The national research environment for the study of extremism in the UK (accessible)

Published 14 December 2023

Prepared for the Commission for Countering Extremism (CCE)

This report has been independently commissioned. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the UK Government or the Commission for Countering Extremism.

Copyright © 2023 Daniel Allington

Executive summary

As a result of systemic problems both in studying extremism and in communicating the findings of such study, there are likely to be substantial gaps in the knowledge base around extremism in the UK.

Above all, there appears to be a lack of research on specific extremist movements in the UK today — especially when it comes to Islamist extremism. This suggests that it would be unwise to assume that publicly available research on extremism provides a sound basis for UK government policy.

Findings of the two studies reported here suggest that:

- The study of extremism is highly politicised, and its politicisation presents clear potential for silencing and exclusion of certain perspectives

- Projects supported by the major public research funders appear to be skewed towards studies of extremism in general, as well as towards studies of the far right, especially with regard to the UK of the present day and the recent past

- There may also be comparable skews in research carried out without such support (for example, within think tanks)

- There are many obstacles to collecting relevant data by conventional means, including when trying to access data and research participants via state agencies, such as HM Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS), and when seeking approval from risk-averse research ethics committees

- The use of ‘naturally occurring’ online data in place of more conventionally collected data raises problems of representativeness, and also does not always avoid difficulties with regard to ethical approval processes

- Lack of data-sharing makes it difficult for stakeholders to seek second opinions, and leads to duplication of effort

- Dissemination of research findings on extremist groups and their associates and supporters is hampered by several factors, including online intimidation, credible physical threats, and strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs, also known as ‘lawfare’ or ‘intimidation lawsuits’)

The skew towards generalism appears problematic in that policy applications for research on general phenomena (for example, radicalisation) may be unclear in the absence of research on how those phenomena are manifest ‘on the ground’ (for example, in the recruitment practices of specific organisations). The skew towards studies of rightwing extremism, and away from studies of Islamism (especially in a contemporary UK context), could also perhaps be seen as problematic, given that Islamist extremism proportionally represents a far greater terror threat in the UK (see, for example, the Independent Review of Prevent), although that is an inherently political matter.

This report further suggests the existence of multiple social and ideological pressures which could potentially distort the research field:

-

The skew towards general studies may be partly explained by an academic tendency to devalue ‘descriptive’ studies of specific phenomena: ambitious researchers are incentivised to target high prestige journals which tend to favour general and theoretical research, and it may be that such research is also favoured by peer reviewers of grant applications

- It may also be partly explained by the risks run in researching specific organisations which may respond with legal, physical, and other threats (see above)

- The skew towards studies of the far right may be partly explained by a tendency to focus on short-term government priorities, with one ‘hot topic’ at a time attracting funding (right-wing extremism having been the most recent ‘hot topic’)

- There is evidence of possibly justified concern that studying Islamist extremism might lead to a researcher’s being labelled as racist

- There is also evidence of possibly justified concern that being perceived to be critical of actions supporting ‘progressive’ or left-wing causes might lead to negative professional consequences (‘cancellation’)

- Given another study’s finding that a significant minority of academics may discriminate against funding applications on ideological grounds (whether from a leftor right-wing perspective), there appears to be a plausible risk of silencing and exclusion through peer review, especially as the typical approach to peer review of grant proposals is one that appears particularly vulnerable to bias

- Beyond this, it seems likely that fear of ideological discrimination may have a general chilling effect, potentially leading researchers to avoid engaging in projects that they suspect could lead to controversy that might be harmful to their careers

The problem of possible ideological bias in peer-review could be mitigated through adoption of open peer review (increasing reviewer accountability) or through a transparent process of reasoned adjudication between contradictory reviews on the part of an identifiable individual (increasing funder accountability). Awarding small grants through open competition with quotas for particular kinds of extremism might help to ensure that study of and expertise in key areas continues to be supported despite cyclical shifts. Universities and HMPPS could assist by ensuring that their approval processes do not obstruct public interest research on extremism.

A governmental commitment to notifying researchers when their work is cited in briefing documents or makes any other contribution would also help to ensure the continued supply of useful research, especially where this is not funded by the government. Value could be added to government-procured research through engagement of entities from across the research ecosystem in the design, analysis, interpretation, and dissemination stages of research projects commissioned from generic research providers, as well as through requirements for data sharing.

Lastly, and perhaps most urgently, the government and the Solicitors Regulatory Authority (SRA) could publicly acknowledge the threat which SLAPPs present to the sharing of information about extremist groups, their associates, and their supporters. Potential remedies might include legislation, as well as guidance issued and action taken by the SRA.

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

Although there are many fields of enquiry in which ‘pure’ research is necessarily dominant, the study of extremism is an applied social science. Extremism researchers aim to influence and inform policymakers, practitioners, and the public. To take just one area in which research on extremism may serve to inform policy and practice, the National College of Policing advocates for the use of ‘the best available evidence . . . to inform and challenge policing policies, practices and decisions’, and notes that research can help stakeholders not only to ‘develop a better understanding of an issue — by describing the nature, extent and possible causes of a problem or [by] looking at how a change was implemented’ but also to ‘assess the effect of a[n] . . . intervention — by testing the impact of a new initiative in a specific context or exploring the possible consequences of a change’ (College of Policing, n.d.). Extremism is also a frequent topic of interest for the mass media, with researchers based in universities and think tanks often contributing interviews and op-eds, or simply providing quotes as subject-matter experts. The research community thus provides a vital component in a society’s attempts to respond to the threat of extremism, however it is to be conceived. As a result, the question of how that community carries out the task of researching extremism — of the ways in which individual researchers choose directions for study, and of the ways in which they are supported or frustrated in their efforts to pursue knowledge in those directions and then communicate their findings to stakeholders and the public — is of more than academic interest. In adapting to structures of incentives and disincentives (opportunities for funding or exposure, for example) and navigating obstacles (difficulties with access to research subjects, for example) researchers jointly construct the evidence base on which policy, practice, and public opinion rely when it comes to this key area. Thus, the institutional conditions for research — the research environment, in this study’s terminology — can be seen to set the parameters within which knowledge of extremism can emerge. At a further remove, what is known about extremism is one of the principal determinants of what can be done about extremism. Understanding the national research environment for the study of extremism should thus be understood as a necessary first step in the development of an extremism research policy designed to produce an evidence base adequate to support a democratic, wholesociety approach to extremism.

1.2 Definitions

This report adopts the UK government’s official definition of ‘extremism’ as ‘vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty, and mutual respect [for] and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs’ (Secretary of State for the Home Department 2011, 107). In common with UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), this report defines ‘research’ as ‘as any form of disciplined inquiry that aims to contribute to a body of knowledge or theory’ (UKRI 2023).

1.3 Structure and purpose

The current report presents two studies. The first of these is a quantitative survey of research grants competitively awarded by UK funders in recent years. It aims to provide a high-level summary of the extremism-relevant topics that this form of funding has supported. The second of the two studies is a qualitative analysis of semi-structured interviews with UK-based extremism researchers at all levels of seniority, both inside and outside the university system. Although the interviewees are not claimed to constitute a representative sample (indeed, it would be hard to define the population which such a sample would ideally be representative of ), their perspectives enable exploration of the complex tangle of incentives, disincentives, and obstacles negotiated by extremism researchers. These interviews are supplemented by an unstructured interview with a Home Office research programme lead, who provided insight into the interface between extremism researchers and government research stakeholders.

The report ends by trying to draw together the findings of the two studies, and by making recommendations derived from those findings.

2. Study I: Quantitative survey of competitive public research grants

The first study to be presented in this report is an attempt to map out statistical patterns in grants supporting research into extremism and awarded by UK public funders through open competition. By design, this study relies entirely upon open-source data drawn from the websites of the funders themselves.

It is acknowledged that a great deal of research is not publicly funded. Indeed, much academic research is not ‘funded’ in any formal sense, being the work of scholars whose posts are primarily supported through teaching-related income: a point to which Study II shall return (see in particular Section 3.3.3). Moreover, much public funding for research is not awarded through open competition but through procurement tendering, while a further proportion of research is funded by non-public means, including donation. This study can therefore only survey a proportion — perhaps a very small proportion — of the UK’s total extremism-related research output. But, however small that proportion is, it has special importance. Firstly, such funding is one of the levers by which the research activity of individuals and organisations may be (perhaps inadvertently) nudged in particular directions. Secondly, it can facilitate researcher-directed activities that would otherwise be very difficult to sustain.

To expand upon the first point, public research funding is one of the primary means by which research is incentivised, both at the institutional level, and — thanks to intrainstitutional reward structures — also at the level of the individual researcher. For example, a typical set of academic promotion criteria for a research-intensive university requires ‘[c]ontribution to successful funding applications’ at grade 7 (Lecturer A), ‘highly rated [independent] grant applications’ at grade 8 (Lecturer B), and ‘[r]esearch income in excess of the Russell Group median for the discipline’ at grade 9 (Senior Lecturer) (University of Glasgow, n.d.c, 2), with successively more onerous requirements at higher levels (University of Glasgow, n.d.b, 2; n.d.a, 3). Whether funders and government agencies intend it or not, competitive awards of funding thus send out a powerful signal as to the kinds of projects which researchers should attempt to replicate if they wish to be successful in their careers.

Moving on to the second point, there are many research activities which depend to a greater or lesser extent on funding. For example, some of the most important forms of data collection (such as fieldwork interviews, experiments, and representative sample surveys) may be unfeasible without some level of financial support. Where this support is an expense budgeted into a tender submission, the researcher or research team acts as a supplier and must meet client requirements very closely. A grant, however, typically allows researchers greater freedom to follow emerging insights — and will often allow them to do so over a far longer time period. Moreover, the findings of grant-supported research are likely to be published openly, often in peer-reviewed venues, contributing to the general store of knowledge on a topic rather than simply satisfying a single research client’s immediate need for information. Grant-supported research thus has many advantages over other forms of research, and, in studying the grants awarded to extremism research, one may learn something important about the conditions which make particular extremism research projects possible or impossible.

Altogether, three funders were studied. These were UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), the Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats (CREST), and the Commission for Countering Extremism (CCE) — the latter of which also funded this study. UKRI receives funding from general taxation via the Department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy; at £7.9 billion, its 2021/2022 budget accounted for about half of the UK’s total public spend on research and development, although just £1.5 billion of this took the form of research grants (UKRI, n.d.a, 3, 8). CREST receives funding via UKRI from British intelligence and security agencies as well as from the Home Office (CREST, n.d.a); it received £4,859,620 for the period running from September 2020 to June 2024, of which £900,000 was earmarked for research commissioning (CREST, n.d.b). The CCE is funded via the Home Office, and does not primarily exist to support public research, although it chose to do so in 2019, when, under the leadership of Dame Sara Khan, it opened a one-off, rapid-turnaround public competition for multiple small grants to study particular aspects of extremism (CCE 2019). Charitable funders such as the Airey Neave Trust (a provider of relatively small grants exclusively for the study of terrorism and extremism) and the Leverhulme Trust (a provider of often very large grants for all forms of non-medical research) were not studied. The British Academy (a public provider of fellowships and small grants across the humanities and social sciences) was also not studied, because too little information was publicly available for awards made prior to 2022.

Although UKRI has been referred to above as a single funder, it is in fact an umbrella body incorporating nine research councils. In the research presented below, these are analysed as separate entities alongside UKRI, which makes an appearance only thanks to the rare instances where it, rather than one of its constituent bodies, was the specified funder of a project. Of the nine research councils, five were relevant to Study I. These were the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC), and Innovate UK. The other four research councils — the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the Medical Research Council, the Science and Technology Facilities Council, and Research England — were not found to have funded any research that could be included in the study.

Think-tank research is largely excluded from this study, because (while there have been exceptions) think tanks do not typically apply for research funds from these sources, for reasons that will be touched on in Study II. However, as Study II will argue, this kind of funding can act to sustain expertise within the university system, which can then be drawn upon by think tanks and stakeholders. The precise nature of the research that public funders choose to support may thus indirectly act to shape the pool of experts available for consultation or for involvement in further research not necessarily funded in the same way.

2.1 Research questions

Study I was designed to answer the following research questions:

- What roles do different UK public research funders play in supporting research on extremism?

- Which forms of extremism, in which time periods, and in which geographical locations, have UK public research funders facilitated the study of?

The study was originally intented to address the additional question of which research methodologies most frequently received public funding. However, it was found that publicly-available information on funded projects was often insufficiently detailed to enable the methodology of a research project to be identified.

2.2 Methodology

2.2.1 Search strategy

An initial search for UKRI grant-funded projects was done via the UKRI web portal because search via the Gateway to Research API (UKRI 2021) — a UKRI software interface provided in order to facilitate automated data collection — offered fewer documented options for refinement. Search strings are listed below, and were applied to title and abstract, then filtered by date range (requiring a start date between 2018 and 2022, inclusive), with results being downloaded in table format. After this, data were processed and prepared using scripts (i.e. short computer programs) written in the statistical programming language, R.

Both via the API and via the portal, the UKRI system appeared to recognise ‘extremist’ (although not ‘extremism’) as a synonym of ‘extreme’, and this apparently undocumented behaviour resulted in thousands of hits unrelated to extremism, such as ‘Extreme laser-driven hydrodynamics’ (Dior 2021-2025) or ‘Multipoint sensors for extreme environments’ (Fells 2020-2025), both of which were funded by the EPSRC. These spurious hits were removed by requesting full information for all projects via the Gateway to Research API, and then filtering out entries which did not actually feature the string ‘extremist’. Hits for the ‘extremist’ search string were only integrated following this cleaning process, which was again accomplished through coding in R. The use of a separate data-collection procedure for that particular search term was time-consuming, and ultimately added few projects to the sample, but to have avoided it would have raised concerns about completeness, as there would have been no way of knowing how many relevant projects had been missed. Total hits are given in Table 1.

This strategy located a total of 42 documents featuring the term ‘extremist’, although the initial search pulled in 3169. All other search terms received a total of 376 hits; however, after duplicates had been removed, the true total was 298. The search term ‘extremist’ increased this total by just two, with the result that the total number of UKRI-funded projects to request for download came to exactly 300.

CREST appears not to offer API or portal access to a database; instead, it maintains a website with funded projects organised by manual tagging. However, the number of funded projects in the time frame (two starting in 2018, 11 in 2019, 15 in 2020, 12 in 2021, and two in 2022) rendered manual data collection feasible. Projects were filtered by tag, selecting in turn ‘Countering violent extremism’, ‘Extremist actors’, and ‘Radicalisation’ (there was no category for ‘Terrorism’ or similar), recording project URLs where the start date fell within the range of interest, and using a web scraper written in R to download and extract project information from the files located by the URLs. Relevant details were stored in a table, with the project summary and the information contained in the ‘Show more’ drop-down being combined into a single text to be treated as an abstract. The number of hits per tag is given in Table 2. Once duplicates were removed, a total of 15 CREST-funded projects remained.

The CCE funded several research projects following an open call issued in February 2019. These were included in the current study via their published outputs, 17 of which were found on the UK government website (any uncompleted projects or projects whose outputs did not pass peer review will not have been published). All were considered relevant by virtue of having been specifically funded as studies of extremism. The only publicly available information on the projects consisted of the published papers themselves, plus the sparse information contained in their pages on the government website. Titles, abstracts, and other information were copied and pasted from these two sources into a table. Where an abstract was not included in the paper itself, the introductory section from the paper was used as a substitute. In the single case where there was neither an abstract nor an introductory section, the brief description of the paper provided on the relevant page of the UK government website was used instead.

Table 1: Hits for search strings, UKRI portal

| Search string | Hits |

|---|---|

| extremist | 3169 [42] |

| terrorism terrorist | 126 |

| communism communist “revolutionary socialism” “revolutionary socialist” | 70 |

| stalinism stalinist trotskyism trotskyist maoism maoist extremism | 46 |

| radicalism radicalisation | 43 |

| “far right” “extreme right wing” | 43 |

| islamism islamist “islamic state” | 25 |

| anarchism anarchist | 10 |

| jihadi jihadism jihadist | 6 |

| “white nationalism” “white nationalist” | 3 |

| “neo-nazi” “neo-nazism” | 2 |

| “far left” “extreme left wing” | 2 |

Table 2: Hits for tags, CREST website

| Tag | Hits |

|---|---|

| Countering violent extremism | 7 |

| Extremist actors | 8 |

| Radicalisation | 6 |

2.2.2 Inclusion criteria

Data on a total of 332 projects were collected. However, the majority were entirely irrelevant for the purposes of this study. For example, a toxicological investigation of certain chemicals whose abstract notes that ‘these compounds [have been] used as chemical warfare / terrorist agents’ (Bury 2020-2024) is not a study of extremism or terrorism: it is a piece of natural sciences research whose importance to society is advertised partly through allusion to the potential relevance of its findings in the event of a possible future terrorist attack. Similarly, a study of cinematic representations of the Holocaust which characterises the ‘current political climate’ in terms of ‘resurgent far-right elections across Europe’ (Rixon 2020-2023) is not a study of the far right: it is, rather, a study of Holocaust memory which notes for context (again, partly as a way of advertising its wider social importance) that representatives of the broad political grouping whose past representatives include the perpetrators of the Holocaust have enjoyed recent electoral success in some European nations. There was also the question of what to do about studies concerning state terrorism when conducted at home, or states whose official ideologies would be recognised as extremist: a study of Nazi death camps or Soviet gulags is unlikely to have great relevance to UK counter-terrorism policy, for example, and it would clearly be unhelpful to include e.g. a historical study of the Iran-Iraq war simply because both sides were led by rulers whose views would be regarded as extremist in the UK. In addition, the grant which supports CREST was excluded, as CREST is here analysed as a funder in its own right (moreover, the funds comprising that grant have a different source).

A study whose details were collected as part of the search could be included in the quantitative analysis only if:

- It prominently and explicitly identifies itself as a study of terrorism, terrorists, extremism, extremists, radicalisation, counter-terrorism, counter-extremism, or de-radicalisation (regardless of how these are defined), OR

- It centrally concerns acts of terrorism (as defined in UK law) or individuals, groups, or movements who carry out or endorse such acts, except where the acts of terror are conducted by state agencies within the borders of the states in question, OR

- It centrally concerns individuals, groups, or movements characterised by extremism (as defined in the UK counter-terrorism strategy) or conventionally identified as extremist (e.g. Islamist, far right, far left, etc), except where the ideology of those individuals, groups, or movements is the official ideology of the states in which they operate

For these purposes, the so-called Islamic State (i.e. the entity also referred to as IS, ISIS, or Daesh) was not treated as a state, as it was not internationally recognised as a state. That is, studies of Islamic State were regarded as studies of a terrorist organisation operating within the borders of Syria and Iraq. In order to avoid debates as to what should count as ‘extremist’ in historical contexts, projects were automatically excluded if their period of study entirely preceded 1918, i.e. a century prior to the earliest start date for the research projects themselves.

Altogether, 118 projects were found to satisfy the above criteria and thus included in the study. This set of projects is treated as the sample for the analysis presented in the remainder of that part of this report which is devoted to the current study. It is acknowledged that other inclusion criteria would have been possible and that human or technical error may have led to the unintentional exclusion of some projects, and that the data collection strategy may have failed to identify some projects that could potentially have met the inclusion criteria: for example, additional search terms might have pulled in relevant studies that were never examined here. However, it is argued that the sample can be assumed to provide a reasonably complete snapshot of UK extremism research projects which began in the five years from 2018 to 2022 and were supported by public funds allocated through open competition.

It is further emphasised that not all projects included are primarily focused on extremism. Indeed, the project with the greatest funded value was not (see below). Moreover, even those studies which were primarily intended to study movements, organisations, or ideological currents here characterised as extremist did not necessarily characterise their objects of study as ‘extremist’ — a term which many scholars of certain such movements would be likely to regard (at best) as unnecessarily pejorative. An example of a funded project on a movement regarded as extremist for the purposes of the current study, but not apparently treated as extremist by the researcher or researchers involved, is ‘Women as Transnational Agents in the Development of Iberian Anarchist Thought and Practices Relating to Female Bodily Autonomy in the Interwar Period’ (Turbutt 2021-2025). If anarchism is defined as a form of extremism, or as relevant to the study of extremism (as it is for the purposes of this study), then the outputs of research projects looking at anarchism (such as Turbutt 2022) can be considered to contribute to the knowledge base on extremism, for example by serving to inform potential literature reviews, regardless of whether or not they treat their objects of study as ‘extremist’. Indeed, such works might even contribute by helping to establish that some particular movement, organisation, or ideological current should not be regarded as extremist.

For a complete list of included projects, with start dates, funders, banded levels of funding, and titles, see Appendix I. Perusal of the titles may give the reader a perspective which goes beyond the largely statistical analyses which follow; combined with a search engine, they may perhaps serve as a useful index to recent extremism-related research projects in the UK satisfying the criteria above.

2.2.3 Data preparation, extraction, and analysis

An R script was used to extract data from the various tables and to create a uniform HTML page for each project. A Google Forms questionnaire was created on which to record relevant information for projects that met the inclusion criteria (see Appendix II). Extracted data were then downloaded in the form of a new table and combined with automatically harvested information for visualisation and analysis using R. Confidence intervals and tests of statistical significance were considered to be unnecessary (and would indeed have been meaningless) as this is in effect a ‘whole population’ study: that is, the numbers calculated do not relate to a random sample from which statistical inferences may be drawn, and with regard to which a degree of statistical uncertainty can be mathematically estimated; rather, they describe the characteristics of the complete set of funded studies discoverable via the search strategy at the time of data collection and subsequently found to satisfy the inclusion criteria. Human error and unanticipated technical issues may have resulted in the exclusion of funded projects which might have changed the analysis in some way, for which reason, statements of findings are appropriately hedged. However, the approach throughout has been to follow clearly described procedures as rigorously and transparently as possible, in order to minimise ambiguity.

Discussion of statistical patterns in the following sections is in many cases supplemented by brief focus on the project in each category with the greatest funded value. This means that CREST-funded projects, whose funded value is not public, and CCE-funded projects, which were all supported by small grants, were not used as examples. In one case, it was found that details available via the UKRI website contradicted details collected via the API. This contradiction is noted in the text below. Due to time constraints, information available via the API was otherwise treated as accurate in the main analysis, as it would not have been possible to cross-check every piece of information against the UKRI website. For projects supported by the two non-UKRI funders, there was only a single information source, so the possibility for contradiction did not arise.

2.3 Findings

2.3.1 Projects by funder

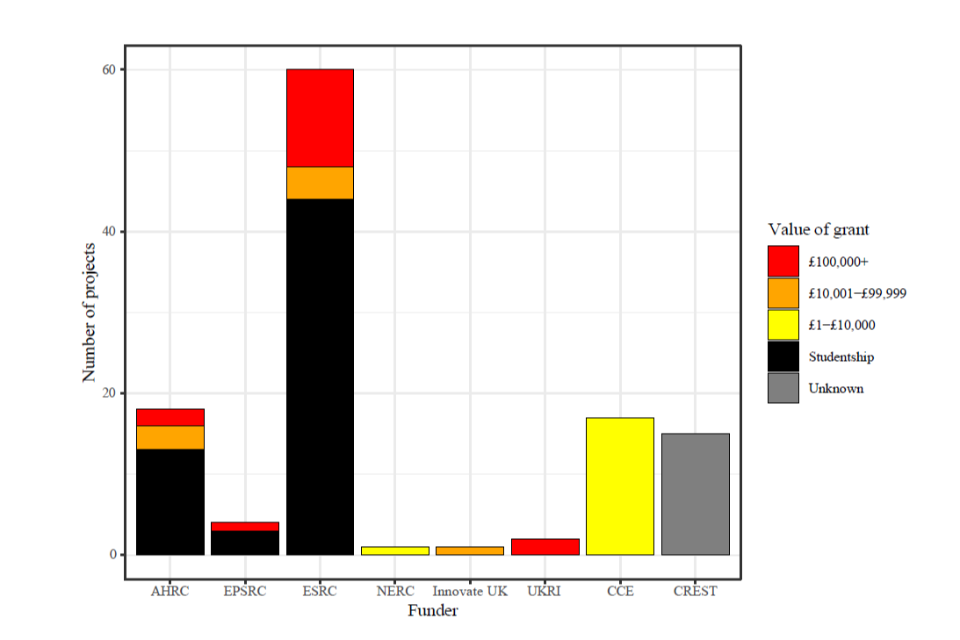

For total numbers of projects funded by each funding body, broken down by size of grant, see Figure 1. The most important funder by far, with more than three times as many projects supported as its nearest competitor, and with six times as many to have received grants of £100,000 or more, appeared to be the ESRC: one of the seven research councils incorporated within UKRI. However, it should be borne in mind that studentships constituted the great majority of projects funded by all three of the research councils found to have funded extremism research during the period in question.[footnote 1] The largest number of non-studentship projects were funded in the CCE’s single round of funding, although the grants in question were capped at £10,000. The size of CREST grants is not announced via the CREST website, and is therefore recorded as ‘Unknown’.

Figure 1: Funded extremism projects by funding body, 2018-2022

Two large grants were attributed directly to UKRI, rather than to any of its constituent funding bodies.

It should be noted that the numbers are quite small — as was the total spend (so far as it can be determined). When studentships are excluded, the UKRI and its constituent research councils funded 26 projects that could be included in this study — an average of 6.5 projects per year — as compared to the total of 17 that were funded by CCE and the total of 15 that were funded by CREST. The research council-funded extremism research projects included some that were relatively high-cost, with the median value being £113,569, but the total value over the four years (again, excluding studentships) was just £6,491,101. Although this may seem at first glance to be a very substantial sum, it represents just £1 in every £1000 that UKRI and its constituent research councils awarded in the form of research grants during the same period. Moreover, 19% of it went to support a single project which was not primarily focused on extremism (more details below).

2.3.2 Projects by form of extremism

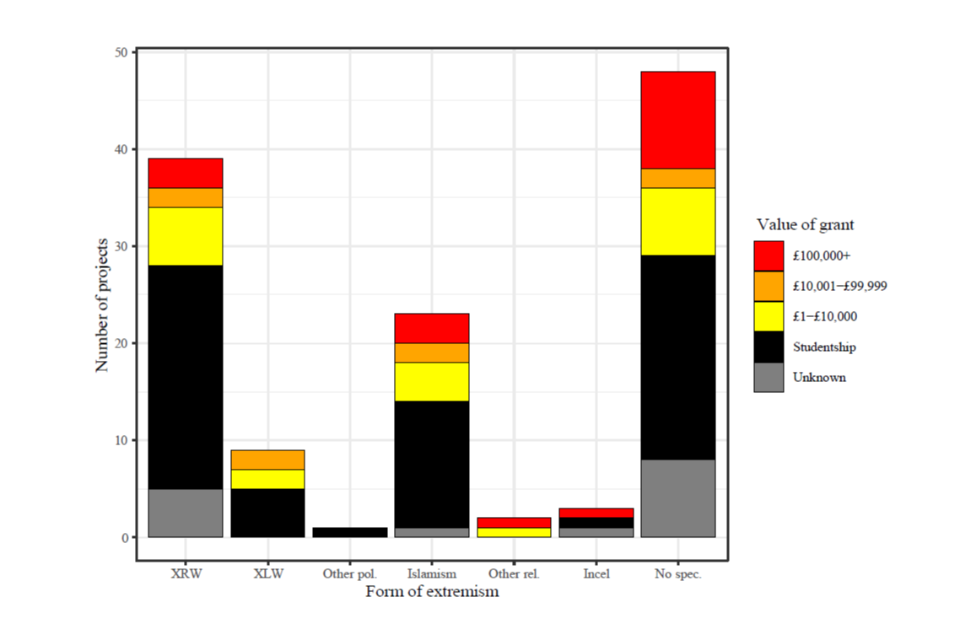

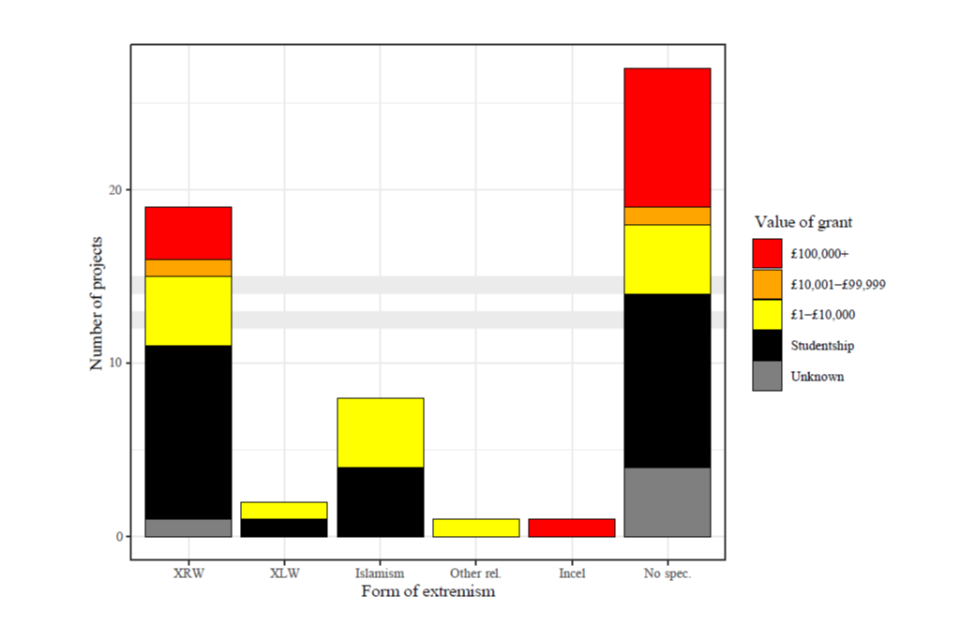

For number and funded value of projects by form of extremism studied, see Figure 2. Abbreviations used for forms of extremism are explained in Table 3. Studies specifying more than one form of extremism could be counted in multiple categories.

Figure 2: Funded extremism projects by form of extremism studied, 2018-2022

Absences are as important as presences. Thus, the reader’s attention is drawn to the fact that several forms of extremism which were treated as possible categories in data collection did not appear in the data. It may of course be that some eligible projects focusing on such forms of extremism received funding, but failed to be captured by the search terms used. However, this would only apply to UKRI-funded projects, as potentially eligible CREStand CCE-funded projects were not identified through keyword search.

In particular, the data collection strategy pulled in no projects focusing on ethnic forms of extremism other than that of the far-right, no projects focusing on forms of misogynist, sexual, or gender-related extremism other than those looking at Incels, no projects focused on single-issue extremism, and no projects focusing on extremism motivated by what is officially referred to as ‘mixed, unstable, or unclear’ ideology. The project which focused on a political form of extremism other than that of the far left was a studentship entitled ‘The role of tribalism in sub-Saharan terrorist groups’, which involved the use of fieldwork interviews and surveys in Nigeria and Kenya in order to gather new data on Boko Haram and the Mau Mau (Micheni 2018-2022). While Boko Haram are an Islamist group, the ideology of the Mau Mau was not Islamist, and thus, this project was double-counted. As an anti-colonial nationalist movement, the Mau Mau could have been treated as left-wing extremists or as ethnic extremists other than of the far right, but either of these analyses would have been problematic, so ‘Other political extremism’ was regarded as the most straightforward categorisation.

The largest group of projects comprised those that did not specifiy a particular form of extremism, of which there were 48 (i.e. 41% of all included projects). This category was particularly well-represented among the highest known-value projects: 59% of projects in the £100,000+ category, as compared to 38% of projects across the other four categories, concerned no specific form of extremism. This category also encompassed the single highest-value project included in the current study: ‘Governing Democratic Discourse: Social Media, Online Harms, and the Future of Free Speech’, funded value: £1,222,449, which (as mentioned above) was directly funded by UKRI. This project is a philosophical study of ‘a wide variety of harmful speech that is pervasive on social media networks, including hate speech, terrorist incitement, disinformation and misinformation, cyber-harassment, advocacy of self-harm, micro-targeted electioneering, foreign propaganda, and divisively uncivil political speech’ which will involve the production of ‘a combination of traditional academic outputs and innovative public resources, including an informational project website, an educational podcast, a major policy report, and a pilot civic education curriculum for secondary school students’ (Howard 2022-2026, n.p.).

The second largest group consisted of projects studying right-wing extremism. Among projects of known financial value, the highest-value project in this category was ‘Everyday transnationalism of the far right: an interdisciplinary study of Polish immigrants’ participation in far-right groups in Britain’, funded value: £682,950 (Garapich 2023- 2026). This was a three-year ESRC-supported project led by Roehampton University and involving ethnographic observation and semi-structured interviews with members of far right groups in six locations within the UK. The total number of funded projects concerning Islamist extremism was considerably lower, although the gap was mostly accounted for by the much greater number of studentships focused on the far right. The highest-value project of known value in this category was a two-year ESRC-funded project led by the University of Glasgow, ‘Mobilisation of foreign fighters in the former Soviet Union’, funded value: £472,751: a fieldwork-based study involving interviews with ‘active, former, and aspiring foreign fighters in Ukraine, Russia’s republic of Dagestan and amongst the Chechen Diaspora in Western Europe’ (Aliyev 2022-2024, n.p.). The fourth-placed category, i.e. left-wing extremism, fell far behind, with only nine studies, five of them studentships. None of the studies of known value in this category reached six figures in the sum awarded, the highest-value award being the ESRC grant to support ‘The Politics of Women’s Agency: Gender and Peacebuilding in post-conflict Nepal’, funded value: £98,687. This two-year project built on the ethnographic fieldwork carried out by its principal investigator in the course of her PhD research on the Nepali Maoist movement, and involved the production of peer-reviewed journal articles and the organisation of ‘a one-day workshop in Kathmandu . . . [and] six workshops in three rural districts in Nepal, engaging women ex-fighters and women activists’ (Ketola 2018-2020, n.p.).

There were only two funded projects looking at other forms of religious extremism, and just three looking at Incels. Each of the latter two totals included a single highvalue grant. The high-value award relating to non-Islamist religious extremism was an ESRC grant to support the seven-month project, ‘Explaining non-state armed groups perpetration of mass atrocity crimes’, funded value: £321,901 according to the API and £399,826 via the UKRI website. This project was double-counted because its list of relevant non-state armed groups comprised one Christian extremist organisation, the Lord’s Resistance Army, and four Islamist organisations: Al Qaeda, Islamic State, Boko Haram, and Al-Shabaab (Hinkkainen 2021, n.p.). Led by the University of York, the project aimed to collect systematic evidence on such groups in six countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East, focusing both on ‘group characteristics, such as age, ideology, and external support’ and on ‘interactions, for example, between the non-state armed group[s] themselves, other actors such as the government, and external actors such as UN peacekeepers’ (Hinkkainen 2021, n.p.). The high-value award relating to Incel extremism was an AHRC grant to support a project led by University College London and entitled ‘Understanding the Cel: Vulnerability, Violence and In(ter)vention’, funded value: £201,027. This two-year project ‘seeks to save the lives of potential victims as well as perpetrators’ of Incel violence by using ‘[c]reative research methods’ to develop ‘new knowledge about the culture of Incels, the identities and experiences of this complex community, and the factors contributing to the risk of extreme violence and hate crimes’, and to use this knowledge to develop training resources in partnership with the Metropolitan Police Force and Police Scotland (Regehr 2022-2024, n.p.).

Table 3: Abbreviations for forms of extremism used in visualisations in this report

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

|---|---|

| XRW | Right wing extremism |

| XLW | Left wing extremism |

| Other pol. | Other political extremism |

| Islamism | Islamism |

| Other rel. | Other religious extremism |

| Incel | Incel / misogynist |

| No spec. | No specific form of extremism |

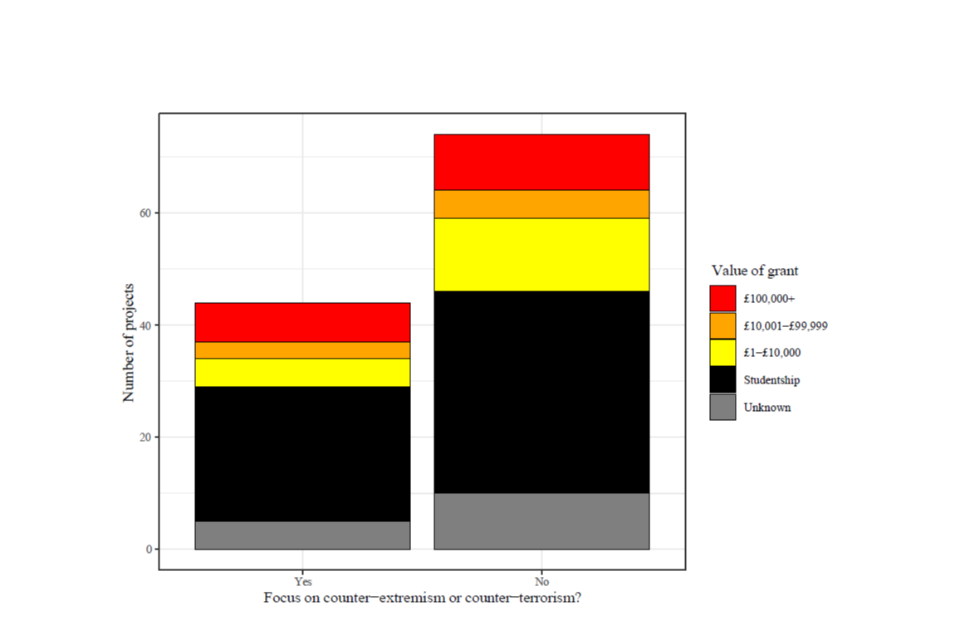

2.3.3 Projects by focus on counter-extremism or counter-terrorism

There were 44 included projects concerning counter-extremism or counter-terrorism (see Figure 3). These account for 62% of projects not focused on any particular form of extremism. Among projects of known funded value, the one to receive the largest grant was ‘The Transformation of Transatlantic Counter-Terrorism 2001-2025’, funded value: £631,587. This four-year project, one of the few which appeared to be funded directly by UKRI, is a study of organisational change in Usand EU-based counter-terrorism, using documentary sources, interviews, and ethnographic observation (Bury 2020-2024). Also included in this category were several critiques of the Prevent programme and a number of projects aiming to develop technological systems for detecting extremist speech on social networking services.

Figure 3: Funded extremism projects by focus on counter-extremism or counter- terrorism, 2018-2022

Although it would be unreasonable to go into the same level of detail on all categories discussed in this study, the above discussion should suffice to provide an indication of the diversity of publicly-funded research on extremism, as they range from projects looking at specific extremist groups to projects looking at no form of extremism in particular, from projects focused on data collection to projects focused on sharing theoretical knowledge or findings arising from prior studies, and from projects focused on specific real-world locations to projects primarily dealing with the Internet. There is, moreover, a great deal both of creativity and of scholarly rigour evident in the design of many of the projects. However, the question of whether these projects are optimally targeted to contribute to actionable knowledge about UK terror threats remains open.

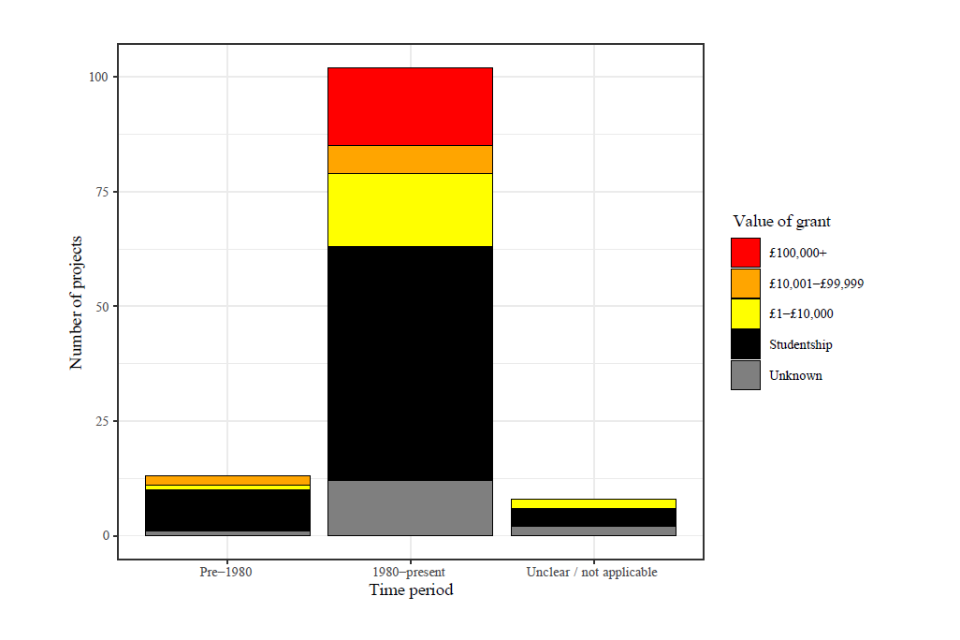

2.3.4 Projects by location and by period

For funded projects by location of object of study, see Figure 4. This reveals that studies of the UK context were the most common by some margin, although it also shows that the difference in frequency between those studies and studies of the rest of the world is almost entirely accounted for by projects of low or unknown value (which is for the most part to say, projects funded by CREST and the CCE). Interestingly, there were only two projects in the highest funding band which gave no specific geographical location. For funded projects by time period of object of study, see Figure 5. By far the largest group of studies concerned extremism in the 42 years from 1980 until the time of data collection. Studies of extremism at earlier points in history were relatively rare. This suggests that the study of extremism is primarily concerned with the present and the recent past, although it is noted that studies of the Nazi and Soviet regimes were excluded from the data collection by design. It is further noted that all of the high-value grants were received by projects identifiably linked to the most recent time period, and that this category also accounted for the bulk of the projects of low or unknown value (see above).

Figure 4: Funded extremism projects by location of phenomena studied, 2018-2022

Figure 5: Funded extremism projects by time period of phenomena studied, 2018-2022

Figure 6: Funded extremism projects by funder and form of extremism studied, 2018-2022

| AHRC | EPSRC | ESRC | NERC | Innovate UK | UKRI | CCE | CREST | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XRW | 9 | 1 | 18 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| XLW | 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Other pol. | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Islamism | 2 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Other rel. | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Incel | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| No spec. | 1 | 3 | 26 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 8 |

2.3.5 Intersections between categories

For funded projects by funder and form of extremism studied, see Figure 6. All funders except for the AHRC and NERC (the latter of which funded only a single study) funded more projects with no specific form of extremism than with the most commonly specified form of extremism, but this tendency was strongest at CREST, where 53% of funded studies did not concern a particular form of extremism, compared to 40% of ESRC-funded and 37% of CCE-funded projects.

The most commonly specified form of extremism was in all cases right-wing extremism. However, the ESRC and CCE funded almost as many projects looking at Islamism as looking at right-wing extremism. Thus, the large imbalance towards the extreme right is mostly accounted for by the set of projects funded by the AHRC, which funded just two studies looking at Islamism, and by CREST, which funded just one: ‘Mapping terrorist exploitation of and migration between online communication and contenthosting platforms’, a one-year project of unknown funded value at King’s College London which focused exclusively on the online realm (Maher 2020). Studies of leftwing extremism were mostly funded by the AHRC — a point which may be explained by the time period on which they were focused (see below).

For funded projects by time period and form of extremism studied, see Figure 7. This shows that left-wing extremism was the only form of extremism primarily featured in projects focused around the years prior to 1980, where it was more often represented in funded projects than right-wing extremism, and where projects looking at no specific form of extremism were not represented at all. This may account for the unusually frequent appearance of left-wing extremism among AHRC-funded projects, as the academic discipline of History falls within the AHRC’s remit. Studies of Islamism during the period were effectively absent, as the only project to fall at the intersection of the two categories was the aforementioned studentship focused on Boko Haram and the Mau Mau: this was correctly double-counted for both period and form, but the Islamist group in question came into existence in the post-1980 period, while the pre-1980 group was not Islamist.

Figure 7: Funded extremism projects by time period and form of extremism studied, 2018-2022

| Pre-1980 | 1980-present | Unclear / not applicable | |

|---|---|---|---|

| XRW | 6 | 34 | 1 |

| XLW | 7 | 5 | 0 |

| Other pol. | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Islamism | 1 | 23 | 0 |

| Other rel. | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Incel | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| No spec. | 0 | 41 | 7 |

For funded projects by location and form of extremism studied, see Figure 8. Interestingly, the aforementioned dominance of projects investigating the extreme right is much more pronounced with regard to UK-focused studies: among the latter, more than twice as many funded projects looked at the far right as at Islamism, which was in turn the focus of twice as many funded projects as the next-largest category, the far left. By contrast, in studies looking at identifiable locations outside the UK, there were nearly as many studies focused on Islamism as there were focused on the far right. (The sole CREST-funded project on Islamism had no particular geographical location, being the aforementioned study of how Islamist extremists have migrated between online platforms, Maher 2020.) Perhaps unsurprisingly, projects associated with no particular time period or location were also overwhelmingly associated with no particular form of extremism. Interestingly, these projects appeared to have attracted few grants confirmed to be of large or medium size — although projects with no clear location included a disproportionately high number of grants of unknown value (which is to say, grants awarded by CREST).

Figure 8: Funded extremism projects by location and form of extremism studied, 2018-2022

| UK | Rest of world | Unclear / not applicable | |

|---|---|---|---|

| XRW | 20 | 17 | 9 |

| XLW | 4 | 6 | 0 |

| Other pol. | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Islamism | 8 | 14 | 3 |

| Other rel. | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Incel | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| No spec. | 27 | 9 | 20 |

Fully representing the intersections between forms of extremism, locations, and time periods in a single visualisation would be excessive. However, if we look only at projects dealing with the UK from 1980 until the present day, as in Figure 9, we find that there were 55 publicly-funded projects, of which 49% looked at no specific form of extremism, while 35% looked at far-right extremism, and 15% looked at Islamist extremism, with 7% looking exclusively at other forms of extremism than the top two (note again that percentages may fail to sum to 100, as some projects focused on multiple forms of extremism, e.g. both Islamism and on the far right). Excluding studentships from the total does little to change that pattern, leaving 32 publicly-funded projects, of which 53% looked at no specific form of extremism, while 28% looked at far-right extremism, and 12% looked at Islamist extremism, with 9% looking exclusively at other forms of extremism.

Figure 9: Funded extremism projects focusing on the UK from 1980 onwards by form of extremism studied, 2018-2022

Thus, when the focus is on the UK of the present day and the very recent past, there appears to have been little publicly-funded research focusing on specific forms of extremism other than that of the far right. Indeed, if we discount studentships, all such research identified via this study’s data collection strategy was funded by the CCE — with the exception of a single high-value project focused on Incels (i.e. Regehr 2022-2024, discussed above).

2.4 Discussion

Perhaps the first finding to note is the small number of publicly-funded studies of extremism, and the very low percentage of public research funding which appears to be directed towards such study. Although it has been acknowledged that some funded projects may have been inadvertently left out of the sample for technical reasons or as a result of human error, and also that one provider of mostly small grants (i.e. the British Academy) could not be included in the study because of data availability issues, the true figures are unlikely to be much higher than those found to be through the methodology followed here. This is not necessarily a bad thing: whether extremism research has received too much, too little, or the right amount of public financial support is essentially a political question on which it would not be appropriate for this report to comment.

The next finding to note is that, at least as represented in the sample analysed here, publicly-funded studies of extremism appear to have a tendency not to focus on any specific form of extremism. For example, there are studies of ‘extremist’ online communication or of ‘extremist’ recruitment that do not specify which form or forms of extremism they will investigate. Moreover, where studies in the sample do specify a particular form of extremism as being of interest, it tends to be right-wing extremism that they focus on — at least when they are looking at the UK of the present day or the recent past. Again, whether this is or is not as it should be is essentially a political question, and, as such, outside the scope of this study.

It should be acknowledged that projects which do not concern any particular form of extremism may still be useful: for example, a number of such projects which were included in this study focus on British counter-extremism policy, or on processes such as radicalisation in the abstract. Nonetheless, we can still ask whether there are enough detailed studies of specific extremist movements and organisations, or of policy responses undertaken in relation to these, being carried out. That question cannot be addressed here, but this study has at least served to establish that, if such research is underway, it appears likely to be underway with little support from the UK’s public research grant infrastructure — especially where the topic is Islamist extremism in the contemporary UK.

This brings us to the question of whether the apparent hierarchy of forms of extremism, with right-wing extremism at the top and Islamism in a distant second place (unless we consider the remoter past, or other parts of the world) is as it should be. Whether it is or is not is, again, a political question. However, it is perhaps worth recalling the observation, by the Independent Reviewer of Prevent, that ‘[i]n the years since the [Islamist] 2017 Westminster Bridge attack, the vast majority of realised and foiled [terror] plots have been Islamist in nature’, and that, at the time when the independent review was conducted, ‘80% of the Counter Terrorism Police network’s live investigations [we]re Islamist, while 10% [we]re Extreme Right-Wing’ in nature (Shawcross 2023, 14). There may, of course, be very good reasons for publicly-funded research on extremism in the present-day UK which concerns specific forms of extremism to focus primarily on the UK’s second-greatest present-day terror threat, and only secondarily on the UK’s primary present-day terror threat (study of which appeared to be funded, not only through a far smaller number of grants, but also through grants that were exclusively in the lowest financial bracket). However, if the intention was not to produce such an outcome, funders and stakeholders might wish to consider means by which to achieve a different balance of funded research, and, in this light, it is perhaps worth noting that CREST — a body set up specifically in order to study security threats to the UK — appears in recent years to have funded exactly as many studies of the Incel movement, which is not regarded as a terrorist threat in the UK (Shawcross 2023, 53), as of the UK’s principal terror threat.

No criticism of the funding bodies themselves should be read into this. Whether the relative proportions of funded research accounted for by various forms of extremism are regarded as appropriate or not, it is impossible to know whether patterns associated with particular funders are better explained by biases in the selection process or by the research interests of the communities which typically apply to those funders for support. That is: if a particular funder very rarely supports a particular kind of research, that might be because its selection procedures result in a high rate of rejection for applications for grants in the service of such research, or it might alternatively be because it receives low numbers of such applications in the first place, whether because researchers carrying out such research have other sources of funding which they tap into preferentially, or because they do not consider themselves to need funding for such research, or because they perceive (rightly or wrongly) that their applications would be unlikely to succeed. Thus, the lack of studies of certain forms of extremism in certain contexts may have many potential explanations, whether relating to the peer-review process, to the nature of the applications submitted for review, or to something else entirely.

In this context, it may be worth recalling the observation that ‘[m]any [counter extremism] practitioners who wish to focus on the principal terror threat to this country . . . find themselves viewed with suspicion even by colleagues’ (quoted Shawcross 2023, 101): if similar pressures operate within the extremism research community, it may be that researchers simply choose not to submit proposals for funded projects looking at Islamism in order to avoid negative judgements from their peers (potentially including their peer-reviewers). The current study can provide no insight into that possibility (although Study II, below, attempts to do so). However, it is noted that a recent survey of university staff found that 9% of academics would give what they perceived to be a left-wing grant application a lower rating, and that 22% would do the same for what they perceived to be a right-wing grant application (Adekoya, Kaufmann, and Simpson 2020, 64). If research on right-wing extremism is understood to be ‘left-wing’, while research on Islamist extremism is understood to be ‘right-wing’, and research on ‘extremism’ in general is perceived to be politically neutral, this might explain the dominance of projects focused firstly on no specific form of extremism and secondly on right-wing extremism.

In this connection, it is observed that, where grant applications are assessed by calculating a numerical average of ratings across a panel of peer reviewers, with only the very highest-scoring proposals going forward — as at CREST and the UKRI funders — even a single negative review will generally be sufficient remove a project from contention. If roughly 9% of potential peer reviewers would discriminate against a proposed study of the far right for being ‘left-wing’, then, given a standard ESRC panel of three peer reviewers (UKRI, n.d.b), the probability of such a proposal’s encountering at least one such reviewer is around 25%, equating to odds of approximately one to three, and if roughly 22% of potential peer reviewers would do the same against a proposed study of Islamism for being ‘right-wing’, then the probability of such a proposal’s encountering at least one such reviewer is around 53%, equating to odds of approximately one to one.

Academic journals also employ peer review, of course, but they usually have higher success rates, and in any case do not typically make decisions on the basis of a numerical average, instead requiring editors to adjudicate between contradictory reviews. This would not necessarily eliminate bias, but it would at least ensure accountability for any bias which remained.

Here it is also perhaps worth noting that grant applications are typically only subject to single-blind review. This is a form of peer review in which the identity of the authors or applicants is known to the reviewers at the time of review, but the identity of the reviewers remains permanently confidential. Studies of academic journal and conference peer-review processes have found that, under a single-blind system as compared to what is usually considered the gold standard in academic publishing, i.e. the double-blind system where author identities are confidential at the time of review, ‘reviewers may be [negatively] biased towards authors that are not sufficiently embedded in their research community’, thus restricting the advance of knowledge by limiting the influx of new ideas (Seeber and Bacchelli 2017; see also Tomkins, Zhang, and Heavlin 2017). Doubleblind peer review may not be practical for grant applications, given that applicant curricula vitae and publication histories are an important component of the applications themselves. However, a further alternative exists in the form of open peer review, in which the identity of the reviewer is revealed to the community at large on the ethical grounds that ‘it seems wrong for somebody making an important judgment on the work of others to do so in secret’ (R. Smith 1999, n.p.). Early studies in medical and psychiatric journals found that open peer reviews were at least equal in quality to double-blind peer reviews (Rooyen et al. 1999; Walsh et al. 2000), but the main advantage of open peer review is simply that identification gives reviewers ‘skin in the game’ (Haffar, Bazerbachi, and Murad 2019, 673), ensuring that they may be held accountable for any bias which they might display: a consideration which may have special importance in a field with such potential for ideological conflict as extremism studies.

Whether research on specific forms of extremism is indeed perceived in ideological terms is a question to which Study II shall return. In the meantime, it is observed that anti-fascism has been argued to be such a key element of progressive political identity as to constitute the very ‘core of left-wing consciousness’ (Diner 1996, 124), while a report by a British counter-extremism think tank both identified Islamophobia as a characteristic of the political right (HNH 2019b, 3; 2019a, 22, 24; Lowles 2019, 8) and appeared to blame its prevalence on public consciousness of Islamist terror attacks (HNH 2019b, 3; Carter 2019, 14, 16). A more recent report led by a researcher affiliated with a UK civil society organisation also asserted that, in the UK, ‘[t]he stereotyping of Muslims as terrorists and extremists [by the far right and the centre right] has fed into dangerous government decisions and policy that have targeted and stripped Muslims of basic rights’ (Syeda and Molkenbur 2023, 12–13). This study cannot attempt to assess the validity of such claims. Instead, it simply offers them as evidence of the political battlefield into which researchers may be perceived (and may understand themselves to be likely to be perceived) to sally forth in proposing to study specific forms of extremism, rather than ‘extremism’ in general: a topic about which more shall be said in Study II. The suggestion made here is that, even if the Scylla of alleged anti-progressive ideological discrimination presents less of an anticipated risk than the Charybdis of alleged anti-conservative ideological discrimination, the optimal strategy would still be to avoid mentioning anything that might conceivably fall afoul of either — for example, by putting together a proposal which addresses ‘extremism’ in the abstract, i.e. without giving any suggestion that some particular form of extremism might be a focus.

Given that the CCE has so far only issued a single call for funding proposals, it is remarkable that it was found to have funded the largest number of non-studentship projects, and indeed all included non-studentship studies of forms of extremism other than those of Incels and the far right as manifest in the UK since 1980. It is, however, important to recognise that the sums awarded by the CCE were small: indeed, there were UKRI-funded projects whose funded value exceeded that of all CCE-funded projects combined. Large grant-supported projects can potentially achieve a great deal more than smaller ones, with members of staff devoted to multiple workstreams over extended periods of time. For example, the largest grant included in this study — identified as relevant because of its focus on terrorist incitement alongside a number of social problems less directly associated with extremism — will run for four years, and involve production of a wide range of outputs. By contrast, lower-value grants are in many cases sufficient only to support a short programme of activities designed to share existing knowledge, or to facilitate some specific activity, such as travel to a location where fieldwork or archival research will be carried out. But for scholars not belonging to large, permanent research teams, the stitching together of a succession of such grants may be crucial to their production of knowledge and development of expertise. This is to say that, while large grants have a special importance, both large and small grants are important to the research ecosystem, with each having a distinct role to play.

In context of its potential to become an important supporter of small projects on extremism, the author of this study notes the CCE’s achievement of near balance between Islamism and right-wing extremism in the studies which it funded through its open call. This balance is easily be explained by the terms of that call, which specifically requested projects addressing a range of specific forms of extremism. For example, applicants were invited to submit proposals for studies of the far-right group, National Action, and the Islamist group, Al-Muhajiroun (CCE 2019). It is noted that calls for funding proposals from CREST tend to be far more general, with titles such as ‘Evaluating the cumulative impact of HMG’s counter-terrorism communications’, ‘Contagion of extremism’, ‘Environment and interventions’, and ‘Conspiracy theories and extremism’ (CREST 2021, 14–16). It is observed that, if very general proposals have an advantage at peer review over those which mention specific forms of extremism, they may tend to win out unless they are excluded by the terms of the call — regardless of whether their advantage consists in reduced potential for ideological disagreement or simply in an academic preference for the abstract and the theoretical.

That said, it should be acknowledged that the ESRC also achieved near-parity between Islamism and right-wing extremism in terms of number of projects funded, without having explicitly called for studies of particular groups — although apparently also without awarding a single non-studentship grant to a study of Islamism in the contemporary UK or in the UK of the recent past. While it is possible that such grants were awarded but did not come to light as a result of the methodology employed here, their absence from the sample studied here suggests that they are likely to be rare at best. Possible reasons for this apparent rarity have been discussed above, and shall be returned to in Study II.

3. Study II: Qualitative analysis of interviews

Although the first study in this report has provided a description of certain general patterns in publicly-funded research into extremism, it can only offer speculative but hopefully plausible interpretations for those patterns. In talking to extremism researchers and stakeholders, however, an interviewer may elicit explanations of why things happen in the way that they do. The second study presented here is more freeform than the first, consisting of a thematic analysis of a number of semi-structured interviews. Interviewees have been allowed to speak in their own words, as far as possible, with connections drawn between their accounts where points of comparison or contrast emerged.

3.1 Research questions

Study II was designed to answer the following research questions:

- What sort of considerations do UK-based extremism researchers take into account in deciding what to focus on in their work?

- How do UK-based extremism researchers understand the external factors which facilitate or obstruct them in their work?

- To what sort of ideas do UK-based extremism researchers appeal in addressing the question of whether certain areas are underor over-researched?

3.2 Methodology

3.2.1 Selection of research subjects

Potential research subjects were initially identified through the researcher’s personal network, with some additional subjects being suggested by the Commission for Countering Extremism. The list of interviewees was then diversified through searches of UK university and think tank websites for individuals with a specialism in extremism research. Interviewees were contacted via the researcher’s personal email account. Non-response, and problems in scheduling interview times and dates, limited the range of interviewees in ways that would not have been possible to predict. Altogether, 16 researchers were interviewed (ten male and six female), along with a further interviewee based at the Home Office and representing the perspective of a major institutional research stakeholder. No claim can be made that these interviewees constitute a representative sample of the UK extremism research community. However, the sample included both university and think tank employees, and a mix of early-career, mid-career, and senior researchers, as well as a single independent researcher. Some interviewees focused primarily on Islamist or Jihadi extremism, some on right wing extremism, some on the Incel movement, and one on a form of religious extremism other than Islamist extremism. There was considerable crossover between these groups, and one interviewee researched extremism in general, without focusing on any particular form, while another directed research projects on multiple forms of extremism.

3.2.2 Conduct of interviews

Interviews were conducted online, in most cases through the researcher’s personal Google Meet account. Interviews were digitally recorded and professionally transcribed. The schedule of interview prompts is presented in Appendix III.

3.2.3 Analysis of interview data

Emergent themes were identified in interview transcripts. An initial list of 13 themes was narrowed down through merging of smaller themes until six remained for summary and quotation.

3.3 Findings

3.3.1 Contested borders

One of the most important themes to emerge from the interviews concerned the boundaries of extremism studies itself. For example, some interviewees made an explicit case for the study of non-violent extremism to be treated as a core part of the field, arguing that it has been neglected, and some called for extremist crime to be acknowledged as a subject of enquiry, regardless of whether or not it was violent. One spoke as follows:

[R]esearch on non-violent extremism has been always relegated to the footnotes and academic literature, although it is the identity that definitely sparks specific behaviour. So I do believe that more focus on that will be beneficial to understand terrorism itself . . . [but] for many years, it was considered as not relevant. I remember in 2014, when, you know, I was researching on Hizb ut-Tahrir, some people were telling me ‘So why don’t you research Al Qaeda”, or — it wasn’t the time of ISIS — then 2015, right into focus on ISIS. And my stance was, ‘ISIS has almost the same ideology as Hizb ut-Tahrir and it’s one group. But there are so many groups that share the same ideological foundation, they’ve . . . been around since the fifties, but have inspired different terror groups all over the world. And still nobody talks about them. So it’s about time to focus on the ideologies . . . inspiring . . . other organisations.

In other respects, however, arguments or accounts of conflicts over boundaries were more pointed. Several interviewees expressed the view that simply studying Jihadism can result in a researcher’s being labelled as racist or Islamophobic by others in the field, with one of the most senior suggesting that this had caused university-based researchers to avoid researching the topic. Conversely, one interviewee suggested that, in some cases, it may indeed have been Islamophobia that motivated a focus on Islamist extremism:

It’s clearly a priority to understand [Islamist extremism], but I do wonder if there is still somewhat of . . . an element that’s racist, but maybe that’s too strong, but you know, because maybe the kind of far-right white supremacist misogynistic stuff is obviously more likely from kind of white communities and we’re a British country. I do just wonder if it’s less prioritised as a kind of research? Sometimes, I’m not sure. I suspect maybe.

Two interviewees complained of an obligation among extremism researchers to create a false equivalence between Jihadism and right-wing extremism, with one scholar of right-wing extremism arguing that the appearance of equivalence is buttressed through ‘number acrobatics’, for example by counting incidents rather than fatalities. A researcher primarily focused on Jihadism argued as follows:

There’s like a conceptual, artificial manufacturing of equality . . . A few years ago, you’d have to do two slides on ISIS or something in your presentation and then two slides on the English Defence League. And it’s like, well, English Defence League, as unpalatable as you might find them, is not a terrorist group, and certainly not a genocidal group. So already, you’re kind of morally and intellectually muddying the water a little bit there.

A more senior researcher argued that this had resulted in relative neglect of Islamist extremism as an object of study:

It’d be hard to sit here and say that there isn’t enough research or focus on Islamist terrorism and extremism. There is a lot of research. But I think [that], proportionate to the threat that it poses in this country from both a terrorism and extremism perspective, possibly there isn’t enough.

On the other hand, several interviewees argued that Islamism had been over-researched, with one explaining as follows:

I would say, . . . we really went down a radicalisation rabbit hole when it came to radical Islam, to a degree that was — considering, considering the impact on broader society, and to — considering, I would also say, the security risk, it’s an over-researched area.

Although some of the people to whom the researcher spoke emphasised the greater physical danger posed by Jihadis, this interviewee viewed that as a misleading argument, as no form of extremism poses a particularly great physical threat to the UK population, as compared to other threats:

There’s no doubt [that the focus on Islamism] was a reaction to the threat. [But] also, it’s also a reaction to the priority that’s put on it. [T]he actual threat in terms of human life, for example, is often not proportional to where that threat lies in the priorities of government. And it depends on a whole series of political reasons, initiatives, initiatives, or considerations. . . [T]here’s a snowball effect that happened, that is not, certainly in terms of terrorism, not proportional to the threat to human life, for example, that is represented in the UK. [T]here are few countries where you can say terrorism really represents a threat to the daily life and functioning of a country. Iraq would have been one of them, Afghanistan would be another. But in most countries, and in most Western countries, it doesn’t challenge the functioning of society. But we decided that it represented a major threat to our national security. And that had a huge effect on the next twenty years.

This viewpoint (about which more will be said below) emphasises that the question of which extremist threats should be researched is always political, and cannot be answered by a simple appeal to numbers. In addition to extremism researchers’ apparent frequent reliance on funding from state agencies, this implies that the field itself has an inherent relationship to politics which may subject researchers operating within it to ideological conflicts of a more overt kind than would be likely to be encountered in many other fields of study. The consequences of the field’s politicisation were emphasised by two senior think tank researchers. One gave the following characterisation of the field as a whole:

The research landscape is also slightly drawn on political lines. And I think, you know, the kind of, where the focus is slightly reflects your institutional politics. That’s probably as much the case with academics as it is for think tanks as it is for civil society organisations. And so, . . . it’s the threat from Islamist groups that have insidious sort of activities within communities in the UK, or whether it’s looking at big national security type threats, whether it’s . . . that Russia is sort of supporting the far right extremist movements across Europe, or whether it’s . . . looking at the sort of creeping influence of far-right populism . . . [and] all of these things kind of sit within the boundaries of extremism as a sector . . . [so] that the challenge is that . . . what you’re focused on reflects your own perspectives on what is important and significant So I think [that] all these things are the sort of subtext to . . . how the funding works [and] how the conversations happen. It’s . . . a very political set of topics that we’re dealing with. And that’s quite . . . hardwired into the approaches that are taken.

The other suggested that the politicisation of the field explained its greater current focus on the far right than on other forms of extremism:

I think probably there’s also a political interest, you know, a lot of young people are left-leaning liberals. And so studying the far right is our generation’s version of fighting the Nazis fighting the good fight. I think you see that a lot in advocacy groups, activist groups, like [REDACTED], where there is a blurring, I think, sometimes of legitimate research, and — well, it’s kind of exposés, isn’t it, which I have mixed feelings about, of the far right — bleeding into political activism, promoting a [left-wing] vision of the world, and not wanting a right-wing vision of the world. So there’s probably an element of of that, as well.

The anxiety that politicisation might be distorting the field was widespread among interviewees. Moreover, a degree of scepticism about the validity of exposé-type research on the far right carried out by activist researchers was also expressed by the other think tank researcher quoted above, who, despite representing an organisation which other interviewees recognised as left-wing, and which maintains connections with ideologically-motivated independent researcher-activists, emphasised the importance of maintaining a separation from such work for the sake of credibility. One scholar of the far right who explicitly identified with the political centre-left went so far as to argue that a damaging orthodoxy was emerging within the research community, with left-wing or progressive politics becoming a prerequisite for study of the far right:

[The assumption is that] you have to be centre-left to work on the far right, or far-left to work on the far right. You can’t be somebody who’s a conservative who’s disgusted by the far right, you’re not welcome. And I think that message is very clearly pushed that . . . you have to sign up to certain values . . . you have to hold these views, and holding these views is a prerequisite to doing the work. . . .