Guidance: Mixed Procurement (HTML)

Updated 5 November 2025

What is mixed procurement?

1. Contracting authorities need to be able to award contracts that are not always 100% goods, 100% services or 100% works. Contracts can therefore comprise a mixture of two or more different categories. Contracting authorities may also need to award contracts of either one type (such as a concession contract, or a light-touch contract), or of a mixture of different types (for example a concession contract for services that are for military purposes).

2. Contracts involving different categories or types will become public contracts above different value threshold levels. Contracts of different types (such as concessions, light touch contracts, defence and security, and utilities contracts - which are categorised as ‘special regime’ contracts) are also subject to different applications of the rules in the Procurement Act 2023 (Act).

3. It is therefore important that contracting authorities know how to designate any contracts they wish to award that might comprise a mixture of different categories or types.

What is the legal framework that governs mixed procurement?

4. Section 5 of the Act sets out the rules on determining when a mixed contract will become a public contract. This is because a mixed contract may comprise two or more elements that, if procured separately, would have different applicable thresholds (over which they will be designated as a public contract). Section 5 provides clarity on applying the rules on thresholds to situations where a contract contains mixed elements, where at least one is above and one is below the relevant thresholds. Consequently authorities have the necessary flexibility to procure mixed contracts where appropriate but are prevented from exploiting that mixture to avoid the application of the more detailed rules in the Act.

5. These provisions must be understood in conjunction with Schedule 1, paragraph 4, which sets out that a contract the main purpose of which is works will be deemed a works contract.

6. Section 10 of the Act sets out how the rules in the Act will apply to contracts of more than one type, where at least one of which is a ‘special regime’ contract (defined as concession contracts, light touch contracts, defence and security contracts, and utilities contracts). It regulates circumstances where contracting authorities mix special regime contracts that benefit from certain flexibilities (such as higher thresholds or lighter process obligations) with either other contracts that should be subject to the general rules (which would not normally involve such flexibilities) or other special regime contracts. It provides a clear set of rules that contracting authorities can follow when determining whether to mix or split out contracts which include at least one element covered by a special rules regime. This means that authorities have the necessary flexibility to mix contracts involving special regime elements where appropriate, but are prevented from exploiting that flexibility (and taking advantage of the lighter rules of a particular special regime) where it is reasonable to split out a mixed contract. The position is different in relation to mixed contracts involving defence and security where there is more latitude not to split out the different elements (see paragraph 23).

What has changed?

7. As is the case with certain other basic definitions and concepts, the policy on mixed procurement has not been substantively reformed. However, the opportunity has been taken to significantly streamline these rules while preserving a similar intention and effect to the former rules on mixed procurement in the previous legislation.

8. However, there are some inevitable differences in the way these rules are set out in the Act. For example, the previous legislation on mixed contracts involved navigating the interplay between combinations of procurements involving multiple regulatory schemes. In contrast, the Act addresses mixed procurement within a single scheme. There is therefore no longer a need for authorities to run a series of tests to determine which regulatory scheme will apply to their procurement. The ‘subject-matter test’ of the previous legislation has been replaced by a ‘main purpose’ test to reflect this change although both have a similar effect.

Key points and policy intent

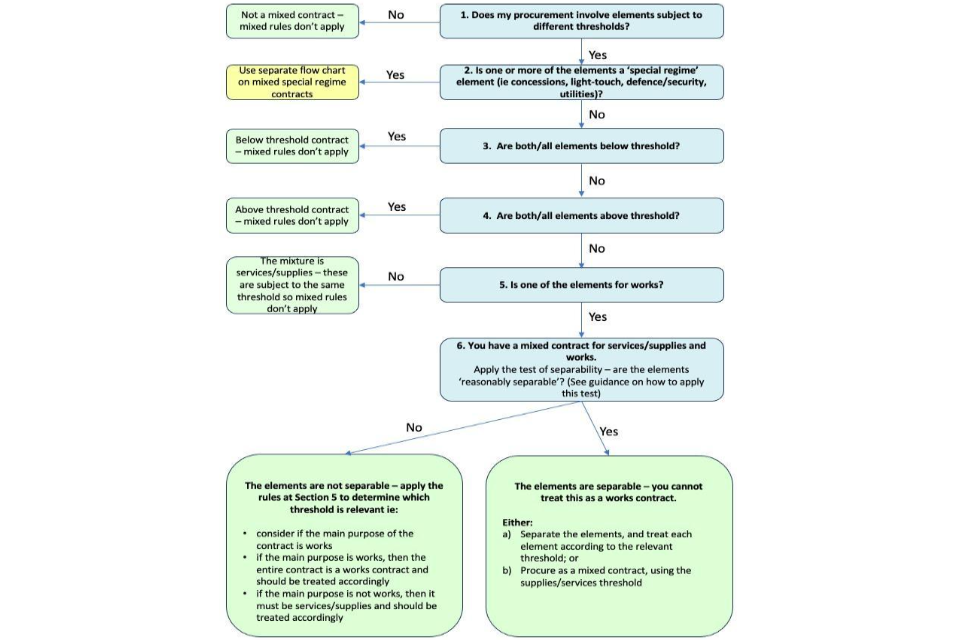

9. Thresholds determine whether or not a contract is a public contract; the procurement of which is regulated by the Act. Different thresholds apply to goods, works or services contracts. These are set out in Schedule 1. Where a contract contains a mixture of these elements (a mixed contract), contracting authorities will need to determine which threshold to apply and whether a mixed contract should have those elements separated into different contracts. If the contract is separated out, thresholds can be calculated separately for each separate contract (each of which will only fall within one such type).

10. Section 5 sets out the test to be applied to ensure that authorities do not mix above and below threshold elements purely for the purposes of avoiding the rules. This is important because, without any rules on mixed procurement, the different thresholds could provide a loophole to rule-avoidance. For example, a goods contract for £200k (i.e. above-threshold) must be awarded in accordance with the full rules, but the loophole would allow the possibility of adding in an unrelated element of works (say £1m, below the works threshold), and then advertising the whole package as a below-threshold works contract thereby avoiding the proper procurement rules for the goods element. The mixed contracts rules close this loophole whilst providing the necessary flexibility for contracting authorities to mix contracts where appropriate. There are two thresholds relevant in this context: the goods/services threshold, and the works threshold. Contracts involving a mixture of elements involving the ‘special regime’ thresholds are dealt with separately in section 10.

11. If a mixed contract can reasonably be separated out, but a contracting authority chooses not to do so, the mixed contract will, where one element is above its corresponding threshold, be treated as above-threshold (and therefore, unless an exemption applies, a public contract to which the Act applies). This is provided for in section 5(3), which requires mixed contracts to be treated as above-threshold where the conditions in section 5(1) are met.

12. Section 5(2) provides that a similar test applies when the contract awarded is a below-threshold framework that provides for the procurement of a mixed contract under it. If a mixed contract to be awarded under the framework contains above and below-threshold elements that could reasonably be separated out, and the above-threshold element can be awarded outside of the below-threshold framework, but a contracting authority chooses not to separate, the framework must be treated as an above-threshold contract (and therefore, unless an exemption applies, a public contract to which the Act applies). In addition, section 45 will apply to all mixed contracts awarded under that framework where an element of the mixed contract is above-threshold. This is regardless of whether the contract could reasonably be separated and section 5(6) provides that the test is not reapplied when contracts are awarded under the framework.

13. There are a number of factors contracting authorities may consider when determining whether elements of a mixed contract can reasonably be procured separately. These may include (but are not limited to) the practical and financial consequences of splitting out the requirement.

14. Contracting authorities need flexibility given the wide range of public procurement: separate elements can always be procured separately, and mixed contracts whose elements are inseparable are permitted by the Act. Indeed, many contracts will contain elements of different categories. But the basic safeguard remains that if separation is reasonably possible, but a contracting authority chooses not to separate, a mixed contract containing both above and below threshold elements must be treated as above-threshold and therefore in-scope of the legislation. When determining whether or not separation is reasonably possible, factors such as the practical and financial consequences of awarding more than one contract can be taken into consideration. The Act does not specify or give examples of these matters; this is at the discretion of the contracting authority, as such considerations will vary from one procurement to another. Conceivably such considerations might involve, for example, the extra resources required to run multiple procurements rather than one aggregated procurement, or the potential for increased value for money or potential SME-access benefits from separating the procurements, but the Act does not set any particular boundaries or limits on contracting authorities’ discretion here.

15. Looking at the potential combinations of contracts that will be caught by the provisions in section 5, clearly if both/all elements are below-threshold then the whole contract will be below-threshold, whereas if all elements are above-threshold then the whole contract will be above-threshold. The rules on mixed procurement in section 5 are only therefore relevant in situations where an element for goods/services is combined with an element for works, and only one element is above-threshold. In such a situation, the contracting authority can either split the elements out and procure them separately, or combine the elements into a mixed contract and follow the rules set out in section 5 to determine which threshold applies.

16. Having decided to pursue a mixed procurement approach, the contracting authority must then apply the test of ‘reasonable separability’.

17. For example, if the elements of the contract are not reasonably separable (e.g. because procuring them separately would compromise value for money) then the contracting authority would need to consider whether the main purpose of the contract is works. Schedule 1, paragraph 4 is relevant here, as it sets out that a contract the main purpose of which is works will be a works contract. If the main purpose is indeed works, then it is a works contract and will be treated according to the value of the works element. And if the main purpose is not works, then it is clear that the goods/services threshold is the relevant one.

18. If, however, the works and goods or services elements are reasonably separable, the whole mixed contract must be treated as above-threshold. This prevents authorities from mixing entirely unrelated contracts for the purposes of avoiding the rules.

19. Schedule 2, paragraph 1 provides that a contract is only an exempt contract where the goods, services or works that form its main purpose are exempt. An element of exempt services in a mixed contract will not, for example, mean the entire contract is exempt if that element does not comprise the main purpose of the contract.

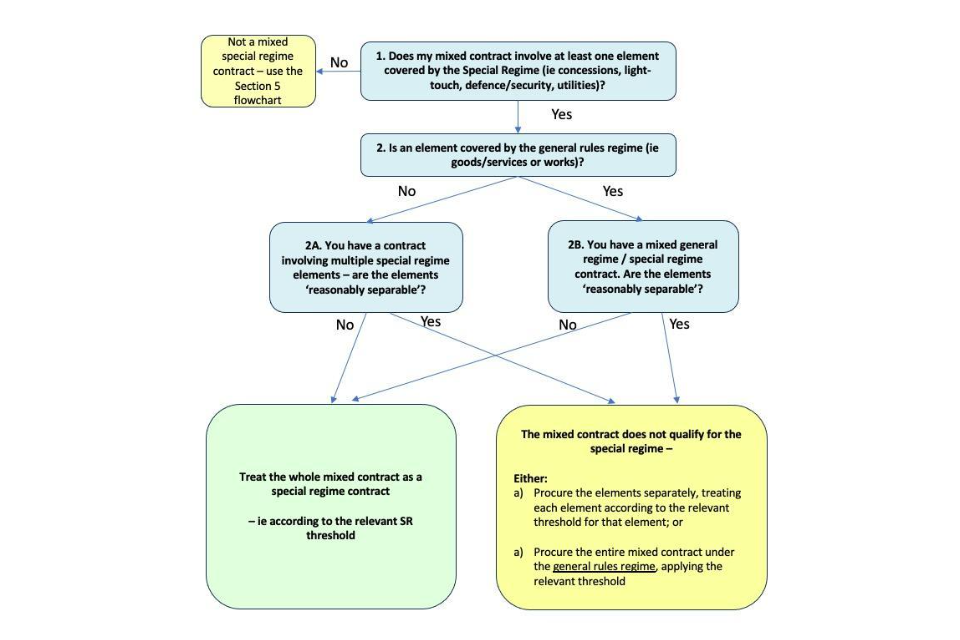

20. Section 10, which should be considered alongside the closely related section 5, addresses mixed contracts that involve (at least) one element to be procured under the ‘special rules regime’. As ‘special regime’ contracts normally involve lighter touch rules and higher thresholds, it is necessary to consider how they can be mixed with contracts subject to the general rules regime. Similarly, not all special regimes have the same thresholds or application of lighter touch rules, so a decision needs to be made as to which special regime will apply where more than one special regime could be applied to the mixed contract.

21. In a similar vein to section 5, it is important to recognise and provide for the inevitable possibility that the need for such mixed contracts will arise, whilst safeguarding against possible exploitation of exemptions and the lighter touch rules in situations where the full rules regime would be more appropriate. This is achieved in a similar way to the safeguard at section 5, through introducing a test of separability.

22. When placing a mixed contract containing one or more elements that would, if procured separately, be subject to ‘special regime’ provisions in the Act, together with other above-threshold elements that would not be subject to that special regime, section 10(3) provides that a contracting authority cannot take advantage of such special regime rules where it would be reasonable to split out the requirement. This rule applies whether or not the contract being placed is one directly for works/goods/services or whether it is for a framework under which contracts will be let for works/goods/services (see section 10(2) for application to frameworks).

23. In addition, Schedule 2, paragraph 1 provides that a contract is only an exempt contract where the goods, services or works that form its main purpose are exempt. An element of exempt services in a mixed contract will not, for example, mean the entire contract is exempt if that element does not comprise the main purpose of the contract.

24. There is an exception for mixed special regime contracts that are defence and security contracts in recognition of the sensitivities of defence procurement. These can be treated as a special regime contract even where the conditions in sections 10(1) or 10(2) apply, if there are good reasons for procuring the elements together.

25. If separation of the general rules regime and special rules regime elements is possible, but a contracting authority chooses not to separate out the contract, then that mixed contract must be awarded in accordance with the general rules – it will not qualify for the special rules regime if the elements could reasonably be procured separately. When determining whether elements of a mixed contract can reasonably be procured separately or not, a contracting authority can consider factors such as the practical and financial consequences of awarding more than one contract.

26. Whether or not the mixed contract can be treated as a special regime contract, the contract is still to be treated as a public contract subject to the Act.

27. As with section 5, contracting authorities should not run the analysis again for contracts awarded under a framework; the test would have been applied prior to the procurement for the framework by considering the goods, services or works to be supplied under potential call-off agreements to be awarded under the framework (see section 10(2)).

28. Section 10 also acknowledges and provides for the possibility where a mixed contract involves two or more different ‘special regime’ elements. Although these cases may be rare, a test of reasonable separability will also be used to guide decisions on which rules to apply. The main purpose special regime will only apply where the two elements cannot be reasonably separated. If the elements can be reasonably separated but are not, the mixed procurement will be subject to the normal rules regime, not the special rules regime. In this situation the contracting authority would have the choice as to procure two separate special regime contracts (and enjoy the flexibility of the correct respective regime in each procurement), or pursue a mixed contract under the full rules regime.

29. As noted earlier this position is qualified in relation to mixed special regime contracts involving defence and security. Such contracts can still be treated as a special regime contract even where the elements can reasonably be separated, where there are good reasons for not awarding separate contracts in recognition of the sensitivities of defence procurement. This qualification grants more discretion to contracting authorities awarding defence and security contracts where there is no need to consider whether or not the elements could reasonably be split out, only to have a good reason for procuring the elements together.

What other guidance is of particular relevance to this topic area?

Guidance on thresholds

Guidance on valuation of contracts

Guidance on the special regimes (concessions, utilities, light touch, defence and security)

Related questions

MIXED CONTRACTS INVOLVING AN ELEMENT COVERED BY THE PSR

What is the ‘Provider Selection Regime’?

The Provider Selection Regime (PSR) is a new set of bespoke procurement regulations which commissioners of healthcare services in the NHS and Local Government will follow when procuring or otherwise arranging certain healthcare services in their area. This intends to address the idiosyncrasies of the health and care system and fulfil the Health and Care Act’s intention to deliver greater collaboration and integration in the arrangement of healthcare services. The PSR regulations came into force on 1 January 2024; further information is available at: NHS Provider selection regime

How does the PSR interact with the reforms in the Procurement Act?

The PSR covers only the procurement of healthcare services which are delivered to patients and service users – and only when they are arranged by relevant healthcare authorities including NHS bodies and local authorities. The PSR has a very tightly defined scope of services and bodies caught, the details of which are set out in the PSR regulations.

The Procurement Act will be disapplied to procurements in scope of the PSR, using the relevant regulation-making power at section 120. The Procurement Act will cover all other goods, services, and works purchased by contracting authorities including such procurement by NHS bodies and Local Authorities.

How will mixed contracts involving healthcare and other goods/services be different when the Procurement Act comes into force?

The Procurement Act will apply to mixed contracts that involve a healthcare and non-healthcare element if those elements could reasonably be supplied under separate contracts, and if they could not be supplied under separate contracts, then the applicable scheme would be determined according to the highest value element.

Annex A - Mixed Procurement - Above and Below Threshold (Section 5)

Annex B - Mixed Procurement - Special Regime (Section 10)