Invasive meningococcal disease in England: annual laboratory confirmed reports for epidemiological year 2023 to 2024

Updated 20 January 2025

Applies to England

Laboratory confirmations

This report presents data on laboratory-confirmed invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) for the epidemiological year 2023 to 2024. Epidemiological years run from week 27 in one year (beginning of July) to week 26 the following year (end of June).

Note: When most cases of a disease arise in the winter months, as for IMD, epidemiological year is the most consistent way to present the data as the peak incidence may be reached before or after the year end. Using epidemiological year avoids the situations where a calendar year does not include the seasonal peak or where 2 seasonal peaks are captured in a single calendar year.

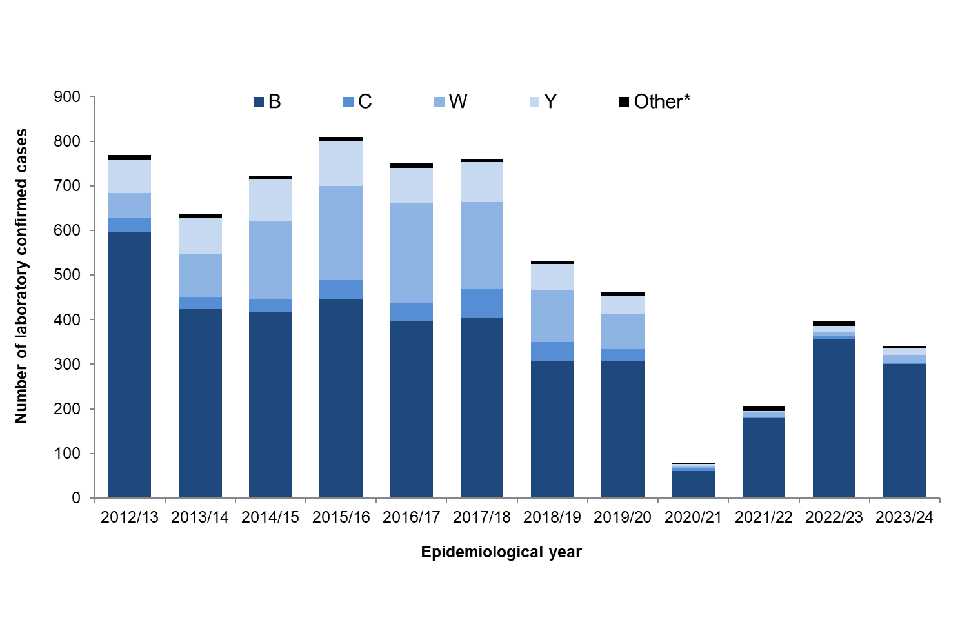

In England, the national UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) Meningococcal Reference Unit (MRU) confirmed 341 cases of IMD in 2023/24, compared to 396 cases reported in 2022/23 when the country was emerging from COVID-19 pandemic restrictions (table 1). IMD cases had fallen by 83% in 2020/21, with 80 cases, compared to 463 confirmed cases in 2019/20, and 531 confirmed cases in 2018/19, before the COVID-19 pandemic began (figure 1).

The COVID-19 pandemic and the implementation of social distancing measures and lockdown periods across the UK had a marked impact on the spread and detection of other infections including IMD (1). With the complete withdrawal of COVID-19 containment measures in England from July 2021, overall IMD case numbers began to return to pre-pandemic levels driven mainly by group B meningococcal disease (MenB). Cases due to the other capsular groups remained very low because of the highly effective indirect (herd) protection provided by the adolescent meningococcal ACWY (MenACWY) conjugate vaccine programme, alongside direct protection in those vaccinated (2).

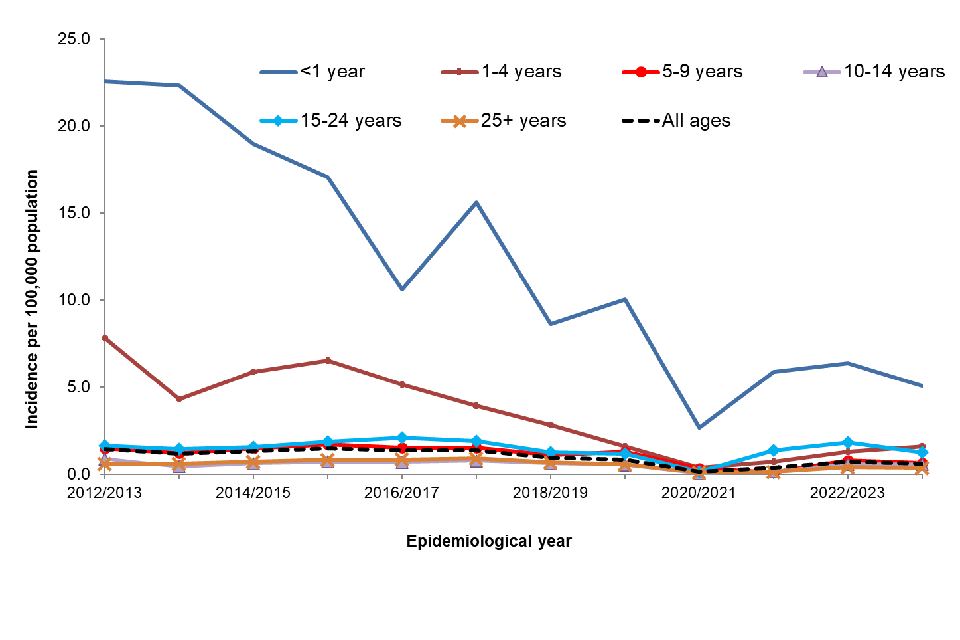

In England, there has been a marked overall decline in confirmed IMD cases from a peak of 2,595 cases in epidemiological year 1999/2000. The initial decline was driven by the introduction of vaccination against group C (MenC) disease in 1999, which reduced MenC cases by approximately 96% (to around 30 to 40 cases each year). Total IMD has continued to decrease from 2 per 100,000 in 2006/07 to 1 per 100,000 since 2011/12. This latter decline was mainly due to secular changes in group B (MenB) cases before the introduction of the MenB infant and MenACWY teenage vaccination programmes in 2015. IMD incidence is currently below 1 per 100,000 (figure 2) (3).

The distribution of IMD cases by capsular group in 2023/24 is summarised in table 1, with MenB accounting for 88.3% of all cases (301 of 341), followed by MenW (n=17, 5.0%), MenY (n=15, 4.4%), and MenC (n=3, 0.9%). Five ungrouped/ungroupable cases were also reported.

In 2023/24, 301 individuals were confirmed with MenB invasive disease, compared to 356 cases in 2022/23, 179 cases in 2021/22 and 61 in 2020/21.

MenB was responsible for the majority of IMD cases in individuals under 25 years of age: for 100% in infants (29 of 29 cases), for 98% in 1 to 4 year-olds (39 of 40), for 95% in 5 to 9 year-olds (20 of 21), 90% in 10 to 14 year-olds (18 of 20), 96% in 15 to 19 year-olds (52 of 54) and for 94% in 20 to 24 year-olds (29 of 31).

In 2023/24 MenB also contributed to the highest proportion of cases in individuals aged 25 years and over: 78% (114 of 146) (table 2), a lower proportion than in 2022/23 (84%, 132 of 157) but a greater proportion than in 2021/22 (67%, 37 of 55) and 2020/21 (66%, 21 of 32). In earlier years MenB accounted for a smaller proportion of cases in this age group (45%, 99 of 218 cases in this age group in 2019/20 and 36%, 93 of 259 in 2018/19). This proportionate distribution by serogroup changed as disease covered by MenACWY vaccine was markedly reduced, following the vaccine introduction for teenagers from August 2015, and has remained very low following the impact of social measures taken to help control the COVID-19 pandemic.

There were 17 MenW cases in 2023/24, compared to 10 cases in 2022/23. This includes several MenW cases known to have had recent travel to the Middle East (4). MenW cases in 2023/24 were 66% lower than in 2019/20 when 78 cases were reported.

MenC cases remained low, with 3 cases reported in 2023/24, 6 cases in 2022/23, and 5 in 2020/21, compared to 27 cases in 2019/20. Similarly, MenY cases also remained low with 15 cases in 2023/24, and 14 cases in 2022/23 compared to a peak of 100 cases in 2015/16 (table 1).

Adults aged 25 years and older accounted for 2 of 3 MenC cases, all MenW cases, 80% of MenY cases, and 38% of MenB cases (table 2).

Deaths

The provisional IMD case fatality ratio (CFR) in England was 2.3% (8 of 341) in 2023/24, based on Office for National Statistics (ONS) death registrations recording meningococcal disease as an underlying cause.

Note: Death data from the Office of National Statistics includes all deaths coded to meningitis or meningococcal infection as a cause of death and linked to a laboratory-confirmed case.

Vaccine coverage

Infants in the UK were offered routine MenB immunisation with 4CMenB from 1 September 2015 (5). In England, the latest annual vaccine coverage estimates (1 April 2022 to 31 March 2023) for infants eligible for 4CMenB were 91.0% for 2 doses by 12 months of age and 87.6% for the one-year booster dose by 24 months of age (6). The schedule has been shown to be highly effective in preventing MenB disease in infants and toddlers (7).

The previously reported increase in MenW cases (8, 9) led to the introduction of MenACWY conjugate vaccine to the national immunisation programme in England from 2015 (10). The MenACWY teenage vaccine has led to large reductions in IMD caused by these capsular groups across all age groups as a result of both direct and indirect (herd) protection (2). Coverage for young people routinely offered MenACWY vaccine in the 2022/2023 school year (end August 2023) was 68.6% (Year 9) and 73.4% (Year 10) (11).

All teenage cohorts remain eligible for opportunistic MenACWY vaccination until their 25th birthday and it is important that these cohorts continue to be encouraged to be immunised, particularly if they are entering higher education institutions where their risk of disease is much higher than that of their peers (12).

There are useful resources available free of charge from UKHSA and from meningitis charities to support messaging on the importance of vaccination, awareness of signs and symptoms of meningitis and septicaemia, and the need to seek early clinical help.

Table 1. Invasive meningococcal disease in England by capsular group and laboratory testing method: epidemiological years 2022 to 2023 and 2023 to 2024

| Capsular groups [note 1] |

Culture and PCR (2022/23) | Culture and PCR (2023/24) | Culture only (2022/23) | Culture only (2023/24) | PCR only (2022/23) | PCR only (2023/24) | Total (2022/23) | Total (2023/24) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 66 | 60 | 78 | 82 | 212 | 159 | 356 | 301 |

| C | – | – | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 3 |

| Ungrouped/ungroupable [note 2] |

– | – | 2 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 9 | 5 |

| W | 3 | 3 | 7 | 14 | – | – | 10 | 17 |

| Y | 1 | 3 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 14 | 15 |

| Z | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – |

| Total | 71 | 66 | 96 | 110 | 229 | 165 | 396 | 341 |

Note 1: No cases of group A, X, E or Z were reported during the period covered by the table.

Note 2: ‘Ungroupable’ refers to invasive clinical meningococcal isolates that were non-groupable, while ‘ungrouped’ refers to isolates that were culture-negative but PCR screen (ctrA) positive and negative for the four genogroups [B, C, W and Y] routinely tested for.

Figure 1. Invasive meningococcal disease in England by capsular group: 2012/13 through to 2023/24

*Note: ‘Other’ includes capsular groups: A, X, E, Z, ungrouped and ungroupable. Ungroupable refers to invasive clinical meningococcal isolates that were non-groupable, while ungrouped cases refers to culture-negative but PCR screen (ctrA) positive and negative for the four genogroups [B, C, W and Y] routinely tested for.

Figure 2. Incidence of invasive meningococcal disease in England: 2012/13 through to 2022/23

Table 2. Invasive meningococcal disease in England by capsular group and age group at diagnosis: epidemiological year 2023/24

| Age groups | Capsular group B (%) | Capsular group C (%) | Capsular group W (%) | Capsular group Y (%) | Capsular group Other [note 1] (%) |

Annual total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 year | 29 (10) |

0 (–) |

0 (–) |

0 (–) |

0 (–) |

29 (9) |

| 1 to 4 years | 39 (13) |

0 (–) |

0 (–) |

0 (–) |

1 (20) |

40 (12) |

| 5 to 9 years | 20 (7) |

1 (33) |

0 (–) |

0 (–) |

0 (–) |

21 (6) |

| 10 to 14 years | 18 (6) |

0 (–) |

0 (–) |

1 (7) |

1 (20) |

20 (6) |

| 15 to 19 years | 52 (17) |

0 (–) |

0 (–) |

2 (13) |

0 (–) |

54 (16) |

| 20 to 24 years | 29 (10) |

0 (–) |

0 (–) |

0 (–) |

2 (40) |

31 (9) |

| 25 to 44 years | 38 (13) |

0 (–) |

4 (24) |

1 (7) |

0 (–) |

43 (13) |

| 45 to 64 years | 34 (11) |

2 (67) |

5 (29) |

4 (27) |

1 (20) |

46 (13) |

| 65+ years | 42 (14) |

0 (–) |

8 (47) |

7 (47) |

0 (–) |

57 (17) |

| Total | 301 | 3 | 17 | 15 | 5 | 341 |

Note 1: ‘Other’ includes ungrouped and ungroupable. ‘Ungroupable’ refers to invasive clinical meningococcal isolates that were non-groupable, while ‘ungrouped’ cases refer to culture-negative but PCR screen (ctrA) positive and negative for the 4 genogroups (B, C, W and Y) routinely tested for.

References

1. Subbarao S and others. ‘Invasive meningococcal disease, 2011 to 2020, and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, England’ Emerging Infectious Diseases 2021: volume 27, number 6

2. Campbell H and others. ‘Impact of an adolescent meningococcal ACWY immunisation programme to control a national outbreak of group W meningococcal disease in England: a national surveillance and modelling study for teenagers to control group W meningococcal diseases, England, 2015 to 2016’. Lancet Child Adolescent Health 2022: volume 6, issue 2

3. Office for National Statistics. Mid-year 2022 population estimates

4. Vachon MS, Barret AS, Lucidarme J, Neatherlin J, Rubis AB, Howie RL and others (2024). ‘Cases of meningococcal disease associated with travel to Saudi Arabia for Umrah pilgrimage - US, UK and France, 2024’. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: volume 73, number 22, pages 514 to 516

5. Public Health England and NHS England (22 June 2015). ‘Introduction of Men B immunisation for infants’ (Bipartite letter)

6. UKHSA and NHS Digital (28 September 2023). ‘Childhood vaccination coverage statistics – England 2022 to 2023’

7. Ladhani S and others (2020). ‘Vaccination of Infants with Meningococcal Group B Vaccine (4CMenB) in England’. New England Journal of Medicine: volume 382, number 4

8. Public Health England (2015). ‘Continuing increase in meningococcal group W (MenW) disease in England’. Health Protection Report: volume 9, number 7 (news)

9. Public Health England (2014). ‘Freshers told ‘it’s not too late’ for meningitis C vaccine’. Press release (27 November)

10. Public Health England and NHS England (22 June 2015). ‘Meningococcal ACWY conjugate vaccination (MenACWY)’. (Bipartite letter)

11. UKHSA (2024). ‘Meningococcal ACWY (MenACWY) vaccine coverage for adolescents in England, academic year 2022 to 2023 ’. Health Protection Report 2023: volume 18, number 9 (10 October)

12. Mandal S and others (2017). ‘Risk of invasive meningococcal disease in university students in England and optimal strategies for protection using MenACWY vaccine’, Vaccine: volume 35, issue 43