Post-legislative scrutiny of the Criminal Finances Act 2017: Memorandum to the Home Affairs Committee (accessible version)

Published 21 May 2024

May 2024

CP 1088

Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for the Home Department by Command of His Majesty

Introduction

This memorandum provides an assessment of the Criminal Finances Act 2017 and has been prepared by the Home Office for submission to the Home Affairs Select Committee. It is published in accordance with the guidance document ‘Post-legislative Scrutiny – The Government’s Approach’.

Objectives of the Criminal Finances Act 2017

The Criminal Finances Act 2017 (CFA, the Act) was introduced to amend the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (POCA) and received Royal Assent on 27th April 2017. The Act applies UK wide. It gave law enforcement bodies new powers and capabilities to recover the proceeds of crime and combat money laundering, corruption and terrorist financing. The Act also seeks to improve cooperation between the public and private sector with regards to reporting and information sharing. It extends powers to the Terrorism Act 2000 (TACT) and the Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 (ATCSA) and creates new corporate offences of failing to prevent facilitation of tax evasion.

The Act forms part of the UK’s wider response to tackling economic crime and helps to meet objectives set out in the Serious and Organised Crime Strategy 2013 and Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015 to make the UK a more hostile place for those seeking to move, hide or use the proceeds of crime and corruption.

Elements of the Act have been subsequently reformed through the Economic Crime (Transparency and Enforcement) Act 2022 (ECTE), these changes will be reflected in the legal challenges and preliminary assessments of relevant chapters. Additional changes to POCA intended to strengthen the UK’s legislative response to economic crime are contained in the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act 2023 (ECCT). Some of the provisions in ECCT reform powers introduced by the Act – these are also reflected in the relevant sections below.

The Act is set out in four parts; part one pertains to the proceeds of crime, money laundering, civil recovery, enforcement powers, seizure and information sharing. Part two extends relevant powers to TACT and ATCSA. Part three creates two new corporate offences of failure to prevent the facilitation of tax evasion. Part four contains miscellaneous amendments to POCA and other legislation. The provisions of the Act are summarised as follows;

- Introduction of unexplained wealth orders (UWOs)

- Expansion of disclosure orders

- Provisions mandating an annual review of the Exchange of Notes arrangement maintained with the Crown Dependencies and Overseas Territories for the sharing of beneficial ownership information

- Strengthening the suspicious activity reports (SARs) regime

- Provisions strengthening information sharing in the regulated sectors

- Expansion of seizure powers to property obtained as a result of gross human rights abuses

- Expansion of property that can be seized and government bodies that can carry out seizure

- Introduction of account freezing orders and account forfeiture notices

- Measures relating to the investigation and seizure of terrorism related offences and property

- Introduction of a failure to prevent facilitation of tax evasion offence

The Home Office has issued a number of circulars regarding the Act, some of which are formal guidance, some of which do not constitute legal guidance, a number of formal codes of practice were also published.

Table 1: Organisation of this post-legislative scrutiny memorandum

| Provision | Page |

|---|---|

| Part 1 – Proceeds of Crime – Chapter 1, Investigations | 3 – 8 |

| Part 1 – Proceeds of Crime – Chapter 2, Money Laundering | 9 - 12 |

| Part 1 – Proceeds of Crime – Chapter 3, Civil Recovery | 13 – 18 |

| Part 1 – Proceeds of Crime – Chapter 4, Enforcement powers and related offences | 19 – 21 |

| Part 1 – Proceeds of Crime – Chapter 5, Miscellaneous | 22 – 26 |

| Part 2 – Terrorist Property | 27 – 29 |

| Part 3 – Corporate offences of failure to prevent facilitation of tax evasion | 31 – 34 |

| Part 4 - General | 35 – 36 |

| Conclusion | 37 |

Part 1 – proceeds of crime

Chapter 1: Investigations

Sections 1-9

Introduction

1. Part one of the Act is focussed on strengthening the law enforcement response to money laundering and corruption and increasing the retrieval of proceeds of crime. This is in line with the recommendations of the 2015 money laundering and terrorist financing National Risk Assessment (NRA) and Action Plan for money laundering and counter-terrorist finance of 2016. Subsequently published documents and strategies, including the 2017 and 2020 NRA, Economic Crime Plan 2019-2022, Economic Crime Plan 2 2023-2026, UK Anti-Corruption Strategy and the Asset Recovery Action Plan all emphasise the importance of recovering proceeds of crime from criminals and the corrupt, ensuring that law enforcement has the appropriate tools and that the private and regulated sectors are actively engaged. The war in Ukraine has also served to re-emphasise the importance of being able to investigate and seize criminally obtained property and ensuring that the UK financial sector and wider economy is protected from illicit finance.

Provisions

2. Sections 1-6, unexplained wealth orders (UWOs): the Act amends Part 8 of POCA, making provision for the court to grant unexplained wealth orders. UWOs are an investigative tool that aim to help agencies gather crucial information at the outset of an investigation where they may otherwise be unable to do so (for example, due to an inability to rely on full cooperation from other jurisdictions). A UWO requires a person who is suspected on reasonable grounds of involvement in, or of being connected to persons involved in, serious criminality to provide information about the assets which are the subject of the order. This information may include details about the origin of the assets that appear to be disproportionate to the person’s known legitimate income or appear to have been obtained through unlawful conduct. A UWO can also be made against a “politically exposed person” from a non-European Economic Area state. Information supplied using a UWO can be used for subsequent civil recovery proceedings (UWOs are not, themselves, a recovery mechanism).

3. If the respondent fails ‘without reasonable excuse’ to comply or purport to comply with the requirements imposed by the UWO, the property is presumed to be recoverable property for the purpose of any proceedings under Part 5 of POCA unless the contrary is shown. When the Court is asked to make a UWO, they may also be asked under section 2 to make an interim freezing order (IFO), to prevent any person with an interest in the property from dealing with it in any way. This prevents the sale or transfer of the property so that it does not become beyond the reach of law enforcement during the investigation and so defeat any final asset recovery order that may be made. The combined value of the assets that a UWO is taken out against must total at least £50,000.

4. Sections 7-8, disclosure orders: the Act extends the use of disclosure orders (contained in Part 8 of POCA) to money laundering cases and expands the category of persons who may apply for a disclosure order in a confiscation investigation. Disclosure orders allow an authorised law enforcement officer to require anyone they believe has information relevant to an investigation to answer questions, provide information or produce documents. These had previously been used by the Serious Fraud Office (SFO) in fraud investigations, for example. The Act extends their use to money laundering investigations in order to better enable law enforcement access to relevant and necessary information.

5. Section 9, beneficial ownership: requires that the Minister prepare a report into the Exchange of Notes arrangement operated between the UK and the Crown Dependencies and Overseas Territories that requires the exchange of beneficial ownership information upon request by law enforcement.

Implementation

6. The powers contained in this section of the Act came into in effect in England, Wales and Scotland on 31st January 2018. In Northern Ireland the Assembly dissolved before a Legislative Consent Motion could be debated and consequently only provisions that related wholly to reserved or excepted matters were commenced in line with England and Wales. The remaining relevant provisions of the CFA 2017 were commenced in Northern Ireland on 28th June 2021. The provisions of the Act are now in full effect across the UK.

7. The Statutory Review of the Exchange of Notes arrangements required by the Act was published in June 2019. It found that the arrangements had been extremely useful for UK law enforcement with 296 requests being made in the initial 18-month period covered by the review, and noted that improvements had already been made since an initial six month review. Internal reviews (that were not mandated by the Act) have also been carried out for the calendar years 2019- 2021 and have continued to find a good volume of requests for information being answered in a speedy timeframe in support of law enforcement investigations.

Secondary Legislation

8. The required Exchange of Notes report is set out above in implementation and subsequent changes made to UWOs under the ECTE are set out below under legal issues.

9. The Home Office issued a circular outlining basic definitions for UWOs and IFOs, this does not constitute legal advice or formal guidance. A circular was also issued to raise awareness and understanding of disclosure orders as amended, this does not constitute legal advice or guidance.

10. The Secretary of State for the Home Department (the Secretary of State), using powers granted under sections 58 (1) and (7) of the Act on 20th January 2018 introduced regulations giving effect to sections 1-8 of the Act from 31st January 2018.

| Related regulations/guidance | Purpose | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Criminal Finances Act 2017 (Commencement No.4) No.78 | To give effect to sections 1-8 of Part one of the Act | Made: 20 January 2018 In effect: 31 January 2018 |

Legal issues

11. As a substantive new investigative power designed to target individuals with significant wealth, there was an expectation that the regime would face strong legal challenge. The National Crime Agency (NCA) is currently the only law enforcement agency to have utilised the powers. Prior to the passage of ECTE, the NCA had successfully obtained four UWOS through the courts, with one resulting in subsequent seizure worth £10 million. However, a UWO was successfully discharged by the court in the case of NCA vs Baker & Ors (2020). Mrs Justice Lang ruled that an order for discharge should be made on a number of grounds including; that the case presented by the NCA at the ex parte hearing was flawed by inadequate investigation into some obvious lines of enquiry; and that there was an error in applying POCA section 362B – the “income requirement” – to Mr Baker as the president of the company owning the property.

12. Following that decision, HMG considered a range of options to reform UWOs, a number of which were subsequently adopted by the Government and introduced in the ECTE.

13. Reforms introduced by ECTE removed key barriers to the use of UWOs and enabled these powers to be used more effectively and in relation to property held via complex ownership structures. These changes (set out in paragraphs 14-18) also clarified the law, making it easier for law enforcement to use.

14. Interim freezing orders – ECTE increased the maximum time available to law enforcement to review material provided in response to a UWO before a corresponding freezing order expires by allowing the High Court to extend a UWO and IFO for an additional 126 days beyond the initial investigating period. Extensions are dependent on the Court being satisfied that the enforcement authority is working diligently and expeditiously towards making a determination. This creates a potential review period totalling 186 days.

15. Introduces ‘responsible officers’ as recipients of UWOs - ECTE adds a new category of individual who may be specified under a UWO to include a ‘responsible officer’ where the respondent is not an individual (for example, a company). This allows UWOs to be raised against responsible officers of the property-owning entity (for example a director, company secretary or partner of the company), requiring them to provide information on property ownership. This can be particularly useful to law enforcement where the property is owned by an overseas corporation. In effect, this makes it more difficult for individuals to hide behind complex corporate structures.

16. Introduces a new income requirement – this new requirement enables a UWO to be made where the court is satisfied that there are reasonable grounds for suspecting that the property has been obtained through unlawful conduct. This provides an alternative to the original requirement that the property owned be beyond the legitimate income of the individual. This allows UWOs to better apply to corporations and relevant officers who hold information on the property but may not have the requisite income that corresponds to the relevant property. Law enforcement will now be able to use either requirement when applying and arguing before the Court.

17. Amends the cost rules on UWOs – places a limit on the costs liability of an enforcement authority to a respondent unless the enforcement agency acted unreasonably in raising the UWO or acted dishonestly or improperly in the course of the proceedings.

18. Introduces a requirement to report on the use of UWOs in England and Wales annually - The Secretary of State must publish and lay before Parliament an annual report that sets out the number of UWOs made by the High Court in England and Wales and the number of applications made to the High Court for UWOs in that 12-month period. The first report was published on 21st September 2023.

Other reviews

19. The measures in the Act, and in Sections 1-9 specifically, have attracted significant levels of interest both within and outside government. UWOs were of particular interest to Parliamentarians and civil society groups engaged with corruption, kleptocracy and illicit finance issues. Chatham House, the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), various select committees and a number of academics have all engaged with the provisions of the Act and a brief overview of publications is set out in paragraph 20.

20. Chatham House reviewed the use of UWOs in its 2021 report ‘The UK’s Kleptocracy Problem’, noting that none had been used against Russian targets. The Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office funded Anti-Corruption Evidence research programme also examined UWOs in the context of corruption investigations in ‘Criminality Notwithstanding’, carrying out a detailed review of the NCA vs Baker case, criticising both the NCA and Mrs Justice Lang. RUSI hosted a panel discussion on the future of UWOs in response to the NCA vs Baker ruling whilst Spotlight on Corruption published a blog on the same subject. In its report of June 2022 entitled ‘The cost of complacency: illicit finance and the war in Ukraine the Foreign Affairs Committee reflected that law enforcement agencies would need to be given greater resourcing in order to more effectively use the reformed power whilst criticising the lack of their use thus far.

Preliminary Assessment

21. UWOs have been granted in four cases since their introduction with one leading to an eventual recovery of assets (worth £10 million), and two applications having been made (and are pending) since the passage of ECTE.

22. HMG continually evaluates and improves the way our powers interact, and significant changes have subsequently been made which are intended to enable law enforcement agencies to more effectively utilise UWOs’ potential. The scale of future use will be determined by operational requirements and law enforcement tactics and even a single UWO can have a high impact.

23. It should be noted that UWOs were only intended to be used in a small number of cases. Other investigatory tools contained in POCA (including those introduced elsewhere in the CFA) have widespread use as appropriate (ongoing high rates of recovery are detailed principally at Part One Chapter Three of this report). UWOs’ principal value is in obtaining information which would not otherwise be accessible by requiring the subject to prove a legitimate source of income. If, however, exculpatory evidence is provided that law enforcement believes is false or inaccurate there remains a challenge in proving this where the information is, for example, sourced from an un-cooperative foreign jurisdiction.

24. As noted above the Statutory Review of the Exchange of Notes arrangements was published in 2019 and found that the arrangements were working well and supporting UK law enforcement investigations. Reviewing the performance of the arrangements has brought out positive feedback and helped to evidence the usefulness of beneficial ownership information to law enforcement investigations.

25. Disclosure orders are being increasingly effectively used by law enforcement who report that they are an extremely useful tool for investigators. Whilst these orders are being effectively used by law enforcement, due to the nature of the powers contained within these orders there is additional scrutiny on these applications from the Courts and respondents. In part as a consequence of this, production orders also remain a popular tool.

Chapter 2: Money Laundering

Sections 10-12

Introduction

26. A significant challenge in prosecuting money laundering and corruption offences and carrying out criminal and civil non-conviction based recovery of the proceeds of crime is the lack of information available to law enforcement and prosecutors. The provisions in these sections of the Act were intended to make it easier for agencies to assess information provided to them by the regulated sectors by i) extending the time available to assess suspicious activity reports (SARs, which are a valuable source of financial intelligence and information) and ii) making it possible for companies to share information between each other where appropriate and submit that information in a collected package. The Act also enables law enforcement officers to apply for Further Information Orders which require respondents to provide information specified in the order. This is in line with the goal of facilitating greater recovery of the proceeds of crime and increasing law enforcement’s access to information held by the private sector.

Provisions

27. Section 10, power to extend moratorium period: when a regulated entity (i.e. one that is subject to the money laundering regulations) suspects that by undertaking a particular act for a client (for example, processing a payment or providing professional services) they would be committing one of the principal money laundering offences they must make an authorised disclosure, known as a defence against money laundering SAR (DAML SAR). This provides the entity with a defence against potential money laundering offences. The NCA’s financial intelligence unit (UKFIU) will then investigate the transaction and are empowered to grant or refuse consent to the transaction proceeding. Law enforcement previously had a maximum 31 day ‘moratorium period’ (following a maximum 7 calendar day notice period) to investigate the transaction in order to determine whether or not to grant or refuse consent. The Act enables law enforcement or the NCA to apply to renew the 31 day moratorium period for up to 31 days. Applications for renewals can take place six times, creating the potential for a total extension of 186 days after the end of the initial 31 day period. The Act also allows the NCA to seek an order compelling the provision of further information from persons in the regulated sector following the receipt of a SAR.

28. Section 11, sharing information in the regulated sector: the Act allows firm to firm information sharing where the firms have informed the NCA that they suspect that money laundering is taking place, it also allows firms to submit joint SARs, bringing together information from a range of organisations.

29. Section 12, further information orders: the Act allows the NCA to seek a further information order compelling the provision of information from a person in the regulated sector in relation to a matter arising from a disclosure made under Part 7 of POCA (a SAR disclosing knowledge or suspicion of money laundering) or arising from a corresponding disclosure in a foreign jurisdiction where an external request for that information has been made to the NCA.

Implementation

30. The powers and amendments contained in sections 10-12 came into effect in England, Wales and Scotland on 31st October 2017. In Northern Ireland only sections 11 and 12 came into operation on the 31st January 2018 while section 10 came into force on 28th June 2021. The delay in implementation of the Act in Northern Ireland was due to the suspension of the Assembly being between 2017 and 2020. It was not possible to seek a Legislative Consent motion for the Bill before Royal Assent and therefore only provisions that related wholly to reserved or excepted matters were commenced in line with England and Wales until agreement was reached in 2020 to work towards the full implementation of the Act in Northern Ireland. The provisions of the Act are now in force UK-wide.

31. ECCT includes provisions that reform further information orders (referred to as ‘information orders’). These new provisions allow the NCA to proactively seek new information orders without the previous requirement of having received a SAR.

Secondary Legislation

32. The Home Office issued a circular that sets out guidance for the sharing of information under these provisions. A circular was also issued regarding the extension of the moratorium, this does not constitute legal advice.

33. The Secretary of State, under powers conferred by section 58(1), (7) and (8) issued regulations giving effect to provisions 10-12.

| Related regulations/guidance | Purpose | Date of issue |

|---|---|---|

| The Criminal Finances Act 2017 (Commencement No.2 and transitional provisions) No.991 | To give effect to provisions 11-12 of this part of the Act. | Made: 12th October 2017 In effect: 31st October 2017 |

| The Criminal Finances Act 2017 (Commencement No. 3) No.1028 | To give effect to section 11 of this part of the Act. | Made: 25th October 2017 In effect: 31st October 2017 |

Legal issues

34. No significant legal issues have been encountered with the use of the provisions in this part of the Act.

Other reviews

35. In January 2022 the Treasury Committee published a report entitled ‘Economic Crime’ this was a wide ranging review which touched upon the progress of the SARs reform programme, emphasising the importance of SARs but did not directly reference the changes made to SARs in these sections of the Act.

36. In 2019 the Law Commission published “Anti-Money Laundering: the SARs regime” which provided a range of recommendations to amend POCA and the Terrorism Act 2000 with a focus on the SARs reporting process. It notes that an extended moratorium period and account freeze can have a significant negative economic impact on an individual or business, including in cases where only a proportion of the funds in the relevant account are being investigated. ECCT addresses this issue by introducing an exemption allowing a person carrying on business in the regulated sector to act on behalf of a person suspected of being in possession of criminal property where the value of the funds or property available is higher than the value of the suspected funds.

37. For example, an individual may receive a legitimate monthly salary from their employer and have £2,000 from this salary in their bank account. The individual then makes what the bank suspects to be a fraudulent loan application and receives a further £3,000. The account now contains £5,000. Using the exemption, the bank can allow the customer access to up to £2,000 of their funds without submitting a DAML SAR, as long as a minimum of £3,000 (the value of the suspected criminal funds) is maintained by the bank. If the customer wanted to withdraw £2,500, taking the balance to £2,500, an authorised disclosure would be required on the £500 that would take the balance below £3,000.

38. Additionally, the threshold beneath which banks, electronic money institutions and payment institutions can make payments to individuals whose funds are being investigated or have been frozen for reasonable living expenses was raised via Statutory Instrument from £250 to £1,000 in December 2022.

Preliminary Assessment

39. Extensions to moratorium periods have been used more than 200 times by a range of law enforcement partners and have contributed to over £100 million of criminal funds being denied to criminals. The measure is clearly, therefore, performing an important function in allowing law enforcement to better identify, freeze and reclaim illicit funds and is working as intended.

40. Law enforcement have noted that the requirements of the extensions are relatively complex and resource intensive; in complex cases a financial investigator is needed to draft an application for every month of an extension, often soon after the approval of the previous extension. Allowing multiple month extensions could alleviate this pressure (whilst staying within the overall timeframe), although this is not permitted under current legislation. Additionally, the requirement to inform a subject that a moratorium extension is being sought effectively advises the subject that there is law enforcement interest in the funds, which means that extension applications may not be suitable in cases which involve covert operations.

41. Less use has been made of the information sharing provisions in section 11; despite the measure being an industry request, between 2020 and 2021 the UKFIU is only aware of four occasions when businesses made the UKFIU aware of their intention to utilise the provisions, with one instance of a submission being made. However, alternative routes of information sharing are available to businesses (for example, individual reports and the Joint Money Laundering Intelligence Taskforce) and additional changes in ECCT seek to further improve information sharing within the regulated sector and with law enforcement and may also encourage further use of the route for joint submissions provided here.

Chapter 3: Civil Recovery

Sections 13-16

Introduction

42. The UK has one of the world’s largest and most open economies, and London is one of the world’s most attractive destinations for overseas investors. These factors make the UK attractive for legitimate business, but also expose the UK to money laundering risk and flows of both domestic and international illicit and criminal finance. Most notably the provisions in these sections empower law enforcement agencies to seize and recover certain items of valuable property and freeze and recover assets in bank and building society accounts where they are recoverable property (obtained through unlawful conduct) or intended for use in unlawful conduct. It also allows for recovery of the proceeds of gross human rights abuses such as torture.

Provisions

43. Section 13, human rights abuses and violations: the Act extends the existing civil recovery powers in POCA to allow the recovery of property that has been obtained as the result of gross human rights abuses and violations undertaken by public officials outside the UK.

44. Sections 14, forfeiture of cash: Chapter 3 of Part 5 of POCA contains cash seizure provisions which allow law enforcement agencies to seize items including cash, cheques and bearer bonds, where they believe that they are recoverable property, or are intended for use in unlawful conduct. The Act inserts three new items to the list of items which may be seized under these provisions; betting slips, gaming vouchers and fixed value tokens.

45. Section 15, forfeiture of moveable property: expands on cash seizure powers to provide for seizure of a range of personal or moveable property (known as ‘listed assets’ and including items such as precious stones, watches and art) that are recoverable property or intended for use in unlawful conduct. Property must be of a value of £1,000 or above to be seized under this power. Also sets out procedures for seizure, storage/detention, release of property and other relevant protections. Requires that a report (the ‘appointed person report’) be published at the end of the financial year in relation to the exercise of the powers where they were approved by a senior officer set out under this section of the Act, when either no property is seized, or where property is initially seized but not detained after 48 hours by order of the court. This is a pre-existing requirement under POCA that has been expanded to cover the new powers introduced under the Act and is provided by England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland separately.

46. Section 16, forfeiture of funds in banks and building society accounts: introduces account freezing orders (AFOs) and account forfeiture notices (AFNs) in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. These are significant powers that allow law enforcement to freeze and subsequently seize the contents of bank accounts where they reasonably suspect the contents of the account are recoverable property or are intended by any person for use in unlawful conduct. The sections also set out the appropriate administrative and legal processes and various protections and routes for appeal. Scotland does not have an administrative forfeiture scheme but rather uses AFOs following application to the Sheriff Court.

Implementation

47. The powers and amendments contained in the Act, including the AFO and AFNs discussed here, came into in effect in England, Wales and Scotland on 31st January 2018, with these provisions coming into force on 28th June 2021 in Northern Ireland. The provisions of the Act are now in force across the UK, although AFNs are not used in Scotland.

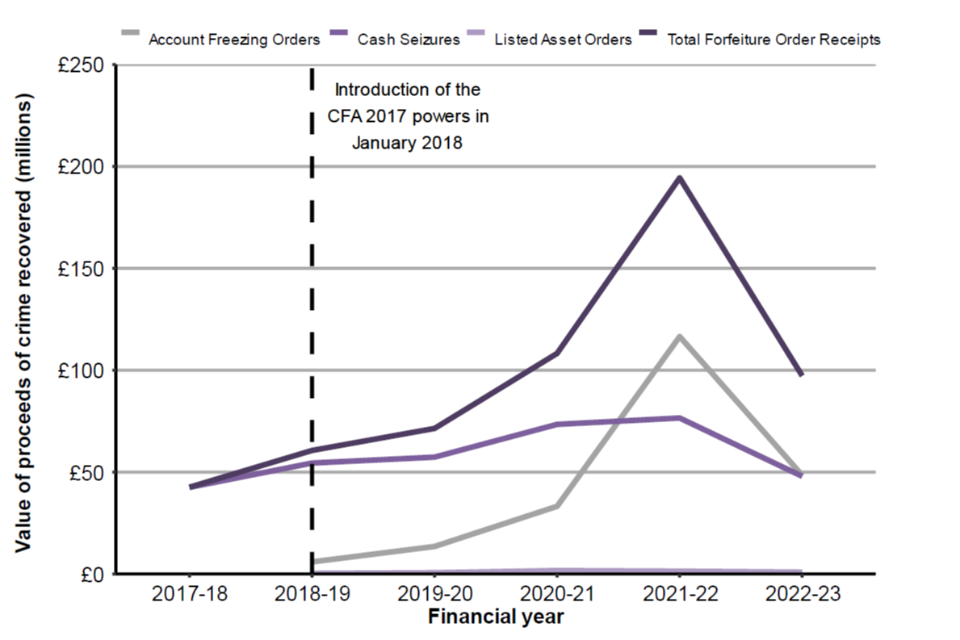

48. AFOs and AFNs have been issued in large numbers since their introduction and have become more widely used by law enforcement agencies as the powers have matured and familiarity has risen. In the financial year 2021/22, £113.7 million was recovered via AFNs in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, this was the highest amount recovered in the preceding six years. In financial year 2022/23 £52.2 million was recovered through AFN receipts. Whilst this represented a 54% decrease from 2021/22, it is a 15% increase from the six-year median amount recovered with the decline related to lower numbers of high value (£1 million or greater) cases.

49. Listed asset forfeiture powers have also been used by a range of law enforcement partners, although less commonly than AFOs and AFNs. Practical issues around storage of goods and realisation of value have been identified although these issues have not proven fundamentally detrimental to their use.

50. The appointed person reports have been published and are available online, for England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Secondary Legislation

51. The Secretary of State was required to draw up a code of practice regarding the use of search powers in consultation with the Attorney General (as the Minister responsible for the Serious Fraud Office). Scottish Ministers and the Department of Justice in Northern Ireland Minister were also required to update and produce new codes of practice in the context of devolved powers and law.

52. The Secretary of State also introduced a consequential amendment under powers granted by section 54(1) and (5) of the Act. Which inserted a reference to section 303R of POCA into section 278(7) of POCA. Section 278(7) ensures that a previous forfeiture order is to be treated as a previous recovery order in respect of forfeited property for the purposes of section 278(3). These amendments ensure that forfeiture orders made under section 303R (which empowers the High Court or Court of Session to order forfeiture of listed personal and moveable property) are captured.

53. The Secretary of State, under powers conferred by section 58(1), (7) and (8) issued regulations giving effect to provisions 13-16.

54. The Home Office has issued a range of circulars intended to ensure consistency in the application of the provisions of this chapter, this does not constitute legal advice.

| Related legislation/guidance | Purpose | Date of issue |

|---|---|---|

| The Criminal Finances Act 2017 (Commencement No.2 and transitional provisions) No.991 | To give effect to provision 15 of this and part of the Act. | Made: 12th October 2017 In effect: 31st October 2017 |

| Criminal Finances Act 2017 (Commencement No.4) No.78 | To give effect to sections 13-16 of this part of the Act. | Made: 20th January 2018 In effect: 30th January 2018, 31st January 2018 16th April 2018 |

| The Criminal Finances Act 2017 (Consequential Amendment) Regulations 2018, No. 80 | Inserts section 303R to section 278 of POCA. | Made: 20th January 2018 Into force: 31st January 2018 |

| Code of practice issued under section 303g of the proceeds of crime act 2002 Recovery of Listed Assets: Search Powers | The purpose of the code is to guide law enforcement officers in relation to the exercise of certain powers under Part 2 of POCA. | January 2018 |

| Search powers conferred by sections 289 and 303C of the Proceeds of Crime Act: code of practice | A code of practice on search powers for cash and listed assets under sections 289 and 303C of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, for constables in Scotland | February 2018 |

| Code of practice issued under section 195s of the proceeds of crime act 2002 search, Seizure and Detention of Property (Northern Ireland) | The purpose of this code is to guide officers in relation to the exercise of certain powers, the code has been issued to reflect amendments to POCA arising from the commencement of the Criminal Finances Act 2017 in Northern Ireland. | June 2021 |

| Code of practice issued under section 377a of the proceeds of crime act 2002 investigative powers of prosecutors | The code provides guidance to officers of the SFO and Director of Public Prosecutions in England and Wales and Northern Ireland regarding powers they hold under chapter 2 of part 8 of POCA. | June 2021 |

Legal issues

55. AFOs and AFNs have encountered some legal challenges in the normal course of legal proceedings, however, these have not substantively affected their use.

56. The Financial Services Act 2021 amended POCA further, in order to make provision for AFO powers (as inserted by the CFA) to also apply to money held in accounts maintained by Electronic Money Institutions (EMIs) and Payment Institutions (PIs). These changes applied in England, Wales and Scotland. At that time, it was not possible for the Northern Ireland Executive to secure the legislative consent motion (LCM) required to make the changes there. Subsequently, the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 harmonises account freezing and forfeiture provisions across the UK by ensuring that they can be used in respect of accounts maintained with Electronic Money Institution and Payment Institutions in Northern Ireland.

Other reviews

57. AFOs and AFNs were widely welcomed upon their introduction despite being somewhat less high profile than UWOs at launch. In its paper ‘The UK’s Kleptocracy Problem’, RUSI stated and welcomed the fact that AFOs (and by implication AFNs) have been used against the assets of a number of high risk, politically exposed persons.

58. The civil society organisation Spotlight on Corruption has also written (Account freezing orders: law enforcement’s ace of spades favourably about AFOs and AFNs, noting their extensive use by a range of law enforcement agencies whilst noting criticism of their lack of protections and a low drumbeat of legal challenges.

Preliminary Assessment

59. Account freezing orders and forfeiture notices have been one of the most successful aspects of the Act; delivering a significant and sustained increase in the proceeds of crime that have been recovered by law enforcement through their use, as shown in Table 2 below (and set out in greater detail in the ‘Asset recovery statistical bulletin published September 2023). In England, Wales and Northern Ireland, during the financial year 2022/23, £141.8 million was frozen using AFOs with proceeds of crime recovered from forfeiture orders under this seizure sub-type worth £52.2 million.

60. It has been noted by both external and internal stakeholders that part of the basis of the success and operational popularity of AFOs is their simplicity and ease of use. That there is a lower value threshold on their use (£1000) and that applications for them are heard in magistrates’ or Sheriff Court rather than the High Court or Court of Session compares favourably with UWOs. Prior to the reform of UWOs, AFOs were also differentiated by a presumption against granting expenses against improper applications where the agency had behaved properly in its application. This advantage has now been extended to UWOs.

61. The orders are, however, limited to bank and building society accounts, electronic money institutions and payment institutions (the final two due to further amendments to POCA in the Financial Services Act 2021 and extended to Northern Ireland under the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 detailed above). They cannot, therefore, be used to freeze high value personal property or services (although property can be recovered provided it falls into one of the listed assets categories and is of sufficient value).

62. Seizures of property identified in the listed assets criteria have taken place in a number of different cases and have included gold bars, gold shavings, watches, art and high value jewellery. These seizures reflect the range of assets that are available for seizure and law enforcement willingness to use the tool where awareness and understanding is strong. Given the prestigious nature of many of these items this also reflects a serious harm for criminals whose illegal activities have mainly economic motivation that manifests in outward signs of wealth.

63. There have been some practical issues around the storage and disposal of seized assets, including realising the value of assets held. One example being face-value vouchers which auctioneers refuse to list for sale. The National Economic Crime Centre (NECC) has developed a training package for law enforcement partners that aims to further raise awareness of listed asset orders and outline some solutions to practical concerns and a series of roadshows have been delivered across the country to raise awareness of the package and listed asset powers.

Table 2

The value of proceeds of crime recovered from financial year 2017 to 2018 until financial year 2022 to 2023 in England and Wales, Northern Ireland jurisdictions and those with no recorded jurisdiction

Source: Asset recovery statistical bulletin; Joint Asset Recovery Database and NCA

Chapter 4: Enforcement powers and related offences

Sections 17-25

Introduction

64. Chapter 4 extends investigatory, freezing, forfeiture and civil recovery powers under POCA to the SFO, His Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC), the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and immigration officers as appropriate in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. It also extends to HMRC powers previously held by the Inland Revenue. It also creates the new offence in England Wales and Northern Ireland of assaulting a law enforcement officer in the process of their duties pertaining to the use of POCA powers and search and seizure warrants. It also allows the Secretary of State to observe rulings by foreign courts that pertain to asset freezing and seizure.

Provisions

65. Sections 17-21, extension of powers: extends certain powers and provisions to necessary SFO staff, HMRC, the FCA and immigration officers allowing them access to certain investigatory and recovery powers that they had previously lacked. In Scotland, these sections extend powers and provisions to officers of HMRC and immigration officers, whilst Scottish Ministers are the sole enforcement authority for civil recovery.

66. Sections 22, 23 and 25, assault and obstruction offences: makes assault or wilful obstruction of an appropriate person carrying out search or seizure under POCA an offence. This offence does not apply to Scotland, where law enforcement officers use common law powers in such circumstances.

67. Section 24, external requests, orders and investigations: amends sections 444 and 445 of POCA, which give the Secretary of State the power to make provisions (by way of Orders in Council) in respect of orders made by an overseas court.

Implementation

68. The provisions in this chapter of the Act are now in effect as of 31st January 2018, noting delayed implementation on Northern Ireland outlined elsewhere. There has not, as of September 2023, been a prosecution under the assault or wilful obstruction offence.

Secondary Legislation

69. The Secretary of State, under powers conferred by section 58(1), (7) and (8) issued regulations giving effect to provisions 17 and 21-25.

| Related legislation/guidance | Purpose | Date of issue |

|---|---|---|

| The Criminal Finances Act 2017 (Commencement) No.2 and transitional provisions) No.991 | To give effect to section 17 of this part of the Act. | Made: 12th October 2017 In effect: 31st October 2017 |

| Criminal Finances Act 2017 (Commencement No.4) No.78 | To give effect to sections 17 and 21-25 of this part of the Act. | Made: 20th January 2018 In effect: 30th January 2018, 31st January 2018 |

Legal issues

70. No significant legal issues have been encountered with these provisions. Any wider issues with the provisions of the Act experienced by the organisations referenced in this chapter are set out in the chapters relevant to those provisions.

Other reviews

71. In 2022 the Treasury Committee issued a report – ‘Economic Crime – in which it expressed some scepticism as to the value of extending powers relating to money laundering to HMRC and recommended that the arrangement be reviewed in His Majesty’s Treasury’s (HMT) ‘Review of the UK’s AML/CFT regulatory and supervisory regime’. In the review HMT responded to the committee’s comments noting improvements in HM C’s risk-based approach to supervision and made no suggestion to rescind the body’s anti-money laundering role.

72. Adam Craggs, Partner and Head of Tax Disputes at RPC has said that “HM C now has extensive powers to seize assets under investigation and it appears to be looking at every opportunity to exercise those powers”. There is also an expectation that the body will use the powers granted to pursue fraud carried out against the government’s emergency response to Covid-19.

Preliminary Assessment

73. The extension of powers to the SFO, HMRC, FCA and immigration enforcement has resulted in freezing and seizures of criminal property by all of those bodies. This includes a £2 million forfeiture order by the FCA, a £500,000 order from the SFO and HMRC issuing 166 freezing orders in financial year 2019/20. The ability to use these powers has been welcomed by the heads of those agencies with Mark Steward, former Executive Director of Enforcement and Market Oversight at the FCA, saying “Account forfeiture orders are an important means of intervening and capturing illegal money”.

Chapter 5: Miscellaneous

Sections 26-34

Introduction

74. Chapter 5 ensures that the substantive provisions of the Act are made available to law enforcement agencies across the UK as appropriate and in line with the arrangements of the devolved governments and their various competencies.

Provisions

75. Sections 26-27, seized money, England, Wales and Northern Ireland: section 67 of POCA provides the magistrates’ court with a power to enforce a confiscation order. These sections amend the existing scheme provided in section 67 in three ways. Firstly, it is extended beyond police and HMRC officers to all law enforcement officers who have the power to seize money. Secondly, section 67 now applies to money that has been seized under any power relating to a criminal investigation or proceeding (not just the Police and Criminal Evidence Act), or under the investigatory powers in POCA. Thirdly, this section amends section 67 so that it applies to money however it is held by law enforcement, and not just in a bank or building society account.

76. Sections 28-30, miscellaneous Scottish provisions: this replicates the changes to section 67 as introduced for England and Wales and Northern Ireland and makes necessary amendments related to heritable property.

77. Sections 31-34, other miscellaneous: extends certain powers to accredited financial investigators in England Wales and Northern Ireland. Allows for reconsideration of confiscation orders, including those previously discharged, if new evidence becomes available and makes amendments to better enable an assessment of the property the defendant has at their disposal for seizure and confiscation. Extends the definition of ‘free property’ and makes other amendments pertaining to the disposal of property and discharge of existing confiscation orders.

Implementation

78. The implementation of these provisions has been completed and came into effect on 31st January 2018. There was a delay in the extension of the provisions of the Act to Northern Ireland as a result of the suspension between 2017-2020. The relevant provisions were commenced in Northern Ireland on 28th June 2021. This secured full alignment with asset recovery tools available in the other UK jurisdictions. The Act is now in force UK wide.

Secondary Legislation

79. The Secretary of State, under powers conferred by section 58 (1), (7) issued regulations giving effect to sections 26, 29 and 31-34 of this part of the Act. A significant volume of additional secondary legislation was also required to be issued by the Secretary of State and Minister of Justice for Northern Ireland to support the full commencement of the Act in Northern Ireland in 2021, this is set out below;

| Related regulations/guidance | Purpose | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Criminal Finances Act 2017 (Commencement No.4) No.78 | To give effect to sections 26, 29, 31-34 of this part of the Act. | Made: 20th January 2018 In effect: 31st January 2018 |

| The Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (Investigative Powers of Prosecutors: Code of Practice) Order 2021 No. 747 | Revised code of practice under POCA section 377(A) and (9). | Made 21st June 2021 In effect: 28th June 2021 |

| The Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (Recovery of Listed Assets: Code of Practice) Regulations 2021 No. 727 | Revised code of practice under POCA section 303G. | Made: 17th June 2021 In effect: 28th June 2021 |

| The Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (Search, Seizure and Detention of Property: Code of Practice) (Northern Ireland) Order 2021 No. 729 | Revised code of practice under POCA section 195S. | Made: 17th June 2021 In effect: 28th June 2021 |

| The Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (Cash Searches: Code of Practice) Order 2021 No. 728 | Revised code of practice under POCA sections 289 and 292. | Made: 17th June In effect: 28th June 2021 |

| The Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (Investigations: Code of Practice) Order 2021 No. 726 | Revised code of practice under POCA section 377. | Made: 17th June In effect: 28th June 2021 |

| The Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (References to Financial Investigators) (England and Wales and Northern Ireland) Order 2021 No. 640 | Amends organisations able to employ accredited financial investigators for the purposes of the Act. | Made: 25th May 2021 In effect: 28th June 2021 |

| The Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (Administrative Forfeiture Notices) (England and Wales and Northern Ireland) (Amendment) Regulations 2021 No. 639 | Extends forfeiture powers under POCA sections 303Z10(1) and 459(2) to Northern Ireland. | Made: 25th May 2021 In effect: 28th June 2021 |

| The Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (External Investigations and External Orders and Requests) (Amendment) Order 2021 No. 638 | Extends amendments pertaining to external investigations and requests to Northern Ireland. | Made: 26th May 2021 In effect: 28th June 2021 |

| The Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (Investigations in different parts of the United Kingdom) (Amendment) Order 2021 No. 637 | Enables the exercise of warrants issued under the Act across the country. | Made: 26th May 2021 In effect: 28th June 2021 |

| Criminal Finances Act 2017 (Commencement)(Scotland) Regulations 2017, No. 456 | To give effect to sections 28, 30, 32(4) and 34(3) of this part of the Act | Made: 19th December 2017 In effect: 31st January 2018 |

| The Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (Recovery of Listed Assets: Code of Practice) Order (Northern Ireland) 2021 No. 171 | Revised code of practice under POCA section 303 for the use of listed assets powers. | Made: 17th June 2021 In effect: 28th June 2021 |

| The Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (Investigations: Code of Practice) Order (Northern Ireland) 2021 No. 170 | Revised code of practice under POCA section 377ZA on investigatory powers. | Made: 17th June 2021 In effect: 28th June 2021 |

| The Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (Cash Searches: Code of Practice) Order (Northern Ireland) 2021 No. 169 | Revised code of practice under POCA section 293A regarding cash searches. | Made: 17th June 2021 In effect: 28th June 2021 |

| The Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (Search, Seizure and Detention of Property: Code of Practice) Order (Northern Ireland) 2021 No. 168 | Revised code of practice under POCA section 195T regarding searches and the seizure and detention of property. | Made: 17th June 2021 In effect: 28th June 2021 |

| The Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (Application of Police and Criminal Evidence (Northern Ireland) Order 1989) (Amendment) Order (Northern Ireland) 2021 No. 155 | Amends orders from 2016 and 1989 pertaining to warrants and investigations. | Made: 6th June 2021 In effect: 28th June 2021 |

Legal issues

80. In May 2021 a non-profit organisation based in New York raised a petition in the Scottish courts that, in essence, sought to establish that the Scottish Ministers had a legal duty under the Act to seek an unexplained wealth order against former US President Trump (and in other cases) and raised questions as to the role of the Scottish Ministers in applying for UWOs.

81. Lord Sandison rejected the petition, confirming in his ruling that the Lord Advocate (or other Scottish Ministers) could apply for a UWO, and that responsibility for that decision is held collectively. He also confirmed that UWOs are a discretionary tool and not mandatory in any context. The petitioner’s requests were thus denied in full.

Other reviews

82. Despite the delay in implementation of the Act in Northern Ireland there was significant cross-party political support for its implementation and frustration at the inability to do so in line with the rest of the UK. During the Northern Ireland Committee’s hearings and meetings as part of their inquiry entitled “The effect of paramilitary activity and organised crime on society in northern Ireland” the committee asked witnesses about the role of UWOs, they responded with general openness to the use of the power, with then Minister of Justice Naomi Long MLA commenting on their potential for use against criminal property and the £50,000 threshold.

Preliminary Assessment

83. Despite the delay in the provisions of the Act coming into force in Northern Ireland, the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) have been able to make active use of a number of the powers provided. This includes successful applications for listed asset orders, account freezing orders and forfeiture notices (although no disclosure order had been applied for as of September 2023). Counter terrorism forfeiture powers have also been used in a case whose related trial is ongoing and likely to be lengthy (the result of the forfeiture application will be dependent on the trial and appeal outcomes). Appropriate referrals have also been made to HMRC and the NCA under the Act. Barring the withdrawal of a premature application for an AFO against an electronic money institution (EMI) made before EMIs were subject to the Act (they now are) no substantive issues have been encountered, either with the powers in general or in a Northern Ireland specific context. The Act – once introduced – can therefore be said to have worked well and largely as expected in Northern Ireland.

84. Scottish law enforcement authorities have also had success in using the powers in the Act and have been able to proactively use them to seek the proceeds of crime. In keeping with the experience of the rest of the UK they note the value of AFOs, particularly in the context of combating money laundering and fraud (the latter of which constitutes the largest crime type in the UK). They have additionally made successful use of the listed asset powers.

Part 2 - terrorist property

Sections 35-43

Introduction

85. Countering terrorist financing remains a UK priority and is tackled through the UK’s Counter-Terrorism Strategy, CONTEST, by detecting, preventing, deterring, and disrupting the flow of terrorist finances. The UK has a robust legislative framework which criminalises the financing of terrorism in all its forms, and which continues to evolve alongside the more technological and complex threats that the UK and its interests may face. To that end the provisions in Part 2 of the Act contain amendments that pertain substantially to the Terrorism Act 2000 (TACT) and to a lesser extent the Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 (ATCSA); considerably extending powers under POCA to the counter terrorism space to allow the freezing and forfeiture of terrorist property, seizure of listed assets, expanding the definition of terrorist cash and enhancing the usability of powers that already existed in the two counter terrorism-related acts.

Provisions

86. Section 35, disclosure of information: enables the issuing of disclosure orders in relation to investigations into terrorist financing with appropriate protections and definitions.

87. Section 36, sharing information: this section allows the sharing of information between firms in the regulated sector where there is a suspicion of terrorist financing activity or where terrorist property has potentially been identified. A firm may also disclose this information, either at the request of a constable or an authorised officer of the NCA or with their permission.

88. Section 37, further information orders: allows for law enforcement to request further information from the regulated sector in an investigation relating to terrorist financing or identifying terrorist property.

89. Sections 38-40, civil recovery: extends forfeiture powers to other forms of terrorist cash, namely gaming vouchers, fixed value casino tokens and betting receipts. Also applies changes made to POCA regarding the forfeiture of personal or moveable property (listed assets) to ATCSA and allows the use of account freezing orders and asset forfeiture notices in the context of investigations into terrorist financing and potential terrorist property.

90. Sections 41-42, counter terrorism financial investigators (CTFI): introduces provisions for the creation of counter-terrorism financial investigators with the appropriate powers as set out in the Act, POCA, TACT and ATCSA as amended (including the offences of assaulting or wilfully obstructing a CTFI in the legitimate process of their work). Also mandates the Metropolitan police (as lead counter terrorism force) to set up an accreditation system which is available for use by other forces.

91. Section 43, cross border enforcement: amends TACT to enable relevant orders made in one part of the UK to be enforced in another part.

Implementation

92. The provisions in this section of the Act are in full effect as of 31st January 2018.

93. The mandated accreditation system has been established and is comprised of a unit which trains all counter terrorism financial intelligence officers (CTFIOs) and CTFIs. It conducts yearly assessments face to face with CTFIOs and CTFIs, and ensures continued learning input and training for them. Its training and systems are kept under continual review to account for new trends and learning forums and best practice from regional teams.

94. ECCT further amends provisions in POCA to enable law enforcement agencies to seize and detain cryptoassets and cryptoasset related items; to freeze cryptoassets held in crypto wallets administered by cryptoasset service providers and, ultimately, to forfeit cryptoassets. Those changes also apply to the investigation of terrorist property and terrorist financing amendments under TACT and ATCSA outlined in this section.

Secondary Legislation

95. The Secretary of State, under powers conferred by section 58(1), (7) and (8) issued regulations giving effect to provisions 35-38, 40 and 43. The Home Office also issued a code of practice in relation to the powers introduced in January 2018.

| Related legislation/guidance | Purpose | Date of issue |

|---|---|---|

| The Criminal Finances Act 2017 (Commencement No.2 and transitional provisions) No. 991 | To give effect to provisions of this and other parts of the Act | Made: 12th October 2017 In effect: 31st October 2017 |

| The Criminal Finances Act 2017 (Commencement No. 3) No. 1028 | To give effect to section 36 of this part of the Act. | Made: 25th October 2017 In effect: 31st October 2017 |

| Criminal Finances Act 2017 (Commencement No.4) No. 78 | To give effect to sections 35, 38, 39 and 40 of this part of the Act. | Made: 20th January 2018 In effect: 30th January 2018 31st January 2018 |

| Code of practice for officers acting under schedule 1 to the anti-terrorism, crime and security act 2001 | Code of Practice in relation to the exercise of powers conferred on officers by the Act | Made: 20th January 2018 In effect 31st January 2018 |

Legal issues

96. No substantive legal issues have been encountered with the use of the powers set out above.

Other reviews

97. In its December 2018 Mutual Evaluation Report the Financial Action Taskforce (FATF) found that the UK had a good level of cooperation between relevant powers, a strong suite of powers and a well-developed understanding of the threat picture for terrorist financing, noting the differing characteristics between cases in Northern Ireland and the rest of the United Kingdom. The FATF also noted the then new powers granted by the Act and UK law enforcement’s willingness to pursue alternative approaches where evidence of terrorist activity is lacking whilst not making any specific comment on the powers in the Act.

Preliminary Assessment

98. Despite the terrorist threat to the UK remaining ‘substantial’, law enforcement’s ability to investigate and prevent terrorist activity is already effective and highly matured and the new powers provided by the Act have further enhanced those capacities. Freezing and forfeiture powers have been used repeatedly in matters relating to terrorist activity and disrupting terrorist financing remains an important means of impeding terrorist operations.

99. However, challenges in this area remain given the diversity of the threat and the low level of resourcing required for lone actor or small-cell operations, the demands of which are often limited to general living expenses rather than the financing of complex operations. This makes it difficult to build up a comprehensive or predictive matrix of indicators, with a good deal of contemporary UK terrorist activity financeable through legitimate means such as salaries, wages or state benefits.

100. The picture in this space is diverse with dissident republican activity in Northern Ireland still significantly reliant on centralised financial structures in part funded by organised crime activities which are increasingly integrated into organisational structures in support of wider goals. Forfeiture powers under ACTSA provided by the Act have been used in a case in Northern Ireland which is currently ongoing and subject to appeal.

Part 3 - corporate offences of failure to prevent facilitation of tax evasion

Sections 44-52

Introduction

101. Part three of the Act created two new corporate offences. The first offence applies to relevant bodies, wherever located, in respect of the facilitation of UK tax evasion. The second offence applies to relevant bodies with a UK connection in respect of the facilitation of foreign tax evasion. These provisions were modelled after the failure to prevent bribery offence introduced by the Bribery Act 2010 which was widely welcomed and commended upon its introduction. The intention of creating a criminal failure to prevent offence was to overcome the difficulties in attributing criminal liability to corporates for the criminal facilitation of tax evasion committed by their representatives, either in the UK or overseas. Both are strict liability offences, subject to a ‘reasonable procedures’ defence available to those who can prove that they have maintained reasonable procedures intended to prevent the facilitation of the underlying tax evasion offences. The offences aim to drive a change in corporate culture, rather than to drive convictions and to encourage good corporate governance and strong reporting and preventative procedures. The legislation thereby aims to help reduce tax evasion.

Provisions

102. Section 44, defining relevant body: defines a relevant body as a corporate body or partnership and when a person’s activities can be considered to be acting in the capacity of a person associated with the relevant body.

103. Sections 45-46 failure to prevent facilitation: sections 45 and 46 create the offences of failure to prevent facilitation of UK and foreign tax evasion. The offences are committed where a relevant body fails to prevent an associated person criminally facilitating the evasion of a tax. This will apply whether the tax evaded is owed in the UK or in a foreign country. Where the relevant body has put in place ‘reasonable prevention procedures’ to prevent its associated persons from committing tax evasion facilitation offences, or where it is unreasonable to expect such procedures, it shall have a defence.

104. Section 47, guidance about prevention procedures: requirement for the Chancellor to publish appropriate guidance on preventative measures.

105. Sections 48-50 offences: establishes extraterritoriality of the law (in line with the Bribery Act 2010), permission levels with prosecuting agencies and applicability to partnerships.

106. Sections 51-52 consequential amendments and interpretation: amends various Acts to enable use of powers contained within them (for example, deferred prosecution agreements) to cases featuring the new offences.

Implementation

107. The new offences came into force on 30th September 2017 and are applicable to organisations that failed to prevent the facilitation of tax evasion from that date. As of 30th June 2023, HMRC had nine potential corporate criminal offences investigations underway and a further 25 live opportunities under review. However, thus far there have been no convictions under the new offences with 83 cases having been reviewed and rejected. It should be noted that the offences are not retrospective and investigations of this nature are complicated and lengthy and must cover the three stages of the offence. By comparison, the first conviction under the Bribery Act 2010 took place six years after its introduction. Whilst this is not a direct equivalent it does indicate the potential length of time for a first conviction.

108. HMRC has worked to significantly raise awareness of the offences across industry in the UK and overseas by hosting or attending over 100 industry events in more than 10 jurisdictions since June 2016. This includes events with legal and accounting bodies Tax Advisor magazine and the Tax Professionals podcast.

109. The Covid-19 pandemic led to an intervention pause which resulted in a significant decline in referrals identifying facilitation of tax evasion. However, over the course of 2022 there was a marked increase in the number and quality of referrals received. This is reflected within the number of live and opportunity cases reported.

Secondary Legislation

110. HMRC has issued guidance (first published 6th September 2017, see table below) on the new offences, including information on procedures relevant bodies can introduce in order to minimise the risk of representatives facilitating tax evasion.

111. HMT, using the powers conferred by section 58(5) and (7) of the Act made regulations bringing section 47 of the Act into effect on 17th July 2017 and the remaining provision in part 3 into effect on 30th September 2017.

112. The legislation also allows the Chancellor to approve guidance created by other parties if it is in keeping with the government guidance. This power has been used to allow representative bodies to produce sector-specific guidance. The Chancellor has approved guidance from UK Finance to the financial services sector in January 2018 and guidance from the Law Society for the legal services sector in November 2018, see table below.

| Related regulation/guidance | Purpose | Date of issue |

|---|---|---|

| The Criminal Finances Act 2017 (Commencement No.1) No.739 | To give effect to the provisions of part three of the Act. | Made: 12th July 2017 Into force: 17th July 2017 and 30th September 2017 |

| Failing to prevent criminal facilitation of tax evasion – government guidance on the criminal offences | Guidance on the offences, including appropriate processes and procedures to limit risk. | 6th September 2017 |

| Guidance for the financial services sector on the corporate criminal offences within the Criminal Finances Act 2017 | Guidance regarding the failure to prevent facilitation of tax evasion offences. | Issued: 8th January 2018 |

| Criminal Finances Act 2017 practice note | Practice note to provide guidance to solicitors on the corporate offences of failure to prevent the criminal facilitation of tax evasion | Issued: 21st November 2018 |

Legal issues

113. A significant challenge for HMRC has been evidencing that an individual suspected of facilitating tax evasion was knowingly involved in the fraudulent evasion of tax by another person. Increased awareness and training of this and ‘failure to prevent facilitation of UK tax offences’ and ‘failure to prevent facilitation of foreign tax evasion’ has resulted in an increase in referrals. No other substantive legal obstacles have been encountered.

Other reviews

114. RUSI has published ‘Corporate criminal liability: lessons from the introduction of failure to prevent offences which considers the use of failure to prevent offences in the context of addressing weaknesses in the legal framework surrounding corporate criminal liability. It examined the roll-out and perceptions of the offenses in this Act and criticises the lack of a successful prosecution, which, it argues, has undermined business engagement with the offence. They also note that there is some evidence from their research of behavioural change as a result of the Act with HMRC reporting positive engagement from industry on the introduction of the offence.

Preliminary Assessment

115. Whilst there have not yet been any successful convictions under the failure to prevent offences this should not be considered the only metric of success. The offences were introduced with the intention of encouraging behavioural change within corporates in order to reduce the risk of facilitation of tax evasion taking place in the first instance.

116. A review of corporate accounts and annual returns has identified significant reference to the Act, corporate criminal liability and the failure to prevent offences. This is not a mandatory requirement for companies and could indicate that the legislation is driving changes in corporate compliance structures in relation to the legislation. Further work is ongoing, and no preliminary findings or conclusions have yet been made. Additionally, RUSI noted in the report above that large financial institutions and insurers had paid particular attention to the legislation with many having actively engaged with HMRC in order to better understand the requirements under the Act. It is reasonable to assume that this engagement was undertaken with the objective of ensuring company compliance and informed any required changes.

117. Research carried out by IPSOS MORI on behalf of HMRC indicated that large companies in particular were aware of and planned to act on the new offences (although challenges in reaching and updating smaller firms remain).

118. As noted above, HMRC is also working to build understanding and awareness of the offence both within companies and within investigative teams, with the later intended to increase the number of potentially actionable cases developed and put forward for prosecution decisions. In the event that this is successful we would expect that further awareness of the offences and change in corporate behaviour would take place.

Part 4 - General

Sections 53-59

Introduction

119. Sections 53-59 are largely technical provisions. Amongst other things they concern financial matters, territorial extent, procedural requirements and provisions to enable the Secretary of State, Scottish Ministers and Department of Justice of Northern Ireland to make provision consequential on the Act.

Provisions

120. Section 53, minor and consequential amendments: gives effect to Schedule 5, which contains minor and consequential amendments to other enactments.

121. Section 54, power to make consequential provisions: enables consequential amendments of the Act by regulations by the Secretary of State, Scottish Ministers and Department of Justice of Northern Ireland.

122. Section 55, procedural requirements: requires the Secretary of State to consult with the devolved administrations as appropriate when making amendments which apply to devolved competencies.

123. Section 56, financial provisions: sets out financial provisions relating to the Act.

124. Section 57, extent: sets out the territorial extent of the provisions in the Act.

125. Section 58, commencement: provides for commencement and empowers the Secretary of State, Scottish Minister, Department of Justice of Northern Ireland (in consultation with the Secretary of State) and The Treasury to make amendments by regulations as necessary for the implementation of the Act.

Implementation

126. The provisions used in this section and their use are set out under the secondary legislation and implementation headings of the relevant parts of the report. Various minor and amendments were also made under section 53 detailed below.

| Related legislation/guidance | Purpose | Date of issue |

|---|---|---|

| The Criminal Finances Act 2017 (Commencement No.2 and transitional provisions) No.991 | To give effect to provisions of this and other parts of the Act. | Made: 12th October 2017 In effect: 31st October 2017 |

| Criminal Finances Act 2017 (Commencement No.4) No. 78 | To give effect to section 53 of this part of the Act. | Made: 20th January 2018 In effect: 30th January 2018 31st January 2018 16th April 2018 |

Conclusion

127. The powers introduced by the Act have been broadly welcomed by operational agencies and have meaningfully contributed to their ability to combat money laundering and pursue the freezing and seizure of criminal assets, including those intended for or related to terrorist activity. Account freezing orders and asset forfeiture notices have been particularly well received and have been used extensively, helping to drive a significant step change in rates of civil recovery of criminal assets.

128. Whilst the failure to prevent offences created in the Act have not yet resulted in a trial or conviction there is evidence that they are driving behavioural change amongst companies – particularly the larger corporates with greater capacity. Additionally, we would expect prosecutorial activity related to these offences to increase over time (noting the amount of time taken to reach the first failure to prevent based prosecution following passage of the Bribery Act).

129. With regards to UWOs, where challenges to use and implementation have arguably been most pronounced, the government has moved to significantly strengthen the legal framework through the ECTE and we await to see the outcome of those improvements. It is intended that through reducing the risk of costs exposure and broadening the contexts in which the power can be used there will be an increase in their use. Their use ultimately remains an operational decision for law enforcement depending on the context of any given operation and UWOs are only one tool among many that can be used to tackle illicit finance.

130. The Act has now been fully implemented and is in place throughout the United Kingdom, with the differing timetables for implementation reflected in operational activity. Whilst the powers in the Act represented a significant improvement in the powers available to law enforcement their efficacy has been further improved by the measures contained within the ECTE and ECCT. Those measures include the strengthening of UWOs, additional help for law enforcement in tracking and identifying the proceeds of crime and allowing for more effective seizure of both criminal and terrorist cryptoassets.