National Model Design Code: part 2 - guidance notes (html accessible version)

Updated 14 October 2021

Applies to England

Code content

Introduction

1. The following guidance note sets out possible contents for a design code, modelled on the ten characteristics of well-designed places set out in the National Design Guide.

2. It is based on the key characteristics of context, movement, nature, built form, identity, public space, and use. Other sections dealing with homes and buildings, resources and lifespan provide important considerations in achieving design quality and should be used to inform the content of local plans, design codes or guides depending on local circumstances. These themes are interconnected, and users of this coding process should be mindful about the ways that they interrelate.

3. When following this process of selecting and setting parameters, it is essential that decisions are being made directly in response to the analysis and visioning exercises outlined in the main document. This guidance note sets out the potential content of a design code that can be developed into clear and, where possible, measurable guidance, subject to the context and type of development. The content outlined provides both a framework and some sample content from which design codes can be developed and adapted, to address the particular context to which the code will be applied.

4. Each theme is divided into subsections, and in each case, we describe the parameter/ issue, why it is important and how it might be used in a design code. In some cases these parameters / issues will vary by area type, while others will be applied equally across the local area. Not all parameters are relevant to every circumstance. Flexibility in local design codes can be introduced by setting an acceptable range for a parameter or not coding for it at all. Effective design codes are:

- Simple, concise and specific and;

- Rely on visual and numerical information rather than detailed policy wording.

Figure 1. Structure

[Alt text: The image shows the structure of the guidance notes, with miniature pages set out in two columns of five, showing the ten sections of the document. Each section is given a different colour, shown by a strip down the side of each page:

- Mid tone purple: Context.

- Dark blue: Movement.

- Dark green: Nature.

- Light blue: Built Form.

- Light purple: Identity.

- Light green: Public Space.

- Light orange: Uses.

- Dark orange: Homes and Buildings.

- Dark raspberry: Resources.

- Dark purple: Lifespan. ]

Context

Introduction

5. The National Design Guide states that an understanding of the context, history and character of an area must influence the siting and design of new development. This context includes the immediate surroundings of the site, the neighbourhood in which it sits and the wider setting. This includes:

-

C.1: An understanding of how the scheme relates to the site and its local and wider context.

-

C.2: The value of the environment, heritage, history and culture.

C.1 Character studies

6. Character includes all of the elements that go to make a place, how it looks and feels, its geography and landscape, its noises and smells, activity, people and businesses. This character should be understood as a starting point for all development. Character can be understood at three levels; The area type in which the site sits, its surroundings and the features of the site.

C.1.i Defining Area Types

7. The Design Code applies to a set of area types as described in Section 1. These are areas of similar character that allow elements of the design code to be set out depending upon which area type a development is within. This is illustrated in Figure 2, and the settings would be determined locally.

8. The aim of the design code is to work towards a vision of what each area type needs to be. The starting point will, be to undertake a series of area type studies through a combination of site visits, historical analysis and work with maps. The settings for each of the area types need to be based on a) an analysis of the existing character of these areas and b) a visioning exercise. A standard work sheet (See Appendix) can be used for each area type to systematise data collection.

The image shows an example context map for the area surrounding a fictional development site in an imagined mid-sized town. The image relates to the preceeding text which outlines what components and features should be included.

[Alt text: The image is an infographic showing extracts of what an Area Type Worksheet could look like. The contents include:

- a diagram showing the average block size.

- photos of key architectural features and materials (in this case, red brick and prominent bay windows).

- A drawing showing the building line, set back and garden arrangement.

- A 3D plan showing heights and density.]

C.1.ii Site context

9. It is necessary to undertake a context study of the area surrounding the site and the wider area for a full understanding of the place in order to respond positively to its distinctive features. Well-designed buildings need to respect and enhance their built and natural environment surroundings whilst addressing local constraints, the vision for its area type and responding positively to new issues such as innovation and environmental sustainability.

C.1.iii Site assessments

10. Developments need to respond to the site and the opportunities that are there to develop local character and distinctiveness, as shown in Figures 3 and 4.

The image shows an example context map for the area surrounding a fictional development site in an imagined mid-sized town. The image relates to the preceeding text which outlines what components and features should be included.

A study of the surrounding area looking at the following:

- The network and hierarchy of surrounding streets.

- Public transport.

- Walking and cycling routes. Notable local buildings.

- The characteristics of the local community. Local shops and facilities.

- Views, vistas and landmarks, such as places of worship. Visual amenity and views.

- The grain of the area; variation in built form, street scene and roofscape.

- Landscape and natural features such as hedges, green spaces, trees and woodland.

- Boundary features such as walls, fences and hedges.

- Water features including groundwater, rivers, lakes, canals, flood risk and other water features.

- Topography and geology.

- The local building vernacular, architecture, proportion, façade pattern and proportion.

- Architectural details and materials such as the use of brick, stone or render for walls, slate or tile for roofs etc.

- Colours, textures, shapes and patterns.

The image shows an example context map for the area surrounding a fictional development site in an imagined mid-sized town. The image relates to the preceding text which outlines what components and features should be included.

- Access points: How these relate to local movement patterns, rights of way and routes to shops and schools.

- Orientation: The sun path and how it affects the site.

- Topography: Changing site levels.

- Drainage: Run-off and opportunities for water features and SuDS.

- Existing structures: Existing buildings and walls with opportunities for retention.

- Existing utilities: Existing infrastructure and services.

- Ground conditions: Contamination and fill.

- Noise and Air Quality: Traffic noise and fumes and disruptive uses.

- Landscape and ecology: Natural features and habitats such as trees, hedgerows, and other mature vegetation contributes to a sense of place and needs to be retained and enhanced.

- Water: Ponds, lakes and watercourses that can be incorporated as natural features including to possibly open-up and naturalise watercourses.

C.2 Cultural heritage

11. Well-designed development adds a new layer to the history of a site while enhancing and respecting its past, with the expectation that new development will be valued for its heritage in the future as heritage assets are today.

C.2.i Historic assessment

12. A study of the sites’ history can be done by in-depth analysis of the place, including historic maps, as set out in Historic England’s Understanding Place guidance. These include details such as former uses, natural features, cultural features, urban form, street patterns and place names. They can help explain features of the site and can be used as inspiration for new development, such as reinstating historic streets.

C.2.ii Heritage assets

13. Development should always take account of heritage assets within or close to the site as defined in the NPPF.

14. The character and distinctiveness of a place is created by the richness of the buildings that have been built up over time. Not just the individual buildings or monuments, but how they relate to each other and how they have contributed to the evolution of the place has a whole.

15. The presence of such historic character, either directly on the site, or nearby, should always be seen as an opportunity to add value to any development by helping to provide inspiration.

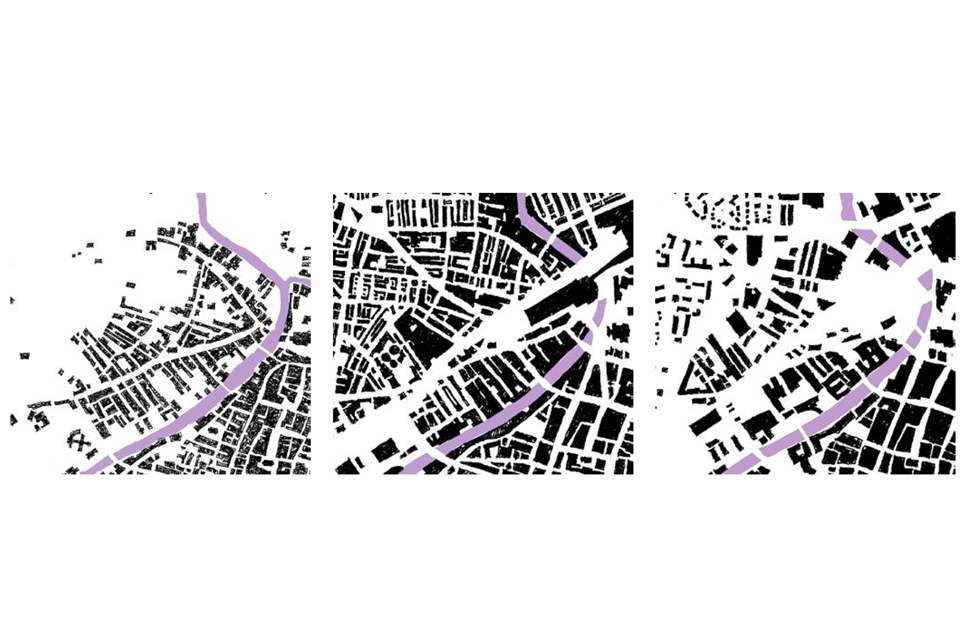

Figure 5. Historic map assessment: A historic assessment with plans from the 1800s, 1900s and the present day.

[Alt text: A series of three figure ground diagrams, where the buildings are coloured in black and the rest of the features are left blank. The three maps show the evolution of the urban form of a town from the 1800’s, through the 1900’s and up to the present day. The first image shows fine grain development in regular plots, taking up only half to two thirds of the frame. In the second image the whole frame is filled with buildings and we can see the arrival of a large train station. In the final image some of the fine grain development has been replaced with larger blocks and there are empty spaces where the built form has been fractured.]

Check list: Context

Local design codes should consider:

C.1 Character studies.

- Creating an area type matrix showing how the contents of the code relate to each area type.

- The preparation of context studies to inform the design of individual sites.

C.2 Cultural heritage.

- Historical assessments that can be used as a foundation for new development.

- Heritage assets and conservation area details that may influence the form of development and the relationship of these issues to the design code.

Movement

Introduction

16. The National Design Guide says that a well-designed place is accessible and easy to move around (p22-25). For movement, this means:

- M.1: A connected network for all modes of transport;

- M.2: Active travel and;

- M.3: Well-considered parking, servicing, and utilities infrastructure for all modes and users.

A series of model design parameters may be coded for each of these, as identified on the following pages.

M.1 - A connected network

17. A connected network and hierarchy of routes for all modes of transport form the circulatory system of any settlement and its design will determine how easy and safe it is to get around for all and how it links destinations to public transport. These issues are particularly important when coding for large sites but may also influence local design codes for smaller infill sites and their physical connectivity.

M.1.i The street network

18. The street network is important because it sets a long-lasting framework for moving around. In most cases, it will outlive the buildings it originally served.

19. A connected street network is one that provides a variety and choice of streets for moving around a place. It is direct, allowing people to make efficient journeys. Direct routes make walking and cycling more attractive and increase activity, making the streets feel safer and more attractive. Connected street networks form the basis of most of our beautiful and well-used places. They are robust, flexible, consider environmental impacts and have been shown to stand the test of time.

20. In a well-connected network, each street has more than one connection to another street. This applies both within a development or local area and in relation to streets outside it. Culs-de-sac are only found at the tertiary level of street type (see P1:3) for accessing development rather than for wider movement.

21. Permeability for different users, such as cars or delivery vehicles, can be controlled by measures within the street space, for instance, to prevent through movement or limit access to certain times of the day.

22. Consideration needs to be given to safety and security issues in respect of street layouts and footways, especially in areas in which a large number of people gather or pass through. Passive surveillance of the street, good lighting and high levels of street activity are desirable to deter criminal behaviour and to ensure people feel safe and secure using the street at all times.

23. Connected street networks may be linked to coding for street hierarchy, street types and public spaces (see P1).

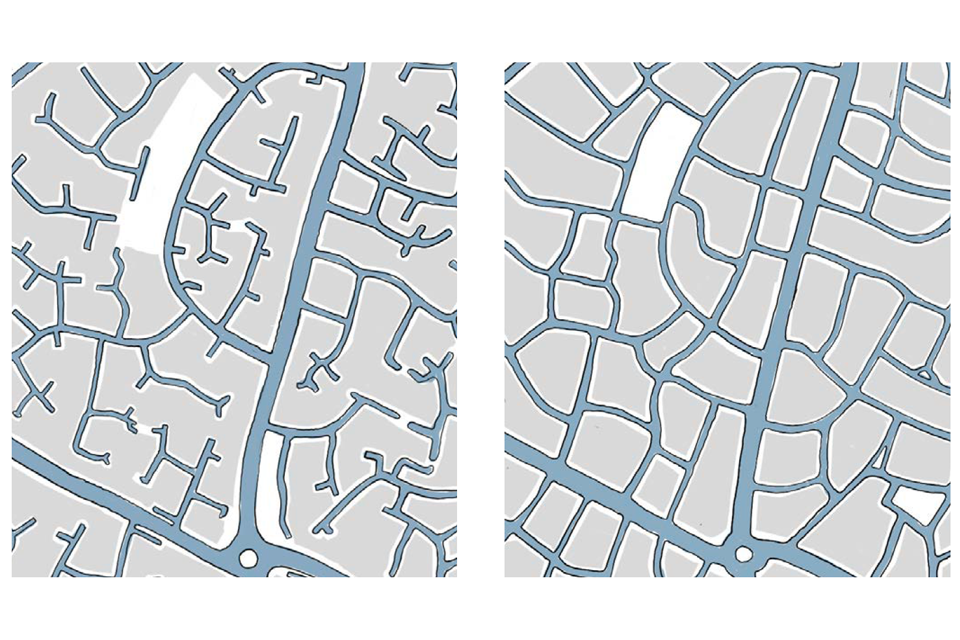

Figure 6. Connected Street Networks: A connected network of streets reduces walking distances.

[Alt text: Two images showing a simplified top down plan of a residential neighbourhood. The first image shows a series of cul-de-sacs or dead ends branching off from the primary and secondary streets - a poorly connected street network. The second image shows the same place, but with all the smaller streets connecting into one another - a connected network, which will be easier to navigate on foot.]

M.1.ii Public transport

24. Access to public transport is key to providing people with choice for everyday journeys beyond the immediate neighbourhood, such as to town centres, schools and employment locations. Good access to public transport helps reduce reliance on the private car.

25. A site or location has good public transport accessibility when dwellings have a public transport stop within walking distance.

26. The distances that people are prepared to walk from their dwelling to reach public transport are determined by the nature and quality of the public transport service, how attractive and safe the walk feels, and the total length of their journey. Generally, people are prepared to walk further to a railway station or tram stop (10 minutes) than to a bus stop (5 minutes).

27. Accessibility to public transport may be linked to other coding on mix of uses, local amenities, housing types, densities, and parking arrangements.

Figure 7. Walking Isochrone Around Public Transport Stops:

Walking distances can be assessed approximately by drawing circles to show the potential catchment area of new or existing public transport. It is important to take account of the actual walking distance (walking isochrone) which will be smaller, particularly where there are barriers to movement – for instance lack of adequate lighting and wayfinding, absence of green spaces, lack of good-quality and accessible footways, high-traffic routes such as busy road or a railway line.

[Alt text: This is a top down plan showing “isochrones” in dark blue shading. An isochrone illustrates the distance that can be walked outwards from a central point in a finite period of time, for example, 5 minutes. The image illustrates the text for figure 8 which talks about walking isochrones around public transport stops, and the barriers to movement that can make them smaller.]

Figure 8. PTAL Plan: An example of a public transport accessibility level plan for Croydon.

[Alt text: This is an extract from London’s interactive online “PTAL Plan” which shows the level of public transport accessibility for different places using a graduated colour system. This extract focuses on Croydon and the surrounding area. Dark red colouring over the centre of Croydon shows good public transport accessibility, while outer areas coloured in blue indicate poorer provision of public transport.]

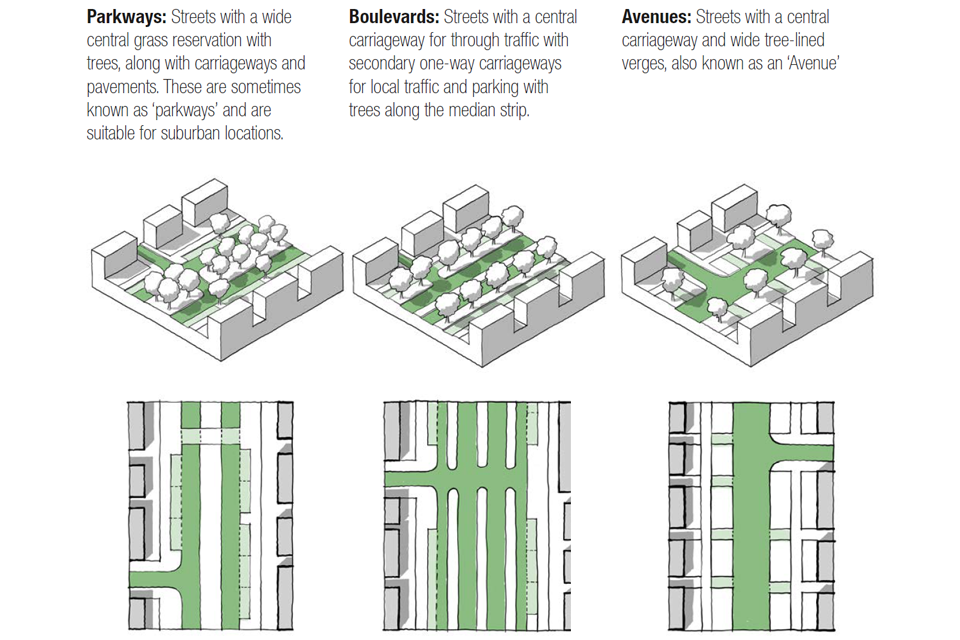

M.1.iii Street hierarchy

28. The design of the street network plays an important role in determining how it is used. Different streets play different roles in a place depending on the movement upon them, the built form and uses around them and the design of the street space itself, including any natural features, landscaping, lighting and wayfinding.

29. A design code may categorise the streets in a network as different street types. Each street type has a distinct function in terms of both movement and place that will vary according to the area type. Movement includes all modes, walking, cycling, public transport and motor vehicles.

30. Manual for Streets editions 1& 2 define common street types and functions, which this code seeks to align with. These street types include multifunctional streets and spaces; arterial routes and high streets; relief road/ring road; boulevards; high streets and residential streets. All have different place and movement functions. The street hierarchy below includes these street types together with other street types that may form part of a design code.

31. Coding may also define the range of street types that are appropriate for a local area or large site. Some common street types associated with this street hierarchy are set out in the Public Space section. All street types should enable safe and secure movement for everyone, including mobility impaired people, visually impaired people, and people with non-visible disabilities.

Figure 9. Street Hierarchy: A typical neighbourhood street hierarchy. All of these streets would include frontage access.

[Alt text: This is a highly simplified top down plan of a residential area, showing a number of different types of street in different widths and strokes of dark blue lines. The image illustrates the following text on street hierarchy, which describes different types of street and their role within a neighbourhood:

-

Primary street: Arterial, ring road or relief road with dedicated lanes for cycles and public transport, where possible.

-

High Street: Primary or Secondary street that acts as a focus for retail and other services.

-

Secondary Street: Mainly carry local traffic and provide access into neighbourhoods; they are often the location of schools and community facilities and may also be residential streets in themselves.

-

Local Street: Residential streets with managed traffic flows to prioritise active travel. They provide access to homes and support active travel, social interaction and health and wellbeing.

-

Tertiary street: These are used for servicing or for access to small groups or clusters of homes. They can be lanes, mews courts, alleyways or cul-de-sacs.

-

Multi-functional streets and other spaces: High Streets and secondary streets are at the centre of public life and support a wide range of activity. They can prioritise pedestrian and cycle movement while making it easy to get to their edges and beyond by public transport.]

M.2 Active travel

32. ‘Active travel’ refers to non-motorised and sustainable forms of transport, primarily walking and cycling. Prioritising active travel is about making walking and cycling easy, comfortable and attractive for all users, so they are seen as genuine choices for travel on local journeys. Coding for active travel is based on the user hierarchy from Manual for Streets. This sets out that in designing streets, the needs of pedestrians and cyclists should be considered first, then public transport, service and emergency vehicles and only then motor vehicles.

M.2.i Walking and cycling routes

33. Coding should reflect the aim that walking and cycling should be the first choice for short local journeys, particularly those of 5 miles or less.

34. For local journeys, this means creating continuous, clear, relatively direct and attractive walking and cycling routes both within a large site and into the surroundings. Following desire lines can help make routes clearer. Good sightlines aid wayfinding. They need to be well-lit, well-surfaced and maintained, and overlooked by buildings, as people feel safer on streets and in spaces where there are other people around.

35. Streets should be designed to be inclusive and cater to the needs of all road users as far as possible, in particular, considering the needs that may relate to disability, age, gender and maternity.

36. This is relevant to all street types. Designing a street so that everyone can use it benefits the whole community. Accessibility needs to be designed in from the start, as a ‘golden thread’ running through the scheme. This includes considerations such as minimum footway widths, placement of street furniture, frequency and type of crossing points, and so on, forming a basic part of the design process. Walking and cycling routes are also linked to coding for street types, parking and public spaces and through green infrastructure routes.

Figure 10. Low Traffic Neighbourhoods. On existing streets, Low Traffic Neighbourhoods preserve a connected street network for walking and cycling but prevent rat-running through traffic. This promotes walking and cycling and reduced car use. However, care is needed to ensure that displaced traffic doesn’t cause problems on neighbouring streets beyond the neighbourhood.

[Alt text: Two illustrative photographs.

The first shows a shared surface street in Thicket Mead, Midsommer Norton. The view looks down a paved road fronted onto by two storey houses. There is a level paved surface, with pavements distinguished from the central shared space with different paving and bollards.

The second shows a road in Waltham Forest that has been redesigned to give pedestrians and cyclists higher priority. The street has been remodelled, with much wider pavements, integrated street trees and a thinner strip of road surface at the same level as the pavement. The street is busy with pedestrians, who are walking both on the pavements and on the tarmac strip. A lady with a push-chair walks in the foreground of the image.]

Figure 11. Cycle Routes: Cycles should be separated from vehicles where possible.

[Alt text: This is a line drawing of a street section, showing how cycle lanes can be separated from the road. Reading from left to right it shows:

- A raised pavement with two figures walking.

- A cycle path at a lower level with a cyclist riding along.

- A generous gap at a raised level.

- A road at a lower level, with a car driving along it.]

M.2.ii Junctions and crossings

37. The way that streets join to each other and the way that people are able to cross streets and access points all have an important influence on walking and cycling.

38. The choice of junctions also influences where built form may be positioned and so the quality of the street as a public space.

39. All junctions and crossings need to be safe, convenient and attractive for all users.

40. Formal crossing facilities may be used on all street types, but may be particularly appropriate on primary streets and high streets. Siting a crossing on the pedestrian or cycle desire line will help to promote active travel and reduce accident risks by enabling a direct route, where people are more likely to use designated crossings. Manual for Streets sets out further detail on different types of crossing that can be appropriate.

41. Design codes may define appropriate junction types to manage vehicular priority and permeability on a connected street network and to promote active travel.

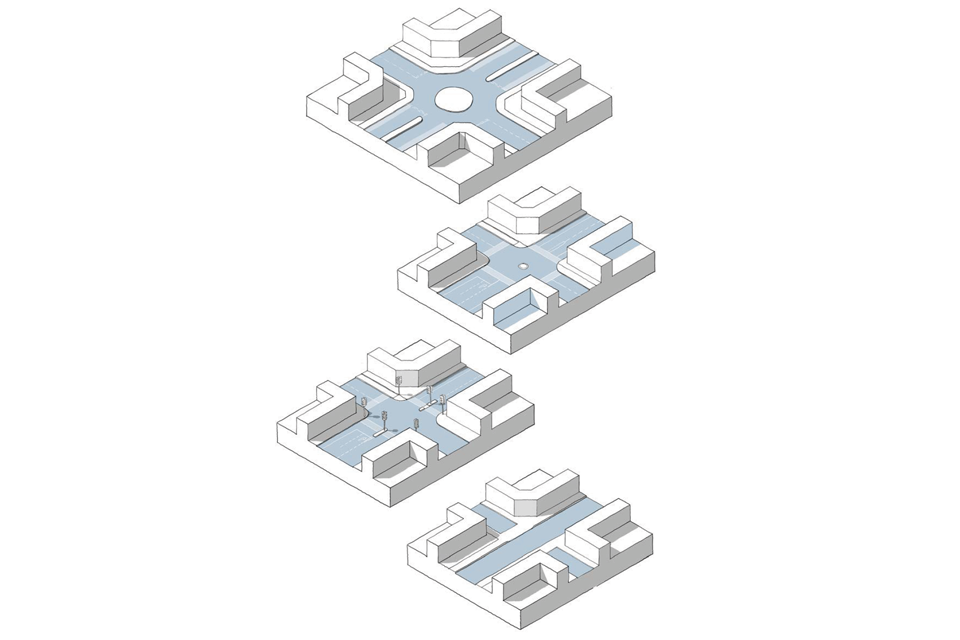

Four illustrative 3D line drawings showing different types of junction. The following text describes what is being illustrated in each case:

Roundabouts: Maintain traffic flows and speeds but do not provide well for cyclists and pedestrians and require more land than other junction types.

Mini Roundabouts: Manage traffic priority on junctions between primary, secondary and high streets in the built-up area.

Traffic signals: These will be dependent on the vehicle and pedestrian flow. They allow direct crossing routes for pedestrians and should incorporate pedestrian and cycle facilities wherever possible.

Simple junctions: Give way priority or unmarked junctions are appropriate between local streets and all other types of street.

M.3 Parking and servicing

M.3.i Car parking

42. Car parking affects the quality of a place, both visually and in terms of how it is used, particularly by pedestrians.

43. Parking standards are set out in the local plan. Maximum parking standards can be considered in circumstances where there is a clear and compelling justification. Design codes are concerned with the design of parking and its impact on the quality of place. They may identify appropriate parking options for area types, street types and building types and detailed design requirements associated with them.

44. Well-considered parking is convenient, safe and attractive to use. It is also well integrated into streets, blocks and plots, takes account of access to electric charging points and does not dominate the local environment.

45. The arrangement of parking may vary between different area types. It may also be influenced by the design of surrounding streets as set out in Section M1 above and public transport accessibility.

Figure 13. Residential Parking Options:

[Alt text: This is a 3D line drawing of a residential neighbourhood, showing one block and sections of a couple of surrounding blocks. It illustrates a number of residential parking options which are described in the following captions. These are split into “allocated” and “unallocated”. ]

Unallocated parking

Car barns: Decked parking structures. These may be free-standing multi-level parking structures or could include ground- level parking with a decked communal amenity space above.

On-street: On-street parking can be in defined bays with limited runs interspersed with pavement build- outs, planting and street trees. It may include chevron parking depending on the width of the street.

Parking courts: Parking courts within development blocks. These may be open or gated.

Allocated spaces

Within an integral garage: Certain housing types such as three-storey townhouses may include an integral garage. This normally means there is limited living accommodation at ground floor level. The ground floor may also be dominated by garage doors.

In the rear garden: In some circumstances rear parking courts may be appropriate providing they are secure, well-lit and overlooked and not detrimental to quality of life.

At the front of the property: This means that houses need to be set back at least 6m from the pavement. For terraced housing, most of the front garden may be taken up with parking but its impact may be screened by low evergreen hedges.

At the side of the property: For detached and semi- detached homes, the car may be accommodated to the side of the property, with one or more spaces and/or a garage tucked between buildings with overlooking for natural surveillance.

Unallocated parking

46. Unallocated spaces are an efficient way to provide parking. A scheme provides for the average rather than the maximum level of car ownership. Its flexibility of use enables it to accommodate residents and visitors throughout the day.

47. In some local areas, it may be possible to accommodate all parking requirements in this way. In high demand areas, it may be necessary to manage unallocated on-street parking through controlled parking zones and resident parking permits.

Allocated parking

48. Allocated parking is normally accommodated on plot or on site. It may also be provided on private land such as in parking courts or car barns.

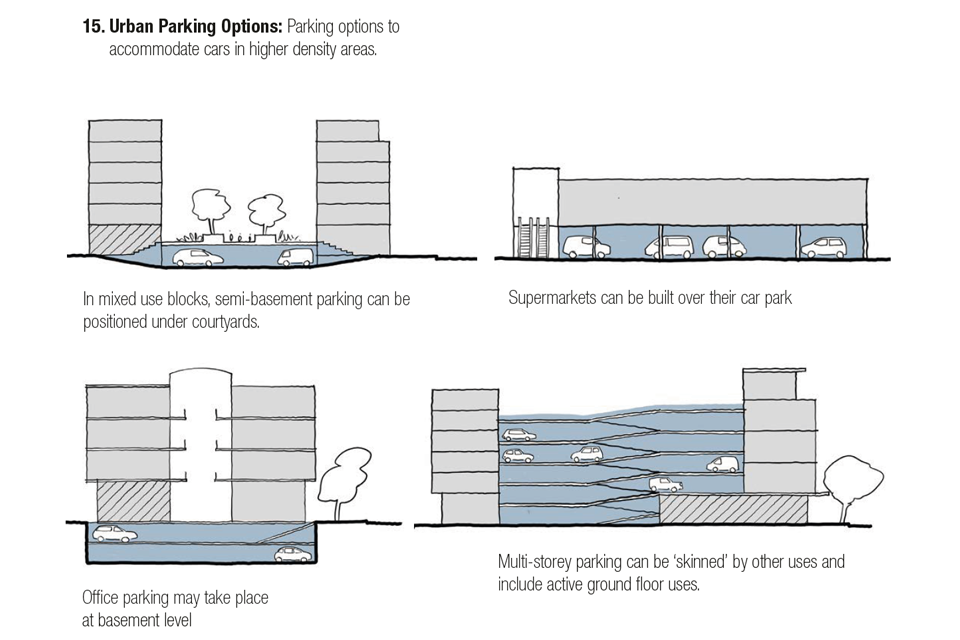

49. Non-residential parking may be integrated into the built form, either below ground in basements or semi-basements, or above ground using decks or multi-storey car parks.

50. Where large areas of surface-level parking are necessary, it may be located towards the rear of the plot or block, away from the main street frontage. Planting, including a grid of trees between bays, can reduce the visual impact. Short-term visitor parking may be positioned on-street or close to building frontages.

Illustrative drawing. A series of simplified sections showing how parking options can be accommodated in higher density areas. The following captions explain what is being illustrated in each case:

[Alt text: This is the first in a series of simplified sections showing how parking options can be accommodated in higher density areas. The following captions explain what is being illustrated in each case:

- In mixed use blocks, semi-basement parking can be positioned under courtyards.

- Office parking may take place at basement level.

- Supermarkets can be built over their car park.

- Multi-storey parking can be ‘skinned’ by other uses and include active ground floor uses. ]

M.3.ii Cycle parking

51. A design code may also define the appropriate locations and forms for cycle parking, in close proximity to homes and buildings, both for building occupants and for visitors.

52. Cycle parking for occupants must be secure if people are to use it. It also needs to be under cover to avoid problems with bad weather.

Illustrative photograph. A series of 4 photographs showing different cycle parking solutions. The following captions describe what is being shown in each instance.

[Alt text: Illustrative photograph.

This is the first in a series of 4 photographs showing different cycle parking solutions. The following captions describe what is being shown in each instance.

-

Public cycle parking: Visitor parking may be provided via cycle racks in the public realm that are prominently located and well supervised, provided that they do not obstruct pavements or desire lines.

-

Apartments: In apartment blocks cycle parking can be provided in apartments, provided the space is in addition to the Nationally Described Space Standards. It requires level access and an adequately sized lift. Communal bike stores may be provided externally, in basement car parks or in freestanding structures. These should be as near as possible to the entrance for convenience, and both the store and the individual bike stands should be lockable.

-

Housing: In lower density suburban housing bike parking can usually be provided within a garage or a separate structure within the garden. For terraced housing, provision for cycles needs to be made within the property, in the front garden or to the rear with access from a parking court. It is also possible to provide communal bike pods accommodating up to 10 cycles using a single parking bay.

-

Workspaces: In workspaces cycle parking may be provided via dedicated facilities within the building, possibly as part of a basement car park. This may be linked to showers and lockers or even a bike repair hub. ]

M.3.iii Services and utilities

53. New development needs to take into account a range of practical requirements for streets and public spaces such as servicing requirements, access to utilities and reinstatement of road surfaces. If these are not considered they can undermine the quality of space.

54. Design codes may include coding for servicing and utilities arrangements.

Emergency services

55. All developments need to be accessible to emergency vehicles. Sites with limited vehicle access points need to ensure that ambulances and fire tenders can gain access if one of the roads is blocked. This can be a particular problem with unregulated on-street parking.

Refuse collection

56. The road network needs to take account of access for refuse collection and emergency vehicles. The size of refuse collection vehicles varies between local authorities and depending on the waste collection system care needs to be taken to ensure that their turning requirements do not compromise the layout. Local authorities should also be mindful of the existing context to ensure local character and quality of place is not compromised by overestimating this requirement.

This is a 3D line drawing of a collection of residential houses. It shows the three different refuse collection options set out in the following captions.

In-curtilage Provision: This can be provided to the side or rear of the property in detached housing. For terraced housing, collection needs to either be from the rear or a bin store needs to be provided at the front.

Communal Provision: An alternative for terraced housing as well as for apartments is communal provision. Reference should be given to guidance on carry distances and distances to collection points.

Bring Points: An alternative is to use underground waste storage bins, although this requires a specialist collection vehicle.

Check list: Movement

Local design codes should consider:

M.1 Connected places

- The way in which new development contributes to the creation of an overlooked and well lit permeable street network.

- The provision of public transport and the distance of all dwellings from a stop.

- A framework plan indicating the street hierarchy for the district.

- Safety and security considerations in respect to the layout of streets and footways for all.

M.2 Active travel

- Encouraging walking and cycling and the design of cycle routes.

- Balancing the needs of cyclists, pedestrians with those of vehicles.

- A toolkit of street junctions, layouts in accordance with Manual for Streets.

- Guidance on multi-functional streets including the situations in which they can be used and their design principles.

M.3 Parking and servicing

- How to accommodate the local plan’s parking requirements including:

- Acceptable locations and design of unallocated parking.

- Accommodation of bays for disabled spaces, electric charging and car share.

- Position of on-plot parking. Guidance on the design of parking for other uses.

- Acceptable locations and design of unallocated parking.

- The design and location of cycle parking.

- The design of bins and refuse collection services.

Nature

Introduction

57. Development should enhance the natural as well as the built environment. Nature is essential for health and wellbeing, for biodiversity, shading and cooling, noise mitigation, air quality and mitigating flood risk as well as contributing to tackling the climate emergency. Nature is also central to the creation of beautiful places.

58. Design codes need to ensure that nature and the historic landscape is woven into the design of places. This may include the amount and type of open space, the response to flood risk and the protection, enhancement and promotion of biodiversity.

59. The design coding guidance will be updated to reflect policy changes that are anticipated to drive improvements to our natural environment. Government is committed in the 25 Year Environment Plan to embed a ‘net environmental gain’ principle for development to deliver environmental improvements locally and nationally and to green our towns and cities by creating and improving green infrastructure. Local Nature Recovery Strategies will have a role in identifying land that should be safeguarded for nature and a National Framework of Green Infrastructure Standards for blue and green infrastructure in development.

N.1 Green infrastructure

60. Green infrastructure is a network of multi-functional urban and rural green and blue space which is capable of delivering a wide range of environmental and quality of life benefits. It covers everything from country parks to green roofs and street trees. In terms of new development, the design code may specify levels of green infrastructure provision and guidance on design. The National Framework of Green Infrastructure Standards will provide further detail on principles to guide design.

N.1.i Network of spaces

61. There is a hierarchy of green spaces which play a distinctive role in terms of nature, leisure and quality of life. Urban greening factor tools can determine amounts of green space. Consideration needs to be given to the way that these spaces are linked to provide a network of multi-functional green space and natural features.

[Alt text: A set of 5 photographs showing different levels in the hierarchy of green spaces. The first picture shows Stanage Edge in the Peak District - a rocky outcrop and a popular hiking destination. The second shows a large green space in north Manchester that fronts onto the canal. The third shows Heaton Park in Manchester, a large formal park with slopes overlooking the city. The fourth shows a smaller green space within the Manchester University campus where students often eat lunch and congregate. The final image shows residents on a bench enjoying a park in Chelmsford. ]

The images relate to the following captions:

Rural areas: Around 90% of England lies outside urban areas including pasture and arable land, forests, moors, wetland, natural spaces and National Parks and Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

Natural spaces: Within built-up areas these include land that has never been developed as well as formerly developed sites that have been reclaimed by nature. They include canals, rivers, former railway lines, roadside verges and other transitionary land that form important green corridors.

Parks and formal green spaces: Most settlements have a legacy of parks and other public green spaces like sports pitches, recreation grounds, and cemeteries.

Semi-public spaces: Many institutions like schools and churches are custodians of green spaces.

Squares, village greens and pocket parks: At the neighbourhood level there are smaller areas of green space that are used for local recreation and play.

Figure 17. Hierarchy of Green Spaces.

[Alt text: A series of 6 photographs showing further examples of green spaces that sit within the hierarchy of green space.

The first shows a row of lush mature trees growing from a wide grassy strip between two sides of the street on Highgate Road in London.

The second shows a beautiful communal garden in the Accordia development in Cambridge with raised planters that double as benches, a small stand of trees and lots of well established planting.

The third image shows a shared allotment in Levenshulme, where residents have planted vegetables in raised beds surrounded by wildflowers.

The fourth shows the private and communal gardens of the Malings development in Newcastle. Over the wooden fences we can see an array of plants.

The fifth shows the generous balconies of Timekeepers Square in Salford, where residents are evidently using the space - we can see planters, outdoor furniture and hanging baskets.

The final image shows the Deansgate tram stop in Manchester where a green wall has been installed. The plants have been arranged to create diagonal stripes of different green tones and are striking against the historic brickwork of the bridge and the cool glass surrounding the lift access.]

The images relate to the following captions:

Streets: Can include street trees, verges and planting areas that bring the benefits of green infrastructure to the heart of the built environment.

Communal gardens: Residential areas can include communal gardens within the block or at roof level.

Allotments and food growing: This can include community gardens, orchards, and urban farms.

Private gardens: Within built-up areas a large part of the land is private gardens that contribute significantly to biodiversity.

Balconies: External spaces in apartments can be important for wellbeing and nature.

Green walls and roofs: There are opportunities for greenery and biodiversity through green walls and roofs.

N.1.ii Open space provision

62. Local open space and wider green infrastructure provision is used for sport and play, multi-use and informal recreation spaces as well as being important for nature. Government is updating open space and recreation guidance on Accessibility to Natural Greenspace (ANGSt) to ensure there is sufficient high-quality open space in the right locations, that is attractive to users and is well managed and maintained.

63. The design code can consider the provision of new and enhanced green space as part of new development building in existing open space strategies and standards in the local plan. Approaches to setting open space standards include:

Population-based standards

64. The most common of these is the FIT standard (what is still often known as the National Playing Field Association 6 Acre Standard). This is widely used to define sports provision and informal outdoor space requirements. The provision of new and enhanced outdoor sports facilities should be considered in order to meet locally defined needs.

65. It can be difficult to achieve at higher densities, and the design code may provide guidance on how this is to be interpreted. This could include an assessment of existing open space provision set against ward population data to assess the extent to which the standard is being met. New schemes may then be asked to contribute towards meeting any shortfall.

Accessible greenspace standards

66. An alternative is to look at the distance to different types of open space. Thus higher residential densities would not increase the amount of open space required, subject to its quality. The code would map each type of open space and show walking distance around them as circles and isochrones. This will highlight poorly served areas where new development may address the shortfall.

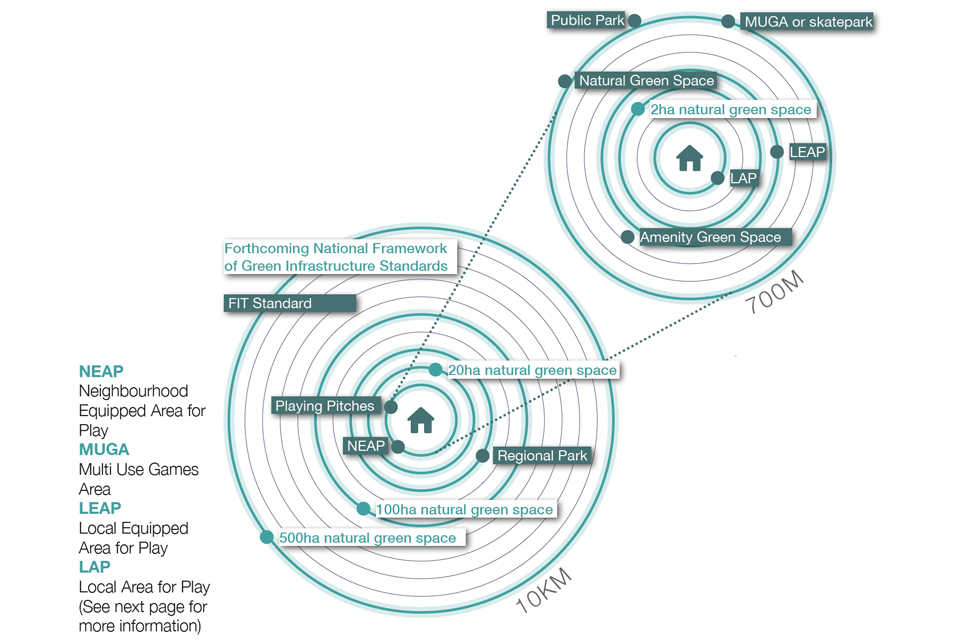

Figure 18. Open Space Accessibility Standards:

The forthcoming National Framework of Green Infrastructure Standards by Natural England will provide new standards for green infrastructure (ANGSt standards) suggesting that all people should have access to a natural green space close to home.

Benchmarks in the green infrastructure standards will include guidance on size/ distance criteria and the implications of residential densities on provision of green space, particularly in dense urban environments; and will be accompanied by a national map which will show where these criteria are not currently met, to help guide provision of green spaces to the places that need it most.

Communal areas, such as playgrounds, play areas, seating facilities need to be overlooked by nearby buildings, have safe and accessible routes for users and clear definition of boundaries to ensure they are secure.

Fields in Trust suggests that all homes should be within recommended distances to parks, playing pitches, NEAPs (Neighbourhood Equipped Area for Play), MUGAs (Multi Use Games Area), LEAPs (Local Equipped Area for Play) and LAPs (Local Area for Play).

[Alt text: Illustrative diagram.

This is a complex diagram which does not lend itself well to written translation, but is intended to illustrate the various open space accessibility standards discussed in the preceding text.

The image is set up as two sets of concentric circles around a simplified infographic of a house. One set has a range of 100-700 meters and shows all the types of green spaces that should be accessible to people within that range: A local area for play (LAP), a local equipped area for play (LEAP), an amenity green space, a natural green space, a multi use games area (MUGA) or skatepark and a public park.

The other set of concentric circles has a range of 1-10 kilometers and shows all the types of green space that should be accessible within that distance range: a neighbourhood equipped area for play (NEAP), playing pitches, a regional park, a natural green space of over 20 hectares, plus natural green spaces of over 100 hectares and 500 hectares at further distances. ]

N.1.iii Open space design

67. The way in which spaces are designed is crucial to their success. The design considerations vary with the type of space, a formal park being very different to a large natural open space. The situation where the design code is likely to be most relevant is in the design of new smaller open space within new development. In this case, the following principles are important:

Figure 19. Types of Play Space:

Policy for play areas is based on three levels of provision for play friendly spaces that are accessible and inclusive for all. This could include other bespoke approaches such as adventure play, play for older children including teen play, the concept of doorstep play in higher density housing and integrated approaches to play with nature and the built environment. These relate to the size and level of equipment provided but also the age of the children for which it is designed. The three levels are:

-

Local Areas of Play (LAP), with a few fixed items of play near to the home.

-

Local Equipped Areas of Play (LEAP) With at least five pieces of equipment for slightly older children.

-

Neighbourhood Equipped Area of Play (NEAP) With at least eight pieces of equipment along with a Multi-use games area (MUGA) and/or a skate park/bike track.

[Alt text: Three 3D line drawings that illustrate different types of play space, explaining some of the terms used on the previous page. In each case the drawings show plenty of well integrated trees and biodiversity along with the play equipment when illustrating the preceding captions.]

This is a 3D line drawing that shows an open space surrounded by streets and houses on all sides. It illustrates the following principles of good open space design:

1. Boundary: Consideration needs to be given to whether the space is fenced and gated without interrupting wildlife networks.

2. Entrances: Access points and paths need to be conveniently located on desire lines for walking and cycling.

3. Surveillance: Open spaces need to be overseen from surrounding buildings, streets and public spaces.

4. Activity: Sufficient space needs to be provided for sports pitches and play areas to avoid conflict with other uses.

5. Maintenance: The design of the space needs to take account of maintenance and adoption requirements.

6. Ecology: Green spaces need to include areas that are nature-rich.

7. Access: Public open space needs to be accessible and welcoming to everyone.

8. Lighting: Needs to be considered for well-used footpaths and games areas but should avoid light spillage that causes nuisance and harms wildlife.

9. Allotments and community growing: need to consider community growing projects for food production, learning and community engagement on large developments.

N.2 Water and drainage

68. Managing water is an important element of a site’s response to nature. It can reduce flood risk and improve water quality while providing habitats and recreational activities and dealing with flooding when it happens.

N.2.i Working with water

69. Many sites will include water in some form, and the National Design Guide can provide guidance on maximising the benefits.

70. Development adjacent to existing water features, including rivers, lakes, canals, docks and wetlands has an important role to play in enhancing the value of blue infrastructure as public realm, habitat, ecological corridor and natural capital asset.

71. Buildings may face the water and leave a sufficient buffer zone to allow for watercourses and banks to be maintained and for current and potential future flood defences. Opportunities to create walking and cycling routes along watercourses where appropriate need to be encouraged.

72. Opening up culverts, reinstating meanders and restoring and naturalising river beds and banks can benefit wildlife and improve public access and flood attenuation.

This is a 3D line drawing of a set of buildings fronting onto a body of water. It illustrates a number of principles described in the preceding text.

N.2.ii Sustainable drainage

73. Sustainable drainage systems or SuDSmimic natural drainage in delivering effective surface water management, controlling surface water close to where it falls. They are designed to reduce the rate of rainwater run-off from new development, mitigating the risk of flooding elsewhere whilst delivering benefits for biodiversity, water quality and amenity. Ideally water needs to be captured for use on site for irrigation and non-potable uses. Where this is not possible schemes need to follow the hierarchy set out in guidance, by which water is:

- Allowed to infiltrate into the ground in a way that mimics natural drainage.

- Attenuated for gradual release to a water body.

- Released into a water sewer, highway drain, or another drainage system.

- Released into a combined sewer.

74. The approach to each site will depend on its density, the position of watercourses, the ground conditions including water permeability, contamination and the sensitivity of groundwater receptors.

75. SuDS need to be considered early in the design process to ensure ease of access for maintenance and efficient use of land by integrating them with other aspects of design such as public open space, biodiversity provision, and highways. Multi-functional SuDS need to be prioritised allowing for attenuation features which can also be used for biodiversity and recreation.

This is a 3D line drawing of a residential block surrounded by different areas of open space and green infrastructure features. It illustrates a range of sustainable drainage solutions, as set out in the following caption text:

1. Green roofs and walls: Provide capacity to hold and attenuate water run-off as well as ecological and leisure benefits.

2. Permeable surfacing: Surfaces that allow water to percolate into the ground including, natural surfaces, gravel and low traffic volume engineered road surfaces and hard- standings in front gardens.

3. Swales: Shallow channels that provide attenuation while also channelling water to other features such as ponds.

4. Rain capture: Water butts and other rainwater harvesting systems collect rainwater for use in gardens or for non-potable uses reducing water consumption.

5. Soakaways and filter drains: Shallow ditches and trenches filled with gravel or stones that collect uncontaminated water and allow it to percolate into the ground.

6. Retention tanks: In high density schemes water can be attenuated in underground structures.

7. Street tree planting: SuDS designed into highway provision can provide dual use benefits when integrated with street tree provision.

8. Rain gardens: Containers and ditches with native drought tolerant plants release water gradually and filter-out pollutants.

9. Basins and ponds: Attenuation ponds that are normally dry but fill during a rain event and then either store or gradually discharge water to the system.

10. Reedbeds and wetlands: Topography can be used to create wetlands that provide attenuation capacity as well as filtering out pollutants and providing habitat for wildlife.

N.2.iii Flood risk

76. Flood risk needs to be considered early in the design process based on an understanding of all sources of current and future flood risk and alongside other design factors.

77. The sequential test should be used to steer development away from flood risk areas. Where flood risk areas are unavoidable, development should be designed to ensure it will be safe from flooding throughout its lifetime, without increasing flood risk elsewhere.

78. Vulnerable uses need to be laid out and designed using flood avoidance measures such as:

- Locating buildings on the lowest risk parts of the site

- Raising finished floor levels above predicted flood levels

- Using upper storeys for habitable areas of housing, with ground floors used for less vulnerable or non-habitable uses (e.g. garages).

- Lower vulnerability uses should also be located and designed to avoid flooding. However, if flood risk is unavoidable, low vulnerability uses should incorporate resilience measures in accordance with the Property Flood Resilience Code of Practice to resist flood water and ensure they can recover quickly in the event of flooding.

80. Where the safety of development relies on emergency planning measures it should include safe, signposted access and escape routes in accordance with the ADEPT/EA guidance on flood risk emergency plans for new development. Wherever possible these routes need to remain dry, but as a minimum, they should be designed to ensure people will not be exposed to hazardous flooding. It may also be necessary to include a place of refuge above predicted flood levels.

81. All developments should seek to reduce flood risk. This could be through making more space for water, increasing infiltration, providing new or improved flood defences or through natural flood management techniques.

Figure 23. Flood Resilience Principles.

- Steer development away from flood risk areas

- Use flood avoidance measures Use flood resistance and recovery techniques

- Provide safe means of access, escape and refuge

- Seek to reduce flood risk

[Alt text: Illustrative CGI. An image produced by JTP Architects and the Environmental Design Studio showing housing that would be resilient to flooding. The scheme includes a “light touch” ground floor which allows water to pass through without displacing it to another location, habitable rooms elevated to first-floor and above and a resilient ground floor ‘garden room’ zone - a multiuse space that can be quickly adapted and cleaned post flood.]

N.3 Biodiversity

82. All new development needs to use, retain and improve existing habitats or create new habitats to achieve measurable gains for biodiversity. This includes landscaping and tree planting.

N.3.i Biodiversity net gain

83. Local Nature Recovery Strategies (LNRS) to map and identify opportunities to create and enhance local biodiversity will be included in the Environment Bill. These strategies are intended to assist developers in achieving biodiversity net gain and need to be referenced in the design code.

Figure 24. Biodiversity Net Gain: Development will be expected to produce a +10% increase in biodiversity.

[Alt text: Illustrative infographic. Two very simplified images. The first shows an area with a tree, plants, bird and bee. The second shows the same area with a house in the centre. There is also an additional tree, more plants and another bird. It is intended to illustrate the biodiversity net gain principle in the preceding text.]

The 1st photo shows a bee brick, a brick incorporating holes of different sizes to provide a nesting site for solitary bees. The 2nd image shows a "hedgehog highway" - a hedgehog sized hole in a wall to allow hedgehogs to move across their territories.

[Alt text: Illustrative photograph. This 1st photo shows a bee brick, a brick incorporating holes of different sizes to provide a nesting site for solitary bees. The 2nd image shows a “hedgehog highway” - a hedgehog sized hole in a wall to allow hedgehogs to move across their territories.]

84. Design codes will be expected to reflect the minimum 10% net increase in biodiversity compared to the situation prior to development. The broader environmental net gain approach includes wider beneficial environmental outcomes that can be delivered such as flood protection, recreation and improved water and air quality.

85. Natural assets such as ancient woodlands, designated sites, mature trees, and protected species should be protected and enhanced (where possible) in the design of the schemes. Priority habitats and priority species should also be considered within the design process.

86. A baseline assessment needs to be undertaken prior to development using the Natural England Biodiversity Metric 3.0 to measure the existing value of the site (this will become mandatory under the Environment Bill). The proposed post-development design will similarly be assessed to show a minimum 10% improvement (including any offsite provision where necessary)

N.3.ii Planning for biodiversity

87. The design code should be based on a hierarchy that first seeks to avoid damaging habitats, then to mitigate that damage and then, if this is not possible, to consider replacement habitats.

88. Measures using green/infiltration SuDS that improve water quality and create habitats should be included where possible.

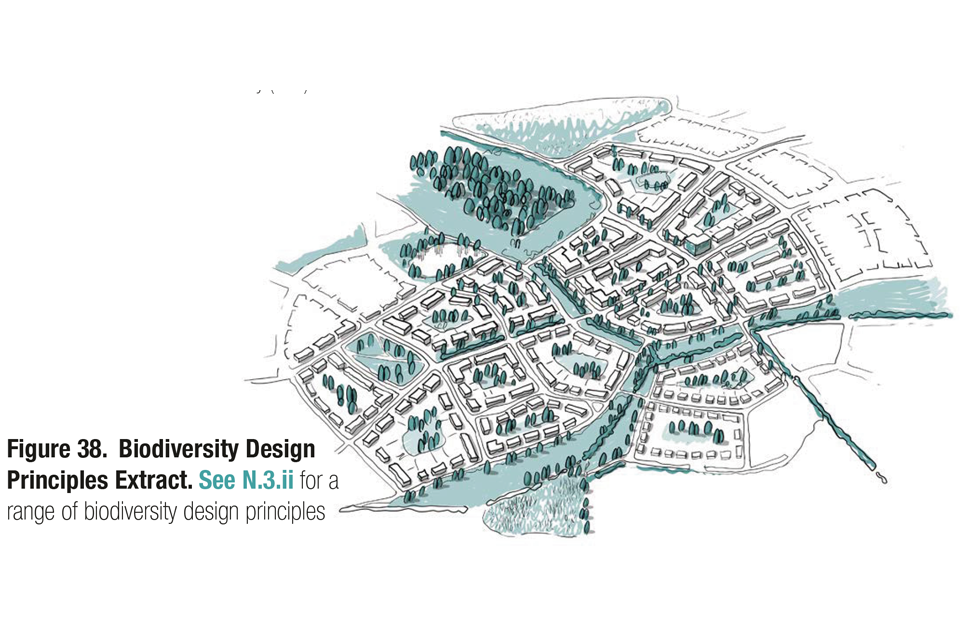

Figure 26. Biodiversity Design Principles:

Alt text: Illustrative drawing. This is a 3D line drawing showing a residential neighbourhood from above. It is comprised of a number of blocks of low to medium density development separated by areas of green open space. It illustrates the biodiversity design principles set out in the following captions:

-

Planting: To provide nectar, nuts, seeds, native vegetation and berries along with trees and shrubs, logs and stones. Native plant and tree species are generally, but not always, better for wildlife.

-

Creating habitats: Strategies need to be considered for creating natural habitats, for example, through use of trees, wildflowers and ponds as well as bat and bird boxes, bee bricks and bird bricks and hedgehog highways.

-

Enhancing habitats: Management of native planting, foraging grounds for bats, feeding grounds and wetlands for birds and forest floor habitats.

-

Ecological niches: Can create a range of ecological conditions from woodland transition zones to wetland areas and open grassland.

-

Existing features: Natural assets such as trees, woodlands, hedges, wetland areas and other natural features need to be retained and enhanced where possible.

-

Rivers: Restoration techniques create habitat and reduce flood risk.

-

Mosaics: A range of elements and structures as small patches of bare ground, tall flower-rich vegetation, or scattered trees and scrub to support a range of species and their life-cycles.

-

Trees and hedgerows: These should be incorporated into public realm and other open spaces as well as private development where appropriate.

-

SuDS and rain gardens: These can be designed to provide benefits to nature by including planting and habitat niches.

-

Ecological network: Masterplans should create an interconnected ecological network that encompasses everything from doorstep spaces and private gardens to the surrounding countryside.

-

Green roofs & walls: Green facades provide nesting opportunities and food for bees. Habitats can also be created on roofs and are especially beneficial for birds and insects.

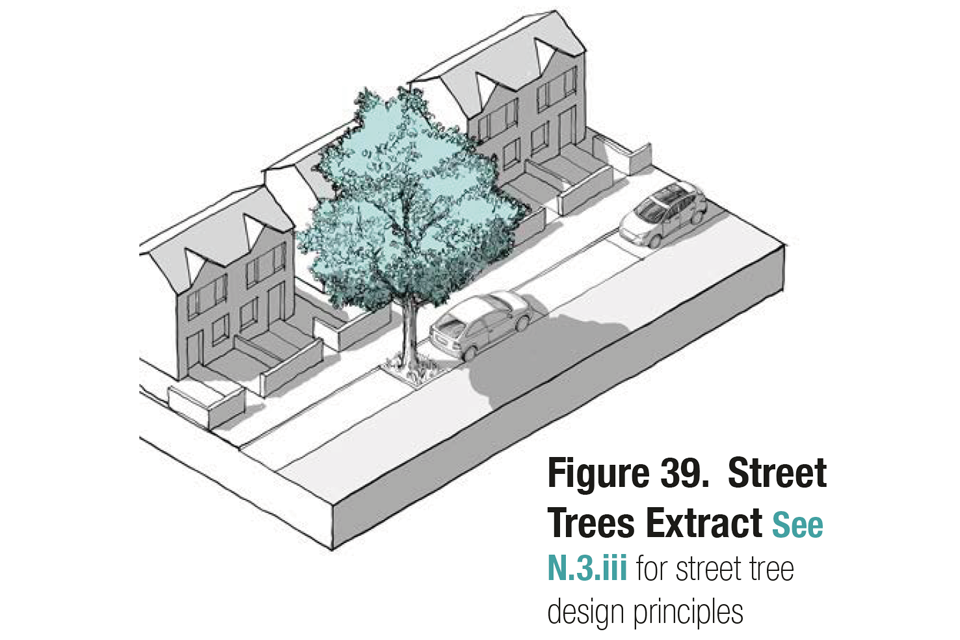

N.3.iii Street trees

89. Street trees and other landscape features in streetscapes provide habitat, shading, cooling, air quality improvements and carbon sequestration, as well as being a vital component of attractive places. It is the government’s intention that all new streets include trees and the Urban Tree Challenge Fund is planting 130,000 urban trees across England. Guidance on installation, management and maintenance is available in the Urban Tree Manual, and considerations include:

Species: Codes may include a list of species as a palette for use by developers including non-native species which can provide valuable habitat. These help to establish different area types and need to take account of local climate, shape, size, fruit and pollen. A variety of trees provides biodiversity and biosecurity resilience.

Position: Careful positioning to allow space for the mature tree without causing obstruction or interfering with property, infrastructure, street lighting or junction sightlines. This can be on median strips, verges or interspersed with parking bays but only on pavements where the mature tree will not block access.

Function: Ensure street trees and green infrastructure provide for a range of functions and benefits and sufficient to help improve air quality and reduce noise from the street network.

Services: Coordinating tree planting with utilities providers and service ducts early in the lifetime of a scheme can ensure that trees do not interfere with underground services.

Specification: Care is needed in heavily trafficked areas to avoid the compaction of the soil around the tree. Guidance on tree planting, pits, guards and other technical specifications are widely available and have a significant impact on the tree’s survival prospects.

This is a 3D line drawing of a residential street. A large mature street tree is integrated into an area of on street parking.

Check list: Nature

Local design codes should consider:

N.1 Green infrastructure

- The creation of a network of green spaces and other green infrastructure such as green corridors and street trees, which provide multiple benefits for biodiversity, nature, recreation, climate change resilience and support health and wellbeing.

- The provision of open space based on the government’s Open Space and Recreation Guidance and an open space framework plan.

- The provision of children’s play in accordance with national guidance including its location, size and design.

- Guidance on the design of green spaces.

- The use of greening factors to deliver quantifiable levels of greening.

N.2 Water and drainage

- Guidance on the design of development next to water.

- Performance standard and the design of sustainable drainage systems.

- Guidance on development within flood risk areas based on Environment Agency guidance including flood mitigation and resilience.

N.3 Biodiversity

- Implementation of the government’s Biodiversity Net Gain Policy and the Local Nature Recovery Strategies.

- The retention of natural features such as trees, woodlands and hedgerows and other ecological features.

- Guidance on design for biodiversity.

- The provision of street trees relating to types of streets plus the design, placement and species to be used.

Built form

Introduction

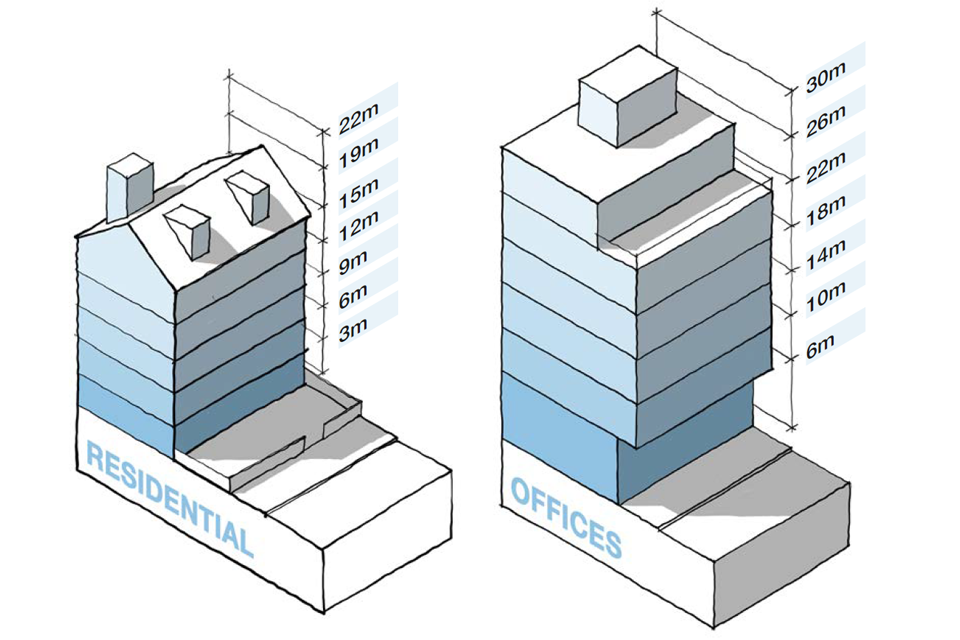

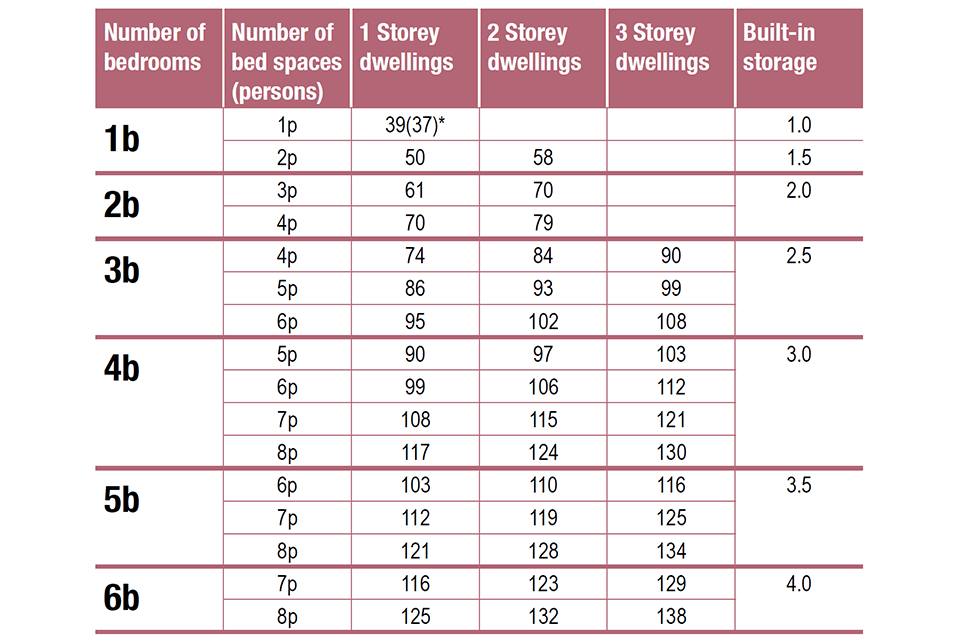

90. The National Design Guide defines the ‘built form’ of an area as the ‘three- dimensional pattern or arrangement of development blocks, streets, buildings and open spaces’ that make up any built-up area or development. It says that a well-designed place has a coherent form of development. For built form this means:

- A compact form of development

- Appropriate building types and forms

B.1 Compact form of development

91. A compact form of development is more likely to accommodate enough people to support shops, local facilities and viable public transport, maximise social interaction in a local area, and make it feel a safe, lively and attractive place. In this way, it may help to promote active travel to local facilities and services, so reducing dependence on the private car.

92. What is meant by compact will vary according to area type and context. A design code may define an appropriate measure of compactness for new development in relation to an area type.

B.1.i Density

93. Density is one indicator for how compact a development or place will be and how intensively it will be developed. However, in itself it is not a measure of how appropriate a particular development may be within an area type. For this it needs to be combined with coding for other design parameters, including those set out below.

Residential density

94. A design code may set out local densities or ranges of density, particularly on large sites with an average overall density, where local variations in density may be desirable in order to create a variety of identity without harming local character as set out in Historic England guidance.

Figure 28. Measuring density: A local variation in density creates a variety of built form character in Cambourne. Area A has 94 homes on 2.6 hectares – a net density or 36 dwellings per hectare (dph). Area B has 32 homes on 1.8 hectares, so is around 20 dph. Note the area measure runs to the back of each plot and the centre line of the roads.

[Alt text: Illustrative drawing. Shows a top down plan of an area of residential development and relates to the preceding text on measuring density. As highlighted in the text, one area of the plan is of a higher density (with more rows of terraces) than the other area (which has more detached and semi detached houses).]

Figure 29. Plot Ratio and Plot Coverage: The former is the ratio between site area and the total building floor area while the latter is the proportion of the site area occupied by buildings. These two measures can be combined to control development and should be used alongside good urban design principles. For instance, a Plot Ratio of 2 means that the floor area can be twice the site area while a Plot Coverage of 0.5 means that only half of the site area can be developed.

[Alt text: Illustrative drawing. The image relates to the preceding text on plot ratio and plot coverage. It is set out as a table with plot ratio along the right hand side and plot coverage along the top. The table is populated by a series of 3D line drawings, showing simplified height and massing options for buildings depending on their plot coverage and plot ratio. The drawing seeks to show the relationship between them. For example a plot coverage of 2, can be configured as a tower taking up a relatively small portion of a plot, with a plot ratio of 0.25. Or, it can be configured as a lower building, of only a few storeys, taking up the entire plot (a plot ratio of 1)]

95. For housing development, density can be measured using plot ratio, dwellings per hectare, or bed spaces per hectare. Density in dwellings per hectare may be measured using gross or net density. Design codes may consider the appropriate measure of density for a given situation.

Density for other uses

96. For non-residential or mixed-use development density can be measured by plot ratio or plot coverage. The former indicates how much of the site the building is able to occupy while the latter is the ratio of site area to the area of development.

97. A design code may set out local densities or ranges of density for non-residential or mixed-use development.

B.1.ii Whether buildings join

98. When buildings join to neighbouring buildings the form of development is more compact than when they do not. Freestanding buildings generally occupy wider plots, which affects both density and compactness.

99. Design codes may include coding that enables or prevents buildings from joining to each other, depending upon the area type. Alternatively, coding for building lines (see B2.2) may be used to achieve a similar outcome.

B.1.iii Building types and forms

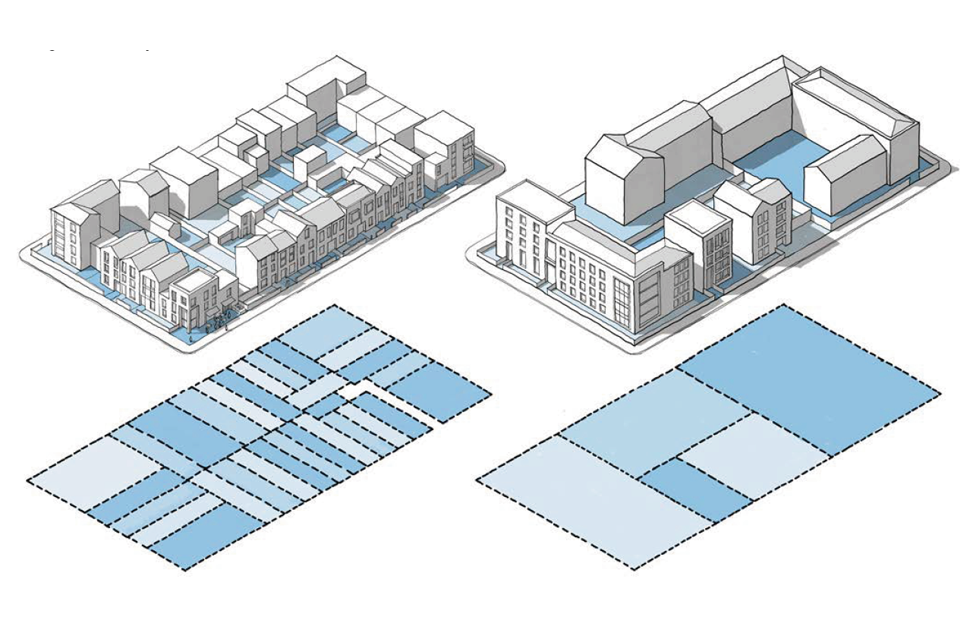

100. The character of an area is also influenced by the variety of building forms. This relates to the size and uniformity of the buildings. Large buildings may occupy an entire block, whereas the same area could be developed with a variety of smaller buildings. In many places it is the rhythm and variety of these smaller buildings that is intrinsic to the character of the area. While large buildings will be appropriate in places, an area made up entirely of large buildings can be dull.

101. This is referred to as urban grain and it derives from the size and configuration of plots. Masterplans need to indicate this plot structure, which together with the way that buildings join will determine the character of the development. Plot based masterplans can also be used to accommodate custom-build and self-build development (see section U2:2) with the Code parameters summarised in a plot passport, where relevant.

Figure 30. Buildings joining.

[Alt text: Illustrative drawing. This is a series of three 3D line drawings showing different configurations of a row of simplified houses. The first shows a row of terraces, the second shows two sets of semi-detached houses, the third shows a row of detached houses. The following captions explain the different party wall treatments in each instance:

-

Joining on both sides: Party walls on both sides leads to terraced housing.

-

Buildings joining on one side: Leads to semi-detached housing.

- Buildings not joining: Leads to detached housing. A code may also specify a set-off distance, say 1m, from plot boundaries. ]

Figure 31. Urban Grain: Blocks can be developed with buildings of different sizes, based on the arrangements of plots. A larger number of smaller buildings can create greater variety and visual interest.

[Alt text: Illustrative drawing.

This is a set of 3D line drawings of two different block structures, with their plot arrangement set out underneath in plan form. The first 3D block drawing shows a rectangular block, with numerous buildings with narrow facades and small or minimal separation, arranged around the periphery. The plan beneath shows the many narrow plots that comprise the rectangular block.

The second 3D block drawing shows the same rectangular block, this time populated by larger buildings with broader facades and more space between one building and another. The plan beneath shows a smaller number of larger plots that comprise the rectangular block. ]

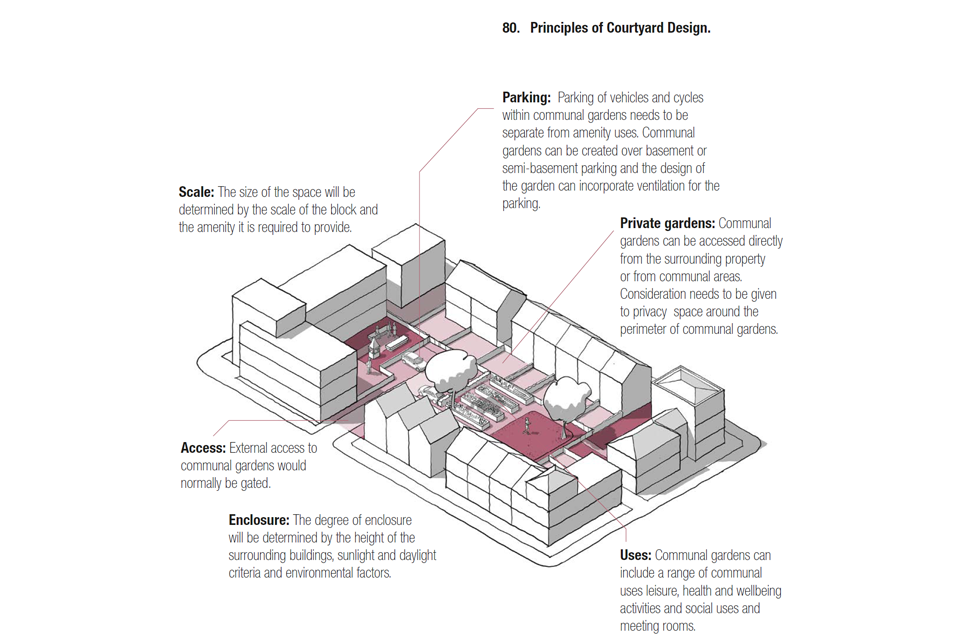

B.2 Built form

102. A design code may define a three-dimensional envelope for new buildings. The size and shape of this will vary depending on the nature of the area type and the blocks within it. This envelope consists of three separate measures: the development blocks established by the street network, the alignment of the front face of the building, and the height of the building.

B.2.i Blocks

103. A connected network of streets defines a series of blocks for development.

104. Built development blocks define the edge, and the three- dimensional enclosure of street spaces and their uses help to animate them.

105. Where development takes place around the edges of blocks, they are known as perimeter blocks. Provided that buildings face outwards onto the surrounding streets, perimeter blocks also create a clear distinction between the public fronts of buildings and the private backs. This has important benefits in terms of safety and security.

106. Area types will have an established network of streets and blocks. Coding can help ensure that the built form of new development in these areas relates well to the existing pattern of development.

107. On large sites a design code together with a masterplan may establish a new street network and structure of development blocks.

Figure 32. Blocks.

[Alt text: Illustrative drawing. This is a 3D line drawing of a mid density urban block. The image relates to the preceding text on blocks, and illustrates the difference between public space (on the outside of the block, e.g. the pavement, street etc) and private space (within the block, e.g. private back gardens, parking etc).]

Figure 33. Examples from different places show how many of them are based on different types of perimeter block.

[Alt text: Illustrative drawing.

Top down plan of Leeds City Centre showing rectangular perimeter blocks.

Top down plan of City of York showing smaller, generally square blocks, packed tightly together.

Top down plan of Letchworth Garden City showing more organic, low density perimeter blocks populated with mainly detached and semi detached buildings.

Top down plan of City of London showing rectangular perimeter blocks.

Top down plan of Ludlow showing highly regular rectangular perimeter blocks, packed closely together.

Top down plan of Bishops Castle, Shropshire, showing more organic perimeter blocks which vary in density around their perimeter. One edge comprises continuous buildings, while the other has more detached buildings with larger spaces between. ]

Figure 34. Types of Block: There are a wide variety of perimeter block forms that can accommodate housing and other uses:

[Alt text: Illustrative photos & drawings

The first image shows a view along the facade of the Roof Gardens development in Salford by Ollier Smurthwaite Architects, as example of a perimeter block. A top down plan drawing of a 40-50 meter wide perimeter block.

A photograph of The Pheasantry, West Sussex by AHR Architecture and Building Consultancy and Hastoe Housing Association. An example of an informal block. A top down plan drawing of an informal block, with semi detached houses arranged around the perimeter.

A photograph of Marmalade Lane, Cambridge, by Mole Architects - an example of a terrace. A top down plan drawing of a 25-30 meter wide terraced block.

An image of Accordia Sky Villas in Cambridge, by Alison Brooks Architects - an example of a mews block. A top down plan drawing of a 60-70 meter wide mews block. Residential units are set out around the periphery of the block, but a small street also runs through the middle of the block, allowing access to rear garages/annexes separated from the main property by gardens.

The image shows Donnybrook Quarter in Tower Hamlets, by Peter Barber Architects, an example of a courtyard block. A top down plan drawing of a courtyard block.]

1. Perimeter block: A strip of development around a private courtyard/gardens. The private interior is not accessible to people from outside the scheme. It includes private and communal gardens and car parking.

2. Informal block: Blocks like this can be found in many modern housing schemes. The housing faces outwards onto the surrounding streets with front and back gardens. The extra width allows a parking court to be included alongside houses and garage blocks within the courtyard to provide natural surveillance.

3. Terrace: The most common form is the typical English terrace which may include a rear alleyway. Codes for area types that include existing terraced housing need to consider reductions in back- to-back distances, compared to common practice so that new development relates to the context.

4. Mews block: Mews streets run through blocks, originally accommodating stable blocks to the rear of large houses. Now they have generally been converted to separate homes and workspaces. Modern versions of mews blocks include smaller single aspect homes above garages within the block.

5. Courtyard block: Sometimes buildings join to each other (party wall) not just on either side but also to the rear. This is a characteristic form of many historic cities (like York on the opposite page). There are also modern versions of this type of block with deep housing types with an internal courtyard.

B.2.ii Building line

108. Attractive streets and other public spaces are generally defined by the frontages of buildings around their edges.

109. A building line represents the alignment of the front face of the buildings in relation to a street or other public space. The nature of this line and its position in relation to the street contribute to the character and identity of a place. It may be straight or irregular, continuous or broken. A consistent approach to building line in an area type or street type helps to give it a coherent identity.

Figure 35. Repairing Urban Blocks: Infill sites can be an opportunity to repair the block structure and street grid of an area. This example shows an infill site that has been brought forward for housing development.

[Alt text: Illustrative drawing. This is one of two top down plans of a residential neighbourhood, comprised of a number of blocks. The smaller plan shows a large empty site surrounded by an existing block structure. This plan shows the same area, with new roads and blocks within the empty site, connecting into and reflecting the existing structure.]

Figure 36. Different area types are likely to have different building lines: A high street is likely to have a continuous building line set close to the street. In a suburban area the building line may be set further back from the street, with gaps in it.

[Alt text: Illustrative drawing. This is the first of two 3D line drawings of development fronting a street. They relate to the previous text and illustrate how different area types are likely to have different building lines. This image shows a suburban residential street where the building line is set back by front gardens and there are gaps between the buildings. The second image shows a high street, where the set back from the street is minimal, and the building line is continuous.]

Figure 37. Building Line Character: The shape of the building line will contribute to the character of the area. Orthogonal arrangements are more likely to be found in urban areas while curved streets are more suburban with detached building forms. The third option with irregular geometry that can be seen in some historic urban areas, from cities to villages.

[Alt text: Three highly simplified 3D line drawings showing different shapes of building line. The first is regular and orthogonal, with rectangular blocks set at right angles. The second is curved and sinuous, with winding streets. The third is irregular, but angular, with curves being formed from sharp angles rather than sweeping lines.]

Coding for the building line

110. Design codes may identify building lines and their characteristics for each area type to guide new development, including circumstances that allow for exceptions, e.g. where a mature tree interrupts the existing building line or creates a public space or forecourt.

111. They may also identify the proposed building lines for a large site based on the agreed masterplan, taking into account the hierarchy of streets, as well as the proposed area types.

3D aerial line drawing of a no. of neighbourhoods, linked by, and surrounded by, green spaces. This is an extract from the Nature section of the guidance notes, which provides more detail on biodiversity design principles and annotations for the drawing.