Life Chances Fund Evaluation - second report on Kirklees Better Outcomes Partnership

Published 31 August 2023

Applies to England

Executive Summary

This is the second interim evaluation report on the Kirklees Better Outcomes Partnership (KBOP) social impact bond (SIB). You can read more about KBOP and SIBs on the Government Outcomes Lab website. This study is part of a series of evaluations on SIBs, investigating the impact of commissioning services through a SIB instead of other commissioning approaches. The KBOP SIB receives additional funding from the Department for Culture, Media & Sport’s (DCMS) Life Chance Fund (LCF). Read more about the LCF

Aim of the impact bond partnership

The KBOP SIB service seeks to improve outcomes for adults with housing-related support needs in:

- education, training and employment (ETE)

- accommodation

- health and wellbeing

Structure

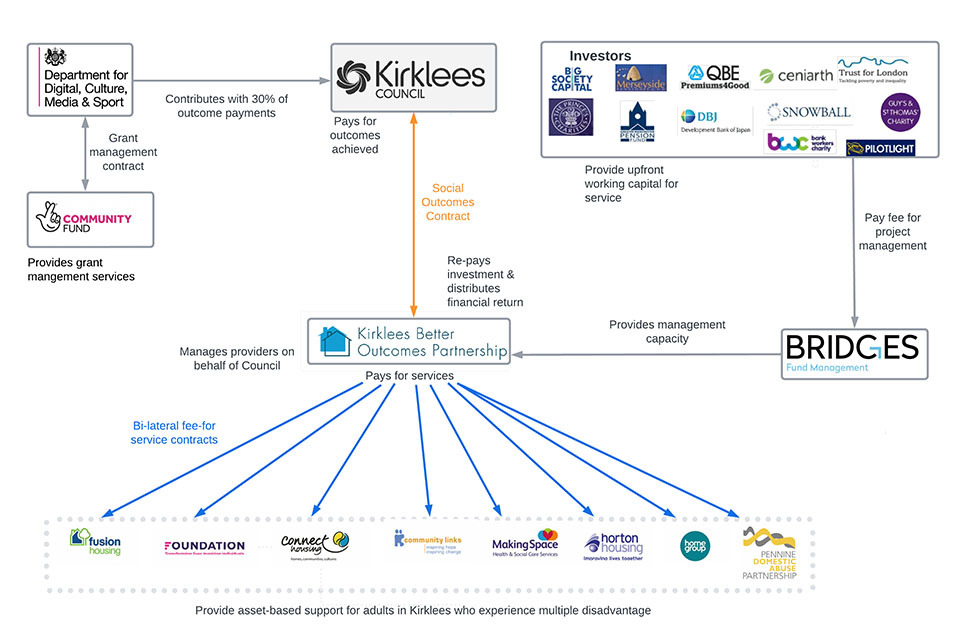

In the KBOP SIB, payment is based on achieved outcomes (defined in a pre-agreed rate card). Service delivery is managed by an investor-owned social prime contractor. Kirklees Council holds the social outcomes contract with the social prime. The social prime holds bi-lateral fee-for-service contracts with eight social sector providers.

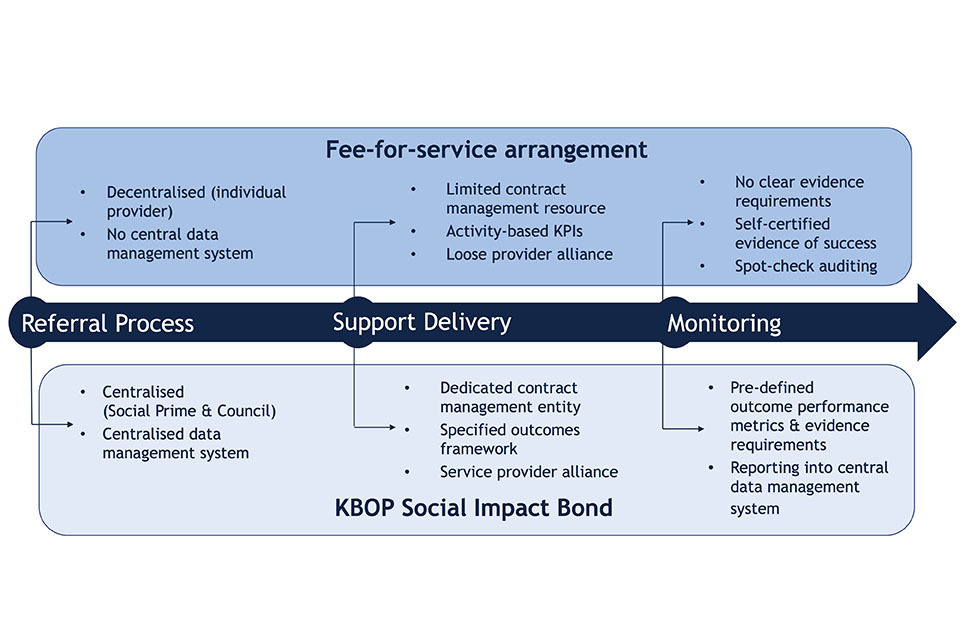

The KBOP evaluation compares this SIB with the previous commissioning approach, a fee-for-service model.[footnote 1] Both services have been delivered by the same providers, offering a valuable evaluation opportunity. The KBOP SIB service is a dynamic and adaptive system, and the research team understands that practice may have evolved since data was collected for this report.

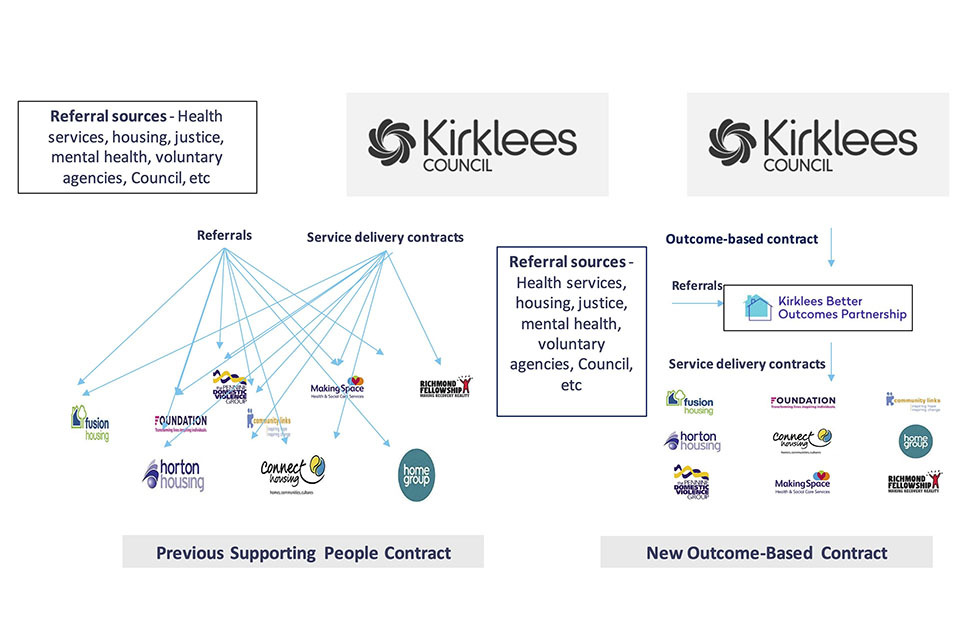

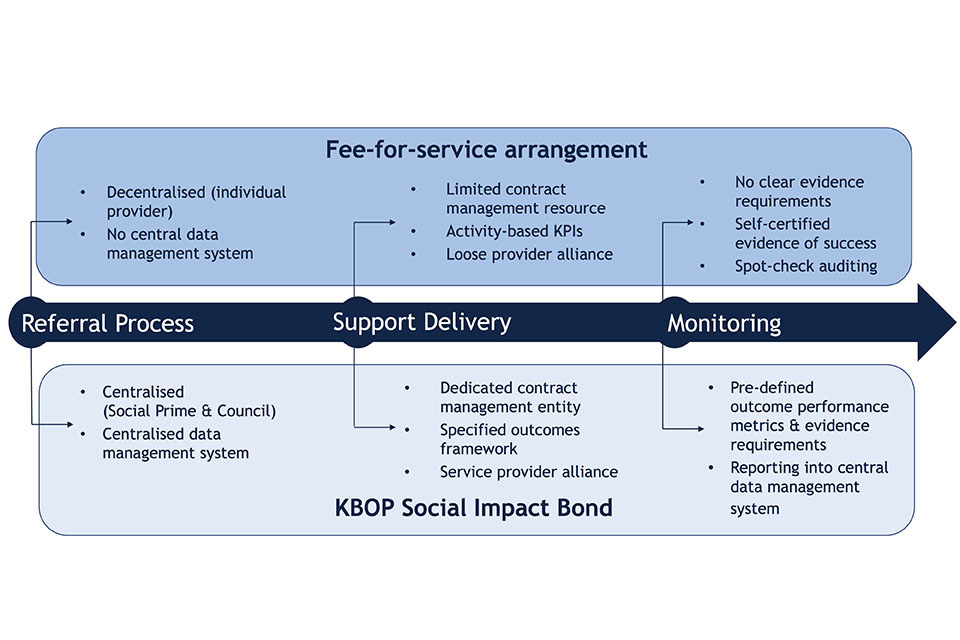

Figure E1: Key differences between the fee-for-service arrangement and SIB model

Hypotheses

This evaluation examines four hypotheses developed in the first interim evaluation of the KBOP SIB. These capture the mechanisms potentially underpinning SIB delivery.

The four mechanisms are:

-

enhanced market stewardship

-

enhanced performance management

-

enhanced collaboration

-

enhanced flexibility and personalisation

Enhanced market stewardship

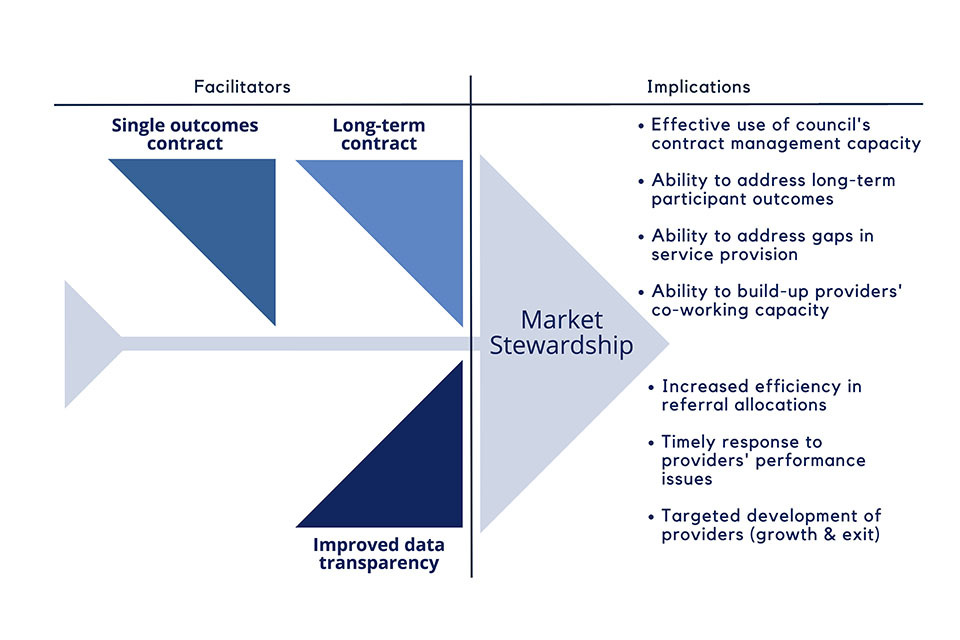

The KBOP SIB model creates a dedicated team for developing service insights and managing provider performance. A hypothesis developed in the first stage of the evaluation is that the SIB would respond to limited ability for Kirklees Council to shape services or support a thriving set of service providers by more proactively stewarding the market.

Under the SIB arrangements, we found that council staff set the vision of a high functioning, person-centred and outcome-oriented service and were able to identify opportunities to reduce system barriers.

The KBOP SIB model resulted in:

- The council team being spread less thinly over a large number of contracts.

- Expanded and more granular data on service participants and service outcomes. The outcomes contract has adopted a data-led performance management approach. Service providers are encouraged to develop service pilots, address gaps in provision and build-up co-working practices.

- Improved data availability and case management tools allow for more efficient referral allocation, a quicker response to provider performance issues, and more targeted provider development.

I think if we had that many staff, we would probably have been able to manage the relationship [i.e. the service provider contracts]. The problem …was that we had nowhere near that resource to be able to focus that much on performance and quality management at all. So, it’s part of that infrastructure question as well, isn’t it? … Well, does that infrastructure add value?

– Senior council contract manager

Figure E2: Facilitators of enhanced market stewardship and delivery implications

Enhanced performance management

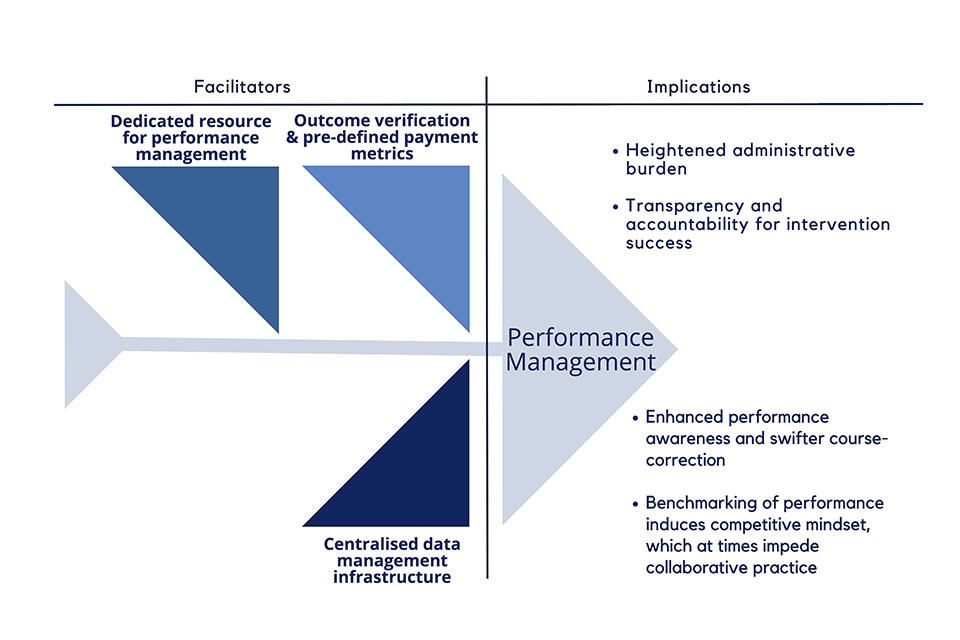

The KBOP SIB introduces a more intensive and data-led approach to performance management and benchmarking compared to the fee-for-service predecessor. A hypothesis developed in the first stage of the evaluation is that the SIB would respond to misaligned and inconsistent performance metrics and a process-driven performance management approach.

We found that the KBOP SIB introduced a person-level set of pre-defined payment metrics, provided a dedicated resource for more engaged performance management and secured a central intelligence system.

I think services are definitely much more accountable. There’s no hiding place. You can’t hide within this contract because everything you do, [the Social Prime Data and Operations Analyst] knows what I’m doing. There’s nowhere to hide. There are no tricks, it’s just there in numbers they can see what we’re doing and they can see in conversations and how things get written in CDPSoft [central intelligence system], conversations that people have.

– Service manager

This meant that:

- In contrast to the fee-for-service contracts which experienced misaligned and inconsistent metrics for tracking performance, the SIB’s payment-for-outcomes mechanism has a formal outcome verification process with clearly defined payment metrics and evidence requirements.

- Service providers saw increased administrative burden. However, data collection became easier over time, with improved service intelligence facilitated through a central data management system.

- Providers are able to respond more swiftly to performance issues, and there is improved transparency and accountability for success.

Figure E3: Facilitators of enhanced performance management and delivery implications

Enhanced collaboration

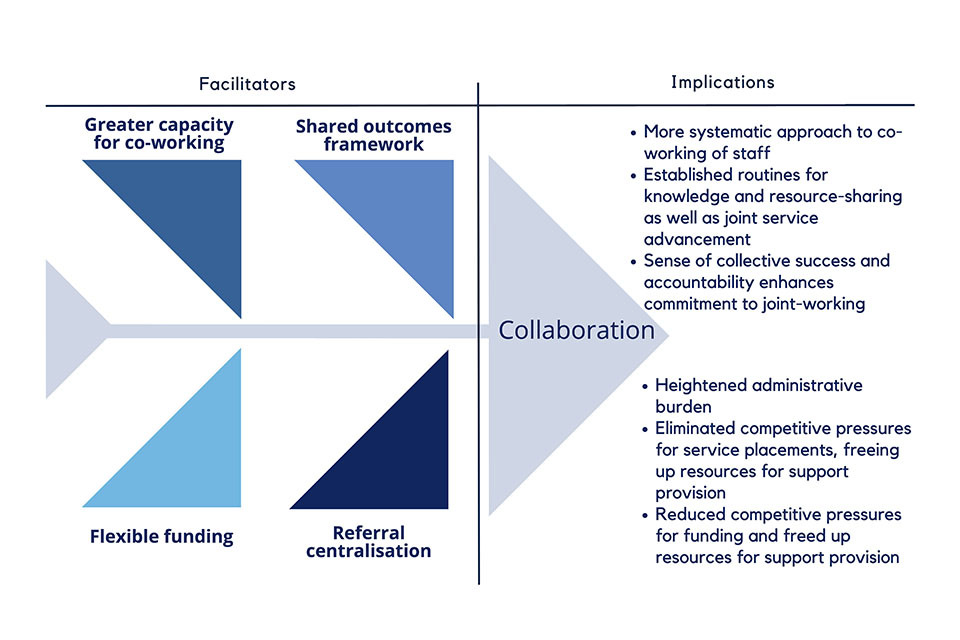

The KBOP SIB is associated with enhanced collaboration between service providers. A hypothesis developed in the first stage of the evaluation is that the SIB would respond to the lack of co-working practice and perceived competitive pressures through an improved collaborative infrastructure and a shared outcomes framework.

This more intentional approach to cross-provider collaboration is demonstrated in a number of ways:

- The SIB features a greater capacity for co-working through the creation and facilitation of a collaborative infrastructure by the social prime.

- The overarching outcomes framework created a shared mission across providers and a sense of collective success that seems to dilute competitive pressures.

- Although there is a greater sharing of knowledge, best practice and resources, some hesitance remains from the perceived competitive pressures in benchmarking providers’ key performance indicators.

I can see that we are working more consistently as a group of providers, [which] I think is a benefit. Because it helps with a benchmarking and an expectation around what we’re delivering. And that helps with a consistency of the service and the level of service and the quality that we might expect. Whereas I don’t think that there was any mechanism for that with the group of contracts previously.

– Provider senior operations manager

Figure E4: Facilitators of enhanced collaboration and delivery implications

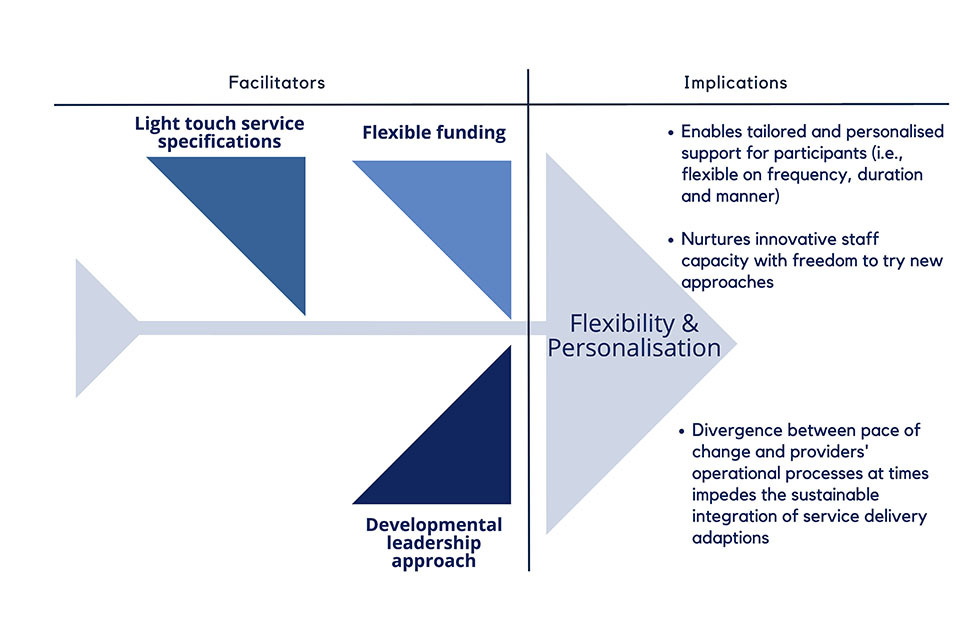

Enhanced flexibility and personalisation

The KBOP SIB allows for greater flexibility and personalisation. A hypothesis developed in the first stage of the evaluation is that the SIB would respond to limited flexibility and personalisation in delivery through reducing service specifications, while ensuring accountability for outcomes.

At the frontline, this created both opportunities and challenges:

- While the previous model allowed for limited flexibility or personalised support in service provision, the KBOP SIB’s outcomes contract and provider contracts have light-touch specifications.

- The SIB’s ‘strengths-based approach’ to frontline provision encourages staff to offer flexible, personalised support and supports innovation in service provision.

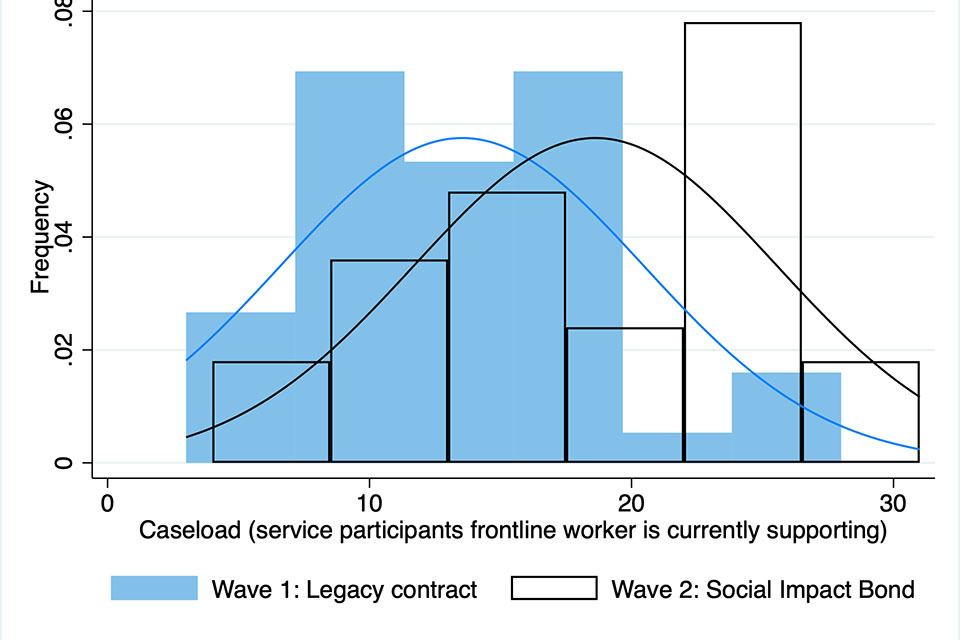

- A key tension between the outcomes-focused and person-centred approach, experienced by some providers, was found in the significantly increased caseload, alongside a decreasing percentage of staff time spent with service users in an average week. However, this is not straightforward to interpret, as the caseload estimate does not account for a shift towards longer-term support, with variation in intensity depending on user need at a given time.

- The highly flexible funding and developmental leadership approach nurtures frontline staff’s innovative capacity.

- However, high caseloads sometimes impede person-centred delivery and, along with a focus on longer-term outcomes, require service managers to allocate case work more strategically to achieve a balanced caseload of intensive and light-touch support.

But it is refreshing for people to say ‘We are not focused on how you achieve these outcomes, just do what you need to do and if you want to talk to us about something, that’s fine. If you’ve got a new idea, that’s fine. Even if you think it might cost money, if it will get some of these outcomes again, let’s have that conversation.’ That’s something you don’t get with other funders as much.

– Provider Service Director

Figure 5: Facilitators of enhanced flexibility and personalisation and delivery implications

In addition to these four hypotheses, this evaluation also found that the KBOP SIB model resulted in a ‘spillover’ on the wider local delivery network:

- The KBOP project director led in building cross-sector collaboration, which extends beyond the immediate KBOP delivery network to overcome siloed working and service fragmentation. For example, the KBOP director jointly developed a pilot between the council and justice system to improve support to ex-offenders in accessing accommodation.

- There was more focused communication of frontline issues to policy-makers.

- The long-term contract duration allowed time to build sustained relationships.

If KBOP is going to work, we can’t just deliver our own service. We have to go out and change the way all these other services interact with the people we’re trying to help.

– Investment Fund Director, Bridges Fund Management

These interim findings suggest that, in contrast to the previous fee-for-service model, the KBOP SIB has led to enhanced market stewardship, performance management, collaboration, flexibility, and personalisation.

Simultaneously, it is important to acknowledge that while the SIB is associated with a variety of beneficial changes to public management practice, the research also suggests a heightened administrative burden, linked to enhanced reporting requirements and management meetings, and an increased caseload. It is also important to note that the research team is aware that, at the time of concluding the report, the KBOP social prime was trying to mitigate some of these issues.

1. The Life Chances Fund evaluation

1.1 About the Life Chances Fund

The Life Chances Fund (LCF) is a £70m fund launched by the UK government to support the growth and development of outcomes-based commissioning through the use of social impact bonds (SIBs), commissioned by local public sector organisations in England.[footnote 2] Here, central government applies outcomes-based commissioning as a public service reform tool with the objective to foster co-payment by different commissioners.

LCF projects aim to tackle complex social problems across policy areas like child and family welfare, homelessness, health and wellbeing, employment and training, criminal justice, and education and early years. Following three application rounds, funding was made available for multi-year SIB projects, as the LCF runs for nine years from July 2016 to March 2025. The first LCF projects began service delivery in 2018, with the bulk of projects launching between 2019 and 2020. Whilst all projects will receive the last of their LCF funding by March 2025, and most will be finishing delivery before this, some projects are planning to continue delivery under a SIB beyond this time, backed by a local commissioner. The LCF is administered by The National Lottery Community Fund (The Community Fund, formerly known as the Big Lottery Fund) on behalf of the Public Sector Commissioning Team (formerly the Centre for Social Impact Bonds) at the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS).

The LCF has the following objectives:

- increasing the number and scale of SIBs in England

- making it easier and quicker to set up a SIB

- generating public sector efficiencies by delivering better outcomes and using this to understand how and whether cashable savings can be achieved

- increasing social innovation and building a clear evidence base of what works

- increasing the amount of capital available to a wider range of voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) sector providers to enable them to compete for public sector contracts

- providing better evidence of the effectiveness of the SIB mechanism and the savings that are being accrued

- growing the scale of the social investment market.

Detailed information (including visualisations) on individual LCF projects can be found on the Government Outcomes Lab’s website.

1.1.1 What are social impact bonds?

Social Impact Bonds are a subset of outcomes-based contracting (OBC). The UK government has been experimenting with OBC as a commissioning approach through which to improve the outcomes of public services, by linking the payment made to non-government service providers to pre-agreed, measurable outcome achievements.

In its most basic form, a SIB is a tripartite relationship between:

- a government commissioner (often central or local government) who defines social outcomes and expresses a willingness to pay for them

- a service provider (usually from the VCSE sector) who delivers an intervention or programme of support with the people using services

- an investor (typically social or philanthropic), who covers the up-front costs of the intervention in order to achieve social impact and make a financial return on their investment if payable outcomes are successfully achieved (Disley et al., 2011; Fraser et al., 2018).

1.1.2 What is the Life Chances Fund evaluation?

A key contribution of the LCF evaluation is to clarify whether, where, and how SIBs add value when compared to more conventional public service commissioning arrangements. Although a series of SIB evaluations have been carried out previously, most of these evaluations have focused on the implementation or efficacy of specific interventions (i.e. the particular service funded by the SIB), often without robust quantitative impact evaluation (Carter et al., 2018; see also Fox & Morris, 2019). As part of a unique partnership between DCMS and GO Lab, the LCF is an opportunity to undertake collaborative, robust evaluation to help improve future policy and practice.

The Government Outcomes Lab is responsible for the project-level strand of the LCF evaluation, which evaluates the impact, process and value for money of LCF SIBs and compares the SIB model to alternative commissioning approaches.[footnote 3] Our research aims to respond to current evidence gaps by focusing specifically on SIBs as a tool for public service delivery and reform rather than centering only on the intervention effect. The ambition is to assess ‘the SIB effect’ – that is, the influence of this commissioning model on social outcomes. In pursuing this research, the GO Lab and DCMS hope to offer crucial thought leadership in the outcomes-based-commissioning landscape.

1.2 The LCF supplementary evaluation and this report

To gain an understanding of the impacts of services commissioned through a SIB, compared to alternative commissioning approaches, the Government Outcomes Lab research team conducts a series of a longitudinal in-depth analyses with a small number of LCF SIB projects (referred to as the ‘supplementary evaluation’).

The Kirklees Better Outcomes Partnership (KBOP) evaluation is nested within the ‘supplementary evaluation’ stream. This evaluation site has been identified as a particularly valuable learning opportunity, since Kirklees Council previously commissioned the set of service provider organisations who are currently operating under the SIB to deliver comparable provision under a fee-for-service contracting arrangement. The online glossary contains a definition for this and other key terms.

Specifically, the evaluation of the KBOP SIB focuses on three research questions:

-

What is the quantitative impact of services commissioned by the KBOP SIB on the targeted social outcomes?

-

Through what mechanisms do specific aspects of the KBOP SIB contribute to these impacts?

-

Do the benefits of the KBOP SIB approach outweigh any additional costs associated with this model, when compared to legacy contracting arrangements? And, if possible, what is the cost benefit analysis of the SIB?

This is the second report of a longitudinal process evaluation which seeks to investigate the ‘SIB-mechanism’ (research question two). The SIB itself is studied as a complex intervention, with its own theory of change. The overall evaluation compares the two intervention approaches, i.e. the SIB and fee-for-service commissioning approach. The first report focused solely on the legacy fee-for-service contract. Research conducted prior to the adoption of the SIB in 2019 provided an in-depth analysis of the implications of a fee-for-service contract on service management and delivery. In addition, this first research phase was used to develop a preliminary set of hypotheses through which the SIB model might shift management approaches and practices by the council and providers and influence frontline service delivery. This second report uses the hypotheses from the first report to explore the ‘mechanisms’ of the KBOP SIB.

The remainder of the report is structured across six overarching sections:

- Section 2 sets out the research method

- Section 3 describes the KBOP SIB service and its ‘counterfactual’, the preceding fee-for-service contract

- Section 4 summarises the KBOP SIB’s contractual framework

- Section 5 outlines the KBOP SIB’s governance

- Section 6 presents four hypotheses through which the SIB model reforms and shapes management and frontline delivery practice

- Section 7 examines the effect of the KBOP SIB on the wider Kirklees service ecosystem

- Section 8 offers concluding remarks, recommendations for policy and outlines future research within the KBOP SIB evaluation

2. Research method

This report is the second written output within a mixed-method longitudinal research programme. The analysis that underpins this report is informed by a process evaluation which investigates service development and key changes that have occurred subsequent to the adoption of a SIB commissioning arrangement in Kirklees.

2.1 Data collection

For the portion of the evaluation described in this report, 38 semi-structured expert interviews[footnote 4] were conducted between October 2021 and January 2022[footnote 5]. Participants were selected using purposive sampling to ensure the involvement of experts from across the SIB partnership and to allow for in-depth insights regarding the design, management and delivery of the SIB service. Alongside this, snowball sampling was used to ensure representation from a similar number of stakeholders across different types of organisations involved in the KBOP SIB. Interview participants consisted of representatives from the social investment fund manager (4); the social prime ‘KBOP’ (9), service provider (19) and council contract managers (3); the Chair of the SIB governance board, an independent consultant to the council and a pro-bono legal advisor to the investment fund manager.[footnote 6] The table in Appendix A provides an account of the organisational affiliation and role of the interviewees.

A similar interview protocol was used for the different stakeholder groups. The question design was informed by the initial set of hypotheses derived from the first evaluation report. The focus area of the protocols varied depending on the specialist expertise of research participants. The interview guides included the following seven themes:

- contract and rate card design

- governance arrangements

- contract and performance management

- relationship development

- experiences of SIB service delivery

- systems change

- forward view on SIB development

Interviews were either conducted remotely (31) or face-to-face (7). All interviews were recorded and transcribed. Interviews lasted on average 69 minutes. The research is endorsed by the University’s ethics review process and further details are available in Annex C.

In addition, the research draws on an extensive analysis of 154 documentary data items sourced from all SIB partner organisations, the LCF’s central administrative data portal and the external consultant to the council. Key documentary data include the social outcomes contract (council-KBOP), provider contracts (8) (KBOP-service providers), different versions of the rate card (7) and associated background documents (2) as well as documents linked to service management (7), e.g. audit and operational manuals.[footnote 7] Analysis includes key meeting minutes and presentations by the social prime, including the monthly performance review meetings (70) from the SIB launch until the completion of data collection in March 2022. Service providers shared examples of performance reports and service reviews (9). KBOP’s governance framework and the job advertisements for the KBOP management team (5) supported the analysis of the SIB’s governance model.

2.2 Data analysis

Qualitative data analysis was conducted using ATLAS-ti software. Data coding was conducted using a thematic analysis (Ryan & Bernard, 2003) to unfold the central features of the SIB model, i.e. the ‘SIB mechanisms’, shaping frontline delivery and the wider service ecosystem in Kirklees. Data coding followed the Miles et al. (2014) two-phased coding approach:

Phase 1: During the first data analysis cycle, a deductive coding approach was applied. Codes developed from the initial set of hypotheses on the ‘SIB mechanisms’ from the first evaluation report were used to break down the data into discrete parts. Complementary, structural coding was applied to categorise major themes not included in the hypotheses (Saldaña, 2021).

Phase 2: In the second cycle, an inductive coding approach was applied to expand the initial top-level codes with a list of more granular sub-codes. The sub-codes were generated using either descriptive or axial coding (Saldaña, 2021); the latter method describes a code’s properties and dimensions and enables an exploration of how the code and its sub-codes relate to each other.

2.3 Limitations

The study is not without limitations. First, the findings are specific to the KBOP SIB and not all findings are generalisable to other SIB projects. Second, some research participants might have a vested interest in seeing the partnership continue after expiration of the LCF programme and this may encourage a positive response bias. The incorporation of the perspectives of local government commissioners and documentary analysis mitigates this. Third, four out of the total of 20 provider interview participants had not been involved in the pre-SIB contract (i.e. they were not involved in the delivery of services in Kirklees before September 2019). While these research participants were able to reflect on their SIB delivery experience with reference to other block contracts, they were not able to specifically compare the KBOP SIB with the preceding fee-for-activity floating support service in Kirklees. Finally, this report does not include interviews with frontline delivery staff or service participants.[footnote 8]

3. Introduction: The KBOP SIB and its counterfactual

3.1 The KBOP SIB ‘counterfactual’: the previous fee-for-service contract in Kirklees

In Kirklees, the provision of services for adults with housing-related support needs has previously been commissioned as a housing Floating Support service under the umbrella of the Supporting People programme, a national grant programme launched in 2003. It was expected to function as a preventative service by supporting participants to sustain independent living and avoid tenancy issues. Importantly, these legacy contracts did not explicitly set out to support participants into training or employment.[footnote 9]

The Floating Support service sat alongside accommodation-based services which delivered interventions for people who are homeless. Support was delivered on a 1:1 basis for a specified number of hours per week and support intensity was adjusted to participants being ‘low, medium or high risk’. The intervention duration was limited to 12 months (initially 24 months) due to funding cuts. In early 2019, the services were delivered by the same nine voluntary sector provider organisations, which then became delivery partners in the KBOP SIB.

Before the launch of the SIB, the Floating Support service in Kirklees involved 15 individual contracts managed by three council contract managers. The payment to providers was made monthly in advance as a block fee. There was no central intelligence system and limited standardisation in referral processes or case management. There was no standard definition or evidence required for the independent living outcome. Providers were only required to record this in the Support Plans which were subject to occasional file auditing. Likewise, the sustainment of the outcome was not part of the contracts’ key performance indicators.

3.2 The Kirklees Better Outcomes Partnership SIB service

The KBOP SIB seeks to improve accommodation, employment, stability and wellbeing outcomes for vulnerable adults who are in need of support to live independently.[footnote 10] Participants may face multiple challenges, including homelessness or the immediate risk of becoming homeless, mental health or substance misuse issues, experience of domestic violence and offending.

The service is commissioned by Kirklees Council, who initially defined the outcome measures that feature as payment triggers in the KBOP SIB. The upfront capital for service provision is sourced as social investment and is managed by Bridges Fund Management, a private investment fund management company. Ongoing funding is generated from the outcome payments. The investor-owned social prime (henceforth, the Kirklees Better Outcomes Partnership (KBOP) social prime) is a newly constituted organisation, responsible for the overall coordination of the delivery arrangement.[footnote 11] Kirklees Council holds a contract (referred to as a ‘social outcomes contract’) with the KBOP social prime, and this contract defines the conditions and outcome measures that direct payment to the social prime. The payment is based on a pre-defined sum for each outcome achievement, measured at the level of individual programme participants.

Following the introduction of the SIB, the KBOP social prime holds bi-lateral contracts with eight (formerly nine) provider organisations. These contracts feature key performance indicators that are tailored to each provider. Payment to the service providers is based on a monthly fee, paid in arrears.[footnote 12] The initial distribution of the contract volumes (i.e. the number of service participants engaging with each delivery organisation) was based on the preceding fee-for-service contract; two of the eight providers share a significantly higher contract volume.[footnote 13]

Within the KBOP SIB, the service is delivered by the same voluntary sector organisations that were involved in the provision of the pre-SIB Floating Support service. However, one provider organisation dropped out of SIB service delivery after nine months; the contract was terminated by mutual consent between the provider and the social prime. The majority of the provider organisations deliver general housing-related support, while one provider offers specialist support for mental health and another offers specialist support for people experiencing domestic abuse (details of the participating providers are available in Annex B). The legal structure of the delivery partners features housing associations (2), charities (4) and not-for-profit organisations (2); the organisations operate on a local (3), regional (3) and national (2) scale.

The KBOP SIB service launched on 1st September 2019 and will end on 31st March 2024. The total estimated maximum outcomes payments are £22.30 million. Kirklees Council receives a partial contribution of 30 % of the total contract value towards the outcomes payments from central government through co-funding via the Life Chances Fund.

Under the KBOP SIB, participants are allocated to service providers through a central referral hub, managed by the social prime. Personalisation is a key element to service provision, which is based on a strengths-based approach seeking to transfer greater power to participants.[footnote 14] The ambition (from both commissioners and the KBOP team) is to disrupt a perceived deficit culture of ‘fixing’ by shifting the focus from participants’ deficiencies to their strengths. Providers are granted greater flexibility in the mode of support provision compared to the legacy contract. There is no prescribed length or frequency of support. The case is closed once the participant has achieved all relevant outcomes; after case closure the participant can still re-access the service. However, outcomes can only be claimed once for each participant. Alongside the floating support service, KBOP offers a triage service for vulnerable people who only require a one-off support.

Participant data, including outcome achievements, referral assessment and support plan are saved on a central intelligence system (CDPSoft), administered by the council and granting full accessibility to the KBOP social prime; whereas providers can only access their own data.[footnote 15] The outcome claims and verification process involves two steps: providers upload the evidence for outcomes – under the supervision of the KBOP social prime - into the CDPSoft system. Evidence requirements for the outcomes are defined in the rate card, an annex to the outcomes contract. Then, the council team verifies the provided evidence and pays the pre-defined outcome payment to the social prime. The council has the right to withhold the payment in situations where the evidence is considered insufficient.

Table 1: Comparison of key contract features

| Contract Features | Fee-For-Service Contracts | Social Outcomes Contract |

|---|---|---|

| Contract parties | Kirklees Council and provider organisations | Kirklees Council and KBOP social prime (investor-owned social purpose vehicle) |

| Contract management responsibility | Kirklees Council | Kirklees Council |

| Payment mechanism | Monthly advance block payment | Monthly outcomes payment (i.e. payment is contingent on achieved outcome number and type) |

| Key performance indicators (KPIs) | Service Utilisation, Throughput, Independent Living | Accommodation, Education, Training & Employment, Health & Wellbeing, Financial Resilience |

| KPIs require sustainment of outcome achievements | No | Yes |

| Auditing | No pre-defined evidence requirements; spot checks of qualitative evidence (e.g. workbooks) | Pre-defined evidence requirements; council audits every outcome |

| Contract duration | Max. 2 years | 5 years |

Figure 1: Stakeholders’ responsibilities in the Kirklees Better Outcomes Partnership SIB

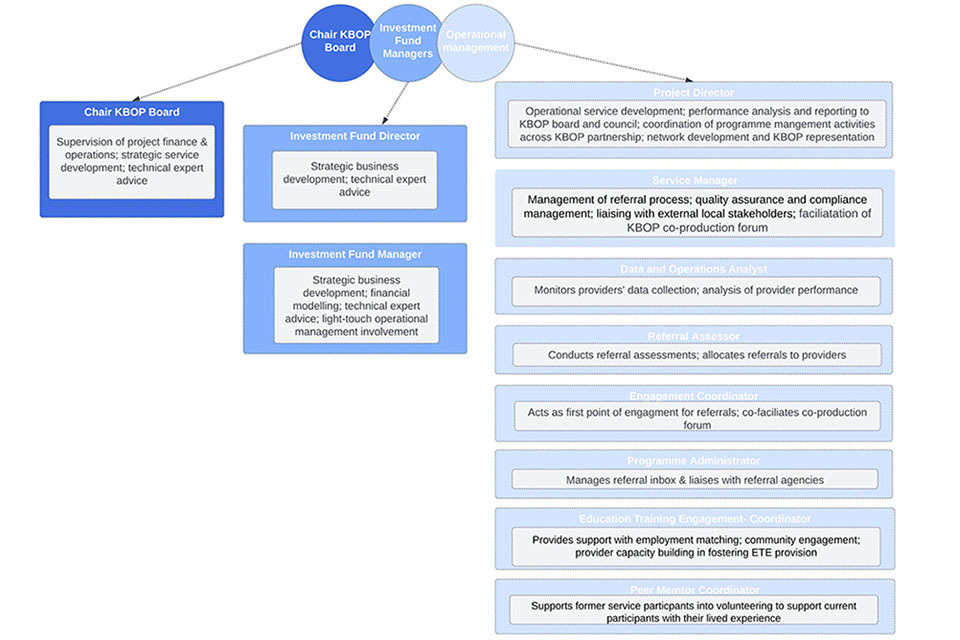

Figure 2: The managerial structure of the KBOP social prime

4. The SIB’s contractual framework

The KBOP SIB features two contract types: the social outcomes contract between the Kirklees Council and the KBOP social prime; and the bilateral service delivery contracts between the social prime and the individual provider organisations. This section draws on documentary analysis (especially contracts) to offer a description of the different contractual phases of the social outcomes contract. Next, it provides an overview of the rate card and rate card development, as this is a key element for the social outcomes contract. This is followed by an exploration of three areas:

-

The contractual levers for performance management

-

The role of the social outcomes contract in facilitating enhanced performance management, collaboration and flexibility

-

The social outcomes contract as a potential example of a relational contract.

4.1 The contractual phases

The social outcomes contract divides the SIB programme into a mobilisation and an operational period. Due to Covid-19, the initial programme had to be adjusted. The following section provides a description of the initial programme structure, illustrating the envisioned transformation of services from the fee-for-service to the SIB commissioning model.

Contract mobilisation started six months prior to the service launch in September 2019. It included the development of an operational infrastructure and the negotiation of the provider contracts. Alongside this, the investment fund managers prepared the providers for SIB delivery. Training was provided on technical aspects such as the new KPIs and outcome evidence requirements, aiming to help providers understand the value of these additional requirements. Providers appreciated their early involvement, as a Regional Head of Operations noted:[footnote 16]

The experience in developing the SIB model has been extraordinarily positive, in the respect that the management team involved in the SIB at Bridges have been very collaborative in their approach.

The “Operational Period” of the outcomes contract marks the beginning of the SIB service delivery. In the first year of the contract, the KBOP social prime and the providers were shielded from the implementation of a performance improvement plan (referred to as a ‘formal action plan’) and contract termination emanating from service failure or negative outcomes assessment.[footnote 17] The investment fund manager described this as a “grace period” to align service delivery to the new contractual structures.

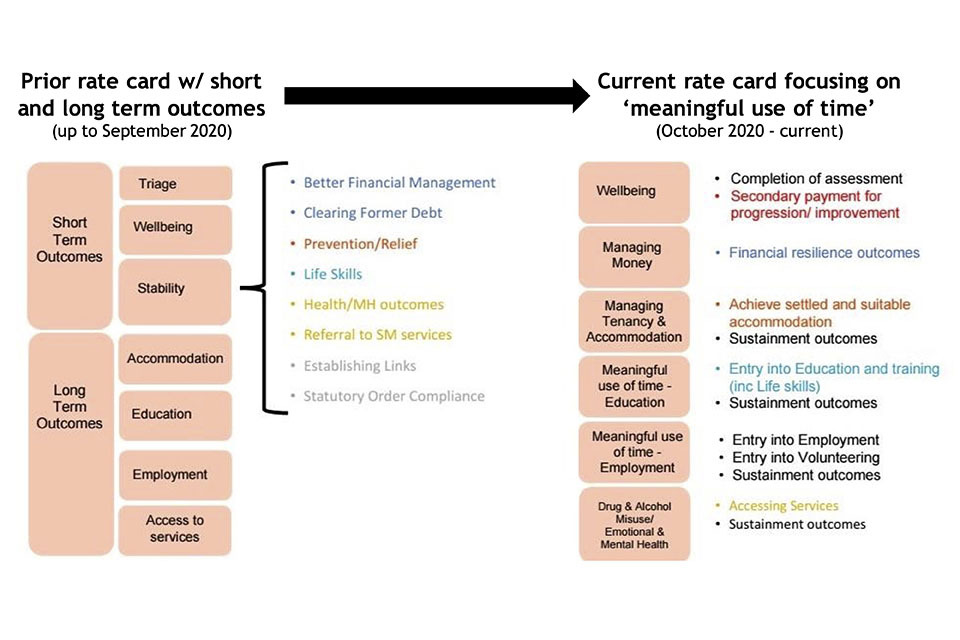

4.2 The rate card

A key element of the social outcomes contract is the rate card. A rate card is a schedule of payments for specific, pre-agreed outcomes that an outcome payer (in the KBOP SIB, Kirklees Council and LCF) is willing to make for each participant, cohort or specified improvement that verifiably achieves each outcome. The following section provides an overview of the outcomes and associated evidence requirements of the KBOP SIB. It also outlines the process for the design and re-design of the rate card and the rationale for the changes.

The outcome measures in the rate card provide an overarching set of shared success indicators for all providers of generic housing-related support.[footnote 18] A different rate card is used for a specialist provider for domestic violence (Pennine Domestic Abuse Partnership, PDAP).

The KBOP SIB seeks to improve participants’ outcomes in the following fields:

- Wellbeing

- Accommodation

- Education, Training and Employment (ETE)

- Emotional and Mental Health

- Drug and Alcohol Misuse

- Domestic Violence

To incentivise providers to work with service participants towards a long-term change, outcome payments are split between the initial achievement of the outcome (e.g. entering accommodation) and sustaining the outcome over a specific period of time (e.g. sustaining accommodation over six months). The outcome payment level increases the longer the outcome is sustained (e.g. £500 for ‘entry into employment’, £2,200 for ‘26 weeks of sustained employment’), to align incentives between the financial payment mechanism and the achievement of long-term outcomes. Evidence requirements vary and include self-certification forms (see Appendix I).[footnote 19] The self-certification of outcome measures allows providers to ask service users to declare the achievement of given outcomes; for instance, for the outcome ‘entering into employment’, service users are allowed to self-evidence the employment by providing signed forms instead of an employment contract or payslips.[footnote 20]

Table 2: Rate card outcomes and outcome metrics (at the time of research completion)[footnote 21]

| Long-term improvement for service user | Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Wellbeing | 1st Wellbeing assessment |

| 2nd Wellbeing assessment | |

| 3rd Wellbeing assessment | |

| Wellbeing improvement - 1st to 2nd assessment | |

| Wellbeing improvement - 1st to 3rd assessment | |

| Managing Money | Financial resilience outcomes |

| Emotional & Mental Health; Drug & Alcohol Misuse | Accessing services |

| Mental health sustained engagement with services | |

| Drugs/ alcohol sustained engagement with services | |

| Accommodation | Prevention / relief / entry into suitable accommodation |

| 3 months accommodation outcomes | |

| 6 months accommodation outcomes | |

| 12 months accommodation outcomes | |

| 18 months accommodation outcomes | |

| Education, Training & Employment (ETE) | Entry into education and employment |

| Part completion of Ofqual approved qualification | |

| Completion of full Ofqual approved qualification | |

| Entry into employment | |

| 6.5 weeks equivalent employment F/T | |

| 13 weeks equivalent employment F/T | |

| 26 weeks equivalent employment F/T | |

| Entry into volunteering | |

| 6 weeks volunteering | |

| Prevention of Domestic Abuse | Reduction in risk of domestic abuse |

| Accessing rights to legal protection | |

| Empowering and promoting independence |

Source: Adapted from KBOP social prime internal document

The rate card was designed in two phases. An initial rate card was developed prior to the SIB launch in 2019 and used until September 2020. Interview participants explained that the initial rate card was developed by drawing on the experience of previous housing-related social impact bonds, such as projects supported by the Fair Chance Fund.[footnote 22]

The outcomes contract allows for adaptions to the rate card. The underlying rationale was - according to the investment fund manager - a lack of data to build an assured rate card. This means that the rate card can be adjusted without the need for renegotiation of the contract. During the early mobilisation phase, the current rate card was developed. This adaptation happened during live running, and KBOP management showed a strong interest in ensuring the inclusiveness of the re-design process. The KBOP project director hosted ‘change panels’ with provider managers and frontline staff to get a comprehensive appreciation of the issues providers experienced with the initial rate card.

The final rate card includes the same headline outcomes as the initial rate card. However, outcomes are no longer split across short and long-term outcomes (see figure 4). Also, as mentioned previously, evidence requirements were softened, allowing for self-certification. The rationale for the changes were twofold: i) frontline staff did not perceive the short-term outcome measures as meaningfully contributing to the long-term outcomes; and ii) onerous evidence requirements created a significant administrative burden for frontline staff, and some of the requirements were intrusive to participants’ privacy.

Figure 3: Rate Card Development[footnote 23]

Source: Adapted from Kirklees Council

4.3 Contractual levers for performance management

4.3.1 Formal levers

In terms of contractual levers, it is important to differentiate between levers the council can apply in relation to the social prime and levers the social prime can apply in relation to the providers. The social outcomes contract contains a performance plan procedure, to be enacted if ongoing performance levels are not sufficient to fulfil contractual outcome requirements. The key contractual lever is that payment to the social prime is based on the amount and type of outcome achievement. The council contract manager highlighted:

If they’re not getting the providers to achieve the outcomes, they don’t get paid.

In contrast to the outcomes contract, the provider contracts (KBOP social prime -service providers) specify the levers applicable in situations of provider underperformance. The provider contracts contain provisions for remedial intervention, with different intensities in the case of under-performance:

- The provider can be asked to draft a formal performance improvement plan if there is a service failure [footnote 24] or a negative outcome assessment.[footnote 25]

- Alternatively, the social prime can withhold payments for providers’ central overhead fees, in case of the failure to achieve any of the downside case KPIs. It is important to note that the direct costs of frontline staff associated with the SIB service will still be covered.

- The social prime can terminate the contract if a provider continues to fail on the delivery of any of the downside KPIs for more than three months after the agreement on a performance improvement plan.

As discussed in the broader SIB literature, it is the investor and not the provider that principally carries the financial risk of under-performance. This is unlike more conventional payment-by-results arrangements. In the KBOP SIB, the social prime shields the providers from financial risk. It is the social prime that will default on re-payment of working capital to the investor if outcomes are not achieved. This was also stressed by the KBOP project director:

The whole point is that we take the risk. It should never be that partners feel that they have the pressure of individual risk in terms of delivery or financially, which creates the opportunity for innovation.

However, the contractual levers illustrate that providers still carry implementation risk alongside the social prime. Providers reported that these levers - specifically the right to withhold payments – had been a major concern when entering the SIB partnership:

I think the main kind of concerns that we had organisationally were around the penalties that we might incur, and kind of the stringent nature of the monitoring and whether that was going to lead to financial loss for the organisation based on the performance management element of the contract… and the fact that the overheads could be withheld if we weren’t performing at a certain level. And I think a lot of that was because we didn’t know necessarily what our key performance indicators were going to be or how likely it was that we were going to be able to achieve those. We don’t have any other contracts where financial penalties are issued for potential underperformance.[footnote 26]

The next section explores the extent to which the social prime used the contractual levers in practice.

4.3.2 Application in practice

Findings suggest that the relationship between the KBOP social prime and the providers was based on ‘relational norms’ rather than on the use of formal contractual mechanisms. The KBOP project director referred to these (i.e. the formal contractual remedies) as ‘pinch points’ which exist as a framework that would only be instigated if something “has gone seriously wrong”. Similarly, the investment fund director noted that, even in cases where providers underperform, KBOP would not “automatically point to the contract”. Performance issues have been addressed in a flexible way through (what the KBOP team refer to as) ‘informal action plans’ which sit as a preliminary stage to a formal action plan.

The Chair of the KBOP board described the potential procedure as such:

If they’re not achieving their targets, we will require them to come up with some sort of performance improvement plan, that can become a formal performance improvement plan. If they fail to achieve an improvement in their performance on the back of that, then we might take volumes away from them, we might move volumes between different service providers, we might review the resources that they get, and ultimately, we might remove them from the service altogether.

In practice, the investment fund manager describes a relational approach in dealing with under-performance. To August 2022 (when fieldwork was conducted), the KBOP social prime had only issued two formal performance improvement plans; one to a provider with whom the contract was eventually terminated based on mutual agreement. However, according to the KBOP leadership, prior to applying a formal action plan, KBOP attempted to resolve performance issues with the provider on an informal basis. KBOP management only considers the use of formal contractual measures as the last resort. The KBOP project director explained:

You should never get to that point where a provider isn’t able to meet their KPIs because you should be working with them, you should be looking at what their model is, where it could be improved, collaborating to problem solve and overcome any challenges identified, always looking at how you can support them […].’ Contractual clauses for performance improvement signal to providers how seriously outcomes achievement is taken.[footnote 27]

The KBOP leadership emphasised that, in principle, their approach to performance management is characterised by flexibility, trust and collaboration, rather than formal contractual performance management processes.

4.4 The outcomes contract as an emergent example of a formal relational contract

A key theme emerging from interviews across all interviewees is the importance of relationships of trust beyond formal contract terms. The Investment Fund Director explained:

The contract gives us […] a framework to work within, but actually, we’re not going to […] point to it every week. This less formal approach only works if you have really good relationships. […] I think it needs to be both parties going in on the understanding that the most important bit to this is the relationship and the contracts provide a framework for how that works

Understanding the KBOP social outcomes contract as a “framework” to enable “relationships” aligns with the notions of formal relational contracts. Formal relational contracts have been advocated as a contractual model for complex private sector contracting, such as supply chains (Frydliner et al. 2019). In contrast to ‘traditional’ transactional contracts, formal relational contracts are designed with the intention of aligning interests across parties, and creating a partnership culture which fosters a “vested interest in each other’s success” (Frydlinger et al. 2019). Formal relational contract design “recognise[s] that a higher level of trust between the partners should help to make sure partnerships run as intended”. Thus, these contracts often make “the building and maintenance of trust explicit” (Ball and Gibson 2022, p. 9). In this vein, the KBOP social outcomes contract requires the parties to “develop a close working relationship […] on all appropriate levels, based on openness and trust […]’ (KBOP social outcomes contract, Section 2).

However, the evaluation of the KBOP SIB suggests that, here, relational practice incorporates a blend of formal structures (i.e. a governance framework and a performance management system) and informal relational practice (e.g. collaborative leadership). The KBOP service manager reflected:

I think the way the [social outcomes] contract was introduced and launched is very different to how it looks now. The language, the operations manual, the rate card has changed significantly, so the experience of what it was like in that initial start-up phase is very different to how it feels now.

Findings suggest that the outcomes contract offers a malleable space within which stakeholders can build relationships and develop a collaborative environment to address complex challenges of public service delivery. In the following, the report explores how stakeholders shaped and expanded this contractual space through practice.

5. The SIB’s governance

Governance refers to all mechanisms ensuring the overall direction, control and accountability of the organisation (Cornforth & Chambers 2010). In addition to its strategic and control functions, governance is about managing relationships (Zahra & Pearce, 1989). SIBs often involve governance and oversight structures to coordinate the actions of diverse actors, ensure alignment over the course of the programme, course correct where needed, and for performance management (Burand, 2019). Hence, governance provides an important lens to analyse how the different stakeholder interests are reconciled or prioritised in a SIB and thus shaping frontline staff practice. This section investigates the structural and process characteristics of the KBOP SIB governance. A full discussion of the governance arrangements is provided in Annex C2

5.1 Formal governance structures

With the transition to the KBOP SIB model, the governance of the service was re-designed and significantly expanded. To convene the different stakeholders a series of new meeting forums have been created (see table 3). These forums either serve strategic purposes – such as the KBOP board meeting and the council meeting – or operational purposes. The KBOP social prime, an entity which has been specifically created to manage the contracts and relationships between the different SIB stakeholders, is a central facilitator to these forums. While the social outcomes contract outlines some governance structures and associated reporting obligations, governance arrangements have evolved over the course of the project and the redesign of the governance arrangements is largely left to the discretion of the KBOP project director.

Table 3: Governance structure of the KBOP partnership[footnote 28]

Strategic Meetings

| Meeting description | Key function | Members | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| KBOP board | Ensuring compliance towards social investors Subject: investment management agreement |

KBOP Chair, director of social investment fund, investment director of social investment fund, KBOP project director | Monthly |

| Council meeting | Ensuring compliance towards the commissioner (council) Subject: social outcomes contract |

Investment director of social investment fund, council contract managers, KBOP project director, KBOP service manager, KBOP data and operations analyst, LCF project officer | Monthly |

Operational Meetings

| Meeting description | Key function | Members | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual provider performance review | Ensuring compliance towards the social prime (KBOP) & capacity-building Subject: individual bi-lateral provider contracts |

KBOP service manager, KBOP data & operations analyst, provider service manager | Monthly |

| Individual provider performance review (senior team) | Ensuring compliance towards the social prime (KBOP) Subject: individual bi-lateral provider contracts |

KBOP project director, senior provider service manager | Quarterly |

| Collective provider performance review | Ensuring compliance towards the social prime (KBOP) Subject: all provider contracts |

KBOP project director, KBOP data & operations analyst, most senior provider leads | Quarterly |

| Operational change management | Provider empowerment: advancing service delivery Provider collaboration: facilitating social interaction and sharing of best practice |

KBOP project director, KBOP service manager, KBOP data & operations analyst, provider service managers, provider team leaders | Monthly |

| Personalisation working group | Provider empowerment advancing person-led service delivery | KBOP project director, KBOP service manager, KBOP data & operations analyst, mix of provider staff (personalisation champions) | Monthly |

| Co-production forum | Integration of people with lived experience in service design | KBOP service manager, KBOP engagement coordinator, people with lived experience from Kirklees services | Monthly |

5.2 Governance process: collaborative leadership

A key aspiration of the KBOP SIB was to foster better collaboration across the delivery partners by dedicating a particular resource, namely the KBOP social prime, to network management. This section examines the different roles practised by the KBOP operational management (i.e. the project director and service manager) to lead the partnership, using a collaborative leadership framework from the academic literature (Ansell et al., 2012).

The framework distinguishes three collaborative leadership roles: the steward, the mediator and the catalyst. The KBOP operational management applies components from all three leadership roles. These roles are not clear-cut, and so the same process might fulfil multiple functions.

5.2.1 The stewardship role

A steward is ‘someone who facilitates the collaborative process by establishing and protecting the integrity of the collaborative process itself’ (Ansell et al., 2012, p.6). The role of a steward (distinct to the function of market stewardship, outlined above) involves lending reputation and social capital to convene the process. The professional background of the KBOP project director and service manager in frontline management in the same policy field as the KBOP SIB, combined with their previous SIB delivery experience and their knowledge of the local commissioning context, were central to unlocking legitimacy from the delivery organisations. The interim project manager, in contrast, did not possess these reputational attributes and thus struggled to gain legitimacy.[footnote 29] The interim manager was less familiar with the local context. Moreover, interviewees indicated that in the early stages of mobilisation, leadership was associated with a narrow performance focus. This was positioned in contrast to the current KBOP management team’s focus on service users and asset-based practices.

The current project director’s social capital is understood as critical to develop and advance the KBOP SIB partnership. Because of their professional background, the project director was aware of the issues VCSE organisations were encountering in public service delivery and understood the likely challenges in implementing change using only pre-existing governance processes. In addition, the project director’s own SIB management experience, and access to the peer network for SIB project managers facilitated by the investment fund manager, allowed the project director to transfer organisational learning. The project director highlighted the importance of social capital:

At KBOP we’re working with charities and third sector organisations so it’s important to me that I maintain my networks because that enables me to have the balance of still having practical knowledge of the sector and expertise leading on behalf of the investor. I think the strength of KBOP is that we as a team have practical experience of how it works in charities and public organisations, how their structures and processes operate and how their funding mechanisms function. We have experienced the frustrations they might have in terms of the rigidity around organisational governance and contract specifications and that helps me to balance and adapt how I co-design or mobilise changes and implement our approach so it meets their requirements.

Further, the role of a steward involves ensuring the inclusiveness and transparency of the governance process. The project director described a structured approach to ensure inclusiveness by creating various meeting forums with representation from different organisational levels (see section 5.1), which are expected to serve as ‘collaborative problem-solving’ spaces and create a sense of shared ownership. While the governance structure is inclusive in the sense that providers are also involved in the strategic meetings, i.e. the KBOP board meeting and the council meeting, it is questionable to which extent these meetings offer a genuine space for providers to influence the decision-making process, as providers only attend on rotation on a bi-annual basis and only participate in a reporting function in the first part of the meeting. Findings from interviews create a mixed picture: while some provider interviewees experienced the meetings as an opportunity to have constructive discussion around operational challenges, others considered it very much a “questions & answers sort of thing”, indicating a superficial dialogue between stakeholders.[footnote 30] However, it is important to note that there are other forums, such as the operational change management forums, which offer a feedback venue for providers.

The project director stressed the practice of open communication from KBOP management with the providers:

Although there is a very clear contract management process in place… where there’s very clear accountability and reporting and governance, it is all done in a very open, honest and collaborative way. So, it’s very much “no surprises” that we play under. So, because there is such open communication, and such strong relationships, and contact with all of our partners, it should never be that anything happens which is unexpected for them or for us.

Findings from provider interviews generally uphold this description of openness. However, one participant indicated a missing feedback loop, meaning that the KBOP management does not consistently communicate how providers’ views have been incorporated into strategic management decisions. Another participant indicated that KBOP management informs providers at a late stage about planned operational changes.

Finally, the role of a steward involves managing the identity of the collaboration. The introduction of a person-led strengths-based approach articulates a guiding set of values that underpin support and to which all stakeholders could relate. In addition, the project director used the meetings to direct attention to the ‘small wins’. Acknowledging successes allowed providers to realise the link between their organisational progress and the wider purpose of the social outcomes contract.

5.2.2 The mediator role

A mediator ‘helps to arbitrate and nurture relationships between stakeholders’ (Ansell et al., 2012, p. 6). The KBOP operational management acts as a crucial interlocutor and mediator in governing the collaboration across all stakeholder groups (council, fund manager, and service providers). In relation to the board and the council, the KBOP management team advocates for the concerns of the providers. For instance, they have sought to secure the support of the council in reducing systemic barriers such as addressing the shortage of subsidised housing. Providers experienced the KBOP project director and service manager as proactive and reliable, thus acting as an advocate for their concerns with the council and the investment fund managers. A service manager remarks:[footnote 31]

When we talk collectively as an operational team or as just as a strategic group, we’re all encouraged to provide that feedback, and we’re all encouraged to come up with ideas and share best practice. [KBOP project director] and the team will go away and influence what they need to in order to enable us to do what we’re suggesting.

KBOP operational management is responsible for developing a constructive collaboration across the provider partners. Our research identifies two key processes through which this is developed: the structural framework for collaboration and the process of ‘inspirational motivation’.

The structural framework entails creating a venue for the social interaction of providers to facilitate trust-building and operational co-operation. As outlined in table 3 the formal governance structure of KBOP includes various provider group meetings, involving stakeholders from different organisational levels. The process of ‘inspirational motivation’ involves communicating a stimulating vision and raising awareness on the importance of organisational values and outcomes (van Wart 2003). The following statements illustrate deliberate use of ‘inspirational motivation’ by the KBOP project director:

My vision for KBOP is around the complete collaboration. All of us are working towards the shared goal of enabling the individuals we work with to overcome current challenges and achieve anything they want to.

We tried to make sure that we had the shared vision in terms of what we were doing, why we were doing it and how we were doing it after identifying that there was a real disparity across different teams in their understanding of outcomes contracts. We developed an operating framework ensuring everybody understood the ambitions for the programme, the operating models within it and our social purpose.

KBOP’s vision is to enable the service participants to live up to their individual aspirations. While service providers could easily relate to this vision, KBOP management needed to secure buy-in for the pre-defined service outcomes and their evidence requirements. As such the collaborative re-design of the rate card helped to build ownership across providers. The asset-based approach is a fulcrum and articulates a shared set of values, and thus created a motivation, in particular across frontline staff, to support the delivery of the outcomes contract.

5.2.3 The catalyst role

A third distinct leadership role exercised by the KBOP operational management is that of a catalyst. The catalyst is ‘someone who helps stakeholders to identify and realise value-creating opportunities’ (Ansell et al., 2012, p. 6). KBOP management use meetings with providers to jointly generate new ideas to improve service management and provision. Securing financial resources from the KBOP board, providing technical implementation support and building relevant external partnerships, are further measures taken by KBOP management to support providers’ service development ambitions.

KBOP management proactively stimulates and encourages providers to re-frame their delivery approach. For example, providers have been stretched to consider the inclusion of education, training and employment (ETE) outcomes and the compatibility of person-led support provision with an outcomes-based contract. This balance of encouragement and challenge is reflected in the following statement from the KBOP project director:

It’s very much working with each partner at their pace, understanding what they want to achieve and how we can get them there, while at the same time improving quality and impact or questioning as appropriate. Part of our role is gently challenging the way that people think, services or how systems operate to support ambitions for growth. We have conversations with them when we identify opportunities, ‘you’re so strong in this area. Do you think this is an area where you would like to do more?’

While provider interview subjects frequently described the social prime’s operational leadership as ‘supportive’ and valued the opportunity for organisational growth, the process does not always grant providers full autonomy. At times KBOP management could be described as quite prescriptive in driving change in organisational practice. Hence, in acting as a catalyst, KBOP management ensures that provider development ultimately benefits the partnership.

5.3 Governance process: control versus empowerment

To analyse governance in cross-sector public service delivery, the academic literature frequently applies agency and stewardship theory (e.g. Van Puyvelde et al., 2012; Van Slyke, 2007). Agency theory assumes goal divergence on the part of the contracted agent and stresses the use of control-oriented processes. In contrast, stewardship theory presumes convergence due to shared collective interests with the contracted steward and emphasises the importance of empowerment-oriented processes (Van Slyke, 2007). This section examines to which extent the KBOP management uses control-oriented processes versus empowerment-oriented processes, or a complementary use of both processes, in the SIB governance.

The KBOP contract management features a strong monitoring practice reflected in performance review meetings and providers’ reporting obligations see section 6.2.2. However, the description of these meetings by interviewees also revealed more of a partnership approach, where the interaction was based on trust, rather than a transactional principal-agent dynamic. Providers felt that they could have honest conversations with the social prime’s operational management addressing concerns and areas of underperformance. They described the meetings as ‘informal’ and highlighted a ‘willingness to engage in dialogue’ by KBOP management. Ultimately, the social prime did not seem to use sanctions, but a supportive, conversational approach to improve organisational performance. A service manager explained:[footnote 32]

I don’t feel that I go into a meeting dreading it. I don’t feel like come out of it deflated, where we have had issues underperforming. Where we’ve struggled with certain KPIs, KBOP was very supportive around that.

Empowerment-oriented governance practice is identified in some of the interview data. The project director considers the service providers as the ‘core’ of KBOP partnership explaining:

What fundamentally underpins the management approach within KBOP is that relationship, collaboration and trust is very much ‘we are a partnership’. We may be… the contract holders within this, but KBOP is nothing without our partners….

The delivery organisations described the social prime’s managerial behaviour as ‘listening’ and ‘being accessible’. This behaviour supported the trust-building between providers and KBOP management. KBOP management practised a bottom-up and collaborative approach to the re-design of the rate card, by consulting frontline and managerial provider staff over an extended timeframe. The participatory nature of the process was also acknowledged by the providers:

There is very much a willingness to work together, to listen to the experience from the frontline, and from the first line managers as to what actually is the real experience out there.[footnote 33]

Alongside this, KBOP management was seen to create possibilities for providers to influence strategic decision-making: KBOP management transferred responsibility to providers by supporting their ambitions for organisational growth.

However, it remains unclear to what extent the partnership governance features genuine power-sharing between KBOP management and the providers. Conceptually, we would expect a partnership among equals to be detected via two governance processes – consensual decision-making on issues concerning the whole partnership and autonomous decision-making for providers on issues concerning their individual organisation. While findings indicate that providers’ concerns do inform decision-making, it is important to note that there is a power imbalance between the providers and the social prime as the contractor. At times there is a perception that the social prime might prioritise its interest to improve the SIB service whilst overlooking providers’ wider organisational imperatives. For example, this tension was reflected in an instance when a provider was required to re-structure its service management:[footnote 34]

I think one of the things that we’re still working on is how much control we have over our own service delivery. We have had to make some immense changes. We are merging the housing support delivery and the learning delivery teams, but that is purely for the benefit of the KBOP contract. It’s something that KBOP contract managers started and the board itself have pushed us very firmly in the direction of doing. It really just benefits KBOP, but actually it doesn’t necessarily benefit other things that we do, and it’s had an impact right across the organisation…

In terms of providers’ operational decision-making autonomy, the KBOP operational management team are understood to exercise a far more hands-on contract management approach than the council in the preceding fee-for-service contract. A senior operational manager noticed:[footnote 35]

And there are daily conversations and daily communications from the KBOP hub, to those teams who are working on the ground around performance, around data, around ways of working, new initiatives, policy implementation. It’s a very hands-on form of management and that brings its own challenges to us as organisations.

Organisational size and contractual performance emerged as potential moderators which influence providers’ ability to navigate the interactions with the social prime’s operational management. The proactive intervention by the social prime in providers’ individual operational management is paradoxical to the implementation autonomy granted by the contract and the developmental culture promoted by KBOP management. Overall, KBOP management apply a blended approach borrowing from both control and empowerment-oriented processes.[footnote 36]

6. The causal mechanisms of the KBOP SIB: four hypotheses

This section seeks to explore whether the four hypotheses developed in the first interim evaluation report lead to a shift in contract management and frontline delivery. The four hypotheses underpinning the SIB mechanism are an enhanced practice of:

-

market stewardship

-

performance management

-

collaboration across providers

-

flexibility in implementation.

The analysis considers positive and negative changes, compared to the preceding fee-for-service contract. The first interim evaluation report entails a detailed analysis of the implications of the fee-for-service contract on management and delivery.[footnote 37]

The analysis of the individual mechanisms concludes with a figure summarising the two commissioning arrangements. This includes a description of the issues associated with the fee-for-service model and supporting evidence; and a description of the facilitators (i.e. the mechanisms) in the SIB model, supporting evidence and drawbacks. Importantly, all findings need to be validated in a further, final research wave and so these findings are preliminary.

6.1 Enhanced practice of market stewardship

Public service commissioners are expected to create the conditions for an effective market of providers. Following the introduction of the outcomes contract, a marked shift in market stewardship appears to have taken place. The ‘rules of the game’ have been reoriented by the commissioner to place greater emphasis on person-centredness and long-term outcomes. The availability of the Life Chances Fund top-up funding and the involvement of the fund manager is understood to have enabled a more substantial and dedicated team to augment the practice of market stewardship. As a social prime, KBOP takes on parts of the market management work: developing market intelligence and service insights and guiding the alliance of delivery organisations with a range of formal market management interventions (managed provider exit; market share shift) and developmental support (provider training and development around asset-based working).

Local government staff tend to use the term “market sustainability” to refer to this process of managing provider entry, service quality, access, suitable options for service users and (in some cases) provider exit (personal communication between research team and Kirklees Council staff). The task of market stewardship can broadly be summarised under two headings (Broadhurst & Landau, 2017):

-

Market intelligence and service insights – activities that seek to understand the needs, objectives and enablers of successful delivery and provide data on the market, such as provider stability, relative performance, and the ‘health’ of the provider market

-

Market influencing – the activities that influence the current and future range of care and support available, or what is sometimes referred to as the “rules of the game” (Gash et al., 2013, p. 6). This refers not only to local care and support provision, but also to commissioning and social work practices including brokerage, funding, accountability mechanisms and communication between the local authority, partner agencies and individuals in the wider market (Broadhurst & Landau, 2017).

These two concepts of ‘market intelligence’ and ‘market influencing’ are used to structure themes that emerged during participant interviews and observation, particularly to describe the key shifts that have occurred.

6.1.1 Market intelligence and service insights

Following the introduction of the outcomes contract, the work of gathering service intelligence and influencing the provider market is now shared between the council and KBOP social prime.

There are both technical and relational elements of the market and service intelligence function that have shifted since 2019. Most obviously, in terms of technical infrastructure, the CDPSoft system is used by the council for monitoring and validating outcome payments; by KBOP for managing referrals of potential programme participants and underpinning performance management data on relative provider performance; and by providers themselves for collecting and retaining key case management information.[footnote 38]

The establishment of CDPSoft and the KBOP referral hub are understood by both council staff and KBOP management team to have substantively improved the quality of insights available. The council contract team use CDPSoft regularly and flexibly, not just for the validation and administration of outcome achievements, but also to investigate and understand other facets of service quality. This software effectively makes visible (in stark contrast to the previous fee-for-service contract) granular service performance data on a variety of indicators that are understood as quality markers by the council. Indicators used by the council to understand the service include:

- time taken between initial referral and support commencing with a named provider

- waiting lists

- characteristics of KBOP participants, including an understanding of those who have been declined access to the service

- duration and frequency of support

- outcomes achievement

Council contract managers confidently use query functions to produce specific reports in response to requests for insights – for example, investigating all participants who have been referred to the KBOP service multiple times.

The KBOP project director describes the benefits of this intelligence:

[We are] using our evidence and data to strengthen what we already know on an operational basis, therefore influencing the commissioning and the systems change.

Speaking with reference to one delivery organisation:

they can look at the trends coming through in terms of the women they’re working with, to invest in long-term outcomes for those individuals to prevent victimisation. We can gather the evidence, tracking the impact and tracking the benefits of working with women on a longer-term basis.

Under the SIB commissioning arrangement, the KBOP social prime takes on the role of referral hub and in this guise also functions as an important conduit, both generating and responding to service intelligence. The KBOP service manager explains:

We’re also monitoring capacity with all of the delivery partners to make sure that people can get the support that they need as quickly as possible…We constantly look at caseloads and how many new starts have commenced with each of the delivery partners, so that we can send the referral to the service that they’ll get help from the quickest.

When reflecting on the differences between the KBOP SIB arrangements and the preceding bilateral fee-for-service contracts, the council team commented on the considerable resource and ‘infrastructure’ that now goes in to supporting the intelligence and market management function. This features a broader scope than the previous council contract management. The senior council contract manager notes:

I think if we had that many staff, we would probably have been able to manage the relationship [i.e. the service provider contracts]. The problem …was that we had nowhere near that resource to be able to focus that much on performance and quality management at all. So, it’s part of that infrastructure question as well, isn’t it? … Well, does that infrastructure add value?

Providers also report that intelligence is used proactively by the social prime to improve the match between service participants and their respective providers. In terms of service selection, the KBOP service does not explicitly offer service participants a ‘choice’ of provider. Staff members who facilitate the motivational interview that functions as a referral assessment note that they accommodate participant preferences to work with/avoid specific delivery teams. The referral conversation may also reveal information that is used to match participants to provider specialisms. This is particularly the case for people who are overcoming domestic abuse and dual diagnosis.

The Chair of the KBOP board also acknowledges that the service delivery network may benefit from the development of further specialism:

I’d really like to see, as we go on and mature, an understanding of the different strengths of the different organisations so that when someone comes in and we triage them, they are directed to the organisation best placed to provide them with a response to their needs.