Open Policy workshop

Published 3 April 2019

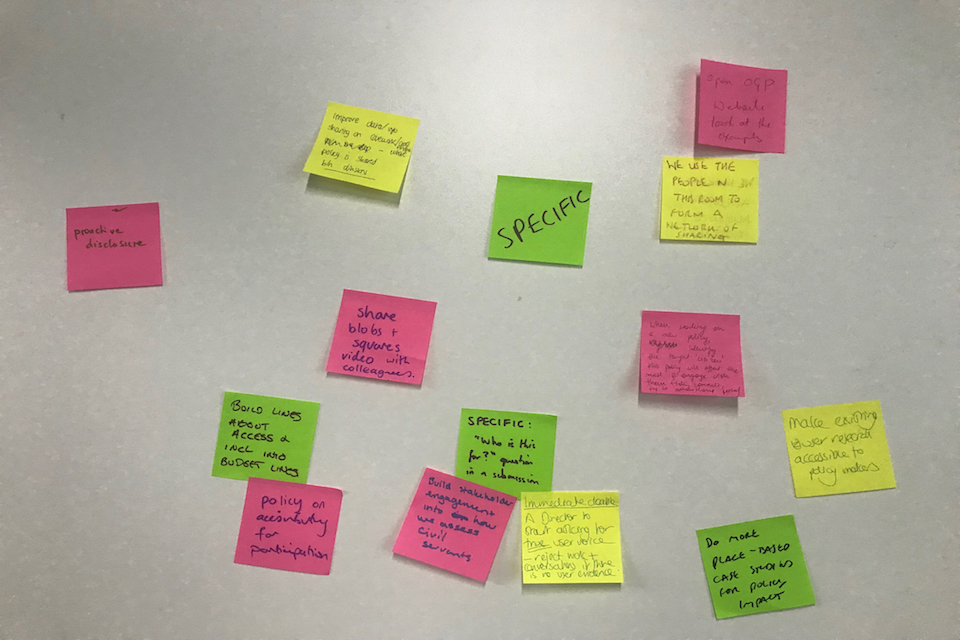

Open policy workshop postits

At PolicyLab and DCMS, we believe that governments work better when all voices are included and more diverse ideas lead to innovative solutions. When policies respond directly to the needs of the people, citizens trust in governments increases. This makes open policymaking one of the most effective means of civic participation.

Open Policy Making (OPM) results in a more informed and better designed policies for both, the government and the people who use, or are impacted by, services. Open policymakers design around the human experience, enable co-design supported by evidence and test policies as they develop them. A core element of OPM is ensuring that evidence is used in a transparent and open manner. This enables policymakers to gain a common understanding of people’s needs. For civil society, it provides an evidence base that has informed decision making. It also provides opportunity to see if there are gaps in the knowledge base and where further research might be commissioned.

Open policymaking workshop

With a small but dedicated group of policymakers from DWP, MHCLG, DCMS, Greater Manchester Authority, Scottish Government, civil society member from Involve and Demsoc, and researchers from the University of Manchester, we conducted a one-day workshop in Manchester to explore different dimensions of open policy and develop a set of actions we could start using at different stages of the policymaking process.

As stressed by the participatory policymaking veteran Doreen Grove, Head of Open Government at the Scottish Government, the key is to perceive people not as a problem but as an asset and look at how to involve them in decision making. She stressed that this conversation needs to happen very early in the process, and luckily, technology and data facilitate collaboration and sharing all sorts of information with the public. As Doreen noticed, policymakers tend to be reluctant to go outside and listen to the people on the streets. What needs to happen is participation that produced real outcomes, the voices of the people need to be heard and listened.

To ensure that this voice is heard and considered during the policymaking process, there is a need for greater connections between governments and civil society organisations, and for the government to become more approachable and ‘human’, as pointed out by Michelle Brook from Demsoc. She also recommended that for participation to be truly representative, the government needs to reach out to the most vulnerable or not responsive citizens and engage them in the process, perhaps through building networks of organisations able to reach out to specific communities. Finally, the civil society actors need to know what is the value added for them when participating in open policy process. They should be informed on how participating in the consultations will benefit them and how exactly their input will be used. This clarity and transparency embedded in the open policy process is instrumental to building trust in governments.

To understand how participation works in practice, we discussed a worked example of an open policy process, in relation to the development of Part V of the Digital Economy Act. The ‘OPM’ process was co-ordinated by the not-for-profit organisation Involve, and brought Civil Society groups, academia and other interested parties together with government in open dialogue about the proposals for new data sharing proposals. We reflected on the process and acknowledged that some areas could have been improved, such as the amount of representation in the sessions, and the feedback mechanisms for participants, but also that the endeavour marked a positive move for government to actively engage and seek the views of external expertise in the decision making process.

Following an open discussion on what works and what we still need to develop, we collectively identified a set of challenges that we have encountered when trying to design policies in a more open manner:

-

Lack of information sharing within and between departments in terms of the policy areas they work on

-

Sharing information in a way that is useful for others without breaching privacy laws, mitigating concerns

-

How to stimulate culture change towards open policymaking in the light of competing priorities?

-

What is the appropriate relationship between the civil society and government

-

How to get a permission to do open policy?

-

How to evaluate participatory policy projects? How to react when organisations say that the process didn’t work out?

What do we need to do to enable open policymaking?

During the discussion, we came up with a number of high-level actions that could support more open policymaking.

To enable open policymaking, we need to:

-

Move away from the policymaking jargon to increase accessibility

-

Be honest and open externally and internally, this includes telling senior officials what they should hear, rather than what they want to hear

-

Become smart commissioners - understand what skills are needed to commission the work properly, e.g. specialist skills for data collection and analysis

-

Use links to other countries and share learnings internationally

-

Proactively publish information instead of finding new ways to hide it; public servants need to recognise that information they produce should be open and available

-

Work in the ‘national framework, local delivery’ approach that acknowledges the local differences and enables more flexible, better-targeted implementation

If you are a policymaker willing to engage in a more open policy making practice, this is a set of specific, immediate actions we developed during the workshop:

-

Create more place-based policy case studies and proactively use the case studies that already exist, e.g. OGP examples, improve data information sharing on case work across divisions and make existing user research available to policymakers

-

Incorporate ‘who is this for’ question in every policy/ministerial submission, identify the target ‘citizen’ this policy will affect

-

Share the blobs and squares video with colleagues

-

Build budget lines around accessibility and inclusion for every project and justify it in case of any push-backs Properly commission experts to run and facilitate events that are aimed to stimulate dialogue and focus on accessibility for participation

-

Build stakeholder engagement into how we assess civil servants

We also developed a set of long-term goals:

-

Set up secondments into civil society organisations for the government officials

-

Focus more attention on local government

-

Involve people in making crucial decisions

-

Recruit for a truly representative, diverse government

As summed up by Vasant Chari from the PolicyLab, government systems are difficult to break into and small changes are the best way forward. We need to celebrate small victories and open up the policymaking process step by step. In the words of Doreen Grove, ‘none of this is easy but if we don’t try, we will never change’.

This is an open discussion led by DCMS and our civil society partners, not an official statement of policy.