Research report: Low Earners and workplace pension saving – a qualitative study

Published 6 February 2024

DWP research report no. 1046.

A report of research carried out by Kantar Public on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

To view this licence, visit the National Archives website.

Or write to:

Information Policy Team

The National Archives

Kew

London

TW9 4DU

Email: psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk

This document/publication is also available on our website at: Research at DWP.

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email: socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published February 2024.

ISBN 978-1-78659-592-8

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Executive Summary

This qualitative research explores the attitudes, behaviours, and experiences of low earners regarding pension saving and later life planning. 119 interviews with four groups of low earners were conducted.

Research was qualitative. Therefore, while findings explore the range of opinions of participants and key reasons underlying their views, these are not generalisable to the general population.

Key Findings:

1. Attitudes, behaviours, and experiences of low earners:

- saving into a workplace pension was generally considered desirable and important for future security.

- low earners exhibited diverse characteristics, including by age, single or dual household incomes, and level of financial vulnerability, confidence and trust in pensions. These factors, particularly age, had a greater influence on pension attitudes and the appeal of alternative pension scenarios than current earnings or pension participation.

- passive drivers of pension saving, such as lack of awareness of opt-in/opt-out rights, legacy enrolment, and auto-enrolment, were prevalent among participants.

- misconceptions from individuals that their benefit entitlement might be reduced or disappear if they started saving into a pension led some who were eligible to decide against doing so.

2. Factors influencing opt-in decisions for earners below the trigger:

- social and material factors, including employers’ own approaches, workplace norms, and pension infrastructure, had a stronger influence on pension saving behaviour than individuals’ characteristics and attitudes.

- within the sample, active pension saving was more prevalent among those who prioritised saving in general or felt financially secure at a household level.

3. Factors influencing opt-out decisions for earners above the trigger:

- reasons for opting out included a perceived need to prioritise short-term budgeting due to rising costs of living, or financial shocks and other life events.

- this decision was also observed among younger people in temporary roles with variable hours who felt more financially vulnerable, that pension saving was not yet relevant, or prioritised alternative investments.

4. Impact of proposed higher or lower contribution rates on low earners’ pension saving behaviour:

- participants generally had more negative or neutral views towards a higher earnings trigger compared to a lower one. There was a reluctance among all current pension savers to miss out on the opportunity to contribute to a pension.

- matched employer/employee pension contributions were more appealing and ‘fairer’ than higher employee contributions, especially among non-savers.

5. Flexibilities within AE to encourage greater participation:

- lowering the trigger and offering flexibility to opt down or up contribution levels were likely to encourage participation due to passive pension behaviour.

- while initially appealing, a more flexible opt-up/opt-down/opt-out scheme was seen as potentially burdensome and confusing.

Recommendations:

- targeting common misconceptions such as the interaction between pensions and benefits, may help address why some low earners have decided not to save into a pension.

- improved understanding of attitudes within smaller and micro employers may help promote pension saving in this context, overcome barriers, and identify opportunities for support.

- examining non-compliant employer behaviours could help encourage participation and tackle the misconceptions these promote.

- the option of employer/employee matched contributions merits review given its broad appeal to the low earner audience.

Glossary of terms

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Automatic Enrolment (AE) | The legal obligation for every employer in the UK to enrol certain employees into a workplace pension scheme and contribute towards it. Employees qualify for AE by earning above the earnings trigger and being aged between 22 and State Pension age. |

| Earnings Trigger | The level of annual earnings before tax at which employees qualify for AE, currently set at £10,000. |

| Contribution Rate | The percentage of an employee’s qualifying earnings that the employee and their employer pay towards their pension. |

| Income tax personal allowances | The amount of money individuals are allowed to earn each tax year before they are required to pay income tax. |

| Individual Savings Account (ISA) | A savings scheme allowing individuals to hold cash, shares, and unit trusts free of tax on dividends, interest, and capital gains. |

| Lifetime Individual Savings Account (LISA) | A savings scheme with limits on when money can be withdrawn. A LISA is accessible without a withdrawal charge to buy a first home, or from age 60 or over or where someone has a terminal illness. |

| Lower earnings limit (LEL) | The LEL of the qualifying earnings band determines the minimum level of an enrolled workers’ earnings on which they and their employer have to pay contributions. |

| Opt out | Where an employee has been automatically enrolled, they can choose to ‘opt-out’ of a pension scheme, meaning they cease active membership. It can only happen within a specific time period, known as the ‘opt-out period’. |

| Pension contributions | The payments made by employer and/or the employee into a pension plan. |

| Personal pension | Pension schemes that individuals can arrange themselves. In personal pensions, individuals choose their pension provider and make arrangements for their contributions to be paid. |

| Qualifying earnings | A band of earnings used to calculate contributions, used by most employers. For the tax years 2022/23 and 2023/24 qualifying earnings are between £6,240 and £50,270. |

| Small and medium enterprises (SME) | A business with 5-249 employees. Employer size is determined by the number of employees. The Pensions Regulator categorised employer size based on number of employees as follows: – Micro = 1 to 4 employees – Small = 5 to 49 employees – Medium = 50 to 249 employees – Large = 250+ employees |

| State Pension | A regular pension payment from the government most people can claim when they reach State Pension age. |

| Workplace pension scheme (WPP) | A way for individuals to save for their retirement that’s arranged by their employer. |

| Universal Credit (UC) | An in and out of work benefit system by which money is paid by the UK state to people who have a low income or no income, introduced in 2013. |

| Zero-hours contract | A non-legal term used to describe many different types of casual agreements between an employer and an individual. This is typically a contract in which employer does not guarantee the individual any hours of work. |

Chapter 1: Introduction

To develop understanding of perceptions and experiences of Automatic Enrolment (AE) into workplace pensions and later life planning, Kantar Public conducted in-depth interviews with low earning employees aged between 18-45 and earning between £5,000-£19,000. Specifically, the research sought to provide clarity around the merits of altering the current earnings threshold of £10,000 that triggers enrolment into a workplace pension. The report provides evidence to inform the development of effective measures to help the low-paid build up pension savings. The focus of these measures is on expanding the coverage of AE and ensuring contribution rates are set at an appropriate level, which will provide adequate retirement funds while not overburdening low-earners.

The findings in this report cover the following areas:

- factors influencing low-earners’ behaviour and attitudes towards pensions, including individual, social and material factors.

- differences in attitudes, behaviours and experiences of pension saving and later life planning between employees whose earnings are above/ below the £10,000 trigger and who are/are not enrolled in a workplace pension scheme.

- responses from low earners to hypothetical future changes to AE requirements for workplace pension schemes.

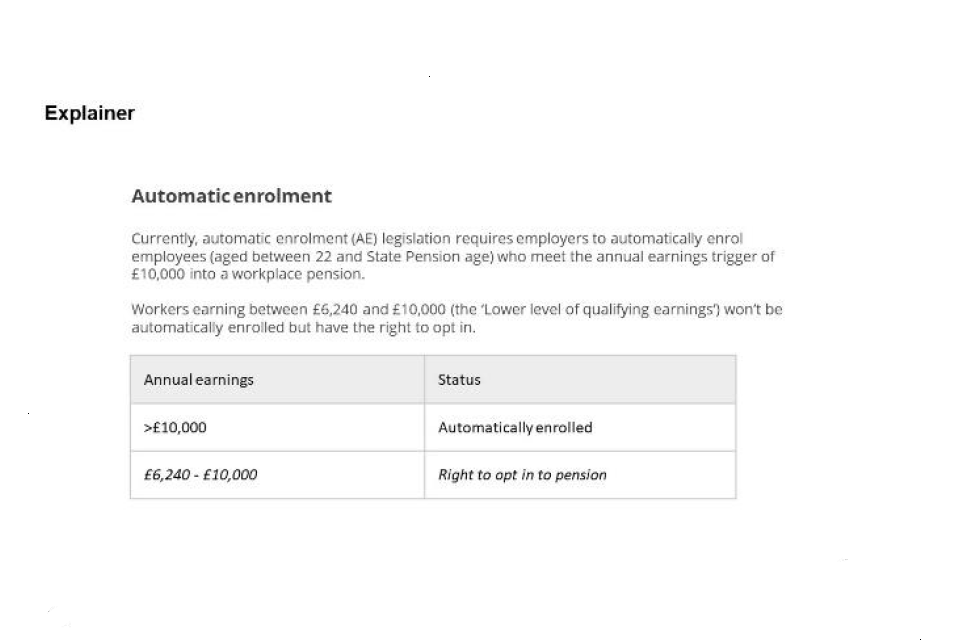

Currently, AE legislation requires employers to automatically enrol employees (aged between 22 and State Pension age) who earn above the annual earnings trigger of £10,000 in one employment into a workplace pension. Earnings are broken down and calculated on a weekly basis, requiring the enrolment of employees who earn over £192 in one week. Workers earning between £6,240 and £10,000 (the ‘lower level of qualifying earnings’) are not automatically enrolled but have the right to opt in. Employers cannot refuse and must make contributions.

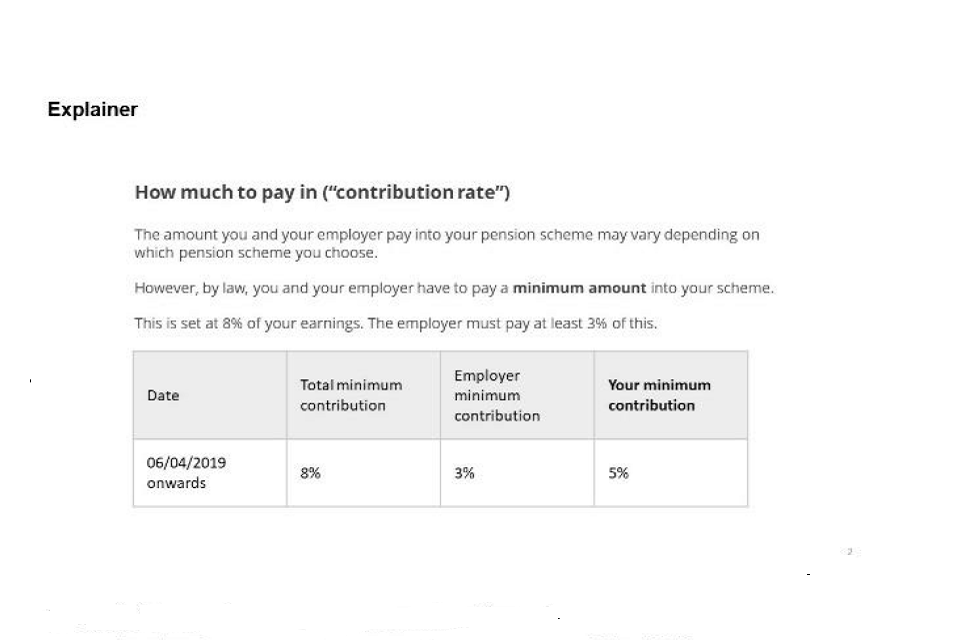

There is a minimum 8% of qualifying earnings that must be contributed into an employee’s workplace pension, including a minimum 3% contribution from the employer. Any contributions made by an employee are exempt from income tax, a feature of pension saving known as “tax relief”. The minimum contribution applies to qualifying earnings over £6,240 up to a limit of £50,270 (in the tax year 2022/23) – referred to as ‘qualifying earnings’.

In 2021, there were just under 23 million employees eligible for AE and just under 5 million who were not eligible (DWP 2022). Those ineligible included those earning below the earnings trigger and aged between 22 and the State Pension age, and those earning above the trigger and either aged 16-21 or aged over the State Pension age but not over 74.

DWP carries out periodic reviews of AE including an annual statutory review of the earnings trigger and qualifying earnings band. This review tries to balance increasing participation with not increasing the financial burden on those who cannot afford to save. The review has continued to recommend that the earnings trigger remain at its current level. (DWP 2023).

Lowering the earnings trigger would require employers to automatically enrol more eligible workers into their workplace pension scheme. This would lead to more workers benefitting from their employer’s contribution as they save into a workplace pension. However, the trigger must also protect those who cannot afford to save, ensuring AE works for those for whom it “pays to save” and ensuring employers are able to comply and keep confidence in workplace pensions high.

The current earnings trigger acts as a barrier to part-time workers and seasonal workers from participating in workplace retirement saving. Removing or drastically reducing the earnings trigger is likely to ‘catch’ more multiple jobholders. Multiple job holders are employees that could have one or more jobs that earn above or under £10,000 per annum. Those who are earning below £10,000 per annum in one employment means they are not guaranteed to be automatically enrolled on all their earnings, risking them saving less into a private pension than an employee with the same overall earnings from a single job.

Wider pension scheme participation would go some way to addressing inequalities that remain in workplace pension saving, for example the lower number of female employees who are eligible to be auto enrolled. However, the challenge is that lowering the earnings trigger risks increasing the financial strain on potentially already financially vulnerable individuals.

Previous research

Employees earning around £10,000 are a heterogeneous group of workers. These low earners include, for example; part time workers from households with a full-time earner, those on benefits struggling to maximise take-home pay, multiple jobholders, students in part-time or fixed-term employment and seasonal workers. Later life planning is minimal amongst the study’s target demographic (Foster et al. 2019) and fewer than half of those earning less than £10,000 have any private pension savings (DWP 2022a). Most pension saving commences because AE nudges employees to overcome inertia and start saving, and is maintained because of a bias for the status quo (Thaler & Sunstien 2008). The evidence suggests that employees save for retirement if they feel that they can afford to do so without jeopardising their current standard of living (James et al. 2020).

The low paid face a higher risk of job insecurity and job turnover (Cominetti et al. 2021). Lowering the AE earnings trigger risks enrolling individuals for whom it may not currently make economic sense to save. Diverting income from more pressing needs, such as debt reduction, into retirement savings could be counterproductive. Diverting income away from the day-to-day needs of the lowest earners risks impacting significantly upon their living standards, and some research suggests that the most financially insecure should not be absorbed into retirement saving but enabled instead to reduce debts and boost current consumption (Bourquin et al. 2020).

In addition, there is a concern that employees on low salaries may be more likely to opt out of workplace pensions due to financial constraints. Younger workers who are earning above the AE earnings trigger and are auto enrolled opt out less frequently than older workers, but are more likely to cite affordability reasons for doing so (NEST 2021). Stopping saving rates increased marginally when the contribution rate rose in 2019 (DWP 2020), and opt-outs from new enrolments rose during the COVID-19 lockdowns and show an increasing trend since late 2020 while remaining below their lockdown peak (DWP 2022b). Despite this, AE pension saving has proved resilient. Fewer than 1% of AE eligible employees who save into a workplace pension actively stop saving each month (DWP 2022b).

A key focus of this current research is to explore the factors influencing people above and below the earnings trigger to opt in or out of their workplace pension. This will build on existing research about issues including the influence of individual and household characteristics, social norms, and structural factors, such as employer contributions.

Individual and household characteristics: Existing research suggests that certain demographic characteristics, such as being female, are more prevalent among those below the earnings trigger who opt in (DWP 2022d). Employees may be taking a household rather than an individualised approach to saving. Earlier studies identify variations in income, education, and upbringing as instrumental factors in pension saving (Gough & Niza, 2011; Suh & James, 2021; Robertson-Rose, 2019). Previous DWP research has found that people’s income might be a determinant for their later life preparedness. For example, people on lower incomes are less likely to access any guidance to plan for their retirement (DWP 2022a).

Social norms: Saving into a workplace pension has become the norm, but there are sectoral differences in opt-out and opt in rates (ONS 2021). Participation rates are significantly higher in the public sector than in the private sector. While workplace norms are not well understood, existing research suggests that employer engagement and encouragement play a crucial role in employees’ decision to opt into pension schemes (Robertson-Rose 2019). Proactive opting-in may be a response to a combination of normative behaviours, where employers actively encourage scheme participation, and perceptions of secure upward career trajectories.

Employer contributions: Employee contributions are not usually subject to income tax, meaning that basic rate taxpayers often contribute 4% of their qualifying earnings from their net pay, which attracts a further 1% in tax relief (either implicitly in Net Pay Arrangement and Salary Sacrifice schemes, or via direct tax relief in Relief at Source schemes). Employers can contribute above the minimum requirements, and some employers encourage employees to match employer contributions. Contribution rates are higher for larger employers than smaller ones (ONS 2022). Behavioural economic theory suggests that matching contributions can effectively incentivise pension saving on an individual level (Beshears et al. 2010) but the effect this has on behaviour in the UK context is little known.

This study builds on existing understanding of the extent to which these factors are relevant to individuals’ attitudes, behaviours and experiences of pension saving and later life planning.

Research need

This research is required to provide evidence to help inform the annual statutory review of the AE earnings trigger, enabling the review to be informed by qualitative evidence on this important group of low earning employees. These findings will provide part of the wider evidence base to inform future decisions on the level of the AE earnings trigger from 2024/25 alongside other relevant considerations. Conducting this research is designed to enable a better-informed review of the earnings trigger by providing new and additional evidence on the potentially vulnerable groups of low earning employees in DWP’s AE policy design.

The research will inform the implementation of the 2017 AE Review measures, specifically the planned removal of the lower earnings limit (LEL), which DWP is committed to introducing. This change will affect the take-home pay of lower earners who do not opt-out and who receive only the AE minimum employer contribution. To that end, it is important that DWP has a better understanding of the pension saving experiences and behaviours of lower-earning groups.

The research is intended to support evidence-based decisions on policies aimed at reducing under-saving for retirement. For example, it will inform the development of effective measures to protect lower earners while expanding AE and increasing savings rates for the majority. To support future policy design, the research investigated potential flexibilities in AE to encourage participation and higher contribution rates among employees. The challenge of incorporating flexibility in AE is to encourage financial resilience while maintaining the benefits of AE inertia.

Chapter 2 provides an in-depth overview of the research design, encompassing research aims and objectives, methodology and sample details, fieldwork specifics analysis methods, and research limitations.

Chapters 3 through 5 present a comprehensive analysis of the research findings. This analysis delves into the factors that drive individual decision-making processes, highlights the discernible differences between the research participants, and explores their varying perspectives concerning future changes to AE.

Chapter 6 includes recommendations for future research.

Chapter 2: Research design

This chapter outlines the research design for this study, including the research objectives and the approach to sampling, fieldwork and analysis.

Research aims and objectives

The aim of this research was to explore people’s views about workplace pension saving under AE. Specifically, the research addressed the following objectives:

- determine the attitudes, behaviours, and experiences of lower earners above and below the AE earnings trigger regarding pension saving and later life planning.

- explore the factors influencing the decision of individuals earning below the trigger to opt into workplace pensions.

- compare the differences between individuals below and above the earnings trigger who are saving (or not saving) into a workplace pension, and assess the variations between automatically enrolled lower earners and those who have chosen to opt in.

- identify how the pension saving behaviour of low earners would be impacted by higher or lower contribution rates.

- determine if there are any flexibilities within AE that can encourage greater participation.

Research methodology and sample

Kantar Public conducted 119 in-depth interviews with low earners (defined as employees earning between £5,000 and £19,000).

Interviews were conducted either face-to-face in participants’ homes, or through video links according to participants’ preference and to efficiently cover a range of UK locations. Thirty were conducted face-to-face and 89 online. Interviews took place between December 2022 and May 2023 and lasted up to 60 minutes.

Participants were purposively sampled to achieve a spread across four groups. The groups were split across two primary variables: their earnings from paid employment being above or below the AE earnings trigger; and whether they were currently saving into a workplace pension. The number of participants falling into each group is shown below. To ensure people from a broad range of circumstances were interviewed, secondary quotas were also applied across the sample for criteria for gender and age. A full breakdown of participant characteristics is shown in Appendix A.

Table 1: Summary of the primary quotas

| Saving or not into a workplace pension | Earning below the AE earnings trigger (£5,000-£9,999) | Earning above the AE earnings trigger (£10,000-£19,000) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not saving into a workplace pension | 30 | 30 | 60 |

| Saving into a workplace pension | 29 | 30 | 59 |

| Total | 59 | 60 | 119 |

Participants were recruited using a combination of survey recontact sample drawn from the 2020/2021 and 2019/2020 Family Resources Survey (FRS) dataset, and via free-find recruitment.

As is standard practice in qualitative research, participants were given a £40 voucher to thank them for sharing their time to contribute to this study. Relevant supporting resources provided by DWP were shared with participants, as shown in Appendix C.

Please note, all names have been pseudonymised to protect the identity of individuals who took part in research.

Fieldwork

Interviews were informed by a topic guide, which was agreed with DWP in advance to ensure the areas of interest were covered. This covered the following topics (below). A full topic guide can be found in Appendix B.

- Background to participants’ lives, including their household situation, details of their employment, and any additional income streams (beyond income from paid employment).

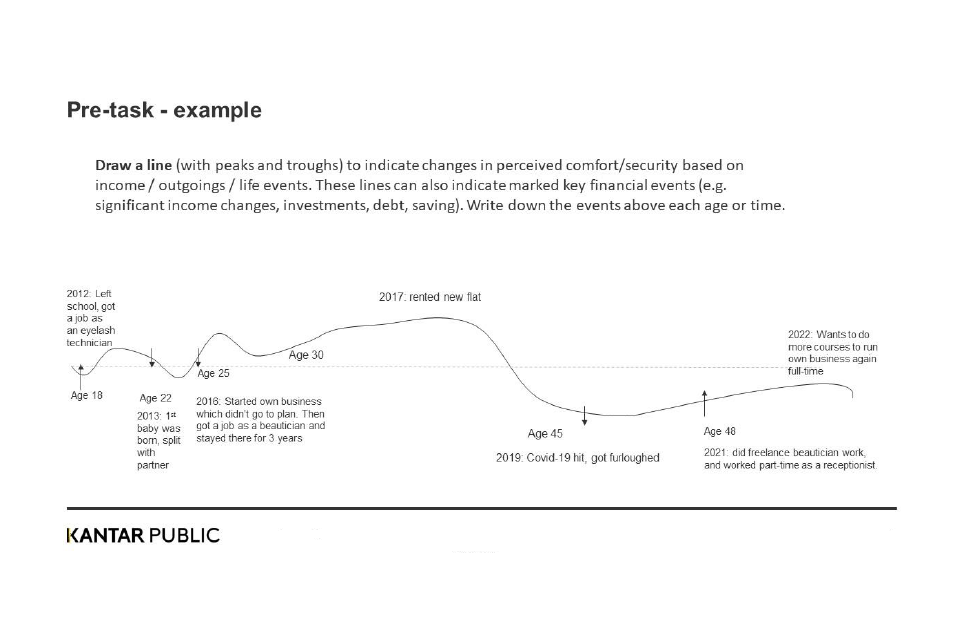

- Participants’ financial experiences over time and how these related to their attitudes, behaviours and experiences of pension saving and later life planning. This included a short pre-task activity (completed prior to the interview) where participants were asked to map fluctuations in their perceived financial security / comfort over time. During the interview, participants were prompted to consider how (if at all) these experiences influenced their experiences with AE (and later as a basis for exploring hypothetical future scenarios for AE).

- Participants’ attitudes, behaviours and experiences of pension saving and later life planning, including factors influencing their experiences with AE (opting in / out).

- Participants’ reactions to hypothetical future scenarios for AE, including; changes to minimum contribution rates, changes to the earnings trigger, and flexibilities around contribution rates (including ‘employee opt-down’).

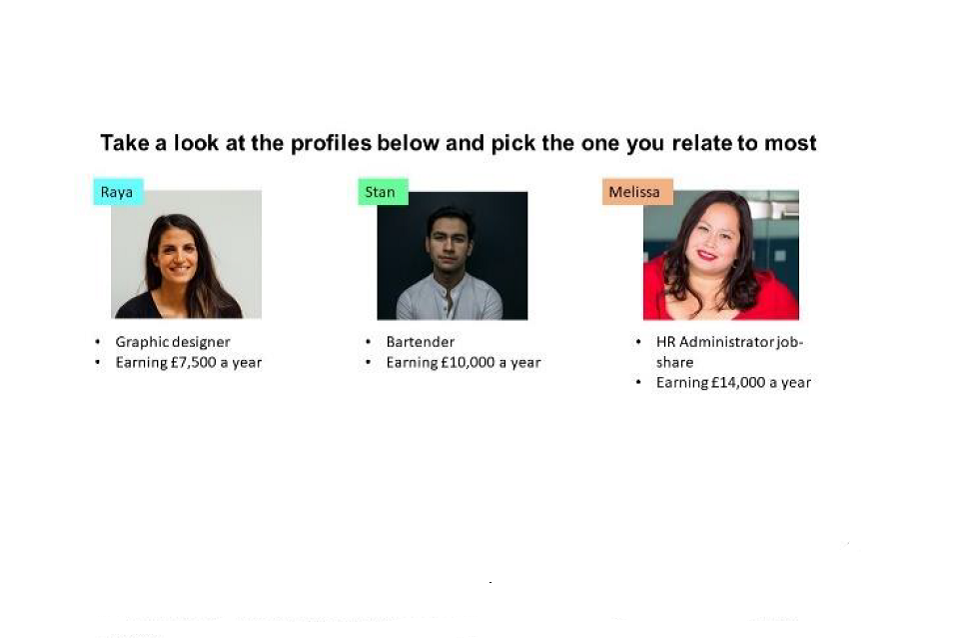

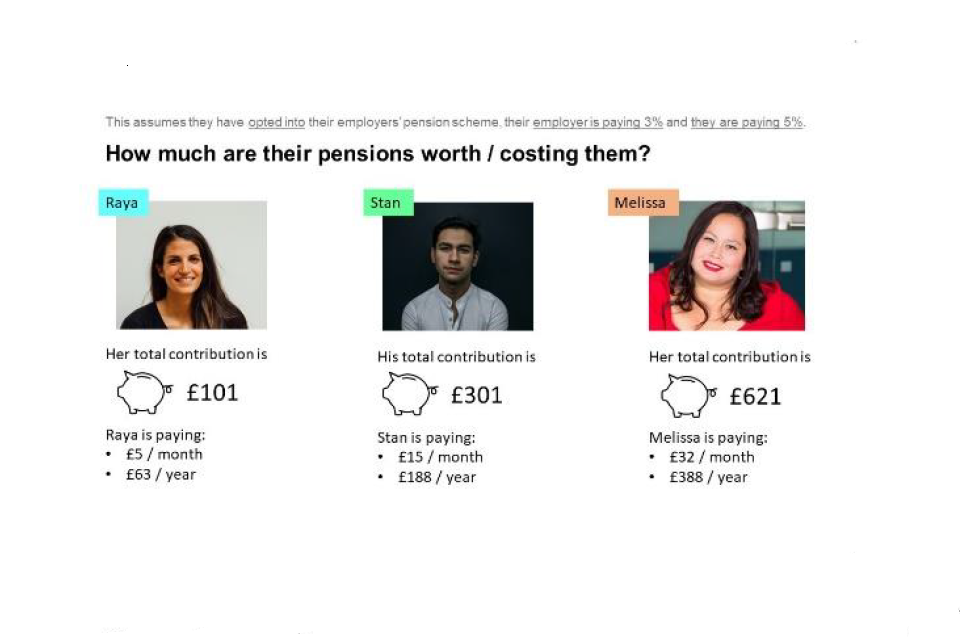

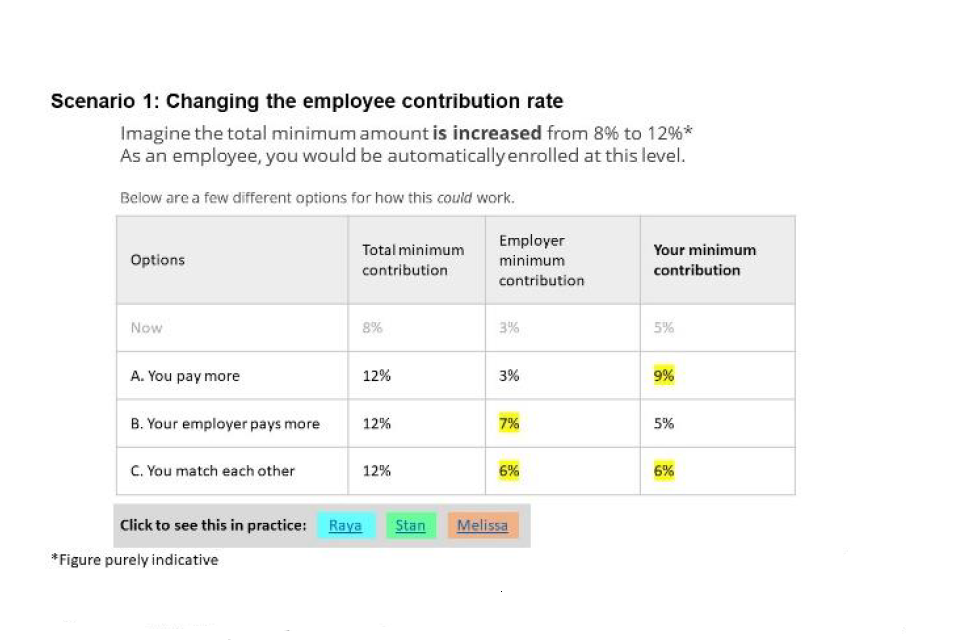

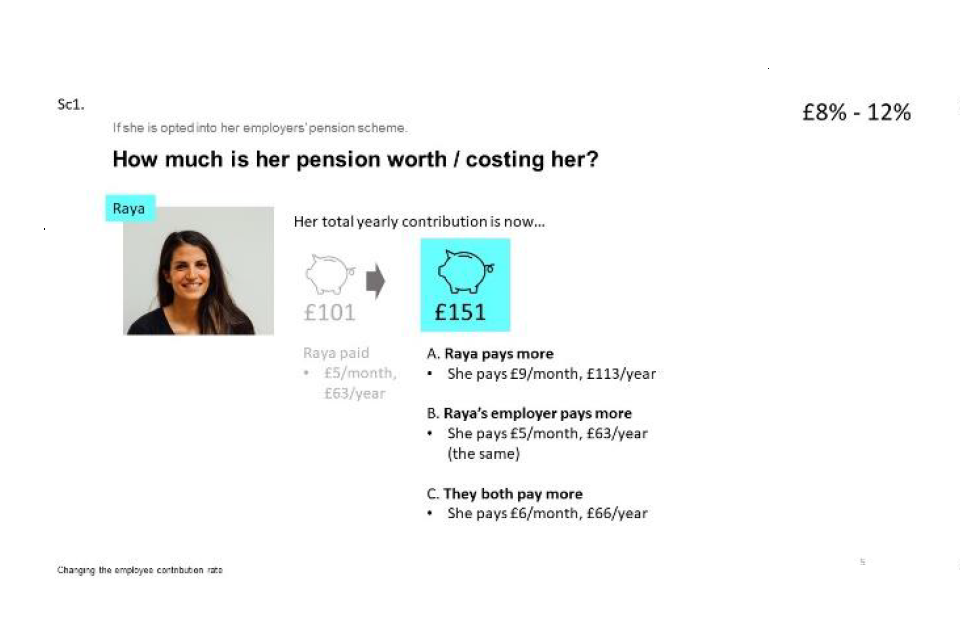

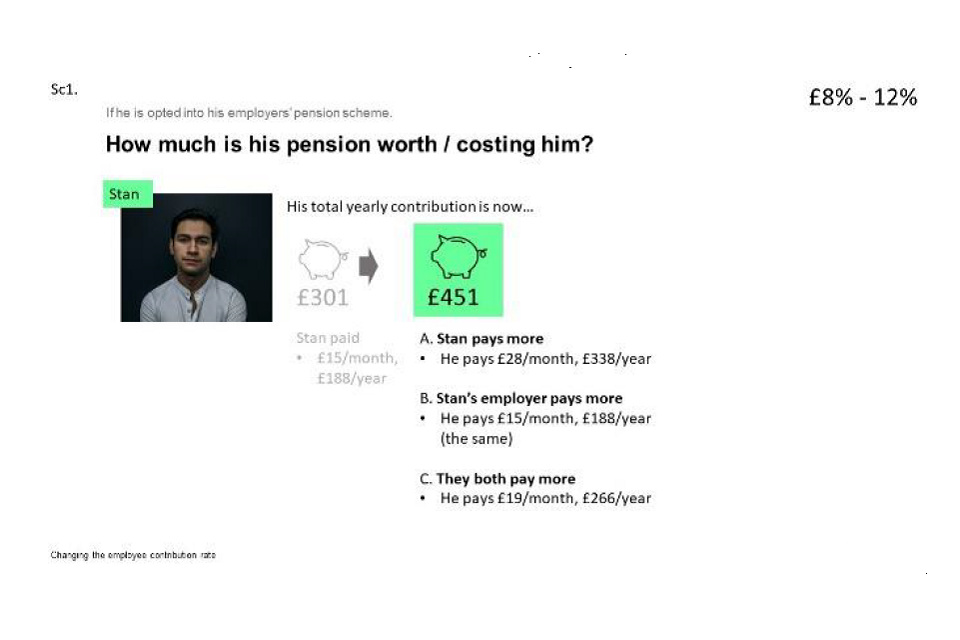

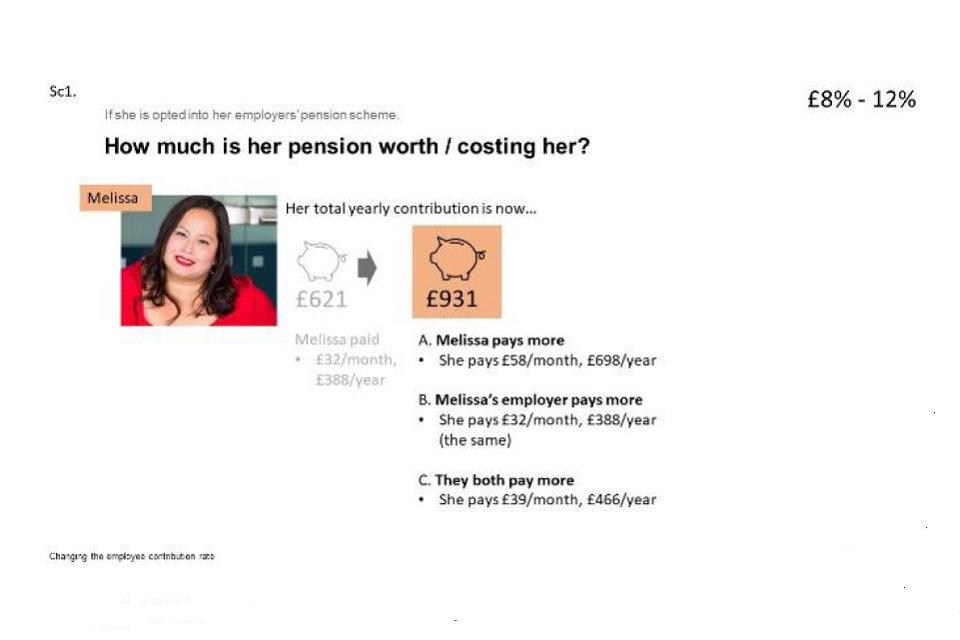

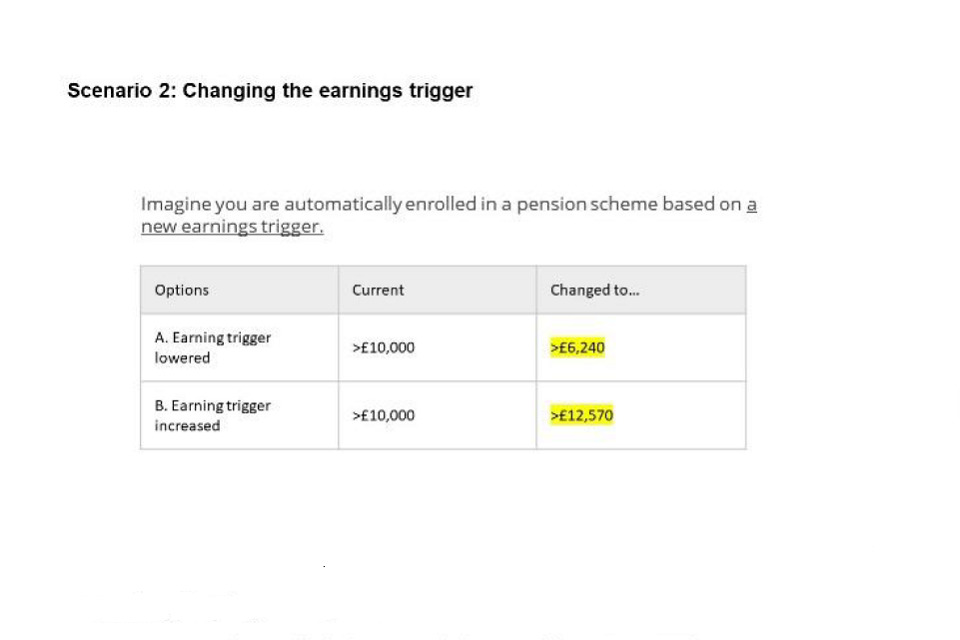

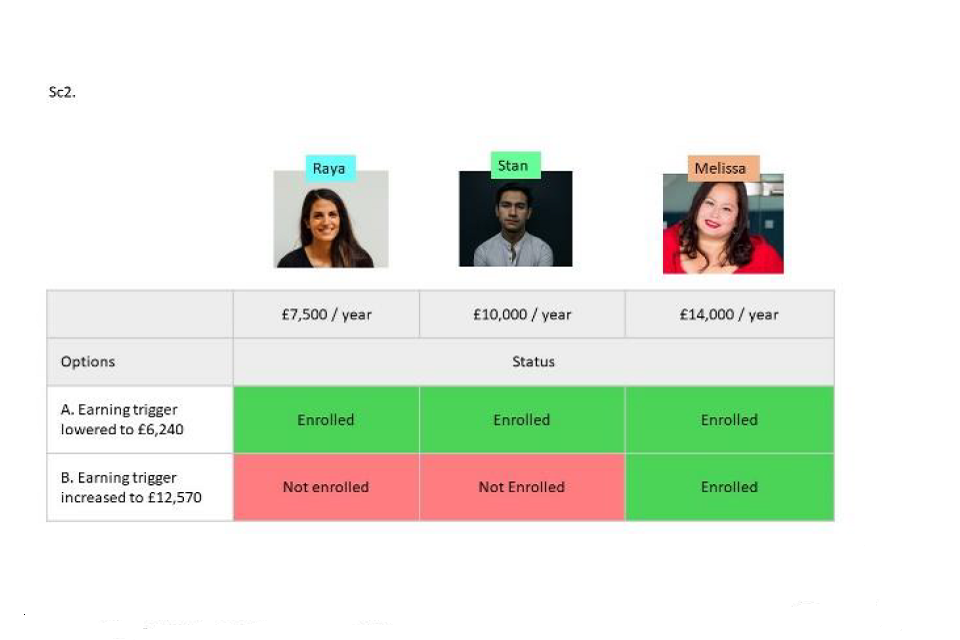

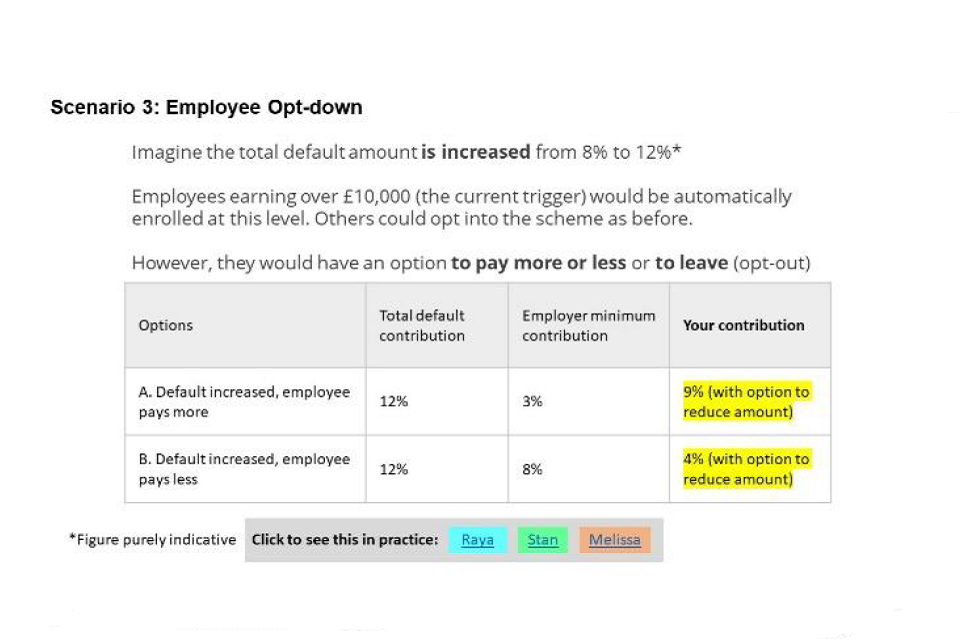

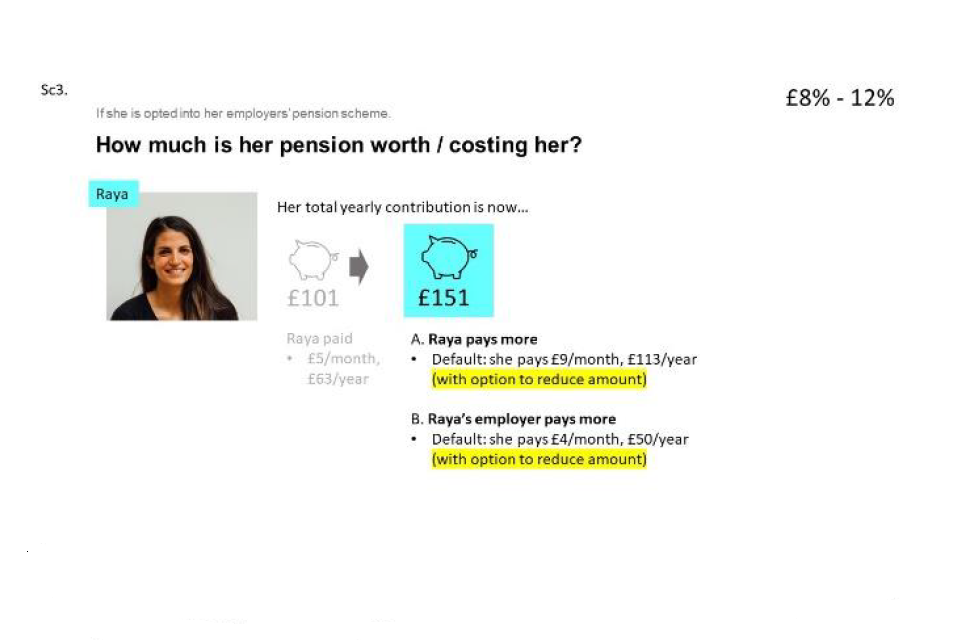

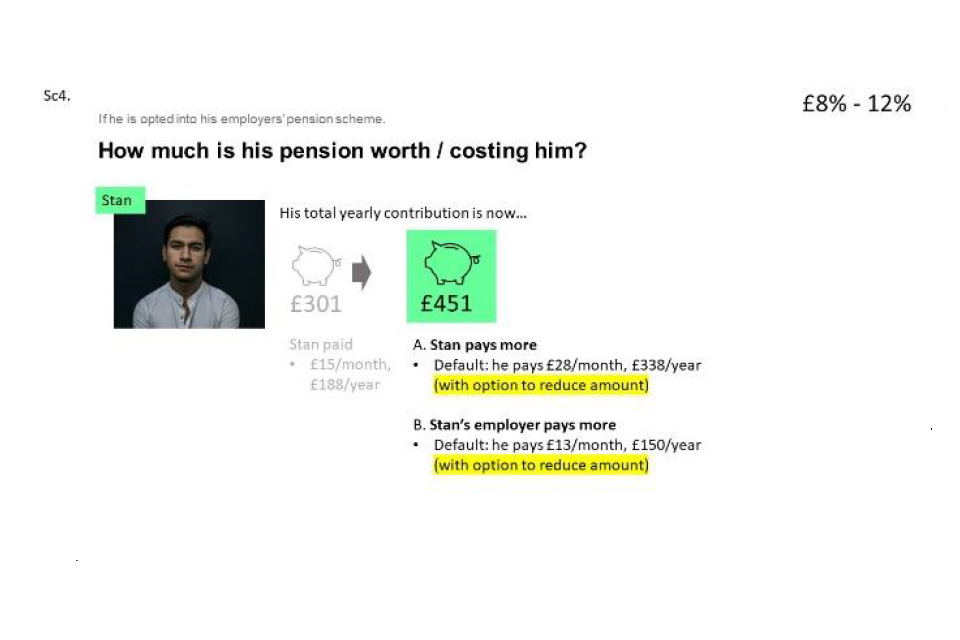

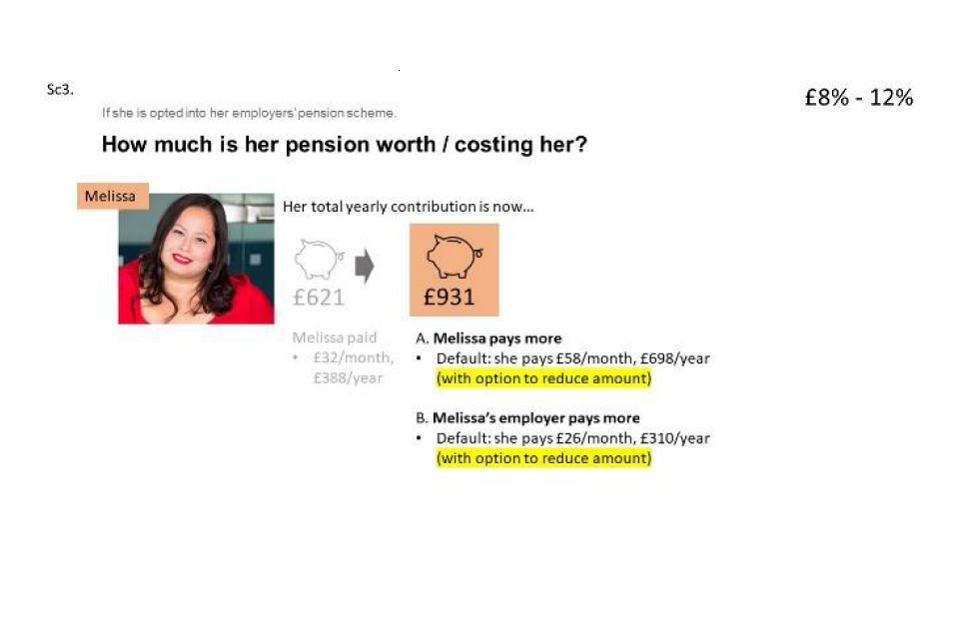

The researchers were aware of the risk of low engagement and comprehension surrounding the topic of pensions. To elicit a meaningful response from participants the research included a practical demonstration of the impact of potential changes to AE regulations. The hypothetical scenarios were accompanied by three profiles of fictional individuals, earning £7,500, £10,000, and £14,000 annually. Participants were requested to select the profile that closely resembled their own earnings. Each scenario was followed by a brief summary of the impact of this specific change on their pension contributions and/or enrolment status. This allowed participants to draw parallels between this and their current and future financial circumstances and helping them engage with the scenario. Scenarios can be found in Appendix B.

Analysis

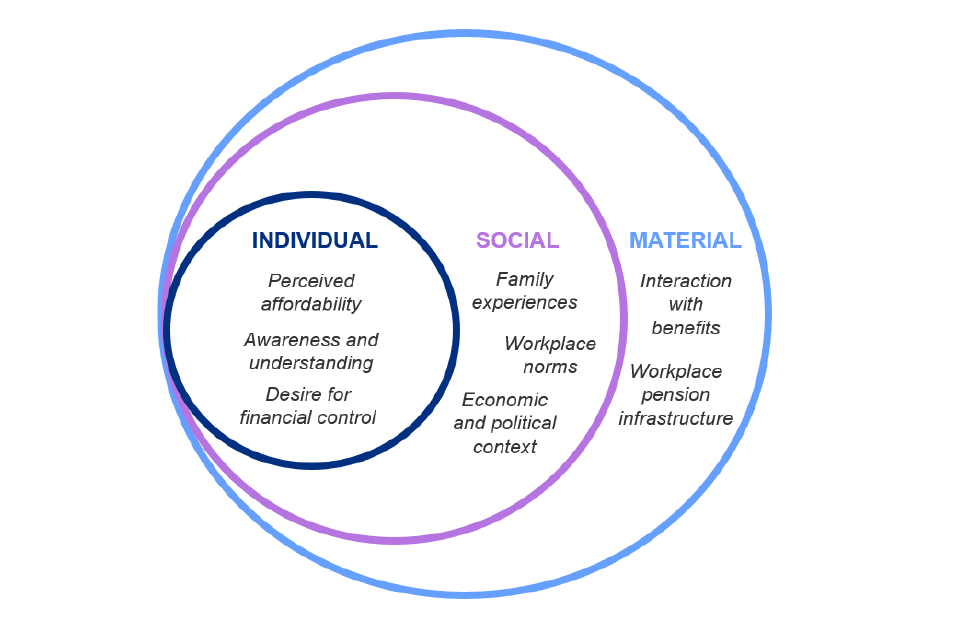

Thematic analysis was conducted using the ISM (Individual, Social and Material) theoretical framework (Scottish Government n.d.). The ISM framework was developed by the Scottish Government and is used to understand and analyse factors that influence human behaviour. ISM takes three different contexts into consideration – the Individual, Social and Material – when analysing people’s behaviours. It recognises that behaviour is not solely determined by individual characteristics but is also shaped by social interactions and the physical environment. In doing this, it provides a nuanced understanding of why people behave the way they do in different situations.

Thematic code frames were used to systematically summarise the full dataset which included detailed interview notes for each interview. Regular team discussions to facilitate data analysis were held throughout the fieldwork period, a crucial component of any qualitative methodology, which also supported the data management process.

Research limitations

This research was undertaken during a period of COVID-19-related financial disruption and subsequent rising price inflation. The research provides an important opportunity to overcome a shortfall in the evidence base relating to low earners’ retirement savings choices during a financial crisis. The findings should be considered within the economic context; during a period of rising economic prosperity their validity will need to be re-assessed.

Where participants have shown a lack of understanding of private pensions, researchers have not corrected their view, nor does this report address those misconceptions. There is evidence in this report of employees’ perceptions of employers not complying with their duties to enrol eligible employees into a workplace pension. While this is important when considering low earners’ experiences with workplace pension saving, it was not within scope of this research to investigate this in more detail or follow up with specific employees or pension regulators.

When considering these findings, it is important to bear in mind that a qualitative approach explores the range of attitudes and opinions of participants in detail. It provides an insight into the key reasons underlying participants’ views. Findings are descriptive and illustrative, not statistically representative.

The following Chapter 3 explores the influential factors driving individuals’ decision making, before differences between the principal groups are explored in Chapter 4. Respondents views on future changes to AE are reported in Chapter 5.

Chapter 3: Factors influencing low-earners’ behaviour and attitudes towards pensions

This chapter considers the different factors that underpinned participants’ attitudes and behaviours towards, and experiences of, pensions and later life planning. It outlines the range of factors that emerged from the research, before linking these factors to audience differences (Chapter 4) and responses to potential changes to AE (Chapter 5).

During the interviews, these factors were explored by asking participants to reflect on their financial journeys over time and consider the influences on their general saving behaviour (see discussion guide in Appendix B). As discussed on p.15 in the Analysis section the ISM framework was used to ensure the research explored a wide range of potential factors that influenced people’s behaviour towards workplace pensions and later life planning. The ISM framework enabled us to develop a holistic perspective and unpick factors that were most influential and therefore likely to explain audience differences and responses to potential changes to AE.

The factors that influenced saving behaviour at each layer of the ISM model – individual, social and material are summarised below (figure 1).

Figure 1: Factors that were seen to influence behaviour towards pensions at each level of the ISM model

Individual factors influencing pension behaviour

Individual factors that are known to influence behaviour include people’s attitudes and beliefs, their capability and agency, as well as their personal evaluations of costs and benefits associated with that behaviour.

The individual factors that participants flagged as influential on their behaviour towards pensions and later life planning included perceived affordability, awareness and understanding of pensions, and the desire for financial control.

Perceived affordability

While not universal, participants generally considered saving into a workplace pension to be a desirable activity and something that was important for their future. However, the extent to which people felt it was feasible for them to put aside money for the future varied considerably. For those who felt it was unfeasible to save, this was typically because they felt they needed to prioritise short-term budgeting.

Short-term budgeting for the weeks, and in some cases the days, ahead was common for many participants in our study. In particular, people cited rising energy bills and other living costs as being a barrier to saving (see ‘economic and political context’ later in this section). Those working in precarious jobs, such as short-term or zero-hours contracts also described feeling their income was too insecure to put money aside for later-life. This uncertainty around income and living costs meant people felt they either had little leftover or needed flexibility to be able to draw on any money as and when needed.

“When you’re paying that extra on your gas and electric, you don’t have that extra money to put away for your future.” (Below earnings trigger, not saving into a workplace pension)

This was a particular issue for those with dependent children, especially women. Parents in our sample described weighing the perceived affordability of pension contributions against the financial demands of supporting their children. For some, this meant choosing between investing in their own future retirement or providing for their children now, as doing both was not deemed feasible.

“I have a young family and they’re all depending on me. I have to provide for them somehow.” (Above earnings trigger, not saving into a workplace pension)

“Life gets in the way of everything. Day to day spending, [living] costs, bills, kids, holidays. You think ‘live for today’ kind of thing.” (Below earnings trigger, not saving into a workplace pension)

Where participants were less concerned about the perceived affordability of pensions, this was typically where they had access to other household income. This could be from additional jobs, investments and self-employment, or from a partner’s income. In particular, those in dual income households tended to take a household level approach to income and savings, including pension savings. If participants felt financially secure at a household level, this meant they felt able to sacrifice some of their take-home pay even if this was too little to live on if taken in isolation.

“Personally I don’t feel financially secure, because I work so few hours… but because of my husband’s work, I do [feel financially secure].” (Above earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

“My wife’s pension is the backup we’ve got for retirement. Hopefully a large teacher’s pension.” (Below earnings trigger, not saving into a workplace pension)

Awareness and understanding

A further factor influencing individuals’ attitudes and behaviours was the extent to which participants were aware of and understood pensions. While a small number of participants were able to confidently describe how workplace pensions worked, who contributed and how much, and how funds could be accessed at retirement, it was more typical for participants in our sample to acknowledge little to no understanding. They also acknowledged that this lack of understanding could be a barrier to engagement and action.

“I am really clueless when it comes to pensions. I don’t understand how they work. I am literally a blank screen when it comes to pensions.” (Below earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

Younger participants (aged 18-25) were a particular group where limited understanding was deemed a barrier to saving. For this group, retirement was typically described as being too far into the future for them to feel they needed to engage with pensions. The lack of perceived urgency meant they could delay engaging with saving for retirement until they had achieved greater financial security and higher earnings that would make saving both more feasible and more worthwhile.

“It feels quite far away to me, it’s not something I’ve given much thought to.” (Below earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

For those of all ages who felt a greater sense of urgency, a lack of understanding about pensions provoked feelings of fear and uncertainty, and in some cases paralysis. Whether or not people were currently saving into a pension, there was widespread worry they would not have sufficient funds for a comfortable retirement. In part this was related to wider concerns, such as uncertainty over their health and life expectations, the global economic outlook, and changes to the State Pension (see ‘economic and political context’ later in this section). But even for those saving into a pension, their lack of understanding about how much they would be able to access during retirement caused worry.

“It worries me to be honest because I feel I’m not building up enough for my own pension.” (Above earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

Despite this widespread concern, participants typically acknowledged that they were unlikely to engage with pensions in the near future. Even for those who felt it would be relatively straightforward to enquire about their pension, this was not something they realistically expected to do. In part this was due to the perceived complexity and uncertainty of pensions – not knowing what funds they would need for a comfortable retirement, needing to look across multiple pension pots to understand their combined situation, and uncertainty about future projections of pension investments. It also reflected a reluctance to engage with potentially negative information, and a perceived inability to save more if participants confirmed this was necessary.

“I might need a private pension. It just seems complicated to work out how to have a pension.” (Above earnings trigger, not saving into a workplace pension)

Desire for financial control

A key factor influencing people’s attitudes and behaviours towards pension saving was the degree of agency they wanted over their savings.

Participants recognised that pensions are different to other savings. A key distinction was that general savings were seen to be “controlled” by the participant and could be used flexibly with “instant access for rainy days”. By contrast, a pension pot was generally seen as something that was “outsourced and managed by the employer” with limited control for individuals, both in terms of how money is saved and how savings are accessed. The extent to which this perception affected people’s attitudes and behaviours towards pensions depended on their desire for financial control.

At one end the spectrum of views about control were those who were enrolled in their workplace pension without a strong understanding or interest in what it involved. People typically had relatively high levels of complacency about their own agency in this situation. Indeed, in a number of cases, participants explicitly valued the ease of being auto enrolled and not having to think about pension saving.

'’The workplace pension is done for you so it makes it easy” (Below earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

Pensions were generally viewed by participants as a safe and sensible way of saving for the future. The lack of immediate access to pension savings could be appealing, especially for those who did not feel completely in control of their spending.

“The good thing about pensions is you can’t spend them 3 months later… They’re helping you save because they know you’re not disciplined enough to put it there by yourself.” (Above earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

However, in contrast, a number of participants preferred greater agency over their savings. This was predominantly linked to the previous point about affordability and people’s need to prioritise short-term budgeting. For these participants, the sense that funds were locked away until retirement reduced the appeal of pensions. This led to some participants expressing a preference for alternative saving mechanisms where they had greater perceived control over access, such as savings accounts, property, and stocks and shares.

“For someone like me who has their pension many, many years away in the future, I’d rather have that money now and be able to utilise it, rather than let inflation and other factors in the world that are really unforeseeable [affect its value]…I’d rather put [my money] into liquid assets and move things around… I have some involvement in crypto currencies and stocks.” (Above earnings trigger, not saving into a workplace pension)

Concerns about handing over control of pension savings to third parties were also prevalent. Participants described low trust in the pension scheme provided by their workplace to invest pension funds appropriately. This mistrust could extend to employers more generally. Examples of pension schemes going bust or failing to pay out were cited spontaneously by concerned participants.

“I feel like you’re not really in control of your pension. I know someone who had a pension, he had quite a lot of money in his pension, and somehow he lost it…It’s nearly ten years later and it’s still not resolved” (Below earnings trigger, not saving into a workplace pension)

Some participants expressed concerns about wider issues outside their control such as the country’s economic outlook, the State Pension age, and whether savings invested now would be secure or sufficient for retirement. Even participants who were less pessimistic about pension security expressed concerns about whether the level of contributions they were making would be sufficient to support them during retirement (see Economic and Political Context, below).

“What gets in the way is the uncertainty, because how it was 10 years ago is not how it is now, so I don’t know what it’ll be like when I hit the age of retirement, especially as the age of retirement is going up all the time.” (Above earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

Social factors influencing pension behaviour

Social factors are those that “exist beyond the individual in the social realm, yet shape his or her behaviours” (Scottish Government n.d.). These include social norms, networks and relationships that might influence how groups of individuals behave.

The social factors participants identified as influential on their attitudes and behaviour towards saving and later life planning included family experiences, workplace norms, and the economic and political context.

Family experiences

Participants described being influenced by their family and upbringing in how they viewed pensions and the importance of saving for retirement. This included examples of people growing up in a family where long-term saving was encouraged and normalised, or where parents were actively engaged in supporting their children to save; for example, setting up savings accounts or even pensions on their behalf.

“My father set up my private pension for me and he was a big stock market person. And then unfortunately he passed away very suddenly and it was passed over to me, but now I am in control.” (Above earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

“[Saving into a workplace pension is] something my dad’s always done as well, the same as my mum, my step dad. I just thought it was the norm.” (Below earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

Participants described learning from the experiences of older family members in retirement. Positive experiences of family members enjoying a comfortable retirement had encouraged people to save into a pension. As did observing family members struggling in retirement due to lack of savings.

“My grandma manages but relies quite a bit on my mum and dad. You can tell she regrets not having paid into something.” (Above earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

Conversely, observing family members’ negative experiences of pensions had the opposite effect and there were examples of people being dissuaded from enrolling into workplace pensions by their family. This included parents passing on their mistrust of pensions or preference for alternative investments, such as property. For example, one participant described how witnessing his father’s pension lose value and therefore needing to continue working longer into old age to recover the value had reduced his own confidence in his workplace pensions, despite reluctantly remaining enrolled.

“My dad has lost a lot of money on his pension…Is it worth putting £5 [a month] into it if you lose it in the end?” (Above earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

Workplace norms

The default nature of workplace pensions, combined with participants’ limited engagement with pensions, meant that workplace norms were a strong influence on pension behaviour. Apart from a relatively small group of more actively engaged participants, participants typically conformed with the norms in their workplace.

For younger participants (aged 18-25) and people working in temporary contracts, this meant they were not expected or encouraged to enrol into their workplace pension. For example, a student working part-time was persuaded to opt out of her workplace pension by her manager who told her “nobody else who works part-time is enrolled.” While this is not compliant with AE legislation and could be considered an inducement to stop saving, this employee was invited at the time to talk about it with her manager if she wanted to know more information. As noted above, this workplace norm aligned with many participants’ own preconceptions, particularly that younger people should wait until they were in more established careers before considering pensions.

“I was not offered a workplace pension and I would not have bothered to opt in anyway as minimal would be going in. At this point I’d rather have the money but when I’m working as a doctor my pension will be a good one, so I’ve no worries.’‘(Above earnings trigger, not saving into a workplace pension)

Norms regarding pension saving behaviour differed by age. For older participants (aged 40+), there was a sense that now was the time to engage with pensions. Several participants spontaneously cited Martin Lewis as influencing this view, particularly through his messages that people should check their State Pension in case they needed to ‘fill any gaps’ in NI contributions, and that pension contributions (%) should be half your age. Despite acknowledging this call to action, participants were influenced by a general disengagement with pensions by their employers and peers. People described feeling uninformed about their pensions, in some cases blaming employers for not sharing information. This has a potential link with employer size, which is explored further in the section on material factors.

One interviewee had asked her colleagues about the workplace pension and had been told that nobody knew anything about it – just that they were paying in.

“When we looked at [the WPP contribution] at work everyone said it’s the worst, people were saying it’s not worth putting in because she puts in the least.” (Above earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

Similarly, very few participants recalled receiving an annual pension statement from their pension provider, which they felt might nudge them to engage more deeply[footnote 1].

“I think it [annual pension statement] would give people a bit of reassurance - most people are like, well I’m paying my pension, but they don’t know why they’re doing it.” (Above earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

Economic and political context

Linked to the perceived affordability of pension contributions, uncertainty about the economic climate was cited as a key driver of attitudes and behaviours towards pensions. On a practical level, participants described struggling to cover rising costs of essential goods and services, and needing to prioritise short-term budgeting over saving for retirement. However, the sense of economic uncertainty also prompted participants to question the value and relevance of pensions.

“Realistically I think whatever my personal movements are in terms of planning for the future, pensions are always going to be overshadowed by the global landscape, what inflation’s doing, how much tax has gone up… and I think planning for the future based on that feels somewhat useless.” (Above earnings trigger, not saving into a workplace pension)

Even if this economic uncertainty did not dissuade people from saving into a pension, it added to personal uncertainty about how much they should be saving and what they were likely to need in retirement. Some participants described supplementing their pension with more reliable sources of income such as property or, if not homeowners, placing more trust in the idea of these investments than their workplace pension.

“What gets in the way is the uncertainty, because how it was 10 years ago is not how it is now, so I don’t know what it’ll be like when I hit the age of retirement, especially as the age of retirement is going up all the time.” (Above earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

Uncertainty over the political landscape for pensions was expressed by many participants. In particular, whether State Pension age will continue to rise, or whether there will still be a State Pension when they reach retirement age. This perceived uncertainty about the State Pension was polarising, undermining the perceived value of pensions as a whole for some, while driving others to prioritise workplace pensions. This sense of uncertainty also contributed to the tendency towards inertia from participants towards their pensions and whether they should be saving into them or not.

“By the time I’m ready to retire, what you’ve saved in your pension is what you’ll be getting. I’m not sure how much of a State Pension will be left by then.” (Below earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

“Pensions just sit there… they don’t grow and won’t keep up with inflation as it is… And who knows what the retirement age will be by then – look what’s happening in France at the moment – protests about the retirement age increase.’’ (Above earnings trigger, not saving into a workplace pension)

Material factors influencing pension behaviour

Material factors are constraints and influences that exist in the wider environment that may shape behaviour, including the physical infrastructure, rules and regulations, and institutional structures. The material factors mentioned by participants as being influential on their attitudes and behaviour towards pensions and later life planning included the interaction of pensions with benefits, and their employer’s workplace pension infrastructure.

Interaction with benefits

Many of the participants in our sample were receiving income-related benefits, including Universal Credit (UC) and support with housing costs and council tax. Participant attitudes towards workplace pensions were influenced by the perceived interaction between pension funds and benefit-related savings limits.

A wide range of differing perceptions were expressed[footnote 2]. Some participants feared that their pension savings would count against them when claiming UC and this could disincentive them from saving. For example, one participant, although enrolled into her workplace pension, was worried about reaching the Universal Credit savings limit of £6,000 through her pension savings.

“When you do try to get those savings up on Universal Credit, that’s when the government say ‘because you’ve got those savings you can use them’ not thinking you are getting ready for retirement.” (Below earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)[footnote 3]

Another participant felt penalised for saving into a pension whilst also struggling with reduced income in the short-term.

Others, conversely, recognised workplace pensions contributions as a safe place for income that would otherwise be capped under Universal Credit tapering rules. A single parent (below) described opting into a workplace pension solely to reduce her take-home salary so that she remained entitled to Universal Credit.

“Because I am a wee bit over the (UC) threshold, I was happy for them to take [pension contributions] because it meant the government wasn’t getting it.” (Below earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

More generally, participants claiming benefits described feeling trapped in low incomes. This included the perception that the only way to afford pension contributions was to increase their hours and therefore salary, but that would affect their eligibility for benefits and further reduce their take-home pay.

Workplace pension infrastructure

The default nature of AE inevitably meant that participants’ employment context and workplace pension infrastructure played a significant influence on their pension behaviour. The most obvious way this played out was people automatically being enrolled into their workplace pension. Employers are not obliged to enrol employees earning under £10,000 or who are under 22 years old, but some employers chose to do so. In some cases, employees claimed to only becoming aware of being enrolled when they spotted contributions in their payslip (see Chapter 4).

Beyond this, individuals’ pension behaviour could interact with other aspects of their employment context such as employment contract. This happened, for example, as priorities and the decision on what job was needed to meet these priorities, shifted from salary towards benefits. One participant contracted by an agency as a teaching assistant felt that her pension and job security was becoming more of a priority as she got older, so she decided to change jobs.

“I’d have been paid more if I’d stayed on with an agency, but I wanted to work with the council because I get the pension. Though it’s less money, the job is secure, and you get a pension.” (Above earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

There were concerns about the affordability of pensions for smaller employers. One participant working part-time for a small charity claimed not to have been offered a workplace pension because her employer couldn’t afford contributions[footnote 4]. Participants could feel particularly loyal towards smaller employers they had worked at for a long time. For example, one participant who opted out of a pension scheme along with a colleague had worked full time in a family-run hairdresser for over 18 years. Despite reassurances from the owner, she was worried about impact of the employer contributions on the small business and felt grateful to them for keeping her employed since she started as an apprentice.

“It’s a small business so employer contributions would mean the business would struggle. Business is slow and their bills are going up now. I’d feel bad about the owner having to contribute.” (Above earnings trigger, not saving into a workplace pension)

Participants also cited situations where employers had discouraged pension enrolment. For example, a participant who worked part-time for a local authority for over 11 years described being asked by her manager to consider the financial costs to the authority of having to make employer contributions. Whilst this pre-dates the introduction of auto-enrolment of pensions, the negative experience had a long term impact in that the participant remained opted out. It was only when the participant’s working hours had increased three years ago (and her salary met the AE threshold) that she was enrolled into the workplace pension scheme and she decided to stay in.

“I know now it was very wrong but one of my managers came up to me and said ‘are you sure you want to be in the pension because we have to match what you pay and we can’t financially do that’, and I was only young and I didn’t realise at the time that was very bad and they could get into a lot of trouble for that.” (Above earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

Chapter 4 draws on the key factors that underpin participants’ attitudes and behaviours towards, and experiences of, pensions and later life planning. Variations and similarities between those who are earning above and below the earnings trigger and those who have been automatically enrolled or decided to opt in are explored in further detail.

Chapter 4: Exploring differences in attitudes, behaviours and experiences of pension saving and later life planning

This chapter builds on an understanding of the key factors identified in Chapter 3 that underpin participants’ attitudes and behaviours towards, and experiences of, pensions and later life planning. It explores how these differ across the four groups engaged with through the research.

The chapter’s focus is on comparing the differences between individuals below and above the earnings trigger who are saving or not saving into a workplace pension, and assessing the variations between automatically enrolled lower earners and those who have decided to opt in.

Groups explored through the research

The research was structured primarily to explore the profiles and experiences of four groups defined by their annual earnings and whether or not they were saving into a workplace pension. These four groups were:

1. Those earning below the AE annual earnings trigger of £10,000 and not saving into a workplace pension (not auto enrolled)

2. Those earning below the trigger but currently saving into a workplace pension (“participating below the trigger”)

3. Those above the trigger but not saving into a workplace pension (“opted out”)

4. Those above the trigger and saving into a workplace pension (auto enrolled)

The main reason for this sampling approach was that the AE earnings trigger remains the primary policy lever available to DWP to increase or decrease participation in the workplace pension. For ease, each group is referred to by its number (e.g. Group ‘#’) and a brief description.

A summary of the overarching differences between each group’s drivers for saving or not saving into a pension is outlined in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Summary of participant differences based on drivers of pension saving behaviour

Below the earnings trigger

Group 1: Not auto enrolled

Active

- short-term budget priority

- workplace norms

Passive

- unaware of being able to opt in

- low awareness and engagement

Group 2: “Participating below trigger”

Active

- prompt from employer

- quality information

- saving prioritised /normalised

Passive

- legacy enrolled / auto enrolled

- lack of information to opt out

Not saving into a pension

Above the earnings trigger

Group 3: “Opted out”

Active

- short-term budget priority

- precarious roles

- financial shocks

Passive

- not informed

- “not AEd” by employer[footnote 5]

Saving into a pension

Group 4: Auto enrolled

Active

- value pensions

- part of saving behaviour

- affordable

Passive

- auto enrolled

Each of these four groups was made up of a range of types of participants, and key characteristics influencing attitudes and behaviour were found to cut across the groups. These characteristics affected members of each group in different ways, and interacted with one another to shape attitudes to pensions, and pension-saving behaviour.

Before exploring each of the four groups, it is worth reflecting on these common characteristics. The key factors that cut across the groups included their individual and household characteristics (age, gender, having a partner or children), their engagement with and attitudes to pensions and saving, and the stability of their work and earnings.

Individual and household characteristics: Younger workers and students working temporary jobs and contracts appeared in all groups. While research was qualitative and defined by strict quotas, low earners appeared more likely to be female, reflecting findings from the Living Wage Foundation using Office for National Statistics (ONS) survey data (Aziz & Richardson 2022)[footnote 6]. Single mothers with childcare responsibilities were present throughout groups, including those receiving benefits for children with disabilities. The groups also included immigrants whose earnings and job prospects were limited by their settled status or not speaking English as a first language, or where any spare income was used to support family members living overseas.

Engagement with and attitudes towards pensions and saving: As noted above, engagement with the topic was low across all groups. People struggled to recall details of their workplace pension scheme or the value of their pension if they were enrolled. Those sceptical about the value of pensions were found in all groups, not just those who had opted out of AE. Their views ranged from the perception that pensions would not adequately provide for them in later life, to a mistrust of employers and/or pension providers more generally. Similarly, those who valued pensions were found in all groups, even if they did not currently feel able to save into a pension or had a low understanding of the system and the ability to opt in or out. All groups included those with varied levels of financial confidence - the extent participants felt able to make good decisions with money.

Stability of work and earnings: Across all groups, those working in stable jobs were more likely to say they felt informed by their employer about pensions. Those working in precarious jobs (e.g. temporary, seasonal or gig-based contracts) described more ad hoc relationships with employers and poor communication about benefits, including pensions. For these participants, pension behaviour was more dependent on their employers in terms of quality of information received and whether they were nudged to engage with their pension. As explored in Chapter 3, current annual earnings could also be perceived as highly provisional by participants across the four groups. Younger people in particular were willing to delay considering pensions until they were in a more established career.

It is important to recognise the dynamic nature of the groups. Each contained subgroups defined by participants’ varied characteristics, circumstances, attitudes, and experiences, and these were liable to change over time. The differences and similarities within each group are considered below, followed by reasons for behaviour, reflections on comparisons between the groups. Note that these findings are based on qualitative research, which was designed to explore the groups in depth (through purposive sampling), rather than to measure prevalence of views and behaviours.

The four groups are explored in turn below, starting with those least engaged with their workplace pension (below the earnings trigger and not saving into a workplace pension) and finishing with those who are could be viewed as most ‘locked into’ pension saving (above the trigger and saving into a workplace pension). This allows comparison of groups with similar earnings but different pension behaviour and prioritises those most likely to be affected by any future changes to AE.

Group 1: Not auto enrolled (Below the earnings trigger, not saving into a pension)

Group 1: Not auto enrolled

Drivers of pension-saving behaviour

Active

- short-term budget priority

- workplace norms

Passive

- unaware of being able to opt in

- low awareness and engagement

The low earners who fell into this group were more likely than other groups to be in insecure or temporary work, and typically working part-time. They included young people and students, those balancing work with childcare responsibilities, and some older participants, typically in precarious jobs and feeling financially vulnerable.

Commonalities and differences in attitudes and experiences

Within this group, the main differences in pension attitudes and experiences were the result of age, participants’ perceived stability of role and whether they had a dual household income.

A key subgroup of this audience was younger people, who could be living in a rent-free or rent-reduced situation. Ranging from those who had just left school to others in their 30s, and spanning jobs from hospitality and childcare to working as a lifeguard, they were more likely to treat their current employment as a temporary ‘fill-in’ job. As a result, workplace pensions were often viewed as only relevant to a more established future career and did not allow for financial control. This was especially the case when current financial circumstances were challenging and balanced with studies.

As discussed in chapter 3, the workplace norms and employers of the part-time workers and students who were prevalent in this group also discouraged enrolment. This aligned with preconceptions that the decision to enrol should be delayed until a more secure and permanent future role. Those aged under 22, who would not have been automatically enrolled even if their earnings were above the trigger, had typically given the least thought to the topic.

“I don’t need a pension right now. I need the money. The pension can wait, but I hadn’t thought about what I’d be losing at all.’’ (Below earnings trigger, not saving into a workplace pension)

“Pensions are a lower gratification form of saving than others – you don’t get what you put in ‘til a really, really long time in the future and you may not even get it, so it’s very hard to motivate yourself. When you have a savings account you put the money in and you see exactly what you have. With a pension it Low Earners and workplace pension saving – a qualitative study goes off into the ether.” (Below earnings trigger, not saving into a workplace pension)

This group also included those whose pension behaviours were strongly influenced by the nature of their employment contracts and perceptions of low financial security. They were often in highly precarious roles, with little money to spare due to supporting families, often on one salary, and saw pensions as unaffordable (see reasons for not saving into a workplace pension, below). In contrast, others in this group were working part-time in more permanent and secure contracts, more often in dual income households. This second group included those not opposed to pensions but currently supported by a partner’s income who believed they could benefit in a similar way in later life through a higher earning partner’s pension. Responses suggested this view was a combination of self-justification after partners were auto-enrolled and they were not, and participants feeling contributions were more affordable for their partners, or their pension schemes more generous than their own. The group also included others planning to make life changes (e.g. to move overseas) who therefore felt pension saving could be a ‘waste’ in the short term.

Reasons for not saving into a workplace pension

As explained previously, if earning below £10,000, workers are not automatically enrolled into their workplace pension scheme but, if earning above £6,240, can opt in and their employers cannot refuse. While none of Group 1 (Not auto enrolled) had opted in, an active and confident decision not to opt in was rare. More often, participants claimed not to be aware of their right to opt in. Many were uncertain about whether they were currently saving into their workplace pension scheme, reflecting low levels of understanding and awareness about pensions more generally.

Those who had passively remained opted-out from their workplace pension claimed they had not been informed about the option to opt in by their employer, or may have ignored or missed information. As was explored in chapter 3, participants in this group also described employers advising against joining the scheme or telling employees they did not qualify (see case study 1, below); for example, due to the number of hours they worked.

Case study 1: Employer advised against joining the WPP due to employee not working enough hours

(Below earnings trigger, not saving into a workplace pension)

Claire, age 35, earns below the earnings trigger and does not save into a workplace pension. She lives with her husband and three young children in the countryside and works in two part-time merchandising roles while her husband works as a full-time carpenter. Claire’s part-time roles give her the necessary flexibility to look after her three children. But balancing work and childcare is an ongoing challenge, and she is unable to save.

Claire has never paid into a workplace pension. She was told that she doesn’t work enough hours to be eligible[footnote 7]. She is concerned about the risk of not having enough money to live on in retirement.

“If you’ve got a private pension, you’re lucky, and can live a great life. But if you haven’t got that private pension, then it’s going to be a struggle.”

During the interview, Claire realised that she would be eligible to opt in to her workplace pension. Claire felt frustrated by the lack of communication and information from her employer. She intended to speak to her employer about opting into the workplace pension in the future.

Among active decision-makers in Group 1 (Not auto enrolled) the decision not to opt in was typically the need to prioritise short-term budgeting, as discussed in chapter 3. Others discussed previous negative experiences of pensions, including employers changing providers or demanding higher, unaffordable, contributions of employees[footnote 8]. Some participants had previously been enrolled in a workplace pension but had opted out as their circumstances changed (for example, reducing their hours and pay) or as the impact of the rising cost of living made pensions feel unaffordable.

The few in this group with low trust in pensions had actively chosen not to opt in either because they felt pensions would be insufficient to support them in later life or mistrusted their employers or pension providers. This included people who described the idea of long-term income security as a ‘mirage’. Instead, they prioritised other forms of savings, such as investments, personal ISAs or reliance on a partner’s income.

“(Pensions) are like a fairytale for grown ups… Saving 50 years to benefit for 8 years is definitely not a good thing.” (Below earnings trigger, not saving into a workplace pension)

Case study 2: Opted out of workplace pension and prioritises alternative investments

(Below earnings trigger, not saving into a workplace pension)

Vasile, age 42, moved from Romania to the UK when he was 36 and now works an average of 8 hours per week in two roles at a university while studying for a degree. He recently opted out of the workplace pension scheme following an increase in required employee contributions from 5% to 10%, with employer contributions also rising to 10%. Vasile has a negative perception of pensions, particularly when comparing the length of contribution with the period he would benefit from it.

“It was now roughly 10% of my wages. It’s definitely too much! The university contributed more than 10%, it’s a really nice pension but for me it’s too much! They could pay three times more and I’d still opt out!”

Vasile has savings to sustain his lifestyle for three months and pays £10 per month into a Help to Buy ISA. But he is concerned that inflation will undermine his savings. As a result, he plans to start his own business soon which he predicts will be his financial safety net for retirement.

Group 2: “Participating below trigger” (Below the earnings trigger, saving into a pension)

Group 2: “Participating below trigger”

Drivers of pension-saving behaviour

Active

- prompt from employer

- quality information

- saving prioritised /normalised

Passive

- legacy enrolled / auto enrolled

- lack of information to opt out

Those who were enrolled in a workplace pension at this lower earnings level were a mixture of profiles and demographics, generally working one or more part time roles. They were largely similar to Group 1 (Not auto enrolled). However, young people were a smaller component of this group, with more relatively older participants balancing hours with childcare or moving from full-time to part-time roles. The group also included those who had returned to work after having children, and those historically supported by a second income who had made the decision to ‘catch up’ through pension saving before retirement.

Commonalities and differences in attitudes and experiences

Within the group, key differences in pension attitudes and experiences were associated with people’s perceived ability to save money and the priority they placed on saving generally, and whether they were in a dual income household.

The group shared a general lack of financial security or stability, experience of disruptive life events such as unplanned pregnancies, divorces, getting into debt, and struggled to financially support their children.

In comparison to those not enrolled, certain members of this group put more effort into saving and felt this was important. However, this was often not deemed possible or affordable. Despite everyone currently saving into a workplace pension, this group included people who felt generally unable to save in other areas of their life. Those who felt unable to save were typically receiving benefits and discussed the ‘poverty traps’ in the system and the drain of the cost-of-living crisis on their spending. For example, some participants believed they would earn less if they increased their working hours due to their benefits being reduced as a result. However, they could not increase their income from benefits so felt ‘trapped’ in their current financial state.

Those with young children also discussed being focused on short-term budgeting, delaying any longer form of personal or family saving (excluding pensions) until their children were older and more self-sufficient. As explored in chapter 3, saving toward a pension allowed some respondents to keep their earnings at a level that meant they retained some benefit payment under Universal Credit.

Those in this group who could afford to save (both generally and into a pension) were typically able to do so by taking a household (rather than individual) approach to saving as a result of a partner’s salary. Others felt secure and able to save from owning mortgaged property or not having to pay rent.

“Not having to think about that [paying rent] is massive. Before I got this job with the church that came with a house we lived nearby and had to pay £1200 a month for rent before bills. That was all of my income plus one third of my wife’s income!” (Below earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

Group 2 also contained people for whom saving was extremely important, even if this was challenging and they were only able to save up small amounts at a time. These individuals wanted to create a buffer for unknown circumstances, or performed ‘mental accounting’, allocating savings to specific purposes such as maintenance for their disabled child to survive on in adulthood. In a more practical sense, spending apps were also used to forecast spending for coming weeks and months.

“I’m a great believer that nothing is guaranteed in life. I could lose all my money tomorrow, something could happen and at least I’ve got something to fall back on if I need it.” (Below earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

“The only time I would actually consider [opting out] if I couldn’t afford food for my children.” (Below earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

Despite widespread confusion about pensions, these more committed savers were more likely to understand how their workplace pension operated and see it as one component within their wider savings strategies. As a result, they were also more likely than Group 1 (Not auto enrolled) to have made an active decision (in this case, to opt in). Personal life and financial values, often learned, were a motivator for members of this subgroup, with pension saving being viewed as a positive, ‘normal’ or socially desirable. Others justified being opted in by explaining that their contributions felt affordable and already accounted for in their daily spending.

Reasons for saving into a workplace pension

As with Group 1 (Not auto enrolled), many in this group did not recall making a decision about whether to opt into their workplace pension scheme. This reflected the low awareness and understanding across all groups, and that mechanisms exist that can lead to workers below the trigger being auto enrolled into a pension scheme. These include contractual enrolment and employers choosing for all employees to be auto enrolled, as well as examples explored below.

“I didn’t know that I could do that [opt in or opt out]. I think now, having just learnt that I can do that, I don’t think I would opt out. It seems like a vaguely sensible thing to do.” (Below earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

Workers who were passively enrolled included those who had been auto enrolled by their employer without being given (or simply not recalling) the opportunity to decline. They also included the ‘legacy enrolled’: those who had been auto enrolled when their earnings were above the trigger and remaining enrolled when their earnings drop below the trigger (see case study 3, below).

Case study 3: Passively remained in workplace pension after salary reduction

(Below earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

Orla lives with and cares for her 10-year-old daughter who has disabilities. Orla has been working for her brother’s law firm for the last 10 years. On average, she works around 16 hours per week to have enough time and flexibility for her daughter’s medical appointments. She also receives Child Benefit, Tax Credits and her daughter’s Disability Allowance.

Orla opted into a workplace pension when her salary was higher in the past and has remained in the scheme despite her income falling below the AE earnings trigger when she reduced her hours. She noticed the reduction in her salary when she first enrolled and adjusted spending based on this level. However, she has been saving into it long enough that she doesn’t notice it any more.

“If it was increased I’d notice it again, but would then adjust. It might have quite a big impact though the way things are going!”

Participants in this group appeared to be more likely than those earning higher salaries to have missed or not received information from employers telling them they could opt out. This could be the result of poorer quality workplace pension infrastructure from employers, as discussed in chapter 3. It could also be due to participants combining multiple jobs (and therefore multiple communications channels), or taking on temporary work or changes to their contract, for example reducing hours to cover childcare or study.

Those who had made an active decision to opt in typically described being prompted about the option by their employer. They were then either explicitly encouraged to opt in by their employer or had made an individual assessment about the value and affordability of doing so (see case study 4, below). In our small sample, this experience was less common than people claiming to have been auto enrolled either on their current or previous salary.

'’3% isn’t much - it makes no real difference to our home finances or saving for extras.” (Below earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

“[The annual pension statement] said there’s only seventeen thousand in my pension and I thought that’s not a great deal…I considered taking it out but decided against it because it’s still a lot of money[footnote 9].” (Below earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

Case study 4: Active decision to prioritise saving for retirement

(Below earnings trigger, saving into a workplace pension)

Asif works as an evening receptionist at a local college, lives with his wife and two children, and receives Universal Credit. Due to health problems and caring responsibilities for his mother, he is currently unable to work longer hours and struggles to save money.

He was automatically enrolled into a workplace pension at a previous full-time role. He opted into a workplace pension in his current role as he considers it an important thing to do, and he saw his father living off his pension first-hand. His faith also prohibits earning interest rates on other types of savings. He finds pensions complex but regards himself as financially responsible and his current financial contributions as manageable.

“I am very sensible. I am Asian. I have been brought up to be careful”

“It provides peace of mind. It is your hard-earned money, you benefit from it when you are not as strong.”

Group 3: “Opted out” (Above the earnings trigger, not saving into a pension)

Group 3: “Opted out”

Drivers of pension-saving behaviour