Learning during the pandemic: review of research from England

Published 12 July 2021

Applies to England

Authors

Emma Howard, Aneesa Khan and Charlotte Lockyer, from Ofqual’s Strategy, Risk, and Research Directorate.

With thanks to colleagues from

- Department for Education

- Education Endowment Foundation

- Education Policy Institute

- FFT Education Datalab

- GL Assessment

- ImpactEd

- Institute for Fiscal Studies

- Juniper Education

- National Foundation for Educational Research

- No More Marking

- Ofsted

- Renaissance

- Roger Murphy

- RS Assessment from Hodder Education

- SchoolDash

- University College London

- University of Exeter

Executive summary

This review is a report in our ‘Learning During the Pandemic’ series. It comprises a review of the literature exploring what is currently known about changes in students’ learning in England over the duration of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. This supports Ofqual’s effective policy making for assessments in 2021, and years to come.

Here, we focus on three elements relating to how the pandemic has impacted learning. First, we consider teaching and learning experiences across the course of the pandemic, from March 2020 to March 2021. We also explore the scale and nature of any learning losses. Finally, we highlight the differential experiences of learning and how this may be reflected in terms of any learning losses.

This review aimed to be comprehensive of the literature related to learning during the pandemic in England. We provide a summary of the key findings here.

The pandemic has been a challenging period for teachers, schools and colleges, students and parents

While adjusting to the new way of living during the pandemic, many teachers, parents and students took on additional responsibilities that went above and beyond their usual roles and duties, and they should be recognised for their efforts.

The quality and quantity of learning students undertook declined as a result of the pandemic

Spring and summer terms 2020

During the spring and summer 2020 terms teaching and learning was largely remote. Despite their best efforts, many schools and colleges often did not provide as effective teaching as they would have done under normal circumstances. The amount of work provided to students was in many cases much less compared with normal, and pedagogy was often less effective. Studying was most commonly independent of teachers or peers, comprising of worksheets, assignments and watching educational videos. Online lessons, which most closely resembled the usual classroom learning, were less common. With most learning being completed online, having sufficient access to electronic devices, the internet and a quiet study space at home became a critical issue. Most students had access to these resources to some degree, however there were still many who were not able to access their learning in this way.

The autumn term 2020

By the autumn term, schools and colleges reopened so that learning could once again be face-to-face. However, although this term, in general, offered better learning provision than remote learning, they were far removed from a normal year. There were many notable challenges to teaching in the 2020 autumn term. COVID-safe restrictions and social distancing in schools and colleges meant that often, individual students or student ‘bubbles’ had to self-isolate, and continue their learning remotely. This meant that teachers were often faced with the challenge of teaching in class as well as providing online learning for students who were isolating, which generally resulted in a decline in the quality of learning provision, particularly for individual students participating online. Even when students remained in the classroom, COVID-safe practices meant that the usual teaching in some subjects suffered, particularly because teacher-student and peer interactivity, sharing of equipment and practical tasks were reduced or ceased completely. As such, the autumn term was not felt by many to have been a successful period of learning recovery.

The spring term 2021

At the start of the 2021 spring term, England went back into a national lockdown, and learning was predominantly remote again. At this stage, we know less about the students’ learning in the 2021 spring term, but this period of remote learning is thought to have been more successful than previous periods, as teachers were better equipped to deliver remote teaching and access to digital resources for students who did not have them during the first lockdown was also somewhat improved. By March 2021, most students could return to school. While COVID-safe and social distancing restrictions are still in place in schools and colleges, the quality of learning experienced by students is still thought to be far less than it was before the pandemic.

Most students are reported to have some learning losses, while some have severe learning losses and some have learning gains

For most students, their learning has suffered to at least some degree. Teacher estimations indicate that while a small proportion of students made learning gains, most students have learning losses, and sometimes this was severe. The literature indicates that the extended periods of remote learning are likely to account for most of the learning loss.

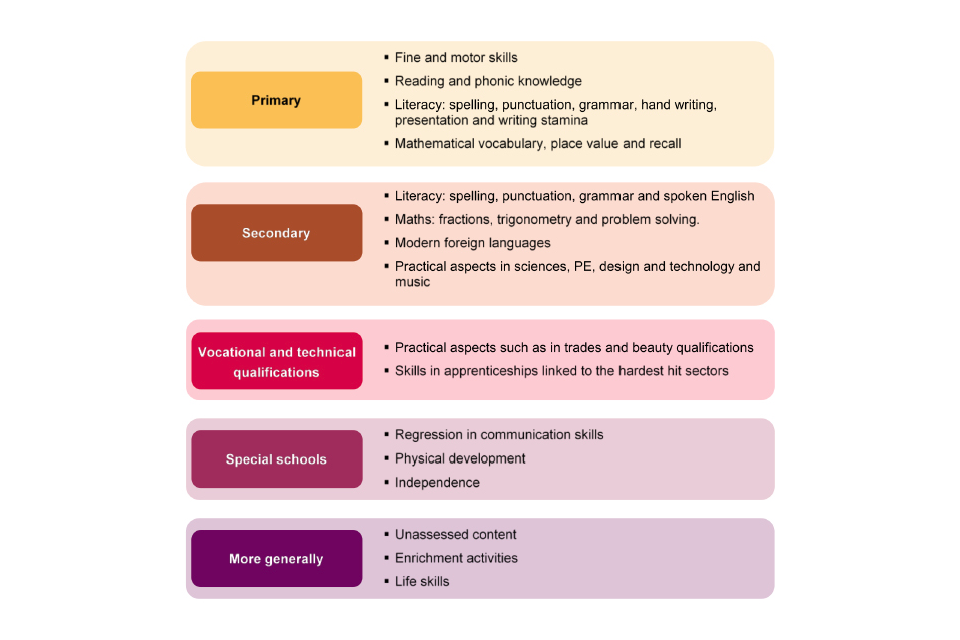

Learning losses appear to be most prevalent in maths and literacy

Ofsted reports from the autumn terms indicate that students were most behind in maths and literacy skills. Practical skills were also identified as being behind, which was most problematic for qualifications with large practical components, such as some apprenticeships, and trades and beauty qualifications.

Experiences of teaching and learning during the pandemic were diverse, but disadvantage and deprivation appear to be most associated with less effective learning and overall learning losses

In this review we note the differential experiences of learning by: age or stage of education, deprivation and disadvantage, attending state or independent schools and colleges, lower attaining students, students with special education needs or disabilities (SEND), gender, ethnicity, region, and students in other circumstances (students living in single-parent households or with multiple siblings, vulnerable children and children of keyworkers).

In general, disadvantage and deprivation appear to be most associated with less effective learning. Teaching and learning for primary-aged students also appear to have been negatively impacted. Teachers’ estimates of how much learning these students have lost reflect these findings, and further raise concerns about the impact of the pandemic on these students’ future learning and occupational opportunities.

Learning experiences were diverse: there were differential experiences both between and within groups

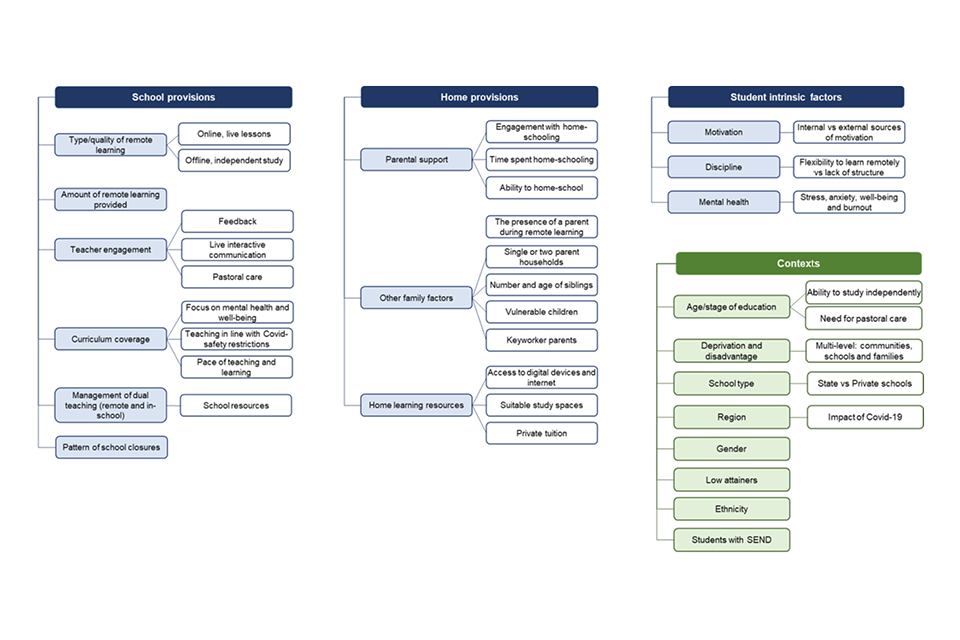

While learning was broadly researched across different groups of students or students from different backgrounds, it is important to keep sight of the fact that the research and data analyses often minimise the role of individual experience. In reality, experiences of teaching and learning during the pandemic were diverse. Here, we briefly note that there are complex interactions between macro- and micro-level influences that give rise to complex and unique variations in experience (and relative impacts) for individuals between and within groups. Examples of factors that contribute to the diversity in experience are presented in the schematic summarising the section on ‘The impact the pandemic has had on learning’ – see Figure 1.

There are important implications for learning recovery

Given the complexity and uniqueness of learning experiences and learning losses, a one-size solution for learning recovery is unlikely to be equally beneficial to all. This has important implications for learning recovery programmes within schools and colleges, and also for wider decision-making and policy implementation in the field of educational assessment.

There is much about learning during the pandemic that remains unknown and under researched

Overall, it is evident that this research field has produced a considerable amount of research in a short period of time to build a foundation of knowledge around the impact of the pandemic on learning in England. However, it remains that there is much that is still unknown. For instance, there is little information regarding the impact of the pandemic for specific subjects, qualifications (particularly for vocational and technical qualifications), and year groups for which the timing of the pandemic has been particularly disruptive to their high-stakes assessments (such as those in years 10 to 13). Further evaluation is required in these under-researched areas to build a more complete picture of learning experiences and any learning losses.

Introduction

This review is a report in our ‘Learning During the Pandemic’ series. In particular, it should be read alongside two specialist reports in this series: ‘Quantifying lost time (report 2)’, and ‘Quantifying lost learning (report 3)’. This series of reports aimed to, as fully as possible, understand the impact of the pandemic on learning in the run up to high-stakes assessments. This review in particular focuses on the literature around students’ learning, and learning losses in England over the course of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Our work monitoring and evaluating the emerging research around learning during the pandemic supports Ofqual’s effective policy-making in the run up to assessments in 2021 and beyond.

The current review

In preparing this report, we reviewed over 200 sources that discuss teaching, learning and students’ experiences over the course of the pandemic: from school closures in March 2020 until March 2021. Although this report was not based on a ‘systematic review’ of the literature, it intends to be comprehensive, in that we reviewed all available literature that was relevant to the impact of the pandemic on learning. We provide an evaluation of the literature sources in the section titled ‘Discussion’.

This review focuses on teaching and learning of students undertaking the assessments and qualifications that Ofqual regulates. As such, the focus is primarily on teaching and learning in England, from primary-aged children to school or college leavers, typically aged 19. It should be noted, however, that there is more literature within some contexts than others. For instance, the literature is more heavily focused on primary and secondary students’ experiences. Specific subjects or qualifications tended not to be the focus of research, however, where this is apparent in the findings, we include these in the review. School closures on 20 March 2020 meant that much teaching and learning had to be undertaken remotely. There is widespread concern regarding the degree to which students’ learning has suffered since the start of the pandemic, and the amount of learning they have lost. Here we explore several issues related to learning loss, which we discuss across three main sections:

- the impact the pandemic has had on learning: within this section we look at the literature around school and college, and home provision for learning, as well as student engagement

- the scale and nature of learning loss: within this section we explore accounts about how much learning has been lost, what aspects of learning have suffered the most, and what the recovery of learning loss looks like thus far

- the differential experiences of learning loss: within this section we address how the experiences of learning were diverse, both between and within groups. We provide an overarching summary of the scale of learning loss, and possible contributors to this, across different contexts, such as age, disadvantage and ethnicity, to name a few

The impact the pandemic has had on learning

The start of the pandemic in March 2020 changed how teaching and learning were undertaken for most learners. Schools and colleges went through periods of being closed to most students and learning were often undertaken remotely – although vulnerable children and children of keyworkers could still attend school during these periods. When schools and colleges re-opened for in-school teaching, the learning environment was far removed from what it was before the pandemic. Consistent with changes to social-distancing measures, school and college closures, and the degree to which students were able to return to school or college, the nature of teaching and learning and the relative impacts between March 2020 and March 2021 were diverse. It is important to note that much of the literature exploring the impacts of the pandemic on learning focuses on the immediate impact, typically between March and July 2020. Currently, at the time of writing, there is limited insight as to the nature and impacts of teaching and learning beyond autumn 2020.

We present the findings of the literature chronologically, firstly addressing findings related to the initial school closures in March 2020 through to the end of the 2020 summer term in July, and secondly addressing teaching and learning during the 2020 autumn and 2021 spring terms.

Remote teaching and learning in the 2020 spring and summer terms

The literature outlines several key aspects of teaching and learning that acted as barriers to learning or were protective against the negative impact of the pandemic. Here we categorise them into factors related to:

- school and college provision

- home learning provision

- student intrinsic factors

These dimensions will be explored in turn. Where this is discussed in the literature, the differential impacts on different groups of students, or across different contexts, are introduced. Also see the discussion section for an overview of the differential experiences of learning loss during the pandemic.

School and college provision

School and college closures from 20 March 2020 until the end of the summer term meant that most[footnote 1] teaching and learning had to be undertaken remotely. There is a large amount of research focused on the initial phase of the pandemic, between March and July 2020. Here we separate the findings and present them under five key areas:

- The type and amount of remote learning provision.

- The quality of the remote learning provision.

- Teacher engagement.

- In-school provision for children of keyworkers and vulnerable students during the first lockdown.

- The return to school for some students in June 2020.

The type and amount of remote learning provision

Overall, students were spending much less time on learning during the 2020 spring and summer terms than they would have done pre-pandemic. This issue is explored comprehensively in Report 2 from our ‘Learning During the Pandemic’ series, but to summarise, before the pandemic, students would spend around five to six hours learning per day in school, as well as taking additional time for homework. This contrasts with accounts from parents, teachers and students about the time spent on remote learning during the spring and summer terms, which estimate that students were spending, on average, around 2.5 to 4.5 hours on learning per day (Andrew, Cattan, Costa-Dias, Farquharson, Kraftman, Krutikova… & Sevilla, 2020a; Cattan, Farquharson, Krutikova, Phimister, Salisbury, and Sevilla, 2020; Green, 2020; Pensiero, Kelly & Bokhove, 2020; Williams, Mayhew, Lagou, & Welsby, 2020). This section looks into the learning activities students were undertaking during this time.

The types of learning that took place while schools and colleges were closed can be categorised into ‘online’ and ‘offline’ learning. Online learning refers to the use of real-time internet-facilitated resources, whereby students engaged in a live ‘online class’. Online learning was typically delivered via online-conferencing software, and could involve text chats and verbal interactivity with teachers and peers. Offline learning refers to learning that is undertaken outside of an ‘online class’ and independent of a teacher. This typically involved completing worksheets, undertaking project work or assignments or watching educational videos.

Offline learning was much more prevalent than online learning throughout the period of remote learning, with around 90% of parents of both primary and secondary children reporting that their child received offline learning resources. Provision tended to be more limited for online learning in schools, although colleges appear to have made more use of online learning platforms (Association of Colleges, 2020). Parents indicated that schools were more likely to provide online learning to secondary students than primary students (59% compared with 44%, respectively; Cattan et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2020). The Association of Colleges reports that online learning was adopted for the majority of subjects in 70% of colleges surveyed, but were condensed with 35% receiving a significantly reduced timetable (Association of Colleges, 2020).

For those who did receive online lessons across the school week, this accounted for a small proportion of students’ remote learning time. Parent reports of their child’s time use between April and June 2020 indicates that primary and secondary students spent, on average, between 1 and 2 hours on online learning per day, with secondary students receiving slightly more online learning than primary students (2.14 hours, compared with 1.48 hours, respectively; Lucas, Nelson and Sims, 2020; also see: Andrew et al., 2020a; Bayrakdar & Guveli, 2020; Pensiero et al., 2020).

However, using averages to understand students’ remote learning provision can mask the experiences of many students. Looking further at the data, it is clear that some schools and colleges delivered far less provision for online learning than others. In April, shortly after schools and colleges closed and teaching and learning was remote, online provision was found to be delivered every day to around a third of students (Pensiero et al., 2020; Benzeval, Borkowska, Burton, Crossley, Fumagalli, Jäckle, … & Read, 2020a). At the same time, 60% of parents of primary students reported that their child did not have any online lessons. For secondary students this was just over 50%, and for post-secondary students this was 39% (Eivers, Worth & Ghosh, 2020; Pallan, Adab, Clarke, Duff, Frew … & Murphy, 2021).

In May 2020, online provision had increased, where the number of students not undertaking online classes had reduced to 30% of primary, and 28% of secondary students (Andrew et al., 2020a). In contrast to this, around 20% of secondary students reportedly spent more than 4 hours a day participating in online learning in May 2020. For primary students this was around 8% (Andrews et al., 2020a). Moreover, online learning provision was not available to all students every day, with only 7% of students receiving at least one online teaching lesson every day.

At the start of the lockdown in March 2020, while almost all students in years 10 and 12 were provided with school work, almost half of parents whose children who were in years 11 (42%) and 13 (49%) reported that their school did not provide them with any remote learning (Eivers et al., 2020). The cancellation of exams probably had a major role in this decision. By the time of the school closures, students had typically covered all of the course content, and would usually be in a period of revision in preparation for their exams. Without the exams to revise for, many schools and colleges likely prioritised learning for other year groups over the year 11 and 13s. It is not clear from the literature whether learning provision from the school or college picked up for year 11 and 13 students as remote learning continued through the summer term. This is unlikely to have happened, however, as these students would typically be on ‘revision leave’ from May onwards, to continue their learning independently.

Students spent more time undertaking offline work than online work during the first lockdown. On average, parents reported that primary and secondary students spent between 1 and 2 hours on offline learning per day. However, there was also large variation in time spent on offline work (Andrew et al., 2020a). Around 15% of primary students, and 25% of secondary students, reportedly did not undertake any offline learning (Green, 2020). Around 60% of primary, and 30% of secondary, students reportedly spent up to 2 hours on offline learning. At the other end of the range of experience, 25% of secondary students spent between 2 and 4 hours on offline learning and 17% spent more than 4 hours a day on offline learning.

The rapidity with which remote learning resources were implemented in light of the pandemic is striking. Schools and colleges, and individual teachers, constructed their own methods of remote teaching. This meant that there was diversity in the approaches teachers took and the resources that were available to facilitate this. Parental reports indicate differences in the provision of remote learning across different contexts (Andrews et al., 2020a; Andrews, Cattan, Costa-Dias, Farquharson, Kraftman, Krutikova, … & Sevilla, 2020b). The most deprived students and students in state schools and colleges were less likely to experience online learning and have interactions with teachers, students and peers than less deprived students and students in independent schools. Independent schools were also nearly twice as likely to provide full school days than state schools (Eyles & Elliot-Major, 2021; Cullinane & Montacute, 2020). In place of online learning, paper-based resources were more common in schools with the most deprived students. This was largely driven by differences in digital resources and devices, but has further implications for the quality of students’ learning, as will be discussed in the section, ‘Quality of the remote learning provision’.

There were also regional divides, whereby 12.5% of students in London received daily online teaching, compared with 5% of students in the East Midlands. Also, while the average proportion of students who received four or more pieces of offline work per day was 20%, in the south-east this was 28% and in the north-east this was only 9%.

While there is less research exploring the impact of the pandemic for learners outside of schools and colleges, there is some that highlights that there are also contexts for which learning provision has been more limited or removed entirely. This is particularly the case for college students on practical courses and apprentices, who have been severely impacted by the pandemic (Association of Colleges, 2020; Ofsted, 2020a). During April 2020, a survey of employers (Doherty & Cullinane, 2020) reported that 36% of apprentices were furloughed, 8% were made redundant, and 17% had their off-the-job learning suspended. Apprentices experienced further challenges during the first lockdown, with 37% of surveyed employers reporting that a lack of equipment at home, or unsuitability of the work, meant that some apprentices could not work from home. A further 14% of employers reported that some apprentices did not have access to a digital device or the internet to continue their apprenticeship from home.

Quality of the remote learning provision

There was no prior requirement for schools and colleges across England to engage in remote teaching and learning before the pandemic. As such, investment in remote education solutions was lacking at the time of the initial school closures in March 2020. The lack of infrastructure to support online teaching resulted in many teachers feeling initially unprepared to deliver teaching remotely (Educate, 2020; Ofsted, 2020a).

Interviews with teachers carried out by Educate explored the change to teaching and learning across the period of initial school closures in the 2020 spring and summer terms. In total, 46 interviews were carried out between July and September 2020, where teachers were asked to reflect back on their teaching practices since the initial lockdown in March 2020. Overall, it was evident that to cope with the severe changes to the way teaching was delivered, most schools and colleges adopted Remote Emergency Teaching practices. Senior leaders report that this largely comprised of using materials provided by external providers (92%) and using externally provided pre-recorded video lessons (90%). Where schools and colleges did provide their own resources, they were typically worksheets (80%; Lucas et al., 2020). As previously discussed, fewer senior leaders reported that their teachers delivered active teaching provision such as live remote lessons (14%) or online discussions (37%, Lucas et al., 2020).

Teachers also reported that the move to remote teaching was not undertaken with ease. Out of 46 interviews Educate (2020) undertook, only 3 schools (1 state school and 2 independent schools) reported that the transition to remote teaching was seamless. Most of the teachers who took part in the interviews further indicated dissatisfaction with the teaching that they had delivered in the spring term, reporting that their approaches to remote teaching needed to be reviewed. This was particularly driven by views around the lack of efficiency, interactivity and engagement between students and teachers.

Any type of learning provision is important to support students’ learning during school closures, but it is important to consider that some methods of teaching may be more effective than others. Moreover, the quality of the teaching within those methods also has implications for effective learning. As we have seen, offline resources were the most common learning provision during the first lockdown in March 2020 (Andrew et al., 2020a; Green, 2020). Offline resources can be beneficial as they enable students to make better use of their time spent on their education, where students can move through the work at their own pace (Müller & Goldenberg, 2021). However, offline resources are unlikely to sufficiently substitute for the high-quality professional teaching delivered by teachers because they are likely to lack crucial elements of effective pedagogy. Effective pedagogy includes clear explanations about learning content, scaffolding to support learning and adapt to learning needs, and appropriate feedback that promotes development (Andrew et al. 2020b, Education Endowment Foundation, 2020a; Müller & Goldenberg, 2021). Effective pedagogy is particularly important for supporting younger students’ learning, who are less likely to be able to effectively undertake independent learning in the way the older students can (Müller & Goldenberg, 2021).

Online lessons are the closest substitute to in-class learning that students will have experienced pre-pandemic. They are argued to be the most effective remote learning activity due to the presence of the teacher, which facilitates the aspects of effective pedagogy outlined above (Andrew et al. 2020b). The Education Endowment Foundation (2020a) further reported that pre-recorded material could be used by teachers, as what matters most is explanations building on pupils’ prior learning and how their understanding is later assessed. It is not clear from the research how much online teaching was delivered with good pedagogy during the 2020 spring and summer terms. However, given that students generally reported that they would have liked more feedback and engagement with teachers and peers (Child Poverty Action Group, 2020), it is likely that the online teaching was below the quality that students receive during normal periods of learning, pre-pandemic.

It is worth noting, that while the time students spent on learning did not change over the period of the initial lockdown (see Report 2 in our ‘Learning During the Pandemic’ series), the quality of remote learning resources improved. As the school closures were extended into the summer term, schools and colleges reduced their reliance on offline resources, and started to incorporate more pre-recorded and live online lessons into their teaching (Cattan et al., 2020; Edurio, 2020). This is shown in the increase of the proportion of parents reporting that their students were provided with online learning between April and June 2020, which rose from 44% to 51% for primary students, and 59% to 65% for secondary students.

In general, after the initial switch to remote learning, teachers reported feeling able to deliver remote learning well (Lucas et al., 2020), indicating they were happy with the way in which their school or college reacted and adapted to the new way of teaching. Those who felt this way were largely driven by feeling well-supported by their senior leaders. School leaders tended to adopt a flexible approach to deliver remote teaching, and considered relevant research and consultations with staff, students and parents. Some schools and colleges trained staff on how to refine their lesson delivery and teach effectively remotely (Ofsted, 2020b). With teaching mainly taking online forms, confidence in using digital resources also played a large part in teachers feeling able to deliver remote learning (Lucas et al., 2020). However, confidence in digital skills was not universally felt. There were further barriers when it came to less experienced teachers moving to a remote curriculum at speed, such as ensuring staff having digital skills to teach content remotely (Ofsted, 2020a). Teachers were often using online resources for delivering remote lessons, assessing students, providing feedback and organising collaboration spaces for students to work together (Edurio, 2020). Findings across two surveys (undertaken in May, and June to July) exploring teachers’ views about technological barriers to effective teaching indicate that, while 30% of teachers reported that they did not need any further training to support their teaching, a quarter said they would need training to use new online teaching tools effectively (Edurio, 2020; Menzies, 2020). The areas of training teachers reported would be most valuable to their new way of remote teaching was for using technology in general (18%), organising digital collaboration spaces for students (17%), and delivering online lessons (15%, Edurio, 2020).

The change to remote teaching had further impacts on the content that was delivered to students. Teachers adapted their teaching in a way that met the needs of their students, but sometimes this meant diverting away from covering the curriculum. Research shows that 80% of primary and secondary teachers (out of ~1,800 surveyed) reported that, up to May 2020, all or certain areas of the curriculum were receiving less attention than in a typical learning year (Lucas et al., 2020). Schools and colleges serving the most deprived communities were reported as struggling the most to cover the curriculum during lockdown (Lucas et al., 2020), and curriculum alignment was particularly difficult to achieve in primary schools. Around 83% of primary teachers reported struggling to cover the curriculum sufficiently, where 61% of secondary teachers reported that this was the case (Lucas et al., 2020).

There were two main contributors to reduced curriculum coverage: challenges related to student engagement, and challenges related to access to teaching provision. Primary teachers report prioritising learning activities that were engaging and motivating for students (Lucas, et al., 2020; Moss, Bradbury, Duncan, Harmey, and Levy, 2020a). The importance of parental engagement and support for primary students’ learning was also well understood by primary teachers, and teachers often adapted learning resources so they could be fun and accessible for the whole family (Moss et al. 2020a; Moss, Bradbury, Duncan, Harmey and Levy, 2020b). In addition, in primary schools, the focus in the spring and summer 2020 terms was on maintaining prior learning over learning new material (Lucas et al., 2020). Primary school leaders mentioned that the lack of activity-based teaching and learning often resulted in younger students not being able to develop the conceptual understanding for new materials that would be achieved in the classroom. Therefore, where new curriculum content was covered in their remote learning, younger children were struggling to embed it.

Teachers further adapted their teaching to ensure that primary students had the facilities to engage in learning activities. For many serving deprived communities, this meant prioritising ensuring that students without access to devices had learning opportunities even if they could not access online resources (63%; Moss et al., 2020a, Moss et al., 2020b). A quarter of primary teachers (responding to the survey) reported that they hand delivered hard copies of learning resources to students’ homes (Moss et al., 2020a).

Even though two-thirds of secondary teachers reported that all or certain areas of the curriculum were receiving less attention than in a normal year (Lucas, et al., 2020), curriculum coverage in secondary schools was less of a concern than in primary schools. Although there is less research that addresses this directly, secondary students are less likely to share the challenges to learning that younger students have. Older children tend to be better able to undertake independent learning than younger children and are more likely to have access to (and be able to use unsupervised) digital devices with which to undertake remote learning. Although there were fewer barriers in teaching, learning and covering the curriculum for secondary students, compared with primary students, secondary students’ learning of the curriculum was disrupted nonetheless, and many experienced, and continue to experience, learning loss.

We cover the scale and nature of learning loss experienced by students further in the section, ‘The scale and nature of learning loss’, but it is clear that student engagement with their learning and motivation also influence this (see the section, ‘Student intrinsic factors’). Teaching of some parts of the curriculum was also understandably hindered by lockdown restrictions. For instance, some secondary leaders reported that because students were unable to access equipment, learning in more practical subjects was disrupted, for instance in PE, music, science, and design and technology (Ofsted 2020b; Ofsted 2020c).

Teacher engagement

Teacher engagement is a fundamental aspect of effective teaching and learning. The circumstances of the lockdown in the 2020 spring and summer terms meant schools and colleges were using, or sometimes inventing, new remote ways in which to teach, engage, motivate and monitor the well-being of their students. With schools and colleges being closed, there was a shift away from teachers being in close daily contact with their students, where students could ask questions, work with peers and informally chat with teachers. Overall, teachers and students report that teachers not being able to wander around the classroom and directly engage with students was a barrier to effective educational communication (Ofsted, 2021). To overcome the reduced nature in which teachers and students could engage with each other, many schools and colleges delivered alternative means to keep in touch with students and continue effective communication about their learning. For instance, teachers report using chatroom discussions, 1-to-1 calls with parents and students, interactive questioning during live lessons, adaptive learning software, and digital exercise books with commenting, editing and feedback functionality (Ofsted, 2021). However, clarity, feedback and peer and teacher discussions were often reduced compared to when students were in school, or in some cases, were completely absent.

In May 2020, teachers reported that they were in regular contact with, on average, 60% of their pupils (Lucas et al., 2020). This comprised of teachers delivering online live lessons, setting work, checking in with students and providing feedback. In general, the majority of students (78%) reported they were happy with the way their school supported them in the period immediately following school closures (Yeeles, Baars, Mulcahy, Shield & Mountford-Zimdars, 2020). However, in a separate survey, students reported that they wished they had received more feedback from teachers on their work (Child Poverty Action Group, 2020).

Teacher feedback can be an important teaching tool that helps students adjust their skills and learning strategies. Students reported that during the initial school closures, teacher feedback helped them feel more motivated to continue with learning activities (Child Poverty Action Group, 2020). In May 2020, 60% of parents of primary school children and 40% of parents of secondary school children reported that their child did not receive personalised feedback from their teacher(s) during the lockdown (Educate, 2020). This may at least in part be due to secondary students having several teachers across their subjects, and therefore having more opportunities for contact and feedback. Of those students receiving homework and submitting it back to school, 65% report that at least half of the homework was checked by teachers. This proportion is higher among post-16 students, though (82%, Benzeval et al., 2020a). A few school leaders acknowledged the importance of immediacy of feedback to students about their work (Ofsted, 2021), however students separately reported that in general, they were often frustrated about the length of time they had to wait to receive comments from teachers on work they had submitted (Child Poverty Action Group, 2020). When considering the workload implications of rapid feedback, this is likely difficult to deliver. Nevertheless, research shows that in general, feedback for a large proportion of students’ schoolwork was not delivered at all (Child Poverty Action Group, 2020; Educate, 2020; Green, 2020).

Because of the resource requirements and workload implications of maintaining the teaching and learning dialogue between teachers and students, there are variations in the degree to which teacher engagement was experienced by different groups of students. Again, much of the variation seen around this is associated with measures of deprivation, with the most deprived students experiencing less teacher feedback and engagement.

Teachers in the most deprived schools report being in contact with around half of their students at the beginning of school closures, which is a significantly smaller proportion than teachers in the least deprived schools (67%) (Lucas et al., 2020). Moreover, children with limited or no access to electronic devices were less likely to be able to submit their work to have it checked by their teacher and receive feedback (Andrew et al., 2020b; Green, 2020). Students attending a state school (53%) and students eligible for free school meals (40%) were less likely to have work checked by a teacher, compared with students attending independent schools (76%), or those not eligible for free school meals (56%, Green, 2020). With regards to giving feedback, special education providers reported that they personalised learning resources for the majority of their pupils (66%) and gave personalised feedback to 73% of their pupils (Skipp, Hopwood & Webster, 2020).

The amount of feedback and contact time with students differed depending on the phase of education, with more primary school teachers (62%) reporting they were in contact with their students than secondary school teachers (50%). However, the type of contact with pupils was also different across these phases of education. Primary school teachers focused more on checking in with students and parents rather than teaching and learning than secondary school teachers. Secondary school teachers also typically teach more students than primary teachers do, across different classes and year groups. This inevitably reduces the amount of time that can be dedicated to any one student (Lucas et al., 2020).

In general, where learning was remote during the 2020 spring and summer terms, individual students experienced a reduction in teacher engagement compared with when they were at school, pre-pandemic. However, it is important to reflect that teachers were faced with new and never-seen-before challenges, and were navigating the new means of teaching as best as they could. Setting-up and adjusting to new ways of working, ensuring students had sufficient resources to learn and adapting teaching to ensure that students without sufficient resources were still able to undertake learning activities, went beyond teachers’ normal duties. Adapting to the new means of teaching resulted in increases in teachers’ workload, with teachers being pushed to the limit of what they could deliver (Ofsted, 2020b; Ofsted, 2020c).

In-school provision for children of keyworkers and vulnerable students during the first lockdown

Although schools and colleges were closed to most students during the lockdown, they remained open for the children of keyworkers, and vulnerable children, including: children of social workers, health professionals and teachers; looked-after children; and those with an education, health and care (EHC) plan. Individual schools and colleges were free to decide the nature of provision they offered to children of critical workers and vulnerable pupils during lockdown. Survey data suggests that while most schools were teaching the curriculum to the students in school, there was still a meaningful variation in educational experiences between schools. A survey carried out with almost 19,000 teachers in April 2020 asked teachers how many hours per day learners were being taught in school. While half stated they were offering 3 or more hours of teaching per day, almost one quarter answered ‘none – we’re offering childcare’ (Stewart, 2020, pg.1).

Similar variation was apparent the following month, where almost three-quarters of senior leaders indicated that the focus of in-school provision was providing a place where students were safe and cared for, rather than providing curriculum-based teaching. Nonetheless, most schools still taught the curriculum, particularly at secondary level, and the authors concluded that students undertaking in-school learning experienced the same, if not better, learning provision than those being taught remotely. This was because there were more opportunities for teacher support and supervision (Julius and Sims, 2020). Just under half of primary and secondary school leaders reported they were teaching students based in school the same curriculum content that was being sent to children who were learning remotely. A further 41% of secondary leaders reported that children were being provided time or resources to work on curriculum content with limited teaching input. This was 14% in primary schools. At primary level the picture is more mixed. While most leaders report covering aspects of the curriculum as their main approach, just under a third reported that the main approach of in-school provision was extra-curricular activities, such as arts and crafts. This suggests that a significant minority of vulnerable pupils and the children of keyworkers in primary schools may have covered less curriculum content than their peers who were based at home.

As with much of the literature on online provision, there is evidence that the nature of in-school provision may vary considerably depending on the deprivation of the school community. While 58% of senior leaders in schools serving the most affluent communities report their main approach is teaching the same curriculum content as is sent to other students, this falls to 35% of senior leaders in the most deprived communities. Similarly, leaders in the most deprived schools were twice as likely to report that their main approach was to provide extra-curricular activities than those in the least deprived schools. There were also significant differences across regions with leaders in the north-west twice as likely to report providing extra-curricular activities for pupils in-school compared to those in the south-west, the south-east and London (Julius and Sims, 2020).

Regarding provision in special schools, anecdotally, those children who had remained in education throughout were reported to have benefited from the experience and often flourished with smaller class sizes and more support. Some others enjoyed being at home and also made good progress (Skipp et al., 2020).

The return to school for some students in June 2020

In June and July of 2020, schools began to reopen for key year groups. Report 2 from our ‘Learning During the Pandemic’ series covers this in depth, but to summarise, from 1 June, primary schools were allowed to open for nursery children, as well as for reception, year 1 and year 6 students. From 15 June, secondary schools, sixth forms and further education colleges were allowed to open for years 10 and 12, to support students working towards their GCSEs and A levels the following year. However, guidance largely suggested that schools and colleges primarily educated these year groups remotely, and to keep in-school lessons to a minimum. Attendance in school was also not compulsory for students, and while 89% of primary and 74% of secondary schools did reopen, uptake of this provision was limited, with attendance at 27% for primary, and 5% for secondary school in July. As such, remote learning continued to be the predominant means of learning and 95% of secondary and 82% of primary teachers reported that they continued to provide remote learning (Sharp, Nelson, Lucas, Julius, McCrone & Sims, 2020).

For those students who did return to school, social distancing and other ‘COVID-safe’ practices appear to have negatively impacted the quality of in-school provision (Lucas et al., 2020). Despite being happy with the way in which their school adapted to remote learning early in the March lockdown, by July 2020, after a long period of teaching and learning under COVID-19 restrictions, the majority of teachers felt they were not able to teach to their usual standard (74%). The challenge of teaching under conditions of social distancing was the main reason for this (Sharp et al., 2020). Social distancing prevented teachers from moving around the classroom to support and interact with pupils. Practical and group work was also made more difficult to coordinate safely, and students were prevented from sharing equipment. In the same study, half of senior leaders reported using teaching assistants to lead classes to help manage the supervision of smaller ‘bubbles’, and almost half of teachers said they were mainly teaching pupils they did not usually teach (Sharp et al., 2020).

When returning year groups went back to school last summer, some schools focused on well-being and in-class teaching only for the 3 core subjects: maths, English and science (International Literacy Centre, 2020a, 2020b; Sharp et al., 2020). For instance, Teacher Tapp (2020a) found that 1 in 3 secondary schools delivered face-to-face teaching in just the 3 core subjects daily. This is not to say, however, that these schools did not continue remote learning for the wider diet of subjects. Independent and better-resourced primary schools were more likely to be teaching the breadth of the curriculum as normal, whereas state schools were most likely to deliver an adapted curriculum (Teacher Tapp, 2020a).

Although the quality of remote learning provision improved as remote learning continued, compared with that in the initial weeks of lockdown (Cattan et al., 2020; Edurio, 2020), evidence suggests that the quality of online provision for students continuing to learn remotely may have dipped as schools re-opened for some year groups. Teachers’ focus was increasingly split between those learning at home and those learning in school, leaving students based at home with less support and teacher engagement than they had been used to (Sharp et al., 2020; Teacher Tapp; June 2020). During this time, teachers report most commonly asking students to access content from external sources, complete a worksheet or read a book (Sharp et al., 2020), and therefore in general included fewer active and interactive learning opportunities.

Home learning provision

While schools and colleges were closed, the home environment had a more crucial role in facilitating students’ learning than before. This section looks at the impact of several important home provisions and their role in supporting students’ learning. In particular, we address parental support, other family factors, home learning resources and home learning environments. Although the literature supporting this section largely refers to findings from the initial period of school closures during the 2020 spring and summer terms, it is likely that many of these findings can be generalised to account for experiences beyond that period. For instance, during further school closures in the 2021 spring term and when individual students or student bubbles had to self-isolate and continue learning from home. This is helpful as, as we discuss in the section, ‘Teaching and learning in the 2020 autumn and 2021 spring terms ‘, there is little research that tells us about home learning provision in the autumn 2020 and spring 2021 terms.

Parental support

With the closure of schools and colleges, parents took on more responsibility to support their children’s learning at home. Just over half of teachers report that parents were engaged with their children’s home learning (Lucas et al., 2020; Villasden, Conti & Fitzsimons, 2020). In total, 58% of parents reported that they were home-schooling their children during the initial lockdown. Parents typically took part in more home-schooling for primary compared with secondary-aged children (Andrew et al., 2020a; Lucas et al., 2020; Pensiero et al., 2020; Villasden et al., 2020). They spent just under 1 hour supporting secondary children with their learning per day, compared with 2 hours supporting primary-aged children (Pensiero et al., 2020). Teachers further reported that 48% of parents of secondary-aged children were engaged with their child’s learning, compared to 56% of parents with primary-aged children.

These differences in parental engagement and support likely reflect the type of assistance that is required by children across these ages, with the need to supervise children in their learning becoming less as they grow older. The learning content of secondary-aged children also becomes more difficult, and those in key stage 4 were most likely to report that they were unable to get sufficient support with their work from their parents: a quarter of students at this education level reported that their parents could not help them (Impact Ed 2020).

Around half of parents reported that they found it either ‘quite’ or ‘very’ difficult to help their children with their learning (Andrew et al., 2020a, 2020c), and only half felt confident in their abilities to home-school (Williams et al., 2020). Home-schooling was clearly a challenging task for both parents and students. Responses to a parent survey indicate that 63% of households said either the parent, the child, or both, had ended up in tears over remote learning (Education Endowment Foundation, 2020b). Parents reported that balancing homeworking with home-schooling was challenging and that limited time for parental support was a driving factor for why parents reported their children were struggling. This was particularly the case for parents of younger children (Child Poverty Action Group, 2020; Williams et al., 2020). Parents also felt they needed better support from schools and colleges to undertake the home-schooling task, reporting that they needed clearer instructions on how to use the resources provided to them as well as specific support around how to teach certain topics (Child Poverty Action Group, 2020).

Over the course of the 2020 spring and summer terms, engagement of parents of both primary and secondary-aged children reduced, from 55% in May to 44% in July. By July, in many occupations, employees were allowed to return to work. This is likely to have further reduced parents’ capacity to support their children’s learning at home. This effect is more greatly observed for parents of primary children, which again, is likely a reflection of how the supervision required to maintain home-schooling for younger children was critical, yet unsustainable for many parents (Lucas et al., 2020).

Different contexts gave rise to parents’ differential experiences of home-schooling. Parents with graduate degrees reported feeling more confident to home-school their children compared with non-graduate parents (70% and 60%, respectively). Graduate parents were also likely to help their children more frequently, with 80% of graduate parents home-schooling their children 4 days a week, compared to 60% of non-graduate parents (Anders, Macmillan, Sturgis & Wyness, 2020). However, further research reports that parental education was unrelated to the overall amount of time spent helping with their child’s schoolwork (Eivers et al., 2020).

Parents in the top fifth of earnings were also more likely to report feeling confident in their ability to make up for lost learning as a result of school closures, than parents in the bottom fifth of earnings (86% and 29%, respectively, Eyles & Elliot-Major, 2021). In general, more deprived families found it difficult to support their children as they felt they had more limited resources to do so (Andrew et al., 2020a; Child Poverty Action Group, 2020). Parents in middle income households in particular were in a uniquely difficult position to support their children’s learning. This is because resources were more limited. They were more likely to continue working at home through lockdown than the poorest households, while having fewer resources to support home learning than the wealthiest households (Andrew et al., 2020a; Green, 2020; Eivers et al. 2020).

Children receiving free school meals were more likely to receive help from their parents. This is largely driven by their parents being less likely to be working during the lockdown (Green, 2020). However, parents of children who were eligible for free school meals faced further challenges in that they were the least likely to feel confident about home-schooling, and least likely to understand their child’s learning tasks (Education Endowment Foundation, 2020b). There were also regional differences in parental support provided to home-schooling during the 2020 spring and summer terms that may be related to regional deprivation. Teachers in schools serving the most deprived communities reported less parental engagement than the least deprived schools (Lucas et al., 2020). The northern regions of England (Yorkshire and the Humber: 50%) saw slightly lower levels of parental engagement than the south and east of England (excluding London: 59%).

Parents report that home-schooling was particularly difficult for children with SEND. In June and July 2020, Parentkind asked parents of children with SEND about their home-schooling experiences. Overall, these parents were struggling with home-schooling, with 34% of parents reporting they were not coping well with the arrangements for learning since school closures began. Almost half further reported that they were unsatisfied with the home learning support that was provided by the school (Parentkind, 2020a).

Other family factors

A number of other family factors also impacted home-learning for many students. In particular, the literature explores the impact of parental working patterns, single-parent households, and the presence of siblings on remote learning.

The presence of a parent in the home was associated with a greater volume of remote learning. For instance, students participated in more remote learning when both parents worked from home during lockdown, compared with parents with other working patterns (Pensiero et al., 2020). Students with unemployed parents were also more likely to engage with more offline learning than students with working parents. The latter findings are likely to be a result of unemployed parents having more time to support their children, however, we should consider that these parents may also have been more aware of the activities their students were partaking in, and remote learning was likely more visible to them.

Employment status and working patterns during the lockdown are also closely linked to socioeconomic status, where the parents in the wealthiest families were more likely to continue working from home, compared with mid- and low-income families, where parents were more likely to continue working in their place of employment or be furloughed (ONS, 2021). It is therefore difficult to determine which factors were the most influential on students’ remote learning, as parents who worked from home during lockdown were also more able to support their child’s learning effectively, and provide home resources that facilitated this (Andrew et al., 2020a; Child Poverty Action Group, 2020; Eyles & Elliot-Major, 2021). But it is also true that the mere presence of a parent likely motivated and engaged students to undertake remote learning.

While there are small negative numerical differences in the home learning provision of children with lone parents compared with children who have more than one parent, these differences are not found to be statistically significant (Pensiero et al., 2020). There are similarities in the proportions of parents reporting that their child was home-schooled in May 2020: with 85% of single-parent households reporting their children were home-schooled, compared to 87% of households with more than one parent (Williams et al., 2020). There were also only marginal differences in the hours of schoolwork, hours of adult support and number of online lessons students took part in across single- and multiple-parent households (Pensiero et al., 2020). Overall, these findings indicate similarities in key aspects of remote learning across single and multiple-parent households, which contrast with earlier research that finds living in a single-parent household could hinder outcomes for the children that live in them (Hampden-Thompson & Galindo, 2015; Song et al., 2012). However, it should not be ignored that single-parent households are more likely to be supported by one income, and are therefore more likely to experience challenges in providing home-based resources (Benzeval et al., 2020). We discuss this further in the section, ‘Home learning resources’.

Where parents continued to work at their place of employment, students with siblings were more likely to have had caring responsibilities. Living arrangements such as this likely resulted in challenges to remaining focused on their school work (Impact Ed, 2020). Indeed, parents of older children who had a young sibling aged 0 to 4 were significantly more likely to say that their older child was struggling with remote learning because of caring responsibilities for their younger siblings (39% compared with 7% who had siblings in older age brackets, Williams et al., 2020). These parents were also most likely to report that their older child did not have a quiet place to study (41% compared with 13%).

Having siblings who were much older was beneficial to younger, primary-aged students as the older sibling often supported their younger siblings with school work. However, while this was beneficial for the younger siblings, for the older siblings this could distract away from their own learning (Pensiero et al., 2020). In contrast, for secondary school students with an older sibling, the younger sibling could be disadvantaged. This was because they often had to compete for resources, such as parental support and home-learning resources, such as computers and spaces to study (Pensiero et al., 2020). In general, having siblings undertaking remote learning in the same household was likely to reduce the degree to which students’ remote learning was successful. This is particularly likely where home resources, such as amount and quality of parental support, digital resources and places to effectively study, are limited. It is therefore expected that students with siblings in the least wealthy households had less effective home-learning experiences than those in the wealthiest households.

Home learning resources

Given that learning was taking place in the home for most students during the first lockdown, resources in the home were a larger influence on students’ learning. The main resources that parents, teachers and students reported were digital devices, access to the internet, access to study spaces and tutoring.

The move to remote learning with important aspects of it predominantly being online meant that digital devices and internet access within the home was more important than ever for students’ learning. Around 85% of secondary and 90% of primary students were reported as having access to a computer, laptop or tablet for their remote learning during the first lockdown (Andrew et al., 2020a), but there were many students who did not have suitable devices and internet access when schools and colleges closed in March 2020. Data from Ofcom’s Technology Tracker (2020) estimated that at the start of 2020, between 1.14 million and 1.78 million children in the UK under the age of 18 had no access to a laptop, desktop or tablet. They also estimated that between 227,000 and 559,000 students lived in households without internet access.

For those with access to digital resources, estimates indicate that around three quarters of secondary and post-16 students had access to their own device: either a computer or laptop (around 60-70%), or a tablet (around 10-20%; Andrew et al., 2020a; Pallan et al, 2021). For primary school students, expectedly, there was much less availability of personal computers and laptops. Around a third of primary students had access to their own device (Benzeval et al., 2020a), but many more had access to some form of digital device.

While around 25% of primary students used a computer or laptop as their main device when required, the predominant means of digital access for primary-aged students was via a tablet (40%). When considering the type of work that students were expected to take part in for their home learning, Andrew et al. (2020a) acknowledged laptops and computers seem to be the most useful devices for facilitating this. This is particularly the case for older students, considering that the work they would have completed typically involves more written text and complex structures, and therefore requires a device that can facilitate this type of work. The higher proportion of primary students using a tablet as their main device for their work also supports this idea, as primary-aged children received more paper-based worksheets, and online learning was largely used to catch up with their teacher or watch videos (Cattan et al., 2020; Lucas et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2020).

Although most students had access to devices for their remote learning, many are reported to have had to share them with family members (Child Poverty Action Group, 2020; Yeeles et al., 2020). Benzeval et al. (2020a) reports that more than half of students had to share their device with a family member (51%). This may be more of an issue for primary school students, as Andrew et al. (2020a) found that these students were more likely to share a computer and less likely to have access to their own device compared to secondary school students. Secondary students could be more likely to have their own devices and share with younger siblings, whereas younger siblings are more likely to have access only to someone else’s device. There were mixed impacts resulting from having to share remote learning devices (Pensiero et al., 2020). For primary school children, using a shared computer reportedly had no negative impacts on their learning. However, for secondary school children, sharing a device is reported to have been disruptive, with those sharing being less likely to take part in online lessons. However, for secondary students who did share devices they were more likely to receive more adult support (Pensiero et al., 2020).

Despite many students having access to suitable digital devices to undertake their remote learning, there was still a substantial number of students who did not. In May and July 2020, senior leaders and teachers reported that limited internet access was a significant challenge for around a quarter of students (Lucas, et al., 2020; Sharp et al., 2020), and around 4% of students overall were estimated to have had no access to a digital device at all during the first lockdown (Benzeval et al., 2020a). Using this and other sources, we can estimate that around 3-10% of students were accessing their remote learning using a mobile phone[footnote 2] (Andrew et al., 2020a; Pallan et al., 2021). Where students were using mobile phones to access their online learning, senior leaders raised concerns about how effective these would be (Andrew et al., 2020a). Although those students using mobile phones were able to access the learning content, this method was likely to be less conducive to learning than using a laptop, on account that the screen size and typing functionality of phones is greatly reduced (Andrew et al., 2020; Ofsted, 2021). This was likely problematic for being able to see the content of live lessons and videos, as well as for completing assignments, particularly those with large word counts or with more complex structures. Using mobile phones to access online learning is therefore likely to have been more disruptive to older students’ learning.

For students who did not have suitable digital devices at home, some schools were able to provide them. This provision was greatest in independent schools, where, as reported in May 2020, 38% of independent primary and 20% of independent secondary schools provided their students with devices, compared with 1% of state primary, and 7% of state secondary schools (Menzies, 2020). Access to digital resources was a key concern for schools and colleges at the start of the pandemic, and continued to be through to the autumn 2020 and spring 2021 terms. The government aimed to supply devices to children in the first lockdown to help with access to remote learning (Department for Education, 2020a), however there were delays and difficulties in achieving this (Education Policy Institute, 2020). By mid-June only 115,000 of the 200,000 devices that were ordered were delivered to local authorities or academy trusts (Department for Education, 2020a). The government further introduced the Get Help with Technology programme in January 2021 (Department for Education 2020b). However, access to digital devices with which to undertake remote learning was a concern that persisted throughout the 2020 spring, summer and autumn terms (we discuss this further in the section, ‘Teaching and learning in the 2020 autumn and 2021 spring terms’).

For some students, finding a suitable quiet space to work at home was also often challenging (Lucas et al., 2020). This was particularly the case for younger students. Around 20% of primary school students reportedly did not have a designated space to study at home, whereas this was the case for around 10% of secondary students (Andrew et al., 2020a; Andrew et al. 2020b). Those students without a suitable space to study found remote learning more difficult, and this had further negative implications for their motivation to study (Yeeles et al., 2020).

In addition to the remote learning provided by the school or college, some students received additional tuition. During the first lockdown, it seems that the majority of children were not receiving paid tuition. Andrew et al. (2020a) found that only 4% of primary students and 5% of secondary students spent any time with a paid tutor weekly. However, on average these students spent an hour and a half per day in tutoring. The uptake of additional tuition during the pandemic was most common from the autumn term, when there was more of a focus on identifying and recovering from lost learning. We discuss this further in the section, ‘The return to school in September 2020’.

Evidence indicates that there was variability in the degree to which home resources were able to effectively support remote learning. As is the general theme seen throughout this report, students who were most deprived tended to have home environments that were less conducive for remote learning. Disadvantaged pupils seem to have access to the fewest resources when learning at home. Child Poverty Action Group (2020) found that low-income families were twice as likely to report a lack of resources when supporting home learning, with 40% missing at least one essential resource. Students in the most deprived schools are less likely to have suitable IT access to engage in online learning remotely, in comparison with peers in the least deprived schools (Cullinane & Montacute, 2020; Sharp et al., 2020; Teach First, 2020). For instance, Lucas et al. (2020) found that the proportion of students with little or no IT access in the least deprived schools (19%) is half that of students in the most deprived schools (39%). Moreover, the most deprived students were around three times more likely to have used a phone or had no device to access schoolwork, compared to the least deprived students (Andrew et al., 2020c; Pallan et al., 2021).

Green (2020) found 20% of students eligible for Free School Meals (FSM) had no access to a computer at home in comparison to 7% of non-FSM students. This had further implications for teacher-student interactions, where students eligible for FSM were less likely to have their work checked by a teacher because they were unable to submit it.

Access to a quiet space to study at home also seemed to be a more prominent issue for disadvantaged students. Andrew et al. (2020a) found children from wealthier families are more likely to have access to a study space. Secondary school students in the poorest households were twice as likely not to have access to a study space (12%) compared with their counterparts in the wealthiest households (6%). For younger children, almost 60% of primary students in the least wealthy households did not have access to their own study space, compared with 35% of students in the wealthiest households (Andrew et al., 2020c). Similarly, in March to April 2020, it was found that around 29% of Pupil Premium students did not have a quiet area to study, compared with 16% of non-Pupil Premium students. Access to a quiet study space did not improve over the spring and summer terms (Cattan et al., 2021; Yeeles et al., 2020). Disadvantaged students were also more likely to have to share their quiet study space with others, and Pupil Premium students were more likely to report that the quiet study space in their home was not readily available for their use (Yeeles et al., 2020).

As well as being less likely to lack key resources, students in the least deprived families were most likely to benefit from learning resources above what they would usually experience. For instance, Eyles and Elliot-Major (2021) found parents in the highest fifth of incomes were over 4 times more likely (15.7%) to pay for private tuition compared to parents in the lowest fifth of incomes (3.8%). Where students from the least wealthy families did receive tutoring, they still received much less tutoring time (between 1-4 hours) than the wealthiest families (5 hours). Students from wealthier families are also reported to spend more time on remote learning because they are more likely to have better home learning conditions and resources to support this (Andrew et al., 2020c).

Schools and colleges offered various ways of supporting students over the first lockdown period. However, nationally available resources were not suited to students with special learning needs (Skipp et al., 2021). In addition, families of children with SEND often required specialist equipment to support their child in their home learning. Lack of suitable equipment was also an issue for apprentices. Doherty and Cullinane (2020) found that 37% of employers reported that some apprentices were unable to work from home because they did not have access to the equipment needed to continue working. Employers further report that 14% of apprentices could not learn from home due to a lack of internet or devices.

Of the households who were struggling to provide devices for their children, there was a disproportionate number of single-parent households (21%) compared with two-parent households (7%; Williams et al, 2020). However, struggling to access a device was not a universally held experience of students in single-parent households. A separate survey finds that a higher proportion of students with single parents have their own computer (59%) compared with students living in a household with more than one parent (44%; Benzeval, Booker & Kumari, 2020b). It therefore appears that there is a large range of experience in these contexts.

Student intrinsic factors

The previous sections discuss how school or college and home provision enabled, or disabled, students to continue their learning at home while schools and colleges were closed in the 2020 spring and summer terms. Another important element to learning centres on students’ internal responses. In particular, here we discuss findings from the literature regarding students’ engagement with learning during lockdown, and the roles of well-being and motivation to learn in this.

Many children and young people found the transition to life in lockdown difficult, particularly from a mental health and well-being perspective (Pallan, et al., 2021; The Children’s Society, 2020a, 2020b). There were many factors about living under lockdown restrictions, online learning and being unable to socialise with friends, that were reported as detrimental to students’ mental health, well-being and desire for learning.

Many students reported that increased screen time associated with online learning led to headaches, burnout and stress (Müller & Goldenberg 2020a, 2020b, 2021; Open Data Institute, 2020). Although many reported enjoying the flexibility of offline learning (Muller & Goldenberg), the lack of structure and routine could be difficult to navigate. For instance, some students reported being unmotivated or having no discipline to study, while others, particularly girls, lacked the discipline to restrict learning to normal school hours and often worked longer than they would usually, compared with boys (Impact Ed, 2020; NSPCC, 2020; Müller & Goldenberg, 2020b; Open Data Institute, 2020; Young Minds, 2020a).

Many young people also reported feeling stressed and anxious about different aspects of their life. This included worries about school work, family and homelife and the pandemic, and some were also experiencing bereavements (Child Poverty Action Group, 2020; Impact Ed, 2020; Mountford-Zimdars & Moore, 2020; Open Data Institute, 2020; The Children’s Society, 2020a; Young Minds 2020b). Overall, the evidence indicates that school closures had direct and large negative impacts on students’ mental health and well-being. This had important implications for their remote learning.

Analysis of survey data shows that there was a positive correlation between students’ well-being and learning during the pandemic (Impact Ed, 2020). This means that those reporting better well-being were also engaging more with their learning, and vice versa. In separate studies, more than half (53%) of students reported they were struggling to continue with their education during lockdown, and more than three quarters of students (77%) reported that learning from home was much more difficult than learning at school (Williams et al, 2020; Yeeles et al.,2020). The most common reason given for why students were struggling was lack of motivation (Williams et al, 2020), and when asked to describe their day-to-day life in three words, around a third of students (31%) expressed boredom and around a fifth (18%) described life as repetitive (Yeeles et al., 2020).

The largest source of evidence relating to students’ engagement with learning during the first few months of lockdown is a survey of over 3,000 teachers and senior leaders conducted in May 2020 (Lucas et al., 2020). When asked about the degree to which students were completing work set by the school or college, teachers reported that on average, they are in regular contact with around 60% of students, but that less than half of students had returned their last piece of set work (42%). Student’s own reports of their learning indicate widespread disruption (Pallan et al., 2021). Almost all surveyed – 96% – reported they were not learning at their normal level. They, on average, rated their learning at 61% or what it usually was.

Senior college leaders reported that engagement was lower for certain students. Adult learners found it more difficult to continue their learning because of competing homelife priorities, and students studying practical subjects were restricted in continuing the hands-on aspects of the course (Association of Colleges, 2020).

The degree to which students engage with their learning is only partly impacted by their well-being and motivation to learn. Their ability to access learning, the amount of parental support, and provision given by the school or college must also be considered. The overwhelming evidence indicates that the most deprived students are less likely to have internet access, digital resources, parental support and quality learning resources from the school (as previously discussed in the section, ‘Home learning provision’). Indeed, differences in the degree to which students from different backgrounds were engaged with their learning are reported.