Preventing illness and improving health for all: a review of the NHS Health Check programme and recommendations

Updated 9 December 2021

Applies to England

Foreword

It might seem a distraction to have undertaken an evidence review during a pandemic. However, it is timely, as coronavirus (COVID-19) has revealed the true cost of high levels of underlying chronic disease and its risk factors, accentuated health inequality, and clearly demonstrated the value to society of good health for all.

The NHS Health Check was introduced in 2009 to encourage healthcare professionals to measure and manage the cardiovascular risk burden in the apparently healthy population. It was ground-breaking due to its scale, age range and ambition to treat people before the onset of clinical events. In early 2020, the Secretary of State requested a review to identify ways in which the programme could be developed further to support the NHS prevention agenda, and particularly to reduce inequalities in health outcomes.

Our review found that the NHS Health Check has achieved many of its aims, and millions of eligible people have been assessed. Despite concerns that it would predominantly be taken up by the ‘worried well’, it has been representative of the socio-economic and ethnic mix of the population. The NHS Health Check revealed a surprisingly high level of modifiable risk factors (more than three-quarters of attendees had at least one elevated risk factor) even among people aged under 50. Referral to specialised services was high, even in disadvantaged groups.

However, over the last decade, evidence has emerged that has transformed the understanding of how cardiovascular disease develops, how to predict who will get it, and to how to personalise prevention with earlier intervention. This, together with leaps forward in digital technology, offered a unique opportunity for the review to consider the evidence for a new and different intelligent NHS Health Check to promote and underpin the emerging national wellness agenda.

We have made 6 recommendations that will transform the programme to make it more proactive, predictive and personalised. They are based on 3 objectives:

- to empower people with the knowledge, tools and support they need to manage their own health better

- to reduce inequality in health outcomes

- to provide a portal to a wide range of wellness initiatives

The most important recommendation is a move from a one-off check to a 2-way, longitudinal engagement with people, who should not be passive recipients of care, but actively involved in their own wellness maintenance. An intelligent NHS Health Check does not seek to promote early medicalisation of the population, but rather, through early sustained interaction, to inform, promote and maintain healthy behaviour in all. This will alter trajectories to disease, prevent illness and so reduce the need for later medical interventions.

As people look for new ways to participate in their health and wellbeing, technologies and digital innovations provide the means for improvements. These offer the opportunity to transform all aspects of the NHS Health Check, including accessibility, scale, conduct and delivery. Crucially, a digital solution for the programme facilitates the proposed 2-way longitudinal interaction, incentivisation, as well as connectivity with other existing and future services (such as obesity, long COVID). It also offers the potential to redirect resulting efficiencies to prioritise those at greatest risk, who would benefit most, in order to ‘level up’ outcomes.

Reducing the age at which the NHS Health Check is offered is necessary to alter lifelong behaviour patterns, which are often set early. Starting young is not intended to detect more disease, even though the evidence points to an earlier elevation of risk factors in some people.

We are recommending that the NHS Health Check remains a universal programme available to all eligible people. However, we understand that treating everyone in the same way does not reduce inequality. Local responsibility for local lives should be maintained. Local authorities have knowledge of their communities, infrastructures and connections to existing services. Many local authorities have shown what can be achieved when the ‘proportionate universalism’ approach proposed by Marmot is adopted. Driving up overall participation while prioritising those with the highest levels of unhealthy behaviour and risk factors, will need continued local innovation.

The new NHS Health Check should aim to treat people and not just diseases. It is now clear that the same behaviour and risk factors already measured in the NHS Health Check increase the risk not just for cardiovascular disease but also for conditions such as obesity, diabetes, cancer and dementia. This provides further opportunities for greater health gains. The review recognised the potential benefit of including other increasingly common conditions (such as musculoskeletal and mental health), especially those that have causal links to risk factors or affect an individual’s ability make behavioural changes. However, further consideration should be given to the feasibility, affordability and appetite from people and healthcare providers to expand the content.

Robust, regular evaluation is essential for quality improvement to ensure that the programme remains at ‘the cutting edge’. We are proposing a ‘learning system’, involving collaboration with large-scale UK academic programmes, the National Institute of Health Research and the voluntary sector. This will enable evaluation of innovation, with rapid introduction into the programme, when appropriate and evidence based. In turn, the NHS Health Check can provide an important gateway into existing initiatives within the UK life sciences portfolio. Academic input will be essential at all levels of the programme’s delivery.

It has been a privilege to chair this review, which has been conducted in a uniquely challenging environment. I thank the steering committee, as well as the expert panel and stakeholder groups, for their time, expertise and wisdom. I am also grateful to the Public Health England (PHE) NHS Health Check review team, who carried out research, analysis and writing at a time when their organisation was undergoing radical change.

This is a ‘once in a lifetime’ moment to develop and communicate a ‘new deal’ with the public to empower them to manager their health better. COVID has moved health to the top of everyone’s agenda and demonstrated that it is possible to engage rapidly and effectively, and at scale with the public. We recognise that population health depends importantly on a number of social determinants. However, an NHS Health Check programme that can reduce non-communicable disease by effective prevention, can play a key role at the heart of a new national wellness ecosystem.

Professor John Deanfield, CBE, External chair of the NHS Health Check review.

1. The background to the review

The main points are:

- this review presents a vision for the future of the NHS Health Check programme

- the NHS Health Check was launched in 2009 to reduce people’s risk of ill health from cardiovascular disease

- the government’s 2020 health prevention green paper said that the NHS Health Check had the potential to do more

- this review looked at how the programme might evolve

1.1 The role of this report

This report presents the findings from a review of the current NHS Health Check programme. It has been prepared for government ministers but is also relevant to anybody with an interest in personalised prevention as well as population strategies for preserving good health.

1.2 The NHS Health Check

The NHS Health Check was launched in 2009 to reduce ill-health from cardiovascular disease (CVD), which was then the biggest killer of adults: it still causes 24% of deaths, second to cancer.[footnote 1]

People aged 40 to 74 with no known pre-existing CVD are eligible for an NHS Health Check every 5 years.[footnote 2] It reviews the risks to their health and seeks to reduce the likelihood of CVD-related illnesses by helping them to adopt healthier behaviour, referring them to existing specialist services, or by prescribing medication such as statins.

It estimates their risk of having a heart attack or stroke in the next 10 years and of developing type 2 diabetes. Underpinning this is an assessment of 6 major risk factors that drive early death, disability, and health inequality: alcohol intake, cholesterol levels, blood pressure, obesity, lack of physical activity and smoking. People aged 65 to 74 are also made aware of the signs of dementia.

Since 2013, local authorities have been responsible for the NHS Health Check.[footnote 3] Most checks are carried out by healthcare assistants in GP surgeries. Other providers include community pharmacies and outreach services.[footnote 4]

1.3 Why this review was carried out

The government green paper ‘Advancing our Health: Prevention in the 2020s’[footnote 5] recognised that the NHS Health Check has achieved much in the past decade but has the potential to do more to support the government’s commitment to ensure people enjoy healthy lives.[footnote 6] [footnote 7]

Recent evidence has transformed the approach to preventing CVD, which often begins decades before its clinical problems appear, and results from people’s cumulative exposure to modifiable risk factors.[footnote 8] Even small reductions in these risk factors, by adopting healthier behaviour from an early age, can dramatically reduce the lifetime risk of heart attacks and strokes.

Investing in prevention brings better returns than waiting to deal with the later clinical complications. The NHS Long Term Plan aims to prevent up to 150,000 heart attacks, strokes, and cases of dementia over the next 10 years[footnote 9]. This review considers how the NHS Health Check can help achieve this milestone.

The review is also timely: the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the negative effects of poor background health and health inequality – an enhanced NHS Health Check is well placed to tackle both these issues.

1.4 Scope

In 2020 the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) commissioned PHE to undertake an evidence-based review of how the NHS Health Check might evolve to deliver greater impact. The review was due to start on 1 April 2020 and conclude within a year. However, the COVID-19 response delayed it to 1 July 2020. The review work was completed by PHE in September 2021. On 1 October 2021, responsibility for national oversight of the NHS Health Check programme and for publishing the findings of the review transitioned to the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID).

The scope of the review has been broad, taking in the content of NHS Health Checks, how the service is delivered and how it links to the wider healthcare system.

As set out in the terms of reference,[footnote 10] the specific issues to consider were:

- the benefits and limitations of the current service

- the eligible population

- the potential for further physical or mental health conditions

- how the checks are delivered – in particular, a digital option

- the potential for more personalised focus on risk

- how to improve uptake

- how to improve follow-up

- how research can support long-term development of the service

The review assumes that the NHS Health Check programme will continue to be commissioned by local authorities.

1.5 Governance

The review was carried out by PHE. Professor John Deanfield was appointed by PHE and DHSC as the external chair of the steering group.

The multi-agency steering group oversaw the direction of the review, ensured it complied with the terms of reference and agreed its recommendations. The members of the steering group are listed in annex A.

An external panel of topic experts also provided advice and feedback on the data and other evidence used by the review and on the draft recommendations. The members of the expert panel are listed in annex A.

1.6 Approach

This review advises how the NHS Health Check programme might be transformed so that its headline outcomes – preventing ill health and reducing health inequality – are maximised over the next decade and beyond. This advice is based on data and information from several sources, including:

- academic literature and published reports

- data and evidence from the current NHS Health Check programme (annex B)

- data on the occurrence of risk factors driving the burden of non-communicable disease (annex C)

- the knowledge and experience of a broad range of stakeholders (annex D)

- health economics model (annex E)

1.7 Limitations

PHE had to deliver the review rapidly, which limited its ability to commission new evidence and fully analyse all the NHS Health Check data. Some evidence was identified via stakeholder engagement rather than a formal systematic review process.

A microsimulation model estimated the health economic and equity impact of the current NHS Health Check programme, and the impact of further investment to deliver specific scenarios. The limitations of this model are described in annex E. In particular, it assumes every eligible individual is invited for an NHS Health Check. It produces results over a 20-year period and so does not indicate cost-effectiveness over a person’s lifetime.

Although the controls introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic reduced the review’s ability to engage with stakeholders in traditional ways, online methods made it easier to contact a wider range of stakeholders from organisations across England.

2. What the review found

The main points are:

- the NHS Health Check programme has largely achieved its aims, reaching 2 in 5 eligible people, including those at higher risk of disease, and delivering better outcomes for attendees

- multiple opportunities exist to improve the NHS Health Check across the entire pathway

- people’s risks set in early, so behaviour change is needed sooner

- a wider view of health could address the current burden of disease

- greater use of technology may help target, reach and personalise the NHS Health Check for individuals

2.1 The benefits and limitations of the current service

The evidence set out in annex B shows that the NHS Health Check is broadly achieving its aims. It has scaled-up a standardised check, reaching 41% (6,466,090) of eligible people between 2015 and 2020, and helped to shift the focus from illness to prevention. Stakeholders agree, and value the opportunity to concentrate efforts on preventing disease and identifying it early (annex D).

The 6 risk factors assessed as part of a check remain the biggest contributors to the burden of disability and death from non-communicable disease among adults in England (annex C). The NHS Health Check has shown that a national prevention programme to tackle non-communicable disease and its risk factors is not only possible, but that it also results in better risk-recording, more disease detection and favourable rates of advice, referrals and follow-on testing (annex B).

It has also engaged people from more deprived black and ethnic minority groups, though further work is needed to ensure that across all ethnic groups those in the 10th most deprived engage with the NHS Health Check (annex B).

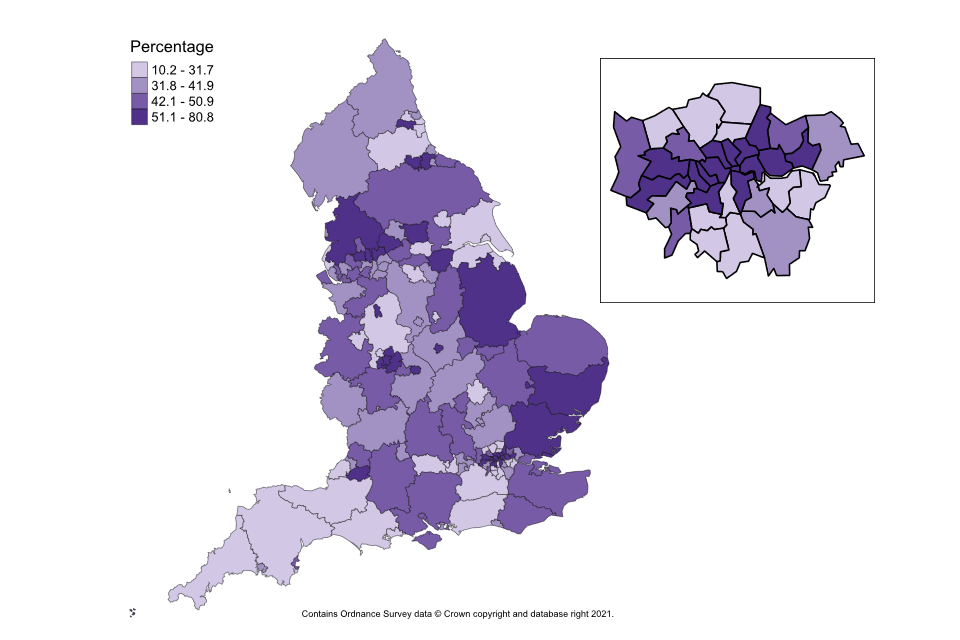

Despite this, big variations remain between local authorities in terms of offers, uptake and completions (figure A) of the NHS Health Check (annex B).

Figure A is a map of England broken into local authority areas to show the proportion of people completing an NHS Health Check between 2015 and 2020. It shows whether a local authority is in one of the 4 following categories: 10.2 to 31.7%, 31.8% to 41.9%, 42.1% to 50.9% or 51.1% to 80.8%. The data for this map is available in annex B, appendix 1.

Figure A: variation in proportion of eligible people having a NHS Health Check by local authority across England, 2015 to 2016 and 2019 to 2020 (annex B)

Even just a few years after an NHS Health Check, attendees tend to show better health outcomes, including lower levels of hospital admissions and death from heart attacks and strokes (annex B).

Economic modelling suggests that, compared to no provision, and from a societal perspective, every £1 spent on the current NHS Health Check programme achieves a return of £2.93. It is also likely to reduce absolute health inequality by 2040 (annex E).

2.2 The eligible population

For some risk factors, such as smoking and cholesterol, exposure in early adulthood raises the risk of ill-health even if later behaviour-change reduces the level of risk.[footnote 11] This suggests that if people change and sustain their behaviour earlier, it will reduce their overall risk of ill-health in later life more. The economic modelling indicates that lowering the eligible age to 30 is likely to reduce absolute health inequality (annex E).

Stakeholders view the universal approach of the NHS Health Check as a major success. They also broadly agreed that people would benefit from engaging with it earlier in life. In addressing inequality, they differ on whether it is best to engage with everyone at a younger age or just those who would benefit most, and they are concerned about the practicality of extending the check to more people (annex D).

2.3 Adding further physical or mental health conditions

Several risks and conditions not currently covered by the NHS Health Check contribute heavily to the burden of non-communicable disease. The potential for adding some of these conditions was considered, along with the underpinning evidence (annex C).

Common mental health conditions (depression and anxiety) and musculoskeletal health issues have the strongest case for inclusion. Both are associated with a large burden of morbidity, as described in annex C. Validated tools for assessment and treatments are available, but further work would be needed to test how the NHS Health Check might use these and the impact on wider NHS services.

Many stakeholders suggest the NHS Health Check should take a holistic view of people’s health, moving away from its primary focus of CVD prevention towards preventing non-communicable disease. The idea of the NHS Health Check programme taking on a wider range of risks and conditions has broad support, though some local authority commissioners wonder if extra resources would be available (annex D).

2.4 The potential of a digital option

Local authorities spent £48 million on commissioning NHS Health Checks in 2019 to 2020.[footnote 12] By far the largest provider of checks is general practice. Other providers such as community pharmacists or outreach teams offer checks, but their ability to send invites is often hampered by a lack of data on eligible people (annex B).

The technology that can support delivery is being used more widely – for example, text message invitations, and bespoke IT systems to guide practitioners during the check. However, only one local authority reports offering a digital option for people to self-complete a check (annex B).

The review looked at how a digital service could improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the NHS Health Check.

For patients, digital health can mean better access to information and care, greater convenience, and more opportunities for control of their own health and for shared care. For the health and care system digital health can mean more effective delivery of care, better outcomes and reduced costs.[footnote 13]

Nine in 10 UK households have access to the internet, and 78% of people go online using a mobile device.[footnote 14] The use of digital approaches in delivering health services has been transformed during the COVID-19 pandemic, demonstrating that the technology can be deployed at pace and scale.

Evidence from the academic literature on digital technology in the NHS Health Check is limited.[footnote 15] [footnote 16] International examples suggest that digital assessments consistently attract the more affluent group.[footnote 17] However, when backed by community support that helps people complete them, less affluent and ethnic minority groups use digital assessments more often.[footnote 17]

The public has an appetite for digital health solutions, as shown by the 5 million completions of the Heart Age Test (HAT).[footnote 18] When coupled with national marketing, more men, people aged 30 to 39 and 50 to 59, as well as those living in the least deprived areas, completed HAT.[footnote 18]

Many stakeholders feel it is important that the NHS Health Check should make more use of digital technology. They mention the potential benefits of wider accessibility and better efficiency.

They also say it should not create digital exclusion or more health inequality (annex D). Eleven million people (20% of the UK population) lack basic digital skills, or do not use digital technology at all. These are likely to be older, less educated and in poorer health than the rest of the population.[footnote 13] It is essential that the NHS Health Check continues to offer a service that meets the needs of those who may be digitally excluded.

2.5 A more personalised focus on risk

The people attending an NHS Health Check have high levels of modifiable risk factors that vary with ethnicity, gender and age. Figure B shows the proportion of NHS Health Check attendees by deprivation decile (where 1 is most deprived and 10 least deprived). It shows that the most deprived are more likely to have multiple risk factors than the most affluent.

Figure B: number of risk factors by deprivation among attendees (annex B)

| Deprivation decile | No risk factors | 1 risk factor | 2 risk factors | 3 risk factors or more | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Most deprived | 11 | 29.1 | 32.2 | 27.9 | 100 |

| 2 | 13 | 31.1 | 31.2 | 24.7 | 100 |

| 3 | 13.9 | 32.8 | 30.7 | 22.6 | 100 |

| 4 | 14.7 | 34 | 30 | 21.3 | 100 |

| 5 | 15.4 | 35.2 | 29.6 | 19.8 | 100 |

| 6 | 16.3 | 36.4 | 28.9 | 18.4 | 100 |

| 7 | 16.7 | 37.2 | 28.6 | 17.6 | 100 |

| 8 | 17.5 | 37.9 | 28 | 16.6 | 100 |

| 9 | 18 | 38.5 | 27.7 | 15.7 | 100 |

| Least deprived | 19.2 | 40.2 | 26.8 | 13.8 | 100 |

| Unknown | 20 | 50 | 10 | 20 | 100 |

Interventions are more likely to be offered to deprived people and those from black and ethnic minority groups with a higher CVD risk, suggesting that providers are tailoring their delivery of checks to these groups (annex B).

More than half of people still decline a referral to a behavioural intervention (annex B). This suggests more could be done to personalise the check and the support for behaviour change.

Figure C shows the number of people in each 5-year age band between 40 and 74 who are either at high 10-year CVD risk or have a low 10-year CVD risk but high lifetime CVD risk or a low 10-year CVD risk and low lifetime CVD risk.

It shows that a CVD assessment that looks ahead to just the next 10 years can give a low score for younger people even if they have high levels of modifiable risk factors. While medical treatment such as statins may not be appropriate for them, the risk is that their 10-year risk score could give false reassurance. Instead, a focus on their lifetime CVD risk would give them a more accurate picture of their chance of having a heart attack or stroke and their opportunity to reduce this.

Figure C: attendees’ 10-year and lifetime CVD risk by age (annex B)

| Age group | Low 10-year risk and low lifetime risk | Low 10-year risk and high lifetime risk | High 10-year risk | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 to 44 | 376,334 | 373,783 | 10,810 | 760,927 |

| 45 to 49 | 368,456 | 350,739 | 33,096 | 752,291 |

| 50 to 54 | 359,028 | 311,144 | 82,832 | 753,004 |

| 55 to 59 | 268,845 | 191,311 | 157,501 | 617,657 |

| 60 to 64 | 176,462 | 88,755 | 258,864 | 524,081 |

| 65 to 69 | 82,798 | 19,193 | 354,356 | 456,347 |

| 70 to 74 | 3,603 | 117 | 122,959 | 126,679 |

Providers commonly prioritise NHS Health Check invitations by age. Age has the greatest weighting within the 10-year CVD risk calculation, so this serves as a simple proxy for identifying the people likely to have the greatest short-term clinical risk. Other important definitions of need include deprivation, ethnicity and geography. To improve prioritisation, these factors also need to be considered (annex B).

2.6 Improving uptake

One in 2 eligible people have not taken up the offer of a NHS Health Check, which presents an opportunity for improvement (annex B).

Studies show that the way people are invited and how the service is delivered can affect the uptake.[footnote 19]

A barrier to attending can be removed by offering appointments before or after work.[footnote 20] Inviting people by phone or when they are at a GP surgery for another reason have increased uptake, as have text message reminders.[footnote 20] Stakeholders suggest accessibility can be expanded by using pharmacies or community settings, such as libraries and religious centres (annex D).

Uptake is also affected by people’s knowledge and perceptions. If they know about the programme, understand its value, and see it as a chance to be reassured about their health or take positive action, they can be more likely to attend.[footnote 20] Stakeholders feel that better marketing of the NHS Health Check could improve engagement (annex D).

A lot has been learned during the COVID-19 vaccine programme about ways to raise uptake, such as the role of community champions.[footnote 21] It would be worth looking at how these valuable insights might be transferred to the NHS Health Check.

Health economic modelling for raising the uptake of the NHS Health Check among the most deprived did not show an extra reduction in absolute health inequality. The likely reason for this is the relatively small difference in uptake compared to the current NHS Health Check.

In contrast, estimates show that raising overall uptake to 75% and 90% could give an extra return on investment: respectively, by 2040 for every £1 spent, £2.95 or £3.27. Achieving a 90% uptake is also likely to further reduce absolute health inequality (annex E).

2.7 Improving follow-up

The academic literature provides evidence on the enablers and barriers to behaviour change.[footnote 20]

Practitioners play a vital role. Their ability to help people make behaviour change often depends on their beliefs about the benefit of the check, their capability to support change, and their confidence that people will change (annex B).

Other potential barriers are structural factors, such as staff training, adequate time to deliver a check, effective computer systems, and the availability and capacity of funded referral services (annex B).

For the individual, the barriers to change are a poor understanding of the 10-year CVD risk score; pressure rather than help from a practitioner; a belief that genetic disposition drives behaviour; practical issues in taking up and sticking with interventions; access to services; cost and time.[footnote 19] [footnote 20] [footnote 22]

Stakeholders feel that to encourage real behaviour change, the follow-up should be ongoing, based on the needs and aims of each person, and integrated with other services. To help people understand the risks to their health, they should be given a report to take away.

Better follow-up should improve the reach and effect of alcohol-reduction services, physical activity programmes and weight-loss interventions. Health economic results suggest that, from a societal perspective, every £1 spent in further investment would give a return of £5.18. From a health and social care perspective it is likely to be cost effective.

2.8 Research support for long-term development

The research priorities published in 2015 set out 5 strategic considerations and 30 questions.[footnote 23] Since then, research and evidence published on the NHS Health Check has grown, including 4 studies[footnote 24] [footnote 25] [footnote 26] [footnote 27] using national data. Nevertheless, the recent update to the rapid evidence-review[footnote 19] highlights gaps in understanding, and the work of the review reveals an opportunity for further research to learn more about the impact of digital delivery models.

Growing evidence points to the potential of genomics to improve the precision of CVD risk prediction.[footnote 28] However, it is essential to understand the clinical utility and evidence of polygenic risk assessment on behaviour change. Research programmes such as Our Future Health offer an opportunity to evaluate its application.

Stakeholders would value improved data collection and a wider set of performance metrics, including on how well the service is reaching those who would benefit most, how far it influences behaviour and, ultimately, its impact on health outcomes (annex D). To date, only data on the number of checks offered and completed has been routinely available for each local authority, which has hampered quality assurance and the evaluation of the NHS Health Check programme.

3. The review’s 6 recommendations

The 6 recommendations are to:

- build sustained engagement

- launch a digital service

- start younger

- improve participation

- address more conditions

- create a learning system

3.1 A new NHS Health Check

The current NHS Health Check focuses on identifying CVD risk factors or disease, then referring people to behaviour-change services or treatment.

The findings from this review have resulted in a vision for a new ‘intelligent’ NHS Health Check that engages more directly with people and places individual behavioural change at its heart. It has the potential to become an entry point to a national prevention service for non-communicable disease.

These 6 recommendations are designed to work together to transform the current service and to optimise its impact as part of a national strategy for health improvement that also addresses the wider determinants of health.

The goals of the transformed NHS Health Check are to:

- engage people in maintaining good health and preventing non-communicable disease by empowering and supporting them to understand their risks and to take early, sustained action to reduce those risks

- reduce the health inequality that results largely from different levels of major non-communicable diseases and their underlying risk factors

- act as a gateway to the wider wellness ecosystem by integrating the service with other non-communicable disease prevention programmes and by promoting joint-working and cost-sharing

1. Build sustained engagement

Recast the NHS Health Check around an ongoing relationship with individuals rather than delivering an isolated check. Ensure a clear focus on promoting lasting health and wellbeing, backed-up by effective communication of risk, support for behaviour change, and connections to other services that people need. As part of this:

- engage OHID, Health Education England, local government and other partners to set up a training offer for NHS Health Check staff to put more emphasis on long-term behaviour change

- ask local authority commissioners to ensure their contracts with providers require staff to take training that includes behaviour-change techniques

- ask OHID to convene an expert group to make recommendations on how an individual’s risk can be communicated most effectively via the NHS Health Check

- ask integrated care systems and health and care partnerships to ensure there is sufficient provision of NHS and local authority interventions, such as digital weight management, type 2 diabetes prevention, smoking cessation, social prescribing, incentives to support health improvement, and optimising prescribing, and to integrate these with the NHS Health Check

The supporting rationale:

- exposure to risk factors such as smoking, blood pressure, cholesterol and obesity drives the development of CVD and other diseases from early life and is preventable

- lifetime risk can now be assessed, and personalised recommendations made, based on the trajectories of individual risk factors

- optimal outcomes require ongoing measurements and engagement with people, which will sustain the small improvements that result in increasing dividends to health

- communicating risk alone does not lead to sustained benefit; support for behaviour change is also needed

- regular interactions that help people measure and understand their health risks will build awareness and motivate them to change – tackling unhealthy behaviour and resulting diseases requires a whole system effort and the NHS Health Check should be seen as part of this

- NICE guidance states that people older than 40 should have regular reviews of their CVD risk

2. Launch a digital offer

Improve the accessibility and efficiency of the NHS Health Check via a digital offer. This will support a sustained relationship with the public. Retain a non-digital approach for those people who require or request it. As part of this:

- OHID, in partnership with NHSX, should develop and pilot a new digital offer, which local authorities can add to their local NHS Health Check delivery; this secure service would let people share information on their health and wellbeing over the long term, assess and communicate their health risk, and offer them personalised expert advice and tailored support, which may include referrals to other digital and non-digital health programmes, services or clinical treatment – primary care should also have easy access to the data from the digital NHS Health Check

- ask commissioners to ensure that, where appropriate, the digital offer is used as part of the NHS Health Check

- NHS Digital should provide an annual data extract and publish quarterly reports for commissioners

- promote improved data-sharing between the NHS and local authorities to make it easier to identify eligible people and invite them to use the new NHS Health Check

The supporting rationale:

- the NHS is committed to offering digital information and services wherever appropriate, and there is merit to the NHS Health Check being a part of a broader NHS health platform

- a digital NHS Health Check option could increase access and uptake, improve communication and engagement, providing people with greater control of their own health and shared care

- it would allow integration of the NHS Health Check with other digital health services and can mean more effective delivery of prevention, better outcomes and reduced costs

- access to national data from the NHS Health Check is essential for evaluation of the programme and continuous quality improvement

- savings from digital efficiencies can be redirected to provide a non-digital service for people who are digitally excluded

3. Start younger

Make the NHS Health Check available to people from a younger age, when they are 30 to 39. Preventable risk factors such as smoking, high blood pressure, cholesterol and obesity drive the development of CVD and other diseases from early life. As part of this:

- expand the eligibility of the new NHS Health Check to include people aged 30 to 39

- assess the impact of this change – how it affects people’s understanding of their health, behaviour and levels of different risk factors – and use these insights to customise the approach to ensure maximum impact

The supporting rationale:

- the NHS Health Check aims to prevent disease or slow its progression, so including younger people is appropriate even if their short-term risk is low

- unhealthy behaviour and the related risk factors start early in life and result in cumulative damage, leading to a risk of later disease and cardiovascular events, such as heart attacks and strokes – early sustained intervention can produce greater benefit than more intense treatments later in life

- most health outcome inequality is driven by non-communicable disease levels, so a prevention approach of early assessment and management is an opportunity to ‘level up’

- NICE guidance recommends assessing diabetes from the age of 25 in people from ethnic minority groups known to be at high risk

4. Improve participation

Design and manage the NHS Health Check to improve participation by all eligible people, but especially the people likely to benefit most – those who live in more deprived areas, those from black and minority ethnic groups who are more susceptible to CVD, and men. As part of this:

- consider a national marketing campaign to raise public awareness of the NHS Health Check as part of the government’s COVID-19 recovery plans

- make the NHS Health Check easier to access, including a wider range of delivery settings, drawing the lessons from the national COVID vaccination programme

- ask OHID to work with local government to support commissioners to develop new ways to improve uptake and outcomes

- develop and publish new performance measures

- consider giving local authorities graduated financial incentives for making progress against these measures

The supporting rationale:

- uptake and outcomes vary widely between areas, with some local authorities particularly successful at reaching those who benefit most

- barriers to engaging with checks include the location and timing of appointments, a low understanding of their value, and health beliefs

- commissioners currently have few incentives to collaborate or use scarce resources to improve outcomes, and overall transparency is insufficient

5. Address more conditions

As a first step towards a more holistic view of the health of the individual, consider the evidence on addressing the risk of common mental health and musculoskeletal conditions through the NHS Health Check. As part of this:

- set up a working group to assess the benefit, cost and feasibility of expanding the scope of the NHS Heath Check – draw members from OHID, local government, the NHS, the Royal Colleges, universities, relevant charities and members of the public

- work with commissioners to test any expansion of the content of the NHS Health Check, including feasibility and impact on staff and their workloads

- the NHS Health Check is likely to evolve further in future, with the addition of components on other risks and conditions where there is evidence of positive impact and good value for money

The supporting rationale:

- the risk factors that promote CVD, such as obesity, physical inactivity and smoking, also drive other common diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, dementia and some cancers – these risk factors are already captured in the NHS Health Check

- mental and musculoskeletal ill-health make up a large part of the burden of preventable disability and are not currently addressed by the NHS Health Check; they can affect people’s ability to change their behaviour and improve their health

- assessment tools and evidence-based interventions for common mental health disorders (anxiety and depression) and musculoskeletal conditions exist and are delivered in a range of healthcare settings

6. Create a learning system

Launch a rigorous, ongoing independent scientific evaluation of the new NHS Health Check. The experience of delivering this service will offer a weight of data and learning, which should be evaluated in partnership with stakeholders. Collaborate with partners such as Our Future Health to test evidence-based innovations for future inclusion in the programme. This will create a ‘learning system’. As part of this:

- ask the National Institute for Health Research to commission studies to evaluate the new NHS Health Check and its digital offer – these should assess effectiveness, medium and lifetime impact on health, effect on heath inequality and cost-effectiveness

- ensure that evaluation results are reflected in any decisions to change the content or delivery of the new NHS Health Check; consider a mechanism to allow the findings to modify the service as swiftly as possible

- OHID will work with public health stakeholders to explore the evidence and opportunities for improving the quality of the programme

The supporting rationale:

- the science of prevention is developing rapidly, with innovations in genetics, biomarkers and imaging; evidence is also emerging from behavioural science research

- novel evidence-based approaches must be evaluated and introduced into the new NHS Health Check quickly and at the right time

4. What it will look like

The main point from this section is that the new NHS Health Check will look different to people using the service and those working in the healthcare system.

4.1 Change for all

The new NHS Health Check will use digital technology and artificial intelligence to reach more people and personalise the service, aiming to prevent the development of disease. It will provide tailored advice for all, and better, sustained support for behaviour change and treatment for those people who would benefit most. Everybody with a stake in the NHS Health Check will see change.

4.2 For people

The risk factors start young and cause cumulative harm.[footnote 29] Early and sustained advice and support can benefit people’s health more than intense and costly treatment later in life.[footnote 30] A central change is that people will start to be invited to an NHS Health Check from the age of 30. They will then encounter a service that takes a wider view of their health and wellbeing. As part of this, they will see:

- not just 5-yearly check-ups, but an ongoing engagement about health and wellbeing, backed-up by regular interaction, including support for behaviour change

- a digital approach that is more accessible and convenient, giving them the freedom to provide information online without the need for an appointment; they will also be able to choose where the physical measurements that are part of a check (blood pressure and blood test) take place; for people who need or want them, face-to-face consultations would still be available

- a gateway to wider wellness and prevention services, avoiding the need to duplicate data, and creating an interactive, holistic view of health

- a greater personalisation via the digital platform that takes account of their individual aims for their health, provides them with choices on how to achieve those aims, and allows them to track their progress

- a level of support adjusted to their need – for those who are motivated and capable, simple feedback and reinforcement messages will suffice; for those who need most support and who would benefit the greatest, more intense support for behaviour change and treatment is available

4.3 For the healthcare system

The NHS Health Check programme will adopt digital technology and be more orientated towards the individual. It will focus on reducing risk and enabling behaviour change across an expanded age group and for a wider set of conditions. It will be delivered more flexibly according to personal need, and will become more efficient and effective, and integrated with other prevention services.

As a result, the NHS Heath Check will:

- benefit more of the population and help ‘level up’ – motivated and capable people will be able to use the digital service, reducing the burden on providers and allowing them to focus face-to-face time on people who would benefit most

- provide primary care services with risk-based analytics with specific actionable information on their patients – this will help with their interpretation of complex data and decision-making

- provide 2-way communication through the digital NHS Health Check to enable ongoing advice, rapid feedback and integration with people’s existing healthcare records – data will be included from physical measurements made at any encounter

- offer a more efficient, personalised approach to prevention, based on people’s individual risk levels and health trajectories

- provide a greater focus on behaviour change via enhanced training and development for NHS Health Check providers

- be integrated with other prevention services to deliver earlier prevention, which will provide lifetime gains and cost savings

- give access to more transparent real-time data that forms part of the primary care record, allowing outcomes to be tracked and the programme to be routinely evaluated

- be able to adopt innovation more quickly

5. The next steps

The main points are to:

- lay the foundation for change and invest in the service

- develop a digital option and publish more performance data

- assess adding extra conditions and inviting younger people

- introduce routine evaluation and incorporate new evidence

5.1 The next few months

Achieving these aims requires immediate action to restart the existing NHS Health Check in all local areas, following its widespread suspension during the COVID-19 pandemic.

As part of this, OHID and local authorities should look to improve the take-up of the current NHS Health Check, reassert the drive to reduce health inequality, strengthen its focus on behaviour change and establish more connections to other services. This will reinforce the current service and lay the foundation for future change. Implementing the recommendations and transforming the current NHS Health Check requires investment.

Governance will need to be established to oversee the transformation, with greater programme management and analytical capacity allocated to deliver the changes.

5.2 The next 3 years

NHSX, with OHID, need to plan, develop and launch a digital service that will be the keystone of the new NHS Health Check. This will include identifying potential crossovers with other digital services under construction and deciding how a digital NHS Health Check will be delivered locally alongside the existing face-to-face service. This will include looking at the risk assessment and how it is communicated, clarifying the referral pathways to behavioural change services and treatment, and how to personalise the NHS Health Check for individuals. A national marketing campaign would help to raise public awareness of the digital NHS Health Check and encourage people to engage with it.

Alongside this, NHS Digital, NHSX and OHID need to scope and set up improved systems for collecting, analysing and publishing data from the NHS Health Check so that monitoring, evaluation and quality improvement can all be made better.

OHID and local government should work with local NHS Health Check providers to continue to improve uptake and effectiveness of the service via sector-led improvement or other mechanisms, by developing different delivery models that use a range of providers and settings, and by using new performance metrics to guide local commissioning decisions.

Research should be commissioned to evaluate the practicality of adding mental and musculoskeletal health to the NHS Health Check, and of inviting younger people once the digital NHS Health Check is available. Work is also needed to understand the best way to ensure that people diagnosed with disease as a result of an NHS Health Check get the best available support elsewhere in the healthcare system, whether that is access to behaviour-change services or follow-on tests and medication.

5.3 The longer term

Full implementation of the recommendations for the new NHS Health Check could be achieved within 5 years, subject to investment.

Evaluation of the NHS Health Check should become routine so that it evolves into a learning system, incorporating new evidence as it emerges and ultimately achieving its goals of engaging people in maintaining good health and preventing disease, reducing health inequality, and acting as a gateway to the wider wellness ecosystem.

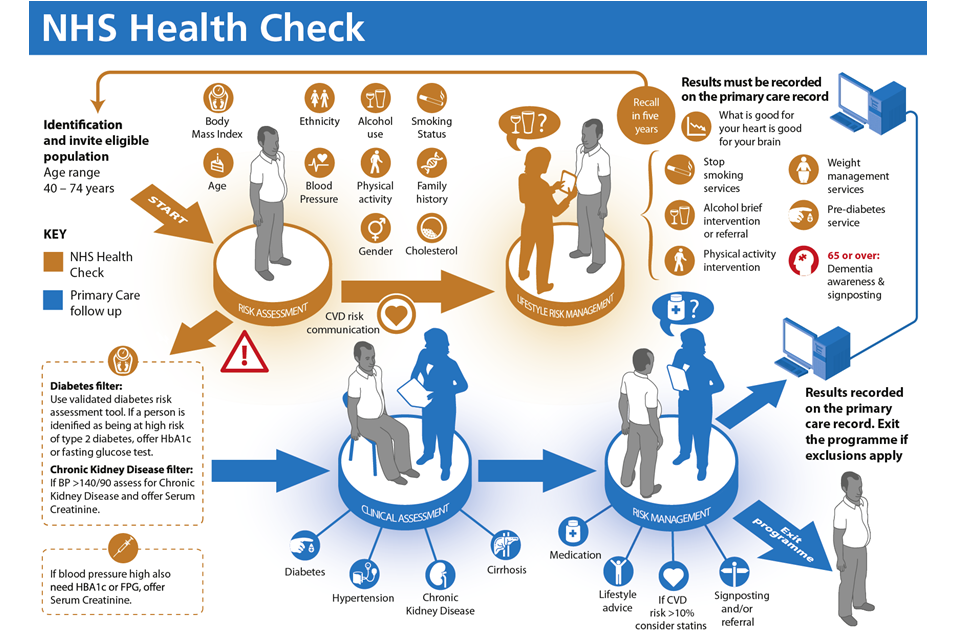

Appendix: NHS Health Check pathway

The NHS Health Check is a national prevention programme that aims to reduce the chance of a heart attack, stroke or developing certain forms of dementia in people aged 40 to 74. A check includes an assessment of:

- smoking status

- alcohol consumption

- physical activity

- weight

- blood pressure

- cholesterol

- diabetes risk

- 10-year cardiovascular disease risk

These results must be recorded on the person’s primary care record and communicated to them as part of the check. A person having a check should also be made aware that what is good for their heart is good for their brain. People between 65 and 74 years of age should be made aware of the signs and symptoms of dementia.

Individuals should be supported to manage risk factors and CVD risk where their results are abnormal. This can involve behaviour change support, brief intervention and referral to stop smoking, weight management, alcohol, diabetes prevention and physical activity services.

Individuals with assessment results that exceed clinical thresholds would be referred on for clinical assessment and diagnostic tests for diabetes, cirrhosis, kidney disease and hypertension in line with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance.

A detailed description of the NHS Health Check pathway is available in the NHS Health Check best practice guidance.

-

Office for National Statistics. ‘Mortality statistics – underlying cause, sex and age 2019‘ (accessed 11 June 2021) ↩

-

Public Health England. ‘NHS Health Check best practice guidance.’ 2019 (accessed 9 June 2021) ↩

-

Department of Health and Social Care. ‘The Local Authorities (Public Health Functions and Entry to Premises by Local Healthwatch Representatives) Regulations 2013’ (accessed 9 June 2021) ↩

-

Public Health England. ‘NHS Health Check delivery model survey 2021’ (accessed 9 June 2021) ↩

-

Department of Health and Social Care. ‘Advancing our health: prevention in the 2020s.’ 2019 (accessed 9 June 2021) ↩

-

Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. ‘Policy paper: The Grand Challenge missions.’ 2021 (accessed 13 September 2021) ↩

-

HM Government. ‘Building Back Better: Our Plan for Health and Social Care’ (accessed 13 September) ↩

-

Amanda M Perak, MD and others. ‘Associations of Late Adolescent or Young Adult Cardiovascular Health With Premature Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality.’ Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2020: volume 76, issue 23, pages 2,695 to 2,707 (accessed August 2021) ↩

-

National Health Service (NHS). ‘The NHS long term plan.’ 2019 (accessed 9 June 2021) ↩

-

Public Health England. ‘NHS Health Check programme review.’ 2020 (accessed 16 August 2021) ↩

-

Ference B, Yoo W, Alesh I, Mahajan N, Mirowska K, Mewada A and others. ‘Effect of Long-Term Exposure to Lower Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Beginning Early in Life on the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease: A Mendelian Randomization Analysis.’ ScienceDirect 2020: volume 60, issue 25 (accessed 10 June 2021) ↩

-

Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. ‘National Statistics: Local authority revenue expenditure and financing England: 2019 to 2020 individual local authority data – outturn.’ 2021 (accessed 10 June 2021) ↩

-

NHS Digital. ‘Digital inclusion for health and social care.’ 2019 (accessed 13 August 2021) ↩ ↩2

-

Office for National Statistics. ‘Internet access – households and individuals, Great Britain.’ 2018 (accessed 13 August 2021) ↩

-

O’Connor S and others. ‘Understanding factors affecting patient and public engagement and recruitment to digital health interventions: a systematic review of qualitative studies.’ BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 2016: volume 120, issue 16 (accessed 16 April 2021) ↩

-

Vassilakopoulou P and Hustad E. ‘Bridging Digital Divides: A Literature Review and Research Agenda for Information Systems Research.’ Information Systems Frontiers 2021 (accessed 13 August 2021) ↩

-

Public Health England. ‘Practice examples of international digital products for cardiovascular risk assessment and management.’ 2021 (accessed 13 August 2021) ↩ ↩2

-

Riley and others. ‘Evaluation of the heart age test: findings from test user data, an online survey and follow-up interviews.’ 2021 (accessed 13 August 2021) ↩ ↩2

-

Tanner L, Kenny RPW, Still M, Pearson F and Bhardwaj-Gosling F. ‘NHS Health Check Programme Rapid Review Update.’ University of Sunderland and Newcastle University 2020. (accessed 9 June 2021) ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Atkins L, Stefanidou C, Chadborn T, Thompson, T, Michie S, Lorencatto F. ‘Influences on NHS Health Check behaviours: a systematic review.’ BMC Public Health 2020: volume 20, page 1359 (accessed 9 June 2021) ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

Public Health England. ‘A rapid scoping review of community champion approaches for the pandemic response and recovery.’ 2021 ↩

-

Hobbs FDR, Jukema JW, Da Silva PM, McCormack T, Catapano AL. ‘Barriers to cardiovascular disease risk scoring and primary prevention in Europe.’ The International Journal of Medicine 2010: volume 103, issue 10, pages 727 to 739 (accessed 9 June 2021) ↩

-

Public Health England. ‘NHS Health Check programme: priorities for research.’ 2015 (accessed 13 September 2021) ↩

-

Robson, J and others. ‘NHS Health Checks: an observational study of equity and outcomes 2009 to 2017’. British Journal of General Practice 2021 (accessed 10 September 2021) ↩

-

Patel, R and others. ‘Evaluation of the uptake and delivery of the NHS Health Check programme in England, using primary care data from 9.5 million people: a cross-sectional study (PDF, 963KB).’ British Medical Journal Open 2020 (accessed 10 September 2021) ↩

-

Chang K, CM and others. ‘Coverage of a national cardiovascular risk assessment and management programme (NHS Health Check): Retrospective database study.’ Preventative Medicine 2015 (accessed 10 September 2021) ↩

-

Robson J and others. ‘The NHS Health Check in England: an evaluation of the first 4 years.’ British Medical Journal Open 2016 (accessed 10 September 2021) ↩

-

Public Health Group Foundation. ‘Polygenic scores, risk and cardiovascular disease.’ 2019 ↩

-

Reinikainen, J and others. ‘Lifetime cumulative risk factors predict cardiovascular disease mortality in a 50-year follow-up study in Finland.’ International Journal of Epidemiology 2015: volume 44, issue 1, pages 108 to 116 (accessed 13 August 2021) ↩

-

Department of Health. ‘Putting prevention first: Vascular checks risk assessment and management – impact assessment (PDF, 607KB).’ 2008 (accessed 16 February 2021) ↩