A duty to protect: Police use of protective measures in cases involving violence against women and girls

Updated 7 June 2022

1. Senior panel foreword

Protecting the vulnerable and bringing offenders to justice are among the police’s principal legal and moral responsibilities. The recent case of the murder of Sarah Everard has spurred a public debate about violence, the safety of women and the police’s role in that respect.

Domestic abuse-related crime accounts for 1 in 6 (15 percent) of all crime recorded by the police in England and Wales, and over a third (35 percent) of all recorded violence against the person crimes.[footnote 1] Each year, more than 100,000 people [footnote 2] in the UK are assessed as being at a high and imminent risk of being murdered or seriously injured as a result of domestic abuse. Women are much more likely than men to be the victims of high risk or severe domestic abuse. In England and Wales, seven women a month are killed by a current or former partner. It is estimated that well over a million women suffer from domestic abuse each year.[footnote 3] These figures include violence, sexual assault and stalking by family members and current or former partners.

And yet the level of confidence in the police among female victims is worryingly low. Almost half (49 percent) of victims who have experienced sexual assault by rape or penetration (including attempts) since the age of 16 had been a victim more than once. Fewer than one in six reported the assault to the police.[footnote 4]

Behind these figures are the women and girls who are often suffering terrible abuse.

The Centre for Women’s Justice has made a super-complaint because it is concerned that the police are failing to use protective measures, namely bail, non-molestation orders, Domestic Violence Protection Notices and Domestic Violence Protection Orders and restraining orders, to protect women and girls. It is worried that highly vulnerable people are not being safeguarded.

HMICFRS, the College of Policing and the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) are responsible for assessing, investigating and reporting on police super-complaints. We have worked together on this investigation and have jointly agreed our conclusions.

1.1 What we found

Protecting female victims isn’t carried out by the police in isolation: they work with many other organisations, including criminal justice partners, such as the Crown Prosecution Service, the courts, Probation Service and the voluntary sector.

Our investigation in response to this super-complaint found examples of dedicated officers working well – both with victims and potential victims and with the Crown Prosecution Service – to put in place the best possible protection for vulnerable women and girls. Effective police work to protect women and girls can make material change beyond the individual case, including preventing further offences from being committed.

However, we also found instances where this didn’t happen. And when victims don’t feel well supported by the police, this can have significant and long-lasting consequences. The emotional effects can be devastating, and victims – and the people around them – who feel that the police didn’t take the case seriously may be less likely to report crime in future.

The reasons why police support for victims is sometimes not good enough are complex and varied. Sometimes officers are not aware of the powers available to them. Sometimes the processes are confusing. And sometimes officers don’t take the safety of vulnerable women and girls as seriously as they should.

1.2 Ensuring better protection

The Government’s new Tackling violence against women and girls strategy commits to reducing the prevalence of violence against women and girls and improving the support and response for victims and survivors. The previous strategy, Ending violence against women and girls: strategy 2016–2020, committed to making more tools available to the police to protect women and girls.

Providing powers to the police does not automatically mean that these powers will be used effectively. They must be fully understood before they are introduced and applied properly when they are introduced. There must also be careful data gathering and evaluation to make sure that these powers are having the intended results; the extent of many of the powers’ ability to protect is unknown. And, crucially, the powers must be embedded within broader law enforcement work.

We have made recommendations in relation to each of the protective measures in the super-complaint. These include recommendations that forces change and monitor their approaches in respect of these measures and to make sure that police officers are better equipped to understand the full suite of measures available. We have also made recommendations to the Home Office, the National Police Chiefs’ Council and the Ministry of Justice to do more to help make sure all measures are used as efficiently and effectively as possible. HMICFRS will also change its inspection activity to enhance its scrutiny of the use of these measures.

We believe these recommendations will help to support and drive policing to improve the response to domestic abuse aligned with the Government’s aim, set out in Tackling violence against women and girls strategy that no woman should live in fear of violence, and every girl should grow up knowing she is safe, so that she can have the best start in life.

2. Summary

2.1 What is a super-complaint?

A super-complaint is a complaint that “a feature, or combination of features, of policing in England and Wales by one or more than one police force is, or appears to be, significantly harming the interests of the public” (section 29A, Police Reform Act 2002).

The system is designed to examine problems of local, regional or national significance that may not be addressed by existing complaints systems. The process for making and considering super-complaints is set out in the Police Super-complaints (Designation and Procedure) Regulations 2018 (the regulations).

For more information on super-complaints, see Annex B.

2.2 What does this super-complaint say?

The Centre for Women’s Justice is concerned that the police are failing to use the protective measures available to them in cases involving violence against women and girls. The super-complaint addresses in detail four legal powers available to the police and explores the extent to which they are being used.

These powers are:

- pre-charge bail conditions;

- non-molestation orders;

- domestic violence protection notices and orders; and

- restraining orders.

The Centre for Women’s Justice believes that, when all these failures are taken cumulatively, there is a systemic failure to meet the state’s duty to safeguard a highly vulnerable section of the population.

In compiling its super-complaint, the Centre for Women’s Justice asked for information from a range of frontline organisations. The super-complaint and evidence from these organisations is available in Police super-complaints: police use of protective measures in cases of violence against women and girls.

2.3 Our approach and methodology

In our investigation into this super-complaint, we examined whether there is evidence that the concerns set out by the Centre for Women’s Justice are features of policing. We then considered whether there is evidence that they are, or appear to be, causing significant harm to the public interest.

To achieve this, we carried out a range of activities, including conducting fieldwork in 37 forces, discussions with experts and organisations with extensive knowledge of the use of protective measures, and a review of information held by the investigating bodies and provided by police forces and other public bodies.

2.4 Our findings

Our findings are grouped under the four areas of concern, and the collective use of these protective measures.

Failure to impose and extend bail conditions

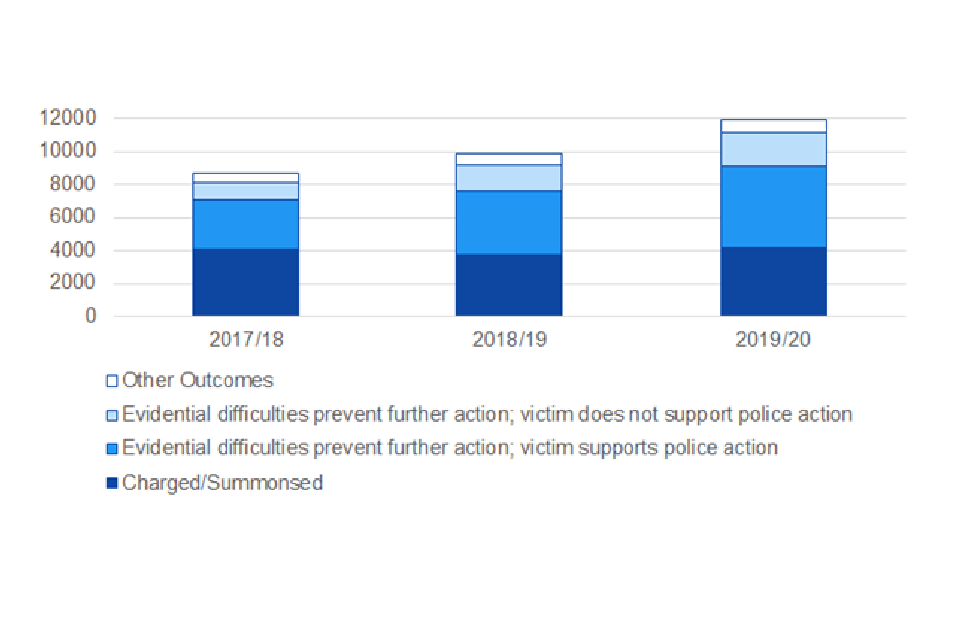

Following the introduction of changes to pre-charge bail legislation in April 2017, there has been a dramatic fall in the use of bail in rape, domestic abuse and harassment and stalking cases, and a corresponding increase in use of ‘released under investigation’ (RUI).

The super-complaint raises the concern that fewer bail conditions are being imposed on released suspects – even basic conditions such as not contacting the victim – and that this is making vulnerable women more at risk.

As we noted in HMICFRS’s report Pre-charge bail and released under investigation: striking a balance (2020), the data available is limited as a result of the police’s increased use of RUI instead of pre-charge bail. The report makes several recommendations about data collection, but it is too early for these to have had any significant effect. The Home Office’s response to the consultation on the 2017 changes, Police powers: Pre-charge bail, suggests it recognises there’s potential for harm. It says: “Since the reforms came into force, the use of pre-charge bail has fallen, mirrored by an increasing number of individuals ‘released under investigation’ or RUI. This change has raised concerns that bail is not always being used when appropriate, including to prevent individuals from committing an offence whilst on bail or interfering with victims and witnesses”.

There is evidence that imposing pre-charge bail on a suspected perpetrator, and the conditions attached to it, are linked with victims’ feelings of safety. Victims who don’t feel well supported by the police reported experiencing significant and long-lasting consequences. In several cases, victims who were dissatisfied with the police response felt they would be less likely to report a crime in the future.

There has been only limited research on the question of whether imposing pre-charge bail increases either the actual or perceived safety of victims. The qualitative research available suggested that bail can have tangible effects for the victim, including in the ways that people and organisations respond to their situation. In the research we conducted with victims, we found that some victims felt more reassured when the suspected perpetrator had bail conditions imposed on them. When it is lawful for police officers to do so, imposing bail with conditions can communicate to victims, suspected perpetrators and support organisations that the matter is being taken seriously. In some cases, a failure to impose bail may limit the victim’s ability to gain access to other services such as support and housing options and civil orders.

We know from HMICFRS inspection findings that the reduction of the use of pre-charge bail was as a direct result of the changes to the relevant legislation. We agree with the Centre for Women’s Justice that the absence of bail conditions (in circumstances in which pre-charge bail can be used lawfully) can cause significant harm to victims. For instance, we found evidence that a lack of bail conditions can cause victims to feel unsafe, and prevent them from receiving support from some third-party organisations. We also found a notable lack of research evidence on how well bail conditions protect victims by reducing reoffending (and so preventing further harm). We have made a recommendation to the Home Office to commission research on this.

The super-complaint suggests that there has been a large increase in suspects being invited to attend police interviews on a voluntary basis, rather than being arrested. Data is collected from forces on arrests and voluntary attendance as part of HMICFRS’s regular inspection programme. However, the data on voluntary attendance is limited and not all forces are currently able to provide it. And for those who do, it only goes back three years.

The 2017 changes to legislation introduced a more rigorous process for imposing bail on a suspect. A sample study from 30 forces showed that the use of bail for those arrested (for all crimes) had decreased from approximately 26 percent before the legislation was introduced to 3 percent immediately after its introduction. It is likely that a similar pattern may hold for domestic abuse and violence against women and girls, although limitations in the way that different forces record their data (particularly for RUI) and any differences in approach for these offences mean it is difficult to know for sure. The Government has announced changes to the legislation since the super-complaint was made, which will be implemented via the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill. We anticipate these changes will, to some extent, help address the concerns raised by the Centre for Women’s Justice. However, we think the Home Office and Ministry of Justice should revisit whether to create a bespoke offence of breaching pre-charge bail, which has been described as a ‘toothless tiger’.

Use of non-molestation orders

Non-molestation orders (NMOs) are designed to protect victims and are issued by the courts. They prohibit the abuser from certain types of activity, such as threatening or being violent towards one or more individuals in their family, including children, or going within a certain distance of an individual’s home.

The super-complaint raises the concern that the police often fail to arrest people who breach their NMO. It also raises concerns that some officers suggest that victims obtain NMOs as an alternative to other police action such as making an arrest.

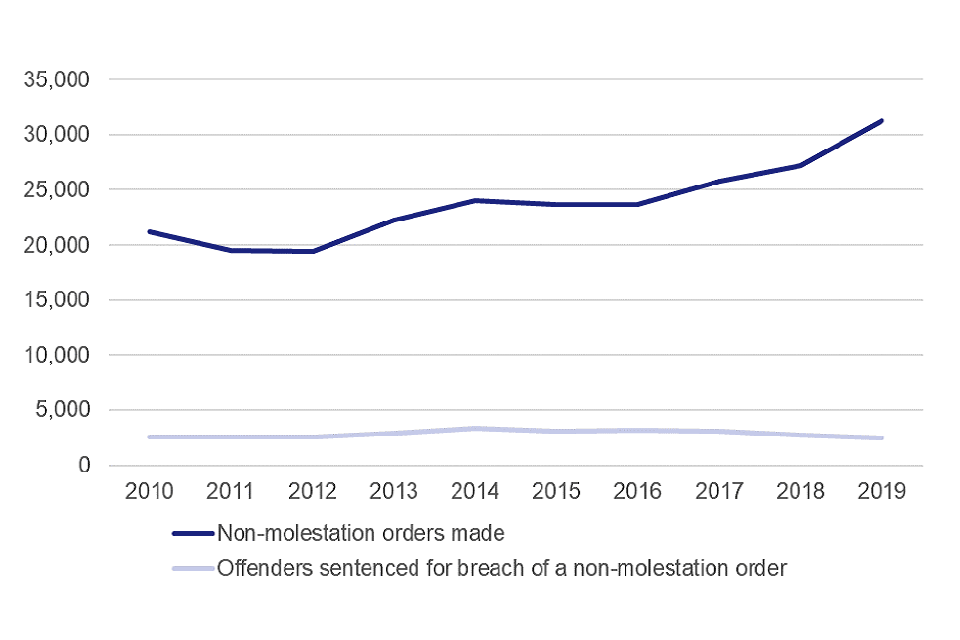

We agree with the Centre for Women’s Justice that failure to arrest for breach of an NMO has the potential to cause significant harm. Ministry of Justice data shows that the number of NMOs granted has been increasing since 2012 and Home Office data shows that while reports of breaches of non-molestation orders recorded by the police have increased, the number of NMO breach cases which are not proceeding has increased significantly. Additionally, Ministry of Justice data shows that the number of offenders sentenced for breaching NMOs has been going down since 2014.

Our fieldwork for this report found that nearly every force had a good overall understanding of NMOs and when it is appropriate to arrest someone for breaching an NMO. However, officers sometimes have trouble gaining access to NMOs as a result of inconsistent or slow recording in records systems. And when they can gain access to them, many officers found that NMOs issued by the civil courts were not clear enough in their wording, making a decision about arrest difficult.

The super-complaint also raises the question of whether the police are advising victims to apply for NMOs as an alternative to police action. The officers we spoke to didn’t believe this to be the case on the basis of their experience, and told us that they provided information about options for victims but did not routinely advise victims to get NMOs.

Failure to use Domestic Violence Protection Notices and Domestic Violence Protection Orders

Domestic Violence Protection Notices (DVPNs) and Domestic Violence Protection Orders (DVPOs) are designed to give short-term protection to a victim in the immediate aftermath of domestic abuse by preventing the suspected perpetrator from contacting the victim or returning to a residence for up to 28 days. They can be issued by the police without the co operation of the victim. While DVPNs and DVPOs are currently in use, they will be repealed and replaced by new Domestic Abuse Protection Notices (DAPNs) and Domestic Abuse Protection Orders (DAPOs) when the Domestic Abuse Act 2021 enters into force.

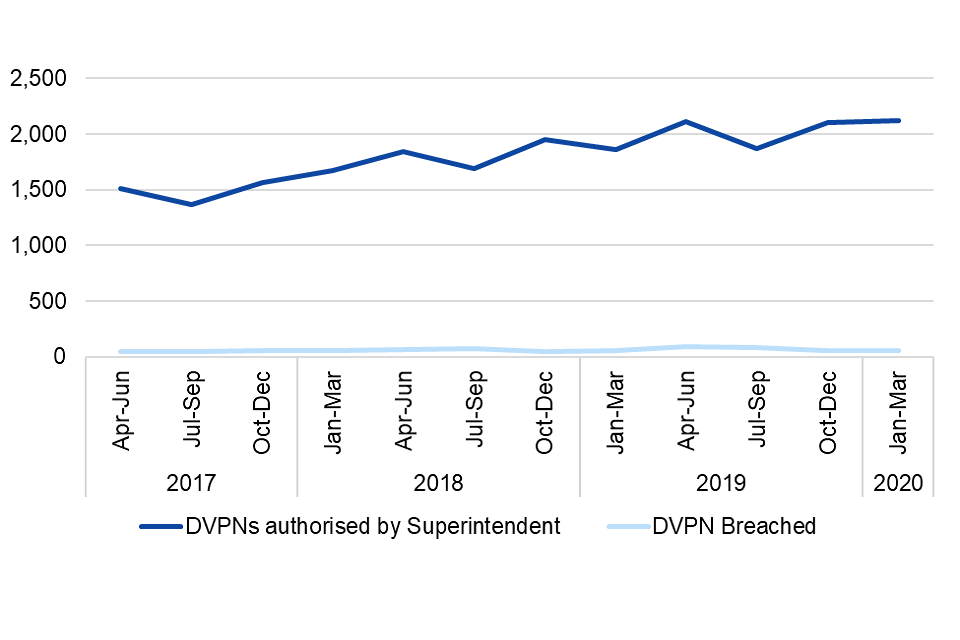

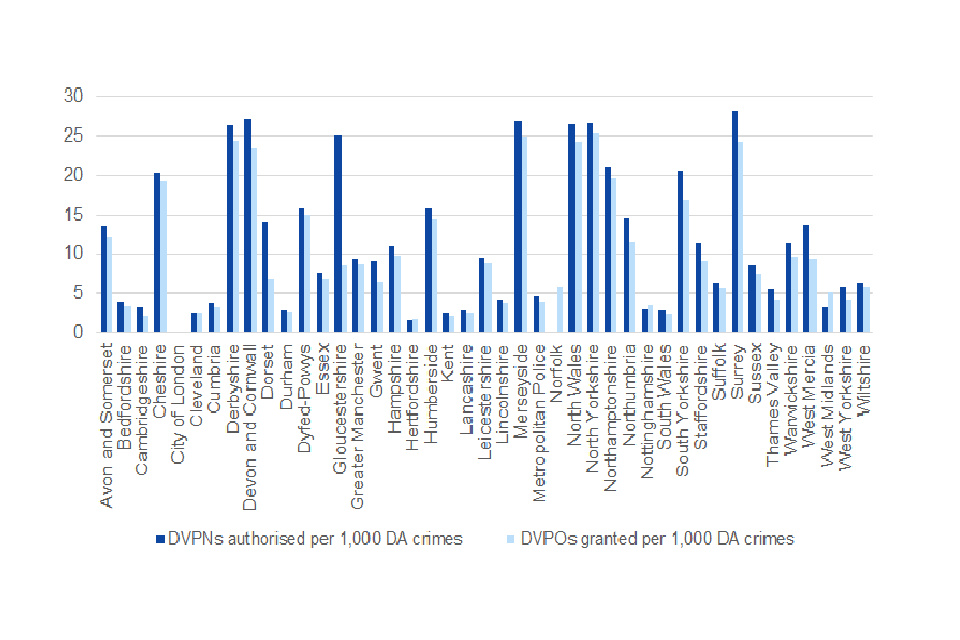

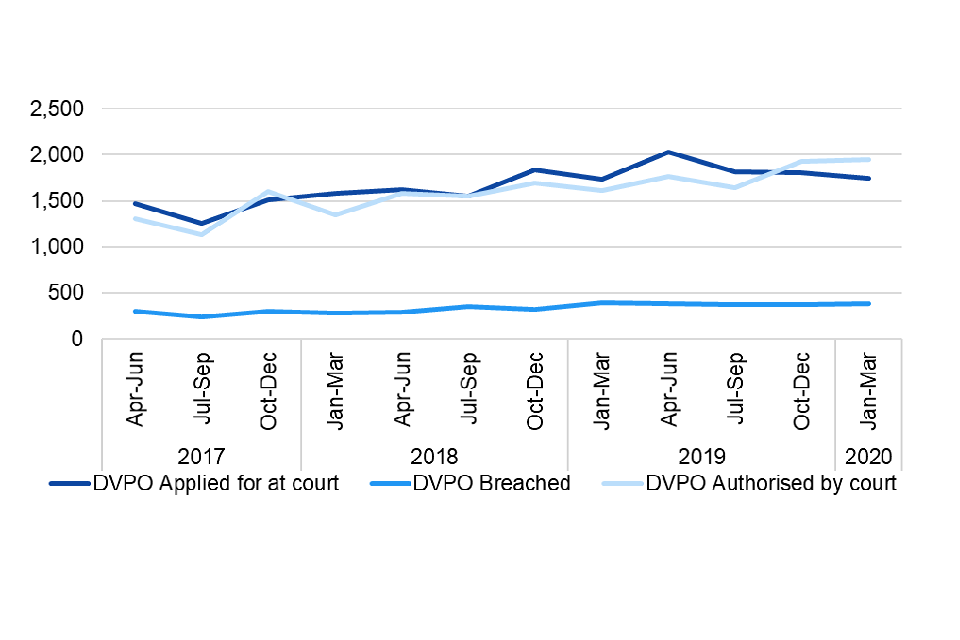

Once again, the limited data currently available makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions about the use of DVPNs and DVPOs and whether they are being underused. Although the total number of DVPNs issued between 2018 and 2020 increased by more than a third, DVPNs and DVPOs are still being issued in only a small proportion of domestic abuse cases. This strongly suggests that they are being underused.

The fact that different forces are using these at substantially different rates also suggests at the very least that they aren’t being used consistently and may mean that forces issuing fewer notices and orders aren’t using them in cases when they should be. This has the potential to cause harm.

We asked officers from 37 forces why they think the number of DVPNs and DVPOs issued is so low. More than half reported finding DVPNs time-consuming, complicated, bureaucratic and difficult. These tended to be staff from forces where DVPN use is falling. In forces where their use is high, we found that DVPNs tend to be widely understood, embedded in processes and supported by a legal team.

There is little published research on how effective DVPNs and DVPOs are at increasing victims’ safety. The evidence available suggests that they result in a modest reduction in victimisation. This effect is strongest in chronic cases (three or more incidents) rather than first-time incidents.

Failure to apply for restraining orders

Restraining orders are issued by a judge in criminal proceedings to protect the victim, for example in cases of domestic abuse or stalking. They put restrictions on the offender, for example to stop them from contacting the victim or to prevent them from going to certain areas.

The super-complaint suggests that restraining orders could be used more effectively, and raises many concerns, including that applications are being overlooked. Data from the Ministry of Justice shows a reduction in the number of restraining orders granted from 2016 to 2018, which mirrors a fall in prosecutions for domestic abuse cases. Additionally, HMIC’s 2017 report Living in fear – the police and CPS response to harassment and stalking noted that the police and Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) sometimes fail to request restraining orders and recommended that paperwork be changed and clear guidance provided.

When conducting our fieldwork, we did not find clear evidence that the police are consistently underutilising restraining orders. For example, 32 out of the 37 forces we assessed told us that they routinely considered and asked the CPS to apply for restraining orders in domestic abuse cases.

The super-complaint argues that, when a restraining order has not been made by the time the sentencing hearing is over, the magistrates’ court should be able to grant one later under the slip rule, which allows mistakes to be corrected. However, the CPS does not view the failure to request a restraining order as the kind of error that the slip rule is able to correct.

Collective use of protective measures

Making sure women and girls are properly protected isn’t a matter for the police alone. The police, Government, criminal justice system and those who provide support to victims all need to work together.

We will not know if the changes introduced by the Domestic Abuse Act 2021 and Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill (when enacted and brought into force) have improved victims’ experiences unless there are systems in place to measure this and assemble data consistently across England and Wales. Without this, it will not be possible to monitor the different protective measures. Recording this data will ultimately allow forces to determine which protective measures are most effective in different scenarios.

Changes need to be made to the way the police and civil and criminal courts co-ordinate their work so important information, and consequently victims’ safety, doesn’t fall through the gaps that currently exist in the system.

Similarly, while our investigation has made recommendations for improving the policing of protective measures, making sure there is a multi-agency, community response, tailored by forces and local authorities is, in our view, the best way of giving better protection for women and girls.

Recommendations and actions

Recommendations

- Chief constables, in conjunction with the NPCC lead for bail, should implement processes for managing RUI in line with the letter from the NPCC Lead for Bail Management Portfolio dated 29 January 2019 (Annex F). This is to ensure, as far as is possible, that investigations are conducted efficiently and effectively, thereby supporting both victims of crime and unconvicted suspects.

- Chief constables should ensure data is gathered on the use of voluntary attendance to enable the identification of patterns of its use, particularly in relation to the types of cases, so that voluntary attendance is only used in those cases where it would be an appropriate case management tactic.

- Chief constables should introduce processes to ensure that in all pre-charge bail cases where bail lapses, the investigator in charge of the case carries out an assessment of the need for pre bail-charge to continue. In those cases where the suspect has not been charged, the decision to extend or terminate bail should be recorded with a rationale.

- The Home Office should commission research on whether bail reduces re-offending and protects victims, and publish the findings of any such research.

- The Home Office and Ministry of Justice should intensify and accelerate their consideration of the creation of a bespoke offence of breaching pre-charge bail.

- The Ministry of Justice and the Home Office should review the mechanism for informing the police of NMOs and propose remedies for improvement.

- Chief constables should review and if necessary refresh their policy on how the force processes notifications of NMOs, so officers can easily identify if an NMO exists.

- The Ministry of Justice should review a sample of NMOs to consider whether the wording of these are ambiguous and could cause problems for enforcement and propose a remedy to prevent ambiguity in NMO wording, if it is identified.

- The Home Office should publish data on the number of reported breaches of NMOs. This should form part of the annual data collection on the applications for and granting of NMOs.

- The NPCC lead for domestic abuse should consider Home Office data on the number of reported breaches of NMOs, and provide a report to HMICFRS within six months on national actions and guidance required as a result.

-

Chief constables should, until DAPOs replace DVPNs and DVPOs in their force.

a. review, and if necessary refresh their policy on DVPNs and DVPOs, and in line with the overarching recommendation:

i. ensure that there is clear governance and communication to prioritise the effective use of DVPNs and DVPOs, when these are the most appropriate tools to use;

ii. monitor their use to ensure they are being used effectively; and

b. ensure experience and lessons learned on using DVPN/DVPOs informs the use of DAPOs. -

The NPCC should formulate a robust process, working with the CPS, to clearly define roles to ensure restraining orders are applied for in all suitable cases and that the victim’s consent is obtained. This process should ensure prosecutors are made aware of what conditions are appropriate to protect the victim and that victims are consulted on the proposed conditions.

-

Chief constables should assure themselves that:

a. their officers are fully supported in carrying out their duties to protect all vulnerable domestic abuse victims by:

i. ensuring their officers understand the suite of protective measures available (including new measures such as DAPOs);

ii. ensuring officers are aware of referral pathways to third-party support organisations which are available to protect vulnerable domestic abuse victims; and

iii. ensuring their officers have guidance and support on how to choose the most appropriate response for the situation; andb. governance is in place to monitor the use of all protection orders and to evaluate their effectiveness, including by seeking the views of victims.

- Chief constables should consider what legal support they need to use protective measures (if they don’t already have this) and secure this support. The NPCC should consider whether regional or national legal (or other) expertise could be made available, so forces can easily access specialist support and can maximise efficiency and consistency.

-

Monitoring of recommendations

a. Home Office and Ministry of Justice to each provide a report to Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Constabulary on progress in implementing HMICFRS’s recommendations within six months of the date of publication of this report.

b. NPCC to collate chief constables’ progress in reviewing and, where applicable, implementing their recommendations and report these to Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Constabulary within six months of the date of publication of this report.

Actions

- In light of changes to pre-charge bail, we propose that HMICFRS should consider future inspection activity to review the impact of the changes.

- The College of Policing will update its guidance to reflect changes needed on the implementation of the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill and to clarify that officers may consider that if a suspect were to be released from police detention on bail with lawfully imposed conditions, the need for those conditions may well fulfil the ‘necessity test’ for arrest.

- HMICFRS to continue to assess use of DVPN/DVPOs and any new domestic abuse orders through its wider inspection activity.

- HMICFRS should consider future inspection activity in respect of restraining orders, including supervision and monitoring use of these by police forces. After a suitable period when more data is available from the inspection activity, HMICFRS and Her Majesty’s Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate (HMCPSI) should consider undertaking a review to assess how effective the police and CPS are at applying for restraining orders, and if there is any point of failure within the process that needs to be addressed.

3. Background and overarching legal framework

3.1 Crimes of violence against women and girls

Crimes of violence against women and girls involve a broad range of offences, including:

- assault;

- rape;

- sexual offences;

- stalking;

- harassment;

- so-called ‘honour-based’ violence, including forced marriage;

- female genital mutilation;

- child abuse;

- human trafficking focusing on sexual exploitation; and

- prostitution.

The Government’s aim is that no woman should live in fear of violence, and every girl should grow up knowing she is safe, so that she can have the best start in life. This was set out in the Government’s Ending violence against women and girls: strategy 2016–2020. Since then, in July 2021, the Home Office has published its new Tackling violence against women and girls strategy. This commits to reducing the prevalence of violence against women and girls and to improving the support and response for victims and survivors.

In April 2021, following the national debate which took place after the murder of Sarah Everard, the Home Secretary commissioned HMICFRS to undertake a bespoke thematic inspection into police handling of female victims of crime and engagement with women and girls. While some elements of the inspection (for example the enforcement of non molestation orders (NMOs), and use of Domestic Violence Protection Notices (DVPNs) and Domestic Violence Protection Orders (DVPOs)) are relevant to our super complaint investigation, the scope of the inspection is much wider. It focuses on the quality and effectiveness of interactions between the police and women (whether as victims, offenders or witnesses), with a focus on the lived experiences of women and girls. A report summarising the findings of this inspection is due to be published later this year.

3.2 The prevalence of domestic abuse

Domestic abuse remains a hidden crime, with much of it going unreported to police or specialist services. The Crime Survey for England and Wales showed that an estimated 2.0 million adults (aged 16 to 59 years) experienced domestic abuse in the year to March 2020. This number has been falling over time. An estimated 2.7 million adults (aged 16 to 59 years) experienced domestic abuse in the year to March 2005.

However, the police in England and Wales (excluding Greater Manchester Police) recorded only 759,000 domestic abuse-related crimes in England and Wales, an increase of 9 percent from the previous year. This continues a trend that may reflect improved recording by the police alongside increased reporting by victims. HMICFRS data shows that there has been an increase of 27 percent in the volume of domestic abuse crimes recorded between 2017/18 and 2019/20 in England and Wales (excluding Greater Manchester Police). Arrests per 100 domestic abuse crimes have decreased by 7 percentage points over the same period. Use of voluntary attendance increased by 0.2 percentage points in that time.

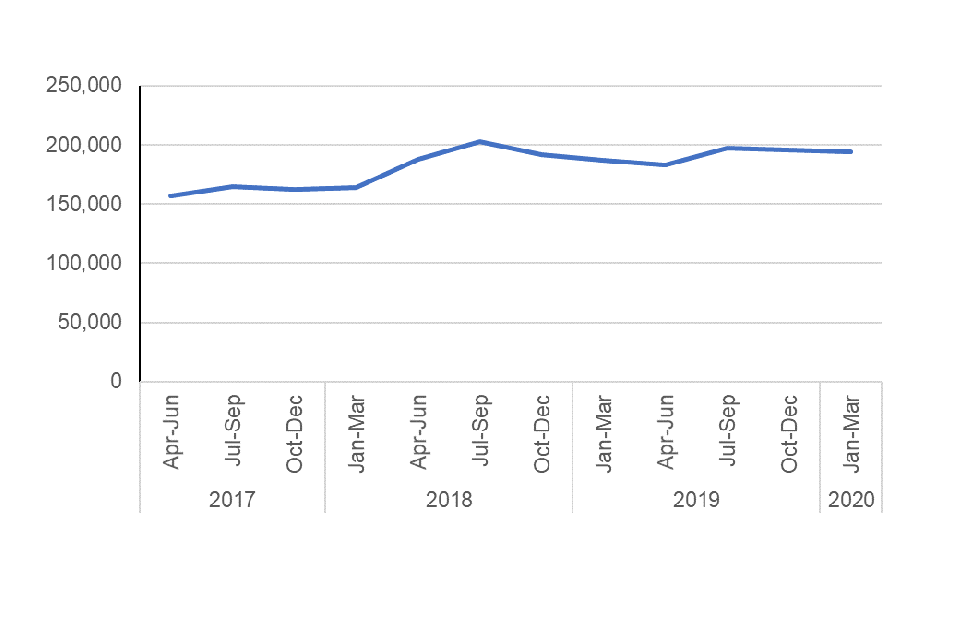

Figure 1: Domestic abuse crimes in England and Wales, 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2020

There has been an increase of 27 percent in the volume of domestic abuse crimes recorded by the police between 2017/18 and 2019/20, in England and Wales (excluding Greater Manchester Police).

Source: HMICFRS data collection

Note: Greater Manchester Police hasn’t been included in 2019/20 figures as a result of problems with the implementation of new ICT systems

Since the publication of the HMIC report Everyone’s business in 2014, there has been a continued increase in domestic abuse crimes recorded by police forces in England and Wales. Some of this rise can be attributed to the continued focus of all police forces on the domestic abuse agenda, including engagement in national campaigns such as No Excuse,[footnote 5] alongside improvements in identifying incidents of domestic abuse and accuracy of crime-recording.

Between April 2016 and February 2020, as part of the rolling programme of Crime Data Integrity inspections, HMICFRS reviewed representative samples of reports of crime to police forces in England and Wales. Patterns in crime-recording changed in this period with the national trend showing a substantial improvement in crime-recording standards, in particular for violent and sexual offences.

These improvements in recording violent and sexual offences in general, along with improvement in crime-recording as part of vulnerable victim cases, means more domestic abuse-related offences are accurately identified and recorded by the police. This also likely influenced the increased upwards trend in the volume of domestic abuse-related offences recorded by police forces in England and Wales.

Even though crime-recording standards have improved, there is scope for further improvement. In a minority of forces, substantial improvements are still required to make sure victims’ reports are recorded and victims receive the service and support they deserve.

3.3 The Policing and Crime Act 2017 and changes to the use of pre-charge bail

The Policing and Crime Act 2017 introduced several changes to policing. One of the main elements of the legislation made changes to pre-charge bail. The changes were intended to remedy the problem of suspects being on pre-charge bail for long periods of time, which caused concerns and uncertainty for both victims and suspects. In particular, the Act introduced a presumption against the use of pre-charge bail, changed the timescales for pre-charge bail periods and required pre-charge bail to be authorised by a more senior officer than was previously the case. These changes made the use of pre-charge bail less likely and made it more likely that suspects would be released under investigation (RUI).

3.4 The Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill

In its January 2021 response to a consultation on the 2017 changes Police powers: Pre charge bail, the Home Office said:

Since the reforms came into force, the use of pre-charge bail has fallen, mirrored by an increasing number of individuals ‘released under investigation’ or RUI. This change has raised concerns that bail is not always being used when appropriate, including to prevent individuals from committing an offence whilst on bail or interfering with victims and witnesses. Other concerns focus on the potential for longer investigations in cases where bail is not used and the adverse impact on the courts. The Government committed to reviewing this process to consider whether further change is needed to ensure that bail is being used where appropriate and to support the police in the timely progression of investigations. As a result of the consultation process, a number of proposals will be taken forward to ensure the bail regime is proportionate and effective. Where legislation is required to give effect to these proposals, as set out in this document, this will be taken forward in the current parliamentary sitting.

This Government response, which was announced after the super-complaint was submitted, established new measures to create a more proportionate system where people are not held on pre-charge bail for unreasonable lengths of time. It also gave the police the power to impose conditions on more suspects in alleged high-harm cases, including cases of domestic abuse and sexual violence. These new measures will be brought in via the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill.

3.5 The Domestic Abuse Act 2021

The Domestic Abuse Bill was presented to Parliament in July 2019 following a period of consultation and received Royal Assent in April 2021. The Domestic Abuse Act 2021 contains provisions on many aspects of the management of domestic abuse, including defining domestic abuse, the introduction of new Domestic Abuse Protection Notices (DAPNs) and Domestic Abuse Protection Orders (DAPOs), and changes to the way domestic abuse is dealt with in the criminal justice system.

The Act will repeal the current DVPNs and DVPOs that form part of the Centre for Women’s Justice’s super-complaint.

DAPNs, like the current DVPNs, are intended to give victims immediate protection following an incident. A DAPN would be issued by the police and could, for example, require a suspected perpetrator to leave the victim’s home for up to 48 hours.

DAPOs are designed to provide longer-term protection for victims. As with the current DVPO, the police will make an application for a DAPO to a magistrates’ court. However, the Government will introduce alternative application routes so that victims and specified third parties can apply for a DAPO directly to the family court. It will also give criminal, family and civil courts the power to make a DAPO during existing court proceedings, which don’t have to be domestic abuse-related.

DAPOs may impose both prohibitions and positive requirements on suspected perpetrators. These could include prohibiting the suspected perpetrator from coming within a specified distance of the victim’s home and/or any other specified premises, such as the victim’s workplace, alongside requiring the suspected perpetrator to attend a behaviour change programme, an alcohol or substance misuse programme or a mental health assessment.

The courts will be able to vary the requirements imposed by a DAPO so that they can respond to changes over time in the suspected perpetrator’s behaviour and the level of risk they pose. The legislation will also give courts the express power to use electronic monitoring (‘tagging’) to monitor a suspected perpetrator’s compliance with certain requirements imposed by a DAPO.

All DAPOs will include notification requirements, which will require suspected perpetrators to notify the police of their name and address and of any changes to this information. The Act also includes the power for additional notification requirements to be specified in regulations, which courts may impose on a case-by-case basis as appropriate.

Breach of a DAPO will be a criminal offence, carrying a maximum penalty of up to five years’ imprisonment, or a fine, or both. Breaches will be dealt with as a civil contempt of court.

The Government plans to pilot DAPNs and DAPOs in a small number of areas across the UK to assess the effectiveness of the new model before it is brought in nationally.

It is expected that most of the provisions in the Act will come into force during 2021/22.

3.6 Definition of domestic abuse

From March 2013 until the implementation of the Domestic Abuse Act 2021, the definition of domestic abuse for the purposes of crime-recording was “Any incidents or pattern of incidents of controlling, coercive or threatening behaviour, violence or abuse between those aged 16 or over who are or have been intimate partners or family members regardless of gender or sexuality”.

This meant that any crime involving a family member aged 16 or over who behaved in a threatening or violent way against another family member aged 16 or over (for example their parent or sibling) should have been recorded as domestic abuse. For example, this could have included a threat made through Facebook from one sibling to another, even when they live miles apart.

The Domestic Abuse Act 2021 changed the definition of domestic abuse. Section 1 defines it as:

(2) Behaviour of a person (“A”) towards another person (“B”) is “domestic abuse” if—

(a) A and B are each aged 16 or over and are personally connected to each other, and

(b) the behaviour is abusive.

(3) Behaviour is “abusive” if it consists of any of the following—

(a) physical or sexual abuse;

(b) violent or threatening behaviour;

(c) controlling or coercive behaviour;

(d) economic abuse (see subsection (4));

(e) psychological, emotional or other abuse;

and it does not matter whether the behaviour consists of a single incident or a course of conduct.

(4) “Economic abuse” means any behaviour that has a substantial adverse effect on B’s ability to—

(a) acquire, use or maintain money or other property, or

(b) obtain goods or services.

(5) For the purposes of this Act A’s behaviour may be behaviour “towards” B despite the fact that it consists of conduct directed at another person (for example, B’s child).

3.7 Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 Code of Practice G

This Code of Practice states a lawful arrest requires two elements, namely (1) a person’s involvement or suspected involvement or attempted involvement in the commission of a criminal offence and (2) reasonable grounds for believing that the person’s arrest is necessary.

The Centre for Women’s Justice makes the point in their super-complaint that the law allows for arrest on the grounds of a need for bail conditions to protect the complainant. The super-complaint refers to a High Court judgment in January 2017[footnote 6] in which the judge expressed the view that the need for bail conditions can make an arrest necessary on either one of two grounds under section 24 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984, namely to allow the prompt and effective investigation of the offence or to protect a vulnerable person from the accused.

The College of Policing will amend its guidance to reflect when an arrest may be lawful, to remove any confusion among officers.

3.8 HMICFRS inspections

HMICFRS has undertaken a number of inspections which are relevant to this super-complaint.

Between October 2019 and February 2020, HMICFRS and Her Majesty’s Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate (HMCPSI) jointly inspected police and CPS responses to the pre-charge bail changes and the use of released under investigation (RUI).

The findings of this inspection are set out in the report Pre-charge bail and released under investigation: striking a balance. The recommendations of this report are included at Annex E for information.

Other HMIC/HMICFRS reports relevant to this super-complaint include:

- Everyone’s business: Improving the police response to domestic abuse (March 2014).

- Increasingly everyone’s business: A progress report on the police response to domestic abuse (December 2015).

- A progress report on the police response to domestic abuse (November 2017).

- The police response to domestic abuse: An update report (February 2019).

- Living in fear – the police and CPS response to harassment and stalking (A joint inspection by HMIC and HMCPSI; July 2017).

- Stalking and harassment – An inspection of Sussex Police commissioned by the police and crime commissioner, and an update on national recommendations in HMICFRS’s 2017 report (April 2019).

- Evidence led domestic abuse prosecutions (a joint inspection by HMIC and HMCPSI; January 2020).

Most recently, and since the investigation into this super-complaint has concluded, HMICFRS has published Review of policing domestic abuse during the pandemic – 2021, its Interim report: Inspection into how effectively the police engage with women and girls and A joint thematic inspection of the police and Crown Prosecution Service’s response to rape (A joint inspection by HMICFRS and HMCPSI; July 2021).

3.9 College of Policing guidance

The College of Policing has four published Authorised Professional Practice (APP) documents relevant to this super-complaint. These are on domestic abuse, on investigation, on arrest and other positive approaches and on post-arrest management of suspect and case file.

4. Our super-complaint investigation

4.1 Scope

Our investigation considered whether there is evidence that the concerns set out by the Centre of Women’s Justice are features of policing. We then considered whether there is evidence that they are, or appear to be, causing significant harm to the public interest.

4.2 Methodology – how we investigated the super-complaint

We established the following lines of enquiry to structure an investigation of current police practice, examine its rationale and assess evidence of harm. The investigation examined:

- the extent to which the legal powers the super-complaint focuses on are used and understood by both frontline officers and supervisors;

- training available to officers about the legal powers, as well as other connected themes such as vulnerability, and to what extent training is being accessed;

- an understanding of any effect the 2017 changes to pre-charge bail have had on officers’ decision-making;

- what other factors affect officers’ decision-making; and

- the risks of harm to the public arising from forces not adequately using or enforcing the four legal powers mentioned in the super-complaint.

To fulfil these lines of enquiry, the investigation team:

- reviewed evidence submitted by the Centre for Women’s Justice as part of its super-complaint;

- submitted a request to all 43 territorial forces in England and Wales for information on current relevant practices;

- considered findings from previous inspection reports;

- reviewed existing data and sought new data from outside parties (mainly focusing on data related to domestic abuse cases, as the most common crime reported against women);

- consulted interested parties, including members of HMICFRS’s Domestic Abuse Expert Reference Group;[footnote 7]

- examined submissions and documents provided by public bodies and other agencies in response to our enquiries;

- conducted an exercise to identify the points when decisions are made about protective measures;

- conducted a review of relevant national policy, guidance and research;

- reviewed Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) cases (and those of the Independent Police Complaints Commission, or IPCC) to identify relevant investigations and whether any learning was relevant to inform this super-complaint investigation; and

- conducted fieldwork in 37 forces across England and Wales.

Separately, HMICFRS commissioned research consultancy BritainThinks to conduct qualitative research (first-hand observations and interviews) to explore victim and suspect experiences of changes made as a result of the Policing and Crime Act 2017.

4.3 About our fieldwork

Police officers and staff working on the front line take initial decisions to use (or not use) the powers discussed in this super-complaint. We spoke to custody sergeants, public protection officers, domestic abuse specialists and response officers either individually or together in a focus group. The discussion leaders were trained force liaison leads or inspection officers experienced in obtaining evidence for HMICFRS force inspections.

Data from IOPC and IPCC cases

The IOPC investigates the most serious and sensitive incidents and allegations involving the police. These independent investigations are conducted by IOPC investigators. Before January 2018, the IOPC’s predecessor, the IPCC, carried out independent investigations. To help with the investigation of this super-complaint, a search of relevant IOPC and IPCC independent investigations was carried out, focusing on investigations completed between April 2014 and October 2019.[footnote 8]

Due to the nature of the IOPC’s/IPCC’s work and the criteria for referral, the IOPC doesn’t see every case, and so information from independent investigations is not necessarily representative of what is happening or has happened across all forces. In some cases, no issues are identified with the way in which police have dealt with matters. However, this review focused on whether there was any evidence in IOPC/IPCC independent investigations of harm being caused by the way in which police were using, or failing to use, protective measures in cases involving violence against women and girls.

See Annex D for more information about the data sources used in this investigation.

We identified a variety of people and organisations with knowledge of, and expertise in, the matters raised in the super-complaint and approached them for their views. As the investigation progressed, documents were given to us by some of those approached and each was reviewed. These included policy documents (given by 15 forces), academic research, and published reports and documents.

The following sections set out our assessment of each of the four powers referred to in the super-complaint in turn (bail conditions, non-molestation orders (NMOs), Domestic Violence Protection Notices (DVPNs), Domestic Violence Protection Orders (DVPOs) and restraining orders).

5. Our findings: Failure to impose pre-charge bail conditions

The Centre for Women’s Justice expressed concerns that the failure to impose pre charge bail in three situations is leaving victims potentially unprotected. These are:

- where suspects are interviewed following voluntary attendance and pre-charge bail can’t be used;

- where suspects are interviewed under arrest, released under investigation (RUI) without bail, or released on pre-charge bail without bail conditions; and

- where pre-charge bail isn’t extended beyond 28 days.

“A dramatic fall in the use of bail”

The Centre for Women’s Justice is concerned that, following the introduction of the changes to pre-charge bail legislation in April 2017, there has been a dramatic fall in the use of pre-charge bail in rape, domestic abuse, and harassment and stalking cases.

The Centre for Women’s Justice says that many suspects are released without any pre charge bail conditions. It says that previously it was standard practice to release suspects on pre-charge bail with conditions. Frontline organisations contacted by the Centre for Women’s Justice (for more detail, see Police super-complaints: police use of protective measures in cases of violence against women and girls) reported a widespread lack of pre-charge bail conditions (where they thought conditions should have been applied) in cases involving domestic abuse, harassment and stalking, and rape.

The Centre for Women’s Justice considers this as surprising, given “the first three of these behaviours invariably involve repeat victimisation and in the majority of rape cases the parties know each other. Many, if not most, such cases involve vulnerable women. Frontline organisations report that women are living in fear, exposed to persistent and dangerous men”.

The Centre for Women’s Justice also explains that “Whilst … [victims] may be in fear even if bail conditions were used, and in some cases conditions may have been breached, bail conditions at least represent an attempt by the authorities to provide protection during the critical period following a report to police.”

The Centre for Women’s Justice also says that the failure to impose pre-charge bail conditions has had other wider consequences, such as making it more difficult for victims to access other services.

5.1 Background

Granting a suspected perpetrator pre-charge bail is an alternative to them being in custody. Following an arrest, a decision to bail a suspected perpetrator can be made by:

- the police, when there isn’t sufficient evidence to charge the person – this is also known as pre-charge bail and sometimes called police bail;

- the police, when a suspected perpetrator has been charged with an offence – this is also known as post-charge bail; and

- by the courts when a person has been charged – this is also known as court bail.

Our investigation focused on pre-charge bail. The police powers relating to the use of pre charge bail are set out in the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE).

Pre-charge bail allows for police officers and staff to continue investigations without suspects being detained. It can be imposed with or without conditions. Bail conditions can only be applied to suspects who have been arrested and where pre-charge bail is applied. As a result, they can’t be applied to suspects who are RUI or interviewed after voluntary attendance.

Bail conditions can be imposed under section 3OA(3B) of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 if the custody officer considers them necessary:

- to prevent the person from failing to surrender;

- to prevent the person from committing an offence while on bail;

- to prevent the person from interfering with witnesses or otherwise obstructing the course of justice; or

- for the person’s own protection or welfare.

Examples of pre-charge bail conditions could include:

- not to contact the victim directly or indirectly – where there are child contact problems, this may be modified to allow contact through a third party (solicitor/social services/mutually acceptable family member) to arrange child contact;

- not to attend the home address of the victim/not to enter the victim’s street or a specific area marked out on a map – specified distances may also be used but can be difficult to enforce;

- not to go to the victim’s place of work;

- not to go to a named school or other place the victim or victim’s children attend regularly, such as shopping areas, leisure or social facilities, child minders, family and friends;

- to live and sleep at a specified address – this should never be that of the victim, whether or not the suspected perpetrator owns the house or is named on the tenancy agreement;

- to report to a named police station on specific days of the week at specified times; and

- to obey a curfew within specified times (the curfew address must not be that of the victim).

PACE establishes that pre-charge bail conditions are necessary to manage risks posed by the suspect to the victim or wider community. There is a presumption in law that unless imposing pre-charge bail satisfies the necessity and proportionality criteria and is subject to authorisation by an officer of the rank specified, that a suspect will be RUI.

Whether bail is considered necessary and proportionate in the circumstances is judged in accordance with Article 8(2) of the European Convention on Human Rights (the right to respect for private and family life) and case law arising from it. The terms ‘necessary’ and ‘proportionate’ are refined and defined below.

Necessary

Bail authorisation is permitted under Article 8(2) of the European Convention on Human Rights (the right to respect for private and family life), if it is necessary in a democratic society for one of the following reasons:

- in the interests of national security;

- in the interests of public safety;

- in the interests of the economic wellbeing of the United Kingdom;

- for the prevention of disorder or crime;

- for the protection of health or morals; or

- for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.

Proportionate

Authorisation is proportionate if:

- what is being done is not arbitrary or unfair;

- the restriction is strictly limited to what is required to achieve a legitimate public policy; or

- the severity of the effect of the restriction does not outweigh the benefit to the community that is being sought by the restriction.

Any restriction must be proportionate to the legitimate aim being pursued.

5.2 National Police Chiefs’ Council guidance

In January 2019, the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) published updated Operational Guidance for Pre-Charge Bail and Released Under Investigation.

5.3 Situations of concern raised in the super-complaint

The three situations of concern to the Centre for Women’s Justice are examined in detail below.

Situation 1: When suspects are interviewed following voluntary attendance and pre charge bail can’t be used

The super-complaint suggests there has been a large increase in suspects being invited to attend police interviews on a voluntary basis, rather than under arrest.

The discretion to arrest or not arrest a suspect rests with the investigator, who is usually a police officer. The Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 Code of Practice G states:

The use of the power [of arrest] must be fully justified and officers exercising the power should consider if the necessary objectives can be met by other, less intrusive means. Absence of justification for exercising the power of arrest may lead to challenges should the case proceed to court. It could also lead to civil claims against police for unlawful arrest and false imprisonment.

A lawful arrest requires two elements:

- a person’s involvement, suspected involvement or attempted involvement in the commission of a criminal offence; and

- reasonable grounds for believing the arrest is ‘necessary’.

There are a number of statutory criteria set out in Code G of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 regarding what may constitute ‘necessity’. These criteria are exhaustive, and if none are met then the officer has no lawful power to arrest the suspect. It remains an operational decision at the discretion of the officer to decide what circumstances may satisfy those criteria. A police officer cannot be instructed to exercise their power of arrest. Each time the power of arrest is exercised, the person exercising it must have sufficient information available to them to inform their decision.

Analysing the data

HMICFRS collects data on arrests and voluntary attendance in cases of domestic abuse from forces as part of its regular data collections to support PEEL inspections. The available data on voluntary attendance is limited and has only been collected in the past three years. Currently, not all forces record this data. Only 33 of 43 forces gave this data to HMICFRS in 2019/20.

The inability of some forces to report this data raises serious questions about how they are monitoring their own use of voluntary attendance for domestic abuse cases. It also means they are unable to assure themselves or the public that the incidents of apparently inappropriate use of voluntary attendance cited in the super-complaint are isolated.

The police recorded a total of 1,288,000 domestic abuse-related incidents and crimes in the year ending March 2020 (excluding Greater Manchester Police as a result of issues associated with a new crime-recording system). Of these, 758,900 were recorded as domestic abuse-related crimes, an increase of 9 percent from the previous year. However, the Crime Survey for England and Wales saw no significant change in the prevalence of domestic abuse experienced in the year ending March 2020 compared with the year ending March 2019.[footnote 9] The Office for National Statistics suggests that the increase in police-recorded crime may reflect improved recording by the police and increased reporting by victims.

The picture for arrests for domestic abuse shows a similar downward trend to that of arrests for all offences. It is likely that the downward trend began before 2017 as the data for all arrests shown above began to decline from 2008 (this data isn’t available for domestic abuse offences before 2017 because it wasn’t recorded).

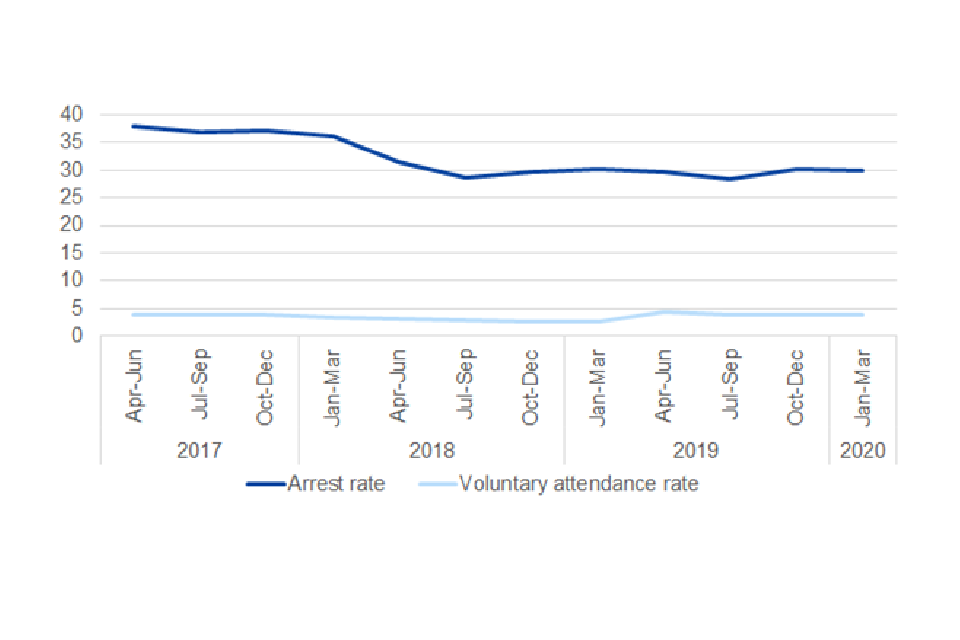

Figure 2: Domestic abuse arrests per 100 domestic abuse crimes and voluntary attendances per 100 domestic abuse crimes, in England and Wales, 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2020

Domestic abuse arrests per 100 domestic abuse crimes decreased from 37 arrests per 100 crimes to 30 arrests per 100 crimes between 2017/18 and 2019/20 in England and Wales.

Source: HMICFRS data collection

From 2017/18 to 2019/20, domestic abuse arrests per 100 domestic abuse crimes decreased from 37 arrests per 100 domestic abuse crimes to 30 arrests per 100 domestic abuse crimes in England and Wales.

The wider context

The pattern shown here for domestic abuse data must be understood in context.

There is a wider trend showing an increase in recorded crime alongside a decline in arrests. In 2017, HMIC considered this trend in PEEL: Police effectiveness 2016: A national overview. It didn’t establish one single cause but pointed to a range of possible factors. One possible factor was resourcing pressures. The centralisation of custody suites (meaning officers may have to travel greater distances to take someone to custody and may be less likely to do this on a busy shift) might also have played a part. Another possible factor was increased use of voluntary attendance.

HMICFRS suggested that the use of voluntary attendance had increased as a result of a more stringent application of the ‘necessity test’ introduced in 2012. According to the test, for an arrest to be lawful there must be reasonable grounds for believing that it is necessary (this is covered in PACE Code G).

In its report of February 2019, entitled The police response to domestic abuse: An update report, HMICFRS documented a reduction of 65 percent in pre-charge bail granted in domestic abuse cases within the first three months of the new bail regime in 2017 compared to the same period in 2016. Annex D explains why this data is unreliable.

Positive action policy

In A progress report on the police response to domestic abuse (2017), HMICFRS expressed concerns about the falling levels of arrests in domestic abuse cases. Most forces have a positive action policy, which means that, in general, the force supports the arrest of a suspect. Any officer deciding not to arrest a suspect would need to justify that decision to a supervisor.

Police officers have a duty to take positive action when dealing with domestic abuse incidents. Often this means making an arrest, provided that the grounds exist, and it is a necessary and proportionate response. Despite clear guidance in the College of Policing Authorised Professional Practice on arrest and other positive approaches, some officers we spoke with felt there was confusion about what positive action involves.

“A decision not to arrest can have symbolic value”

Rights of Women is a charity which specialises in providing legal advice to women who are experiencing, or are at risk of experiencing, violence against women and girls offences, including domestic and sexual violence. It suggested that voluntary interviews give the impression that an offence is not serious. It said: “in our experience, victim-survivors are very sensitive to actions by the police which suggest that they are not believed or taken seriously. A decision not to arrest can have symbolic value.”

In contrast, some research literature states that some victims don’t want their partner to be arrested or prosecuted (see, for example, Hoyle and Sanders, 2000[footnote 10]). There is no consensus in the literature on whether positive arrest and evidence-led prosecution is empowering or disempowering individual victims.

Neither perceptions of the importance of a case nor increasing victim anxiety are on their own acceptable reasons for exercising the legal powers of arrest or use of pre-charge bail. However, Rights of Women believes that a lack of bail conditions causes victims anxiety and that a lack of bail places women at risk.

In situations where a power to arrest exists, police officers must balance multiple considerations. These include the expectation to take positive action and arrest the suspect (and to have the ability to impose pre-charge bail conditions). But the police also need to consider both the necessity to arrest and the victim’s wishes as regards their short and long-term strategies for managing the abuse.

Confusion over proportionality

There are likely to be many contributing factors to the decrease in arrest rates for domestic abuse. One factor highlighted in fieldwork by HMICFRS when investigating the super-complaint was confusion over what constituted necessity and proportionality according to Code G of PACE.

Some frontline officers suggested that if a suspect was not arrested at the time of the offence, the custody officer would be less likely to authorise detention. They explained this was because it is more difficult to show an arrest made (some time) after the offence was necessary and proportionate.

In its super-complaint, the Centre for Women’s Justice states “Police officers may also be applying the law on necessity to arrest incorrectly, falsely believing that where a suspect is willing to attend voluntarily an arrest cannot be carried out”. Our fieldwork showed that most officers were confident that they could arrest someone who had attended voluntarily for interview. But some officers thought they could only meet the necessity test if new evidence had come to light.

The College of Policing has produced eLearning on managing Pre-charge bail and risk on its Managed Learning Environment. It recognises that the decision whether or not to arrest and grant pre-charge bail can influence how risk is managed throughout the rest of the investigation, and sometimes on into court proceedings after a suspected perpetrator has been charged. The learning makes officers aware of how this crucial decision may have a permanent effect on a case.

Situation 2: When suspects are interviewed under arrest, released under investigation without pre-charge bail, or released on pre-charge bail without bail conditions

Decision to apply pre-charge bail

The 2017 changes to legislation on pre-charge bail mean that the police need to go through a more rigorous authorisation process to impose bail on a suspect. Since 2017, there has been a presumption toward RUI unless imposing bail satisfies the ‘necessity’ and ‘proportionality’ criteria. When a person is RUI, they are not (at that time) given any pre-charge bail conditions.

The use of pre-charge bail decreased from approximately 26 percent for those arrested in March 2017 (before the changes to legislation) to 3 percent for those arrested between April and June 2017. This is based on data of a sample of 30 forces provided to the College of Policing. The vast majority of suspects in all cases were RUI. It is likely that similar patterns have been seen for domestic abuse cases, but national data isn’t available to confirm this.

Additionally, before the legislation change in April 2017, Hucklesby (2015) found that bail conditions were applied in approximately two-thirds of the cases involving bail, but this proportion varied widely between forces. Our investigation hasn’t identified or reviewed the detail of these cases, but we anticipate it is likely that conditions were applied in all or a majority of these cases because of their seriousness.

Before the Policing and Crime Act 2017, the police measured and reported on the number of custody records involving a suspect released on pre-charge bail (including unconditional bail). Since 2017, there hasn’t been any reliable nationally published police data on the numbers of suspects RUI.

There are several reasons why the data isn’t accurate. Forces measure pre-charge bail and RUI cases in different ways. For example, some forces count one offender RUI as one, while other forces count each offence RUI. This makes it difficult to aggregate and analyse the data. Some forces can’t identify cases involving RUI because their IT systems can’t flag these cases.

HMICFRS’s 2020 inspection on the use of pre-charge bail and RUI, Striking a balance, found that most forces have well-established recording systems for bail and have a clearer picture of the number of people on bail compared with RUI. However, it found that the systems for recording RUI in most forces are underdeveloped and some forces have no accurate information on RUI cases at all. So not all forces knew for certain how many people are RUI, nor do they have systems in place to identify any emerging trends and patterns.

While HMICFRS saw that some forces are now starting to develop better recording systems to measure and report on RUI and pre-charge bail, these systems have only recently been introduced. Forces were unable to judge how effective these systems were because it was too early to measure this. In one force, a new system had been introduced to record RUI the day before the inspection started in early 2020 – three years after the legislation had been introduced. It wasn’t clear why it had taken so long to introduce this. Annex D contains more information.

This lack of data on the use of RUI is a serious concern. Consequently, one of the recommendations of the Striking a balance report is “the Home Office and the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) should work together to develop and put in place data collection processes to give an accurate national picture of RUI and pre-charge bail”.

Effect of imposing pre-charge bail conditions on victim safety

There is limited available research on the effect of imposing bail conditions on the actual and perceived safety of victims. However, Anthea Hucklesby, in her 2016 evidence to the Home Affairs Select Committee, stated that for the victim applying conditional bail not only went some way towards affirming their value and credibility, but also influenced responses from other agencies, family, friends and communities.

One IOPC/IPCC case was identified that featured issues about imposing pre-charge bail.

Case one

This related to the police investigation of offences committed by a man against his ex-partner, whom he subsequently murdered. The investigation highlighted that although bail conditions were in place, they were arguably not good enough to protect the victim. It found that an officer’s decision to release the man on conditional bail, with stipulation that he should live at his home address (eight doors away from his ex-partner), failed to provide adequate protection for the woman. This case also featured a failure to arrest for breach of bail conditions.

The investigation concluded there was learning for the force around (i) formalising the process between the custody sergeant and the force’s domestic abuse investigation and safeguarding unit in relation to deciding whether to bail a suspect; and (ii) implementing mandatory risk assessments for domestic abuse victims when the suspected perpetrator breaches their bail conditions.

Examples of how failures to impose pre-charge bail can have wide-ranging effects on victims

In its super-complaint, the Centre for Women’s Justice states “A Rape Crisis service reports that it can be more difficult for women to obtain assistance from statutory services such as local authority housing departments because bail is treated as an indication of the seriousness of an offence.”

The super-complaint describes how a woman was advised by several family law solicitors that she wouldn’t be able to obtain legal aid for a family law case because the suspect had not been arrested and put on bail. This was supported by Rights of Women. It agreed that a victim’s ability to obtain statutory services is affected by bail.

In her research on rape victims and their experience of the criminal justice system entitled A system to keep me safe: An exploratory study of bail use in rape cases (2018), which examined both pre and post charge bail, Sarah Learmonth argues that the application and conditions of bail form an important part of procedural justice. She says they’re a social indicator of the validity of the allegation (showing others that the case is valid).

The Home Office completed a literature review on this subject as part of its consultation on pre-charge bail in 2019. It found very little robust evaluative evidence research looking at the extent to which pre-charge bail with conditions affects suspects’ behaviour, increases victims’ sense of security or encourages victims to support investigations. It found some small-scale qualitative research with victims, which suggested bail conditions may help victims feel safer and that there were secondary benefits of bail conditions.

The available qualitative research suggests that victims value bail as an affirmation of their credibility and the validity of their allegation. Sarah Learmonth’s study suggests that the application of bail can influence responses from other agencies, family, friends and communities.[footnote 11] The same study also suggested that the arrangements in place before 2017 reform could sometimes leave victims feeling unsupported in cases where breaches were reported but not acted on.

Government proposals to reform pre-charge bail

In January 2021, the Government published a response to its consultation on pre-charge bail. New measures, which will be introduced via the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill will create a more proportionate system where suspected perpetrators aren’t held on pre-charge bail for unreasonable lengths of time, while enabling police to impose conditions on more suspects in high-harm cases, including cases of domestic abuse and sexual violence. The Home Office has informed us these measures seek to (i) end the presumption against pre-charge bail, instead requiring pre-charge bail to be used where it is necessary and proportionate and (ii) to add a requirement that a constable must have regard to the following factors when considering whether application of pre-charge bail is necessary and proportionate:

- The need to secure that the person surrenders to custody;

- The need to prevent offending by the person;

- The need to safeguard victims of crime and witnesses, taking into account any vulnerabilities of any alleged victim of, or alleged witness to, the offence for which the person was arrested where these vulnerabilities have been identified by the custody officer;

- The need to safeguard the person, taking into account any vulnerabilities of the person where these vulnerabilities have been identified by the custody officer; and

- The need to manage risks to the public.

Reforms included within the Bill will also establish a new duty to inform victims of changes to pre-charge bail conditions and to seek views from victims on what the conditions concerning their safeguarding should be, making sure that victims are more involved and informed in the process. Officers can then take into account any safeguarding concerns that are raised to make sure that appropriate measures are in place.

There will also be a new power for the College of Policing to issue statutory guidance on pre-charge bail to establish consistent practice across all forces.

Breaching pre-charge bail conditions

There are very limited consequences for breaching pre-charge bail, to the extent that it has been referred to as a “toothless tiger” (see for instance Hillier and Kodz’s 2012 research findings, The police use of pre-charge bail). The only action that the police can take when a suspect breaches pre-charge bail conditions is to arrest them again. In most cases, a person can’t be detained in police custody for more than 24 hours without being charged. Being re-arrested for a breach of bail uses up time on the 24-hour PACE clock, which could instead be used for strengthening the primary case against the suspect.

In our fieldwork, some police officers we spoke with told us they have experience of suspects admitting that they don’t take pre-charge bail with conditions seriously. Some officers said this influenced their decision-making on whether to arrest someone, ask them to voluntarily attend for interview, or apply bail conditions if they do make an arrest.

IOPC and IPCC cases

Thirteen IOPC/IPCC cases were identified that featured a failure to arrest for breach of bail conditions. Although this problem isn’t explicitly specified as one of the situations of concern in the super-complaint, these cases are included in this report as they are relevant to the overall subject matter.

There is no single, overarching theme for these cases; however, various problems were identified, including:

- unclear force procedures for progressing actions in relation to breaches of bail;

- confusion around roles in progressing enquiries; and

- lack of relevant training for officers.

In one of the cases identified, a man called the police stating that he was at his partner’s address and needed to be arrested. The man’s first language was not English and he appeared intoxicated, which led to some communication difficulties with the call handler. The call handler sent the incident log to dispatchers and continued to try to gather additional information from the man and his partner. An entry was added to the incident log six minutes later that the man was subject to pre-charge bail conditions. These prohibited him from contacting his partner or visiting her address. The call handler did not add this information to the main section of the incident log and this information was not communicated to the attending officers.

When officers arrived, the man and the woman said that they could not remember calling the police and did not know why they were there. The officers waited outside the property, spoke with neighbours who raised no concerns, and then left the address. In the early hours of the next morning, the police received a report of a disturbance at the same address. On entering the property, the man was found on top of the woman, applying pressure to her neck. The man said that he was trying to kill his partner and he was arrested on suspicion of attempted murder. The man later pleaded guilty to causing grievous bodily harm with intent and assault occasioning actual bodily harm.

The key area highlighted in the investigation was around the call being sent to the dispatcher prior to the call handler obtaining all the information. When the call handler discovered pre-charge bail conditions, they added these to the log, but this did not alert the dispatcher that new information had been added, so the information was not passed onto the police who initially attended. No learning recommendations were made in the investigation because the force had already identified that there was an issue when the log was created – specifically, that new information didn’t show on the main section of the log, meaning that it could be easily missed – and took steps to address this. This was corrected by the force prior to conclusion of the IOPC/IPCC investigation.

Effect of being released under investigation

When a suspect is RUI, there is no statutory timetable for reviewing the investigation and managing them. There is some evidence that this has led to longer investigations in RUI cases. This potentially puts victims at risk of further offences.

HMICFRS’s inspection into pre-charge bail and RUI found that, on average, in the cases assessed the time between arrest and charge was 128 days for pre-charge bail and 201 days for RUI.

HMICFRS also found[footnote 12] that forces don’t have adequate data systems in place to monitor the number of suspects on bail versus RUI, or the number of cases which move from bail to RUI. This means that the management of suspects under investigation isn’t always monitored as closely as it should be.

The available national data on investigation lengths shows that investigation times for some categories of offence is getting longer. But this is not consistent across all offences. However, for domestic abuse offences, in the years following the change in the bail legislation, there was a noticeable decrease in the proportion of offences where the investigation was finalised within five days.

Figure 3a: Proportion of domestic abuse-related offences assigned an outcome within a certain timeframe (years ending March 2017 to March 2020)

| Time taken (days) | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Same day to 5 days | 28% | 32% | 28% | 28% |

| 6 to 30 days | 34% | 31% | 33% | 28% |

| 31 to 100 days | 28% | 26% | 27% | 28% |

| More then 100 days | 9% | 11% | 13% | 17% |

Source: ONS Domestic abuse in England and Wales

Figure 3b: Proportion of non-domestic abuse-related offences assigned an outcome within a certain timeframe (years ending March 2017 to March 2020)

| Time taken (days | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Same day to 5 days | 43% | 49% | 48% | 46% |

| 6 to 30 days | 26% | 24% | 23% | 26% |

| 31 to 100 days | 22% | 19% | 19% | 18% |

| More than 100 days | 9% | 8% | 9% | 10% |

Source: ONS Domestic abuse in England and Wales

Note for figures 3a and 3b: figures for 2020 are based on returns to the Home Office datahub by 29 forces, for 2019 37 forces, for 2018 29 forces, and for 2017 24 forces

In its literature review for the pre-charge bail consultation, the Home Office found that for all offences the average (median) time taken to charge suspects has gradually increased from 14 days in 2015/16 to 23 days in 2018/19 (Home Office, 2019).