The hidden victims: Report on Hestia’s super-complaint on the police response to victims of modern slavery

Updated 4 April 2022

Applies to England and Wales

1. Senior panel foreword

Modern slavery takes several forms, including sexual or criminal exploitation, forced labour and domestic servitude. It is an abhorrent crime perpetrated against some of the most vulnerable people in society. It is also a complex, harmful and largely hidden crime. The police don’t tackle it alone. They work with law enforcement partners, the voluntary sector, specialist advisory organisations, the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) and the Home Office.

Hestia[footnote 1] put forward this super-complaint through a report entitled Underground lives, Police response to victims of modern slavery, Hestia, March 2019. It raises various concerns about the police response to modern slavery, including how police identify, deal with and support victims of modern slavery, and how modern slavery crimes are investigated.

Hestia believes the current police response leads to victims not engaging with the police or supporting modern slavery investigations and prosecutions and that, as a consequence, offenders are not brought to justice. It is concerned that offenders are instead left free to continue their exploitation of vulnerable people, causing harm to both victims and the wider public interest. The public interest may be harmed, for example, if an individual victim or witness who is being exploited by an organised crime group (such as a group organising human trafficking) doesn’t feel able or confident to report the matter to the police or to support an investigation of the crimes committed. In this way, an opportunity is missed to prosecute the perpetrators and thereby protect the public from continuing criminal activities.

HMICFRS, the College of Policing and the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) are responsible for assessing, investigating and reporting on police super-complaints. We have collaborated on this investigation and on drawing conclusions.

Some of the issues raised in the super-complaint reflect or replicate those considered in our first joint super-complaint Safe to share?. This focused on the sharing of information between police and immigration enforcement, and how the police balance answering questions about the immigration status of victims of crime with the priority of safeguarding them and investigating the crimes against them. Elements of our findings and recommendations are also relevant to this investigation, and we refer to those in the report.

Similarly, many of the themes of the super-complaint echo findings from HMICFRS’s 2017 thematic inspection report Stolen freedom: the policing response to modern slavery and human trafficking . This allowed us to use our assessment of progress made against the recommendations in that report as a major source of evidence for this investigation.

1.1 What we found

Our investigation identified that the police response to modern slavery has broadly improved since the 2017 HMICFRS modern slavery inspection. We recognise that there has been some good progress, particularly in some forces and by specialist units. However, we have found that there is still too much inconsistency throughout forces, and that more needs to be done to recognise and support victims of slavery, and to ensure that these crimes are investigated effectively. It is clear that further steps need to be taken because some aspects of the police response remain unsatisfactory and may be causing significant harm to the interests of the public.

While we recognise we have not been able to observe police interactions with victims in real time, evidence shows that modern slavery victims do not always receive the response and treatment they deserve. For example, they are not always made to feel safe or referred for support through the appropriate mechanisms, and there are still some victims who are afraid they will be treated as immigration offenders, or prosecuted for offences they have been forced to commit. We are also concerned that there is still not enough support for victims during modern slavery investigations and that, as a consequence, victims may be unwilling to engage with the police service and support such investigations. This is a significant factor which helps explain why few cases of modern slavery are prosecuted, and offenders remain free to continue to exploit vulnerable people.

1.2 Empowering victims of modern slavery

Because modern slavery is largely a hidden crime it is difficult to know the true scale of the problem. Understanding the police response from the victim’s perspective is also extremely difficult. We therefore think it is essential that further, co-ordinated work is undertaken across government departments, the police service, non-government organisations and the voluntary sector to gather and assess information on the experiences of victims and on outcomes for both victims and prosecutions. We have made an overarching recommendation to this effect.

We have also made recommendations to further improve learning for police officers and staff and to strengthen support mechanisms for modern slavery victims, so that these are easy to access in all police force areas and ensure victims feel safe and empowered to stay involved in investigations.

We believe these recommendations will complement the work already being undertaken by the Government and Devolved Administrations, as reported in the 2020 UK annual report on modern slavery. The Home Office invested just over £2m to continue to support law enforcement activity in 2020/21 under the new Modern Slavery and Organised Immigration Crime Programme. The main focus of the funding for 2020/21 was to support the police to continue its work on tackling modern slavery and help increase prosecutions, with the new focus on building capability to tackle organised immigration crime. Announcements on funding for the police for 2021/22 are awaited, following the publication of the New Plan for Immigration Policy Statement.

We are grateful to Hestia for raising these concerns. The findings and recommendations from this investigation, combined with the other important work that is already being undertaken, aim to ensure every victim of modern slavery gets the response they deserve. As a society, we have a duty to make this happen. We must do all we can to bring perpetrators of this terrible crime to justice.

2. Summary

2.1 What is a super-complaint?

A super-complaint is a complaint that “a feature, or combination of features, of policing in England and Wales by one or more than one police force is, or appears to be, significantly harming the interests of the public” (Section 29A, Police Reform Act 2002).

The system is designed to examine problems of local, regional or national significance that may not be addressed by existing complaints systems. The process for making and considering super-complaints is set out in the Police Super-complaints (Designation and Procedure) Regulations 2018 (the regulations).

For more information on super-complaints, see Annex B.

2.2 What does this super-complaint say?

This super-complaint raises several concerns about the police response to victims of modern slavery. These are:

- non-specialist police officers fail to recognise the signs of exploitation and fail in their duty to report modern slavery to the Home Office;

- police officers aren’t taking immediate steps to make a victim feel safe;

- victims of modern slavery are treated as immigration offenders;

- victims of modern slavery are treated as criminals when they have been forced to commit criminal activities by their exploiters, despite the existence of the section 45 defence in the Modern Slavery Act 2015;

- police forces don’t adequately investigate cases that come to their attention; and

- the adequacy of training provided to frontline officers.

The super-complaint relies on evidence from:

- Hestia’s analysis of witness statements;

- findings from the Home Affairs Select Committee on Modern Slavery;

- Freedom of Information requests sent to all police forces in England;

- interviews with Hestia keyworkers and service users; and

- supporting evidence from two legal expert organisations.

A recurring theme in Hestia’s super-complaint is the lack of effective support for victims. It says this lack of support, along with experiences of poor treatment, deters victims from engaging with investigations. In investigating this super-complaint, we have focused on the support the police are responsible for.

Hestia’s super-complaint recognises that progress has been made since the 2017 HMICFRS inspection of the police response to modern slavery, but concludes that until all police forces take a consistent approach to helping victims become witnesses, the number of prosecutions for modern slavery will remain very low, and exploiters will continue to victimise vulnerable people. Hestia is concerned that the lack of support also leaves victims at risk of returning to their captors and being exploited further.

2.3 Our approach and methodology

Our investigation into this super-complaint examined whether there is evidence that the concerns set out by Hestia are features of policing. We then considered whether there is evidence that they are, or appear to be, causing significant harm to the public interest.

The 2017 HMICFRS thematic inspection examined how the police in England and Wales were tackling modern slavery and human trafficking crimes. The methodology of that inspection is included as Annex C for reference. In summary, that inspection concluded that the police service had much to do to develop an effective, coherent and consistent response to modern slavery and human trafficking.

Our overall approach to investigating this super-complaint was to use the 2017 report as a benchmark, and to assess at a high level what progress has been made and whether, in light of any progress made, the concerns set out in the super-complaint are justified.

To achieve this we carried out a range of activities, including fieldwork in six forces, discussions with experts and organisations with extensive knowledge of modern slavery, and a review of information provided by police forces and other public bodies. Full details of our methods are set out below.

3. Our findings

Our findings are grouped under five areas

3.1 The approach taken by forces to planning and prioritising their responses to modern slavery

Based on our review of progress by policing against the recommendations of the 2017 HMICFRS inspection, forces have, overall, strengthened their approach to tackling modern slavery since the 2017 HMICFRS inspection. Senior leaders in the forces we visited indicated modern slavery was a priority. Many forces have improved their leadership and investigation capacity and provided training across a range of officer roles. And the number of investigations is increasing. The Modern Slavery Police Transformation Unit (MSPTU) – now the Modern Slavery and Organised Immigration Crime Unit (MSOICU) – overseen by the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) and funded through the Home Office, has supported police forces through providing expertise, training and guidance and has helped drive improvement in how forces respond to modern slavery.

3.2 The initial response to victims of modern slavery

Modern slavery can be difficult for non-specialist officers to recognise and remains a largely hidden crime. Its true extent in England and Wales is unknown and it is, therefore, extremely challenging to accurately assess how well crimes are identified and recorded, or the true extent to which police forces may be failing to identify victims. Our investigation found that the police approach to recognising and identifying victims of modern slavery has improved since the HMICFRS inspection in 2017, and that a lot more information has been provided to help officers recognise modern slavery. However, we also found that not all the officers we spoke with were aware of this information.

These findings, combined with the evidence provided by Hestia and others on the experiences of some victims’ first encounters with police, lead us to conclude that further improvements in the initial police response are needed. These improvements should build on the progress made since HMICFRS’s 2017 inspection.

Victims are also sometimes prevented from having access to support services by physical methods, such as being locked in premises. This means some cases will be missed and further improvements are needed to ensure all opportunities to identify victims are recognised.

Once victims had been identified, officers we spoke with showed good awareness of the importance of treating victims with sensitivity and respect to encourage them to engage, and they recognised the importance of keeping victims safe. However, we found the approach taken across forces to achieve this outcome is inconsistent, with few arrangements at a national level that could help. While some forces have arrangements to help victims, not all do, and not all officers we spoke with were sure what options were available to them.

We found some evidence to support the super-complaint concern that victims may not always be kept safe or made to feel safe, following their first contact with the police, and that this contributes to victims not engaging with the police service.

We found that non-specialist police officers’ understanding of the National Referral Mechanism and what it offers to victims is inconsistent, which means that some victims may not be referred when they should be.

3.3 How victims are treated for offences they have committed, including any immigration offences

Many victims of modern slavery are UK nationals or have a legal right to remain in the UK. But where victims of modern slavery are foreign nationals Hestia is concerned that some are treated as immigration offenders, rather than having the offences committed against them investigated. Our investigation did not find any intent on the part of the police service to deal with foreign national victims as immigration offenders rather than as victims of a crime. But, as we identified in our Safe to share? super-complaint report, police officers don’t always have clear priorities on how to safeguard victims balanced against their immigration enforcement responsibilities, and information is at times shared with the Home Office when the police suspect a victim may be an immigration offender. This deters victims from engaging with the police because they fear that immigration enforcement action will be taken against them.

The super-complaint also provides evidence to suggest that some victims are treated as criminals when they may have been forced to commit offences by their exploiters. Our findings show that some victims can have action taken against them for the offence they have committed, rather than be recognised as a victim of modern slavery. The protection from prosecution in these circumstances by applying the defence created by section 45 of the Modern Slavery Act 2015 is not always considered. Similarly, there are cases where the section 45 statutory defence has been abused. So there is a significant challenge to ensure that section 45 operates in such a way as to strike the correct balance between protecting genuine victims of trafficking/slavery from prosecution while preventing the wrongful acquittal of the guilty.

3.4 Investigations into modern slavery crimes

Our fieldwork and force responses to the recommendations in the 2017 HMICFRS report indicate that forces have (since 2017) improved their approach to investigating cases by using officers with the necessary skills and who have received training about modern slavery.

Although our investigation did not observe how victims were treated in practice, the investigating officers we spoke with clearly understood the importance of treating victims with sensitivity, keeping them safe and supporting them so that they continue to engage with the investigation. Nevertheless, we found evidence to support Hestia’s concern that there is a lack of initial and continuing support for victims during investigations. Police forces recognise the importance of supporting victims, and some forces have arrangements in place to achieve this.

Access to good quality support for victims is inconsistent across forces. Victims are not consistently receiving the support they are entitled to under the Code of Practice for Victims of Crime in England and Wales (the Victims’ Code[footnote 2] ) or being kept informed about the progress of their case as required.

This deters victims from continuing engagement with the police and supporting any investigation.

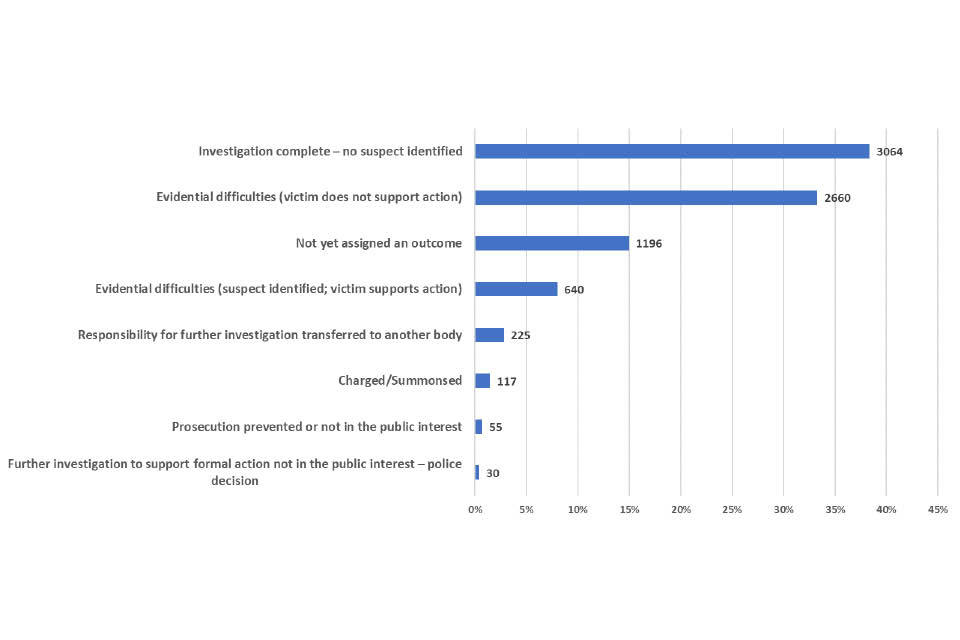

The number of prosecutions for modern slavery crimes is low. These crimes are complex and there are many barriers to achieving successful investigations that lead to cases being prosecuted. These include where victims do not support the investigation or having no named suspects to investigate. However, we found a clear commitment throughout the police service to increase the level of prosecutions to bring offenders to justice and joint work is underway aimed at achieving this outcome.

3.5 Training

The provision of training and guidance that is available nationally, and forces’ access to it, has increased significantly since 2017, especially for specialist officers. However, training across forces remains inconsistent, varying in scope and depth. While not all officers can be expected to have detailed knowledge, frontline officers need enough for their role so that they can recognise victims of modern slavery, keep them safe and consistently offer appropriate support.

4. Solutions

To improve outcomes for victims and the overall approach to tackling crimes of modern slavery, we have set out our recommendations.

4.1 Actions and recommendations

4.2 Actions

- The College of Policing will review and update their Authorised Professional Practice Major investigations and public protection on modern slavery as soon as possible and amend relevant content in other guidance as part of their regular updating processes.

- HMICFRS will consider how inspection activity can be used to further promote improvements in the investigation of modern slavery cases.

4.3 Recommendations

1. To the Home Office

a. In consultation with chief constables, the Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner, Victims Commissioners, the Crown Prosecution Service, voluntary agencies that provide support to victims, and others as appropriate, commission work to:

- better understand the victim experience of the police response to modern slavery and the wider response from immigration and other law enforcement agencies; and

- assess the extent and nature of poor victim experiences (from first contact with the police, through to investigation and prosecution stages where these occur) to understand and identify how they can be improved.

b. The work commissioned should seek to result in recommendations for specific actions that will further improve victims’ experiences. The Home Office should publish the findings of this work.

2. To chief constables

Assure themselves that police officers and staff (including non-specialist staff, as appropriate) are supported through access to learning, specialist policing resources and victim support arrangements, so that officers and staff are able to:

-

easily access information and advice on modern slavery and human trafficking through their force systems;

-

identify possible victims of modern slavery;

-

recognise that victims of modern slavery should not be treated as criminals in situations where they have been forced to commit an offence by their exploiters;

-

know how to take immediate steps to make victims feel safe (including facilitating access to a place of safety, if necessary);

-

understand how to advise victims what support is available them;

-

understand the National Referral Mechanism and duty to notify requirement, and know how to make good-quality referrals; and

-

ensure that the statutory defence (provided by section 45 of the Modern Slavery Act 2015) for victims of slavery and exploitation who are compelled or coerced into committing offences by their exploiters is considered in all cases to protect victims from prosecution.

3. To chief constables

Assure themselves that their resources are being deployed to enable effective investigation of modern slavery offences (which may, for example, involve taking account of high levels of vulnerability and organised crime group involvement). They should assure themselves that their crime allocation processes direct investigations to the most appropriately skilled individuals and teams.

4. To chief constables, and police and crime commissioners

Work together to understand the support needs of victims of modern slavery crimes. They should provide appropriate support within their respective remits to augment the national provision so that victims feel safe and empowered to remain involved in any investigations. This should focus on what support should be available before and after National Referral Mechanism (NRM) referral as well as alternative provision available for those declining NRM referral.

5. To the Home Office

Assure themselves that the support mechanisms provided by bodies under government funding are consistently making available high-quality provision for victims of modern slavery.

6. Monitoring of recommendations

a. Home Office to provide a report to Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Constabulary on progress in implementing its recommendations within six months of the date of publication of this report.

b. National Police Chiefs’ Council to collate Chief Constables’ progress in reviewing and where applicable implementing their recommendations and report these to Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Constabulary within six months of the date of publication of this report.

c. Association of Police and Crime Commissioners to collate Police and Crime Commissioners’ progress in reviewing and where applicable implementing their recommendations and report these to Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Constabulary within six months of the date of publication of this report.

5. Background and legal framework

Modern slavery encompasses a range of crimes of exploitation. It includes, but is not limited to, human trafficking, sexual exploitation, forced labour, domestic servitude, criminal exploitation, forced marriage, organ removal and fraud.

The number of NRM referrals can be used as a potential measure to estimate the scale of modern slavery. However much larger estimates exist. For example, the Centre for Social Justice and Justice and Care, in their report It still happens here: fighting UK slavery in the 2020s, estimated that there could be at least 100,000 victims of modern slavery in the UK in 2017.

5.1 Government’s approach

The Modern Slavery Strategy 2014 sets out the Government’s approach to tackling this crime. Its aim is “to reduce significantly the prevalence of modern slavery in the UK, as well as to enhance our international response”. It uses the framework of the 4 Ps – pursue, prevent, protect and prepare – to set out the actions required. The Government produces annual reports to assess the progress made against the strategy. The most recent report was published in October 2020 [footnote 3].

In March 2021 the Government published its New Plan for Immigration Policy Statement. This announced a review of the Modern Slavery Strategy 2014 and set out proposals to improve support for victims of modern slavery. The New Plan includes changes to ensure that victims of modern slavery receive the support they need to engage in the criminal justice system. The Government will also be looking at how to improve support for victims of modern slavery to participate effectively with police investigations. The Government has also committed to providing specialist mental health support to victims. It will be consulting on a revised strategy.

5.2 Modern slavery legislation

The Modern Slavery Act 2015 consolidated existing slavery and human trafficking offences in England and Wales. The Act provides an enhanced legal framework for law enforcement agencies to pursue and bring perpetrators to justice. It introduced two provisions to better protect victims:

- a statutory defence for victims of modern slavery who have been compelled to commit an offence as a result of their exploitation, or in the case of under 18s that the offence is a direct consequence of their being or having been a victim of modern slavery (the section 45 defence); and

- two types of preventative orders to safeguard victims.

Slavery and Trafficking Prevention Orders and Trafficking Risk Orders act as a protective tool. The purpose of the Slavery and Trafficking Prevention Orders is to prevent slavery and human trafficking offences being committed by someone who has already committed these offences. Slavery and Trafficking Risk Orders can be made by a court after a conviction, or in respect of an individual who has not been convicted of a slavery or trafficking offence. The Court must be satisfied that there is a risk that the defendant may commit a slavery or human trafficking offence and that the order is necessary to protect against the risk of harm from the defendant committing the offence. Both orders place restrictions on people considered likely to exploit victims and commit modern slavery offences and they help to keep victims safe. Victims don’t have to give evidence in person. Instead, evidence can be presented as hearsay.

The Act also introduced a requirement for first responder organisations (of which the police are one) to notify the Home Office when they encounter someone they believe to be a victim of modern slavery. In all cases involving children, and in cases of consenting adults, this is done by referring suspected victims of modern slavery into a framework for support called the National Referral Mechanism (NRM). This requirement is known as the duty to notify. In the case of adults this is by consent. So that victims can give their informed consent, the referring organisation must explain what the NRM is, what support is available through it and what the possible outcomes are for the individual.

When an adult does not consent to be referred into the NRM and there are grounds to believe that person is a victim of modern slavery or trafficking, first responders, including the police, have a duty to notify the Home Office anonymously (section 52 Modern Slavery Act 2015). This is completed through the same digital portal as an NRM referral.

Children identified as possible victims of modern slavery must be referred for support under the NRM.

All referrals made into the NRM are considered by the Single Competent Authority through a two-stage process. This comprises a unit of trained specialists within the Home Office.

Following a referral from a first responder organisation, the Single Competent Authority first makes an initial reasonable grounds decision to determine whether it suspects but cannot prove that an individual is a potential victim of modern slavery. The Single Competent Authority then goes on to make a conclusive grounds decision to determine whether on the balance of probabilities there are sufficient grounds to decide that the individual is a victim of modern slavery.

Following a positive reasonable grounds decision, adult victims enter the recovery period. The recovery period is provided for a minimum of 45 days, or until the conclusive grounds decision is made, whichever is the longer. During the recovery period support is available, including accommodation, financial support and medical care.

Following a positive or negative decision at the conclusive grounds stage, a period of move-on support is provided, with the length of time determined by the outcome of the decision [footnote 4].

The Modern Slavery Act 2015 was independently reviewed in 2016 – this is known as the Haughey review.

This review found that law enforcement agencies were using the powers in the Act to increase prosecutions and support victims. But it also found that there could be more consistency in dealing with victims and perpetrators. This included better training and a more structured approach to identifying, investigating, prosecuting and preventing modern slavery.

In July 2018, the Government commissioned Frank Field MP, Maria Miller MP and Baroness Butler-Sloss to undertake an independent review of the Modern Slavery Act 2015. Their report, Independent Review of the Modern Slavery Act 2015: Final Report, published in 2019 considered the operation and effectiveness of the Act and suggested potential improvements. In particular, it focused on four topics: transparency in supply chains, the role of the Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner, the Act’s legal application and the safeguarding of child victims of modern slavery. The review identified severe deficiencies in how data on modern slavery is collected. It also found there needs to be greater awareness of modern slavery and consistent, high-quality training among those most likely to encounter its victims. The review made various recommendations for improvements.

In January 2020, Lord McColl’s Modern Slavery (Victim Support) Bill was introduced in the House of Lords. The Bill aims to significantly improve support for modern slavery victims throughout England and Wales. It proposes to give victims at least 12 months of support after a conclusive grounds decision. At the time of writing this report, the Bill is still proceeding through Parliament.

6. The Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner

The role of the Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner is to encourage good practice in tackling modern slavery throughout the UK. The priorities in her strategic plan for 2019–21 are to:

- improve victim care and support;

- support law enforcement and prosecution;

- focus on prevention; and

- get value from research and innovation.

Hestia’s super-complaint focuses on the first two of these priorities.

In September 2020, the Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner published an annual report which outlined progress against her 2019–21 strategic plan [footnote 5].

7. Anti-Slavery Co-ordinator for Wales

The role of the Anti-Slavery Co-ordinator for Wales is to stop slavery in Wales and to co-ordinate help and support for survivors.

The Wales Anti-Slavery Leadership Group aims to tackle slavery in line with the Home Office’s Modern Slavery Strategy. The objectives in their delivery plan 2021–22 are to:

Pursue - ‘Prosecute and disrupt individuals and groups responsible for slavery’

- Strategic objective 1: In Wales to increase investigations and prosecutions of modern slavery offences

Prevent - ‘Prevent people from engaging in slavery’

- Strategic objective 2: Tackling child exploitation

- Strategic objective 3: Preventative measures to tackle labour exploitation in Wales

Protect - ‘Strengthen safeguards against slavery by protecting vulnerable people from exploitation and increasing awareness of and resilience against this crime’

- Strategic objective 4: Improve awareness and availability of information on slavery

Prepare - ‘Reduce the harm caused by slavery through improved victim identification and enhanced support’

- Strategic objective 5: To develop and deliver consistent anti-slavery training

- Strategic objective 6: Wales Modern Slavery Safeguarding Pathway

- Strategic objective 7: Working with ‘source countries’

8. Modern Slavery Police Transformation Unit

In 2017, the Modern Slavery Police Transformation Unit (MSPTU) was set up following a bid for £8.5m from the Police Transformation Fund. The aim of the MSPTU was to transform the policing response to slavery and trafficking, and address both shortcomings identified by the Haughey review and the concerns raised through the work of the NPCC modern slavery and organised immigration crime portfolio.

The MSPTU developed and provided considerable training, guidance and support to help the police service respond more effectively to modern slavery. The funding for the MSPTU ended in March 2020 and a new unit is now funded directly by the Home Office for 2020/21. The new unit is called the Modern Slavery and Organised Immigration Crime Unit (MSOICU). The NPCC lead for modern slavery, the Chief Constable of Devon and Cornwall Police, is responsible for overseeing the work of the unit. Stakeholders told us the MSPTU and MSOICU have had a critical role in supporting improvements. Given the unit’s funding is temporary, we would encourage thought to be given to how to retain this capability in the longer term.

9. College of Policing guidance

The College of Policing Authorised Professional Practice (APP) on Major investigations and public protection includes detailed guidance on modern slavery. The College of Policing is aware the document needs to be updated. The guidance reflects the importance of recognising the traumatic effect of modern slavery on victims and the fears victims may have about disclosing possible crimes committed against them. The guidance recognises the importance of safeguarding victims.

10. HMICFRS inspections

In July 2016, the Home Secretary commissioned HMICFRS to inspect the police response to the implementation of the Modern Slavery Act 2015 in England and Wales. The inspection took place between November 2016 and March 2017 and included fieldwork in ten forces. As part of the inspection HMICFRS examined data and self-assessments from all 43 forces in England and Wales and reviewed 92 concluded and current cases. Further fieldwork was carried out in four regional organised crime units and the National Crime Agency.

The inspection findings were published in Stolen freedom: the policing response to modern slavery and human trafficking, HMICFRS, 2017. The inspection found widespread inconsistency in how law enforcement had responded to the Act, and to modern slavery and human trafficking more generally. This resulted in poor outcomes for many victims. It also showed that non-specialist officers and staff often had a limited understanding of modern slavery, and the powers and provisions set out in the Act. Investigators, too, had little understanding of the section 45 defence. There was limited use of the new preventative powers and there were few notifications to the Home Office where officers and staff suspected someone might be the victim of modern slavery.

Recommendations were made to police forces and law enforcement agencies to improve the approach to tackling modern slavery. HMICFRS routinely monitors the progress forces make against recommendations, and the results are referred to where relevant in this report. We have referred to progress against the relevant recommendations to inform our findings for this investigation.

11. Our super-complaint investigation

11.1 Scope

Our investigation considered whether there is evidence that the concerns set out by Hestia are features of policing. We then considered whether there is evidence that they are, or appear to be, causing significant harm to the public interest. This includes:

- whether there is evidence that the issues of concern are widespread;

- whether they are adversely affecting the identification and investigation of modern slavery crimes, and

- the extent to which there is evidence that they may be affecting the police’s ability to keep victims safe and provide them with adequate support.

To assess how the police response to modern slavery has changed since the 2017 HMICFRS inspection, we have considered progress by all forces against the recommendations of that report. We have also used the evidence from victims’ experiences described in the super-complaint, along with case examples provided by victim support organisations we contacted, to inform our investigation. While it is extremely challenging to determine the extent to which these victims’ experiences are representative, these accounts have proved invaluable in understanding concerns from victims’ perspectives.

11.2 Methodology – how we investigated the super-complaint

Although Hestia’s super-complaint relates to English police forces, we extended our investigation to include Wales because there was no evidence to suggest the situation in Wales would be any different from that in England.

We analysed and grouped the concerns set out in the super-complaint and developed the following lines of enquiry:

- the approach taken by forces to planning and prioritising their responses to modern slavery;

- the initial response to victims of modern slavery;

- how victims are treated for offences they have committed, including any immigration offences;

- investigations into modern slavery offences; and

- training on identifying, dealing with and understanding the traumatic effect of exploitation on victims of modern slavery.

To gather evidence, the investigation team:

- held discussions with experts and organisations who have extensive knowledge and understanding of modern slavery and human trafficking (see Annex D);

- carried out intensive fieldwork in six forces (Cambridgeshire, Cheshire, Kent, Merseyside, South Wales Police, Sussex), including focus groups with officers, discussions with individual officers and staff such as those in call centres and on front desks at police stations, and interviews with senior leaders and specialists;

- critically reviewed information on modern slavery supplied by forces, such as local policies and guidance, and interviewed officers in several forces;

- considered inspection reports and other inspection evidence, including HMICFRS crime data integrity reports, which examine how accurate forces are in recording crimes and incidents reported to them;

- considered the findings of HMICFRS’s continuing monitoring of forces’ progress against the recommendations in the 2017 modern slavery thematic inspection;

- examined submissions and documents provided in response to our enquiries to public bodies and other agencies; and

- examined information gathered from victim support organisations about their experiences of police contact with victims.

Additionally, the IOPC reviewed its cases to identify relevant investigations and whether any learning was relevant to inform this super-complaint investigation. See Annex E for the full details.

Annex F provides information on the data sources referenced in this report.

The three decision-making authorities – HMICFRS, the College of Policing and the IOPC – collaborated throughout the investigation.

12. Our findings

12.1 Approach taken by police forces to planning and prioritising their responses to modern slavery

To give context to the super-complaint concerns, we include a high-level overview of the police response to HMICFRS’s 2017 inspection report: Stolen freedom: the policing response to modern slavery. This report recommended that:

forces should review their leadership and governance arrangements for modern slavery and human trafficking, to ensure that:

- senior leaders prioritise the response to modern slavery and human trafficking;

- every incident of modern slavery identified to police is allocated appropriate resources with the skills, experience and capacity to investigate it effectively;

- forces develop effective partnership arrangements to co-ordinate activity in order to share information and safeguard victims; and

- performance and quality assurance measures are in place to allow senior leaders to assess the nature and quality of the service provided to victims.”

The findings from this super-complaint investigation indicate some progress against this recommendation. In January 2020, the MSOICU contacted forces to determine the resources given to modern slavery. All forces have dedicated specific points of contact for modern slavery. Forces have also taken steps to have appropriately trained and skilled investigators for cases involving modern slavery. And they have partnership arrangements to exchange information and co-ordinate preventative and enforcement activities. According to the MSOICU’s research conducted in January 2020, just over half of all forces have governance and performance management mechanisms to oversee their response to modern slavery and to help ensure sufficient resources to deal with it.

12.2 Prioritising the response to modern slavery

From our discussions with senior leaders during the super-complaint investigation, and review of force material, it was clear that forces see modern slavery as a policing priority and most include it in their strategic assessment for their policing area.

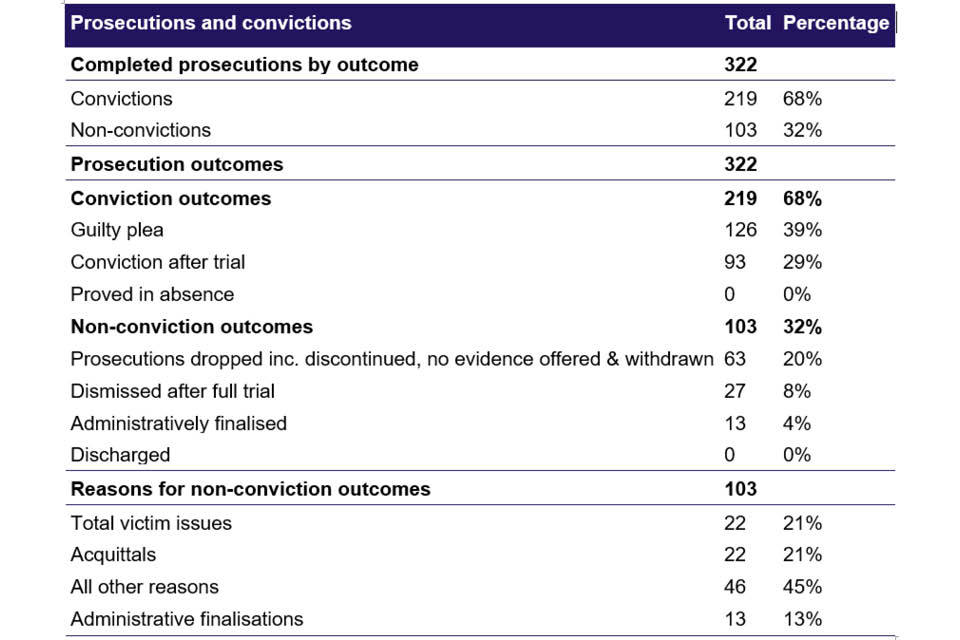

Forces are also taking a more targeted approach to modern slavery through proactive operations, including where offences are perpetrated by organised crime groups. There was an increase in completed prosecutions for flagged modern slavery prosecutions from 294 (for year ending December 2018) to 349 (for year ending December 2019). This includes defendants prosecuted for a Modern Slavery Act 2015 offence as well other serious criminal offences (including conspiracy to commit Modern Slavery Act 2015 offences)[footnote 6].

12.3 Use of preventative powers

The 2017 HMICFRS inspection report also recommended that:

forces should review their use of preventative powers under the Modern Slavery Act 2015 to ensure that opportunities to restrict the activities of those deemed to pose a clear threat to others in respect of modern slavery and human trafficking offences are exploited[footnote 7].

According to the 2020 UK annual report on modern slavery, 147 Slavery and Trafficking Prevention Orders and 60 Slavery and Trafficking Risk Orders were issued between July 2015 and March 2020 in England and Wales.

Thirty-two forces have used the preventative powers made available in the Modern Slavery Act 2015 and obtained orders against offenders. But use of these powers varies across forces. Some forces work with partner agencies to secure prevention orders using other legislation when the 2015 modern slavery legislation isn’t appropriate. Since the super-complaint was made, these orders are now being used more in county lines cases.

In August 2020, the MSOICU did a force review and found that there is still no national consistency for the recording, monitoring or management of modern slavery orders, however a number of forces were making attempts to make improvements. Only 16 forces had an established structure for the recording and management of modern slavery orders.

As a result of its review the MSOICU developed guidance to advise and support forces to understand how to apply for, record and manage modern slavery orders.

12.4 The initial response to victims of modern slavery

Hestia said:

“Some witnesses testified that police officers continue to display a lack of understanding of modern slavery and often fail to recognise signs of exploitation and adequately respond to victims of modern slavery. This extended to a lack of understanding of the National Referral Mechanism (NRM) and of the duty to notify the Home Office when a potential victim is identified.”

Underground lives: Police response to victims of modern slavery, Hestia, March 2019

Most of the police officers and staff we spoke with during our fieldwork recognised that modern slavery was a strategic priority for their force, and knew about the importance of identifying and dealing with these crimes. They also showed a good understanding of the signs to look for and talked about different types of modern slavery that might be present in the areas where they worked. Some forces, for example, described local cases of domestic slavery; others told us about enforced labour in places like nail bars or cleaning businesses.

Some officers had been briefed about modern slavery to help them understand it better. But most frontline officers we spoke with recognise this is a complex area, and said they would seek advice and guidance from their force’s specialist team or single point of contact (SPOC) for modern slavery to help them respond to any cases they encountered.

For this to work, officers must of course have at least a basic grasp of the signs of modern slavery, so they can identify that they should talk to their SPOC about a particular case. We therefore looked at the information provided to officers to assist with this.

12.5 Sources of information

Information to support officers and help them deal with cases of modern slavery varies in quality and ease of access by force. The six forces we visited made information available on their intranets about how to identify and deal with victims of modern slavery, and officers could access it on their hand-held devices. But whereas officers could easily find and navigate some sites, some officers told us they struggled to find the information, despite extensive searching.

Good quality and easy to access information is very important in helping officers identify and respond to victims of modern slavery. It is essential that officers and staff know where they can refresh their knowledge and find information, particularly out of hours. The MSPTU helped forces improve their intranet sites by providing an intranet pack. This makes guidance and other material readily available to police officers and staff. It is an example to forces of what they could include on their own sites.

There is comprehensive College of Policing APP guidance and a range of other national guidance to help frontline officers identify modern slavery and deal with cases. The College is aware this needs to be updated. The MSPTU developed a pocket-sized guide called Modern slavery initial actions. A guide for the frontline. This is aimed at helping frontline staff to spot victims and respond effectively. It contains a brief overview of the law, signs that someone may be enslaved, first investigative actions, the NRM and safeguarding. It explains that the person may not view themselves as a victim of modern slavery and why therefore there is a need to gain their trust. But few officers we spoke with were aware of this guide; fewer still had the guide to hand. The MSPTU also produced a first contact booklet that highlights best practice from forces. It is designed to guide frontline officers and staff to consider relevant factors and to help them in questioning someone they believe may be a victim of trafficking. It also provides guidance on gathering relevant information during modern slavery investigations.

These guides, along with other guidance material covering various aspects of slavery and trafficking, are shared through the Policing Slavery and Human Trafficking Group on the College of Policing Knowledge Hub. This has been advertised to all forces as the primary location to download updates and new material to their individual sites. This is an IT platform funded through the network of police and crime commissioners.

Non-specialist frontline officers and staff are the first point of contact with the public, victims and suspects. Our discussions with staff showed some good awareness of the signs of modern slavery, but these are often complex cases and modern slavery may not be immediately evident. There is therefore a risk of cases not being identified or referred to specialist officers.

The College of Policing has developed vulnerability training that includes modern slavery case studies and is available to all forces. The training seeks to support police officers and staff to recognise the personal factors of vulnerability that may affect an individual and how they interact with the environment to cause harm or the risk of harm. The more traditional approach to policing vulnerability has focused on particular issues, such as mental ill-health, age, race and religion. In reality, most people encountered by policing have several vulnerabilities and the task for police responders, along with others, is to seek to manage the situation so that the identified vulnerabilities do not lead a person to suffer harm. In the case of modern slavery, victims may be vulnerable for a range of reasons, such as isolation from support, because they have no support network, no family nearby and English may not be their first language. In addition, however, they may have uncertain or insecure immigration status. Police responses must recognise all relevant vulnerabilities and work with others to create a package of measures to support the individual to prevent or reduce the risk of harm.

Further improvements are needed in the police response to modern slavery, but there are signs that the police’s ability to recognise victims of modern slavery has improved since the HMICFRS inspection in 2017. This is reflected in the increasing number and accuracy of the crimes recorded.

12.6 Crime recording

The available data from police records of modern slavery crimes provides a source of information on whether police identification of modern slavery is improving. The HMICFRS 2017 modern slavery inspection raised concerns about the accuracy of the recording of modern slavery crimes and recommended that:

forces should take steps to ensure they fully comply with national crime recording standard (NCRS) requirements for offences identified as modern slavery and human trafficking and that sufficient audit capacity is available to the force crime registrar to provide reassurance that each force is identifying and managing any gaps in its crime-recording accuracy for these types of offences[footnote 8].

Between April 2016 and February 2020, as part of the rolling programme of crime data integrity inspections, HMICFRS reviewed (non-representative) samples of modern slavery cases and NRM referrals. The aim was to understand the quality and consistency of crime recording decisions in this area. Findings from these inspections showed an improvement over the period in patterns of crime recording for modern slavery, with most identified crimes accurately recorded by most forces.

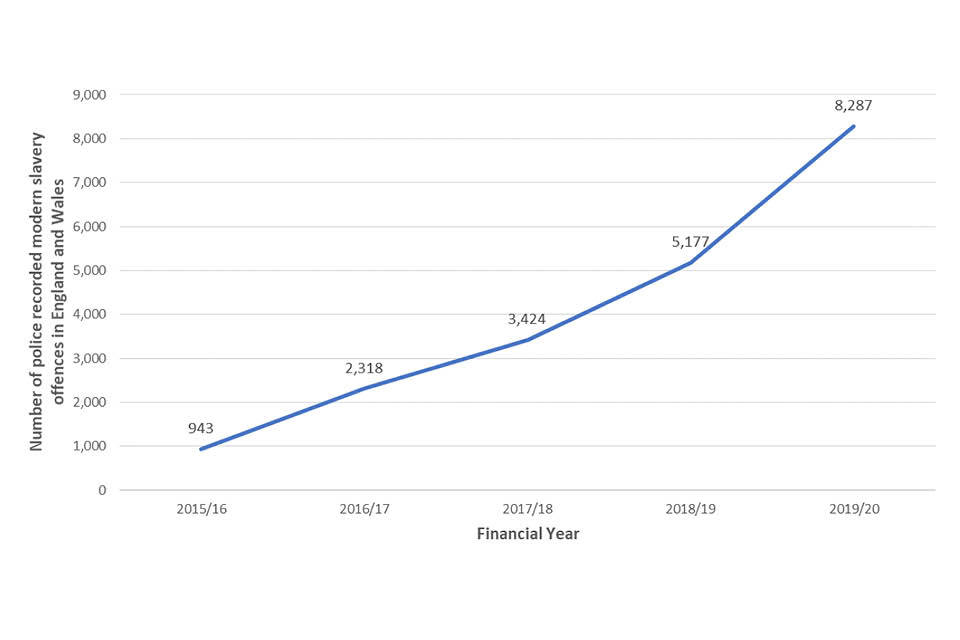

This improvement is reflected in the marked increase in the police recording of crimes of modern slavery since 2015/16, as shown in the chart below. There have also been just over 4,000 modern slavery police recorded crimes in the first two financial quarters in 2020/21. However, it is worth noting that some of the increase may have been driven by an increase in the prevalence of modern slavery over this period.

Figure 1: Police recorded modern slavery offences in England and Wales, 2015/16 to 2019/20

Source: Home Office Police Recorded Crime

Summary finding:

Modern slavery can be difficult for non-specialist officers to recognise and remains a largely hidden crime. Its true extent in England and Wales is unknown and it is, therefore, extremely challenging to accurately assess how well crimes are identified and recorded, or the true extent to which police forces may be failing to identify victims.

Our investigation found that the police approach to recognising and identifying victims of modern slavery has improved since the HMICFRS inspection in 2017, and that a lot more information has been provided to help officers recognise modern slavery. However, we also found that not all the officers we spoke with were aware of this information.

These findings, combined with the evidence provided by Hestia and others on the experiences of some victims’ first encounters with police, lead us to conclude that further improvements in the initial police response are needed. This should build on the progress made since HMICFRS’s 2017 inspection.

12.7 Initial treatment of victims

The police officers and police staff we spoke with understand the importance of dealing with victims sensitively and making them feel comfortable in discussing their circumstances. They described making sure they spoke with people where they couldn’t be overheard. Some officers understand the term ‘alpha victim’, where one enslaved person may be dominant among the victims, and how essential the privacy of their first conversation needs to be.

The officers we spoke with also recognised the importance of arranging for an independent person to act as an interpreter if needed, rather than someone who might be present with the potential victim and known to them. They described using telephone-accessed interpreter services and applications on their mobile phones or hand-held devices to maintain this independence, even if these methods could feel clunky and impersonal.

We found some officers are aware of the need to ask a wide range of questions to establish the victim’s circumstances and possibly indicate whether they are being exploited. They might ask how they had arrived in the country, or about their living conditions, rent or any other payments they have to make, their financial independence, any wages paid to them, their passports and their general wellbeing.

Some of the experiences described by Hestia in their super-complaint show that the victims were poorly treated and shown a lack of respect by police officers, and that these victims didn’t feel believed. The agencies we spoke with also gave examples of this happening. The following two examples are taken from the super-complaint:

12.8 Afghan victim of forced labour

“My client had escaped a forced marriage situation in which her husband was also forcing her to work without pay in his factory. She did not have the right to work in the UK when this was taking place. The husband was already in prison for a different offence when she decided to give a statement about the forced labour exploitation. When we went to the police station, the receptionist straight up told us ‘this isn’t modern slavery’. She hadn’t even heard my client’s case. Later, whilst my client was giving her statement, the officer interviewing her was very patronising. When my client said she had been forced to work against her will, the officer asked her if her husband had given her food to eat. My client said yes. The officer responded ‘did you expect to come to the UK to be a kept woman?’ In the end they told her it was an employment issue and had nothing to do with them.”

- Hestia keyworker

12.9 Personal account: escaping from sexual exploitation in East London

“I was pregnant with one baby when I managed to escape. It was very cold and I realized I had nowhere I was running to. I felt I needed to go to a police station because I couldn’t trust anyone. On the streets, I met a Nigerian lady who helped me. She gave me an oyster card so I could travel on the bus. She led me to a police station. When I arrived, I rang the buzzer and they asked me who I was. It was freezing cold and I was in shock. I couldn’t talk much. A man and a woman came out. They took my details. Inside the station, the woman left us alone, she said she needed to check something. The man started interrogating me. He questioned everything I told him. How can you say you’re running away if you have a coat on? Is it this cold in Nigeria? I told him I grabbed a coat that was by the door when I escaped but he didn’t like my answer. How come it fits so well? How come you have warm clothes for your son? He even questioned why I spoke English. He said they don’t speak English in Africa. I said we speak English in Nigeria. He didn’t believe me.

He then started searching me. He emptied my bag and took out every item. He made me empty out my pockets and take off my shoes. It was so traumatizing I cannot remember it all. He said he’d throw me out if I didn’t tell the truth. He shouted at me to speak up. When I asked him to slow down because I didn’t understand him, he accused me of insulting him. The officer at the counter was rude to me too. He told me to get up and told the other man to search me. The woman came back. She said she had spoken to the Home Office and they had told her they’d find me a place to stay. Two hours later, they came to take me somewhere safe. Those people were nice. I didn’t want to complain after that, I didn’t want anything to do with the police. That’s why I didn’t report my case.”

These accounts detail victims who have been treated poorly by the police and deserved better. Whilst we have not investigated these specific incidents, the evidence presented in the super-complaint indicates that some victims have been poorly treated by the police.

12.10 Summary finding:

Our investigation has found that, while the police officers we spoke with demonstrated supportive attitudes and awareness, the evidence presented in the super-complaint shows that some victims have been poorly treated by police officers. When we spoke with frontline officers and investigators, they showed compassion towards victims and an understanding of the effect that modern slavery has on them. However, we recognise that we did not observe how these officers dealt with cases in practice.

The victims’ voices in the case examples provided by the super-complaint are clear and troubling. Because of the hidden nature of modern slavery and the limitations of this investigation, we have not been able to determine the extent to which these poor experiences are representative of all modern slavery victims, or indicative of a widespread problem.

12.11 Keeping victims safe

The super-complaint includes examples of cases where forces didn’t take immediate steps to make victims feel safe. This affected victims’ willingness to disclose information and offences to the police.

Keeping victims safe is a main responsibility for the police, as stated in the College of Policing APP guidance on modern slavery. In June 2020, the College of Policing revised its published advice for first responders on the duty to notify and the NRM process. In addition, a revised bespoke e-learning package focusing specifically on safety, protection and the NRM process was published in June 2020.

HMICFRS’s inspections across the range of police force activities find that safeguarding vulnerable people is generally well understood by police officers and staff throughout England and Wales and has significantly improved in recent years. Dealing with vulnerability and making people safe is now more prominent as a main police function, and stems from greater focus on crimes such as domestic abuse, serious sexual assault, and child and adult abuse. County lines offending[footnote 9] has also increased the knowledge of officers about trafficking vulnerable people, and why they require very particular safeguarding.

In our discussions with frontline staff, we found a good understanding of the need to keep victims of modern slavery safe. Some officers described the actions they had taken when they came across suspected victims in the course of their duties. Most of the officers understand that many victims won’t initially trust those involved in law enforcement. They are aware of the need to build rapport and make sure victims feel safe so that they can find out what had happened to them.

Some frontline officers know about the short-term local arrangements available to house victims away from where they have been enslaved. This is usually in hotels or bed and breakfast accommodation. They also understood the need to make sure victims have food and clothing available. But although specialist officers know about the options available, not all frontline officers did. In addition, some forces didn’t have any such arrangements in place. In these circumstances, officers reported they had to take suspected victims to a police station initially.

In some forces, officers and staff have had training from local agencies and have contact details for agencies that can help to safeguard victims in the very early stages of identification and investigation. Some forces also have the benefit of safe houses in their area, where victims can be accommodated and get the right support before support is provided under the NRM. Safe houses aren’t common, however, and bed and breakfast or hotel accommodation isn’t always a suitable option for vulnerable victims, even as an interim measure.

It has been recognised nationally that better arrangements are needed at both local and national levels to give victims safe and suitable places to go. In June 2020, a new Modern Slavery Victim Care Contract (MSVCC) was awarded by the Government to The Salvation Army, the prime contractor. The new service went live in January 2021 and builds on the wide-ranging support of the previous Victim Care Contract to provide a service that is needs-based and better aligned with the requirements of individual victims in England and Wales. Partnership working is an important theme throughout the new MSVCC to ensure a co-ordinated approach to supporting victims of modern slavery. This includes the Government working with law enforcement partners to ensure victims receive the right level of support as quickly as possible, including emergency accommodation when required.

12.12 Summary finding:

Our investigation found that victims may not always be kept, or made to feel, safe following their first contact with the police. Forces recognise the importance of keeping victims safe, and there has been more guidance and information made available on this since 2017. However, the inconsistent approach across forces, the lack of accommodation provision in some areas and the testimony from victims lead us to conclude that victims may be deterred from engaging with the police service and/or supporting any investigation and prosecution.

12.13 Referrals under the National Referral Mechanism and the duty to notify

HMICFRS’s 2017 report, Stolen freedom: the policing response to modern slavery, recommended that:

forces should take steps to ensure they are fully compliant with the NRM process as it evolves and are implementing the requirement placed upon them under the Modern Slavery Act 2015 to notify the Home Office of any individual suspected to be an adult victim of modern slavery or human trafficking.

The findings from our super-complaint investigation indicate that progress has been made against this recommendation, but there remains room for improvement.

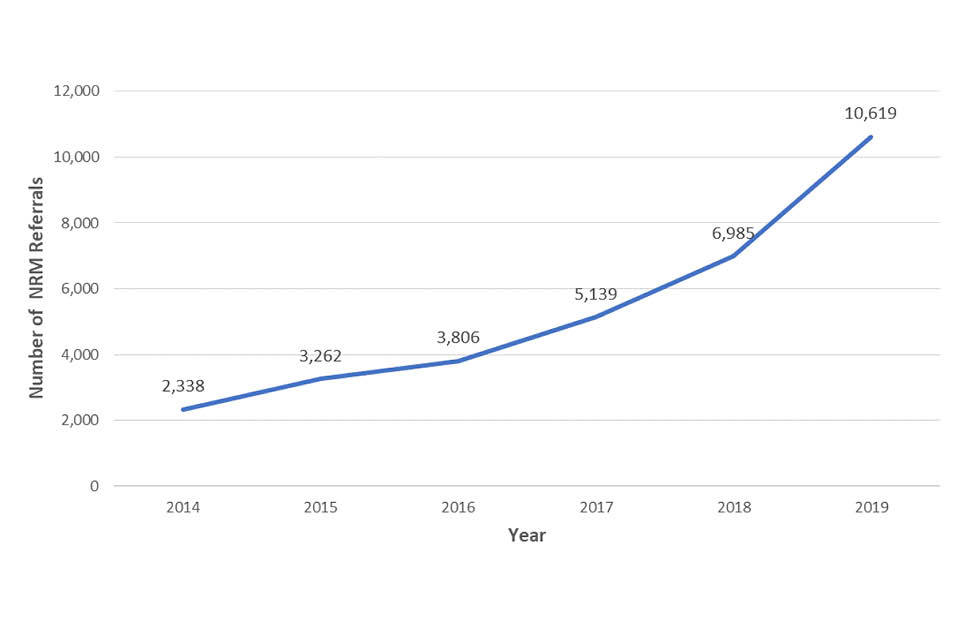

There has been a yearly increase in referrals since the NRM was introduced. Between 2018 and 2019, the number of NRM referrals throughout the UK increased by 52 percent, from 6,985 to 10,619. There have also been 7,576 NRM referrals in the first three quarters of 2020. According to the National Referral Mechanism statistics UK end of year summary 2019, around a quarter of NRM referrals came from the police (and the rest from other statutory and non-statutory agencies designated as first responders) in 2019; around 30 percent came from the police in 2018.

Children make up almost half of all referrals, according to the National Referral Mechanism statistics UK end of year summary 2019. Around 43 percent of referrals were for children in 2019; this is similar to the proportion seen in 2018.

The 2020 UK annual report on modern slavery suggests the increase in referrals could be because of greater awareness, although it notes that it cannot rule out increases in the incidence of offences.

Figure 2: Referrals to the National Referral Mechanism in the UK, 2014 to 2019

Source: Home Office National Referral Mechanism Statistics

Forces we assessed in our fieldwork told us that they provide officer awareness training or written guidance about the NRM process. They have systems and processes to make sure victims of modern slavery are identified and referred appropriately. Some forces use specialist teams or individuals to screen NRM referrals so that information is shared and an appropriate police response is put in place. Some forces actively monitor NRM referrals to assess their performance to show how well they comply with the requirements. An increase in NRM completions can indicate that awareness of modern slavery and NRM is increasing in the workforce.

The MSPTU supported police forces to build workforce understanding of the duty to notify and referrals to the NRM, so that suspected victims get accurate information about where and how they can access support.

The College of Policing has approved training on making and dealing with referrals. This includes a video describing the role of police as first responders, the expectations of them, including in safeguarding victims, and the support offered through the NRM. This training is available through the College of Policing’s managed learning environment. The training video has been viewed 130,000 times; this is likely to be an underestimate of the number of people who have viewed it because some forces will use the video to support provision of learning to groups of officers and staff.

However, the non-specialist officers and staff we spoke with didn’t all know about the duty to notify and referral arrangements under the NRM. Few frontline officers were aware of the processes to be followed, what it meant for the victim or the support the victim might get if referred. Some officers knew about online referral, but most didn’t know where a referral went or what happened to it. Most said that they wouldn’t complete the form themselves but that someone else in their force with more specialist knowledge would do it.

We spoke with The Salvation Army about the quality of NRM referrals it gets from the police. It told us the level of detail provided was inconsistent, both between and within forces. Some referrals include comprehensive information, whereas others provide very limited detail. The Salvation Army NRM referrals team told us that they often make repeated calls to the police to get enough detail for victims to be properly referred. This was also the case for referrals from other first responders and wasn’t unique to the police. The team felt there was a lack of understanding by police officers about the role and the support offered by The Salvation Army, and the information needed to make sure referrals were appropriate.

Our investigation suggests that officers are getting better at recognising victims of modern slavery. But these cases can be difficult to identify, and inconsistent understanding of the NRM may lead to cases not being referred. Our discussions with officers didn’t give us confidence that victims would always be referred to the NRM.

At the time of writing this report, the Government announced its New Plan for Immigration. Proposals within the Plan include improving the training given to first responders, who are responsible for referring victims into the NRM. In the light of our finding, we welcome this new initiative.

12.14 Summary finding:

The steady increase in referral numbers since HMICFRS’s 2017 inspection suggests that police forces are better at identifying modern slavery and understanding the need to refer via the NRM. But since we don’t know the true number of modern slavery victims, we can’t assess the extent to which forces are referring victims to the NRM. Our fieldwork found evidence of a lack of knowledge among officers, and this suggests that some victims may not be referred when they should be.

12.15 How victims are treated for offences they have committed, including immigration offences

Hestia said:

“Victims of modern slavery are treated as immigration offenders. … Victims of modern slavery are treated as criminals when they have been forced to commit criminal activities by their exploiters, despite the existence of the section 45 Defence in the Modern Slavery Act”.

Hestia – Underground lives: Police response to victims of modern slavery March 2019

Hestia provided evidence from expert witnesses and case examples where victims have been treated as immigration offenders. Some have been held in immigration removal centres awaiting deportation and others treated as criminals, despite being forced to commit offences by their exploiters. Hestia suggests little regard is shown to applying the statutory defence available to victims of exploitation who have been compelled or coerced into committing offences.

12.16 Police treating victims as immigration offenders

HMICFRS’s 2017 inspection report Stolen freedom: the policing response to modern slavery and human trafficking said: “A focus on the immigration status of both victims and offenders has been a recurring theme throughout this inspection”.

The 2017 inspection found a clear tendency by forces to deal with victims and offenders through immigration channels rather than examine in greater detail why they had come to the attention of law enforcement agencies.

It is clear from Hestia’s evidence, and from our own discussions with agencies supporting victims, that fear of immigration enforcement action is a barrier to foreign national victims reporting crimes and engaging with the police. Much of this fear is based on the police service informing the Home Office of victims’ immigration status.

A victim’s immigration status is required to be specified when they are referred for support under the NRM. Victims referred to the NRM are protected from any immigration enforcement until their case is decided at the ‘conclusive grounds’ point.

Many victims choose not to be referred and are notified to the Home Office anonymously under the duty to notify. There are several possible reasons for victims refusing to consent to an NRM referral, and immigration status is likely to be a factor for some.

Sharing information between the police and the Home Office can be important and in the public interest. It can help the police carry out an effective investigation, identify vulnerable people and, in some instances, protect them from harm. The Home Office may have relevant information, and be able to help with an investigation and/or help to protect and support victims.

The police are permitted, including by section 20 of the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999, to supply information about victims to the Home Office for immigration purposes. There are also common law powers for the police to exchange information with other public bodies when it is in the public interest and helps the work of the police and other bodies.

In April 2020, the NPCC revised its guidance on exchanging information about immigration offenders with the Home Office[footnote 10]. This sets out that “when a victim/witness is suspected by an officer of being an immigration offender, the police will share information about them with the Home Office”. The guidance describes the purposes of sharing information, and says that the type of information and when it should be shared should be decided in each case. It also says the police should tell victims that they intend to pass their information to the Home Office.

The guidance states that: “Officers will not routinely search police databases for the purpose of establishing the immigration status of a victim/witness”. The guidance expects that, regardless of any information sharing, the allegation reported by the victim should continue to be investigated and measures put in place to protect the victim or witness from harm.

Although forces are expected to follow NPCC guidance as a matter of good practice, they don’t have to do so.

When it gets information, the Home Office decides what action to take, including in relation to immigration law. This could be enforcement action or help in establishing the victim’s immigration status.

When someone comes to police attention because they are arrested on suspicion of committing an offence, there are routine checks to establish their identity, including through the Police National Computer (PNC). The PNC may show the person’s immigration status and, in this scenario, the Home Office would be notified if they are wanted for immigration offences. If, after arrest, it transpires that the person is a victim of modern slavery, an NRM referral can still be made and the consent of the person should be sought. If consent is not forthcoming, the referral should be anonymous.

A separate police super-complaint from Liberty and Southall Black Sisters (LSBS) examined how and why the police and Home Office share the personal data of victims and witnesses. A report of our joint investigation into this super-complaint was published in December 2020 and the resulting recommendations are included at Annex G. It concluded that significant harm is being caused to the public interest by the sharing of data on migrant victims and witnesses between the police and the Home Office. This is because victims of crime with insecure immigration status are fearful that, if they report to the police, their information will be shared with the Home Office and/or the reported crimes will not be investigated.

These findings are relevant to the Hestia super-complaint. Although the super-complaint from LSBS focused mainly on victims of domestic abuse with insecure immigration status, there is parallel with victims of modern slavery too. We have therefore used related findings from that investigation to inform this one.

The LSBS super-complaint investigation findings were that police officers don’t always prioritise safeguarding victims over immigration enforcement. In general, officers are positive about their joint work with the Home Office immigration enforcement team and consider safeguarding victims to be a priority. The LSBS investigation found no evidence that police forces intend to prioritise immigration enforcement over the investigation of crime and safeguarding. The LSBS investigation also found that police officers did not receive training on the appropriate response to victims and witnesses with insecure immigration status. Also, officers do not know whether referrals result in immigration enforcement action.

There is College of Policing training in relation to general vulnerability and domestic abuse, both of which emphasise the potential for victims of vulnerability related crime to be coerced and controlled because of their immigration status. This training, however, has not been taken up in all forces and any training needs to be supported by other implementation measures. Evaluation of one College training product showed high rates of effectiveness in impact on policing but that the impact reduced over months.

The LSBS investigation showed that forces are inconsistent in their approaches to exchanging information with the Home Office. None of the forces visited by the LSBS investigation team had any formal arrangements for sharing information about victims with the Home Office. Most officers spoken with didn’t know about the 2018 NPCC guidance (the 2020 guidance hadn’t been issued at the time of the force visits). Few forces have local policies to guide decision making, and instead rely on officers deciding in each case. The Home Office told the investigation team that the immigration enforcement team doesn’t arrest or detain everyone referred to them, and that worries about information sharing shouldn’t stop victims reporting a crime.

Despite this assurance, no information is collected to show how many contacts there are between police and the Home Office, the reasons for them, and what happens to victims as a result. This does little to counter victims’ fears that immigration action will be taken against them.

12.17 Summary Finding

Our findings suggest that victims may be deterred from reporting crimes and engaging in an investigation into modern slavery offences because they fear they will be treated as immigration offenders. The LSBS super-complaint investigation found no evidence that the police intend to treat victims as immigration offenders, and decisions about enforcement action rest with the Home Office. But evidence (including the LSBS investigation) suggests that this fear does contribute to victims’ unwillingness to engage with the police to support investigations into modern slavery crimes.

12.18 Police approach to victims who commit offences because they have been forced to do so by their exploiters

In our force fieldwork, we found that police officers and staff generally have a good understanding of how victims of trafficking and slavery can be forced to commit crimes. Dealing with county lines criminality – where gangs or organised crime groups force young or vulnerable people to deal drugs across the country – has led to much greater awareness of this among officers. The police response to county lines gangs is explored in detail in HMICFRS’s 2020 report, Both sides of the coin.

Officers we spoke with gave examples of cases involving someone they realised had been compelled to commit a crime (such as supplying drugs) through fear and coercion. They also talked about people who had shoplifted small amounts of food as they had no other way to survive. But understanding varied among different types of officers: specialist investigators had a good awareness, but frontline officers had a more mixed understanding. A lack of awareness may result in cases not being passed to specialist officers, and victims being dealt with solely as an offender rather than as a victim. This may mean that the section 45 defence is not considered in these cases.

Frontline officers told us that they usually arrest someone who has been compelled to commit a crime. This is because they have little option but to deal with the facts before them when a crime has been committed. They can’t be sure that a suspect is a victim of modern slavery. Once a suspect is in custody, officers told us they would seek advice on whether the person being investigated might be a controlled or coerced victim.

The section 45 defence does create significant problems for investigators, particularly at scenes of incidents when it is more difficult to carry out detailed investigations. Before allowing a suspect of a (possibly serious) crime to leave a scene, an investigator must have compelling evidence of coercion. This is often difficult to obtain at the scene.

This means that even when officers suspect someone is the victim of modern slavery, they may arrest him or her, without considering any alternatives such as taking the person to a safe place, putting support in place or arranging to interview them voluntarily.