Product safety: checks and balances on developing policy and legislation

Updated 22 July 2025

Updated version

Published in support of the Product Regulation and Metrology Act 2025.

Purpose of this document

This Code of Conduct is designed to serve those developing product safety policy and legislation by giving them an overview of:

a) the different aspects of the UK safety landscape

b) the place of UK consumers at the heart of UK product safety policy, with its key objective of protecting them from unsafe products

c) the collaborative processes by which we develop UK product safety policy, and the stakeholders involved

The Code of Conduct sets out the:

a) the existing legislative and non-legislative ‘guardrails’ around the UK product safety framework which includes requirements to place only safe and compliant products on the market and enable where necessary the removal of unsafe products

b) how the Government intends to use the powers in the Product Regulation and Metrology Act 2025, building on current methodology from policy to delivery, to ensure product safety measures are proportionate and effective

Key documents for policy makers are signposted along the way.

Individuals and businesses, whether micro, small, medium sized or large, should read more detailed guidance about how to comply with existing product safety legislation.

Read general product safety guidance for businesses.

Introduction

1) People have the right to expect that the products they buy and use (including in the workplace) are safe. Over the years, a product safety regulatory system has developed in the UK to ensure this is the case. Regularly updated as risks and technologies evolve, it covers most consumer products and many industrial items. The placing of safe products on the marketplace gives confidence to consumers and enables responsible businesses to grow and innovate. This is true across the United Kingdom and preserved through the application of a strong regulatory system.

2) Much of the current legislative base was developed and harmonised whilst the UK was a member of the European Union (EU). The regulatory system is therefore founded on a firm statutory base, supported by a number of administrative tools, not requiring legislation for their use. Powers to further amend and develop the legislative base have been severely curtailed since the repeal of the European Communities Act 1972, and the UK now needs to decide when and how to update our regulatory system to keep people and places safe from product related harm.

3) In July 2025, Royal Assent was given to the Product Regulation and Metrology Act. [footnote 1] The Act provides powers to amend product safety regulations, ensuring the UK continues to be a global leader in these areas, supporting businesses and protecting consumers. The powers in the Act, amongst other things, enable the UK to address current and future challenges: modern safety issues, the move towards net zero, the use of artificial intelligence and other technological developments.

4) As well as responding to new product risks and opportunities, the powers will also allow the UK to identify new and emerging business models in the supply chain, ensuring the responsibilities of all actors, such as online marketplaces, are clear. This will enable the Government to protect consumers better, so they can have confidence in the products they buy and in those from whom they buy them.

5) A successful regulatory system needs an effective compliance and enforcement regime. Powers in the Act will enable improvements to this regime, reflecting the challenges of modern, digital borders. These powers will enable the Government and its regulators to tackle non-compliance and target interventions by allowing greater sharing of data between relevant authorities.

6) The enabling powers set out in the Act are broad by necessity to ensure that the regulatory system can adapt quickly to pressing threats and technological advances. In updating and improving the regulatory system, the Government is considering a range of issues to ensure any intervention is proportionate, targeted and effective, regulating only when necessary. Likewise, regulatory action will be risk-based and proportionate to the potential harm. Striking the right balance is essential in protecting consumers, supporting responsible businesses and driving growth across the economy by creating a fair playing field and confidence and certainty in the regulatory approach.

7) To ensure this is achieved, guardrails are in place to guide policy makers and compliance teams. This document summarises those guardrails [footnote 2] in a single place showing the methodology adopted from policy through to delivery – ensuring the product safety regulatory system remains proportionate and effective.

The regulatory system

8) The UK’s product safety regulatory system combines legislation, technical standards, regulatory oversight, and guidance to ensure users are protected from products which, if unsafe or non-compliant, could cause them harm. A joint approach, with responsibilities for industry and government, has built up over decades. As well as primary legislation, the UK has dozens of statutory instruments that cover product safety and thousands of standards published by the British Standards Institution.

9) The regulatory system places obligations on the key economic operators in the supply chain – manufacturers, importers and distributors – to ensure that only safe products are placed on the market, supported by independent third-party test houses where required. It provides for ongoing responsibilities for sampling, testing and taking action where risks emerge. It also provides for ongoing market surveillance and enforcement by statutory authorities to ensure economic operators are fulfilling their obligations.

10) When designed and implemented well, regulation can provide a mechanism to address public safety, economic, societal and environmental risks and deliver positive outcomes. The Government Action Plan for regulators and regulation, launched in March, outlines a well-designed and coherent regulatory system that covers both regulations and the regulators that implement and enforce them.

The general safety requirement

11) Where not governed by more specific safety requirements, consumer products are subject to the general safety requirement. This makes clear that consumer products must be safe when sold or supplied on the UK market.

12) The General Product Safety Regulations 2005 (GPSR) provide the basis for ensuring the safety of consumer goods and apply to products intended for, or likely, under reasonably foreseeable conditions, to be used by consumers. This includes products supplied or made available to consumers for their own use in the course of a service – for example, gym equipment for use in a gym, highchairs provided for use by diners in a restaurant and trolleys for use by shoppers.

13) The GPSR place other obligations on producers (which includes UK manufacturers and importers) and distributors relating to the placing on the market of safe products, including: traceability of products, provision of information to users for assessment of risk of the product, documenting complaints and emerging risks, sample testing for safety, notifying enforcement authorities of emerging risks, and cooperating with those authorities.

High risk sectors

14) While the GPSR are clear that all consumer products within scope must be safe, there are a number of sectors (e.g. toys; pyrotechnics; lifts [footnote 3]) where additional, more specific, essential safety requirements are set out in detail to mitigate particular hazards, or a potential user vulnerability. These sector-specific regulations can place more detailed duties on those in the supply chain, prescribe, restrict or prohibit certain actions or chemicals, and/or set out specific testing, labelling or marking requirements.

15) Most existing sector-specific regulation is derived from the EU, either transposed directives or directly applicable Regulations, and has been retained in UK law as part of EU exit. However, some sector-specific regulations are UK driven, for instance, furniture fire safety. Guidance is provided for most of these sectors to support businesses to comply on GOV.UK.

Read sector-specific product safety guidance for businesses.

16) The particular duties that apply to sector-specific regulations reflect the potential risks associated with those types of product. This can include regulation of the raw materials used to manufacture the genre of product, qualifications needed to undertake production processes, and conformity assessment requirements all the way through to putting products into service, installation, adaptation, and disposal.

The National Quality Infrastructure

17) Legislation is not the only element of the product safety regulatory system. Trading relationships are built on an important structure of standards, agreements and codes, as well as regulations, designed to ensure that when businesses and consumers buy a product, they get exactly what they expect. For these standards, agreements and codes to be effective in delivering expectations, they need to be written and adhered to consistently in ways that give everyone involved a high level of confidence in the outcome.

18) It is the role of the National Quality Infrastructure (NQI) to enable this consistent rigour. The NQI has five core components:

- Standardisation – creates the national and international standards that describe good practice in how things are made and done.

- Accreditation – ensures that those who carry out technical conformity assessment, testing, certification and inspection are competent to do so.

- Measurement – implements specifications and standards to ensure accuracy, validity and consistency.

- Conformity assessment – entails testing and certification to ensure the quality, performance, reliability or safety of products meet specifications and standards before they enter the market.

- Market surveillance – checks whether products meet the applicable legal safety requirements. If they do not, market surveillance and enforcement authorities have the powers to ensure compliance, or, where necessary, to take steps to remove or recall products from the market.

19) The UK’s NQI is largely delivered by four internationally respected institutions:

- BSI – The British Standards Institution is the UK’s National Standards Body responsible for producing British Standards and coordinating the input of UK experts in the international and European standards organisations.

- UKAS – The United Kingdom Accreditation Service is the UK’s National Accreditation Body. UKAS accreditation assures the competence, impartiality and integrity of testing, calibration, inspection and certification bodies.

- NPL – The National Physical Laboratory is the UK’s National Metrology Institute responsible for maintaining the UK’s primary measurement standards that ensure the accuracy and consistency of measurement.

- OPSS – The Office for Product Safety and Standards (part of the Department for Business and Trade) provides the regulatory and market surveillance infrastructure enabling businesses to place products on the UK market. OPSS is supported where appropriate by sector-specific authorities such as Ofcom for radio equipment.

Standards

20) Standards are developed by standardisation bodies by bringing together a wide range of stakeholders through a process based on the principles of consensus, openness and transparency. They are the distilled wisdom of people with expertise in their subject matter and form a body of knowledge of good practices, codes, guidance and specifications addressing products and services, business processes and principles.

21) The international and European standards organisations promote the adoption of consensus standards and the withdrawal of conflicting local standards as a fundamental basis for simplifying the conditions of market access across the world, reducing technical barriers to trade, and underpinning the rules-based system of international trade. International standards are considered a ‘passport to trade’.

22) Within the international standards-making system, the UK through BSI holds a strong position of leadership in the development of international standards that support the national interest and become adopted globally. The Government’s policy of influencing international standards in coordination with BSI is reflected in the document titled ‘The UK Government Public Policy Interest in Standardisation’.

Read UK Government Public Policy Interest in Standardisation.

23) The high-level document underlines how key policy ambitions can be supported by UK global leadership in developing and promoting the use of international standards.

Standards and regulation

24) Both the EU and the UK use a co-regulatory approach for product legislation. This approach involves the legislator setting top-level essential requirements, and allowing stakeholders to determine how these requirements should be met in terms of technical solutions. In the EU, the European standards organisations develop ‘harmonised standards’ to support and often provide presumption of conformity to EU product legislation. In domestic product legislation, certain standards are designated by the Secretary of State so that they can be used to give rise to a presumption of conformity with requirements in product regulations.

25) A designated standard is a standard recognised by government in part or in full by publishing its reference on GOV.UK in a formal notice of publication. Depending on the product, a designated standard can be a standard adopted by any of the recognised standardisation bodies. These include:

- The British Standards Institution (BSI)

- The European Committee for Standardisation (CEN)

- The European Committee for Electrotechnical Standardisation (CENELEC)

- The European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI)

- The International Organization for Standardization (ISO)

- The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC)

- The International Telecommunication Union (ITU)

26) Manufacturers and other economic operators must ensure products comply with essential requirements. By following designated standards, there is a (rebuttable) presumption that the product is in conformity with the essential requirements covered by that standard. Standards can also support economic operators to create and market effective products for all users. For example, BSI has produced a standard on inclusive design that seeks to support businesses to encompass an inclusive approach to product design. This is critical for overall product safety by helping producers ensure their products take account of the needs, capabilities, and preferences of all potential users.

27) The use of designated standards is mainly voluntary, and manufacturers can choose other technical solutions to demonstrate regulatory compliance such as non-designated national standards, international standards, or manufacturers’ own technical specifications. Following designated standards can help reduce financial and administrative burden by allowing manufacturers to undertake simplified conformity assessment procedures that do not require a third party to assess the product.

28) In the case of product safety, BSI updates OPSS on new or revised standards that can be considered for designation. The government assesses whether the standards put forward are suitable for the purpose of providing a presumption of conformity to relevant essential requirements. This information is shared by OPSS with the relevant government departments and agencies responsible for designation decisions.

29) When deciding if a standard is appropriate for designation, the responsible government department or agency will assess how far it covers the essential requirements set out in the relevant legislation. This assessment compares the provisions of the standard with the requirements of the regulation. It does not assess the quality of the standard nor its technical adequacy, which is the responsibility of BSI.

30) Government may decide to designate a standard in full, not to designate, or, to designate with restriction. Any such restrictions will be published on GOV.UK. It is important that stakeholders look at published notices for references that may be subject to restrictions in respect of essential requirements in law. The specific parts of a standard covered by a restriction would not give presumption of conformity with the specified essential requirements. Where a standard that is designated replaces an existing designated standard, there is a transition period during which both the new designated standard and the superseded standard give a presumption of conformity.

31) Only the application of a designated standard will give a presumption of conformity to the relevant essential requirements. There may be instances where the reference to a designated standard is accompanied by an ‘Informative Note’. The government uses informative notes as guidance to identify an error in the standard (for example where an incorrect date has been used), to provide a clarification on an ambiguity, or to advise additional or alternative actions for business to consider outside of the standard. Where additional actions are advised, it is intended to support businesses in their approach in understanding and managing risks that they may identify with their products.

Conformity assessment

32) Conformity assessment is the process of demonstrating whether specified ‘essential’ requirements relating to a product, process, service, system, person or body have been fulfilled. The ultimate purpose of any conformity assessment procedure is to ensure that products placed on the market conform to the requirements specified in the relevant legislation, and can therefore meet the required safety objectives.

33) A common modular approach has existed for over three decades and was set out by the EU in its Decision on a common framework for the marketing of products. The Decision sets out a series of standard modules for conformity assessment which should be selected by the manufacturer as prescribed by the legislation. These modules continue to be integral to EU-derived product safety regulations in the UK. Which modules apply, and whether these can be self-assessed or require assessment from a UKAS accredited third party conformity assessment body is determined by the potential risk posed by the product itself. [footnote 4]

Read Decision No 768/2008/EC on a common framework for the marketing of products – legislation.gov.uk

Conformity markings

34) For many sector-specific regulations, conformity to the essential safety requirements is demonstrated through a conformity marking. The UK’s independent regime has been operational since 1 January 2021. The UK Conformity Assessed (UKCA) marking is the conformity marking used for products being placed on the market in Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales). Therefore, where a product is covered by the UKCA marking and meets the relevant UK requirements, they are required to affix the UKCA marking on a product before placing the product on the GB market, as an attestation that all requirements have been met.

35) The Government has continued to recognise certain EU requirements, including Conformité Européene (CE) marking, the EU’s conformity assessment marking, to place relevant products on the market in GB. Continued recognition of CE marking means businesses can place goods on the GB market using either the UKCA or CE marking, thereby reducing costs for manufacturers, including those who place products on both the UK and EU markets. This approach also applies to aerosol dispensers and measuring container bottles, for which the reversed epsilon marking (which is used in the EU) can be used in GB.

36) The Product Regulation and Metrology Act’s powers provide the UK with the choice to either recognise updates to certain EU product requirements, including the CE marking, or to end recognition of these requirements. Any decisions on the use of these powers would be made in the UK’s best interests, and on a case-by-case basis.

Market surveillance and enforcement

37) Market surveillance forms part of the UK’s approach to regulation and enforcement, designed to provide high levels of consumer and environmental protection, promote consumer choice and support business growth. Market surveillance refers to the suite of intervention activities undertaken by relevant authorities that help protect consumers from non-compliant and unsafe products, and enables safe and compliant products to enter the market.

38) The UK’s comprehensive market surveillance and enforcement arrangements are underpinned by both primary and sector-specific secondary legislation. Guidance for Market Surveillance Authorities (MSAs) was produced in 2020.

Read guidance for MSAs on Regulation 765/2008 on Accreditation and Market Surveillance.

The Office for Product Safety and Standards (OPSS)

39) Since 2018, OPSS has led and coordinated the UK’s product safety regime. OPSS is the UK’s national product regulator, providing scientific and technical capability, investigation and enforcement particularly in relation to cases that are nationally significant, novel and/or contentious, and working with local authorities, other market surveillance and border control authorities. OPSS has invested in research into product hazards and centralised the coordination of intelligence and checks for unsafe products at UK ports and borders.

40) OPSS leads a national programme of regulatory action to tackle the risks from unsafe and non-compliant goods sold on online marketplaces. OPSS has responsibility for UK market surveillance policy and co-ordination. It is the MSA for a range of other product regulation issues such as weights and measures. OPSS can commission the development of Publicly Available Specifications (PAS), sponsoring BSI to bring together experts to provide fast-track standardisation documents, specifications, codes of practice or guidelines to meet an immediate regulatory need. OPSS can issue product safety alerts, and issue statutory guidelines under GPSR.

Other national market surveillance and enforcement authorities

41) Depending on the regulatory area, specific expertise or location of equipment use, market surveillance and enforcement is also delivered by a range of national and local bodies. The relevant authorities include (but are not limited to) local authorities, [footnote 5] the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), HSE Northern Ireland (HSENI), the Office for Nuclear Regulation (ONR), the Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory products Agency (MHRA), Office of Communications (OFCOM), the Office of Rail and Road (ORR), the Driver and Vehicle Standards Agency (DVSA). [footnote 6] Each MSA is individually responsible for setting risk-based priorities and reporting outcomes. National MSAs are accountable to their policy department within government, while local authority regulatory services undertaking market surveillance activities are accountable to local democratic structures.

Primary Authority

42) Primary Authority (PA) scheme was established by the Regulatory Enforcement and Sanctions Act 2008 to improve consistency in the delivery of local regulation. It allows a business or group of businesses (usually a trade association) to form a legal partnership with a single, local authority regulator who can advise them on compliance with laws enforced by Trading Standards, Environmental Health or Fire and Rescue Services. Other local regulators have to take account of the advice given, making it easier for businesses to comply with the law. Most major retailers have a PA partnership, as do many manufacturers. Currently, over 100,000 businesses have registered for PA.

Points of entry into the UK

43) Market surveillance at points of entry into UK is one of the regulatory tools used to detect, disrupt and deter unsafe and non-compliant goods from entering the market. OPSS has responsibility for developing national capacity for product safety in the UK. One of the ways it does this is to enhance capability to understand the data on imports and fund regulatory activity at UK ports and borders. OPSS is consolidating and enhancing the effective use of data and intelligence on unsafe goods and on economic operators that have a track record of non-compliant activity. OPSS operates a Border Profiling Service (BPS) for all local authorities, working closely with HMRC. This enables OPSS to share data and intelligence with MSAs operating at ports and key points of entry, and to improve how they use their resources based on risk.

44) The BPS has expertise in market surveillance and customs procedures and provides support to MSAs in relation to border controls, practices and processes. It makes referrals to MSAs, so they can act in real time at entry points when consignments are identified that pose a risk. The benefits of this approach include the ability to identify national emerging trends and threats, identification of high-risk economic operators working across areas within the legislative competence of different MSAs, and to ensure consistency of approach at border points in line with best practice. The work of the BPS is one way that OPSS fulfils legal obligations to take account of established ‘principles of risk assessment’. [footnote 7]

45) In the UK, HMRC and Border Force are the relevant Border Control Authorities, holding data and documentation about imports. They are the designated Border Control Authorities in NI for the purposes of the EU Market Surveillance and Compliance of Products Regulation 2019. The information contained within customs declarations and supporting documents is profiled to target products and economic operators that present the greatest risk to users.

Product Safety Database

46) The UK Product Safety Database (PSD) is the notification system used by local authority trading standards (environmental health in NI), certain national regulators and OPSS enforcement teams to notify unsafe and non-compliant products to the Secretary of State, as required in product safety legislation. [footnote 8]

47) The PSD is a core dataset for OPSS, providing insight into the market surveillance activity of regulatory officers across the UK and highlighting where the greatest levels of activity are taking place in terms of product sectors, as well as providing an oversight of the most reported hazards and corrective actions taken. Analysis of PSD data can also highlight where there may be emerging safety issues for novel products and within certain sectors, which can feed into and drive OPSS’s decision making and regulatory activity, reduce risk and protect consumers.

Incident management

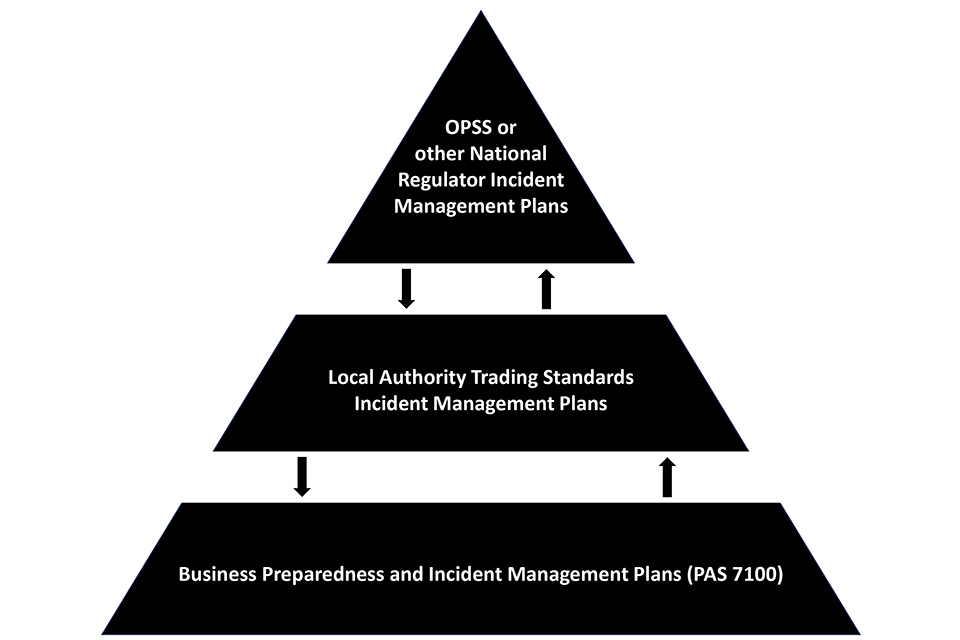

Figure 1: hierarchy of product safety incident management plans

48) The responsibility for enforcing rules under the product safety regulatory system lies primarily with local authority trading standards in GB and district councils in NI (local authorities). However, as referenced above, some regulations are also enforced by other regulators such as HSE. OPSS provides national leadership across the regulatory system and takes the lead particularly where the issue is considered to be nationally significant, novel or contentious.

Figure 2: OPSS product safety incident triage process

49) OPSS’ framework for identifying and responding to incidents is set out in its published Incident Management Plan. Potential incidents may be identified from a range of internal and external sources including, but not limited to, national and international regulators, Ministers, other Government Departments, emergency services, local authorities (e.g. trading standards, building control, etc.), businesses, trade bodies, media coverage (including social media), members of the public and other stakeholders. The Incident Management Plan provides comprehensive guidance on how OPSS identifies, assesses and manages incidents, emergencies and disruptive events across its regulatory responsibilities.

Read the Incident Management Plan.

Criteria to assess if an issue should be led by OPSS or the local authority:

- Nationally Significant – the resourcing and/or expertise needed to investigate is beyond the capacity of an LA, there is a high level of public concern and national interest; and/or

- Novel – the risks of the usage of a product are unknown and unquantified; and/or

- Contentious – instances in which a single, centrally delivered answer is required to minimise the potential for dispute between industry, regulator, and other stakeholders.

One or more of these three triggers could be used to delineate OPSS led activity from local authorities.

PRISM

50) The Product Safety Risk Assessment Methodology (PRISM) is for use by MSAs and enforcing authorities in GB with responsibility for consumer product safety. It is aligned with the EU Safety Gate approach (RAPEX) and reflects the same risk level matrix. PRISM was launched by OPSS in 2022 after extensive engagement with local authorities and national regulators and has resulted in more robust and informed risk assessments. Relevant authorities can record their risk assessment as part of the notification process. In addition, multiple hazards can now be combined where the toolkit will calculate new probability levels for the product.

Taking enforcement action

51) The Regulators’ Code provides a clear, flexible and principles-based framework for how regulators should engage with those they regulate. Nearly all regulators, including local authorities and fire and rescue authorities, must have regard to it when developing policies and procedures that guide their regulatory activities. Most set out in their guidance for businesses on their websites their enforcement policies. Businesses can therefore have confidence how enforcement authorities will act, and what they need to do to communicate and collaborate with them effectively.

52) Local authorities each have their own arrangements for taking enforcement action when an issue is identified, using PRISM to guide their thinking. In addition, the Chartered Trading Standards Institute’s Code of Professional Conduct supports consistency across local authority areas.

Read the CTSI Code of Professional Conduct.

53) Published guidance sets out the approach of OPSS as national regulator for product safety to address non-compliance by those it regulates. This commits OPSS to delivering regulation in a manner that is risk-based, proportionate and consistent, aiming to be transparent and accountable about its regulatory approach and activities. OPSS’ primary concern when non-compliance or product safety risk has been identified is to ensure protection for people and the environment; and to ensure adequate steps are taken to address the issue and to minimise the likelihood of recurrence. OPSS uses the tools and powers available to them to hold businesses to their responsibilities and will undertake sustained and escalating interventions where necessary. Where other regulators lead national compliance activities, they too have their own plans and policies in place. [footnote 9]

Read the OPSS enforcement policy.

Statement of intent

54) Working together, government, business and consumer groups have developed a robust regulatory system of legislation, guidance, standards, and non-legislative based tools to assess risk and target market surveillance and enforcement activities. The complex landscape is based on a simple principle, that all products must be safe. Many actors, from economic operators to statutory authorities, play their part in operating and developing the system, with statutory and non-statutory feedback mechanisms to improve it.

55) The UK product safety regulatory system protects people from product related harm. But as technology develops and supply chains become even more complex and interconnected, this has created significant challenges to the product safety framework. It is right that policy makers look at where industry and consumer groups are saying improvements can be made.

56) Business and consumer groups are now looking to government to respond to these new challenges to ensure that products in new and existing supply chains are safe and that legitimate businesses have a fair playing field, promoting growth. Further legislation will be required to update the regulatory framework so that modern supply chains and new and emerging business models are captured with clear, proportionate and targeted duties to ensure only safe products get into the hands of UK consumers.

57) The legislative process must be robust enough to ensure proper Parliamentary oversight, and agile enough to respond to consumer and business need in the fast-developing global marketplace. The Product Regulation and Metrology Act provides the necessary powers, underpinned by robust consultation, impact assessment and oversight processes.

58) As set out in its response to the Product Safety Review and during the debates on the Product Regulation and Metrology Bill, the Government put forward the following areas for potential reform or further review:

- online marketplaces

- cross cutting hazards

- the regulation of higher risk product sectors

- diverging from or mirroring EU requirements

- digital labelling

- technological change such as automation of machinery, 3D printing, augmented reality

- introducing an emergency derogation procedure

- introducing civil monetary penalties

- information sharing

- recovery of enforcement costs by local authorities

- gun barrel proofing

Read the Government response to the Product Safety Review.

Read the Lords debates on the Product Regulation and Metrology Bill. – Hansard, UK Parliament website

59) If new or amended regulations are required, paragraphs 60 to 111 set out the mechanisms the Government employs to develop product safety policy and legislation, and Figure 3 illustrates the processes involved.

Future regulation

Figure 3: process for developing current and future product safety policy and legislation

Identification and pre-consultation

60) Regulation should be seen as a last resort where non-legislative options are either not appropriate or have not worked. Policy makers are utilising a number of methods to identify new or emerging challenges before regulation is considered.

61) Intelligence-led policy making is by far the most common way in which new challenges and potential solutions are identified. Through ongoing, regular industry and consumer engagement, issues can be raised and discussed, leading to the gathering of relevant evidence. OPSS engages regularly with businesses and sector-specific trade associations, through member events and workshops, through OPSS’ Business Reference Panel and Business Accountability Forum, and with cross-cutting groups such as the British Retail Consortium, to discuss emerging product safety issues, and the sort of remedies and interventions that would resolve any problems, promote sector growth, and reduce friction in the delivery chains. The intelligence gathered through these discussions is shared with policy and compliance teams alike. Intelligence can also arrive through reporting of specific incidents by compliance teams or the PSD. OPSS, as the national regulator for product safety, maintains strong relationships with local authorities, other regulators and the emergency services, sharing information and knowledge to ensure a joined-up approach to dealing with new issues.

62) In addition, it is important that the existing body of regulation is kept under review to ensure it remains relevant and effective. Since the UK left the EU, UK policy makers have been looking at specific sectors and sets of regulations and considering where changes are needed, whether this relates to new products, hazards or actors in the supply chain. The previous Government undertook a Call for Evidence in 2021 and a full public consultation in 2023 to support this process.

Case Study: The Product Safety Review

The Product Regulation and Metrology Bill was introduced following a fundamental review of the UK product safety framework launched in 2019. A Call for Evidence in 2021 received 158 responses and 80 organisations attended eight roundtable discussions. The then Government’s response, published in November 2021 identified the main themes from the responses.

A full public consultation was launched in August 2023 and received 126 written responses. In addition, 53 stakeholder events were undertaken by officials in the Department for Business and Trade, reaching over 400 businesses, consumer groups and other stakeholders where views were collected.

Responses to the Consultation, and the discussions at stakeholder events, were central in developing the case for the powers in the Product Regulation and Metrology Bill.

63) To supplement the Review, OPSS undertook a horizon scan of potential future and emerging technologically driven changes, that policy makers and regulators should be considering as they review the product safety landscape. This represented OPSS’ first horizon scan and identifies a number of areas of immediate interest, setting out the methodology used to determine these areas. This document was published in November 2024.

Read the OPSS horizon scan 1.0.

Assessment

64) Modern supply chains and the way in which products are made and used today make the identification of compliance issues more complex and challenging. No longer is it sufficient to simply focus regulatory attention on the manufacture and sale of a particular product, particularly given the focus of the regulatory framework beyond simple consumer products to a range of industrial and technical products. All aspects of a product’s lifecycle must be considered to ensure that any safety issues are identified, examined and addressed, and the most appropriate intervention is determined, whether this is legislative in nature or not. In many cases a combination of legislation, guidance and support delivers the most effective results for businesses and consumers alike.

Figure 4: the product life cycle

65) Figure 4 above shows, at a high level, the complexity of the modern product lifecycle, with the stages on the left more common in consumer products and the right, more common in industrial products. Where new hazards or risks are identified, it is important to consider all aspects of this cycle before settling on a proposed intervention. Much of the consideration will be product specific, but an indication of the issues to be considered are included below.

Design and manufacture

66) The existing sector specific regime provides for requirements that must be met both at design stage and at manufacturing stage, particularly for higher risk products. It further provides that conformity assessment procedures must take place at design stage, followed up by further testing at manufacturing stage. For example, legislation such as the Pressure Equipment (Safety) Regulations 2016 and the Lift Regulations 2016 include conformity assessment module H1 (full quality assurance plus design examination) in their range of testing modules.

67) In an ever-expanding digital world, the safe design of products, for instance, through templates that can be printed by the end user, is becoming more important. As new risks and hazards are identified, safe product design will need to be considered more often, with the creation of new standards and tools in the non-legislative space, and further development of conformity assessment in the legislative space.

68) Manufacturers already have a range of responsibilities. As new products are developed, particularly in higher-risk sectors, it is important to determine the most effective way of mitigating the potential for harm. This can include restricting the raw materials or chemicals used in a product, through to the qualifications required to undertake work, such as chemical risk assessment or industrial welding. The Product Regulation and Metrology Act provides powers to amend the relevant requirements to keep abreast of the latest technological developments and ensure the UK does not become a dumping ground for products that other markets have deemed unsafe.

69) Regulatory activity and standards can also play a role in ensuring inclusive design of products. For products to be truly safe, they should be able to be used safely by all users. This means the design and manufacture of a product should take account of all users’ needs and capabilities. There are a range of ways to support this: standards on inclusive design help businesses ensure their design processes are set up to consider the needs of all users; there are market incentives to providing products that can be used by the widest possible user-base; and regulations are there to ensure products can be used safely by everyone, or have the appropriate warnings and safeguards as to e.g. age appropriateness. As the Government uses the powers in the Product Regulation and Metrology Act to update the UK’s product regulation regime, it will consider the role that any new or updated regulation, for particular sectors or that cut across products, can play in ensuring inclusive design.

Placing products on the market, transportation and use

70) The increase in e-commerce has transformed global supply-chains and the way we purchase products, creating increasingly complex supply chains with new and emerging business models. Product safety legislation includes requirements that aim to ensure that only safe products are made available on the UK market. These include requirements on producers, distributors, manufacturers, authorised representatives and importers. The Product Regulation and Metrology Act enables further requirements to be introduced on other persons carrying out activities in relation to a product where necessary.

Product Regulation and Metrology Act – persons on whom product regulations may impose product requirements

Within section 2, the Act provides a non-exhaustive list of examples of persons on whom regulations may be imposed. Supply chains are becoming increasingly complex with a vast range of actors involved in the product journey that may need to be captured by product regulations, depending on the nature of the product or its supply chain.

This is why section 2(3)(i) makes it even clearer that relevant persons carrying out activities in relation to products may be subject to regulations. Examples that demonstrate the different actors that this clause captures include:

- Furniture re-upholsterers, who add upholstery to a product in the course of upholstery or repair, have duties to comply with the Furniture and Furnishings (Fire) (Safety) Regulations (1988).

- Product safety requirements on pressure equipment manufacturing capture certification of permanent joining (welding) personnel, non-destructive testing personnel, material appraisal, and material manufacturers’ quality assurance systems.

Fulfilment service providers, which are becoming increasingly significant with growing e-commerce and global supply chains, have a range different business models and activities.

71) The safety of a product must not be compromised while it is being moved. From batteries to aerosols, regulations and guidance place obligations on importers and distributors, for example, to support the safe transportation of higher risk products before sale to consumers. Where new risks or hazards are identified, the Product Regulation and Metrology Act enables regulations regarding safe transportation to be amended to take these into account.

72) Products can be safe at the point of sale but then used incorrectly. Existing regulations set out requirements for user information and instruction to be provided, but sometimes further awareness material is required, with a number of national campaigns to promote safety, for instance around button batteries and fireworks, undertaken by the national regulator. This is also true of the risks associated with charging e-bikes and e-scooters, where DBT has recently launched an information campaign to promote safer purchasing, charging and use. The Product Regulation and Metrology Act enables regulations covering the provision of relevant information to be amended and strengthened, and to ensure consistency where the component parts of a product are covered by different regulations.

Installation, putting products into service and maintenance

73) Installation requirements have been an essential part of some sector-specific regulations for years, such as lifts. However, as technology evolves and end products become more reliant on software, computers or mobile power supplies, it is important that risks associated with the interoperability of various components are considered, and that product safety regulations can be amended to take account of ‘smart’ products, or those where AI is being introduced.

74) While there is some overlap with installation, for some products such as machinery and recreational craft, additional requirements are sometimes put in place before a product is used for the first time. This can include the professional qualifications of the person placing the product into service or specific testing requirements for safe usage. It is important regulations can be amended quickly to take account of changing professional development requirements, and do not prevent the implementation of improved best business practice.

75) Many industrial products also require maintenance over time – whether this is physical maintenance such as servicing or digital maintenance such as software upgrades. Where this is the case, consideration should be given as to whether any additional requirements or restrictions need to be put in place to ensure the integrity of the product’s safety, particularly as AI is introduced to trigger or carry out these functions.

Resale, refurbishment and repair

76) The growth of the circular economy has increased the need to consider product safety as it applies to the sale of second-hand products. Many online marketplaces and high street shops now specialise in the facilitation of second-hand product sales. Similarly, there continues to be a vibrant market in second-hand sales of industrial products and heavy machinery, which requires effective regulation to protect the safety of end users.

77) Some products such as upholstered furniture can be refurbished, while others are increasingly ‘upcycled’ to reduce wastage in the economy. Where this is the case, it is important to determine any potential risks to end users and decide whether additional labelling and regulation is required.

78) To ensure maximum levels of sustainability across the economy, consideration is needed about what can be done to support a move away from a throwaway society. In 2021, a right to repair for certain products was introduced, providing ‘professional repairers’ with access to spare parts and technical information. The ongoing review of product safety must consider how accessibility to spare parts can be provided for in a safe way. The Product Regulation and Metrology Act gives regulation-amending powers to ensure the right balance of responsibility between economic operators, consumers, and statutory market surveillance and enforcement authorities.

Modification and upgrade

79) Many products can be adapted throughout their lifecycle into new products that provide a different use. These modifications cannot always be anticipated by a manufacturer or distributor at the point of initial sale. As an example, more recently, we have seen modification kits made available, allowing consumers to convert pedal bikes into e-bikes, which raises significant safety concerns. The Product Regulation and Metrology Act provides regulation-amending powers where an update to, for example, essential safety requirements is needed to take into account potential and actual modifications and consequential new risks or hazards.

80) In the past, upgrading equipment normally involved replacing the entire product with the most up to date version. However, in today’s modern, digital world, and the focus on sustainability, upgrading can be as simple as downloading a new piece of software – sometimes automatically without the end user’s knowledge. When this happens, the safety of the product must not be compromised. Should this aspect need strengthening in product safety regulations, the Product Regulation and Metrology Act gives the necessary regulation-amending powers.

Recycling and disposal

81) As products get to the end of their life, it is now becoming more common for them to be broken up into component parts and partially recycled. Whether this is the critical raw materials in electronic devices or the lithium-ion batteries in e-bikes, new homes and uses for old products potentially present their own safety risks which must be considered by policy makers and new essential requirements included in product safety regulations.

82) When a product does finally come to the end of its lifecycle, it is important that it can be disposed of in a safe and sustainable way. This can require information on the chemical composition of certain products to avoid automatic landfill, to construction in a way that is easily and safely broken down for disposal. As with new battery technology, this can come with its own serious risks which need to be considered as part of the regulation of a product.

Emergency situations

83) The Covid pandemic highlighted the importance of ensuring the UK’s future regulatory system allows flexibility in times of national emergency. The powers in the Product Regulation and Metrology Act ensure that the new regulatory system provides for an emergency derogation, so that essential products go through a swifter regulatory process, allowing them to reach the market more quickly, whilst maintaining high, but proportionate, safety standards.

84) This emergency derogation builds on the emergency measures that were introduced as part of the Government’s COVID-19 response, to support the faster supply of essential Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) to health workers. At the time, the taskforce which led the national effort to produce PPE urged OPSS to establish a derogation process, similar to that of the Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory products Agency (MHRA).

85) The Government proposes to allow businesses to apply to be party to a derogation from certain aspects of product safety legislation, to help ensure supply of products that are critical during an emergency, whilst continuing to maintain high safety standards. The derogation would only be available if the emergency situation meant that there was serious risk of harm to people, businesses or the environment, and would be in compliance with the UK’s international obligations. It would only be granted for products deemed critical for the emergency response and where demand is outstripping supply. This would enable products to be placed on the market faster than would otherwise be the case. The necessary legislation would be subject to an affirmative resolution in both Houses of Parliament.

86) Regulatory requirements that could be temporarily eased including by allowing products to be placed on the market without a conformity marking, if the conformity assessment process was underway and the relevant MSA was content with the safety of the product. Government may also temporarily reduce the requirements for the product to meet essential health and safety requirements for use in certain settings, as long as the MSA was content with the safety and traceability of the product.

87) Compliance and enforcement measures would be put in place to ensure only safe products are placed on the market and help maintain a competitive market. Businesses that received approval for a derogation would need to make appropriate arrangements to ensure products falling under the derogation were only used in the circumstances permitted by the derogation, and that once the derogation came to an end, these products were immediately removed from the market. Similar to the approach of MHRA, this would involve assurances to the MSA that the derogation conditions are being met and that the products have been removed from the market at the end of the derogation.

88) The MSA would closely monitor compliance and take prompt action where necessary, such as immediate suspension of the derogation, requiring immediate removal of the ‘eased’ products from the market.

Pre-consultation – regular ongoing engagement with industry and consumer groups

89) Identifying a new issue does not necessarily mean that regulation is the most appropriate next step. Sometimes improving user awareness or business guidance is a more appropriate intervention to ensure user safety. To understand what may be required, policy makers engage businesses and consumers, and any others likely to be impacted by any potential future changes, to understand the issue in more detail, pinpointing the specific problem that needs addressing, establishing and assessing the various interventions that are available. [footnote 10]

90) This involves considering the full end-to-end process, whether that relates to how a specific product finds its way onto the market or how it is produced in the first place. It is essential to look carefully at all aspects of the supply chain, from the raw materials used and design principles, through manufacture, installation and, ultimately, disposal. It is also important to consider the needs and capabilities of all users of a product, to ensure regulatory activity can support inclusive design across the economy.

91) If regulation is considered necessary, what penalty regime should be put in place to act as a deterrent to unscrupulous businesses and protect consumers? This should be proportionate to the potential harm that could be caused by a particular product. For instance, where the potential harm caused by a non-compliant product is low, such as a minor skin irritation, this should be reflected in the potential penalty. Where the potential harm is high, such as serious injury or death, businesses should know that the penalty is significant too.

92) The regulatory system supporting product safety in the UK covers everything from low-risk consumer products like books and knitting patterns through to the heavy machinery used on building sites and the pressure equipment installed on oil rigs and in power stations – and so the penalties for non-compliance need to be adaptable. In some cases accepting undertakings may be the best method of ensuring compliance, while imposing civil penalties may have the best deterrent effect. Unlike the situation now, the Act provides powers to do both.

Consultation

93) The consultation process needs to adapt depending on the scale of the challenge. For instance, when considering the framework as a whole, it was right to undertake a full public Call for Evidence, followed by a full public consultation with significant stakeholder engagement, as was the case with the Product Safety Review. A similar approach to consultation was taken to examine proposals for changes to the furniture fire safety regime. In that case, draft regulations were also published alongside the consultation to inform that discussion. It is also usual for feedback and summaries from consultation responses to be published along with the conclusions drawn, either by way of Government response to a consultation or other form of policy proposal.

94) However, in the case of chemical safety in toys and cosmetics, a more targeted approach is taken, issuing Calls for Data on specific chemicals before sharing this data with, and tasking, the Science Advisory Group on Chemical Safety in Consumer Products (SAG-CS) so they can provide an opinion. Those scientific opinions and recommendations are then published and more targeted consultation with industry is undertaken before bringing forward changes to the law.

Science Advisory Group on Chemical Safety in Consumer Products (SAG-CS)

The Scientific Advisory Group on Chemical Safety of Non-Food and Non-Medicinal Consumer Products (SAG-CS) assesses and advises on chemical and biological risks to humans. SAG-CS is a scientific advisory group, commissioned by OPSS.

The SAG-CS is commissioned by OPSS and is supported in drawing evidence together by its secretariat before producing an opinion. A SAG-CS opinion is a document which describes the conclusions and advice from a SAG-CS discussion. Opinions will normally contain the key points discussed within a meeting alongside the responses to the questions considered.

95) A similarly targeted approach was taken for a small change to the Pressure Equipment (Safety) Regulations 2016 to remove friction in the supply chain of materials. The proposal arose from regular discussions with UK pressure equipment manufacturers, relevant trade associations and the UK Pressure Equipment Conformity Assessment Bodies, and solutions developed through workshops with representatives, and then wider consultation within the sector.

96) The mandatory Explanatory Memorandum that accompanies the legislation sets out a summary of the consultation outcome and methodology, and the impact on businesses (particularly small and micro businesses), charities and voluntary bodies.

Criminal sanctions

97) The sector-specific product safety regulations each provide for a similar range of criminal sanctions. When thinking about change in this area, consideration has always been, and will continue to be, given to similar areas of law, the developing body of thought to the purpose and effect of remedies and sanctions by regulators, [footnote 11] and the guidelines issued by the Sentencing Council. While fines are the most likely recourse, it is right sanctions such as imprisonment are available for the most serious offences – for instance where there has been a blatant disregard for product safety law by a manufacturer, resulting in the serious injury or death of a child or vulnerable person.

98) Discussions with experts in the criminal justice system and other interested parties, as well as wider consultation, ensures that any proposed criminal sanctions are consistent with similar areas of law, and proportionate to the redress expected by victims. Where any new criminal offence is included in product safety secondary legislation, the maximum term of imprisonment will reflect the seriousness of the potential harms, but will not exceed two years, and only that when convicted on indictment. Most proceedings are likely to be summary proceedings, for which the maximum custodial sentence as set out in the Act is e only three months maximum. To ensure appropriate Parliamentary scrutiny for future product safety regulation, the affirmative procedure will apply to any secondary legislation that creates or widens the scope of a criminal offence.

Changing the law

99) If the Government decides that regulation is the best solution, it can begin the process of preparing a Statutory Instrument. As well as ensuring the policy outcomes are effectively delivered in the legal drafting, policy makers must consider wider social, environmental and economic impacts and present these to ministers and Parliament. These checks and balances establish clear guardrails and ensure rigorous scrutiny of the full implications of regulation ahead of any changes to the law.

100) The main checks and balances include:

- Continuing to work, post-consultation, with industry experts and other consultees on the development of the policy underpinning the legislation. Discussions with policy makers in Other Government Departments (OGDs) and regulators, and with the Government Legal Profession, to ensure consistency of approach including in cross-cutting regulations, such as the Restriction of Hazardous Substances Regulations and the Waste Electrical and Electronic Regulations, culminating in the requirement to obtain Ministerial Write-round approval for clearance of the final proposals, which is part of the Cabinet Committee process and procedure.

- Discussions with the Devolved Governments about proposed changes and seeking their consent when proposing to bring forward legislation that covers devolved areas. Although product safety is largely a reserved matter, any proposed changes must not unintentionally cut across any existing or proposed devolved areas of legislation. Where proposed secondary legislation has provisions that are within devolved competence, the Secretary of State is required to seek the consent of the relevant Devolved Government for those provisions before making this legislation, unless the devolved provisions are merely incidental to, or consequential on, provisions outside devolved competence.

-

Application of the principles of Better Regulation and the revised Better Regulation Framework, [footnote 12] recognising that regulation should be:

- proportionate to the problem it seeks to solve, targeted in its effects, consistent in its design and transparent and accountable to Parliament and the public in the way it is made

- justified in terms of any necessary costs it places on businesses, non-profit organisations or households

- taken forward only after alternatives to regulation have been fully considered;

- developed with earlier and more holistic scrutiny of wider impacts beyond direct costs to business

- implemented with consistent monitoring and evaluation

- The development of an Options Assessment, for provisions in scope of the Framework and not otherwise excluded or exempt, for scrutiny by the Regulatory Policy Committee.

- The development of an Impact Assessment, reviewed by the Regulatory Policy Committee, and where relevant thresholds determine, published alongside any legislation.

- A Small and Micro Business Assessment (SaMBA) and Medium-sized business regulatory exemption assessment, to mitigate any disproportionate impacts on micro, small and medium-sized businesses.

- A UK Internal Market Assessment, to ensure new regulations support the free flow of goods and services across every region of the four nations of the UK. [footnote 13]

- An Environmental Impact Assessment, to fulfil the environmental principles duty that came into effect in November 2023 to ensure we leave the environment in a better state for future generations. In the case of product safety, this consideration can take many forms, most recently seeing sustainability options examined in new labelling requirements for furniture fire safety regulations. [footnote 14]

- An Equality Impact Assessment, in line with the statutory duty on listed public authorities and other bodies carrying out public functions. [footnote 15] It ensures that those organisations consider how their policies, programmes and services will affect people with different protected characteristics.

- A Justice Impact Test, that specifically considers the impact of government policy and legislative proposals on the justice system. [footnote 16]

- A New Burdens Assessment, to justify why new duties, powers, targets and other bureaucratic burdens should be placed on local authorities, to help keep the pressure on council tax bills to a minimum.

- Consideration of the interaction between proposed changes and any wider international legal obligations, such as those agreed in trade deals. Giving appropriate notification of legislative changes to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in fulfilment of the UK’s commitments to notify international partners of new legislation during the legislative process to give countries the opportunity to influence them, and international businesses time to prepare for new rules. [footnote 17]

- Consideration of the government-wide target to reduce the administrative costs of regulation on businesses by 25% by the end of this parliament.

101) A summary statement of how product risk is identified and assessed, set out in detail in Annex B, was made to Parliament on 22 July 2025. [footnote 18]

Parliamentary scrutiny

102) Policy makers work closely with legal advisers to draft effective secondary legislation that delivers the desired outcome in the most proportionate way. This is based on the consultation and analysis set out above before beginning the process of parliamentary scrutiny.

Parliamentary Committees

103) The Joint Committee on Statutory Instruments is appointed to consider statutory instruments made in exercise of powers granted by Act of Parliament. The Joint Committee is empowered to draw the special attention of both Houses to an instrument on any one of a number of grounds specified in the Standing Orders under which it works; or on any other ground which does not impinge upon the merits of the instrument or the policy behind it.

104) The Secondary Legislation Scrutiny Committee examines the policy merits of statutory instruments and other types of secondary legislation that are subject to parliamentary procedure. Routine policy scrutiny applies to all Statutory Instruments and other types of secondary legislation that are subject to parliamentary procedure (including proposed negatives being re-laid after sifting). It examines the policy content and intended outcome of the legislation to consider whether it is interesting or flawed, using the criteria in its terms of reference.

Read the SLSC Terms of Reference.

105) While they do not have a formal role, other Parliamentary Select Committees, such as the Business and Trade Select Committee, or a number of All Party Parliamentary Groups can also consider regulations and request further information and oral evidence from ministers or senior officials.

Parliamentary debate

106) Previous regulations on product safety have required a mix of negative and affirmative procedures, normally informed by the level of change being proposed, and determined by what Parliament has agreed to be the appropriate procedure. The same approach was taken for powers in the Product Regulation and Metrology Act to reflect the mix of legislative updates that the powers could introduce – from new duties on online marketplaces, to very technical updates to existing regulations, such as chemical levels in cosmetics or on toys.

107) For the purposes of product safety, the Act requires statutory instruments to be laid using the affirmative procedure in a number of areas:

- Where a new power of entry is created

- Where regulations are disapplied in the case of an emergency

- Where a criminal offence is created or widened

- Where information sharing provisions are introduced

- Where cost recovery procedures are established

- Where changes are made to primary legislation

- Where the definition of an online marketplace is amended

- Where requirements relating to the marketing of products on online marketplaces are introduced for the first time

- Where requirements on persons who control online marketplaces are introduced for the first time

- Where requirements on new categories of person under section 2(3)(h) are introduced for the first time.

108) The overwhelming majority of regulations made under the powers in the Product Regulation and Metrology Act will therefore require the affirmative procedure, with only a small number being too small and technical in nature to warrant a debate – although the standard parliamentary procedure applies should MPs or Peers wish to generate a debate.

Post-Implementation Review

109) Ministers have had a duty under the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015 to include a statutory review provision in new secondary legislation that has a regulatory effect on business unless it is not appropriate to do so. Guidance has been published to support this process. Most EU-derived product safety legislation includes such a review provision.

Read the post-implementation review guidance.

Implementation

110) Changes to product safety policy, especially changes in legislation, will be undertaken through effective consultation with all relevant stakeholders throughout the process of policy development. However, when new legislation takes effect, government will ensure that it is effectively communicated so that businesses are supported in compliance, MSAs are able to enforce the law and consumers know what they can expect.

111) As well as producing guidance, government is engaging directly with relevant stakeholders to answer questions and help prepare them for the changes. In recent years this has included working with the BSI on new British Standards, holding drop-in sessions for businesses with policy officials and running roadshows to communicate changes.

Summary

112) From policy through to delivery, when identifying potential product safety hazards and risks, through to developing interventions and implementing new laws, government ensures it collaborates widely to deliver positive outcomes. Through regular, ongoing engagement with industry and consumer groups, issues are discussed, problems examined, causes identified. Potential solutions are then teased out through further debate and discussion. These are then tested through wider engagement and consultation processes, dependent on the scale of the problem the impact of the proposed solution(s). If national regulation is in scope, a number of guardrails automatically come into play, and policy makers must give evidence-based assessment on the likely effects of new proposals in terms of costs and benefits to society, to the taxpayer, on different segments of the population, on the environment, on the justice system, on local authorities. These assessments are subject to scrutiny by Ministers, experts and Parliament. Legislative change only occurs if these assessments are accepted, based on decades of experience of implementing product safety legislation, and as Parliament wills it, to ensure interventions are targeted, proportionate and protect consumers.

ANNEX A: GPSR definitions; Higher risk sector-specific regulations; conformity assessment modules; Regulators’ Code principles

A1) For the purposes of the General Product Safety Regulations 2005, ‘product’ means:

…a product which is intended for consumers or likely, under reasonably foreseeable conditions, to be used by consumers even if not intended for them and which is supplied or made available, whether for consideration or not, in the course of a commercial activity and whether it is new, used or reconditioned and includes a product that is supplied or made available to consumers for their own use in the context of providing a service. “product” does not include equipment used by service providers themselves to supply a service to consumers, in particular equipment on which consumers ride or travel which is operated by a service provider…

A2) In the General Product Safety Regulations 2005, a ‘safe product’ means:

…a product which, under normal or reasonably foreseeable conditions of use including duration and, where applicable, putting into service, installation and maintenance requirements, does not present any risk or only the minimum risks compatible with the product’s use, considered to be acceptable and consistent with a high level of protection for the safety and health of persons. In determining the foregoing, the following shall be taken into account in particular:

the characteristics of the product, including its composition, packaging, instructions for assembly and, where applicable, instructions for installation and maintenance, the effect of the product on other products, where it is reasonably foreseeable that it will be used with other products,

the presentation of the product, the labelling, any warnings and instructions for its use and disposal and any other indication or information regarding the product, and

the categories of consumers at risk when using the product, in particular children and the elderly.

The feasibility of obtaining higher levels of safety or the availability of other products presenting a lesser degree of risk shall not constitute grounds for considering a product to be a dangerous product…

A3) Sector-specific product safety regulations include:

- The Oil Heaters (Safety) Regulations 1977 (SI 1977/175)

- The Nightwear (Safety) Regulations 1985 (SI 1985/2043)

- The Furniture and Furnishings (Fire) (Safety) Regulations 1988 (SI 1988/1324)

- The Food Imitation (Safety) Regulations 1989 (SI 1989/1291)

- The Noise Emission in the Environment by Equipment for use Outdoors Regulations 2001 (SI 2001/1701)

- The Supply of Machinery (Safety) Regulations 2008 (SI 2008/1597)

- The Aerosols Dispensers Regulations 2009 (SI 2009/2824)

- The Toys (Safety) Regulations 2011 (SI 2011/1881)

- Regulation 2009/1223 on Cosmetic Products and the Cosmetic Products Enforcement Regulations 2013 (SI 2013/1478)

- The Pressure Equipment (Safety) Regulations 2016 (SI 2016/1105)

- The Simple Pressure Vessels (Safety) Regulations 2016 (SI 2016/1092)

- The Electrical Equipment (Safety) Regulations 2016 (SI 2016 1101)

- The Electromagnetic Compatibility Regulations 2016 (SI 2016/1091)

- The Lifts Regulations 2016 (SI 2016/1093)

- The Equipment and Protective Systems Intended for Use in Potentially Explosive Atmospheres 2016 (SI 2016/ 1107)

- The Radio Equipment Regulations 2017 (SI 2017/1206)

- The Recreational Craft Regulations 2017 (SI 2017/737)

- The Non-automatic Weighing Instruments Regulations 2016 (SI 2016/1152)

- The Measuring Instruments Regulations 2016 (SI 2016/1153)

- Regulation 2016/426 on appliances burning gaseous fuels and The Gas Appliances (Enforcement) Regulations 2018 (SI 2018/389)

- Regulation 2016/425 on personal protective equipment and The Personal Protective Equipment (Enforcement) Regulations 2018 (SI 2018/390)

A4) Conformity assessment modules

| Module | Title |

|---|---|

| A | Internal production control |

| A1 | Internal production control plus supervised product testing |

| A2 | Internal production control plus supervised product checks at random intervals |

| B | Type examination |

| C | Conformity to type based on internal production control |

| C1 | Conformity to type based on internal production control plus supervised product testing |

| C2 | Conformity to type based on internal production control plus supervised product checks at random intervals |

| D | Conformity to type based on quality assurance of the production process |

| D1 | Quality assurance of the production process |

| E | Conformity to type based on product quality assurance |

| E1 | Quality assurance of final product inspection and testing |

| F | Conformity to EU-type based on product verification |

| F1 | Conformity based on product verification |

| G | Conformity based on unity verification |

| H | Conformity based on full quality assurance |

| H1 | Conformity based on full quality assurance plus design examination |

A5) The Regulators’ Code principles

- Regulators should carry out their activities in a way that supports those they regulate to comply and grow.

- Regulators should provide simple and straightforward ways to engage with those they regulate and hear their views.

- Regulators should base their regulatory activities on risk.

- Regulators should share information about compliance and risk,

- Regulators should ensure clear information, guidance and advice is available to help those they regulate meet their responsibilities to comply.

- Regulators should ensure that their approach to their regulatory activities is transparent.

ANNEX B Risk identification, assessment, and response

The powers set out in section 1(1)(a) of the Act allow the Secretary of State to make regulations that seek to reduce or mitigate the risks presented by products. Section 1(4) of the Act sets out that, for the purposes of the Act, a product presents a risk if, when used for the purpose for which it is intended or under conditions which can reasonably be foreseen, it could:

a) endanger the health or safety of persons

b) endanger the health or safety of domestic animals

c) endanger property (including the operability of other products), or

d) cause, or be susceptible to, electromagnetic disturbance

This Annex summarises the process relating to the identification and assessment of risks in products, including in relation to risks which may be considered a higher risk.

The Secretary of State, through OPSS, identifies and assesses products posing a potential or actual risk, including where this would be considered a higher risk under conditions of use described above, through a range of methods. This can include, but is not limited to:

- risk profiling, using relevant Product Safety Risk Assessment Methodology

- examination of information about incidents recorded on the Product Safety Database and other relevant datasets

- intelligence from MSAs or other regulators, including international regulators, where appropriate

- evidence presented by industry groups and individual businesses

- evidence received through engagement with consumer groups or other expert product safety groups

- media articles or investigations

- Parliamentary debates and engagement, and letters from MPs on behalf of constituents

Once a product is identified as presenting a potential or actual risk, the Secretary of State will assess the possible risk to ensure proportionate, effective action is taken where necessary, at the right point and by the right actor in the supply chain. Where a product risk is identified and assessed as requiring action, the Secretary of State will work with product safety experts and regulators to determine the most appropriate intervention. This could include non-legislative interventions such as: