Executive summary

Published 29 November 2022

Introduction

Music streaming has transformed how consumers listen to music. The rise of music streaming has given consumers easy access to large catalogues of music covering an array of genres and time periods for a fixed monthly price, or free with ads. As music streaming services have grown in popularity, consumer outcomes have improved significantly. Between 2009 and 2021 the monthly price of individual music streaming subscriptions has fallen by more than 20% in real terms because the price of these plans has not kept pace with inflation. At the same time, consumers have gained access to more music and more innovative and better quality services, for example higher quality audio, new video content and synced song lyrics.

Consumers have widely adopted music streaming – in the UK in 2021 there were 39 million monthly active users of music streaming services and there were over 138 billion streams. Streaming is now the primary means for artists and labels to distribute music and has been pivotal in securing the sector’s recovery from piracy.

Alt text: Image showing the music streaming value chain starting with creators, followed by music companies, then music streaming services and finally consumers, and that there are 39 million monthly active users of music streaming services

Some parts of the market have improved for artists in recent years, with more choice about the type of deals with record labels available and more able to directly release their music on streaming services. Average royalty rates in major deals for new artists have increased steadily from an average of 19.7% in 2012 to 23.3% in 2021. For songwriters, the share of revenues going to publishing rights has increased significantly from 8% in 2008 to 15% in 2021.

Whilst outcomes are good for consumers and generally improving for creators, we note that to some extent changes in the sector, precipitated by streaming, have made it harder for some creators. Reduced barriers to entry and more choice on how to distribute music has meant there are more artists than ever and, therefore, creators face more artists and songs to compete with for streaming revenues. Not only that, but the convenience of streaming means that older music is enjoying a resurgence of popularity, meaning that today’s artists need to work harder than ever to grab listeners’ attention.

These factors may be exacerbated by the fact that it is challenging for music companies to know who among the growing pool of creators will be successful. This inherent uncertainty combined with consumer tastes that tend to tip to a relatively small number of artists means that it is challenging for creators to succeed. We do not think that these factors arise from how firms compete in the market.

We have found that it is unlikely that the outcomes that concern many stakeholders are primarily driven by competition. Consequently, it is unlikely that a competition intervention would improve outcomes overall, and release more money in the system to pay creators more. In such circumstances, there is a greater risk that a competition intervention will result in unintended consequences and worse outcomes for both consumers and creators. The costs, risks and uncertainty created by a market investigation (which could run for 2 years) would be imposed on the industry and borne, ultimately, by consumers. We have therefore decided to not undertake a market investigation.

While there is limited potential for a competition intervention to improve outcomes, there remains a broader policy debate about the optimal distribution of existing revenues. We think it is a matter for Government and policymakers to determine whether the current split is appropriate and fair, and to explore whether wider policy interventions are required, for example those relating to the copyright framework and how music streaming licensing rates are set. We hope that our final findings provide insights that will be helpful for that continuing debate.

The effect of digitisation on the music industry

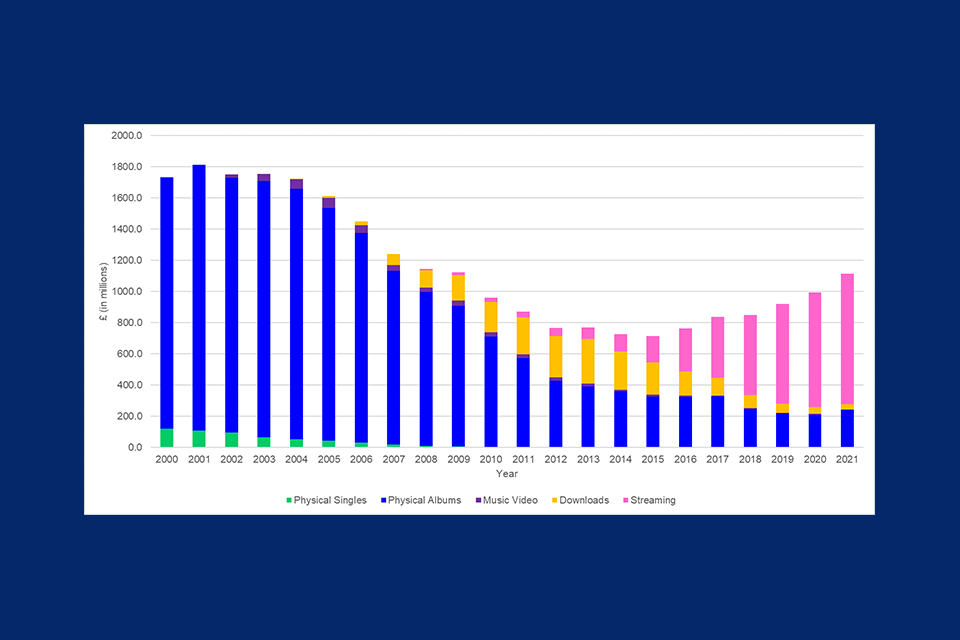

The introduction of the internet made music piracy easier than had previously been the case. Whilst piracy had always been a problem in the industry, the internet made it easier to illegally copy works and share them with other internet users on a large scale. The result was a collapse in music industry revenues, and therefore creator revenues, as CD and other physical sales declined. Inflation adjusted UK recorded music revenues fell by around 60% from £1.9 billion in 2001 to £0.8 billion in 2015.

Services that allowed consumers to access digital music legally, initially through paid downloads of songs followed by music streaming, meant that for the first time music companies and creators could monetise their content on digital services and stem the flow of revenue losses. Since the introduction of streaming, adjusting the older revenue figure for inflation music revenues have increased from £0.8 billion in 2015 to £1.1 billion in 2021, although these revenues remain below their £1.9 billion peak in 2001.

UK inflation-adjusted recorded music revenues between 2000 and 2021 by format type

Alt text: Bar chart showing UK inflation-adjusted recorded music revenues between 2000 and 2021 by format type. It shows that initially revenues came solely from physical albums and singles. In more recent years, streaming has generated the most revenue. Total revenue dipped in the 2010s, recovering after a low in 2015, but remains significantly lower than at its peak in 2001

Consumers have embraced legal music streaming and today music streaming accounts for more than 80% of music sales. Data published by Ofcom indicates that 47% of the population made weekly use of music streaming services in early 2022. This has nearly doubled since 2017, but has remained relatively stable since 2020, indicating that it might be plateauing. Younger people stream music the most, with 77% of 15 to 34-year-olds streaming music on a weekly basis compared with just 19% of those aged 55+.[footnote 1]

Alt text: Graphic saying more than 80% of music sales via music streaming services

Streaming has changed not only how we listen to music but what we listen to because for the first time all music, both old and new, is readily available in one place at no additional cost. This has created opportunities for labels, publishers, and creators to reach new audiences who may not have heard the music on its first release which has in turn extended the lifecycle for earning revenue from songs. This is a benefit to those creators whose music continues to be listened to, but this development is not necessarily good for all creators because it means that today’s new music competes with yesterday’s songs for a share of streaming revenue.

Digitisation and new online business models continue to create new opportunities to consume music. Today, besides new online radio stations, a consumer may hear a piece of music in a video on TikTok, see their favourite artist on a live stream rather than in concert, or engage with music alongside new interactive online gaming platforms. Whilst these are different to streaming services with full catalogues and music available on-demand, they are new ways that consumers hear and discover music and offer potential new sources of revenue for the music companies, artists, and songwriters.

The recorded music sector is concentrated, but that is not driving the concerns raised by artists

Our analysis shows that more creators than ever are releasing music, doubling from 200,000 in 2014 to 400,000 in 2020. This is, in part, made possible by innovations in technology and the ability to easily distribute music online. For example, it is now easier than ever to create and record music outside the confines of a traditional music studio and share it on streaming services without the need for a record label.

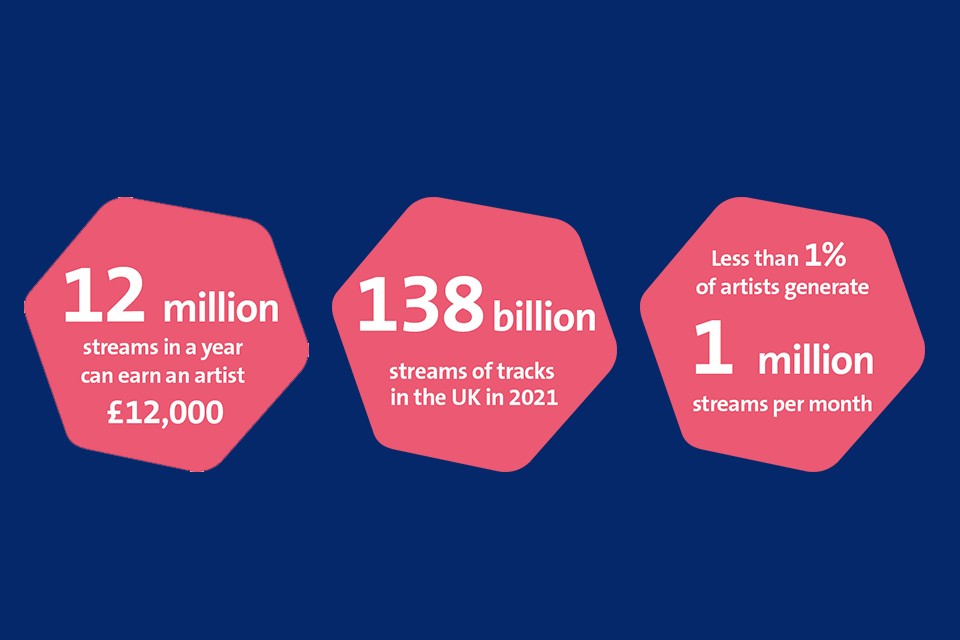

It has long been the case in recorded music that only a very small minority of artists will achieve the highest level of success. In 2020 over 60% of streams were of music recorded by only the top 0.4% of artists. To reach the top of the chart, songs need to be streamed many millions of times each day and many artists are faced with a situation where their work can be streamed millions of times, but it does not translate into a significant share of their income. For example, 12 million streams a year could earn an artist around £12,000, but less than 1% of artists achieve that number of streams. We have heard from both artists and songwriters that they are unable to make a sustainable income from music streaming and for many it feels unfair.

Alt text: 3 hexagons containing text as follows: 12 million streams in a year can earn an artist £12,000; 138 billion streams of tracks in the UK in 2021; less than 1% of artists generate 1 million streams per month

We have considered what may be causing these outcomes for artists[footnote 2] and, in line with our statutory duties, whether these outcomes are being caused by competition issues in the market.

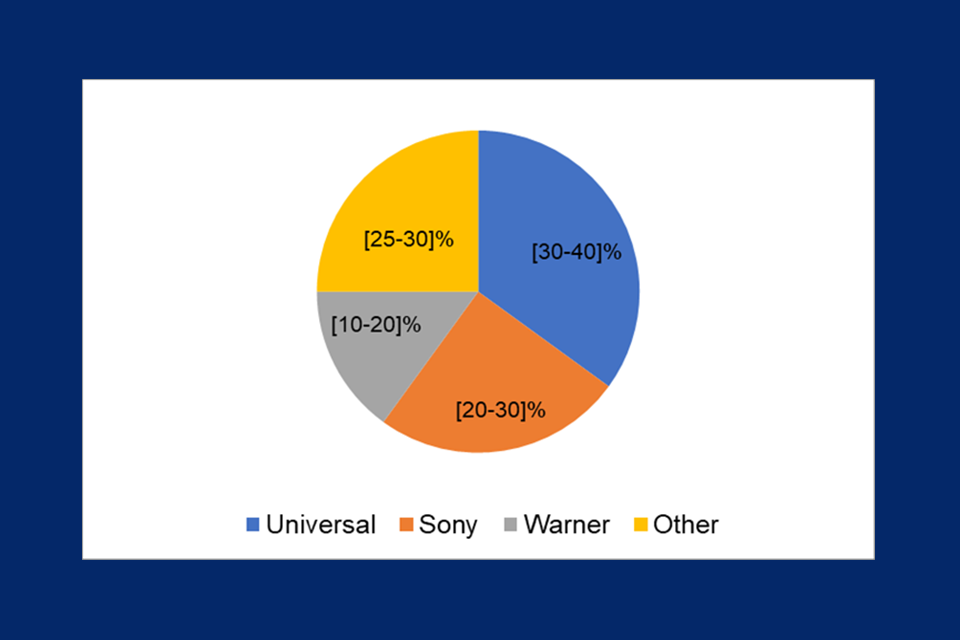

The recorded music sector is concentrated, with the 3 major labels holding a combined share of over 70% of UK streams, and this has persisted for some time. The market share in terms of streams of independent record companies (indies) has remained steady at around one quarter for several years. This share is very fragmented with only 2 indies having a share in excess of 1%.

Label shares of total UK streams in 2021

Alt text: Figure shows label shares of total UK streams in 2021. These are: Universal [30-40]%, Sony [20-30]%, Warner [10-20]%, and Other [20-30]%

Source: CMA analysis of data from Official Charts.[footnote 3]

The scale of the majors and their global reach means they can offer large advances which attracts proven and successful artists. In turn, this can make it difficult for indie labels to attract and retain artists as they become successful, which can create a barrier to expansion for indie labels.

Despite the concentrated nature of the market, outcomes for artists as a whole seem to be improving. We accept that this improvement may not be benefiting all artists, and that for many artists the improvement will seem insufficient.

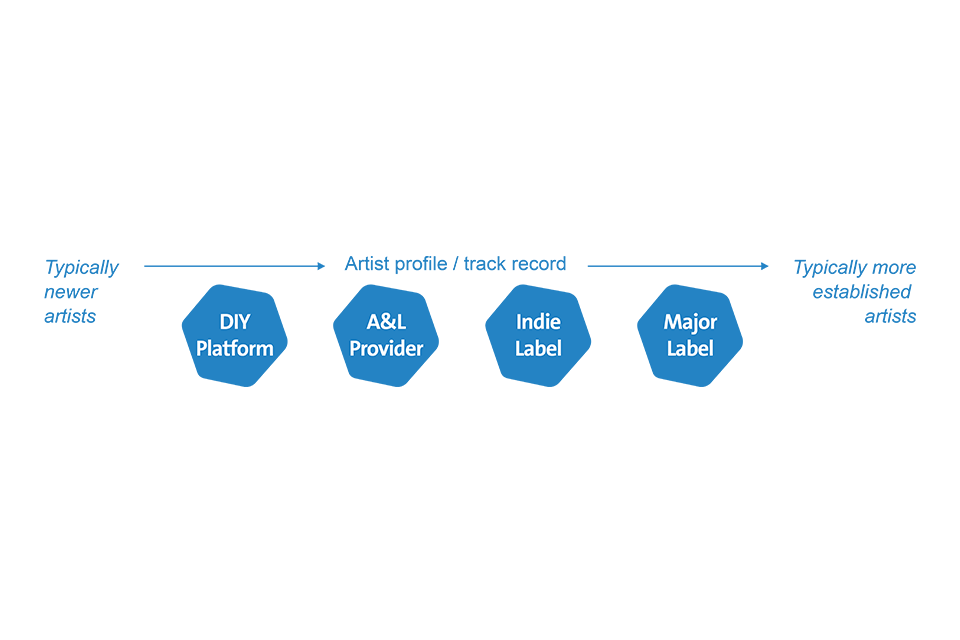

Our analysis shows that in some respects the options available to artists, particularly new artists, are improving:

- there is now more choice for artists about which type of deal they would like to agree, from DIY distribution, artist and label (A&L) services, or more traditional record deals

- some new artists have greater leverage when negotiating a record deal with a label if they have already built a strong fanbase and online presence

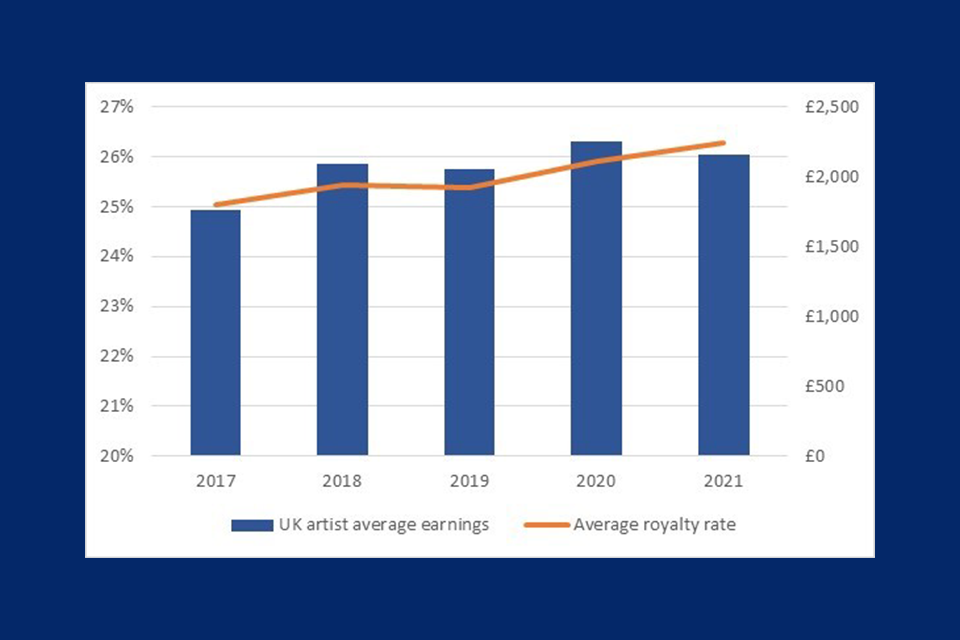

Average UK artist yearly streaming earnings from majors and average (mean) royalty rates (2021 prices) in the UK

Alt text: Figure showing the average UK artist yearly streaming earnings from majors and average royalty rates between 2017 and 2021. It shows a rising trend for both average earnings and average royalty rates. It also shows that the average UK artist earned £2,000 from streaming from majors in 2021 with an average royalty rate of around 26%

Source: CMA analysis of data from the majors

Analysis of new contracts signed by the majors with new artists for multi-track deals (meaning, albums or extended play (EP) records) shows that, between 2012 and 2021:

- the average gross royalty rate has increased from 19.7% to 23.3%

- the proportion of contracts where labels own copyright of recordings in perpetuity has reduced from 66% to 26.4%

- the average number of minimum commitment periods (where a period is defined by a commitment to produce a multi-track output such as an album) has fallen from 3.8 to 3[footnote 4]

Competition appears to be particularly focused on artists who are already popular or are likely to be. Competition to sign such artists can be very intense with offers from many labels. Traditional record deals also face increasing disruption from alternative models, in particular service deals from artist and label (A&L) service providers, and there are more options than ever for artists to reach audiences and monetise their work.

Alt text: Figure showing the differences in the artist propositions offered by different options. The figure shows the options as DIY platforms, A&L providers, indie labels and major labels, in that order. It suggests that artist profile and track record tends to increase across these options, with typically newer artists using DIY platforms and typically more established artists at the label end

We think that outcomes for artists are driven by factors which are largely unrelated to competition issues in the market. Rather, we think these outcomes can be attributed to factors more inherent to how music streaming works. Digitisation has allowed for a huge increase in the number of artists sharing their music and a vast back catalogue made available via streaming so there is more music available to stream and consumer tastes tend to tip towards a relativity small number of artists being successful. In addition, there is very significant uncertainty about which artists will be successful. The combination of these market features is likely to result in competition focused on a relatively limited number of artists and market outcomes where the majority of the benefits are accrued by a minority of artists.

We therefore conclude that a competition intervention, for example a change to the structure of the market, is unlikely to result in a material increase in revenues for artists.

Whilst majors’ profits have been increasing since the lows of piracy, our profitability analysis has not found evidence of substantial and sustained excess profits by the majors. This is consistent with our overall finding that there is unlikely to be scope to improve outcomes for artists substantially through increased competition.

We understand that Government has taken several steps to address concerns about creator remuneration and has responded to the DCMS Select Committee recommendations for legislative and policy reform in this area. In particular, the IPO is conducting a research programme including examining potential options to strengthen creator rights and remuneration. We are sharing our final findings with the IPO and DCMS to help inform their work.

Labels could do more to improve the information they provide to artists

We heard strong concern from some artists and their representatives that they do not get enough information from record labels on how their earnings from streaming services are calculated or how the deals that exist between labels and streaming services may affect what they earn or could earn in future. Non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) between music streaming services and labels were cited as a barrier to improving information provision to artists.

Our analysis shows that some artists are provided with information, such as number of streams and the royalties earnt on these streams, which tells them how much they have earned per stream on music streaming services, and we saw some positive examples of labels presenting this information in a user-friendly way. However, this was not consistent across all labels, and we think best practices could be developed so that information could be presented in a more straightforward and uniform way with appropriate guidance on how to interpret the data. This will help artists better understand how they are paid for streaming and the sources of their income.

In respect of NDAs, whilst they do prevent certain terms and conditions being made available to artists and limit access to the ‘source data’ from the music streaming services, they do not appear to prevent a significant amount of relevant information being made available to artists about their earnings. By limiting the access to source data, the NDAs may potentially limit the ability of artists to verify the accuracy of information. However, this is an issue more to do with verification of the fulfilment of contractual terms rather than one of competition to sign artists.

We welcome the work the IPO is undertaking on issues around transparency for artists, including developing a code of practice.

Publishing revenues from streaming in the UK have grown significantly, but many songwriters argue they are not paid enough to make a sustainable income

Each song has 2 sets of music rights:

- rights in the underlying song or ‘publishing rights’ which includes the music and lyrics

- rights in the particular recording of that song, the ‘recording rights’. Without permission to use both rights, a streaming service cannot legally stream the song

Throughout the study we have heard consistently from groups that represent songwriters that the publishing right of a song is systematically undervalued when compared to the recording right. In turn, they argue that this means that songwriters receive less in royalties for their work and do not make a sustainable income from streaming. Whilst some songwriters are also themselves artists and may have access to revenues from recording rights and other sources of income, that is not always the case.

Songwriters and their representatives have suggested that the undervaluation of publishing rights is because the majors have market power and interests in both publishing and recording rights and that it is financially advantageous for them to suppress publishing revenues in favour of the recording side of their business, possibly through tacit collusion. We have also heard concerns that the majors may have the ability and incentive to influence industry outcomes via their membership of collecting societies (CMOs) who have a role in negotiating royalties for the use of their members’ publishing rights.

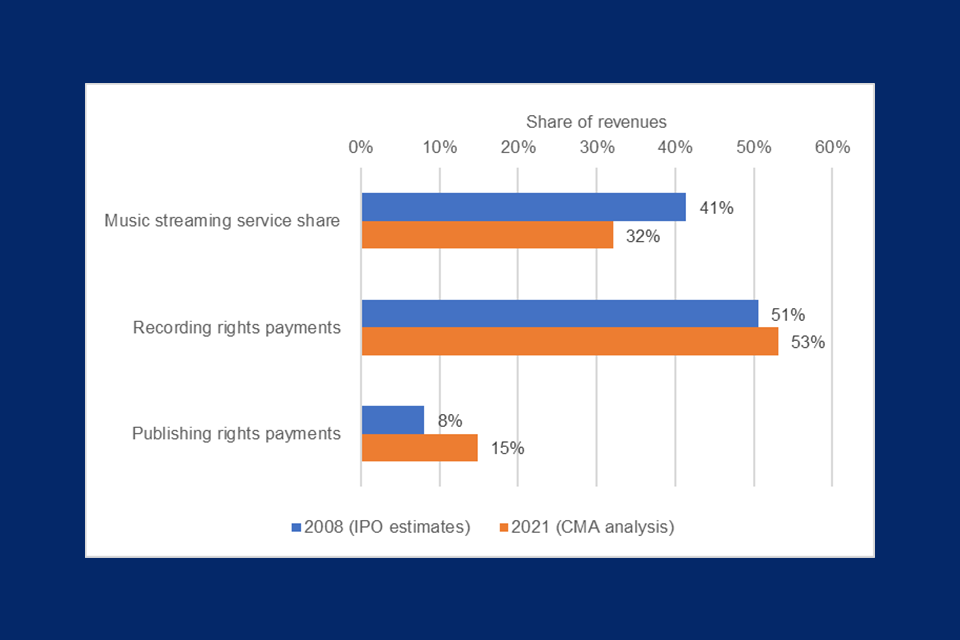

We have examined evidence on the allocation of music streaming revenues, and it indicates that:

- the share of revenues going to publishers (publishing share) increased from 8% in 2008 to approximately 12% in 2012. Since then it has increased to 15% in 2021. This is a significant increase across the period. In contrast, the share of revenues going to record companies in 2021 is at a broadly similar level to what it was in 2008

- for the majors, the growth in publishing revenues has far exceeded the growth in recording revenues

- majors’ growth in publishing revenues is 244% since 2017, which is significantly above the [110 to 120]% average across the publishing sector over the same period

Split in music streaming revenues in 2008 and 2021

Alt text: Figure showing the split in music streaming revenues in 2008 and 2021. Music streaming service share of revenues decreased from 41% in 2008 to 32% in 2021. Recording rights payments share of revenues increased from 51% in 2008 to 53% in 2021. Publishing rights payments share of revenues increased from 8% in 2008 to 15% in 2021

Source: Section 4.2.2 of research commissioned by the IPO Music Creators Earnings, the Digital Era, and On-Demand Streaming Revenues and CMA analysis of data from Apple, Amazon and Spotify.[footnote 5]

This evidence is inconsistent with the argument that the majors have tacitly colluded to suppress the publishing share or that there is otherwise particularly weak competition to sign songwriters that is leading to a split in the allocation of music streaming revenues that favours recording rights over publishing rights. The majors having both a recording and a publishing business is also not necessarily problematic. For instance, if the majors did not have a publishing business they might have a stronger incentive to block increases in the ‘publishing share’ by refusing to accommodate such an increase through reducing the recording share since any losses to their recording revenues which occurred would not be mitigated by gains to their publishing revenues.

We also have not seen clear evidence that CMOs are failing to push for better terms owing to the majors’ influence or that CMO governance procedures and processes are failing to mitigate any potential bias in their decision making. If such regulatory concerns do exist, the proper body to examine them is the IPO, which has responsibility for monitoring the conduct of CMOs under the Collective Management of Copyright (EU Directive) Regulations 2016.[footnote 6]

Songwriters are concerned that the initial split between publishing and recording revenues adopted when streaming began was unfair and unjustified, for example because it did not reflect the alleged lower costs of record companies under streaming compared to physical distribution. The increase in the publishing share is consistent with this concern over the initial split and there being a subsequent period of market-correction, which may not yet have fully played out. However, the fact that publishing revenues are increasing at a greater rate compared to recording revenues, in particular for the majors, suggests that publishing revenues are not being actively suppressed because of a distortion or restriction of competition.

We have found that there are inherent difficulties in securing increases to the publishing share and, consequently, increasing the amount songwriters are paid. This difficulty may arise from the fact that music streaming services, labels and publishers must all reach agreement to change how streaming revenues are divided. However, they may all have different incentives and so they may not agree – we call this a ‘licensing negotiation friction’. We think that agreement between the parties may be particularly challenging when an increase in the publishing share would necessitate a fall in the share that goes to record companies due to the strong bargaining position of music rightsholders, which arises from the need for music streaming services to get agreement from all key rightsholders to offer a wide range of music.

The long-term increase in the publishing share since 2008 has been accommodated by a fall in the share taken by music streaming services. The risk is that we may reach a point, or could do soon, where further substantial increases in the publishing share can only be accommodated by a fall in the recording share, which labels would be in a strong bargaining position to resist.

Whilst we think that competition for songwriters has driven up the existing publishing share, concerns exist that the current split could still be sub-optimal, particularly for songwriters. If that is the case, we think that it may take time for the split to adjust further, if at all, owing to the inherent licensing negotiation frictions and bargaining power of music rightsholders we have described. There is also a limit on the extent to which competition to sign songwriters can drive further increases in the publishing share, particularly if an increase needs to be accommodated by a fall in the recording share. Competition policy is not therefore the right tool to reach an optimal split. We think it is a matter for Government and policymakers to determine whether the split is appropriate and fair, and to explore what is needed to incentivise song writing as part of wider policy interventions on this split and other measures, for example those relating to the copyright framework and how music streaming licensing rates are set.

The legal arrangements between major labels and music streaming services are complex but they do not appear to be significantly hampering competition and innovation

Major labels rely on music streaming services to distribute their music, and streaming services cannot meet consumers’ needs without obtaining licences to the large catalogue of each major record label and publisher. Accordingly, music streaming services must negotiate deals with labels and publishers to access music content. These deals can be exceedingly complex and will cover financials and other terms. Our market study uncovered a number of clauses that could plausibly raise competition concerns. For example a number of agreements contained non-discrimination clauses which act to prevent the music streaming service from favouring music content based on price, for example, by giving more prominence to cheaper music.

However, given the current ‘full catalogue’ business model of music streaming – consumers expect to access every major’s repertoire on each streaming service – there is no credible alternative to each major’s catalogue. Taking this into account, our view is that the nature of competition between record companies to supply music to music streaming services is weak but would remain weak even absent the combined effect of the contractual clauses we identified as being potentially problematic. Whilst a slight strengthening of competition might result from the removal of these clauses (individually or in combination), it is not clear any improvement would be more than marginal.

Innovation is intrinsic to a healthy, competitive market and we therefore take seriously any suggestion that innovation has been hindered. We have therefore also assessed the impact of contractual clauses on how music services compete with each other in terms of innovation. To introduce innovations or changes to services, the music streaming services typically need to agree with the majors to amend existing contracts, which we heard can be a long process which may slow the pace of innovation.

We found examples of substantial innovation by music streaming services, both in terms of the services, such as the introduction of high-quality audio, and in the price plans available. But we were also given a few examples of innovations that were slow to market because of the complex negotiations needed to secure licensing agreements. There is a risk that contractual restrictions may contribute to the slower development of such innovations than might otherwise be expected or, potentially, preclude innovation altogether.

While potential competition concerns have been raised with us about the effect of agreements between the majors and music streaming services, we are not persuaded that changing the contractual clauses would significantly increase innovation. Rather, the problem appears to relate to the need for music streaming services to agree with multiple rightsholders on what terms (financial or otherwise) they can use their content, including in new and innovative ways. It is the sheer volume and complexity of these negotiations that appear to be the main barrier to even greater innovation. However, these negotiations appear to be an inherent part of the licensing process – with the financial terms negotiated depending on the features agreed.

Competition between music streaming services is currently delivering good outcomes for consumers, but concerns may arise in future

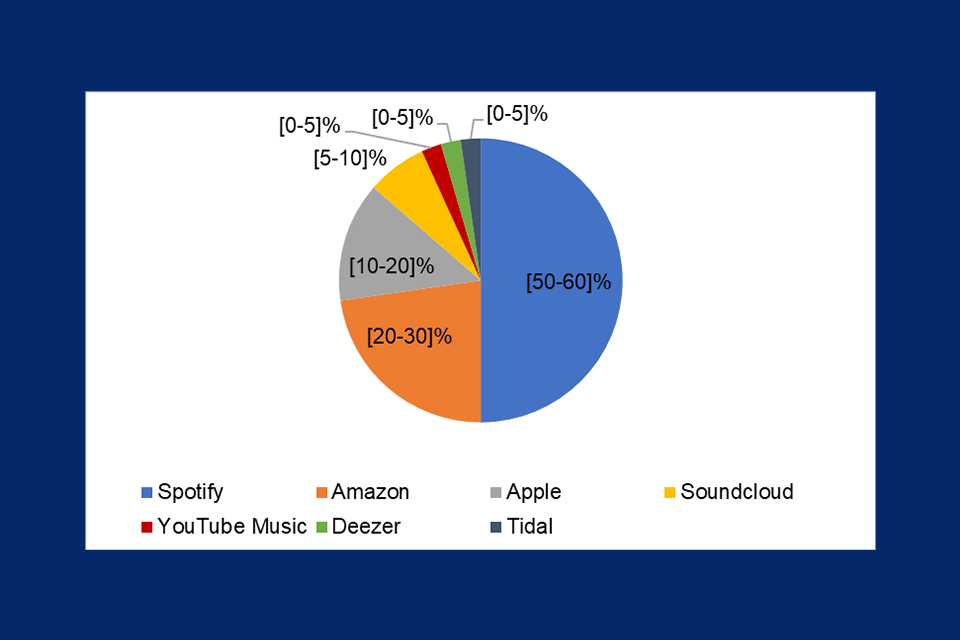

The music streaming services market is concentrated with a few larger streaming services such as Spotify, Apple, Amazon, and YouTube (which is part of Google), alongside a range of other smaller providers. Spotify has the largest number of monthly active users by some distance, as shown in the graph below. Music streaming services are popular with consumers and have grown rapidly – between 2019 and 2021 the number of monthly active users of music streaming services increased from 32 million to 39 million. Despite the strong presence of large, well-known firms in the market, and the number of active users increasing, music streaming services are not making sustained, excess profits: indeed, our analysis has shown that many services have low or negative operating margins.

Share of UK Monthly Active Users by music streaming service in December 2021, excluding YouTube’s UUC platform

Alt text: Figure showing the percentage share of UK Monthly Active Users by music streaming service in December 2021, excluding YouTube’s UUC platform. It shows that Spotify has the largest share of Monthly Active Users [50-60]%, Amazon has [20-30]%, Apple [10-20]%, SoundCloud [5-10%]. YouTube Music, Deezer and Tidal each have [0-5]%

Source: CMA analysis of data from music streaming services.[footnote 7]

We have heard consistently that consumers demand access to a full catalogue of music. The result is that the main music streaming services effectively offer the same music content to consumers. Competition between the services, therefore, anchors around offering the best experience to consumers through good design, personalised playlists, and high-quality audio content, as well as through pricing plans. These services also now compete with one another by offering non-music content, such as podcasts.

For consumers, the monthly price of music streaming services is either free (ad-funded) or falling in real terms because the price of individual subscriptions has remained stable and not kept pace with inflation. Most services offer a range of price plans, including family and student plans, as well as free ad-funded tiers. Streaming services are also frequently bundled with other services, such as mobile phone subscriptions, and accessed via a range of devices, including smart speakers.

Alt text: Graphic saying in real terms, prices have fallen for consumers by 22%

Recorded music is now also costing consumers less overall compared to when CDs and other physical formats were more popular, as indicated by UK recorded music revenues falling by around 40% from £1.9 billion in 2001 to £1.1 billion in 2021 in real terms.

In a market that is expanding, music streaming services mainly compete for new consumers, rather than encouraging existing customers to switch to their streaming services. However, music streaming services with ad-funded plans do actively seek to get customers to upgrade to a paid-for service.

Our analysis shows that consumers cancel their service at above 4% a month for the major streaming services. Cancellation might occur because free trials are coming to an end, the user is switching to another service, or because the user is no longer using any streaming service. The current data on why consumers may cancel their services is limited, but it suggests that the most cited reasons are consumers not being able to afford the service or not using it enough.[footnote 8]

Switching between music streaming services might be challenging if consumers are concerned that they will lose access to their favourite playlists. There are some nascent music data portability services that support switching, but demand for them is currently low. Low switching rates are not necessarily a dynamic that causes immediate concern - for example, in a growing market. However, as the number of new premium users to compete for declines in future, there is a risk that prices for music streaming services will rise significantly for consumers or there may be a deterioration in the quality of services, if there isn’t a significant threat of switching. Therefore, as the market reaches maturity we would be concerned if we did not see more vigorous competition between streaming services (for example, through enhanced efforts to make it seamless for consumers to switch and port their playlists or musical preferences). Higher rates of switching would imply consumers exercising choice (and hence competition), although the lack of switching by itself is not conclusive evidence of a lack of competition.

With more music available, tools that help consumers discover new music are more important. Streaming services compete in bringing music to consumers’ attention and promoting new artists and songs. We have found that while the majority of tracks listed on the top new music discovery playlists are licensed by the majors, the proportion is lower than the majors’ combined share of total streams. This suggests that artists that are not signed to a major do have reasonable opportunities to reach new listeners via discovery playlists and more generally the streaming services have told us that they design their music recommendation systems with a focus on listener engagement and user satisfaction.

Overall, whilst music streaming services are currently delivering good outcomes for consumers, it is imperative for a sustainable and vibrant market that services can effectively compete with one another, and we would have concerns in future if we saw a reduction in competition – for example, if majors sought commitments from streaming platforms to exclude competitors (large or small) from discovery or search elements of their service.

There is a ‘value gap’ between what YouTube and other music streaming providers pay to rightsholders but it currently amounts to less than 0.5% of UK recorded music revenues

UUC platforms allow consumers to access music content uploaded by users, artists and labels for free (but often with ads), in some cases coupled with other content such as entertainment videos. These services differ from music streaming services because any user can upload content, which may include copyrighted material which they may or may not have permission to share. Sometimes this content can appear on these platforms before a licence has been agreed with rightsholders.

Alt text: Image showing a consumer streaming music

UUC platforms have some protection in law through a ‘safe harbour’ provision which limits the liability they have for hosting illegal content uploaded by users in some circumstances. However, once they become aware that content is available without permission from rightsholders, they must remove it or, as is more often the case, allow the rightsholder to grant permission and monetise the content, for example by sharing ad revenues.

A range of music companies, artists and songwriters have been concerned that the asymmetry in the legal regime may result in a loss of revenues (often called the ‘value gap’) for the music industry. In particular, there is concern that the safe harbour provisions give UUC platforms greater bargaining power over rightsholders, leading to rightsholders having to agree worse terms than they would otherwise.

To understand whether a value gap exists and, if so, how significant the gap is, we have compared the amount that YouTube, as the largest UUC platform, pays out to rightsholders in comparison to Spotify’s ad-funded service. In 2017, YouTube’s ‘value gap’ in the UK – that is how much more it would have paid to rightsholders as a proportion of revenue from music content if it had paid them at the same rate as Spotify’s ad-funded service – was over 20 percentage points. However, this ‘gap’ has closed over time and in 2021 had fallen to significantly less than 5 percentage points, or less than £5 million. To put this figure into context, it is less than 0.5% of the £1,115 million total UK recorded music revenues in 2021. The evidence therefore suggests that the extent of YouTube’s ‘value gap’ has decreased in recent years.

Whilst YouTube is the largest UUC service and therefore very important in the market, there are other UUC platforms that take a different approach to licensing and may have less effective content management systems.

Some newer UUC platforms incorporate music into their offering, but do not offer a full streaming service. Examples of this include TikTok, a short-form video-sharing service, and Twitch, a longer-form live streaming service. These platforms, alongside YouTube, provide innovative services for consumers and potential opportunities for creators and music companies to earn further revenues in addition to those generated by music streaming.

The way these services use music differs from traditional music streaming services: they may use snippets of recordings or only offer specific genres of music, rather than a full catalogue on an on-demand basis. Therefore, it may not always be the case that the rates payable for these services will be comparable to music streaming services, which is an important factor when assessing if there is a ‘value gap’ between the 2 offerings. That said, we have heard examples of refusal to license or difficulties in agreeing licences that may indicate that safe harbour is among the factors in some commercial negotiations. We also consider that the quality of content management systems is important in ensuring that rightsholders are remunerated fairly for music content uploaded onto UUC platforms, and we have heard some newer emerging platforms may lag behind the more established platforms in this regard.

Meanwhile, since the exit of the UK from the EU, European legislation relevant to UUC has been amended such that it now requires UUC services using copyrighted content to make their ‘best efforts’ to seek permission to use that content. We note that the DCMS and IPO are monitoring the practical impact of these legislative changes on UUC services in the UK. We encourage them to take account of our broader findings in relation to UUC services when considering if legislative changes are required in the UK.

The market is evolving and innovating, but it is vital that it continues to deliver good outcomes for consumers

The music streaming market is changing rapidly, and further technological advances in the years to come may spark further changes to the way we listen to music. Our analysis shows that the market is on balance delivering good outcomes for consumers. However, we would have concerns and may intervene in the future if aspects of the market change in ways that harm consumers’ interests. For example, factors that may give rise to concerns could include:

- if future mergers or acquisitions affect the bargaining power of either music companies or music streaming services, which may in turn lead to worse outcomes for consumers with the CMA likely to pay particularly close attention to any such merger activity and to investigate whether it could lead to a substantial lessening of competition

- shifts in the way consumers access streaming services that influence their listening behaviour, for example if there is continued growth in the use of smart speakers, and whether this could exacerbate barriers to expansion of streaming services that do not have their own smart speaker ecosystem

- greater use of playlists, autoplay and recommendations for music discovery and consumption could be a cause of uncertainty and concern for consumers and artists if their operation, including any underlying algorithms, is not fair and transparent

- how difficult it is to switch between music streaming services and whether this limits the strength of competition between those services when the market is no longer growing

- if the level of innovation on the part of streaming services were to decrease; or if innovations that would benefit consumers were to be prohibited by music companies; or if consumers were to be disadvantaged in other ways, including through significantly higher prices

-

Data published by Ofcom (2022), Media Nations: UK 2022. ↩

-

As described in Chapter 5 of this report, a number of our findings on artists will also relate to songwriters. Issues specific to songwriters are considered in more detail below. ↩

-

This pie chart is for illustrative purposes only. These figures are provided in a 5% range where the figure is below 10%, and a 10% range where the figure is between 10% and 100%. The midpoints of the ranges have been used to provide an illustration of relative size in the market. Where the sum of these midpoints does not equal 100%, we have scaled the pie chart so that the area segments represent the share of the sum of the midpoints. ↩

-

As these are only averages across all 3 majors, they do not show how the terms can vary significantly between artists, reflecting for example the different potential financial rewards and risks based on the characteristics of individual artists (including by genre, potential, and stage of career). ↩

-

Whilst the CMA analysis for 2021 is based on data from the largest music streaming services, the IPO research draws on a range of largely qualitative evidence and therefore (as the IPO research itself acknowledges) the IPO research estimate of the split of revenues for 2008 is only indicative. Therefore, comparison between the split between 2008 and 2021 should be treated with caution and taken to be indicative of the overall trend in the split over time rather than estimates of the exact quantum of change in the split. ↩

-

The conduct of UK CMOs (including the PRS) is governed by the CRM Regulations. The CRM Regulations designate a National Competent Authority (NCA) which is responsible for monitoring and enforcing compliance with the Regulations’ provisions. The NCA functions in the UK are undertaken through the IPO, which has published guidance on these regulations (see IPO (2021), Guidance on the Collective Management of Copyright (EU Directive) Regulations 2016). ↩

-

This pie chart is for illustrative purposes only. Monthly Active User shares only account for Spotify, YouTube Music, Apple, Amazon, Deezer, Soundcloud and Tidal which have a combined streaming share of over 99% according to CMA analysis of data provided by Official Charts. YouTube Music users include YouTube Music premium Monthly Active Viewers and YouTube Music ad-funded Daily Active Viewers, meaning this figure will provide an underestimation of YouTube Music’s actual users. These figures are provided in a 5% range where the figure is below 10%, and a 10% range where the figure is between 10% and 100%. The midpoints of the ranges have been used to provide an illustration of relative size in the market. Where the sum of these midpoints does not equal 100%, we have scaled the pie chart so that the area segments represent the share of the sum of the midpoints. ↩

-

This should be treated with caution, however, as only a small proportion of users who cancel respond to the cancellation survey used to collect this data. ↩