Public trust in charities 2022

Published 14 July 2022

Applies to England and Wales

Research conducted on behalf of the Charity Commission by Yonder.

April 2022

Summary

We have all experienced the unprecedented disruption that the Covid pandemic has brought to modern life. Some of those changes are undoubtedly here to stay.

The charity sector has been no exception. Many charities have had to adopt new digital working practices, access alternative sources of funding, or change the services they provide in order to respond to new needs. Members of the public have been unable to support or volunteer in ways they might usually have done.

In this context it is tempting to assume that we would see shifts in terms of how people perceive charities. It is almost certainly true that the pandemic will have at least some lasting consequences for the way people give, though the full extent and nature of those changes will only become clear in the course of time.

But when it comes to how people think about charities’ place in society and how much trust they can place in them and why, our quantitative and qualitative research provides a clear conclusion: little has changed.

The public continues to believe that charities are an important part of society, provided that they meet four consistent expectations. Trust in charities remains higher than in most other parts of society – a reflection of the value the public thinks that charities can bring and have brought throughout the Covid pandemic. There is, however, a stubbornly persistent scepticism regarding how charities use their money and how they behave. This was true before the pandemic and is still true now.

These four public expectations are:

- That a high proportion of charities’ money is used for charitable activity

- That charities are making the impact they promise to make

- That the way they go about making that impact is consistent with the spirit of ‘charity’

- That all charities uphold the reputation of charity in adhering to these

So what can charities do to address remaining scepticisms and put public trust on an even stronger footing? In this year’s report, we highlight the fundamental importance of proactively demonstrating where donors’ money goes and how that money leads to impact.

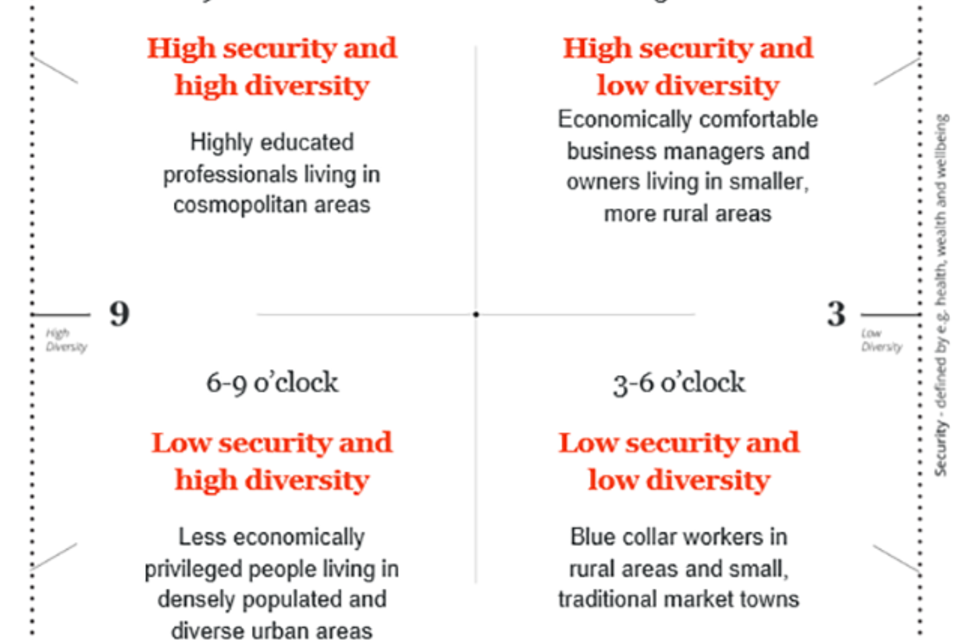

We also show that this challenge is greater in some parts of the population than others. Using a demographically derived model of the public called the Clockface (See Annex 1), we show that there is a particular trust deficit in the less secure, less diverse part of the English and Welsh population.

Our modelling shows that, more broadly, different parts of the population hold sometimes opposing outlooks about the role that charities should play in shaping society and pushing for social change.

These differences in outlook cannot be ignored if charities want to expand their support and bring along as much of the public as possible in their efforts to improve lives and change society for the better.

What is the public opinion landscape for charities post-pandemic?

Trust in charities remains higher than most other parts of society but has fallen across the board

Mean trust and confidence by sector / group out of ten

| Sector | Mean trust and confidence | Change since 2021 |

|---|---|---|

| Doctors | 7.2 | -0.5 |

| Charities | 6.2 | -0.2 |

| Police | 5.8 | -0.8* |

| Banks | 5.6 | -0.2 |

| The ordinary man / woman in the street | 5.5 | 0.1 |

| Social services | 5.3 | -0.5 |

| Private companies | 5.0 | -0.3 |

| Your local council | 4.9 | -0.6* |

| Newspapers | 3.9 | -0.4 |

| MPs | 3.4 | 0.7* |

| Government ministers | 3.2 | 0.8* |

Q. Now for some other types of organisations. On a scale of 0-10 where 10 means you trust them completely and 0 means you don’t trust them at all, please tell me how. Base (4,348)

Quotes from research

“Overall, I’m pretty positive towards charities. Use your common sense and your judgment.”

“I do support quite a few charities, and I wouldn’t do that if I thought there was anything amiss and that the money wasn’t going where it was supposed to go.”

“You can’t just trust everyone because there are fraudsters out there. You need to be wary, and obviously there are stories about fraud. Not everyone has a moral compass. That doesn’t mean to say you should be so sceptical that you can’t trust the people that are doing good work. Like anything in life, you have to use your instincts to make choices, and that’s no different for charity.”

The trust recovery for charities has plateaued

Historic trust levels remain elusive

The past year has been bruising for public trust in institutions. Our polling shows that the political establishment and the police have suffered significant declines in trust, roughly on par with the trust crisis that charities experienced after 2014.

All other parts of society have experienced falls in trust of varying degrees.

In this context, charities are faring as well as might be hoped, but historic trust levels remain elusive. Why is this?

Our interviews with members of the public from across the Clockface (i.e.. drawn from different corners of the population) reveal that the charity sector still struggles to shrug off lingering doubts about the way it uses the funds that are entrusted to it. These doubts have little to do with the pandemic or with other institutions. Such scepticism is particularly acute in the low security, low diversity part of the public.

| Year | Mean trust and confidence in charities |

|---|---|

| 2005 | 6.3 |

| 2008 | 6.6 |

| 2010 | 6.6 |

| 2012 | 6.7 |

| 2014 | 6.7 |

| 2016 | 5.7 |

| 2018 | 5.5 |

| 2020 | 6.2 |

| 2021 | 6.4 |

| 2022 | 6.2 |

Q. Firstly, thinking about how much trust and confidence you have in charities overall, on a scale of 0-10 where 10 means you trust them completely and 0 means you. Base (4,348)

| Year | General public mean trust in charities | Top left mean trust in charities | Bottom right mean trust in charities |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 6.2 | 6.7 | 5.6 |

| 2021 | 6.4 | 7.0 | 5.9 |

| 2022 | 6.6 | 6.8 | 5.5 |

Q. Firstly, thinking about how much trust and confidence you have in charities overall, on a scale of 0-10 where 10 means you trust them completely and 0 means you. Base 2022 (4,348), 2021 (4,037), 2020 (4,042)

The trust gap between different parts of the population is stronger than ever

Percentage of respondents who gave a trust score of 7-10 for charities

| General public mean trust in charities | Top left mean trust in charities | Top right mean trust in charities | Bottom right mean trust in charities | Bottom left mean trust in charities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 51% | 66% | 54% | 46% | 37% |

Q. Firstly, thinking about how much trust and confidence you have in charities overall, on a scale of 0-10 where 10 means you trust them completely and 0 means you. Base (4,348)

The top left are currently a charity trust stronghold. Despite a decline, a majority of those in the high security, high diversity part of the public still trust charities. For those in the bottom right, there is an increasing vulnerability in charity trust, where trust has fallen further amongst those in the low security part of the public.

| Clockface position | Change since last year |

|---|---|

| General public | -4% |

| Top left | -4% |

| Top right | +1% |

| Bottom right | -10% |

| Bottom left | -7% |

Q. Firstly, thinking about how much trust and confidence you have in charities overall, on a scale of 0-10 where 10 means you trust them completely and 0 means you. Base 2022 (4,348), 2021 (4,037)

The trust gap applies to other sectors too

Percentage of respondents who gave a trust score of 7-10 to at least half of the sectors tested

| General public mean trust in charities | Top left mean trust in charities | Top right mean trust in charities | Bottom right mean trust in charities | Bottom left mean trust in charities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24% | 28% | 34% | 18% | 10% |

Q. Now for some other types of organisations. On a scale of 0-10 where 10 means you trust them completely and 0 means you don’t trust them at all, please tell me how. Q. Firstly, thinking about how much trust and confidence you have in charities overall, on a scale of 0-10 where 10 means you trust them completely and 0 means you. Base (4,348)

Those in the top half of the Clockface (those who are more economically secure) are more likely to trust sectors in general. Whilst those in the bottom half of the quadrant are less trusting of sectors.

| Clockface position | Change since last year |

|---|---|

| General public | -8% |

| Top left | -5% |

| Top right | -5% |

| Bottom right | -15%* |

| Bottom left | -11%* |

Q. Now for some other types of organisations. On a scale of 0-10 where 10 means you trust them completely and 0 means you don’t trust them at all, please tell me how. Q. Firstly, thinking about how much trust and confidence you have in charities overall, on a scale of 0-10 where 10 means you trust them completely and 0 means you. Base 2022 (4,348), 2021 (4,037)

The perceived importance of charities also remains below historic levels

Reversion to the low point

In addition to stalling trust, there has also been a negative reversion when it comes to how important the public thinks charities are.

Just over half say that charities are ‘essential’ or ‘very important’ for society, down from a high of 76% a decade ago.

It is again the case that there are far more who are sceptical about the value that charities can bring to society among the less diverse and less secure part of the public (bottom right, or 3-6 o’clock, on the Clockface). This too can largely be accounted for by those same doubts about propriety and stewardship of funds.

These findings, and the differences of opinion that exist regarding charities’ role in society, have implications for whether the public trusts them to push for social change and shape cultural debates.

We explore these attitudes, and how charities can effectively communicate with the public to address them, in the following section.

| Year | Mean trust of confidence in charities |

|---|---|

| 2008 | 72% |

| 2010 | 67% |

| 2012 | 76% |

| 2014 | 75% |

| 2016 | 69% |

| 2018 | 58% |

| 2020 | 55% |

| 2021 | 60% |

| 2022 | 56% |

Q. Firstly, thinking about how much trust and confidence you have in charities overall, on a scale of 0-10 where 10 means you trust them completely and 0 means you. Base (4,348)

| Year | General public mean trust in charities | Top left mean trust in charities | Bottom left mean trust in charities |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 55% | 68% | 44% |

| 2021 | 60% | 74% | 50% |

| 2022 | 56% | 70% | 43% |

Q. Firstly, thinking about how much trust and confidence you have in charities overall, on a scale of 0-10 where 10 means you trust them completely and 0 means you. Base (4,348)

How to inspire trust & communicate with the public

Public expectations of charities include four key factors

- Where the money goes: That a high proportion of charities’ money is used for charitable activity

- Impact: That charities are making the impact they promise to make

- The ‘how’: That the way they go about making that impact is consistent with the spirit of ‘charity’

- Collective responsibility: That all charities uphold the reputation of charity in adhering to these

These expectations are drawn from quantitative and qualitative data from across the research programme over recent years.

How charities are perceived to perform against these expectations determines how much the public trusts them.

Most people tentatively think that charities are meeting key expectations, though doubts remain

To what extent do you think that charities you know are…

| Statement | Very much so | To some extent | Only a little | Not at all | Don’t know |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Making an impact | 22% | 50% | 14% | 2% | 12% |

| Well-run | 13% | 48% | 15% | 3% | 21% |

| Operating to high ethical standards | 24% | 45% | 15% | 3% | 23% |

| Delivering a high proportion of the money that raise to those they are trying to help | 25% | 41% | 19% | 5% | 19% |

| Treating their employees well | 13% | 36% | 11% | 2% | 39% |

Q. Which of the following do you think are most important when it comes to the way an individual charity operates? Please select up to three. Base (4,348)

| Statement | Change in agreement of very much so / to some extent since last year |

|---|---|

| Making an impact | -1% |

| Well-run | -3% |

| Operating to high ethical standards | -5% |

| Delivering a high proportion of the money that raise to those they are trying to help | -3% |

| Treating their employees well | -3% |

The greatest area of doubt is still around whether a high proportion of money reaches intended beneficiaries

Percentage who doubt that donors’ money reaches intended beneficiaries

|

General public who believe only a little or none at all of money raised helps those intended |

Top left who believe only a little or none at all of money raised helps those intended |

Top right who believe only a little or none at all of money raised helps those intended |

Bottom right who believe only a little or none at all of money raised helps those intended |

Bottom left who believe only a little or none at all of money raised helps those intended |

| 25% | 16% | 22% | 29% | 33% |

Q. And to what extent do you think that charities that you know about are delivering a high proportion of the money they raise to those they are trying to help. Base (4,348)

There is greatest doubt in the less secure parts of the population.

| Clockface position | Change since last year |

|---|---|

| General public | +3% |

| Top left | +3% |

| Top right | -1% |

| Bottom right | +7% |

| Bottom left | +4% |

Q. And to what extent do you think that charities that you know about are delivering a high proportion of the money they raise to those they are trying to help. Base 2022 (4,348), 2021 (4,037)

Demonstrating where money goes & that impact is being made

These things are fundamental to trust in charities, above all else.

What expectations do the public have with regards to demonstrating fund stewardship, and how can charities most effectively communicate the positive impacts they are having?

It is difficult to exaggerate how important these perceptions are when it comes to trying to increase trust in charities

Lingering doubts

Doubts about where donors’ money goes continue to be brought up early on and without prompting in our conversations with members of the public. This applies to different parts of the public, across the Clockface.

Most people are still instinctually inclined to trust charities but this year’s research confirms again that the uncertainty about the use to which donations are put remains stubbornly widespread.

Interviewees continue to bring up both anecdotal evidence of charities either being created for personal gain or not using funds as intended, or media stories of charities in the public eye misappropriating funds.

It is the latter – media stories involving high-profile charities – that seems to have the greatest and longest-lasting impact.

Quotes from research:

“I always decide to trust something unless I’m being shown that it’s untrustworthy. There have been cases in the news over the years around the behaviour of staff working for certain charitable organisations, sending money inappropriately, or certainly behaving inappropriately in the name of that charity. That worries me. That’s not an argument to stop having charities, that’s an argument to regulate them more closely so that they’re not able to get away with these sort of things.“

“I was donating to a local chap in the area that was supposedly taking the money to third-world countries, Africa for example and making wells. Then it came out, I don’t know how it got out, but it came out that he was using the money to go to these places and using on himself. There might have been a bit of time where he would use the money for charity for wells, but most of it he was pocketing to fund his lifestyle over there. So that obviously put me off donating like that.”

How can charities assuage these concerns?

Proactive transparency

The public understands that not all money can reach beneficiaries directly, but even so they think charities should do more to sufficiently demonstrate that the proportion that does is maximised.

When probed on the form and extent of expenditure that they would be willing to accept, members of the public struggle to define those parameters precisely but accept that a reasonable minority must be spent on administrative costs and overheads.

However, senior salaries remain contentious, particularly in the less secure parts of the public. There is greatest scrutiny here on larger charities, though members of the public recognise that larger charities are likely to have higher salary expenditures (as well as greater costs overall) to allow them to achieve far-reaching impact. To combat those concerns, charities should prominently display visual breakdowns of how donations are spent and to show that expenditures (like salaries) are not gratuitous. Many charities already do this and should continue to do so.

Quotes from research:

“I’ll be honest. I don’t implicitly trust charities, for the good reason that I know somebody who works at a charity, and he earns £100,000 a year. There’s an argument that you need to pay people good money to get the best people, but then also you just think, how has the charity got that much money? To me, that made me feel ‘that’s not quite right’, but I understand why they do it.”

“I feel that sometimes, the money could be put to better use. I’m sure a lot of it they do use for the greater good, but you hear of big CEOs getting an awful lot of money and spending money on offices, where it feels like it’s probably not where it should be going!”

“I suppose it would be a bit different depending on size. The bigger ones will probably achieve more, but they’ll also have more wastage, I’d guess. Whereas at [a smaller charitable organization], I can see first-hand the difference they make.”

Demonstrating impact goes hand-in-hand with this

Particularly for larger charities

As well as wanting a more proactive approach from charities in communicating how money is spent, members of the public also stress the importance of demonstrating impact.

Those who make regular donations or contributions to charity are more likely to trust the charity in question if they are given clear, regular updates about the impact their support is having.

This also helps to reassure members of the public that money is being spent effectively. There is a general perception that local charities are better able to demonstrate the tangible impact they have due to the charity’s and the donor’s likely proximity to the beneficiaries.

The impact that larger and international charities have (and the way they go about achieving that impact) is generally viewed as more opaque. There is a particular onus on those charities to lead the way in proactively demonstrating impact and ethical conduct at every turn.

Quotes from research:

“I think charities should be more open. You walk into a shop, you see all these lovely goods that they’ve got on display that people have donated. What’s wrong with putting a poster up saying, ‘We did ‘this’ last year, we helped so many people last year.’ Put it there so that people can see the results, because it’s great to have positive feedback from charities.”

“An example that I could give is when I was donating to an animal charity, they provided me with leaflets like a book or a portfolio, showing the animals that I was donating to each month. They were showing photos of them, and a little profile of what happened this month with the money that people have donated. That made me happy because it showed me where the money was going.”

Engaging in social and cultural debate

Charities, like all organisations in public life, are increasingly called upon to engage in social and cultural debates and play a role in enabling social change.

How can charities do so in a way that avoids polarising their supporters and brings different parts of the public with them on the journey?

The public tends to think charities should respond to social and cultural debates but there is no strong consensus

Participants were presented with both statements and asked to say where their view lay, where 0 would mean total agreement with statement A and 10 would mean total agreement with statement B. Here, we show the percentages who tend towards each quoted statement (scores of 0-4, or 6-10), and those ‘on the fence’ (5). Statement orders were rotated.

|

Respond to social debates “Charities should respond to social and cultural debates if they want to stay relevant and keep the support of people like me” |

on the fence |

Don’t get involved “Charities should not get involved in social and cultural debates if they want to keep the support of people like me” |

| 41% | 29% | 31% |

Q. Please read the following pairs of statements. In each case, please use the scale to indicate which statement you agree with, using a 0-10 scale on which 0 means you completely agree with statement A, and 10 means you completely agree with statement B. Base (4,348)

|

Push for change if it helps meet needs “There’s nothing wrong with charities pushing for change in society, if it helps them meet the needs of those who rely on them” |

on the fence |

Focus on needs only, not pushing for change “Charities should focus on meeting the needs of those who rely on them, rather than pushing for change in society” |

| 51% | 18% | 31% |

Q. Please read the following pairs of statements. In each case, please use the scale to indicate which statement you agree with, using a 0-10 scale on which 0 means you completely agree with statement A, and 10 means you completely agree with statement B. Base (4,348)

Pushing for social change can be effectively justified to most of the public if it relates to the charitable purpose

A question of purpose

Members of the public rarely bring up unprompted the role charities play in shaping social or cultural debates on topics such as diversity and inclusion.

They rarely notice news stories of charities directly engaging in such matters. More generally, they do reference the work that charities do to affect social change by, for instance, assisting the vulnerable, addressing inequalities or tackling climate change.

They think that facilitating this kind of social change is within charities’ remits – that at the purest level they exist to improve the way society works and the overall outcomes it produces, particularly when it comes to the vulnerable. They are comfortable with charities pushing for change within areas specifically related to their expertise.

Where there is some concern about charities pushing for social change, it is when that could be seen to detract or distract from the charity’s stated purpose, or when the charity is seen to be overreaching the activities implied by that purpose. Here, there are likely to be differences of opinion in interpreting what this means in practice, depending on the individual’s background and outlook.

Quotes from research:

“Charities stand up for people that sometimes don’t have a voice, or don’t have a platform to get their views heard. So yes, I think it’s very important.”

“Social change to me is anything that is helping to improve society for the better. It can be small-scale change or it can be large-scale. Charities could have a voice [in social and cultural debates], but then I don’t necessarily think they should be listened to. It depends on the credibility and the background. I sound really mean but for me, I just prefer governmental people making rules rather than charities.”

“Your main focus should be looking out for what you’re doing. You don’t build a charity to then go into politics.”

There exists both an expansive interpretation of what this means in practice and a stricter one

Differences of opinion

When interpreting whether or not an intervention by a charity in pushing for change or engaging in social and cultural debates is related to its purpose, you are likely to encounter differences of opinion across the Clockface.

Those in the more diverse part of the public (the left-hand side of the Clockface) are more likely to view charities as experts in their fields, and to think that those fields intersect with important social and cultural outcomes. They are therefore relaxed about charities’ abilities to respond to social and cultural debates in a way that is constructive.

Those in the less diverse part of the public (the right-hand side of the Clockface) are dubious about charities having a role in social and cultural debates, and favour a stricter interpretation of how ‘pushing for social change’ or ‘engaging in social and cultural debate’ can relate to a charity’s remit. They question whether some charities have the appropriate expertise to engage in such work, preferring instead for elected officials to make policy decisions on behalf of society. They are sensitive to any suggestion of charities ‘politicising’ their work.

Quotes from research:

“They’re raising awareness of the situations of people who often don’t have a voice to raise themselves.”

“I think it’s good. It can only be a good thing. The more it’s done, the more people are made aware, and hopefully, the quicker [prejudice and social problems] get eradicated.”

“I don’t know whether they should get too politically involved in things. I’m thinking they should be offering practical help. [I don’t know] whether they should be involved in political matters – and I don’t even know if they are involved. But [they should not be] taking on battles that they shouldn’t be involved in.”

Views on whether charities should or should not respond to social debates vary significantly

Percentage who agree that charities should respond to social and cultural debates if they want to stay relevant and keep support of people like them

| General public agreement | Top left agreement | Top right agreement | Bottom right agreement | Bottom left agreement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 41% | 61% | 31% | 25% | 50% |

Q. Please read the following pairs of statements. In each case, please use the scale to indicate which statement you agree with, using a 0-10 scale on which 0 means you completely agree with statement A, and 10 means you completely agree with statement B. Base (4,348)

Those in the less diverse part of the population (the right-hand side) tend not to think that charities should respond to social and cultural debates, while those in the more diverse part (the left-hand side) tend to think they should.

Views on whether charities should or should not respond to social debates vary significantly

Percentage who agree that there’s nothing wrong with charities pushing for change in society, if it helps them meet the needs of those who rely on them.

| General public agreement | Top left agreement | Top right agreement | Bottom right agreement | Bottom left agreement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 51% | 71% | 42% | 35% | 60% |

Q. Please read the following pairs of statements. In each case, please use the scale to indicate which statement you agree with, using a 0-10 scale on which 0 means you completely agree with statement A, and 10 means you completely agree with statement B. Base (4,348)

Similarly those in the less diverse part of the population (the right-hand side) tend to be less convinced than the those on the left-hand side that charities should push for social change if it helps them meet the needs of those who rely on them.

Those in the left of the clockface were more supportive of the values charities can bring

Quotes from research:

“If there’s a way for them to get involved with the bigger issues, or to bring that forward, then yes [I think they should be involved in that].” Top left

“It’s easy to justify their voice in these debates because they’re the ones that are helping. They’re bringing nothing but positives to the table, if they’re doing what charity should. They have the moral high ground to say what they want.” Bottom left

Whilst, those on the right of the clockface were more critical of undue interference

Quotes from research:

“Nowadays, there are too many chiefs and not enough Indians. Certain people in certain businesses shouldn’t have control over something which is really nothing to do with them. A charity is there to make things better, but I don’t think that gives them the right to say, ‘well, when it comes to government issues…’ There are people out there already trying to do that.” Top right

“I think they should stay out of it. I mean, Oxfam did themselves no good with their statement about everybody having to have this woke attitude. That actually stopped a lot of people of my age group from having any further involvement with them. When they say, ‘white people are racist,’ the way they put it in their letter that they sent out to staff, I’m surprised they’ve got any white staff left. It was a very bad move, a very costly move.” Bottom right

Addressing regional economic disparities is seen as a responsibility for Government, not the charity sector

Charity sector to support equality of opportunity, not to be responsible for it

To what extent do you think each pf the following should have responsibility for narrowing the gap in living standards and investment that exists between different regions of the UK

| Responsibility | The Government | Local politicians | Local people | The charity sector |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total responsibility | 43% | 16% | 5% | 2% |

| A fair amount of responsibility | 45% | 55% | 37% | 18% |

| A little responsibility | 6% | 16% | 38% | 41% |

| No responsibility | 1% | 2% | 10% | 26% |

| Don’t know | 5% | 6% | 10% | 12% |

Q. To what extent do you think each of the following should have responsibility for narrowing the gap in living standards and investment that exists between different regions of the UK? Base (4,348)

Different parts of the public, across the Clockface, agree that government is ultimately responsible for addressing regional economic disparities, though all parts of society should aim to contribute where they can.

They think that charities have a role in improving opportunities and reducing inequalities, but that this role mostly relates to supporting those who are unable to access the level of support or funding that they need. They are uncomfortable with the idea that the shortcomings of the support or funding structures themselves should become charities’ responsibility.

Quotes from research: “That would have to be the government, wouldn’t it?”

“Of course, charities ought to be playing a part, but it definitely doesn’t just come down to them. I think it comes down to everybody, doesn’t it? The government obviously have got a huge part to play, because they hold the purse strings and the power. Us as a society also need to take some sort of responsibility for the world that we live in.”

How the regulator can help uphold public trust and help the sector thrive

Real knowledge of the Commission remains low

But expectations are high

Our quantitative and qualitative research shows that the public has little real knowledge or understanding of what the Charity Commission does (though around half have heard of it by name).

Awareness of the Commission

| Year | Percentage of the public who have heard of the Charity Commission | Percentage of the public who say they know it very or fairly well |

|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 52% | 13% |

| 2020 | 53% | 19% |

| 2021 | 54% | 19% |

| 2022 | 50% | 18% |

Q. Have you ever heard of the Charity Commission? Base (4,348)

Most assume that there is a regulator for the charity sector, even if they have not considered what that role entails. Their assumptions about what that regulator would do, once prompted, help us to understand what regulating in the public interest means in practice.

Due to the public’s central expectation that charities should ensure that a high proportion of the funds they receive reaches beneficiaries or the end cause, and doubts about how common fraudulent behaviour might be, members of the public tend to express a preference for an active, rather than passive, charity regulator.

When the Commission is prominent in the news, this is no bad thing

A small net-positive effect

Around half of those who have heard of the Charity Commission either have not noticed it in the news in the past 12 months or don’t know if they have.

The small number of people who have noticed the Commission in the news more frequently in the past year are more likely than not to say that this has increased their confidence in the charity sector. Among those who had seen the Commission in the news less frequently, there is a net neutral impact. Overall then, the Commission’s presence in the news appears to have a small but positive effect (though cases of wrongdoing themselves, as reported in the media, cause trust to decrease).

Our qualitative research supports this. Members of the public assume that the regulator would and should be in the news to show evidence that charities are being held accountable. For most, the awareness of an active regulator provides reassurance, though a few acknowledge that the highlighting of malpractice itself undermines their confidence in the sector.

Awareness of the Commission in the news in the last 12 months, for those who have heard of the Commission

| Commission awareness | % |

|---|---|

| More often | 9% |

| Less often | 8% |

| As often | 34% |

| Not at all | 43% |

| Don’t know | 6% |

Q. Thinking about the Charity Commission over the past 12 months, would you say you’ve noticed it being in the news more often, less often or about as often as before? Base (2,158)

Changes in confidence of the charity sector as a whole due to noticing the Commission more often in the news

| Confidence of the sector | % |

|---|---|

| More confident | 42% |

| No difference | 35% |

| Less confident | 22% |

Q. And does the fact that you have noticed the Charity Commission in the news less mean you have more confidence in the charity sector as a whole, less confidence in the charity sector as a whole, or does it not make any difference? Base (88)

Changes in confidence of the charity sector as a whole due to noticing the Commission less often in the news

| Confidence of the sector | % |

|---|---|

| More confident | 25% |

| No difference | 49% |

| Less confident | 25% |

Q. And does the fact that you have noticed the Charity Commission in the news less mean you have more confidence in the charity sector as a whole, less confidence in the charity sector as a whole, or does it not make any difference? Base (1,087)

While they might not closely follow what it does, the public wants a proactive regulator to uphold public expectations

Proactive regulation is expected

As in previous years, our quantitative research shows that the public tends to think that the regulator should make sure that charities fulfil their wider responsibilities as well as sticking to the law, though a significant minority favours a regulator that confines itself only to ensuring charities stick to the letter of the law.

Our qualitative research supports this. On balance, members of the public expect the Charity Commission to actively investigate whether donations are used appropriately and whether funds are reaching beneficiaries.

There is an expectation that the Commission should proactively investigate standards of conduct and uncover incidents of wrongdoing, as well as advise charities about best practice. Members of the public envisage the Commission carrying out regular audits and checks on charities and making this information publicly available, in the manner of more proactive regulators such as Ofsted or the Food Standards Agency.

Participants were presented with the statement and asked to say where their view lay, where 0 would mean total agreement with statement A and 10 would mean total agreement with statement B. Here, we show the percentages who tend towards each quoted statement (scores of 0-4, or 6-10), and those ‘on the fence’ (5). Statement orders were rotated.

|

Go beyond assessing legal compliance “The charity regulator should try to make sure charities fulfil their wider responsibilities to society as well as sticking to the letter of the laws governing charitable activity” |

on the fence |

Confine to assessing legal compliance “The charity regulator should confine its role to making sure charities stick to the letter of the laws that govern charitable activity” |

| 48% | 23% | 29% |

Q. Please read the following pairs of statements. In each case, please use the scale to indicate which statement you agree with, using a 0-10 scale on which 0 means you completely agree with statement A, and 10 means you completely agree with statement B. Base (4,348)

Quotes from research:

“They should hold them to account to make sure that they’re working within the law; that the right percentages of money are going where they should be; that they’re ethically sound; that they’re working for the principles that they’re telling donors they’re working for.”

“You need to monitor them: what they’re doing, how they’re doing it, why they’re doing. There’s a huge responsibility to make sure that people’s money gets to the right places.”

Registration plays a role in upholding trust & confidence

A badge of extra confidence

Registered status remains a powerful marker of charities doing the right thing in the public mind.

A majority believe a charity is more likely to be making an impact, maximising its donations and operating ethically if it is registered and regulated by the Charity Commission.

Percentage who have more confidence about each of the following if they know a charity is registered.

| Statement | Percentage who are more confident | Change since last year |

|---|---|---|

| That a high proportion of the money it raises goes to those it is trying to help | 78% | 0% |

| That it’s making an impact | 76% | -2% |

| That it operates to high ethical standards | 74% | -1% |

| That it’s well-run | 70% | -1% |

| That it’s doing work central and local government can’t or won’t do | 66% | -2% |

| That it treats its employees well | 65% | -2% |

Q. And if you knew that an organisation was registered as a charity, which of those things would you feel a) no differently about, b) slightly more confident about, or c) a lot more confident about? Base 2022 (4,348), 2021 (4,037)

Quotes from research:

“It kind of releases that burden of knowing where our money’s gone.”

“I’m always really cautious to look for the registered number, because I know that there are some scams out there, unfortunately.”

Methodology note

Quantitative data and analytics

Yonder surveyed a demographically representative sample of 4,348 members of the English and Welsh public between 8 and 15 February 2022. A boost was applied to the Welsh portion of the sample to ensure that we had over 500 responses from that nation. The survey was conducted online.

Answer options were randomised and scales rotated. All questions using opposing statements were asked using a sliding scale.

The data was analysed using Yonder’s ‘Clockface’ model to help understand the various elements of public opinion and ensure the Charity Commission’s work is rooted in an understanding of the social and economic dynamics at play across the English and Welsh public.

Qualitative data

Yonder conducted 20 in-depth interviews with members of the public from across the Clockface model’s two-dimensional map of ‘security’ and ‘diversity’ and with a geographical spread across England and Wales. Interviews were conducted between 14 and 25 March 2022.

Each interview lasted around 30 minutes.

Annex 1 - Introduction to the Clockface

Introduction to the Clockface: who are ‘the public’ and what does ‘charity’ mean to them?

Public opinion isn’t monolithic

Statistics about public opinion usually hide a very important truth – that there is no single ‘public opinion’.

Instead, whether we know it or not, we all exist within bubbles that we tend to share with people who have similar demographics, backgrounds, and circumstances to ourselves.

Those demographics, backgrounds and circumstances go a long way in explaining differences of opinion and behaviour. They help to shed light on things that unite us and the things that increasingly seem to divide us.

If you associate only with people from your own social and educational background, you risk two things: overestimating the extent to which people outside your direct experience agree with you; and demonising those who don’t.

We use a model of the population – called the Clockface – to help us to avoid that by understanding and defining the differences of opinion that exist between different corners of the population.

Every person in the country occupies a position on the Clockface map that is shown on the next page.

Clockface diversity chart

The position that every person occupies on the Clockface is defined by two sets of characteristics:

- security, combining measures of health, wealth and wellbeing such as income, occupation and education

- diversity, a combination of factors including ethnicity, culture and population density which determine how close you are to your neighbour in distance or background.

People located between 12-3 o’clock, for instance, are high in the bundle of measures we call ‘security’ but low in those we call ‘diversity’, and that will influence how they behave, think and feel.

Applying polling data to this model can show us exactly how these differences in outlook play out.

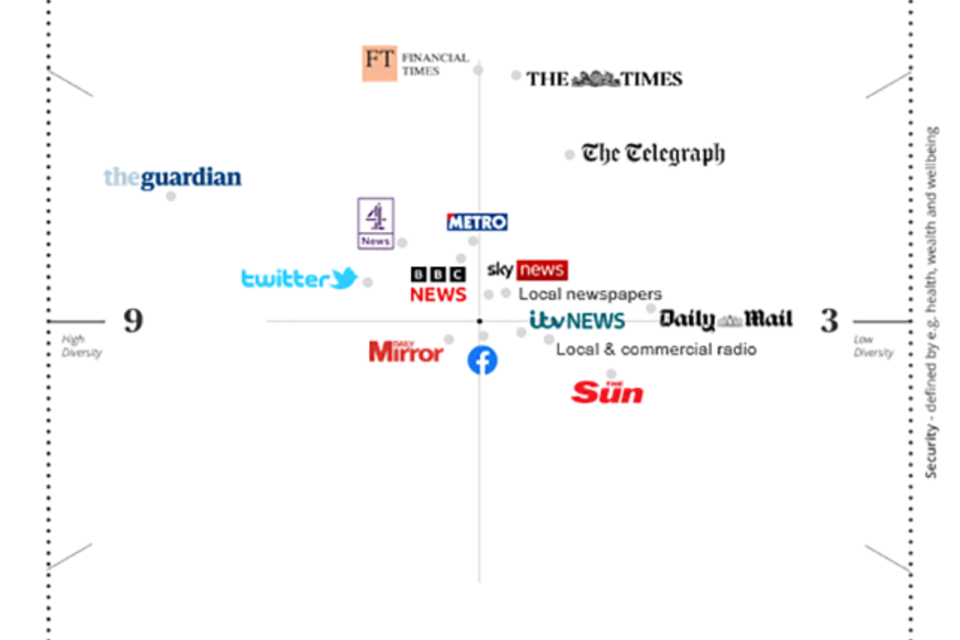

Take something like where you get your news.

Here is the average position on the Clockface of those who say they get their news at least once a week from the sources shown. The Clockface image shows, for example, that you are most likely to find a reader of the Guardian in the high diversity, high security quadrant; a Sun reader in the low security, low diversity quadrant.

You can of course find readers or viewers of any particular source anywhere on the map, but the Clockface image show where you are more likely to encounter them.

Wordcloud of media outlets

The public & charity

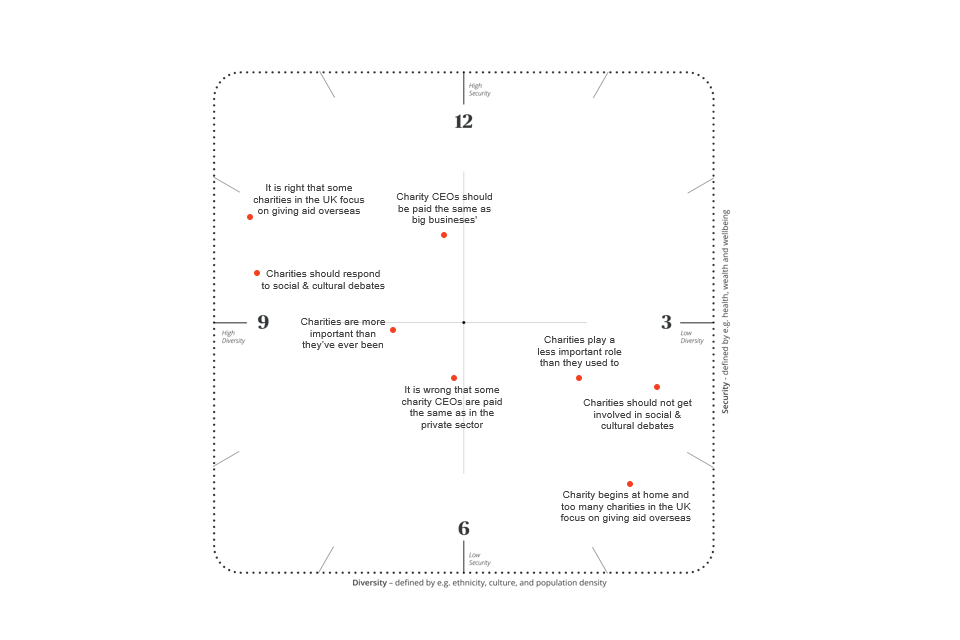

Views about charities can also be placed on the Clockface.

Whether people prefer charities with a local or international focus, whether it is acceptable for their work to overlap, whether they should be run by professionals or volunteers – you can encounter different points of view on issues like these anywhere in the population, but certain perspectives are more prevalent among some parts of the public than others.

Those prevalences reflect the different experiences and circumstances that shape people’s thinking and behaviour.

There are certain things that unite all parts of the public across the Clockface – like the expectation that donors’ money should reach the intended cause or that charities must provide evidence about the impact they’re having.

But there are other issues – like the role charities should play in shaping wider social and cultural debates – for which it is harder to reconcile different parts of the public and their different standpoints.

A view that might seem self-evidently correct to a person in one part of the Clockface could be strongly contested by someone else in another.

The Clockface image below shows that you are most likely to find supporters of overseas charities and those who think that charities should engage in social and cultural debates in the higher security, higher diversity part of the population. Those who think the opposite are most likely to be found in the lower security, lower diversity part of the population.

In the following pages, we outline the public opinion landscape in 2022 and try to unpick those differences, so that the charity sector can better navigate them.

Views about charities placed on the Clockface