Sports Grounds Safety Authority independent review

Published 21 June 2023

Executive summary

I am pleased to have been able to conduct this review of the Sports Grounds Safety Authority (SGSA) with the assistance of Heather Batchelor of the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS).

The SGSA is a small organisation with a clear purpose and history stretching back to tragic events at Hillsborough in 1989. It has developed into a body that is seen nationally and internationally as a centre of excellence on sports ground safety, that punches well above its weight, and that is a great asset for the UK. However there is scope to strengthen aspects of the organisation and increase the SGSA’s impact within the UK and globally.

The organisation’s small size is nimble and sufficient for its current remit but it has little flexibility, giving rise to questions of its resilience in a crisis. The SGSA has an expert inspectorate, having amassed a wealth of experience, but there is a need to diversify recruitment in order to strengthen the organisation. On a corporate level, the possibility of sharing more services with other organisations should be explored further.

The funding model underpinning the organisation is inflexible and not fit for purpose, with the licence fee not reflecting the costs of regulation. With changes to the funding model, and the ability for the SGSA to charge for profit for its advice outside of the UK, the SGSA can become more self-sufficient and allow potential savings to the taxpayer. This additional income could then be used to strengthen the SGSA’s regulatory remit, allowing it to cover more football stadiums - for example expanding into women’s football and the National League. This would, however, require a commensurate increase in SGSA staffing, which should be considered when any future resourcing decisions are made.

To more effectively utilise its expertise, other large volume spectator sports could be obliged to seek safety advice from the SGSA (as many do already), without being directly regulated. There should also be consideration of whether the SGSA should play a wider role in the regulation of stewarding. On territorial scope, it would be consistent with the government’s policy on the Union for the SGSA regulatory remit to cover the whole of the UK: however there should be consultation with the devolved administrations about this.

Necessary conditions for any increase in scope are an expansion in resources - both in terms of money and staff - a properly managed programme of change, and an overhaul of the funding model to avoid increasing the burden on the taxpayer.

The SGSA Board has a clear purpose, an excellent spread of relevant skills and experience, reasonable diversity and is the right size. The term of board appointments seems short, however, and should be reviewed. The SGSA has appropriate arrangements for governance, financial management and internal control.

Many of the changes recommended require primary legislation. This has been an issue in the past because legislative time is hard to get. Should the government decide to implement recommendations from the recent Fan-led Review of football - which would require legislation - the opportunity should be taken to cover the SGSA as well.

I would like to extend my thanks to the SGSA team and all those who gave up time to be interviewed.

David Rossington, Independent Lead Reviewer.

Summary of recommendations

-

In order that the SGSA can safely remain at about its current size for its current remit, the department should provide a formal undertaking to the SGSA Chair and Chief Executive that it will work with and support the SGSA in the face of a major crisis. This could include a situation where SGSA is obliged to exercise its statutory powers in the interests of safety, but encounters resistance.

-

The SGSA should continue its efforts to diversify its workforce by exploring different models of recruitment to its inspectorate.

-

The £100 licence fee should be replaced by a flexible system of charging which reflects the full cost of regulation and enables taxpayer funding to be reduced. There should be consultation about how the costs are borne by the sector. An early opportunity should be sought to enact the new charging system. If legislation is needed, it could, for example, be linked to any legislation to enact recommendations from the recent Fan-led Review.

-

Linked to this, consideration should be given to offering the SGSA further financial freedom, for example the ability to hold reserves and carry funds from one financial year to the next.

-

The SGSA should be able to make a profit on advice commissioned from outside the United Kingdom. This would require a change to the primary legislation.

-

The possibility of the SGSA sharing HR, legal and data analysis resources with another organisation, for example DCMS, should be investigated.

-

Provided the funding model is reformed, and provided that the SGSA is allowed to increase its staff numbers, DCMS should consider expanding the SGSA’s licensing remit to cover upper league women’s football and the National League (Level 5). However this should be preceded by an assessment of the actual risks to spectator safety.

-

DCMS should consider whether the SGSA should play a wider role in the regulation of stewarding at football matches.

-

In the medium term, DCMS should consider whether other named sports should be required to seek advice from the SGSA.

-

In the longer term, there may be a case for considering an expansion of the SGSA’s remit beyond sport. This should be considered after successful expansion within football and into other sports.

-

The UK government should consider consulting with the devolved administrations and their sectors on whether the SGSA should have regulatory powers across the whole of the UK. Any increase in territorial scope would require an increase in budget and staff numbers.

-

Legislation should be amended to clarify that functions may be delegated to the executive.

-

The department, in consultation with the SGSA Chair, should review the length of appointments to the SGSA Board, and make any necessary changes through the primary legislation which would be required to implement other parts of this Review.

Purpose and role of the Sports Grounds Safety Authority

Purpose

The SGSA is the safety regulator for football grounds in England and Wales, and is the UK government’s independent advisor on sports grounds safety.

The SGSA provides independent, expert advice based on three decades of experience of ensuring that watching football in England and Wales is a safe and enjoyable experience for fans. It also uses its experience to advise and support other sports and related industries in the UK and internationally, to make sure that sports grounds are safe for everyone.

The SGSA sets safety standards through its world-leading best practice guidance, including the Guide to Safety at Sports Grounds (Green Guide), which is used to build and develop safe sports grounds around the world.

The SGSA’s expert team of inspectors provide support and advice on areas such as engineering, policing, emergency planning and facilities management. This team supports individual clubs and grounds, sports bodies, governments, architects and engineers to minimise risk and help deliver safe events for all.

Legislative bases

There are four main pieces of legislation governing the SGSA’s activities.

The Safety of Sports Grounds Act 1975

Requires any sports ground for more than 10,000 spectators to have a safety certificate to admit spectators, issued by the relevant local authority.

The Fire Safety and Safety of Places of Sport Act 1987

Extended the provisions of the Safety of Sports Grounds Act to covered stands for more than 500 spectators (so called ‘regulated stands’), in sports grounds not designated under the 1975 Act.

The Football Spectators Act 1989

Enacted after the Hillsborough disaster which led to 97 deaths and 766 injuries. The 1989 Act set up the SGSA’s predecessor, the Football Licensing Authority (FLA). The FLA issued licences to admit spectators to certain football matches in England and Wales. The matches covered are defined in the Football Spectators (Designation of Football Matches in England and Wales) Order 2000. They are matches taking place in international football stadia in Wembley and in Cardiff, and at Premier League / English Football League grounds. This is 94 grounds in all. The FLA also was made responsible for overseeing local authorities’ stadium safety certification.

The Sports Grounds Safety Authority Act 2011

Created the SGSA to take over from the FLA. In addition the 2011 Act established an advisory role for SGSA on general safety at sports grounds, including for sports other than football.

Summary of financial information

For the year ending 31 March 2022 (From SGSA’s Annual Report & Accounts 2021-22)

Total expenditure - £2,039,373

Grant in aid - £1,627,000

Revenue - £408,004

Revenue from regulatory licences (passed straight to the Treasury via the Consolidated Fund) - £9,300

Structure and size

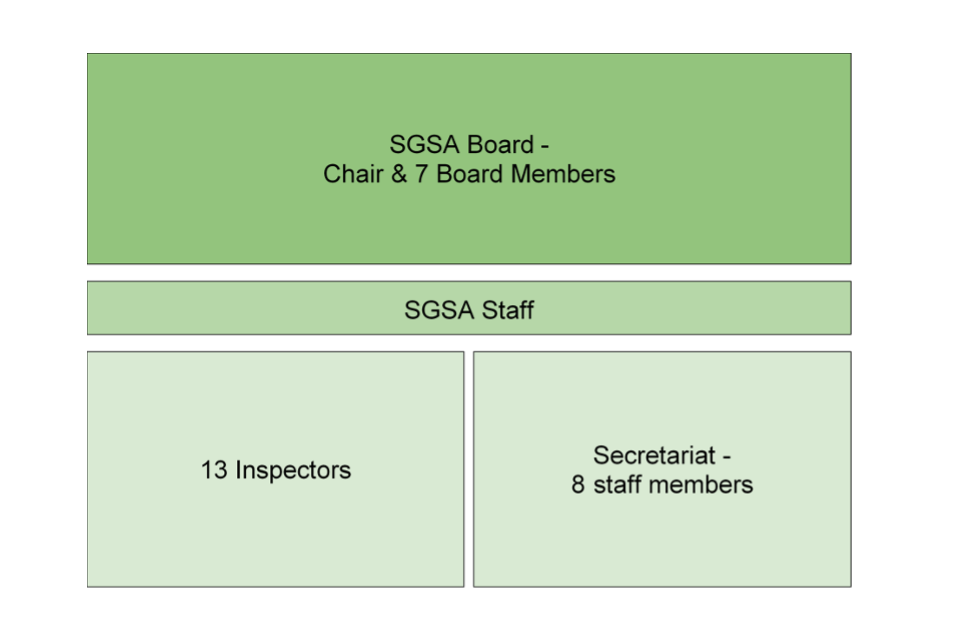

SGSA structure - Chair and 7 Board Members, SGSA staff, 13 Inspectors, Secretariat - 8 staff members

Board - Chair + 7 board members

Staff - 21 (20 FTE) as of June 2022, of which

1. Inspectors - 13 (12.2 FTE)

2. Secretariat - 8 (7.8 FTE)

Review method

Cabinet Office guidance

The Cabinet Office launched a new public bodies review programme in April 2022, which sets out how departments should assess their public bodies.

This review of the SGSA is a pilot review, undertaken prior to Cabinet Office’s official guidance being released. The review was able to benefit from the emerging thinking and draft of a Self Assessment Model (SAM) produced by the Cabinet Office. The review sought wherever possible to follow the principles of the new approach as they emerged.

In line with the draft Cabinet Office guidance, there was an independent Lead Reviewer: David Rossington, formerly DCMS Finance Director, who was assisted by Heather Batchelor and Amelia Behrens from the DCMS.

The contents of this Review report are the responsibility of the Lead Reviewer and not a statement of government policy. DCMS as the sponsoring department for the SGSA will respond formally to the recommendations set out in this report in due course.

Self Assessment Model (SAM)

The Self-Assessment Model (SAM) is an important part of the review programme for Public Bodies. The aim of the SAM is to help departments decide whether a full-scale review is needed, and if so, its scope.

The SAM consists of a set of questions for departments and Arm’s Length Bodies (ALBs) to use as a ‘health-check’ of the ALB, and to review the relationship of the ALB with the sponsoring department.

The SAM was designed to be completed by desk-based research and completed in partnership between the sponsor team within the department and the ALB.

Both the policy officials in DCMS who sponsor the SGSA, and the SGSA itself, completed a SAM, which consisted of questions split into four sections:

1. Efficacy

2. Efficiency

3. Governance

4. Accountability

A copy of the SAM is attached at Annex A.

The Terms of Reference for the Review at Annex B were based on the findings of the SAM. The Terms of Reference reflect that while the department concluded that a full-scale review of SGSA was needed, it should be of a scale commensurate with the small size and relatively small budget of this Arm’s Length Body.

Three tests

There are three tests as to whether an organisation like SGSA has a clear function as an Arm’s Length Body. These are:

1. does the body have a technical function, which needs external expertise to deliver?

2. is this a function which needs to be, and be seen to be, delivered with absolute political impartiality?

3. is this a function which needs to be delivered independently of ministers to establish facts and /or figures with integrity?

ALBs should meet at least one of these three tests, and the Review Team therefore considered how the tests applied to SGSA.

On (1), the SGSA is a regulator of football safety and auditor of local authority sports ground safety certificates, as well as a centre of expertise in the UK and internationally on sports ground safety. The Review Team considered that these were all technical functions, and that (1) therefore applied.

On (2), the exercise of regulatory and safety functions did seem to the Review Team to be matters which should be exercised with political impartiality. The Review Team therefore concluded that (2) also applies. The underlying legislation itself is a matter of policy and ultimately therefore a political matter, but policy on safety at football grounds is dealt with by the department and not by SGSA.

On (3), SGSA uses and produces data for example to guide its risk assessment of the football grounds it regulates, and of local authority sports ground safety certification. This is an increasingly important function and is delivered independently of ministers. However, SGSA is not primarily a body producing data for public consumption. The Review Team therefore considered that (3) applies in part at the moment, and may do so more in the future.

The Review Team concluded from the above that SGSA was over the threshold for clarity of function as an ALB.

The self assessment model also asked whether the ALB could deliver its function through an alternative delivery model. We considered the options, in particular merger with another body. However given the relatively low costs of the SGSA, the likely savings to the taxpayer would be small (or even nil), and a lot less than savings from reform of the funding model which we discuss below. There would also be a high risk of disruption, and potential loss of expertise at a time when anti-social behaviour in football appears to be on the increase, and there are therefore heightened risks to spectator safety. We understand that about a decade ago, a merger partner was sought but none was found. Should SGSA become a larger body in the future, the question of merger could be looked at again, but at the moment the better approach would be to look at further opportunities for sharing services with other bodies (again see below).

Evidence gathering

Written material

The following documents were used for the Review:

- annual reports

- 5 years accounts

- legislation

- Football Spectators Act 1989

- Sports Grounds Safety Authority Act 2011

- Fan-led review

- The Baroness Casey Review - An independent Review of events surrounding the UEFA Euro 2020 Final ‘Euro Sunday’ at Wembley

- SGSA Internal Audit Reports

- additional papers provided by the SGSA and the department during the Review, eg copies of SGSA’s dashboard, relevant Board papers and examples of SGSA licences.

Interviews

The Review Team interviewed a wide range of stakeholders in March and April 2022. These included SGSA and DCMS staff, the SGSA Board, football associations, clubs, and local authorities. The Review Team was very grateful for their time. A list of those interviewed is at Annex C.

In conducting these interviews, the Review Team used a common set of questions based on the Terms of Reference for the Review.

Consideration of equality and diversity issues

When conducting this review and developing our recommendations, regard was given to the equality impact of the recommendations. We consider that none of the recommendations made in this report will have a negative equality impact on the staff of the SGSA or the customers who benefit from the public services that the SGSA delivers. Indeed we would expect that if recommendations 2 and 7 are enacted, there would be a positive equality impact on the staff of the SGSA and the customers who benefit from the public services that the SGSA delivers, through increasing the diversity of the workforce and extending the scope to the women’s game as well as the men’s.

Nature of regulatory system for football safety

The Review Team noted the relatively complex nature of the regulatory system for the 94 top football clubs and national football stadia in England and Wales. It is a dual system, in that local authorities issue safety certificates annually for the sports grounds, while the SGSA issues separate annual licenses for the admission of spectators, and advises and audits the local authorities. The system lies apart from the main vehicle for regulation of safety, the Health and Safety Executive (HSE).

This system has developed as a result of what has happened regarding safety in football grounds over the last 50 years. There was a disaster at the Rangers football ground at Ibrox Park in 1971 (in which 66 people were killed and more than 200 people were injured), and local authority licensing was introduced in 1975. However following the tragedy at Hillsborough in 1989, a second leg of regulation was introduced in England and Wales through the creation of the Football Licensing Authority, the forerunner of the Sports Grounds Safety Authority. Since this dual system has been introduced, there have not been further catastrophes, although there is no room for complacency. As set out in the Casey Review, the events at Wembley at the UEFA final in the summer of 2021 were a near miss.

This regulatory system may not be exactly the one which would be set up if starting from a completely clean slate. It reflects an organic and pragmatic approach. However no one the Review Team interviewed called for a complete overhaul of the system, and there was no evidence either from the interviews of confusion or duplication of function between the SGSA, local authorities or the HSE. Indeed the current system appears to bring together the benefit of knowledge of the locality from local authorities, and central expertise and guidance from the SGSA.

Size of the Sports Grounds Safety Authority

Current size

From the SGSA’s Annual Report and Accounts 2021-22:

The average number of full-time equivalent persons employed during the year was:

| 2021-22 | 2020-21 | 2019-20 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Directly employed | 18.2 | 16.6 | 16.9 |

| Seconded | 1.6 | 2.8 | 2.6 |

Considerations

Size

We asked interviewees whether they considered the SGSA to be of the right size to fulfil its current remit. Its remit in the regulatory area is fixed - to regulate football grounds in the top tiers of football in England and Wales, and in the advisory area is more flexible - to use its knowledge and experience to advise and support other sports across the whole of the UK and indeed around the world.

A few recurring themes emerged from the responses to this question.

Stakeholders reported that they had good communication with relevant SGSA officials, and that the quality of these relationships and level of service is high. We encountered no complaints about the service received from the SGSA, and heard much praise for the work that they do and their relationships with stakeholders. However, the view that the SGSA appears stretched in achieving its current output was a message that cropped up multiple times in conversation with participants.

The number of inspectors appears to be sufficient for the current number of clubs requiring licences, but leaves limited capacity for any additional work. In order to provide advice, it is sometimes necessary to move inspectors off of core regulatory work. The flexible approach that the organisation adopts in prioritising and balancing which work it undertakes is fundamental in keeping the organisation functional.

There is possibly potential to strengthen the back office function, an area that we explore further in the section on in-house expertise vs buying in services.

One issue with the current model is that it lacks much resilience. For example, it would be difficult for the SGSA to respond effectively to a major crisis (such as a serious issue with safety at a big football club where it had to take regulatory action over an extended period of time involving many people in SGSA) while continuing business as usual. Furthermore, with the small number of highly performing and specialist staff, there is a very real risk that, for example, a key staff member or two leaving the organisation would tip the balance and significantly impact the SGSA’s ability to perform its role.

A further issue could arise in relation to SGSA’s regulatory approach. When a safety issue arises at a ground subject to SGSA licensing, the SGSA seeks to use education and persuasion, working with the relevant local authority, to bring the ground back into compliance. Using its statutory powers to amend its own licences and/or to direct local authorities is very much seen as a last resort. Indeed we were not made aware of any recent incidences of this happening, even after the near miss at Wembley in July 2021 - when thousands of ticketless supporters sought to force their way into Wembley Stadium and created significant levels of disorder in and around the ground. We understand that the department would be ready to back the SGSA should it have good reason to use its statutory powers. However a body of 20 staff and with total expenditure of just over £2m might be overstretched if it had to engage in a sustained regulatory dispute with a major football club.

Staff development

The inspectorate at the SGSA largely consists of people who have had careers elsewhere and are joining towards the end of their professional lives. This is due to a variety of factors, including the fact that public sector salaries are typically lower than the equivalent in the private sector, which is a barrier to recruitment.

The current recruitment model has the benefit of giving the organisation lots of relevant experience and well informed judgement, but leads to questions about succession planning and the diversity of the inspectorate.

The SGSA is aware of these issues and are exploring other models, for example by employing interns, and hiring people at the start of their career and training them up while accepting that they will move on after a few years. These efforts must continue as the age profile of the inspectorate, combined with the small size of the organisation, is a vulnerability.

Conclusions

The SGSA manages its current responsibilities well with the resources that it has, despite a broadening remit and the challenges that have arisen in recent years, such as Covid-19. For its current remit and provided it is accepted that its regulatory approach will continue to be based on education and persuasion, its size appears to be about right.

Numerous factors mean that the SGSA inspectorate has a disproportionately older workforce. This has many positives, but also the potential to have a negative impact on succession planning and diversity.

Recommendations

1. In order that the SGSA can safely remain at about its current size for its current remit, the department should provide a formal undertaking to the SGSA Chair and Chief Executive that it will work with and support the SGSA in the face of a major crisis. This could include a situation where SGSA is obliged to exercise its statutory powers in the interests of safety, but encounters resistance.

2. The SGSA should continue its efforts to diversify its workforce by exploring different models of recruitment to its inspectorate.

Funding model

Current funding

The SGSA receives funding in 2 ways: via Grant in Aid and through self-generated income.** In addition,** the SGSA charges for the issue of licenses to admit spectators to watch designated football matches. In the year ended 31 March 2021, 92 licenses were issued to grounds for a fee of £100 each. In accordance with the SGSA’s Financial Memorandum, these fees are paid into the Consolidated Fund via DCMS and are therefore not recognised as income in the SGSA’s Accounts.

From SGSA’s Annual Report & Accounts 2020-21:

| Income from government | 2021-22 (£) |

|---|---|

| Grant-in-aid | 1,627,000 |

| Other Income | |

| Sale of publications | 65,889 |

| Income from contracts with customers - UK* | 186,230 |

| Income from contracts with customers - overseas* | 30,100 |

| Other income | 125,785 |

| Total (excluding GiA) | 408,004 |

*The SGSA has contracts with ECB, Sport NI, FA Wales, Scotland, FIFA.

Considerations

Licence fee

The current licence fee of £100 has remained unchanged since the Football Licensing Authority started to issue licences some 30 years ago. This figure does not reflect the cost of issuing the licences which the SGSA estimated in 2019 was around £2,000 on average (although this did not reflect the full costs of regulation).

This means that the taxpayer, through the grant in aid, is bearing the great majority of the costs of regulation. However keeping sports grounds safe for spectators could be seen as a necessary cost of business for the regulated football clubs, some of which (but not all) are multi million pound businesses. Following this line of argument would suggest that those regulated, i.e. the 92 clubs and two national stadia, should bear the full costs of the regulation undertaken by the SGSA in relation to them. Such an approach would bring the SGSA much more in line with other sectors where those regulated bear the costs.

All those interviewed whether in the department, the SGSA, or the football industry, recognised that the £100 cost of the licence fee does not reflect the costs of regulation in any way. There was also general (but not universal) support for an increase in the fee.

We understand that this is by no means a new issue and has been considered both by the department and the SGSA in the past. The Review Team considered in the first instance the principles of any change here, and then how it might be effected.

In terms of principles:

-

Any change should be to a more flexible system of fee setting. Simply replacing the £100 figure with another one which in turn might have to be amended after a few years would not meet this requirement. A better approach (which we understand is similar to that used at the energy regulator Ofgem) might be to permit SGSA to make a charge before the costs had been incurred, which could then be adjusted up or down in the following financial year based on the actual costs of regulation.

-

There should be consultation with those regulated on how to divide up the costs of regulation. This could for example be a flat rate, or vary by division, stadium attendance or broadcast revenue. We understand that the actual regulatory costs incurred by the SGSA are likely to be much higher for new entrants to the top two leagues of English and Welsh football. Clubs which are already in these divisions will already have had time to adjust to the SGSA’s safety requirements. However new entrants may also be likely to have less financial resources than clubs more established in the top two leagues. Any new system of fee setting will have to take account of these different factors.

-

The SGSA should be fully transparent with those it regulates about the calculation of the costs of its fees.

-

The SGSA should retain the increased fees rather than them being paid into the Consolidated Fund. In turn there should be an adjustment downwards to SGSA’s grant in aid to reflect the increased fees. This could achieve a substantial saving in the taxpayer funded costs of the SGSA.

-

Since the SGSA will be more dependent on fees, and less on grant in aid funding, there will need to be an increase in its financial freedoms. In particular, there should be consideration as to whether it should be able to hold reserves, and carry some funds across from one financial year to the next. This in turn will require additional financial management by the SGSA, and any extra management costs of this should be included within the calculation of the fee.

-

In terms of how these changes might be effected, the Review Team understands that legislation is not needed to change the £100 figure (although could well be for wider changes). Should primary legislation be needed, we recognise that t is never easy to secure time for this in a crowded legislative timetable. However, there may be an opportunity if the government decides that primary legislation is needed to implement recommendations from the Fan-led Review of Football Governance. Should that be the case, the scope of the legislation should include changes to the system for levying the SGSA licence fee.

Auditing local authority sports grounds safety certification

As with the licence fee, an argument could be made that the SGSA should charge local authorities for the work it does to audit their sports ground safety certification. However the point was made in a number of interviews that some local authorities were finding it increasingly difficult, because of their overall financial position, to engage as they previously had done in sports ground safety. We were concerned that there would be a risk that any fee for the SGSA auditing would result in a budget reduction within the local authority for other sports ground safety work. In addition there may be a less strong case for one part of the public sector (the SGSA) to charge another part of the public sector (a local authority) for work to ensure the public good that football clubs are safe for their spectators.

Grant in aid

We understand that the baseline used as the starting position for the SGSA’s grant in aid in spending reviews is some £600,000. This is far lower than the actual grant in aid of £1.627m in the 2021-22 financial year.

This is an inconvenience which means that adjustments have to be made by the department, sometimes year by year, in order to fund the SGSA. It also reduces financial certainty for the SGSA, and the ability to plan, and discipline of planning, against forward budgets.

We also understand that following the recent spending review, DCMS now has some ability to adjust the baselines of ALBs where these are out of line. There should be consideration of whether to do so in this case. Should there be changes to the system for licence fees as set out above, an upward adjustment of the baseline in the short term could be followed by some downward adjustment in due course, when the new system for fees has been introduced.

Charging for advice

At the moment, the SGSA is able to (and does) charge for advice, but at cost only. It is not able to make a profit or surplus in this area of its activity. Review participants expressed a range of views on this topic.

The SGSA produces a practical guide on sports ground safety known as the Green Guide. This was universally very highly regarded among the stakeholders we interviewed, both in England and Wales, the rest of the UK and beyond. It is clear that the advice that the SGSA is able to provide is extremely valuable, and several interviewees regarded it as a world leader in its field. It was also suggested that the Green Guide and the high reputation of the SGSA internationally was very useful for promoting business in relation to stadium safety for British companies working around the world.

Some could see benefits in moving the organisation to a commercial model, and for it to be able to charge commercial rates for advice including profit, perhaps by setting up a commercial arm. However it is noteworthy that, although the SGSA charges cost for its advisory work, when working abroad, their rate combined with the cost of travel etc. to foreign countries, combines to create a rate that may already be comparable to a commercial rate.

Others said that charging too high a rate would mean fewer organisations would seek advice – particularly those facing financial pressures – and that this could have a detrimental effect on safety standards. Some saw advice on sports ground safety as a public good which should not be charged for at commercial rates. It was also suggested that charging too low a rate for advice could undercut the development of a private sector market in sports ground safety advice.

Many recognised the potential conflict of interest of a regulator charging commercial rates for advice within its jurisdiction. They pointed to a danger of the perception, and potential reality, that the regulatory work would be undertaken in a way to maximise profits from advice, and not solely to maximise the safety of the public.

Conclusions

There are several ways that the government could assist in making the SGSA’s finances more productive and sustainable. If these issues are resolved effectively, the SGSA could become less reliant on taxpayer funding and more self-sufficient, and able to fund additional work to ensure safety at football stadiums.

Licence fee

The Review Team concluded that the £100 licence fee is the fundamental part of the funding model that requires rethinking. It should be replaced by a charge reflecting the full cost of regulation. As with Ofgem, an estimate of the cost could be charged at the beginning of the financial year, and an adjustment then made to the cost the next year depending on the actual costs incurred. There would need to be consideration of – and consultation about – how to spread the costs over the industry regulated.

Auditing local authority sports ground safety certification

We saw little merit at this point of the SGSA charging for this.

Grant in aid

In the short term DCMS, consulting Treasury as necessary, should consider adjusting the baseline for the SGSA so that it reflects the actual levels of grant in aid. If the licence fee were increased to cover the costs of regulation, the grant in aid could in due course be reduced. However if primary legislation were required, this would all take some time. In addition, if the SGSA were more financially dependent on fee income, consideration should be given to allowing it to hold some reserves, and carry over some spending from one financial year to the next.

Charging for advice

The Review Team concluded that there was a real problem with potential and indeed actual conflict of interest should the SGSA as a regulator charge commercial rates for its advice. We doubted if this could be overcome by setting up a commercial arm to the SGSA. Given the very small size of the organisation, staff would very likely have to work across both the commercial and regulatory sides. A way forward might be to permit commercial rates for work outside the organisation’s regulatory jurisdiction in England and Wales, or possibly only outside the UK. The profits from international work could in turn enable the organisation to increase its capacity while not reducing its work on regulation.

Recommendations

3. The £100 licence fee should be replaced by a flexible system of charging which reflects the full cost of regulation and enables taxpayer funding to be reduced. There should be consultation about how the costs are borne by the sector. An early opportunity should be sought to enact the new charging system. If legislation is needed, it could for example be linked to any legislation to enact recommendations from the recent Fan-led Review.

4. Linked to this, consideration should be given to offering the SGSA further financial freedoms for example the ability to hold reserves and carry funds from one financial year to the next.

5. The SGSA should be able to make a profit on advice commissioned from outside the United Kingdom. This would require a change to the primary legislation.

In-house expertise vs buying in services

Current position

The SGSA currently has an in house safety inspectorate (13 staff), an in house finance director, policy lead and IT lead, and in house general administration services. It buys in HR, legal and data analysis functions on an ad hoc basis. The majority of its staff are home based, and there is a touch down space in a government building in Canary Wharf, meaning that SGSA already has shared building and estate services.

Considerations

As with many small organisations, there is continual consideration of what should be in house and what should be bought in. While in house expertise may be more convenient and indeed have a better understanding of the particular issues of the organisation, it can also be more expensive and add significantly to overhead costs. The paragraphs below address three service areas but there may be others (eg communications) to consider.

HR

Not having in-house HR expertise poses risks, for example if any significant HR issues arise. Lesser development of HR policies could leave the organisation vulnerable if any of its practices are challenged. This is the one area where, based on the SGSA’s own calculations, an in house resource might offer greater value for money.

Legal

A lack of in-house legal expertise may leave the organisation particularly vulnerable if it ever faced a legal challenge. It may also make it more difficult for the SGSA to take a proactive approach to regulation where its preference for education and persuasion is not proving sufficiently effective. SGSA is fortunate to have a Board member whose expertise is in regulatory law, but seeking legal advice from a Board member (as opposed to assurance) runs the risk of a conflict between executive and Board roles. However the SGSA’s calculations suggest that an in house lawyer would be more expensive than the current arrangements for buying in advice when needed.

Data

Several interviewees suggested that the SGSA would benefit from an in-house data analyst. For example, the SGSA uses risk analysis to decide where to focus its greatest regulatory efforts, and improved data analysis could therefore improve its understanding of risks. Having in house data expertise may help SGSA as it becomes a more data driven organisation.

Conclusions

There is some support for increasing in-house capabilities, particularly for legal, data analysis and HR. However this would in most cases be more expensive than buying in when required, so would push up the cost base of a small organisation and be difficult to afford within current budgets.

Sharing of services might provide some of the advantages of having in-house expertise, while reducing the costs. Options around sharing of services with others should be explored by the department and the SGSA. For example, with DCMS’s agreement, it might be possible for the SGSA to buy the time of a government Legal Service lawyer based in DCMS for a couple of days a week, and to do the same with a DCMS data analyst. Equally it might be possible to share legal services with another public body and indeed SGSA is already looking at this. Sharing services might give the SGSA access to expertise without unduly adding to its cost base.

Recommendation

6. The possibility of the SGSA sharing HR, legal and data analysis resources with another organisation, for example DCMS, should be investigated.

The remit of the SGSA

Current scope

The SGSA’s current regulatory role is to:

- issue licenses to the 92 Premier League and English Football League (EFL) grounds, along with Wembley and the Principality Stadium to allow them to permit spectators to watch matches; and

- oversee local authorities in their duties to sports grounds safety and safety certification

The SGSA also provide safety advice and support to other sports both in the UK and internationally, supporting in areas including:

- strategic advice, including diagnosing physical infrastructure and safety management risks to existing, new and refurbished stadiums

- proactive action planning to enable sports bodies/grounds to develop and enhance spectator safety

- educating to plan and prepare for challenging scenarios through the provision of training and scenario planning programmes

The SGSA’s direct regulatory remit does not currently include the women’s professional game in football, grounds that host men’s football matches below the Premier League and EFL level, or other sports. However although the SGSA does not issue licences itself for grounds for these other sports, it does assess local authority safety certification which covers a wider range of sports grounds. In addition SGSA provides advice under contract to cricket.

SGSA does not cover non sporting events held at sports grounds, nor events attracting large numbers of spectators more generally (eg music festivals), although it issued a guide on Event Safety Management in 2021.

Finally the SGSA’s remit is confined to English and some Welsh clubs. It does not extend to Scotland or Northern Ireland. This is considered further below.

Considerations

There was general support for an extension of the SGSA’s remit from those interviewed. The Review Team took this as a vote of confidence in the SGSA’s professionalism and expertise.

In considering scope extension, the Review Team bore three areas in mind:

-

the SGSA exists to safeguard the public at sporting events where there are many spectators. When a member of the public attends a sporting event, they should be able to expect a suitable level of safety protection, regardless of the sport.

-

the nature of the regulatory protection needed is a function of the risk. The current direct coverage of 92 clubs and two national stadia reflects that it is predominantly at upper league men’s football matches where serious safety issues have arisen in the past.

-

an expansion in the SGSA’s remit would require an expansion in the resources - both money and staff - available to it. An expansion in remit without an expansion in resources, and without a properly managed programme of change, would compromise the quality of the SGSA’s services and its reputation.

The SGSA currently has 13 inspectors for 94 clubs and stadia: if this were to go up to say 175 clubs, the number of inspectors would need to nearly double, with appropriate time allowed for recruitment and training. Indeed if these new clubs required more work than the existing ones (quite likely as they would be newcomers to SGSA licensing) an even greater increase in resources could be needed. There would also have to be a commensurate increase in the SGSA’s back office and secretariat. Overall, this might mean an increase in the size of SGSA to around 35 to 40 staff, which would be a major change for the organisation.

These changes could be funded by making the amendments to the funding model set out in this report. However, under the current funding arrangements, the DCMS and the Treasury would have to agree to increase grant in aid.

Moreover, should the organisation become significantly larger, the processes suitable for a small organisation of 20 staff would have to change, and become more formal in some instances.

Football

Many interviewees expressed the view that the SGSA’s scope should be increased to include women’s football (2 leagues including 12 clubs with grounds not shared with men’s first teams). This was both for reasons of parity with the men’s game, plus the sport is growing in popularity and crowd size, so may encounter many of the same issues as men’s football. As in many cases upper league women’s football makes use of the same stadia as are already directly regulated by the SGSA, so an expansion to upper league women’s football might be relatively straightforward.

It was also commonly expressed that the SGSA should broaden its remit within football to cover lower leagues, in particular the National League (Level 5 of the football pyramid: 24 clubs) and possibly also the National Leagues North and South (Level 6: 44 clubs). A few reasons for this emerged, including that:

- it is not the success of a football club that determines the likelihood of safety issues within the stadium

- regulating clubs in the lower leagues would remove the step change in safety considerations that occurs as clubs enter leagues regulated by the SGSA

To include women’s football and lower leagues of men’s football would draw directly from the SGSA’s specific expertise. There are important questions to consider even within this expansion of the SGSA’s responsibilities, including:

- where to draw the line in terms of which clubs to include

- how to make the cost of compliance for small clubs affordable and the process not excessively onerous

The Review Team considered that before any expansion of remit takes place either to women’s football or to lower football leagues, there should be an assessment of the risks to spectator safety at these events. The SGSA has developed a risk assessment for the grounds it already directly regulates, and could perhaps adapt this, and apply it to a selection of the grounds/clubs it might take on. This would give some evidence, not currently available as far as the Review Team is aware, against which the department could take an informed decision as to whether the current local authority sports ground certification, audited by the SGSA, gives sufficient protection for women’s football and lower leagues, or whether an extension in the SGSA’s direct remit is needed.

| Men’s football | Women’s football |

|---|---|

| Covered by SGSA remit | Not covered by SGSA remit |

| Premier League (20 Teams) | Women’s Super League (12 Teams, 4 with grounds not shared with men’s first teams) |

| Championship (24 Teams) | Women’s Championship (12 Teams, 8 with grounds not shared with men’s first teams) |

| League One (24 Teams) | |

| League Two (24 Teams) | |

| Not covered by SGSA remit | |

| National League (24 Teams (fully professional)) | |

| National League North and National League South (22 Teams in each (mix of fully and semi-professional)) |

The international stadia at Wembley and in Cardiff (the Principality Stadium) are also under SGSA licensing.

Other sports

Beyond football and into other sports, interviewees’ opinions became more divided. Sports frequently mentioned included rugby, cricket, horse racing, tennis and Formula 1, owing to the large crowd sizes and some similarities in the types of safety issues that are faced at some of these sporting events.

Many people thought there should be an extension as public safety of crowds matters for all spectator sports. However there was a recognition that football, and in particular higher football league clubs, present the greatest risk because of the history of behavioural issues which are less prevalent (but not non existent) for other sports. Extending to other sports would mean an increase in inspections, so any extension would need to include an adequate means of covering costs and recruitment and training of new staff.

Though the SGSA has expertise that would no doubt transfer readily across to sports that face similar safety issues to football, questions about ‘where to draw the line’ began to emerge in our interviews with more frequency in relation to other sports.

Events

These questions about drawing the line continued into discussions with interviewees about the SGSA’s involvement in the safety of events beyond sports, such as music events and festivals.

Many agreed that if an event was held in a stadium then this could conceivably be covered quite neatly within the SGSA’s remit: beyond this, views varied a lot. While the SGSA has produced written guidance about the safety management of events, moving into these areas would mean the stakeholders are different from those in the sporting world. There would also be a danger of SGSA spreading itself too thinly.

Other issues

Increase in disorder

Numerous interviewees noted that they have observed an increase in anti-social behaviour at football matches. This was highlighted at the UEFA Euro 2020 Final in Wembley Stadium in July 2021.

Various reasons for this were put forward. These included boisterous spectator behaviour at the reopening of football stadia after a period of closure due to COVID-19, increased drug taking at football matches, changing societal attitudes and poorer stewarding.

Stewarding

Several interviewees mentioned problems with stewarding. It was suggested there are not enough trained and experienced stewards, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic, and that the sector should be more regulated.

In addition, there was widespread recognition of the pressure local authorities are currently under, leading to high turnover of safety staff. The SGSA is widely seen as performing an even more important role in these circumstances as the source of expert advice on sports ground safety. Indeed some interviewees suggested that it should take on a greater role in the regulation of stewarding.

Conclusions

The SGSA is uniquely-placed to advise on extremely important issues of spectator safety across all sports. This should be utilised where practicable. In practice, some other sports already take advice from the SGSA, for which they pay at cost. A possible way forward, which would build on the organisation’s experience while taking account of the different risk profiles, would be to require other sports to seek SGSA guidance, without bringing in the full panoply of controls for higher league football.

An expansion of the SGSA’s remit would represent a significant step-change. Any expansion in the SGSA’s remit should be preceded by an assessment of the risks to spectator safety. Any expansion must also be accompanied by a commensurate increase in the size and funding available to the SGSA.

Our understanding is that to expand the SGSA’s remit would require primary legislation. If so, the legislative change should be introduced at the same time as legislative change on charging. The new legislation should be framed in such a way that it is possible in the future to vary the SGSA’s remit should circumstances change, without recourse to primary legislation (eg by means of a statutory instrument).

Recommendations

Football

7. Provided the funding model is reformed, and provided that the SGSA is allowed to increase its staff numbers, DCMS should consider expanding the SGSA’s licensing remit to cover upper league women’s football and the National League (Level 5). However this should be preceded by an assessment of the actual risks to spectator safety.

8. DCMS should consider whether the SGSA should play a wider role in the regulation of stewarding at football matches.

Other sports

9. In the medium term, DCMS should consider whether other named sports should be required to seek advice from the SGSA.

Events

10. In the longer term, there may be a case for considering an expansion of the SGSA’s remit beyond sport. This should be considered after successful expansion within football and into other sports.

The territorial scope of the SGSA

Current position

The SGSA currently regulates England and Wales. The Sports Grounds Safety Authority Act 2011 extends to England and Wales only.

If advice is requested from a person or body outside of England and Wales and the Secretary of State consents, the SGSA can provide advice to:

- a government of a territory outside the United Kingdom

- an international organisation, or

- a body or person not covered by the above whose functions, activities or responsibilities relate in whole or part to the safety of sports grounds outside England and Wales

Considerations

Some of those interviewed said they could not see why there were different regulatory regimes in different parts of the UK, with the SGSA having no formal remit in Scotland or Northern Ireland. However the organisation does provide paid advice to both administrations on sports ground safety.

From the interviews, there was evidence that the SGSA is highly respected in Scotland, and is seen as a reliable and pragmatic source of advice. The guidance the SGSA provides to Scottish colleagues is highly valued and there is currently a contract in place for the SGSA to provide advice to the Scottish Government. There are similar arrangements in Northern Ireland.

Conclusions

It would be consistent with the government’s policy on the Union for there to be similar provisions for the safety of football spectators across the whole of the United Kingdom. However the Review Team understands that this is a devolved matter, so would have to be discussed and agreed with the devolved administrations, and followed by legislation amending the 2011 Act. Any increase in the SGSA’s territorial remit would need to be reflected in the number of SGSA staff and its resourcing.

Recommendation

11. The UK government should consider consulting with the devolved administrations and their sectors on whether the SGSA should have regulatory powers across the whole of the UK. Any increase in territorial scope would require an increase in budget and staff numbers.

Purpose and compliance of the SGSA board

Current board membership

The SGSA Board consists of the Chair and seven Members appointed by the Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport in accordance with the requirements of the Sports Grounds Safety Authority Act 2011. A full list of the current members is at Annex D. During the course of the Review, we were able to meet with Board members individually, as well as hold discussions with the Board as a whole.

Considerations

Purpose

Those interviewed with knowledge of the SGSA’s board universally expressed that they felt that its purpose was clear and well understood. The body has such a specific and tangible remit that the board’s role in upholding it left little room for confusion.

Skills and experience

The SGSA Board has an outstanding mix of relevant skills and experience, covering sports architecture, diversity in sport, local authority management, fire and safety, regulatory law, the sports industry, statistics and data analysis and policing.

Although there is no qualified accountant on the Board, the SGSA has an experienced and qualified Finance Director, and its Audit and Risk Committee is active and supported by a programme of internal audits.

Diversity

The Board has 62.5% female membership and 37.5% male membership. It also has 12.5% minority ethnic background membership.

Size

With 8 members, the Board is of a manageable size. It is large compared to the size of the SGSA executive staff team (21 people). However, reducing the size of the Board would reduce the very strong set of skills and experience that the Board brings.

There is always a danger that with a well qualified Board, and one that is large relative to the organisation, the Board may be tempted into undertaking tasks best suited to the executive and this is exacerbated by the fact that the SGSA Act 2011 does not expressly give the SGSA a general power to delegate its functions. We noted for example that Board members have a role in examining individual licences for clubs before they are approved, in addition to assuring themselves that the system for licence approval is sound, which would be a more usual focus of a non-executive Board. While this did not seem a significant issue, in order to ensure that the Board can operate as a non-executive rather than an executive body, we recommend that the legislation is changed to give the Board powers of delegation.

Conclusions

The Review Team concluded that the Board was compliant with the requirements for the type of ALB.

It would be beneficial to the SGSA for the Board to be able to more formally delegate its functions to its executive should it decide that it is beneficial to do so.

One issue raised was the term of appointments. We noted that the Sports Grounds Safety Authority Act 2011 states that “A person is not to be appointed as a member of the Authority for more than 3 years at a time.” There was comment from some interviewees that the three year length of appointment for Board members was too short, particularly given the length of time needed to make public sector Board recruitments. Across DCMS boards, term appointments generally vary in length from 3 to 5 years, with 4 or 5 years being more usual. Since the term of appointment is stated in the 2011 Act, it appears that primary legislation would be required to change it.

A further issue raised was that sometimes many board appointments come to an end at a similar time, meaning a potential sudden outflow of expertise. This is often an issue with ALB Boards, and a flexible approach by the department (eg short term extensions of some terms) can help to alleviate it.

Finally we understand that the remuneration of Board members (£265 per day) has not been reviewed for some time. This might be usefully looked at again as part of the follow up to this Review.

Recommendations

12. Legislation should be amended to clarify that functions may be delegated to the executive.

13. The department, in consultation with the SGSA Chair, should review the length of appointments to the SGSA Board and make any necessary changes through the primary legislation which would be required to implement other parts of this Review.

Governance, financial management and internal control

Current position (March 2022)

The Review Team noted that the Board has a corporate responsibility for:

- ensuring that the SGSA complies with any statutory and administrative requirements for the use of public funds and does not exceed its statutory powers or delegated authority

- ensuring that high standards of propriety and corporate governance are observed at all times

- establishing the overall direction of the SGSA within the policy and resources framework agreed with the Secretary of State; and

- overseeing the delivery of planned results through the monitoring of performance against objectives

The Board exercises this responsibility through receiving key reports from management including the management accounts and updates from the Audit and Risk Committee on risk, IT security and the Annual Report and Accounts.

The SGSA has an active Audit and Risk Committee, which is the only sub committee of the Board. Given the size of the organisation there are not separate Nominations and Remuneration Committees.

The Audit and Risk Committee meet 3 times a year and currently has the following members, all of whom are Members of the SGSA’s Board:

- Janet Johnson (Chair)

- Rimla Akhtar

- Susan Johnson

- David Mackinnon

The Committee reports on its work to the full Board.

In 2020-21 the Audit and Risk Committee considered a range of issues including the SGSA risk register, anti-fraud policies, health and safety and the reviews provided by the internal auditors, as well as regular financial management issues and the Annual Report and Accounts. The Committee provides the Board with reports on governance, internal control and risk management issues.

Considerations

The Review Team looked at the SGSA’s accounts for the last five years. There were no adverse observations from the external auditor, who is the Comptroller and Auditor General, nor any other issues which caused the Review Team concern from the points of view of financial management and internal control.

There is an agreed plan of internal audit work, undertaken by the Government Internal Audit Agency. While the internal audit reports for the last five years make some recommendations for improvement in certain areas, they are not out of line with what might be expected for an organisation of the SGSA’s size.

We noted that the SGSA has recently developed a method of risk profiling the clubs it licences, and the local authorities it audits. The summary results of this are presented regularly to the Board. This is an important means of targeting SGSA resources on priority areas, and is a good example of utilising data in an effective way.

Conclusions

The SGSA’s arrangements for governance, risk management, financial management and internal control seem satisfactory for a body of its size.

Recommendations

We had no recommendations in this area.

Annex A – Self Assessment Model

Note that this is an early version of the Cabinet Office’s SAM, and has since changed.

Annex B – Sports Grounds Safety Authority Review: Terms of Reference

The SGSA Review is a pilot of the Cabinet Office’s new Arms Length Bodies review Programme, testing some of the products, guidance and processes of the new programme.

The Lead Reviewer and Review Team will refer back to the ToR throughout the review process.

Key Principles

The new programme of reviews has been designed to meet the following principles:

- useful to both sponsor department and ALB

- informed by relevant expertise

- proportionate

- rigorous and open

- realistic

Why this review is needed

The SGSA was established (originally as the Football Licensing Authority) in 1989.

The SGSA performs an important function, aiming to ensure that all spectators, regardless of age, gender, ethnic origin, disability, or the team that they support are able to attend sports grounds in safety, comfort and security. It is imperative that the SGSA are able to effectively meet these aims.

Themes and quadrants the review will seek to explore

Completion of the Self Assessment Model by both the SGSA and the Sponsor Team has established that the following quadrants should be explored in more detail:

Efficacy: Form

We will explore the requirement for ALBs to be the correct and appropriate delivery model, including examining alternative delivery models.

- what is the optimum size of the organisation to ensure its effectiveness and sustainability?

- what is the appropriate funding model for SGSA?

- should SGSA be granted financial freedoms in line with other ALBs that rely on commercial income or would this create risks that SGSA could not manage?

- what is the right balance between in-house expertise and buying-in/sharing of services - e.g. legal, research and data analysis?

- is SGSA maximising the potential of digital/technology to fulfil its functions?

Efficacy: Outcomes for citizens

We will explore the requirements for ALBs to ensure that it has the correct systems and knowledge in place to deliver effective outcomes for all citizens.

- should the scope be extended beyond current remit?

- should the territorial scope be extended beyond England (and Welsh grounds hosting English Football league matches) - either on a regulatory or voluntary basis?

Governance: Purpose, leadership & effectiveness

We will explore the requirements that:

- whe ALB board have a clearly articulated purpose and the correct balance of skills and experience appropriate to fulfilling its responsibilities; and

- the membership of the board must be balanced, diverse and manageable in size and compliant with the requirements for the type of ALB

Governance: Effective financial and risk management and internal control

We will explore the requirements that:

- the ALB must have effective arrangements in place for governance, risk management and internal control; and

- the ALB board must take the appropriate steps to ensure that effective systems of financial and risk management are in place to ensure that it meets all of its obligations as set out in Managing Public Money

Who will be conducting the review

David Rossington - Lead Reviewer

Heather Batchelor - DCMS ALB Review Lead

Supported by:

Sponsor Team

Francesca Broadbent - DCMS Head of Elite and Professional Sport, Sponsor Team.

Charlotte Kenealy - Senior Policy Advisor, Elite and Professional Sports, Sponsor Team.

ALB Senior Leadership

Martyn Henderson - Chief Executive, Sports Grounds Safety Authority.

Derek Wilson - Chair, Sports Grounds Safety Authority.

Roles

DCMS ALB Review Team to:

- provide general secretariat

- seek advice from DCMS subject experts

- seek SCS and ministerial clearances where necessary

- support the handling of the review within the department, ensuring that the Principal Accounting Officer, ministers and the ALB are engaging, as needed, with the review at the required stages

- ensure appropriate engagement between the Lead Reviewer and ALB, key stakeholders, and other key officials in their and other departments

- arrange interviews and meetings for the Lead Reviewer with relevant stakeholders, and collating input from stakeholders, including the public, where relevant

- ensure that the review is done in a timely manner and following the Cabinet Office ALB reviews guidance

- gather evidence and undertake analysis (as required)

- assist with the writing of the final recommendations and report

The departmental Review Team will be independent of the ALB and its sponsoring team. This independence will allow for the review to objectively consider the sponsor relationship between the ALB and the department.

Independent Lead Reviewer to:

- engage with the ALB senior leadership, keeping them sighted on progress, emerging findings and recommendations

- ensure a representative and proportionate number of stakeholders are engaged and given the opportunity to feed into the review

- oversee the development of an evidence base to form the review, in line with the agreed scope and depth of the review

- develop hypotheses and clearly articulate evidence-based findings in a clear, objective and proportionate report to the department

- deliver a set of feasible and risk-based findings and recommendations

- work with the department to communicate progress and outcome of the review to the Principal Accounting Officer, other departmental SCS and ministers, where necessary

- complete a lessons learnt template to gather insight from the review to help future reviews

ALB Senior Leadership to:

- work in an open and transparent manner with the Review Team to ensure all relevant data is shared in an ‘open book’ approach to its performance and finances

Sponsor Team to:

- engage openly with the Lead Reviewer and Review Team

- provide access to information where necessary

How the review will be agreed and cleared through the department

Agreement will be sought from the relevant SCS, the Permanent Secretary and the relevant minister on the:

- scope of the review; and

- report, outcomes and recommendations

Annex C - List of those interviewed

DCMS Sponsor Team

SGSA Board Members - interviewed as a group and individually

SGSA Chair and Chief Executive

SGSA HQ staff

Government Internal Audit Agency

The Premier League

The English Football League

The Football Association

The Football Supporters Association

Local Government - Chair of Safety Advisory Group Chairs

UK Football Policing Unit (Home Office)

The Football Safety Officers Association - Chair

FIFA

Wembley (Ground)

London Borough of Brent

Harrogate AFC (Club)

Harrogate (LA)

The Scottish Government

Football Safety Officers Association (Scotland)

DCMS Public Appointments Team

DCMS Fan Led Review Team

DCMS Legal Team

DCMS Finance Team

Annex D - Board members (March 2022)

| Board members (March 2022) | |

|---|---|

| Derek Wilson (Chair) | Derek is the Chair of the SGSA board, having been a specialist sports architect for 30 years spanning public and private sector roles. |

| Rimla Akhtar OBE | Rimla is a developer, communicator and strategist best known for her work as an Inclusion and Diversity specialist in sport, with over 18 years’ experience in the sports industry. |

| Janet Johnson | Janet Johnson is a chartered town planner by background, having specialised in regeneration and economic development in the North East of England through a career spanning almost 40 years. |

| Susan Johnson OBE | Susan was formerly the Chief Executive at County Durham and Darlington Fire & Rescue Service. Susan has also held a number of non-executive and trustee roles in the private, public and not for profit sectors. |

| Philip Kolvin QC | Philip is Head of Cornerstone Barristers specialising in licensing, planning, property and regulatory law and was appointed as Queen’s Counsel in 2009 and a Recorder of the Crown Court in 2018. |

| David Mackinnon | David is Regional Head of Operations for Jockey Club Racecourses South West Region, incorporating Cheltenham, Exeter, Warwick and Wincanton racecourses, having previously spent time working at the sport’s regulatory body (then the Jockey Club). |

| Dame Jil Matheson | Jil Matheson served as National Statistician, Head of the Government Statistical Service and Chief Executive of the UK Statistics Authority from 2009 until her retirement in 2014. Jil chaired the OECD’s Committee on Statistics and Statistical Policy and the UN Statistical Commission. |

| Jane Sawyers QPM | Jane is a visiting Professor at Staffordshire University (2018-). Prior to this she was Chief Constable of Staffordshire Police (2014-2017) and Deputy Chief Constable of Staffordshire Police (2013-2014). |