Our plan to rebuild: The UK Government’s COVID-19 recovery strategy

Updated 24 July 2020

- presented to Parliament by the Prime Minister by Command of Her Majesty

- laid in Parliament on 11 May 2020

- Command Paper number CP 239

- Crown copyright 2020

- ISBN 978-1-5286-1911-0

Foreword from the Prime Minister

We will remember 2020 as the year we were hit, along with all other nations, by a previously unknown and remorseless foe.

Like the rest of the world, we have paid a heavy price. As of 6 May, 30,615 people have lost their lives having tested positive for COVID-19. Every one of those deaths is a tragedy for friends and family: children have lost mothers and fathers; parents have lost sons and daughters, before their time. We should pay tribute to the victims of this virus: those who have died, and their loved ones who remain.

That price could have been higher if not for the extraordinary efforts of our NHS and social care workers and had we not acted quickly to increase the capacity of the NHS. People up and down the UK have made an extraordinary sacrifice, putting their lives on hold and distancing themselves from their loved ones. It would have been higher had we not shielded the most vulnerable - providing help and support to those that need it.

On 3 March we published our plan[footnote 1], and since then millions of hardworking medical, health and care workers, military personnel, shopkeepers, civil servants, delivery and bus drivers, teachers and countless others have diligently and solemnly enacted it.

I said we’d take the right decisions at the right time, based on the science. And I said that the overwhelming priority of that plan was to keep our country safe.

Through the unprecedented action the people of the United Kingdom have taken, we have begun to beat back the virus. Whereas the virus threatened to overwhelm the NHS, our collective sacrifice has meant that at no point since the end of March have we had fewer than one third of our critical care beds free.

We can feel proud of everyone who worked so hard to create Cardiff’s Dragon’s Heart Hospital, Glasgow’s Louisa Jordan Hospital, and the Nightingale Hospitals in London, Belfast, Birmingham, Exeter, Harrogate, Sunderland, Bristol and Manchester. In addition to these new Nightingales, the UK has just over 7,000 critical care beds as of 4 May; an increase from 4,000 at the end of January.

Meanwhile the Government increased daily tests by over 1,000% during April - from 11,041 on 31 March to 122,347 on 30 April. Teachers have worked with Google to create the Oak National Academy - a virtual school - in just two weeks, delivering 2.2 million lessons in its first week of operation. We have supported businesses and workers with a furlough scheme - designed and built from scratch - that has safeguarded 6.3 million jobs. Right across the country we have seen huge ingenuity, drive and selflessness.

Now, with every week that passes, we learn more about the virus and understand more about how to defeat it. But the more we learn, the more we realise how little the world yet understands about the true nature of the threat - except that it is a shared one that we must all work together to defeat.

Our success containing the virus so far has been hard fought and hard won. So it is for that reason that we must proceed with the utmost care in the next phase, and avoid undoing what we have achieved.

This document sets out a plan to rebuild the UK for a world with COVID-19. It is not a quick return to ‘normality.’ Nor does it lay out an easy answer. And, inevitably, parts of this plan will adapt as we learn more about the virus. But it is a plan that should give the people of the United Kingdom hope. Hope that we can rebuild; hope that we can save lives; hope that we can safeguard livelihoods.

It will require much from us all: that we remain alert; that we care for those at most risk; that we pull together as a United Kingdom. We will continue to work with the devolved administrations in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to ensure these outcomes for everybody, wherever they live in the UK.

It is clear that the only feasible long-term solution lies with a vaccine or drug-based treatment. That is why we have helped accelerate this from the start and are proud to be home to two of the world’s most promising vaccine development programmes at Oxford University and Imperial College, supported by a globally renowned pharmaceutical sector.

The recent collaboration between Oxford University and AstraZeneca is a vital step that could help rapidly advance the manufacture of a COVID-19 vaccine. It will also ensure that should the vaccine being developed by Oxford’s Jenner Institute work, it will be available as early as possible, helping to protect thousands of lives from this disease.

We also recognise that a global problem needs a global solution. This is why the United Kingdom has been at the forefront of the international response to the virus, co-hosting the Coronavirus Global Response Summit on 4 May, pledging £388m in aid funding for research into vaccines, tests and treatment including £250m to the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, the largest contribution of any country.

But while we hope for a breakthrough, hope is not a plan. A mass vaccine or treatment may be more than a year away. Indeed, in a worst-case scenario, we may never find a vaccine. So our plan must countenance a situation where we are in this, together, for the long haul, even while doing all we can to avoid that outcome.

I know the current arrangements do not provide an enduring solution – the price is too heavy, to our national way of life, to our society, to our economy, indeed to our long-term public health. And while it has been vital to arrest the spread of the virus, we know it has taken a heavy toll on society - in particular to the most vulnerable and disadvantaged - and has brought loneliness and fear to many.

We’ve asked you to protect those you love by separating yourself from them; but we know this has been tough, and that we must avoid this separation from turning into loneliness.

So this plan seeks to return life to as close to normal as possible, for as many people as possible, as fast and fairly as possible, in a way that is safe and continues to protect our NHS.

The overriding priority remains to save lives.

And to do that, we must acknowledge that life will be different, at least for the foreseeable future. I will continue to put your safety first, while trying to bring back the things that are most important in your lives, and seeking to protect your livelihoods.

That means continuing to bolster the NHS and social care system so it can not only cope with the pressures from COVID-19 but also deliver the Government’s manifesto commitment to continue improving the quality of non-COVID-19 health and social care.

It means a huge national effort to develop, manufacture and prepare to distribute a vaccine, working with our friends and allies around the world to do so.

It means optimising the social distancing measures we’ve asked the nation to follow, so that as the threat changes, the measures change as well - doing as much as possible to suppress the epidemic spread, while minimising the economic and social effects.

That will require a widespread system of testing, of tracing and monitoring the spread of the disease, of shielding the most vulnerable, of protecting those in care homes, of securing our borders against its reintroduction, and of re-designing workplaces and public spaces to make them “COVID-19 Secure.”

Our NHS is already, rightly, the envy of the world. But we now need to build up the other world-leading systems that will protect us in the months ahead.

I must ask the country to be patient with a continued disruption to our normal way of life, but to be relentless in pursuing our mission to build the systems we need. The worst possible outcome would be a return to the virus being out of control – with the cost to human life, and – through the inevitable re-imposition of severe restrictions – the cost to the economy.

We must stay alert, control the virus, and in doing so, save lives.

If we get this right we will minimise deaths – not just from COVID-19, but also from meeting all our non-COVID-19 health needs, because our (bigger) NHS will not be overwhelmed.

We will maximise our economic and societal bounce-back: allowing more people to get on with more of their normal lives and get our economy working again.

Then, as vaccines and treatment become available, we will move to another new phase, where we will learn to live with COVID-19 for the longer term without it dominating our lives.

This is one of the biggest international challenges faced in a generation. But our great country has faced and overcome huge trials before. Our response to these unprecedented and unpredictable challenges must be similarly ambitious, selfless and creative.

Thank you for your efforts so far, and for the part everyone in the UK will play over the months ahead.

1. The current situation

1.1 Phase one

COVID-19 is a new and invisible threat. It has spread to almost every country in the world.

The spread of the virus has been rapid. In the UK at its maximum, the number of patients in intensive care was estimated to be doubling every 3-4 days.

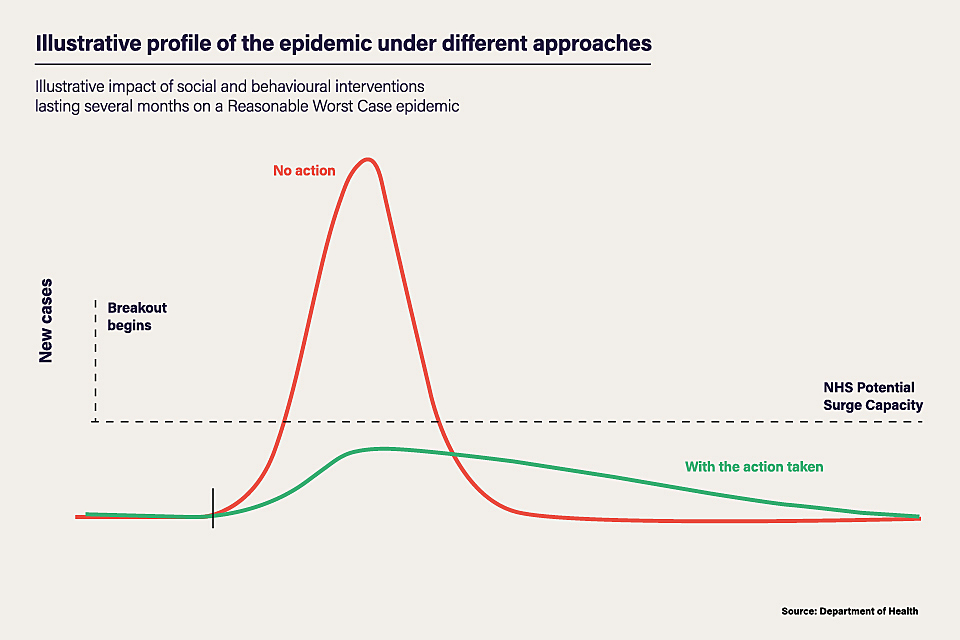

This type of exponential growth would have overwhelmed the NHS were it not contained (as shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1: Illustrative profile of the epidemic under different approaches - Illustrative impact of social and behavioural interventions lasting several months on a Reasonable Worst Case epidemic.

From the start, the Government was guided by science, publishing on 3 March its plan[footnote 2] to contain, delay, and mitigate any outbreak, and use research to inform policy development.

Responding to the advice of Government scientists, on 7 March those with symptoms were asked to self-isolate for 7 days. On 16 March, the Government introduced shielding for the most vulnerable and called on the British public to cease non-essential contact and travel. On 18 March, the Government announced the closure of schools. On 20 March entertainment, hospitality and indoor leisure venues were closed. And on 23 March the Government took decisive steps to introduce the Stay at Home guidance. Working with the devolved administrations, the Government had to take drastic action to protect the NHS and save lives. Delivering this plan was the first phase of the Government’s response, and due to the extraordinary sacrifice of the British people and the efforts of the NHS, this first phase has suppressed the spread of the virus.

In an epidemic, one of the most important numbers is R - the reproduction number. If this is below one, then on average each infected person will infect fewer than one other person; the number of new infections will fall over time. The lower the number, the faster the number of new infections will fall. When R is above one, the number of new infections is accelerating; the higher the number the faster the virus spreads through the population.

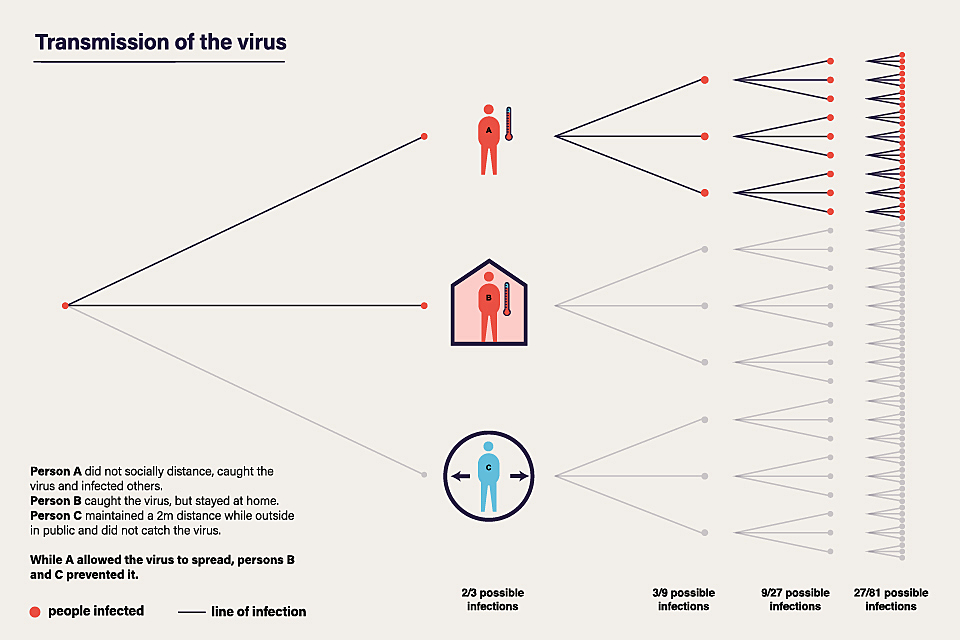

Figure 2: Transmission of the virus - Schematic diagram of the transmission of the virus with an R value of 3, and the impact of social distancing.

In the UK, the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) assessed that R at the beginning of the epidemic was between 2.7 and 3.0; each person with the disease gave it to nearly three other people, on average. But the Government and devolved administration response means SAGE’s latest assessment is that, across the UK, R has reduced to between 0.5 and 0.9, meaning that the number of infected people is falling. The impact of social distancing measures on R is demonstrated in Figure 2.

The Government now sees that:

- There are no regions of the country where the epidemic appears to be increasing.

- As of 9 May, it is estimated that 136,000 people in England are currently infected with COVID-19.[footnote 3]

- The number of patients in hospital in the UK with COVID-19 is under 13,500 as of 4 May; 35% below the peak on 12 April.[footnote 4]

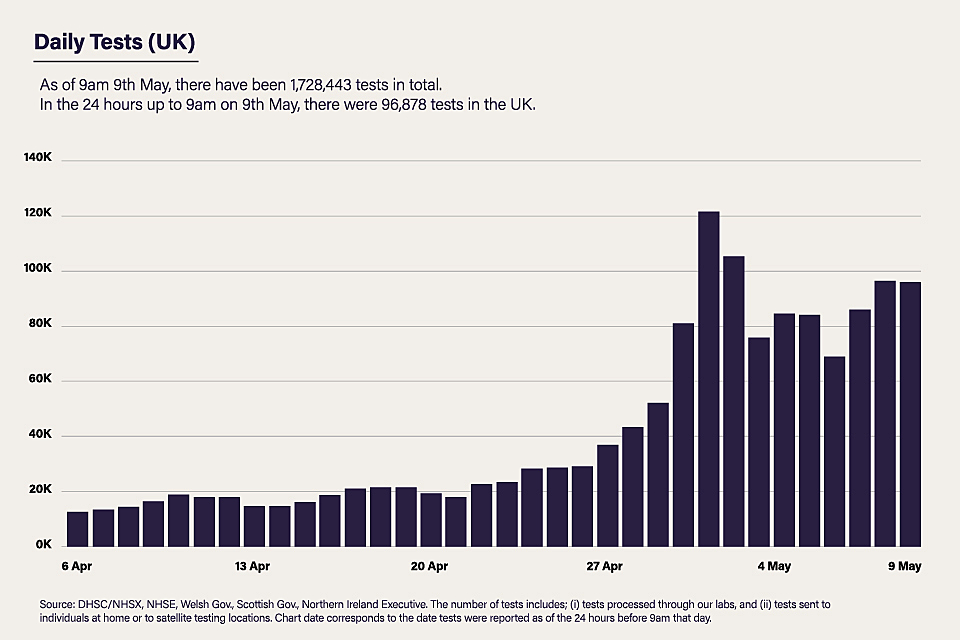

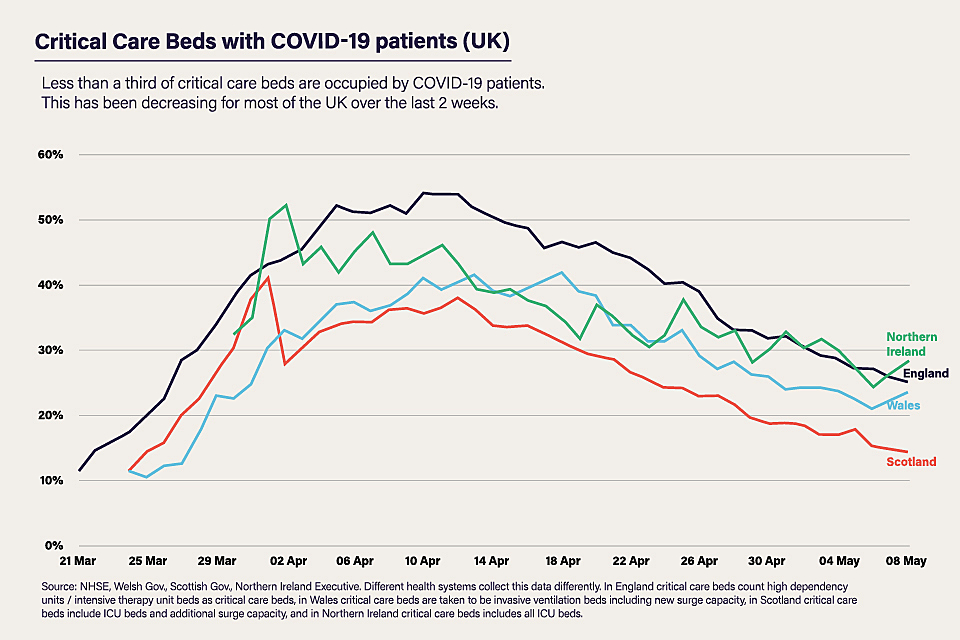

- 27% of NHS critical care beds in the UK were occupied by a COVID-19 patient on 4 May - compared to 51% on 10 April.[footnote 5] At the same time, the Government has invested heavily in its ability to tackle the disease. NHS capacity has increased significantly, with 3,000 new critical care beds across the UK since January[footnote 6], and daily tests have increased by over 1,000% during April - from 11,041 on 31 March to 122,347 on 30 April.[footnote 7]

Figure 3: Daily tests (UK) The number of tests carried out in the UK as of 9am on 9 May

Tragically, however, the number of deaths so far this year is 37,151 higher than the average for 2015 to 2019.[footnote 8] The Government is particularly troubled by the impact of COVID-19 in care homes, where the number of COVID-19 deaths registered as taking place up to 24 April is 6,934,[footnote 9] and by the higher proportion of those who have died of COVID-19 who have been from minority ethnic backgrounds. It is critical that the Government understands why this is occurring. It is why on 4 May Public Health England launched a review into the factors affecting health outcomes from COVID-19, to include ethnicity, gender and obesity. This will be published by the end of May.[footnote 10]

Alongside the social distancing measures the Government has announced in this first phase, it has also taken unprecedented action to support people and businesses through this crisis and minimise deep and long-lasting impacts on the economy. 800,000 employers had applied to the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme to help pay the wages of 6.3m jobs, as of midnight on 3 May.[footnote 11]

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) and the Bank of England have both been clear that if the Government had not taken the actions they had, the situation would be much worse. But despite this, the impact on people’s jobs and livelihoods has been severe: economic activity has been brought to a stop across large swathes of the UK economy. The Government is supporting millions of families and businesses, but cannot protect every job and every business.

Unemployment is rising from a 40-year low at the start of the year; around 1.8m households made claims for Universal Credit between 16 March and 28 April.[footnote 12] The OBR has published a ‘reference’ scenario which suggests that, if the current measures stay in place until June and are then eased over the next three months, unemployment would rise by more than 2 million in the second quarter of 2020.[footnote 13] The OBR’s scenario suggests that GDP could fall by 35% in the second quarter of this year – and the annual contraction could be the largest in over 300 years.[footnote 14]

Workers in those sectors most affected, including hospitality and retail, are more likely to be low paid, younger and female. Younger households are also likely to be disproportionately hit in the longer term, as evidence suggests that, following recessions, lost future earnings potential is greater for young people.[footnote 15]

The longer the virus affects the economy, the greater the risks of long-term scarring and permanently lower economic activity, with business failures, persistently higher unemployment and lower earnings. This would damage the sustainability of the public finances and the ability to fund public services including the NHS. It would also likely lead to worse long-run physical and mental health outcomes, with a significant increase in the prevalence of chronic illness.

1.2 Moving to the next phase

On 16 April the Government presented five tests for easing measures.[footnote 16] These are:

- Protect the NHS’s ability to cope. We must be confident that we are able to provide sufficient critical care and specialist treatment right across the UK.

- See a sustained and consistent fall in the daily death rates from COVID-19 so we are confident that we have moved beyond the peak.

- Reliable data from SAGE showing that the rate of infection is decreasing to manageable levels across the board.

- Be confident that the range of operational challenges, including testing capacity and PPE, are in hand, with supply able to meet future demand.

- Be confident that any adjustments to the current measures will not risk a second peak of infections that overwhelms the NHS.

The Government’s priority is to protect the public and save lives; it will ensure any adjustments made are compatible with these five tests. As set out above, the R is now below 1 – between 0.5 and 0.9 – but potentially only just below 1. The Government has made good progress in satisfying some of these conditions. The ventilated bed capacity of the NHS has increased while the demand placed on it by COVID-19 patients has now reduced (as shown in Figure 4). Deaths in the community are falling. However, real challenges remain on the operational support required for managing the virus. The Government cannot yet be confident that major adjustments now will not risk a second peak of infections that might overwhelm the NHS. Therefore, the Government is only in a position to lift cautiously elements of the existing measures.

Figure 4: Critical care beds with COVID-19 patients (UK) - The percentage of critical care beds with COVID-19 patients up to 8 May.

Different parts of the UK have different R figures. The devolved administrations are making their own assessments about the lifting of measures in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. All governments continue to work together to ensure a coordinated approach across the United Kingdom.

1.3 The challenges ahead

As the Government moves into the next phase of its response to the virus, it is important to be clear about the challenges that the UK, in common with other countries around the world, is now facing.

- This is not a short-term crisis. It is likely that COVID-19 will circulate in the human population long-term, possibly causing periodic epidemics. In the near future, large epidemic waves cannot be excluded without continuing some measures.

- In the near term, we cannot afford to make drastic changes. To successfully keep R below 1, we have little room for manoeuvre. SAGE modelling suggests that either fully opening schools or relaxing all social distancing measures now, will lead to a resurgence of the virus and a second wave that could be larger than the first. In a population where most people are lacking immunity, the epidemic would double in size every few days if no control measures were in place.

- There is no easy or quick solution. Only the development of a vaccine or effective drugs can reliably control this epidemic and reduce mortality without some form of social distancing or contact tracing in place. In the medium-term, allowing the virus to spread in an uncontrolled manner until natural population-level immunity is achieved would put the NHS under enormous pressure. At no point has this been part of the Government’s strategy. If vaccines can be developed they have the potential to stop the disease spreading; treatments would be less likely to stop the spread but could make the virus less dangerous.

- The country must get the number of new cases down. Holding R below 1 will reduce the number of new cases down to a level that allows for the effective tracing of new cases; this in turn, will enable the total number of daily transmissions to be held at a low level.

- The world’s scientific understanding of the virus is still developing rapidly. We are still learning about who is at greatest personal risk and how the virus is spread. It is not possible to know with precision the relative efficacy of specific shielding and suppression measures; nor how many people in the population are or have been infected asymptomatically.

- The virus’ spread is difficult to detect. Some people carry the disease asymptomatically, which may mean that they can spread the virus without knowing that they are infectious. Those who do develop symptoms often do not show signs of being infected for around five days; a significant proportion of infections take place in this time, particularly in the two days before symptoms start. Even those who are not at risk of significant harm themselves may pose a real risk of inadvertently infecting others. This is why a significant part of the next phase of the Government’s response will be to improve its monitoring of and response to new infections.

- The Government must prepare for the challenges that the winter flu season will bring. This will have wide-ranging effects, from impeding any efforts to trace the virus (because so many people without COVID-19 are likely to have symptoms that resemble COVID-19), to increasing the demand for hospital beds.

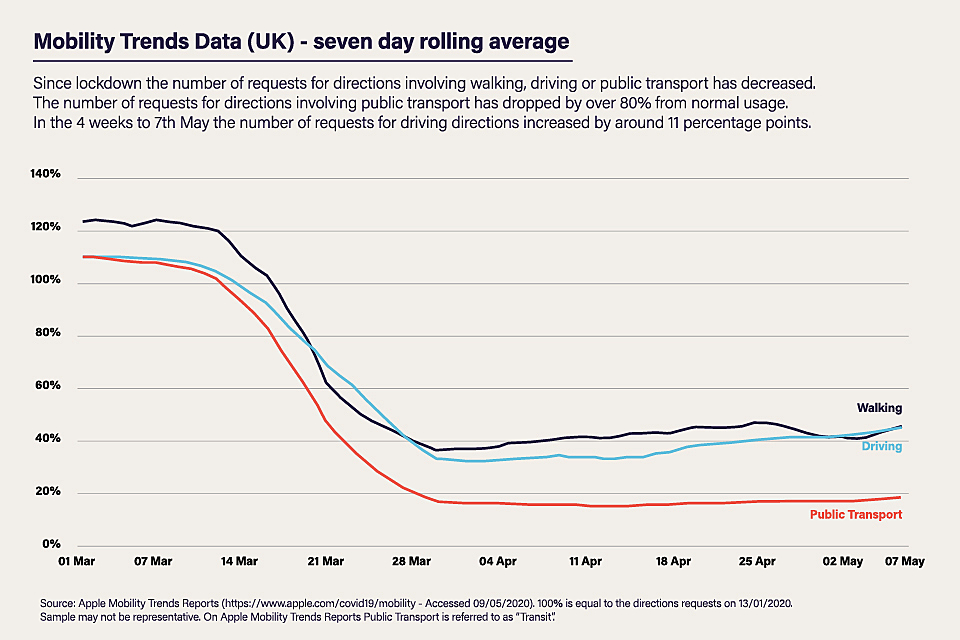

- The plan depends on continued widespread compliance. So far people have adhered to the measures well, as depicted in Figure 5 below. However, to avoid R tipping above 1 and the epidemic increasing in an uncontrolled manner, very high continued levels of compliance are essential. The risk is an unbalanced one; if the UK tips back into an exponential increase in the spread of the infection, it could quickly get out of control.

Figure 5: Mobility trends data for the UK based on a seven-day rolling average up to 7 May

Reflecting these challenges, the rest of this document sets out a cautious roadmap to ease existing measures in a safe and measured way, subject to successfully controlling the virus and being able to monitor and react to its spread. The roadmap will be kept constantly under review as the epidemic, and the world’s understanding of it, develops.

2. Our aims: saving lives; saving livelihoods

The Government’s aim has been to save lives. This continues to be the overriding priority at the heart of this plan.

The Government must also seek to minimise the other harms it knows the current restrictive measures are causing - to people’s wellbeing, livelihoods, and wider health. But there is a risk that if the Government rushes to reverse these measures, it would trigger a second outbreak that could overwhelm the NHS. So the UK must adapt to a new reality - one where society can return to normal as far as possible; where children can go to school, families can see one another and livelihoods can be protected, while also continuing to protect against the spread of the disease.

Therefore the Government’s aim at the centre of this plan is to:

return to life as close to normal as possible, for as many people as possible, as fast and fairly as possible….

…in a way that avoids a new epidemic, minimises lives lost and maximises health, economic and social outcomes.

To do this, the Government will need to steadily redesign the current social distancing measures with new, smarter measures that reflect the level of risk at that point in time, and carefully wind down economic support schemes while people are eased back into work. The Government will do this by considering three main factors.

2.1 Health effect

The first consideration is the nation’s health. The Government must consider overall health outcomes, not just those directly caused by COVID19. As advised by the Chief Medical Officer and NHS England, the Government will take into account:

- Direct COVID-19 mortality, those who die from the virus, despite receiving the best medical care.

- Indirect harms arising from NHS emergency services being overwhelmed and therefore providing significantly less effective care both for those with COVID-19 and for those with other medical emergencies.

- Increases in mortality or other ill health as a result of measures we have had to take including postponement of important but non-urgent medical care and public health programmes while the NHS is diverting resources to manage the epidemic, or from unintended consequences such as people deciding not to seek treatment when they need it, and from increased isolation and effects on mental health;[footnote 17] and

- The long-term health effects of any increase in deprivation arising from economic impacts, as deprivation is strongly linked to ill health.[footnote 18]

As with many other respiratory infections, it is impossible to guarantee that nobody will be infected with this virus in the future, or that none of those infections will lead to tragic deaths. However, it is important to be clear that there is no part of this plan that assumes an ‘acceptable’ level of infection or mortality.

The biggest threat to life remains the risk of a second peak that overwhelms the healthcare system this winter, when it will be under more pressure and the NHS still needs to deliver non-urgent care. A second peak would also trigger a return of the wider health, economic and social harms associated with the first outbreak. This plan aims to minimise this risk.

2.2 Economic effect

The second consideration is protecting and restoring people’s livelihoods and improving people’s living standards. Ultimately, a strong economy is the best way to protect people’s jobs and ensure that the Government can fund the country’s vital public services including the healthcare response. This means the Government will take into account:

- the short-term economic impact, including the number of people who can return to work where it is safe to do so, working with businesses and unions to help people go back to workplaces safely;

- the country’s long-term economic future, which could be harmed by people being out of jobs and by insolvencies, and investing in supporting an economic bounce back;

- the sustainability of public finances so the Government can pay for public services and the healthcare response;

- financial stability so that the banks and others can continue to provide finance to the economy;

- the distributional effects, and so considering carefully the Government’s measures on different income and age groups, business sectors and parts of the country.

The Government also needs to protect the UK’s international economic competitiveness. This means, where possible, seeking new economic opportunities, for example for the UK’s world-leading pharmaceutical and medical-device manufacturing sectors.

2.3 Social effect

The third consideration is the wider effect of the social distancing measures on how the public live their daily lives. The Government recognises that social distancing measures can exacerbate societal challenges, from the negative impacts on people’s mental health and feelings of isolation, to the risks of domestic abuse and online fraud. The Government must act to minimise the adverse social costs - both their severity and duration - for the greatest number of people possible. This means the Government will take into account:

- the number of days of education children lose;

- the fairness of any actions the Government takes, especially the impact on those most affected by social distancing measures; and

- the importance of maintaining the strength of the public services and civic organisations on which the UK relies, especially those that protect or support society’s most vulnerable.

2.4 Feasibility

Underpinning these three factors is a crucial practical constraint: considering the risk and feasibility of any action the Government undertakes. This includes considering the technological risk of any courses the Government pursues, the timelines to implement novel technologies, and the Government’s ability to work with global partners. Much of what is desirable is not yet possible. So the Government’s plan considers carefully when and where to take risk. A ‘zero risk’ approach will not work in these unprecedented times. The Government will have to invest in experimental technologies, some of which are likely not to work as intended, or even prove worthless. But waiting for complete certainty is not an option.

2.5 Overarching principles

Underpinning the factors above are some guiding principles:

-

Informed by the science. The Government will continue to be guided by the best scientific and medical advice to ensure that it does the right thing at the right time.

-

Fairness. The Government will, at all times, endeavour to be fair to all people and groups.

-

Proportionality. The Government will ensure that all measures taken to control the virus are proportional to the risk posed, in terms of the social and economic implications.

-

Privacy. The Government will always seek to protect personal privacy and be transparent with people when enacting measures that, barring this once-in-a-century event, would never normally be considered.

-

Transparency. The Government will continue to be open with the public and parliamentarians, including by making available the relevant scientific and technical advice. The Government will be honest about where it is uncertain and acting at risk, and it will be transparent about the judgements it is making and the basis for them. In meeting these principles, the UK Government will work in close cooperation with the devolved administrations in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to make this a UK-wide response: coherent, coordinated and comprehensive. Part of that UK wide approach will be acknowledging that the virus may be spreading at different speeds in different parts of the UK. Measures may need to change in different ways and at different times. For advice, please see guidance set by the Northern Ireland Executive, the Scottish Government and the Welsh Government.

Balancing the different considerations will involve some difficult choices. For example, the Government will face a choice between the extent and speed of the freedoms enjoyed by some lower-risk people and the risk to others: if all people at lower personal risk were allowed to resume their lives exactly as before the outbreak, this would increase the level of risk to those that are more vulnerable.

3. Our approach: a phased recovery

As the UK exits phase one of the Government’s response, where the Government has sought to contain, delay, research and mitigate, it will move through two further phases.

Phase two: Smarter controls

Until the UK can reach phase three, the Government will gradually replace the existing social restrictions with smarter measures that balance its aims as effectively as possible.

The Government will enact measures that have the largest effect on controlling the epidemic but the lowest health, economic and social costs.

These will be developed and announced in periodic ‘steps’ over the coming weeks and months, seeking to maximise the pace at which restrictions are lifted, but with strict conditions to move from each step to the next. The Government will maintain options to react to a rise in transmissions, including by reimposing restrictions if required.

Over time, the Government will improve the effectiveness of these measures and introduce more reactive or localised measures through widespread, accurate monitoring of the disease. That will enable the lifting of more measures for more people, at a faster pace. Meanwhile, the Government will continue to increase NHS and social care capacity to ensure care for all COVID-19 patients while restoring ‘normal’ healthcare provision.

Phase three: Reliable treatment

Eradication of the virus from the UK (and globally) is very unlikely. But rolling out effective treatments and/or a vaccine will allow us to move to a phase where the effect of the virus can be reduced to manageable levels.

To bring about this phase as quickly as possible, the Government is investing in research, developing international partnerships and putting in place the infrastructure to manufacture and distribute treatments and/or a vaccine at scale.

3.1 Phase two: smarter controls

Throughout this phase, people will need to minimise the spread of the disease through continuing good hygiene practices: hand washing, social distancing and regular disinfecting of surfaces touched by others. These will be in place for some time.

The number of social contacts people make each day must continue to be limited, the exposure of vulnerable groups must continue to be reduced from normal levels, and symptomatic and diagnosed individuals will still need to isolate. Over time, social contact will be made less infectious by:

- making such contact safer (including by redesigning public and work spaces, and those with symptoms self-isolating) to reduce the chance of infection per contact;

- reducing infected people’s social contact by using testing, tracing and monitoring of the infection to better focus restrictions according to risk; and

- stopping hotspots developing by detecting infection outbreaks at a more localised level and rapidly intervening with targeted measures. In the near term, the degree of social contact within the population continues to serve as a proxy for the transmission of the virus; the fewer contacts, the lower the risk.

Developing smarter social distancing measures will mean the Government needs to balance increasing contacts as it relaxes the most disruptive measures with introducing new measures to manage risk, for example by tightening other measures. The more contacts in one area - for example, if too many people return to physical workplaces - the fewer are possible elsewhere - for example, not as many children can return to school. The lower the level of infection at each point in time, the more social contact will be possible.

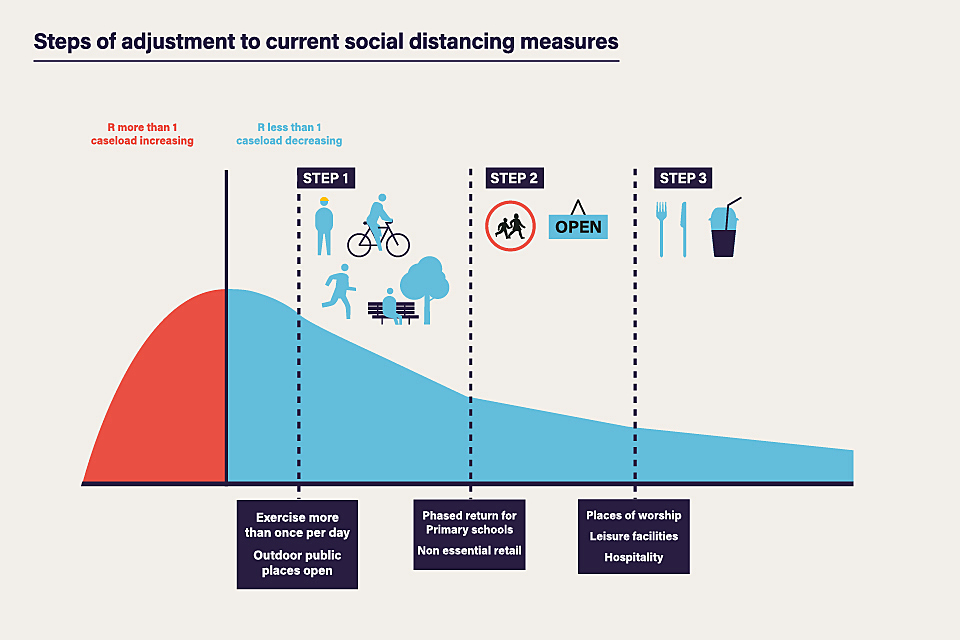

Regular steps of adjustments to current measures

Over the coming months, the Government will therefore introduce a range of adjustments to current social distancing controls, timing these carefully according to both the current spread of the virus and the Government’s ability to ensure safety. These will happen in “steps,” as set out in the next chapter, with strict conditions to safely move from each step to the next.

Figure 6: Steps of adjustment to current social distancing measures - As the caseload falls, different steps can be taken to adjust social distancing measures.

Each step may involve adding new adjustments to the existing restrictions or taking some adjustments further (as shown in Figure 6). For example, while reopening outdoor spaces and activities (subject to continued social distancing) comes earlier in the roadmap because the risk of transmission outdoors is significantly lower, it is likely that reopening indoor public spaces and leisure facilities (such as gyms and cinemas), premises whose core purpose is social interaction (such as nightclubs), venues that attract large crowds (like sports stadia), and personal care establishments where close contact is inherent (like beauty salons) may only be fully possible significantly later depending on the reduction in numbers of infections.

The next chapter sets out an indicative roadmap, but the precise timetable for these adjustments will depend on the infection risk at each point, and the effectiveness of the Government’s mitigation measures like contact tracing.

Over the coming weeks and months, the Government will monitor closely the effect of each adjustment, using the effect on the epidemic to gauge the appropriate next step.

Initially, the gap between steps will need to be several weeks, to allow sufficient time for monitoring. However, as the national monitoring systems become more precise and larger-scale, enabling a quicker assessment of the changes, this response time may reduce. Restrictions may be adjusted by the devolved administrations at a different pace in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland because the level of infection - and therefore the risk - will differ. Similarly in England, the Government may adjust restrictions in some regions before others: a greater risk in Cornwall should not lead to disproportionate restrictions in Newcastle if the risk is lower.

“COVID-19 Secure” guidelines

Many measures require the development of new safety guidelines that set out how each type of physical space can be adapted to operate safely. The Government has been consulting relevant sectors, industry bodies, local authorities, trades unions, the Health and Safety Executive and Public Health England on their development and will release them this week.

They will also include measures that were unlikely to be effective when the virus was so widespread that full stay-at-home measures were required, but that may now have some effect as the public increase the number of social contacts - including, for example, advising the use of face coverings in enclosed public areas such as on public transport and introducing stricter restrictions on international travellers.

Many businesses across the UK have already been highly innovative in developing new, durable ways of doing business, such as moving online or adapting to a delivery model. Many of these changes, like increased home working, have significant benefits, for example, reducing the carbon footprint associated with commuting. The Government will need to continue to ask all employers and operators of communal spaces to be innovative in developing novel approaches; UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) will welcome grant applications for proposals to develop new technologies and approaches that help the UK mitigate the impact of this virus.

Protecting the most clinically vulnerable people

Some people have received a letter from the NHS, their clinician or their GP telling them that as a result of having certain medical conditions, they are considered to be clinically extremely vulnerable.[footnote 19] Throughout this period, the Government will need to continue an extensive programme of shielding for this group while the virus continues to circulate.[footnote 20] The Government will also have to adjust its protections for other vulnerable locations like prisons and care homes,[footnote 21] based on an understanding of the risk.

Those in the clinically extremely vulnerable cohort will continue to be advised to shield themselves for some time yet, and the Government recognises the difficulties this brings for those affected. Over the coming weeks, the Government will continue to introduce more support and assistance for these individuals so that they have the help they need as they stay shielded. And the Government will bring in further measures to support those providing the shield - for example, continuing to prioritise care workers for testing and protective equipment.

A more differentiated approach to risk

As the UK moves into phase two, the Government will continue to recognise that not everybody’s or every group’s risk is the same; the level of threat posed by the virus varies across the population, in ways the Government currently only partly understands.

As the Government learns more about the disease and the risk factors involved, it expects to steadily make the risk-assessment more nuanced, giving confidence to some previously advised to shield that they may be able to take more risk; and identifying those who may wish to be more cautious. The Government will need to consider both risk to self, and risk of transmitting to others.

It is vital that those who are showing symptoms, however mild, must continue to self-isolate at home, as now, and that the household quarantine rules continue to apply. However, as the Government increases the availability and speed of swab testing it will be able to confirm more quickly whether suspected cases showing symptoms have COVID-19 or not. This will reduce the period of self-isolation for those who do not have COVID-19 and their household members.

The Government also anticipates targeting future restrictions more precisely than at present, where possible, for example relaxing measures in parts of the country that are lower risk, but continuing them in higher risk locations when the data suggests this is warranted. For example, it is likely that over the coming months there may be local outbreaks that will require reactive measures to be implemented reactively to maintain control of transmission.

Reactive measures

If the data suggests the virus is spreading again, the Government will have to tighten restrictions, possibly at short notice. The aim is to avoid this by moving gradually and by monitoring carefully the effect of each step the Government takes.

The scientific advice is clear that there is scope to go backwards; as restrictions are relaxed, if people do not stay alert and diligently apply those still in place, transmissions could increase, R would quickly tip above one, and restrictions would need to be re-imposed.

3.2 Phase three: reliable treatment

Humanity has proved highly effective at finding medical countermeasures to infectious diseases, and is likely to do so for COVID-19; but this may take time. As quickly as possible, the Government must move to a more sustainable solution, where the continued restrictions described above can be lifted altogether. To enable this, the Government must develop, trial, manufacture and distribute reliable treatments or vaccines as swiftly as possible.

The virus is unlikely to die out spontaneously; nor is it likely to be eradicated. Only one human infectious disease - smallpox - has ever been eradicated. The Government must therefore develop either a treatment that enables us to manage it like other serious diseases or have people acquire immunity by vaccination.

It is possible a safe and effective vaccine will not be developed for a long time (or even ever), so while maximising the chances this will happen quickly where the Government can, it must not rely on this course of action happening. There are currently over 70 credible vaccine development programmes worldwide and the first UK human trial has begun at the University of Oxford.

Even if it is not possible to develop an effective vaccine, it may be possible to develop drug treatments to reduce the impact of contracting COVID-19, as has been done for many other infectious diseases, ranging from other pneumonias and herpes infections, to HIV and malaria.

For example, drugs might treat the virus itself and prevent disease progression, be used to limit the risk of being infected, or be used in severe cases to prevent progression to severe disease, shorten time in intensive care and reduce the chance of dying.

Researchers may find some effective treatments imminently – for example from repurposing existing drugs – or might not do so for a long time. Not all treatments that have an effect will be game-changing; the best scientific advice is that it is likely any drugs that substantially reduce mortality or are protective enough to change the course of the epidemic will have to be designed and developed specifically for COVID-19, and that this will take time, with success not guaranteed.

However, notwithstanding that many of these will fail, the economic and societal benefits of success mean the Government will do all it can to develop and roll-out both treatments and vaccines at the fastest possible rate; the second phase is a means of managing things until the UK reaches this point.

4. Our roadmap to lift restrictions step-by-step

The Government has a carefully planned timetable for lifting restrictions, with dates that should help people to plan. This timetable depends on successfully controlling the spread of the virus; if the evidence shows sufficient progress is not being made in controlling the virus then the lifting of restrictions may have to be delayed.

We cannot predict with absolute certainty what the impact of lifting restrictions will be. If, after lifting restrictions, the Government sees a sudden and concerning rise in the infection rate then it may have to re-impose some restrictions. It will seek to do so in as limited and targeted a way as possible, including reacting by re-imposing restrictions in specific geographic areas or in limited sectors where it is proportionate to do so.

4.1 Step One

The changes to policy in this step will apply from Wednesday 13 May in England. As the rate of infection may be different in different parts of the UK, this guidance should be considered alongside local public health and safety requirements for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Work

For the foreseeable future, workers should continue to work from home rather than their normal physical workplace, wherever possible. This will help minimise the number of social contacts across the country and therefore keep transmissions as low as possible. All those who work are contributing taxes that help pay for the healthcare provision on which the UK relies. People who are able to work at home make it possible for people who have to attend workplaces in person to do so while minimising the risk of overcrowding on transport and in public places.

All workers who cannot work from home should travel to work if their workplace is open. Sectors of the economy that are allowed to be open should be open, for example this includes food production, construction, manufacturing, logistics, distribution and scientific research in laboratories. The only exceptions to this are those workplaces such as hospitality and non-essential retail which during this first step the Government is requiring to remain closed.[footnote 22] As soon as practicable, workplaces should follow the new “COVID-19 Secure” guidelines, as set out in the previous chapter, which will be published this week. These will ensure the risk of infection is as low as possible, while allowing as many people as possible to resume their livelihoods.

It remains the case that anyone who has symptoms, however mild, or is in a household where someone has symptoms, should not leave their house to go to work. Those people should self-isolate, as should those in their households.

Schools

The rate of infection remains too high to allow the reopening of schools for all pupils yet. However, it is important that vulnerable children (including children in need, those with an Education, Health and Care plan and those assessed as otherwise vulnerable by educational providers or local authorities)[footnote 23] and the children of critical workers are able to attend school, as is currently permitted. Approximately 2% of children are attending school in person,[footnote 24] although all schools are working hard to deliver lessons remotely.

But there is a large societal benefit from vulnerable children, or the children of critical workers, attending school: local authorities and schools should therefore urge more children who would benefit from attending in person to do so.

The Government is also amending its guidance to clarify that paid childcare, for example nannies and childminders, can take place subject to being able to meet the public health principles at Annex A, because these are roles where working from home is not possible. This should enable more working parents to return to work.

Travel

While most journeys to work involve people travelling either by bike, by car or on foot, public transport takes a significant number of people to work across the country, but particularly in urban centres and at peak times. As more people return to work, the number of journeys on public transport will also increase. This is why the Government is working with public transport providers to bring services back towards pre-COVID-19 levels as quickly as possible. This roadmap takes the impact on public transport into account in the proposed phased easing of measures.

When travelling everybody (including critical workers) should continue to avoid public transport wherever possible. If they can, people should instead choose to cycle, walk or drive, to minimise the number of people with whom they come into close contact. It is important many more people can easily travel around by walking and cycling, so the Government will increase funding and provide new statutory guidance to encourage local authorities to widen pavements, create pop-up cycle lanes, and close some roads in cities to traffic (apart from buses) as some councils are already proposing.

Social distancing guidance on public transport must be followed rigorously. As with workplaces, transport operators should follow appropriate guidance to make their services COVID-19 Secure; this will be published this week.

Face-coverings

As more people return to work, there will be more movement outside people’s immediate household. This increased mobility means the Government is now advising that people should aim to wear a face-covering in enclosed spaces where social distancing is not always possible and they come into contact with others that they do not normally meet, for example on public transport or in some shops. Homemade cloth face-coverings can help reduce the risk of transmission in some circumstances. Face-coverings are not intended to help the wearer, but to protect against inadvertent transmission of the disease to others if you have it asymptomatically.

A face covering is not the same as a facemask such as the surgical masks or respirators used as part of personal protective equipment by healthcare and other workers. These supplies must continue to be reserved for those who need it. Face-coverings should not be used by children under the age of two, or those who may find it difficult to manage them correctly, for example primary age children unassisted, or those with respiratory conditions. It is important to use face-coverings properly and wash your hands before putting them on and taking them off.[footnote 25]

Public spaces

SAGE advise that the risk of infection outside is significantly lower than inside, so the Government is updating the rules so that, as well as exercise, people can also now spend time outdoors subject to: not meeting up with any more than one person from outside your household; continued compliance with social distancing guidelines to remain two metres (6ft) away from people outside your household; good hand hygiene, particularly with respect to shared surfaces; and those responsible for public places being able to put appropriate measures in place to follow the new COVID-19 secure guidance.

People may exercise outside as many times each day as they wish. For example, this would include angling and tennis. You will still not be able to use areas like playgrounds, outdoor gyms or ticketed outdoor leisure venues, where there is a higher risk of close contact and touching surfaces. You can only exercise with up to one person from outside your household - this means you should not play team sports, except with members of your own household.

People may drive to outdoor open spaces irrespective of distance, so long as they respect social distancing guidance while they are there, because this does not involve contact with people outside your household.

When travelling to outdoor spaces, it is important that people respect the rules in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland and do not travel to different parts of the UK where it would be inconsistent with guidance or regulations issued by the relevant devolved administration.

These measures may come with some risk; it is important that everyone continues to act responsibly, as the large majority have done to date. The infection rate will increase if people begin to break these rules and, for example, mix in groups in parks, which will trigger the need for further restrictions.

Protecting the clinically vulnerable

It remains the case that some people are more clinically vulnerable to COVID-19 than others. These include those aged over 70, those with specific chronic pre-existing conditions and pregnant women.[footnote 26] These clinically vulnerable people should continue to take particular care to minimise contact with others outside their households, but do not need to be shielded.

Those in the clinically extremely vulnerable group are strongly advised to stay at home at all times and avoid any face-to-face contact; this is called ‘shielding’. It means not leaving the house or attending gatherings at all, with very limited exceptions. Annex B sets out more detail on the guidance applicable to different vulnerable groups at this time. The Government knows people are taking shielding advice seriously and is acutely aware of the huge commitment and resolve it requires to keep away from family and friends. Unfortunately, the current level of transmission of the virus is such that the Government needs to continue to ask that the guidance is followed. In recognition of the challenge faced by those shielding, the Government is:

- Providing essential food to those unable to leave their home. Over one million food boxes have now been delivered in England by wholesalers to those shielding who asked for help with food, with hundreds of thousands more to follow in the coming weeks.[footnote 27] The Government has also arranged priority access to supermarket deliveries for those who have said they need it.

- Facilitating volunteer support. Up to 200,000 calls a day have been made to the shielded in England to confirm their support needs,[footnote 28] and councils are helping to support them in other ways - including, in some cases, organising regular calls from volunteers to those isolated. Those who are shielding can also directly request the support of NHS Volunteer Responders.

The Government is also aware that when – in time – other members of society return to aspects of their normal daily lives, the challenge for those being asked to shield may deepen. The Government will continue to review the support needs of those shielding and the Government will continue to provide support to individuals for as long as they need its direct help.

Along with the support the Government is providing to those shielding, it will provide vital support for other vulnerable people, such as those at risk of loneliness. The Government is continuing to work to further support these groups, including by providing vital financial support to frontline charities working in these areas. The GOV.UK website provides information about the huge range of support that is available including from local authorities and the voluntary and community sector. The Government will continue to update GOV.UK as new services and support become available.

As the UK recovers, the Government will ensure people with disabilities can have independent lives and are not marginalised. This will include making sure that they can access public services and will consider their needs as the Government creates safe work environments and reopen the transport system. The Government will ensure their overall health outcomes do not suffer disproportionately.

Enforcement

The Government is examining more stringent enforcement measures for non-compliance, as it has seen in many other countries. The Government will impose higher fines to reflect the increased risk to others of breaking the rules as people are returning to work and school. The Government will seek to make clearer to the public what is and is not allowed.

Parliament

It is vital that Parliament can continue to scrutinise the Government, consider the Government’s ambitious legislative agenda and legislate to support the COVID-19 response. Parliament must set a national example of how business can continue in this new normal; and it must move, in step with public health guidance, to get back to business as part of this next step, including a move towards further physical proceedings in the House of Commons.

International travel

As the level of infection in the UK reduces, and the Government prepares for social contact to increase, it will be important to manage the risk of transmissions being reintroduced from abroad.

Therefore, in order to keep overall levels of infection down and in line with many other countries, the Government will introduce a series of measures and restrictions at the UK border. This will contribute to keeping the overall number of transmissions in the UK as low as possible. First, alongside increased information about the UK’s social distancing regime at the border, the Government will require all international arrivals to supply their contact and accommodation information. They will also be strongly advised to download and use the NHS contact tracing app.

Second, the Government will require all international arrivals not on a short list of exemptions to self-isolate in their accommodation for fourteen days on arrival into the UK. Where international travellers are unable to demonstrate where they would self-isolate, they will be required to do so in accommodation arranged by the Government. The Government is working closely with the devolved administrations to coordinate implementation across the UK.

Small exemptions to these measures will be in place to provide for continued security of supply into the UK and so as not to impede work supporting national security or critical infrastructure and to meet the UK’s international obligations. All journeys within the Common Travel Area will also be exempt from these measures.

These international travel measures will not come into force on 13 May but will be introduced as soon as possible. Further details, and guidance, will be set out shortly, and the measures and list of exemptions will be kept under regular review.

4.2 Step Two

The content and timing of the second stage of adjustments will depend on the most up-to-date assessment of the risk posed by the virus. The five tests set out in the first chapter must justify changes, and they must be warranted by the current alert level.

They will be enabled by the programmes set out in the next chapter and, in particular, by continuing to bolster test and trace capabilities, protect care homes and support the clinically extremely vulnerable. It is possible that the dates set out below will be delayed if these conditions are not met. Changes will be announced at least 48 hours before coming into effect.

To aid planning, the Government’s current aim is that the second step will be made no earlier than Monday 1 June, subject to these conditions being satisfied. Until that time the restrictions currently in place around the activities below will continue. The Government will work with the devolved administrations to ensure that the changes for step two and beyond are coordinated across the UK. However, there may be circumstances where different measures will be lifted at different times depending on the variance in rate of transmission across the UK.

The current planning assumption for England is that the second step may include as many of the following measures as possible, consistent with the five tests. Organisations should prepare accordingly.

- A phased return for early years settings and schools. Schools should prepare to begin to open for more children from 1 June. The Government expects children to be able to return to early years settings, and for Reception, Year 1 and Year 6 to be back in school in smaller sizes, from this point. This aims to ensure that the youngest children, and those preparing for the transition to secondary school, have maximum time with their teachers. Secondary schools and further education colleges should also prepare to begin some face to face contact with Year 10 and 12 pupils who have key exams next year, in support of their continued remote, home learning. The Government’s ambition is for all primary school children to return to school before the summer for a month if feasible, though this will be kept under review. The Department of Education will engage closely with schools and early years providers to develop further detail and guidance on how schools should facilitate this.

- Opening non-essential retail when and where it is safe to do so, and subject to those retailers being able to follow the new COVID-19 Secure guidelines. The intention is for this to happen in phases from 1 June; the Government will issue further guidance shortly on the approach that will be taken to phasing, including which businesses will be covered in each phase and the timeframes involved. All other sectors that are currently closed, including hospitality and personal care, are not able to re-open at this point because the risk of transmission in these environments is higher. The opening of such sectors is likely to take place in phases during step three, as set out below.

- Permitting cultural and sporting events to take place behind closed-doors for broadcast, while avoiding the risk of large-scale social contact.

- Re-opening more local public transport in urban areas, subject to strict measures to limit as far as possible the risk of infection in these normally crowded spaces.

Social and family contact

Since 23 March the Government has asked people to only leave the house for very limited purposes and this has been extraordinarily disruptive to people’s lives.

In particular this has affected the isolated and vulnerable, and those who live alone. As restrictions continue, the Government is considering a range of options to reduce the most harmful social effects to make the measures more sustainable.

For example, the Government has asked SAGE to examine whether, when and how it can safely change the regulations to allow people to expand their household group to include one other household in the same exclusive group.[footnote 29]

The intention of this change would be to allow those who are isolated some more social contact, and to reduce the most harmful effects of the current social restrictions, while continuing to limit the risk of chains of transmission. It would also support some families to return to work by, for example, allowing two households to share childcare.[footnote 30]

This could be based on the New Zealand model of household “bubbles” where a single “bubble” is the people you live with.[footnote 31] As in New Zealand, the rationale behind keeping household groups small is to limit the number of social contacts people have and, in particular, to limit the risk of inter-household transmissions.[footnote 32]

In addition, the Government is also examining how to enable people to gather in slightly larger groups to better facilitate small weddings.

Over the coming weeks, the Government will engage on the nature and timing of the measures in this step, in order to consider the widest possible array of views on how best to balance the health, economic and social effects.

4.3 Step Three

The next step will also take place when the assessment of risk warrants further adjustments to the remaining measures. The Government’s current planning assumption is that this step will be no earlier than 4 July, subject to the five tests justifying some or all of the measures below, and further detailed scientific advice, provided closer to the time, on how far we can go.

The ambition at this step is to open at least some of the remaining businesses and premises that have been required to close, including personal care (such as hairdressers and beauty salons) hospitality (such as food service providers, pubs and accommodation), public places (such as places of worship) and leisure facilities (like cinemas). They should also meet the COVID-19 Secure guidelines. Some venues which are, by design, crowded and where it may prove difficult to enact distancing may still not be able to re-open safely at this point, or may be able to open safely only in part. Nevertheless the Government will wish to open as many businesses and public places as the data and information at the time allows.

In order to facilitate the fastest possible re-opening of these types of higher-risk businesses and public places, the Government will carefully phase and pilot re-openings to test their ability to adopt the new COVID-19 Secure guidelines. The Government will also monitor carefully the effects of re-opening other similar establishments elsewhere in the world, as this happens. The Government will establish a series of taskforces to work closely with stakeholders in these sectors to develop ways in which they can make these businesses and public places COVID-19 Secure.

5. Fourteen supporting programmes

To deliver our phased plan, the Government will deliver fourteen programmes of work, all of which are ambitious in their scope, scale and timeframes.

5.1 NHS and care capacity and operating model

First, to maximise its confidence in managing new cases, the Government needs to continue to secure NHS and care capacity, and put it on a sustainable footing. This includes ensuring staff are protected by the appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), in all NHS and care settings.

This has required a new Industrial Strategy for PPE. Since the start of the outbreak, the Government, working with the NHS, industry and the Armed Forces, has delivered over 1.16bn pieces of PPE to the front line. On 6 May, over 17 million PPE items were delivered to 258 trusts and organisations. Through its UK-wide approach, the Government is working closely with the devolved administrations to support and co-ordinate the distribution of PPE across the UK: millions of PPE items have been delivered to Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. But there remains much more to do and under the leadership of Lord Deighton, the Government will:

- Expand supply from overseas. The Government has already set up a cross-government PPE sourcing unit, now staffed by over 400 people, to secure new supply lines from across the world and has published rigorous standards against which purchases will be made. The Government is working urgently to identify new sources of critical PPE from overseas markets, diversifying the UK’s sources of supply and strengthening the UK’s supply chains for the long term. DIT and FCO teams in posts around the world are seeking new supplies, lobbying governments to lift export restrictions and helping get crucial deliveries back to the UK.

- Improve domestic manufacturing capability. Lord Deighton is leading the Government effort to unleash the potential of British industry to manufacture PPE for the health and social care sectors. This will build on the manufacturing opportunities the Government has already identified and contribute to the national effort to meet the unprecedented demand. The Government is also working to support the scale-up of engineering efforts for small companies capable of contributing to supplies. The Government is currently in contact with over 200 potential UK manufacturers and has already taken delivery of products from new, certified UK manufacturers.

- Expand and improve the logistics network for delivering to the front line. The Government has brought together the NHS, industry and the Armed Forces to create a huge PPE distribution network, providing drops of critical equipment to 58,000 healthcare settings including GPs, pharmacies and social care providers. The Government is also releasing stock to wholesalers for primary and social care and has delivered over 50 million items of PPE to local resilience forums to help them respond to urgent local demand. The Government is continually looking at how it improves distribution and is currently testing a new portal to more effectively deliver to smaller providers.

Second, the Government will seek innovative operating models for the UK’s health and care settings, to strengthen them for the long term and make them safer for patients and staff in a world where COVID-19 continues to be a risk. For example, this might include using more tele-medicine and remote monitoring to give patients hospital-level care from the comfort and safety of their own homes. Capacity in community care and step-down services will also be bolstered, to help ensure patients can be discharged from acute hospitals at the right time for them. To this end, the Government will establish a dedicated team to see how the NHS and health infrastructure can be supported for the COVID-19 recovery process and thereafter.

Third, recognising that underlying health conditions and obesity are risk factors not just for COVID-19 but also for other severe illnesses, the Government will invest in preventative and personalised solutions to ill-health, empowering individuals to live healthier and more active lives. This will involve expanding the infrastructure for active travel (cycling and walking) and expanding health screening services, especially through the NHS Health Check programme, which is currently under review.

Fourth, the Government remains committed to delivering its manifesto, including to building 40 new hospitals, reforming social care, recruiting and retaining 50,000 more nurses and creating 50 million new GP surgery appointments.

Finally, the Government will continue to bolster the UK’s social care sector, to ensure that those who need it can access the care they need outside of the NHS. The Government has committed to invest £1bn in social care every year of this Parliament to support the growing demand on the sector. By having an effective social care system the NHS can continue to discharge people efficiently from hospitals once they no longer need specialist medical support, helping us to keep NHS capacity available for those who need it most. The Government is also committed to longer term reform of the social care sector so no one is forced to have to sell their home to pay for care. Everyone accessing care must have safety and security.

Together these reforms will ensure that as well as preparing for the UK’s recovery from COVID-19, the Government learns the lessons from this outbreak and ensures that the NHS is resilient to any future outbreaks.

5.2 Protecting care homes

The Government’s number one priority for adult social care is infection control during the COVID-19 pandemic. Care homes for the elderly are particularly vulnerable because their residents are typically at greatest risk due to age and comorbidities and because the nature of care homes means they are often closed spaces where the virus can spread quickly. In April, the Government published a comprehensive action plan to support the 25,000 providers of adult social care in England throughout the COVID-19 outbreak, including ramping up testing, overhauling the way PPE is being delivered to care homes and helping to minimise the spread of the virus to keep people safe.[footnote 33]

This has been supported by £3.2bn of additional funding for local authorities, which can be used to meet some of the rising costs providers are facing and additional pressures on social care; as well as a further £1.3bn for the NHS and local authorities to work together to fund the additional needs of people leaving hospital during the pandemic.

While still too high, the daily number of deaths of people in care homes in England has been falling for the past fortnight. The majority of care homes still have been protected from having any cases and the Government will continue to strengthen the protections against infection of care home residents. Acting on the most recent scientific advice, the Government is taking further steps to support and work with the care home sector, building on work so far. This includes:

- Testing: the Government is providing widespread, swift testing of all symptomatic care home residents, and all patients discharged from hospital before going into care homes. It is offering a COVID-19 test to every staff member and resident in every care home in England, whether symptomatic or not; by 6 June, every care home for the over 65s will have been offered testing for residents and staff.

- Infection prevention and control: the Government is stepping in to support supply and distribution of PPE to the care sector, delivering essential supplies to care homes, hospices, residential rehabs and community care organisations. It is supporting care homes with extensive guidance, both online and by phone, on how to prevent and control COVID-19 outbreaks. This includes detailed instructions on how to deep clean effectively after outbreaks and how to enhance regular cleaning practices. The NHS has committed to providing a named contact to help ‘train the trainers’ for every care home that wants it by 15 May. The Government expects all care homes to restrict all routine and non-essential healthcare visits and reduce staff movement between homes, in order to limit the risk of further infection.

- Workforce: the Government is expanding the social care workforce, through a recruitment campaign, centrally paying for rapid induction training, making Disclosure and Barring Services checks free for those working in social care and developing an online training and job matching platform.

- Clinical support: the Government is accelerating the introduction of a new service of enhanced health support in care homes from GPs and community health services, including making sure every care home has a named clinician to support the clinical needs of their residents by 15 May. The NHS is supporting care homes to take up video consultation approaches, including options for a virtual ward.

- Guidance: the Government is providing a variety of guidance, including on GOV.UK and is signposting, through the Social Care Institute for Excellence, resources for care homes, including tailored advice for managing the COVID-19 pandemic in different social care settings and with groups with specific needs, for example adults with learning disabilities and autism.

- Local Authority role: every local authority will ensure that each care home in their area has access to the extra support on offer that they need to minimise the risk of infection and spread of infection within their care home, for example that care homes can access the face to face training on infection control offered by the NHS, that they have a named clinical lead, know how to access testing for their staff and residents and are aware of best practice guidance for caring for their residents during the pandemic. Any issues in accessing this support will be escalated to regional and national levels for resolution as necessary.

5.3 Smarter shielding of the most vulnerable

The Government is taking a cautious approach, but some inherent risk to the most vulnerable remains. Around 2.5 million people across the UK have been identified as being clinically extremely vulnerable and advised to shield.[footnote 34]

These are people who are most at risk of severe illness if they contract COVID-19. This means that they have been advised to stay at home at all times and avoid any face-to-face contact, until the end of June. The Government and local authorities have offered additional support to people who are shielding, including delivery of food and basic supplies, care, and support to access medicines, if they are unable to get help with this from family and friends. Over one million food boxes have been delivered in England since the programme started.[footnote 35] NHS Volunteer Responders and local volunteers are also helping to support this group.

The guidance on shielding and vulnerability will be kept under review as the UK moves through the phases of the Government’s strategy. It is likely that the Government will continue to advise people who are clinically extremely vulnerable to shield beyond June. Whilst shielding is important to protect individuals from the risk of COVID-19 infection, the Government recognises that it is challenging for people’s wider wellbeing. The Government will review carefully the effect on shielded individuals, the services they have had, and what next steps are appropriate.

For those who need to shield for a longer period, the Government will review the scale and scope of their needs and how the support programme can best meet these. The Government will also consider guidance for others who may be more vulnerable to COVID-19 and how it can support people to understand their risk.

5.4 More effective, risk-based targeting of protection measures

One way to limit the effect of the shielding measures and better target the social restrictions is to understand the risk levels in different parts of the population - both risk to self and risk to others.

It is clear the virus disproportionally affects older people, men, people who are overweight and people with some underlying health conditions. This is a complex issue, which is why, as set out in Chapter 1, Public Health England is leading an urgent review into factors affecting health outcomes.

In March, based on data and evidence available about the virus at that time, SAGE advised that older people, and those with certain underlying medical conditions, should take additional precautions to reduce the risk of contracting the virus. Those defined as clinically extremely vulnerable have been advised to shield, staying at home at all times and avoiding all non-essential face to face contact. Those who are clinically vulnerable, including all those aged 70 and over and pregnant women, have been advised to take particular care to minimise contact with those outside their household.

As our understanding of the virus increases, the Government is monitoring the emerging evidence and will continue to listen to advice from its medical advisers on the level of clinical risk to different groups of people associated with the virus. As the Government learns more, we expect to be able to offer more precise advice about who is at greatest risk. The current advice from the NHS on who is most at risk of harm from COVID-19 can be found here.[footnote 36]

5.5 Accurate disease monitoring and reactive measures

The success of any strategy based on releasing the current social restrictions while maintaining the epidemic at a manageable level will depend on the Government’s ability to monitor the pandemic accurately, as well as quickly detect and tackle a high proportion of outbreaks. This will be especially challenging during the winter months given that COVID-19 shares many symptoms with common colds and the flu. As the Government lifts restrictions over the coming months, the public must be confident action will be taken quickly to deal with any new local spikes in infections, and that nationally we have a clear picture of how the level of infections is changing. To achieve this, the Government is establishing a new biosecurity monitoring system, led by a new Joint Biosecurity Centre now being established.

Joint Biosecurity Centre (JBC)