Country policy and information note: Women fearing gender-based violence, Pakistan, November 2022 (accessible)

Updated 12 March 2025

Version 5.0

November 2022

Preface

Purpose

This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme.

It is split into 2 parts: (1) an assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below.

Assessment

This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note - that is information in the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw - by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies:

-

a person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm

-

that the general humanitarian situation is so severe that there are substantial grounds for believing that there is a real risk of serious harm because conditions amount to inhuman or degrading treatment as within paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)

-

that the security situation is such that there are substantial grounds for believing there is a real risk of serious harm because there exists a serious and individual threat to a civilian’s life or person by reason of indiscriminate violence in a situation of international or internal armed conflict as within paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules

-

a person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies)

-

a person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory

-

a claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and

-

if a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts.

Country of origin information

The country information in this note has been carefully selected in accordance with the general principles of COI research as set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), April 2008, and the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation’s (ACCORD), Researching Country Origin Information – Training Manual, 2013. Namely, taking into account the COI’s relevance, reliability, accuracy, balance, currency, transparency and traceability.

The structure and content of the country information section follows a terms of reference which sets out the general and specific topics relevant to this note.

All information included in the note was published or made publicly available on or before the ‘cut-off’ date(s) in the country information section. Any event taking place or report/article published after these date(s) is not included.

All information is publicly accessible or can be made publicly available. Sources and the information they provide are carefully considered before inclusion. Factors relevant to the assessment of the reliability of sources and information include:

-

the motivation, purpose, knowledge and experience of the source

-

how the information was obtained, including specific methodologies used

-

the currency and detail of information

-

whether the COI is consistent with and/or corroborated by other sources.

Multiple sourcing is used to ensure that the information is accurate and balanced, which is compared and contrasted where appropriate so that a comprehensive and up-to-date picture is provided of the issues relevant to this note at the time of publication.

The inclusion of a source is not, however, an endorsement of it or any view(s) expressed.

Each piece of information is referenced in a footnote. Full details of all sources cited and consulted in compiling the note are listed alphabetically in the bibliography.

Feedback

Our goal is to provide accurate, reliable and up-to-date COI and clear guidance. We welcome feedback on how to improve our products. If you would like to comment on this note, please email the Country Policy and Information Team.

Independent Advisory Group on Country Information

The Independent Advisory Group on Country Information (IAGCI) was set up in March 2009 by the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration to support him in reviewing the efficiency, effectiveness and consistency of approach of COI produced by the Home Office.

The IAGCI welcomes feedback on the Home Office’s COI material. It is not the function of the IAGCI to endorse any Home Office material, procedures or policy. The IAGCI may be contacted at:

Independent Advisory Group on Country Information

Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration

5th Floor

Globe House

89 Eccleston Square

London

SW1V 1PN

Email: chiefinspector@icibi.gov.uk

Information about the IAGCI’s work and a list of the documents which have been reviewed by the IAGCI can be found on the Independent Chief Inspector’s pages of the gov.uk website.

Assessment

Updated: 27 October 2022

1. Introduction

1.1 Basis of claim

1.1.1 Fear of persecution or serious harm from non-state actors because the person is a woman.

1.2 Points to note

1.2.1 Gender-based violence includes, but is not limited to, domestic abuse, sexual violence including rape, ‘honour crimes’, and women accused of committing adultery or having pre-marital relations.

1.2.2 Domestic abuse is not just about physical violence. It covers any incident or pattern of incidents of controlling, coercive, threatening behaviour, violence or abuse between those aged 16 or over who are, or have been, intimate partners or family members, regardless of gender or sexuality. It can include psychological, physical, sexual, economic or emotional abuse. Children can also be victims of, or witnesses to, domestic abuse. Anyone can experience domestic abuse, regardless of background, age, gender, sexuality, race or culture. However, to establish a claim for protection under the refugee convention or humanitarian protection rules, that abuse needs to reach a minimum level of severity to constitute persecution or serious harm.

1.2.3 For further guidance on assessing gender issues see the Asylum Guidance on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status and Gender issues in the asylum claim.

Official – sensitive: Start of section

1.3

1.3.1

1.3.2

1.3.3 The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

1.3.4

1.3.5

Official – sensitive: End of section

2. Consideration of issues

2.1 Credibility

2.1.1 For information on assessing credibility, see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

2.1.2 Decision makers must also check if there has been a previous application for a UK visa or another form of leave. Asylum applications matched to visas should be investigated prior to the asylum interview (see the Asylum Instruction on Visa Matches, Asylum Claims from UK Visa Applicants).

2.1.3 In cases where there are doubts surrounding a person’s claimed place of origin, decision makers should also consider the need to conduct language analysis testing (see the Asylum Instruction on Language Analysis).

Official – sensitive: Start of section

2.1.4

The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: End of section

2.2 Exclusion

2.2.1 Decision makers must consider whether there are serious reasons for considering whether one (or more) of the exclusion clauses is applicable. Each case must be considered on its individual facts and merits.

2.2.2 If the person is excluded from the Refugee Convention, they will also be excluded from a grant of humanitarian protection (which has a wider range of exclusions than refugee status).

2.2.3 For guidance on exclusion and restricted leave, see the Asylum Instruction on Exclusion under Articles 1F and 33(2) of the Refugee Convention, Humanitarian Protection and the instruction on Restricted Leave.

Official – sensitive: Start of section

The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: End of section

2.3 Convention reason(s)

2.3.1 Women in Pakistan form a particular social group (PSG) within the meaning of the Refugee Convention.

2.3.2 In Shah and Islam HL [1999] ImmAR283, promulgated 25 March 1999, the House of Lords held that women in Pakistan constituted a particular social group because they share the common immutable characteristic of gender, they were discriminated against as a group in matters of fundamental human rights and the State gave them no adequate protection because they were perceived as not being entitled to the same human rights as men.

2.3.3 Although the Constitution provides for equality of all citizens and numerous legislation has been enacted to protect women’s rights, deep-rooted social, cultural and economic barriers and prejudices remain, indicating that women continue to meet the definition of a PSG.

2.3.4 Although women form a PSG, establishing such membership is not sufficient to be recognised as a refugee. The question to be addressed is whether the person has a well-founded fear of persecution on account of their membership of such a group.

2.3.5 For further guidance on the 5 Refugee Convention grounds see the Asylum Instructions on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status and Gender issues in the asylum claim.

2.4 Risk

2.4.1 While some women face sexual and gender-based violence, predominantly from family members, in general, women are not at real risk of persecution or serious harm from non-state actors. Furthermore, the level of societal discrimination is not likely to be sufficiently serious by its nature and/or repetition, or by an accumulation of various measures, to amount to persecution or serious harm. Each case must be considered on its own merits with the onus on the person to demonstrate that they would be at real risk from non-state actors.

2.4.2 Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) and discrimination is prevalent, compounded by patriarchal attitudes and cultural norms, especially in rural areas amongst lower and middle classes. Sources, including Pakistan based NGOs, the Social Policy and Development Centre (SPDC) and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) note cases of violence against women are generally underreported, due to stigma and ‘victim blaming’ in society (see Sexual and gender-based violence – Overview).

2.4.3 A woman accused of adultery (zina) or sexual relations outside of marriage (fornication) may face prosecution. However no recent statistics or legal precedent of convictions could be found in the sources consulted (see Adultery and extra-marital relations).

2.4.4 In the country guidance case, KA and Others (domestic violence risk on return) Pakistan CG [2010] UKUT 216 (IAC), heard 21 and 22 April 2010, and promulgated 14 July 2010, which considered the case of a woman, whose husband had filed charges of adultery against her, the Upper Tribunal (UT) held that ‘In general persons who on return face prosecution in the Pakistan courts will not be at real risk of a flagrant denial of their right to a fair trial, although it will always be necessary to consider the particular circumstances of the individual case’ (headnote paragraph i).

2.4.5 In the country guidance case of SM (lone women - ostracism) (CG) [2016] UKUT 67 (IAC), heard on 21 May 2015 and promulgated 2 February 2016, the UT held that the existing country guidance in SN and HM (Divorced women - risk on return) Pakistan CG [2004] UKIAT 00283 and KA and Others (domestic violence risk on return) Pakistan CG [2010] UKUT 216 (IAC) remains valid (paragraph 73i).

2.4.6 In KA and Others the UT held that:

‘The Protection of Women (Criminal Laws Amendment) Act 2006 (“PWA”), one of a number of legislative measures undertaken to improve the situation of women in Pakistan in the past decade, has had a significant effect on the operation of the Pakistan criminal law as it affects women accused of adultery. It led to the release of 2,500 imprisoned women. Most sexual offences now have to be dealt with under the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC) rather than under the more punitive Offence of Zina (Enforcement of Hudood) Ordinance 1979. Husbands no longer have power to register a First Information Report (FIR) with the police alleging adultery; since 1 December 2006 any such complaint must be presented to a court which will require sufficient grounds to be shown for any charges to proceed. A senior police officer has to conduct the investigation. Offences of adultery (both zina liable to hadd and zina liable to tazir) have been made bailable…’ (headnote iii).

2.4.7 The UT held in SM (lone women - ostracism) that ‘Women in Pakistan are legally permitted to divorce their husbands and may institute divorce proceedings from the country of refuge, via a third party and with the help of lawyers in Pakistan, reducing the risk of family reprisals. A woman who does so and returns with a new partner or husband will have access to male protection and is unlikely, outside her home area, to be at risk of ostracism, still less of persecution or serious harm’ (paragraph 73 viii).

2.4.8 Domestic violence is widespread and usually committed by husbands, fathers, brothers and in-laws. Around a third of married women report having experienced spousal abuse (physical, sexual and/or emotional), Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) have the highest rates of reported intimate partner violence (IPV), according to the Georgetown University’s Women, Peace and Security Index 2021 (see Domestic violence).

2.4.9 The frequency of abuse is affected by various factors including where a woman lives (women living in rural areas are more at risk of all forms of gender-based violence than those in towns and cities), the age of which she married, her current age, marital status, her level of education and socio-economic status. Although domestic abuse is prevalent across society and affects women at all stages of their lives, women under 40 years old, married before the age of 18, without tertiary education and who live in rural areas, are the most vulnerable (see Sexual and gender-based violence – Overview and Domestic violence).

2.4.10 ‘Honour’ crimes, including murder, where the perpetrators seek to avenge the dishonour brought upon the family, are committed against some women accused of adultery, sexual relations outside of marriage, marrying without parental consent (love marriage) or because their dress or behaviour is deemed immodest. An allegation or suspicion of so-called sexual misconduct can be enough to perpetrate an ‘honour’ crime (see Adultery and extra-marital relations, ‘Honour’ crimes and Love marriage).

2.4.11 In KA and Others the UT held that ‘Whether a woman on return faces a real risk of an honour killing will depend on the particular circumstances; however, in general such a risk is likely to be confined to tribal areas such as the North West Frontier Province [now known as Khyber Pakhtunkhwa – KPK] and is unlikely to impact on married women’ (headnote paragraph iv).

2.4.12 More recent country information indicates that the risk of ‘honour’ killing is not restricted to tribal areas or unmarried women, however its prevalence is difficult to quantify as available statistics vary and crimes may be underreported.

2.4.13 According to media reports and Human Rights Watch (HRW), based on information from at least 2006, there were an estimated 1,000 ‘honour’ killings each year across the country, however it is not clear how these figures were obtained and official statistics are less than half that figure (see ‘Honour’ crimes).

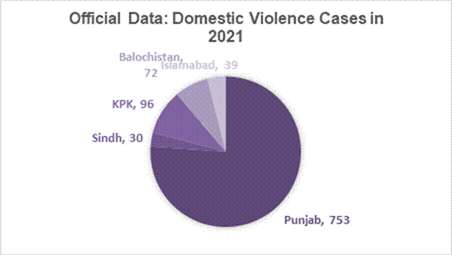

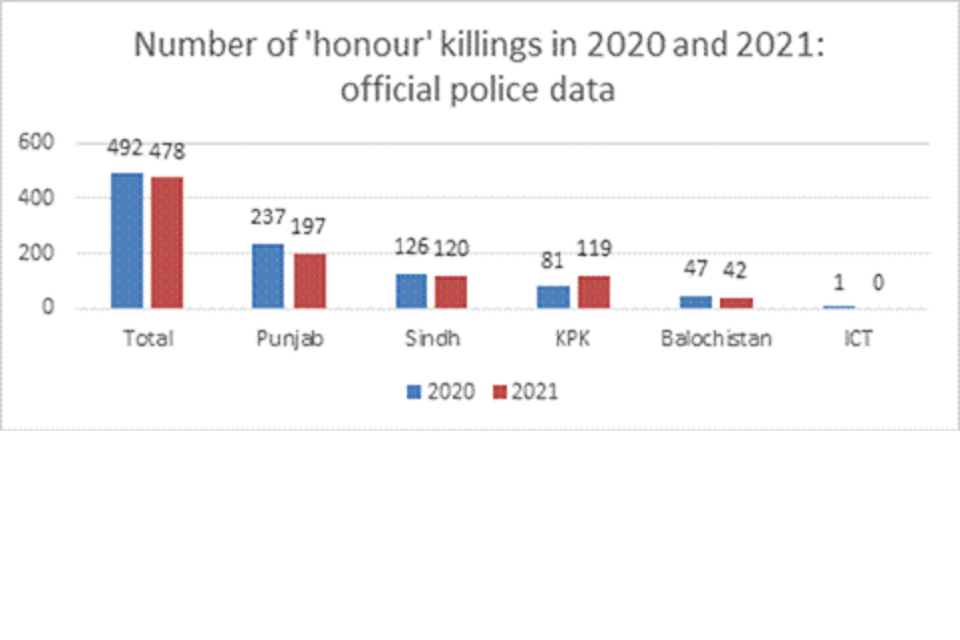

2.4.14 Based on official police statistics (not broken down by gender or sex, so may include men), the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) recorded 492 ‘honour’ killings in 2020 and 478 in 2021. Also citing official statistics, the Sustainable Social Development Organisation (SSDO) recorded 381 ‘honour’ killings in 2021. The highest rates are recorded in Punjab, followed by Sindh, KPK and Balochistan. They are reported to be more common in rural areas (see ‘Honour’ crimes).

2.4.15 The HRCP also considered media reporting of ‘honour’ crimes and noted discrepancies in its 2020 data, between reported cases and police statistics, were due to either a reluctance to report crimes, or that not all cases were reported by the media. However, both HRCP and SSDO consistently note lower or no reported incidences of ‘honour’ crimes in the Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT) in 2020 and 2021 (see ‘Honour’ crimes).

2.4.16 For further guidance on assessing risk, see the Asylum Instructions on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status and Gender issues in the asylum claim.

2.5 Protection

2.5.1 Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution from the state they will not, in general, be able to obtain protection from the authorities.

2.5.2 Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution from non-state actors, including ‘rogue’ state actors, the state is, in general, willing and able to provide effective protection. A person’s reluctance to seek protection does not mean that effective protection is not available. Any past persecution and past lack of effective protection may indicate that effective protection would not be available in the future. Each case must be considered on its own merits, with the onus on the person to demonstrate that protection is not available.

2.5.3 The Constitution prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex and there is a substantial body of legislation aimed at protecting the rights of women and countering violence against women. However, the implementation of some laws, which are aimed at preventing and punishing violence against women and girls, are not always effectively enforced (see Legal context and Implementation and enforcement of laws protecting women).

2.5.4 Pakistan has a functioning criminal justice system and, as of 30 November 2020, 193 courts across the country were designated to adjudicate GBV cases. Women police officers work throughout Pakistan and are posted at most police stations in Punjab and at some in Sindh and the Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT). Where women police officers are not available, all women-specific cases are referred to the Women and Child Protection Cells (see Representation of women in the justice system and Access to justice).

2.5.5 The police are sometimes unwilling to register or investigate domestic violence cases, viewing them as family problems or not serious crimes, and instead encourage reconciliation. Some police demand bribes before registering cases and investigations are often superficial (see Access to justice and Treatment by, and attitudes of, the police and judiciary).

2.5.6 Informal justice systems lack formal legal protections but continue to be used in rural areas and pass harsh punishments to women, including ‘honour’ killings or giving girls in marriage as a form of compensation (swara) (see Informal justice systems).

2.5.7 Referring to pre-existing caselaw, in the country guidance case KA and Others the UT held that:

‘The guidance given in SN and HM (Divorced women – risk on return) Pakistan CG 2004 UKIAT 00283 and FS (Domestic violence – SN and HM – OGN) Pakistan CG 2006 UKIAT 00023 remains valid. The network of women’s shelters (comprising government-run shelters (Darul Amans) and private and Islamic women’s crisis centres) in general affords effective protection for women victims of domestic violence, although there are significant shortcomings in the level of services and treatment of inmates in some such centres. Women with boys over 5 face separation from their sons’ (headnote paragraph vi).

2.5.8 The UT held in SM (lone women - ostracism) that the existing country guidance in SN and HM (Divorced women - risk on return) Pakistan CG [2004] UKIAT 00283 and KA and Others (domestic violence risk on return) Pakistan CG [2010] UKUT 216 (IAC) remains valid (paragraph 73i).

2.5.9 In the CG case of SM (lone women - ostracism), the UT held that:

‘A single woman or female head of household who has no male protector or social network may be able to use the state domestic violence shelters for a short time, but the focus of such shelters is on reconciling people with their family networks, and places are in short supply and time limited. Privately run shelters may be more flexible, providing longer term support while the woman regularises her social situation, but again, places are limited.

‘Domestic violence shelters are available for women at risk but where they are used by women with children, such shelters do not always allow older children to enter and stay with their mothers. The risk of temporary separation, and the proportionality of such separation, is likely to differ depending on the age and sex of a woman’s children: male children may be removed from their mothers at the age of 5 and placed in an orphanage or a madrasa until the family situation has been regularised (see KA and Others…). Such temporary separation will not always be disproportionate or unduly harsh: that is a question of fact in each case’ (paragraph 73 vi to vii).

2.5.10 Women who face GBV may obtain support and assistance in government-run shelter homes (Darul Amans) in all provinces, through privately-run women’s crisis centres, and in public-private partnership shelters. Support may include legal aid, medical treatment, and psychosocial counselling and provisions in Punjab are generally better than in other provinces. However, some Darul Amans lack sufficient space, staff, and resources and the US Department of State reported that some staff abused or discriminated against the shelter residents, severely restricted their movement or pressured them to return to their abusers (see Crisis centres, shelters and helplines).

2.5.11 Since SM (lone women - ostracism) was heard, the situation in regard to shelters has not significantly changed. There are not, therefore, ‘very strong grounds supported by cogent evidence’ to justify a departure from SM.

2.5.12 For further guidance on assessing state protection, see the Country Policy and Information Note Pakistan: Actors of protection, and the Asylum Instructions on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status and Gender issues in the asylum claim.

2.6 Internal relocation

2.6.1 Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution or serious harm from the state, they are unlikely to be able to relocate to escape that risk.

2.6.2 Internal relocation may be reasonable to large urban centres such as Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad. Each case must be considered on its own merits, having regard to the individual circumstances of the person.

2.6.3 The UT held in SM (lone women - ostracism) that the existing country guidance in SN and HM (Divorced women - risk on return) Pakistan CG [2004] UKIAT 00283 and KA and Others (domestic violence risk on return) Pakistan CG [2010] UKUT 216 (IAC) remains valid (paragraph 73i).

2.6.4 In the country guidance case SN & HM (Divorced women– risk on return) Pakistan, heard 19 April 2004 and promulgated 25 May 2004, the UT held that the question of internal flight will require careful consideration in each case. The UT held (at paragraph 48 of the determination) that ‘The general questions which [decision makers] should ask themselves in cases of this kind are as follows:

a) Has the claimant shown a real risk or reasonable likelihood of continuing hostility from her husband (or former husband) or his family members, such as to raise a real risk of serious harm in her former home area?

b) If yes, has she shown that she would have no effective protection in her home area against such a risk, including protection available from the Pakistani state, from her own family members, or from a current partner or his family?

c) If yes, would such a risk and lack of protection extend to any other part of Pakistan to which she could reasonably be expected to go (Robinson [1977] EWCA Civ 2089 AE and FE [2002] UKIAT 036361), having regard to the available state support, shelters, crisis centres, and family members or friends in other parts of Pakistan?’

2.6.5 In the country guidance case SM (lone women - ostracism), the UT held that:

‘Where a risk of persecution or serious harm exists in her home area for a single woman or a female head of household, there may be an internal relocation option to one of Pakistan’s larger cities, depending on the family, social and educational situation of the woman in question.

‘It will not normally be unduly harsh to expect a single woman or female head of household to relocate internally within Pakistan if she can access support from family members or a male guardian in the place of relocation.

‘It will not normally be unduly harsh for educated, better off, or older women to seek internal relocation to a city. It helps if a woman has qualifications enabling her to get well-paid employment and pay for accommodation and childcare if required.

‘Where a single woman, with or without children, is ostracised by family members and other sources of possible social support because she is in an irregular situation, internal relocation will be more difficult and whether it is unduly harsh will be a question of fact in each case’ (paragraph 73 (ii to v).

2.6.6 The UT in the case of KA and others held that ‘In assessing whether women victims of domestic violence have a viable internal relocation alternative, regard must be had not only to the availability of such shelters/centres but also to the situation women will face after they leave such centres’ (headnote paragraph vii).

2.6.7 The Islamabad-based NGO Rozan stated that after leaving a shelter, some women face social stigma, family rejection, financial constraints and practical challenges of living such as safe housing (see Single women).

2.6.8 Since SM (lone women - ostracism) was heard, the situation in regard to shelters has not significantly changed. There are not, therefore, ‘very strong grounds supported by cogent evidence’ to justify a departure from SM. See the section on Protection for caselaw and information regarding shelters.

2.6.9 For further guidance on considering internal relocation and factors to be taken into account see the see the Country Policy and Information Note Pakistan: Background information, including internal relocation, and the Asylum Instructions on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status and Gender issues in the asylum claim.

2.7 Certification

2.7.1 Where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

2.7.2 For further guidance on certification, see Certification of Protection and Human Rights claims under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 (clearly unfounded claims).

Country information

This section was updated on 21 September 2022

3. Legal context

3.1 Constitution

3.1.1 The Constitution provides for equality of citizens and states:

(1) All citizens are equal before law and are entitled to equal protection of law.

(2) There shall be no discrimination on the basis of sex.

(3) Nothing in this Article shall prevent the State from making any special provision for the protection of women and children[footnote 1].

3.2 Statutory provisions

3.2.1 The National Commission on the Status of Women (NCSW), a financial and administrative autonomous body established in 2012 to ‘examine and review laws, policies, programmes and monitor the implementation of laws for the protection and empowerment of women, and to facilitate the government in the implementation of international instruments and obligations’[footnote 2], provided a list of Federal and Provincial ‘Pro-Women’ laws, which included legislation aimed at protecting women against rape (though not marital rape[footnote 3]), ‘honour’ crimes, domestic violence, child marriage, acid attacks and harassment in the workplace, as well as laws ensuring rights in regard to marriage, reproduction, property and employment[footnote 4]. The NCSW noted ‘Many of the federal laws are constitutionally applicable to the provinces as well, until a provincial government enacts its own law …’[footnote 5]

3.2.2 For legislation relating to sexual and gender-based violence, see the relevant sections within this note.

3.2.3 The Women, Peace and Security Index 2021 (2021 WPS Index), building on data from 2020 and 2021, prepared by Georgetown University’s Institute for Women, Peace and Security (GIWPS) and the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), an independent research institution, which measures women’s inclusion (economic, social, political), justice (formal laws and informal discrimination), and security (at the individual, community, and societal levels)[footnote 6], noted that:

‘Pakistan has adopted several key international commitments to women’s rights, including the Beijing Platform for Action, the 1996 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, and the Sustainable Development Goals. Federal and provincial governments have gradually legislated legal reforms, most notably the Women’s Protection Bill (2006) and the 2016 Criminal Law Act outlawing rape. While those steps are important, implementation remains weak, and Pakistani women’s rights advocates face continuing opposition from political and religious forces.’[footnote 7]

3.3 Marriage, divorce, custody and inheritance rights

3.3.1 The Muslim Family Laws Ordinance, 1961, which regulates marriage, polygamy, divorce and maintenance, states that ‘It extends to [the] whole of Pakistan, and applies to all Muslim citizens of Pakistan, wherever they may be.’[footnote 8]

3.3.2 The Child Marriage Restraint Act, 1929, proscribes the minimum age of marriage for girls as 16 years old and 18 years for boys[footnote 9]. Although passed by the Senate in April 2019[footnote 10], at the time of writing, proposed amendments to the Act to raise the marriage age for girls to 18 remained pending with the Council of Islamic Ideology (CII), an advisory body who opine whether a law is or is not repugnant to the rules of Islam[footnote 11], following objections that the changes were contrary to Islam[footnote 12]. The Provincial Assembly of Sindh (PAS) passed the Sindh Child Marriage Restraint Act in April 2014, which repealed the 1929 Act and prohibits marriage for boys and girls under the age of 18 years[footnote 13].

See also Child and forced marriage.

3.3.3 The US Department of State noted in its human rights report for 2021 (USSD HR Report 2021) that ‘The 2017 Hindu Marriage Law gives legal validity to Hindu marriages, including registration and official documentation, and outlines conditions for separation and divorce, including provisions for the financial security of wives and children.’[footnote 14]

3.3.4 The USSD 2021 International Religious Freedom (USSD 2021 IRF) report noted that the Hindu Marriage Act applied to federal territory and all other provinces. The same source also cited the provincial-level Sindh Hindu Marriage Act, which legitimises Hindu marriages and applies to Sikhs[footnote 15].

3.3.5 The USSD IRF 2021 report added ‘The Punjab Sikh Anand Karaj Marriage Act allows local government officials in that province to register marriages between a Sikh man and Sikh woman solemnized by a Sikh Anand Karaj marriage registrar.’[footnote 16]

3.3.6 Regarding religious conversion and its effect on marriage, the USSD 2021 IRF report noted that ‘Some court judgments have considered the marriage of a non-Muslim woman to a non-Muslim man dissolved if she converts to Islam, although the marriage of a non-Muslim man who converts remains recognized.’[footnote 17]

3.3.7 The Christian Marriage and Divorce Bill 2019, which aimed to update the old laws, including to allow greater scope for divorce[footnote 18] [footnote 19], remained pending at the time of writing.

3.3.8 The Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act 1939 lays down the grounds on which a woman may divorce her husband[footnote 20]. Article 29 of the 2006 Protection of Women Act amended the Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act by providing further grounds for divorce, namely ‘lian’, explained as ‘… where the husband has accused his wife of zina [sex outside of marriage] and the wife does not accept the accusation as true.’[footnote 21]

3.3.9 The USSD HR Report 2021 noted that ‘Family law provides protection for women in cases of divorce, including requirements for maintenance, and sets clear guidelines for custody of minor children and their maintenance. Many women were unaware of these legal protections or were unable to obtain legal counsel to enforce them. Divorced women often were left with no means of support, as their families ostracized them.’[footnote 22]

3.3.10 In regard to inheritance, the same report said:

‘The law entitles female children to one-half the inheritance of male children. Wives inherit one-eighth of their husbands’ estates. Women often received far less than their legal entitlement. In addition, complicated family disputes and the costs and time of lengthy court procedures reportedly discouraged women from pursuing legal challenges to inheritance discrimination. During the year Khyber Pakhtunkhwa passed a law for the protection of women’s inheritance rights and appointed a female independent ombudsperson charged with hearing complaints, starting investigations, and making referrals for enforcement of inheritance rights.’[footnote 23]

This section was updated on 21 September 2022

4. Socio-economic indicators

4.1 Global and provincial equality / inclusivity ranking

4.1.1 The World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index for 2021 ranked Pakistan 153 out of 156 countries (with the country first having the smallest gender gap, 156th the widest) in terms of women’s economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment[footnote 24]. The Index also ranked Pakistan second worst in South Asia, above Afghanistan and below India[footnote 25]. In 2020, the Global Gender Gap Index ranked Pakistan last in South Asia, although that year did not include Afghanistan in its rankings[footnote 26].

4.1.2 Pakistan ranked 167 out of 170 countries in the Georgetown Institute’s 2021 WPS Index (with the country ranked first demonstrating the highest levels of inclusion, justice and security for women, 170th the least)[footnote 27] [footnote 28]. The 2021 WPS Index noted that, ‘Between 2017 and 2021, Pakistan regressed on two measures of inclusion – women’s mean years of schooling and rates of paid employment.’[footnote 29]

4.1.3 In terms of gender equality, the UN Development Programme (UNDP) Gender Inequality Index (GII), which measures gender-based disadvantage in terms of reproductive health, empowerment and the labour market, ranging from 0, where women and men fare equally, to 1, where one gender fares as poorly as possible in all measured dimensions, showed Pakistan’s progress since 1990 (when it measured 0.811), up to 2020 (when it measured 0.534), bringing the country closer to the world average of 0.465[footnote 30].

4.1.4 Profiling Pakistan’s provinces, the 2021 WPS Index stated that:

‘Punjab scored above the national average on inclusion, justice, and security, traceable in part to high rates of urbanization. The province had the fewest deaths due to organized violence, around a quarter of the national average, but was still marked by political violence, including riots, protests, and attacks by militant groups. Punjab had a largely agrarian economy with economic stagnation in more rural areas along with high, and worsening, income inequality traced to urbanization.

‘Sindh performed around the national average on women’s education and discriminatory norms, but below average on employment, intimate partner violence, and organized violence. Sindh had the highest levels nationally of women’s financial inclusion, at 25 percent, and participation in household decision making, at 46 percent. But urban–rural differences were stark, with 15 percent of urban women completing secondary education, compared with only 2 percent of rural women.

‘Urban inequalities are also prevalent in Sindh. Karachi, Pakistan’s largest city and financial capital, hosts some of South Asia’s largest slums and informal settlements. Despite substantial income from wages and salaries and from property, Karachi has experienced recurrent waves of ethnopolitical, sectarian, and militant violence.

‘KPK and Balochistan scored poorly on virtually all the indicators in our provincial WPS Index. In KPK, women’s employment stood at 12 percent, financial inclusion at 17 percent, cellphone use at 37 percent, and participation in domestic decision making at 19 percent. Balochistan, bottom ranked of the provinces, experienced extensive deficits in women’s social and economic inclusion: women’s employment was a meager 8 percent, financial inclusion was 13 percent, and cellphone use was 16 precent. Balochistan also scored poorly on women’s participation in decision making (10 percent) and had a high level of son bias – approximately 111 boys were born for every 100 girls, similar to the world’s three highest country rates (Azerbaijan, China, and Viet Nam). Only 5 percent of girls in KPK and 4 percent in Balochistan completed secondary education.’[footnote 31]

4.2 Education and literacy

4.2.1 The USSD HR Report 2021 noted that ‘The constitution mandates compulsory education, provided free of charge by the government, to all children between ages five and 16. Despite this provision, government schools often charged parents for books, uniforms, and other materials.’[footnote 32]

4.2.2 According to the Global Gender Gap Index for 2021, 46.5% of women are literate, 61.6% attend primary school, 34.2% attend high school and 8.3% are enrolled in tertiary [higher] education courses, compared to 71.1%. 73.2%, 40.4% and 9.6% of men, respectively[footnote 33].

4.2.3 The 2021 WPS Index noted that, ‘On average, girls had much less access to education in Pakistan than boys – mean years of schooling was 3.9 for women and 6.4 for men. Only in Punjab did even half of women (52 percent) complete at least primary school, and rates were as low as 19 percent in Balochistan and 30 percent in KPK. In all provinces, 10 percent or less of women have completed secondary school.’[footnote 34]

4.2.4 A press release dated February 2022, published by the Malala Fund, a non-governmental organisation (NGO) advocating for girls’ education, noted that ‘Pakistan has made a lot of progress for girls’ education in the last decade — but 12 million girls remain out of school, with only 13% of girls reaching grade nine [age 13 to 14].’[footnote 35]

4.2.5 The USSD HR Report 2021 stated:

‘The most significant barrier to girls’ education was lack of access. Public schools, particularly beyond the primary grades, were not available in many rural areas, and those that existed were often too far for a girl to travel unaccompanied under prevailing social norms. Despite cultural beliefs that boys and girls should be educated separately after primary school, the government often failed to take measures to provide separate restroom facilities or separate classrooms, and there were more government schools for boys than for girls. The attendance rates for girls in primary, secondary, and postsecondary schools were lower than for boys. Additionally, certain tribal and cultural beliefs often prevented girls from attending schools.’[footnote 36]

4.3 Employment and income

4.3.1 The Global Gender Gap Index for 2021 noted that ‘Few women participate in the labour force (22.6%) and even fewer are in managerial positions (4.9%)… on average, a Pakistani woman’s income is 16.3% of a man’s.’[footnote 37]

4.3.2 A blog published in June 2021 by the World Bank stated, ‘Having hovered around 10 percent for over 20 years, female labor force participation (FLFP) in urban Pakistan is among the lowest in the world.’[footnote 38]

4.3.3 The 2021 WPS Index stated:

‘Performance on inclusion [in employment] was alarmingly low across Pakistan’s provinces. Rates of female employment hovered around 10 percent in Balochistan, KPK and Sindh, which would rank those provinces with the world’s bottom four countries on the global WPS Index. Agriculture was the country’s largest source of employment, but women in agriculture were more likely than men to be unpaid family workers and unprotected by labor laws in any province but Sindh.’[footnote 39]

4.3.4 According to the Pakistan Government’s Bureau of Statistics (PBS) Labour Force Survey, 2020 to 2021, male participation in the labour force, which stood at 67.9%, was ‘… more than three times than female participation rate (21.3%).’[footnote 40]

4.4 Political participation and representation

4.4.1 Women are reserved 60 seats in the National Assembly (NA) and, as of June 2022, the total number of female parliamentarians who held seats in the NA was 70, equating to 20.47% of the total number (342) of NA members[footnote 41] [footnote 42]. In the Senate, 17 seats out of 100 are reserved for women[footnote 43].

4.4.2 The Global Gender Gap Index for 2021 noted that ‘… women’s representation among parliamentarians (20.2%) and ministers (10.7%) remains low.’[footnote 44]

4.4.3 The 2021 WPS Index stated ‘Although women have been active in Pakistani politics since independence, their formal parliamentary representation remains limited. Almost two decades ago, President Pervez Musharraf introduced a 17 percent quota for women in national and provincial assemblies. Current women’s parliamentary representation in provincial assemblies ranges between 17 and 20 percent, just meeting the modest quota.’[footnote 45]

4.4.4 The USSD HR Report 2021 noted, ‘Authorities reserved for women 132 of the 779 seats in provincial assemblies and one-third of the seats on local councils. Women participated actively as political party members, but they were not always successful in securing leadership positions within parties, apart from women’s wings. Of 48 members of the federal cabinet, only five were women.’[footnote 46]

4.4.5 The same report added that ‘Women’s political participation was affected by cultural barriers to voting and limited representation in policymaking and governance. According to an August survey by the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, female legislators reported that discriminatory cultural norms and stereotypes hindered their entry into politics and impacted their performance as members of legislative assemblies.’[footnote 47]

4.4.6 The Elections Act 2017 states that if less than 10% of women vote in any constituency, the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) may presume that the women’s vote was suppressed, and the results for that constituency or polling station may be declared void[footnote 48].

4.4.7 In regard to the minimum 10% turn out of women, the USSD HR Report 2021 noted, ‘The government enforced the law for the first time in Shangla, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, when the Election Commission canceled the district’s 2018 general election results after women made up less than 10 percent of the vote.’[footnote 49] The same source added, ‘Cultural and traditional barriers in tribal and rural areas impeded some women from voting.’[footnote 50]

4.5 Healthcare and reproductive rights

4.5.1 A joint NGO report submitted for consideration by the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (UN CEDAW) by the women’s rights group, Shirkat Gah, dated 10 June 2019, noted that social norms in Pakistan restrict women’s access to health services, especially in regard to reproductive health. The report referred to the Reproductive Healthcare and Rights Act (2013), noting that the services offered within this Act were restricted to married couples only, excluding the rights to health of unmarried women and adolescent girls[footnote 51].

4.5.2 The Pakistan Maternal Mortality Survey 2019 (PMMS 2019), conducted by the National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS), estimated that the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) – defined as any death (excluding those that occurred due to accidents or violence) that occurred during pregnancy or childbirth or within 42 days after the birth or termination of a pregnancy – was 186 deaths per 100,000 live births. The ratio was 26% higher in rural areas than in urban areas[footnote 52].

4.5.3 The Pakistan Penal Code permits abortion when the life of a woman is in danger by continuing with the pregnancy or the woman is required to undergo treatment. Causing abortion or miscarriage outside of these permissions is known as Isqat-i-Hamal and may be subject to imprisonment[footnote 53].

4.5.4 According to the 10 June 2019 report submitted to UN CEDAW by Shirkat Gah, as a form of family planning, women took unauthorised routes to terminate their pregnancies, namely unsafe abortion services. The report noted that the reasons for the terminations included family limitations, myths and misconceptions, socio-cultural attitudes, and low rates of adoption of family planning techniques and procedures[footnote 54].

4.5.5 The UN CEDAW in its concluding observations on the fifth periodic report of Pakistan, dated 10 March 2020, expressed concern at:

‘(a) The high maternal mortality rate in the State party;

‘(b) Women’s limited access to family planning services, including modern contraceptives;

‘(c) Restrictive abortion laws and the large number of women resorting to unsafe abortions, as well as the lack of adequate post-abortion care services;

‘(d) The high incidence of obstetric fistula [a childbirth injury] in the State party, resulting from prolonged obstructed labour in the absence of skilled birth attendance, as well as iatrogenic fistula, resulting from surgical negligence during caesarean section or hysterectomy;

‘(e) The subjection of women with disabilities, in particular those living in institutions, to forced sterilization, and the performance of gender reassignment surgery on intersex persons for the purpose of legal gender recognition and victims’ limited access to justice.’[footnote 55]

4.5.6 On 17 March 2022, English-language daily news site, Dawn, reported on a forum on women’s health that drew attention to ‘… the impediments that led to growing disparity in healthcare and prevented women from seeking diagnoses…’. The panel groups at the forum, led by women, raised the need for ‘Comprehensive policies, opportunistic screening, culturally-relevant measures and universal healthcare… needed to improve Pakistani women’s access to healthcare and thereby improving their quality of life…’ The report added that, in a discussion on gender inequalities in accessing healthcare, particularly in regard to women who relied on male relatives to take them to hospital, one expert said ‘Women can make choices for their children’s health and can go to a doctor if a child is ill. However, they do not have the agency to go to a doctor for their own health.’[footnote 56]

This section was updated on 21 September 2022

5. Position of women in society

5.1 Demography

5.1.1 Using 2020 estimates, the CIA World Factbook provided a breakdown, by sex and age, of the total population:

-

0-14 years: (male 42,923,925/female 41,149,694)

-

15-24 years: (male 23,119,205/female 21,952,976)

-

25-54 years: (male 41,589,381/female 39,442,046)

-

55-64 years: (male 6,526,656/female 6,423,993)

-

65 years and over: (male 4,802,165/female 5,570,595)[footnote 57].

5.1.2 The majority of women (and the rest of the population[footnote 58]) live in rural areas[footnote 59].

5.2 Cultural, societal and family attitudes

5.2.1 The status of women differs in terms of their class, religion, education, economic independence, region and location (urban or rural), cultural and traditional values, caste, educational profile, marital status and number of children[footnote 60] [footnote 61]. However, patriarchal attitudes and discriminatory stereotypes about women’s roles and responsibilities in the family and in society, worsened by religious divisions in government, maintain their subordination to men[footnote 62] [footnote 63].

5.2.2 A Thomson Reuters Foundation survey, dated 2018, consisting of 550 experts on women’s issues, ranked Pakistan as the ‘… sixth most dangerous and fourth worst [country in the world for women] in terms of economic resources and discrimination as well as the risks women face from cultural, religious and traditional practices, including so-called honor killings. Pakistan ranked fifth on non-sexual violence, including domestic abuse.’[footnote 64]

5.2.3 The Shirkat Gah (women’s rights group) report on the impact of COVID-19 on women, dated December 2020, noted that ‘Of paramount concern is the normalisation of domestic violence: a quarter of women in Punjab, half of those in Sindh and three-quarters of women in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa believe that a husband beating his wife is justified for various reasons.’[footnote 65]

5.2.4 The Georgetown Institute’s 2017/18 WPS Index used a measure for discriminatory norms, derived from the Gallup World Poll that asked respondents whether ‘it is perfectly acceptable for any woman in your family to have a paid job outside the home if she wants one.’ In Pakistan, 73% of men disagreed with this proposition[footnote 66].

5.2.5 In a household survey using data collected in February 2021 from a sample size of 852 male and 179 female respondents, the Center for Global Development (CGD) found that 43% of men think women should not work outside the home and, although half of men thought women should be allowed to work, 28% of those did not think a woman could do the same job as a man. The CGD also cited the 2019 Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement (PSLM) survey, in which it was found that 40% of women needed permission from a family member to seek or remain in paid employment[footnote 67].

5.2.6 In November 2018, Zohra Yusuf, the former chairperson of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), told German broadcaster Deutsche Welle (DW) that ‘“Feudal orthodoxy and conservative norms have deep roots in Pakistan. Men want to control women and they treat them as their “property”. They don’t allow any freedom to women”.’[footnote 68]

5.2.7 The CDG noted in 2021 that ‘An important driver of gender gaps are gender norms. In Pakistan, men are generally expected to be breadwinners and women are generally expected to stay home. This leads to higher demand for school for sons than for daughters.’[footnote 69]

5.2.8 The Australian Government’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) January 2022 Country Information Report, informed by DFAT’s on-the-ground knowledge and discussions with a range of sources in Pakistan and elsewhere, as well as information from government, non-government and media sources[footnote 70], noted that:

‘Women’s participation in society in Pakistan can be heavily curtailed depending on their social circumstances. Observation of the purdah (literally “curtain”, an Islamic practice of segregating women from unrelated men) restricts many women’s personal, social and economic activities outside the home. While women in cities such as Lahore, Karachi and Islamabad often enjoy relative freedom, conservative rural communities are much stricter. There are reports of widespread sexual harassment of women and girls in public places, schools and universities. Some, mostly wealthy, Pakistani women have attained senior positions in public life, but their experience is not representative of the general population.’[footnote 71]

5.3 Single women

5.3.1 According to the most recent Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey (PDHS) 2017-18, implemented by the National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) and published January 2019, 62% of Pakistani women between the ages of 15 and 49 stated that they were married. The corresponding proportion for men was 50%. In the same survey, only 1.9% of women and 2.1% of men in the age group 45 to 49 said that they had never been married[footnote 72].

5.3.2 Information on the general situation for single women was limited.

5.3.3 The testimonies of 8 single women who discussed the pressures they had from both family and friends to get married and have children were cited in March 2019 by Dawn[footnote 73]. In April 2021 Dawn published an article by lawyer Rafia Zakaria about the social expectation that women get married. She also said that although it was possible for women to live alone, doing so was considered as a sign of dishonour for their families because it implied that the men were unwilling or unable to care for their female relatives, or that they were morally problematic for living away from the family home[footnote 74].

5.3.4 A study on ‘singlehood’, based on interviews with 20 single women over the age of 35 in Rawalpindi, Punjab, published in March 2021 noted:

‘Marriage has always been central to women’s lives in Pakistan and to remain single is not only considered socially unacceptable but also perceived as non-compliance to the cultural hegemony of the institute of marriage. Pakistan is a country where marriage is considered mandatory and singlehood is viewed as anomalous particularly in the case of women… Regardless of whether the causes for their single status were circumstantial or optional, unmarried women experience criticism, disgrace, loneliness, and feeling of being left out in a patriarchal societal setup where traditional gender role expectations bound women with marriage and motherhood.’[footnote 75]

5.3.5 According to an August 2021 article on the situation for single women, by Lahore-based journalist and writer, Nushmiya Sukhera:

‘There seems to be no space in Pakistani culture for women living alone. The common and expected arc of a woman’s life consists of first living in her parents’ home and moving out only when moving into the home of her husband and his family. Women who seek independence are often thought to be bringing shame upon the family by doing so and are severely criticized by relatives – close and distant alike. But in recent years, the country has seen a change in which more women are choosing to live independently, whether it’s by relocating to a different city for work, leaving abusive domestic situations, or even simply wanting to dip their toes in some form of liberation in a country determined to shackle them in one way or another. However, for most of these women, the decision to live independently brings with it its own set of challenges. They often have to put themselves in potentially dangerous situations in order to live a life devoid of control and confinement.’[footnote 76]

5.3.6 The same report noted that ‘According to Mazhar Lodhi, a real estate agent based in Islamabad, finding places for women is fairly easy. “They can find accommodations in hostels, apartments and even portions or rooms in houses,” he said.’ Similarly, Nayab Gohar Jan, an activist based in Lahore, said that there were ‘hostels accommodating single women…’ Despite this, Sukhera heard from women who had lived or were living independently, some of whom spoke of their personal security concerns as well as the moral policing and harassment they faced from landlords or male neighbours[footnote 77].

5.3.7 Lawyer Rafia Zakaria stated in an article published by Dawn in January 2022 that ‘Grown women who are not under the wing of a husband are automatically considered social pariahs and their morals declared compromised. Even in 2022, it is difficult for a single woman to rent or lease a home in many areas in the country. Faced with such realities, most girls just say “yes” [to marriage].’[footnote 78]

5.3.8 A research study on post-shelter lives of women survivors of violence by Rozan, an Islamabad-based NGO, published November 2018, noted that:

‘Depending upon the trajectory of their post shelter lives, many [women] still face violence or the threat of violence, severe stigma for living without male members or as a divorced woman as well as considerable distress as consequence of years of abuse and loss of support from family members. Many also face financial constraints and practical challenges of living such as safe housing… Many try to dissociate, at least visibly, with the shelter and lie to neighbours and landlords that they have brothers or fathers earning abroad. Single and younger women reported this more, and often shared a heightened sense of insecurity and vulnerability as a lone woman, without male members in their life.’[footnote 79]

5.3.9 The Legal Aid Society (LAS) noted in 2020 that ‘If a woman leaves her husband without the support of her natal family, unless she is wealthy and educated, there are very few options for her to survive and to manage her children.’[footnote 80]

See also Freedom of movement.

5.4 Love marriage

5.4.1 Most marriages in Pakistan are arranged[footnote 81]. Marriage of choice is often referred to as ‘love marriage’, which may occur with or without the parent’s consent[footnote 82]. According to a 2019 Gilani Research Foundation Survey using a nationally representative sample of 1,287 married men and women, 85% of Pakistanis met their spouse through parents or close relatives and only 5% said they had a love marriage[footnote 83].

5.4.2 Right Law Associates, based in Karachi and Islamabad, which provided advice and services on family law, noted that ‘A marriage without family consent is generally frowned upon.’[footnote 84]

5.4.3 The HRCP 2018 report noted ‘Women who exercised or attempted to exercise their own choice in partners were subjected to confinement, beatings, and life-ending violence by fathers and brothers. Rejected suitors exacted their revenge by violently attacking women, often with acid to disfigure the women they claimed to want to marry.’[footnote 85]

5.4.4 The USSD HR Report 2021 noted that ‘Women are legally free to marry without family consent, but society frequently ostracized women who did so, or they risked becoming victims of so-called honor crimes.’[footnote 86]

5.4.5 Freedom House noted in its Freedom in the World 2022 report, dated 28 February 2022, that:

‘In some parts of urban Pakistan, men and women enjoy personal social freedoms and have recourse to the law in case of infringements. However, historically prominent social practices in much of the country subject individuals to social control over personal behavior, and especially choice of marriage partner. Despite successive attempts to abolish the practice, “honor killing,” the murder of men or women accused of breaking social and especially sexual taboos, remains common, and most incidents go unreported.’[footnote 87]

See also ‘Honour’ crimes.

5.5 Lesbian, bisexual and trans (LBT) women

5.5.1 For information on LBT women in Pakistan please refer to the Country Policy and Information Note on Pakistan: Sexual orientation and gender identity or expression.

5.6 Freedom of movement

5.6.1 Information on the free movement of women was limited.

5.6.2 Findings from the PDHS 2017-18 indicated that 59% of women were ‘in-migrants’[footnote 88], over 90% of whom reported marriage or accompanying family as the reason for migrating[footnote 89]. An ‘in-migrant’ was defined as ‘A person whose district or city of birth within the country is different from her/his district/city of enumeration within the country.’[footnote 90]

5.6.3 The January 2022 DFAT report noted that ‘Article 15 of the Constitution guarantees the right to freedom of movement in Pakistan. Internal migration is widespread and common, but it depends on having both the financial means and family, tribal and/or ethnic networks to establish oneself in a new location. Single women find it especially difficult to relocate.’[footnote 91] The report added, ‘Without support it is extremely difficult for a woman to relocate to escape an abusive relationship. Women who leave their families face physical risk, stigma and steep economic barriers.’[footnote 92]

5.6.4 For general information on freedom of movement, see the Country Policy and Information Note on Pakistan: Background information, including internal relocation.

This section was updated on 21 September 2022

6. Adultery and extra-marital relations

6.1 Legal context

6.1.1 The offence of zina defines ‘adultery’ and is covered under the Offence of Zina (Enforcement of Hudood) Ordinance, 1979. This states ‘A man and a woman are said to commit “Zina” if they wilfully have sexual intercourse without being married to each other.’ Zina is liable to hadd (the punishment decreed by the Quran): stoning to death, or 100 lashes. The Hudood laws apply to both Muslims and non-Muslims, although the punishments differ[footnote 93].

6.1.2 According to Khan and Piracha, a legal consultancy firm in Islamabad, writing in April 2015, ‘… no statistics are available for charges/convictions for simple zina (adultery) nor have we been able to find any legal precedent for a conviction on this charge.’[footnote 94] CPIT were unable to find any recent statistics in the sources consulted (see Bibliography).

6.1.3 An article by Professor Razaleigh Muhamat Kawangit of the National University of Malaysia (Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia), dated 2016, noted:

‘… based on the general rules for convicting zina (illegal sexual intercourse), the testimony of four eyewitnesses or a criminal confession are the only way of conviction which leads to severe punishment of stoning to death or flogging one hundred lashes. To convict a person for the offence of zina with eyewitness testimony is almost impossible. Throughout history, no one has been convicted of zina by four witnesses. Circumstantial evidence in the absence of direct and positive evidence about penetration does not constitute the offence of zina. Circumstantial evidence may be used as corroboration but cannot be made the basis of conviction for zina.’[footnote 95]

6.1.4 Speaking in 2017, retired Justice Haziqul Khairi, former chief justice of the Federal Shariat Court and a former judge of the Sindh High Court, said, without providing any context, that ‘… 1,600 women had been accused of adultery with not a single male accused…’, even though the men were equal partners in the act[footnote 96].

6.1.5 On 24 December 2021 the Lahore High Court (LHC) held that ‘… a woman who re-marries without observing the period of Iddah[footnote 97] (waiting period) after Khula (divorce) cannot be prosecuted under Section 4 of the “Offence of Zina (Enforcement of Hudood) Ordinance 1979” (Hudood Ordinance). The LHC held that re-marriage without observing the period of Iddah cannot be treated as a void marriage. Therefore, it cannot constitute the offence of Zina.’[footnote 98]

6.1.6 Sexual relations between parties who are unmarried is considered ‘fornication’ and is deemed an offence under the Protection of Women (Criminal Law Amendment) 2006 Act. This offence is punishable by imprisonment for up to 5 years and a fine not exceeding 10,000 Rupees for both men and women[footnote 99].

6.1.7 An accusation of adultery must be lodged directly with the court. It is considered an offence to make false accusations of adultery and fornication[footnote 100].

6.1.8 Honour killings are committed against men and women accused of sexual infidelity or indiscretion where the killers, often male family members, seek to avenge the dishonour brought upon the family. An allegation or suspicion of sexual misconduct can be enough to result in such an honour crime (which includes killings as well as other forms of harm)[footnote 101] [footnote 102] (see also ‘Honour’ crimes).

6.2 Unmarried couples and children born outside of marriage

6.2.1 As sexual relations outside of marriage are strictly prohibited under the 1979 Hudood Ordinances[footnote 103], having a child outside of marriage can cause social stigma and such children were referred to as ‘harami’, meaning ‘forbidden under Islam’, according to Anwar Kazmi, an official from the welfare agency, the Edhi Foundation, interviewed by Al Jazeera in 2014[footnote 104].

6.2.2 In correspondence with the British High Commission, dated September 2017, Amna Khan of Khan and Piracha provided their legal opinion on a scenario of an unmarried Pakistani couple living in the UK with a child born out of wedlock:

‘Under Muslim Personal Law (also known as Mahomedan Law) marriage may be validly entered into without any ceremony, therefore direct proof of marriage is not always available or required. Where direct proof is not available, indirect proof may suffice. Under Muslim Personal Law, in the absence of direct proof, marriage is presumed on the basis of any of the following facts:

-

Prolonged and continual cohabitation as husband or wife

-

Acknowledgement by the man of the woman as his wife

-

Valid acknowledgement by the man of the paternity of the child born to the woman subject to the condition, inter alia, that the child is acknowledged to be legitimate and is not the offspring of adultery, incest or fornication. [Principles of Mahomedan Law by Mulla, Sections 268, 344]

‘… clear and reliable evidence that a Mahomedan has acknowledged children as his legitimate issue raises a presumption of a valid marriage between him and the children’s mother (Imambandi vs. Mutasaddi (1918) 45 I.A. 73.’[footnote 105]

6.2.3 Khan went on to note ‘… Marriage solemnized under Muslim Family Laws Ordinance, 1961, requires registration but Nikah does not become invalid due to its non-registration. If a person does not report marriage to the Nikah Registrar for the purpose of registration, he may be held liable under the penal provisions of S.5 (4) of the Muslim Family Laws Ordinance, 1961 but Nikah will not be invalidated.’[footnote 106]

6.2.4 It was Khan’s opinion that:

‘… unless the father of the child refuses to acknowledge the child as his legitimate child, marriage will be presumed from the day the couple commenced together. Hence, given presumption of marriage, such a couple will not be required to re-marry in order to confer legitimacy upon the child and can simply opt for late registration subject to risk of prosecution an imposition of the penal provisions of S5 (4) of the Muslim Family Laws Ordinance, 1061. The prescribed penalty is simple imprisonment of up to 3 months or fine of up to PKR 1000 or both. The fine may not even be imposed if marriage is not denied or disproved and the registrar accepts the fact of a private Nikah, i.e. offer and acceptance in the presence of witnesses having taken place. In fact, to our knowledge, penalty under Section 5 (4) is rarely imposed.’[footnote 107]

6.2.5 In previous correspondence with the British High Commission, dated April 2015, Khan and Piracha, noted that children could not be registered with the National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA) – thus obtaining a Computerised National Identity Card (CNIC) – without providing the father’s name, except when the child was abandoned or in the care of a registered orphanage. However, in the absence of the father’s name, for example, if it was not recorded on a UK birth certificate, a ‘dummy’ name could be provided[footnote 108].

6.2.6 Not having an ID card caused difficulties in accessing vital government-run services. Khan and Piracha stated:

‘The requirement for ID card is becoming increasingly vital for gaining access to admission to educational institutions, employment both in the private and governmental sectors and in all practical day to day affairs such as access to travel by air, telephone connections etc. Any access to healthcare in the social welfare/governmental sector will also be dependent of production of ID card. However, so far, production of ID card is not required for obtaining healthcare in the private sector.’[footnote 109]

6.2.7 In an article published in Courting the Law, ‘Pakistan’s 1st Legal News and Analysis Portal’, dated 15 December 2020, lawyer Ahmed Tariq described the Sunni and Shia legal perspectives on the rights of children born outside of marriage in regard to parental, maintenance and inheritance rights, asserting among other things that ‘Under Islamic law, a child born out of wedlock is considered filius nullius (“a son of nobody”) and considered to own no lineage to the biological father.’[footnote 110]

This section was updated on 21 September 2022

7. Sexual and gender-based violence

7.1 Overview

7.1.1 The Legal Aid Society (LAS), a not-for-profit NGO aiming to reduce challenges in accessing justice for marginalized and underprivileged communities[footnote 111], noted:

‘In Pakistan, there is a consensus on the growing rates of sexual and gender based violence (SGBV). SGBV is a nationwide epidemic with alarmingly low conviction rates. While SGBV is largely prevalent in the country, due to shame and honor, cases of SGBV are rarely reported to save the family’s name and if reported, solved through out of court settlements. Patriarchal socio-cultural norms and a gender insensitive criminal justice system (CJS) couple to give low convictions rates due to approaches that blame the victim, deploy weak investigation and prosecution procedures, and long protracted trials in uncomfortable environments. As a result, one is left with a system that does nothing to provide the sexual assault survivors with justice and only further compounds their issues resulting in an extremely unequal society.’[footnote 112]

7.1.2 A September 2021 publication by the Asian Development Bank (ADB), which provided an ‘analysis of applicable legal norms to make justice more accessible to victims of gender-based violence’, cited a 2020 Islamabad High Court case, which ‘denounced cultural norms that not only tolerate but support violence against women’:

‘“In defiance of the explicit commands of Islam, child marriage, rape and honour killings are not uncommon in our society today. Women are forced into marriage against their will. Heinous traditions of Karokari [‘honour’ killing], Swara [or] Wani [girls given in marriage as a form of compensation[footnote 113]] and other forms of exploitation are being practiced in a State where 97% of the population professes to be Muslim. The tribal and other societal norms seem to have taken precedence over the Islamic injunctions. Female children are not safe… The alarming aspect is that there is no outrage against the practices and mindsets which are a blatant violation of the unambiguous injunctions of Islam. The practices and attitudes highlighted above are prevalent in our society and are public knowledge. Evidence of these practices are the female victims whose heartrending stories are heard by the Courts across the country on a daily basis. These norms are not only offensive but blasphemous”.’[footnote 114]

See also Informal justice systems.

7.1.3 Writing in September 2021 on gender-based violence in Pakistan, Aisha Ayub a lawyer, activist and researcher based in Lahore, stated:

‘The majority of women who are victims of gender-based violence, activists contend, are from the country’s low and middle classes and their deaths are often not recorded, or disregarded.

‘Women’s lives in rural areas differ considerably from those in metropolitan places such as Islamabad, where they enjoy relative safety. Landlords retain social, economic and political clout in rural parts of the country, where feudal structures persist and the administration and police often function subserviently to these chieftains.’[footnote 115]

7.1.4 The 2021 WPS Index stated that ‘As elsewhere in the world, two key aspects of women’s security – organized violence and current intimate partner violence – are closely related across Pakistan. Women in the provinces with the highest rates of organized violence also face the highest rates of current intimate partner violence, underlining the amplified risks of violence at home in the vicinity of conflict.’[footnote 116]

7.1.5 Providing further information on provincial variations of threats of violence at home and in general, the 2021 WPS Index noted:

‘Balochistan and KPK had the highest rates of intimate partner violence in Pakistan – Balochistan at 35 percent and KPK at 24 percent. Women’s rights groups report that gender-based violence increased during the pandemic, when women were forced to stay at home. Human rights groups report more than 1,000 “honor killings” of women annually. The two provinces are also marked by protracted conflict, causing high levels of civilian casualties and displacement.’[footnote 117]

7.1.6 The same report cited higher rates of violence ‘… faced by women in some of Pakistan’s federally administered territories and so-called special regions, which are not official provinces. It has been reported that in those regions, 56 percent of girls experience gender-based physical violence by the age of 15. More than 95 percent of women in those regions believe that their husbands are justified in beating them during domestic disagreements or as punishment.’[footnote 118]

7.1.7 The Punjab Women Helpline 1043, managed and supervised by the Punjab Commission on the Status of Women, recorded an increase in all forms of gender-based violence (GBV) in 2021, when it received 24,296 calls, compared to 22,947 calls received in 2020[footnote 119].

7.1.8 According to official provincial data obtained by the Sustainable Social Development Organisation (SSDO) using Right to Information (RTI) laws, there were 27,182 registered cases of violence against women (VAW – defined by the SSDO as predominantly physical assault[footnote 120]) across all provinces, including Islamabad, for the period January to December 2021 (although Balochistan and KPK only provided 6 months of data)[footnote 121]. The majority of VAW cases (25,751) were recorded in Punjab[footnote 122], an increase of 255% compared to the 7,239 cases registered in the province in 2020[footnote 123].

7.1.9 In addition, the SSDO report, also citing official data, recorded 4,753 rape cases, 990 cases of domestic violence and 381 ‘honour’ killings across Pakistan during 2021[footnote 124].

See also Domestic violence, ‘Honour’ crimes and Rape.

7.2 Child and forced marriage

7.2.1 UN Women stated in a study on child marriage conducted in 2020 and developed in partnership by the NCSW and UN Women, that:

‘Pakistan has the 6th highest number of women married before the age of 18 in the world. Child marriage is prevalent in Pakistan due to several reasons including deeply entrenched traditions and customs, poverty, lack of awareness and/or access to education, and lack of security. Girls are married off young because their parents cannot afford to feed and educate them, and they pass on the “responsibility” to another family. Dropping out of school is both a cause and a consequence of child marriage.’[footnote 125]

7.2.2 The USSD HR Report 2021 noted that:

‘Despite legal prohibitions, child marriages occurred. Federal law sets the legal age of marriage at 18 for men and 16 for women, and a law in Sindh sets 18 as the legal age of marriage for both boys and girls. According to UNICEF, 21 percent of girls were married by the age of 18…

‘The Council of Islamic Ideology has declared child marriage laws to be un-Islamic, noting they were “unfair and there cannot be any legal age of marriage.” The council stated that Islam does not prohibit underage marriage since it allows the consummation of marriage after both partners reach puberty. Decisions of the council are nonbinding.’[footnote 126]

7.2.3 In a report on marriage laws dated April 2022, Pakistan television channel, Geo News, noted ‘Technically, it is illegal in Pakistan to marry before the age of 16. Yet, child marriages are prevalent in the country.’[footnote 127] The report went on to cite some of the laws and penalties at a provincial level:

‘Sindh

‘In 2014, the Sindh Assembly unanimously adopted the Sindh Child Marriage Restraint Act, which raised the legal minimum age of marriage for boys and girls to 18 years. It further made the act a punishable offence. A man, above 18 years, who contracts a child marriage, could now be imprisoned for three years. Men who solemnised an underage marriage can also be locked up for two to three years. Even the parents or guardians, who authorised the marriage, can be prosecuted for failing to prevent it.

‘Punjab

‘In 2015, Punjab amended the Child Marriage Restraint Ordinance 1971 and passed the Punjab Marriage Restraint Act 2015. It increased the imprisonment and fines but kept the legal age of marriage at 16 years.

‘Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

‘In 2016, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa assembly failed to pass Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Child Marriage Restraint Bill 2014, which would have raised the age of marriage to 18 years.

‘Balochistan also continues to be governed by the Child Marriage Restraint Act 1929.’[footnote 128]

7.2.4 According to media sources, in February 2020, during a hearing into the alleged abduction, forced conversion to Islam and marriage of a 14 year old Catholic girl, the Sindh High Court ruled in contravention of the Sindh Child Marriage Restraint Act after declaring that, under Sharia law, men can marry underage girls after they have experienced their first menstrual cycle[footnote 129] [footnote 130].

See also Marriage, divorce and inheritance rights.