Origins and Evolution of the CASLO Approach in England - Chapter 5: CASLO goals

Published 18 November 2024

Applies to England

Now is a good time to reflect on motivations for adopting the CASLO approach as a high-level design template for qualifications as distinct as NVQs and BTECs, let alone as the design template for all QCF qualifications, or even all qualifications, per se (as both Jessup and the FEU appeared to propose). These motivations – the goals that explain why the CASLO approach was adopted in the first place – were not always clear. This is partly because the purposes for which these qualifications were designed were articulated differently by different commentators. But it is also because the motivations that drove adoption of the CASLO approach would have been a subset of the broader profile of purposes proposed for the qualification in question (and were not always clearly distinguished).

Because they determine the design of the qualification model itself, CASLO-specific goals would have been extremely fundamental. Yet, perhaps for exactly that reason, the need to articulate them explicitly may not always have been apparent. Whatever the explanation might be, it seems that the goals that drove adoption of the CASLO approach often remained more implicit than explicit. The following analysis is an attempt to explicate them, which has involved an element of retrospective reconstruction based upon the documentary analysis that underpinned this project.

Before explicating these CASLO-specific goals, it is important to distinguish them from goals that were relevant to, but not necessarily premised upon, the CASLO approach. For instance, one of the purposes underpinning the NVQ framework was to provide qualifications that were based on employment-led standards of competence (NCVQ, 1987). This resonated with the ‘new vocationalism’ of the 1970s and 1980s, which emphasised the importance of occupational, in contrast to liberal, objectives. Whereas, previously, attempts had been made to integrate liberal studies within TVET qualifications, NVQs effectively displaced them. While it seems legitimate to argue that this was one of the intended purposes of the NVQ framework, it is harder to argue that this was a motivation for adopting the CASLO approach, per se. This is because the spirit of new vocationalism could equally have been operationalised using a quite different approach, even the classical approach.

Note that this spirit of new vocationalism would have been underpinned by even more fundamental sociopolitical goals, such as increasing productivity and international economic competitiveness. These clearly help to explain the perceived need to reform the TVET qualification landscape. But do they explain why reformers turned to outcome-based qualification design, or to the CASLO approach more specifically? Probably not. We need more proximal explanations.

Steve Williams and Peter Raggatt have documented a variety of higher-level sociopolitical goals – goals that are linked to the introduction of competence-based qualifications without necessarily being directly linked to the introduction of the CASLO approach (Williams & Raggatt, 1996; Williams & Raggatt, 1998; Williams, 1999; Raggatt & Williams, 1999; see also Bates, 1995; Butterfield, 1996). Having said that, some commentators have argued that certain sociopolitical goals were not simply linked to, but specifically relied upon, adopting an outcome-based approach. Indeed, certain sociologists have argued that goals of this sort were paramount in explaining the introduction of outcome-based qualifications. For example:

By defining qualifications in terms of written outcomes alone, an attempt was made to shift the balance of power away from provider-defined qualifications and curricula (which in many instances incorporated professional associations in various ways) towards a broader group of users – government, employers, and learners.

(Young & Allais, 2009, page 8)

We suggest that the emergence of outcomes-based qualifications has been linked to the marketization of education. […] Learning outcomes or competency statements have come to prominence as a policy tool in this context. They have been seen by policy formulators as a way of driving the required change by playing the role of performance statements in contractual arrangements for educational provision.

(Young & Allais, 2011, pages 2 to 3)

In the first instance, Young and Allais were developing a line of reasoning from Young (2008), which claimed that outcome-based qualifications – based upon employer-driven standards – were introduced because of their potential to help overthrow the educational establishment, constituting: “a completely new approach to vocational education in which (at least in theory) outcomes replaced the curriculum, and workplace assessors replaced teachers” (Young, 2008, page 140). The clarity and transparency provided by learning outcomes and associated assessment criteria was deemed to be critical for empowering those who would assume the roles traditionally played by college teachers.

In the second instance, Young and Allais appeared to be developing a slightly different line of reasoning related to the ability to hold training providers to account. Once again, the idea was that this should help to open training up to new providers who would be held accountable, and compete with each other in a new training market, on the basis of successful delivery of state-endorsed qualifications.

There is certainly some truth in both of these suggestions. We saw how traditional off-the-job college courses were criticised for focusing too much on ‘book knowledge’ and not enough on the ability to perform an occupational role. We also saw how the lack of certification for on-the-job competence was linked to highly variable training provision. NVQs, with their emphasis on workplace learning and assessment, were intended to help redress this balance. Moreover, it was true that ministers were keen to hold education and training providers to account on the basis of assessment and qualification results during the 1980s, and it was assumed that greater use of criterion-referencing might help to promote this. In theory, the more clearly we can define what students are supposed to have learnt during a period of schooling, the more straightforward it will be to hold teachers and trainers to account for whether or not students actually acquire those learning outcomes.

Goals of this sort were clearly important, although whether they were paramount in explaining the introduction of outcome-based qualifications is open to debate.[footnote 1] To reach a conclusion of this sort, we would need to consider the full range of goals that outcome-based qualifications – and the CASLO approach more specifically – were introduced in order to achieve. Therefore, alongside sociopolitical goals, we would need to consider certification and educational goals too.

These 3 categories represent distinct perspectives from which qualification goals can be viewed. The distinction between certification goals and educational ones turns on whether the intention is to improve assessment (certification goals) or to improve learning (educational goals). In the first instance, the intention is to improve the quality of information provided by the certification process, concerning the attainment of each certificated learner. This is often known as improving qualification validity. In the second instance, the intention is to improve the quality of teaching, or the quality of learning, or to increase uptake, or to improve completion rates. These are often described as intended ‘backwash’ impacts from qualification design decisions.[footnote 2]

It is clear that, prior to the introduction of outcome-based qualifications, there were longstanding concerns over the validity of existing qualifications – not just TVET ones, but general ones too. In 1943, the Norwood report argued for greater reliance upon teacher assessment, to facilitate a more comprehensive certification process, one that was capable of painting a broader picture of attainment than was possible with external exams. In 1969, the Haslegrave report argued essentially the same point, insisting that traditional external exams failed to test the high-level competencies that technicians needed to acquire, and recommending that more authentic centre-based assessments be adopted instead.

The decision to base TEC and BEC awards upon an outcome-based approach can be seen as a direct response to these concerns, following a logic that had been spelt out decades earlier by Tyler and other pioneers of the Objectives Movement. The outcome-based approach was intended to improve both the comprehensiveness and the authenticity of TVET qualifications – both critical aspects of validity – for TEC awards, BEC awards, and NVQs too.

Following the logic set out by Tyler, outcome-based qualifications were also intended to have positive impacts on teaching and learning. This takes us from certification goals to educational ones. Given their importance in explaining the adoption of the CASLO approach in England, we will explore these educational goals in far more detail below.

Educational goals

Adoption of the CASLO approach in England appears to have been driven by multiple educational goals, which have influenced different qualifications and qualification frameworks in different ways and to differing degrees. The following 4 goals appear to have been particularly important. They relate to improving:

- domain alignment – to align curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment as closely as possible with the intended domain of learning (and therefore also with each other)

- domain mastery – to ensure that all students achieve a satisfactory level of attainment across the full domain of learning

- qualification efficiency – to make the process of becoming qualified as efficient as possible

- domain personalisation – to enable the domain of learning to be tailored to the personal situation, interests, or needs of learners (or customised to meet the needs of local employers)

These are simply goals, of course, and will not always have been achieved for any particular CASLO qualification or framework. The idea is simply that characteristics of the CASLO approach helped to establish a mechanism by which each of these goals could be achieved. Remember that the 3 core characteristics were defined as follows:

- the domain of learning is specified as a comprehensive set of learning outcomes

- a standard is specified for each learning outcome, via a set of assessment criteria, and these criteria are used to judge student performances directly

- a pass indicates that a student has acquired the full set of learning outcomes specified for the domain

It is important to note that the 4 goals are not achieved through identical mechanisms, which means that they do not attach exactly the same weight to each of the 3 core characteristics. For instance, the first characteristic is particularly relevant to achieving the first goal. This is because close alignment to the target domain requires it to have been specified in full. CASLO qualifications attempt to achieve this via a comprehensive set of learning outcomes, which becomes the single point of reference to which curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment plans can all be aligned.

Of course, even assuming that this facilitates close alignment, we should not assume that learners will naturally end up mastering the domain of learning in full. This would represent a quite different goal, which would require its own mechanism. Of particular relevance to achieving the second goal, domain mastery, is the third characteristic: the stipulation that a qualification will not be awarded unless a student has achieved the full set of learning outcomes.

Although different goals depend on different mechanisms, it is worth noting that one particular mechanism – transparency – is important to achieving all of them. The first and second characteristics, which require learning outcomes and assessment criteria to be articulated, both help to ensure transparency by specifying unit content and standards in detail. So, too, does the mastery requirement, as it makes clear that a qualified individual will have achieved all of the specified learning outcomes.[footnote 3]

Before considering how specific CASLO qualifications may have been designed with particular educational goals in mind, we will explain what we mean by each of the 4 goals in a greater detail.

Domain alignment

The domain alignment goal can be traced back to the Objectives Movement, which was pioneered by scholars including Tyler, Bloom, Mager, and others. It seeks to ensure that curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment are aligned as closely as possible with the target domain of learning (and therefore with each other). Misalignment is a classic educational problem, which has been recognised for well over a century, and continues to be a major concern internationally to the present day (see, for example, Porter, et al, 2007; Webb, 2007).

The argument for adopting an outcome-based approach to qualification design is that, without a clear and complete specification of a domain of learning, participants in the education-certification process – including teachers, trainers, learners, and assessors – are liable to reach different conclusions concerning exactly what needs to be taught, learnt, and assessed. The idea of a ‘target’ domain suggests that this process needs to be based upon a single, agreed specification of what the qualification is intended to certify and, by implication, what it is not intended to certify. This specification literally becomes the target at which teachers and students aim, and that directs the attention of qualification designers, developers, users, and evaluators alike.

At the heart of the outcome-based approach – and the CASLO approach more specifically – is the idea of specifying the target domain for a qualification as the set of valued learning outcomes that collectively comprises it. The payoff from clear and complete specification is intended to be twofold.

First, it helps to ensure that each qualification targets exactly the right domain of learning. Alternative approaches, including the classical approach, do not specify the intended domain of learning with anything like the same degree of precision. This means that the full scope of the domain may never even be fully debated, let alone agreed.

Second, and more pragmatically, clear and complete specification provides the basis for consistent interpretation. This helps to ensure that the domain of learning is interpreted consistently from one teacher to the next, from one assessor to the next, from one student to the next, from one employer to the next, and so on. It helps to ensure that those in charge of the curriculum interpret the domain of learning in exactly the same way as those in charge of pedagogy and assessment.

If both of these aims are realised, then this paves the way for the target domain to be taught, learnt, and assessed as authentically and comprehensively as possible. This is why domain alignment is simultaneously a certification goal (to improve the quality of assessment) and an educational one (to improve the effectiveness of teaching and learning).[footnote 4]

Domain mastery

The domain mastery goal can be traced back to the Mastery Movement, which was pioneered by scholars including Bloom, Carroll, Gagne, and others. It seeks to ensure that all students achieve a satisfactory level of attainment across the full domain of learning.

Domain mastery follows naturally from domain alignment. Having specified the set of valued learning outcomes that collectively comprises a domain of learning, why would we not want all learners to achieve all of them? The CASLO approach involves both a ‘stick’ and a ‘carrot’. The threat of withholding certification constitutes the motivational ‘stick’ whereas the design of the qualification structure – which helps students and teachers to monitor progress towards completion, with frequent positive reinforcement along the way – constitutes the motivational ‘carrot’.

The domain mastery goal holds particular significance for motivating slower learners, who might already have experienced failure on classically designed qualifications, and for whom mastery learning has the potential to be rehabilitative. It also holds particular significance for learners studying occupational qualifications, which are intended to certify full occupational competence. Importantly, though, the domain mastery goal is potentially relevant to any learner in any situation.

Adopting the CASLO approach to achieve this goal means designing a qualification consistent with the expectation that any student who works hard enough ought to be able to acquire all of the specified learning outcomes, to a satisfactory standard, given adequate time and support (and assuming that they began the course from an adequate baseline of knowledge, skill and understanding). It also means assessing each of the specified learning outcomes independently, to be able to confirm when mastery has been achieved. This contrasts with the classical approach to qualification design, which implicitly assumes that only high-achieving students will master the domain of learning in full, and that requires only a relatively small sample of learning outcomes to be assessed. In-course formative assessment is an important requirement for successful mastery learning.

It is sometimes assumed that domain mastery is nothing more than a basic presumption of any occupational qualification. In other words, it is simply of the nature of an occupational qualification that it certifies competence across the full domain of learning. After all, we expect pilots to be able to take off, and land, and do everything flight-related in between. The idea that excellent taking off might somehow compensate for sub-optimal landing does not wash.

It is fair to say that full competence – across each and every specified learning outcome – would be a necessary prerequisite for successfully performing certain occupational roles, although not necessarily all. However, this is much less likely to be true for vocational qualifications taken by school and college students. More to the point, prior to the adoption of the CASLO approach in England, even occupational qualifications were not mastery-based. As such, domain mastery is best understood, primarily, as an educational goal relevant to any qualification context, but of particular significance to certain learners in certain situations.

Qualification efficiency

The qualification efficiency goal is about making the process of becoming qualified as efficient as possible. It applies to the design of qualification frameworks as well as to the design of individual qualifications. Transparency is a critical enabling mechanism, which the CASLO approach achieves by specifying qualification units in terms of both learning outcomes and assessment criteria. Efficiency, in this context, is primarily about avoiding unnecessary duplication of learning and assessment, thereby making qualifications more accessible. It is often discussed in terms of building flexibility into qualifications.

Efficiency is most obviously manifested through qualification systems that accommodate the Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL), which is also known by other names, including the Accreditation of Prior Learning (APL). Specifying qualification units in terms of learning outcomes and assessment criteria enables a learner to determine where they might already have satisfied certain of the requirements for a particular qualification through prior learning. If that prior learning has already been certificated at a sufficiently granular level – which can happen when students pull out of courses having completed some but not all units – their previous achievements can be recognised towards completion of a new qualification. Systems of this sort are particularly useful for individuals who return to learning after a short period of absence, or who move from one location to another and need to transfer from one education or training provider to another. RPL can also be very efficient for those who have not followed a formal course of learning, but who may have acquired competence in situ. Being able to have that informally-acquired competence certificated – against clearly articulated standards – avoids the need to undertake a formal course of education or training unnecessarily (merely for certification).

Efficiency is also a feature of what has become known as Roll-On-Roll-Off (RORO) delivery, which offers candidates the opportunity to begin and complete a qualification at various points throughout the year rather than being restricted to a single point of enrolment and completion. The CASLO approach facilitates this in essentially the same way as for RPL, by tracking the acquisition of learning outcomes (and the completion of units) systematically, synchronously, and transparently.

Efficiency can also be manifested through qualification frameworks that accommodate common units. Specifying units in terms of learning outcomes and assessment criteria enables the determination of identical demands across different qualifications. Units of this sort can be designated as common (to a specified set of qualifications) within the framework. Frameworks of this sort are particularly useful for learners who chose to switch to a different (albeit related) qualification part way through a course of learning. Rather than having to start again from scratch, any common units will count the same in the new qualification as in the old one. This is sometimes known as Credit Accumulation and Transfer, although it is a strict version of CAT, which depends on exactly the same set of learning outcomes having been specified across qualifications or providers. We might refer to this as a CAT-IA system, as the credits that are transferred relate to Identical Achievements. By making an effort to design common units into qualifications wherever viable, qualification frameworks can be ‘rationalised’ to avoid unnecessary duplication.

A final manifestation of qualification efficiency, which might be facilitated by adopting the CASLO approach, concerns the potential for recognising progression opportunities. The level of detail provided by learning outcomes and assessment criteria might enable anyone responsible for, say, careers guidance to map plausible progression routes through qualifications with a level of precision that might not be possible if only syllabus content were available for scrutiny.

Domain personalisation

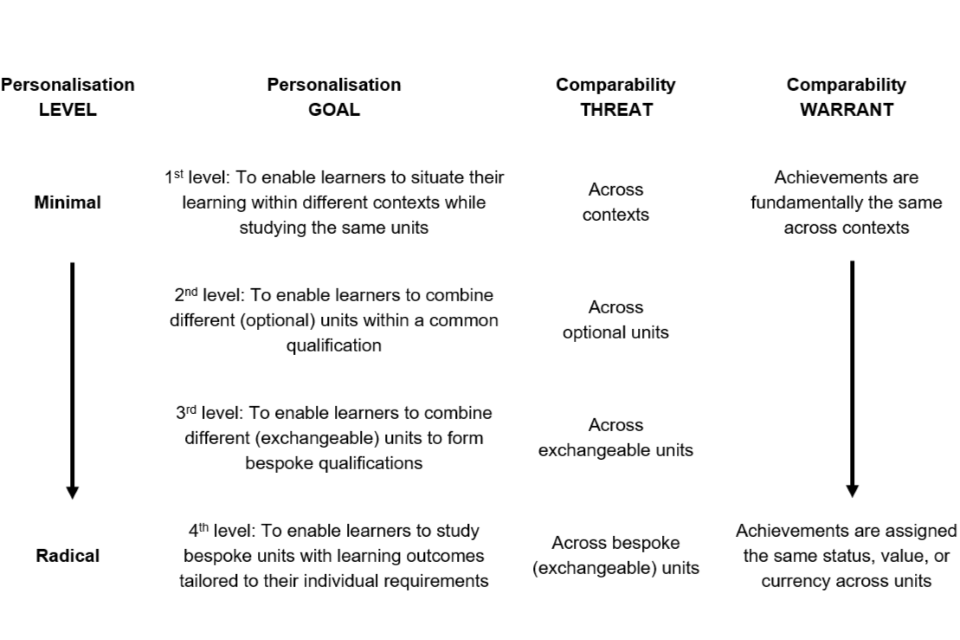

The goal of domain personalisation is to tailor a domain of learning – as set out in the specification for a unit or qualification – to the personal situation, interests, or needs of learners (or to customise it to the needs of local employers). This is often described as an aspect of qualification flexibility. Figure 16 illustrates qualitatively different levels of personalisation. The idea here is that the potential for studying an increasingly bespoke programme of learning increases with each level of analysis.

At the first level, we can imagine the situation for learners who are studying a qualification that comprises only mandatory units, meaning that they all have to achieve exactly the same set of learning outcomes. In this situation, the potential for personalisation would only arise if the learning outcomes were written with sufficient generality to apply across multiple contexts of learning, such that one student might demonstrate them in one context while another might demonstrate them in another.

At the second level, we can imagine a similar situation, but this time with half of the units being optional rather than mandatory. Being able to choose from a variety of optional units means that students are now able to follow somewhat different routes through the same qualification (beyond the common mandatory units).

The third level is intended to reflect the situation in which learners are offered even more potential for customising their programme of learning. This is consistent with the idea of a framework, like the QCF, which offers students the potential to mix and match accredited units to form bespoke qualifications (albeit typically within the parameters of prespecified combination rules).

Figure 16. Different levels of personalisation

Levels of personalisation, from first to fourth, are associated with different goals, comparability threats, and comparability warrants.

Finally, the idea of personalisation is taken to an extreme at the fourth level, where unit personalisation becomes possible. This is consistent with the idea of a learner negotiating an entirely bespoke programme of learning, such that even the learning outcomes that comprise each of the units they study can be tailored to their personal situation, interests, or needs.

Figure 16 is intended to be illustrative rather than definitive. For instance, it might be possible to identify mezzanine levels. Alternatively, certain qualifications or frameworks might introduce situations that do not fit neatly into any particular level. Also, it is important to recognise that the levels are not independent of each other, in the sense that units at any level might, for example, incorporate the kind of flexibility illustrated at the first level (although they might not).

The following 2 subsections draw a pragmatic distinction between minimal and radical domain personalisation, linked to the 4 levels from Figure 16. In addition to providing additional exemplification, they explain the significance of the CASLO approach to domain personalisation, including why the first level differs from the remaining ones in this respect.

Minimal domain personalisation

The first level of domain personalisation is the least radical. It corresponds to the situation in which all students within a qualification cohort are expected to acquire exactly the same set of learning outcomes for each unit. The flexibility that is permitted – at this minimal level of personalisation – depends on how tightly the learning outcomes for each unit are circumscribed.

Imagine, for example, that we wanted to design a management qualification to certify the fundamental competencies that managers of small and medium enterprises typically require. Although it might well be possible to reach consensus over a common set of learning outcomes – that might be just as relevant in a small supermarket as in an accountancy firm – it is also quite possible that the expression of those learning outcomes might look quite different across contexts, perhaps even requiring additional ancillary background competencies. An outcome-based approach to qualification design could accommodate a situation like this, as long as the contexts were similar enough for the single set of learning outcomes to have the same significance across contexts, and for the assessment criteria to be equally applicable.

Whenever an element of personalisation is permitted within a qualification, this raises a comparability threat: the greater the degree of personalisation, the greater the threat. In the example just discussed, the issue is whether the different contexts (supermarket versus accountancy firm) are sufficiently similar to be accommodated within a single (management) qualification. This issue has both a logical aspect to it and an empirical one. From a logical perspective, it would need to be the case that learners really were able to achieve the same outcomes, and to demonstrate the same performance standards, across contexts. Establishing this requirement is an important aspect of qualification design, prior to the qualification going live, which is likely to include debate and consensus building between stakeholders. From an empirical perspective, it would also need to be the case that performance standards were applied, in practice, with the same level of stringency across contexts. This is an aspect of qualification delivery rather than qualification design.

To provide a slightly different example, it might well be possible to construct a set of learning outcomes and assessment criteria – for a particular domain of learning – that had essentially the same significance and applicability for learners who were learning in a college setting as for those who were learning in a workplace setting. The better the college was at simulating a working environment, and the better the workplace was at supporting the acquisition of underpinning knowledge and understanding, the stronger this claim might be. The contexts of acquisition (learning) and demonstration (assessment) would differ, of course, but not necessarily by enough to undermine the claim that students were able to acquire the same outcomes to the same standards.

Although the CASLO approach has the potential to support a minimal level of domain personalisation along these lines, it does not presume it, and can straightforwardly reduce or eliminate it. For instance, outcomes and criteria might be written in a manner that tightly circumscribed the contexts of acquisition and demonstration.[footnote 5] Or these contexts might be circumscribed separately, for example, via range statements. Or they might be circumscribed by other qualification design decisions, for example, by controlling assessment tasks more tightly.

By way of summary, the CASLO approach is often associated with the potential for (minimal) domain personalisation because of how explicitly it articulates learning outcomes. Just as detailed specification clarifies exactly what outcomes need to be learnt, it also helps to clarify the degree of flexibility that might be available concerning the contexts within which those outcomes might legitimately be situated, potentially enabling the same outcomes to be acquired and demonstrated in somewhat different contexts. In other words, the transparency of the CASLO approach reveals the potential that exists (or does not exist) for minimal domain personalisation of this sort. This potential can be dialled up or down depending on how tightly the learning outcomes and assessment criteria are circumscribed.

The second level of domain personalisation from Figure 16 is slightly different. It corresponds to the situation in which all students within a qualification cohort study exactly the same mandatory units, but are able to select a certain number of units from a variety of available optional ones. For example, a business qualification might have 4 mandatory units, plus a choice of 2 from the following 4 units: business accounting, financial accounting, management accounting, accounting systems. In this instance, the learning outcomes and assessment criteria would differ across the 4 optional units. Consequently, to justify the provision of optional routes within this qualification, there would need to be an expectation of a reasonable level of comparability of overall demand across the optional units.

Once again, the CASLO approach helps to support this goal via the mechanism of transparency, albeit in a slightly different way. At this level, the detailed specification of outcomes and criteria helps to clarify upfront – at the qualification design stage – the nature, breadth, and depth of the required learning within each of the optional units. If the outcomes within each unit appear to be sufficiently similar in terms of the nature and amount of their content, and if the criteria linked to those outcomes appear to be sufficiently similar in terms of the demands that they make of learners, then this provides a warrant for claiming that the optional units are sufficiently comparable. This is no more than a rough judgement of comparability, of course, based on appearance alone (with no reference to empirical data on how demanding the units actually prove to be in practice). But it is a critical part of the comparability warrant all the same. Incidentally, the transparency provided by the CASLO approach also means that the comparability claim is open to challenge.

Radical domain personalisation

The third level of domain personalisation is more radical than the second because it extends the idea of using (optional) units to construct different routes through a qualification into the idea of using (exchangeable) units to form bespoke qualifications. It corresponds to the situation in which learners are able to mix and match units that have been accredited to a particular location in a qualification framework, guided by rules that specify what sort of units can be combined to form what kind of qualification. As noted above, the QCF provides an example of this approach to domain personalisation.

At this level, the exchangeable units are likely to be less similar in terms of the nature of their learning outcomes. So, the comparability claim that needs to be warranted will be correspondingly looser. Once again, though, it is the detailed specification of outcomes and criteria that helps to clarify upfront – at the unit design stage – the nature (content), breadth (size) and depth (complexity) of the required learning within each unit. This becomes the basis for the judgement that underpins the accreditation of the unit to a particular location in the qualification framework (characterised in terms of sector area and level, for instance).

This radical domain personalisation goal requires a mechanism for assigning equivalent status, value, or currency to units that certify exchangeable (but not equivalent) achievements. The idea of equivalent status suggests that 2 qualifications might share the same currency in the job market, despite comprising different units and certifying different competencies. According to the logic of this goal, a qualification does not necessarily have to earn its currency over a period of time – by winning the confidence and understanding of stakeholders – if, instead, its currency can be guaranteed upfront by the location that its units occupy within a regulated qualification framework.[footnote 6] For instance, university degrees made up of different modules are commonly accepted as having equivalent status in this sense, where the modules are judged by the university to be (roughly) comparable.

Specifying a common approach to qualification design – particularly a transparent one like the CASLO approach – will help the framework owner to accredit each unit to an appropriate location in the framework. This will be done on the basis of judgements of comparable demand, related to unit content, size and complexity. Occupying a particular location in the framework indicates that a unit has equivalent status, value, or currency to other similarly located units. From this perspective, transparency is the tool that facilitates judgements concerning comparable demand, which provide the justification for claims concerning equivalent value.

The fourth level of domain personalisation is the most radical. It corresponds to the situation in which the content of a unit is tailored to the requirements of an individual learner. This extends the idea of mixing and matching standard units from a central unit bank to the idea developing bespoke units, for individual learners, which can then be assigned currency by accreditation to a location in a qualification framework. Once again, the CASLO approach helps to support this accreditation process by facilitating judgements of (rough) comparability.

These radical personalisation goals are associated with the development of the Credit Movement in England, and with permissive versions of Credit Accumulation and Transfer, which permit non-equivalent achievements to be treated as though they are exchangeable across qualifications or providers. We might refer to this as a CAT-EX system, as the credits that are transferred relate to Exchangeable Achievements (not identical ones). A similar logic underpins the use of an Exemption policy, where entry requirements can be satisfied by a range of exchangeable units, or qualifications, some of which will be more directly relevant to the progression route than others.

Significance of the CASLO approach

It is worth revisiting the significance of the CASLO approach at this point, partly to explain differences between the levels in Figure 16, but also partly to consider alternative dimensions of personalisation and whether they ought also to be described as distinct CASLO goals in their own right. Bear in mind that, by describing something as a CASLO goal, we are suggesting that it counts as a reason why a qualification designer might have opted for (the features that comprise) the CASLO approach as opposed to (the features that comprise) a different approach to qualification design.[footnote 7]

In the case of first level domain personalisation, we might decide to adopt the CASLO approach because the specificity of its outcomes and criteria not only explicate exactly what needs to be learnt, they also explicate the potential for situating that learning in different contexts. Again, for some CASLO qualifications, there may be no such potential, depending on how tightly the outcomes and criteria are specified. Yet, for other CASLO qualifications – where cross-context domain personalisation is an explicit goal – outcomes and criteria will be written specifically to facilitate this.

Although first level domain personalisation raises a threat to comparability, the desire to establish comparability is not the rationale for adopting the CASLO approach. It is, however, the rationale for adopting the CASLO approach for the remaining 3 levels. In each case, the introduction of optional, exchangeable, or bespoke units raises the question of whether these non-equivalent units are sufficiently comparable. If they are not sufficiently comparable, then the qualifications that they result in will also not be comparable, which presents a threat to their currency in the job market. The CASLO approach can help to address this threat by specifying the nature (content), breadth (size) and depth (complexity) of each unit in as much detail as possible. This maximises the potential for reaching defensible conclusions concerning the comparability of non-equivalent units upfront (even before the units have gone live) on the basis of logical analysis alone.[footnote 8]

Moving on to alternative dimensions of personalisation, it is sometimes suggested that the following ought also to be described as plausible reasons for wanting to adopt the CASLO approach:

- teaching and learning approach personalisation – which is the flexibility that arises when the acquisition of learning outcomes is compatible with a variety of approaches to teaching and learning (that is, the same outcomes can be taught and learnt in different ways, for example, via didactic instruction or via problem-based inquiry)

- assessment format personalisation – which is the flexibility that arises when the demonstration of the acquisition of learning outcomes is compatible with a variety of approaches to assessment (that is, the same outcomes can be assessed in different ways, for example, via written testing or via oral questioning)

It is true that these are sometimes described as benefits from adopting the CASLO approach. But, should we classify them as CASLO goals in their own right, that is, as substantive reasons for wanting to adopt the CASLO approach (as opposed to a different approach to qualification design)? Or are they better classified simply as fringe benefits from adopting the approach?

It is not obvious, for instance, why the detailed specification of outcomes and criteria – characteristic of the CASLO approach – might make it significantly easier for a teacher to adapt their approach to teaching a particular qualification (compared with a classical qualification that is specified in far less detail). Note that General Qualification examining boards have traditionally shied away from pedagogical prescription, assuming that teachers ought to be free to choose how they teach.[footnote 9]

Nor is it obvious why continuous centre-based assessment within a CASLO qualification might be inherently more amendable to assessment format personalisation than continuous centre-based assessment within a classical one. In the CASLO qualification context, assessment format personalisation is often seen as particularly valuable for learners who find responding in a particular format very challenging. For example, a learner might struggle to write a convincing response to a constructed-response exam question, yet they might respond far more convincingly in the context of a professional discussion. Furthermore, in certain CASLO qualification contexts, if a learner fails to perform successfully in one format, then this might be directly followed up by assessment in a different format, to see if they are able to perform better.[footnote 10] Yet, whether this is simply a highly valued mitigation within an approach that implements the mastery principle so rigidly, or whether it is a substantive goal in its own right, is open to debate.[footnote 11]

Finally, on a slightly different note, it is worth mentioning that the domain personalisation goal can be construed from multiple perspectives. For instance, we have chosen to describe it from a personal perspective, in terms of the benefit that accrues to learners from being able to tailor a domain of learning to their individual situation, interests, or needs (or to the needs of local employers). However, it could also be described from an administrative perspective, in terms of the benefit that accrues to providers from being able to accommodate a wide range of learning needs within a single course structure. This might be considered an administrative goal to the extent that it could have a direct bearing on the viability of course delivery (which resonates with the idea of qualification efficiency).

Qualifications and frameworks

The following subsections identify the goals that appear to have driven qualification designers to have adopted the CASLO approach for key CASLO qualifications from previous sections. We note that design decisions have been driven by different goals for different qualifications.

NVQs and GNVQs

Why was the CASLO approach adopted as the high-level design template for NVQs? From how its designers described and justified the NVQ model, it is possible to identify a number of key drivers.

First, there are strong grounds for believing that the desire to improve domain alignment was the most influential driving force. Remember that the NVQ mission was to develop ‘standards of a new kind’ which were capable of characterising occupational competence comprehensively and authentically, in contrast to the qualifications that preceded them, which were only implicitly defined (in terms of syllabus content and exam materials). It was critical that these new qualifications should target exactly the right kind of competence, and that all concerned – from trainers to learners to users – should understand exactly what that competence looked like. This quotation from Jessup could easily have been uttered by Tyler half a century earlier:

The new competence-based movement is attempting to go back to fundamentals and look at what is really required for successful performance or the achievement of successful outcomes in any field of learning. If one faithfully interprets the nature of competent performance, the less tangible skills (including an awareness of context and appropriateness of different responses) will be included as part of the statement. There would appear to be no intrinsic reason why the specification of outcomes should be narrow.

(Jessup, 1991, page 129)

NVQ standards were intended to provide an explicit, common foundation for planning curriculum, for planning pedagogy, and for planning assessment:

From the standards we can derive the curriculum – what the individual needs to learn to achieve the standard – and the assessment system – how the individual will demonstrate that they have achieved the standard.

(Mansfield & Mitchell, 1996, page 85)

Clear and complete explication of agreed standards was intended to improve alignment in contexts such as workplaces where assessments might otherwise have been expected to be highly subjective (Jessup, 1991). Although NVQ designers did not believe that this detailed explication would enable assessors to judge with perfect objectivity, they did believe that the scaffolding provided by outcomes and criteria would facilitate far greater objectivity.

Second, although it made sense that NVQs ought to certify domain mastery – as indicators of occupational competence – Jessup was explicit that mastery ought to be a fundamental educational goal in its own right, and he specifically referenced Bloom on this issue (Jessup, 1991). It is true that NVQ designers were very resistant to prescribing teaching and learning expectations, largely because they wanted to promote the idea of an individual learning journey, especially for those already in work (see below) who were likely to have very different baseline levels of competence and therefore very different learning needs. Yet, Jessup, in particular, was very clear that his new model of education and training presumed that all qualifications, whether technical, vocational, or general ought to be based upon a mastery learning principle.

Third, another very important goal underpinning NVQ design was qualification efficiency. This was perhaps the most explicitly stated goal within NVQ documentation, although it was articulated in various different ways, often revolving around the concepts of accessibility and flexibility. The transparency afforded by adopting the CASLO approach provided opportunities for individuals to become qualified more efficiently than ever before, for instance, by making use of RPL. This would enable employees to achieve certificates for skills that they had already developed (FEFC, 1997). It even opened the evidence gathering process to sources outside the workplace, including voluntary or leisure activities (NCVQ, 1997c). Enabling already competent, and partially competent, employees to achieve formal certification were key goals for the NVQ system, to promote upskilling and to establish a more mobile workforce (Shackleton & Walsh, 1995). The NVQ model also supported Roll-On-Roll-Off delivery.

The inevitable corollary of RPL was an expectation of tailoring learning experiences to the specific needs of individual learners, rather than forcing all learners to follow exactly the same course of instruction (Jessup, 1991). Talk of common units and credit transfer between qualifications also referenced this goal of qualification efficiency (Jessup, 1991). Finally, NVQ designers believed that the transparency provided by clear and complete standards was educationally empowering, giving learners a degree of control over their own learning that would not have been possible under the classical approach to qualification design. This, too, helped to improve the efficiency of becoming qualified.

Although the NCVQ sought to rationalise TVET qualifications by introducing a qualification framework, the design of this framework was not driven by a strong desire to provide a common currency to support radical domain personalisation via unit exchangeability. The NVQ framework was organised in terms of generic levels, but these indicated little more than a rough hierarchy of occupational roles. NVQs were allocated to a level post hoc, rather than being designed to exhibit a certain level of complexity. Ultimately, each NVQ was tailored to a bespoke occupational role, so its complexity was determined by the demands of the role that it represented.[footnote 12]

Turning attention to GNVQs, it would stand to reason that they might share similar goals to NVQs. This certainly seems true in relation to both domain alignment and domain mastery, which appear to have been just as important drivers for GNVQs as for NVQs. However, it is possible to argue that qualification efficiency might have been somewhat less important a driver for GNVQs, which were more likely to have been delivered as sessional courses within mainstream educational settings, with less need for RPL. Having said that, GNVQs still offered the potential for RPL, particularly in relation to core skills units.[footnote 13] Furthermore, there was a strong drive within both NVQ and GNVQ traditions toward promoting both student-centred learning and learner autonomy, which definitely was linked to the idea of handing control to learners, to help make the process of becoming qualified more efficient. Likewise, the idea of sharing units across qualifications, and even across qualification types, was beginning to gain traction, and this resonates with the qualification efficiency goal.

Although neither NVQs nor GNVQs appear to have been designed with radical domain personalisation in mind, they do appear to have been designed with (minimal) cross-context domain personalisation in mind, particularly GNVQs. A report from the Further Education Unit put it like this:

Because GNVQs are specified in terms of learning outcomes (units of achievement), teachers and learners are able to decide on the kinds of learning activities that will be undertaken in order to achieve the specified outcomes and produce the necessary evidence for assessment.

(FEU, 1994, page 135)

This meant that the acquisition and demonstration of learning outcomes could be tailored to local circumstances, or to students’ interests and strengths. Indeed, Ecclestone quoted an NCVQ official who described this as “liberating teachers from the tyranny of curriculum” (Ecclestone, 2002, page 59). Cross-context domain personalisation would also have been relevant to the NVQ model, to the extent that learning outcomes were meant to be specified at a level of generality that would enable them to apply to the same occupational role undertaken with different employers. On the other hand, these occupational roles were tightly defined, and range statements provided further circumscription. So, there was probably less flexibility built into the NVQ model than the GNVQ one.

Finally, it is worth noting that the GNVQ model was promoted during a period that was particularly friendly to the idea of learning styles – which implied the need to tailor learning activities to suit individual learning style preferences – and this also seemed to be accommodated within the emerging GNVQ philosophy (see FEU, 1994). Thus, GNVQs were consistent with the idea of teaching and learning approach personalisation, even if that may not have been a significant part of the underpinning rationale for adopting the CASLO approach.

TEC and BEC awards

Although both the TEC and the BEC designed qualifications with domain mastery in mind, particularly for TEC awards, neither organisation seemed to apply the mastery principle stringently. So, the domain mastery goal was important, but not dominant.

In contrast, both BEC and TEC awards were heavily driven by the domain alignment goal. The qualifications designed by both councils were intended to support rounded programmes of learning, more so than the qualifications that preceded them, which focused on underpinning knowledge and understanding. Their adoption of a precursor to the CASLO approach can therefore be understood best in terms of a desire to specify domains of learning relevant to industry and commerce as comprehensively and authentically as possible, to minimise ambiguity over the ultimate objectives of BEC and TEC programmes. Bear in mind this quotation from the Haslegrave report, which led to the new TEC and BEC awards:

Technicians should be able to extract information from different sources, analyse it and determine the action to be taken, and adjust the action on the basis of its practical effect. The traditional external examination was an unsatisfactory way of testing ability of this kind.

(Haslegrave, 1969, page 53)

The concern, here, was exactly the same as that identified decades earlier by Ralph Tyler: if you fail to specify what learners need to ‘do’ with the content that they are expected to learn – extract information, analyse it, determine action, adjust action, and so on – then this risks these higher-level functions not being assessed and not being taught. The outcome-based approach adopted by both the TEC and the BEC aimed to mitigate this risk, as both a certification goal and an educational one.[footnote 14]

Finally, it seems fair to conclude that domain personalisation was also an important driver for TEC and BEC awards. Neither council set out to develop frameworks that were capable of supporting the mix and match approach to qualification design that we have associated with third level radical domain personalisation. Furthermore, although they encouraged colleges to develop bespoke units tailored to the needs of local employers, this was not radical domain personalisation, involving the construction of (fourth level) bespoke units for bespoke qualifications. It would have been more like minimal domain personalisation, akin to constructing (second level) optional units for standardised qualifications.[footnote 15] Note that even their standard units were likely to have been compatible with a certain amount of first level (minimal) cross-context domain personalisation.

OCN awards

The commitment of the National Open College Network to establishing a Credit Accumulation and Transfer system suggests that radical domain personalisation may have been the most influential driving force behind adoption of the CASLO approach for OCN and NOCN awards. Although strongly influenced by NVQ developments, the main reason for adopting the approach for OCN awards was to help determine (and defend) the currency of units within the OCN framework, by clarifying, in terms of learning outcomes and assessment criteria, exactly what credits were being awarded for. Clarity over the content, size and complexity of learning outcomes was intended to enable awards to be assigned to an appropriate location in the proposed new national credit framework. Allocating an award to a particular location would establish its currency, such that awards that occupied the same location in the framework would have the same currency, attesting to their comparability across the Open College Networks (Wilson, 2010). This enabled OCN learners to construct personalised learning programmes with national currency.

To achieve this, rather than representing a rough hierarchy of occupational roles, level descriptors suitable for classifying OCN awards would need to define complexity differently. This was attempted by incorporating ideas from Bloom’s Taxonomy (Wilson, 2010). By estimating how long it might take to achieve a set of learning outcomes (size), and by matching those outcomes to a framework level (complexity), the currency of an OCN award within the NOCN framework was established.[footnote 16]

The use of the CASLO approach also appears to have been driven by a desire to facilitate domain mastery. That is, with the move towards specification in terms of learning outcomes, the OCNs formally agreed that awards should be contingent upon actually achieving the specified learning outcomes, and not simply upon having completed the programme of study (Wilson, 2010).

The QCF

A final question concerns intentions underlying the design of the Qualifications and Credit Framework. Again, it is not easy to identify these intentions, as they were never set out in terms of the 4 goals described above. Yet, because the QCF appears to have been strongly influenced by the OCN approach, it seems reasonable to conclude that a principal goal influencing adoption of the CASLO approach within the QCF was a desire to facilitate radical domain personalisation – albeit at the third rather than the fourth level – implying that the CASLO approach was adopted to help support claims concerning comparable demands, common currency, and exchangeability.

It has certainly been said that parity within the QCF provided a basis for claiming that qualifications should be treated equivalently within accountability measures, for example, underpinning the idea of a ‘GCSE equivalent’ qualification for key stage 4 performance table computations (Wolf, 2011). Furthermore, a guidance note on ‘Writing QCF Units: How Much Detail to Provide’ (FAB & JCQ, 2010) was very explicit on how the learning outcomes and assessment criteria within QCF units needed to be written: to provide the level of detail necessary to indicate the ‘amount’ of learning required (to allocate credit), to indicate the ‘demand’ of the learning required (to allocate levels), and to indicate the ‘content’ of the learning required (to ensure that the units would refer to equivalent achievements when employed by different awarding organisations). This was intended to support comparability judgements related to accreditation decisions, and ultimately to support credit transfer across providers.[footnote 17]

In fact, the transparency that was necessary for qualification efficiency CAT (CAT-IA) was probably more important than the transparency that was necessary for radical domain personalisation CAT (CAT-EX). In practice, the mix and match functionality of the QCF was not used very much. Indeed, QCF rules on combining units actively prevented qualifications being assembled “in real time” by employers or learners, which actively constrained radical domain personalisation (Lester, 2011, page 210).

There is little clear-cut evidence from early QCF documentation that either domain alignment or domain mastery were especially strong influences. However, it is quite possible that these goals might simply have been taken for granted, given how embedded the NVQ approach had become by then.

The analysis of CASLO qualifications and frameworks in terms of their goals helps to remind us that the CASLO approach is nothing more than an approach (that is, one approach) to achieving domain alignment, domain mastery, qualification efficiency, and domain personalisation. It is entirely possible to envisage alternative approaches to qualification design that are capable of achieving these high-level goals in different ways. Indeed, there might conceivably be better approaches to facilitating them – better than the classical approach and better than the CASLO approach.

This observation is particularly relevant to our discussion of the QCF. As noted earlier, the QCF was designed on the assumption that it would ultimately encompass all formally assessed learners’ achievements outside higher education. Yet, prioritising qualification efficiency and radical domain personalisation resulted in 2 related problems. First, the QCF ended up being designed to meet the needs of only a subset of learners (and awarding organisations) for whom these goals were clearly relevant.

Second, because these goals recommended a common approach to qualification design across the framework – for which the CASLO approach was chosen – it meant that qualifications that were not well suited to this common approach were distorted. As we have already discussed, this included graded performance exams, including graded exams in music, dance, speech, and drama. It is worth emphasising that these qualifications were already based on a mastery model – the progressive mastery model – and they had their own approach to securing domain alignment. More to the point, they had their own well-established framework, and learners did not stand to benefit from the kind of Credit Accumulation and Transfer anticipated by the QCF. In short, 2 of the QCF design goals were of limited or no relevance to graded performance exams, while the other 2 were already achieved via alternative approaches. In retrospect, it seems fair to conclude that the QCF was designed in a manner that was unsuitable for regulating the full range of qualifications that were eventually accredited to it.[footnote 18]

-

After all, schools today are held to account on the basis of results derived predominantly from classical qualifications. So, the role of outcome-based qualifications in facilitating the marketisation of education is debatable. Likewise, the idea that outcome-based qualifications were introduced to render colleges redundant as centres of technical and vocational education and training seems hard to square with the fact that they were introduced originally by the TEC and the BEC, agencies that were committed to institutional delivery and to the integration of disciplinary knowledge. ↩

-

These distinctions relate to 2 of the 3 perspectives on qualification purposes identified by Newton (2017) – the information perspective and the engagement perspective. The certification perspective is equivalent to the information perspective. The educational perspective is most closely related to the engagement perspective. The sociopolitical perspective does not figure in Newton (2017). ↩

-

Transparency is sometimes discussed as though it were a goal in its own right. We think that it is better understood as a requirement, or mechanism, for achieving a variety of goals. For instance, the CASLO approach helps to make it clear to qualification users what the qualification is intended to certificate. This was certainly an important driver behind adopting the CASLO approach. However, we would argue that this is subsumed within the broader goal of making sure that all participants and stakeholders – teachers, trainers, learners, assessors, and users alike – accurately and consistently interpret what the qualification is intended to certificate, which is our domain alignment goal. ↩

-

Note that we have not identified any CASLO-related certification goals beyond domain alignment. ↩

-

This issue has played out in debates concerning whether the specification of learning outcomes ought to be ‘content-heavy’ (incorporating both syllabus content and cognitive processes in equal measure) or ‘content-light’ (skewed towards cognitive processes with far less prescription over content). Content-light approaches have sometimes been criticised for leading to a “degradation of content” (Hooper, 1971, page 123). ↩

-

Rather than being earned independently, currency is, in effect, guaranteed by the framework owner, who has accredited the unit to the framework (Wilson, 2010). ↩

-

The use of parentheses, here, recognises the subtle, but important, point that the CASLO approach is an idea that we have invented (as the conjunction of certain key design characteristics) to make sense of historical policies and practices. For instance, NVQ designers would have adopted the ‘NVQ approach’ which (in our terminology) happens to incorporate the ‘CASLO approach’. ↩

-

In theory, it is entirely possible to achieve domain personalisation using classically designed units, for example, by creating optional units to sit alongside mandatory ones within a classical qualification. Yet, the underdetermination of outcomes and criteria within classical unit specifications limits the potential for establishing defensible, albeit rough, comparability claims upfront (that is, on the basis of the specification alone, with no empirical data on the performance of candidates). The more radical the personalisation, the rougher any comparability claim will be. Yet, it should still be easier to establish (rough) comparability on the basis of a more transparent CASLO unit specification than on the basis of a less transparent classical one. ↩

-

It could be argued that the CASLO approach enables learners to take greater control over their learning, making self-study a more viable option. Yet, this potential benefit is already captured by the domain alignment goal, linked to the qualification efficiency goal. Furthermore, it is entirely possible to self-study for a classical qualification, as many learners do. ↩

-

There are pros and cons associated with flexibility of this sort, so it needs to be used skilfully. On the one hand, it has the potential to eliminate construct-irrelevant variance (when a learner is unable to demonstrate sufficient proficiency owing to demands associated with a particular assessment format). On the other hand, it also has the potential to create construct-irrelevant variance (when the format provides too much scaffolding, facilitating a successful performance despite the learner being insufficiently proficient). ↩

-

Incidentally, we did not find documentary evidence of it appearing as a substantive rationale in its own right as part of the present research project. ↩

-

Having said that, formal comparability expectations were included in successive versions of the NVQ criteria, for instance: “It is expected that direct comparability between standards will be achieved between similar or adjacent occupational fields. However, comparison across the entire range of occupational fields will be less exact” (NCVQ, 1988, page 18). ↩

-

Particularly in the college context, RPL could become overly bureaucratic and ultimately inefficient. Also, when granted, it excluded learners from (funding for) relevant learning experiences, which impacted class sizes and course viability. ↩

-

It seems reasonable to conclude that BTECs inherited much of their rationale for adopting an outcome-based approach to qualification design from TEC and BEC awards. However, the BTEC route to adopting the CASLO approach was somewhat circuitous, evolving through multiple generations. Indeed, it was only fully adopted during the early 1990s, with mounting pressure to integrate BTECs within the NVQ framework. It is therefore hard to identify a uniquely BTEC-driven rationale for adopting the CASLO approach. ↩

-

Lysons (1982) noted that the core and options pattern favoured by the BEC made it more viable to teach groups with divergent course requirements, which describes second level cross-optional-unit domain personalisation from an administrative perspective (rather than a personal one). ↩

-

As such, adopting the CASLO approach was more a matter of administrative convenience than concern for domain alignment. In other words, the size and complexity of the learning outcomes mattered more than their exact content, which would differ from centre to centre, and potentially from student to student within a centre (Ecclestone, 1992). ↩

-

It noted that it would generally not be possible to port (less transparent) NQF specifications directly into the QCF. ↩

-

Note that the ‘unsuitability’ case was accepted for certain qualifications (including GCSEs and A levels, yet not for others (including graded performance exams). ↩