Near miss with track workers at Llandegai tunnel, Llandygái, Gwynedd, 13 February 2021

Published 30 June 2021

1. Important safety messages

This incident demonstrates the importance of:

-

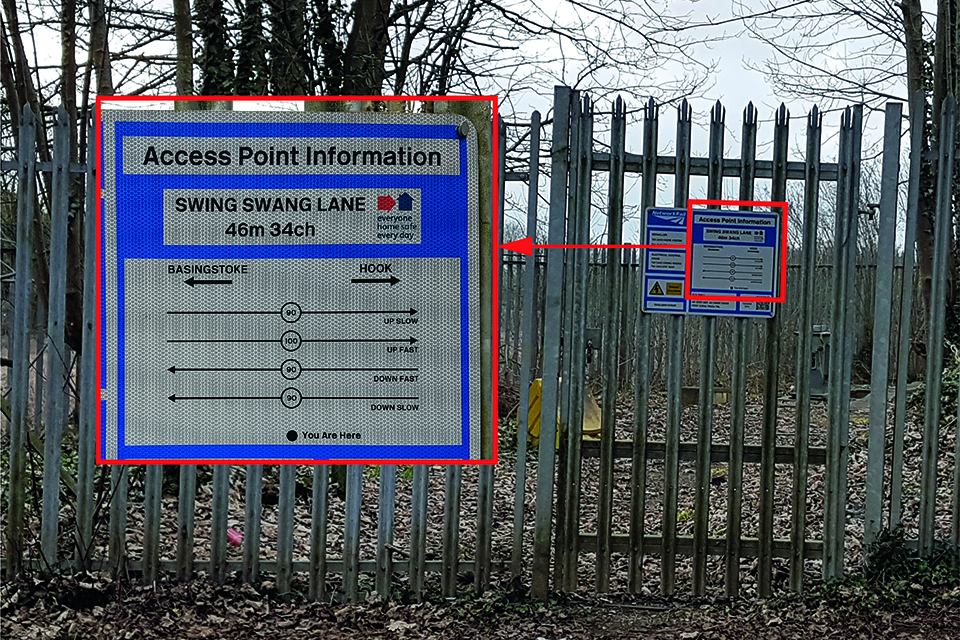

provision of signage at access points so that railway staff can verify their location, which side of the railway they are on, the designation of the lines and other information they need before going onto the railway

-

adopting the lowest risk safe system of work that is practicable when planning to go onto the railway

-

sounding the warning horn, which on this occasion probably averted a fatal accident

2. Summary of the incident

At around 12:33 hrs on 13 February 2021, a track worker undertaking inspection work narrowly avoided being struck by a train in Llandegai tunnel, near Bangor. The track worker was one of a group of two people who had been requested by Network Rail’s structure asset management team to carry out an inspection because of concerns about ice accumulation in the roof of the tunnel. The other person, while acting as ‘protection controller’, had taken a line blockage on the up line (the line that was used by trains heading east). The line blockage extended through this and two other tunnels nearby.

Having confirmed that the up line was blocked, the two track workers stayed together, and the protection controller undertook the duties of ‘controller of site safety’ (COSS).

The train involved was 1D12, the 10:25 hrs passenger service from Shrewsbury to Holyhead. It was travelling close to the maximum permissible line speed of 75 mph (120 km/h). The driver sounded the horn on sighting the work group. The group had just entered the tunnel on the down line (the line used by trains heading west) and were using a long pole to remove icicles from the water deflection sheeting on the tunnel roof. The COSS heard the horn, turned and saw the train approaching them. He shouted that they were on the wrong line and managed to get to safety on the other line. The other track worker tried to do the same but fell over. He then managed to roll into the space between the tracks. The driver saw that the track worker was across the right-hand running rail of the down line, and immediately applied the emergency brake and sounded the horn again. CCTV from the train showed that the track worker managed to crawl clear with about a second to spare.

No-one was injured, but those involved were badly shaken.

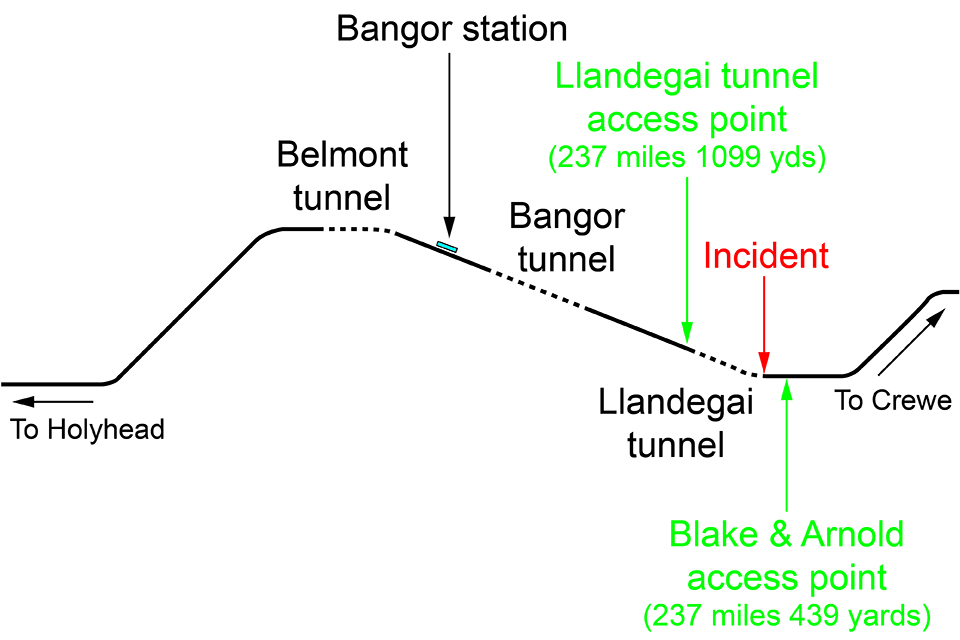

Route showing the location of the three tunnels and the two access points close to Llandegai tunnel

CCTV image from the approaching train (image courtesy of Transport for Wales)

3. Cause of the incident

The incident occurred because neither the COSS nor the track worker was aware that they were working on a line that was still open to traffic.

The COSS and the track worker worked for AmcoGiffen. The track worker was the line manager of the COSS, and together they managed a team contracted to Network Rail to carry out minor works on railway structures in North Wales. This contract included the provision of staff that Network Rail could call out when the need arose. The work on 13 February was in response to a call-out.

Network Rail’s plan for managing the risk from ice in tunnels on the Wales route required trains to be cautioned on receipt of a so-called ‘red warning’ low temperature alert (an hourly air temperature below 0°C for over 72 hours). Network Rail could also call for AmcoGiffen staff to attend tunnels with open ventilation shafts, like Llandegai, to check for and deal with any ice.

It had been cold for several days and, on 10 February, other staff from the AmcoGiffen team had been deployed to tunnels across North Wales. On Friday 12 February, Network Rail’s senior asset engineer for tunnels and staff at Wales route control were concerned that the cold spell was continuing. They wanted to avoid having to caution trains and decided to arrange a re-inspection of the tunnels as a precautionary measure. This needed to be completed before 21:30 hrs on Saturday 13 February, when the 72-hour time limit would have been reached. The senior asset engineer called the COSS who was rostered to respond to on-call requests.

The COSS had no staff available and, early on that Saturday morning, agreed with his manager (the track worker) that they would inspect the tunnels themselves. The route’s control office had already informed him that trains were being cautioned through Penmaenbach tunnel (near Conwy) because a driver had reported icicles there. Travelling in separate road vehicles, they visited this tunnel first, and then the tunnel at Penmaenrhos (near Llandudno Junction). They finished around 11:30 hrs and, after a break, were ready to inspect the three tunnels closer to Bangor.

Since the track worker had been to Llandegai tunnel during a planned possession in 2019 he suggested the COSS followed him there. At around 12:15 hrs, they arrived at the access point the track worker had used previously.

The COSS called the Bangor signaller to arrange for trains to be stopped so they could safely access the railway. He told the signaller he was at ‘Llandegai tunnel access gate’ and that he wanted to carry out an inspection of all three tunnels in the area. He said he needed only 10 to 20 minutes to inspect Llandegai tunnel. The signaller said he could offer a blockage of the up line for nearly an hour-and-a-half, but the down line would need to remain open. The COSS thought that this would be long enough to inspect all three tunnels and he and the signaller continued to complete the supporting forms.

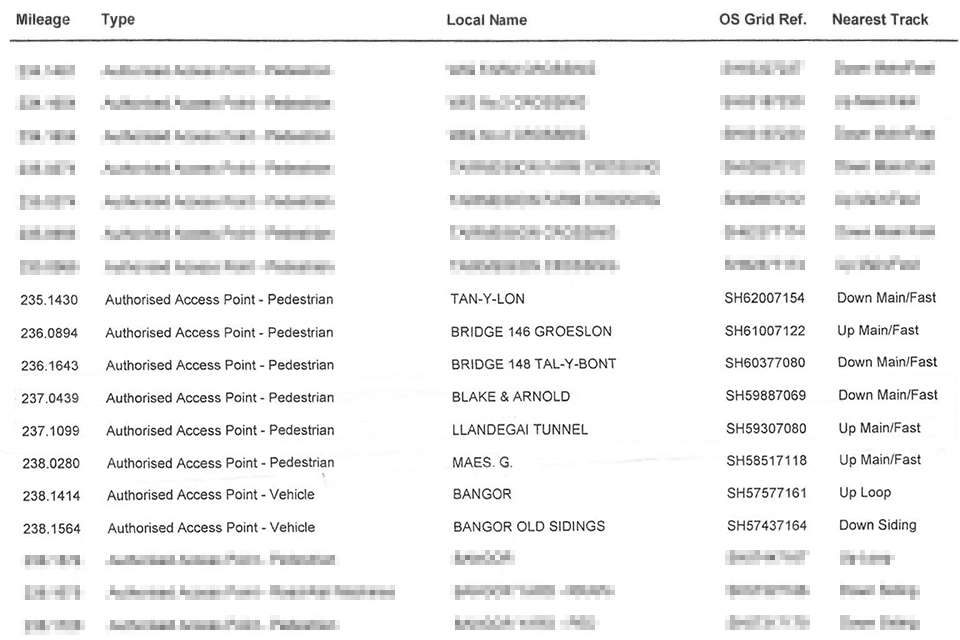

At site, the COSS referred to a list of access points in an extract of Network Rail’s hazard directory that he had brought with him, to confirm the names of the running lines. He picked out the access point named ‘Llandegai tunnel’ and, reading across, noted that the nearest track was the up line. Once out of his car, he showed this to the track worker. They both agreed they were at the Llandegai tunnel access point and, having taken the blockage, were safe to go on the line closest to them.

The COSS had not been to Llandegai tunnel before and had used an online Network Rail asset management database on the Friday evening to make a note of its location: 237 miles 572 yards. When he called the signaller, he said he was at 237 miles 444 yards, having possibly used a track location app to work this out. However, while the COSS and the track worker were close to these mileages, they were actually at ‘Blake & Arnold’ access point and not Llandegai tunnel access point. It is not clear why the COSS did not confirm the mileage of the Llandegai tunnel access point in the hazard directory.

The entry for the Blake & Arnold access point in the hazard directory correctly showed the nearest track as the down line, and not the up line as it was at Llandegai tunnel access point. However, their misunderstanding about their actual location caused them to enter the tunnel from the wrong direction and work on the down line, while believing that they were protected from approaching trains.

Neither the COSS nor the track worker had previously been to Llandegai tunnel access point. When the track worker visited the tunnel in 2019 he had gained access using the Blake & Arnold access point.

Hazard directory extract showing information for Blake & Arnold and Llandegai tunnel access points (image courtesy of AmcoGiffen)

Local residents explained that the boundary fence and gate at the Blake & Arnold access point were only installed in recent years. This is consistent with their condition. However, no signage had been provided identifying the location or the lines present.

Blake & Arnold access point

AmcoGiffen’s safe work process required that, for incident response work, the protection arrangements should be determined by the person called out. The COSS had taken a standard pack of information prepared to help his team plan and document the safe system of work. The pack included relevant infrastructure information, such as the hazard directory extract, and partly-completed safe system of work planning and task brief forms.

The COSS finalised these forms after he had arranged the blockage, adding site, task and other specific data. He then briefed the track worker, who recorded both receiving the brief and that, in the capacity of the ‘responsible manager’, he had checked the safe system of work.

AmcoGiffen, like Network Rail, requires consideration of a hierarchy of control measures when planning a safe system of work. Those systems that are higher in the hierarchy are considered to be safer, and therefore preferred, over those that are listed lower. The COSS selected a ‘site warden warning’ safe system of work (termed ‘separated’ in the railway rule book), allowing the group to work adjacent to the open running line. This system is two levels below the safest system: ‘safeguarded’. The partly-completed planning forms included pre-written generic reasons that were used to explain the decision.

A safeguarded safe system of work would almost certainly have averted the incident since trains would be prevented from approaching on either line. However, it would have meant asking the signaller for times when both lines could be blocked. RAIB found no evidence of such a request. The COSS had only been offered single line blocks when arranging the inspection of Penmaenbach and Penmaenrhos tunnels, and explained that he had probably come to accept that it would not be worthwhile asking for more.

RAIB reviewed the train service pattern on 13 February and found that there were regular periods of 20 minutes or more when no trains were running on either the up or down line in Llandegai tunnel. In fact, had the COSS and signaller waited the 10 minutes until train 1D12 had passed, another train would not have been due for over an hour. RAIB has concluded that this should have been more than sufficient time for the group to have inspected Llandegai tunnel and that a safeguarded safe system of work could, therefore, have reasonably been adopted.

4. Previous similar occurrences

RAIB has highlighted the presentation of information at access points in its summary of learning on the protection of track workers from moving trains.

In its report on the collision at Acton West in 2008 (report 15/2009) RAIB recommended that Network Rail should develop and implement a programme for the provision of track layout information signage at all access points (recommendation 3). Network Rail undertook a cost benefit analysis that concluded that it was not cost effective to retrofit signs at all access points, but that there was a case for fitting them at new-build access points. RAIB has since identified the lack of access point signage as factors in near-miss incidents at South Hampstead (report 20/2018) and Sundon (safety digest 05/2019). In the light of the serious nature of the South Hampstead and Sundon incidents, RAIB wrote to the Office of Rail and Road (ORR) on 29 March 2019 to express its view that there is a need for ORR to assess whether the actions taken by Network Rail in response to the recommendation made in the Acton West investigation are sufficient.

The response to RAIB’s letter of 29 March 2019 confirmed that ORR did not yet consider that it had sufficient information to confirm that recommendation 3 of the Acton West report had been implemented. ORR explained that, because Network Rail felt that fitting signs at all access points was not reasonably practicable, it was proposing a targeted programme of fitment at selected locations, and considering alternative solutions covering other locations. ORR also stated that it was awaiting confirmation that these programmes had been completed by all Network Rail routes.

In December 2020, Network Rail revised its specification for facilities allowing safe access to the railway. It requires that such signage is provided at all new access points and at existing access gates where risk assessment has identified a need.

An example of access point information signage (as fitted near Basingstoke)

In its previous investigations, RAIB has found a willingness to select track protection arrangements that are less safe than other recognised arrangements that it may have been possible to adopt. It identified a learning point on this in its report on the track worker accident at Bulwell in 2012 (report 20/2013). This specifically highlights the importance of properly applying the principles of the hierarchy of safe systems of work when planning to go onto the railway.