Mental Health and Employment Partnership: second interim report (summary)

Published 5 November 2024

Applies to England

This briefing summarises findings from the second report of the Mental Health and Employment Partnership (MHEP) evaluation. MHEP is funded through the Life Chances Fund (LCF), which is a £70 million fund supporting 29 locally-commissioned social outcomes partnerships (SOPs, also known as social impact bonds). The LCF supports 5 MHEP projects, which deliver an intervention known as ‘Individual Placement and Support’ (IPS), helping people experiencing mental health issues, or with learning disabilities, to find and remain in work. The second report explores the implementation of the projects and tests the assumptions set out in the project’s theory of change which was described in the first report.[footnote 1] The report also provides an update on interim performance data for the projects.

Key findings

-

Improved accountability and commissioning practice: MHEP supported a data-driven and collaborative culture. Through continuous reporting and regular contract review meetings, commissioners gained a new understanding of how best to manage performance, and had more effective contractual levers to do so.

-

The challenge of complexity: MHEP’s contractual and payment structures were seen as unnecessarily complex. This complexity was, in some cases, perceived to undermine a number of elements of the programme, including: staff motivation; mission alignment between actors (e.g., between commissioners, providers and intermediaries); financial incentives for providers; and even the projects’ ability to realise outcome payments (due to a lack of clarity around evidence requirements).

-

Scaling and improving IPS: MHEP has contributed to the scaling of IPS. It informed the expansion of the IPS fidelity framework (the framework that assesses the quality and standardisation of IPS delivery) to include a minimum level of outcome performance. MHEP has also led to the creation of IPS Grow, an organisation which supports standardisation and coordination of IPS services across the UK.

-

Performance data: Among participants with severe mental illness, the job outcome rate was 32.3%, up to September 2023 (up from 29% in December 2021), meaning nearly a third of those engaging with the service have moved into employment. This is similar to the lower-end rates seen in the IPS implementation literature (generally 30-50%) and the NHS England’s benchmark for a new IPS service (30-40%). A full assessment of outcomes performance will be provided in the final evaluation report.

The second interim evaluation report primarily presents evidence from the qualitative process evaluation, focused on the implementation and delivery of the MHEP projects. It explores the experiences of key stakeholders, including commissioners, providers, investors, and the MHEP management team. In doing so, the report looks to further test the theory of change mechanisms set out in the first report.

The process evaluation draws on qualitative evidence from 27 semi-structured interviews with MHEP stakeholders, participant observation (conducted between August 2022 and January 2024), and analysis of key project documents. The report also provides updated quantitative data on programme performance.

MHEP was established in 2015 by Social Finance, backed by social investment (totalling £1.2m for the LCF projects) from Big Issue Invest. A team within Social Finance acts as the intermediary organisation (special purpose vehicle) responsible for contract monitoring and performance management (referred to here as the MHEP management team or MHEP staff). A summary of the MHEP projects is provided in the table below.

Table 1. Summary of MHEP projects

| Location | Haringey & Barnet | Shropshire | Enfield | Tower Hamlets (SMI) | Tower Hamlets (LD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy focus | Severe mental illness | Severe mental illness | Severe mental illness | Severe mental illness | Learning disabilities |

| Delivery period | April 2019 - April 2023 | April 2020 - April 2024 | April 2020 - April 2024 | April 2020 - April 2024 | July 2020 - September 2023 |

| Service provider | Twining Enterprise | Enable | Working Well Trust | Working Well Trust | JET |

| Local commissioner | Haringey & Barnet councils | Shropshire Council | Enfield Council | Tower Hamlets CCG | Tower Hamlets Council |

| Upfront capital investment | £227,000 | £204,000 | £126,000 | £300,000 | £328,000 |

| Maximum potential outcome payments | £1,421,234 | £1,034,484 | £620,689 | £2,068,270 | £1,307,059 |

| % outcome payment to providers* | 25% | 0% | 30% | 5% | 0% |

*the proportion of total contract value reserved for outcomes-related payments to providers

Key findings from the qualitative process evaluation

The report tests a number of key assumptions about the effectiveness of the programme, explored through the following questions:

1. Is there greater accountability through MHEP compared to other IPS services?

Providers, commissioners, and MHEP staff all perceived a greater level of accountability in the MHEP projects compared to traditional, non-SOP funding, of IPS services. This enhanced sense of accountability was related to four factors:

-

Continuous and active monitoring by the MHEP team, which prevented “coasting” by providers, but also enabled more tailored support.

-

More developed contractual levers for responding to under performance, including a series of planned steps to support performance improvement (described in Appendix C of the main report)

-

Greater commissioner involvement and engagement by the MHEP team, including recognition of high performance by providers (often contrasted to previous examples of disengagement from commissioners)

-

A focus on collaboration and learning which MHEP helped to foster through the use of data analytics, and a focus on capacity development of providers and commissioners (as opposed to a more punitive approach to performance monitoring and accountability).

“There’s so much that goes into running an IPS service, it’s a very busy job. There’s probably not an appreciation of that because it isn’t the traditional model of employment support. So you do want a commissioner to be interested, and I felt that MHEP have been interested.”

Service provider

While overall, MHEP functioned to drive up accountability, high staff turnover within the MHEP team, was perceived to undermine this at points. Over the course of the contracts, providers experienced six different MHEP managers, with a turnover of 8 to 9 months in the position. This high-cadence turnover within the core MHEP team was seen as somewhat destabilising by providers.

2. Does MHEP affect service quality?

There were four perceived improvements in service quality as a result of the MHEP approach:

-

More rigorous caseload management, with caseloads of between 20 and 25.

-

An emphasis on integration with clinical teams to support smoother referrals and clinical oversight of the mental health needs of service users.

-

A focus on a wider range of outcomes, which allowed for a more comprehensive assessment of performance (including on participant engagement, job entry, and job sustainment)

-

Continuous discussions on fidelity - the 25-item scale which measures service quality and adherence to IPS principles - enabled both providers and commissioners to have a common sense of “what good looks like”.

“The clinician’s perspective was amazing because they had operated with the non-outcomes [IPS] contract for years up until that point. When we shifted to the outcome-based contract, they were ‘oh, this service works, you actually get people jobs’, and would start referring.”

Service provider

Despite these improvements, some drawbacks were also identified by programme stakeholders that could negatively impact quality, including:

-

Fidelity assessments taking staff time away from service delivery, which meant the service could not run at full capacity during these periods (with knock-on effects on the level of outcomes that could be achieved/ claimed for).

-

Lack of an outcome payment for longer-term job sustainment, with no payment made after 13 weeks in work (this limited providers ability to support participants who had entered work over the longer-term).

Outcome-related payments to providers

MHEP exposed providers to comparatively low levels of outcome-related payments, ranging from 0 to 30% (while investors and intermediaries are still paid on the basis of outcomes). This was informed by evidence from the previous performance-related funding of MHEP through the Commissioning Better Outcomes fund.[footnote 2] Provider and MHEP staff interviewed for this report, agreed that this lower level of outcomes-related payment reduced perverse incentives for gaming or cherry-picking clients. Under MHEP there is, therefore, a more subtle approach to paying for outcomes, which ensures that providers still have “skin in the game” on performance, but limits some of the established drawbacks of a payment-by-results approach. The report found that there was no correlation between outcome performance and the level of outcome payments (as a proportion of overall contract value) each site was subjected to.

3. How did the structure of MHEP affect service delivery?

Programme stakeholders expressed difficulties in understanding and navigating the programme’s complex contractual and payment structures. Many outside of the MHEP management team believed this complexity to be unnecessary, and it was in some cases perceived to undermine staff motivation, collaboration between stakeholders, and even the overall level of outcome payments.

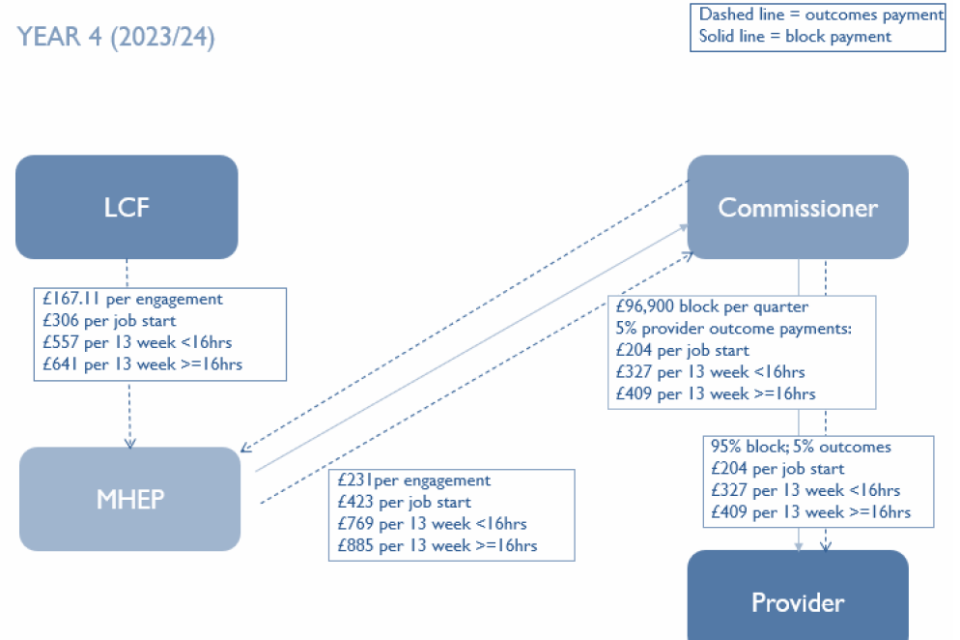

Figure 1. An example of the payment structures of one of the MHEP projects

The diagram in figure one shows the different payment values attached to specific outcomes, the ratio of outcome to “block” payments, and the payment flows between stakeholder organisations (LCF, MHEP team, the local commissioner, and service provider). It demonstrates a complex picture of bidirectional funding flows and differing outcome payment values.

A number of sources of complexity were identified:

-

Requirements of the Life Chances Fund: some stakeholders (particularly the MHEP team) felt that reporting requirements and other elements of the LCF (e.g., targets, and payment caps) added an extra layer of complexity to the programme.

-

Local contract variation: each MHEP project is structured with different outcome payment values and maximum payment levels due to requirements of different local commissioners, creating complexity at the programme level.

-

Lack of clarity on payment flows: stakeholders were unclear on why the project had been set up with such particular payment arrangements.

-

Complex financial modelling and analysis: the financial models developed by MHEP had to reflect the existing contractual specificity for each project, which compounded the overall level of complexity at a programme level.

“At times, it has been difficult to understand the contracting arrangements in the various MHEP [SOPs]. The MHEP contracting models are complicated, and often the response to queries relating to this remains unclear.”

Programme stakeholder

The “ideal” outcomes contract for IPS services

As a result of the MHEP experience, interviewees reflected on what an ideal IPS contract would look like. Below are some of the main innovations that stakeholders would like to see in future IPS contracts:

-

Longer contract duration (3 years + 2 years extension)

-

In-built technical assistance funding for performance management

-

Dedicated mobilisation phase (6 months)

-

Regular meetings with the commissioner

-

Holistic approach to IPS for mental and physical health

-

5% of provider contracts linked to outcomes

-

Investors providing a minimum of 3-6 months of working capital

4. Through what incentives does MHEP operate?

MHEP projects were expected to operate through strong financial incentives linked to outcome payments. However, in reality these financial incentives were muted as a result of:

-

Intrinsic motivation of provider staff, which meant that they were focused on client outcomes regardless of targets, and were often shielded from this aspect of the contract by managers.

-

Challenges around outcome target setting, with targets sometimes set too high (which felt unfeasible and demotivating to staff) or too low (which did not incentive performance once they had been met).

-

Lack of direct payments linked to outcomes, with frontline staff not financially rewarded for performance, and incentives for provider organisations moderated by the low proportion of payments linked to outcomes.

-

Contractual complexity, discussed above, meant provider staff did not fully understand the level of payment per outcome, or the evidence required to validate outcomes.

“It’s a lovely idea and I completely get the idea behind it. But I do think it’s a lack of understanding of how these services operate and how you can get the best outcomes and long-term outcomes for people so that they stay employed and stay off benefits.”

Service provider

In practice, providers seemed to respond more to: setting internal benchmarks for performance (e.g., comparing to previous “personal bests”); the experience of efficiency gains from improved use of data; and growing trust and alignment between providers and the central MHEP team.

Overall, there were mixed views on the appetite for the use of outcome payments in all IPS contracts. However, interviewees were mostly in favour of future outcome-based contracts provided that outcome payments were a low proportion of contract value and targets were achievable yet ambitious.

5. Does MHEP have a legacy?

One of the legacies of MHEP has been informing Social Finance’s development of IPS Grow, which was established in 2019. IPS Grow supports the expansion and coordination of IPS services, and provides operational support, workforce development, and tools to improve data and outcomes reporting. The experience of MHEP has in particular informed a new minimum performance requirement in the fidelity framework (quality standard) operated by IPS Grow (setting a minimum threshold of 30% entry into employment).

More broadly, providers and commissioners interviewed expect that some elements of the MHEP model will be maintained in future IPS contracts, while others are less likely to be carried over after the project comes to an end. These elements are summarised in the table below.

“We don’t want to reduce that envelope […] So MHEP sense checking the quality and the accuracy of the provider-submitted data and that’s something as the statutory commissioner, we’ve not been doing. There are various functions, data analysis and support that we would need to make sure we build into our arrangements going forward.”

Commissioner

Table 2. Likelihood of elements of MHEP model being continued.

| Potential legacy elements of MHEP | Likelihood of continuation |

|---|---|

| Professional development of staff including talent pipelines, leadership and retention of skills as a result of MHEP training | Likely (but some aspects are reliant on IPS Grow) |

| IT infrastructure supporting data and outcomes monitoring, and organisational processes. | Likely |

| Project key performance indicators (KPIs) | Likely |

| Securing sustainable longer-term contracts (through support around bids, including using data and qualitative feedback) | Likely (but still at risk) |

| Data analysis and data management function | At risk (due to capacity constraints) |

| Performance management function | At risk (due to capacity constraints) |

| Outcome verification: validating the quality and accuracy of provider-submitted data | At risk |

| Coordinating function: the pooling of central and local government funding | Unlikely (no alternative options identified) |

Interim performance data

The report also provides an update (from previous reporting of data up to the end of 2021) on the outcome performance of MHEP projects. The evaluation reports on performance across two metrics:

-

Success rate against target: how outcome performance compares to pre-agreed targets (for engagement, job starts, and job sustainment);

-

Outcome conversion rate: the proportion of participants achieving one type of outcome who go on to achieve subsquent outcomes (the job outcome rate is included in this ie, the proportion of engaged participants who move into work)

In terms of success rate against targets, MHEP projects are generally performing in line with medium scenario targets, although there are areas of both under and over performance, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Success rates against medium scenario targets from start of contract to September 2023.

| Outcome | Haringey & Barnet | Shropshire | Enfield | Tower Hamlets (SMI) | Tower Hamlets (LD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engagement | 104.5.% | 135.3% | 43.8% | 114.0% | 29.3% |

| Job starts | 89.5% | 102.1% | 67.0% | 91.6% | 96.0% |

| Job Sustainment | 80.6% | 73.3% | 68.1% | 77.9% | 369.0% |

The headline conversion rate, also known as the job outcome rate (the proportion of engaged participants that move into work) stood at 32.3% for the severe mental illness cohort, up to September 2023. This has increased slightly from the average of 29.0% up to December 2021. The current figure is similar to the lower-end rates seen in the IPS implementation literature (generally 30-50%) and the NHS England’s benchmark for a new IPS service (30-40%). The job outcome rate for each project is provided in Table 4.

Table 4. Job outcome rate from start of contract to September 2023.

| Conversion rate | Haringey & Barnet | Shropshire | Enfield | Tower Hamlets (SMI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engagements to job starts | 31.9% | 32.9% | 35.8% | 28.8% |

Next steps

Final reporting on the evaluation will include a full assessment of outcomes performance covering the total duration of LCF funding for MHEP projects. In addition there will be a full quantitative impact and economic evaluation.