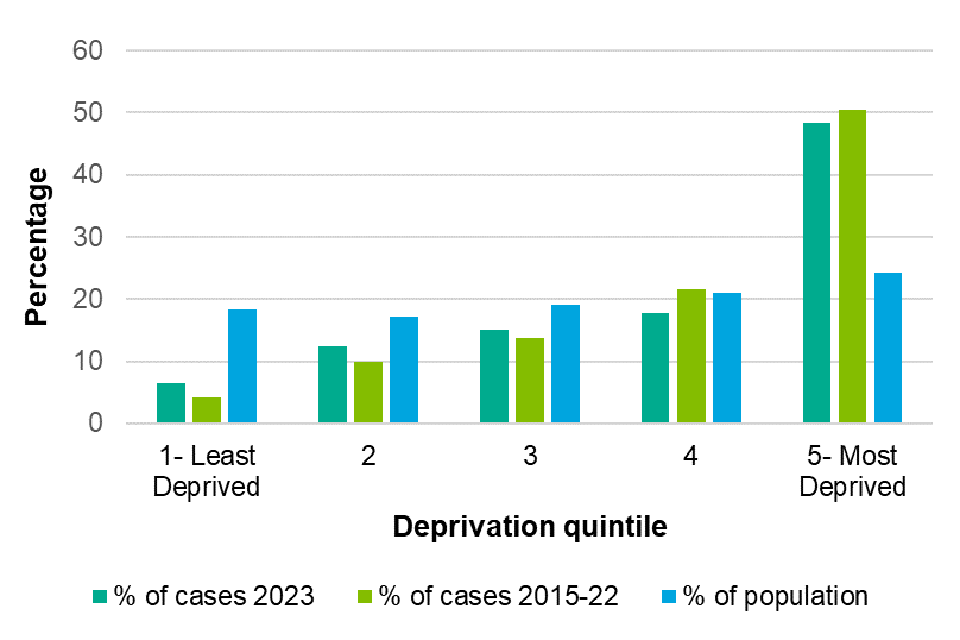

Percentage of cases by quintile of index of multiple deprivation (IMD) status

IMD provides a measure of deprivation, evaluated across seven domains (see note 7), summarised at the area-level. Sixty-six per cent of cases (n=148) in 2023 lived in areas in the two most deprived quintiles of IMD, similar to the previous 8-year average (70%) (Figure 5). This is higher than expected given that 45% of the young population reside in areas falling within these two quintiles (Fgure 6). Just under half (48%) of 2023 cases lived in the most deprived areas (Q5). These findings are consistent with patterns of lead exposure by socioeconomic status in US national survey data (12). Possible explanations include increased exposure to lead-containing hazards, such as older housing (6, 14), or a greater frequency of co-morbidity conditions (such as iron deficiency anaemia, autism and learning difficulties), Children of ethnic minority origin may be disproportionately affected as they are more likely to be housed in deprived areas (24); however, this cannot be evaluated in the LEICSS dataset because of insufficient ethnicity data (15, 25).

Figure 5. Percentage of LEICSS cases in each quintile of index of multiple deprivation¥, England 2023 and 2015 to 2022, for 0 to 15 year-olds

¥ Index of multiple deprivation (IMD) assigned to the Lower-level Super Output Area of the cases’s postcode, using IMD scores from 2019.

Blood lead concentrations of laboratory-detected cases

The mean blood lead concentration (BLC) for 2023 was 0.55 μmol/L (11.3 µg/dL), similar to 2022 with 0.61 µmol/L (12.6 µg/dL). The median BLC in 2023 was 0.39 μmol/L (8.07 µg/dL), much lower than the 2015 to 2020 median of 0.61 μmol/L (12.6 µg/dL) (Table 5). This was expected following the lowering of the public health intervention BLC and consequent change in case definition in 2021. However, although the majority of cases notified in 2023 were in the 0.24 to <0.48 µmol/L range (n=138, 53%), the number of children notified with BLC ≥0.48 µmol/L (n=88) was higher than in 2022 (n=72) and is consistent with a continued increase in cases notified to LEICSS each year. This indicates that other factors than the lowering of the public health intervention concentration from 10 µg/dL to 5 µg/dL were responsible, for example improved clinical awareness.

Seventy two percent (data not shown) of blood lead concentrations were below 1.45 μmol/L (<30 µg/dL) in 2015 to 2023, a concentration below which children would most likely be asymptomatic, or present with non-specific neuro-behavioural clinical manifestations (6), indicating these children were detected based on a high index of clinical suspicion. Table 6 shows the distribution of BLC recorded for the cases in 2023, compared with previous years.

Table 5. Blood lead concentration (μmol/L) from laboratory detected LEICSS cases, England, 2023, compared to 2022 and 2015 to 2021*

| Year | Lab detected cases (total cases) | Minimum | Maximum | Median | Lower Quartile | Upper Quartile | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023* | 177 (226) | 0.24 | 5.1 | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0.53 | 0.55 |

| 2022* | 160 (191) | 0.24 | 4.03 | 0.37 | 0.29 | 0.66 | 0.61 |

| 2015 to 2021 | 266 (352) | 0.1 | 17.59 | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.93 | 0.85 |

*Only children with a BLC≥0.24 μmol/L were eligible for notification to LEICSS.

Table 6. Summary of blood lead concentrations reported to LEICSS in England for 2023, 2022, and 2015 to 2021*

| Year | BLC <0.24 µmol/L (%)** | BLC 0.24 to <0.48µmol/L (%) | BLC ≥0.48 µmol/L(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2023* | 35 (13) | 138 (53) | 88 (34) |

| 2022* | 21 (10) | 119 (56) | 72 (34) |

| 2015 to 2021 | 18 (6)** | 60 (19) | 242 (75) |

*Only children with a BLC ≥24 μmol/L (equivalent to ≥5 μg/dL) were eligible.

**There are often reports of children with BLC below the reporting threshold from labs and other sources.

Duration of case investigation

Of the cases where the investigation had been concluded by the time of data extraction for this report (89%), the median duration of the investigation in 2023 was 11 weeks, higher than 2022 (7 weeks), and higher than the median for 2015 to 2022 (10 weeks, see Table 7).

Table 7. Duration, in weeks, of the public health investigation of LEICSS cases* reported to the surveillance system, England, 2023, and 2015 to 2022

| Year | Closed cases/total cases (%) | Median duration (weeks)* (LQ-UQ)** |

|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 202 out of 226 (89) | 11 (3 to 20) |

| 2015 to 2022 | 489 out of 543 (90) | 10 (3 to 22) |

*Period between date entered onto HPZone and date case closed on HPZone; cases must have been closed at date of data extraction from HPZone in January 2023.

** LQ = lower quartile; UQ = upper quartile.

Children whose death was attributed to lead exposure

One child’s death occurred in 2015; a case report demonstrating the death of the 2-year-old child, with pica and iron deficiency, who had ingested lead-containing paint and had acute lead toxicity has been published (15). The delay in diagnosis and subsequent death of the child were attributed to clinicians’ ignorance of the link between lead exposure and pica (22). Historical data has shown deaths from lead exposure in children to be very infrequent in England (23,26).

Incidents involving lead exposure in children

A significant public health incident that occurred in 2022, managed by West Midlands HPT, is summarised below.

In 2022, cases of lead poisoning were identified in a number of staff working at a firing range in Walsall (West Midlands) (27). Further investigation identified prolonged exposure of staff to lead containing dust, with 87 individuals being identified as potentially exposed at the firing range or via their close household contacts. Of these, consent was obtained for BLC determination in 63 patients aged between 6 months and 78 years old. Lead poisoning was confirmed in many of those exposed with the highest BLC reported as 11.7 µmol/L (242 µg/dL). While 15 patients received lead chelation therapy, only 9 reported symptoms during the investigation (27). Children were exposed via their parents, due to dust transfer to vehicles and clothing. The incident contributed to the increase in LEICSS case notification in the West Midlands region in 2022.

System developments

Progress on developing surveillance of lead cases has continued in 2023. To reflect the multi-disciplinary nature of managing lead exposures, sources, interventions and clinical management, the governance of the UKHSA working group has been updated. The new Lead Exposure Public Health Interventions and Surveillance (LEPHIS) Working Group now meets regularly to oversee co-ordination of surveillance, intervention work and raising awareness of lead hazards.

Invitation of further laboratories to participate in surveillance

We continue to invite laboratories in the UK National External Quality Assessment Scheme for Trace Elements (which includes measurement of blood lead concentration) to participate in case reporting to LEICSS. Presentations to the Association of Clinical Biochemists (ACB) and other interested parties on the work of LEICSS raise awareness of reporting by laboratories and have resulted in the recruitment of more laboratories participating in surveillance. Contact epht@ukhsa.gov.uk for more information.

Alerts for testing for blood lead concentrations in children

Introduction of an alert on the electronic test request system by Leeds SAS laboratory to encourage clinicians to consider testing for blood lead (for those children suspected of pica/iron deficiency) increased test requests by 90% in 2017. We supported laboratories to explore the feasibility of implementation of a similar model across the SAS laboratory network but unfortunately due to the diversity of information systems being used, a standardised alerting system is not feasible to implement at this time. However, discussion with laboratories is underway to amend the text on blood lead reporting to include better information on expected BLC in line with Leeds SAS laboratory reporting.

Enhanced Surveillance Questionnaire (ESQ)

The ESQ is an e-questionnaire that is utilised to support the HPT risk assessment by gathering information on potential exposures such as a history of pica, history of learning difficulties, occupational status of guardian/s, home age and ownership, etc. The electronic questionnaire was introduced to practice with the lowering of the intervention concentration in July 2021. The ESQ helps to scope in and out potential sources of lead for case management. We can summarise the findings from the ESQ to show the frequency of sources of lead exposure for cases.

A paper was published earlier this year that described sources of lead exposure for cases (15). An audit of cases was performed by a look-back questionnaire distributed to all HPTs that had reported LEICSS cases between 2014 and 2022. The ESQ was also used to explore sources for cases reported from July 2021 to December 2023 inclusive. The results identified that most of the cases were exposed in domestic settings (92%) and the most common sources of lead exposure were paint (43%) and soil (29%). Other less frequently recorded sources were drinking water/pipes, food (including spices), traditional medicines, ceramics, and cosmetics.

Following on from this work, more recent ESQ findings have been included in this annual report for the first time. Table 8 summarises the ESQ data for cases reported in 2021 to 2023 inclusive, compared to the published study (15). The results compare well, with 43 to 44% of cases being exposed through paint sources. More recent cases were reportedly exposed through soil sources (67% in 2021 to 2023 cases) than the previous study (29%). The proportion exposed through imported spices or foods has doubled in recent years (from 6% to 14%). Other significant sources include traditional medicines and imported utensils, ceramic pottery and pewter products.

The ESQ also captures any history of pica behaviour and diagnosed learning difficulty. ESQs conducted between July 2021 and December 2023 (236 out of 507 LEICSS cases), most cases (194, 82%) reported pica behaviour and learning difficulties (162, 69%). These percentages were similar across the 3 years of data. This may indicate that clinicians are aware that children at highest risk of exposure are those exhibiting pica or more hand to mouth behaviour and/or with learning difficulties. However, without reliable population estimates of the prevalence of pica and of elevated blood lead in children, these data must be interpreted with caution.

Table 8. Reported exposure sources for cases found from case management follow up

| Years in which cases were reported | Number of cases with a completed ESQ or look-back questionnaire, out of total cases* (%) | Paint source (%) | Soil source (%) | Imported spices or food (%) | Traditional medicines (%) | Imported utensils; ceramic pottery/pewter (%) | Workplace exposure from parents and guardians (%) | Drinking water and/or leaded pipe sources (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 to 2023* | 236 out of 507 (47%) |

103 (44%) |

157 (67%) |

32 (14%) |

19 (8%) |

15 (6%) |

8 (3%) |

13 (6%) |

| 2015 to 2022** | 347 out of 542 (64%) |

150 (43%) |

103 (29%) |

20 (6%) |

14 (4%) |

7 (2%) |

3 (1%) |

19 (5%) |

*Data obtained from the ESQ; this includes cases reported from July 2021 to December 2023. Case management requires cases with a BLC ≥0.48 μmol/L (equivalent to ≥10 μg/dL) to complete an ESQ; occasionally this is completed for cases below this value.

**Data obtained from an audit of historical cases, via both a look back questionnaire and the ESQ (15).

UKHSA’s Environmental Public Health Surveillance System

The Environmental Public Health Surveillance System (EPHSS) collates and integrates data from selected databases on environmental hazards, exposures, and health outcome data. Further details of the system are available at: Environmental public health surveillance system (EPHSS).

A LEICSS module incorporated into EPHSS allows for anonymised aggregated LEICSS data to be interrogated and analysed, producing user-defined outputs for surveillance reporting purposes. Currently, the EPHSS platform is only available to UKHSA staff but the intention is to make it accessible to external users. Data up until June 2024 has been uploaded to EPHSS, so authorised users can pull reports on data from 2014 to 2024 inclusive. The aim is to upload data on LEICSS cases to EPHSS on a quarterly basis.

To gain access to LEICSS outputs via EPHSS, email to: ephss@ukhsa.gov.uk

Current and future activities

-

The LEPHIS Steering Group was surveyed to review existing priorities and propose additional priorities for lead exposure research and practice in 2024. Members were asked to rank research and operational activities in terms of importance. Priority topics identified included: undertaking a prevalence study of lead levels in the national child population, evaluation of the effectiveness of the current case management processes; developing case management advice; awareness raising activities and creation of a prevention subgroup to steer prevention activities.

-

In April 2023, the LEPHIS group in collaboration with national HPTs hosted a workshop to raise awareness of lead exposure in UKHSA health protection teams and to gain feedback on how to support HPTs in case management. Feedback from this workshop has informed LEPHIS priority planning and will be used to update SOPs and the HPT exposure survey questionnaire.

-

A group of LEPHIS Steering Group members have written a research proposal to determine the prevalence of elevated blood lead in a nationally representative sample in children in England. The Elevated Child Lead Interagency Prevalence Study (ECLIPS) study is led by the University of Northumberland and has obtained funding from the UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) for a protocol development feasibility study and pilot study to design and test methods, to begin November 2024.

-

The Environmental Hazards and Emergencies Department of UKHSA has collaborated with members of UKHSA HPTs to produce a suite of documents and standardised letters to support child lead case management. This is available to practitioners through the UKHSA internal duty doctors’ pack resource. New public facing web pages on .gov.uk will summarise this guidance (28).

-

The Environmental Epidemiology Team at UKHSA are exploring exposure source data including hazard maps for risk factors such as soil lead concentrations, housing age and index of multiple deprivation to aid development of a geographical lead exposure model. The first research output from this project was a paper on housing characteristics of cases (14) that identified vulnerable populations and a second publication on sources and outcomes for cases was also recently published (15).

-

An internal evaluation of the LEICSS was conducted in 2023 by a UKHSA Field Epidemiology Training Programme Fellow. This assessment supported previous evaluations demonstrating LEICSS’s value for initiating timely case management by HPTs and identifying key complexities in case management. Recommendations to improve case management and reduce the burden on case investigators were developed and incorporated into the LEICSS activity plan.

-

UKHSA is working with the Georgian National Centre for Disease Control on a research project to identify sources of lead exposure in children. Lead isotope analysis is being used to match blood lead and environmental lead isotopes in spices, food, milk, water, soil, dust, and toys as part of a national prevalence study. The study has so far identified spices to be a significant source of lead ingestion and a significant decline in BLC occurred in children after intervention(29,30,31). Further work is in progress including testing of a representative proportion of children in a region that previously reported the second highest BLC and incidences of threshold exceedance. This is helping to develop sampling and testing protocols for use in cases in England and is establishing these capabilities in Georgia.

-

Papers and reports (as detailed below) on the issues of BLC in children and surveillance have been published and reached a wide clinician base. However, LEICSS data has shown the disparity between areas where clinicians are reminded by laboratories to take blood lead samples and those that are not. Developing materials and guidance to support stakeholders (including clinicians) in identifying and managing child lead exposed cases has been identified as a priority.

-

A small number of case reports detailing the management of elevated child blood lead by health protection teams was requested by the SAS laboratories for educational purposes. These are provided in the Appendix section of this report.

-

The case management system used by HPT is being updated and replaced by CIMS (Case and Incident Management System). We are working with the CIMS development team to ensure continuity of data through this transition for surveillance purposes.

Notes

Note 1. Pica is the persistent ingestion of non-nutritive substances at an age where this is developmentally inappropriate.

Note 2. France banned white lead-based interior paint in 1909 (earlier than England); thus exposures from this source would be expected to be lower than in the UK.

Note 3. Both µmol/L and µg/dL units are commonly used internationally to express blood lead concentrations, where 1 µg/dL = 0.0483µmol/L. Divide the concentration in µg/dL by 20.7 to obtain the concentration in µmol/L.

Note 4. HPTs are frontline units responsible for investigating and managing public health threats to their populations.

Note 5. HPZone is the public health case management system used by UKHSA Health Protection Teams when investigating and managing public health threats.

Note 6. Eight cases from 2023 were reported in 2022 and were excluded from the 2023 report.

Note 7. See English indices of deprivation 2019.

References

1. UKHSA. Lead: toxicological overview

2. Public Health England (2021). Evaluation of whether to lower the public health intervention concentration for lead exposure in children

3. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Environmental Health (2005). Lead exposure in children: prevention, detection, and management. Pediatrics: volume 116 number 4, pages 1,036 to 1,046.

4. Etchevers A, and others (2014). Blood lead levels and risk factors in young children in France, 2008 to 2009. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health: volume 217, pages 528 to 537.

5. Rees N and Fuller R (2020). The Toxic Truth: Children’s exposure to lead pollution undermines a generation of future potential. Unicef and Pure Earth

6. Ruckart PZ and others (2021). Update of the Blood Lead Reference Value: United States, 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: volume 70 number 43, pages 1,509 to 1,512.

7. Bazian Ltd (2018). ‘Screening for elevated blood lead levels in asymptomatic children aged 1 to 5 years’. In: External review against programme appraisal criteria for the UK National Screening Committee.

9. Office for National Staistics (2024). Population estimates for England and Wales: mid-2023.

10. Vos T, and others (2016). Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet: volume 396, number 10258, pages 1,204 to 1,222

11. WHO (2010). Childhood lead poisoning: pages 1 to 72.

12. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021). CDC updates blood lead reference value for children

13. Johnson L, Barlow PJ and Barratt RS (1984). Lead in paint: brushed aside? Journal of the Royal Society of Health: volume 104 number 2, pages 64 to 67

14. Crabbe H, and others (2022). As safe as houses; the risk of childhood lead exposure from housing in England and implications for public health. BMC Public Health volume 22 number 1, page 2052.

15. Dave M and others (2023). Lead exposure sources and public health investigations for children with elevated blood lead in England, 2014 to 2022. PLOS One: volume 19, number 7.

16. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1991). Preventing lead poisoning in young children

17. Lewendon G and others (2001). ‘Should children with developmental and behavioural problems be routinely screened for lead?’ Archives of Disease in Childhood volume 85 number 4, pages 286 to 288

18. Public Health England (2018). Surveillance of elevated blood lead in children (SLiC): a British Paediatric Surveillance Unit analysis.

19. Crabbe H and others (2016). ‘Lead poisoning in children: evaluation of a pilot surveillance system in England, 2014 to 2015](https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/doi/10.1289/isee.2016.3829)’. In: International Society of Environmental Epidemiology conference abstracts: volume 2,016, number 1.

20. UKHSA (2024). Lead standard operating procedure for HPTs [internal document].

21. Tsoi MF and others (2021). Continual decrease in blood lead level in Americans: United States National Health Nutrition and Examination Survey 1999-2014. American Journal of Medicine: volume 129 number 11, pages 1,213 to 1,218.

22. Talbot A, Lippiatt C and Tantry A (2018). Lead in a case of encephalopathy. BMJ Case Reports.

23. Loomes R, Hull L and Mandy WPL (2017). What is the male-to-female ratio in autism spectrum disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: volume 56 number 6, pages 466 to 474.

24. Jivraj S and other (2022). ‘How likely are people from minority ethnic groups to live in deprived neighbourhoods?’ Cambridge University Press.

25. Perry MJ, and others (2021). Pervasive structural racism in environmental epidemiology. Environmental Health: volume 20 number 1, page 119.

26. Elliott P, and others (1999). Clinical lead poisoning in England: an analysis of routine sources of data. Occupational and Environmental Medicine: volume 56 number 12, pages 820 to 824.

27. Wasrsi A and others (2024) . Outbreak of lead poisoning from a civilian indoor firing range in the UK. Occupational and Environmental Medicine: volume 81 number 3, pages 159 to 162.

28. Roberts DJ, and others (2022). Lead exposure in children. British Medical Journal: volume 377

29. Ericson B, and others (2020). Elevated Levels of Lead (Pb) Identified in Georgian Spices. Annals of Global Health: volume 86 number 1, page 124.

30. Ruadze E, and others (2021). Reduction in blood lead concentration in children across the Republic of Georgia following interventions to address widespread exceedance of reference value in 2019. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health: volume 18 number 22.

31. Laycock A, and others (2022). The Use of Pb isotope ratios to determine environmental sources of high blood Pb concentrations in children: a feasibility study in Georgia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health: volume 19 number 22

Appendix: Case reports

Case report 1

A 7-year-old female diagnosed with autism, learning difficulties, and pica. A community paediatrician requested lead testing at Guildford Trace Elements, due to the pica behaviour. BLC of 0.27 μmol/L (5.59 μg/dL) (not reported via LEICSS as below the reporting threshold at the time) with no apparent source identified through paediatrician’s questionnaire. BLC rose to 0.39 μmol/L (8.07 μg/dL) after four weeks leading to notification to the health protection team through LEICSS.

A risk assessment was carried out by the HPT and advice was sought from UKHSA Radiation, Chemical and Environmental Hazards (RCE) team.

Outcome of risk assessment

Domestic exposures: The family consists of two adults and two children living in an owner-occupied flat built in 2010. The child lived in the same flat for her whole life. Some peeling paint; father confirmed that the child used to ingest paint but not in recent years. There was no garden, and the parents reported the child does not ingest soil but mouths bottle caps, hair, hair bands, and pencil erasers. Additionally, the child used to chew on the arms and legs of her Barbie-type dolls. She has no toys from outside the UK. The family regularly visit relatives in India for several months at a time and have in the past brought home spices for cooking but denied the child ate them. No occupational exposure identified. Domestic water supply tested negative for lead.

Exposures outside the home: School was built post 1970. The child often puts objects in her mouth, but only for a short time. She also smells things like earth (but doesn’t eat it) and likes touching and spinning around metal playground equipment (not made of lead).

Conclusions and actions: RCE consulted and advised spices from India as a potential source with the elevated lead readings potentially caused by re-mobilisation of lead from previous consumption. Family was advised not to buy spices in India. RCE recommended lead testing before and after travel to India.

Final outcome and closure

BLCs were already declining, and measurements taken prior to and after the next visit to India measured 0.23 μmol/L (4.77 μg/dL) and 0.21 μmol/L (4.35 μg/dL) respectively. It was concluded that exposures were most likely historic, and the case was closed with a recommendation to retest in 6 months and then to test annually while pica behaviour persists. A follow-up BLC, 8 months after the initial report, was 0.18 μmol/L (3.73 μg/dL).

Laboratory case report 2

A 2-year-old male notified by HPT to LEICSS with a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, learning disability and pica behaviour, ingesting hair, and dolls. The Guildford Trace Elements Laboratory reported BLC as 0.35 µmol/L (7.25 µg/dL).

A risk assessment was carried out by the HPT and advice was sought from UKHSA Radiation, Chemical and Environmental Hazards (RCE) team.

Outcome of risk assessment

Domestic exposures: The family lived in a 1920s house with flaking paint although parents denied their child consumed paint or soil however, the family had paint tested revealing high lead content (in some areas exceeding 50%). No occupational exposure to lead. Domestic water contained 6.8 µg/L lead, (above drinking water standard 5 µg/L but below legal limit 10 µg/L) reducing to 2.7 µg/L after flushing.

Exposures outside the home: The child’s nursery, built after 1980, had no paint issues.

Conclusions and actions: Consultation with RCE did not identify any additional sources. The family were advised to stop child’s access to flaking paint. The clinician was advised to liaise with National Poisons Information Service (NPIS) to schedule onward BLC sampling, and to treat the child for any iron and calcium deficiency.

Final outcome and closure

The family arranged privately for remediation to remove lead paint hazard. The water company replaced the communication pipe, and the family arranged to replace an internal lead pipe and switched to bottled drinking water.

Four-weeks following initial mitigation advice, BLC was 0.42 µmol/L (8.70 µg/dL). After the switch to bottled water and restricting child access to paint, BLC reduced to 0.25 µmol/L (5.18 µg/dL) and a third BLC was also near to the action level concentration. The case was closed with advice for a 6 month follow up BLC test, with the understanding that slight variation in BLC would be expected due to the remobilisation of lead into the blood during growth.

Laboratory case report 3

A 3-year-old male notified to HPT through LEICSS. A community paediatrician requested lead testing due to autism and pica (eating dandelions, wood, and dirt). Southampton Trace Elements Laboratory reported BLC 0.72 µmol/L (14.92 µg/dL). A previous (3-4 months) hospital test was 0.81 µmol/L (16.78 μg/dL), had not been reported to the HPT.

Outcome of risk assessment

Domestic exposures: Initial review noted the family consists of two adults and two children living in a 1959s house, privately rented and newly decorated. The child exhibits pica preferring softer chewable items predominantly wood from door frames, bannisters, and furniture, paper, puzzles, toys, soil, sand, leaves, stones, and dandelions. There was no occupational exposure.

Exposures outside the home: None identified.

Conclusions and actions: RCE advised to check the water supply, have house inspected by the Local Authority Environmental Health, do paint sampling if required, and conduct BCL testing of household members.

Follow up review of domestic exposures: Domestic water levels were low however a lead communication pipe was identified and replaced by the water company. An Environmental Health Officer inspection found chipped paint which tested positive for lead. BLC for other family members were below 0.1 µmol/L.

Final outcome and closure

The GP was advised to liaise with the National Poison Information Service (NPIS) on timing for onward sampling and to treat child for any iron and calcium deficiency.

The Local Authority housing officer reviewed the house and arranged for lead paint removal funded through a Disability Facilities Grant. Four weeks after completion BLC showed reduced concentration of lead and the case was closed.

Resources

The UKHSA launched a free online training course, ‘Tackling lead poisoning in public health’, in July 2021, designed for professionals involved in responding to lead incidents to develop their understanding of lead poisoning and public health policy.

A webinar on the importance of lead exposure, held in 2021 by the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) for training of physicans and paediatrics, is available on YouTube (See ‘RCPCH-BPSU webinar series: Toxicity in children – a continuing problem’).

To stay updated with the work of UKHSA’s Environmental Public Health Tracking (EPHT) group and EPHSS, email epht@ukhsa.gov.uk

To find out more about gaining access to LEICSS outputs via EPHSS, email ephss@ukhsa.gov.uk

Further resources for the public health management of cases of lead exposure

The LEPHIS Steering group, with the British Paediatric Surveillance Unit (BPSU) and Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health presented a webinar on lead as part of their series on rare diseases (to raise awareness of LEICSS amongst clinicians).

Lead incident management advice (UKHSA Chemicals Compendium): Lead: health effects, incident management and toxicology

Incidents of Lead Poisoning: an online public health course

Lead pages in the UKHSA chemicals compendium

Lead Exposure in Children Surveillance System: Surveillance Reports from 2021

Lead Exposure in Children Surveillance System: Surveillance Reports published before 2021

Health and Safety Executive report: ‘Exposure to Lead in Great Britain, 2023’

Resources for clinicians

Clinicians with clinical lead exposure queries should consult TOXBASE or contact the National Poisons Information Service.

Procedures for reporting of lead cases to UKHSA

For adult cases with a BLC of ≥0.48μmol/L (equivalent to ≥10μg/dL): contact the local HPT of the case. The relevant HPT can be identified by entering the residential postcode of the case into GOV.UK.

For pregnant women with a BLC of ≥0.24μmol/L (equivalent to ≥5μg/dL): contact the local HPT of the case. The relevant HPT can be identified by entering the residential postcode of the case into GOV.UK.

For children aged under 16 years old at the time of first elevated BLC: please report cases to LEICSS, using lpic@nhs.net

Sources and presentations of lead exposure in children

Important sources of lead exposure in children are as follows:

- deteriorating leaded paint (particularly houses built prior to early 1970s)

- herbal medicinal preparations

- consumer products (if unregulated): medicines, food, spices, ceramic cookware, toys, make-up

- parental hobbies or occupations (including dust on clothing)

- lead water pipes, and lead from drinking water pipe fittings (namely, solder) (particularly houses built prior to early 1970s)

- contaminated soil or land

Children at most risk of lead exposure are as follows:

- children with pica or increased hand to mouth behaviour (for example, children with autism or global developmental delay), particularly with iron deficiency

- children who have recently migrated from countries with less regulation to prevent lead exposure

- children living in older homes and attending older schools containing leaded paint

- children living in more urban or industrial environments

Presentations of lead exposure in children are as follows:

- acute exposure resulting in high BLC: anorexia, abdominal pain, constipation, irritability and reduced concentration, encephalopathy

- chronic exposure

- lower BLCs: mild cognitive and behavioural impairments, may contribute to global developmental delay, decreased academic achievement, IQ, and specific cognitive measures (S); increased incidence of attention-related behaviours and problem behaviours (S), and delayed puberty and decreased kidney function in children ≥12 years of age (L)

- higher BLCs: reduced appetite, abdominal pain, constipation, anaemia, delayed puberty, reduced postnatal growth, decreased IQ, and decreased hearing (S); and increased hypersensitivity or allergy by skin prick test to allergens and increased IgE (L)

Where (S) = sufficient evidence and (L) = limited evidence

Contacts

To notify cases (participating laboratories only), contact: phe.leicss@nhs.net

For general enquiries, contact: epht@ukhsa.gov.uk

For lead surveillance module in UKHSA’s Environmental Public Health Surveillance System, contact: ephss@ukhsa.gov.uk

Steering and working group members (UKHSA unless otherwise indicated)

LEICSS surveillance team: Araceli Busby (surveillance lead and Chair); Hamlatta Rajham; Helen Crabbe; Neelam Iqbal; Rebecca Close; Neena George; Priya Mondal; Emma Benham.

LEPHIS Working Group (as above plus the following members): Sarah Dack; Alec Dobney; Lorraine Stewart; Kerry Foxall; Ovnair Sepai; Richard Dunn; Lee Grayson; Tim Marczylo; John Astbury; Darren Bagheri; Bernd Eggen; Mercy Vergis; Tess Tigere; Naomi Earl; Vince Cassidy.

LEPHIS Steering group (includes the above working group plus the following members): Alan Emond (University of Bristol/British Paediatric Surveillance Unit); Louise Ander (British Geological Survey); Sally Bradberry (National Poisons Information Service, City Hospital, Birmingham); Kishor Raja / Carys Lippiatt (Supra-regional Assay Service Trace Elements laboratories); Andrew Kibble (RCE Wales); Tim Pye (Lead Safe World UK); Geoffrey Mullings (UKHSA CIMS team); Priyanka Chaurasia (Ulster University).

Acknowledgement to laboratories

NHS Supra-regional Assay Services Trace Elements laboratories: Birmingham; Leeds; Southampton; Guildford; London Charing Cross; London Kings College.

Other laboratories notifying cases included in this report: Cardiff Toxicology Laboratories; Southmead Hospital, Bristol; Alder Hey Children’s Hospital, Liverpool; Royal Liverpool University Hospital; Northern General Hospital, Sheffield; Nottingham University NHS Trust Hospital.