Low cost home ownership schemes (HTML)

Published 3 July 2017

This research was first published in July 2017 in PDF format by the Social Mobility Commission.

This HTML version was published in March 2022 to provide the content in a more accessible format.

Content has not been changed or updated from the original publication, except:

- spelling mistakes have been corrected

- some charts have been replaced by tables to make the data more accessible

Authors

Dr Bert Provan

Alice Belotti

Laura Lane

Prof Anne Power

London School of Economics

Executive Summary

International context of government schemes to promote home ownership

Low Cost Home Ownership (LCHO) schemes are common in many countries. OECD evidence suggests this is based on the idea that they promote wealth accumulation, better outcomes for children, and higher levels of social capital in neighbourhoods, although none of these is unambiguously evidenced. More important is that it is often seen as a universal household aspiration.

Schemes come in many different forms. These include subsidising the construction of “affordable” homes to buy; or reducing the cost of buying for individual households including through lower deposits, subsidised savings schemes, government guarantees, grants to reduce the price, and the sale of public housing at a discount (“Right to Buy” in the UK)

UK Low Cost Home Ownership (LCHO) schemes

In the UK promoting ownership for first-time buyers (FTBs) has been a cross party policy since the 1990s, and is a current Government priority.

The 2016 Housing White Paper continues this commitment to extending home ownership to more first-time buyers through Low Cost Home Ownership (LCHO) schemes, as well as extending the opportunities for social tenants to buy their own homes (Right to Buy schemes). This is alongside the wider focus of the White Paper on increasing the overall supply of owner occupied housing.

Official figures relating to LCHO up to 2015 indicate that 1.8 million properties were moved into ownership through Right to Buy. Between 2003-4 and 2014-5, 223k affordable home ownership units have been provided, or around 13% of all housing completions in that period. In addition, 300k households were assisted through subsidies to first-time buyers, including over 80k FTBs who have used the Help to Buy Equity Loan scheme since 2013[footnote 1].

An independent report commissioned by DCLG (Finlay et al 2016) estimated that Help to Buy Equity Loans had generated 43% additional new homes over and above what would have been built in the absence of the policy, equivalent to contributing 14% to total new build output to June 2015.

Since 2011-12 the number of social rented properties being completed has fallen sharply, though the number of new “affordable rent” homes (more expensive than social rents) has increased.

Reviews and evaluations of the impact of LCHO schemes

LCHO schemes have been subject to parliamentary scrutiny as well as extensive research and evaluation. Parliamentary scrutiny has frequently focused on whether the schemes stimulate new housing supply and increase the rate of home ownership, as opposed to working to inflating prices in a housing market with insufficient supply.

Other literature has reviewed whether LCHO schemes work by bringing new first-time buyers into ownership, or instead allow them to become owners at a younger age. Bottazzi et al (2012) suggest the latter is the case from a review of two birth cohorts.

Australia has had similar policies since 1918. Evidence from that country suggests that their policies have inflated demand for housing, but done little to increase supply, and consequently made affordability worse. Boosts to first-time buyers in periods of market uncertainty were seen to be followed by lowered demand in subsequent periods.

Who benefits from English LCHO schemes?

Finlay et al (2016) found that the average (mean) gross household income at the time of the Help to Buy Equity Loan purchase was £47,050, and the median income was £41,323. This compares to a mean gross household income of owner-occupiers with a mortgage in England who were first-time buyers (and resident for less than 5 years) of £47,528, and a median of £39,834. This indicates that these schemes are not expanding social mobility by opening up home ownership to new groups of lower income households. Rather they are being used by households who would most likely buy anyway.

In line with this, Government data on recent LCHO schemes shows that their impact on social mobility is likely to be small. Although the median household income of working families is £507 a week (equivalent to around £30k gross annually), 80% of beneficiaries of LCHO schemes had incomes above £30k pa.

Similarly, 48% of first-time buyers benefiting from Help to Buy Equity Loans paid over £200k for their home. This is not near being affordable for a person at median earnings, in the light of current price to income ratios.

Some other first-time buyers receive non-government assistance to get on the housing ladder, but not in a way that improves overall social mobility either. This is evident from another recent Social Mobility Commission report (Udagawa and Sanderson 2017) which indicated that parental assistance (the “bank of mum and dad”) has helped about a third of first-time buyers into ownership, with a further 10% benefiting from inheritance money.

Discussion and options for improving low income households’ access to home ownership

The recent Redfern report (Redfern 2016) found that currently reducing levels of home ownership (and hence barriers to extending home ownership to low income and other groups) were linked to:

- reduced overall housing affordability for purchasers

- problems with access to finance due to deposit and other requirements, and

- the wider problem of incomes not keeping pace with prices.

The recent (2016) Housing White Paper addressed the issue of supply by stating “The housing market in this country is broken, and the cause is very simple: for too long, we haven’t built enough homes”, and setting out a series of policy proposals to increase supply.

Unless and until these proposed measures succeed in increasing supply and reducing prices, the current LCHO schemes will continue to be constrained by the barriers outlined by Redfern and others. They are unlikely to increase ownership amongst low (near median) income groups as the gap between their incomes and house prices is too great.

Shared ownership provides a more affordable route to home ownership, and is taken up by households with income very near median income, although the overall cost of shared ownership can be high and it can be difficult to “staircase” up to buying further shares of the property when house price rises are outstripping wage rises. Nevertheless it appears to provide new opportunities for lower income groups to become (part) owners

Responsible lending practices require that home ownership is only extended to households who can afford it, particularly in light of the global financial crisis. Nevertheless there are options to target LCHO subsidies more effectively on groups who have the potential to own but may need financial and other support to become homeowners. This would include providing support to targeted sectors amongst the more general pool of first-time buyers, and in particular those how have incomes below the current levels of first-time buyers, but nearer median income levels; and groups who may not have previous knowledge and experience of navigating house purchase and the responsibilities and opportunities of ownership.

Some specific targeting mechanisms are suggested to improve impact of LCHO schemes on social mobility, drawing on international evidence of best practice. These include targeting of financial subsidies on households with incomes up to 1.5 times median income, but at different levels for different regions; and providing much more advice and guidance to appropriate working households from groups or communities without a history of ownership to help them into ownership by managing risks and expectations.

Section 1: The international context of government schemes to promote ownership

Promoting home ownership is a common government policy in many OECD countries (Andrews and Aida 2011) and a wider range of emerging economies (IMF 2011). A summary of the most commonly cited drivers and drawbacks is provided in this report, reproduced in Annex 1. In essence the benefits and drawbacks identified in the various national policies include:

- wealth accumulation – leading to higher household savings generally and savings for retirement - although there are also drawbacks from the illiquid nature of housing wealth and risk of negative equity.

- better child outcomes – in terms of educational achievement and better behaviour - although the fact homeowners have higher incomes may also be responsible for these better child outcomes

- social capital – including more socially active and engaged citizenship behaviours - although more civically minded households may be more inclined to become home owners

- labour mobility – this is lower amongst home owners - although this lower mobility may also improve the stability and performance of homeowner’s children in schools.

Generally, many OECD countries have used the types of benefits set out above as explanations for the public policies which favour home ownership over renting. This economic rationale is also often complemented by the idea that owner occupation is the “national dream” or universal household aspiration. Counterbalancing this, OECD evidence suggests that legislating to regulate rent and provisions for tenure security implicitly impact homeownership by making renting more attractive.

Andrews and Aida also cite evidence that increasing rates of home ownership in some OECD countries is linked to demographic changes – with an increasingly elderly population being more likely to be home owners. Similarly (and not surprisingly) households with higher income and couples are more likely to be owners, while immigrant households are less likely – and around three quarters of the change in home ownership between the mid-90s and mid-2000s in the UK can be explained in changes in these demographic patterns.

More specific public policies also increase ownership rates in OECD countries, including the UK. Relaxation in mortgage down payment restrictions has a positive impact on the ability of low income or credit constrained households. On the other hand, policies such as allowing mortgage tax deductibility tend to have regressive effects (since the probability of ownership rises with income) and lead to house price inflation.

IMF (2011) also provides an overview of the extent of government intervention to promote home ownership, looking at a wider range of countries, including emerging and newly industrialised economies (ENIEs) in Asia, Latin America, and South Africa. While the panorama of the report’s analysis ranges from reference to the German Pfandbriefe (covered bond) system - which dates to 1769 and was heavily influenced by the aftermath of the Seven Years’ War - to the present day, it mainly focuses on responses to the global financial crisis of 2007-8. The report also sets out (diagram reproduced below) detailing of the types of interventions which are commonly put in place by governments, distinguishing between emerging and advanced economies:

Figure 1: IMF table of Government participation in Housing Finance

Source: IMF staff estimates.

The types of support measure shown on the x axis (A to H) are:

A. subsidies to first-time or other buyer up front B. subsidies to buyers through savings account contributions or through preferential fees C. subsidies to selected groups, low income D. provident funds early withdrawal for house purchase E. housing finance funds or government agency that provides guarantees/loans F. tax deductibility of mortgage interest G. capital gains tax deductibility H. state-owned institution majority market player greater than 50%

This table shows the high incidence in advanced economies of capital gains tax relief, tax relief on mortgage payments, subsidies for savings and fees, and loan guarantee programmes. Note that the specific measures for first time or low income/selected group buyers (A,C, highlighted) are less common, particularly in these advanced economies.

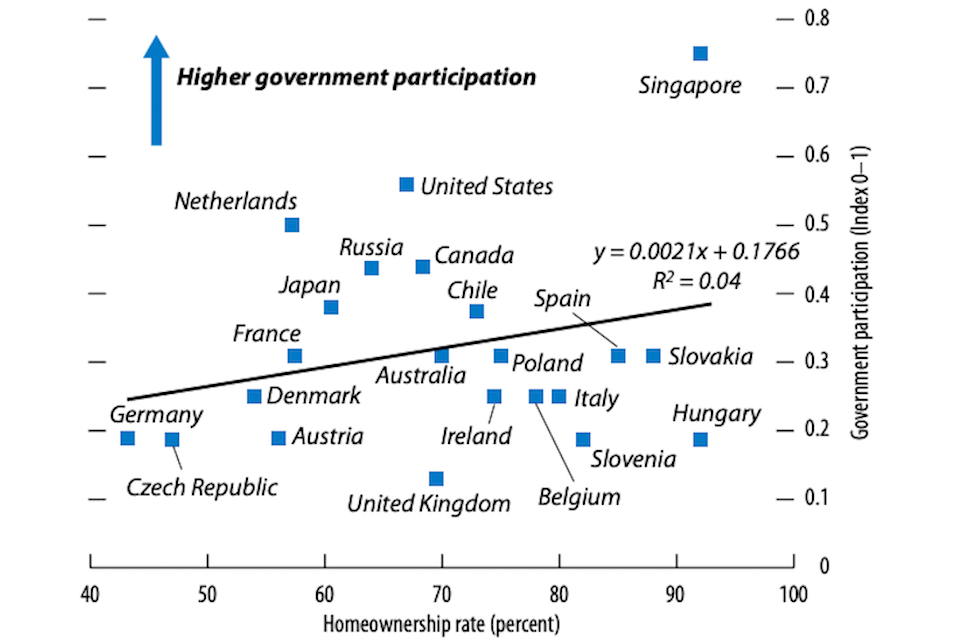

The IMF report also includes a diagram (Figure 2 below) indicating that higher rates of government participation in housing finance is associated with higher rates of home ownership, although note that the UK is rated as having a low government participation rate.

Figure 2: IMF table of homeownership rates and Government support

Sources: European Mortgage Federation; Australian Bureau of Statistics; Japan, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Statistics Bureau; Singapore, Department of Statistics; U.S. Census Bureau; and IMF staff estimates.

A similar breakdown of government intervention initiatives is provided by Lawson and Milligan 2007, who list types of home ownership strategies and some of the advanced economy countries who deploy them. This is summarised in Figure 3 below, and covers a wider range of initiatives than the IMF tables. The IMF categories are also shown using the IMF X axis labels above, to bring these two tables together. The UK column is highlighted, and note that since 2007 the UK has also included Affordable Homes supply side subsidies for construction.

This paper aims to explore the extent and impact of UK initiatives to open up homeownership to different groups of people, and in particular to lower income households – the so-called Low Cost Home Ownership or LCHO schemes. These schemes mirror the general types of initiatives internationally which have been set out above, and the overlap with the IMF/OECD information categories is summarised in Figure 4 below. Figure 4 also sets out the possible indicators of success for these different measures. Drawing on this framework, the main questions to address in the rest of this report are:

- What are the main barriers to home ownership for lower income groups in the UK? These include the inability to provide a deposit, supply of housing, and high price to income ratios.

- How far do LCHO schemes help low income groups overcome these barriers? In particular, to what extent do the policies aimed at the general category of “first-time buyers” actually enable new groups of low income households to gain access to ownership, and encourage other households from groups who are less represented (such as where there is a disabled household member, or the household is from an ethnic minority community) – as opposed to providing subsidies to FTBs who would almost certainly enter ownership at some point anyway, albeit later?

- What steps might be taken (informed by experience in other countries) to improve the effectiveness of these schemes in promoting social mobility by better targeting of the LCHO schemes?

In considering these questions it is important to reiterate the key distinction between on the one hand the general effects of LCHO schemes in helping first-time buyers in general, and on the other hand helping specifically lower income and less represented groups of first-time buyers who are the target of social mobility policies. The more general group may have incomes well above median income, and may well be likely to buy in due course, but be helped to buy sooner by LCHO schemes – but would probably have become owners at some point without any help from a government scheme. The focus of this paper is on the second group, who would be unlikely to buy without the assistance of government funded LCHO schemes. This is a much more specific question than the general effect of the LCHO schemes on stimulating ownership, stimulating house building, stimulating the economy, or even just assisting a wide range of first-time buyers.

Figure 3: Types of home ownership strategies by category and country

| Policy area | Austria | Belgium | Canada | Denmark | France | Germany | Ireland | Netherlands | NZ | Switzerland | UK | USA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supply side subsidies for production | yes | yes | yes | |||||||||

| Consumer education, particularly for marginal groups | yes | yes | yes | |||||||||

| Mortgage market regulation, facilitation, insurance and security | yes | yes | yes | yes | ||||||||

| Demand-side subsidies for (low-income) purchase | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | |||||

| Access to individual pension savings | yes | |||||||||||

| Contract savings schemes | yes | yes | yes | yes | ||||||||

| Fiscal incentives and subsidies for ownership | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | |||||||

| Large-scale sale/conversion of public/private rental housing to ownership | yes | yes | yes | yes | ||||||||

| Promotion of shared equity tenure | yes | yes | yes | yes | ||||||||

| Regional strategies to address uneven markets | yes | yes | yes | yes |

Source: Lawson and Milligan, 2007

Figure 4: Types of low cost home ownership programmes

| Approach | Overall main objective | UK aspects including social mobility | Main evaluation indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supply side subsidies for production – to build more homes | Increase overall supply through supply side (capital) subsidies restricted to specific type of low cost home, and in some cases restrictions on who can buy these homes, and subsequent sales. | Affordable Home Ownership (and Guarantee) Programmes, using HCA/GLC capital, and S106 schemes. Limited focus on mobility groups, as eligibility/scheme focus often loosely drawn. | A main indicator of success is additional homes built, rather than characteristics of beneficiaries (see, eg. evaluation of Help to Buy Equity Loans). Benefits can accrue to households who would become owners in due course (so no extension of social mobility) and to developers. In addition, these schemes are often used to provide economic stimulus to the wider economy, rather than simply to address housing policy objectives. |

| Consumer education, particularly for marginal groups | Programmes to assist new and inexperienced owners to address financial and practical ownership issues. | Mainly provided through third sector agencies, if at all. | Can be essential for mobility in ensuring good initial financing products used, and planning to sustain ownership long-term (eg. advice and guidance on repairs, insurance products, financing of planned maintenance). Can be hard to monitor as multiple agencies may be involved. |

| Demand-side subsidies for (low-income) purchase, and other fiscal incentives and subsidies for ownership | Directly subsidise ownership cost. This includes price subsidies, interest rate reductions or subsidies, lower stamp duty and other taxes, insurances or costs of obtaining and maintaining ownership. | Help to Buy equity loan, and other Homebuy schemes. Limited focus on mobility groups, as eligibility focus often loosely drawn. | Main focus is often overall home ownership rate, not characteristics of beneficiaries, and “reach” of subsidies and incentives can be far above resources of the poorest or most disadvantaged groups. So “success” may hide limited impact on social mobility, as with supply side subsidies. |

| Mortgage market and savings regulation, facilitation, insurance and security | Subsidise financing costs through lower interest, topping up savings, mortgage underwriting guarantees against losses, and similar incentives to reduce cost and risk of borrowing. | Help to Buy ISA, NewBuy guarantee, and others. Very limited focus on mobility groups, as eligibility focus often loosely drawn. | Essentially another demand side subsidy with similar issues of providing support for middle income households as well as risks of price inflation. Additional issue is the risk associated with uncapped Government guarantees in the event of negative equity or default, leading to potential opportunity costs from covering these losses from general public expenditure. |

| Large-scale sale/conversion of public/private rental housing to ownership(also common in many East European countries) | Allowing social housing or private renting tenants to become owners, often with subsidy. | Right to Buy and Right to Acquire schemes, with large scale public subsidy. High social mobility impact, but reduces stock of social housing available for poorer households. | UK Right to Buy almost always targets low income groups. BUT results in removal of high quality social housing for more disadvantaged people, if the units are not replaced by other social housing units. The Eastern European model is not applicable to the UK, although might be applied in other currently state socialist countries such as Cuba. Serious problems can occur where the rights and responsibilities relating to the common parts and shared areas are not fully specified and regulated on transfer. |

| Promotion of shared equity tenure: this may sometimes involve both shared ownership of part of the building and special arrangements around mortgage guarantees | Allow ‘staircasing’ into ownership for those unable to afford full ownership, including subsidies for rent, reepairs, or mortgage and other costs. | Traditional housing association and more recent shared ownership schemes (including Help to Buy). Potential for high positive impact on low income social mobility. | Can often assist low income groups, depending on income cap for participation. Allows the recycling of funds back to housing associations on purchase and staircasing, for reuse to encourage more moves into ownership from social housing tenants, rather than being lost to the wider housing market as simple supply side subsidies are. |

| Regional strategies to address uneven markets | Specific programme for different regions to differentially address regional housing markets. | Schemes considered here are England wide; different schemes cover other UK nations. Not based on social mobility issues in England. | Main evaluation would be across the UK nations, comparing effectiveness of schemes. |

Section 2: Cross party Low Cost Home Ownership schemes 2005 to 2016

Policy commitments

Government action to promote home ownership, particularly for first-time buyers, is a cross party policy. Annex 2 sets out the approaches of Labour, Coalition and Conservative governments in more detail, and an overview is set out below.

Note, first, that the Right to Buy programme has been a major enabler of owner- occupation for former local authority (and to an extent housing association) tenants. Between 1980/81 and 2014/15 a total of 1,805,282 local authority flats and houses were transferred through Right to Buy, and a further 96,818 housing association sales – almost 2 million in total[footnote 2]. These sales attract large discounts, linked to how long the tenant has lived in the property, and represent a major and affordable route to home ownership for many low-income households in social housing. This report does not focus particularly on this route to home ownership, as it is a very specific type of scheme transferring ownership directly to social housing tenants, rather than being part of the wider housing market. Its impacts and influence on the wider housing market and on LCHO schemes is noted where relevant. The main focus of this report, however, is on schemes which complement RTB in the wider housing market.

A range of small scale programmes existed pre 2000, including Homebuy and the Tenant Incentive Scheme, but LCHO schemes became more prominent after 2000. Labour, in its response to the Barker report (HMT/ODPM 2005, Barker 2004), set out that:

The Government’s core objective for housing policy is both simple and fundamental: to ensure that everyone can live in a decent home, at a price they can afford, in a sustainable community. This requires Government to deliver:

- a step on the housing ladder for future generations of homeowners

- quality and choice for those who rent

- mixed, sustainable communities

In the Coalition period, the Department for Communities and Local Government published its housing strategy, Laying the Foundations, in November 2011. The stated context was 3 main perceived barriers to home ownership:

- potential home owners cannot afford mortgage finance

- lenders restrict access to mortgages to buyers with big deposits

- developers do not build enough new homes, partly because potential buyers cannot raise a mortgage

The plans outlined (DCLG 2011) set out:

We have committed nearly £4.5 billion investment in new affordable housing over the Spending Review period that ends in 2015…..

- Under the new Affordable Homes Programme….146 providers …will deliver 80,000 new homes for Affordable Rent and Affordable Home Ownership with government funding of just under £1.8 billion….We are also supporting shared ownership schemes through the Affordable Homes Programme 2011–15, where this is a local priority..

- In addition, the new FirstBuy equity loan scheme (announced in the Budget 2011) will see the Government and over 100 housebuilders together providing around £400 million to help almost 10,500 first-time buyers purchase a new build home in England with the help of an equity loan of up to 20 per cent.

Finally in the current Conservative period, there was a continuation and extension of the previous Coalition approach, set out in the 2015 Autumn Statement[footnote 3]. This presented proposals as

This Spending Review sets out a Five Point Plan for housing to:

- Deliver 400,000 affordable housing starts by 2020-21, focused on low-cost home ownership.

- Deliver the government’s manifesto commitment to extend the Right to Buy to Housing Association tenants

- Extend the Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme to 2021 and create a London Help to Buy scheme, offering a 40% equity loan in recognition of the higher housing costs in the capital. First time buyers that save in a Help to Buy: ISA will receive a 25% government bonus on top of their own savings.

Further government commitments were made in the 2016 Housing White Paper[footnote 4] which includes a commitment in the Prime Minister’s foreward to to “help households currently priced out of the market”. This is developed in the “Step 4 – Helping People Now” proposals as:

- Continuing to support people to buy their own home – through Help to Buy and Starter Homes;

- Helping households who are priced out of the market to afford a decent home that is right for them through our investment in the Affordable Homes Programme.

Low cost home ownership programme outputs

On 5th February 2003, the then Deputy Prime Minister announced the establishment of the Home Ownership Task Force as part of the Government’s Sustainable Communities plan, which reported later that year[footnote 5]. This was partly due to the perceived complexity of the previous schemes – though the review here of the subsequent frequently changing landscape of schemes suggests that the simplification and clarity objective was not really achieved in the years that followed. Nevertheless there are some key principles that run through the various subsequent iterations of support for home ownership, which draw on the analysis in part one and are highlighted below.

Home ownership schemes, as set out in the previous section, can involve initiatives to stimulate “supply side” building of “affordable” homes for sale (which is to say within a price range that a targeted group of first-time buyers might be able to buy). Alternatively, or sometimes as part of the same scheme, they can involve the “demand side” provision of subsidies or other schemes to help the targeted first-time buyers more able to obtain deposits or mortgage finance or more generally afford the regular payments (including the “shared ownership” approach which allows incremental purchase of an ownership share in a property while continuing to pay rent for the part owned by the landlord, usually a Registered Social Landlord).

Looking first at measures to boost supply, figures published by DCLG in November 2016[footnote 6] including 2015-15 actuals and 2015-16 projections, show a total of almost 223k affordable home ownership units provided since 2003-4, or around 13% of all housing completions 2003-2015[footnote 7] - see Figure 5[footnote 5] below.

Figure 5: Total new affordable home ownership unit completions 2004-05 to 15-16

| Year | Completions |

|---|---|

| 2004-05 | 14,280 |

| 2005-06 | 20,680 |

| 2006-07 | 18,430 |

| 2007-08 | 22,420 |

| 2008-09 | 22,900 |

| 2009-10 | 22,240 |

| 2010-11 | 17,010 |

| 2011-12 | 17,590 |

| 2012-13 | 17,260 |

| 2013-14 | 11,410 |

| 2014-15 | 15,970 |

| 2015-16 | 7,540 |

| Total | 207,730 |

Notes: 2015-16 includes 4,110 shared ownership units, and is provisional. Source: DCLG live table 1000, Nov 2016.

This can be seen in the context of all new homes provided under the general Affordable Housing programmes in this period, set out below in Figure 6. This shows the rapid decline in new “social rented” properties after 20011-12 and corresponding rise in (higher rent) new “affordable” rent properties. There is also a slowdown of affordable home ownership properties completed after the global financial crisis.

Figure 6: Total Affordable housing additional home completions by tenure 2004-5 to 2015-16[footnote 8]

| Tenure | 2004-05 | 2005-06 | 2006-07 | 2007-08 | 2008-09 | 2009-10 | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Rent | 21,674 | 23,633 | 24,683 | 29,643 | 31,122 | 33,491 | 39,562 | 37,677 | 17,580 | 10,924 | 9,331 | 6,798 |

| Affordable Rent | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 1,146 | 7,181 | 19,966 | 40,860 | 16,549 |

| Intermediate Rent | 1,513 | 1,675 | 1,201 | 1,109 | 1,707 | 2,562 | 4,523 | 2,055 | 1,340 | 1,294 | 1,105 | 1,697 |

| Shared Ownership | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 11,128 | 4,084 |

| Affordable Home Ownership | 14,283 | 20,687 | 18,429 | 22,424 | 22,963 | 22,244 | 17,004 | 17,468 | 16,976 | 10,940 | 3,535 | 3,486 |

| All affordable | 37,470 | 45,995 | 44,313 | 53,176 | 55,792 | 58,297 | 61,089 | 58,346 | 43,077 | 43,124 | 65,959 | 32,614 |

Figure 7 below shows additional homes to buy under affordable home ownership schemes, under a range of other specific supply side measures, including some purchase of existing homes. Figure 8 on the subsequent page shows the range of demand side schemes to assist households with the costs of purchase, deposits, and other costs.

Figure 7: Additional homes to boost affordable homeownership, by scheme, including purchase of existing homes (edited version of DCLG Table 1010)

| Scheme | 2003-04 | 2004-05 | 2005-06 | 2006-07 | 2007-08 | 2008-09 | 2009-10 | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15(P) | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affordable home ownership, by product: | 15,130 | 14,280 | 20,680 | 18,440 | 22,430 | 22,900 | 22,240 | 17,010 | 17,040 | 15,560 | 6,830 | 5,380 | 197,920 |

| Open Market HomeBuy | 2,550 | 5,140 | 7,360 | 2,510 | 2,880 | 6,220 | 5,350 | 140 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 32,150 |

| New Build HomeBuy (1) | 3,620 | 5,860 | 8,700 | 10,960 | 14,880 | 11,820 | 9,110 | 8,680 | 8,720 | 3,570 | 1,890 | 730 | 88,540 |

| HomeBuy Direct | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 5,070 | 5,720 | 1,320 | 130 | 0 | 0 | 12,240 |

| Social HomeBuy | .. | .. | .. | 50 | 160 | 100 | 80 | 110 | 40 | 20 | 20 | 40 | 620 |

| FirstBuy | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 2,990 | 7,640 | 970 | 0 | 11,600 |

| Section 106 nil grant(2) | 1,550 | 1,470 | 2,640 | 3,160 | 2,730 | 2,290 | 850 | 1,030 | 1,430 | 1,830 | 1,950 | 2,830 | 23,760 |

| Other(3) | 7,410 | 1,810 | 1,980 | 1,760 | 1,780 | 2,470 | 1,780 | 1,330 | 2,540 | 2,370 | 2,000 | 1,780 | 29,010 |

Notes: Table 1010: Additional affordable home ownership homes provided in England, by type of scheme. Updated April 2016, edited by authors.

1. New Build HomeBuy completions include Rent to HomeBuy.

2. Section 106 figures exclude S106 nil grant completions recorded in HCA and GLA IMS and PCS data.

3. Other includes Assisted Purchase Schemes and other grant funded schemes not specified above.

4. Figures shown represent our best estimate and may be subject to revisions. The figures have been rounded to the nearest 10 and therefore totals may not sum due to rounding.

R. Revised. P. Provisional. “..” not applicable.

Source: Homes and Communities Agency, Greater London Authority, local authorities, delivery partners

Figure 8: UK schemes involving subsidies to households 2005-16 (excluding supply side capital subsidies in tables above)

| Schemes | New build Homebuy | Open Market Homebuy | HomeBuy Direct | Social HomeBuy | First Buy | NewBuy Guarantee | Help to buy ISA | Help to buy Equity Loan | London Help to buy | Help to buy Mortgage Guarantee | Help to buy Shared Ownership |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | 2003- | 2003-2011 | 2009-2013 | 2006- | 2011-2014 | 2013-2015 | 2015- | 2013- | 2013- | 2013- | 2016-21 |

| Only for new properties | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Partly | |||||

| Only for social housing built or owned properties | Y | Y | Partly | ||||||||

| Price/cost subsidy | Y | Y (interest) | Y | Y | Interest on 20% | Interest on 40% | Low rent/repairs | ||||

| First time buyer focus | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| Low income or targeted group subsidies or focus | Y | Y (as RTA) | Y | Price ceiling | Price ceiling | Price ceiling | £80k (£90 London) Income cap | ||||

| Savings account or fees subsidies | 25% of saved | ||||||||||

| Government guraantees for housing finance funds | loss value | to 15% of loss | |||||||||

| Equity share element or shared ownership | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||

| Households assisted to date | 88,540 | 32,150 | 12,240 | 620 | 11,600 | 5,695 | 27,222 | 100,284 | 4,483 | 5,693 | aim of 135,000 by 2020 |

Notes: Forces Help to Buy, Older People’s shared ownership, HOLD (shared ownership for people with LLID), Forces help to buy, not included. Early pension withdrawal and MIRAS never offered, and Capital Gains nil tax always offered for owner occupiers. Sources: DCLG live tables series and statistical summary and policy documents available at December 2016.

Section 3: Literature review of impact of Low Cost Home Ownership schemes

There have been several relevant studies, and official or systematic reports on low cost home ownership schemes since 2000. One of the earliest reviews was of the 1998 Homebuy scheme by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (Jackson 2001). This was a development from the previous Do it Yourself Home Ownership (DYSO) and Tenant Incentive Scheme programmes, which aimed to identify moves to owner occupation for social tenants which enabled existing social housing to be retained and reused. There were also other previous specialist schemes like Homesteading and Improvement for Sale. Under the Homebuy programme, registered social landlords made an interest-free loan (Homebuy loan) to help a household to buy a home of their own on the open market. The funding for the Homebuy loan came from the Housing Corporation as part of its Approved Development Programme. The loan was interest free and covered 25% of the value; the householder had to finance the remaining portion. There was no time limit for this loan, but on sale the purchaser had to repay 25% of the sale price to the Housing Corporation who could then re- cycle the money. The scheme was restricted to tenants of registered social landlords, local authorities and those nominated from waiting lists (who would otherwise have priority for social housing) to buy a home of their own. This was also aimed at reducing the demand for social housing by creating vacancies in social housing stock, reducing waiting lists and re-housing those in priority need in vacated units.

This study is cited as it raises many of the issues that are pertinent to the analysis in this report as a whole. The period covered had seen only 1,318 households complete, but it already drew attention to:

- the awareness and targeting of the programme, in this case being much more focused on RSL (housing association) tenants than local authority tenants

- the extent that the householders would have purchased anyway (one in three said they would have done within three years without the programme)

- the fact that Homebuy is taken up by households whose incomes are much higher than their counterparts who buy under shared ownership schemes

- the value for money of the public investment

- the flexibility of the level of assistance in the light of regional housing and income variations

This programme had a clear cross tenure link to social housing provision, aiming to free up social stock by focusing on existing social housing tenants. It also recycled funds on sale, similar to shared ownership. As such it was much more restricted than the later schemes which were open to a much wider range of low income first-time buyers, and increasingly without any link to social housing.

Monroe (2007) undertakes a contrastingly wide ranging literature review of research on how housing policy in the UK has constructed and responded to the goal of increasing the number of people who become owner occupiers. Echoing the OECD analysis of the frequently cited policy justifications for increasing home ownership set out above, Munroe summarised the perceived UK advantages set out in the past 25 years of UK housing “discourse” as:

- capital gains

- time limited mortgage payments

- better quality houses and neighbourhoods

- independence, security, and pride of possession

The generally favourable economic climate over the previous 25 years had also encouraged owner occupation – increasing affluence, rising consumerism, financial deregulation and competitive mortgage finance, combined with periods of low interest. It is in this context that Munroe reviews both right to buy (RTB) policies and low cost home ownership. Noting the clear impact of RTB in increasing ownership amongst former social housing tenants, she notes the difficulty of coming up with a clear value for public money argument for the policy given the initial high level of public subsidy for rents through capital “bricks and mortar” grants; and the difficulties around estimating the costs of social housing replacement, and whether it will actually be done. Noting that many of the more attractive council homes have been sold and not replaced, Munroe notes the residualisation of the social housing sector; and also notes that sales have been to more advantaged social tenants, often middle aged, and more likely to be in work, and who have then often benefited from rising house prices (quoting estimates of a tenfold increase in value over the 20 years from 1980 to 2000).

Turning to LCHO schemes, Munroe notes that the 1999 Homebuy had been extended in 2005, making it available to a wider range of first-time buyers than just social housing tenants, and also using commercial mortgage lenders in addition to the Housing Corporation public sector funding. There was also a “Starter Home Initiative” (later called the Housing Corporation Challenge Fund Initiative and not to be confused with the current Government’s 2014 “Starter Homes Scheme”), which provided subsidised equity loans for key workers who were first-time buyers working in London or other defined pressurised areas. Generally these schemes did not stimulate new building, but rather helped some people to buy on the open market – in competition with other “normal” purchasers. Evaluation of these schemes indicated low take up, little evidence that they extended home ownership significantly to those who cannot afford it, and used in half the cases by households who would have bought anyway at a slightly later date. In addition, however, Munroe provides a comparison of benefits framework which highlights the corresponding impact on social housing, an element which is less prominent in later evaluations of LCHO schemes.

Table: Comparison of benefits of different LCHO schemes

| Type | Additional housing? | Additional social housing? | Creates additional letting? | Recycling? | Flexibility for purchaser? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RTB | No | Reduces stock | No | No | No |

| Right to Acquire | No | Reduces stock | No | Yes | No |

| Conventional shared ownership | Yes | No | Yes if taken by social tenant | Yes | Yes if HA operates ‘staircasing down’ |

| Homebuy | No | No | Yes if taken by social tenant | Yes | No |

| Cash incentive schemes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

Source: Munroe 2007

Overall the table needs a bit of explanation given the changing nature of LCHO since 2007. RTB/Acquire reduces the stock by permanently removing social housing from future rental. “Additional lettings” are created where a household moves to ownership and thereby creates a vacancy for a new social housing letting. “Recycling” refers to whether the subsidy returns to the social landlord/public funding agency on resale (to invest in further LCHO or social housing schemes); and “flexibility” refers to whether the participating home providers allow discretion over which homes are available within the scheme. The point is that this evaluation considers the important issue how far access to social housing is affected by LCHO schemes, rather than being focused mainly or solely on the overall rate of new house construction and the overall rate of owner occupation.

McKee (2010) provides a review more focused on the Scottish experience (which is included in the UK focus of this paper). This paper sets home ownership initiatives in the context of regeneration and mixed tenure schemes, where the aim is to tackle concentrations of disadvantage by offering a “better balance of housing types and tenures”[footnote 9] with the aim of both attracting higher income groups to the area and also of providing the opportunity for “successful” local residents to remain in the area. The mechanisms included the sale of public housing, the inclusion of affordable housing in new private housing developments, and the growth of shared equity and of shared ownership schemes.[footnote 10] The particular focus of this evaluation was the 2007 Low- Cost Initiative for first-time buyers (LIFT). The paper notes Scottish Government estimates that the public subsidy to provide a new build social housing unit has a target level of £75,000 compared to a median government contribution of £43,000 for a new shared ownership unit, indicating public expenditure benefits of shared ownership. The main part of the paper explores qualitative interviews with low income households who have taken advantage of the LIFT scheme in two deprived areas in the west of Scotland, and indicates a range of problems including the difficulties of meeting the additional costs of ownership including insurance repairs and maintenance; the limited range of financial products available for funding purchase under the scheme, leading to higher premiums for borrowing and restrictions on use and resale, and the difficulties for shared owners to “staircase” up to higher levels of equity share. These are issues which this report revisits later, particularly in relation to shared ownership.

The global financial crisis of 2007-08 led to increased difficulties in sustaining low cost home ownership, not least as the use of lax lending criteria to encourage unsustainable ownership (including loans to “NINJAs” (no income, no job, and no assets)) had been one of the major causes of the financial crisis, as is explored in Bone (2010). That paper notes the impact of the UK housing “bubble” and its aftermath from a “perspective that views secure and affordable housing to be the essential foundation of stable and cohesive societies, with its absence contributing to a range of social ills that negatively impact on both individual and collective well-being”[footnote 11], and criticises the idea of housing as a purely economic asset. Noting that price and the availability of credit are key factors that influence a household’s decision to purchase a home, the author reviews the evidence around low interest rates as drivers of consumption (and hence economic activity) linked to the growth of mortgage securitisation products which led to excessive and risky credit expansion in the mortgage markets during the pre-crisis period, and parallel house price inflation. The report considers the impact of high mortgage costs on low income families, and the strain on balancing family life with the need to maximise earnings to meet these costs. It also considers the alternative of private renting as an alternative, flagging increasing lack of security and rising rental costs.

One key issue in government funding of LCHO is whether the beneficiaries are brought into otherwise unattainable home ownership, or rather just brought into inevitable home ownership at a younger age. A 2012 IFS report looked at the impact of housing market conditions and incomes on home ownership rates at different ages (Bottazzi et al 2012), through detailed analysis of two birth cohorts at age 22 (born in 1967 and 1975). The first cohort faced a fast rising housing market with a high income to prices ratio[footnote 12] of 5.5 making house purchase expensive. By contrast the later cohort were in a position where incomes had been catching up with prices, and the income to price ratio was lower at 4, and hence home ownership more affordable. Their study examines how far first-time buyers “catch up” in terms of eventually becoming owners, but at a later age depending on the shifting waves of affordability at the point they reach specific age thresholds. Their conclusion, looking at patterns over the last forty years and over three housing booms and two housing busts, is that birth cohorts who were unable to get on the housing ladder by age 30 were nevertheless subsequently able to “catch up” to a large degree with cohorts that experienced more favourable initial conditions, with 80% of the “ownership gap” being closed by age 40. The importance of this study is that it suggests that LCHO schemes may in some cases bring forward already likely home ownership, rather than enabling ownership amongst groups who would not otherwise ever be able to own, although Williams (2014) suggests that more recent changes in the mortgage and labour markets may have introduced structural changes which undermine this finding for the future.

House of Commons (2016) has set out a useful summary of evaluations and impacts of LCHO schemes during this period, citing both parliamentary and other government sources and also wider professional body comments such as from the Chartered Institute of Housing (CIH), as well from press commentators. The CIH and National Housing Federation comments from the Labour period (in 2005) mention the risks of diverting funds to LCOH from social rented housing investment; and CIH comments from 2011 and from 2013 stressed the need to focus attention on overall house construction.

The Public Accounts Committee report into Help to Buy equity loans (PAC 2014) noted the need for future evaluation to consider whether “more buyers purchase properties than would have without the scheme, whether builders build more houses than they would have built otherwise, and what effect the scheme could be having on house prices” – three of the recurring themes of evaluation of this type of LCHO investment. The National Audit Office also published a review of the Help to Buy equity loan scheme in 2014 (NAO 2014). This recapped that this scheme was put in place to address the barriers of unaffordability, access to deposits, and lack of supply, with the objectives of improving the affordability of and access to mortgage finance and encouraging developers to build more new homes. The aim at that point was stated to make equity loans to 74,000 people using the allocated £3.7bn, between 2013-14 and 2015-16. In fact data to 30 September 2016[footnote 13] shows that at that point (before the end of the targeted period) these aims had been exceeded with 100,284 properties purchased with an equity loan, at a total cost of £4.64bn. Of these purchases 81% were by first-time buyers.

A major review of the impact of this Help to Buy equity loan scheme was subsequently undertaken by an independent set of researchers for DCLG (Finlay et al 2016). This report estimated that Help to Buy had generated 43% additional new homes over and above what would have been built in the absence of the policy, equivalent to contributing 14% to total new build output to June 2015. This is a positive finding. Looking at the extent to which low income households are gaining access to home ownership, however, the findings are more nuanced. The report set out that the average (mean) gross household income at the time of the Help to Buy Equity Loan purchase was £47,050, and the median income was £41,323.This compares to a mean gross household income of owner-occupiers with a mortgage in England who were first-time buyers (and resident for less than 5 years) of £47,528, and a median of £39,834. These median figures are from Council of Mortgage lenders figures, and the report sets out a range of qualifications as to why the median income of all first-time buyers is actually lower than the median for buyers in the Help to buy scheme. More generally the report sets out that some 61% of users said the scheme had enabled them to start looking to buy earlier than they would otherwise have done (suggesting that they intended to buy in any case), because they needed a smaller deposit – and the September 2016 figures confirm that 62% of households using the scheme put down deposits of 5% or less. Many users said the scheme had enabled them to buy a better property, or one in a better area, than they were originally looking for, and around three in five said they would have bought anyway. The authors note their findings as “median income levels of first-time buyers using the scheme (who make up the majority of the sample) are in line with national estimates” by which they mean national estimates of all first-time buyers, but make no observation on how far this helps new lower income first-time buyers, or targeted unrepresented groups. Below the report explores further the failure of Help to Buy equity loans to reach these households at the lower end of the income distribution.

A recent source of information on the wider housing market and the stimulation of home ownership generally is the Redfern Review into the decline of home ownership (Redfern 2016). The Review’s analysis indicates that:

….the primary causes of the 6.2 percentage point fall in home ownership between 2002 and 2014 are the higher cost of and restrictions on mortgage lending for first-time buyers – namely tougher first time buyer credit constraints. This is estimated to have cut 3.8 percentage points off the UK home ownership rate from 2002 to the end of 2014. ……[In addition] the biggest contributor to the fall in the home ownership rate before the financial crisis was the rapid increase in house prices…. The third major driver of the fall has been the decline in the incomes of younger people, aged 28-40, relative to people aged 40-65, i.e. the income of first-time buyers relative to that of non-first-time buyers. This younger age group’s average income fell from approximate parity with the over-40s to some 10% below in the wake of the financial crisis…. pulling down the homeownership rate over the period by around 1.4 percentage points.

The report has a focus on young people and first-time buyers, but also comments on the targeting of LCHO schemes, recommending on p45 that:

it does bear inflationary risk. Consideration should be given to targeting it more exclusively to first-time buyers and lower price points on a regional basis, whilst extending its term beyond 2021 for this restricted group. Retaining its use on an ‘unrestricted’ basis as today can then be considered as a countercyclical.

Australia has had perhaps the longest experience of low cost home ownership schemes in a reasonably close comparator nation, and has an extensive evaluation literature. Figure 9 summarises the long history of these schemes:

Figure 9: Overview of Australian low cost home ownership schemes

| Date | Scheme | Terms |

|---|---|---|

| 1918 | For returning ex- servicemen | 45 year loans |

| 1964 | Housing Savings Grant | $1 for every $3 saved for home ownership up to $500; under 36 married or engaged couples only; house price limit |

| 1973 | Mortgage interest scheme | MIRAS for incomes under $14k |

| 1976 | Home Deposit Assistance Grants | $2 for $3 saved, up to $2,500; no other restrictions |

| 1983 - 1990 | First Home Owners Assistance Scheme | Grant for up to $7,000 (then $6,000) subject to income test; house price limit. In all 0.3m benefited, $1.3bn spent, average $3.800 |

| 2000 - present | First Home Owners Grant (FHOG) | Grant up to $7,000, no income test or house price limit. In many States, topped up by State government e.g. Victoria by $5,000 in rural areas. Spend approx $1bn pa |

Eslake (2013), and economist with the Australian think tank The Grattan Institute, in his evidence to the Australian Senate Economics References Committee enquiry into Affordable Housing, set out a detailed analysis of the history of these policies, concluding that they had served to inflate the demand for housing – and in particular, the demand for already-existing housing – whilst doing next to nothing to increase the supply of housing; that they had therefore made housing affordability worse, not better; and that to the extent that the ownership of residential real estate is concentrated among higher income groups the policies had exacerbated inequities in the distribution of income and wealth. In particular it appeared that negative gearing and first-home buyer grants had mostly lifted the price of established homes, rather than boosting ownership rates or significantly lifting housing construction, concluding. In a previous comment (cited in Randolph et al 2013), Eslake had summarised his view as:

It’s hard to think of any government policy that has been pursued for so long, in the face of such incontrovertible evidence that it doesn’t work, than the policy of giving cash to first home buyers in the belief that doing so will promote home ownership

Further evidence around the impact of home ownership policies in Australia is set out in Randolph et al (2013), particularly in relation to policies in response to the global economic crisis. A “First Home Owners Boost” was introduced in 2008, building on previous schemes and in the light of the global financial crisis. This gave first-time buyers $AS 7k (about £8k) to buy an existing home (including funding from under the previous scheme), and $AS 21k (about £11.2k) to buy or build or building a new home. Individual States could top this up (for example New South Wales topped up the grant for new properties to $AS 24 (about £13.4k). This scheme ran (in varying forms) form October 2008 and the end of 2009, and was targeted only lightly on first-time buyers. The conclusion of Randolph’s study was that:

[This type of] a one-off stimulus simply acts to bring forward demand in a once and for all process which then results in a slump in demand…. While it may shore up demand during a period of market uncertainty, the effect may simply be to exacerbate the problem once the immediate positive impact of the intervention has passed through the system. The policy of a short-term boost to demand without additional measures to address either longer term affordability problems or improving first home buyer access barriers therefore does not offer a sustainable option for policymakers. On the other hand, as a countercyclical support to the market to allow a breathing space while other sectors recover, it might be seen to fulfil a longer term role (p63)

The next sections focus more on the extent to which low income and other targeted groups in England have benefited from LCHO schemes, and the wider elements of housing options for low income households.

Section 4: Do low income and targeted groups benefit from LCHO schemes?

This paper focuses on the specific question of the extent to which lower income and other groups targeted from a social mobility point of view are benefiting from LCHO schemes in England. That is, whether the schemes help people who otherwise could never buy or just bring forward the purchases of those who eventually would have become home owners anyway.

In considering this, it is helpful to look both at the incomes of households benefiting from these schemes, and at the prices of properties bought.

Figure 10 below provides a breakdown of the incomes of users of the scheme up to September 2016. The weekly median income for working age adults in England of £507[footnote 14] is roughly equivalent to an equivalised net income of £26,500 – although recorded Help to Buy incomes are provided as gross income, which makes direct comparison difficult. Neverthless, even if we assumed that the total amount of that net income had been subject to a 20% tax rate (after allowances) this would be the equivalent of around £29,640 gross, and most likely less (as the amount is likely to include tax credits or other similar non taxable in come) – but this figure should be treated as indicative only. Figure 10 shows that some 80 per cent of Help to Buy scheme beneficiaries have incomes above £30,000.

Figure 10: Help to Buy first time Buyers’ household incomes at 9/16

| Total applicant household Income | Percentage (First Time Buyers) |

|---|---|

| £0 – £20,000 | 3% |

| £20,001 - £30,000 | 17% |

| £30,001 - £40,000 | 25% |

| £40,001 - £50,000 | 21% |

| £50,001 - £60,000 | 13% |

| £60,001 - £80,000 | 12% |

| £80,001 - £100,000 | 5% |

| Greater than £100,000 | 3% |

Source: DCLG Help to Buy Tables December 2016.

This is in line with evidence from a major evaluation of Help to Buy Equity Loans outcomes published by the Department for Communities and Local Government in December 2016,[footnote 15] which indicated that the median income of scheme beneficiaries, at £42,000, was well in excess of the working-age median income in England (although in line with the median income of first-time buyers overall). This clearly suggests that the scheme was not helping lower-income first time buyer households.

As noted above, some 61 per cent of users said that the scheme had enabled them to start looking to buy earlier than they otherwise would have done (suggesting that they intended to buy in any case), because they needed a smaller deposit or buy a better property, or one in a better area, and around three in five said that they would have bought anyway.

The high cost of housing means that these schemes are beyond the reach of almost all families on average earnings. This can be seen by comparing incomes to prices regionally. Figure 11 below looks at the ratio of lower quartile house prices to lower quartile incomes in selected local authority areas; they are ranked from high to low. The local authorities shown are indicative, but looking at all authorities the 2015 ratio is over 10 in the top 103 authorities, with the London Borough of Kensington and Chelsea highest at 30.7- while there are only 32 authorities (10%) with a ratio under 5. This underlines the increasing difficulty faced by lower-income households in finding housing that they can afford to buy.

Figure 11 Ratio of lower quartile house prices to lower quartile earnings in selected local authorities 1998-2015

| Authority | 1998 | 2008 | 2015 | 2015 Rank (of 325) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kensington and Chelsea | 10.5 | 21.4 | 30.7 | 1 |

| Sevenoaks | 5.6 | 9.5 | 13.4 | 32 |

| Brighton and Hove | 4.0 | 10.1 | 11.6 | 60 |

| Reading | 4.1 | 8.2 | 9.5 | 118 |

| York | 3.9 | 8.6 | 8.9 | 144 |

| Milton Keynes | 3.5 | 7.3 | 8.4 | 170 |

| Bristol, City of | 3.2 | 7.6 | 8.2 | 182 |

| Southampton | 3.5 | 7.0 | 7.4 | 207 |

| Newcastle-under-Lyme | 3.0 | 6.4 | 6.0 | 258 |

| Leeds | 3.3 | 6.3 | 5.8 | 267 |

| Newcastle upon Tyne | 3.1 | 6.2 | 5.8 | 268 |

| Birmingham | 2.9 | 6.2 | 5.5 | 276 |

| Sheffield | 2.9 | 6.0 | 5.3 | 282 |

| Manchester | 2.1 | 5.4 | 5.2 | 287 |

| Preston | 2.9 | 5.8 | 4.8 | 300 |

| Liverpool | 2.1 | 4.6 | 4.2 | 315 |

| Burnley | 1.8 | 3.7 | 2.7 | 324 |

| Copeland | 1.8 | 3.8 | 2.6 | 325 |

Source: DCLG Live tables Table 576: ratio of lower quartile house price to lower quartile earnings by Local Authority

The same point can be made in terms of housing costs. Figure 12 below shows that only 19 per cent of Help to Buy Equity Loan completions to date were for homes worth less than £150,000. A £142,500 mortgage (i.e. with a 5 per cent deposit) would cost roughly £700 a month to service, or around 32 per cent of the median household disposable income. The top of the next band, £200,000, encompasses 48 per cent of purchases, but the payments on an associated mortgage would exceed the generally recognised 40 per cent limit of affordability for a median-income household.

Figure 12: Help to Buy average house prices at September 2016

| Purchase Price | Cumulative completions | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| £0 – £125,000 | 8,518 | 8% |

| £125,001 - £150,000 | 11,181 | 11% |

| £150,001 - £200,000 | 28,587 | 29% |

| £200,001 - £250,000 | 20,918 | 21% |

| £250,001 - £350,000 | 20,306 | 20% |

| £350,001 - £500,000 | 8,847 | 9% |

| £500,001 - £600,000 | 1,927 | 2% |

| All properties | 100,284 | 100% |

Source: Department for Communities and Local Government, Help to Buy (Equity Loan) quarterly statistics, December 2016, Table 3: Cumulative number of legal completions to 30 September 2016, by purchase price.

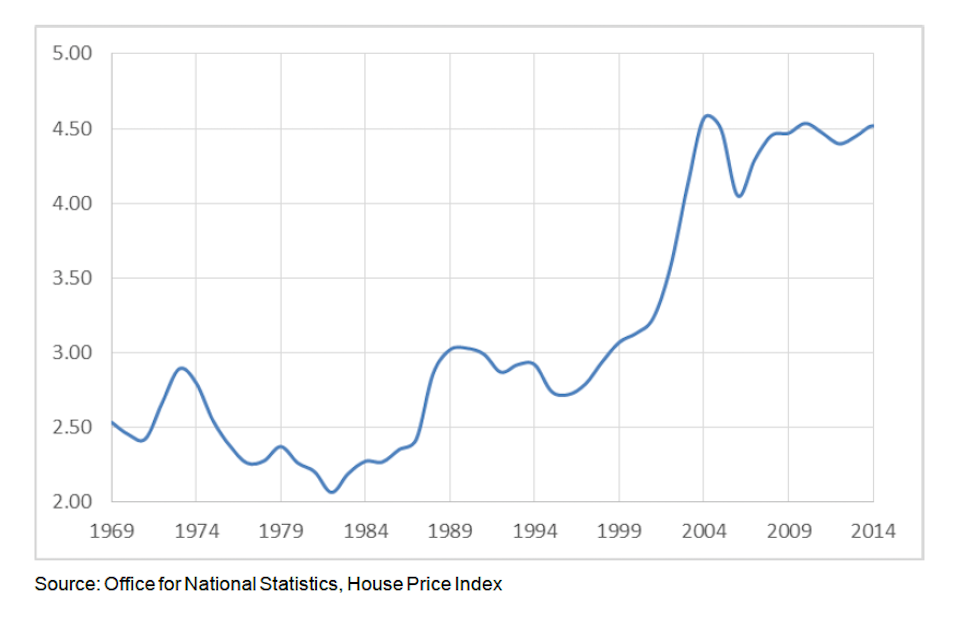

Underlying these data are the wider patterns of house price rises and income changes, as highlighted by Redfern (2016). One of the main barriers to increasing first time and low income household access to home ownership is rising house prices. With house prices increasing significantly more than wages in many areas, getting a foot on the housing ladder has become more and more difficult as has been regularly noted by reviews and evaluations of schemes to increase first time and low income home ownership (much of this evidence is sumarised in House of Commons (2016)). Figure 13 below depicts the house price to income ratio for first-time buyers since 1969. This ratio was below three (and mostly below 2.5) until the late 1980s, when it began to rise. After a short downturn which bottomed out in 1996 (the trough of the 1990s housing-market cycle), it began to rise steeply. It has not fallen below four since 2003.

Figure 13: First time buyer house prices/incomes ratio (ratio of simple averages)

Source: Office for National Statistics, House Price Index

Section 5: Discussion and options for low income and targeted first-time buyers

Overview

The evidence set out so far has indicated that there have been cross government policies to encourage higher levels of home ownership generally. The original policy of Right to Buy was the most important stimulant for social housing tenants to receive discount subsidies to move to home ownership, which between 1980-81 and September 2016 had seen a total of 2,012,711 properties sold into owner occupation[footnote 16].

Nevertheless, in terms of overall patterns of home ownership, DCLG figures on tenure show the rise and fall of owner occupation as a proportion of English tenure over the last 24 years:

Figure 14: Falling home ownership rates in the UK 1991-2014

| year | percentage of all dwellings that were owner occupied |

|---|---|

| 1991 | 65.9% |

| 1992 | 66.3% |

| 1993 | 66.4% |

| 1994 | 66.7% |

| 1995 | 66.9% |

| 1996 | 67.0% |

| 1997 | 67.3% |

| 1998 | 67.8% |

| 1999 | 68.5% |

| 2000 | 68.9% |

| 2001 | 69.1% |

| 2002 | 69.3% |

| 2003 | 68.6% |

| 2004 | 69.0% |

| 2005 | 69.0% |

| 2006 | 68.3% |

| 2007 | 67.9% |

| 2008 | 67.2% |

| 2009 | 66.3% |

| 2010 | 65.5% |

| 2011 | 64.8% |

| 2012 | 64.1% |

| 2013 | 63.5% |

| 2014 | 63.1% |

Source: DCLG Live Tables Table 101: Dwelling stock: by tenure1, United Kingdom (historical series)

We can now try to address the three key questions set out in Section One above:

- What are the main barriers to home ownership for lower income groups in the UK?

- How far do LCHO schemes help low income groups overcome these barriers?

- What steps might be taken (informed by experience in other countries) to improve the effectiveness of these schemes in promoting social mobility?

An answer to the first question was summarised by Redfern (as above) as being threefold. First, higher cost of and restrictions on mortgage lending for first-time buyers, particularly after the economic crisis of 2007; second increasing house prices especially in the period before the economic crisis of 2007; and third the decline in the earning of younger people aged 28-40.

Underlying Redfern’s second, and central, issue of increasing house prices is the current insufficient supply of homes, and particularly of new homes, to meet rising demand, which is the focus of the most recent Housing White Paper (DCLG 2016).

Similarly the DCLG Secretary of State’s introduction set out:

The housing market in this country is broken, and the cause is very simple: for too long, we haven’t built enough homes…… The problem is threefold: not enough local authorities planning for the homes they need; house building that is simply too slow; and a construction industry that is too reliant on a small number of big players.

The laws of supply and demand mean the result is simple. Since 1998, the ratio of average house prices to average earnings has more than doubled. And that means the most basic of human needs – a safe, secure home to call your own – isn’t just a distant dream for millions of people. It’s a dream that’s moving further and further away.

The consequences of undersupply were set out in Prime Minister’s Foreward to this White Paper as being:

Today the average house costs almost eight times average earnings – an all- time record. As a result it is difficult to get on the housing ladder, and the proportion of people living in the private rented sector has doubled since 2000.[footnote 17]

Issues around the impact of low supply are further explored in the Oxford Economics (2016) background paper to Redfern (2016). They point out, however, that while extra supply is important to increase the absolute numbers of homeowners, the proportion of households in the owner occupied tenure group would not be particularly affected as more supply would also increase the attractiveness of other tenures by reducing rents.[footnote 18]

Having identified these barriers, however, the focus of the second research question is far do the LCHO schemes help low income groups overcome these barriers?

These barriers are significant - chronic under supply, increasing trends towards stagnant wages for younger people – and their resolution is not going to be achieved simply through low cost home ownership schemes. Nevertheless we can legitimately ask who benefits from those schemes (and the public spending they require[footnote 19]) in the context of these clearly identified barriers.

The short answer seems to be that they do assist some first-time buyers to get their foor on the housing ladder, but lack the reach to be able to assist people on low incomes or those who would not in all probability buy at some point anyway. This is not to say their overall design is defective. It is noticeable that many of the schemes do address the barriers to mortgage finance – particularly in reducing the level of deposit required, providing complementary equity loans to reduce the borrowing, supporting savings to build up the required deposit, and reducing the continuing cost of repayments through lower interest or other guarantees. In this respect they do seem to help first-time buyers in general. Nevertheless, looking at the income profile of those who benefit, and looking at the extent of the price to income ratios across the country, they do not appear to reach into a part of the market which includes genuinely new first-time buyers from groups or income categories who would not otherwise buy, as set out in Section Four above.

As set out above Finlay et al 2016 conclude – incomes of households using the scheme are no different from first-time buyers generally, and perhaps four out of five beneficiaries earn above the median income for working households. The increasingly high national and regional affordability ratios, together with the 10% decline in the incomes of younger people, aged 28-40 in the wake of the financial crisis, relative to people aged 40-65, suggests that these LCHO schemes do not provide enough targeted support to address the needs of these lower income groups, but are instead taken up by people who are already in higher income brackets and more likely to become first-time buyers without the aid of LSCHO schemes.

This evidence does not include the recently announced Starter Homes programme, although note that Shelter (2015) have published an analysis of the likely reach of that programme. This programme creates a new category of lower-cost homes in new developments. These will be sold to first-time buyers between 23 and 40 at a 20% discount from market value (with a ceiling price of £250,000, or £450,000 in London). There will also be a 15 year repayment period for a starter home so when the property is sold on to a new owner within this period, some or all of the discount is repaid.

The exact scope of the Starter Home initiative has changed slightly since it was first announced. The 2016 Housing White Paper[footnote 20] indicated that the original plans for a mandatory requirement of 20% starter homes on all developments over a certain size would be dropped, although the national policy framework (NPPF) would be amended to introduce a clear policy expectation that housing sites deliver a minimum of 10% affordable home ownership units, as well as being amended to allow more starter homes on brownfield sites (including through the support of a £1.2bn brownfield Starter Home Land Fund) and allowing starter homes in certain rural exception sites. In summary:

Starter homes will be an important part of this offer alongside our action to build other affordable home ownership tenures like shared ownership and to support prospective homeowners through Help to Buy and Right to Buy (p 60)

In January 2017 the Government announced the first wave of 30 local authority partnerships – selected on the basis of their potential for early delivery – to build these Starter Homes on brownfield sites across the country. The partnerships have been established under the £1.2 billion Starter Homes Land Fund which supports the development of starter homes on sites across England, as announced early in 2017. The intention is that there will be 200,000 starter homes built in the life of the parliament. Shelter’s analysis uses different data sources, definitions, and more detailed range of household types from those used here, but follows a similar approach based on affordability and prices. Their overall conclusion is that the scheme is unlikely to help the majority of people on the national minimal wage or average wages into home ownership. There is an element of targeting in the most recent announcement, but it is mainly in terms of local authority readiness to proceed with the house construction.

Fixing our broken housing market (accessed 6/2/17)

A parallel study recently published by the Social Mobility Commission (Udagawa and Sanderson 2017) has explored other routes for some new forming young households to overlapping problems of deposit and meeting regular cost from income without resort to LCHO. This is through “bank of mum and dad” which operates to provide a step up into ownership for specific first-time buyers – those whose parents or other family members provide capital or other guarantees to enable earlier ownership than otherwise would be possible for these young people. The report estimates that about a third of first-time buyers are benefiting from this type of support, with a further 10% benefiting from inheritance money. This is not an example of intergenerational upward social mobility, but rather the transmission of wealth within families who are already in the higher wealth and income social strata.

Shared Ownership

This section considers the extent to which shared ownership schemes provide an entry point to home ownership for lower income households, as an alternative or complement to the types of low cost home ownership schemes described in more detail above. As noted in several places above, Shared Ownership has formed a constant element of part of past and current Government programmes for LCHO.

Shared ownership is a programme designed to help people acquire their own homes, started with a pioneering scheme run by the Notting Hill Housing Trust in 1979. Shared- ownership homes now make up 0.4 per cent of English housing stock and around 1.3 per cent of mortgages currently held[footnote 21] There are various models, but shared owners generally buy partial shares in their homes and pay rent on the remainder. They can normally buy further shares, staircasing up to 100 per cent ownership over an indefinite period of years. Shared ownership is most often offered by housing associations who charge a subsidised rent for the remaining part of the equity. There is usually a (generous) household income ceiling – currently around £90,000 in London and £80,000 elsewhere in England.

Shared ownership is a niche market for lenders, and mortgages on these properties may attract higher interest rates due to this small number of specialist lenders Housing associations can be unwilling to have more than 10 to 15 per cent of their portfolio in shared ownership, as institutional lenders are unwilling to accept a higher proportion of shared ownership as security[footnote 22]. It may also be difficult for buyers to staircase if the price of increasing the proportion of ownership increases at a higher rate than wages, and given that increasing the share attracts legal and other charges. The Government is substantially increasing its backing for shared ownership: the 2015 Autumn Statement announced £4.1 billion funding for 135,000 additional Help to Buy shared - ownership units over the course of this parliament. As a result the sector is expected to grow by up to 70 per cent over the next five years.[footnote 23]

In terms of providing access to home ownership (albeit partial), analysis by the National Housing Federation set out in Figure 15 below shows that the average incomes of shared ownership buyers are very near the median income for working- age families in England of £26,264. Even including the cost of renting the remaining share of the property, the overall housing costs of shared ownership are considerably more affordable than those of 100 per cent first-time buyers.

Figure 15: Shared Ownership by region 2013

| Region | Average income needed to afford an 80% mortgage | Median income of shared ownership buyer | Average initial share bought | Average first-time buyer monthly cost | Average shared ownership monthly cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| England | £39,585 | £27,000 | 42% | £893 | £668 |

| South East | £44,717 | £27,500 | 41% | £1,008 | £656 |

| London | £76,258 | £33,460 | 39% | £1,720 | £857 |

| East | £38,758 | £25,787 | 43% | £874 | £630 |

| South West | £36,811 | £22,800 | 43% | £830 | £546 |

| West Midlands | £28,908 | £22,000 | 46% | £652 | £533 |

| East Midlands | £26,812 | £19,567 | 38% | £605 | £466 |

| Yorkshire and Humber | £26,586 | £19,245 | 44% | £600 | £438 |

| North West | £26,700 | £19,000 | 46% | £602 | £511 |

| North East | £23,412 | £23,979 | 45% | £528 | £509 |

Source: National Housing Federation, Shared Ownership – meeting aspiration, using Continuous Recording of Lettings and Sales RSR stands for: Regulatory and Statistical Return (CORE) data and RSR shared ownership data, 2013

Shared ownership is a complex tenure and is not without its problems and critics. A recent extensive study (Cowan et al 2015) describes shared ownership as “a politically pragmatic policy approach to combat rising entry thresholds to home ownership and weaknesses in other tenures”.[footnote 24] Amongst problems identified in that report are the legal complexity of the tenure, the responsibility for repairs and apportionment of charges being burdensome for the shared owner, service charges and the quality of service provided, resentment on the part of shared owners to being treated as “social housing tenants” (even if they partly are), and the costs and valuation figures which formed part of “staircasing” transactions. Evidence from 2012 (CCHPR 2012)[footnote 25] suggested that at that between 2001 and 2012 only 19% of shared ownership properties had staircased to full ownership due to transaction costs, incomes not keeping pace with prices, and lack of available mortgage finance.