OVA - Public Perceptions report 24.11.22 (HTML)

Published 12 January 2023

Background

The Office for Veterans’ Affairs (OVA) leads the UK Government’s effort in driving towards making the UK the best place in the world to be a veteran.

Previous research with the general public shows that, while top-of-mind associations with ex-service personnel are likely to be positive, many believe that service leaves people in a worse mental, physical or emotional position than when they started serving.[footnote 1]

To that end, the OVA commissioned research to improve understanding around perceptions of UK armed forces (UKAF) ex-service personnel across the general public and employers which will help to inform and shape communication and policy initiatives.

Approach

The findings in this report are based on two stages of research undertaken by YouGov – quantitative online surveys and qualitative focus groups and interviews.

The quantitative stage comprised one consistent survey across three separate sample groups:

1 - A large-scale, representative sample of 12,531 people from across the United Kingdom (UK). This was nationally representative by age, gender, region, social grade, education level, and ethnicity.

The quotas on ethnicity reflected the UK population according to the overall proportion of respondents from white or ethnic minority backgrounds. The sample was not representative of individual categories of ethnicity and caution should be taken when interpreting these figures.

The devolved nations (Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland) were deliberately oversampled on a representative basis in order to provide robust sub-group understanding and were then down-weighted in the final tables to provide an accurate view of the UK as a whole

2 - A sample of 1,022 senior decision-makers within UK employers, representative of employers by business size (number of employees), sector, and industry.

3 - A sample of 549 healthcare professionals, including both NHS and private sector workers. The NHS proportion was sampled and weighted to be representative of the NHS workforce.

Fieldwork for the quantitative stage was conducted between 1st and 23rd March 2022.

The qualitative fieldwork took place between 9th May and 9th June 2022. It comprised a total of 11 focus groups with the public and five depth interviews with military journalists. All participants for the focus groups were recruited from the YouGov panel. All groups contained a mixture of age, gender, social grade, and region, and a mixture of views on the armed forces. All focus groups lasted 90 minutes and were conducted online using text-based methodology. The depth interviews took place over the telephone or on Zoom.

Where available and appropriate, this report contains some comparison to the 2018 research with Forces in Mind or previous polling undertaken by the Cabinet Office. Comparisons are provided for illustrative purposes only as there are differences in approach or methodology. The 2018 polling used the phrase “people who have previously served in the UK armed forces” rather than “UK armed forces ex-service personnel”. The Cabinet Office figures are based on a politically representative sample of GB adults rather than a nationally representative sample of UK adults.

Unless otherwise stated, figures and percentages presented are from the quantitative online surveys. All analysis is conducted to two decimal places. Figures in charts or images may not sum to 100% due to rounding or due to the question allowing multiple selections.

Findings from the qualitative research are noted as “the qualitative research”, “focus groups” or “interviews”. Due to the small sample nature of the qualitative research, no findings are statistically significant; the qualitative research adds flavour and depth to the quantitative findings.

Recommendations

Increase visibility of existing support

The overarching recommendation to improve public perceptions of UK armed forces ex-service personnel is to increase the visibility of support available.

Provide more information and guidance for employers

Information and guidance are well received by employers and the OVA should build on this as the appetite is clear. Information should be focused on the diverse range of skills and benefits ex-service personnel can bring to employers.

Challenge perceptions around mental health

There continue to be misconceptions around the mental health of ex-service personnel. Further communications may be needed to help the general public, employers, and healthcare professional understand what challenges ex-service personnel do or do not experience.

Target specific groups with tailored messaging

The OVA should be mindful that different groups across the UK have different attitudes around the UK armed forces and ex-service personnel. Messaging should be tailored to hte needs and interests of each group where possible.

Key findings

Comparisons to previous research

Treatment of ex-service personnel in UK vs other countries

-

July 2021: 12% treatment in UK is better than in other countries

-

January 2022: 12% treatment in UK is better than in other countries

-

March 2022: 12% treatment in UK is better than in other countries

Media portrayal of ex-service personnel

-

2018: 48% media portrayal is positive

-

202: 39% media portrayal is positive

Mental health issues

-

2018: 83% Associate veterans with PTSD

-

2022: 81% Associate veterans with PTSD

Comparisons are provided for illustrative purposes only. Please see ‘Approach’ section for more details.

Overall perceptions

-

Based on the findings from this study, 15% of the general public think that the government is effective in supporting UK armed forces ex-service personnel. In contrast, 43% feel that the government is not effective in supporting ex-service personnel.

-

Over half (54%) of the general public think that ex-service personnel receive too little recognition from the government - which places ex-forces personnel third in terms of a lack of recognition behind NHS staff (59%) and social care staff (66%).

-

While there is not a single outstanding association made by the general public with UK armed forces ex-service personnel, the most commonly held perception is that they are forgotten/ left behind/ ignored (13%). This is followed by the positive perception that they are brave/ courageous (10%).

-

Perceptions are largely shaped by personal experience of ex-service personnel. The qualitative research found that those with first-hand experience of UK armed forces ex-service personnel were generally more empathetic while those who lacked experience were less positive and drew on negative media stories to shape their opinions.

-

39% of the general public think that UK armed forces ex-service personnel are portrayed positively in the media. This is almost double the number who think they are portrayed negatively (20%).

-

The qualitative research found that the majority generally feel positive towards ex-service personnel but are more ambivalent around the wider armed forces. Positive feelings are inspired by respect for their bravery and sacrifice while negative feelings related to pacifism and negative news stories.

-

TV news (36%) is the most commonly mentioned source of information considered important in informing opinion of UK armed forces ex-service personnel. This is followed by TV documentaries (33%) and military charities (30%).

Provision of support

-

More than two-fifths of the UK public do not think the government looks after ex-service personnel (45%), and this rises to just over half of healthcare workers (52%). However, there is a fair degree of uncertainty – a fifth of the public are unsure (21%).

-

One in seven of the UK public think that the UK government’s treatment of ex- service personnel is better than other countries (14%), while a fifth think the treatment is about the same (21%). Uncertainty remains high, with a third of the general public stating that they do not know how UK treatment compares to elsewhere (33%).

-

Participants in the qualitative research felt that in the USA, ex-service personnel are respected by both the public and government - but they were conscious this connection was influenced by media (e.g. Hollywood movies).

-

Perceptions of specific areas of government support for ex-service personnel are low and overshadowed by uncertainty – one in seven think that support with life-changing injuries is effective (15%), but a quarter are unsure (26%).

Employment

-

Many workers think that ex-service personnel would bring positive characteristics or skills to their workplace, with employers particularly likely to think they would bring a strong work ethic (71% vs 62% working public) and resilience (64%, 54%).

-

The vast majority of workers feel comfortable working with UK armed forces ex- service personnel and only around one in seven think there are risks in doing so.

-

Around a third of each group think that there would be no difference the difficulty of ex-service personnel versus civilians finding a meaningful and fulfilling job outside the military. Around one in ten think it would be easier for ex-service personnel while half think it would be more difficult.

-

Similarly, an overwhelming majority of each group think that ex-service personnel need additional support to move into civilian employment.

-

Despite this, only a quarter of those who have employed ex-service personnel offered any specific support or onboarding (24%).

-

Employers have concerns about mental health issues (34%) if they were to employ ex-service personnel but see potential benefits around filling skills gaps (42%).

Community and health

-

Around one in ten believe that it is easy to adjust to life after leaving the UK armed forces. The majority think that there is no difference in access to NHS care or family services – the ease/ difficulty of access is the same as civilians would experience.

-

This perspective is upheld by healthcare workers – 75% of NHS workers believe that ex-service personnel have the same levels of access to NHS care as civilians. with NHS workers slightly more positive than private sector healthcare workers.

-

However, ex-service personnel are associated with health issues – over two- thirds think that mental health problems affect ex-service personnel more than civilians.

-

Participants in the qualitative research believed that ex-service personnel experience a sudden ‘jolt’ back into civilian life rather than a transition and this lack of transition was felt to exacerbate mental health problems, though this was not the experience of the veterans who participated in the groups.

-

There are mixed opinions around whether society values ex-service personnel, although the majority do think that ex-service personnel make valuable contributions to society.

-

Qualitative participants who had knowledge of ex-service personnel challenged other participants’ clichés around mental health problems and issues reintegrating to society.

Overall perceptions

The qualitative focus groups opened with a general discussion of both the UK armed forces and ex-service personnel. Within them, the majority of respondents felt generally positive towards ex-service personnel, though much more neutral towards the wider armed forces. Positive feelings were mostly inspired by the respect they had for those who have served for their country – most admire ex-service personnel for their bravery and sacrifice and admit that serving is not something that they would or could do. Neutral feelings related to the view that it is “just another job”, or that ex- service personnel are not seen in the same way as other employees. Although uncommon, some negative feelings were present and were often related to: pacifism; political opposition to certain conflicts; a belief that government money was being taken up which could be spent elsewhere; media stories of war crimes and brutality seen as going unpunished, though this was a minority view.

The Northern Ireland focus group was slightly more negative than the rest of the qualitative participants, influenced by some personal experiences with the armed forces in the recent past.

“Positive as it requires a lot of selflessness and discipline, many different aspects to it just to qualify and very hard work both physically and later mentally to deal with the situations they are involved in” – General public, England

“I think it is a job, like any other” – General public, Wales

“It’s a 50/50 split for me. I have had friends and relatives who have been part of the armed forces at varying levels who have loved every part it. But the press/news reports sway my opinion. The bullying headlines of recent years have changed my opinion slightly” – Hiring position, small business

Perceptions of the different branches of the armed forces were broadly consistent, although a minority of respondents felt that members of the Royal Air Force or Navy are a ‘cut above’, associating them with the officer class. Comparatively, members of the Army were viewed as being tougher or more resilient than those in other services.

“I’m inclined to believe they’ve been through something if they’re a veteran so branch wouldn’t be an issue” – General public, Northern Ireland

“Yes, mine do. I see the Army as the “strongest” and the RAF and Navy as less dominant/ scary” – Healthcare professional

Perceptions of ex-service personnel were mostly consistent regardless of when the person had served – respondents understand that the political climate as well as methods of warfare have changed but felt that the issues they faced remain the same. Nonetheless, some respondents noted that past wars such as World War One (WWI) and World War Two (WWII) required conscription, whereas modern service has not, and therefore the type of person who volunteers to serve is believed to be of a different mindset.

“Where they have served does not matter. It’s the fact that they were ready to sacrifice themselves to protect us. Also the time they have had to be away from their families and young children” – General public, Wales

“In WW2 many had no choice, it was national service, but now there is a choice to sign up” – General public, England

When asked to rate the level of recognition various groups receive from the government, the UK public tend to think that each group gets ‘too little’ recognition – but the proportion who report this varies. Two-thirds think social care staff receive too little recognition (66%) compared to over a third who think the same of police officers (36%). Only a fifth think social care staff receive the right level of recognition (20%), while two-fifths believe police officers receive the right level (40%).

Given that overall levels of recognition from the government are thought to be low, the key point is how the recognition of UK Armed Forces ex-service personnel compares to other groups in society. A quarter think ex-service personnel receive about the right level of recognition (25%), which puts them on broadly equal footing with NHS staff and social workers (both 26%). Over half (54%) of the public think that UK armed forces ex- service personnel receive too little recognition from the government. This places ex- service personnel joint third (with social workers) in terms of a lack of recognition - behind NHS staff (59%) and social care staff (66%).

Across employers and healthcare workers – over half think ex-service personnel receive too little recognition from the government (54%, 59% respectively), but where this group sits in comparison to other workers varies. For employers, ex-service personnel are second only to social care staff in terms of a lack of recognition (66%). Healthcare staff are more likely than other groups to think social care staff (77%), NHS staff (71%) and social workers (62%) lack recognition from the government.

Likelihood to think ex-service personnel receive too little recognition increases with age. Correspondingly, 18 to 29 year olds are least likely to think this (39%) while those aged 60 and over are most likely to hold this opinion (63%).

Among those with previous service in the UK armed forces, two-thirds (67%) say they think ex-service personnel receive too little recognition from the government compared to 53% among those who have not served in the UK armed forces. The same pattern is also evident among those with family members in the armed forces with 64% stating that ex-service personnel receive too little recognition, which drops to 48% among those who do not have family in the UK armed forces

Q: Do you feel each of the following groups receive too much, too little or the right amount of recognition from government?

Base: All general public (12,531)

Figure 1. Degree of recognition that different groups receive from the government

| Group | Too much recognition | About the right amount | Too little recognition | Don’t know |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Care Staff | 3% | 20% | 66% | 11% |

| NHS Staff | 8% | 26% | 59% | 7% |

| UKAF ex-personnel | 5% | 25% | 54% | 16% |

| Social Workers | 6% | 26% | 54% | 13% |

| Fire and rescue officers | 2% | 34% | 51% | 12% |

| Teachers | 9% | 33% | 49% | 10% |

| Prison and probation officers | 2% | 30% | 47% | 20% |

| Serving UKAF personnel | 6% | 37% | 42% | 15% |

| Police officers | 13% | 40% | 36% | 12% |

Overall, 15% say that they think the government is effective in supporting UK armed forces ex-service personnel (net 4/5 responses where 5 is extremely effective) compared to 43% who say they feel it is not effective (net 1/2 responses where 1 is not effective at all). In comparison, teachers are thought to be supported the most effectively (21% net effective) while people living in deprived communities are supported least effectively (9% net effective).

Based on the findings of this study, perceptions across senior decision-makers in UK employers and workers in healthcare are similar to the overall public. Around one in seven think support for ex-service personnel is effective (15% employers, 12% healthcare) while over two-fifths think the government support for ex-service personnel is not effective (44% employers, 47% healthcare).

While there is relatively little volatility across sub-groups in terms of perceptions of how effective the government is in supporting UK armed forces ex-service personnel, bigger differences are evident in the numbers who think the government is not effective in supporting this group. Those aged over 50 have a more negative perception of government support compared to those under 30 with the highest number of those who think it is ineffective being those aged 50-59 (48%) compared to those aged 18 to 29 who are least sceptical (34%). Men are more likely to say the government is ineffective

(46%) compared to 41% of women. Across UK countries, people living in Wales are most negative (49%) compared to those living in England and Northern Ireland (43% for both) who are the least likely to think the government is ineffective. Those who are limited by a health condition/ disability are also much more likely to think the government is ineffective (48%) compared to those who are not limited by any disability (41%).

Notably, people from an ethnic minority are much more likely than white people to say the support from government is effective (20% vs 14% white). However, uncertainty is also higher for this group (23% do not know vs 18% white).

Those who previously served in the UK armed forces are more polarised than other groups. While a fifth (22%) of this group think the government is effective in their support of ex-service personnel, 50% think it is not effective.

Q: How effective or not do you feel the government is at supporting each of the following groups?

(By support we mean with e.g. initiatives, programmes, funding, advice services) Base: All general public (12,531)

Figure 2. Governmental effectiveness at supporting different groups

| Group | 1 - Not at all effective | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 - Extremely effective | Don’t know |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teachers | 17% | 22% | 28% | 15% | 6% | 13% |

| Police officers | 12% | 18% | 31% | 18% | 6% | 16% |

| NHS staff | 24% | 24% | 24% | 13% | 6% | 8% |

| Those who are unemployed | 21% | 24% | 26% | 13% | 6% | 11% |

| UKAF ex-service personnel | 19% | 24% | 23% | 11% | 4% | 19% |

| Ex-offenders | 19% | 21% | 21% | 8% | 3% | 28% |

| Social care staff | 26% | 28% | 23% | 7% | 3% | 13% |

| People living in deprived communities | 30% | 28% | 21% | 7% | 3% | 12% |

The most common theme which UK adults in this study associate with UK armed forces ex-service personnel is that they are forgotten/ left behind/ ignored (13%). This is followed by the perception that they are brave/ courageous (10%), and then by people believing that they are traumatised/ have post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (9%). These three themes are also the most commonly mentioned by employers and healthcare professionals.

Those who associate the theme of being forgotten/ left behind/ ignored with ex-services personnel are more likely to be older, peaking at 19% among those aged 60 and over. This sentiment is also significantly higher among those who previously served in the UK armed forces (17%) compared to those who have not served (12%). Additionally, more of those who have friends/ family members in the UK Armed Forces are likely to have this perception (19%) compared to those who do not (9%).

Associations with bravery and courage are higher among women (12%) than men (9%). While those with friends/ family in the armed forces (11%) are more likely to associate these themes with ex-service personnel than those without (9%), those who personally served in the UK Armed Forces (6%) are less likely to have this perception than those who have not served (10%).

Q: Thinking of UK armed forces ex-service personnel. What words or phrases come to mind? Please write in up to three below.

Base: All general public (12,531)

Figure 3. Words/phrases associated with UK armed forces ex-service personnel (coded)

| Group | % |

|---|---|

| Patriot/Patriotic | 2% |

| Unprepared / need help adjusting to civilian life | 2% |

| Unemployed | 2% |

| Strong | 2% |

| Not paid enough / underfunded / destitute | 2% |

| Disabled / Injured | 2% |

| Well / Highly trained | 3% |

| Disciplined / hard working / reliable | 4% |

| Service to country | 4% |

| Undervalued / underappreciated | 4% |

| Loyal / dedicated | 4% |

| Mental health issues | 5% |

| Hero | 5% |

| Veterans / Retired / old | 5% |

| Homeless / rough sleeping | 6% |

| Need help / support | 6% |

| Traumatised / PTSD | 9% |

| Brave / courageous | 10% |

| Forgotten / left behind / ignored | 13% |

In the qualitative research, respondents frequently associated ex-service personnel with words or phrases such as ‘resilience’, ‘strong work ethic’ and ‘dedication’. There was an assumption held that military service is hard and strenuous work and anyone that had a military role has these core values ingrained on the job. In addition to this, ex-service personnel themselves more often chose ‘trustworthiness’ than the general public due to the teamwork-focused nature of their previous military roles and the camaraderie they felt whilst serving. Words chosen to describe ex-service personnel were almost all positive – although, on occasion, words like ‘inflexibility’ and ‘coldness’ were also used, influenced by the view that a strongly regimented workplace and traumatic experiences can have negative consequences on an individual.

“All of those skills that people learn in military life, you know, organisational skills, being on time, problem solving, being able to think beyond the immediate challenge and synthesise information, you know, for future challenges, react, stay calm. You know, all of those things.” – Journalist

“I think generally, people do respect our armed forces in a way they don’t in some countries, but I’ll be honest and say I also think we have a very difficult element of the veteran community that don’t do the greater good any justice.” – Journalist

Respondents were more likely to be positive about ex-service personnel when they have had first-hand experience with them – they were generally more empathetic, had positive experiences and were spontaneously aware of reintegration issues. On the other hand, those who lacked exposure to ex-service personnel were less positive and often drew on negative stories that they have seen in the media.

“Dedication yes - had a series of tasks to be completed in a remote location the person carried on until the bulk was completed knowing that the task was time critical - hugely appreciated their efforts” – HR professional

“You have to be resilient to get through it all, I think. I know that a lot of veterans suffer from PTSD and other mental health problems, but that also needs resilience to get through” – General public, Scotland

“I chose inflexibility because they have learned to take orders without question and not think out of the box” – General public, Northern Ireland

The word ‘veteran’ itself often led to associations with the elderly (often male), the poppy, armistice, and PTSD. Interestingly, a noteworthy number of respondents also associated the word with America and the Vietnam war – it was felt that this connection was influenced by media (e.g. Hollywood movies) as well as the feeling that ex-service personnel are held in a stronger regard by the American public and government than in the UK. More than one participant in the focus groups felt that the American population strongly value their conflicts by associating them with freedom – whereas, in the UK, perceptions of ex-service personnel may be interlinked with the politics of war and conflict, meaning support is more conditional.

“I tend to think of coverage of remembrance Sunday at the cenotaph” – General public, England

“Vietnam - probably because of the films” – Hiring position, large company

Some ex-service personnel liked the word ‘veteran’ as they associate it with a feeling of pride that comes as a result of serving for an extended period of time. However, a number of ex-service personnel did not feel like the word ‘veteran’ represents them. They did not necessarily dislike the phrase ‘veteran’, however some related it to old age and felt it describes someone who is suffering with PTSD (again, influenced by media representations). Phrases such as ‘ex-forces’ and ‘ex-service’ were more commonly used as a way of describing their military past.

“Very proud to be a veteran and even more so when we march at the Cenotaph each year in front of the public” – Ex-service personnel

“Very proud to have served and to have been a part an organisation which ever that might be” – Ex-service personnel

“I don’t particularly like the word “veteran” as it makes you sound like a Chelsea Pensioner” – Ex-service personnel

“Older, struggling, brought to the forefront when necessary to say thank you, and then put away” – Ex-service personnel

“I always say ex-forces if asked” – Ex-service personnel

Overall, a greater proportion of the general public think that ex-service personnel are portrayed positively in the media (39%) than those who think they are portrayed negatively (20%). This is also true for the other two audiences – around two-fifths think ex-service personnel are portrayed positively (42% employers, 40% healthcare) and only a quarter think the media portrayal is negative (24%, 23%).

The proportion who believe ex-service personnel have a positive portrayal declines with age. Among 18 to 29 year olds, 45% hold this opinion while this decreases to 36% among those aged 60 and over. Men (41%) are more likely to say they are portrayed positively compared to 38% of women. Additionally, those in England and Wales (40%) are more likely to say that the media portrays ex-service personnel positively compared to those living in Scotland (36%) and Northern Ireland (35%). There is also a large divergence in opinion across ethnicity, with white respondents being far more likely to say that they have a negative portrayal than those from an ethnic minority (21% vs 15%).

In comparison to 2018, when this question was previously asked, the number who said ex-service personnel are portrayed positively has fallen (48% in 2018 vs 39% in 2022). However, the number who think that they are portrayed negatively has remained roughly similar (18% in 2018, 20% in 2022).

Q: Thinking about how UK armed forces ex-service personnel are portrayed in the media, whether on television, in newspapers or elsewhere… Do you think they tend to be portrayed positively, negatively, or neutrally?

Base: All general public (12,531)

Figure 4. How UK armed forces ex-service personnel are portrayed in the media

| Group | % |

|---|---|

| Very positive | 7% |

| Quite positive | 32% |

| Neutrally | 27% |

| Quite negative | 17% |

| Very negative | 3% |

| Don’t know | 14% |

TV news (36%) is the source most mentioned when people were asked which was the most important in informing their opinion of UK armed forces ex-services personnel.

This was closely followed by TV documentaries (33%), and then by military charities (30%). These remain the top three sources of opinion for employers and healthcare workers.

Traditional media including TV documentaries, TV news and newspapers are all more widely mentioned by older age groups while films and social media are skewed towards younger people, especially the 18 to 29 bracket. Older people were also more likely to reference fundraising/ awareness campaigns and military charities.

Q: Which, if any, of the following would you say have been important in forming your opinion of UK armed forces ex-service personnel?

Base: All general public (12,531)

Figure 5. Sources considered important in informing opinion of UK armed forces ex-service personnel

| Group | % |

|---|---|

| TV News | 36% |

| TV Documentaries | 33% |

| Military charities | 30% |

| Friends / family | 26% |

| Newspapers | 25% |

| Fundraising / awareness campaigns | 24% |

| The Armed Forces | 20% |

| Social media | 20% |

| Own personal experience | 17% |

| TV drama | 14% |

| Government / politicians | 13% |

| Films | 11% |

| Other | 3% |

| Don’t know | 20% |

Figure 6. Key perceptions of ex-service personnel by nation

| Perception | UK Total | England | Wales | Scotland | Northern Ireland |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gov’t is effective at supporting UKAF ex-personnel | 15% | 15% (S) | 13% | 13% | 16% |

| Gov’t is ineffective at supporting UKAF ex-personnel | 43% | 43% | 49% (E, NI) | 46% | 43% |

| UKAF portrayed in media positively | 39% | 40% (S, NI) | 40% | 36% | 35% |

| UKAF portrayed in media negatively | 20% | 20% | 20% | 22% (E) | 25% (E, W) |

| Unweighted base: general public | 12, 531 | 8,466 | 1,270 | 2,043 | 752 |

Letters after the figure denote significant differences against that country (E=England/ W=Wales/ S=Scotland/ NI=Northern Ireland)

Provision of support

45% of the UK public do not think the government looks after ex-service personnel (net responses of 1-2, where 1 is ‘does not look after’ and 5 is ‘does look after) and this rises to just over half of healthcare workers (52%). However, it should be noted that there is a fair degree of uncertainty – around a quarter of the public and employers chose the midpoint of the scale and a considerable proportion of each audience simply do not know. Women in particular are more likely to be unsure, with a quarter (24%) saying they do not know if the government looks after ex-service personnel compared to just under a fifth (18%) of men.

There is a clear trend by age across the general public’s sentiment – older respondents aged 60 and over are more likely to say the government does not look after ex-service personnel (51% vs 32% of 18 to 29s) while younger respondents are more likely to say the government does so (15% vs 10% 60+). However, younger respondents are also more likely to be uncertain (29% don’t know, vs 16% 60+).

Those in Wales and Scotland tend to be more negative about the UK government’s treatment of ex-service personnel – half of those nations feel the government does not look after ex-service personnel (50%, 49% respectively). Similarly, white respondents are more likely than those from an ethnic minority to say the government does not look after ex-service personnel (47% vs 30%). A fifth of ethnic minority respondents say the government does look after ex-service personnel (21%) – higher than any other demographic group within the UK public.

Q: Please select the point on the scale that most closely matches your opinion. Base: General public (12,531); Employers (1,022); Healthcare (549)

Figure 7. Whether the UK government does/ does not look after UK armed forces ex-service personnel

| Group | 1 - The UK Gov’t doesn’t look after UKAF ex-service personnel | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 - The UK Gov’t looks after UKAF ex-service personnel | Don’t know |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General public | 20% | 25% | 23% | 9% | 3% | 21% |

| Employers | 18% | 28% | 27% | 11% | 3% | 13% |

| Healthcare | 24% | 28% | 18% | 9% | 4% | 17% |

Participants in the qualitative groups felt that both emotional and practical support for ex-service personnel is currently lacking, and this lack of support translates into difficulties with reintegration into society.

“There are always the stories how they struggle to integrate in society, struggle with jobs and that they don’t get much support from the government” – General public, Scotland

This has not always been the case; participants commented that after World War Two there was a sense of respect for ex-service personnel, with many charities set up in order to offer long-term support. However, there is now a generational split, with younger members of the public being less likely to appreciate and admire ex-service personnel.

Some participants also commented that the lack of ‘visible’ conflict has meant that there is less awareness and sympathy towards ex-service personnel. Some ex-service personnel commented that they felt ‘invisible’ and ‘forgotten’.

“I think most of the public wear poppies for a few days and then don’t really think about them” – General public, Wales

“With World Wars, there were parades for those returning, but now it’s just a quiet exit” – General public, Northern Ireland

“I think older servicemen are treated more respectfully due to the scale and direct impact of WW1 and WW2” – Hiring position

“During conflicts like Iraq and Afghan, veterans seemed to get more notice. During the last decade the public seems to have moved on” – Ex-service personnel

This picture of uncertainty in the current environment continues when juxtaposing the UK government’s treatment of ex-service personnel with other countries. One in seven think the UK government’s treatment of ex-service personnel is better than other countries (14%) and a fifth think it is about the same (21%), but around a third of the public are unsure (33%). Three in ten think the UK government’s current treatment of ex-service personnel is worse than in other countries (31%). Healthcare workers are a more unsure (26% employers, 35% healthcare) and employers are more likely to think treatment is the same (22%, 16%), but otherwise, the professional groups see broadly similar patterns – one in six agree that ex-service personnel are treated better in the UK than elsewhere (16%, 15%), while just over a third think treatment is worse (36%, 34%).

Consistent with the earlier findings, women tend to be more unsure with two-fifths being unsure if UK treatment is better or worse (39%) compared to just over a quarter of men (27%). There is also a clear age trend within the general public where older respondents have a lower opinion than younger respondents – almost two-fifths of those aged 60 and over think the government’s treatment of ex-service personnel is worse than other countries (38%) compared to only a fifth of 18 to 29 year olds (18%).

Also consistent with previous findings, there is a marked division by ethnicity with white respondents continuing to be more negative than ethnic minority respondents. A third of white respondents think UK treatment is worse than elsewhere compared to only a fifth of those from an ethnic minority (32% vs 20%). A quarter of respondents from an ethnic minority think the government treatment of UK armed forces ex-service personnel is better than in other countries (25%).

It appears that perceptions of the government’s treatment of ex-service personnel compared to other countries has remained broadly steady over the year. A similar question was asked by the Cabinet Office in July 2021 and January 2022 and the proportions are in line with this study – one in seven think treatment in the UK is better (12% Jul-21, 16% Jan-22), a fifth believe it is about the same (22%, 19%), around three in ten think treatment is worse (29%, 27%), and around a third simply do not know (34%, 38%). Comparison is provided for illustrative purposes only as there are slight differences in methodology.

Q: Compared to other countries, how well or badly do you think the UK government treats UK armed forces ex-service personnel?

Base: All general public (12,531)

Figure 8. Treatment of UK armed forces ex-service personnel in comparison to other countries

| Opinion | % |

|---|---|

| Much better than in other countries | 4% |

| A little better than in other countries | 11% |

| About the same | 21% |

| A little worse than in other countries | 19% |

| Much worse than in other countries | 12% |

| Don’t know | 33% |

Qualitative participants again compared treatment of UK ex-service personnel with the USA. As discussed, there is a perception that ex-service personnel in the USA are respected by the public and the government; they have ‘heroic’ status which means that they are perceived as being both admired and respected, and seen to have sufficient support.

“In this country nobody really cares but if you go to USA, serving and veterans are treated with respect and get a lot of benefits for having served” – Ex-service personnel

“Governments love the military when they need them but ignore when things are quiet. The comparison with the US is very correct and I have worked for long periods with the US Navy and seen how those leaving get much higher recognition than here” – Ex-service personnel

“I think in some parts they are held in high esteem - however - judging by the number of ex-servicemen who are homeless or in prison - they don’t get enough support.” – General public, Northern Ireland

When thinking in more detail about the support provided by the UK government and its effectiveness in helping UK armed forces ex-service personnel, uncertainty remains high. Over two-fifths are uncertain about whether support offered to ex-service personnel in the criminal justice system is effective (41%) and a third are unsure of the effectiveness in helping ex-service personnel with addictions (34%). Mental wellbeing has the lowest proportion of the general public being uncertain (23%), but the highest proportion saying government support in this area is not effective (56% net 1/2 responses where 1 is not at all effective). The public are the most positive about the support provided to ex-service personnel with life-changing injuries (15% effective).

A quarter of the UK public do not know if overall government support for ex-service personnel is effective (25%) and 46% do not think it is effective (net 1/2 responses where 1 is not at all effective). The story is similar across the other audience groups – 45% of employers and 48% of healthcare workers do not think overall government support is effective.

Employers are slightly more favourable to the government’s support around work – 13% of senior decision-makers think the government’s support for ex-service personnel to develop meaningful careers is effective (vs 10% of the public) and 12% think the same for helping ex-service personnel find employment (vs 9% of the public).

There is little variation when comparing healthcare workers to the general public, even when looking at relevant areas. One in ten healthcare professionals think the government’s support with ex-service personnel’s physical wellbeing is effective (11% vs 10% of the public) and fewer think that support with mental wellbeing is effective (9% vs 7% of the public).

The general public in Scotland is less likely than in the other UK nations to think the government’s support on various areas is effective, particularly with financial difficulties (5%), mental wellbeing (5%), housing needs (6%), and finding employment (7%).

Consistent with previous findings, respondents from an ethnic minority are more positive about the government’s support of UK armed forces ex-service personnel than white people. In this case, those from an ethnic minority are more likely to say the government’s support in each area is effective.

Q: How effective or not do you feel the government are at supporting UK armed forces ex- service personnel…

Base: All general public (12,531)

Figure 9. Perceived effectiveness of UK government support for UK armed forces ex-service personnel

| Group | 1 - Not at all effective | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 - Extremely effective | Don’t know |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 20% | 26% | 22% | 6% | 2% | 25% |

| With life-changing injuries | 18% | 21% | 20% | 12% | 3% | 26% |

| With their physical well-being | 18% | 23% | 21% | 8% | 2% | 28% |

| Developing meaningful careers | 16% | 22% | 22% | 7% | 2% | 31% |

| Find employment | 17% | 23% | 21% | 7% | 2% | 30% |

| With housing needs | 22% | 24% | 17% | 6% | 2% | 29% |

| Settle back into civilian life | 20% | 26% | 19% | 6% | 2% | 27% |

| With their mental well-being | 29% | 27% | 14% | 5% | 1% | 23% |

| In financial difficulties | 23% | 24% | 15% | 4% | 2% | 32% |

| In the criminal justice system | 18% | 18% | 17% | 4% | 2% | 41% |

| With addictions | 25% | 24% | 12% | 3% | 1% | 34% |

Some qualitative participants pointed out that they felt there is increased awareness and resources for mental health problems, with support starting to be more tailored to needs, and more of an understanding of the impacts of warfare.

Generally, participants felt that ex-service personnel are (and should be) treated respectfully, but they should also be treated equally, meaning that they should not receive ‘special’ treatment. Rather, support should be specific to their needs and should be adapted according to the individual and their experiences. Focus group participants think the word ‘special’ should be avoided as this descriptor is problematic, with HR professionals commenting that ex-service personnel should be judged according to their abilities and skills.

“Not special in my opinion, but treatment specific to their needs.” – General public, England

“Why should they? [receive special treatment]. Do nurses, firefighters, etc do any less and deserve any less than soldiers.” – General public, Northern Ireland

“Respectfully but also equally. For example, at a job interview, should be judged on skills and achievements like everyone else.” – Hiring position

Mental health support was a key area where ex-service personnel were believed to need support, alongside housing and healthcare. With this in mind, qualitative research participants called for holistic care around finances, health and employment from government, the Ministry of Defence (MoD), and charities.

“Since they served to protect the country they live in I believe the government should offer them more services. Better health care, better financial help, help in finding work/housing.” – General public, Scotland

“I think Veterans should automatically have access to a full spectrum of health care services; treatment, rehabilitation, education, counselling, and community support etc.” – HR professional

“I just feel we should have more specified resources. i.e. A veteran mental health facility more focused towards the mental health they may need. Assistance finding a job that will help them adjust to civilian life. It’s not special treatment just more specific.” – Hiring position

Participants believed that they think a holistic and specific reintegration programme would have a positive impact on the rest of society, as ex-service personnel have knowledge and skills which add value both in daily life and in the workplace.

In the qualitative research, ex-service personnel were largely aligned with the public’s view. Most do not ‘publicise’ that they were part of the armed forces in their day-to-day lives, as they do not believe it is necessarily a help or a hindrance. Generally, they would like to see more support and funding around health, particularly mental health, alongside support with housing and reduced tax on their pensions. Some commented that they are only supported when publicity is needed or when it is ‘politically expedient’.

“I don’t think they should be treated with awe, but there should be some reverence for the service done.” – General public, Wales

Drivers of perception

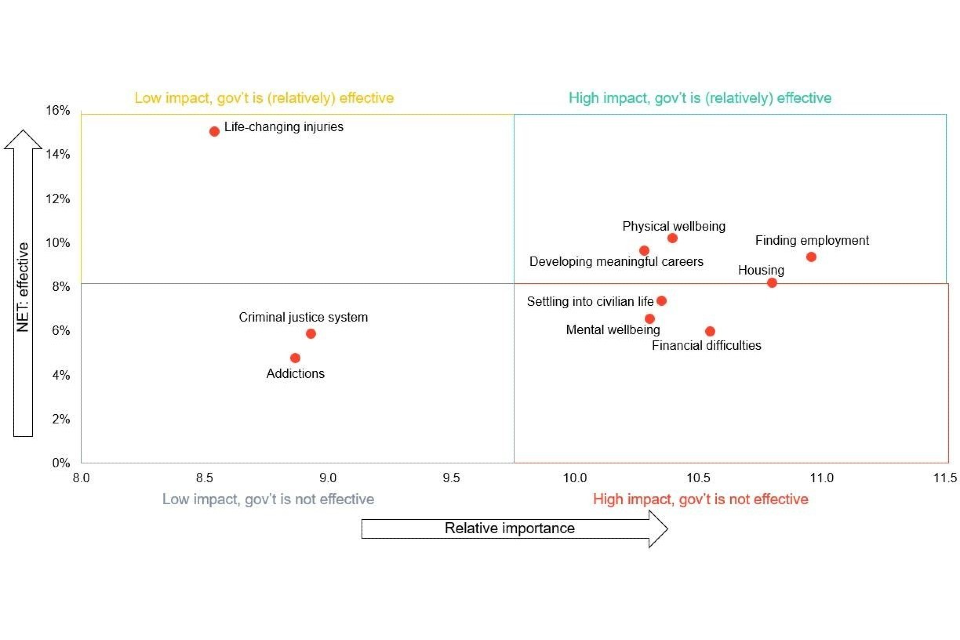

The results presented in this section are the output of a linear regression model that aims to identify what areas are most closely associated with an overall perception of the government being effective at supporting UK armed forces ex-service personnel. This multivariate analysis provides us with a robust understanding of attitudes by looking at a number of areas at the same time, isolating the effect of each factor after taking into account the simultaneous effects of other factors.

For the purposes of this analysis, the question around perceived effectiveness of support (figure 10) was used with the overall effectiveness taken as the dependent variable and the other areas used as the independent variables. As noted earlier in this chapter, there are high levels of uncertainty around how effective the government is in supporting ex-service personnel. Respondents who selected ‘don’t know’ were excluded from the model but it should be noted that this model is based on the public’s perception of effectiveness.

By their relative importance, the main areas that drive the overall perception of effective government support are supporting ex-service personnel to find employment, supporting them with housing needs, and supporting them with financial difficulties.

However, these were closely followed by other areas which all had similar levels of importance.

However, mapping each area’s relative importance from the model against the survey data of how effective the government is seen to be at providing that support provides insight into key areas for further development. For example, the government is seen to be comparatively quite effective in supporting ex-service personnel with life changing injuries, but this is the least important area in terms of driving overall perceptions.

The three most important areas driving overall perceptions have fairly middling levels of current effectiveness – less than one in ten think the government’s support is effective at each (9% finding employment, 8% with housing needs, and only 6% for ex-service personnel in financial difficulties).

Figure 10. Relative importance for perceived effectiveness of overall government support for UK armed forces ex-service personnel

Figure 10. Relative importance for perceived effectiveness of overall government support for UK armed forces ex-service personnel

Charities as drivers of perceptions

From the qualitative conversations with journalists who write on military affairs and ex- service personnel - it became clear the perception is that charities, as part of their campaigning work, may be partly responsible for driving the public perception of ex- service personnel being both irreparably harmed by service and being forgotten about by the authorities.

They felt that these communication strategies may be used by charities to encourage people to donate – doing so in the belief that only the third sector is able to support ex- service personnel who have been marginalised by the military and by the government.

“[Charities] spotlight the things that would generate an emotional reaction in the public in order to give them money to do the work that they wanted to do for the community. I think that just outstrips all of the other stories that would be running in terms of public perception about the non-Mad, Bad and Sad. We make a positive decision to balance Mad, Bad and Sad with normal positive stories about the armed forces communities.” – Journalist

“There is a very lazy perception that, you know, ‘Oh, there are loads of homeless veterans, and nobody wants to help them, and nobody cares about them, etc.’ Whereas if you speak to the charities, you know, that are working literally on the ground, they will say there are a handful of veterans who are homeless.” – Journalist

Reaction to government support schemes

During the focus groups participants were presented with two different government support schemes and asked for reactions:

-

The veterans’ railcard that allows one third off rail fares, as available from 11 November 2020.

-

The increase in mental health funding for Afghan ex-service personnel where 51 projects across the UK will receive grants to support young children and their families, including £600k to Samaritans for a new peer support helpline.

-

Participants commented that the railcard lacks relevance for those without access to public transport in more rural areas or for those who do not rely on trains. It was also felt to be insufficient – both the public and ex-service personnel wanted to see transport being free for ex-service personnel, rather than discounted. Participants also commented that they would like to see this scheme offered to nurses and other public health workers.

Overall, this initiative was felt to be tokenistic and indicative of ‘gesture politics’, not working to address some of the broader structural issues around ex-service personnel and their reintegration into society e.g., housing and health.

“A good idea but I think practical help in finding employment, how & where to go to sort out all the small things that they won’t have had to worry about as well as offering support for the mental transition they have to make would be more helpful.” – General public, Scotland

“How is that going to help them get a job and integrate with society?” – General public, Wales

“Not unless all public sector staff are entitled to the same. Nurses don’t even get free parking at the hospitals they work at half the time. Not sure why ex-soldiers should get cheaper transport.” – General public, Northern Ireland

“It’s a start. Now do something about their mental health, their housing needs, their access to the labour market, their homelessness, their physical recovery after injury.” – HR professional

“I think that is a token gesture. Cheap travel does not equate to proper care and support for veterans’ welfare” – Ex-service personnel

On the other hand, the increase in funding for projects focussed on Afghan ex-service personnel was viewed positively as it aimed to address the root issues around reintegration, therefore fulfilling the need for relevant support for ex-service personnel. This relates to stimulus shown regarding bespoke mental health funding for personnel who served in Afghanistan (separate to government support for ex-service personnel provided through the NHS).

However, participants were frustrated to see that this initiative was only aimed towards those who served in Afghanistan – they would like to have seen the support go wider than that. Additionally, they called for more detail on who would offer the support (government, MoD or armed forces budget), as well as what the support would look like, as the £600k budget did not sound adequate.

Finally, participants highlighted the need for mental health support across the population, again commenting that ex-service personnel should not necessarily receive ‘special’ treatment.

“I do think veterans getting better mental health support will help society in general (everyone getting better mental health support will also help society, but I guess it’s a step in the right direction)” – General public, Wales

“I think this is really good too. Probably feels more appropriate/ relevant than the railcard, but both are fab gestures,” – HR professional

“They use figures which appear big but in the great scheme are not a lot given the number of veterans and how much certain types of support cost.” – Ex-service personnel

Regional highlights

There are a range of opinions across the devolved nations when it comes to evaluating the

UK government’s provision of support for ex-service personnel. Those in Wales and Scotland are the most likely to think that the UK government does not look after ex- service personnel. Scotland in particular is less likely to think the government’s support is effective across several areas.

Figure 11. Key perceptions around support by nation

| Perception | UK Total | England | Wales | Scotland | Northern Ireland |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net: The UK gov’t does not look after UK armed forces ex-service personnel | 45% | 45% | 50% (E, NI) | 49% (E, NI) | 44% |

| Gov’t support is effective: financial difficulties | 6% | 6% (S) | 6% | 5% | 6% |

| Gov’t support is effective: mental well-being | 7% | 7% (S) | 7% (S) | 5% | 6% |

| Gov’t support is effective: housing needs | 8% | 8% (S, NI) | 8% | 6% | 6% |

| Gov’t support is effective: finding employment | 9% | 10% (S) | 9% | 7% | 7% |

| Unweighted base: general public | 12, 531 | 8,466 | 1,270 | 2,043 | 752 |

Letters after the figure denote significant differences against that country (E=England/ W=Wales/ S=Scotland/ NI=Northern Ireland)

Employment

Overall, a majority of our three sample groups would be comfortable working with UK armed forces ex-service personnel. Three-quarters of the working public would feel comfortable working with ex-service personnel and the figure rises for healthcare workers and senior decision-makers within UK employers (figure 12).

Reflecting the generally high levels of comfort, only around one in seven feel there are risks in working with ex-service personnel. The working public are the most likely to hold this view (14%), with employers the least likely to think risks are present (11%).

Across the working public, those in Northern Ireland are significantly less likely than the rest of the UK to feel comfortable with an ex-service personnel colleague (65%) and more likely to feel there are risks. Similarly, UK adults from an ethnic minority are much less likely than white adults to feel comfortable with this (58% vs 76%) and more likely to say there are risks (21% vs 13%). Disabled people are also slightly less comfortable working with ex-service personnel than those without a disability (71% vs 75%) and more likely to say there are risks (18% vs 13%)

Q: To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements? Net strongly agree/ agree percentages

Base: General public in work (6,943); Employers (1,022); Healthcare (549)

Figure 12. Agreement about working with UK armed forces ex-service personnel

| Group | General public | Employers | Healthcare |

|---|---|---|---|

| I would be comfortable working with UKAF ex-service personnel | 74% | 84% | 82% |

| There would be risks in working with UKAF ex-service personnel | 14% | 11% | 13% |

When asked what characteristics UK armed forces ex-service personnel would bring to their workplace, a majority see positive influences like work ethic (62%), resilience (54%), and dedication (53%). UK employers are more likely than the general public to think ex-service personnel bring positive attributes – particularly trustworthiness, where around half of employers think ex-service personnel are trustworthy (49%), compared to only two-fifths of the working public (40%). Healthcare workers tend to be less optimistic about potential attributes than employers but are more positive than the public.

Within the working public, men are more likely than women to think ex-service personnel would be flexible (24% vs 18%) or trustworthy (41% vs 38%), but they are also more likely to think ex-service personnel will be aggressive (15% vs 12%).

Northern Ireland respondents in particular believe ex-service personnel to be aggressive in the workplace (20%), while both Scottish respondents and Northern Ireland respondents are less likely than the UK average to think ex-service personnel will be dedicated (48%, 46% respectively).

There is a broad upward trend by age, with older workers generally more positive about potential characteristics than younger workers. For example, half of those aged 60 and over think ex-service personnel would be trustworthy, compared to only a third of those aged 18 to 20 (32%). The reverse is seen for the negative attributes – one in ten 18 to 29 year olds think ex-service personnel would be cold (11%), compared to only 5% of those aged 60 and over.

There is a clear divide across ethnicity – members of the working public from an ethnic minority are less likely than white workers to think ex-service personnel bring any positive attribute. They are more likely than white respondents to think ex-service personnel bring the negative attributes listed – particularly aggression (16% vs 13%), coldness (11% vs 7%), and inflexibility (10% vs 7%).

Q: If you were working alongside UK armed forces ex-service personnel, which, if any, of the following characteristics do you think they might bring?

Base: General public in work (6,943); Employers (1,022); Healthcare (549)

Figure 13. Perceived work characteristics of UK armed forces ex-service personnel

| Characteristic | General public | Employers | Healthcare |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strong work ethic | 62% | 71% | 65% |

| Resilience | 54% | 64% | 61% |

| Dedication | 53% | 57% | 56% |

| Trustworthiness | 40% | 49% | 42% |

| Flexibility | 21% | 24% | 24% |

| Aggression | 13% | 11% | 11% |

| Inflexibility | 7% | 11% | 7% |

| Unpredictability | 10% | 8% | 11% |

| Coldness | 8% | 8% | 6% |

| Unsociable | 4% | 2% | 5% |

| Other | 3% | 4% | 4% |

| Don’t know | 11% | 4% | 11% |

Half or more of the working public think that UK armed forces ex-service personnel would bring effective communication skills (50%), leadership skills (55%), or problem solving skills (61%). Employers are more likely than the public to think that ex-service personnel would bring project management skills to a workplace (41%), while healthcare workers are much more likely than the other two groups to note analytical skills (45%).

Within the general public, men are more likely than women to believe ex-service personnel would be trustworthy (41% vs 38%) or flexible (24% vs 18%). However, men are also more likely to think that ex-service personnel could bring negative characteristics such as aggression (15% vs 12%), coldness (8% vs 7%), and be unsociable (5% vs 3%).

Consistent with the perceptions of characteristics, older workers are generally more likely than younger workers to see valuable skills in working with ex-service personnel. Two thirds of those aged 60 and over think they would bring problem solving skills (66%) while just over half of those aged 18 to 29 would say so (53%). Similarly, those from an ethnic minority are less likely than white workers to say ex-service personnel bring particular skills.

As elsewhere, Northern Ireland workers tend to be more pessimistic than the rest of the UK – being less likely to say ex-service personnel could bring each skill to a workplace. Scottish workers are also less likely than English or Welsh respondents to think that ex-service personnel would bring leadership skills (51%).

Q: And which, if any, of the following skills do you think they might bring? Base: General public in work (6,943); Employers (1,022); Healthcare (549)

Figure 14. Perceived work skills of UK armed forces ex-service personnel

| Characteristic | General public | Employers | Healthcare |

|---|---|---|---|

| Problem solving | 61% | 67% | 68% |

| Leadership | 55% | 57% | 56% |

| Effective communication | 50% | 46% | 52% |

| Project management | 31% | 41% | 37% |

| Analytical | 36% | 34% | 45% |

| Other | 2% | 3% | 3% |

| Don’t know | 14% | 10% | 14% |

Across the qualitative discussions there was a generally positive response when asked to consider how ex-service personnel might fit in to the jobs market. This was a view largely based on speculation though some did have direct or indirect experience of ex- service personnel returning to work. Generally, it was felt that military service imbues ex-service personnel with unique but also transferable skills that they can constructively put to use in the jobs market.

These skills are broad and varied and encompass a range of different things such as discipline, and problem solving, as well as patience and resilience. The types of professions mentioned tended to be in the area of security, logistics, and engineering. They do depend on rank and seniority as well; it was pointed out that those in senior positions in the military will be unlikely to transition to jobs where they are required to follow orders. That said, it was made clear by participants that there was no set route – many may take up roles ranging from the technical and skilled to the more manual, from people-facing to more isolated roles.

“Potentially things that have very set rules/regulations where there is less interpretation required. But will depend very much on the individual.” – General public, Wales

“That will vary a lot - some will actually have learned trades, etc. when serving (chefs, drivers, mechanics, etc.) whilst others won’t [have] any easily transferable skills – the attitude can generally be a benefit to any organisations if properly harnessed, though.” – General public, Scotland

Overall, people do think UK armed forces ex-service personnel have the skills and experience to cope with working life – a shared perception held by around half of each of our three groups. A quarter of the general public, employers, and healthcare professionals have mixed views, but only around one in ten do not think ex-service personnel are skilled/ experienced enough.

There is little variation in perceived fitness for working life across the general public demographics – as noted previously, women tend to be more unsure (19% vs 16% men). However, disabled people are more likely than those without a disability to say ex-service personnel do not have the skills/ experience needed (13% vs 9%). Similarly, there is little variation in opinion across employers or healthcare professionals regardless of sector or organisation size.

Q: Please select the point on the scale that most closely matches your opinion. Base: General public (12,531); Employers (1,022); Healthcare (549)

Figure 15. UK armed forces ex-service personnel’s perceived fitness for working life

| Group | 1 - UKAF ex-service personnel don’t have skills / experience to cope with working life | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 - UKAF ex-service personnel do have skills / experience to cope with working life | Don’t know |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General public | 3% | 8% | 28% | 30% | 17% | 18% |

| Employers | 2% | 7% | 25% | 38% | 18% | 9% |

| Healthcare | 2% | 7% | 25% | 34% | 21% | 12% |

Despite this perception that UK armed forces ex-service personnel would bring positive attributes, positive skills, and are fit for working life – most think that they would find it more difficult than civilians to find meaningful and fulfilling work outside the military.

Only around one in ten of each audience think ex-service personnel would find it easier than civilians to do so.

Within the general public, those from an ethnic minority are more likely than white respondents to think ex-service personnel will find it easier than civilians to get a job outside the military (17% vs 11%). Similarly, those with a disability that limits their day- today life are more likely than those without to say this (14% vs 10%).

Looking at employers specifically, senior decision makers in the public sector are much less likely than private sector to think ex-service personnel will find it easy to get employed outside of the military (4% vs 13%).

Q: Do you think UK armed forces ex-service personnel would find it easier or harder than a civilian to find a meaningful and fulfilling job outside the military?

Base: General public (12,531); Employers (1,022); Healthcare (549)

Figure 16. Easier/ harder than civilians to find a meaningful and fulfilling job outside the military

| Group | Would find it much easier than a civilian | Would find it easier than a civilian | No different to a civilian | Would find it harder than a civilian | Would find it much harder than a civilian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General public | 2% | 9% | 33% | 48% | 7% |

| Employers | 1% | 9% | 36% | 46% | 6% |

| Healthcare | 2% | 7% | 33% | 51% | 7% |

In light of this, it is unsurprising to see that the overwhelming majority of all three audiences think that UK armed forces ex-service personnel need additional support to move into civilian employment – around three-quarters of each audience think so.

For the UK public, there is a clear age trend in perceived need for employment support – only 61% of 18 to 29 year olds think ex-service personnel need this support, rising to 81% of those aged 60 and over. Women are more likely than men to think ex-service personnel need support (74% vs 70%). Those in Northern Ireland are the least likely to think additional support is needed – 6% disagree with the statement, double the rest of the UK nations (each 3%).

Those from an ethnic minority were more likely than white respondents to think that ex- service personnel would find it easier than a civilian to find employment and so it follows that those from an ethnic minority are also less likely to think ex-service personnel need support (61% vs 74%). However, this is not true for disabled people – although they were also more likely than those without a disability to think ex-service personnel can find civilian employment, they are also more likely to say ex-service personnel need additional support to do so (76% vs 71% no disability).

Across employers, those in the voluntary/ third sector are the most likely to think ex- service personnel should have additional support moving into civilian employment (84%) – more so than private (71%) or public (72%) sector decision makers. This perhaps demonstrates a wider attitude of voluntary/ third sector employers as more favourable towards support, in line with their charitable goals.

Q: To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement? UK armed forces ex- service personnel need additional support to move into civilian employment

Base: General public (12,531); Employers (1,022); Healthcare (549)

Figure 17. Whether UK armed forces ex-service personnel need civilian employment support

| Group | Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree | Don’t know |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General public | 29% | 43% | 13% | 2% | 1% | 12% |

| Employers | 25% | 48% | 15% | 2% | 1% | 10% |

| Healthcare | 28% | 48% | 13% | 1% | 1% | 9% |

Despite the positive response when considering what skills ex-service personnel bring to the workforce, qualitative participants also identified barriers to employment that may be faced by those leaving the armed forces. As discussed previously, some of these are ‘life skills’ such as navigating the application process. Some concerns also related to ex-service personnel’s interpersonal skills - focus group participants felt that whilst those who had more senior ranks may find it easier to interact in a professional context, more junior ranks may not, and some thought that there may be a deficiency in some of the softer skills. Furthermore, there was a perception of difficulties in adjusting to new working routines; being less reliant on receiving orders in a less hierarchical structure.

“It’s down to the veterans to sell their experience as relevant to the job they’re applying for, which may not be easy. So career help for CV and interviews, and general motivation and guidance on what they could apply for could really help.” – General public, England

“Practical nature, as mentioned before hiring managers don’t understand the skillset of veterans. And perhaps veterans don’t use the right terminology to demonstrate their skills.” – General public, England

The qualitative groups also addressed whether or not some of these issues might lead to employers having a bias against hiring ex-service personnel and generally the view was this would not be the case; partly because discrimination is less common nowadays, particularly in a buoyant jobs market, and, moreover, most employers would be able to make use of the skills described above.

Part of the reason that desire for additional support is so high may be that there is very low awareness of the available support asked about in the survey. Although not intended as a comprehensive list of initiatives/ support available, eight in ten of the general public or healthcare workers had not heard of any of the initiatives listed (both 81%). Awareness is slightly better amongst employers, but over two thirds had not heard of any (69%). Awareness is highest for the Armed Forces Covenant, rising to a quarter of employers who had heard of this (25%).

Employers in the public sector are the most likely to have heard of at least one initiative (only 56% had not heard of any). Over a third in the public or voluntary sectors had heard of the Armed Forces Covenant (37%, 36% respectively), compared to only one in five private sector employers (21%). There is generally little variation across employers for their awareness of the National Insurance Contributions holiday or the Great Place to Work for Veterans scheme, although these are both relatively new schemes so low awareness is to be expected.

Q: Which, if any, of the following were you aware of?

Base: General public (12,531); Employers (1,022); Healthcare (549)

Figure 18. Awareness of employment support

| Scheme | General public | Employers | Healthcare |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Armed Forces Covenant | 12% | 25% | 13% |

| The defence Employer Recognition Scheme | 6% | 6% | 4% |

| The National Contributions (NICs) holiday for hiring a UK Armed Forces ex-service personnel in their first job after leaving the armed forces | 5% | 8% | 6% |

| The Great Place to Work for Veterans scheme | 4% | 5% | 4% |

| None of these | 81% | 69% | 81% |

Recruitment and onboarding

Focussing more specifically on employer’s recruitment and on-onboarding of UK armed forces ex-service personnel – a third of UK employers say they have employed ex- service personnel (35%), although a similar proportion do not believe they receive any applications from ex-personnel (33%).

Employers in the public sector are the most likely to say they receive applications from (26%) or have employed (49%) ex-service personnel. Over a third of private or third sector organisations claim they do not receive any applications from ex-service personnel (36%, 43% respectively).

A considerable proportion of senior decision-makers within employers do not know if they employ/ receive applications from ex-service personnel (26%). This is likely explained by a lack of data collection – only one in six employers say they collect information on whether staff are ex-service personnel (17%, rising to 26% of public sector). This implies that private and third sector organisations may already employ/ receive applications from ex-service personnel but are not aware of it.

Q: Thinking about recruiting UK armed forces ex-service personnel, which of the following applies to your organisation?

Base: Employers (1,022)

Figure 19. Current employment of UK armed forces ex-service personnel

| Scheme | % |

|---|---|

| We have employed UK Armed Forces ex-service personnel | 35% |

| We receive applications from UK Armed Forces ex-service personnel | 19% |

| We don’y receive applications from UK Armed Forces ex-service personnel | 33% |

| Don’t know | 26% |

Despite a majority of employers agreeing that UK armed forces ex-service personnel need additional support to move into civilian employment (figure 18), only a quarter who currently employ ex-service personnel do provide some form of specific support for them (24%).

The perception of need does not vary according to previous experience of ex-service personnel employment – 77% of those who have employed ex-service personnel think they need additional support to move into civilian employment and 74% of those who do not receive applications from ex-service personnel think the same.

Q: Thinking about UK armed forces ex-service personnel who have been employed by your organisation, have you provided any specific support or programmes to help them at the onboarding stage or to further their career?

Base: Employers who employ ex-service personnel (328)

Figure 20. Availability of support for UK armed forces ex-service personnel

| Support provided | % |

|---|---|

| Yes | 24% |

| No | 50% |

| Don’t know | 26% |

A majority of employers would be no more or less likely to hire UK armed forces ex- service personnel over an equally matched candidate. Three in ten say they would prefer to hire the ex-service personnel (30%), while only 4% would be less likely to do so.

Employers in the private sector are the most likely to prefer the ex-service candidate – a third reporting this (32%), compared to only a quarter of public sector employers (27%) and even fewer in the third sector (13%). Three quarters of decision-makers in the third sector indicated they would have no preference between two equally matched candidates (74%).

When asked why they would be less likely to hire ex-service personnel, respondents named some of the characteristics discussed earlier (figure 14) such as inflexibility, aggression, or a lack of relevant skills.

Q: If you were recruiting and had two equally matched candidates, please select the point on the scale that most closely matches your opinion.

Base: Employers (1,022)

Figure 21. Likelihood to employ UK armed forces ex-service personnel over equally matched candidate

| Group | 1 - Less likely to employ UK Armed Forces ex-service personnel | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 - More likely to employ UK Armed Forces ex-service personnel | Don’t know |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employers | 2% | 2% | 55% | 21% | 8% | 12% |

Two-fifths of employers do not have any concerns about employing UK armed forces ex-service personnel (40%). However, a third have concerns about possible mental health issues (34%). This view is also held by the healthcare audience – 33% of healthcare professionals who are senior decision-makers or line managers would be concerned about possible mental health issues. Perceptions around ex-service personnel and mental health issues are discussed in more detail in a later chapter.

The other concerns are only held by one in six or fewer employers and echo the characteristics/ skills mentioned previously – 16% are concerned about social skills or difficulties working with different cultures; echoing that, in figure 14, we saw that some employers think ex-service personnel have poor soft skills such as being ‘aggressive’ (11%), ‘inflexible’ (11%), or ‘cold’ (8%).

Those in the private sector are more concerned than those in the public sector around ex-service personnel’s work skills/ capabilities (15% vs 7%). Employing ex-service personnel appears to put some concerns to rest - those who have already employed ex-service personnel are less concerned than those who have not done so (45% have no concerns vs 38% who do not receive applications).

Q: Which, if any, of the following would concern you about employing UK armed forces ex- service personnel?

Base: Employers (1,022)

Figure 22. Employer concerns about employing UK armed forces ex- service personnel

| Concerns | % |

|---|---|

| Possible mental health issues | 34% |

| Their social skills | 16% |

| Their ability to work with colleagues from different cultural backgrounds | 15% |

| Their work skills and capabilities | 13% |

| Their previous educational attainment | 12% |

| Possible physical health issues | 8% |

| Other | 3% |

| Don’t know | 6% |

| Not applicable - would not be concerned about anything | 40% |