Rapid evidence review of community initiatives

Updated 20 June 2022

Executive summary

Objectives of this report

Levelling up is a core priority for the UK government. The recently published white paper Levelling Up the United Kingdom, defines it as “…giving everyone the opportunity to flourish. It means people everywhere are living longer and more fulfilling lives, and benefitting from sustained rises in living standards and well-being” (HM government, 2022, p1).

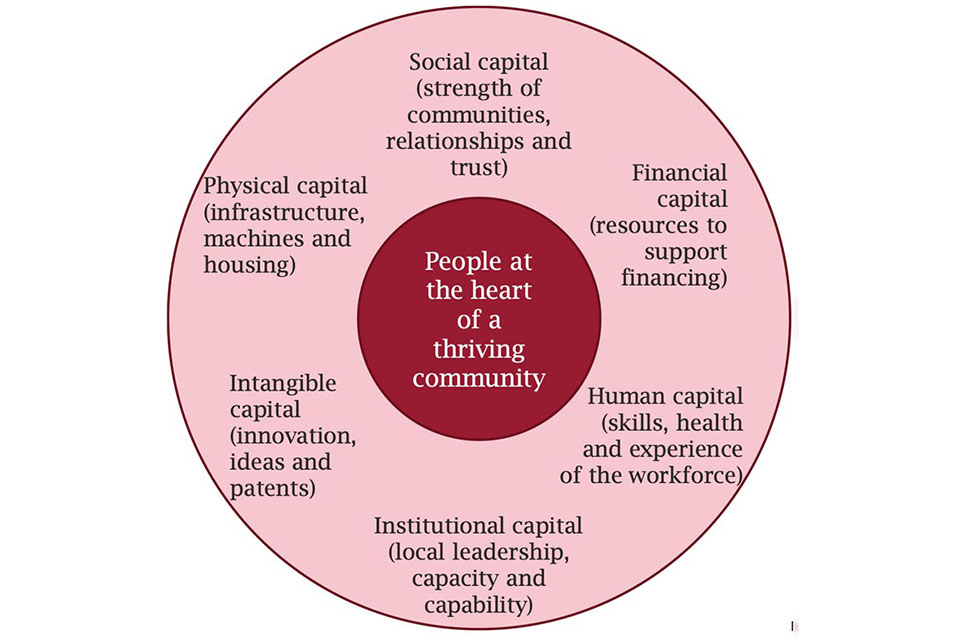

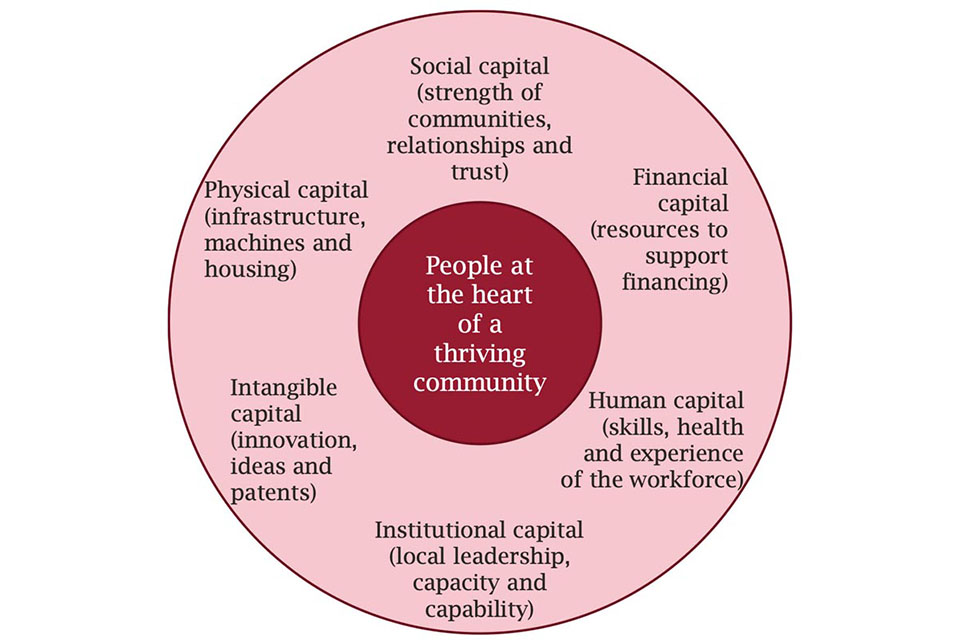

To drive towards these aims, several factors need to come together. These include six types of capital, as identified by HM government (2022): physical capital, human capital, financial capital, social capital, intangible capital and institutional capital. Existing evidence suggests that where these forms of capital and wider factors, including community infrastructure (a certain type of physical capital), come together, there can be a virtuous cycle of positive outcomes (HM government, 2022).

A preliminary assessment of the available evidence revealed that the definitions of the particular factors that enable communities to thrive are not consistent across studies, especially in relation to community infrastructure and social capital. There is also much still to be understood about how community initiatives can deliver community infrastructure effectively and enhance social capital.

Government is therefore interested in understanding the state of the current evidence base on these issues and where there are gaps or limitations in what is currently known. To build this understanding, the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), and the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) jointly commissioned this study.

The objectives of this study are:

-

To explore the definitions and concepts of community infrastructure and social capital to help government determine how and when to use different terminology.

-

To understand the strength and breadth of the evidence base about what works to deliver successful community (including community-led) initiatives to improve local community infrastructure and social capital.

-

To understand what could be considered “success” in community-led infrastructure initiatives and how government can deliver value-for-money interventions in this space. This includes the outcomes that could be considered success and the inputs that determine success.

-

To understand the strength of evidence on these issues, and identify gaps and how they could be filled.

Approach

This rapid evidence review was undertaken over a period of three months. Every effort was made to align with best-practice approaches to reviewing the evidence. A pragmatic approach to include additional relevant material was also applied, given the fragmented nature of the evidence and the breadth of terminology used in this space.

In total, more than 200 items of relevant evidence were identified, with over 100 shortlisted for more detailed review and synthesis. Evidence was shortlisted where it was assessed to be relevant for the objectives of this rapid review. The assessment of the quality of the shortlisted evidence reflected the robustness and transparency of the methods used by the authors. The strength of the evidence was assessed on both the quality of the research and the quantity of the research to identify where evidence for specific findings was strong, medium or limited.

The headline findings are below, with more detail in the main report.

Findings from the rapid evidence review

Factors that enable communities to thrive

For communities to thrive and unlock their potential, there is strong evidence that many factors need to work together simultaneously (e.g. Slocock, 2018). Some of these are shown in Figure 1 below. If any factor is missing or inadequate, this can constrain a community’s economic and social potential and its resilience. The factors include six different types of capital as identified in the government’s Levelling Up White Paper (HM Government, 2022), and these support thriving communities when they have certain characteristics, such as physical capital being inclusive (Yarker, 2019) and accessible (Tulloch, 2016). These characteristics are considered in more depth in chapters 4 and 5.

Figure 1: Factors enabling communities to thrive

Source: Frontier Economics; six types of capital from Levelling Up the United Kingdom, HM Government (2022)

Core definitions

There are many definitions used in published evidence relating to the concept of social infrastructure, with some studies including occupants and organisers for places and spaces and some including public services. This rapid review therefore adopts a specific definition for community infrastructure which is more narrowly defined and with a clear focus. The transparency over what is being referred to when the term “community infrastructure” is used is important.

For the purposes of this review, community infrastructure is defined[footnote 1] as the physical infrastructure within the community (including places, spaces and facilities) that supports the formation and development of social networks and relationships, either:

-

Directly: through how the physical infrastructure is purposefully used for bringing people together (for example, a green space or building where people and groups can meet for the purpose of participating in activities with other people from the community); or

-

Indirectly: by providing the infrastructure to enable individuals within a community to connect together. This includes physical connections (such as transport links) or complementary virtual connections (such as communication or digital technology that supports the physical meeting of people).

Typical examples of community infrastructure include sports facilities, libraries, some eating establishments, some places of worship (for example, if they have a community hall), gardens and parks. Some community infrastructure can be purpose built or can be a re-deployment of infrastructure delivered for another purpose. Some examples of community infrastructure are given below. This is not an exhaustive list but is intended to illustrate some of the different uses of community infrastructure.

The evidence suggests that core to identifying whether infrastructure is “community infrastructure” is how it is used (for example, Sinclair, 2019; Slocock, 2018). Section 3.1.2 discusses different examples. A common aspect of community infrastructure found across the literature is that it is often used for more than one purpose (for example, Archer et al., 2019; Henderson et al., 2018; Parsfield, 2015; What Works Centre for Wellbeing, 2018; South et al, 2021).

The definitions of social capital tend to be less diverse in the published evidence and, a commonly cited definition is from Putnam (1995):

…social capital refers to features of social organization such as networks, norms, and social trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit.

– (Putnam, 1995, p66)

Factors common to community initiatives that deliver effective community infrastructure

There is strong evidence that community infrastructure is a necessary but not sufficient factor for thriving communities, as it provides a place in/at which people can meet and, in some cases, it can be a focal point of the local area. For this infrastructure to support the community effectively, it needs to be utilised for purposes that facilitate community networks and interactions (i.e. to provide opportunities for bridging, bonding and linking groups of people), often led by activity organisers or community-based institutions.

Medium to strong evidence suggests that the factors common to community initiatives that deliver effective community infrastructure include:

- responsibility for the maintenance and operation of the infrastructure being designated to people with the right skills, including paid staff and volunteers (charismatic local leaders can play an important role in enabling success)

- responsibility for taking a longer-term view of the infrastructure being designated to an appropriately skilled and committed person. This includes developing and working towards the longer-term vision, securing funding/income streams, succession planning and working to ensure longevity of the community infrastructure (financially and as a focus for the community)

- accessibility, visibility, safety and inclusivity of the infrastructure itself and the activities within it

- local empowerment engendered through effective partnerships involving local partners and local authorities, and co-production of projects where feasible.

A summary of the evidence and its relative strength is given in the following table.

| Common factors for effective community infrastructure | Evidence rating | Scheme-specific factors for effective community infrastructure | Evidence rating |

|---|---|---|---|

| People with the necessary skills (including those paid to be responsible for the infrastructure and volunteers). | Strong | A lack of consideration of the time and resource commitment of projects | Limited |

| Charismatic leaders to create and drive forward a vision for community infrastructure, and to encourage interactions between different groups | Medium | Awareness of the opportunities at local infrastructure | Limited |

| Accessibility and location of infrastructure | Medium | Over-optimistic risk appraisal leading to initiatives being cancelled | Limited |

| Ability to generate income | Medium | The quality of data and analytical input | Limited |

| Stability and horizon of external funding such as grants, loans, and investments, which support initial investment and ongoing repair and maintenance | Medium | Professional marketing and an online presence to attract new users | Limited |

| Effectiveness of engagement with local community | Strong | New forms of ownership facilitating additional funding or better financial terms | Limited |

| Local government partnerships to support the delivery of projects | Strong | Cross-government department split of responsibilities resulting in an unclear policy framework | Limited |

| Local non-government partnerships to create new opportunities and receive advice | Medium | ||

| Utilised purposefully and over a sustained period to bring people from the community together | Medium | ||

| Legal, regulatory and administrative frameworks can appropriately empower local communities | Limited | ||

| External advice and advisory support to navigate complex matters such as technical regulation and processes | Limited | ||

| Strategic planning for the longer term, including appropriate targets and timeframes, and sustained funding or income | Medium | ||

| Professionalism and expertise of board members and paid staff | Strong | ||

| Continued investment in physical infrastructure | Limited |

Factors relevant to enhance social capital

Understanding the factors relevant to enhance social capital requires careful attention to the type of social capital. For example, factors which bolster only “bonding” social capital (interactions within_ groups or networks) could in some cases act as a barrier to “bridging” social capital (interactions across groups or networks) if they lead to non-inclusive behaviours or perceptions. It is important to establish and maintain awareness of opportunities to connect with other people locally, whether through social prescribing, local leaders, digital networks or by using venues for multiple purposes.

Medium to strong evidence suggests that the factors common to community initiatives that enhance social capital include:

- Community infrastructure which fosters social interactions between visitors and

- Community infrastructure which is inclusive.

A summary of the evidence and its relative strength is given below.

| Common factors for enhancing social capital | Evidence rating | Scheme-specific factors for enhancing social capital | Evidence rating |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community infrastructure which fosters social interactions between visitors | Strong | Subsidising the cost of using community infrastructure to boost participation | Limited |

| Appropriate choice of venue for a given activity to boost participation | Limited | ||

| Inclusivity of community infrastructure | Medium | ||

| Social prescribers can remove barriers which stop patients from participation | Limited | ||

| Designated managers can facilitate interactions between different members of the community | Limited |

Outcomes when community initiatives are effective

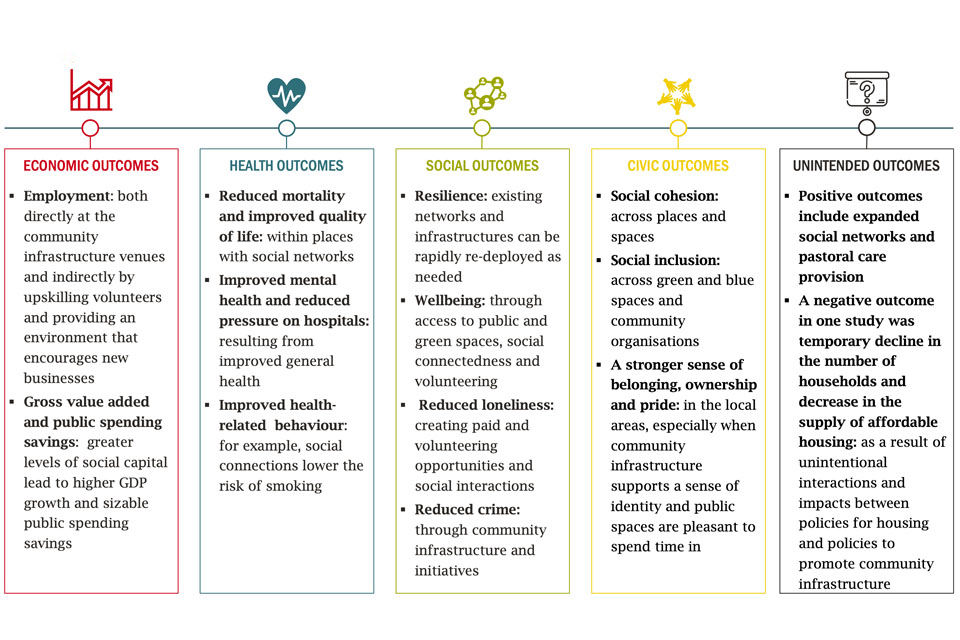

Where initiatives deliver effective community infrastructure and enhance social capital, there are a range of positive outcomes including economic, health, social and civic outcomes. There is medium evidence that likely outcomes include, from an economic perspective, employment opportunities, skills development, economic output (gross domestic product (GDP)) and, potentially, savings in public spending. Health outcomes can include improved mortality rates, improved health-related quality of life and health-related behaviour (such as reducing smoking). Social outcomes include community resilience, improved wellbeing and reduced loneliness and crime. Finally, civic outcomes include social cohesion, social inclusion and a greater sense of belonging, ownership and pride.

The potential outcomes are summarised below. Economic, health, social and civic outcomes have medium evidence, while there is limited evidence for some unintended outcomes.

State of the evidence and research priorities

The findings are highlighted in this rapid evidence review as a synthesis of existing evidence. They also identify where there are limitations and gaps in what is currently published. What is clear is that local context is important and that communities differ significantly, and therefore there is no one-size-fits-all approach. However, the evidence of these local contextual characteristics is currently lacking.

The most notable gap in the evidence relates to robust evaluation of the outcomes of community initiatives, and how the initiatives were selected, what local need they were meeting, how financially sustainable they were and, importantly, what would have happened without them. To address this, robust evidence which considers what would be expected without the community infrastructure intervention (i.e. the counterfactual) would help with understanding the extent to which outcomes can be attributed to the community initiative, and the particular conditions under which this is more likely.

Further research to address the gaps and limitations in the evidence identified in this rapid review would also be helpful. These include suggested priorities such as:

-

Placed-based evaluation to understand the local (and wider) impacts of community infrastructure, including process evaluation to enable learning about governance and funding structures.

-

Process evaluation to determine the actions and factors that enhance the financial sustainability of community infrastructure, including options for income generation.

-

Fieldwork to understand how community members in different groups experience community infrastructure (to understand the barriers and enablers of utilisation, and barriers and enablers of enhancing bonding and bridging social capital) and how best to enhance the inclusivity of community initiatives.

-

Process evaluation to understand the partnerships that bolster the effectiveness of the planning, delivery and operation of community infrastructure, with a particular focus on the roles that local authorities and central government could play.

-

Impact evaluation to understand the channels through which community infrastructure and social capital can deliver outcomes for the community and more widely, with a particular focus on economic, social and resilience outcomes.

1. Introduction

This chapter provides the context for this rapid evidence review and outlines the approach taken and the structure of this report.

1.1 Context

Levelling up is a core priority for the UK government. The recently published white paper Levelling Up the United Kingdom (HM Government, 2022), defines it as “…giving everyone the opportunity to flourish. It means people everywhere are living longer and more fulfilling lives, and benefitting from sustained rises in living standards and well-being” (HM Government, 2022, p1).

To drive towards these aims, several factors need to come together. These include six types of capital, as identified by HM Government (2022): physical capital, human capital, financial capital, social capital, intangible capital and institutional capital. Existing evidence suggests that where these forms of capital come together, including community infrastructure, which is an example of physical capital, there is a virtuous cycle such that positive outcomes increase the likelihood of further positive outcomes (HM Government, 2022).

A preliminary assessment of the available evidence revealed that the definitions of the particular factors that enable communities to thrive are not consistent across studies, especially in relation to community infrastructure and social capital. There is also much still to be understood about how community initiatives can deliver community infrastructure effectively and enhance social capital.

Government is therefore interested in understanding the state of the current evidence base on these issues and where there are gaps or limitations in what is currently known. To build this understanding, the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), and the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) jointly commissioned this study.

The objectives of this study are:

-

To explore the definitions and concepts of social infrastructure and social capital to help government determine how and when to use different terminology.

-

To understand the strength and breadth of the evidence base about what works to deliver successful community (including community-led) initiatives to improve local social infrastructure and social capital.

-

To understand what could be considered “success” in community-led infrastructure initiatives and how government can deliver value-for-money interventions in this space. This includes the outcomes that could be considered success and the inputs that determine success.

-

To understand the strength of evidence on these issues and identify gaps and how they could be filled.

1.2 Approach

A rapid evidence assessment (REA) was selected as the evidence review methodology, as the time available for this study was less than three months. This REA was undertaken in line with best-practice guidance published by the government (Collins et al., 2015).

The first decision was to define the scope of the work. Through collaboratively working on the scope with DCMS and DLUHC, it was agreed that, for the purposes of this evidence review, the direct provision of public services (such as health, education) would not be within scope. Infrastructure whose primary purpose is to deliver those public services but which is also used for another purpose as community infrastructure to bolster social capital would, however, be in scope.

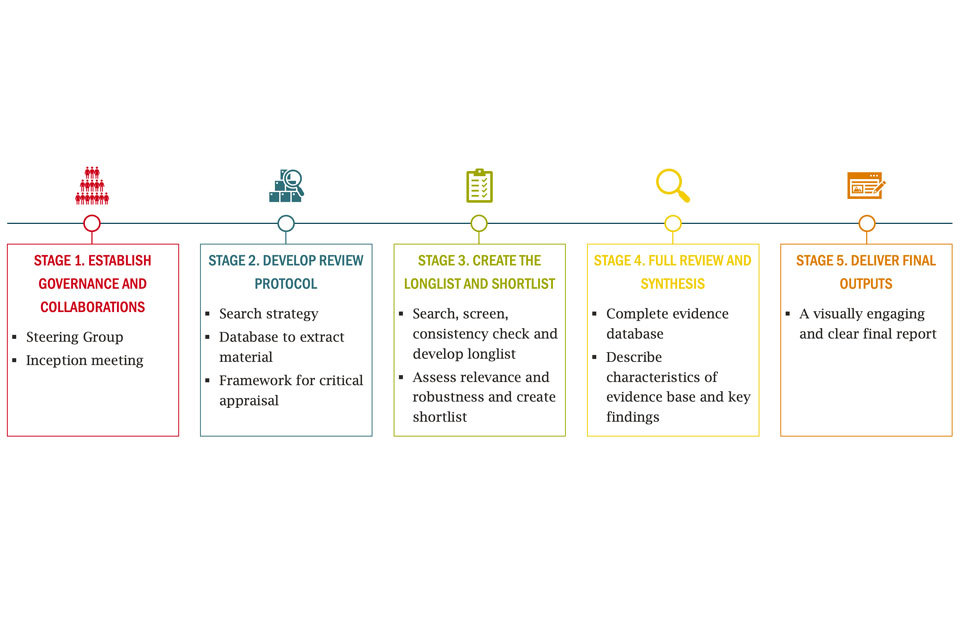

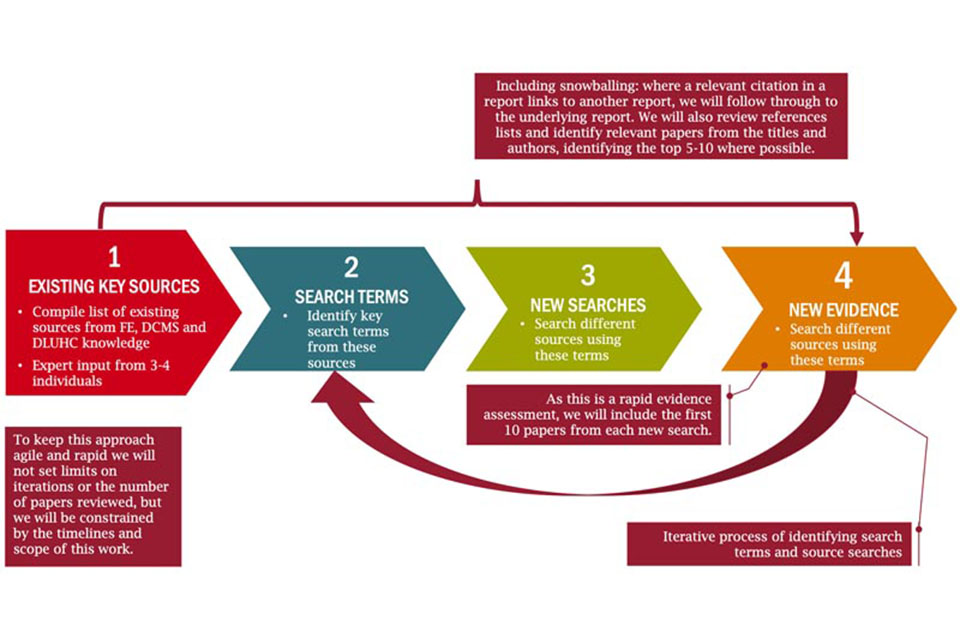

The stages of the approach are shown below.

Figure 2 Five-stage approach

Source: Frontier Economics

For stage 1 of this approach, the governance and collaborations were swiftly identified and a Steering Group comprising members from DCMS and DLUHC, which met (virtually) weekly, was set up. Stage 2 was undertaken over a period of three weeks and resulted in a review protocol that was discussed and agreed with the Steering Group. This was important as it confirmed the scope, approach and actions to fulfil the remaining stages of our approach.

For stage 3, the operationalisation of the search strategy recognised the fragmented nature of the evidence, and therefore involved two steps: firstly, talking to eminent academics and experts in this field to seek their guidance on navigating the evidence base; and, secondly, developing a longlist of search terms, and rapidly narrowing the search to the most relevant for this study.

Snowballing was applied to expand the search where appropriate. Further details are provided in Annex A.2.

A longlist of search terms, consistent with the aims of the rapid evidence review, was generated. The evidence base included academic literature from credible databases such as Google, Google Scholar and JSTOR, alongside grey literature including reports and documents published by DCMS, DLUHC and other organisations active in these areas, such as the Bennett Institute, Onward and Local Trust. No date range was set so as not to constrain the evidence, but most of the shortlisted papers are from the most recent 10-15 years. Older papers were included where the findings continue to be relevant and where a robust methodology had been used.

All longlisted documents were screened for their relevance, based on their abstracts and conclusions, and their robustness, based on the method adopted. More detail on how robustness, or “high-quality” evidence, was identified is described in the following section. Studies did not need to be of high quality to be included but it was important to understand both the quality and quantity of the evidence to assess the strength of the evidence base.

Stage 4 involved the detailed review of all shortlisted papers. These shortlisted papers are provided in the bibliography in Annex A.4. Stage 5 outputs were generated in the form of this report.

1.2.1 Assessing the strength of the evidence

The strength of the evidence was assessed on both on the quality of the research and the quantity of the research to identify where evidence for specific findings was strong, medium or limited. This was done in line with the Department for International Development’s (2014) “Assessing the Strength of Evidence” framework. Very strong evidence indicates both high quality and a large quantity; strong evidence indicates high quality and a medium to large quantity; medium evidence indicates moderate-quality evidence and a medium quantity; and limited evidence indicates moderate-to-low quality studies and a medium quantity. This is set out in the following table and the full framework is set out in Annex A.3.

Table 2

| Categories of evidence | Quality, size, consistency, context |

|---|---|

| Very strong | High-quality body of evidence, large in size, consistent and contextually relevant. |

| Strong | High-quality body of evidence, large or medium in size, highly or moderately consistent and contextually relevant |

| Medium | Moderate quality studies, medium-size evidence body, moderate level of consistency. Studies may or may not be contextually relevant |

| Limited | Moderate-to-low quality studies, medium-size evidence body, low levels of consistency. Studies may or may not be contextually relevant |

| No evidence | No/few studies exist |

Source: Department for International Development (2014), Assessing the Strength of Evidence, How to Note

Evidence ranged from being entirely theory based to vignettes and observations, to robust evaluation which sought to assess the outcomes of community-led interventions relative to what would have been anticipated absent the intervention. The quality of evidence was not straightforward to discern for every paper or had not been published. In such cases, a pragmatic and transparent approach was applied, indicating the extent to which the evidence can be considered credible. This was based on the method used in the study; the sample sizes used to generate evidence; the period over which evidence was collected; the extent to which outcomes assessed were considered relative to what would have happened without the intervention (or before implementation); and the extent of transparency in the approach, contextual factors and findings.

High-quality, robust quantitative evidence is studies that are able to meet at least level 3 on the Maryland Scientific Methods Scale (the recognised benchmark for evidence quality).

1.3 Structure of this report

The rest of the report is structured as follows:

- Chapter 2 focuses on the factors necessary for communities to thrive

- Chapter 3 defines community infrastructure and social capital

- Chapter 4 describes the factors needed to deliver effective community infrastructure

- Chapter 5 describes the factors needed along with community infrastructure to enhance social capital

- Chapter 6 presents the outcomes that effective community infrastructure and enhanced social capital can lead to

- Chapter 7 describes the overall state of the evidence and recommended research priorities to fill evidence gaps

- Chapter 8 concludes

The annexes provide a glossary of commonly used terms, details on the review protocol, the strength of evidence framework and a bibliography for all shortlisted papers reviewed in detail for this work.

2. Factors necessary for thriving communities

This chapter explores what the evidence says about the factors that are common to thriving communities. The outcomes that could emerge are considered in chapter 6.

Key findings from this chapter are summarised in the box below.

Summary

- For communities to thrive and unlock their potential, there is strong evidence that many factors need to work together simultaneously (e.g. Slocock, 2018).

- If any factor is missing or inadequate, this can constrain a community’s economic and social potential, and its resilience.

2.1 What do we mean by thriving communities?

To thrive means to grow and be successful: to prosper and to flourish.[footnote 2] In the context of communities, where they are considered to be thriving, one would expect to observe a number of outcomes. These could relate to economic outcomes (such as employment, skills, innovation); social outcomes (such as wellbeing); health outcomes (such as mortality) or civic outcomes (such as social cohesion) (What Works Centre for Wellbeing and Happy City, 2019).

Thriving communities are also likely to be resilient communities (South et al., 2018; The British Academy, 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of resilience in communities to deal with challenges and unexpected change and has brought attention to the role that community infrastructure plays in bringing people together (Kelsey, 2021; Wilson et al., 2020).

The evidence on these outcomes, including community resilience, is discussed in chapter 6. The rest of this chapter considers the factors that create the conditions for communities to thrive.

2.2 Factors that together unlock thriving communities

Strong evidence demonstrates that, for communities to thrive and unlock their potential, there are many factors that need to work together simultaneously (Slocock, 2018). Where one or more factors fall short, this could hold back the community’s potential. This suggests that for a community to thrive, a holistic community-wide perspective is needed.

Figure 3: Factors for thriving communities

Source: Frontier Economics; six capitals framework from Levelling Up the United Kingdom, HM Government (2022)

Factors that need to come together include the six types of capital identified in the Levelling Up White Paper (HM Government, 2022). These are not the only factors but they are commonly identified across the literature. Figure 3 shows how these types of capital are centred around people: people are at the heart of a thriving community. However, exactly what the people in the community care about and need is likely to differ across areas and communities, so what works for one community may not work for another. Context-specific factors are therefore vital to consider.

For the types of capital to be effective in unlocking people’s potential to build thriving communities, there are certain characteristics that need to be present. Commonly referenced characteristics include:

- Shared norms and values (Coyle et al., 2019);

- Public services which support people, aligned to the capitals of the community (Sinclair, 2019);

- Time offered by volunteers (MacMillan, 2020);

- A long-term viewpoint so that the community is sustained (Gregory, 2018);

- Continued accessibility of places and spaces (Tulloch, 2016); and

- Inclusivity (Yarker, 2019).

For instance, there is medium evidence showing that shared priorities and norms are important for unifying communities. An example of this is the response to COVID-19 in which a single issue can unify many groups (Frontier Economics et al., 2020; McCabe et al., 2021; Wilson et al., 2020).

The evidence base uses different terminology for the forms of capital and their characteristics which help communities to thrive. Figure 3 and the above list are intended to provide a general synthesis of the evidence base.

All the factors shown in Figure 3 and listed above interact (Slocock, 2018). Therefore, a lack of one or more of these factors could cause a “vicious spiral” such that outcomes that once benefitted the community gradually start to dissipate, whereas sufficient presence of all factors can cause a “cycle of strength” (HM Government, 2022). Furthermore, the factors need to be sustained over time to facilitate longevity in community outcomes. A challenge often referred to in the evidence is that of inadequate financial capital brought about through funding cuts, for example. Such declines in funding can lead to degradation of physical capital (CRESR, 2010; Mayor of London, 2020; Morrison et al., 2020b) and a decrease in voluntary sector infrastructure (McCabe et al., 2021). In such cases, the likelihood of a vicious spiral increases.

Of the types of capital shown in Figure 3 and listed above, DCMS and DLUHC have a particular interest in understanding how community initiatives can best deliver community infrastructure and enhance social capital. These are discussed in more detail in the next chapters.

3. Defining community infrastructure and social capital

Chapter 2 demonstrated that community infrastructure and social capital are necessary for thriving communities. These are not the only factors needed but this report focuses on these two aspects.

This chapter focuses on what the evidence suggests are appropriate definitions for community infrastructure and social capital.

The glossary in Annex A.1 identifies other terms which are common in the literature.

Findings from this chapter are summarised in the box below.

Summary

- The definitions of social infrastructure and social capital vary across the evidence base.

- There is strong evidence that, for community infrastructure to support the community effectively, it needs to be utilised for purposes that facilitate community networks and interactions (i.e. to provide opportunities for bridging, bonding and linking groups of people in communities) (South et al., 2021), often led by activity organisers or community-based institutions that host and provide interaction opportunities.

- Some definitions of social infrastructure refer only to the physical capital characteristic of community infrastructure (places, spaces and facilities), whereas others also include the occupants or activity organisers who utilise those places and spaces.

- What is clear is that both aspects are necessary to enable social capital formation. What is of importance is transparency over what is being referred to when. For the purposes of this review the term “community infrastructure” is therefore used as it refers to a narrower focus and is defined in this chapter.

- The definitions of social capital tend to be less diverse in the evidence and a commonly cited definition is from Putnam (1995).

- Community infrastructure is a necessary but not sufficient condition for social capital.

3.1 Defining community infrastructure

There are many definitions used in published evidence relating to the concept of social infrastructure, with some specific examples set out in the following section. This rapid review therefore adopts a specific definition for community infrastructure which is more narrowly defined and with a clear focus.

Some definitions of social infrastructure refer only to the physical capital characteristic (places, spaces and facilities), whereas others also include the occupants or activity organisers who utilise those places and spaces. What is clear is that both aspects are necessary to enable social capital formation.

Additionally, some definitions of social infrastructure include public services but this is not consistent across the evidence base. For instance, public services such as health provision and education are excluded by Frontier Economics (2021) while Mayor of London (2020) analysis includes these public services.

Public services per se are excluded from the definition of community infrastructure in this review because public services have much broader objectives than enhancing social capital. For instance, a school’s main objective is to deliver appropriate education for children and therefore, although parents, carers and others may meet in the process of taking children to and from school, those meetings would be opportunistic. However, if the school were to use its infrastructure to offer services that bring people together (such as hosting dance classes) then, in this sense, the school could be considered community infrastructure.

For the purposes of this review, community infrastructure is defined[footnote 3] as the physical infrastructure within the community (including places, spaces and facilities) that supports the formation and development of social networks and relationships, either:

-

Directly: through how the physical infrastructure is purposefully used for bringing people together (for example, a green space or building where people and groups can meet for the purpose of participating in activities with other people from the community); or

-

Indirectly: by providing the infrastructure to enable individuals within a community to connect together. This includes physical connections (such as transport links) or complementary virtual connections (such as communication or digital technology that supports the physical meeting of people).

Typical examples of community infrastructure include sports facilities, libraries, some eating establishments, some places of worship (for example, if they have a community hall), gardens and parks. Some community infrastructure can be purpose built or can be a re-deployment of infrastructure delivered for another purpose. Some examples of community infrastructure are given below. This is not an exhaustive list but is intended to illustrate some of the different uses of community infrastructure.

The evidence suggests that core to identifying whether infrastructure is “community infrastructure” is how it is used (for example, Sinclair, 2019; Slocock, 2018). Section 3.1.2 discusses different examples. A common aspect of community infrastructure found across the literature is that it is often used for more than one purpose (for example, Archer et al., 2019; Henderson et al., 2018; Parsfield, 2015; What Works Centre for Wellbeing, 2018; South et al., 2021).

3.1.1 Example definitions from the literature

Definitions of social infrastructure vary across evidence sources. Below are a few example definitions taken directly from the literature:

The physical spaces and community facilities which bring people together to build meaningful relationships.

– (Kelsey and Kenny, 2021)

A range of services and facilities that meet local and strategic needs and contribute towards a good quality of life, facilitating new and supporting existing relationships, encouraging participation and civic action, overcoming barriers and mitigating inequalities, and together contributing to resilient communities.

– (Mayor of London, 2020)

…refers to the range of activities, organisations and facilities supporting the formation, development and maintenance of social relationships in a community… Places can be civic; religious; traditional; digital; private; public; outdoors; routes; occasions; associations.

– (Gregory, 2018)

3.1.2 Types of community infrastructure

There are various forms of community infrastructure that have been implemented across the UK. These include, but are not limited to, sports and fitness facilities, libraries, gardens and parks, cafes, shops, food co-operatives, pubs and youth or social clubs. The list below explores in greater detail common examples from the evidence.

Sports and fitness facilities

Sports and fitness facilities can serve as community infrastructure because sports participation can bring people together, leading to the formation of social networks and therefore enhancing social capital (Davies et al., 2020). To function as community infrastructure, activities need to exist within the facilities that provide an opportunity for members of the community to interact and form networks, perhaps through group classes, team sports and/or other spaces for people to interact; people going to the gym by themselves without interacting with others may not lead to the same outcomes (Fujiwara et al., 2014).

Libraries

Libraries can also act as a space to bring people together by promoting social mixing within, and across, different groups in local communities. This particularly occurs when classes are used to bring people together and where libraries can be used as facilities similar to a youth club (BOP Consulting, 2014).

Gardens and parks

Green spaces such as public parks and community gardens can be used to bring people together and, when used in this way, they function as community infrastructure. The main purpose of a public park is to provide free access to informal recreation and enjoyment, and it can facilitate people meeting and building connections. This definition includes urban parks, country parks, gardens, squares and seaside promenade gardens (Heritage Fund, 2020). Urban green spaces refer to publicly accessible vegetated land connected to built-up areas that may vary in size, vegetation cover, species richness, environmental quality, proximity to public transport, facilities and services (Heritage Fund, 2020). Community gardens differ from allotment gardens because they are created and managed by the community itself (Hancock, 2001).

Community infrastructure that acts as a multi-use gathering space to serve the community and bring people together is often referred to as a community hub. There is no single type of community hub: they take a variety of forms and include different components. Some community hubs are standalone buildings, and some are part of other buildings including schools (Singh and Woodrow, 2010). For example, a sports or fitness facility that includes additional spaces for people to interact can fall under the umbrella term community hub. Similarly, libraries that offer classes in addition to their primary purpose of lending books and encouraging reading can also be considered community hubs.

3.2 Defining social capital

Social capital is a core factor (shown in Figure 1) for thriving communities.

Although various definitions of social capital are used in the literature, the Putnam (1995) definition is common to most sources. According to Putnam (1995), social capital contains “…features of social organisation such as networks, norms, and social trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit”(Putnam, 1995). The wider evidence supports this definition and suggests at least three common features of social capital, which are social networks, norms and trust, and personal relationships (Coyle et al., 2019; ONS, 2020; Putnam, 1995; Yarker, 2019).

Trust is discussed in different ways in different studies. For example, some studies suggest that it is a requirement for the formation of social capital and others suggest that it is an outcome of social capital (Woolcock, 2001) . Some studies also suggests that trust can be self-reinforcing over time (Coyle et al., 2019). This highlights the complexity of the issues considered in the rapid evidence review.

Other definitions used in the literature are offered in the next section.

The evidence shows that social capital is not just a single concept. The evidence identifies the following three forms of social capital:

-

Bonding social capital, which refers to relationships between homogeneous groups within a closed network (Putnam, 1995), for example relationships between family members and close friends (Bertotti et al., 2011).

-

Bridging social capital, which refers to relationships between heterogeneous groups within an open network (Putnam, 1995) (for example, relationships between groups of people with different ethnic or occupational backgrounds) (Bertotti et al., 2011).

-

Linking social capital, which refers to relationships between individuals within a community and individuals in a position of power (such as local authorities) to leverage resources, ideas and information (Bertotti et al., 2011 Woolcock, 2001). It is different to bridging social capital because it specifically links to those in positions of responsibility.

3.2.1 Example definitions of social capital from the literature

Other definitions of social capital identified in the literature are given below:

Social capital is often referred to as the glue that holds societies together. It encompasses personal relationships, civic engagements and social networks. Social capital relates to generalised trust, shared rules, and the social norms and values that shape the ways we behave in everyday relationships and transactions.

– (Coyle et al., 2019)

Social capital is measured through the areas of our personal relationships, social network support, civic engagement, and trust and cooperative norms. It is a term used to describe the extent and nature of our connections with others and the collective attitudes and behaviours between people that support a well-functioning, close-knit society.

– (ONS, 2020)

Social capital refers to the productive benefits of social relations (i.e., social networks, relationships, norms and values). At the individual level it refers to trust in people and personal involvement in other people’s activities.

– (Roskruge et al., 2010)

Social capital is defined as the potential embedded in social relationships that enable residents to coordinate community action to achieve shared goals.

– (Semenza and March, 2009)

Social capital is the sum of potential or actual resources which are embedded in a social network or structure.

– (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998)

Social capital is the strength of communities, relationships and trust.

– (HM Government, 2022)

3.3 How and when to use community infrastructure and social capital

A key feature of community infrastructure which emerges from the evidence is that it is physical infrastructure which supports the formation and development of social networks and relationships because of how it is used, for example where it is used by organisations or institutions that provide opportunities for people to meet and form networks, organisations and activities (for example, Aldrich and Meyer, 2014; Fujiwara et al., 2014; Mayor of London, 2020). This differentiates community infrastructure from other forms of physical infrastructure where social interaction is unlikely to take place.

Definitions of social infrastructure can be much broader and include public services like health and education. And social infrastructure can refer to the organisers of activities that bring people in a community together.

As discussed in section 3.2, social capital is intangible and generally characterised by trust, social networks and personal relationships. This can then lead to other outcomes and needs to be maintained over time.

Other terms commonly found in the literature and frequently cited initiatives and studies are given in the glossary in Annex A.1. This includes terms such as “social anchor” which are similar but different to community infrastructure, to provide clarity on when which term is appropriate.

4. Delivering community infrastructure

Chapter 2 demonstrated that well-utilised community infrastructure provides the opportunity to build and maintain the social networks and relationships that form social capital. Although other factors are also important for social capital to be enhanced over time, this chapter focuses on community infrastructure and explores what the evidence reveals about how it can most effectively be delivered through community initiatives. Evidence from both a system-wide perspective and scheme-specific perspective is discussed, taking account of:

- The types of community infrastructure;

- Funding models for community infrastructure; and

- Governance, management and ownership models for community infrastructure.

Chapter 5 focuses on social capital and synthesises the evidence on how it can most effectively be enhanced through community initiatives. Chapter 6 then summarises the evidence on the potential outcomes when community infrastructure is effectively delivered and social capital is enhanced.

Summary

| Common factors for effective community infrastructure | Evidence rating | Scheme-specific factors for effective community infrastructure | Evidence rating |

|---|---|---|---|

| People with the necessary skills (including those paid to be responsible for the infrastructure and volunteers) | Strong | A lack of consideration of the time and resource commitment of projects | Limited |

| Charismatic leaders to create and drive forward a vision for community infrastructure, and to encourage interactions between different groups | Medium | Awareness of the opportunities at local infrastructure | Limited |

| Accessibility and location of infrastructure | Medium | Over-optimistic risk appraisal leading to initiatives being cancelled | Limited |

| Ability to generate income | Medium | The quality of data and analytical input | Limited |

| Stability and horizon of external funding such as grants, loans, and investments, which support initial investment and ongoing repair and maintenance | Medium | Professional marketing and an online presence to attract new users | Limited |

| Effectiveness of engagement with local community | Strong | New forms of ownership facilitating additional funding or better financial terms | Limited |

| Local government partnerships to support the delivery of projects | Strong | Cross-government department split of responsibilities resulting in an unclear policy framework | Limited |

| Local non-government partnerships to create new opportunities and receive advice | Medium | ||

| Utilised purposefully and over a sustained period to bring people from the community together | Medium | ||

| Legal, regulatory and administrative frameworks can appropriately empower local communities | Limited | ||

| External advice and advisory support to navigate complex matters such as technical regulation and processes | Limited | ||

| Strategic planning for the longer term, including appropriate targets and timeframes, and sustained funding or income | Medium | ||

| Professionalism and expertise of board members and paid staff | Strong | ||

| Investment in physical infrastructure | Limited |

4.1 Types of funding models

There are different models and policy levers that can deliver community infrastructure. These can be community led, led by local government, and/or involve central government. Funding models include, but are not limited to, community levies, central government funding, crowd-source funding, community business funds, social investment, local government funding and community shares.

The list below explores some of the funding models for delivering community infrastructure that appear more commonly across sources:

Community levies: the Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) – a charge which could be levied by local authorities on new developments in their area to collect developer contributions, the distribution of which could then fund community infrastructure (DCLG (now DLUHC), 2017).

Central government funding: several examples of central government funding of programmes in communities include the Communities Fund, the New Deal for Communities and Whole-Place Community Budgets. Details of these are provided in the glossary in Annex A.1. Central government funding can take a variety of forms. For example, a programme to support community pubs provided funding through a combination of loans and grants (Plunkett Foundation, 2020a).

Crowd-source funding: crowdfunding refers to the funding of projects and business ideas through many small contributions from the public and from businesses (Crowdfund London, 2019). This funding mechanism has been used for community-led projects which include community infrastructure. It can help local project creators reach out to local businesses and companies to garner further support (Exeter City Futures, 2018).

Community business funds: these are made available by the third sector to offer to community businesses with the aim of enhancing their growth, sustainability and effectiveness (Renaisi, 2019). Community business funds can take a variety of forms such as loans, grants, equity, matched funding programmes and capital grants. Examples include Local Trust’s Big Local, the Mixed Communities Initiative, the South Yorkshire Social Infrastructure Programme (SYSIP) and the Community Business Renewal Fund by Power to Change. Details of these are provided in the glossary in Annex A.1.

Social investment: refers to a loan or other forms of repayable finance to help community organisations make a positive economic, social or environmental impact in a community, as well as earning income (Local Trust, 2015).

Community shares: these are a funding model via which community members buy shares in enterprises that meet their needs and are managed by the community they serve (McCulloch and Wharton, 2020).

The evidence on the factors relevant for delivering effective community infrastructure in section 4.5 draws on these examples of funding models for community infrastructure.

4.2 Types of governance, management and ownership models

The evidence suggests that there are different governance, management and ownership models that can be associated with the delivery of community infrastructure. These include, but are not limited to, community asset ownership, social enterprises, co-operatives, development trusts, community land trusts and community businesses.

The list below explores some of the types of governance, management and ownership models that appear more prominently across the evidence in the context of delivering community infrastructure:

- Community asset ownership: where the long-term ownership rights for large physical infrastructure are held by community or voluntary organisations (such as a development trust, a community interest company or a social enterprise) which operate in the interest of the local community and include local residents in the decision-making body (Archer et al., 2019). The transfer of management and/or ownership of the assets from its owner to a community or voluntary organisation occurs for less than market value to achieve a local social, economic or environmental benefit (Locality, 2018).

- Social enterprises: business organisations working with a social mission or in the interest of the community (Locality, 2018). They give high priority to local residents and businesses in the management of the enterprises and delivery of projects (Bailey et al., 2018). These can include community cafes, pubs, shops and youth or social clubs.

- Co-operatives: made up of an association of people who together form an organisation known as a co-operative. The organisation is jointly owned and democratically operated. Community co-operatives can focus on a range of initiatives, including food (BMG Research, 2012).

- Development trusts: third-sector organisations set up to enable the involvement of the community in the management of community infrastructure (Pill, 2013).

- Community land trusts: vehicles for local ownership and control of housing (Archer et al., 2019).

- Community businesses: these are united by being locally rooted, serving a common need and being accountable to their community (Richards et al., 2018a).

The evidence on the factors relevant for delivering effective community infrastructure in section 4.5 draws on these examples of governance, management and ownership models for community infrastructure.

4.3 Trends in community infrastructure

Community infrastructure exists in some form in all communities across the UK. It exists in different forms and is highly variable in terms of type, capacity and condition. In recent years, there has been a decrease in funding for, and closure of, civic institutions and community spaces, including libraries. Over a quarter of pubs have closed since 2001, and over a quarter of libraries have closed since 2005 (O’Shaughnessy et al., 2020). However, in recent years there has been an increase in the number of certain types of community infrastructure, as exemplified by community pubs (which increased more than tenfold between 1996 and 2019 (Plunkett Foundation, 2020a)) and community asset ownership (which has seen a marked increase over the last ten years, mostly been driven by non-community hub/hall/centre assets (Archer et al., 2019)).

Although little evidence is currently available on the formation and facilitating factors for digital communities, [footnote 4] there is an emerging trend for utilising digital communications to enhance connections that take place physically (The British Academy, 2021).

4.4 Factors common to community initiatives that deliver effective community infrastructure: system-wide

The evidence identifies several factors that are important in the context of delivering community infrastructure. Where such factors are common across many different forms of community initiatives, they are discussed below as “system-wide” factors. Where the factors appear to emerge in the evidence as being relevant for specific initiatives or contexts only, they are discussed below as “intervention-specific” factors.

4.4.1 Volunteers

There is strong evidence that volunteers are an enabler of delivering effective community infrastructure (South et al., 2021). The evidence suggests this is true for different types of community infrastructure, different funding mechanisms and different governance models, as explained further below.

The evidence suggests that volunteers are critical for the planning, delivery and operation of many community infrastructure projects across the country (for example, Kotecha et al., 2017; Plunkett Foundation, 2020a; Taylor, 2017). This is the case across many forms of community infrastructure, including places of worship (Taylor, 2017), community pubs (Plunkett Foundation, 2020a), and community sports and leisure community businesses (Richards et al., 2018b).

The value that volunteers provide to community infrastructure takes various forms. They can, for example, support local businesses by working as substitutes for paid staff, as has been the case in several sports and leisure businesses, for example. In one case, the business invested in its volunteers, leading to stronger community engagement and volunteers who are incentivised and want the business to succeed (Richards et al., 2018b).

Volunteers can also support the financial sustainability of effective community infrastructure in other ways. For example, certain types of community infrastructure may require workers with specialist skills which would be expensive if hired from the market. If volunteers with these skills are available, this can considerably reduce costs. For example, the use of volunteer drivers has significantly reduced labour costs in the context of community transport organisations (Kotecha et al., 2017).

Although volunteers can support effective community infrastructure, a lack of volunteers with the required skills can conversely be a constraint (South et al., 2021). A lack of volunteers with the necessary skills has been identified as a barrier for some places of worship, some community hubs (South et al., 2021) and some community transport organisations. A review of English churches and cathedrals illustrated that many areas had limited skilled assistance to support volunteers in sustaining the place of worship with appropriate maintenance and repair and helping communities to make best use of their buildings (Taylor, 2017). With community transport organisations, the combined challenge of finding volunteers and staff with the required skills was among the top barriers to success and growth for their businesses (Kotecha et al., 2017). Furthermore, reliance on volunteers can create challenges where particular time commitments and reliability are required due to the competing priorities facing volunteers in their home or work life (Frontier Economics et al., 2020; South et al., 2021).

Volunteers have enabled many types of effective community infrastructure. Examples include:

- A youth house in Stockholm, Fryshuset, which was successful in mobilising voluntary resources because it was perceived as the volunteers’ own organisation (Westlund and Gawell, 2012);

- A community café located within an estate in southwest London which contributed to building bridging social capital through the employment of volunteers (Bertotti et al., 2011);

- Community-led libraries, which benefit from ongoing or targeted support from local authorities via access to local volunteer networks (SERIO, 2017); and

- Community pubs, which volunteers supported with both day-to-day running and “behind the scenes” help (Plunkett Foundation, 2020a).

Volunteers have emerged as a key success factor in the management of co-operatives. The Community Food Co-operative in Wales was funded by the Welsh government and run by volunteers, and for which, on average, over 1,400 people volunteered each week across the nation (BMG Research, 2012). The Food Co-ops and Buying Group project also highlighted the importance of well-trained volunteers and of establishing mechanisms which incentivise their participation (Smith et al., 2012). However, in certain instances, over-reliance on volunteers can pose critical issues for the longer-term sustainability of co-operatives (Smith et al., 2012). For example, the community co-operatives of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland experienced challenges because ageing local populations made it difficult to access volunteers (Gordon, 2002). Although this evidence is 20 years old, it has been included for its focus on community co-operatives and this remains a live issue.

Other governance models reliant on volunteers are community benefit societies and community-owned assets. Examples include:

- The Incredible Edible model, a community benefit society in West Yorkshire, used public spaces to grow food for anyone to enjoy. The aim was to enrich communities via access to healthy and sustainable locally grown food while spending time in green spaces. However, it was hard to retain volunteers for long-term sustainability (Morley et al., 2017); and

- A review of community-owned assets found that many CAT 1 projects required a sufficient volume of volunteers (CMI and Rocket Science, 2016).

Case study – Volunteers within a community organising programme

In Wick, Littlehampton, a cabinet-funded community organisers’ programme successfully networked with a newly invigorated Tenants and Residents Association (TRA) on the main social housing estate in the area. The volunteers recruited from the community organising programme, members of the TRA and several well-connected people prominent in the Connected Communities social networks formed a successful network which undertook a wide range of successful interventions and initiatives to improve wellbeing and connection in the local area (Parsfield, 2015).

4.4.2 Charismatic leaders

There is medium evidence that charismatic leaders are a factor for effective community infrastructure, for example by bringing different groups in the community together (Bertotti et al., 2011; Gordon, 2002) and by generating and delivering on the vision for the infrastructure itself (Morley et al., 2017).

Charismatic leaders were involved in bringing different groups in the community together at community co-operatives in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland (Gordon, 2002) and at a community café in London (Bertotti et al., 2011), which is discussed in more detail below.

Case study – Charismatic leader at a café

A community café located within an estate in southwest London benefitted from the dynamism and commitment of the manager, who provided a role model for some people. Although at a small scale, the manager was able to create a better balance between bonding and bridging social capital by brokering relationships between different segments of the community. This individual showed dynamism and an in-depth understanding of the experience of local residents, which facilitated the establishment of networks across ethnic groups (Bertotti et al., 2011).

Charismatic leaders can support community infrastructure by generating and delivering on the vision for the infrastructure itself. For example, a community benefit society in West Yorkshire which uses locally grown food to enrich communities was founded by two charismatic local leaders who effectively engaged local people (Morley et al., 2017). In this case, the community benefit society was highly effective, as it was perceived to have supported a transformation of Todmorden, the local town, both economically and by “improving everyday living environments” (Morley et al., 2017).

4.4.3 Accessibility and location

There is medium evidence that the location and accessibility of community infrastructure are important for its effectiveness.

Accessibility emerged as a contributor to the effectiveness of community pubs and community hubs. Community pubs aim to be accessible because they are open to the whole community and they are also open for long hours (Plunkett Foundation, 2020a). Community hubs are more effective when they are accessible to different groups in local communities. This was a particular consideration for the School-Centred Community Hubs programme which was established by the Stronger Families Alliance in disadvantaged areas of the Blue Mountains in New South Wales (Australia). The evaluation of this programme highlighted that, for engagement across the community, it was important to minimise access barriers specifically for vulnerable and marginalised families (Singh and Woodrow, 2010).

The location of community infrastructure can also play an important role in its success. The success of two community hubs in southwest Ontario, for example, was facilitated by their co-location with community partners (Ricardo Ramirez Communication Consulting, 2017). In addition, facilities which are easy to get to were identified as a driver of facility usage in the context of sports facilities in Scotland (Ekos, 2019). It follows therefore that an inconvenient location can hinder the effectiveness of community infrastructure as some people may not be able to get to it. A community hub in Lawrence Weston, Bristol, for example, was not easily accessible for the elderly as it was located on a hill (Sanders, 2018).

4.4.4 Income generation

There is medium evidence that income generation is an important factor for the sustainability of effective community infrastructure.

Community infrastructure can generate income by making the most of revenue opportunities, for example, by renting out space within the venue. Townhill Park Community Centre in Southampton, for example, rents rooms and office space back to the city council to generate income (Gregory, 2018). Community pubs can offer meetings rooms for external hire, and this can provide an additional source of income to boost financial sustainability (Plunkett Foundation, 2020a).

Where income generation is not possible, or opportunities have not been investigated, this could add to the financial strain of repair, maintenance and operation of some types of community infrastructure. Examples include:

- Community-led libraries, many of which do not offer services which can generate revenue (SERIO, 2017); and

- Publicly owned physical assets used as community infrastructure (such as village halls), which can struggle when they are not used enough to generate income to cover ongoing costs (Locality, 2018).

Different funding models can also face financial sustainability challenges, especially where they only consider upfront investment costs for delivery and not ongoing operation. For example, the New Deal for Communities programme, an initiative funded by central government, was limited by a lack of income generation. The programme was an area-based initiative in 39 deprived neighbourhoods in England. An evaluation highlighted difficulties in maintaining full occupancy rates in new housing developments and rental income was not sufficient to maintain the same scale of activity (Batty et al., 2010).

Crowd-source funding is a funding mechanism which in some cases has been negatively impacted by lack of consideration of income generation. An evaluation of a crowdfund pilot in Exeter found that many community-based project ideas were hindered by limited consideration of long-term financial sustainability once the initial delivery funds were used up (Exeter City Futures, 2018).

Some governance structures, such as development trusts and social enterprises, many of which have benefitted from commercial activity to obtain revenue, appear to have a greater aptitude for income generation, in some cases. The Millfields Community Economic Development Trust, for example, was set up for people to manage the regeneration of the Stonehouse neighbourhood in Plymouth (Locality, 2018). The Trust generated income by developing sites for commercial premises, with a particular focus on small and medium-sized enterprises. It supported tenants by offering high-quality, affordable accommodation and flexible tenancy terms (Locality, 2018). Similarly, community-based social enterprises can be effective if, for example, they utilise a hybrid business model which combines trading and non-trading activities to achieve financial sustainability in the long term (Bailey et al., 2018).

4.4.5 External funding

There is medium evidence that external funding is an important factor for the operation and sustainability of different types of community infrastructure.

External funding can be available in multiple forms, such as loans, grants and direct investment. Examples of different types of community infrastructure which the evidence suggests have been able to benefit from external funding include:

- sports facilities in Scotland, where initial investment from the national sports body led to further investment from other sources, meaning that the initial central investment acted as a catalyst (Ekos, 2019)

- youth centres and clubs, which are often reliant on unstable funding, have proven to be effective when they successfully bid for new grants and contracts (Sinclair, 2019)

Community pubs, which have experienced an upward trend across the UK in recent years (Plunkett Foundation, 2020a) often because they have made use of a programme of blended finance (e.g. a combination of loans and grants) alongside advisory support from multiple organisations and some have been funded by the Power to Change Trust and the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (Plunkett Foundation, 2020a); and

The success of Mixed Communities Initiatives, which was enabled by attracting funding from other public sector streams, such as the New Deal for Communities, Urban Development Corporations or Regional Development Agencies (Lupton et al., 2010).

Development trusts can be effective in accessing external funding, especially from a blend of sources. For example, a development trust in northern England benefitted from schemes such as the Big Local (Locality, 2018). Heeley Development Trust was established to reclaim land for community use and create the Heeley People’s Park in Sheffield. The programme was funded via donations from the local community and local businesses as well as external funding, including from the Big Lottery Fund (Locality, 2018). For development trusts, commercial activities can be an important enabler of financial sustainability if paired with strong community involvement (Locality, 2018).

External funding has been an issue for community-owned assets because many of them have faced financial problems due to reductions in grants, which often reflect wider financial challenges in local government from cuts in central government funding (Archer et al., 2019). An example of this is The Rotunda in Liverpool, which is a community hub offering educational and training programmes. It relies on European funding which may be affected by Brexit and hence has created uncertainty about its financial sustainability (Archer et al., 2019). Furthermore, a survey of those responsible for assets in community ownership found that 20% were likely to have insufficient reserves to meet a modest unexpected expense or income shock (Archer et al., 2019). In addition, a significant number of this group of assets are also likely to be operating at a loss, while around a quarter of those surveyed said that their asset’s debt was not under control due to the move towards loan funding (Archer et al., 2019).

4.4.6 Effective engagement with the local community

There is strong evidence that engagement with the local community supports effective community infrastructure, and this was found in the context of a crowdfunding pilot and sports centres as examples. Community engagement and co-production (i.e. engaging with local stakeholders as equal partners) was also identified as important in several case studies in the context of community hubs (South et al, 2021)

Exeter City Futures piloted its #EveryonesExeter movement on the crowdfunding platform Spacehive. Through this pilot, it sought to test and evaluate crowdfunding as a tool for engaging communities, changemakers and businesses in the city change process. The initiative highlighted the benefit of sharing and showing inspirational examples of projects elsewhere to incentivise communities to consider implementing a similar project in their local area (Exeter City Futures, 2018).

Case study – Sports centres in Sligo, Republic of Ireland

Networking and collaboration with community representatives can be critical to the effectiveness of sports centres (Sligo Sport and Recreation Partnership, 2018). The Sligo East City Community Sports Hub, based on the Cranmore Estate in Ireland, engaged in networking and collaboration with community representatives, community organisation workers and representatives from various agencies (Sligo Sport and Recreation Partnership, 2018). These relationships appear to have been central to the willingness of community representatives to invest in and vouch for the Community Sports Hub development. They gained the trust of the community by increasing their awareness of the community needs and opportunities, as well as employing a creative approach to the needs and the capabilities of the various community and agency actors. New external networks were also created with communities and clubs adjacent to the Cranmore area in Ireland. This networking and trust building supported collaboration within the Cranmore community and nearby communities, clubs and recreational resources and thereby reduced some of the subtle, hidden barriers around the Cranmore community (Sligo Sport and Recreation Partnership, 2018).

4.4.7 Local government partnerships

There is strong evidence that partnerships with local government, such as local authorities, can play an important role in the delivery and operation of community infrastructure.

Local authorities have enabled community-led libraries through helpful support. Case studies of nine community-led libraries across England suggest that they benefitted from ongoing or targeted support from local authorities beyond direct funding, and from informal advice, access to local volunteer networks and training sessions (SERIO, 2017). These case studies highlight that local authority support has enabled community libraries to consolidate their volunteer base, safeguard effective service delivery and, in some cases, develop new or improved income-generating services, resulting in financial sustainability (SERIO, 2017).

The Communities Fund and New Deal for Communities are two central government-funded initiatives which have also been enabled by effective partnerships with local authorities. An evaluation of the Communities Fund highlighted that partnerships based on pre-existing relationships offered efficiencies and allowed projects to mobilise quickly (MHCLG (now DLUHC), 2021). Another example is the New Deal for Communities, a regeneration programme launched in 1998. An evaluation showed that between 2002 and 2008, New Deal for Communities areas saw an improvement in 32 of 36 core indicators spanning crime, education, health, worklessness, community and housing, and the physical environment (Batty et al. 2010). The areas worked well with delivery agencies, which included their parent local authority, especially those with a remit to help improve services within the neighbourhoods (Batty et al., 2010).

Community business funds are another form of funding mechanism, and their success can depend to some extent on the ability to gain the support of and create long-lasting and effective relations with local partners. This is exemplified by the South Yorkshire Social Infrastructure Programme, discussed in further detail below.

Case study – South Yorkshire Social Infrastructure Programme (SYSIP)

Local authorities enabled a social infrastructure programme in Yorkshire via funding and sustained support. The SYSIP included six projects to increase the sustainability of the voluntary and community sector. The programme operated differently across four South Yorkshire districts. An evaluation of the SYSIP found that the flexible approach across different districts enabled local partners to shape the funding to local needs. A key objective of the programme was the modernisation of core district-level infrastructure services, and this was mostly achieved thanks to the important role of sustained local partner support, primarily from local authorities (CRESR, 2010).

In some cases, however, local authorities have been identified as a barrier to community-based social enterprises. An assessment of community-based social enterprises in three European countries, including England, found that local authorities and housing associations often have limited power and resources to support community-based social enterprises, and much depends on personal contacts through political representatives or highly motivated officers (Bailey et al., 2018). Conversely, an example of when local authority partnerships has been beneficial is Millfields Trust, based in Plymouth, which has a good relationship with Plymouth city council. This has resulted in leases of greater length and below market value for land and buildings (Bailey et al., 2018).

For community-owned assets, however, the asset transfer can be complex, and it may be hindered if the local authority does not have the resources to support this process. This has occurred in the context of community businesses in the health and wellbeing sector, where case studies of asset transfer found that this process can be impaired by a lack of human resources within local authorities (Richards et al., 2018a).

4.4.8 Local non-government partnerships

- There is medium evidence that partnerships with local non-government organisations have supported effective infrastructure.

- For example, community transport organisations are a type of community infrastructure which have benefitted from partnerships with funders, other delivery organisations and organisations able to offer support and advice (Kotecha et al., 2017). Partnerships with other community transport organisations included ad hoc arrangements, such as sharing car parking spaces, as well as more serious agreements, for example grouping together as a consortium to bid for contract work. This evidence also found that the partnership with the Community Transport Association helped businesses to navigate transport regulation (see section 4.5.1).

- Public spaces are another type of community infrastructure which have been successful in many cases, which to some extent is a result of partnerships. An example of this is the creation of a public gathering space in Portland, Oregon, which was enabled by collaboration between urban planners, community groups and non-profit organisations, resulting in new urban design features that are conducive to social interactions and community stewardship (Semenza and March, 2009). A review of seven case studies on green spaces found that intersectoral partnerships to facilitate implementation and reducing barriers were important (South et al., 2021).

4.4.9 Physical capacity and utilisation of community infrastructure

There is medium evidence that the physical capacity of the community infrastructure itself is an important factor that can impact on its effectiveness. Likewise, the degree of utilisation is also an important factor.