Manchester New Moston Congregation of Jehovah’s Witnesses

Published 26 July 2017

Applies to England and Wales

A statement of the results of an inquiry into Manchester New Moston Congregation of Jehovah’s Witnesses (registered charity number 1065201) (‘the charity’).

The charity

Manchester New Moston Congregation of Jehovah’s Witnesses is an unincorporated charitable association. It was registered with the Charity Commission (‘the Commission’) on 31 October 1997. It is governed by a constitution dated 30 May 1997.

The objects of the charity are ‘the practice and advancement of Christianity founded on the Holy Bible, as understood by the denomination of Christians known as Jehovah’s Witnesses, including the preaching of the good news of God’s kingdom by Jesus Christ within the congregation area and the holding of meetings’.

Background

The organisation of Jehovah’s Witnesses charities in England and Wales

The charity is one of approximately 1,350 charities registered in England and Wales that are linked to Jehovah’s Witnesses. Its congregation meets at a place of worship called a Kingdom Hall. The congregation is supervised spiritually by a body of elders. Provided they meet the legal requirements, the elders are also the charity trustees of the charity.

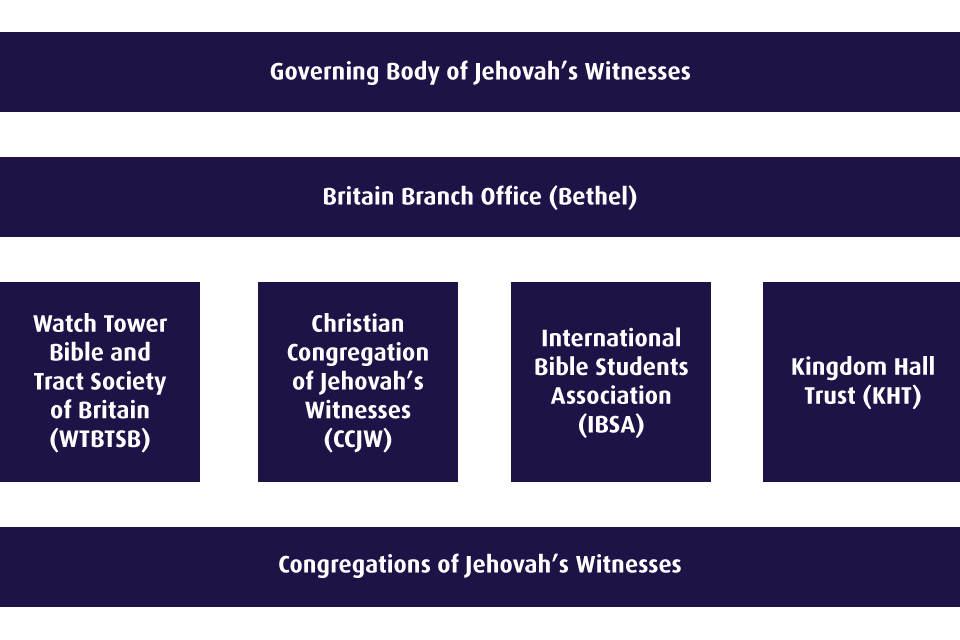

The congregation is one of a ‘circuit’ of about 20 local congregations of Jehovah’s Witnesses. Congregations receive periodic visits from traveling elders known as circuit overseers. The Governing Body of Jehovah’s Witnesses, which is based in Warwick, New York, USA, arranges for the appointment of circuit overseers.

The religious activities of Jehovah’s Witnesses in the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland are overseen by a committee of elders called the ‘Britain Branch Committee’. Its members are appointed by the Governing Body of Jehovah’s Witnesses.

The Britain Branch Committee provides religious and secular organisation for Jehovah’s Witnesses in the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland. It also oversees and guides the work of 3 registered charities and an unincorporated association. One of the charities is called Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Britain (‘WTBTSB’), registered charity 1077961. WTBTSB undertakes a number of functions which include printing and distributing religious literature. WTBTSB also has a legal department which the elders of congregations are instructed to contact for advice in certain circumstances.

The second charity is the International Bible Students Association (IBSA), registered charity 216647. The main functions carried out by this organisation are the purchase and distribution of religious literature, arranging conventions for bible education and providing financial assistance to legal entities of Jehovah’s Witnesses.

The third charity is the Kingdom Hall Trust (‘KHT’), registered charity 275946. The KHT acts as a custodian trustee to several hundred properties which are mainly Kingdom Halls.

The unincorporated association is called the Christian Congregation of Jehovah’s Witnesses (‘CCJW’). CCJW provides ecclesiastical and spiritual direction to the congregations and individual Jehovah’s Witnesses. This is done in a number of ways including ‘Letters to All Bodies of Elders’. The CCJW also runs a service desk that can be contacted by elders or other Jehovah’s Witnesses for spiritual advice.

Diagram of Jehovah’s Witnesses organisational structure

Diagram of Jehovah’s Witnesses organisational structure

The Commission opened a separate statutory inquiry into WTBTSB on 27 May 2014. The scope of that inquiry includes the creation, development, substance and implementation of the safeguarding policy used by Jehovah’s Witnesses congregation charities in England and Wales, as well as the safeguarding advice provided to those congregation charities.

Background to the issues under investigation

In August 2012, the Commission was notified that one of the charity’s trustees, Mr Jonathan Rose, was appearing in court charged with sexual offences. The charges related to events which occurred around 2002, before he took up trusteeship. The Commission sought information from the trustees and gave regulatory advice to the trustees regarding their safeguarding responsibilities, closing its initial operational case based on the information they had provided. The trustee resigned during the course of this engagement[footnote 1].

In October 2013, Mr Rose, was convicted of 2 counts of indecent assault and sentenced to 9 months’ imprisonment; he was also made subject to a sexual offences prevention order and required to sign the sex offenders’ register for life.

In November 2013, the Commission became aware that it had been alleged during Mr Rose’s trial that the charity’s trustees had knowledge about a complaint of a similar nature about Mr Rose made in 1995. This had not been mentioned to the Commission during the first operational case. The Commission opened a second operational case in December 2013.

As part of this case, the Commission met with 5 of the charity’s trustees on 20 March 2014 to discuss its regulatory concerns.

Following that meeting, the Commission received further information which stated that:

- following Jonathan Rose’s convictions, the elders had held internal `disfellowshipping’ proceedings against Jonathan Rose, which involved his victims, who were now adults, attending the congregation’s hall where they, and another woman who had made allegations of historic child sexual abuse against Jonathan Rose, were questioned further about the abuse

- this process included a series of meetings, presided over by elders of the charity, and was not concluded until after Jonathan Rose was released from prison

- during at least one of these meetings, Jonathan Rose was able to directly question the women about the allegations against him

The Commission wrote to the charity and to WTBTSB on 29 April 2014 asking for further information about these meetings and other matters in connection with Jonathan Rose’s involvement in the charity. The charity and WTBTSB responded promptly.

Issues under investigation by the inquiry

On 30 May 2014, based on the information it had received, the Commission opened a statutory inquiry into the charity under section 46 of the Charities Act 2011. The scope of the statutory inquiry was to investigate:

- the charity’s handling of safeguarding matters, including its safeguarding policy, procedures and practice

- how the charity dealt with the risks to the charity and its beneficiaries, including the application of its safeguarding policy and procedures and any related policies and procedures, particularly as regards the conviction and release of a former trustee

- the administration, governance and management of the charity by the trustees and whether or not the trustees of the charity have complied with and fulfilled their duties and responsibilities as trustees under charity law

The inquiry into the charity closes with the publication of this report.

The Commission’s role in safeguarding issues and charity trustees’ duties

The Commission has an important regulatory role in ensuring that trustees comply with their legal duties and responsibilities as trustees in managing and administering their charity. In the context of safeguarding issues, the Commission has a very specific regulatory role which is focused on the conduct of the trustees and the steps they take to protect the charity and its beneficiaries. The Commission’s safeguarding work is often part of a much wider investigation involving or being led by other agencies. The Commission is not responsible for dealing with incidents of actual abuse and it does not administer safeguarding legislation. It does not prosecute or bring criminal proceedings, although it can and does refer any concerns it has to the police, local authorities and the Disclosure and Barring Service which each have particular statutory functions.

The Commission’s aim is to ensure that charities that work with or provide services to vulnerable beneficiaries take reasonable steps to protect them from harm and minimise the risk of abuse. It may consider any failure to do so as misconduct and/or mismanagement in the administration of the charity.

The Commission’s published guidance on its regulatory role and its expectations of charities and trustees on safeguarding is available on GOV.UK. This includes lists of essential elements of a child protection policy and for child protection procedures and systems.

Conduct of the inquiry and related litigation

The conduct and length of the inquiry has been significantly affected by litigation initiated by the charity’s trustees. This commenced in July 2014, when the trustees applied to the First-tier Tribunal (Charity) (‘Tribunal’) for a review of the Commission’s decision to open the inquiry, under section 321 of the Charities Act 2011. The Tribunal upheld the Commission’s decision to open the inquiry, in a decision dated 9 April 2015 (updated 22 April 2015). The charity’s trustees appealed this decision, and 2 related procedural decisions, in a hearing of the Upper Tribunal in March 2017. All grounds for the appeal were dismissed by the Upper Tribunal in a decision dated 4 April 2017, which upheld the inquiry.

The trustees of the charity engaged with the Commission during its regulatory case, but, acting on legal advice, declined to engage with the Commission following the opening of its inquiry. Given the seriousness of the regulatory concerns, and despite the ongoing legal proceedings, the Commission continued to gather the information it would need to assess the regulatory concerns, whether as part of an inquiry or not. The inquiry has been conducted and completed based on information provided by the trustees including in the legal proceedings and information from other relevant sources.

Findings

This section describes the findings of the inquiry, in accordance with its scope set out in ‘Issues under investigation by the inquiry’.

The charity’s handling of safeguarding matters, including its safeguarding policy, procedures and practice

The inquiry established that in common with other charities linked to Jehovah’s Witnesses in England and Wales, the charity adopted a ‘Child Safeguarding Policy’ in 2010. This Child Safeguarding Policy was developed and implemented by WTBTSB following previous regulatory intervention by the Commission. The policy received minor revisions in 2011, 2012 and 2013.

The inquiry found that the charity’s Child Safeguarding Policy states that safeguarding risks would be managed with reference to ‘the long-standing and widely published religious principles of Jehovah’s Witnesses’ (Child Safeguarding Policy, policy statement).

These procedures are common to all Jehovah’s Witness congregation charities in England and Wales, and are contained in a number of publications including a confidential manual for Elders called ‘Shepherd the Flock of God’. The manual is supplemented from time to time by confidential ‘Letters to All Bodies of Elders’ issued by the Britain Branch Committee or on its behalf.

On 1 August 2016, CCJW issued a ‘Letter to All Bodies of Elders’, including to the charity’s trustees that made changes to how allegations of child sexual abuse are dealt with through these procedures.

A revised Child Safeguarding Policy was launched in January 2017. The new policy applies to all Jehovah’s Witness congregations in the UK and Ireland, including the charity, and is monitored for compliance by the Britain Branch Committee.

This inquiry has assessed how the charity applied its Child Safeguarding Policy and related procedures in dealing with the risks to the charity and its beneficiaries presented by the conviction and release of its former trustee, Jonathan Rose. The Commission’s findings on these points are set out in the following subsections.

A more general assessment of the Child Safeguarding Policy and the related procedures is being carried out as part of the Commission’s separate, but related, inquiry into WTBTSB.

How the charity dealt with the risks to the charity and its beneficiaries, including the application of its safeguarding policy and procedures and any related policies and procedures, particularly as regards the conviction and release of a former trustee

The inquiry examined 3 areas in order to assess how the charity dealt with the risks to the charity and its beneficiaries arising from Mr Rose’s conviction and release. The areas are:

- how the charity dealt in 2012 with an allegation by an individual (‘Person A’) of non-recent child sexual abuse by Jonathan Rose and Mr Rose’s subsequent arrest and conviction for sexual offences against both Person A and another victim (‘Person C’)

- how the charity dealt with complaints made by another individual (‘Person B’) in 2012 and 2013 about the charity’s handling of an earlier allegation of child sexual abuse against Jonathan Rose

- how the charity dealt with the risks posed by Jonathan Rose following the initial allegations of abuse, during the criminal proceedings in 2013 and after his release from prison in 2014

How the charity dealt with an allegation of child sexual abuse made by Person A in 2012

The inquiry established that in the week beginning 13 February 2012, the trustees received an allegation of non-recent child sex abuse against Jonathan Rose. The victim was Person A who had been a beneficiary of the charity as a child in the 1990s. At the time the allegation was made, Jonathan Rose was serving as an elder and charity trustee of the charity, although not at the time of the alleged incident.

The charity’s response to Person A’s allegation was explained in a witness statement filed in the Tribunal litigation by one of the charity’s trustees. The trustee stated that in response to Person A’s allegation, ‘2 elders spoke to Mr Rose, and another 2 elders to the victim’. The trustee also stated that the charity’s trustees contacted WTBTSB, to seek legal advice about the application of the Child Safeguarding Policy, and CCJW to seek spiritual advice.

The trustees subsequently informed the inquiry that the chair of the trustees and one other trustee contacted WTBTSB and CCJW on 21 February 2012 for advice following which a decision was made to remove Mr Rose from all teaching and pastoral responsibilities. The trustees told the inquiry that the chair of the trustees informed Mr Rose of this decision.

The inquiry noted that these steps are in accordance with the charity’s Child Safeguarding Policy and related procedures. However, no contemporaneous record was made of the decision to remove Mr Rose from teaching and pastoral duties and there is no evidence that a formal action plan was put in place to enforce this decision. The inquiry has also been informed that both the chair and the other trustee who took the lead in dealing with the allegation of sexual abuse were close friends of Mr Rose, raising the prospect of conflicts of loyalty (see later in the report).

Jonathan Rose was arrested by Greater Manchester Police on 10 April 2012. The trustees informed the inquiry that they contacted CCJW and WTBTSB for advice again on this date.

The elders of the charity met on 23 April 2012, including Mr Rose who remained a trustee at that time. According to the minutes of their meeting, Mr Rose left the meeting and the following was considered:

‘REVIEW ADVICE RECEIVED IN RELATION TO BRO ROSE. Bro Rose left the meeting. We reviewed the evidence we have heard. Bro Rose vehemently denies the charges made by [Person A]. We therefore have just one word against another. We sought advice from the umbrella charity Watchtower [sic] Bible and Tract Society and based on this we agreed that in view of the evidence that we view Bro Rose as innocent until such time as there is evidence to prove otherwise. In view of the serious allegations [we agreed] that Bro Rose would not handle platform items or be involved in pastoral care until matters are resolved.’

The trustees informed the inquiry that they sought further advice from CCJW in July 2012 at which point they decided that ‘Mr Rose would not be given any assignments in the congregation, including assisting with roving and platform microphones, literature and magazine counters, attendants and car park duty’.

In the summer of 2012, Jonathan Rose was charged with indecent assault of Person A. He appeared at Manchester Crown Court for a pre-trial hearing on 10 August 2012.

That day, the Commission wrote to the charity. It requested further information about Mr Rose, his role, what steps the trustees were taking to identify and manage safeguarding risk and whether there was a safeguarding policy. It also sought clarification on whether the trustees had reported the matter to the police.

The trustees responded on 13 August 2012. They explained that ‘following direction from the umbrella charity, Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Britain, the trustees decided not to use Jonathan Rose in any assignments representing the congregation on the public platform or in a pastoral or teaching capacity within the congregation’. The trustees enclosed a copy of the Child Safeguarding Policy.

The Commission responded the next day, on 14 August 2012. It asked if Jonathan Rose had been acting in his capacity as a trustee at the times when he was alleged to have committed the indecent assaults. It also asked what steps the trustees were taking to monitor Jonathan Rose and what his role was going to be in the charity. The Commission requested clarification of the timescales between the trustees being made aware of the allegation and imposing restrictions on Jonathan Rose.

On 16 August 2012, the trustees responded to explain that the incidents were alleged to have happened approximately 10 years previously - before Jonathan Rose was appointed an elder and a trustee in 2009. The trustees provided further detail regarding how they were managing the safeguarding risk that he might pose to beneficiaries of the charity, which included ensuring that all trustees were aware of the allegation and ensuring that he did not have access to vulnerable beneficiaries.

On 31 August 2012, the Commission replied to state that it considered that the trustees were currently taking appropriate steps to restrict the activities of Jonathan Rose by deciding not to use Jonathan Rose in any assignments representing the congregation on the public platform or in a pastoral or teaching capacity within the congregation. The Commission nevertheless suggested that he should consider resigning as a trustee and that if he did not, the other trustees should consider suspending or removing him. The Commission advised that the trustees review their safeguarding policies and procedures.

Further information was requested regarding risk management between the date Person A made an allegation of child sexual abuse to the elders in February 2012 and their meeting to discuss the matter on 23 April 2012.

On 7 September 2012, the trustees informed the Commission that Jonathan Rose had resigned as an elder of the congregation and as a charity trustee of the charity. The trustees also replied that they had handled the matter in accordance with their Child Safeguarding Policy. They said that in the period between being made aware of the allegation and taking action, ‘the congregation did not conduct any Regulated Activity[footnote 2] Relating to Children. Accordingly, Mr Rose took part in no any [sic] such activity. Whilst with members of the congregation Mr Rose was not on his own with any vulnerable beneficiaries’. The trustees also stated, ‘the alleged incident occurred some 10 years ago and the complainant is now an adult. We have no knowledge of any other allegations of a similar nature being made against Mr Rose’.

On 28 September 2012, the Commission informed the charity that it was satisfied based on the information provided that ‘the trustees have taken appropriate steps to safeguard the charity’s vulnerable beneficiaries, and have put appropriate mechanisms in place to oversee/supervise Mr Rose’s limited activity within the charity. The trustees have acted responsibly in protecting the charity’s beneficiaries and also the charity’s reputation’.

However, during the course of the inquiry the Commission received evidence that Mr Rose continued to perform activities which the trustees, in July 2012, had decided to restrict him from. These included performing administrative duties during a large assembly in December 2012, hosting an adult who attended a 2 week training course in August 2013 and playing a support role during the training course.

The trustees informed the inquiry that Mr Rose had not been assigned any duties during the large assembly in December but rather carried them out of his own volition. However, the trustees did not report taking any reactive steps to prevent further breaches of the restrictions by Mr Rose such as holding a meeting with him to ensure that he understood the restrictions placed on his activities and the importance of compliance with the restrictions.

The trustees also informed the inquiry that there had been an initial proposal for a young adult male to stay with Mr Rose’s family during the pioneer school in August 2013. However, the trustees had raised concerns about this with the chair of the trustees and had agreed to house an older male with Mr Roses’ family instead. Whilst the trustees considered the immediate potential risk to the student being housed with Mr Rose they did not inform the inquiry why they considered that hosting an attendee of the pioneer school did not fall within the types of positions of responsibility that they had decided to restrict him from in February and July 2012.

The inquiry’s findings on the trustees’ handling of Person A’s allegation in 2012

The inquiry found that the charity trustees took some positive steps to deal with Person A’s allegation in 2012. These steps were consistent with the charity’s relevant policy and procedures at the time, in particular the Child Safeguarding Policy, ‘Shepherd the Flock of God’ and a Letter to All Bodies of Elders dated 1 October 2012. In particular, the trustees:

- carried out an investigation by speaking to both Person A and Mr Rose

- contacted WTBTSB and CCJW to seek specialist advice on the handling of the allegation and following Mr Rose’s arrest

- took a decision in February and July 2012 to put in place interim restrictions aimed at protecting the charity’s beneficiaries from the risks presented by Mr Rose following the allegations, his arrest and pending his trial

However, whilst the trustees took advice from WTBTSB and CCJW once they became aware of the allegations the inquiry identified the following concerns regarding the trustees’ handling of Person A’s allegations:

- there is no contemporaneous record of the initial decision to remove Mr Rose from teaching and pastoral responsibilities in February 2012 or the decision to introduce further restrictions in July 2012 - furthermore, there is no evidence of a formal action plan assigning responsibilities for enforcing this decision or for regular review of it - Mr Rose subsequently carried out activities that appear to fall within the types of activities he was restricted which indicates that this plan was not fully enforced

- the inquiry also found that there is no evidence that the trustees considered any potential conflicts of loyalty when dealing with the allegation of abuse - the inquiry was informed that at least 2 of the trustees involved in dealing with the allegation were close friends of Mr Rose - consideration should have been given as to whether their friendship could, or could be seen to, interfere with the trustees’ ability to deal with the allegations only in the best interests of the charity - once any conflicts of loyalty were identified the trustees had a duty to prevent them affecting the decision making process - the trustees should also have made a written record of how these conflicts were identified and dealt with

The inquiry also found that:

- the charity did not commence internal misconduct proceedings against Mr Rose as a result of the allegation made by Person A in February 2012

- the trustees informed the Commission on 7 September 2012 that they had no knowledge of any other allegations of a similar nature being made against Mr Rose - however, as explained below, an earlier allegation had been made by Person B

These points will be addressed in further detail in later sections of the inquiry report.

The inquiry found that the trustees of the charity did not report the allegation of child sexual abuse to the police or to other authorities. Nor did it report the matter as a serious incident to the Commission. Once again there is no written record of how these decisions were made and what risks were considered. Whilst the allegation made was historic in nature and there was no suggestion that Person A was still at risk of abuse, this did not mean that Mr Rose did not represent a potential ongoing risk to other members of the congregation. The trustees should have clearly recorded their reasons for not reporting the allegation to the police both to ensure rigour in their decision making process and also to have evidence of this rigour should the decision be challenged at a later date.

How the charity dealt with complaints made by Person B in 2012 and 2013

Person B was a child beneficiary of the charity in the 1990s. She and her family were members of the charity. She originally made an allegation of sexual abuse against Jonathan Rose in April 1993. She has informed the inquiry that this allegation was immediately reported to the then elders (and trustees) of the charity, which included the father of Jonathan Rose and the same chair of the trustees and trustee that went on to take the lead after allegations were made by Person A (who the inquiry was informed were close friends with Mr Rose).

Person B also, ultimately, reported the allegation to the police. Jonathan Rose was arrested, charged and stood trial in 1994 for the alleged sexual abuse. Mr Rose was acquitted at trial.

Person B explained to the inquiry that she wanted her experiences to be used to assist with the investigation into the handling of Person A’s allegations rather than for her own experiences to be investigated in isolation. She was concerned that similar mistakes were made by the trustees when dealing with her allegations and those of Person A’s and wanted to prevent such mistakes being made in the future.

After Person B learned of the arrest and charges brought against Jonathan Rose in September 2012 she began to seek advice and guidance from elders of a neighbouring congregation of Jehovah’s Witnesses. These elders then arranged for her to meet the current circuit overseer.

Person B gave evidence to the inquiry that the circuit overseer apologised to her for the way she had been treated after making the allegations in the 1990s and spoke to her about correspondence that had passed between the elders of the charity and WTBTSB. When referring WTBTSB to the allegation that had been made against Jonathan Rose by Person A the elders said nothing about the allegation made by Person B against him in 1993. Person B was therefore asked to repeat her account, this time to elders from the neighbouring congregation and confirm that the allegation had never been withdrawn. She was asked to sign a written statement and she did so. This was counter-signed by the elders of the neighbouring congregation.

On 23 September 2012, on the instruction of the circuit overseer, Person B and 3 elders of the neighbouring congregation wrote to CCJW to outline their concerns about how the elders of the charity had dealt with Jonathan Rose following Person A’s allegations. This appears to be a reference to what is sometimes referred to by those outside the religion as the ‘two-witness rule’. The scriptural rule of evidence adhered to by Jehovah’s Witnesses is that there must be at least 2 eyewitnesses to the alleged wrongdoing if it is denied[footnote 3]. The letter asked, ‘is [Person B’s] allegation being taken into account when considering this new allegation?’. This letter was copied to the elders of the charity.

On 26 October 2012, the elders of the charity (including the same chair of the trustees who had dealt with the original allegations in the 1990s) wrote to CCJW. They described Person B as having ‘a history of being economical with the truth and seeking to cause trouble and dissention’ (Person B confirmed that she has never been subject to formal or informal disciplinary action by elders from any congregation). They referred to ‘Shepherd the Flock of God’. They added, ‘when [Person B] accused Jonathan [Rose] of wrongdoing he was 19 years old and she was 15, we did not view this as child abuse but as a matter between 2 teenagers’. The trustees referred to the acquittal of Mr Rose. They concluded, ‘in our view the alleged incidents are not the same kind of wrongdoing, and as we do not view [Person B] as a reliable witness, we therefore would not wish to use her testimony. We do not believe that there are any grounds to form a judicial committee at this time … In addition the court proceedings and bail conditions prevent us arranging a meeting with all concerned parties to discuss matters’. The letter was signed by 3 of the charity’s then trustees, including one of the trustees who had dealt with the original allegation made by Person B in the early 1990s.

Person B stayed in touch with the elders from the neighbouring congregation and a person she thought was representing WTBTSB, ‘Representative A’[footnote 4]. She was told that, at the request of the circuit overseer, the elders of the neighbouring congregation had attended a meeting with elders of the charity to discuss a judicial committee to consider Jonathan Rose. Person B was told that the elders of the charity had expressed dissatisfaction with the involvement of elders from a neighbouring congregation and did not want to subject Jonathan Rose to a judicial committee. She was further told that following this meeting all the elders of the neighbouring congregation had written to CCJW to recommend that the elders of the charity should not be responsible for Jonathan Rose’s disciplinary as they were not impartial. Person B explained to the inquiry that Representative A subsequently told her that they considered that the elders of the charity had a strong bias in favour of Jonathan Rose and they should not be involved in further handling the case.

Person B informed the inquiry that she spoke to Representative A on 13 November 2012. She states that the Representative A advised her that they wanted the conduct of the charity trustees to be investigated. He said that they would not be able to act unless she submitted a written complaint, which he asked her to send them. She received assurances that her complaint would be formally investigated.

Person B wrote to CCJW on 21 January 2013[footnote 5]. She made a formal complaint about the handling of the second allegation of child sexual abuse by Person A by the elders of the charity. Among other complaints, she expressed her concern that the elders were unable to identify non-consensual sexual activity between an adult and a child as child sexual abuse. She was also concerned that the elders had concluded that her allegation was so different from that of Person A that there was not ‘the same kind of wrongdoing’, and that the elders had not acted promptly when the allegation was made against Mr Rose by Person A in 2012. She further raised concerns about bias shown by the elders towards Mr Rose.

Person B confirmed many of the other elders and individuals from WTBTSB who were involved in the handling of her case acted with kindness and compassion. Elders, circuit and district overseers and trustees from WTBTSB who were involved in the handling of the case have since offered her unreserved apologies. She has also reported to the inquiry that the elders of the charity have also offered unreserved apologies but they have only been prepared to offer these via a third party; they have not been prepared to apologise in person or in public.

The inquiry’s findings on the trustees’ handling of Person B’s complaints in 2012 and 2013

The inquiry found that Person B initially contacted the charity’s trustees in the early 1990s and made an allegation of sexual abuse against Jonathan Rose. Mr Rose stood trial for this allegation and was acquitted. The inquiry makes no further findings regarding the complaints made by Person B in the 1990s or the handling of those complaints by the trustees at the time. As previously mentioned Person B gave evidence to the inquiry to assist with the investigation of the handling of Person A’s abuse and not to have the charity’s actions regarding her allegations investigated in isolation.

However, the inquiry had concerns about the trustees’ handling of Person B’s complaints in 2012 and 2013 from a safeguarding perspective. In particular, the inquiry found that:

- the trustees failed to demonstrate a sufficient understanding of child sex abuse in that they wrote of Person B’s allegation, ‘we did not view this as child abuse but as a matter between 2 teenagers’

- the trustees’ criticism of Person B as a person with ‘a history of being economical with the truth and seeking to cause trouble and dissention’ was not a sensitive and measured way of dealing with complaints regarding the handling of child sexual abuse allegations - as previously mentioned, Person B confirmed that she has never been subject to formal or informal disciplinary action by elders from any congregation

In this regard, the inquiry noted that the charity’s procedures provided specific counsel for elders working with survivors of child sex abuse, advising: ‘those who as children were abused, sexually or otherwise, many times grow up to be adults with emotional scars. They are in need of much loving attention. Thus, you will want to be conscious of treating such ones with thoughtfulness, tenderness, and kindness’ (emphasis in original, ‘Shepherd the Flock of God’, p53). While acknowledging that Mr Rose had been acquitted at trial of sexually abusing Person B, the inquiry considered that the trustees ought to have had regard to this guidance when commenting on Person B’s character and the motivation behind her complaints in 2012 and 2013 to the branch office and to have dealt with the complaints with greater ‘thoughtfulness, tenderness, and kindness’.

In addition, the inquiry established that the trustees of the charity declined, in October 2012, to form a judicial committee in order to investigate Mr Rose’s conduct under the charity’s procedures. This appears to have been based on a belief that the allegations made by Person B were not sufficiently similar to those made by Person A to satisfy the ‘two-witness’ rule. Representatives of WTBTSB and CCJW told the inquiry that judicial committees are not used to manage the safeguarding risk presented by an alleged child sex offender, rather it is a religious procedure used to keep the congregation ‘morally and spiritually clean’. However, the inquiry’s view is that, on this occasion, the judicial committee process operated as a key mechanism for the charity to manage the safeguarding risks presented by Mr Rose an alleged sex offender. A judicial committee, which may result in disfellowshipping, is the only procedure available to the trustees to exclude completely from the charity a person judged to be a risk to the beneficiaries. There is no equivalent secular procedure available to the trustees to investigate wrongdoing and exclude people from the charity and for this reason the inquiry considers it operated in this instance as a part of the charity’s safeguarding procedures.

As the ‘judicial committee’ procedure is considered by the inquiry to have operated as a key mechanism relied upon by the charity to manage the safeguarding risks presented by Mr Rose, the trustees’ refusal to commence judicial committee proceedings in October 2012 in response to Person B’s complaints potentially put the charity’s beneficiaries at risk.

How the charity dealt with the risks posed by Jonathan Rose during the criminal proceedings in 2013 and following his release from prison in 2014

On 25 January 2013, Mr Rose was further arrested by Greater Manchester Police after an allegation of non-recent child sex abuse was made about him by a third witness, Person C. Person C had been a beneficiary of the charity as a child in the 1990s. The inquiry found no contemporaneous evidence that the trustees had formally reviewed the risks to the charity following this further arrest or reconsidered the interim restrictions placed on Mr Rose in February 2012 and July 2012. During the course of the inquiry a trustee, ‘Trustee A’ made a statutory declaration that after Mr Rose’s arrest the elders immediately contacted WTBTSB and CCJW and considered that the safeguarding measures in place were proportionate to any risk posed by Mr Rose. The trustee explains in his statutory declaration that the main reasons the trustees considered that the safeguarding measures were proportionate were that Mr Rose had no unsupervised contact with children when he attended the Kingdom Hall, he no longer served as an elder, had no teaching or pastoral responsibilities and had no restriction placed on his participation in the congregation by the police or courts. However, as previously mentioned, the inquiry found evidence that the restrictions placed on Mr Rose’s activities were not fully enforced as there is no evidence that any action was taken after he performed administrative duties at the large assembly in December 2012.

In the autumn of 2013, Jonathan Rose stood trial for the indecent assaults of Person A and Person C. Person B also gave evidence against him. The jury found him guilty of the indecent assaults of Person A and Person C. He was granted bail for 6 weeks prior to sentencing on 30 October 2013.

In the 6 weeks between his conviction and his sentencing Jonathan Rose was not held in custody. The inquiry found no contemporaneous evidence that the trustees had reviewed the risks to the charity following Mr Rose’s conviction and pending his sentencing or reconsidered the interim restrictions placed on Mr Rose. Trustee A explains, in his statutory declaration provided during the inquiry, that the trustees updated CCJW following Mr Rose’s conviction and once again were satisfied that the safeguarding measures in place were proportionate to any risks posed by Mr Rose. Trustee A did not mention whether any consideration was given to the fact that Mr Rose had hosted an adult during the pioneer school shortly before his trial when the trustees reviewed the safeguarding measures at this point.

The inquiry understands that elders from other congregations, independent of the trustees, Jonathan Rose and Persons A, B and C, met individually with and interviewed Persons A, B and C. A judicial committee was then formed comprising 4 elders from other congregations who were also independent of the trustees, Jonathan Rose and Persons A, B and C. Person A, B and C were not required to encounter Jonathan Rose. The committee decided to disfellowship Jonathan Rose on 22 October 2013.

On 29 October 2013, Jonathan Rose exercised his right to appeal the decision to disfellowship him under the relevant ‘appeal committee’ procedures.

On 30 October 2013, Jonathan Rose was sentenced to 9 months’ imprisonment; he was also made subject to a sexual offences prevention order and required to sign the sex offenders’ register for life.

The inquiry found that an appeal committee, comprised of 4 independent elders, met with Person A, Person B and Person C and attempted to meet with Jonathan Rose in prison, but he refused. The appeal committee therefore decided to suspend its work until it could meet with him after his release.

Jonathan Rose was released from prison on 14 March 2014. The inquiry was informed that he attended a service at the charity’s Kingdom Hall on 16 March 2014. The inquiry also established that the appeal committee resumed its work with guidance and advice from WTBTSB and CCJW.

The Commission met with trustees of the charity on 20 March 2014. The trustees attending the meeting included 3 trustees who had dealt with Person B’s original allegation in the early 1990s.

There are 2 sets of minutes of this meeting: one prepared by the Commission, the other by the charity. The meeting minutes diverge in several respects. However, both the Commission’s and the charity’s minutes agree that:

- the trustees produced and referred to a copy of their latest ‘Child Safeguarding Policy’ (2013 version)

- the trustees did not disclose to the Commission at the meeting that the appeal committee had resumed its work or that Jonathan Rose had attended a service at the Kingdom Hall

The inquiry established that on 28 March 2014, the appeal committee decided to hold a series of face-to-face meetings at the Kingdom Hall involving Jonathan Rose and, in turn, Person A, Person B and Person C. These meetings were scheduled to take place on 2 April 2014. Person B told the inquiry that the chair of the appeal committee told her that if she and the other witnesses did not attend, no action would be taken against Jonathan Rose. Person B stated that the chair also said that the appeal committee would not consider the testimonies the witnesses had provided at court or to the judicial committee (ie the earlier stage of the internal proceedings). Person B states that the chair further said that if only one of the 3 witnesses turned up, because of the two-witness rule, once again, no action would be taken against Jonathan Rose.

The inquiry was told by the chair of the appeal committee that he has no recollection of telling Person B that no action would be taken against Jonathan Rose if she did not attend the appeal and face Mr Rose. The chair also stated that he informed Person B the appeal committee would simply use the written statement she had already provided to the appeal committee if she chose not to attend the meeting. However, based on evidence received, it is the inquiry’s view that the victims were given the strong impression that if they did not attend the appeal it was unlikely that any action would be taken against Mr Rose.

Person B spoke to Representative A on the telephone shortly after this conversation with the chair of the appeal committee and reported that victims were being told that if they not attend the appeal no action would be taken against Mr Rose. Representative A told her that it was important that those involved face their abuser in order to establish the truth[footnote 6].

The inquiry established that, on 2 April 2014, the face-to-face meetings went ahead as scheduled. The meetings were presided over by 4 members of the appeal committee, which did not include elders of the charity. Three members of the original judicial committee were present as observers and did not participate. Also in attendance was a former elder of the congregation who had been involved with Person B’s allegations in the early 1990s. He was not a member of the committee. He had however come to support and sit with Jonathan Rose. Person B was distressed by his presence and complained; she said she had made a formal complaint about him to WTBTSB - which was still unresolved. The committee asked him to leave.

The inquiry has evidence that the meetings lasted for more than 3 hours and heard separate testimonies from Person A, Person B and Person C. The witnesses were asked inappropriate questions by both members of the appeal committee and Jonathan Rose. One member of the committee asked Person B, ‘did you ever egg him on? Goad him on?’ Jonathan Rose was allowed to ask Person B, ‘what was I supposed to have done to you that night?’ As she had already provided an account of the nature of her allegations of abuse in her testimony she responded, ‘you know what you did’. In her evidence to the inquiry, Person B explained that she understood a member of the committee to be instructing her to go into detail by telling her ‘answer the question’. Person B did as she was instructed and gave her testimony again, in front of 7 elders and Jonathan Rose.

On 29 April 2014, the Commission wrote to the trustees of the charity. The Commission had been notified by the police that Jonathan Rose had been released from prison and that he had attended the Kingdom Hall. The Commission was concerned about this and asked what the trustees were doing to identify and manage safeguarding risk and what advice they had received in this regard from WTBTSB. The Commission also referred to the appeal committee meetings of 2 April 2014 - it asked why these meetings were held, who was present, what the outcome was and if WTBTSB was aware. The Commission asked if Jonathan Rose had now been disfellowshipped. The Commission wrote in similar terms to WTBTSB.

On 1 May 2014, one of the charity’s trustees announced at the charity’s Kingdom Hall that Jonathan Rose was no longer a Jehovah’s Witness. Person B, who was no longer a member of the congregation and so did not hear the announcement, told the inquiry that she found this out via a third party – she was not herself told directly. It is not known whether any talk was delivered to the congregation to ‘explain the wrongness of the conduct and how to avoid it’, which was an optional step under the charity’s relevant procedures at the time.

On 5 May 2014, the trustees of the charity wrote to the Commission to say that Jonathan Rose was no longer one of Jehovah’s Witnesses but that he was continuing to attend public meetings; however, ‘most of the trustees are present at each meeting and observe and manage the behaviour of all present’. The trustees did not comment on the meeting of 2 April 2014 other than to say ‘procedures were in accordance with the long-standing practices of Jehovah’s Witnesses, and questions regarding these may be directed to our headquarters in London’.

On 6 May 2014, WTBTSB wrote to the Commission to confirm that Jonathan Rose had indeed been disfellowshipped and added ‘we also want to restate that in harmony with our guidelines and procedures complainants are perfectly at liberty to attend or decline to attend any disciplinary proceedings’.

Subsequent statements regarding Mr Rose’s disfellowshipping

An article about the matter was published in the Manchester Evening News on 21 May 2014. A spokesperson for Jehovah’s Witnesses was quoted as saying, ‘you ask about allowing individuals such as Mr Rose to attend our congregation meetings. As our congregations are places of public worship, they are open to the public. Nevertheless, elders will always comply with restrictions imposed by the courts or police on offenders’ movements. When a Jehovah’s Witness is accused of child abuse, local congregation elders are expected to investigate. If a victim wishes to address a matter, this can be done directly or in writing. No victims are forced to attend a meeting or confront an alleged perpetrator of child abuse. Of course it may not be possible to handle a matter in the congregation until the authorities have completed their investigations or if the person is incarcerated. Jehovah’s Witnesses certainly do not condone child abuse. Child abuse is abhorrent’.

WTBTSB wrote to the Commission on 10 July 2014, after the opening of the inquiry. In this letter, it stated that, ‘our policies do not oblige presumptive victims to appear at a hearing in person before an alleged perpetrator and we regret the fact that the independent elders appear to have created the impression that this was essential’. In his witness statement of 14 November 2014 as part of the Tribunal proceedings, one of the charity’s trustees refers to the original disfellowshipping of Mr Rose in October 2013 and states, ‘the trustees at New Moston played no role in that process and did not receive any official notification that the proceedings were actually taking place’. He also refers to the appeal committee proceedings and states, ‘the Elders on the Appeal Committee, again, did not include trustees of the New Moston Charity’. He adds, ‘the only step we took as trustees was to announce to the congregation that Mr Rose was no longer one of Jehovah’s Witnesses’. The trustee then states, ‘I, and my fellow trustees, understand that victims do not need to attend disfellowshipping meetings with those responsible for abusing them. If the trustees of the charity had arranged Mr Rose’s disfellowshipping process we would not have required his victims to attend a meeting with him’.

The inquiry notes that on 14 August 2015, in his testimony before the Australian Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, a member of the Governing Body of Jehovah’s Witnesses said that, ‘there are no circumstances in which the survivor of sexual assault should have to make her allegation in the presence of the person whom she accuses of having assaulted her’.

The inquiry’s findings on how the charity dealt with the risks posed by Jonathan Rose during the criminal proceedings in 2013 and following his release from prison in 2014

The inquiry found that, contrary to the initial information received by the Commission, the charity’s trustees were not part of the judicial committee that decided to disfellowship Mr Rose in October 2013, nor part of the appeal committee that upheld this decision in May 2014.

However, the inquiry found that the trustees of the charity retain responsibility for the judicial committee proceedings and the appeal committee proceedings for the disfellowshipping of Mr Rose. This is for the following key reasons:

- the inquiry considers that in this instance the charity relied upon the judicial committee proceedings to manage the safeguarding risks presented by Mr Rose following his release from prison

- the disfellowshipping of Mr Rose in May 2014 has the effect, under the charity’s governing document, of removing him as a member of the congregation, thereby removing rights under the charity’s governing document as a matter of charity law, such as the right to vote at general meetings of the charity[footnote 7] - as such, the disfellowshipping proceedings can be viewed as a procedure of the charity, for which the trustees are ultimately responsible in their role as charity trustees

The inquiry found that there were serious failings, from a safeguarding perspective, in the handling of the appeal committee hearings in April 2014. The inquiry found that:

- witnesses, who had suffered or made allegations of child sexual abuse, endured inappropriate, demeaning and disrespectful questioning by the appeal committee and Mr Rose

- this questioning took place in the presence of Mr Rose, who had been convicted of indecently assaulting 2 of the witnesses

- Mr Rose was permitted to cross-examine at individuals whom he had been convicted of indecently assaulting or had made previous allegations of sexual abuse

The inquiry noted the subsequent assurance from WTBTSB that Jehovah’s Witnesses’ policies ‘do not oblige presumptive victims to appear at a hearing in person before an alleged perpetrator’, and the statements to this effect made by a representative of the Jehovah’s Witnesses to the Manchester Evening News and by a member of the Governing Body of Jehovah’s Witnesses to the Australian Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. These statements have been reinforced by changes to the relevant policy and procedures. These indicate that what happened in this case did not comply with the Jehovah’s Witnesses relevant procedures as explained below.

The administration, governance and management of the charity by the trustees and whether or not the trustees of the charity have complied with and fulfilled their duties and responsibilities as trustees under charity law

In view of the findings above, the inquiry found that, overall, the trustees of the charity did not take adequate steps to identify and manage the safeguarding risks presented by Mr Rose in the period between the allegation from Person A in February 2012 and the aftermath of Mr Rose’s release from prison in March 2014.

The remainder of this subsection addresses (a) the trustees’ engagement with the Commission as charity regulator and (b) subsequent changes made to the charity’s safeguarding policy and procedures.

The trustees’ engagement with the Commission as charity regulator

The inquiry found that the trustees of the charity did not engage openly and candidly with the Commission as the charity regulator. The trustees did not report the allegations to the Commission as a serious incident.

The inquiry was concerned that the trustees failed to disclose to the Commission in September 2012 that they were aware of an earlier allegation of child sexual abuse made by Person B against Mr Rose in the early 1990s. The inquiry found that 3 of the trustees had been involved as a trustee, either directly or indirectly, when this allegation was made, the trustees told the Commission, in a letter of 7 September 2012, that ‘We have no knowledge of any other allegations of a similar nature being made against Mr Rose’. The inquiry noted that the trustees had argued, in a letter to WTBTSB in October 2012 that the allegation made by Person B in the early 1990s was ‘not the same kind of wrongdoing’ as the allegation made by Person A in February 2012.

In addition, in a witness statement given in the Tribunal proceedings, one of the trustees argues in respect of similar questions at the meeting of 20 March 2014, ‘we thought that when asking about previous ‘issues’ or allegations, the Commission was asking about outstanding allegations that had not been investigated, or which were still being investigated. We did not appreciate that the Trustees were being asked about allegations in relation to which the jury found Mr Rose not guilty’.

The inquiry did not accept that these points justified the trustees’ lack of candour with the Commission. It was clear that, in September 2012, the Commission was asking the trustees about allegations, and that this would include allegations that were not proven. In addition, the inquiry did not accept that the allegations made by Person B could be discounted on the basis that they were not sufficiently similar. In both cases - and the subsequent case of Person C - individual beneficiaries of the charity had made allegations that Mr Rose had sexually abused them while they were children. The trustees ought to have recognised the similarity between the allegations and to have assessed the safeguarding risks to the charity and its beneficiaries in this light.

Changes to the charity’s safeguarding policy and procedures in 2016 and 2017

As noted above, the inquiry found that the charity’s policy and procedures on safeguarding were revised through the issue of a ‘Letter to All Bodies of Elders’ in August 2016 and a revised Child Safeguarding Policy in January 2017. The inquiry found that the revised policy and procedures include several changes that address issues identified by the inquiry. In particular, the inquiry noted the following changes:

- the revised policy now states explicitly that a victim of child sexual abuse is not required to make the allegation in the presence of the alleged abuser, either as part of an investigation or during any subsequent congregation judicial committee hearing (paragraph 14 of revised Child Safeguarding Policy; the same point is made in the revised procedures)

- the policy makes clear that the elders should act upon an allegation (by contacting the legal department of the branch office) ‘even if the allegation is unsupported’ (paragraph 10), which the inquiry understands to mean where the allegation is not supported by a second witness in accordance with what has been called the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ ‘two-witness rule’

- the policy provides that restrictions will be placed on individuals found to have engaged in child sexual abuse by the ‘secular authorities’ (which the inquiry understood to include the criminal courts), as well as where such findings are made by congregation judicial committees

The inquiry welcomes the improvements to the charity’s safeguarding policy and procedures on these points.

A more general assessment of the revisions to the Child Safeguarding Policy and the related procedures is being carried out as part of the Commission’s separate, but related, inquiry into WTBTSB.

Conclusions

The Commission has concluded that the charity’s trustees did not deal adequately with allegations of child sexual abuse in 2012 and 2013 against one of the trustees. This is because they did not:

- Identify one allegation as potential child sexual abuse, believing it to be merely ‘a matter between 2 teenagers’.

- Properly take account of an earlier allegation of child sexual abuse when considering new allegations made in 2012.

- Fully enforce the restrictions the trustees decided to place on Mr Rose’s activities in February and July 2012.

- Consider and deal with potential conflicts of loyalty within the trustee body.

- Keep an adequate written record of the decision making process used to manage the potential risks posed by Mr Rose to the beneficiaries of the charity.

The Commission has also concluded that the charity’s trustees did not deal adequately with a misconduct appeal hearing against Mr Rose in 2014 following his release from prison. This is because victims were effectively required to attend the misconduct appeal hearing and repeat their allegations in the presence of the abuser, and the abuser was permitted to question the alleged victims. Although the trustees did not themselves conduct the hearing, they remain responsible for ensuring that the charity’s procedures do not expose its beneficiaries or others to significant risks of harm, and they failed to do this.

It is the inquiry’s view that the charity’s trustees did not cooperate openly and transparently with the Commission. In particular, they did not provide accurate and complete answers to the Commission regarding the earlier allegation of child sexual abuse and the conduct of the misconduct hearing against the former trustee. The inquiry was concerned that the charity trustees did not report a serious incident to the Commission.

The above matters constitute misconduct or mismanagement in the administration of the charity.

The charity has a written policy on child safeguarding. It also has internal procedures for the handling of misconduct allegations within its congregation, which are used to deal with allegations of child sexual abuse.

The Commission welcomes the changes implemented to the procedures since the launch of the inquiry for the handling of misconduct allegations and to the child safeguarding policy applicable to the charity. These revisions improve the charity’s written policy and procedures for handling child safeguarding allegations, including by making clear that victims of child sexual abuse are not required to make their allegations in the presence of the alleged abuser, and providing for protective restrictions to be put in place in all cases where an individual is found to have engaged in child sexual abuse by the criminal courts.

The policy and procedures are common to all Jehovah’s Witness congregations in England and Wales and are being examined further as part of the Commission’s ongoing inquiry into WTBTSB. The Commission is also examining as part of the ongoing WTBTSB inquiry the practical measures which will be taken to minimise the risk of the issues identified by this inquiry from recurring in other congregations. Issues of particular relevance to this inquiry that will be examined further in the WTBTSB inquiry include:

- the application of the ‘two-witness rule’

- how and to what extent in practice victims will be involved in future Judicial Committees and related procedures the practice of requiring victims to confront their abuser during the judicial committee procedure

- record keeping and disclosure of information to public bodies and individuals

Issues for the wider sector

Charities that carry out activities with children or vulnerable adults, whether regular or otherwise, need to ensure that they have adequate measures in place to assess and address the risks posed. Even where such work does not form part of the core business of the charity, trustees must be alert to their responsibilities to protect from harm vulnerable groups with which the charity comes into contact. Charities that fund other organisations whose activities involve contact with children or vulnerable adults should also assure themselves that the recipient body has in place adequate safeguarding practices.

Additionally, on occasion charities may be targeted by people who abuse their position and privileges to gain access to vulnerable people or their records for inappropriate or illegal purposes. Trustees must be alert to this risk and take proactive steps to mitigate it. Protecting children and vulnerable adults from the risk of radicalisation should also be seen as part of this wider safeguarding responsibility.

Trustees are under a duty to act prudently and at all times to act exclusively in the best interests of their charity and to discharge their duties in accordance with their duty of care. In consequence it is essential that charities engaged with children or vulnerable people (a) have adequate safeguarding policies and procedures which reflect both the law and best practice in this area, (b) ensure that trustees know what their responsibilities are and (c) ensure that these policies are fully implemented and followed at all times. Trustees must therefore regularly review the steps that are taken to provide them with assurance on the fitness for purpose of their policies and the extent of compliance in the charity’s practice with those policies.

Any failure by trustees to safeguard children or vulnerable adults and to manage risks to them adequately would be of serious regulatory concern to the Commission and it may consider this to be misconduct or mismanagement, or both, in the administration of the charity.

If a charity is dealing with a safeguarding incident, as well as reporting these to the appropriate statutory agencies, it is important that the charity also reports it to the Commission as a serious incident and does so as soon as possible after they become aware of them. You should make a report if any one or more of the following things occur:

- there has been an incident where the beneficiaries of your charity have been or are being abused or mistreated while under the care of your charity or by someone connected with your charity such as a trustee, member of staff or volunteer

- there has been an incident where someone has been abused or mistreated and this is connected with the activities of the charity or charity personnel

- allegations have been made that an incident may have happened, regardless of when the alleged abuse or mistreatment took place you have grounds to suspect that such an incident may have occurred

As well as reporting to us, you should also notify the police, local authority and/or relevant regulator or statutory agency responsible for dealing with these incidents.

The Commission cannot investigate or deal with the incidents of abuse or mistreatment, but it will need to make contact with the other agencies or regulators and follow up on their investigations. The Commission’s role is to ensure the trustees are handling the incident responsibly and going forward where necessary improved governance and controls are put in place by trustees in order to protect the charity and its beneficiaries from further harm.

For further help about safeguarding and trustee duties see the Commission’s guidance on strategy for dealing with safeguarding issues in charities and safeguarding children and young people policy paper.

-

Jonathan Rose joined the charity’s congregation in March 1990. He became a congregational elder and a trustee of the charity in August 2009. The Commission was notified that he resigned as a charity trustee on 7 September 2012. During the inquiry the trustees informed the Commission that Mr Rose’s actual resignation had taken place in August 2012. ↩

-

‘Regulated Activity’ is a technical term defined in safeguarding legislation. In summary, regulated activity is work that cannot be carried out by a person who is ‘barred’, because they are considered unsuitable for certain types of work with children and/or adults. Further information is available from the Disclosure and Barring Service, which maintains the relevant lists. ↩

-

The trustees of WTBTSB told the inquiry that in evaluating whether there is sufficient evidence for elders to take congregation judicial action against a congregation member accused of a serious sin, Jehovah’s Witnesses follow the Bible’s rule of evidence: ‘No single witness may convict another for any error or any sin that he may commit. On the testimony of 2 witnesses or on the testimony of 3 witnesses the matter should be established.’ (Deuteronomy 19:15; Matthew 18:16; 1 Timothy 5:19 (New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures - 2013 Revision)). Thus, congregation elders are not authorized by the Scriptures to take congregation judicial action against a congregation member accused of child abuse unless the accused confesses, there are 2 witnesses to the alleged child abuse, or there are 2 victims who testify to separate incidents of child abuse by the accused. ↩

-

Representatives of WTBTSB and CCJW told the inquiry that Representative A was acting as a representative of CCJW during his contact with Person B, not a trustee of WTBTSB as Person B had assumed. ↩

-

Representatives of WTBTSB and CCJW told the Commission that neither WTBTSB nor CCJW has any record of receiving this letter. ↩

-

The Commission is considering the judicial committee and appeal process and in particular the practice of victims confronting their abusers further in the WTBTSB inquiry. ↩

-

The charity’s constitution defines ‘Congregation Members’ as including ‘Jehovah’s Witnesses from time to time in fellowship’ (emphasis added). ↩