Evidence review: Digitalising welfare services

Published 7 October 2024

Abbreviations

AI

artificial intelligence

AR

augmented reality

DWP

Department for Work and Pensions

EU

European Union

ICT

information communications technology

IoT

internet of things

IT

information technology

NAV

Nye arbeids- og velferdsetaten (Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration)

OECD

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

PSI

Public Services International

QSR

quick scoping review

REA

rapid evidence assessment

VR

virtual reality

Glossary

The term digitalisation is often used interchangeably with the terms digitisation and digital transformation in different contexts.[footnote 1] For this reason, it is important to provide working definitions and explain how these terms differ:

- Digitisation is defined as “the action to convert analogue or non-computerised information into digital information”.[footnote 2] An example of digitisation is the creation of digital versions (sometimes referred to as ‘soft copies’) of printed out documents (sometimes referred to as ‘hard copies’).

- Digitalisation goes beyond digitisation to describe how IT or digital technologies can be used to change existing processes.[footnote 3] Examples of this include the creation of new online or mobile communication channels to connect customers with firms or the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in digital service delivery. Digitalisation allows firms to use digital technologies to optimise their business processes through more efficient coordination, and to increase customer value by enhancing user experiences.[footnote 4]

- Digital transformation describes an organisation-wide change that leads to the development of new business models that may expand the focus of the organisation by generating new approaches to creating and capturing value.[footnote 5]

While all three terms are interconnected, this study is focused on digitalisation as relevant to the DWP (although we do include some evidence on digitisation where appropriate). This means that the study is not concerned with the simple process of converting analogue to digital data and processes (which has to large extent already been done by the DWP). Instead, this study is focused on the manner and extent to which the use of digital technologies can change the way that the DWP delivers its services to customers. The digitalisation process represents an opportunity to save on costs and – through rethinking processes – enhance customer experiences.[footnote 6] [footnote 7]

Other terms, which we are using in the report, are also defined in this section:

Artificial intelligence (AI):

The capability of a machine to imitate intelligent human behaviour.[footnote 8]

Blockchain:

A digital database containing information (such as records of financial transactions) that can be simultaneously used and shared within a large decentralised, publicly accessible network.[footnote 9]

Cloud computing:

The practice of storing regularly used computer data on multiple servers that can be accessed through the internet.[footnote 10]

Data mining:

The practice of searching through large amounts of computerised data to find useful patterns or trends.[footnote 11]

Digital sensors:

Devices which automate the collection, processing and analysis of data (e.g. from citizens and devices) to translate (parts of) processes into digital information.[footnote 12]

Internet of things (IoT):

The networking capability that allows information to be sent to and received from objects and devices (such as fixtures and kitchen appliances) using the internet.[footnote 13]

Interactive:

involving the actions or input of a user.[footnote 14]

Interoperability:

The ability of computer systems or software to exchange and make use of information. Can also be described as the ability of a system to work with or use the parts or equipment of another system.[footnote 15]

Machine learning:

The process by which a computer is able to improve its own performance (as in analysing image files) by continuously incorporating new data into an existing statistical model.[footnote 16]

Robotic process automation:

Software technology that makes it easy to build, deploy and manage software robots that emulate human actions interacting with digital systems and software.[footnote 17]

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the project team at the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) for their support throughout this study. In particular, we are grateful to Eleanor Doyle and Lucy Allen of the Business Strategy Directorate.

This report represents the views of the authors. Any remaining inaccuracies are our own.

The authors

Immaculate Motsi-Omoijiade, RAND Europe

Pamina Smith, RAND Europe

Axelle Devaux, RAND Europe

Joanna Hofman, RAND Europe

Dominic Yiangou, RAND Europe

Isabel Flanagan, RAND Europe

Madeline Nightingale, RAND Europe

Executive summary

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) is the largest public service department in the UK. It administers the State Pension and a range of working-age, disability and ill-health benefits to around 20 million claimants and customers, and many of these services are moving to being delivered online. DWP commissioned RAND Europe to review and supplement the evidence base around the impacts of digitalisation experienced by other private and public sector organisations. The evidence collected through this review can be used to inform strategic and operational decisions around the design of DWP digital services.

The review addresses a number of research questions, grouped into four areas of interest: 1) the impact that online provision of services has on costs and savings; 2) the impacts of digitalising services on customer experience; 3) the wider societal impacts of shifting services online, even if these are more difficult to quantify; and 4) lessons learned from the digitalisation process experienced as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

To respond to these questions, RAND Europe undertook a quick scoping review (QSR) complemented with additional manual searches and interviews with stakeholders in the UK and other countries who have significant experience in digitalising services.

In relation to costs and savings associated with the digitalisation of welfare services, we found that:

- Despite interest in the use of advanced digital technologies in service delivery, digitalisation is occurring across a narrow set of public services and is often limited to simple transactional tasks rather than the delivery of more-complex services.

- It is difficult to gather accurate estimates of the costs involved and savings generated due to the digitalisation of services. This review suggests that organisations could use a service-by-service approach to measure the financial and economic impacts of digitalisation.

- Digitalisation can offer staff-related cost reductions and savings. However, the extent to which these savings can be realised depends on other factors, particularly costs related to staff training and support.

- Digitalisation can result in reduced costs and increased savings in service delivery. However, these gains may be offset by increased demand spurred by digitalisation.

- The process of digitalisation is prone to technical difficulties, and digital channel failure (failure to achieve expected, pre-defined outcomes) is associated with unforeseen costs.

- This review notes that having multiple means for service access and delivery is a way to make service delivery more cost efficient.

Limited interoperability (the ability to exchange information across computer systems or software) and fragmentation of information were seen as obstacles to the digitalisation of welfare services.

In relation to customer experience, we identified different strategies that encourage customers to use digital channels and principles that facilitate the take-up of online services:

- guaranteeing customers that non-digital options are available, launching marketing or educational campaigns, and creating engagement teams were found to be successful

- designing a digital service with a high level of adoption and continued use requires careful attention to

- preferences and abilities among and within population segments, including preferences regarding privacy concerns and accountability

- aesthetic experience

- usefulness and ease of use

- context: if digital services increase burden for consumers or if they replace services that require urgent or very personal or emotional attention, they will fail to replace in-person services

In relation to societal effects of digitalisation processes and notable effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, we found that:

- Digitalisation processes may lead to more inequality. Evidence points out that particular attention should be given to ensuring that vulnerable populations, especially those at risk of digital exclusion, are protected from any negative effects related to accessing (digital) services or the internet – and its supporting technology more broadly. Evidence shows that this can be done in a number of ways, e.g. through establishing public Wi-Fi or other initiatives, both online and offline.

- The digitalisation accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic not only increased the type, quality and uptake of digital services, but also appears to have ensured the continued use of digital services in the future.

1. Introduction

1.1. Context

Information and communications technologies (ICT) are increasingly used to transform the public sector.[footnote 18] The COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated digitalisation by several years,[footnote 19] and it also boosted the digitalisation of government services. More than 80% of government services across 36 European countries are available online, and 6% of these services are delivered proactively (which means that no action is needed from customers to demand these services, as governments already assume that they are needed).[footnote 20]

In 2012, the UK Government Digital Strategy outlined plans for the government to become digital by default, meaning that digital services would be available to all those who can and choose to use them, while those who cannot are not excluded.[footnote 21] Subsequent developments centred on transforming government services and making them more efficient, such as through scaling successful solutions[footnote 22] and, most recently, through using data to drive efficiency and remove barriers to data interoperability.[footnote 23]

The UK Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) is the biggest public service department. It administers the State Pension and a range of working-age, disability and ill-health benefits to around 20 million claimants and customers. Many of these services are already moving to online provision, including, most notably, Universal Credit (also referred to as UC).[footnote 24] The Job Entry Targeted Support programme[footnote 25] was provided almost entirely online due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

1.2. Research objectives and questions

DWP commissioned RAND Europe to review and supplement the evidence base around the impacts of moving services online, through analysing the experiences of other public and private sector organisations. The evidence collected through this review can therefore inform strategic and operational decisions around the design of DWP digital services.

The review addresses a number of research questions, grouped into four areas of interest: 1) the impact of online provision of services on costs and savings; 2) the impacts of digitalising services on customer experience; 3) the wider societal impacts of shifting services online, even if these are more difficult to quantify; and 4) lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic.

To respond to these questions, RAND Europe undertook a literature review known as a quick scoping review, complemented with additional searches and interviews with a small number of stakeholders in the UK and abroad who have significant experience in the digitalisation of services.

The research was guided by the following 9 research questions:

- How can we best measure the financial, economic and social impacts of digitalising services?

- What is the cost trade-off between digital investment and savings on staff headcount?

- Are there successful examples of sharing or movement of data between different IT platforms, and what are the costs and benefits of this approach?

- Does including a digital channel enable more people to claim a benefit or service?

- Does a successful channel mix vary at different points of the customer journey, and how does this vary for groups with different protected characteristics?

- Learning from accelerated digitalisation due to COVID-19, are there any consistent emerging and sustainable ‘wins’ which could be considered for implementation in DWP services?

- How have organisations managed to shift customers onto online channels, and are customers who moved online during COVID-19 continuing to use online channels?

- What are the human and cost implications from customers having to use a digital channel where using another channel would mean a substantially improved outcome?

- What are the costs and customer experience levels of a successful channel mix, and how did organisations develop and establish a mix that worked for their customers?

Table 1 summarises how the structure of the report corresponds to the research questions.

Table 1. Mapping of research questions to report sections

| Research questions | Corresponding report sections |

|---|---|

| 1. How can we best measure the financial, economic and social impacts of digitalising services? | 2.1. Digitalisation activities that organisations invest in to achieve savings. 2.2. Measuring the financial, economic and social costs and savings of digitalising services. |

| 2. What is the cost trade-off between digital investment and savings on staff headcount? | 2.3. Potential costs and savings related to staff and service delivery. |

| 3. Does including a digital channel enable more people to claim a benefit or service? | 2.1. Digitalisation activities that organisations invest in to achieve savings. 2.3. Potential costs and savings related to staff and service delivery. |

| 4. What are the costs and customer experience levels of a successful channel mix, and how did organisations develop and establish a mix that worked for their customers? | 2.4. Costs and savings implications of failed digital channels, digital channel mixing and interoperability. 3.1. Strategies used to shift customers onto digital channels. |

| 5. Does a successful channel mix vary at different points of the customer journey, and how does this vary for groups with different protected characteristics? | 3.2. Factors affecting the customer experience of digital services. |

| 6. What are the human and cost implications from customers having to use a digital channel where using another channel would mean a substantially improved outcome? | 2.4. Costs and savings implications of failed digital channels, digital channel mixing and interoperability. 4. Social impact of digitalisation and learnings from COVID-19. |

| 7. Are there successful examples of sharing or movement of data between different IT platforms, and what are the costs and benefits of this approach? | 2.4. Costs and savings implications of failed digital channels, digital channel mixing and interoperability. 4 Social impact of digitalisation and learnings from COVID-19. |

| 8. Learning from accelerated digitalisation due to COVID-19, are there any consistent emerging and sustainable ‘wins’ which could be considered for implementation in DWP services? | 4. Social impact of digitalisation and learnings from COVID-19. |

| 9. How have organisations managed to shift customers onto online channels, and are customers who moved online during COVID-19 continuing to use online channels? | 3.1. Strategies used to shift customers onto digital channels. 4. Social impact of digitalisation and learnings from COVID-19. |

1.3 Research methodology

To address the research questions above, the study used a QSR of the literature complemented by stakeholder interviews.

QSR was chosen over more systematic approaches to evaluating evidence (i.e. systematic review, rapid evidence assessment) because of the broad scope of the research and the fact that systematically appraising the evidence was not a key consideration.[footnote 26] The choice of QSR was also informed by pragmatic considerations about the timeline of the research, which took place between January and March 2022.

The literature search was limited to sources published between 2018 and 2022, and the geographical scope was limited to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries and non-OECD countries with distinctive examples of digitalisation (e.g. Singapore). The chosen time frame reflected our initial practical limitation of examining only 50 sources; a longer timespan would have increased the number of articles to analyse beyond our capacity for this study. Keyword searches in Google Scholar and Web of Science yielded 300 sources. We screened the titles and/or abstracts for relevance and ultimately selected 63 of these 300 sources for more detailed review. We excluded 19 of these 63 sources due to insufficient relevance or lack of access, and 44 sources proceeded to the analysis stage.

While it takes a structured approach, a QSR does not follow the same level of rigour as a systematic review or rapid evidence assessment. It is possible that certain relevant sources were missed, particularly those published before 2018, given the time frame selected for the study. The focus on English-language sources may, likewise, have resulted in certain findings being excluded.

We looked for evidence about the impact of digitalising welfare services in contexts similar to the ones in which DWP operates. However, the evidence presented in the literature covered digitalisation of services in wider areas, e.g. digitalisation of healthcare services. This report presents examples and evidence that were most relevant to the DWP context and which could inform digitalisation of welfare services beyond the healthcare context.

To supplement data obtained through the scoping review, we had planned to conduct up to 30 stakeholder interviews with public authorities undertaking similar services in the UK or in other countries (focusing on the local authority level in the UK) and with private organisations (in the UK and beyond) familiar with the digitalisation of services in their respective organisations. The objective of these interviews was to better understand the context in which digitalisation happens in organisations (aims and motivations, barriers, drivers) and to illustrate findings from the QSR.

We reached out to more than 50 organisations (via email and phone) and were able to secure 6 interviews (including one featuring a group of four people) with local authorities in the UK and public authorities in other countries in Europe. Our requests for participation in the research did not generate interest among private sector organisations, which might be explained by the lack of incentive for these organisations to share information about their experience in this area. The implications of these limitations for the quality of the evidence base for this research are likely limited, given that our research relied primarily on the QSR and that our expectations for the interviews were to be able to further explore what was discussed in the literature and to illustrate findings from the literature.

The study draws on a small number of in-depth interviews; different or additional findings might have emerged if the pool of interviewees had been larger. This limitation should be kept in mind when using the findings from this research and for understanding their implications for digitalisation of services, for the DWP and for any other organisation contemplating digitalisation of their services.

Given that evidence gaps remained with this approach, we agreed with DWP that we would fill in remaining significant evidence gaps with additional literature searches in Google Scholar and snowballed from existing sources (i.e., identified other relevant sources from the citation list). These searches were not subject to the same time and geographical limitations as those conducted initially,[footnote 27] but sources which satisfied them were ultimately preferred.

Further details about the methodology are provided in Appendix A.

1.4 Structure of the report

Drawing on evidence collected from the QSR and stakeholder interviews, Chapter 2 summarises evidence related to costs and savings and Chapter 3 considers impacts on customer experience. Chapter 4 focuses on the societal implications of digitalisation and any lessons learned from the COVID-19 experience. Finally, Chapter 5 summarises the main findings of this review and draws key implications from the research. Appendices A and B present the protocols for the QSR searches and for the interviews, respectively.

2. Costs and Savings

Having a clear view of the potential costs and savings of digitalising services is vital to the successful implementation of any digitalisation project. This chapter outlines which digital activities organisations are investing in to achieve savings (section 2.1). This will be followed by considering how the financial and economic costs and savings of digitalising service are measured (section 2.2). Costs and savings related to staff and to service delivery will each be discussed in section 2.3. This will be followed by an overview of the costs and savings associated with digital channels, particularly the costs and savings implications of failed digital channels, digital channel mixing and interoperability (section 2.4). Key considerations for the DWP and other organisations to take into account when thinking about the costs and savings associated with the digitalisation of welfare services are highlighted throughout and are summarised in section 2.5.

2.1 Digitalisation activities that organisations invest in to achieve savings

Digitalisation of the public sector and of welfare services has been seen as a way to increase the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of service provision in light of new pressure on services and increased financial constraints. As explained by Larson et al., “the contention is that by using technology in welfare services, it can help secure the continued economic stability of the welfare state”.[footnote 28] In addition to the pressure on services from societal challenges, such as an ageing population, the public sector has to contend with increased demand associated with the rise in the cost of living, as well as, most recently, the COVID-19 pandemic.[footnote 29] Using technology in public service delivery improves how service users communicate with providers because these technologies are information-processing tools.[footnote 30] In general, digitalisation is expected to result in the improvement of public sector service delivery, including increased internal efficiency, better information sharing, better-informed decision making and innovation.[footnote 31] These service and process improvements may result in cost savings, which are achieved by allocating resources more efficiently.[footnote 32] In summary, as explained by Løberg, both researchers and governments often consider digital service provision to be more efficient than traditional service provision,[footnote 33] with these efficiency gains resulting in increased savings and reduced costs.

Regarding the specific type of activities that organisations are investing in to achieve savings, Ranerup and Henriksen’s study describes how e-government[footnote 34] activities can be divided into a ‘first wave’ – mainly focused on streamlined e-service and the horizontal integration of data (combining similar data types) and vertical integration of data (merging different data types) and a ‘second wave’ – where the focus is shifted to automating processes, such as decision making in which a computer program or ‘robot’ acts as the case manager for decisions.[footnote 35] This can also be understood as corresponding with a shift from the simple digitisation of activities to an emphasis on digitalisation. In practice, organisations working towards introducing ‘second wave’ service provision have focused on activities such as the handling of applications for social assistance and the offering of economic support using partly automated application processes.[footnote 36]

Our findings show a stronger emphasis on ‘second wave’ forms of digitalisation where organisations are investing in their services to achieve savings. For example, in highlighting the categories of digital technologies being used by public sector organisations in the EU, Eurofound’s study focused on the automation of work, the digitalisation of processes and the coordination of service provision using digital platforms.[footnote 37] Here, automation of work is described as focusing on:

- the replacement of human labour input by machine input for some types of tasks using algorithmic control of machinery and digital sensors. These types of tasks include those related to routine, repetitive administrative tasks (such as sending reminders and facilitating payment) and to customer support (for example, through the use of ‘chatbots’)

- the digitalisation of processes focused on the use of sensors to translate (parts of) processes into digital information, including through the use of technologies such as the internet of things (IoT), virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR)

- the use of platforms for the bringing together service users and providers; in some instances, platforms may use technologies such as blockchain[footnote 38] and cloud computing[footnote 39]

Out of each of these ‘second wave’ technologies, the automation of services is cited as the most common trend in public sector digitalisation.[footnote 40] As explained by Ranerup and Henriksen, “in the public sector, civil servants and clients find themselves in an environment where automation and robot technology can be expected to make dramatic changes”.[footnote 41] An example of this is the changes to social service delivery in Trelleborg, Sweden (Box 1), which provides a useful illustration of how financial aid can be delivered using automated decision making.[footnote 42]

Trelleborg Municipality introduced RPA in 2016 which, by 2017 handled 70% of applications for social assistance benefits, made 41% of decisions and processed payments.[footnote 43] This use of RPA resulted in qualitatively self-reported increased accountability, decreased costs, and enhanced efficiency within the Trelleborg Municipality.[footnote 44]

Box 1 Digitalisation of municipal social service delivery in Trelleborg (Sweden) [footnote 45], [footnote 46]

Trelleborg is a city of 43,000 inhabitants located in southern Sweden. Like other municipalities in Sweden, Trelleborg offers a wide range of welfare services around childcare and education, and it also processes applications for financial aid. Trelleborg introduced fully automated decision making in relation to financial aid applications in 2016.

The type of technology used in Trelleborg is robotic process automation (RPA), which means that the process (and, as part of it, decision making) is handled by a robot.

One year after introducing it, Trelleborg’s RPA handled most (70%) applications for social assistance benefits, made 41% of decisions and processed all related payments using this automated decision making.

The municipality reported that the use of RPA resulted in increased accountability, decreased costs and enhanced efficiency of the services.

The use of RPA in Trelleborg also resulted in negative experiences for staff in relation to trusting a machine to make decisions in areas where staff value their professional judgement about priorities and circumstances. Staff also reported issues related to ensuring transparency in decision making and data protection.

In terms of costs, the municipality reported a reduction of the cost of social assistance. However, in this instance, the Swedish Labour Market Agency spent a further 600,000 Swedish crowns (£49,128) per year after the launch of the RPA system, which suggests that ongoing maintenance, repair and improvement costs should be taken into account while calculating cost reductions.

2.1 Digitalisation activities that organisations invest in to achieve savings (continued)

This echoes findings by Deloitte which, based on responses from more than 400 individuals across various industries globally, reported how shifting mundane, labour-intensive, repetitive tasks from humans to robots through RPA resulted in 92% improved compliance, 86% improved productivity, 90% improved quality and 59% cost reduction.[footnote 47] However, the implementation of RPA technologies does incur costs, with 25-30% of the total costs assigned to licensing costs (which in 2021 ranged between £11,500 and £38,000 for a single ‘bot’, or unit) and the remaining 75% of the costs consisting of yearly RPA license renewal fees; training or hiring of staff; consulting costs for implementation; infrastructure set-up; third-party integrations; cost of complementary software (e.g. process mining and process discovery software); and costly RPA repair, improvement and modification cycles.[footnote 48] These cost categories are likely to differ at various stages and time horizons in the RPA implementation process.

In addition to these cost considerations, it should be noted that RPA roll-out is not a cure-all solution. Despite some reported initial gains, a further study by Ernst and Young (EY) indicated that 30-50% of all RPA initiatives have failed, in part due to coding errors[footnote 49] or cybersecurity breaches.[footnote 50] An example of an RPA technical failure recorded by EY is an instance where “a telecom company deployed bots for managing its complaints-handling process. However, coding errors led to many grievances being diverted to an incorrect queue, resulting in a backlog of complaints”.[footnote 51] To increase the likelihood of success, RPA implementation strategies should consider 1) the need for the right upfront design (which can significantly reduce RPA maintenance and support costs); 2) cross-functional collaboration between service provision and IT functions and; 3) the need to improve and optimise processes before automating.[footnote 52]

In addition to these possible technical challenges, the use of RPA in a welfare service setting has further social considerations that need to be kept in mind. In Trelleborg Municipality, while the use of this technology led to reported efficiency gains, it also resulted in negative experiences for staff. These negative experiences were reported in the areas of

- exercising professional knowledge where decisions requiring professional judgement became automated

- safeguarding service user trust through data protection (not publicly disclosing certain categories of information) and the perceived lack of transparency

- cost reduction and the desirability of sharing the design costs of the model with other local governments[footnote 53]

These negative experiences have been attributed to an observed tension in value relationships (conflict between different values, such as professionalism, efficiency, service and engagement), namely between automated decision making used to make routine decisions so staff can prioritise more-complex tasks versus lack of professional discretion in the final decisions.[footnote 54] Tensions were also observed in the use of RPA having resulted in a shift from helping citizens by facilitating payments of welfare benefits, to encouraging them to find work.[footnote 55] These tensions highlight how automation also has negative effects, resulting in the need to assess efficiency gains against any indirect negative consequences for staff and service users.

Another example of the automation of services is provided by Lindgren et al. who describe how “new opportunities for digitalisation of public service provision associated with data mining, machine learning, sensor technology, and service automation have been discussed with great optimism.”[footnote 56] This is because these emerging digital technologies may “fulfil the primary goals for digital government which include improving efficiency and service quality by reducing service lead times and offering seamless service provision across organizations.”[footnote 57] In Slovenia, for example, introducing a new information management system (known as IS CSD2) significantly reduced abuses of the welfare system through activities such as supporting data aggregation, decision making, standardised display of documents and the automatic calculation of social transfers, which enabled the correct payment of transfers.[footnote 58]

Despite progress in introducing new digital technologies in service delivery, in practice, these new technologies are not widely used and therefore the evidence on their implications for service delivery is still evolving. For example, despite the promises of the use of ‘welfare technologies’ to promote digitalisation in Scandinavian countries, only a few of these welfare technologies are being offered by local municipalities and care homes.[footnote 59] Similarly, Cepparulo and Zanfei noted that research into e-government focuses on a narrow set of public services:

- services generating income for the government (such as taxation and customs)

- registration services (such as ownership, birth and marriage)

- permits and licences (including building permits, passports and diplomas)[footnote 60]

An example of this narrow use of digitisation was provided by one interviewee, who explained how the sending of digital emails (about 217 million per year) instead of paper letters resulted in estimated savings of €200 to €400 million for their public service since the introduction of email correspondence.[footnote 61] This observed focus on a narrow set of public services is supported by Špaček and others’ study on the digitalisation of the core administrative services in a selection of Central European countries. Their findings show that, overall, digitalisation is relatively uncommon and, in most cases, is focused on 10 types of service areas: obtaining new IDs and travel documents; registering a new address; obtaining or changing a driving license; registering a car; solving a waste-disposal issue; paying local taxes and fees; paying for local transport; making submissions to local administration (complaints, petitions etc.); participating in local decision making; and applicating for childcare.[footnote 62] This finding on the types of services covered by public sector digitalisation was supported by one interviewee, who mentioned transactions done online, including payments, as a key digitalisation initiative within a local authority context (see Box 2),[footnote 63] echoing the findings that digitalisation is currently occurring primarily in transactional public services.

Box 2 Digitalisation at county council level (UK)

This county council covers over 1 million residents, and with the natural progression of digitalisation, the county council seeks to continually implement digital change to an array of different services.

The main aspects of digitalisation in this county council are related to work, public reporting, development applications, active travel and road maintenance. Licensing for services have become an integral digital innovation for the county council, with manual handling of paperwork and license processes having been removed and digitalised.

For many years, thousands of services were applied for physically, by fax. In 2014, this became a digital process. As of May 2021, 100% of these applications became digital, with users providing positive feedback on the efficiency, ease and time savings as a result of this new process. In addition, this saved a great deal of the county council effort, removing the need for administrative teams to process the applications and enabling them to redirect their effort elsewhere.

In order to balance user-friendliness, offline versions of the county council services remain open to residents who are unable to complete applications online. The offline services also evolve alongside online versions.

While there are no fully measurable cost savings the county council can report on, there have been assumed savings through better use of time and increased process efficiency. Alongside this, high customer satisfaction rates have led the county council to conclude that their digital transition is an ongoing success.

2.1 Digitalisation activities that organisations invest in to achieve savings (continued)

Overall, organisations’ customer-related digitalisation activities can be described as falling into three categories:

- transactions (e.g. registering for elections, reporting a problem, paying a bill)

- interactions (e.g. obtaining advice, public consultations, petitioning)

- information provision (e.g. swim times, leaflets, web pages)[footnote 64]

All three of these categories are fulfilled using a combination of traditional and digital communication channels.[footnote 65]

This focus on transactions indicates that less attention has been paid to more-complex interactions and information provision in public sector digitalisation initiatives. While it focuses only on Hungary, Romania and the Czech Republic, the study by Špaček and others is relevant to the DWP’s context. First, it provides a useful overview of the types of activities public sector organisations are investing in to achieve savings, by showing the 10 main digitalisation categories of core administrative services, as highlighted above. These focus on similar ‘macro-categories’ to those mentioned by Cepparulo and Zanfei[footnote 66] and by one interviewee.[footnote 67] This suggests that the digitalisation of more-complex services, which go beyond simple transactions, such as those in welfare provision, is currently still limited. Second, the study by Špaček et al. found that the digitalisation of core administrative services for citizens may be determined by the national approach to e-government policy, the level and readiness of legislation for digitalisation and the way the service delivery is organised (centralised, decentralised or mixed).[footnote 68] This need for a national approach and the need for state-supplied infrastructure is further discussed below.

Considerations for the DWP or other stakeholders in similar positions: These findings indicate that there is a disconnect between interest in the use of more advanced digital technologies (such as AI and cloud computing), on the one hand, and the reality of the types of services that are being digitised and digitalised (which are still largely transactional), on the other hand. Organisations could consider taking a measured and incremental approach. They could first focus on ensuring adequate digitisation, and then work towards transactional digitalisation and, finally, more interactional digitalisation. Taking this incremental approach means organisations can consider the use of technologies such as RPA at appropriate times – technologies that, while providing considerable efficiency gains, have important cost and service delivery implications.

2.2 Measuring the financial, economic and social costs and savings of digitalising services

2.2.1 Measuring financial and economic costs

The ability to measure the financial and economic impact of digitalisation is key to understanding the costs and savings associated with digitalisation. Various methods of measuring the costs and savings of digitalising services were found in the reviewed literature. The first of these is system-level analysis, which uses a whole-systems approach[footnote 69] to predict the value of digitalisation. A study that illustrates how this form of analysis can be used to assess the financial impact of digitalising a service was conducted by Turner et al..[footnote 70] The authors conducted a system-level analysis to predict cost-effectiveness (comparing the relative costs and outcomes of different courses of action) of a shift to online services in the testing for sexually transmitted infections (STI) in London.[footnote 71] Despite this study being specific to a healthcare context, there are lessons relevant to quantitatively assessing the costs and savings associated with a shift to digital service provision.

This study showed that measuring the financial and economic impact of digitalisation requires routinely collected, anonymised and retrospective data, such as the number of digital services users, demographics of these users, and types of services being accessed.[footnote 72] In this study, this was done for both digital (online) and non-digital (in-person) services at two data points – before the shift to the digital service (which was the study’s baseline) and after the introduction of the digital service. This approach was taken to comparatively assess, track and monitor the financial effects of introducing digital services. A key data point for Turner et al.’ study was the cost per service. This was calculated using data on the primary tariff (meaning the cost of delivering that care on its own), as well as an additional tariff (meaning the cost of delivering that care alongside another, more expensive activity).[footnote 73] The second consideration relates to the application of a whole-systems approach.[footnote 74] In this study, the authors used the database (of routinely collected, anonymised and retrospective data, as explained above) to evaluate the pattern of service use across two inner London boroughs (Lambeth and Southwark). It considered the differences and changes in costs per service between digital and in-person services, as well as other factors that impacted access to the services. In addition, to compare the service in other urban versus rural environments, the study collated summary data from three other areas that use the same online service as examples of different urban and rural areas. They coded the types of services being accessed online and in person and made use of scenario analyses to model how changes in different variables affected the cost per service in both the digital and the in-person environment. The study projected different costs between urban and rural areas due to different levels of STI, different barriers to service use and variations in clinic budgets (including the applicability (or not) of London tariffs) across the country. The estimated cost per diagnosis online for southeast London for quarter 1 of 2017 was £732, compared with a figure of £545 for ‘rural with hub town’ areas.[footnote 75] This suggests that a system-level analysis can be used to consider how costs and savings might vary in different contexts.

The costs and savings implications of digitalisation can also be considered using cost-effectiveness analysis. For example, a study by Aspvall et al.[footnote 76] assessed the cost-effectiveness of internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy compared with in-person cognitive behavioural therapy for children and adolescents in Sweden. The methodology of the study included collecting cost data at different stages of treatment (including before treatment) and then comparing differences in costs and health outcomes between the internet-delivered and in-person groups from the perspectives of healthcare professionals, the health care sector and wider society.[footnote 77] In the case of the cost-effectiveness of internet-delivered versus in-person cognitive behavioural therapy, while the shift to digital services provision resulted in a lowering of cost, it also resulted in a decrease in the effectiveness of the intervention directed at the target care group.[footnote 78] This is linked to concerns expressed in the literature about cost reductions linked to digitalisation possibly resulting in a reduction of the quality of service provision.[footnote 79]

Measuring costs and savings can also be done using a software development and design science approach. This method is seen as useful in instances where the rapid design and implementation of digital platforms and services is needed. To illustrate, this approach was taken by Lapão, et al., who took a design science approach to assess the implementation of digital monitoring services during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with chronic diseases in Portugal.[footnote 80] The design science approach uses Scrum, an agile project management method that collects feedback from end users at the end of each iteration of the software design, and prioritises new features to reduce risk and extract maximum value.[footnote 81] This methodology provides a viable means of assessing the financial and economic costs and savings of digitalisation by allowing for the testing of software for value based on pre-defined goals. The key point to consider from this methodology is the need to consider the link between 1) the proposed technology or software and 2) the pre-defined goals and desired outcomes when assessing the costs and savings associated with digitalisation.

The last methodology used to measure costs and savings of digitalisation identified in the literature is case study methodology. The ‘Digital Efficiency Report’ published by the UK government’s Central Digital and Data Office in 2012 assessed the savings made from the digitisation of transactional services offered by the central government using case studies.[footnote 82] This report defined transactional services as services that involve an exchange of money, goods, services, permissions, licences or information between the government and a service user (from paying car tax to applying for a passport) resulting in a change to a government system.[footnote 83] This analysis used case study methodology in which a sample of 17 services was selected. Each of these services was categorised using 4 significant factors of savings potential – volume of individual transactions per year, service function (e.g. requesting a benefit or grant), customer type and current level of digital take-up – with data about the impact of each being collected to arrive at final costs and savings estimates. Estimates on the number of digital transactions by channel, as well as unit cost ratios by channel and by department, were based on data acquired from published departmental and agency accounts.[footnote 84] This method showed the resulting projected total annual savings (fiscal and cost recovery) of digitisation within the UK public service. Significantly, this analysis shows that it is effective to isolate and then aggregate costs by service function when considering the total costs and savings of shifting to digital services. Also significant is the focus of the ‘Digital Efficiency Report’ on digitisation rather than on digitalisation, highlighting how cost estimates of the shift from analogue to digital are more easily arrived at than estimating the cost and savings implications of digital technology in the mode of service delivery. This finding was reiterated by one interviewee, who highlighted the difficulty calculating costs and savings because digitisation and digitalisation activities have happened over many years.[footnote 85]

These challenges in measuring the costs and savings of digitalisation are well documented.[footnote 86] For example, while an early (2010) study measuring the financial impact of ICT investment in Slovenia’s tax system showed that ICT expenditure is higher than cost savings for tax administration and taxpayers (despite showing several non-financial benefits), these values were based solely on rough estimates.[footnote 87] These challenges and constraints in the measurement of the costs of digitalisation are made worse because it is difficult to decide which metrics should be monitored (often with control budgets[footnote 88]). Kotarba argues that more work needs to be done to help find the most appropriate data points to assess digital performance over time.[footnote 89] This challenge in measuring the costs and savings of digitalisation has resulted in evidence gaps in the research around this subject. For example, as noted by Cepparulo and Zanfei, initial studies examining the costs of digitalisation have so far focused on a relatively narrow set of electronic service provision, while they have devoted much less attention to quantitative analysis of services that respond more directly to users’ needs, including e-health and e-procurement.[footnote 90] This implies a limited understanding of the existing and potential impact of digital technology on providing frequently used services affecting the everyday life of individuals, households and companies.[footnote 91] The overall effect of this is limited actionable evidence on the financial effects of digitalisation on the public sector. As explained by Wright, while digitalisation in the public sector has involved large levels of public investment, it has yielded few tangible results so far.[footnote 92] The lack of evidence of the benefits of digitalisation is a barrier to the wider adoption of new digital technologies.[footnote 93] Finally, these measurement challenges are more pronounced (but also most necessary to overcome) in the welfare context.[footnote 94] Here, it has been noted that measuring and quantifying costs and savings and the focus on “efficiency, predictability, calculability and control over uncertainty poses a risk of watering down the core values of welfare technology”, with implications on various groups of customers.[footnote 95]

Considerations for the DWP or other stakeholders in similar positions: These findings highlight how accurately assessing costs (including costs per service) might prove challenging in the context of DWP’s work given the complex nature of the services provided. Some costs and savings may be difficult to quantify, especially given the interconnected nature of some of the services. DWP will likely have to use proxies for some of the necessary data points and could consider focusing on a service-by-service approach to measurement. This may help to get an accurate financial and economic assessment of digitalising a range of services. Finally, the link between service costs and service quality must be kept in mind, particularly when serving vulnerable customers.

2.2.2 Measuring social costs

In addition to capturing financial and economic costs and savings of digitalisation, attention must also be paid to measuring the social costs of digitalisation. As highlighted by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN/DESA), enabling affordable access to the internet for everyone and investing in digital skills is needed to ensure that no one is left behind, particularly in the era of COVID-19-accelerated digitalisation of essential public services.[footnote 96] Factors such as location, income, age, sex, ethnicity and disability status are significant predictors of access to ICTs and the internet, and therefore need to be taken into account when assessing the social costs of digitalisation. The urban versus rural gap, where the percentage of households with access to the internet at home in urban areas (72%) is almost twice that in rural areas (38%) is particularly prevalent, in developed and less developed countries alike.[footnote 97]

Similar discrepancies are seen in relation to older people across all regions – for example, in the United States, 27% of individuals aged 65 years and over and in the UK, 46% of individuals aged 75 years and over do not use the internet[footnote 98] – and in relation to people with disabilities, who face inequalities and additional barriers in accessing the internet.[footnote 99] Lack of engagement with digital services and other factors, including affordability and accessibility of ICT devices, programmes and websites, are discussed in more detail in Chapter 3. It is important to factor these social costs into the overall cost and savings assessment of the digitalisation process. As explained by one interviewee, in line with the UK’s levelling up agenda, equality and access to digital infrastructure are fundamental for people to participate in modern life.[footnote 100] However, according to the interviewee, issues of affordability and skills are not being adequately addressed at the national level (with social housing particularly lagging behind in digital infrastructure), and there is no adequately coherent national plan or responsibility for this.[footnote 101] The UN/DESA report highlights the role of national and local governments in ensuring a framework for reducing the digital divide and increasing digital inclusion through considering access, affordability, skills and awareness.[footnote 102] This means that these categories of social costs need to be considered at the broader, national level rather than at the level of individual organisations, because these social costs have to do with underlying national digital infrastructure and broader social policy.

Despite these challenges, some local authorities in the UK are making considerable strides in promoting digital inclusion, for example Connecting Cambridgeshire, led by the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Combined Authority (see Box 3).

Connecting Cambridgeshire, in partnership with organisations including the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development and the Department for Digital Culture Media and Sport (also referred to as DCMS), seeks to improve “digital connectivity to drive economic growth, help businesses and communities thrive, and make it easier to access public services”.[footnote 103] Connecting Cambridgeshire’s superfast broadband roll-out has brought high-speed internet access to more than 98% of homes and businesses,[footnote 104] showing how local authorities can play a role in taking onboard some of the social costs of digitalisation, particularly through leveraging strategic partnerships.

Box 3 Digitalisation in Cambridgeshire (UK)

Connecting Cambridgeshire is a programme hosted by Cambridgeshire County Council, which works with local authorities, government bodies and external organisations to improve Cambridgeshire and Peterborough’s digital infrastructure for businesses, communities and public services.

A range of services on the Connecting Cambridgeshire network have become digitalised. Some of these are resident parking permits, library services, fines, and elderly and vulnerable citizen support. These digital services sit alongside non-digital alternatives to increase user-friendliness and to account for services which require in-person care.

The decision to digitise was reached during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the UK government began to incentivise digitisation – the biggest drive being cost savings. With added pressure for councils to reduce costs, digitisation became a priority to Cambridgeshire County Council.

Rolling out these systems required standard practices of soft-testing, disaster recovery testing and standard testing. This testing had to be extensive, as the nature of the service is vital (Connecting Cambridgeshire had to rely on creating very good digital systems).

The implementation of digital services by Connecting Cambridgeshire has led to a reduction in staffing, which aids in cost savings; however, this has caused added pressure within local authorities, as different skill sets are now required to oversee digital services. Finding staff with the necessary skillset is challenging, as already low local authority budgets can act as a barrier to employ digitally skilled workers and re-train existing staff.

Associated with digitalisation is the danger of technological exclusion. The county council has tried to rectify this issue by helping to support citizens’ digital skills, but the issue remains prominent.

The Connecting Cambridgeshire programme recognises that, in the future, it may be more effective to re-engineer processes instead of simply replacing offline systems with a digital format – which may be clunky and less user-friendly – however, further opportunities to do so would require a larger upfront investment in system implementation and transformation.

2.2.2 Measuring social costs (continued)

Considerations for the DWP or other stakeholders in similar positions: Organisations such as the DWP should keep in mind the extent and nature of the social costs associated with the digitalisation of public services and factor these into their overall costs and savings analyses. In addition, organisations such as the DWP could seek to foster horizontal and vertical partnerships with local authorities and other national authorities to advocate for, shape and arrive at a unified, national approach to digital inclusion in order to better account for and meet the social costs (including those to do with affordability and access) related to the digitalisation process.

2.3 Potential costs and savings related to staff and service delivery

The need to assess the costs and savings associated with the digitalisation of welfare services is well documented.[footnote 105] While these costs and savings can be assessed across different dimensions, this study particularly focused on assessing the costs and savings related to staff and to service delivery. Considering the cost implications of these two dimensions is essential in a public sector department such as the DWP, which provides people-led (staff) and people-oriented (customers) services.

2.3.1 Staff-related costs and savings

Our findings show that identifying the staff-related costs and savings associated with digitalisation is complex and multi-faceted. On the one hand, digitalisation is seen as a solution to labour shortages,[footnote 106] and on the other hand, digitalisation is cited as one of the causes of staff job losses.[footnote 107] The reviewed literature reiterates the need for staff training and staff buy-in to achieve any cost savings or benefits associated with the digitalisation of welfare services. Overall, there is evidence that digitalisation can lead to a reduced staff headcount (and related costs). However, this should be weighed against other staff-related considerations (such as training costs) and against the impact on the wider economy, particularly where unemployment due to digitalisation might increase costs for the taxpayer (and, indeed, the DWP).

Most evidence on the staff-related costs and savings of digitalisation is focused on the need for staff training and support to realise the savings of digitalisation. As explained by Tomičić Furjan et al., any potential staff-related savings of digitalisation might fail to be realised without adequate training and buy-in from staff, because employees challenge the use of any new technology if they lack the “time, competencies, [or] motivation” to adapt or if they are concerned about “being replaced”.[footnote 108] These fears are heightened by concerns that new technologies are being used for worker surveillance and performance monitoring, as well as increasing working time and extending job tasks.[footnote 109] To address possible negative attitudes towards technologies, it is suggested that employers should:

- explain the technologies used

- provide training and should allocate time for learning

- develop the ability to use the technologies and facilities

- foster support for the use of new technologies[footnote 110]

Specifically, staff buy-in can be supported by involving staff in the design and potential implementation of new digital platforms, and to provide feedback on the functionality requirements.[footnote 111] [footnote 112] There are some financial implications to ensuring these aspects of digitalisation are put in place. As explained by one interviewee, the costs of setting up devices, skills and training in the use of technology amounted to £5 million for a local authority since the start of the pandemic, in March 2020, with additional one-off costs incurred through the creation of an engagement team hired to up-skill the communities in digital skills and improve confidence to support the use of public services online.[footnote 113]

In general, staff training costs vary depending on the industry, training needs, job role, mode of training (online or in person) and format (professional qualifications, apprenticeships etc.). A 2018 survey of 180 human resources professionals from various industries across the UK showed that, on average, employers invested around £42 billion in training per year, with an average spend of £1,530 per employee.[footnote 114] However, given that the average employer spends about £3,000 and 27.5 days to hire a new worker[footnote 115] – almost double the average training costs – training rather than new hiring could be the more cost-effective option. Similarly, there is evidence that digitalising services can contribute to reductions in staff-related costs. In the ‘Digital Efficiency Report’, staff costs related to reductions in employee numbers were projected to account for 78% of the total savings of digitisation.[footnote 116] Further work citing staff savings due to digitalisation includes Raina et al., who, in a study on telemedicine,[footnote 117] found that higher use of the digital service (in this case patient attendance) resulted in more efficient use of staff time and resources. This was because prior to the introduction of the digital service, 53% of scheduled visits were either cancelled or were ‘no-shows’. After the introduction of the digital service, there was a reduction of the ‘no-show’ rate by nearly half (to 29%), ultimately leading to a reduction in costs and increased efficiency in the use of staff time when offering the service.[footnote 118]

In addition to saving on staff costs, digitalisation is seen as one of the ways to address labour shortages in the social services sector. An example of this is the use of smart assistants to increase the capacity of the personal and social care workforce.[footnote 119] However, introducing digital services, such as smart assistants, led to redundancies among public sector staff.[footnote 120] A report commissioned by Public Services International (PSI) found that “cost-cutting driven digitalisation tends to replace and slash public service jobs.”[footnote 121] While the evidence in the literature highlights these findings related to staff costs, the causal link between digitalisation and staff redundancies is not always obvious. As explained by one interviewee, “it is hard to attribute reductions in staff headcounts to digitalisation – since it began in 2010 – council has reduced its headcount by 3,000 posts … there is an impact on headcount, but it is part of a much broader reduction in headcount over last 10 years for other reasons too.”[footnote 122]

Considerations for the DWP or other stakeholders in similar positions: These findings indicate that while they are digitalising their services and assessing the overall staff-related costs and savings, organisations should factor in the costs of technical support and training, as well as the costs of putting in place other mechanisms to ensure that all staff can effectively use the technology. Organisations will also need to ensure that there is buy-in in the digitalisation process at the staff level and to put in place mitigation strategies to address any staff concerns in order to fully realise possible staff-related cost savings associated with digitalisation. While digitalising, organisations should also consider their current staffing position in terms of staffing requirements (surplus or deficit), as well as the types of services that various members of staff are responsible for (in terms of the extent to which they can and should be digitalised). In parallel, they should consider the costs and savings associated with digitalisation, as these factors are inextricably linked.

2.3.2 Service-related costs and savings

In addition to having implications for staff-related costs and savings, digitalisation has financial and economic impacts related to the scope and nature of service delivery.

We found that digitalisation can result in reduced costs and increased savings in service delivery, particularly in the healthcare context (although this view is contentious and under ongoing debate and review)[footnote 123] [footnote 124]. For example, introducing telemedicine indirectly resulted in a reduction of hospital operational costs by decreasing the rate of hospitalisation from 5.7 to 2.2 days annually per patient through providing an alternative channel to access preventive medical and health consultations from general practitioners.[footnote 125] Similarly, Heoponiemi et al.’ study on online healthcare showed that ICT in health care is perceived to decrease costs and improve patient outcomes by “transforming healthcare to being more proactive, preventive, and person-centred instead of being reactive and hospital-centred.”[footnote 126] Timeliness and efficiency were the most reported positive aspects of virtual care solutions, leading to system savings in the healthcare context.[footnote 127]

Similar savings have been noted in the social care context. In the UK, several local authorities found that digitalisation in the form of technology-enabled care services can cut care costs and increase the efficiency of care services.[footnote 128] For example, in East Sussex, a telecare programme showed an approximate cost-savings value of £32 per client per week, for an estimated annual preventive savings of £589,000.[footnote 129] An additional example showing cost savings from digitalisation in a social care context is from the previously mentioned Trelleborg Municipality study, where digitalisation and automated decision making reportedly resulted in a reduction in the cost of social assistance.[footnote 130] Similarly, in neighbouring Norway, the use of welfare technology was found to reduce pressure on healthcare services by decreasing consultations, home nursing services and admissions to hospital.[footnote 131]

Additionally, it has been noted that, in some instances, digitalisation may lead to increased demand in the service that offsets the cost reductions associated with the shift to digital service delivery. This is illustrated by Turner et al., who found that moving to digital may lower the unit costs of a service (making it more cost-effective), however, in this particular instance, this also increased demand for that service. Their study found that with online STI testing in inner London, the total annual cost of the service increased from £2.87m (2014) to £3.09m (2016) even though there were decreases across the average cost per unit (from £66 to £61) and the average cost per diagnosis (from £660 to £644); the increase was the result of an increase in demand.[footnote 132] An increase in service demand as a result of digitalisation was also seen in a study examining how frontline workers in the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration (NAV) perceive digitalisation (specifically, electronic communication with clients). In terms of efficiency, staff found that while electronic communication saves them time, it also “makes them more available to clients”.[footnote 133] NAV uses an electronic communication platform, Modia, as its main channel for service provision. By providing frontline workers and clients with an online messaging function, Modia changes service provision in job-oriented counselling by providing the client with direct access to their frontline worker. In addition to using features similar to an online chat, the frontline workers use Modia as an electronic inbox and answer messages when available, increasing both access and demand.[footnote 134] This spur in the demand for services as a result of digitalisation means that there is a potential “resource trade-off between efficient services and available services”[footnote 135] that must be considered. The final service-provision-related costs to consider are costs related to procurement and the dependency on external providers without building in-house capacity and, when digitalisation projects are financed with private investment and public–private partnerships (PPPs), cost calculations are “often unrealistic due to regular underestimation of indirect and recurring costs.”[footnote 136]

Considerations for the DWP or other stakeholders in similar positions: In order to realise the potential service-provision-related cost reductions of digitalisation, organisations should consider the trade-offs between cost savings and increased demand for services brought about by digitalisation. They should also factor in the interaction between customer-centric approaches and costs when assessing the cost and savings impacts of digitalisations related to service delivery.

2.4 Costs and savings implications of failed digital channels, digital channel mixing and interoperability

2.4.1 Costs associated with the failure of digital channels

Digital channel failure occurs when the digital means of service delivery is unsuccessful in achieving its expected, pre-defined outcomes. The process of digitalisation is vulnerable to technical difficulties, particularly at the initial roll-out stage, which results in additional unforeseen costs, as has been previously discussed. There are numerous examples of failed digital channels across different industries, including in social services.

In Finland, the Virtu.fi telecare service experienced problems in delivering the technology and programmes due to issues with internet connection, while in Norway, technical issues were experienced in relation to digital welfare technologies for children with disabilities and their families, including set-up, coordination and synchronisation between devices.[footnote 137] Austria also experienced technical difficulties that negatively affected the acceptance of care robots by service users.[footnote 138]

These examples are consistent with reported digital channel failures in other sectors and industries, where inadequate change management, not hiring (or commissioning) the right personnel, the lack of clear goals and the prevalence of a ‘fail fast’ attitude to digital transformation are cited as some of the factors leading to digital channel failure.[footnote 139] The use of technology for technology’s sake (without a clear set of goals) in particular should be avoided by welfare organisations. To avoid such failure, the regulatory environment around digital technologies must be kept in mind. For example, the use of technology, such as video communication software, in a highly regulated industry should focus not only on how a software tool such as Zoom or WebEx can improve employee communication, but also on the compliance implications of the new software.[footnote 140] Commercial entities can take a ‘fail fast’ approach to digitalisation (exploring digital innovation by trying a variety of digitalisation endeavours in rapid succession and moving on to the next until they find one that works).[footnote 141] Digitalisation in public sector organisations, however, particularly those in the welfare sector, requires careful analysis and cannot be accomplished overnight, because digital channel failures in this sector have repercussions beyond the financial bottom line. Therefore, public sector organisations digitalising their services should consider avoiding the ‘fail fast’ approach and instead “double down on their initiatives if they fail the first time and focus on doing it ‘bigger and better’” for the sake of the overall public good.[footnote 142]

The failure of digital channels also comes at a financial cost, with studies showing that in 2021 1) the number of failed, scaled-back or delayed projects was very high, at 79% and 2) companies spent $5.5 million (on average) on failed projects over the course of the year.[footnote 143] [footnote 144]

A related cost that needs to be factored in with digitalisation relates to ongoing maintenance.[footnote 145] As explained by Raso, while the harms (or ‘glitches’) that arise when new technologies are introduced happen in moments, implementation is an ongoing process requiring “attention not only to how digital tools are introduced, but also to how they are maintained.”[footnote 146] These additional costs are seen in system improvements as well as system maintenance. For example, in the above-mentioned instance of Trelleborg, the Swedish Labour Market Agency spent a further 600,000 Swedish crowns (£49,128) in 2018 to improve the RPA system launched in 2017, highlighting the need to factor in ongoing maintenance, repair and improvement costs. Ongoing maintenance costs werealso reported as an important aspect of costs in the Danish context (see Box 4).[footnote 147]

Box 4 Digitalisation in Denmark

For 20 years, the Danish government has been pursuing a digital strategy involving a large proportion of corporate and regional co-operation. Denmark has digitised national services, and all layers of government now use the same digital system, which requires a great deal of coordination. Danes who are technologically disadvantaged have the option to opt out of digital service provision and instead rely on older, physical processes, such as physical mail, as an alternative to email.

Digital systems in Denmark can be accessed through citizen portals using an electronic identity (ID) to log on and apply to a range of 2,000 services. These systems are made with ease of use in mind, which is essential to transitioning more than 5 million Danes to digital services. However, user-friendliness and group representation vo still remain difficult issues. In an attempt to rectify these issues, the Danish government established digital training sessions for older people, people with a disability, those experiencing homeless and immigrants. Moreover, although offering digital services is compulsory e by law, the option to opt out without proof remains feasible.

The impacts of savings can be seen as being dependent on the scale of uptake of digital services in Denmark. For instance, a digital ‘Corona-passport’ app implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic had to consider people who did not have access to a mobile phone, people who could not receive vaccinations, and tourists. In order to assess cost savings, there needs to be sufficient uptake. This can, be seen through Denmark’s savings from digital mail: 217 million emails are sent per year, and the equivalent in regular mail would have cost an estimated £20 to £40 million.

A related cost that needs to be factored in with digitalisation relates to ongoing maintenance.

The subsequent effect of the COVID-19 pandemic led the Danish government to realise that most of their government services can be run remotely (e.g. from home) without issue. During the pandemic, digital systems took the brunt of the citizen services load, and various sectors, including hospitals, were able to function efficiently with an already established digital infrastructure. Overall, the level of disruption to government services caused by the pandemic was low.

One of Denmark’s strengths in establishing and implementing digital services is a key focus on the end user, who is often overlooked by other governments.

2.4.1 Costs associated with the failure of digital channels (continued)

Various strategies to avoid the failure of digital channels have been proposed. These include:

- shifting from crisis mode to maintenance mode, particularly in the aftermath of the initial COVID-19 outbreak, and avoiding reverting back to sub-optimal, previously established ways of working

- continuing to invest in IT staff and infrastructure

- maintaining customer relations and investing in a Chief Data Officer to oversee the digitalisation process

- resisting change for change’s sake by considering whether or not there is a need to change the mode of service provision;

- aligning digitalisation with overall strategic goals;

- ensuring continuous monitoring and evaluation to track and measure the effects of digitalisation initiatives[footnote 148]

Resisting change for change’s sake echoes concerns about avoiding technology for technology’s sake without clear strategic objectives. These and other proposed strategies to avoid the failure of digital channels can also prove costly, and therefore the cost of implementing these strategies needs to be compared with the costs of resolving digital channel failure.

It must also be kept in mind that resisting digitalisation can be just as costly as failed digital channels.[footnote 149] The notion of technical debt (or ‘tech debt’), which is the cost of additional rework caused by choosing a non-digital solution now that is easier to implement, instead of investing in digitalisation,[footnote 150] should also be kept in mind. Adequate change management – with a focus on training, support, testing, communication and building an adequate strategic framework – is proposed as the main solution to avoid failed digital channels, while taking advantage of the cost-savings solutions provided by digitalisation.[footnote 151]

Considerations for the DWP or other stakeholders in similar positions: The prevalence and likelihood of digital channel failure suggests that, while they are digitalising, organisations should include digital channel failure in their overall risk assessment and put in place mitigation plans for this possibility in their digitalisation implementation strategy. In addition to ensuring that the systems deployed are sound and robust, organisations should factor in the need to put in place monitoring, maintenance and repair processes in order to avoid the costs associated with failed digital channels. The DWP should further consider the underlying costs of delaying digitalisation and the implementation considerations raised by the notion of technical debt.

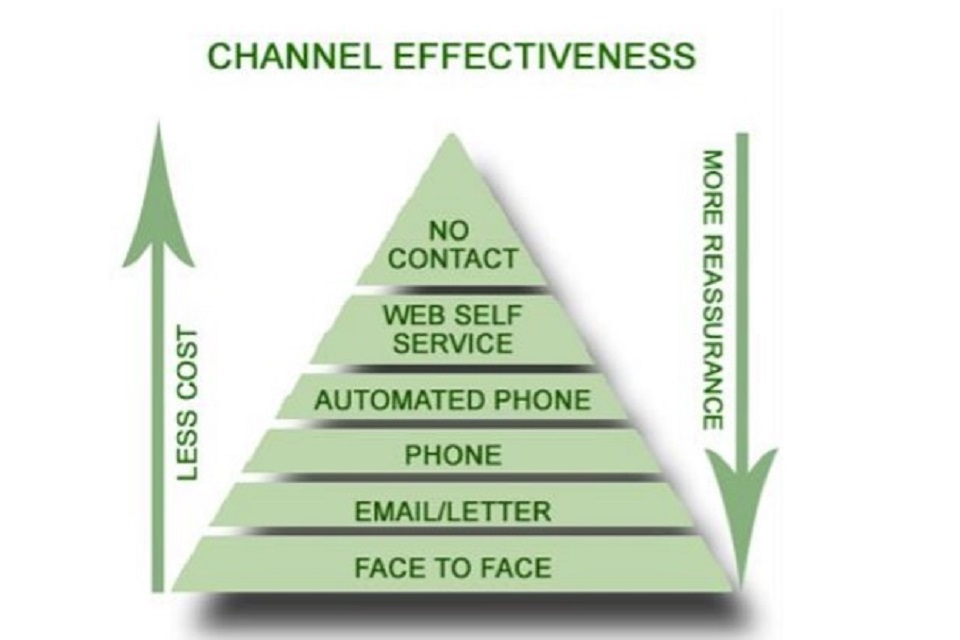

2.4.2 Digital channel mixing costs and savings